- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- Investment Summit 2024

- Projects to be funded by China

- Doctor shortage in Karnali

- Anti-elephantiasis medicine

- Dabbling in Diplomacy

UN chief puts a spotlight on Nepal’s climate crisis

Arjun Poudel

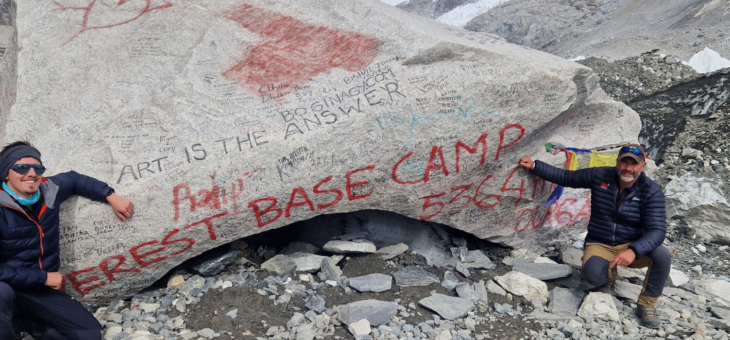

Last week, United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, who was on a four-day visit to Nepal, travelled to the Everest and Annapurna regions, which have been highly affected by the impacts of climate change.

Guterres not only witnessed first hand the impacts of climate change on Nepal’s mountainous region but also took stock of the ground reality from local residents, who have been bearing the brunt of the crisis, for which they are not responsible.

Upon returning from the Annapurna Base Camp, the visiting UN secretary general appealed to the global community to take urgent action to protect the mountains and glaciers.

“It’s time to stop the looting and generating climate change because we must preserve these wonderful mountains and these wonderful glaciers,” Guterres told media persons at Pokhara Airport. “And it’s essential to support Nepal and … other countries that do not contribute to climate change but suffer the consequences.”

Guterres, who addressed the joint sitting of Nepal’s federal parliament the next day, said the country was facing catastrophic consequences of climate change despite its negligible contribution to global emissions.

He highlighted how monsoons, storms and landslides are growing in force and ferocity—sweeping away crops, livestock and entire villages—decimating economies and ruining lives. Guterres urged the global community to come to Nepal to see the catastrophic effects of climate change.

The UN chief’s tour of Nepal’s regions vulnerable to the changing climate and his plea to the global community to “stop this madness” have potential significance also particularly for the 2023 UN climate change conference set to kick off in the United Arab Emirates on November 30.

Here is all you need to know about Nepal’s climate crisis and the significance of the UN secretary-general's remarks.

Dire consequences of the climate crisis

Nepal has been bearing the brunt of climate change for the past several years. Mountains are melting, and glacial lakes have burst and vanished at record rates, leading to a loss of one third of them in just three decades.

Monsoons, storms and landslides are growing in force and ferocity—sweeping away crops, livestock and entire villages—decimating economies and ruining lives.

Swift changes driven by a changing climate bring a new set of problems that directly affect lives and livelihoods. Over the years, mountain springs, which were the only source of water for the village, have started drying up and disappearing. Studies show close to 15 percent of the springs have dried up in some places and water flow has fallen as low as 70 percent elsewhere in the country.

The lack of water has not only affected the local supply but also hit farming and animal husbandry. There was no option left for the villagers than to migrate.

Multiple effects of climate change

Nepal is extremely vulnerable to climate change and has been warned by experts for a long time. Climate change has impacted multiple sectors—environment, agriculture, animal husbandry, drinking water, health, food security, hydropower, education, and women's empowerment.

Drying up of the streams and decreased flow of water caused by climate change threaten local communities who depend on spring water for their lives and livelihoods. Water-related stress—low production of staple crops and fruits, dried-up green pastures and low adaptive capacity—have forced locals to contemplate migration.

Mountainous areas like Manang and Mustang, where rainfall is always low, have been witnessing unusual rainfall for the last several years, which has directly affected the locals.

Districts such as Mustang, Manang, Sindhupalchok and Solukhumbu have witnessed catastrophic landslides and floods like never before in recent years.

Vector-borne diseases like dengue have started to emerge in the areas considered non-endemic in the past. Mental health problems have significantly risen in recent years, reportedly due to a rise in the stress level caused by the climate crisis.

Along with roads, bridges, and public properties, hydel projects (both in operation and under construction) sustained massive damage from floods and landslides. Hydropower is not only the main source of energy for the domestic market but is also a commodity with a huge export potential.

The changing climate’s impact on education has not yet been studied but due to the rise in labour migration, the workload on women has increased and affected their health issues overall.

Vulnerable populations hit disproportionately

People residing in the remote mountainous areas of Nepal and those involved in agriculture, animal husbandry, and women and children have been affected much by the adverse impacts of climate change.

The United Nations report titled “ Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability ” also stated that people living in deprivation and indigenous people have been disproportionately affected by climate change. They often rely on rain-fed agriculture in marginal areas with high exposure, increased vulnerability to water-related stress and low adaptive capacity.

Significance of Guterres’ speech

Visiting UN Secretary-General Guterres, in his address to a joint sitting of Nepal’s federal parliament, emphasised the same message that Nepali officials and climate experts have been raising in international forums over the years.

However, the UN chief's recognition of Nepal’s issue as ‘serious’ has a special meaning, multiple climate experts the Post talked to said.

“The UN secretary general drew the attention of world communities to the problems encountered by Nepal due to the climate crisis caused by emissions, to which the country is a negligible contributor,” said Bhusan Tuladhar, an environmentalist. “This helped us to make the issue global. I hope our policymakers and government will be serious about implementing various plans made to deal with adverse impacts of climate change.”

Guterres, in his speech, emphasised the significance of the Climate Adaptation Fund and its effective utilisation in mitigating the consequences of climate change and the need for international collaboration to address this shared global challenge.

He proposed an SDG Stimulus that would release at least $500 billion a year in affordable long-term finance for sustainable development and climate action.

“Developed countries must honour the promise of $100 billion a year and double adaptation finance, as a first step to devoting half of the climate finance to adaptation. The most vulnerable must be at the centre of efforts to build climate resilience.”

Through Nepal’s Parliament, he also urged leaders to act on climate without delay—with the biggest emitters leading from the front, saying all countries must put the Acceleration Agenda he has proposed into effect, to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

He appreciated Nepal’s role in climate action, claiming it was on target to net zero emissions by 2045 and carrying out extraordinary reforestation efforts. Nepal has made remarkable progress in increasing the forest cover with its successful community forestry programme.

Experts’ take

Climate experts in Nepal said there is an urgent need to pay attention to the scale and omnipresence of the problems caused by climate change.

Nepal has made both short- and long-term strategies and policies to deal with the adverse impacts of climate change, which the UN chief lauded. But when it comes to implementing them, the approach has been lackadaisical. The impacts of climate change have affected multiple sectors and the daily lives of many people.

“Whatever the policies on mitigation and adaptation we made, their implementation is poor,” said Madhukar Upadhya, a climate expert. “People affected by floods and landslides years ago have not yet received the compensation.”

According to experts, authorities should make sincere efforts to implement strategies to address the climate impacts. Due to the apathy of the authorities concerned for mitigating adverse impacts and helping people to adapt, people from the affected areas have been migrating at an alarming pace.

Even if the UN chief had promised a climate adaptation fund, it would be for all the affected countries, with the fund allocated for selected programmes applied by individual countries, said Upadhya.

“And we all know the limitations of UN-funded programmes. Nepal itself has to deal with the impacts, and for that, the government and concerned agencies have to make plans and sincere efforts for their implementation,” Upadhya said. “All relevant agencies should collaborate and coordinate to deal with the effects of climate change.”

Arjun Poudel Arjun Poudel is a health reporter for The Kathmandu Post. Before joining the Post, he worked for Sagarmatha Television, Naya Patrika, Republica and The Himalayan Times.

Related News

Sweltering heat causes distress across Tarai

Asia is most climate disaster-impacted region, UN meteorological agency says

Mountain villages bearing direct brunt of climate change

As peak forest fire season nears, number of human fatalities rises

Kathmandu world’s most polluted city, again

March marks yet another record in global heat

Most read from climate & environment.

Editor's Picks

.jpg&w=300&height=200)

Nepal sets sight on multi-billion dollar LGBTIQ tourism market

Escalating Middle East crisis threatens Nepali economy

Laws on marital rape still murky in Nepal

As springs dry up, water shortage deepens in high altitude villages of Mallarani in Pyuthan

Melodrama for monarchy

E-paper | april 28, 2024.

- Read ePaper Online

Key Highlights: Country Climate and Development Report for Nepal

Nepal country climate and development report: towards a green, resilient, and inclusive development.

Download Country Climate and Development Report for Nepal

Nepal has achieved significant development progress in recent decades. To sustain the development gains, Nepal must adapt its development pathway to a changing climate. Nepal 's Country Climate and Development Report (CCDR) identifies ways that Nepal can achieve its overall development objectives while fostering its strategic ambition to transition to a greener, more resilient, and inclusive development pathway.

Global warming and climate change are already affecting Nepal’s gross domestic product. Increased flooding, heat stress on labor productivity and health, and heat stress on crops and livestock are expected to be a continual drag on growth. Women, indigenous people, and other marginalized groups are often excluded from mainstream development and suffer from cumulative and cascading impacts of climate change and disasters. Without comprehensive and scaled-up climate action, climate change will continue to jeopardize gains in Nepal’s human development and poverty reduction.

To respond to this challenge, Nepal is already implementing steps to recalibrate its economy by adopting a Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development (GRID) approach . In 2021, Nepal adopted the Green, Resilient and Inclusive Development (GRID) approach as a national vision to guide long-term green growth and build resilience to climate and other shocks that are barriers to Nepal’s development ambitions. Under Nepal’s federal structure, the local governments are placed at the center of climate resilience and development efforts with extensive implementation responsibilities and play a crucial role in translating the GRID strategy into action.

Nepal has pledged to achieve net zero emissions by 2045 and to significantly scale up hydropower investment in the coming decade. Nepal has begun to put in place the necessary policy framework, such as the 2019 National Climate Change Policy, the 2022 Solid Waste Management Policy, the 2022 Forest Regulation and the 2022 Land Use Regulation. However, implementation of this reform agenda and prioritization of investments is incipient. Moreover, enhanced prioritization and efficiency of public expenditure are required to maximize climate and development benefits.

Last Updated: Sep 15, 2022

Nepal's CCDR report also outlines three key enabling themes to help support the priority system transitions toward a greener future for Nepal:

- Strengthening the resilience of people and community assets through early warning systems, shock-responsive safety nets, and access to quality skills training;

- Embedding disaster risk management at all tiers of government and across all sectors;

- Prioritizing Nepal’s funding needs by convening and coordinating financing for climate action.

Nepal Climate and Development Report – Full Profile

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Book Review Environmental Issues And Problems Of Nepal

Nepal, as a member of the most disaster-prone south asian region where over 700 major natural disaster incidences have taken place in the last thirty years, needs to pay more attention to climate change., basu sharma.

Keshav Bhattarai and Dennis Conway, Contemporary Environmental Problems in Nepal: Geographic Perspective , Springer, Switzerland, 2021. Pp. 792.

