- Non-Fiction

- Author’s Corner

- Reader’s Corner

- Writing Guide

- Book Marketing Services

- Write for us

Readers' Corner

Demystifying Book Review Writing Services: How Do They Work?

Table of contents, definition and scope, target audience, service request and submission, book selection and assignment, reviewer expertise, reviewing the book.

In today’s digital landscape, where books abound and literary works reach a global audience at the click of a button, the need for credible and compelling book reviews has never been more critical. As authors and publishers strive to capture the attention of discerning readers, the role of a reliable book review writing service has emerged as a guiding beacon in this vast sea of literary exploration.

The art of reviewing a book extends far beyond merely summarizing its contents. A well-crafted book review delves deep into the nuances of the plot, characters, writing style, and overall impact of the work, providing potential readers with valuable insights and aiding authors in honing their craft. However, amidst the plethora of review platforms and varying opinions, it can be challenging for authors and publishers to find an avenue that offers both professionalism and objectivity.

Understanding Book Review Writing Services

To grasp the essence of book review writing services, it’s essential to delve into their definition and the scope of services they offer. These specialized services go beyond the traditional book review platforms often found on retail websites or social media. Book review writing services are dedicated entities that cater to the specific needs of authors, publishers, and even self-published writers seeking professional and in-depth reviews.

These services provide a structured and well-analyzed assessment of a book’s merits, strengths, and weaknesses, presenting a balanced evaluation to potential readers. Unlike casual reviews, the ones produced by such services are thorough, reflecting the expertise of qualified book reviewers who scrutinize various aspects of the work, such as literary quality, character development, and overall coherence.

The target audience of book review writing services includes a diverse range of individuals and entities within the literary ecosystem. Authors, whether established or emerging, often turn to these services to gain valuable feedback on their creations and to build credibility and recognition. Traditional publishers leverage these services to secure unbiased opinions that can influence a book’s success in a competitive market.

Additionally, independent and self-published authors find immense value in book review writing services as they lack the support of established publishing houses. Such reviews can help them gain visibility, foster reader trust, and ultimately increase book sales. In essence, these services act as a bridge connecting literary talent with an eager audience, guiding readers toward their next literary adventure and facilitating authors’ journeys towards literary excellence.

The Process of Book Review Writing Services

Understanding how book review writing services operate is crucial to appreciate the effort and expertise that goes into crafting thoughtful and insightful reviews. This section delves into the step-by-step process that these services follow, from the initial service request to the final delivery of the review.

The process typically begins when an author or publisher submits a service request to a book review writing service. Depending on the platform or service provider, the submission may involve filling out a form, providing essential details about the book, the preferred review format, and any specific requirements or deadlines.

Once the request is received, the service provider assesses the book’s genre, target audience, and compatibility with their pool of reviewers. Based on these factors, the book is assigned to a suitable reviewer with expertise in the relevant genre or subject matter. This step is crucial to ensure that the reviewer possesses the necessary knowledge and background to provide a comprehensive evaluation.

One of the hallmarks of reputable book review writing services is the caliber of their reviewers. These professionals often have backgrounds in literature, creative writing, or related fields, and some may be published authors or industry experts themselves. Their experience and knowledge contribute to the credibility and value of the reviews they produce.

The assigned reviewer embarks on reading the book attentively, taking notes on various aspects such as plot development, character arcs, writing style, and thematic elements. During this process, they aim to grasp the author’s intentions, assess the work’s coherence, and identify its unique strengths and weaknesses.

In conclusion, book review writing services play a pivotal role in the modern literary landscape by offering authors, publishers, and self-published writers a professional and unbiased evaluation of their works. These services follow a structured process, engaging qualified reviewers to provide insightful and well-crafted reviews. By facilitating transparent communication, ensuring objectivity, and upholding ethical standards, these services bridge the gap between writers and readers, fostering credibility, visibility, and literary excellence in an increasingly competitive market.

Recent Articles

Binding special editions: limited edition case bound books, a guide to building your book collection, middle-earth: exploring j.r.r tolkien’s fictional universe in lotr, the enduring joy of rereading books, beyond the prestige: why do some readers find booker prize winners boring, related posts:, gambling as metaphor: fate, risk, and the allure of chance in literature, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Stay on Top - Get the daily news in your inbox

Subscribe to our newsletter.

To be updated with all the latest news, offers and special announcements.

Recent Posts

The ideal entrepreneur by rahul agarwal, on writing – a memoir of the craft by stephen king, risky business in rising china by mark atkeson, 1942: when british rule in india was threatened by krishna kumar, popular category.

- Book Review 625

- Reader's Corner 407

- Author's Corner 179

- Author Interview 173

- Book List 111

- Mystery Thriller 95

- Historical Fiction 80

The Bookish Elf is your single, trusted, daily source for all the news, ideas and richness of literary life. The Bookish Elf is a site you can rely on for book reviews, author interviews, book recommendations, and all things books.

