About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Research Support

- Stanford GSB Archive

Explore case studies from Stanford GSB and from other institutions.

Stanford GSB Case Studies

Other case studies.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Leadership →

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

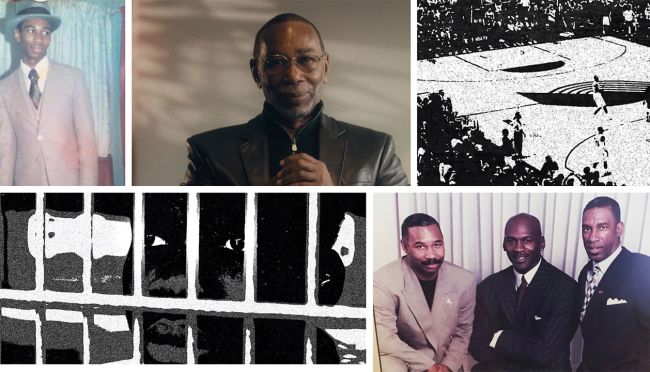

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 02 Jan 2024

- What Do You Think?

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

10 Trends to Watch in 2024

Employees may seek new approaches to balance, even as leaders consider whether to bring more teams back to offices or make hybrid work even more flexible. These are just a few trends that Harvard Business School faculty members will be following during a year when staffing, climate, and inclusion will likely remain top of mind.

- 12 Dec 2023

Can Sustainability Drive Innovation at Ferrari?

When Ferrari, the Italian luxury sports car manufacturer, committed to achieving carbon neutrality and to electrifying a large part of its car fleet, investors and employees applauded the new strategy. But among the company’s suppliers, the reaction was mixed. Many were nervous about how this shift would affect their bottom lines. Professor Raffaella Sadun and Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna discuss how Ferrari collaborated with suppliers to work toward achieving the company’s goal. They also explore how sustainability can be a catalyst for innovation in the case, “Ferrari: Shifting to Carbon Neutrality.” This episode was recorded live December 4, 2023 in front of a remote studio audience in the Live Online Classroom at Harvard Business School.

- 05 Dec 2023

Lessons in Decision-Making: Confident People Aren't Always Correct (Except When They Are)

A study of 70,000 decisions by Thomas Graeber and Benjamin Enke finds that self-assurance doesn't necessarily reflect skill. Shrewd decision-making often comes down to how well a person understands the limits of their knowledge. How can managers identify and elevate their best decision-makers?

- 21 Nov 2023

The Beauty Industry: Products for a Healthy Glow or a Compact for Harm?

Many cosmetics and skincare companies present an image of social consciousness and transformative potential, while profiting from insecurity and excluding broad swaths of people. Geoffrey Jones examines the unsightly reality of the beauty industry.

- 14 Nov 2023

Do We Underestimate the Importance of Generosity in Leadership?

Management experts applaud leaders who are, among other things, determined, humble, and frugal, but rarely consider whether they are generous. However, executives who share their time, talent, and ideas often give rise to legendary organizations. Does generosity merit further consideration? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Oct 2023

From P.T. Barnum to Mary Kay: Lessons From 5 Leaders Who Changed the World

What do Steve Jobs and Sarah Breedlove have in common? Through a series of case studies, Robert Simons explores the unique qualities of visionary leaders and what today's managers can learn from their journeys.

- 06 Oct 2023

Yes, You Can Radically Change Your Organization in One Week

Skip the committees and the multi-year roadmap. With the right conditions, leaders can confront even complex organizational problems in one week. Frances Frei and Anne Morriss explain how in their book Move Fast and Fix Things.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 01 Aug 2023

As Leaders, Why Do We Continue to Reward A, While Hoping for B?

Companies often encourage the bad behavior that executives publicly rebuke—usually in pursuit of short-term performance. What keeps leaders from truly aligning incentives and goals? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jul 2023

What Kind of Leader Are You? How Three Action Orientations Can Help You Meet the Moment

Executives who confront new challenges with old formulas often fail. The best leaders tailor their approach, recalibrating their "action orientation" to address the problem at hand, says Ryan Raffaelli. He details three action orientations and how leaders can harness them.

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Jun 2023

Every Company Should Have These Leaders—or Develop Them if They Don't

Companies need T-shaped leaders, those who can share knowledge across the organization while focusing on their business units, but they should be a mix of visionaries and tacticians. Hise Gibson breaks down the nuances of each leader and how companies can cultivate this talent among their ranks.

Four Steps to Building the Psychological Safety That High-Performing Teams Need

Struggling to spark strategic risk-taking and creative thinking? In the post-pandemic workplace, teams need psychological safety more than ever, and a new analysis by Amy Edmondson highlights the best ways to nurture it.

- 31 May 2023

From Prison Cell to Nike’s C-Suite: The Journey of Larry Miller

VIDEO: Before leading one of the world’s largest brands, Nike executive Larry Miller served time in prison for murder. In this interview, Miller shares how education helped him escape a life of crime and why employers should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance. Inspired by a Harvard Business School case study.

- 23 May 2023

The Entrepreneurial Journey of China’s First Private Mental Health Hospital

The city of Wenzhou in southeastern China is home to the country’s largest privately owned mental health hospital group, the Wenzhou Kangning Hospital Co, Ltd. It’s an example of the extraordinary entrepreneurship happening in China’s healthcare space. But after its successful initial public offering (IPO), how will the hospital grow in the future? Harvard Professor of China Studies William C. Kirby highlights the challenges of China’s mental health sector and the means company founder Guan Weili employed to address them in his case, Wenzhou Kangning Hospital: Changing Mental Healthcare in China.

- 09 May 2023

Can Robin Williams’ Son Help Other Families Heal Addiction and Depression?

