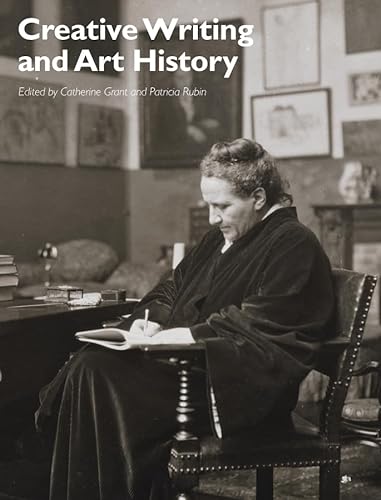

Creative Writing and Art History

- The Courtauld Institute of Art

- Department of History of Art

Research output : Other contribution

Access to Document

- https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/15886/

Fingerprint

- Writing History Arts & Humanities 100%

- Creative Writing Arts & Humanities 85%

- Art History Arts & Humanities 70%

- Historical Writing Arts & Humanities 28%

- Art Arts & Humanities 26%

T1 - Creative Writing and Art History

A2 - Grant, Catherine

A2 - Rubin, Patricia

PY - 2012/3/1

Y1 - 2012/3/1

N2 - Creative Writing and Art History considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing. Essays range from the analysis of historical examples of art historical writing that have a creative element to examinations of contemporary modes of creative writing about art.

AB - Creative Writing and Art History considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing. Essays range from the analysis of historical examples of art historical writing that have a creative element to examinations of contemporary modes of creative writing about art.

M3 - Other contribution

PB - Wiley-Blackwell

- Arts & Photography

- History & Criticism

Your Amazon Prime 30-day FREE trial includes:

Unlimited Premium Delivery is available to Amazon Prime members. To join, select "Yes, I want a free trial with FREE Premium Delivery on this order." above the Add to Basket button and confirm your Amazon Prime free trial sign-up.

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, you will be charged £95/year for Prime (annual) membership or £8.99/month for Prime (monthly) membership.

Return this item for free

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. For a full refund with no deduction for return shipping, you can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition.

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet or computer – no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Creative Writing and Art History (Art History Special Issues) Paperback – 2 Mar. 2012

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing

- Covers a diverse subject matter, from late Neolithic stone circles to the writing of a sentence by Flaubert

- The collection both contains essays that survey the topic as well as more specialist articles

- Brings together specialist contributors from both sides of the Atlantic

- ISBN-10 1444350390

- ISBN-13 978-1444350395

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Wiley-Blackwell

- Publication date 2 Mar. 2012

- Language English

- Dimensions 20.83 x 1.52 x 27.18 cm

- Print length 208 pages

- See all details

Product description

From the inside flap.

This collection of articles considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing, from the creative writing of art history to dialogues between styles of creative and art-historical writing. The subject matter covered is diverse, from late Neolithic stone circles to the writing of a sentence by Flaubert. Yet a number of questions circulate – in particular, the stakes involved in various forms of art-historical writing, and the claims made for the art historian’s interpretation. Some authors analyse historical examples of art-historical writing that have a creative element, others explore conversations between literature and art history, whilst others attempt their own modes of creative writing about art. The topics covered within this varied collection include Paul Gauguin’s collages of quotations, Sophie Calle’s collaboration with Paul Auster, Henry James’ portraiture, Bernard Berenson’s fictional artist ‘Amico di Sandro’, Virginia Woolf’s ‘visual’ writing, Pablo Picasso’s solar mythology as re-written by Georges Bataille , and creative writing in the ‘middle voice’.

From the Back Cover

This collection of articles considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing, from the creative writing of art history to dialogues between styles of creative and art-historical writing. The subject matter covered is diverse, from late Neolithic stone circles to the writing of a sentence by Flaubert. Yet a number of questions circulate – in particular, the stakes involved in various forms of art-historical writing, and the claims made for the art historian’s interpretation. Some authors analyse historical examples of art-historical writing that have a creative element, others explore conversations between literature and art history, whilst others attempt their own modes of creative writing about art. The topics covered within this varied collection include Paul Gauguin’s collages of quotations, Sophie Calle’s collaboration with Paul Auster, Henry James’ portraiture, Bernard Berenson’s fictional artist ‘Amico di Sandro’, Virginia Woolf’s ‘visual’ writing, Pablo Picasso’s solar mythology as re-written by Georges Bataille , and creative writing in the ‘middle voice’.

About the Author

Catherine Grant is Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. She co-ordinated the Writing Art History project at the Courtauld Institute of Art with Patricia Rubin and is the co-editor (with Lori Waxman) of Girls! Girls! Girls! in Contemporary Art (2011).

Patricia Rubin is Judy and Michael Steinhardt Director of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She is a member of the International Advisory Board of Art History and the author of Giorgio Vasari: Art and History (1995), Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s (1999), and Images and Identity in Fifteenth-Century Florence (2007), and co-author of Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s (1999).

Product details

- Publisher : Wiley-Blackwell; 1st edition (2 Mar. 2012)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 208 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1444350390

- ISBN-13 : 978-1444350395

- Dimensions : 20.83 x 1.52 x 27.18 cm

- 2,710 in Art Criticism

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings, help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyses reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from United Kingdom

Top reviews from other countries.

- UK Modern Slavery Statement

- Sustainability

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell on Amazon Handmade

- Sell on Amazon Launchpad

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect and build your brand

- Associates Programme

- Fulfilment by Amazon

- Seller Fulfilled Prime

- Advertise Your Products

- Independently Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Instalments by Barclays

- Amazon Platinum Mastercard

- Amazon Classic Mastercard

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Payment Methods Help

- Shop with Points

- Top Up Your Account

- Top Up Your Account in Store

- COVID-19 and Amazon

- Track Packages or View Orders

- Delivery Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Amazon Mobile App

- Customer Service

- Accessibility

- Conditions of Use & Sale

- Privacy Notice

- Cookies Notice

- Interest-Based Ads Notice

Creative Writing

History of Creative Writing at Princeton

“For more than eighty years, Princeton’s Creative Writing Program has brought generation of writers and undergraduates together in the classroom. We are committed to offering a nurturing place for all the students to explore their literary and artistic curiosities.” — Yiyun Li, Director of Creative Writing

In 1939, Dean Christian Gauss approached the Carnegie Foundation to help Princeton University focus on the cultivation of writers and other artists. The Foundation promptly responded with a generous five-year grant of $75,000 to pay the salaries of “practitioners in the arts.” Gauss convened and chaired a faculty committee that included Professor Coindreau (French), Professors Davis and De Wald (Art), Professor Welch (Music), and Professors Hudson and Thorp from the English Department. They defined the program’s mission, “to allow the talented undergraduates to work in the creative arts under professional supervision while pursuing a regular liberal arts course of study, as well as to offer all interested undergraduates an opportunity to develop their creative faculties in connection with the general program of humanistic education.”

