Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Writing a case report...

Writing a case report in 10 steps

- Related content

- Peer review

- Victoria Stokes , foundation year 2 doctor, trauma and orthopaedics, Basildon Hospital ,

- Caroline Fertleman , paediatrics consultant, The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust

- victoria.stokes1{at}nhs.net

Victoria Stokes and Caroline Fertleman explain how to turn an interesting case or unusual presentation into an educational report

It is common practice in medicine that when we come across an interesting case with an unusual presentation or a surprise twist, we must tell the rest of the medical world. This is how we continue our lifelong learning and aid faster diagnosis and treatment for patients.

It usually falls to the junior to write up the case, so here are a few simple tips to get you started.

First steps

Begin by sitting down with your medical team to discuss the interesting aspects of the case and the learning points to highlight. Ideally, a registrar or middle grade will mentor you and give you guidance. Another junior doctor or medical student may also be keen to be involved. Allocate jobs to split the workload, set a deadline and work timeframe, and discuss the order in which the authors will be listed. All listed authors should contribute substantially, with the person doing most of the work put first and the guarantor (usually the most senior team member) at the end.

Getting consent

Gain permission and written consent to write up the case from the patient or parents, if your patient is a child, and keep a copy because you will need it later for submission to journals.

Information gathering

Gather all the information from the medical notes and the hospital’s electronic systems, including copies of blood results and imaging, as medical notes often disappear when the patient is discharged and are notoriously difficult to find again. Remember to anonymise the data according to your local hospital policy.

Write up the case emphasising the interesting points of the presentation, investigations leading to diagnosis, and management of the disease/pathology. Get input on the case from all members of the team, highlighting their involvement. Also include the prognosis of the patient, if known, as the reader will want to know the outcome.

Coming up with a title

Discuss a title with your supervisor and other members of the team, as this provides the focus for your article. The title should be concise and interesting but should also enable people to find it in medical literature search engines. Also think about how you will present your case study—for example, a poster presentation or scientific paper—and consider potential journals or conferences, as you may need to write in a particular style or format.

Background research

Research the disease/pathology that is the focus of your article and write a background paragraph or two, highlighting the relevance of your case report in relation to this. If you are struggling, seek the opinion of a specialist who may know of relevant articles or texts. Another good resource is your hospital library, where staff are often more than happy to help with literature searches.

How your case is different

Move on to explore how the case presented differently to the admitting team. Alternatively, if your report is focused on management, explore the difficulties the team came across and alternative options for treatment.

Finish by explaining why your case report adds to the medical literature and highlight any learning points.

Writing an abstract

The abstract should be no longer than 100-200 words and should highlight all your key points concisely. This can be harder than writing the full article and needs special care as it will be used to judge whether your case is accepted for presentation or publication.

Discuss with your supervisor or team about options for presenting or publishing your case report. At the very least, you should present your article locally within a departmental or team meeting or at a hospital grand round. Well done!

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ’s policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing a Case Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Bibliography

The term case study refers to both a method of analysis and a specific research design for examining a problem, both of which are used in most circumstances to generalize across populations. This tab focuses on the latter--how to design and organize a research paper in the social sciences that analyzes a specific case.

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or among more than two subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in this writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a single case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- Does the case represent an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- Does the case provide important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- Does the case challenge and offer a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in practice. A case may offer you an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to the study a case in order to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- Does the case provide an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings in order to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- Does the case offer a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for exploratory research that points to a need for further examination of the research problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of Uganda. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a particular village can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community throughout rural regions of east Africa. The case could also point to the need for scholars to apply feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation.

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work. In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What was I studying? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why was this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the research problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would include summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to study the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in the context of explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular subject of analysis to study and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that frames your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; c) what were the consequences of the event.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experience he or she has had that provides an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of his/her experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using him or her as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, cultural, economic, political, etc.], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, why study Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research reveals Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks from overseas reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should be linked to the findings from the literature review. Be sure to cite any prior studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for investigating the research problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is more common to combine a description of the findings with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings It is important to remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and needs for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) restate the main argument supported by the findings from the analysis of your case; 2) clearly state the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in and your professor's preferences, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented applied to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were on social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood differently than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis.