This is a remarkable book about environmental issues and problems of Nepal. Climate change is a matter of great concern to many, andthis book is the first of its kind to bring environmental and climate change issues that cut across geopolitical, technical, legal, demographic, and economic spheres in a holistic way. Even though the primary audience for this book is geographers, its scope is so vast that anyone interested in any important aspect of contemporary Nepal will find the book immensely insightful and useful.And one of the very important attributes of the book is its data-rich content and use of data visualization.

The book is a magnum opus . It has nine chapters. Each chapter is recast in a wider regional and global environmental context with detailed and richly documented information. A very brief summary of each of the chapters of the book is in order.

The first chapter introduces environmental problems faced by Nepal in specific reference to ecopolitical and sociodemographic conditions with focus on water resources, physiography, human adaptation, and broader border and regional context. This chapter thus establishes the foundation for deeper analyses of myriads of other environmental issues and problems in subsequent chapters. The second chapter examines influences on deteriorating environment coming from demographic considerations such as population structure, mortality and fertility rates, caste and ethnicity, religion and language, migration and brain drain. It argues that environmental degradation could dramatically change the existing fabric of the Nepalese society currently characterized by harmonious co-existence of multiethnic, multireligious and multilingual groups into a society rife with conflicts over matters related to resource sharing and ecosystem services. Chapter three addresses issues pertaining to environmental sustainability and human well-being.The authors take on environmental degradation problems due to glacier lake outburst floods, earthquakes, landslides, and deforestation, among others, as major threats for sustainability. They warn of possibility of recurring disasters if proper actions for environmental protection are not taken immediately. Another major factor accounting for many of the environmental problems in Nepal is urbanization. Chapter four delineates facets of rapid urbanization taking place in Nepal.The authors demonstrate that a lack of professional approach to urban planning has produced many negative effects on environment and argue that it is important to bring both science and conscience to create environment friendly urban growth.One of the major problems facing the agricultural sector in Nepal is out-migration of farmers leaving the land barren in many instances. In addition, global climate change has severely affected agricultural practices. These developments have adversely influenced poverty alleviation policies and practices. These are the subject matters discussed in Chapter five. The theme of chapter six is the energy sector. While Nepal is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of hydropower potential, sadly only three percent of this potential has been utilized so far. The authors convincingly arguethat Nepal should focus on developing and deploying hydropower for prosperity.Since hydropower is clean energy, its development and deployment can bring many benefits to the country and the people. Issues and problems related to developmental infrastructures such as roads, communication network, population distribution, capacity building, incomes distribution, and quality of life are examined in chapter seven. The authors show a nexus between income inequality and disparity and environmental sustainability and argue that incomes equality is one of the solutions to environmental problems.They call for immediate attention of the Government of Nepal towards achieving this goal. Chapter eight examines the effect of deforestation on environmental degradation, and on greenhouse gas emission, and offers an empirical assessment of geospatial aspects of human-environment interaction and resulting consequences for the habitat at a macro level. Chapter nine is an elaborate summary of the preceding chapters together with overall conclusion.Policy implications of the analysis presented in the book are further discussed in this chapter.

Nepal, as a member of the most disaster-prone South Asian region where over 700 major natural disaster incidences have taken place in the last thirty years, needs to pay more attention to climate change. Failure to take actions on climate change issues might result in major disasters for the country. For example, the retreat of the Himalayan glaciers has already begun to negatively affect rainfall patterns, groundwater recharge system, and water supplies, among others. These changes have huge implications for the livelihood of subsistence farmers and many other low- income groups in the country.The authors have convincingly argued that even the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of the United Nations such as eradicating poverty and combating communicable diseases are unattainable without embracing environmental agenda.However, it is not to say that the government of Nepal has done nothing to ameliorate atmospheric carbon emissions. As the authors have documented, there are over 2,300 community groups involved in managing 2.25 hectares of community forests. In addition, the government has instituted a National Adaptation Plan of Action and a Local Adaptation Program of Action. These corrective measures taken by the government are commendable. But they are not sufficient to address the huge climate change problems that we are facing now and that we may face in future. Hence the policy prescription that more proactive climate action plans are urgently needed is a sound one.

Since climate change is interregional and global, neighboring country policies will have repercussions for domestic policies. In view of this transregional nature of the phenomenon, how to align domestically designed climate policies of each individual countries at a regional level is an important issue. The authors could have shed more light on this aspect of the transborder climate problem. Nonetheless, the goal of bringing in all major environment related matters into one analytical platform has been achieved. And the amount of thinking, research, and reflection appliedby the authors to bring this goal into fruition appears to be a considerable feat. In my view, this book will prove to be the foundational work in the field of environmental studies in Nepal.

Overall, Contemporary Environmental Problems in Nepal: Geographic Perspective is a very engaging and informative book. It is packed with information and insights. It includes sources from plurality of disciplines and fields. The main objective of the book as set out in the introductory chapter was to render it as “a reference for bio-economic modeling to assess the land productivity through the analysis of location-specific issues’ (p. 31). The authors have becomesuccessful in achieving this objective. The book thus offers a solid foundation for understanding and explaining why environmental problems are so important in Nepal. In doing so, it provides motivation and inspiration to scholars for doing further research. The book should belong to the personal library of everyone interested in environmental problems in general and development issues in the context of climate change in Nepal in particular.

Basu Sharma, Professor of Organizational Studies & Editor-in-chief, Journal of Comparative International Management University of New Brunswick Fredericton, NB, Canada E3B 5A3

Professor of Organizational Studies & Editor-in-chief, Journal of Comparative International Management University of New Brunswick Fredericton, NB, Canada E3B 5A3

More on Opinion

Latest Magazine

VOL. 17, No. 17, April.12,2024 (Chaitra,30. 2080) Publisher and Editor: Keshab Prasad Poudel Online Register Number: DOI 584/074-75

VOL. 17, No. 16, March.29,2024 (Chaitra,16. 2080) Publisher and Editor: Keshab Prasad Poudel Online Register Number: DOI 584/074-75

VOL. 17, No. 15, March.10,2024 (Falgun,27. 2080) Publisher and Editor: Keshab Prasad Poudel Online Register Number: DOI 584/074-75

VOL. 17, No. 14, February.23,2024 (Falgun,11. 2080) Publisher and Editor: Keshab Prasad Poudel Online Register Number: DOI 584/074-75

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, environmental inequalities in kathmandu, nepal—household perceptions of changes between 2013 and 2021.

- 1 Department of Urban and Regional Planning and Geo-Information Management, Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands

- 2 Lumanti Support Group for Shelter, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 3 Department of Social Epidemiology, Institute of Public Health and Nursing Research, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

Environmental health inequalities in cities of the Global South are hardly studied up to now, though they are expected to increase due to rapid urbanization and motorization taking place in many of these cities. In this study, environmental inequalities in the city of Kathmandu, Nepal for the years 2013 and 2021 are analyzed. The goal of the study is to determine the degree of environmental inequalities and their changes over time. The study examines horizontal and vertical inequalities in access to drinking water sources, air and noise pollution exposure, and health effects based on self-reported household data. Results show statistically significant environmental inequalities between neighborhoods in Kathmandu regarding access to basic water infrastructure, air and noise pollution exposure, and resulting health effects. Inequalities between socio-economic groups are not significant. Over time, the perceived exposure to air pollution has increased, mainly due to increased motorized traffic, whereas vertical inequalities persisted. While inequalities between socio-economic groups have not increased, the high socioeconomic group reveals more concerns and awareness about environmental burdens than the low socioeconomic group. In conclusion, given the intertwined horizontal and vertical inequalities, any planning response action needs to consider the population's vulnerability to target interventions to the most affected areas.

Introduction

Large cities in the Global South often feature a poor environmental quality. High levels of air ( Flanagan et al., 2021 ), noise ( Amoatey et al., 2020 ), and water pollution ( Yin et al., 2021 ) result from industrial production, small-scale commercial activities, poor infrastructure quality, and motorized transport ( Sen Roy, 2018 ). In addition, in large parts of the cities, people lack access to environmental benefits such as green areas and parks ( Gelan and Girma, 2021 ). The absence of environmental standards and regulations to monitor environmental quality and the limited enforcement of existing regulations due to weak governance systems ( Aryal et al., 2021 ) are restricting improvements of the situation. On the contrary, it is to be expected that due to the rapid growth of many Global South cities going along with rising motorization and increasing industrial production as well as private consumption the environmental quality will worsen over time ( Kumar et al., 2014 ).

At the same time, we see increasing inequalities within cities of the Global South. While certain parts of the society benefit from the slow economic growth of the cities, others are excluded from it ( Nijman and Wei, 2020 ). This is manifested in increasing spatial inequalities associated with an unequal geographic distribution of resources as well as access to amenities that particularly affect marginalized segments of the population ( Soja, 2010 ), as reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals ( https://sdgs.un.org/goals ). SDG 10 postulates to reduce inequalities concerning income, wealth, opportunity and other dimensions, particularly in lower-income countries. In line with the demanded localization of the SDGs ( Fenton and Gustafsson, 2017 ), such inequalities also need to be addressed at the city level.

Specific inequalities resulting from poor urban environmental quality and increasing socio-economic inequalities are described as environmental inequalities. Brulle and Pellow (2006 , p. 104) define environmental inequalities as a “situation in which a specific social group is disproportionately affected by environmental hazards,” either caused by factors relating to the socio-economic status of the population or by characteristics of the built environment ( Flacke et al., 2016 ). Disproportionately affected may further mean that certain groups exposed to environmental burdens may show different health outcomes ( Harpham, 2009 ). People living in neighborhoods strongly exposed to environmental hazards may hold significantly higher amounts of, e.g., cardiovascular or respiratory diseases ( Pickett and Pearl, 2001 ; Riva et al., 2007 ).

Such environmental inequalities are typically analyzed in a horizontal or in a vertical perspective ( Kalasa et al., 2021 ). The horizontal perspective focuses on spatial variations in levels of exposure and investigates environmental inequalities between different geographical units. Such an analysis helps explore the link between health and place ( Bambra et al., 2019 ). The vertical perspective typically investigates environmental inequalities between different socio-economic variables, for example socio-economic status, ethnicity or race. In this study, we aim to combine the two perspectives because both are needed to devise policy measures suitable to overcome inequalities ( Kalasa et al., 2021 ) While several studies have investigated environmental inequalities in cities of the Global North (e.g., Maantay, 2007 ; Rüttenauer, 2018 ), they are hardly studied in cities of the Global South yet ( Shao et al., 2021 ).