Contact us: [email protected]

American Author House: The Final Revival of Opal & Nev

American Author House: Philip Roth: The Biography

American Author House: The Hill We Climb: An Inaugural Poem for the Country

American Author House: The Midnight Library: A Novel

American Author House: Win

American Author House: The Hate U Give

American Author House: The Lost Apothecary: A Novel

American Author House: Good Company: A Novel

- Let's Get Started

- Book Writing

- Ghost Writing

- Autobiography & Memoir

- Ebook Writing

- Article Writing/Publication

- Book Editing

- Book Publishing

- Book Video Trailer

- Author Website

- Book Marketing

- Book Cover Design

- Custom Book Illustration

- Professional Audio Book

How to Write A Book Review: Definition, Structure, Examples

- July 2, 2023

Table of Contents:

Understanding the purpose of a book review, telling possible readers, providing constructive feedback, building a community of readers, increasing visibility, the structure of a book review, introduction, summary of the book, critical analysis, style of writing, plot and structure, messages and main ideas, difference and effect, examples and supporting evidence, examples of well-written book reviews, example 1: non-fiction book review, example 2: fiction book review, to kill a mockingbird by harper lee, essential elements, strategy and detailed insights.

Every writer must know to write a book review. It is an important skill for people who love to read and want to become writers. Not only does it help writers, but it also helps other users choose what to read.

It’s important to know why you write a book review before you get started on the actual process of doing so. A book review is important for many reasons, such as:

A well-written review summarizes the book, its main ideas, and what the reader should take from it. This helps potential readers decide if they want to read the book.

Reviews help writers figure out what worked and what didn’t in their book by telling them what worked and what didn’t. Helpful critiques can help writers improve their writing skills and improve their next works.

Book reviews help readers talk about what they’ve read, which builds a sense of community and shared experiences. American Author House help people talk about books and see them from different points of view.

Good reviews can greatly affect how well-known and sold a book is. They change how online sites work and help get the author’s work in front of more people.

Now that we know how important book reviews are, let’s look at how they are put together and what they should include.

The opening should immediately grab the reader’s attention and set the stage for your review. Most of the time, writing a book review has the following parts:

- Information about the book: Give the title, author’s name, release date, and subject as your first information. This helps people know which book you are talking about.

- Hook: Engage your readers with a catchy line that shows what the book is about or what makes it special. This could be a question that makes you think, an interesting quote, or a short story.

- Thesis Statement: Give a short and convincing summary of your feelings about the book. This gives the rest of your review a sense of direction.

Give a summary of the book’s plot, major ideas, and main characters in this part. Don’t give away details that could ruin the story for the reader. Focus on giving people a general idea of the book and how it feels.

The critical analysis is the heart of your book review, where you provide your thoughts and opinions. Think about how to write a book review. Read some of the following tips:

Evaluate the author’s writing style, including how they use words, pace, and tell a story. Talk about how well it tells the story and keeps the reader interested.

Look at how the story goes and how the book is put together. Comment on how well the story makes sense, moves along, and flows. Talk about whether the story keeps readers interested and whether the framework makes it easier to follow.

Analyze the major characters, how they change, and how they are important to the story. Talk about their good points, bad points, and general trustworthiness. Talk about the connections between the characters and how they affect the story.

Check out the book’s core ideas, messages, or social comments. Talk about how well the author handles these topics and if they make sense to the reader.

Think about how original the book is and how it affects the reader. Talk about whether the story shows something new or gives you new ideas. Then write a book review. Discuss how the book made you feel, what it taught you, and how it changed your morals.

Give specific examples and quotes from the book to back up your reasoning. These examples should back your arguments and help readers understand your view. Choose parts that are especially moving, well-written, or show how good the book is.

You can write a book review and conclude by combining your general opinion and summarizing your main points. Give a final suggestion to the people based on what you’ve learned. Use this part to leave a strong impact and get people interested in reading the rest of the book.

The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles Duhigg If you want to explore more examples of well-written book reviews and gain inspiration, you can check out our article on The Pros and Cons of Self-Publishing on Amazon .

In The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg explores the science behind habits and their impact on our lives. Using real-life examples and engaging anecdotes, Duhigg provides a fascinating look into how habits are formed, how they can be changed, and their influence on personal and professional success.

Duhigg’s writing style is informative and engaging, making complex concepts accessible to many readers. His meticulous research is evident throughout the book, as he presents compelling case studies and scientific findings to support his claims. The book’s structure seamlessly guides readers through exploring habit formation, change, and its applications in various domains.

By dissecting the underlying psychology of habits, Duhigg sheds light on the power of routine and the potential for personal transformation. The book offers actionable insights and practical strategies to help readers harness the power of habits in their own lives.

The Power of Habit is a must-read for anyone interested in understanding the influence of habits on personal and professional development. Duhigg’s compelling storytelling and evidence-based approach make this book a valuable resource for individuals seeking to make positive life changes.

Summary: To Kill a Mockingbird is a classic novel set in the racially-charged atmosphere of the 1930s Deep South. Harper Lee’s timeless masterpiece explores themes of racial inequality, justice, and the loss of innocence through the eyes of Scout Finch, a young girl growing up in the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama.