Case Studies . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical (context-dependent) knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Essays

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2023 10:50 AM

- URL: https://libguides.pointloma.edu/ResearchPaper

Advertisement

Reactive arthritis following COVID-19: clinical case presentation and literature review

- Case Based Review

- Published: 06 October 2023

- Volume 44 , pages 191–195, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Dana Bekaryssova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9651-7295 1 ,

- Marlen Yessirkepov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2511-6918 1 &

- Sholpan Bekarissova ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-1359-9859 2

224 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

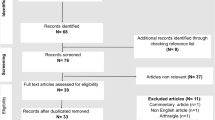

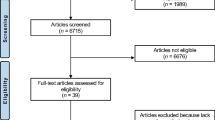

Reactive arthritis (ReA) is a clinical condition typically triggered by extra-articular bacterial infections and often associated with the presence of HLA-B27. While ReA has traditionally been associated with gastrointestinal and genitourinary infections, its pathogenesis involves immune and inflammatory responses that lead to joint affections. The emergence of COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has prompted studies of plausible associations of the virus with ReA. We present a case of ReA in a patient who survived COVID-19 and presented with joint affections. The patient, a 31-year-old man, presented with lower limb joints pain. SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed by PCR testing during COVID-19-associated pneumonia. Following a thorough examination and exclusion of all ReA-associated infections, a diagnosis of ReA after COVID-19 was confirmed. In addition, this article encompasses a study of similar clinical cases of ReA following COVID-19 reported worldwide.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Reactive arthritis occurring after COVID-19 infection: a narrative review

Maroua Slouma, Maissa Abbes, … Bassem Louzir

Reactive arthritis following COVID-19 current evidence, diagnosis, and management strategies

Filippo Migliorini, Andreas Bell, … Nicola Maffulli

Reactive arthritis after COVID-19: a case-based review

Burhan Fatih Kocyigit & Ahmet Akyol

Zeidler H, Hudson AP (2021) Reactive arthritis update: spotlight on new and rare infectious agents implicated as pathogens. Curr Rheumatol Rep 23(7):53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-021-01018-6

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Medical Subject Headings Dictionary (MESH) Joint Diseases. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=reactive+arthritis . Accessed 27 June 2023

Leirisalo-Repo M (2005) Reactive arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 34(4):251–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009740500202540

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Gravano DM, Hoyer KK (2013) Promotion and prevention of autoimmune disease by CD8+ T cells. J Autoimmun 45:68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2013.06.004

Selmi C, Gershwin ME (2014) Diagnosis and classification of reactive arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 13(4–5):546–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.005

Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Kanelleas A, Katsambas A, Antoniou C (2015) Reactive arthritis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29(3):415–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12741

Pal A, Roongta R, Mondal S, Sinha D, Sinhamahapatra P, Ghosh A, Chattopadhyay A (2023) Does post-COVID reactive arthritis exist? Experience of a tertiary care centre with a review of the literature. Reumatol Clin(Engl Ed) 19(2):67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reumae.2022.03.005

Jubber A, Moorthy A (2021) Reactive arthritis: a clinical review. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 51(3):288–297. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2021.319

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bekaryssova D, Joshi M, Gupta L, Yessirkepov M, Gupta P, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY, Ahmed S, Kitas GD, Agarwal V (2022) Knowledge and perceptions of reactive arthritis diagnosis and management among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: online survey. J Korean Med Sci 37(50):e355. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e355

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hannu T (2011) Reactive arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 25(3):347–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2011.01.018

Leirisalo-Repo M, Hannu T, Mattila L (2003) Microbial factors in spondyloarthropathies: insights from population studies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 15(4):408–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002281-200307000-00006

Bremell T, Bjelle A, Svedhem A (1991) Rheumatic symptoms following an outbreak of campylobacter enteritis: a five year follow up. Ann Rheum Dis 50(12):934–938. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.50.12.934

Bekaryssova D, Yessirkepov M, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY, Ahmed S (2022) Reactive arthritis before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Rheumatol 41(6):1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06120-3

Danssaert Z, Raum G, Hemtasilpa S (2020) Reactive arthritis in a 37-year-old female with SARS-CoV2 infection. Cureus 12(8):e9698. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9698

Migliorini F, Karlsson J, Maffulli N (2023) Reactive arthritis following COVID-19: cause for concern. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31(6):2068–2070. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07332-z