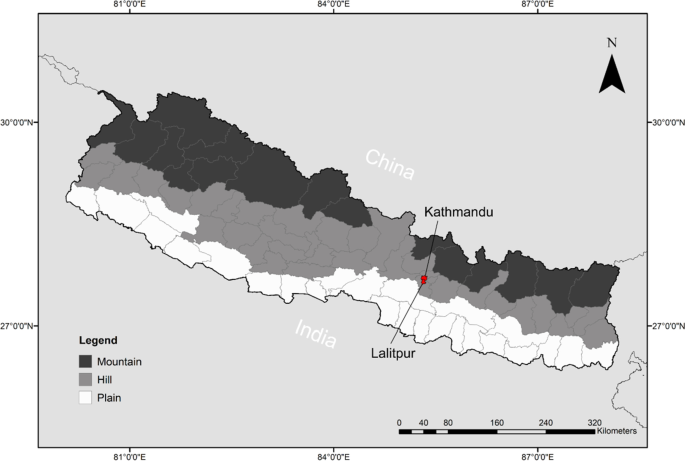

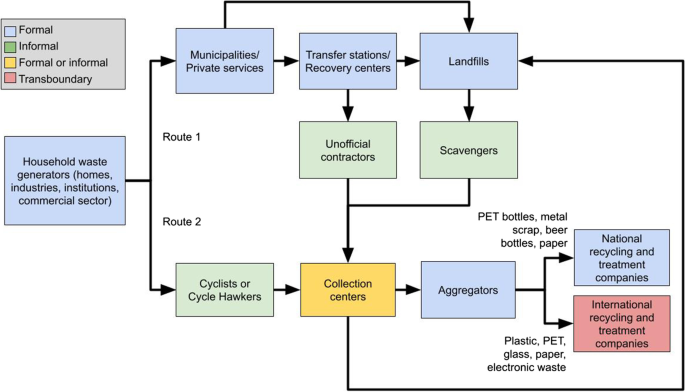

To address this gap, we analyze in this paper environmental inequalities at city level in a Global South context, using the city of Kathmandu, Nepal, as the case study. Nepal is one of the least developed countries in South-East Asia. Its capital city, Kathmandu is continuously growing due to a steady inflow from other parts of the country ( Chauhan et al., 2021 ). Major environmental problems of the city are high levels of air ( Gurung et al., 2017b ) and noise pollution ( Chauhan et al., 2021 ), poor drinking water quality ( Thapa et al., 2019 ), and poor solid waste management ( Nepal Health Research Council, 2009 ). In addition, the city is frequently struck by various environmental disasters from flooding, landslides, and earthquakes, the last major earthquake in 2015 ( Khatakho et al., 2021 ). Various studies have investigated aspects of environmental health issues in Kathmandu ( Pant, 2009 ; Kurmi et al., 2016 ; Thapa et al., 2019 ; Chauhan et al., 2021 ). However, no studies so far have investigated environmental inequalities between different areas or socio-economic groups.

The aim of the paper is to analyze intra-city environmental inequalities and their changes over time at neighborhood level in Kathmandu. This analysis based on empirical data is done for two points in time, i.e., the years 2013 and 2021. The longitudinal design of the study aims to detect whether the situation of environmental inequalities has worsened over the years due to ongoing urbanization and motorization. In the discussion section drivers of potential change are discussed and suitable intervention policies are reflected.

Materials and Methods

Research design.

This study analyses environmental inequalities in terms of differences in exposure to environmental burdens and related heaths effects in six neighborhoods of Kathmandu for two points in time, 2013 and 2021. To this end, we make use of the Driving force-Pressure-State-Exposure-Effect-Action (DPSEEA) indicator framework ( WHO, 1999 ). The DPSEEA framework “shows links between exposures and health effects as determined by many different factors operating through a chain of events” ( Hambling et al., 2011 , p. 12). These are conceptualized as high-level drivers and pressures, such as urban growth, economic or technological development, that influence the state of the environment and exposures. Following Morris et al. (2006) we relate the exposure–effects linkage of the DPSEEA framework to specific social, economic and demographic context indicators to analyze environmental inequalities ( Köckler and Flacke, 2013 ). A further advantage of the DPSEEA framework is that it allows identifying potential policy intervention points along the environmental health causal chain ( Briggs, 2003 ).

Case Study Area

Kathmandu Metropolitan city (KMC) is the capital of Nepal and its major economic center. For many years, Kathmandu has been experiencing a huge inflow of people from other parts of the country ( Gurung et al., 2017a ), resulting in Nepal's highest population growth rates. In 2011 Kathmandu had a population of 1,006,656 ( CBS, 2012 ), which almost doubled within 10 years (2001: 671,846 inhabitants. The population of Kathmandu Metropolitan city is reduced to 845,767 according to the most recent census survey in 2021 ( https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/Home/Details?tpid=1&dcid=0f011f13-7ef6-42dd-9f03-c7d309d4fca3 ). Basic infrastructure like water supply, electricity, gas, telecommunications, roads, sanitation, education, and transportation is well-developed in Kathmandu compared to the rest of Nepal, though heavily under pressure due to the strong population increase. The Nepal/Gorkha earthquake from April 2015 caused almost 10,000 fatalities and massive destructions to more than 750,000 houses across Nepal, including Kathmandu ( Bisri and Beniya, 2016 ).

The unplanned urbanization and haphazard development of industrial units have generated many environmental problems affecting human health and welfare. A major infrastructural deficiency in Kathmandu is the shortage of drinkable water from piped water. Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited (KUKL) supplies water throughout the Kathmandu Valley but covers only 19% of the water demand during the dry season and 31% during the wet season with the supply being intermittent ( Thapa et al., 2008 , 2018 ). Moreover, a continuous increase in motorized vehicles, ongoing construction works, and small-scaled industries contribute to rising noise and air pollution levels ( Gurung et al., 2017b ). Air pollution and noise pollution are seen as other major problems that are to be addressed by governmental policies in Kathmandu ( Chauhan et al., 2021 ).

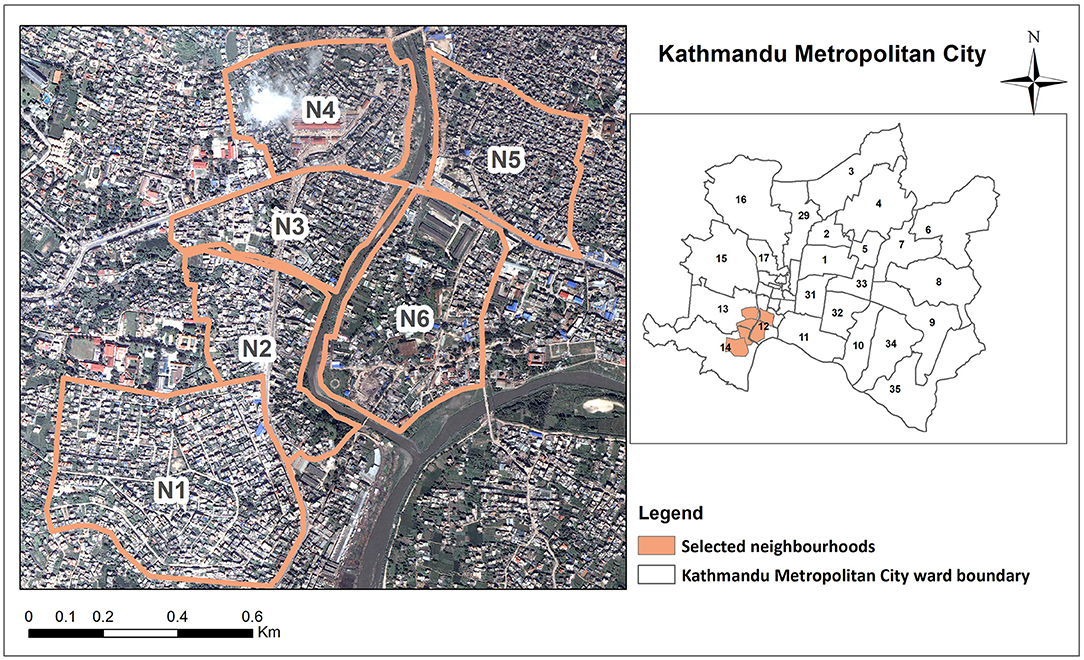

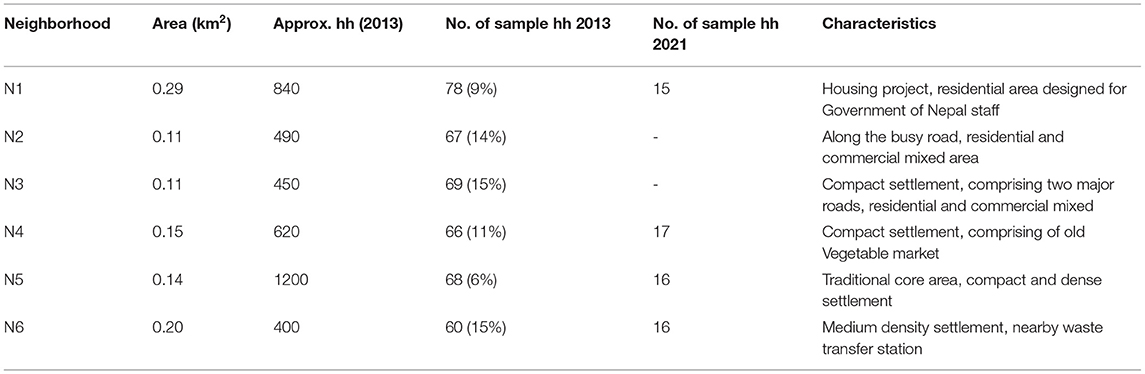

For the empirical study, six neighborhoods were selected ( Figure 1 ), that are representative for the urban built area of Kathmandu. We choose the neighborhood level for assessing environmental inequalities, because neighborhoods in Kathmandu show rather homogenous socio-economic characteristics. Details of the six neighborhoods are given in Table 1 . Neighborhood N1 is the planned residential area of the Kuleshwor Housing project completed in 1990. Neighborhood N2 portrays mixed residential and commercial development along the major road connecting to Tribhuwan highway. Neighborhoods N3 and N4, located west of the Bishnumati River, are characterized by compact settlements of mixed land use for residential and commercial purposes. N4 includes the old fruit and vegetable wholesale market in the south. Neighborhoods N5 and N6 are located east of the Bishnumati river, the Bagmati river borders N6 in the south. N5 is of the highest settlement density and comprises the traditional core settlement with several courtyards and several sacred shrines and pilgrimage sites nearby and the highway in the north. Medium-density settlements, the highway, and a waste transfer station in the south characterize neighborhood N6.

Figure 1 . Location of the neighborhoods in Kathmandu.

Table 1 . Characteristics of sample neighborhoods.

Indicators Development

A key challenge of environmental inequality studies at city level in Global South context is the limited data available in terms of exposure and health effects indicators. Given that only limited official data is available, this study is based on self-reported exposure levels and health effects as expressed by survey respondents. The study focuses on exposure levels and health effects related to drinking water availability and air and noise pollution as these are the main environmental hazards the city of Kathmandu faces. The following indicators were asked in the survey to explore levels of exposure to the various environmental burdens ( Supplementary Table 1 ).

Drinking water supply is one of the major environmental concerns in Kathmandu. According to the SDGs indicator 6.1.1 safely managed drinking water service is defined as one located on premises, available when needed and free from fecal and priority chemical contamination ( https://unstats.un.org/wiki/display/SDGeHandbook/Indicator$+$6.1.1 ). Due to a low supply of municipal pipe water in Kathmandu, households must approach multiple water sources ( Shrestha et al., 2016b ). Regarding water quality, various studies indicate that all water sources can potentially be contaminated in Kathmandu. Warner et al. (2008) observed bacterial contamination in 72% of 100 water sample in Kathmandu valley including pipe water. Subedi and Aryal (2010) found that in a sample of 57 bottles of sealed water from different brands distributed in Kathmandu valley 90% of them contained total coliforms and 60% contained fecal coliforms. A more recent study showed that the treated water had poor quality exceeding most of the standard values set by Nepal Drinking Water Quality Standards ( Maharjan et al., 2018 ). Despite these various findings, piped water is still considered a permanent source of water for drinking and cooking as it is the cheapest source compared to jar water and tanker water ( Shrestha et al., 2016b ). To capture inequalities with respect to the quality and quantity of the water supply, accessibility to pipe water and use of water for drinking and cooking from the different sources is included in the survey.