Lee’s evocative writing transports readers to a bygone era, vividly depicting the social complexities and prejudices of the time. Through Scout’s innocent perspective, the reader witnesses the profound impact of racism and intolerance on the community. The memorable characters, such as Atticus Finch and Boo Radley, are flawlessly developed, each contributing to the overarching narrative with depth and nuance.

The novel’s exploration of moral courage, empathy, and the pursuit of justice resonates as powerfully today as it did upon its publication. Lee’s ability to tackle sensitive subjects with sensitivity and authenticity sets To Kill a Mockingbird apart as a timeless work of literature.

Conclusion:

To Kill a Mockingbird is a literary masterpiece that confronts the complexities of racial injustice with grace and insight. Harper Lee’s remarkable storytelling and profound themes. If you’re interested in exploring more classic literature and book reviews, you can find valuable insights in our article about Fantastic Fiction: Discovering the Best Fantasy and Sci-Fi Books .

limited Time offer

50% off on all services.

REDEEM YOUR COUPON: AAH50

Recommended Blogs

9 Top Technical Writing Certifications in 2024

How to Instagram Background Change the Color of the Instagram Story

Which technology was originally predicted by a science fiction writer, let's have a conversation to streamline your book writing and publishing we offer a comprehensive, fully managed book writing and publishing service designed to help you save valuable time., 50% off on all services redeem your coupon: aah50.

Discuss your app idea with our consultants today

How to Write a Book Review: A Comprehensive Tutorial With Examples

You don’t need to be a literary expert to craft captivating book reviews. With one in every three readers selecting books based on insightful reviews, your opinions can guide fellow bibliophiles toward their next literary adventure.

Learning how to write a book review will not only help you excel at your assigned tasks, but you’ll also contribute valuable insights to the book-loving community and turn your passion into a professional pursuit.

In this comprehensive guide, PaperPerk will walk you through a few simple steps to master the art of writing book reviews so you can confidently embark on this rewarding journey.

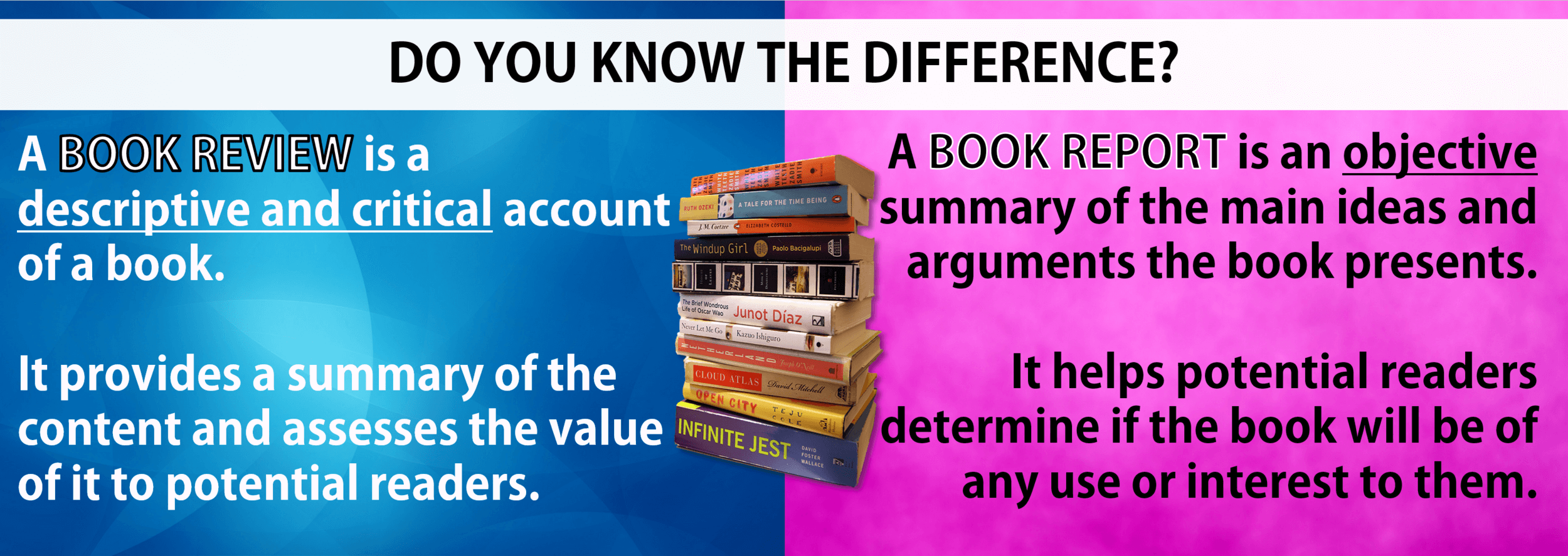

What is a Book Review?

A book review is a critical evaluation of a book, offering insights into its content, quality, and impact. It helps readers make informed decisions about whether to read the book.

Writing a book review as an assignment benefits students in multiple ways. Firstly, it teaches them how to write a book review by developing their analytical skills as they evaluate the content, themes, and writing style .