Seet D, Yan G, Cho J (2023) Reactive arthritis in a patient with COVID-19 infection and pleural tuberculosis. Singapore Med J. https://doi.org/10.4103/singaporemedj.SMJ-2021-132

Wendling D, Verhoeven F, Chouk M, Prati C (2021) Can SARS-CoV-2 trigger reactive arthritis? Joint Bone Spine 88(1):105086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2020.105086

Dombret S, Skapenko A, Schulze-Koops H (2022) Reactive arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. RMD Open 8(2):e002519. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002519

Bekaryssova D, Yessirkepov M, Mahmudov K (2023) Structure, demography, and medico-social characteristics of articular syndrome in rheumatic diseases: a retrospective monocentric analysis of 2019–2021 data. Rheumatol Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05435-x

Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S (2020) Cytokine storm in COVID-19: pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol 39(7):2085–2094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05190-5

Yadav S, Bonnes SL, Gilman EA, Mueller MR, Collins NM, Hurt RT, Ganesh R (2023) Inflammatory arthritis After COVID-19: A Case Series. Am J Case Rep 24:e939870. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.939870

Brahem M, Jomaa O, Arfa S, Sarraj R, Tekaya R, Berriche O, Hachfi H, Younes M (2023) Acute arthritis following SARS-CoV-2 infection: about two cases. Clin Case Rep 11(5):e7334. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.7334

Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD (2011) Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int 31(11):1409–1417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3

Cincinelli G, Di Taranto R, Orsini F, Rindone A, Murgo A, Caporali R (2021) A case report of monoarthritis in a COVID-19 patient and literature review: simple actions for complex times. Medicine (Baltimore) 100(23):e26089. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000026089

Saricaoglu EM, Hasanoglu I, Guner R (2021) The first reactive arthritis case associated with COVID-19. J Med Virol 93(1):192–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26296

Gasparotto M, Framba V, Piovella C, Doria A, Iaccarino L (2021) Post-COVID-19 arthritis: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol 40(8):3357–3362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05550-1

Basheikh M (2022) Reactive arthritis after COVID-19: a case report. Cureus 14(4):e24096. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.24096

Shokraee K, Moradi S, Eftekhari T, Shajari R, Masoumi M (2021) Reactive arthritis in the right hip following COVID-19 infection: a case report. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 7(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40794-021-00142-6

Ouedraogo F, Navara R, Thapa R, Patel KG (2021) Reactive arthritis post-SARS-CoV-2. Cureus 13(9):e18139. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18139

Coath FL, Mackay J, Gaffney JK (2021) Axial presentation of reactive arthritis secondary to COVID-19 infection. Rheumatology (Oxford) 60(7):e232–e233. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab009

Hønge BL, Hermansen MF, Storgaard M (2021) Reactive arthritis after COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 14(3):e241375. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-241375

Kocyigit BF, Akyol A (2021) Reactive arthritis after COVID-19: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int 41(11):2031–2039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04998-x

Sureja NP, Nandamuri D (2021) Reactive arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Rheumatol Adv Pract 5(1):rkab001. https://doi.org/10.1093/rap/rkab001

Farisogullari B, Pinto AS, Machado PM (2022) COVID-19-associated arthritis: an emerging new entity? RMD Open 8(2):e002026. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-002026

Leirisalo M, Skylv G, Kousa M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Suoranta H, Nissilä M, Hvidman L, Nielsen ED, Svejgaard A, Tilikainen A, Laitinen O (1982) Followup study on patients with Reiter’s disease and reactive arthritis, with special reference to HLA-B27. Arthritis Rheum 25(3):249–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780250302

Daher J, Nammour M, Nammour AG, Tannoury E, Sisco-Wise L (2023) Reactive arthritis following coronavirus 2019 infection in a pediatric patient: a rare case report. J Hand Surg Glob Online 5(4):483–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsg.2023.04.012

Jali I (2020) Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. Cureus 12(11):e11761. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.11761

Bekaryssova D, Yessirkepov M, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY, Ahmed S (2022) Revisiting reactive arthritis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Rheumatol 41(8):2611–2612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06252-6

Ono K, Kishimoto M, Shimasaki T, Uchida H, Kurai D, Deshpande GA, Komagata Y, Kaname S (2020) Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. RMD Open 6(2):e001350. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001350