That same year, Professor Thorp nominated poet and critic Allen Tate as the first Resident Fellow in Creative Writing, and Tate began teaching the following September. He was to “act as general adviser to undergraduates interested in writing and will be in general charge of the new plan designed to further the work of entering freshman in creative writing.” The following year, the Creative Arts Committee appointed Tate for a second year and allowed him to invite poet and critic Richard P. Blackmur to assist him. In 1942, the Committee appointed George Stewart, Princeton class of 1917, as Resident Fellow and, over the course of the nearly 20 years that followed, brought a succession of poets, writers, and critics to teach in the program under the Committee Chairman Professor Arthur Szathmary and the Program Director R.P. Blackmur. Among these were John Berryman, Joseph N. Frank, Delmore Schwartz, William Meredith, Robert Fitzgerald, Sean O’Faolain, Richard Eberhart, Kingsley Amis, and Philip Roth. Today, this program has evolved into the Hodder Fellowship .

The Creative Arts Program went through a series of evolutions, the most notable of which occurred under the leadership of Edmund Keeley, Charles Barnwell Straut Class of 1923 Professor of English and Professor of Creative Writing, Emeritus . Professor Keeley was responsible for changing the format of creative writing courses from precepts, with students meeting individually with their adviser once a week to discuss their writing, to the current workshop format, where the focus is on students sharing their work with other students under the guidance of faculty, supplemented with readings in literature and individual conferences. Professor Keeley introduced the workshop format on the basis of his experience during a sabbatical year at the Iowa Writers Workshop, one of the earliest creative writing programs in the country.

“For those who have tended to think that Princeton has only recently put such emphasis on the creative and performing arts, it’s good to be reminded that the Creative Writing Program has made such a large impact for so very long. It is, quite simply, the best in the country.” — Paul Muldoon Howard G.B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Creative Writing

Theodore Weiss joined Keeley in 1966 and together, the two continued to expand the program, bringing in such distinguished writers as Elizabeth Bowen, Thom Gunn, Anthony Burgess, Galway Kinnell, Joyce Carol Oates, and Russell Banks. “The Creative Writing Program,” Keeley remarked, “was primarily to teach students how to read as a writer might read and to begin writing with knowledge of the creative process. For many students, taking creative writing courses at Princeton was also how they first discovered literature, or at least a passion for literature.”

Under Keeley’s leadership the program moved to the former Nassau Street School at 185 Nassau Street, where it expanded with the rapid growth of student interest in the creative arts in the early seventies. Edmund Keeley was succeeded as director by award-winning poet James Richardson (1981 to 1990), whose period as director saw the arrival of Toni Morrison, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature during her Princeton tenure, and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Paul Muldoon. Following Richardson, the program was briefly directed by A. Walton Litz (1990 to 1992), and then by Paul Muldoon (1993 to 2002), and Edmund White (2002 to 2006).

On January 20, 2006, in a report presented to the University’s Board of Trustees, former University President Shirley Tilghman heralded a sweeping initiative for Princeton “not only to expand its programs in the creative and performing arts, but to establish itself as a global leader in the quality of its offerings and in their integration into a broader liberal arts education.”

The result was the formation of a new Center for the Creative and Performing Arts, thereafter named the Lewis Center for the Arts in honor of its lead patron, Peter B. Lewis ’55 .

The Lewis Center brought together Princeton’s academic programs in Creative Writing , Dance , Theater , Music Theater , Visual Arts and the Princeton Atelier , at 185 Nassau Street, and connected them to partners like the Department of Music and the Princeton University Art Museum .

With the creation of the Lewis Center and the University’s investment in the arts, the Program in Creative Writing has seen further significant growth: from 2007-2018 the number of creative writing course offered have grown 69%, enrollment in courses has doubled, and the number of students graduating with a certificate in Creative Writing has grown by 87%. This expansion of the program was led by a new generation of writers serving as Director of the program: Chang-rae Lee (2006 to 2010), Susan Wheeler (2010 to 2015), Tracy K. Smith (2015 to 2019), Jhumpa Lahiri (2019-2022), and Yiyun Li (current). Starting with the Class of 2025, students can pursue a minor (rather a certificate) in Creative Writing.

By 2010 the Lewis Center’s programs outgrew 185 Nassau Street and Creative Writing moved to New South, occupying an entire floor to accommodate expanded space for writing seminars and faculty offices. In 2017 the new Lewis Arts complex opened next to New South in the new “arts neighborhood” with much of the Program in Creative Writing’s public programming scheduled in the new theaters and studios of the arts complex.

In more recent years the core and guest faculty has included Simon Armitage, John Berryman, Jeffrey Eugenides, Robert Fitzgerald, David E. Kelley, John McPhee, Lorrie Moore, Neel Mukherjee, Philip Roth, Claudia Rankine, Erika Sánchez, Delmore Schwartz, Kevin Young, and Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa.

Over the years, the Program’s public programming has also grown to include the Althea Ward Clark W’21 Reading Series in which writers of national and international distinction visit campus throughout the year to read and discuss their work; the C.K. Williams Reading Series that showcases senior students of the Program in Creative Writing alongside established writers as special guests; awarding of the Theodore H. Holmes ’51 and Bernice Holmes National Poetry Prize; presentation of the Theodore H. Holmes ‘51 and Bernice Holmes Lecture; the Leonard L. Milberg ’53 High School Poetry Prize; and the biennial Princeton Poetry Festival that features poets from around the world in a two-day festival of readings, lectures and panel discussions.

Currently, the core faculty includes award-winning writers Michael Dickman, Aleksandar Hemon, A.M. Homes, Ilya Kaminsky, Christina Lazaridi, Yiyun Li, Paul Muldoon, Patricia Smith, Kirstin Valdez Quade and Susan Wheeler.

Over the past 80 years, many now distinguished and successful writers have graduated from the Program including Jonathan Ames ’87, Catherine Barnett ’82, Jane Hirshfield ’73, Boris Fishman ’01, Kristiana Kahakauwila ‘03, Galway Kinnell ’48, Walter Kirn ’83, William Meredith ’40, W. S. Merwin ’48, Emily Moore ’99, Jodi Picoult ’87, Jonathan Safran Foer ’99, Julie Sarkissian ’05, Akhil Sharma ’92, Whitney Terrell ’91, Monica Youn ’93, and Jenny Xie ’08, among many others.

Fellowships

Learn more about the Hodder Fellowship and Princeton Arts Fellows .

Receive Lewis Center Events & News Updates

Items related to Creative Writing and Art History

Creative writing and art history - softcover.

This specific ISBN edition is currently not available.

- About this title

- About this edition

- Considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing

- Covers a diverse subject matter, from late Neolithic stone circles to the writing of a sentence by Flaubert

- The collection both contains essays that survey the topic as well as more specialist articles

- Brings together specialist contributors from both sides of the Atlantic

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

This collection of articles considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing, from the creative writing of art history to dialogues between styles of creative and art-historical writing. The subject matter covered is diverse, from late Neolithic stone circles to the writing of a sentence by Flaubert. Yet a number of questions circulate – in particular, the stakes involved in various forms of art-historical writing, and the claims made for the art historian’s interpretation. Some authors analyse historical examples of art-historical writing that have a creative element, others explore conversations between literature and art history, whilst others attempt their own modes of creative writing about art. The topics covered within this varied collection include Paul Gauguin’s collages of quotations, Sophie Calle’s collaboration with Paul Auster, Henry James’ portraiture, Bernard Berenson’s fictional artist ‘Amico di Sandro’, Virginia Woolf’s ‘visual’ writing, Pablo Picasso’s solar mythology as re-written by Georges Bataille , and creative writing in the ‘middle voice’.