Various studies show that motorized transport and industrial production are the major source of air pollution in many Asian cities ( Huizenga and Leather, 2012 ) and that roadside air pollution is very high, especially due to high vehicles emissions and resuspension of street dust ( Shah et al., 1997 ). In Kathmandu, solid waste management is also considered as contributing to air pollution because of the bad odor due to the accumulation of garbage ( Mohanty, 2011 ). Therefore, all three sources for air pollution are considered in the survey.

Noise pollution is less emphasized compared to other environmental pollution. However, due to exposure to noise pollution, health problems are increasing in Kathmandu ( Chauhan et al., 2021 ). Major noise sources include community noise, industrial noise and roadway noise ( Nepal Health Research Council, 2009 ). Thus, all three are included in the survey.

Indicators collected to capture health effects resulting from exposure to the various environmental burdens are shown in Supplementary Table 2 . Self-reported health effects due to water pollution were collected using the indicator of the occurrence of waterborne diseases in the family over the last 6 months. Several waterborne diseases have been reported resulting from contaminated water such as diarrhea, typhoid, cholera, dysentery, jaundice, paratyphoid fever, amoebiasis in Nepal ( Rijal et al., 2019 ). As these diseases are transmitted through the oral route, they are often attributed to the cause of direct drinking of contaminated water.

Increasing evidence shows that air pollution is associated with adverse health outcomes, particularly respiratory diseases such as asthma, sore throat, and cough ( Cohen et al., 2017 ). Moreover, air pollution is also considered to trigger external allergic effects. Though the role of air pollution in the development of allergic diseases is not clear, several studies have demonstrated an association between increased air pollution and the increased risk of allergic sensitization and prevalence of rhinitis, which is often associated with cold-like symptoms such as sneezing, itchiness, running nose ( Lee et al., 2013 ). Furthermore, air pollution is considered to exert negative effects on human skin (e.g., itchy skin, eczema, sores, and rash) as was well as on eyes (e.g., itchy eyes, bloodshot eyes, teary eyes; Reinmuth-Selzle et al., 2017 ). Therefore, two indicators are developed to assess self-reported health effects due to air pollution: respiratory diseases such as asthma, chest pain, chronic cough and symptoms related to allergic reactions such as skin rashes, frequent running nose/sneezing, skin irritation, and burning/swelling eyelid.

Daily exposure to high noise levels over a long period can have harmful effects, and these health effects manifest as auditory disorders or non-auditory symptoms ( Nongkynrih et al., 2014 ). Therefore, the indicator assessing health effects due to noise pollution was based on whether the sampled household reported on any symptoms related to auditory disorders such as hearing impairment, earache, noise-induced hearing loss or hypertension or non-auditory symptoms usually manifested as headache, psychological disturbances presented as irritability, dizziness, and sleeping.

Five indicators were used to assess the socio-economic context of the respondents ( Supplementary Table 3 ). Next to the most commonly used income, education and occupation indicators, two indicators associated with wealth in Global south contexts, car and bike ownership, are added to the survey.

Data Collection

Random sampling was done to select households for the survey in 2013. The total sample size for this study was 408 households with 60–75 households from each selected neighborhood ( Table 1 ). The survey questionnaire focused on three groups of variables: socio-economic characteristics, perceived environmental conditions (exposure) and self-reported health conditions, all captured as yes/no dichotomous variables. The questionnaire used in the 2013 survey is given in Supplementary Table 4 .

From March to May 2021, we repeated the household survey in four of the six neighborhoods (N1, 4, 5, 6), because the covid19 pandemic forced us to scale down the second survey and higher environmental inequalities were evident in these neighborhoods in 2013 ( Maharjan, 2014 ). The goal of this second survey was (a) to capture the current exposure levels and health effects in 2021, and (b) to capture changes in environmental quality as perceived by respondents. Hereto, we added questions asking how the respondents perceive and judge environmental quality change since 2013 and what measures they take to cope with the situation. To reduce recall bias as it was presumably difficult to remember environmental qualities some 8 years ago, we asked in the survey how the respondents remember the situation in the times before the earthquake, which occurred in 2015. We interviewed only respondents who had lived in the neighborhood for more than 8 years. We adopted a purposive sampling strategy and selected households located either along the road/river or far away from it and either close to or far away from the waste transfer station and vegetable markets, as these are the main sources of environmental pollution found in 2013 ( Maharjan, 2014 ). Additionally, visual observation of the exterior condition of houses was also considered before the interview to include households with varying socio-economic characteristics. The questionnaire used in the 2021 survey is given in Supplementary Table 5 . For some of the questions asked in 2013 already, we changed the format to obtain more detailed information. In detail, the questions regarding exposure to the various environmental burdens were changed from a yes/no format to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very much/very high to not at all/very low.

Data Analysis

The analysis of environmental inequalities combines descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Horizontal inequalities are analyzed by comparing indicators over the six neighborhoods, while vertical inequalities are studied based on a cluster analysis classifying households into three different socio-economic groups. We applied Pearson's chi-square tests ( Field, 2009 ) to test statistically significant relationships of neighborhoods and socio-economic clusters with environmental exposure levels and reported health effects for 2013. From these associations of the categorical variables we only report the yes categories, assessing statistically significant relationship between two variables at 95% confidence level.

For analyzing the changes of perceived levels of exposure and reported health effects in 2021 compared to 2013 we classified the reported 5-point Likert scaled data of percentages of respondents into quintiles ranging from 0–20% to 80.1–100%. Based on these quintiles, changes in levels of exposure and health effects are indicated as a change of quintile. In the case of water supply these quintiles are classified as a benefit variable, i.e., the higher the better. In the case of air and noise pollution and the reported health effects quintiles are classified as a cost variable, i.e., the higher the quintile the worse.

Socio-economic clusters for 2013 were created using the five socio-economic indicators—household income, education level, occupation, car ownership, and bike ownership –in a two-step cluster analysis in SPSS 21. The number of clusters was specified in advance as 3 in order to achieve distinct socioeconomic clusters. We used log-likelihood distance measure with Schwarz's Bayesian Criterion (BIC) to repeatedly produce the clustering solutions. The Silhouette Index (SI), which ranges from−1 to 1, was observed to determine the clustering quality. We accept the cluster with SI close to 0.5, which is considered fair clustering quality. After inspecting the cluster characteristics, the authors then categorized the clusters to high, medium and low socioeconomic clusters. The indicator household income is the most important predictor for cluster formation, followed by the indicators education level, occupation and car ownership, and numbers of motorbikes per family.

For 2021, socioeconomic clusters were created using the same socio-economic indicators as in 2013 in a two-step cluster analysis, except that bike ownership was considered in 2021 as a dichotomous variable (yes/no) instead of the number of bikes as in 2013. In this cluster analysis, occupation is the most important predictor for forming clusters, followed by household income, highest education, bike ownership, and car ownership.

Socio-Economic Characteristics of Neighborhoods and Clusters

Socio-economic neighborhood characteristics.

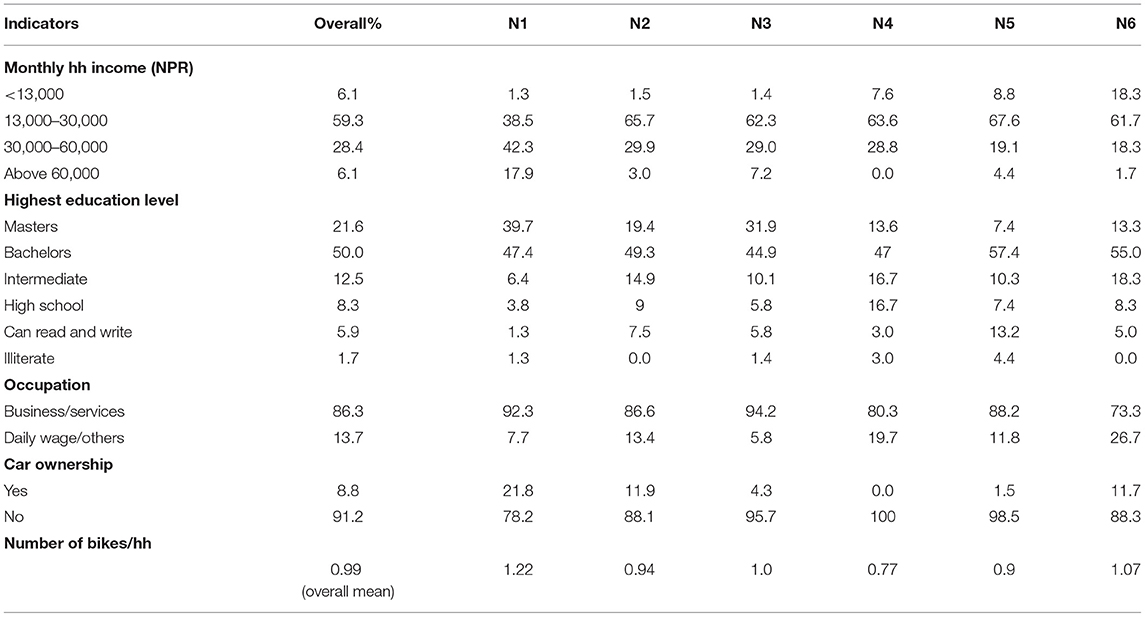

Table 2 shows the socio-economic characteristics of the six neighborhoods in 2013 based on the sample household data, as no official census data at neighborhood level is available. Neighborhood N1 is mostly inhabited by highly educated people of the upper middle- and high-income groups having also the highest share of car ownership. In all other neighborhoods the share of households in the middle-income group (13,000–30,000 NRs.) is around two-third, while in N2, 3, and 4 another 30% are in the upper middle income group (30,000–60,000 NRs.) and N4, 5, and 6 also have a considerable higher share of household in the low income cluster (<13,000 NRs.).

Table 2 . Socio-economic characteristics of neighborhoods 2013.