Yokogawa N, Minematsu N, Katano H, Suzuki T (2021) Case of acute arthritis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Rheum Dis 80(6):e101. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218281

Migliorini F, Bell A, Vaishya R, Eschweiler J, Hildebrand F, Maffulli N (2023) Reactive arthritis following COVID-19 current evidence, diagnosis, and management strategies. J Orthop Surg Res 18(1):205. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03651-6

Ergözen S, Kaya E (2021) Avascular necrosis due to corticosteroid therapy in covid-19 as a syndemic. Cent Asian J Med Hypotheses Ethics 2(2):91–95. https://doi.org/10.47316/cajmhe.2021.2.2.03

Baimukhamedov C, Botabekova A, Lessova Z, Abshenov B, Kurmanali N (2023) Osteonecrosis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int 43(7):1377–1378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05332-3

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Biology and Biochemistry, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan

Dana Bekaryssova & Marlen Yessirkepov

Astana Medical University, Astana, Kazakhstan

Sholpan Bekarissova

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All co-authors have contributed substantially to the concept, case description, searches of relevant articles, and revisions. They approved the final version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dana Bekaryssova .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bekaryssova, D., Yessirkepov, M. & Bekarissova, S. Reactive arthritis following COVID-19: clinical case presentation and literature review. Rheumatol Int 44 , 191–195 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05480-6

Download citation

Received : 10 September 2023

Accepted : 22 September 2023

Published : 06 October 2023

Issue Date : January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05480-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case reports

- Reactive arthritis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

10 Best Literature Review Templates for Scholars and Researchers [Free PDF Attached]

Imagine being in a new country and taking a road trip without GPS. You would be so lost. Right? Similarly, think about delving into a topic without having a clue or proper understanding of the reason behind studying it.

That’s when a well-written literature review comes to the rescue. It provides a proper direction to the topic being studied.

The literature review furnishes a descriptive overview of the existing knowledge relevant to the research statement. It is a crucial step in the research process as it enables you to establish the theoretical roots of your field of interest, elucidate your ideas, and develop a suitable methodology. A literature review can include information from various sources, such as journals, books, documents, and other academic materials. This promotes in-depth understanding and analytical thinking, thereby helping in critical evaluation.

Regardless of the type of literature review — evaluative, exploratory, instrumental, systematic, and meta-analysis, a well-written article consists of three basic elements: introduction, body, and conclusion. Also its essence blooms in creating new knowledge through the process of review, critique, and synthesis.

But writing a literature review can be difficult. Right?

Relax, our collection of professionally designed templates will leave no room for mistakes or anxious feelings as they will help you present background information concisely.

10 Designs to Rethink Your Literature Reviews

These designs are fully customizable to help you establish links between your proposition and already existing literature. Our PowerPoint infographics are of the highest quality and contain relevant content. Whether you want to write a short summary or review consisting of several pages, these exclusive layouts will serve the purpose.

Let’s get started.

Template 1: Literature Review PPT Template

This literature review design is a perfect tool for any student looking to present a summary and critique of knowledge on their research statement. Using this layout, you can discuss theoretical and methodological contributions in the related field. You can also talk about past works, books, study materials, etc. The given PPT design is concise, easy to use, and will help develop a strong framework for problem-solving. Download it today.

Download this template

Template 2: Literature Review PowerPoint Slide

Looking to synthesize your latest findings and present them in a persuasive manner? Our literature review theme will help you narrow relevant information and design a framework for rational investigation. The given PPT design will enable you to present your ideas concisely. From summary details to strengths and shortcomings, this template covers it all. Grab it now.

Template 3: Literature Review Template

Craft a literature review that is both informative and persuasive with this amazing PPT slide. This predesigned layout will help you in presenting the summary of information in an engaging manner. Our themes are specifically designed to aid you in demonstrating your critical thinking and objective evaluation. So don't wait any longer – download our literature review template today.

Template 4: Comprehensive Literature Review PPT Slide

Download this tried-and-true literature review template to present a descriptive summary of your research topic statement. The given PPT layout is replete with relevant content to help you strike a balance between supporting and opposing aspects of an argument. This predesigned slide covers components such as strengths, defects, and methodology. It will assist you in cutting the clutter and focus on what's important. Grab it today.