Catherine Grant is Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. She co-ordinated the Writing Art History project at the Courtauld Institute of Art with Patricia Rubin and is the co-editor (with Lori Waxman) of Girls! Girls! Girls! in Contemporary Art (2011).

Patricia Rubin is Judy and Michael Steinhardt Director of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She is a member of the International Advisory Board of Art History and the author of Giorgio Vasari: Art and History (1995), Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s (1999), and Images and Identity in Fifteenth-Century Florence (2007), and co-author of Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s (1999).

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- Publisher Wiley-Blackwell

- Publication date 2012

- ISBN 10 1444350390

- ISBN 13 9781444350395

- Binding Paperback

- Edition number 1

- Number of pages 208

- Editor Grant Catherine , Rubin Patricia

Convert currency

Shipping: US$ 2.64 Within U.S.A.

Add to Basket

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Creative writing and art history.

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 12251252-n

More information about this seller | Contact seller

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Language: ENG. Seller Inventory # 9781444350395

Creative Writing and Art History Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 1444350390

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # e0356d632522e7b4a72b840c9fa8ae60

Book Description Paperback / softback. Condition: New. New copy - Usually dispatched within 4 working days. Creative Writing and Art History considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing. Essays range from the analysis of historical examples of art historical writing that have a creative element to examinations of contemporary modes of creative writing about art. Seller Inventory # B9781444350395

Creative Writing and Art History (Art History Special Issues)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 6666-WLY-9781444350395

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 1st edition. 208 pages. 11.00x8.25x0.75 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # __1444350390

Book Description Condition: New. Creative Writing and Art History considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing. Essays range from the analysis of historical examples of art historical writing that have a creative element to examinations of contemporary modes of creative writing about art. Editor(s): Grant, Andrew; Grant, Catherine; Rubin, Patricia. Series: Art History Special Issues. Num Pages: 208 pages, Illustrations. BIC Classification: ABA; AC. Category: (P) Professional & Vocational. Dimension: 273 x 211 x 14. Weight in Grams: 716. . 2012. 1st Edition. Paperback. . . . . Seller Inventory # V9781444350395

Book Description Condition: New. Creative Writing and Art History considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing. Essays range from the analysis of historical examples of art historical writing that have a creative element to examinations of contemporary modes of creative writing about art. Editor(s): Grant, Andrew; Grant, Catherine; Rubin, Patricia. Series: Art History Special Issues. Num Pages: 208 pages, Illustrations. BIC Classification: ABA; AC. Category: (P) Professional & Vocational. Dimension: 273 x 211 x 14. Weight in Grams: 716. . 2012. 1st Edition. Paperback. . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Seller Inventory # V9781444350395

There are more copies of this book

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Howe Writing Center

Writing in art history.

This guide provides a brief introduction to writing in the field of art history through the lens of threshold concepts. It includes:

- A statement of threshold concepts in art history

“So you’re taking an art history course”: A Description of Writing Characteristics Valued in Art History

- “This is how we write and do research in art history”: Resources for Writers

A Statement of Threshold Concepts in Art History

“Seeing comes before words, the child looks and recognizes before it can speak.” (John Berger, Ways of Seeing )

“Seeing establishes our place in the world.” (John Berger, Ways of Seeing )

“We do not explain pictures: we explain remarks about pictures.” (Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention )

Threshold Concept #1: Connections between Looking and Writing

The statement: It is not easy to write what you see. If seeing establishes our place in the world, art history is a tool to make sense of the visual world in which we all live.

What this means for our students: Looking well is a time-intensive and skilled practice. Visual information is not self-evident, and writing about what is seen involves thinking about how and why visual information is understood in a particular way.

Where/how we teach this Threshold Concept : Visual analysis assignment in ART 285; Short essays in 100-level courses. Writing about and describing what is seen is also modeled in class examples and discussions.

Threshold Concept #2: Context Matters

The statement: All art is conditioned by historical and cultural circumstances. Art history endeavors to understand these circumstances or contexts in order to explain the crucial role art occupies in humanity. The contexts that produced the work of art help art historians contextualize why art matters.

What this means for students: Art is never understood by its visual appearance or form alone. The goal of art history is to place a work of art within its historic, religious, political, economic, and aesthetic contexts. Students should also understand that various contexts do not stand on their own, but usually overlap. Only by unpacking the circumstances that give rise to a work of art is one able to communicate how art matters and how its meanings change through time and place.

Where/how we teach this Threshold Concept: 100-level courses engage with this concept while upper-level courses provide students with practical applications through the execution of research and writing assignments.

Threshold Concept #3: Frames of interpretation

The statement: Art historical writing involves multiple frames of interpretation and—perhaps more importantly—the ability to hold multiple frames in suspension at the same time while producing an original argument. While there is no one “right” interpretation of a work of art, there are interpretations and scholarly arguments that have more quality or staying power than others. (See below for examples of quality art historical arguments)

What this means for students: Research done in preparation for writing is framed not only as a search for facts to be relayed to the reader through writing, but also as discourses of interpretation within which the writer seeks to interject. This kind of writing involves a conversation with artworks, contexts, and prior interpretations and scholarship in service of an original argument.

Where/how we teach this Threshold Concept: Research papers in upper level courses, at the end of Art 285 and the Art 480 seminar, and as part of the capstone project and honors theses ideally move students through this threshold. Being able to do this involves building upon awareness and skills gained in Threshold Concepts 1 and 2.

Art history is rooted in the study of visual, performed, and material expression. Goals for our work include interpretation, producing frameworks, narratives, and histories to understand the human experience and condition, and the expansion of what is considered “art”. We want you to know that there are some key things that we value in our field. We value the complexity of seeing and the diversity of different ways of seeing . We tend not to value or prioritize subjective opinion and unsubstantiated claims.

What is considered effective or good writing in our field varies by genre and purpose, but overall we expect to see:

- a direct address of the subject or work of art.

- an interpretive analysis of a work of art backed by research from credible sources.

- engagement with significant interpretive and theoretical frameworks.

Writers in our field must provide evidence for their claims. We understand evidence to include:

- Formal analysis. Formal analysis is the description of the visual and material features of an object to support an argument. It can include a consideration of color, line, size, weight, form, shape, depth. Formal analysis is often a place to generate questions for research.

- Biographical records or artists’ statements

- Archival records

- Ethnographic data

- Historical events

- Significant secondary literature

- Adjacent artistic and cultural production (music, literature, theatre, etc.)

Writers in our field seem credible when they:

- Address current and historical debates about the interpretation of a topic

- Demonstrate an awareness of the historical and cultural context of a topic

- Cite credible sources accurately. Credible sources include peer-reviewed journals, books, or websites from reputable institutions and organizations.