Secondly, it enhances their ability to express opinions and provide constructive criticism. Additionally, book review assignments expose students to various publications and genres, broadening their knowledge.

Furthermore, these tasks foster essential skills for academic success, like critical thinking and the ability to synthesize information. By now, we’re sure you want to learn how to write a book review, so let’s look at the book review template first.

Table of Contents

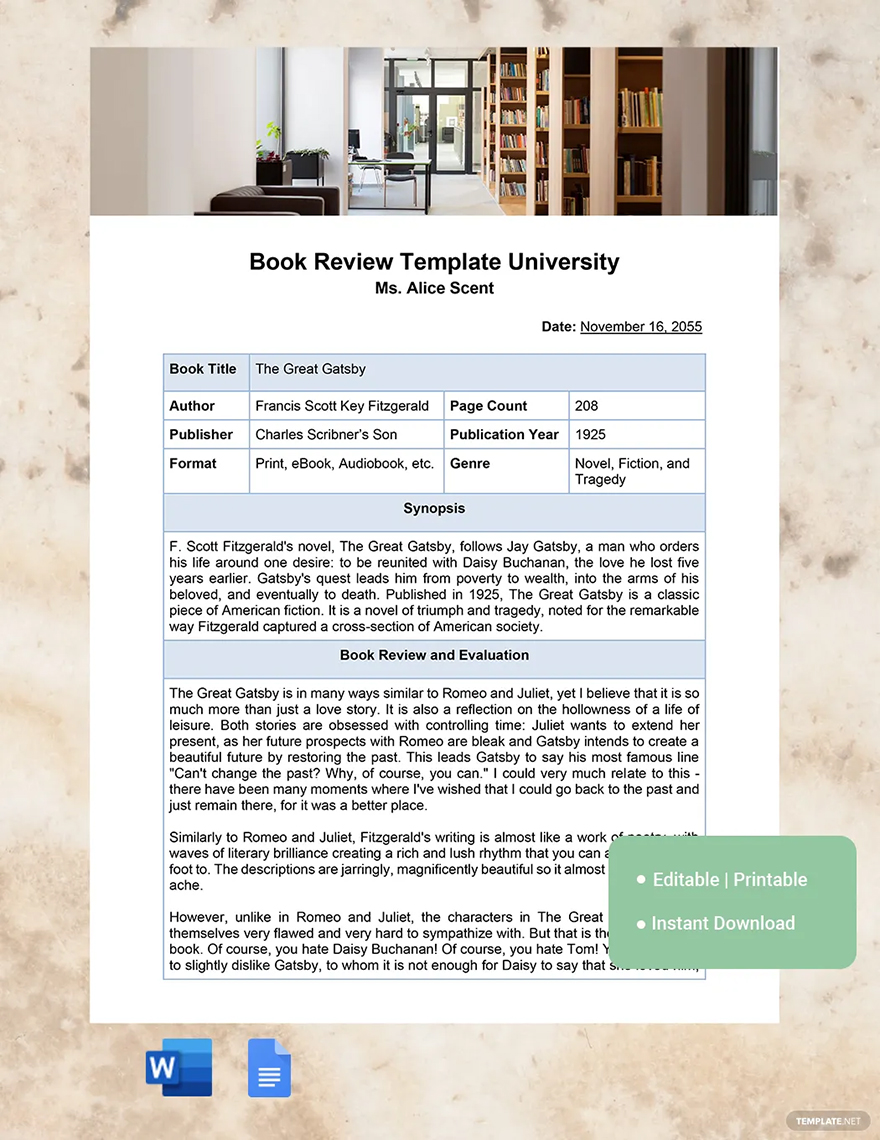

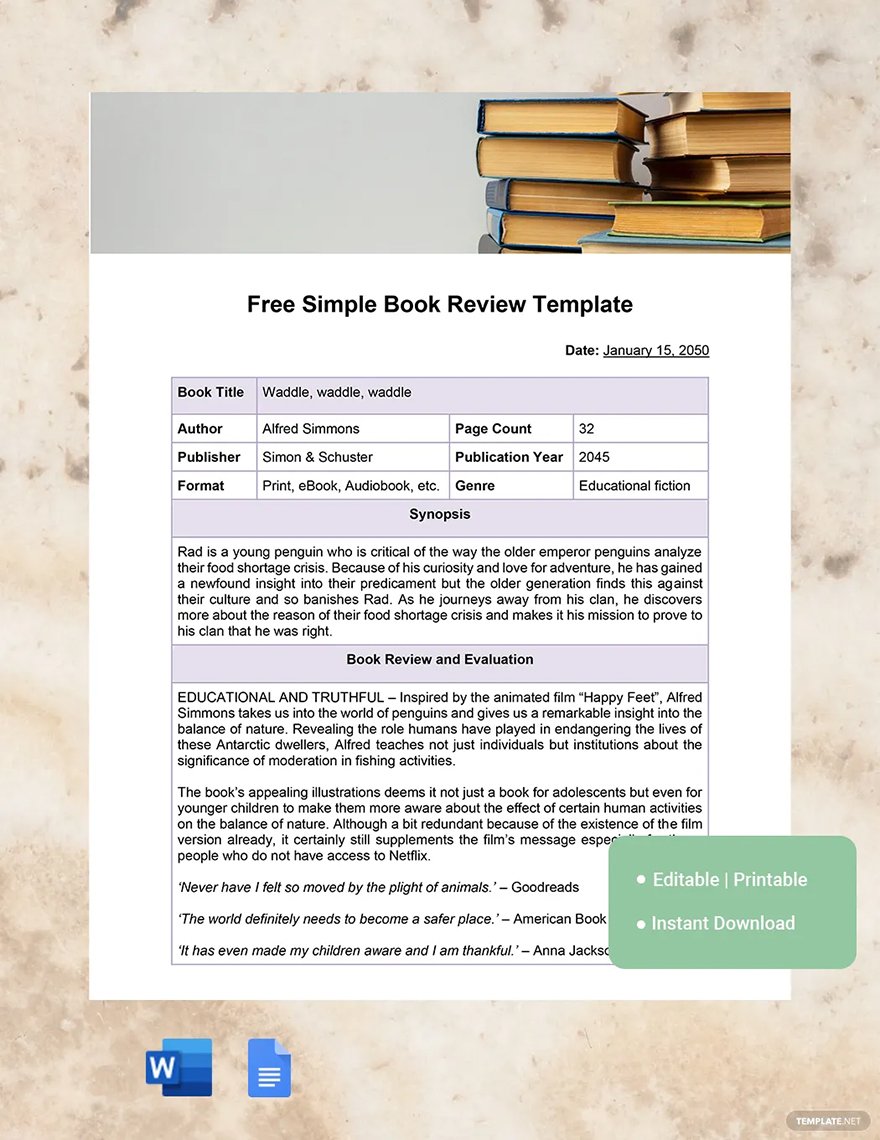

Book Review Template

How to write a book review- a step by step guide.

Check out these 5 straightforward steps for composing the best book review.

Step 1: Planning Your Book Review – The Art of Getting Started

You’ve decided to take the plunge and share your thoughts on a book that has captivated (or perhaps disappointed) you. Before you start book reviewing, let’s take a step back and plan your approach. Since knowing how to write a book review that’s both informative and engaging is an art in itself.

Choosing Your Literature

First things first, pick the book you want to review. This might seem like a no-brainer, but selecting a book that genuinely interests you will make the review process more enjoyable and your insights more authentic.

Crafting the Master Plan

Next, create an outline that covers all the essential points you want to discuss in your review. This will serve as the roadmap for your writing journey.

The Devil is in the Details

As you read, note any information that stands out, whether it overwhelms, underwhelms, or simply intrigues you. Pay attention to:

- The characters and their development

- The plot and its intricacies

- Any themes, symbols, or motifs you find noteworthy

Remember to reserve a body paragraph for each point you want to discuss.

The Key Questions to Ponder

When planning your book review, consider the following questions:

- What’s the plot (if any)? Understanding the driving force behind the book will help you craft a more effective review.

- Is the plot interesting? Did the book hold your attention and keep you turning the pages?

- Are the writing techniques effective? Does the author’s style captivate you, making you want to read (or reread) the text?

- Are the characters or the information believable? Do the characters/plot/information feel real, and can you relate to them?