Zak Pym Williams, son of comedian and actor Robin Williams, had seen how mental health challenges, such as addiction and depression, had affected past generations of his family. Williams was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a young adult and he wanted to break the cycle for his children. Although his children were still quite young, he began considering proactive strategies that could help his family’s mental health, and he wanted to share that knowledge with other families. But how can Williams help people actually take advantage of those mental health strategies and services? Professor Lauren Cohen discusses his case, “Weapons of Self Destruction: Zak Pym Williams and the Cultivation of Mental Wellness.”

- 11 Apr 2023

The First 90 Hours: What New CEOs Should—and Shouldn't—Do to Set the Right Tone

New leaders no longer have the luxury of a 90-day listening tour to get to know an organization, says John Quelch. He offers seven steps to prepare CEOs for a successful start, and three missteps to avoid.

Strategic Leadership for Business Value Creation

Principles and Case Studies

- © 2021

- Don Argus 0 ,

- Danny Samson 1

Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Australia Advisory Board, Melbourne, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne, Carlton, Australia

- Provides insights and wisdom on leadership and strategy that create value when they are executed effectively

- Is targeted at business executives who want to develop and mature towards being successful value creators

- Develops and illustrates core concepts, and relates them to the two major case studies of NAB and BHP

25k Accesses

3 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (19 chapters)

Front matter.

- Don Argus, Danny Samson

Organisational (Business) Strategy

Organisational governance, corporate social responsibility, leaders of the future, nab (a): banking and financial services , 1960–2020, nab (b): nab’s acquisition strategy, nab (c): banking in australia , nab’s track record and trajectory, bhp (a): ‘the big australian’ overview and strategic roots, bhp (b): steel, bhp (c): minerals, bhp (d): petroleum, bhp(e): rejuvenation and renovation towards a new century, bhp(f): mergers and acquisitions, bhp(g): global strategy and the foreign investment review board (firb), bhp(h): industrial relations, bhp(i): environment.

- Business strategy

- Leadership factors

- Strategic leadership for value creation

- Corporate governance success for value creation

- Sustainable development strategies for value creation

- Operational Excellence development

- Strategy implementation through operations

- Executive development leadership factors

- BHP Case study

- NAB Case study

- National Australia Bank

About this book

Authors and affiliations.

Danny Samson

About the authors

Bibliographic information.

Book Title : Strategic Leadership for Business Value Creation

Book Subtitle : Principles and Case Studies

Authors : Don Argus, Danny Samson

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9430-4

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Singapore

eBook Packages : Business and Management , Business and Management (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2021

Softcover ISBN : 978-981-15-9429-8 Published: 14 January 2021

eBook ISBN : 978-981-15-9430-4 Published: 13 January 2021

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXV, 495

Number of Illustrations : 24 b/w illustrations

Topics : Business Strategy/Leadership , Corporate Governance , Management , Business and Management, general

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Back to All Programs /

Strategic Leadership

Enhance your ability to creatively problem-solve for the demands of working in ‘the new normal'.

All Start Dates

8:30 AM – 4:30 PM ET

3 consecutive days

Registration Deadline

August 18, 2024

December 1, 2024

What You'll Learn

Senior leaders face an unprecedented number of challenges in today’s rapidly-changing business environment, from an evolving workforce to complex strategic issues. To succeed in this dynamic business environment, strategic leadership involves asking better questions, leveraging a diverse workforce, and addressing the complex problems our organizations face in new ways.

During this interactive 3-day program, you will build upon your proven leadership skills with new insights, frameworks and tools to inspire yourself and better lead your team and organization. Reflective exercises, a leadership assessment instrument (Hogan), application activities, and case studies will help you work through modern-day dilemmas and solve problems using both critical and creative thinking. Small and large group discussions will focus on addressing the paradoxes of effective leadership at the executive level.

Program Benefits

- Examine what in organizational leadership is evolving — and what is remaining the same — and develop insight into how to address new and emerging senior leadership challenges

- Understand the multipliers and diminishers of effective leadership, and how to evolve as senior leaders

- Build and sustain greater levels of motivation and trust through more strategic leadership

- Earn a Certificate of Participation from the Harvard Division of Continuing Education

Topics Covered

- Leadership in today’s business world: what’s similar, what’s different, and why the stakes are higher

- Inspiring and motivating a diverse talent team

- Solving complex problems using both critical and creative thinking

- Managing modern-day dilemmas

- Addressing the tradeoffs, tensions, and dilemmas we face as senior leaders

- Future-proofing our organizations and ourselves

Who Should Enroll

This program is intended for senior managers with at least 10 years of management experience and proven leadership skills who want to enhance their capabilities to lead at higher levels in the organization.

Considering this program?

Send yourself the details.

Related Programs

- Emotional Intelligence in Leadership Training Program

- Agile Leadership: Transforming Mindsets and Capabilities in Your Organization

- Executive Leadership Coaching: Mastery Session

August Schedule

- The New World of Work and Leading In the ‘New Normal’

- Strategic Self-Leadership – Part I

- Strategic Self-Leadership – Part II

- Strategic People and Organizational Leadership

- Strategic Problem-Solving

- Strategic Leadership for the Future – Ourselves, Others, Organizations

December Schedule

Margaret andrews, certificates of leadership excellence.

The Certificates of Leadership Excellence (CLE) are designed for leaders with the desire to enhance their business acumen, challenge current thinking, and expand their leadership skills.

This program is one of several CLE qualifying programs. Register today and get started earning your certificate.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Drivers and consequences of strategic leader indecision: an exploratory study in a complex case

Leadership & Organization Development Journal

ISSN : 0143-7739

Article publication date: 8 June 2023

Issue publication date: 29 June 2023

The research explores indecision of strategic leaders in a complex case organization. This research offers new insights into the drivers of indecision of upper echelons decision-makers and explores the perceived consequences of the decision-makers' indecision.