- For more information on citing sources accurately, see the “ Quick Guide to Citations for Art Historical Writing ”

This is how we write and do research in Art History

Art historical writing is about analyzing works of art to make a point or argument. Not every student in our classes needs to be able to write in the professional way of the field. However, depending on the reasons for taking our courses, we want students to become proficient and comfortable with analyzing art and the important place writing occupies in that process. Students taking an art history course should expect to write in the following genres:

- research papers

- exhibition reviews/evaluations

- book reviews

- visual analyses

- reading reflection/canvas posts

- museum labels

- essay exams

Writing goals and outcomes are different depending on the level of the course. For example:

- Undergraduates taking Miami Plan (100-level) or elective courses should recognize the relationship between how to develop a thesis and employ visual evidence in support of that thesis. Such a skill is undoubtedly useful for all students since looking closely coupled with the ability to make sense of what one sees are crucial for many other kinds of writing and ways of thinking. We argue the complexity and diversity of “looking deeply” is too often taken for granted in the visual world in which we live. In 100-level classes, students start to become familiar with how to write and think about art.

- Undergraduates majoring in our field should recognize that art historical writing is approached as a conversation or dialogue. As students progress through the major, being able to place a topic and research paper within previous published and ongoing debates is crucial. In other words, students should start to understand that writing in Art History is about creating a dialog between one’s ideas and the sources the student engages. We also want our students to understand the value of inserting their own voice when writing. Over time, majors will need to become skilled at synthesizing their ideas and arguments with original research. This very process is how objects tell us something distinctive about their historical context and their value within human history.

Resources for Art History Writers

The following resources were developed by Miami University Art History faculty with their undergraduate students in mind:

- Revision and the Writing Process

- Locating and Engaging Credible Sources

- Quick Guide to Citations for Art Historical Writing

- Annotated Sample Paper: Art 188: History of Western Art (Renaissance to Modern)

- Annotated Sample Paper: Read, Look, Reflect Essay on Michelangelo’s Sonnets & Awakening Slave

This guide was co-created by HCWE graduate assistant director Caitlin Martin and Art History faculty Dr. Annie Dell’Aria, Dr. Jordan Fenton, and Dr. Pepper Stetler.

The rise and rise of creative writing

Professor of Writing and Director - Centre for New Writing, University of Technology Sydney

Disclosure statement

John Dale does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Technology Sydney provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The phrase “creative writing” is believed to have been first used by Emerson when he referred to creative writing and creative reading in his address ‘The American Scholar’ in 1837.

The first classes in creative writing were offered at Harvard University in the 1880s and were wildly popular from the beginning with over 150 students enrolling in 1885.

Today Creative Writing as a discipline is booming in Australia and the extraordinary rise in student demand is most visible in postgraduate writing coursework award programs of which there are over 70 in Australian universities.

What defines Creative Writing as innovative is its emphasis on praxis. Students learn how a literature is made, how it is put together, and what its cultural context is and then they recombine this knowledge to produce their own creative works.

Creativity is the key. Einstein called it ‘combinatory play’, a matter of sifting through data, perceptions and materials to come up with combinations that are new and useful. This is what happens in a writing workshop and what distinguishes writing as a discipline from other areas of study that are more critical than creative.

Teaching writing is really a valiant effort by the writing teacher to put into words what he or she understands about creativity and about creating a work and trying to pass this on and to guide and inspire others.

To be a good writer a student must first of all be a good reader.There is a special vitality that comes from the creative writing workshop and the way in which writing as a discipline overlaps with, and exists in, the public sphere, in a way that many other academic disciplines do not. This external engagement impact is important and brings considerable prestige to the University.

In the past Creative Writing programs in Australia existed merely as an adjunct to literary studies or cultural studies, and struggled within the academy for proper recognition.

It was sometimes thought that Creative Writing lacked a theoretical underpinning although the workshop model, developed at the University of Iowa in the 1930s, has long ago reshaped, refined and incorporated theories of narrative, literature and creativity into a unified and successful pedagogical approach.

It has been a struggle for Creative Writing in Australian universities to gain the same degree of acceptance that it receives in colleges and universities across the US.

Despite opposition here it has gradually emerged as one of the leading disciplines in the Humanities and one that encourages students to think and create with integrity.

By 2010, Creative Writing had a higher national rating in the Australian Government’s Excellence in Research (ERA) report than either literary studies or cultural studies, and produced twice as many research outputs.

In recent years Non-Fiction has become a significant growth area for postgraduate coursework students, with the first Australian Masters of Non –Fiction introduced at UTS in 2011, and creative non-fiction and literary journalism classes overflowing at many of the 36 Australian university writing programs.

The interest in non-fiction has being driven in part by the desire for a greater number of professionals to communicate more lucidly with a broader range of people.

Genre writing, short fiction, novel writing, novella, memoir and life writing, poetry, writing for multimedia and scriptwriting, all continue to prove extremely attractive subject choices for a wide range of students, including a disproportionate number of lawyers and journalists who have returned to university to take up higher research degrees based around their creative practice.

In terms of coursework students, creative writing has always paid its way; now under ERA it might start to receive appropriate research funding.

We have been teaching writing in the academy for over a hundred and twenty five years, and Ian McEwan who first studied creative writing with Malcolm Bradbury at East Anglia in the 1970s, or Raymond Carver who was mentored at Chico University by the novelist John Gardner, or our own Tim Winton who was taught by Elizabeth Jolley at Curtin University, are all testament to the fact that not only can writing be taught at university, but also that writing actually flourishes in a university environment.

Writing is thinking. The great novels, poems, stories and films from our many graduates have helped shape our culture and allowed us to reflect on the way we live.

The future of Creative Writing in Australia is in good hands.

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Regional Engagement Officer - Shepparton

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Creative Writing and Art History

Grant, Catherine / Rubin, Patricia (Herausgeber)

Art History Special Issues

1. Auflage März 2012 208 Seiten, Softcover Wiley & Sons Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-4443-5039-5 John Wiley & Sons

Probekapitel

Kurzbeschreibung

This collection considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing, from the creative writing of art history to dialogues between styles of creative and art-historical writing. The topics covered include Paul Gauguin's collages of quotations, Sophie Calle's collaboration with Paul Auster, Henry James' portraiture, Bernard Berenson's fictional artist 'Amico di Sandro', Virginia Woolf's 'visual' writing, Pablo Picasso's solar mythology as re-written by Georges Bataille, and creative writing in the 'middle voice'

- Beschreibung

- Autoreninfo

Creative Writing and Art History considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing. Essays range from the analysis of historical examples of art historical writing that have a creative element to examinations of contemporary modes of creative writing about art. * Considers the ways in which the writing of art history intersects with creative writing * Covers a diverse subject matter, from late Neolithic stone circles to the writing of a sentence by Flaubert * The collection both contains essays that survey the topic as well as more specialist articles * Brings together specialist contributors from both sides of the Atlantic

C. Grant, Courtauld Institute of Art and Goldsmiths, University of London, UK; P. Rubin, Institute of Fine Arts, University of New York, USA

©2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH - Betreiber - www.wiley-vch.de - [email protected] - Datenschutz - Cookie Einstellungen Copyright © 2000-2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., or related companies. All rights reserved.