- Would you recommend the book to anyone? Consider if the book is worthy of being recommended, whether to impress someone or to support a point in a literature class.

- What could improve? Always keep an eye out for areas that could be improved. Providing constructive criticism can enhance the quality of literature.

Step 2 – Crafting the Perfect Introduction to Write a Book Review

In this second step of “how to write a book review,” we’re focusing on the art of creating a powerful opening that will hook your audience and set the stage for your analysis.

Identify Your Book and Author

Begin by mentioning the book you’ve chosen, including its title and the author’s name. This informs your readers and establishes the subject of your review.

Ponder the Title

Next, discuss the mental images or emotions the book’s title evokes in your mind . This helps your readers understand your initial feelings and expectations before diving into the book.

Judge the Book by Its Cover (Just a Little)

Take a moment to talk about the book’s cover. Did it intrigue you? Did it hint at what to expect from the story or the author’s writing style? Sharing your thoughts on the cover can offer a unique perspective on how the book presents itself to potential readers.

Present Your Thesis

Now it’s time to introduce your thesis. This statement should be a concise and insightful summary of your opinion of the book. For example:

“Normal People” by Sally Rooney is a captivating portrayal of the complexities of human relationships, exploring themes of love, class, and self-discovery with exceptional depth and authenticity.

Ensure that your thesis is relevant to the points or quotes you plan to discuss throughout your review.

Incorporating these elements into your introduction will create a strong foundation for your book review. Your readers will be eager to learn more about your thoughts and insights on the book, setting the stage for a compelling and thought-provoking analysis.

How to Write a Book Review: Step 3 – Building Brilliant Body Paragraphs

You’ve planned your review and written an attention-grabbing introduction. Now it’s time for the main event: crafting the body paragraphs of your book review. In this step of “how to write a book review,” we’ll explore the art of constructing engaging and insightful body paragraphs that will keep your readers hooked.