Design/methodology/approach

Following a review of literature on upper echelons theory and strategic decision-making, indecision and the antecedents and consequences of indecision, the research follows a qualitative exploratory design. Semi-structured interviews were conducted among 20 upper echelons decision-makers with responsibility across 19 Sub-Saharan African countries in a case company. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data.

The findings reveal that specific organizational, interpersonal and personal factors work together to drive strategic leader indecision in a complex organization. Strategic leader indecision brings about several negative organizational consequences and demotivates team members.

Research limitations/implications

The findings are based on a single-case exploratory design but represent geographical diversity.

Practical implications

The research cautions organizations to deal with the drivers of strategic leader indecision to help avoid potential negative consequences of stifled organizational performance and team demotivation.

Originality/value

The study offers previously unknown insights into strategic leader indecision. This study builds on current literature on the antecedents and consequences of indecision and has a new research setting of strategic leader indecision in a complex organization.

- Strategic leader indecision

- Upper echelons

- Strategic decision-making

Motloung, M. and Lew, C. (2023), "Drivers and consequences of strategic leader indecision: an exploratory study in a complex case", Leadership & Organization Development Journal , Vol. 44 No. 4, pp. 453-473. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2021-0457

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Musa Motloung and Charlene Lew

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Decision-making is a central component of the leadership function ( Kokkoris et al. , 2019 ; Samimi et al. , 2019 ) and determines whether organizations succeed in competitive environments ( Gottfredson and Reina, 2020 ). Strategic leaders influence organizational outcomes through their decisions ( Hambrick and Mason, 1984 ). They need to make long-term, intuitive and holistic decisions ( Matsuo, 2019 ) that enable organizational success ( Gottfredson and Reina, 2020 ). Consequently, indecision puts the organization's sustainability at risk. Indecision refers to the tendency to unduly delay or delegate decisions ( Elaydi, 2006 ).

Even though there is a large body of knowledge on leadership decision-making, research into indecision of strategic leaders remains sparse ( Brooks, 2011 ; Samimi et al. , 2019 ). Most literature on indecision deals with career indecision (e.g., Lent et al. , 2019 ), or personal traits and indecision (e.g., Ferrari et al. , 2018 ), but very few studies focus on the indecision of leaders and especially upper echelon leaders. A better understanding of the drivers of indecision can shed light on existing models of strategic decision-making ( Kokkoris et al. , 2019 ; Aboramadan, 2021 ). The context of strategic decision-making differs from managerial decision-making. At the core, strategic decisions are ad hoc, non-routine, complex and consequential for both individual leaders and the organization ( Kauppila et al. , 2018 ). The fast-paced and uncertain nature of the business environment can therefore exacerbate indecision ( Wowak et al. , 2016 ). Moreover, strategic leaders compete for scarce resources during decision-making ( Pettigrew, 1973 ). It is for this reason that strategic decisions, such as decisions to implement large-scale innovations, mergers and acquisitions, corporate restructuring, or new market entries, bring about political behavior in the top team ( Friedman et al. , 2016 ). The high-stakes, complex and political context of strategic decision-making suggests the need for a study focused on the indecision of strategic leaders.

Scholarly research shows that personal variables, such as fear of commitment, self-consciousness, perfectionism and negative self-conceptions, generally lead to indecision ( Elaydi, 2006 ). More recent literature offers clues on the causes of indecision in management. It shows that job anxiety ( Wowak et al. , 2016 ), fear of the potential organizational impact of poor decision-making ( Samimi et al. , 2019 ) and avoidance of accountability ( Shortland et al. , 2023 ) can lead to risk aversion and indecision among senior managers. This indicates that there may be further personal drivers of strategic leader indecision that need to be explored.

Studies also show that strategic decision-making is influenced by several social variables, such as the strength of the coalition of the team members, or how actively the chief executive officer (CEO) engages with the top team ( Liu et al. , 2022 ). This study therefore broadens the investigation to understand not only personal, but also interpersonal and organizational factors that may bring about the indecision of strategic leaders.

Moreover, given the significant impact of strategic decisions on organizational outcomes ( Gottfredson and Reina, 2020 ), there is a need to understand the consequences of strategic leader indecision. Studies show that the political behavior of the top team members can influence firm performance ( Shepherd et al. , 2020 ), including financial and non-financial outcomes of organizations ( Samimi et al. , 2019 ). Shortland et al. (2023) therefore stress the current need to examine the organizational and environmental outcomes of the indecision of leaders.

Therefore, this study explores the drivers and consequences of the indecision of strategic leaders in a complex organization. It contributes to an understanding of decision-making of strategic leadership within upper echelons theory ( Bromiley and Rau, 2016 ). The research offers insights on the psychological, social and organizational antecedents and implications of indecision to offer practical guidelines on how to strengthen strategic leader decision-making. A better understanding of indecision in the top management team can lead to more effective leaders, senior teams and organizations.

Literature review

Upper echelons theory and strategic leadership.

In order to evaluate the role of indecision in top management teams, we examine the literature on the significance of the top management team, their role in strategic decision-making and the importance of the collective strategic leadership team. We know from upper echelons theory that the background of senior leaders, such as their life experiences, values and personalities influence how they interpret and respond to situations for which they need to make decisions. Social, behavioral and cognitive functioning of upper echelon leaders therefore influence their decisions ( Bromiley and Rau, 2016 ), Moreover, from observing the characteristics of strategic leaders, such as their backgrounds, educational levels, ages and years of experience, one may predict how they will make decisions ( Aboramadan, 2021 ). Subsequently, their choices impact organizational performance ( Hambrick and Mason, 1984 ; Friedman et al. , 2016 ; Aboramadan, 2021 ).