- Fees and Finance

- Order a Prospectus

- How To Apply

- Tuition Fees

- Student Contract

- Interviews and Auditions

- Scholarships & Bursaries

- From Adversity to University

- Information for Parents, Carers and Partners

- Funding Options

- A Career in Teaching

- PhD and MPhil Degrees

- International Pathways

- Study and Apply

- Your Country Representatives

- Country Specific Entry Requirements

- English Language Requirements

- Visa and Immigration

- Student Support

- Study Abroad and Exchange

- International Short Programme Unit

- Degree Apprenticeships

- Accommodation

- Living Here

- Social Life

- Academic Life

- Sport at Chichester

- Support, Health and Wellbeing

- Careers and Employability

- Be You Podcast

Quick links

- Centre for Cultural History

- Centre for Education, Innovation and Equity

- Centre for Future Technologies

- Centre for Health and Allied Sport and Exercise Science Research (CHASER)

- Centre for Sustainable Business

- Centre for Workforce Development

- Centre of Excellence for Childhood, Society and Inclusion

- Chichester Centre for Critical and Creative Writing

- Chichester Centre for Fairy Tales, Fantasy and Speculative Fiction

- Creative Industries Research Centre

- MOVER Centre

- People and Well-Being in the Everyday Research Centre (POWER)

- The Iris Murdoch Research Centre

English and Creative Writing

- Social Work and Social Policy

- Pre-PhD Preparation

- ChiPrints Repository

- Research Excellence Framework

- Research Governance

- Research Office

Additional links

- Access to Expertise

- Business Hothouse

- Reach our Students

- Become an Academic Partner

- Conference Services

- Landlords and Homestay Hosts

- Service Users and Carer Opportunities

- Degree Apprenticeship Information

- Outreach and Student Recruitment

- School Partnership Office

- How To Find Us

- Working For Us

- Course and Semester Dates

- Sustainability

- Mission and Vision

- Policies and Statements

BA (Hons) Creative Writing and History

Shape your creative voice and critical skills with a focus on history

- Smaller class sizes for better learning

in the UK for Creative Writing courses

Guardian University Guide 2023

for teaching quality in Creative Writing

Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide 2023

in the UK for learning opportunities

National Student Survey 2023

Join us at one of our Open Days!

Saturday 22 June | Saturday 12 October | Friday 1 November | Saturday 23 November

Saturday 22 June

Saturday 12 October

Friday 1 November

Saturday 23 November

Our next Open Day is in:

Teaching and assessment, guest speakers, work placements, study abroad, course costs, entry requirements, develop your skills as a writer and grow your ability to critically engage with historical debate.

Hear from staff and students about what life as an English and Creative Writing student at the University of Chichester.

Our BA (Hons) Creative Writing and History course grows your ability as a creative writer as you develop your knowledge of historical analysis, critical debate, and research skills.

Learn from our team of practising and published poets, short story writers, novelists, dramatists and screenwriters, as you develop and find the creative writing medium that fits your voice.

In addition, you will explore your passion for history with modules that cover the Medieval period through into the twenty first century: both in Britain and across the world.

You’ll work with experienced tutors and experts who use the latest research to underlie their teaching to ensure that you have access to emerging creative writing techniques and the latest debates within the study of history.

On this course you will:

- Study the craft of writing short fiction, poetry, novels, screenplays and creative non-fiction.

- Gain a critical insight into historical societies from a variety of contexts and time periods.

- Learn from our expert team of published writers and leading academics.

- Engage with contemporary issues in your writing such as climate change, race and sexuality.

- Build your degree around your interests.

- Meet and talk with agents and editors at our annual publishing panel.

Define your degree path by your creative and historical interests

In your first year, you will learn to tap into your own experience and engage with the wider world for creative material. You will also begin to examine key events and contexts from throughout The Crusades, The Tudors, and Britain in the First World War.

In your second year, you will explore poetry, short fiction, life writing, flash fiction, and writing for children. Your historical studies will explore witchcraft, colonial and decolonisation histories, and thoughts and theologies of Medieval societies.

The creative modules in your final year allow you to explore your discipline and genre of choice. You will also explore more specific genres such as YA fiction, flash fiction, digital writing, fantasy, and science fiction. You will explore the novel, short stories and poetry.

Alongside this, your historical studies will conclude with a focus on acts of separation, resistance and change. You will also explore Early Modern shopping and trade, historical attitudes to death, and the representation of history within graphic novels.

Select a year

Creative non-fiction: starting from the self, europe and the mediterranean world: society, identity and encounters: 1450-1700, introduction to writing short fiction, making history: theory and practice, renaissance and reformation europe: 1350-1600, source and exploration, the tudors: 1485-1603, the united states: an introduction: 1763-1970, the writer’s notebook, war and peace: twentieth-century europe and global conflict.

This module introduces you to the versatile genre of creative non-fiction, in which writers employ skills transported from fiction to lend dramatic complexity to factual narratives.

Using autobiographical material as a base, you will generate dramatic scenes on a variety of topics and themes.

This module will introduce you to conflicts and relations between southern Europe, the Maghreb and the Ottomans from 1450 to 1700.

You will explore the socio-political structure of Mediterranean Europe through the study of early modern urban history with a focus on communities and cultural encounters.

Subjects under discussion will include revolts, diplomatic affairs, trade, piracy, spying and human trafficking between Europe and other Mediterranean states.

This module will build on skills and techniques acquired throughout your first semester, such as:

- concrete imagery

- writerly research

- notebook gatherings

- reflections on developing creative work.

You will encounter a variety of forms and voices in a range of examples from traditional and contemporary sources in both British and international short fiction.

This module examines different approaches to a range of historical case studies. These will include, amongst others, social and cultural history, the history of women, gender and sexuality, ideology and discourse analysis, postcolonial, the history of the visual image, landscape and public history, the legacy of modern war, and heritage studies. Key concepts common to history writing such as periodisation and the nature of the archive are also examined.

This module evaluates the political, intellectual and religious development, popular, elite and court culture, warfare and international relations and gender issues across Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire within the Renaissance and Reformation periods.

In doing so, you will gain a better understanding of Early Modern European society and the way it responded to pressure and change.

The module will train your observation skills. You will learn to apply the world around you to inform your creative processes. You will also learn the value of the ‘concrete’ as opposed to the ‘abstract’ and discover how the ordinary can become extraordinary.

This module moves chronologically through the monarchs and events of the sixteenth century.

You will consider the role of political faction in the decision-making process under Henry VIII; the impact of the Reformation at the centre and in the localities; the shaping of monarchical authority by the royal minority of Edward VI; and the female monarchies of Mary and Elizabeth.

This module analyses the distinctive origins of American political thought and constitutional practice, the structures and effects of slavery, the origins of the civil war, the evolution of popular culture with special reference to jazz, the pursuit of civil rights and the emergence of the United States as a world power.

This module introduces you to keeping a writer’s notebook and how to use this as a storehouse of ideas, images, research and drafts. You will also learn about the journey from rough idea to finished piece as you examine a selection of case studies of notebook entries, drafts, and published work.

This module provides you with an overview of European political, cultural, and military history during the 20th century through the study of its major conflicts and global forces.

The central focus of the module is the international history of the major Great Powers between 1914 and 2000. You will examine of some of the common debates that often surround the origins of the First World War; the Second World War; the Cold War and debates on the ‘New World Order’.

A Social History of Early Modern England: 1550-1750

Creative writing: poetry, form and freedom, creative writing non-fiction: writing place, from ‘angry young men’ to cool britannia: a historical analysis of british cultural activity after 1945, kingdom of heaven: crusading and the holy land: 1095-1291, popes and politics, re-litigating the past: state, media and historical injustice in contemporary britain, renaissance to restoration, stuart england 1603-88: rebellion, restoration and revolution, women and gender: 1000-1600.