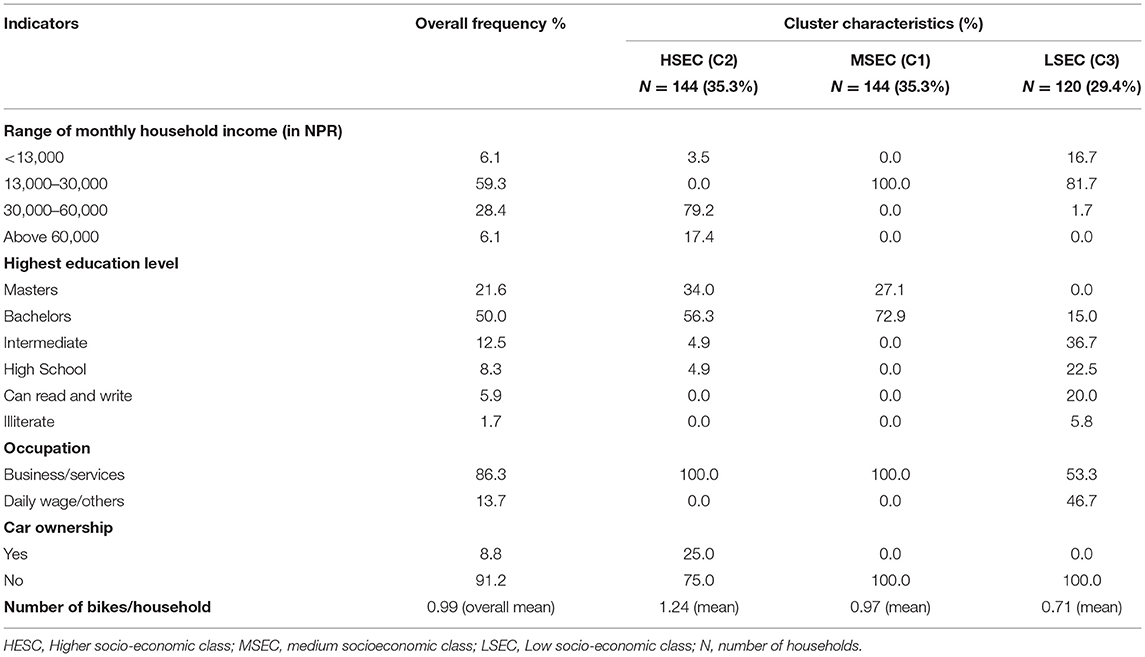

Socio-Economic Clusters

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the three socio-economic clusters in 2013. Cluster C2 can be characterized as the higher socio-economic cluster (HSEC), including 35.3% of the sampled households. All households of high income fall in this cluster. The highest education level attained by family members is typically a bachelor's or master's degree and all households have business or services as a major occupation. All households owning a car are included in this cluster and the average number of motor bikes per household is significantly higher. Cluster C1 can be characterized as the medium socioeconomic class (MSEC). It includes all households with a middle income (13,000–30,000 NRs). Most households have at least a bachelor's degree and a major occupation in business or services. Cluster C3, the low socio-economic class (LSEC), is composed of 29.4% of total sampled households. It contains mainly households with household income between 13,000 and 30,000 NRs or below. Most households in this cluster have as highest education level below bachelor's degree, with only 15% having a master's degree. While still about half of the households have a major occupation in business or services, all households with major occupation as daily wage services are grouped into this cluster. The average number of bikes owned is the lowest.

Table 3 . Characteristics of clusters 2013.

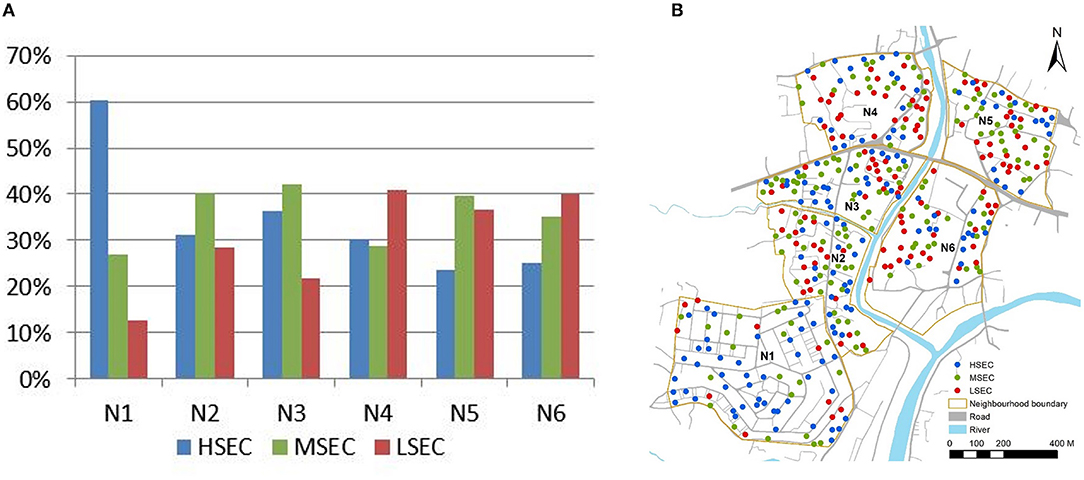

Figure 2 shows the distribution of classified households in the neighborhoods in 2013. N1 comprises the highest number of HSEC households. N4 contains the highest number of LSEC households, whereas N3 has the highest number of MSEC households. N2 and N3 show an almost similar composition of all clusters. N5 and N6 are largely composed of MSEC and LSEC, almost with equal numbers of households.

Figure 2 . Distribution of socio-economic clusters per neighborhood 2013. (A) In percentage per neighborhood, (B) spatial distribution in neighborhoods.

The three clusters formed for 2021 have very similar characteristics as those formed in 2013 ( Supplementary Table 6 ). Out of 64 households surveyed, the distribution for HSEC, MSEC, and LSEC is 21, 24, and 19 households, respectively. The distribution of socio-economic classes in the different neighborhoods is also similar to 2013. N1 has the highest percentage of HSEC and the lowest percentage of LSEC households. In the case of N4, having the highest percentage of households in LSEC in 2013, the percentage of MSEC and LSEC are equal in 2021, whereas N6 has the highest percentage of households of LSEC. A noticeable increase in households of MSEC is observed in N5.

Environmental Inequalities in Kathmandu 2013

Horizontal inequalities in perceived exposure and self-reported health effects.

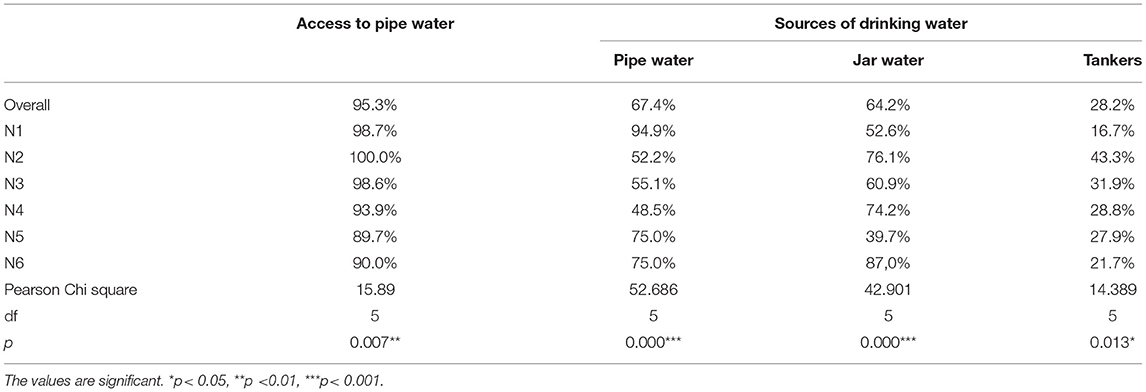

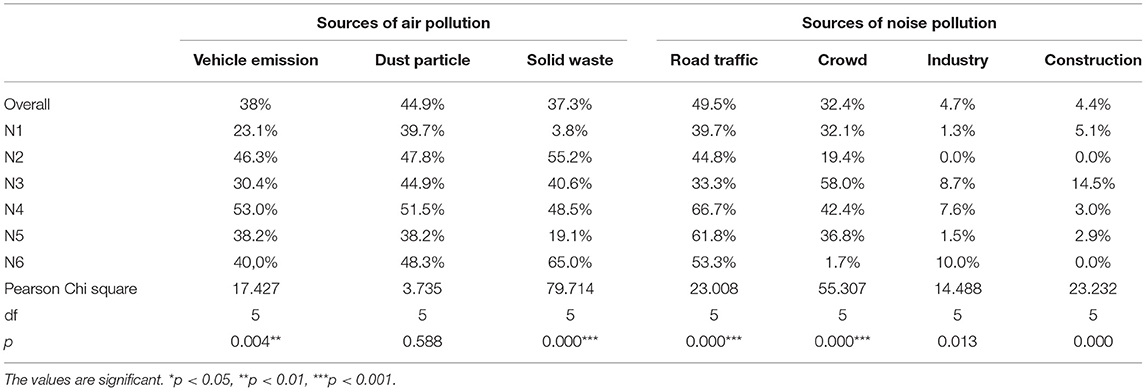

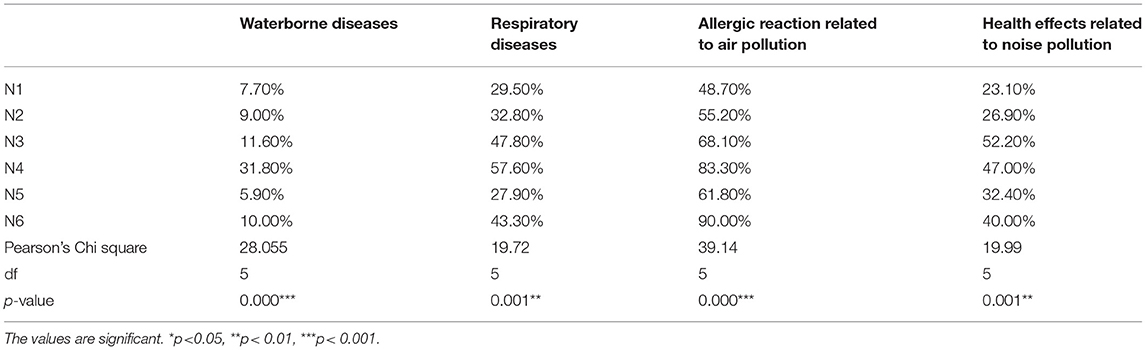

In 2013 environmental inequalities between the six neighborhoods were found for several sources of environmental burdens considered in the study. Statistically significant were the inequalities in sources of drinking water ( Table 4 ), exposure to air pollution from vehicle emissions and solid waste, and exposure to noise pollution from road traffic and crowds ( Table 5 ). The analysis of health outcomes reveals significant inequalities between the six neighborhoods for all four self-reported health effects ( Table 6 ).

Table 4 . Access to pipe water and sources of drinking water (2013).

Table 5 . Perceived exposure to various sources of air and noise pollution (2013).

Table 6 . Self-reported health effects per neighborhood in 2013.

While around 95% of the households have access to piped water supply ( Table 4 ), only 13% said that it is sufficient for daily use because the water is supplied through the pipes only once a week and the quality is strongly varying ( Maharjan, 2014 ). Accordingly, only about two-thirds of households use pipe water for drinking and cooking. About the same share of households must make use also of jar water, while around 30% also make use of water from private tankers because of the intermittent supply of pipe water.

A share of around 40% of the respondents reported exposure to air pollution from vehicle emission, dust particles and solid waste ( Table 5 ). Regarding exposure to noise pollution, only noise from road traffic (50%) and crowds (32%) is reported from respondents and shows a significant disproportionate distribution. Noise pollution from industries and construction is only mentioned by a small number of respondents.

Comparing the six neighborhoods, the neighborhood N1 is least burdened by environmental hazards. Almost all households in N1 have access to pipe water (95%) ( Table 4 ), and the by far lowest share of households among the six neighborhoods is reporting their exposure to both vehicle emission (23%) and solid waste (4%). The level of air pollution from dust particles is at a similarly low level as neighborhood N5 ( Table 5 ). Also, neighborhood N1 is among the neighborhoods having the lowest shares concerning noise pollution. On the other hand, the most environmentally burdened neighborhood is N4. Though close to 95% of the households report that they have access to pipe water, <50% use this water for drinking and cooking purposes. In contrast, three-quarters of households have to buy jar water, often contaminated. More than half of the respondents reported exposure to air pollution from vehicle emissions (53%) and solid waste (52%) and two third reported exposure to noise pollution from road traffic.