Strategic leadership refers to the activities, including decision-making, of upper echelon leaders ( Hambrick and Mason, 1984 ). As part of their functional roles, which involve setting and communicating the vision, developing core competencies, attracting and retaining human capital, committing resources to new technologies and engaging in valuable strategies linked to global opportunities, upper echelon leaders are accountable for strategic decision-making ( Hitt et al. , 2010 ). Their functional roles also require that they manage conflicting demands and engage with external stakeholders while making strategic decisions ( Samimi et al. , 2019 ). They are responsible for creating an enabling organizational culture to succeed in a competitive environment ( Gottfredson and Reina, 2020 ). Therefore, strategic decision-making is a central task of upper echelon leaders to shape the future, results, relationships and culture of the organization. Their decisions have greater scope, influence and long-term impact than the rest of the organization ( Goldman and Casey, 2010 ).

Strategic decisions are not made by individual managers, but by the collective strategic leadership team. Strategic leaders that are part of a team that has educational, functional and tenure-related diversity enable the continued growth of the organization over more than one period ( Chen et al. , 2019 ). Cultural, age-related and gender-based diversity in the top management team also lead to greater strategic change and long-term organizational performance ( Wu et al. , 2019 ). The collective actions of these leaders determine organizational outcomes ( Georgakakis et al. , 2019 ). Their social processes in strategic decision-making result in the capability of taking advantage of an opportunity or addressing specific challenges ( Kauppila et al. , 2018 ). Moreover, the past experience of senior leaders determines how they form affiliations, the patterns of their decisions and ultimately which acquisitions they pursue ( Zhang and Greve, 2019 ).

The specific formal and informal structures of roles in the top management team determine the team's behavior, strategic decisions and organizational legitimacy. These in turn drive organizational performance ( Ma et al. , 2021 ). Moreover, it is the varying top management team interfaces and dominant coalitions that constitute strategic leadership and that determine organizational outcomes ( Van Doorn et al. , 2022 ). For instance, organizational performance is often dependent on the influence of the CEO and the comprehensiveness of the decision process ( Friedman and Carmeli, 2022 ). Organizations need interfaces between the CEO and the top management team that allow them to balance the rigor that comes from debate, diverse ideas and decision-making speed ( Bartkus et al. , 2022 ).

A recent review of upper echelons literature shows that there is a need for more comprehensive research on the relational mechanisms in top management teams, the impact thereof on organizational performance and the role of context in this relationship ( Neely et al. , 2020 ).

Given the importance of configurations of upper echelons decision-making in organizational outcomes, we can infer that strategic leader indecision directly impacts the strategic leadership function. However, it is not yet clear how the interpersonal relationships in top management teams influence strategic leader indecision. It is therefore important to first understand what the literature says about indecision.

In ordinary language, indecision refers to “the state of being unable to make a choice”, or “wavering between two or more possible courses of action” ( Merriam-Webster, n.d. ). Although Kokkoris et al. (2019) differentiated between the persistent trait of indecisiveness, operationalized as decision inability across different life domains and indecision, Cheek and Goebel (2020) demonstrated that indecision is similar to decision difficulty. Indecision leads to prolonged decision-making processes, attempts to delay or avoid decisions and anxiety or emotional concern once the decision has been made ( Cheek and Goebel, 2020 ). We adopt a definition of indecision that includes indecisiveness and decision difficulty ( Barkley-Levenson and Fox, 2016 ). Indecisiveness is a form of procrastination where the decision-maker, instead of delaying the start or completion of tasks, experiences anxiety for delaying the decision-making thought processes ( Tibbett and Ferrari, 2015 ). Indecision is accompanied by feelings of ineffectiveness, apprehension, worry and regret ( Taillefer et al. , 2016 ; Bavolar, 2018 ; Bernheim and Bodoh-Creed, 2020 ). In contrast, decisiveness refers to making timely decisions notwithstanding any prevailing uncertainty ( Bernheim and Bodoh-Creed, 2020 ).

Antecedent of indecision

There are multiple and diverse viewpoints on the antecedents of indecision in literature. From psychology literature, we know that low future and present orientation predict indecision and that the desire for complex and engaging cognitive tasks inversely predicts indecision ( Díaz-Morales et al. , 2008 ). Because strategic leaders need to be future-oriented and work with complex challenges ( Kouzes and Posner, 1996 ; Schoemaker et al. , 2018 ) understanding strategic leader indecision is important.

The collective and collaborative nature of strategic decision-making may result in a network of indecision. Cumulative events, the presence of a constant risk of reversal, re-orientation and project expansion may worsen leader indecision ( Denis et al. , 2011 ). According to Denis et al. (2011) , indecision escalates when constraints in the environment cause leaders to pre-maturely concretize a decision and when divergent views lead to strategic ambiguity. These processes escalate to increase decision complexity. Tasselli and Kilduff (2018) concur that collaboration and trust in friendship networks may overcome indecision or decision paralysis. The importance of trust in decision-making raises the question as to which other interpersonal and organizational factors lead to indecision in top management.

According to Brooks (2011) , the primary antecedents of indecision are the decision context, systemic biases and potential traits. The context plays a role in indecision when decision-makers have no clear or attractive alternatives, or when decision options are too similar ( Feldman et al. , 2014 ). Alternatively, decision biases, such as status quo bias, may explain the cognitive processes that lead to indecision. Status quo bias, for example, offers decision-makers opportunity to escape potential regret, the need to justify the chosen direction, or to take accountability ( Tarka, 2017 ). For others, the trait of indecision is more enduring. Characteristic cognitive processes may underpin indecision, such as self-critical and defeating thoughts, perfectionism and intolerance of uncertainty ( McGarity-Palmer et al. , 2019 ). In contrast, a sense of self-awareness with the belief in free will leads to greater decisiveness ( Kokkoris et al. , 2019 ).