This module will explore the lives of ‘ordinary’ (i.e. non elite) men, women and children living in England from c1550 to c1750.

You will consider key defining factors of the society during this period including social structures; gender relations; lifecycles; urban and rural life; poverty and welfare; crime and punishment; popular culture; and the church.

This module will enable you to develop a variety of sophisticated traditional poetic forms and to develop experimental free verse poems within a reflective contemporary poetic practice.

You will examine and experiment as writers in three genres:

- travel writing

- ‘the new nature writing’

- psychogeography.

Over the course of the module, you will undertake three assignments, one in each genre. In so doing, you will develop a nuanced understanding of non-fiction as a literary form. These ‘assignments’ will also extend your professional skills of research, drafting and presentation.

This module provides you with an opportunity to analyse examples of British cultural activity after 1945 within their artistic, political, and historical contexts.

The module discusses a series of key movements of cultural production, for example, ‘the Angry Young Men’; ‘Cold War fictions’; or ‘Thatcherism/responses to Thatcherism’.

This module assesses the causes and consequences of crusading to the Holy Land between 1095-1291.

You will examine the motives of the First Crusaders and the subsequent defence of the Holy Land, including leaders such as Richard the Lionheart, as well as the political and economic ramifications for the Latin East and the indigenous populations of the invaded territories.

This module examines the nature of papal pronouncements and diplomatic interventions in the continuing evolution of the modern nation state. You will consider these ideas in the new ideological landscapes of totalitarian power, in the two world wars and the Cold War.

It will involve an analysis of the ideas, culture and structures of the Roman Catholic Church as they were found at work in the contexts of national and international politics in the years 1864-2005.

This module focuses on how public histories have been rewritten in Britain over the past three decades, through the interventions of state, media, and voluntary sector institutions.

By studying these forms of investigations, you will learn about how private traumas are integrated into or transformed public memory, the ways in which and reasons why silences are maintained or broken, and the place of ‘the past’ in judicial processes.

This module explores the evolution of poetry and prose throughout the Renaissance era and into the Restoration period of the 17th century, as result of major political and religious turbulence.

You will consider the works of Spencer, Marlowe and Shakespeare, who begin to explore gender and history in their work, before moving on to the satirical poetry of Donne, Marvell, Milton, and Rochester.

This module introduces you to the Stuart Age, circa 1603-88, as you explore why England went through such a period of extended turbulence and instability in the seventeenth century.

You will explore the radical political, religious, economic, social, cultural and intellectual changes that took place in Britain and beyond, in era of constitutional instability.

This module explores the term ‘gender’ and its usefulness as a category of historical analysis. It will then explore major areas of research on gender and sexuality by medieval and early modern historians, examining women across all social strata, from queens and regents to prophets and peasants.

Approaches to Research

Art & knowledge in europe: from early renaissance to baroque: 1250-1650, creative non-fiction: writing lives, culture and civilisation in late medieval england: c.1200-1550, enlightenment europe: 1688-1789, environment and state in britain since 1945, experiments in fiction: magic, detection, sci fi and beyond, fascism and post-fascism in europe, fairy tales: early modern to postmodern, fiction for children, heritage in practice: work placements for history students, prose fiction: the dynamic of change, romantics, rebels and reactionaries.

This module will build on your earlier explorations of research techniques, with a focus on the development of time and project management skills as you begin to prepare for your dissertation. Questions concerning how one starts on a research project and establishes viability of subject to a range of different approaches/theoretical perspectives will be discussed in detail, in relation to how you will choose their own dissertation topic.

This module examines the development of art, knowledge, taste, fashion and beliefs in Europe from c.1250-1650 as you consider the importance of intellectual history, cultural history, science and art as key aspects of European culture. You will pay close attention to a range of textual and visual sources — from literature, diaries, correspondence, journals, painting, sculpture and architecture.

This module offers a thematic and contextual survey of late-medieval England.

It commences by problematising ‘The Middle Ages’, focusing on historiography, myth, public perception, and the constructed nature of historical periodisation.

The focus is on England, but material from elsewhere may be used, and videos and field trips are normally employed in order to enhance your understanding of late-medieval culture and its conceptualisation.

The ideas of the Enlightenment provided new ways of thinking about science, religion, education, politics and society and the place of ‘mankind’ in the world, but to what extent did the ‘philosophers’ transform society and how enlightened were they?

You will explore these ideas as you engage with the works of Locke, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Diderot, Rousseau, Beccaria and Wollstonecraft.

This module explores the British state’s evolving stewardship over the environment since the end of the Second World War.

You will examine the connected environmental challenges that the state has faced in this time including pollution, urban change, resource depletion, species conservation and control, epidemics, extreme weather, the threat of nuclear war, and climate change.

This module aims to provide you with an understanding of, and ability to recognise, a range of genres in prose fiction.

You will gain an understanding of genre as a means of classification and understand that the way a text employs genre shapes its meaning.

By looking at a variety of case studies from across Europe throughout the first half of the 20th century, we will discuss the way in which fascism was both embraced and fought against.

In addition, by using literary and cultural forms of post-fascism you will explore how many of the core messages of ideological fascism survived despite being politically discredited.

Gain an informed historical and critical perspective on a powerful literary and cultural tradition beginning with the fairy tales written in early modern Italy, continuing through Perrault, D’Aulnoy, Grimm, Andersen to the work of more contemporary authors such as Angela Carter and Margaret Atwood. It also asks where we can turn to for modern fairy tales, through a focus on the use of fairy tale tropes in the work of J.K Rowling and Philip Pullman.

This module introduces you to writing fiction for children.

The module will extend and deepen your key writing skills as you learn to pay particular attention to such things as suitable and age-specific subject matter, appropriate language, a more active narration, faster pacing and the demands of greater immediacy.

The aim of the module is to introduce you to the ways in which your learning experiences in the discipline of History can be applied to the working environment.

The work placement experience will provide you with an understanding of the practical, ethical and technical issues involved in the collection, cataloguing and preservation or conservation of physical traces of the past.

This module will explore the dynamics of change in the contemporary short story.

You will examine model short stories and how they invariably dramatise a significant change in character, and/or situation.

In doing so, you will understand how to analyse the devices writers use to shape narrative, and to create tension and conflict.

The module will also assess how far second-generation Romantic poets developed the key Romantic theme of reform, as you consider the influence of the French Revolution on the work of British writers during the 18th century.

You will study the work of renowned and revered Romantic poets including Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Wollstonecraft, alongside the work of Mary Shelley and Jane Austen.

British Culture Wars

Digital writing: writing for the community of strangers, france and the modern world, henry viii and court culture 1509-1547: faction, faith and fornication, international law, gothic, romanticism and women’s writing: from mary wollstonecraft to jane austen, kingship, queenship and power in late medieval and early modern europe, louis xvi’s france: 1643-1715, making it strange: writing the science fiction, fantasy and modern gothic novel, the cultural history of death, unconscious desires: psychoanalysis and culture from freud to žižek, unforgettable corpses: literature, cultural memory and the first world war, writing the novel.

This module explores conflict within British culture from the start of the 19th century to the turn of the new millennium.