The other neighborhoods are somewhat between these two extremes, being exposed more or less to some of the environmental burdens studied here. Respondents in N2 and N3 report a similarly low usage of pipe water (around 50%) and thus need to buy jar water to a high degree or even from private tankers, which are often more costly. Respondents from N2 report the highest share of exposure to air pollution from solid waste among the three sources, while respondents from N3 report the highest share of noise pollution from crowds. Respondents from the neighborhoods N5 and N6, on the other hand, report a relatively high share of access to pipe water (90%), and accordingly a high usage of pipe water for drinking and cooking (75%) while several households (87%) in N6 buy jar water as well, which indicates that supply of piped water is often intermittent. In terms of air pollution, N6 has the highest share of exposure from solid waste, which is most likely due to the close proximity location to the waste transfer station, which is in this neighborhood, while N5 reports a high share of exposure to noise pollution from road traffic.

These rather disproportionately distributed levels of exposure to environmental burdens between the neighborhoods result in statistically significant inequalities in reported health effects between neighborhoods ( Table 6 ). In neighborhood N1 the lowest shares of health effects are reported for waterborne diseases, allergic health effects from air pollution and noise pollution effects, while in neighborhoodN4 highest shares of health effects are reported for waterborne and respiratory diseases as well as a high share of other air pollution health effects ( Table 6 ). The highest numbers of reported health effects from air pollution in N6 (90%) can be plausibly linked to improper solid waste and management, as most of the households along the river reported bad odor, especially in the summertime when the water level is low. In N4, households complained about bad odor from the nearby vegetable market, particularly at garbage collection times. Health effects due to noise, such as headaches, irritation, etc., are reported highest by households in N3 and N4, whereas the least occurrence is reported in N1. For neighborhoodN3 this aligns with a high level of noise exposure from crowds that are reported, while respondents in N4 reported the highest share of exposure to noise from road traffic.

Vertical Inequalities in Perceived Exposures and Self-Reported Health Effects

Vertical environmental inequalities in Kathmandu in 2013 are being analyzed by comparing three socio-economic classes in all six neighborhoods. In contrast to horizontal inequalities, the analysis of vertical inequalities does not yield so many distinct inequalities. Statistically significant are only the levels of unequal exposure to air pollution from dust particles and solid waste ( Supplementary Tables 7 , 8 ).

In terms of access to drinking water sources, all three socioeconomic classes have in principal access to pipe water to a high degree (>90%). Likewise, they all report a similar usage of the three different water sources with 60–70% making use of pipe water as well as jar water and between 20 and 30% making also use of water from private tankers ( Supplementary Table 7 ). Consequently, no inequalities in sources of drinking water are statistically significant.

Exposure to the various sources of air pollution results in a somewhat mixed picture. Statistically significant is a slightly higher exposure to air pollution from dust particles for the HSEC cluster and higher exposure of LSEC households to air pollution from solid waste. The latter might relate to the high number of respondents reporting exposure to air pollution from solid waste in neighborhoods N4 and N6, as in both neighborhoods the share of households from LSEC is highest in the sample. In terms of noise pollution, all three socio-economic clusters report similar levels of exposure to the various noise sources, showing no statistically significant differences in levels of exposure. In summary, no socioeconomic class seems to be overall stronger exposed to environmental burdens than the other classes ( Supplementary Table 8 ).

Regarding self-reported health effects, households in LSEC have reported the highest percentage of morbidity due to waterborne and respiratory diseases. However, statistically significant inequalities can only be detected for to waterborne diseases ( Supplementary Table 9 ). Thus, it can be assumed that other factors contribute to varying health effects, such as behavioral factors (health behavior, smoking, etc.; Ploubidis and Grundy, 2011 ).

Changes in Environmental Inequalities in 2021 Compared to 2013

The analysis of changes in vertical and horizontal environmental inequalities in 2021 focuses on the four neighborhoods N1, 4, 5, and 6, as these showed the highest levels of inequalities in 2013. The survey covered a smaller sample; thus, the analysis is done qualitatively.

Horizontal Inequalities in Perceived Exposures and Self-Reported Health Effects

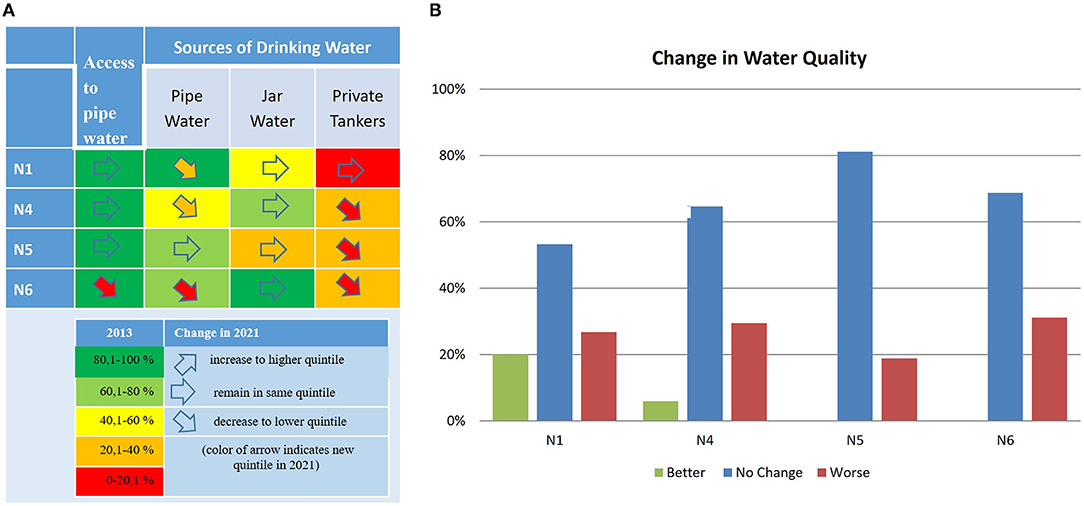

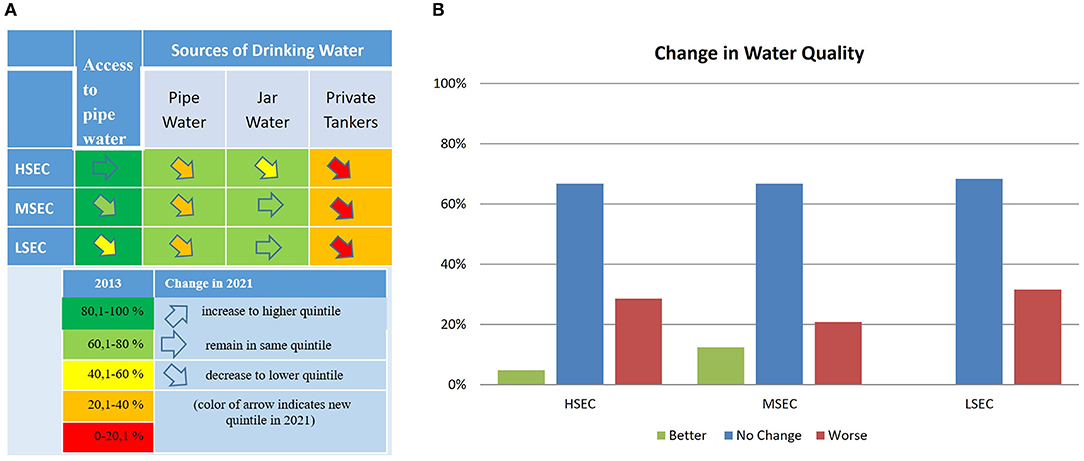

Figures 3 – 5 summarize the changes in perceived exposure between 2013 and 2021 for all three environmental burdens. While the principal access to pipe water has remained stable for three neighborhoods, only in N6 has it mainly decreased ( Figure 3 ). Nevertheless, the use of pipe water for drinking has decreased in three of the four neighborhoods, most strongly in N1 and N6, where they overly used pipe water in 2013. At the same time, the number of households reporting the use of jar water remained relatively stable in all four neighborhoods in 2021 ( Supplementary Table 10 ), which shows that overall, more jar water is consumed, particularly as the use of water from private tankers has also decreased in most neighborhoods. This reveals that the availability of safely managed drinking water following the SDG definition has worsened, as jar water is more expensive, often contaminated, and typically not available on the premise. Nevertheless, more than half of respondents in all four neighborhoods report that the drinking water quality has more or less stayed the same; only between 20 and 30% of respondents report that it has worsened ( Figure 3B ).

Figure 3 . Changes in access to pipe water sources of drinking water in neighborhoods. (A) Per water source, (B) overall water quality.

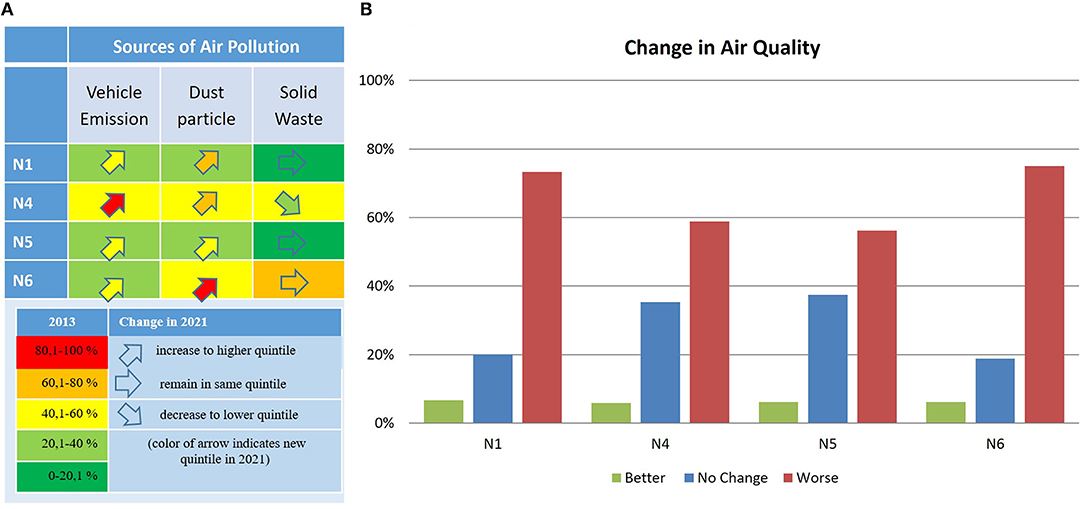

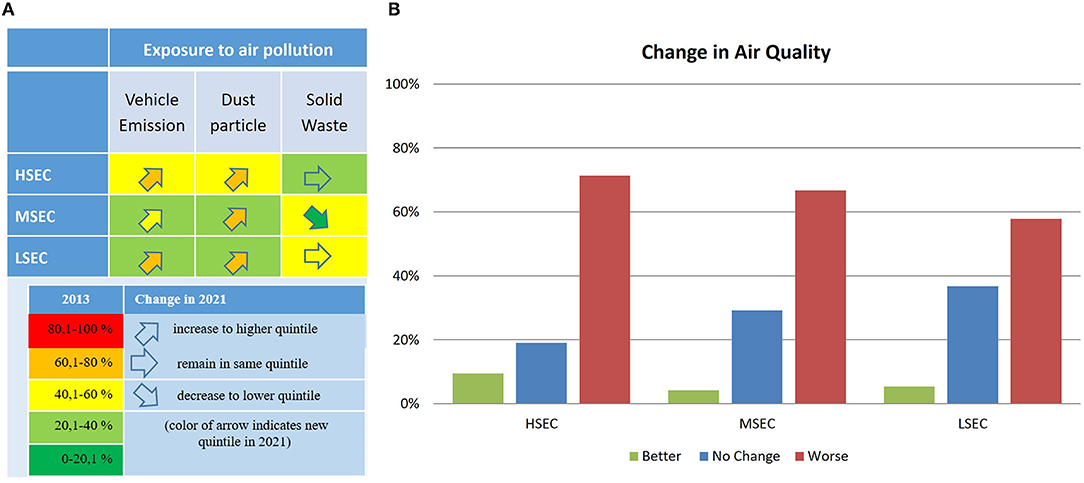

Regarding air pollution, most households in all four neighborhoods state that the exposure to vehicle emissions and dust particles has increased over the last 8 years ( Figure 4A ). In contrast, the exposure to solid waste remained relatively low in most neighborhoods and decreased in N4, but it is still a major burden of air pollution for respondents from N6, where the waste transfer station is located ( Supplementary Table 11 ). Overall, a majority of about 50–70 % in all four neighborhoods report that the air quality, in general, has worsened over the last 8 years ( Figure 4B ).