Template 5: Literature Review for Research Project Proposal PPT

Writing a literature review can be overwhelming and time-consuming, but our project proposal PPT slides make the process much easier. This exclusive graphic will help you gather all the information you need by depicting strengths and weaknesses. It will also assist you in identifying and analyzing the most important aspects of your knowledge sources. With our helpful design, writing a literature review is easy and done. Download it now.

Template 6: Literature Review for Research Project Proposal Template

Present a comprehensive and cohesive overview of the information related to your topic with this stunning PPT slide. The given layout will enable you to put forward the facts and logic to develop a new hypothesis for testing. With this high-quality design, you can enumerate different books and study materials taken into consideration. You can also analyze and emphasize the technique opted for inquiry. Get this literature review PowerPoint presentation template now.

Template 7: Literature Review for Research Paper Proposal PowerPoint Slide

Lay a strong foundation for your research topic with this impressive PowerPoint presentation layout. It is easy to use and fully customizable. This design will help you describe the previous research done. Moreover, you can enlist the strengths and weaknesses of the study clearly. Therefore, grab it now.

Template 8: Literature Review for Research Paper Proposal PPT

Download this high-quality PPT template and write a well-formatted literature review. The given layout is professionally designed and easy to follow. It will enable you to emphasize various elements, such as materials referred to, past work, the list of books, approach for analysis, and more. So why wait? Download this PowerPoint design immediately.

Template 9: Literature Review for Academic Student Research Proposal PPT

With this exclusive graphic, you'll have everything you need to create a well-structured and convincing literature review. The given design is well-suited for students and researchers who wish to mention reliable information sources, such as books and journals, and draw inferences from them. You can even focus on the strong points of your study, thereby making an impactful research statement. Therefore, grab this PPT slide today.

Template 10: Literature Review Overview for Research Process PPT

Demonstrate your analytical skills and understanding of the topic with this predesigned PowerPoint graphic. The given research overview PPT theme is perfect for explaining what has been done in the area of your topic of interest. Using this impressive design, you can provide an accurate comparison showcasing the connections between the different works being reviewed. Get it right away.

Creating an effective literature review requires discipline, study, and patience. Our collection of templates will assist you in presenting an extensive and cohesive summary of the relevant works. These PPT layouts are professionally designed, fully editable, and visually appealing. You can modify them and create perfect presentations according to your needs. So download them now!

P.S. Are you looking for a way to communicate your individual story? Save your time with these predesigned book report templates featured in this guide .

Download the free Literature Review Template PDF .

Related posts:

- How to Design the Perfect Service Launch Presentation [Custom Launch Deck Included]

- Quarterly Business Review Presentation: All the Essential Slides You Need in Your Deck

- [Updated 2023] How to Design The Perfect Product Launch Presentation [Best Templates Included]

- 99% of the Pitches Fail! Find Out What Makes Any Startup a Success

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 11 Book Report Templates to Tell Your Inspirational Story [Free PDF Attached]

6 thoughts on “10 best literature review templates for scholars and researchers [free pdf attached]”.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

Sales funnel results presentation layouts

3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Future plan powerpoint template slide

Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

Agenda powerpoint slide show

Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

Meet our team representing in circular format

- Search Menu

- Volume 2024, Issue 3, March 2024 (In Progress)

- Volume 2024, Issue 2, February 2024

- Bariatric Surgery

- Breast Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Colorectal Surgery

- Colorectal Surgery, Upper GI Surgery

- Gynaecology

- Hepatobiliary Surgery

- Interventional Radiology

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Otorhinolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Plastic Surgery

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgery

- Upper GI Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to Submit

- About Journal of Surgical Case Reports

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, case report, conflict of interest statement.