You will consider the reaction to obscene publications and other literary controversies and moral panics of Victorian Britain, through to the liberal reforms in the 1960s and the self-censorship and the baleful influence of Hollywood on British cinema.

On this module, you will harness the skills developed in non-fiction modules in year one and year two to engage with new possibilities in digital writing, including:

- online journalism

- Twitter/Tumblr/Facebook

- comments forums

and the non-linear; e-books; apps; fan fiction; reviews, etc.

This module introduces you to the key themes and trends in Modern French History. You will study the post-war development of a major European nation, looking at the ways in which it sought to reassert its strengths in international politics. You will also examine how this impacted on its people, analysing aspects of French society and culture to track major changes in national identity.

This module examines the structures and cultures of royal courts of the Tudor period. In particular, you will consider court culture through the eyes of contemporaries in order to explore the centrality of the royal court and its relationship to the localities during this period of such immense change. You will explore the royal court’s political influence, the role of faction and division and the relationship to the literary arts.

This module introduces you to international law: the body of law which governs the legal relations between or among states and nations.

You will study the theories, principles and processes of international law, including its sources, legal personality, jurisdiction and realms of responsibility.

In addition, you will also be introduced to debates about the regulation of international activities, including the use of force, dispute settlement processes, human rights, and the role of the UN.

The aim of this module is to introduce you to the exciting range of women’s prose writing in the late 18th century, as you consider the relationship between such writing and the political debates of the period.

You will discover how this writing, while often underrated, was of importance to Romantic aesthetics, often primarily understood and defined in terms of poetry written by men.

This module considers the nature of social, cultural and political power in the late medieval and early modern periods by examining a variety of different topics such as royal ritual and law-making, visual and material culture, and social exclusion and popular rebellion.

You will understand how power was conceptualised and exercised in different socio-cultural contexts and chronological periods, as well as consider the role of gendered within power structures and social responses to rulers.

This module assesses the extent to which an ‘absolutist’ monarchy was established in France in the seventeenth century. You will consider various historiographical perspectives of the French monarchy, with a focus on the social and cultural contexts of the period as well as the impact of the military tensions with other European nations.

This module offers you the opportunity to develop your creative skills within genres that focus on worlds that lie beyond the tradition realm of ‘realism’. These forms of ‘Beyond Realist’ texts have a distinguished pedigree stretching back to humanity’s earliest myths, epic narratives, folklore and fairy tales. You will explore how to write within genres such as science fiction, fantasy and contemporary Gothic as you learn their specific complexities and intricacies.

This module explores how literary representations of the historical and social treatment of the dead presents a vivid insight into the cultural behaviour, ideology and social order of different cultural and historical contexts. You will explore the beliefs and attitudes towards the dead within literature from the Middles Ages through to more contemporary examples and debates.

This module explores the notion of unconscious desire and the expression of these desires in literature and culture.

You will trace the emergence of the ideas of psychoanalysis in the work of Freud and how various psychoanalytic thinkers have transformed the notion of unconscious desire and used it to grasp literary and cultural forms.

This module will examine literary products of the First World War, the methods by which the authors reproduced, described and fictionalised their experiences.

The second half of the module will also consider the use of First World War tropes in literature produced in the latter half of the 20th century, compare the application of those narrative devices, and critically assess the later use of those devices.

On this module, you will write the first chapter of a contemporary novel, deepening skills gained on short fiction modules in Years 1 and 2. Having acquired skills in narrative, imagery, characterisation, and theme, you will now be encouraged to develop these skills in greater depth while engaging with the demands and challenges of a longer form.

A Global History of the Cold War

Birds, beasts and bestiaries: animals and animal symbolism in late medieval and renaissance europe: c.1100-1650, commerce and consumption in early modern england: c. 1600-1750, contemporary short fiction: writing the here and now, dictatorship, conformity and resistance in hater’s germany, mussolini’s italy and stalin’s russia, globalisation and its malcontents, vice to virtue the origins and outcomes of the french revolution: 1744-94, writing, environment and ecocriticism, writing flash fiction.

This module introduces you to a wider view of the effects of the Cold War beyond the traditional Western-centric view. You will examine the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union in the Middle East, the decolonisation processes in Asia and Africa, the political influence on developing nations in Latin America, and the emergence of China as an additional player.

This module explores the various roles of animals within Late Medieval and Renaissance Europe, both in reality and within cultural arts. You will examine: the role of animals as diplomatic gifts; domestication and pet keeping; animals and warfare; exotic animals and mythological beasts; hunting and lordship; animals and Christianity; chivalric animals (in heraldry and romances), and animals and national identity.

This module examines the emerging commercial cultures of Early Modern England. Using primary sources of wills, business accounts, personal letters, and diaries, you will consider the changing attitudes to business and consumption of the period and how they laid the groundwork for further economic evolutions that influence the way we live today.

This module will enable you to explore, as active writers and readers, the strategies, innovations and preoccupations of contemporary writers of the short story. You will read and analyse the craft, technique and rigour of three to four highly regarded short story collections from the last fifteen years.

This module explores the distinctive ideologies of Soviet Communism, Italian Fascism and German National Socialism, and to consider if and how these were in fact new forms of religion. The module will also examine the construction of these ‘totalitarian’ states in practice, and the experiences of individual and institutions caught up within these contexts, with particular reference to the churches and to cultural movements.

This module looks at key moments in the development of globalization focusing on moments in which the world came together, such as the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, when the terms of global trade were outlined after the rupture of the Second World War. You will use these examples to contextualise the work of theorists like Arjun Appadurai to develop your understanding of how globalization has shaped twentieth-century history and politics.

This module examines the roots and consequences of the French Revolution, as well the major historiographical debates that continue through to today. You will gain a clear understanding of the political, social and economic context of the revolution’s origins, the complexities and evolution of the Revolution itself, and the fallout and ramifications across the subsequent decades.

This module will offer you the opportunity to explore the ways in which contemporary writers and critics engage with images, issues and concepts of the environment in novels, poetry and non-fiction. You will choose whether you wish to engage with the themes of the module as a critic or a creative writer.

‘Flash Fiction’ is an exciting new way of telling stories. By composing their own portfolio of very short fiction, you will be challenged to see the form from the inside, and to focus upon the creative challenges that are unique to ‘flash fiction’. These challenges will be brought into additional focus by workshops that require critical reflection upon the evolving work.

Dissertation in Creative Writing

Dissertation in history.

The Dissertation in Creative Writing gives students the opportunity to work independently on an imaginative writing project of their own choosing.

This may take the form of a fiction project, a poetry project, a play or screenwriting project, or a creative non-fiction project.

It will include a related essay in which the student-writer investigates a particular artistic, aesthetic or cultural issue of relevance to you as a contemporary writer OR the work of a particular writer who will be influential as you develop your own body of work for the Dissertation project.

The dissertation represents the culmination of your History studies as you complete an individual research project on a topic of your choosing.

The 10,500-word thesis will include explicit methodological and historiographical dimensions and where appropriate, theoretical discussions integrated into the text.

Find facilities and research centres that support your learning

Bishop otter campus.

Click to watch our virtual tour of our historic Bishop Otter campus in the heart of Chichester.

Close community

Our commitment to a friendly and close-knit student community contributes to a high degree of success for our graduates.