Figure 4 . Changes in exposure to air pollution in neighborhood. (A) Per source of air pollution, (B) overall air quality.

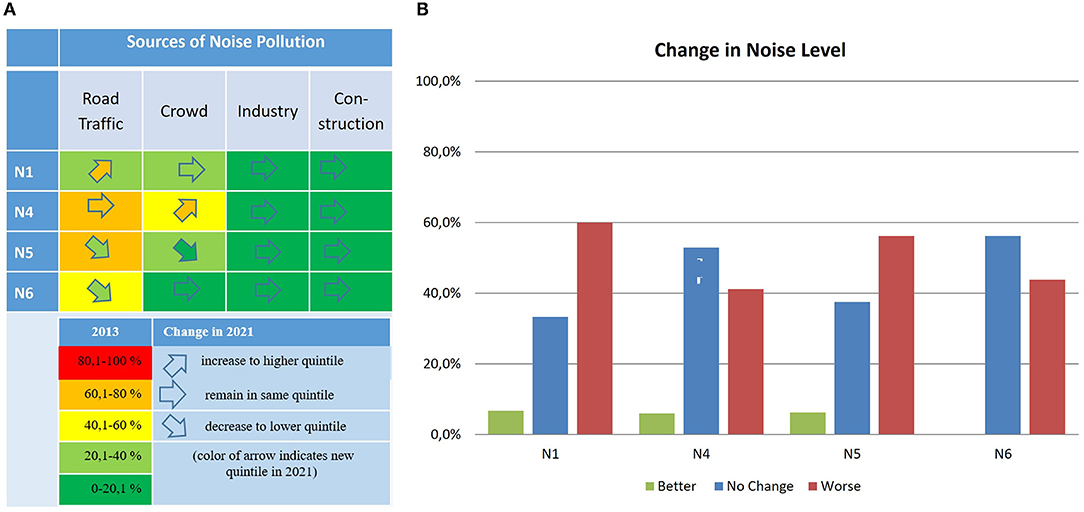

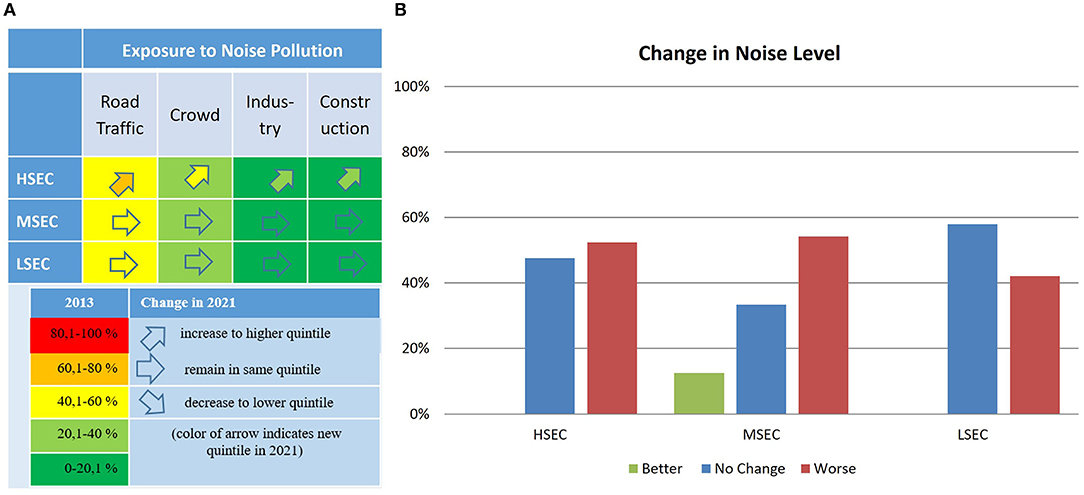

Regarding noise pollution, noise from road traffic is increasingly perceived as a burden in neighborhood N1, while it remained on the same high level in N4 and decreased in N5 and N6 ( Figure 5A ). Perceived exposure to noise from other sources remains similarly low in most neighborhoods, except in N4, where most respondents perceive exposure to noise from crowds as a burden ( Supplementary Table 12 ). Interestingly, in N1 and N5 respondents report that noise pollution in general has worsened ( Figure 5B ), which matches the perceived increase in noise pollution from road traffic in N1 but contradicts the perceived decrease of noise pollution in N5. This might indicate that households in N1 that mainly belong to the HSEC cluster are more aware and sensitive to noise pollution. Also, in N4 and N6 still a rather large share of around 40% report that the overall noise level has worsened, though only in N4 an increase in noise levels from crowds is reported.

Figure 5 . Changes in exposure to noise pollution in neighborhood. (A) Per source of noise pollution, (B) overall noise level.

Overall, Figures 3 – 5 shows that perceived exposure to environmental burdens in N1, which had the best-perceived environmental quality in 2013, has decreased in many aspects. At the same time, the situation in N4, which was the worst neighborhood in 2013, has also worsened for the use of pipe water for drinking, air pollution from vehicles and dust, and noise pollution from crowds. In N5 and N6 air pollution worsened, noise pollution improved, and water access worsened but only for N6. In summary, we can conclude that the exposure to environmental burdens has increased in general and horizontal environmental inequalities between neighborhoods in 2013 persisted in 2021.

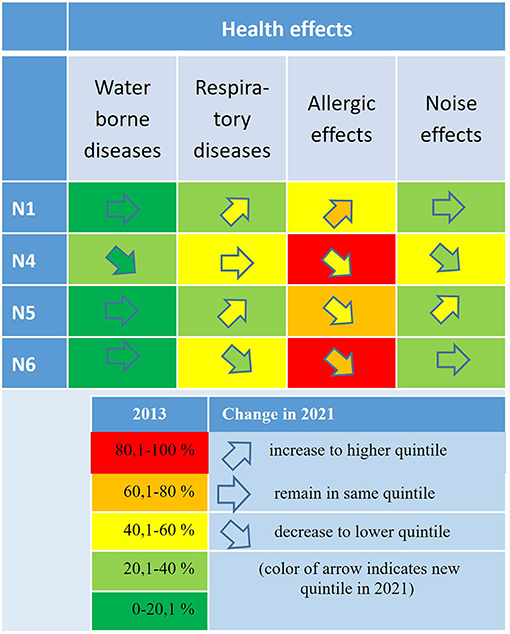

Regarding the self-reported health effects, air pollution-related effects (respiratory diseases, allergic reactions) are still most often reported overall, which matches with the perceived increase in exposure to air pollution ( Figure 6 , Supplementary Table 13 ). The share of reported waterborne diseases has decreased or remained low in most neighborhoods. Also reported health effects from noise pollution remained on a low level similar to 2013, except in N5 where they increased significantly. As respondents from N5 also reported an increase in air pollution from vehicle emissions, this is probably due to the increasing amounts of road traffic in the neighborhood, though exposure to noise pollution from road traffic was not significantly mentioned above.

Figure 6 . Changes in reported health effects per neighborhood.

A similar picture is found concerning the changes in vertical inequalities between socio-economic clusters in 2021 compared to 2013. Overall, the use of safe drinking water sources has worsened, and air and noise pollution levels have increased for all three socio-economic groups. At the same time, inequalities between the three groups have not increased.

The access to pipe water remained high for the HSE cluster, whereas it has decreased for the other two socio-economic clusters, strongest for the LSEC ( Figure 7A ). However, the use of pipe water for drinking has significantly decreased for all three SECs. The LSEC cluster includes the lowest share of respondents using pipe water and the highest percentage of respondents buying jar water ( Supplementary Table 14 ). Nevertheless, the overall consumption pattern of the three SECs in terms of water use is similar with around 20–40% using pipe water, 60–70% buying jar water and a minority of <20% buying water from private tankers and indicating no inequalities ( Supplementary Table 14 ). In line with that, around 65% in all three groups report that the water quality has more or less stayed the same ( Figure 7B ).

Figure 7 . Changes in access to pipe water sources of drinking water in socio-economic clusters. (A) Per water source, (B) overall water quality.

Overall, a high share of respondents reported that they were exposed to air pollution from vehicle emissions and dust particles in 2021 ( Supplementary Table 15 ). In line with that, the perceived exposure to vehicle emissions and dust has increased significantly for all the three SECs ( Figure 8A ). A majority of around 60% in each cluster reports that the overall air quality has worsened ( Figure 8B ). Nevertheless, two distinctions in perception of exposure to air pollution can be derived from Figure 8 : First, the HSEC cluster has the largest share of respondents reporting a worsening of the air quality in general ( Figure 8B ) and with respect to vehicle emissions and dust particles ( Supplementary Table 15 ), which might indicate that this group is least used to it and most aware of the changes. Second, the LSEC is the cluster most burdened still with air pollution from solid waste. A reason might be that solid waste stations are allocated in particular locations within the city, which high-income people consequently least prefer.

Figure 8 . Changes in exposure to air pollution in socioeconomic clusters. (A) Per source of air pollution, (B) overall air quality.

A similar observation can be made concerning exposure to noise pollution from various sources. For LSEC and MSEC, the reported level of exposure remained pretty much the same for all sources of noise pollution, but perceived exposures for respondents from HSEC have increased in 2021 for all four sources ( Figure 9A ). In line with that higher share of respondents from the HSEC cluster stated the overall increase in noise levels ( Figure 9B , Supplementary Table 16 ).

Figure 9 . Changes in exposure to noise pollution in socio-economic clusters. (A) Per source of noise pollution, (B) overall noise level.