Summarize Without Spoilers

Begin by summarizing a specific section of the book, not revealing any major plot twists or spoilers. Your goal is to give your readers a taste of the story without ruining surprises.

Support Your Viewpoint with Quotes

Next, choose three quotes from the book that support your viewpoint or opinion. These quotes should be relevant to the section you’re summarizing and help illustrate your thoughts on the book.

Analyze the Quotes

Write a summary of each quote in your own words, explaining how it made you feel or what it led you to think about the book or the author’s writing. This analysis should provide insight into your perspective and demonstrate your understanding of the text.

Structure Your Body Paragraphs

Dedicate one body paragraph to each quote, ensuring your writing is well-connected, coherent, and easy to understand.

For example:

- In Jane Eyre , Charlotte Brontë writes, “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me.” This powerful statement highlights Jane’s fierce independence and refusal to be trapped by societal expectations.

- In Normal People , Sally Rooney explores the complexities of love and friendship when she writes, “It was culture as class performance, literature fetishized for its ability to take educated people on false emotional journeys.” This quote reveals the author’s astute observations on the role of culture and class in shaping personal relationships.

- In Wuthering Heights , Emily Brontë captures the tumultuous nature of love with the quote, “He’s more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same.” This poignant line emphasizes the deep, unbreakable bond between the story’s central characters.

By following these guidelines, you’ll create body paragraphs that are both captivating and insightful, enhancing your book review and providing your readers with a deeper understanding of the literary work.

How to Write a Book Review: Step 4 – Crafting a Captivating Conclusion

You’ve navigated through planning, introductions, and body paragraphs with finesse. Now it’s time to wrap up your book review with a conclusion that leaves a lasting impression . In this final step of “how to write a book review,” we’ll explore the art of writing a memorable and persuasive conclusion.

Summarize Your Analysis

Begin by summarizing the key points you’ve presented in the body paragraphs. This helps to remind your readers of the insights and arguments you’ve shared throughout your review.

Offer Your Final Conclusion

Next, provide a conclusion that reflects your overall feelings about the book. This is your chance to leave a lasting impression and persuade your readers to consider your perspective.

Address the Book’s Appeal

Now, answer the question: Is this book worth reading? Be clear about who would enjoy the book and who might not. Discuss the taste preferences and circumstances that make the book more appealing to some readers than others.

For example: The Alchemist is a book that can enchant a young teen, but those who are already well-versed in classic literature might find it less engaging.

Be Subtle and Balanced

Avoid simply stating whether you “liked” or “disliked” the book. Instead, use nuanced language to convey your message. Highlight the pros and cons of reading the type of literature you’ve reviewed, offering a balanced perspective.

Bringing It All Together

By following these guidelines, you’ll craft a conclusion that leaves your readers with a clear understanding of your thoughts and opinions on the book. Your review will be a valuable resource for those considering whether to pick up the book, and your witty and insightful analysis will make your review a pleasure to read. So conquer the world of book reviews, one captivating conclusion at a time!

How to Write a Book Review: Step 5 – Rating the Book (Optional)

You’ve masterfully crafted your book review, from the introduction to the conclusion. But wait, there’s one more step you might consider before calling it a day: rating the book. In this optional step of “how to write a book review,” we’ll explore the benefits and methods of assigning a rating to the book you’ve reviewed.

Why Rate the Book?

Sometimes, when writing a professional book review, it may not be appropriate to state whether you liked or disliked the book. In such cases, assigning a rating can be an effective way to get your message across without explicitly sharing your personal opinion.

How to Rate the Book

There are various rating systems you can use to evaluate the book, such as:

- A star rating (e.g., 1 to 5 stars)

- A numerical score (e.g., 1 to 10)

- A letter grade (e.g., A+ to F)

Choose a rating system that best suits your style and the format of your review. Be consistent in your rating criteria, considering writing quality, character development, plot, and overall enjoyment.

Tips for Rating the Book

Here are some tips for rating the book effectively:

- Be honest: Your rating should reflect your true feelings about the book. Don’t inflate or deflate your rating based on external factors, such as the book’s popularity or the author’s reputation.

- Be fair:Consider the book’s merits and shortcomings when rating. Even if you didn’t enjoy the book, recognize its strengths and acknowledge them in your rating.

- Be clear: Explain the rationale behind your rating so your readers understand the factors that influenced your evaluation.

Wrapping Up

By including a rating in your book review, you provide your readers with an additional insight into your thoughts on the book. While this step is optional, it can be a valuable tool for conveying your message subtly yet effectively. So, rate those books confidently, adding a touch of wit and wisdom to your book reviews.

Additional Tips on How to Write a Book Review: A Guide

In this segment, we’ll explore additional tips on how to write a book review. Get ready to captivate your readers and make your review a memorable one!

Hook ’em with an Intriguing Introduction

Keep your introduction precise and to the point. Readers have the attention span of a goldfish these days, so don’t let them swim away in boredom. Start with a bang and keep them hooked!