Aspects of the decision itself may also lie at the heart of indecision, such as the lack of information or high uncertainty of outcomes ( Rassin, 2007 ; Germeijs and De Boeck, 2003 ). Strategic leaders often have to make decisions in the context of uncertainty ( Schoemaker et al. , 2018 ) and, therefore, understanding indecision in the upper echelons is required.

The subjective experience of the decision-making process itself ( Brooks, 2011 ), post-decision negativity ( Kim and Miller, 2017 ) or regret ( Sautau, 2017 ) may also support indecision. Furthermore, Steinbach et al. (2019) argue that executives need construal or mental flexibility to better assess specific situational demands in strategic decisions.

From the literature reviewed, it appears that scholars do not yet have a comprehensive framework of the antecedents of indecision. The known antecedents of indecision include uncertain decision contexts, cognitive, affective and personal factors (including traits) and decision-specific factors. Furthermore, the interpersonal dimension of collective decision-making, typical of upper echelon processes, may appear as an additional driver of indecision. Thus, indecision results from decision-specific, intrapersonal, interpersonal and contextual drivers. We therefore need to study indecision in specific contexts and propose that the uncertainty and complexity of upper echelon decision-making contexts may reveal further drivers of indecision that this research will explore.

Consequences of strategic leader indecision

The upper echelon context offers an important setting to understand the consequence of decision-making, especially indecision. Currently, the consequences of indecision are poorly understood.

From a psychological perspective, literature shows that adult indecision is a trait that may affect personal circumstances such as living conditions ( Ferrari et al. , 2018 ). Indecision may also have a negative impact on organizations. Brooks (2011) speculates that indecision may result in the foregoing of good options when decision-makers seek optimal options before they decide. Charan (2001) argues that a culture of indecision in an organization results in poor strategic execution. From an economics perspective, Gomes et al. (2012) found that government policy indecision negatively impacts citizen welfare.

Apart from these and similar isolated and dated arguments on the consequences of indecision, literature is silent on the outcomes of indecision. It is therefore important to explore the perceived consequences of indecision in senior teams.

Considering the degree to which strategic leaders impact organizational outcomes, Hambrick (2007) stated that strategic leader decisions may result in positive or negative outcomes. As strategic decisions determine organizational competitiveness ( Elbanna et al. , 2020 ), it is understandable that indecision impacts organizational level outcomes. In line with this, Samimi et al. (2019) found that indecision negatively impacts competitive advantage, growth and performance and it increases performance volatility. Indecisive leaders are not suitable for leadership positions ( Brooks, 2011 ; Taillefer et al. , 2016 ). Thus, indecision has consequences not only for organizational performance, but also for the collective and individual strategic leaders. However, not much is known about the experienced consequences of indecision among strategic leaders. We do not yet know how indecision impacts organizational level outcomes or how indecision affects strategic teams.

What are the drivers of indecision at the strategic leadership level of a complex organization?

What are the perceived consequences of indecision at the upper echelons?

Research approach and philosophy

The research employed a qualitative and exploratory research design ( Creswell and Creswell, 2018 ), following an interpretivist philosophy ( Rubin and Rubin, 2012 ) to gain emerging perspectives of real-world leaders. We made use of a single-case design in order to account for the strategic decision network effects in strategic leader indecision and the unit of analysis was the upper echelon decision-makers in the organization. We focused on gaining in-depth insights into the specific causes and consequences of indecision in the complex organization, making use of inductive logic to develop new theoretical insights ( Thorpe and Holt, 2008 ) and following a phenomenological approach ( Creswell, 2012 ) due to limited theory on indecision.

Participants

The chosen population for the study was leaders from the upper echelons of a complex organization. We confined the research setting to a debt-constrained organization facing poor economic growth. The case met the criteria of a complex environment, characterized by the multiplicity, interdependence and heterogeneity of the elements of the system ( Sargut and McGrath, 2011 ). The complexity of the organization in terms of the multiple regulatory environments and geographies offered heterogeneity in the sample ( Suzuki et al ., 2007 ). The population represented various client segments, functional areas and regions across sub-Saharan Africa, ensuring client, functional and geographic diversification in the sample.

Through homogenous purposive sampling ( Yin, 2016 ) and criterion sampling ( Suri, 2011 ), the sample frame included strategic leaders with more than ten years of experience within a given client segment, functional area, or geography and with executive committee level accountability. The sample of upper echelon decision-makers encompassed business unit leaders, country executive leaders and direct reports of business unit and country heads for greater data legitimacy. This enabled the gathering of rich data which may be applicable to other regulated and complex organizations in the financial services industry. The sample size was determined when data saturation and data richness ( Gentles et al. , 2015 ) were attained at fifteen interviews and data gathering continued to the twentieth interview.

Table 1 presents the profile of the interviewees.

Data gathering and analysis

The study made use of a semi-structured interview guide that offered rich insights into how strategic leaders experience the phenomenon of indecision ( Silverman, 2011 ) and contained open-ended and non-leading questions ( Josselson, 2013 ). Participants were asked about their experience of indecision in the organization, why strategic leaders in the organization delay or delegate decisions and what they perceived the implications of indecision, delayed and delegated decisions were. The interviewer prompted the participants to give examples.

Interviews were conducted one-on-one and via face-to-face or online platforms. All participants offered prior consent to the recording of interviews. The interviews were conducted over a period of 10 weeks, as many of the participants were elite informants with busy diaries ( Solarino and Aguinis, 2021 ). The data were transcribed, and all data were stored and reported without identifiers. The interviews constituted 153,747 words.