- < Previous

A young female patient with multiple unilateral low-grade oncocytic renal tumors and angiomyolipoma: a case report and literature review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Yi Xu, Xuewen Jiang, Hui Meng, A young female patient with multiple unilateral low-grade oncocytic renal tumors and angiomyolipoma: a case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports , Volume 2024, Issue 3, March 2024, rjae125, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae125

- Permissions Icon Permissions

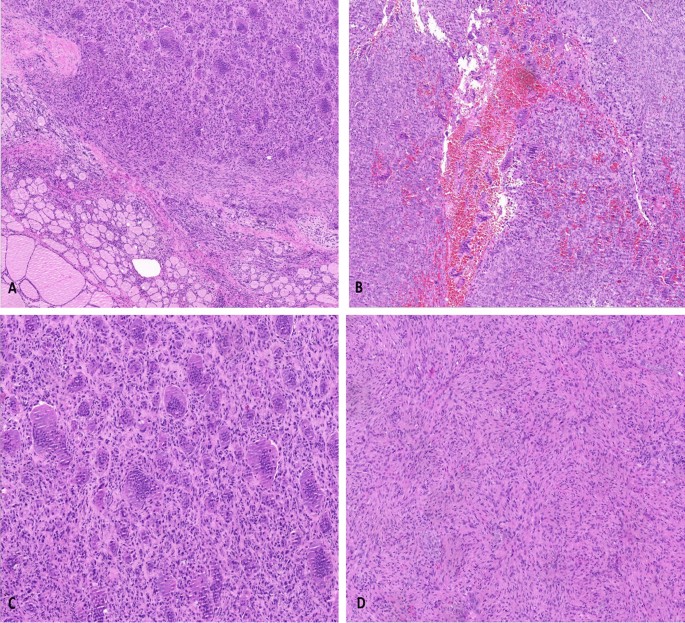

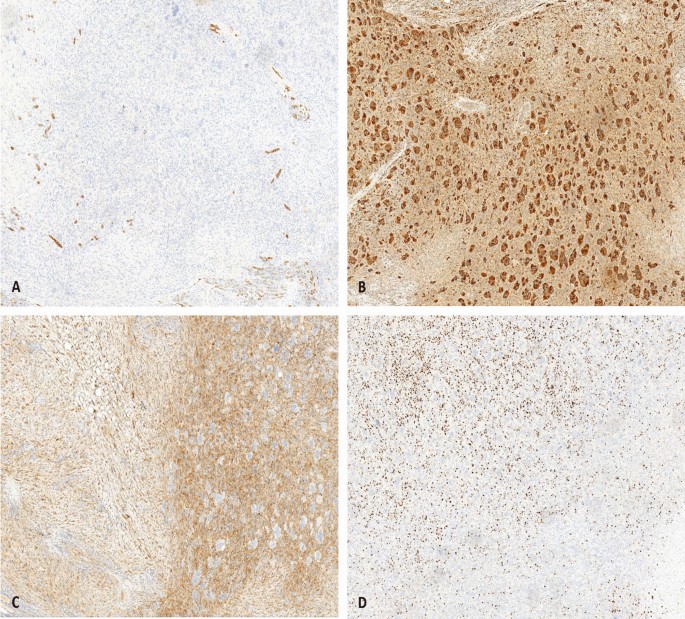

We identified a young female patient admitted for suspected renal malignancy. Partial nephrectomy was performed after imaging evaluation and discussion. Postoperative biopsy pathology reported multiple low-grade eosinophilic renal tumors (LOTs) with angiomyolipoma growth. After reviewing the data, we found that LOT was mostly solitary and occurred in middle-aged and elderly patients. This case is unique and we share it to improve the understanding of this disease.

There are many types of eosinophilic renal tumors, ranging from benign to malignant. Low-grade eosinophilic renal tumors (LOTs) have long been classified into the category of other eosinophilic tumors because of their morphological similarity to renal eosinophilic tumors (RO) and eosinophilic smoky cell carcinoma (eCRCC). To further understand their immunohistochemistry and genetics, LOTs were listed as a separate category for the first time in the 2022 classification by the World Health Organization (WHO). According to previous reports, LOTs usually occur in middle-aged and elderly patients and are primarily unilateral solitary tumors that do not grow with other tumors. We encountered a young female patient with multiple LOTs that grew simultaneously with renal angiomyolipoma (AML). We believe that the LOTs in this patient are unique, and report it here with the hope of improving our understanding of this tumor.