Embrace the World of Fiction

When learning how to write a book review, remember that reviewing fiction is often more engaging and effective. If your professor hasn’t assigned you a specific book, dive into the realm of fiction and select a novel that piques your interest.

Opinionated with Gusto

Don’t shy away from adding your own opinion to your review. A good book review always features the writer’s viewpoint and constructive criticism. After all, your readers want to know what you think!

Express Your Love (or Lack Thereof)

If you adored the book, let your readers know! Use phrases like “I’ll definitely return to this book again” to convey your enthusiasm. Conversely, be honest but respectful even if the book wasn’t your cup of tea.

Templates and Examples and Expert Help: Your Trusty Sidekicks

Feeling lost? You can always get help from formats, book review examples or online college paper writing service platforms. These trusty sidekicks will help you navigate the world of book reviews with ease.

Be a Champion for New Writers and Literature

Remember to uplift new writers and pieces of literature. If you want to suggest improvements, do so kindly and constructively. There’s no need to be mean about anyone’s books – we’re all in this literary adventure together!

Criticize with Clarity, Not Cruelty

When adding criticism to your review, be clear but not mean. Remember, there’s a fine line between constructive criticism and cruelty. Tread lightly and keep your reader’s feelings in mind.

Avoid the Comparison Trap

Resist the urge to compare one writer’s book with another. Every book holds its worth, and comparing them will only confuse your reader. Stick to discussing the book at hand, and let it shine in its own light.

Top 7 Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Writing a book review can be a delightful and rewarding experience, especially when you balance analysis, wit, and personal insights. However, some common mistakes can kill the brilliance of your review.

In this section of “how to write a book review,” we’ll explore the top 7 blunders writers commit and how to steer clear of them, with a dash of modernist literature examples and tips for students writing book reviews as assignments.

Succumbing to the Lure of Plot Summaries

Mistake: Diving headfirst into a plot summary instead of dissecting the book’s themes, characters, and writing style.

Example: “The Bell Jar chronicles the life of a young woman who experiences a mental breakdown.”

How to Avoid: Delve into the book’s deeper aspects, such as its portrayal of mental health, societal expectations, and the author’s distinctive narrative voice. Offer thoughtful insights and reflections, making your review a treasure trove of analysis.

Unleashing the Spoiler Kraken

Mistake: Spilling major plot twists or the ending without providing a spoiler warning, effectively ruining the reading experience for potential readers.

Example: “In Metamorphosis, the protagonist’s transformation into a monstrous insect leads to…”

How to Avoid: Tread carefully when discussing significant plot developments, and consider using spoiler warnings. Focus on the impact of these plot points on the overall narrative, character growth, or thematic resonance.

Riding the Personal Bias Express

Mistake: Allowing personal bias to hijack the review without providing sufficient evidence or reasoning to support opinions.

Example: “I detest books about existential crises, so The Sun Also Rises was a snoozefest.”

How to Avoid: While personal opinions are valid, it’s crucial to back them up with specific examples from the book. Discuss aspects like writing style, character development, or pacing to support your evaluation and provide a more balanced perspective.

Wielding the Vague Language Saber

Mistake: Resorting to generic, vague language that fails to capture the nuances of the book and can come across as clichéd.

Example: “This book was mind-blowing. It’s a must-read for everyone.”

How to Avoid: Use precise and descriptive language to express your thoughts. Employ specific examples and quotations to highlight memorable scenes, the author’s unique writing style, or the impact of the book’s themes on readers.

Ignoring the Contextualization Compass

Mistake: Neglecting to provide context about the author, genre, or cultural relevance of the book, leaving readers without a proper frame of reference.

Example: “This book is dull and unoriginal.”

How to Avoid: Offer readers a broader understanding by discussing the author’s background, the genre conventions the book adheres to or subverts, and any societal or historical contexts that inform the narrative. This helps readers appreciate the book’s uniqueness and relevance.

Overindulging in Personal Preferences

Mistake: Letting personal preferences overshadow an objective assessment of the book’s merits.

Example: “I don’t like stream-of-consciousness writing, so this book is automatically bad.”

How to Avoid: Acknowledge personal preferences but strive to evaluate the book objectively. Focus on the book’s strengths and weaknesses, considering how well it achieves its goals within its genre or intended audience.

Forgetting the Target Audience Telescope

Mistake: Failing to mention the book’s target audience or who might enjoy it, leading to confusion for potential readers.

Example: “This book is great for everyone.”

How to Avoid: Contemplate the book’s intended audience, genre, and themes. Mention who might particularly enjoy the book based on these factors, whether it’s fans of a specific genre, readers interested in character-driven stories, or those seeking thought-provoking narratives.

By dodging these common pitfalls, writers can craft insightful, balanced, and engaging book reviews that help readers make informed decisions about their reading choices.

These tips are particularly beneficial for students writing book reviews as assignments, as they ensure a well-rounded and thoughtful analysis.!