We employed thematic analysis ( Braun and Clarke, 2006 ) of the data, making use of Atlas.ti coding software. This included the six steps of reading the transcripts to gain familiarity with the data, assigning inductive codes to the data line-by-line, searching for categories within the themes of the drivers of consequences of indecision and making sense of and naming the categories before producing the reports. Thus, the first step of the analysis process was iterative through open coding, including the reading of the transcripts, coding and generation of descriptions, followed by axial coding to generate categories ( Farmer and Farmer, 2021 ).

While conducting open coding, the first author consulted with the second author on codes and categories. The first order codes were categorized according to two themes, namely drivers and consequences of strategic indecision according to the research questions ( Grodal et al. , 2021 ). During the axial coding phase, subcategories were created from the codes for these two nested analytical categories ( Saldaña, 2015 ). During the categorization process, the authors compared categories while continually asking questions about where best to position the codes under categories of consequences and drivers of indecision. Finally, the categories were merged to create similar layers of drivers and consequences and the questioning process continued to ensure that the sub-category titles represented the codes well. We then sequenced the categories logically in the presentation of results ( Grodal et al. , 2021 ).

To ensure the trustworthiness of the data analysis process, both authors compared the codes and categories and reviewed the findings several times ( Strauss and Corbin, 1998 ). The researchers practiced reflexivity during the coding process ( May and Perry, 2017 ).

The responses yielded organizational, interpersonal and intrapersonal categories of drivers of indecision and organizational and interpersonal categories of the consequences of indecision, confirmed through the authors' investigator triangulation ( Fusch et al. , 2018 ) to enhance the dependability of the analysis ( Farmer and Farmer, 2021 ).

The sampling frame incorporating the top three layers of upper echelon decision-making supported the legitimacy and credibility of the data ( Yin, 2016 ). The research process was dependable and confirmable as we followed standard data gathering and analysis processes ( Morse et al. , 2002 ). The research also adhered to the university's ethical clearance processes, which included assurance of confidentiality and anonymity of results.

The findings are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2 , according to the two central themes of the study, namely drivers and outcomes of strategic leader indecision.

Antecedents of strategic leader indecision

The results yielded specific organizational, interpersonal and intrapersonal experiences as drivers of strategic leader indecision, as can be seen in the categories and illustrative quotations in this section.

Organizational drivers

The codes yielded four categories of organizational drivers of indecision, namely hierarchy, complexity, geographical jurisdictions, and operational constraints (specifically, budgets). These contextual categories of indecision expand on the environmental constraints previously shown to drive indecision ( Denis et al. , 2011 ).

Context and geographical reach

The fact that we are slow in decision-making ourselves as [an] organisation in East Africa, [is] because the ultimate decision-makers don’t reside in this jurisdiction. (P9)

… you’re going to get in-country chief executive in Kenya saying ‘nah, but that doesn’t work for me’, you know? Or an in-country chief executive in Botswana saying ‘our case is completely different’. (P5)

Yet, when it comes to driving Africa’s growth, we then tend to hesitate on who we support because we are then marking them against global giants. (P7)

I can’t go and talk about multinationals in South Sudan. There are no big multinationals. (P9)

There was a lot of this animosity between the organization in London and operations and all the teams on this side [Johannesburg], and we were trying to figure out who makes what calls and, you know, how do we manage this thing? (P6)

Organizational hierarchical structure

But as soon as I start waiting for a meeting with [the] Chief Executive and he has to go and see this one. And that one will then take the message across to someone else. It can take forever. […] It’s not because of those people. It’s just the organizational structure. (P15)

So, you can see, for me, it attributed to [the fact that] you’re so concerned and so consumed by the hierarchy and what the hierarchy thinks. […] so that it ends up stifling decision-making. (P9)

We’ve created for ourselves in [the] organization, considerable complexity in this time. But, it is a matter of survival for us, and it is unavoidable that we have to do this in that we’ve launched a massive preservation program in the organization while we all are operating in a very complex context. (P19)

I think one of the big areas of moving towards being decisive as a collective, because for me, let me answer the question in a way that says we are, as I said ‘We are not indecisive as individuals. We are indecisive as a collective’. (P5)

These quotes illustrate several reasons why indecisiveness had emerged, from competing interests and animosity, structural complexity and a collective culture of indecisiveness.

Operational budget constraints and competitiveness

So, I think, I think we still do have turf protection, which we would call ‘the silos’. So, it’s sort of, there’s this mentality, ‘my turf, my budget, my bonus’, and, you know, those three are interlinked. (P20)

From these findings it appears that complex organizations have regional, structural and procedural characteristics that can lead to strategic leader indecision.

Interpersonal drivers

We know from the literature that trust is required to overcome indecision ( Tasselli and Kilduff, 2018 ). However, the analysis revealed several negative interpersonal drivers of strategic leader indecision, namely power influences, lack of peer support, lack of trust and the need to avoid conflict. This is significant because organizational performance is dependent on the combined efforts of the top management team ( Georgakakis et al. , 2019 ).