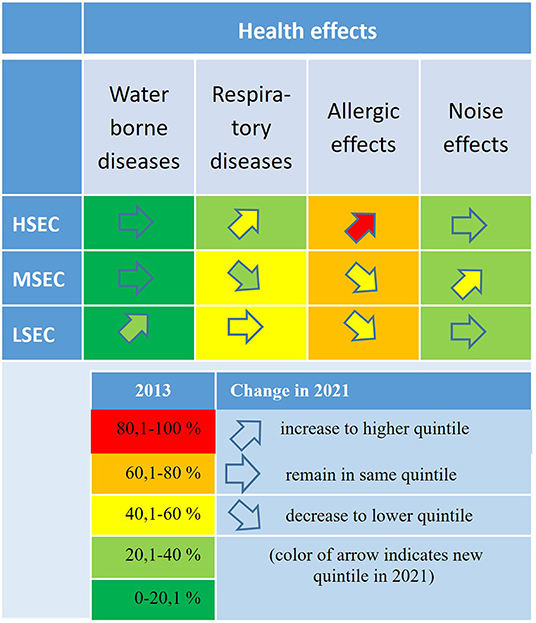

Concerning health effects, the percentages of reported waterborne diseases in 2021 remain on a similarly low level as in 2013 for all three clusters ( Figure 10 ). Nevertheless, members of the LSEC still report the highest shares of waterborne diseases ( Supplementary Table 17 ). On the other hand, respondents from HSEC report an increase of air pollution-related problems like respiratory diseases and other allergic reactions, which is in line with the high percentage of reported exposure. All three groups conveyed health effects from noise pollution to a similar degree, with the MSEC being slightly higher.

Figure 10 . Changes in reported health effects per socio-economic cluster.

Drivers of Changes and Actions to Mitigate Environmental Inequalities

The DPSEEA Framework ( WHO, 1999 ) we applied in this study to analyze environment inequalities is meant to support the understanding of driving forces of exposure to environmental burdens and health impacts and to support decision making on action to reduce environmental burdens ( Hambling et al., 2011 ). In the following, we analyze drivers that contributed to the changes as perceived by the respondents, actions that households have taken to mitigate the level of the environmental burden, and actions they have perceived as taken by relevant authorities.

Most of the households report that the overall water quality has remained the same between 2013 and 2021. The worsening of the water quality is by the respondents mainly attributed to the earthquake in 2015, as the damage of water pipes due to the earthquake worsened the already insufficient piped water supply ( Shrestha et al., 2016b ) forcing households to shift to jar water. However ( Pradhan et al., 2020 ), claim that the main reason for such infrastructure deficiencies, not only for water supply but other infrastructures as well, is the rapid urbanization. To mitigate the limited water availability after the earthquake, the city provided water at a discounted rate via tankers in neighborhoods N5 and N6. In the longer run, people are expecting a better water supply from the “Melamchi water supply project,” a government-led drinking water project initiated in 1998 and completed in 2021 to divert fresh water from Melamchi River to Kathmandu valley. The changes in reported waterborne diseases indicate an increasing awareness of the poor water quality as most households are either boiling or filtering or both before drinking water.

Regarding the perception of air quality change, around three-fourths of the households in N1 and N6 and more than half of the households in N4 and N5 reported worsening air quality in the last 7 years. According to the respondents, the primary reasons are the increase in number of cars on the streets in Kathmandu, creating emissions and transporting dust particles, and poor solid waste management. One respondent in N4 living near the main road complained, “We close our windows to prevent from air pollution; however, it cannot be shut for all the time, so we have to suffer from the pollution,” another one stated “sometimes when the waste is not picked up for several days, the condition is very bad, and additionally, we feel the smell from the river.” In neighborhood N5, several new constructions being erected after the earthquake are reported on contributing to air pollution from dust particles. In N6 respondents reported that the road extension project on the riverside has caused many adverse effects such as trees being cut and vehicle movements increasing on unpaved roads. Moreover, the increase in workshops, garment factories, and scrap factories are also mentioned to create additional air pollution. The only governmental action to mitigate air pollution from dust reported by households has been paving roads with asphalt in the last years. However, these works were carried out mostly on major roads and the secondary roads are mostly left unpaved leading to increasing dust pollution.

With respect to socio-economic clusters, more than half of the households of the HSEC cluster report an overall worsening of air quality, whereas around 26% of households in LSEC do so. The statements regarding the reasons for change manifest the above assumption that there are differences in awareness of bad environmental quality between SECs. One respondent from LSEC stated, “It does not matter how the environment condition is, we just need to have money for our daily life.” Another one responded, “We don't feel affected by environmental conditions as we are habituated with it.” Another respondent, a garbage collector, said that she is adjusted to smell from the garbage center and nearby river.

According to most of the respondents, the increase in number of vehicles is the major cause for the increase in noise level in all neighborhoods. The majority of households living near the main road reported that they suffer from loud noises due to traffic. The government introduced “no horn policy,” but this is not effective according to some households ( Chauhan et al., 2021 ). Also, road expansions have led to a transformation of areas attracting small-scale workshops, industries, and garments factories to move into the neighborhood. Consequently, loading/ unloading activities of heavy vehicles for industries have increased together with an increase in vehicle flow, resulting in higher noise disturbances.

Discussion and Conclusion

Patterns of horizontal and vertical inequalities in kathmandu.

The analysis of environmental inequalities in Kathmandu, Nepal in 2013 resulted in several horizontal inequalities between the different neighborhoods, confirming the spatiality of inequalities ( Wei, 2017 ) diagnosed for Asia. In particular, inequalities were found in the use of drinking water sources, exposure to air pollution from vehicle emissions and solid waste, and exposure to noise pollution from road traffic and crowds. Respondents from neighborhood N4 were mostly reporting exposure toward the various environmental burdens. Many of them were burdened by multiple sources ( Morello-Frosch et al., 2011 ), while respondents from N1 reported the least environmental exposure. From the other neighborhoods, neighborhood N5 is particularly burdened by noise pollution from road traffic and N6 by air pollution from solid waste. Also, the self-reported health effects in 2013 revealed statistically significant inequalities between the various neighborhoods, supporting earlier studies that associations between levels of exposure to environmental burden and health effects exist in Kathmandu ( Gurung et al., 2017b ). Neighborhood N1 is showing the least reported health effects among all neighborhoods, while N4 is among the top group with the most self-reported health effects for all health effects.

On the other hand, vertical inequalities between the three socio-economic groups could not be identified clearly, validating earlier findings that the socio-economic status does not have a strong influence ( Gurung et al., 2017b ). Statistically significant inequalities were only found in exposure to air pollution, with the HSEC reporting the highest levels of exposure to dust particles, while the LSEC is reporting the highest level of exposure to air pollution resulting from solid waste. However, the socio-economic dimension of inequalities is inherent in the analysis of vertical inequalities between neighborhoods because the composition of sample households in terms of socio-economic profile differs between the six neighborhoods. Neighborhood N1, which shows the lowest levels of exposure, has more than 60% of the sample from the HSEC cluster, while neighborhoods N4, 5, and 6 have a relatively high share of LSEC households in the sample and are all burdened disproportionally more by certain environmental stressors. Thus, we can conclude that horizontal inequalities between neighborhoods also affect socio-economic groups disproportionately with environmental burdens because the two cannot be strictly separated from each other. In conclusion, both need to be addressed jointly through integrated measures to reduce environmental inequalities ( Kalasa et al., 2021 ).

The analysis of perceived exposure to environmental burdens in 2021 and the changes in comparison to 2013 results in two main findings. First, the perceived exposure to environmental burdens has predominantly increased since 2013 in all neighborhoods. The access to safe and high-quality drinking water has worsened in most neighborhoods, mainly explained by the earthquake in 2015 that destroyed several water pipes. Most strongly, exposure to air pollution from vehicle emissions and dust particles has increased as a result of an increase in urbanization and motorization and a lack of stringent measures from relevant authorities. The same reason applies to the increase in exposure to noise, which is predominantly perceived by respondents in the better-off neighborhood N1.

Second, environmental inequalities between the different neighborhoods and socio-economic groups have not changed significantly compared to 2013. Given the overall increase in levels of exposure as described above, we can rather say that existing inequalities between different neighborhoods have somewhat diminished. This conclusion is supported by the finding that the reported health effects in the better of neighborhood N1 have increased, while they have decreased in the other neighborhoods. In that sense, we see a reduction of inequalities at a low level, not in the way that the disproportionately burdened areas improved in environmental qualities, but that the better-off areas get worse.

The analysis of vertical inequalities between socio-economic groups points at another aspect in environmental justice studies referred to as procedural justice, i.e., the fairness of environmental policy making and the ability and rights of all groups to raise concerns and be heard ( Walker, 2009 ). The analysis in Section Vertical Inequalities in Perceived Exposures and Self-Reported Health Effects showed that respondents from the HSEC are reporting increasing levels of exposure more often, particularly in relation to air pollution from vehicles and dust and noise pollution from road traffic, than respondents from the MSEC or LSEC groups. Similar patterns were also found in air pollution exposure studies in other cities from the Global South ( Becerra et al., 2020 ). The assumption that this is an indication of unequal abilities and chances to raise concerns about the individual living conditions is corroborated with statements from respondents, in which high acceptance and habituation are detected from these groups owing to their occupation and their priority to livelihood, especially with respect to air pollution ( Navarro, 2017 ).

Policies and Plans to Reduce Environmental Inequalities in Kathmandu

This study shows that environmental inequalities in Kathmandu have not been reduced between 2013 and 2021, as demanded in SDG 10, but rather persisted. Moreover, also concerning SDG 2 (good health and wellbeing), SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation), and SDG 11.6 (environmental impacts of cities, particularly air pollution), no improvements can be identified based on the perception of the interviewed citizens. This can be partly explained by natural disasters, i.e., the earthquake affecting the water pipe system, but is mainly due to impacts resulting from the ongoing urbanization, industrialization and motorization, as it can be seen in many countries and cities of the Global South ( Sen Roy, 2018 ). Moreover, a recent study identified shortcomings of environmental policymaking in Nepal and recommended novel transdisciplinary policymaking approaches to solve the country's complex environmental issues and development imperatives ( Aryal et al., 2021 ).

The analysis of causes of exposure to environmental burdens and health effects, as reported by the respondents, reveals that mainly spatial factors of the urban fabric and its dynamics contribute as driving forces to the experienced burdens. The leading causes mentioned are the

• intermittent water supply through pipes owing to the earthquake;

• intensification of traffic and vehicles on both primary roads as well as secondary roads resulting in higher noise as well as air pollution;

• changes in land use structures, i.e., more commercial and industrial activities in residential areas resulting in higher noise levels;

• locational factors within neighborhoods such as proximity to garbage collection points, the vegetable market, or the river that are often unmanaged;

• increase of garbage in the streets and poorly implemented solid waste management.

As the above-reported factors are all related to the physical environment of cities and its management, urban planning and management-related approaches and interventions are most suitable to mitigate inequalities ( Flacke et al., 2016 ). However, though local governments are responsible for preparing urban plans including land use plans, they lack legal instruments to control land use development effectively ( Pradhan et al., 2020 ). Given the identified interrelations between horizontal and vertical inequalities new spatial planning approaches need to consider the vulnerability of the population ( Köckler, 2014 ).

The small-scaled analysis of environmental inequalities at the neighborhood level also shows that differences between neighborhoods exist. Moreover, answers from respondents on reasons for change even illustrate intra neighborhood differences in levels of exposure. While the exposure to noise and air pollution from cars is perceived as high on the main roads, it is way less so far away from it. Likewise, respondents who live close to the river particularly articulated exposure to air pollution from solid waste more frequently. Thus, to mitigate such burden and the linked inequalities, small–scaled planning approaches are needed to target interventions at these specific locations.

Limitations of the Study