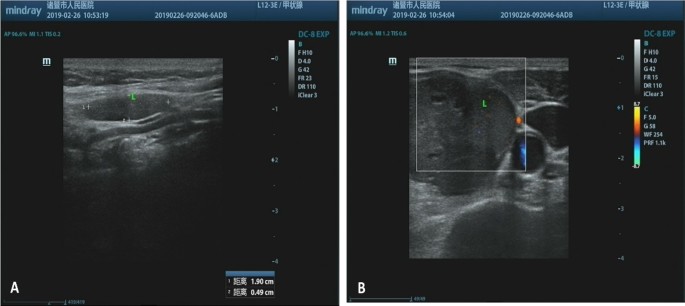

A 29-year-old female was found to have abnormal echoes in her left kidney during a physical examination. The patient had no symptoms (frequent urination, urgency, dysuria, hematuria, low back pain, abdominal pain, fever, or fatigue). She had no history of chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes and was married with children. There was no history of food or drug allergies, smoking, alcohol consumption, or family history of hereditary diseases.

No obvious positive signs were found on general physical examination upon admission, and no signs of tuberous sclerosis were observed. No lumbar mass, percussion pain in the lumbar region, pressure pain in the ureteral tract, or abnormalities in the vulva were detected during specialized examination.

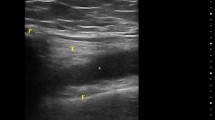

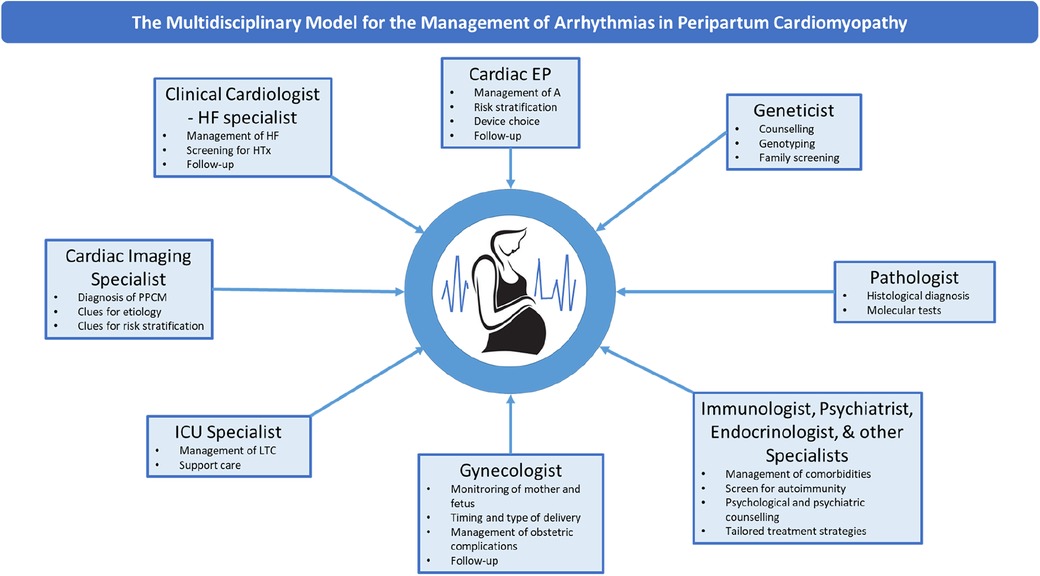

To further clarify the diagnosis, an intensive computed tomography (CT) examination of the abdominopelvic region was performed, revealing a soft tissue mass and renal tumor in the left kidney, multiple small cysts in both kidneys, and multiple high-density foci in the pelvis, lumbosacral vertebral body, and adnexa ( Fig. 1 ).

CT shows uneven density and disordered structure in the upper pole of the left kidney, with turbidity and increased density in the surrounding fat spaces.

Following a comprehensive discussion under the multidisciplinary team model, a decision was made to proceed with surgical excision of the tumor. The preoperative examination revealed no contraindications to surgery. The procedure used involved da Vinci robot-assisted laparoscopic partial left nephrectomy. Intraoperatively, a tumor measuring ~3 × 4 cm was identified at the upper pole of the left kidney, and additional satellite tumors ~0.8 cm in size were detected near the primary lesion. All tumors were excised and sent for pathological examination. Rapid intraoperative pathological analysis indicated an eosinophilic cell tumor, prompting a localized excision. The surgery progressed smoothly, and postoperative recovery was satisfactory. The patient refused further genetic testing, and a 3-month post-discharge follow-up examination revealed no abnormalities in the surgical area. The patient is currently undergoing regular follow-up.