Interpersonal dynamics: power influences

And if there’s a bit of resistance from this informal structure, unfortunately, this informal structure is quite strong, quite strong, in the sense that it can sabotage any decision or any process within the system because it takes things beyond the organisation itself. […] A lot of guys within the [formal] system still consult the informal structures. There’s a lot of stuff that happens over ‘braais’ and over weekends in South Africa that influence a lot of the decisions that are made. (P1)

People in [unit 2] would be very angry with that person. You know, if they favored [unit 1], the [unit 2] people would be up in arms. So, I think for me, the reasons for the delay in that project were mainly political. (P20)

Interpersonal dynamics: lack of peer support

And then I understood I had the chief executive’s backing and others. Suddenly, I was able to stand on my own two feet and physically make decisions and make decisions that were unpopular that went against the grain. (P8)

You need to be very confident in your solution and in your mandate and in some of these instances that the backing of your boss to make progress. (P14)

Interpersonal reactions: lack of trust

I think a lot of the time where we are not making decisions or have indecision is due to a lack of trust. (P2)

It’s because of the people’s lack of trust in the leadership. Because, if they see you being indecisive, it makes them trust you less. (P3)

But it’s almost impossible to get agreement. And that leads to long delays in getting to answers and agreeing to stuff, lobbying beforehand, lobbying afterward. And I think that flies in the face of the notion of empowerment and trust, and then that those delays, those things make people question, you know. They lose confidence. They wonder if there’s credibility. (P14)

I think unit one couldn’t trust unit two to go and launch a similar product and not try and cannibalize the business, and unit two probably couldn’t trust unit one to make the right decision for the organization, which was actually a favorable decision for unit one’s customers, at that point. (P20)

Interpersonal reactions: conflict avoidance

There are always people that like to avoid conflict and they would just avoid it and they would avoid it in one way or other by being rolled over or simply by avoiding the problem and putting their head in the sand. And hoping that the problem goes away. (P5)

These findings provide new evidence of the drivers of indecision. This stands in contrast to a sense of safety to debate and integrate diverse views in order to attain fast and rigorous decision-making ( Bartkus et al. , 2022 ).

Personal drivers

Apart from the organizational and interpersonal factors of indecision revealed, the research also uncovered personal drivers of indecision in the upper echelons. Previous findings have shown that indecision may result from personal drivers such as enduring traits ( McGarity-Palmer et al. , 2019 ), present-mindedness ( Díaz-Morales et al. , 2008 ), or status quo bias ( Tarka, 2017 ). Our findings begin to unveil the impact of fear on indecision in the upper echelons. The primary personal drivers of indecision for these strategic leaders were fear of failure and fear of accountability.

Fear of failure

I guess at [this organization,] for me, that drive is fear. Okay. So, [it’s] people’s fear around making the incorrect decision. (P9)

The spotlight is on. You have big mandates, siyasaba [we are scared (Zulu)] to fail. (P8)

You know, it’s a very interesting one because I would think, there’s a lot of insecurity around decision-making in today’s world. I think the insecurity among strategic leaders is coming from a fear of failure, you know. (P20)

So, the one thing is, it’s [lack of] confidence [and] insecurity. And I think the fear factor, of failing. I think they’re still too fearful, and we’re fearful, partly because of, I think it’s in our DNA. (P6)

And I think that’s probably another thing that I think scares us or makes us not make a decision as [an] organization – fear of failure. I think it all comes up from ‘if we fail, what do we do?’. I think that’s probably why they were too afraid to fail – that we’re failing in small bits day by day. (P3)

You don’t want to make big decisions anymore, because when you don’t make big decisions, you can’t get big things wrong. (P17)

Fear of accountability

We are fearful of being called out on something as standing up for something. (P5).

In my world, the pressure and the spotlight are not on me. So, I can make that decision right there on a lot of other things. There’s a lot of space and freedom for me to hide behind others. (P19).

And nobody takes responsibility for anything. And we end up having decisions that don’t reflect what the real thought processes are, because everybody’s hiding behind everybody to come up to the point of decision-making. (P3)

Further reasons cited for fear of accountability included the belief that others in the team may be smarter and more suitable to make decisions and fear of being singled out as the decision-maker.

From these intrapersonal drivers of indecision, we may infer organizational context may result in fears of making mistakes, of not knowing and of being held accountable should they fail and this may be increased in a culture where fear of failure, interpersonal distrust and power dynamics are at play. The findings expand on previous research on indecision in organizations ( Denis et al. , 2011 ), by offering new insights on the role of culture in driving fear-based indecision in the top management team.

Overall, the findings on the antecedents of strategic leader indecision in a complex organization show a new interrelated dynamic between characteristics of the complex organization in which power dynamics and lack of trust in relations among strategic leaders translate into fear of failure and failure to take accountability at the individual level. Together these dynamics may drive strategic leader indecision in an organization.

Research has shown that indecision can impact organizational performance ( Samimi et al. , 2019 ). Our findings show why indecision impacts organizational performance. Moreover, the findings now reveal team-based consequences that may impact the effectiveness of the top management team. As per Figure 1 and Table 3 , we found organizational, interpersonal and personal consequences and implications of strategic leader indecision.

Organizational consequences

The organizational consequences of strategic leader indecision included both diminished competitive advantage and consequences for the resources of the organization. Previous literature argues that indecision may lead to missed decision opportunities ( Brooks, 2011 ), and a lack of strategy execution ( Charan, 2001 ). Our analysis demonstrated that the strategic leaders perceived the organizational consequences of indecision to include the loss of resources, revenue loss and missed opportunities, while giving competitors an advantage. The findings thus offer reasons for why strategic leaders' indecision impacts organizational outcomes. There was a view that the longer that the decision-making process lasts, the greater the potential business loss becomes.