Learning Resource Centre

The Learning Resource Centre (LRC) contains the library, a café, IT/teaching rooms, and the Support and Information Zone (SIZ).

Our campus library holds more than 200,000 books and over 500,000 eBooks.

Expert staff

You will learn from practicing and published writers alongside expert academic tutors from the field of History.

Subject specific librarians

If you have difficulty finding material for an essay, seminar or project, subject librarians will be happy to provide assistance.

South Coast Creative Writing Hub

The University is home to this community of staff, graduates, and current students who host events with local authors.

Chichester Centre for Fairy Tales, Fantasy, and Speculative Fiction

Our forum for research and debate into beyond realist literature.

Guest speakers

The University regularly welcomes renowned creative writers to speak on their work and industry.

Iris Murdoch Research Centre

The Iris Murdoch Research Centre supports and develops work into this major twentieth century writer.

Royal Literary Fellows

Gain writing support from professional writers through the Royal Literary Fund.

Local cultural links

The University is placed within the reach of the beautiful South Downs area of the UK.

Learn from published writers and experts from the field of History

Much of our teaching takes place in small groups. Within these classes, you will typically discuss good writing practice and workshop your own writing.

Our commitment to smaller class sizes allows you to feel more confident to discuss your ideas in a supportive environment. It also allows your tutors get to know you and how best to aid your development.

Creative writing modules are predominately assessed through portfolios of work. Your History modules will mainly be assessed through a combination essays, exams and presentations.

Modules are assessed at every stage of the course, allowing you to clearly see your academic progress at all stages of the course.

Gain unique insight into the creative writing industry

The University boasts a blossoming writing culture and community, with regular book launches and conferences.

We also run special events with renowned creative writers. As a Creative Writing and History student, you can use these as opportunities to learn more from those with critical insight into the industry.

Some renowned authors to have visited the University in recent years include:

- Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy

- Matthew Sweeney

- Helen Dunmore

- Jo Shapcott

- Bernardine Evaristo

- Vicki Feaver

- Alison MacLeod

- John McCullough.

Gain vital experience within the workplace

The Work Placement module allows you to develop your skills in a work environment and gain vital experience to put you ahead in your future career.

This allows you to gain experience in, for example, a workplace such as a local newspaper or as a writer-in-residence. You will then use the skills you have learnt on your course in order to reflect critically on the world of work.

Alternatively, you could pursue opportunities linked to your history modules and will have the option to work with sector-leading museums, galleries or heritage sites.

Our prestigious partners include Arundel Castle, Emsworth Museum, the West Sussex Record Office, and the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum – the setting for the BBC One show The Repair Show.

Our prestigious local partners include:

- Arundel Castle

- Bignor Roman Villa

- Butser Ancient Farm

- Chichester Cathedral

- Chichester District Museum

- D-Day Museum, Southsea

- Emsworth Museum

- Fishbourne Roman Palace

- Mary Rose Museum

- Pallant House Gallery

- Petworth House

- Portsmouth City Museum

- Royal Marines Museum

- Tangmere Aviation Museum

- University of Chichester Archive Collections

- Weald and Downland Open Air Museum

- West Sussex Record Office

- Worthing Library

Explore the opportunity to study part of your course abroad

As a student at the University of Chichester, you can explore opportunities to study abroad during your studies as you enrich and broaden your educational experiences.

Students who have undertaken this in the past have found it to be an amazing experience to broaden their horizons, a great opportunity to meet new people, undertake further travelling and to immerse themselves within a new culture.

You will be fully supported throughout the process to help find the right destination institution for you and your course. We can take you through everything that you will need to consider, from visas to financial support, to help ensure that you can get the best out of your time studying abroad.

Open up your future career options

Our Creative Writing and History graduates are highly-valued by employers for their strong problem solving and communication skills and often continue into a variety of careers.

Career paths include:

- Copywriting

Creative writing success

The last few years have shown a fabulous flowering of our Creative Writing students’ work. Many students at both undergraduate and postgraduate level have continued on to become published writers.

Many of our students publish and win prizes. In recent years students have gone on to publish novels, poetry collections, win prizes in major competitions such as the Bridport Prize and have poems and stories in magazines such as The Paris Review and Staple .

Former Chichester Creative Writing student Bethan Roberts has recently had her novel My Policeman adapted for the silver screen in a film staring Harry Styles and Emma Corrin, whilst others have also had work broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Postgraduate pathways

- MA Creative Writing

- MA Cultural History

- MA English Literature

- MRes The History of Africa and the African Diaspora

- Postgraduate Research (MPhil/PhD)

Course Fees 2024/25

International fee.

For further details about fees, please see our Tuition Fees page.

For further details about international scholarships, please see our Scholarships page.

To find out about any additional costs on this course, please see our Additional Costs page .

Typical Offer (individual offers may vary)

Access to he diploma, frequently asked questions, how do i apply.

Click the ‘Apply now’ button to go to relevant UCAS page.

What are UCAS tariff points?

Many qualifications have a UCAS Tariff value. The score depends on the qualification, and the grade you achieved.

How do I know what my UCAS tariff points are?

Head to the UCAS Tariff Points web page where you can find a tariff points calculator that can tell you how much your qualification and grades are worth.

Related courses

Ba (hons) creative writing and philosophy & ethics, ba (hons) creative writing, our address.

University of Chichester, College Lane, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 6PE View Map

(+44) 01243 816000 [email protected]

(+44) 01243 816000

Campus tours [email protected]

Open Days & Applicant Days [email protected]

A Brief History of Creative Writing

by Matt Herron | 20 comments

Free Book Planning Course! Sign up for our 3-part book planning course and make your book writing easy . It expires soon, though, so don’t wait. Sign up here before the deadline!

There are hundreds of new programs, websites, and apps to help with your creative writing, but it might help you put them into perspective by examining the history out of which these technologies have emerged.

Like all technology, new tools are built on the foundation of the ones that came before them. Let's take a quick journey through the history of creative writing tools so that we can evaluate modern creative writing tools in a historical context.

Oral Storytelling

Originally, stories were passed from generation to generation through oral storytelling traditions .

In these traditions, the primary “writing” tool was the storyteller’s memory and voice , though stories were often augmented by instruments and dance. Stories were imbued with the personality of the teller, and took on color in the creative exchange with the audience.

Stories evolved over time through the retelling. They improved, were embellished, or were transformed into myth and legend.

The Written Word

It wasn't until (relatively) recently, with the invention of the written word ( archaeologists place its formation around 3200 BC , depending on location) that we started writing stories down.

This is where the history of creative writing really begins.

Some of the earliest examples of written stories in the Western tradition are the Bible and Homer's Odyssey; in the Eastern Tradition, the Indian Vedas and Sanskrit poems; in central America, the Mayan Codices.

It’s likely that many of these early texts were simply being transcribed from the oral tradition. The legend that Homer was blind—whether it’s true or not—gives us a symbolic link connecting the oral and written storytelling traditions.

In any case, storytellers started writing their stories down. Once that happened, the process of creative writing evolved.

Instead of telling and retelling stories orally and making them better over time, written language gave storytellers the ability to tell themselves the story over and over again using a drafting process. It gave them a way to record more stories by providing them a physical extension of their memory: ink and paper .