Diminished competitiveness: competitor advantage

Indecisiveness and when our strategic leaders avoid making decisions decisively means that our competitors will become stronger relative to us. (P14)

Consequences of not making the right decision are immediate and they’re real. (P1)

Diminished competitiveness: opportunity loss

What are the implications, you know? I suppose the question could be, it should be ‘Where could we have been?’ Those organizations that positioned themselves to be ecosystems or platforms are reaping a multiplier, in terms of, earnings and profitability compared to those who are not. (P11)

So, to talk to your point of implications is, if we continue the pace of decision-making that requires long-term consultation and consensus, I think we were going to lose some opportunities. So, we begin to stagnate. (P20)

I think indecision is the real cost to the business, which is difficult to quantify because it just means things take long. (P4)

Resource-based consequences: loss of resources

There are many implications, you lose staff. A lot of staff will go to institutions that can take decisions. (P3)

I think it’s got an impact, indecision leads to loss of confidence, loss of money, loss of good quality clients. And it’s like a negative cycle of delayed implementation and no impact. (P14)

Resource-based consequences: financial loss

Years later, you know, a Chief Executive is crying on our shoulders because he doesn’t have anything with which to compete in the market. (P18)

So, the implications of indecision for an organization is quite varied, right? From a shareholder point of view, it leads to reduced revenue and headline earnings, because you’re not going to be able to connect at the right time to take advantage of opportunities. (P17)

I thought, the first implication is, our client franchise stagnates. So, I’d say we lose momentum, and our competitors become stronger. (P20)

From these various perspectives, it is evident that the effect of strategic leader indecision manifests in multiple forms of loss and ultimately affects the competitive advantage of an organization. The losses include depletion of staff, confidence, money, clients and growth opportunities. Therefore, it appears that upper echelon indecision affects the competitiveness of the organization. From upper echelons theory, we expect that the top management team would enable positive organizational performance ( Aboramadan, 2021 ; Neely et al. , 2020 ). The findings however show that in the context of indecision, the opposite outcome may occur.

Interpersonal consequences

In recent literature, there has been growing awareness of the importance of the interfaces of the top management team to enable strategic decisions for positive organizational outcomes ( Ma et al. , 2021 ; Van Doorn et al. , 2022 ). The second category of consequences of indecision that the participants raised showed the effect of indecision on these interpersonal connections.

Influence on culture: inaction and blame-shifting

I think if indecision happens at a senior level, you can break the whole organization because if there is […] a second layer that is a very strong layer of people, they can really move your organization forward. But if there is indecision just above [them], that creates uncertainty […] Further, I think, you know, that layer goes into freeze mode […] a blame culture inevitably becomes fortified […] and you just feel a ripple effect throughout the whole organization. (P6)

Influence on the team: poor team focus

I think indecision is the real cost to the business, which is difficult to quantify because it just means things take long, it means that teams, instead of being focusing on doing the right thing, you know, they get caught up in this, and that, what is going to happen, and they, you know, they are not focusing on the right things. (P4)

Influence on the team: loss of trust

I think those are some of the implications I’ve seen, for the team around you: if you are not making decisions quickly or helping them, they might begin to lose confidence and trust. And it could be ‘I don’t trust them. I don’t know what I’m doing’. (P13)

The staff morale goes down. So, there’s a real cost to it. […] It means that teams, instead of being focusing on doing the right thing, you know, they get caught up in this ‘What’s going to happen?’ [mindset], and they, you know, they’re not focusing on the right things. (P4)

Personal consequences

I guess this is leadership fatigue, and more like just being indifferent. It is like, ‘oh, we have had this before’. […] Even on something well-meaning, probably very important, but, because of our history [of delays or inaction] or just not implementing properly, it just makes leaders not criticize, to not do anything, to just live through the emotion and not do anything [with an attitude of] ‘this too shall pass’. (P10)

I think there is one of the implications of delaying decisions because they have been waiting for something and then the organization can’t make the decision. (P20)

These findings explain how decision opportunities may be wasted ( Brooks, 2011 ) due to interpersonal and personal consequences of senior leader indecision.

Overall, these results show a circular relationship between a complex context, the culture of indecisiveness and personal fears that have an impact on interpersonal relations and ultimately the strategic performance of the organization. The results hold several implications for organizational design, culture development and leadership development.

Although much has been written about upper echelon decision-making ( Samimi et al. , 2019 ), up to now little is known about indecision in top management teams in complex organizations. This study provides new insights into how organizational, interpersonal and intrapersonal factors play a role in senior leader indecision. The findings show several organizational drivers of indecision, namely the organizational hierarchical structure, the complexity of an organization, geographical jurisdictions and budgetary constraints. Previously, Denis et al. (2011) have shown how ambiguity in projects may lead to indecision. Our research is the first to explore senior leader indecision in complexity.

We also found several interpersonal drivers of top management indecision, including informal power relationships, lack of peer support, lack of trust and conflict avoidance. This begins to address the call for more research on the relational mechanisms in upper echelons ( Neely et al. , 2020 ) by showing how poor relationships and culture may negatively impact organizational performance.

Further, we found personal drivers of indecision, namely fear of failure and fear of taking accountability for decisions. Because upper echelon decisions hold direct implications for organizational performance ( Georgakakis et al. , 2019 ), the research contributes by revealing further consequences of indecision. We found that at the organizational level, consequences of indecision include the depletion of resources, revenue, opportunities and competitive advantage.

In terms of the interpersonal consequences of indecision ( Neely et al. , 2020 ), we found that the senior team members become distrustful and weary, that team members become unfocused and that a culture of blame-shifting develops. A personal consequence of indecision is that leaders developed decision-making fatigue.

Theoretical implications

This research extends the understanding within upper echelons theory that strategic leaders collectively ( Georgakakis et al. , 2019 ) impact organizational performance in the long term ( Goldman and Casey, 2010 ). It also builds on the understanding of the dynamic interaction between constraining environment and resultant ambiguity that leads to indecision ( Denis et al. , 2011 ).

While we know that indecision may occur when there are divergent views ( Denis et al. , 2011 ) and lack of trust ( Tasselli and Kilduff, 2018 ), the findings confirm the presence of a lack of trust, coupled with power influence and conflict avoidance strategies that manifest in indecision. This finding is significant given the role of strategic leaders in influencing strategy execution ( Barstardoz and Van Vugt, 2019 ). Furthermore, the research exposes cultural drivers of indecision, showing a negative impact on strategic decision-making ( Hambrick, 2007 ).