Many students requested us to cover how to write a book review. This thorough guide is sure to help you. At Paperperk, professionals are dedicated to helping students find their balance. We understand the importance of good grades, so we offer the finest writing service , ensuring students stay ahead of the curve. So seek expert help because only Paperperk is your perfect solution!

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Calculate Your Order Price

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

How to Write a Book Review: Awesome Guide

A book review allows students to illustrate the author's intentions of writing the piece, as well as create a criticism of the book — as a whole. In other words, form an opinion of the author's presented ideas. Check out this guide from EssayPro — book review writing service to learn how to write a book review successfully.

What Is a Book Review?

You may prosper, “what is a book review?”. Book reviews are commonly assigned students to allow them to show a clear understanding of the novel. And to check if the students have actually read the book. The essay format is highly important for your consideration, take a look at the book review format below.

Book reviews are assigned to allow students to present their own opinion regarding the author’s ideas included in the book or passage. They are a form of literary criticism that analyzes the author’s ideas, writing techniques, and quality. A book analysis is entirely opinion-based, in relevance to the book. They are good practice for those who wish to become editors, due to the fact, editing requires a lot of criticism.

Book Review Template

The book review format includes an introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Introduction

- Describe the book cover and title.

- Include any subtitles at this stage.

- Include the Author’s Name.

- Write a brief description of the novel.

- Briefly introduce the main points of the body in your book review.

- Avoid mentioning any opinions at this time.

- Use about 3 quotations from the author’s novel.

- Summarize the quotations in your own words.

- Mention your own point-of-view of the quotation.

- Remember to keep every point included in its own paragraph.

- In brief, summarize the quotations.

- In brief, summarize the explanations.

- Finish with a concluding sentence.

- This can include your final opinion of the book.

- Star-Rating (Optional).

Get Your BOOK REVIEW WRITTEN!

Simply send us your paper requirements, choose a writer and we’ll get it done.

How to Write a Book Review: Step-By-Step

Writing a book review is something that can be done with every novel. Book reviews can apply to all novels, no matter the genre. Some genres may be harder than others. On the other hand, the book review format remains the same. Take a look at these step-by-step instructions from our professional writers to learn how to write a book review in-depth.

Step 1: Planning

Create an essay outline which includes all of the main points you wish to summarise in your book analysis. Include information about the characters, details of the plot, and some other important parts of your chosen novel. Reserve a body paragraph for each point you wish to talk about.

Consider these points before writing:

- What is the plot of the book? Understanding the plot enables you to write an effective review.

- Is the plot gripping? Does the plot make you want to continue reading the novel? Did you enjoy the plot? Does it manage to grab a reader’s attention?

- Are the writing techniques used by the author effective? Does the writer imply factors in-between the lines? What are they?

- Are the characters believable? Are the characters logical? Does the book make the characters are real while reading?

- Would you recommend the book to anyone? The most important thing: would you tell others to read this book? Is it good enough? Is it bad?

- What could be better? Keep in mind the quotes that could have been presented better. Criticize the writer.

Step 2: Introduction

Presumably, you have chosen your book. To begin, mention the book title and author’s name. Talk about the cover of the book. Write a thesis statement regarding the fictitious story or non-fictional novel. Which briefly describes the quoted material in the book review.

Step 3: Body

Choose a specific chapter or scenario to summarise. Include about 3 quotes in the body. Create summaries of each quote in your own words. It is also encouraged to include your own point-of-view and the way you interpret the quote. It is highly important to have one quote per paragraph.

Step 4: Conclusion

Write a summary of the summarised quotations and explanations, included in the body paragraphs. After doing so, finish book analysis with a concluding sentence to show the bigger picture of the book. Think to yourself, “Is it worth reading?”, and answer the question in black and white. However, write in-between the lines. Avoid stating “I like/dislike this book.”

Step 5: Rate the Book (Optional)

After writing a book review, you may want to include a rating. Including a star-rating provides further insight into the quality of the book, to your readers. Book reviews with star-ratings can be more effective, compared to those which don’t. Though, this is entirely optional.

Count on the support of our cheap essay writing service . We process all your requests fast.

Dive into literary analysis with EssayPro . Our experts can help you craft insightful book reviews that delve deep into the themes, characters, and narratives of your chosen books. Enhance your understanding and appreciation of literature with us.

Writing Tips

Here is the list of tips for the book review:

- A long introduction can certainly lower one’s grade: keep the beginning short. Readers don’t like to read the long introduction for any essay style.

- It is advisable to write book reviews about fiction: it is not a must. Though, reviewing fiction can be far more effective than writing about a piece of nonfiction

- Avoid Comparing: avoid comparing your chosen novel with other books you have previously read. Doing so can be confusing for the reader.

- Opinion Matters: including your own point-of-view is something that is often encouraged when writing book reviews.

- Refer to Templates: a book review template can help a student get a clearer understanding of the required writing style.

- Don’t be Afraid to Criticize: usually, your own opinion isn’t required for academic papers below Ph.D. level. On the other hand, for book reviews, there’s an exception.

- Use Positivity: include a fair amount of positive comments and criticism.

- Review The Chosen Novel: avoid making things up. Review only what is presented in the chosen book.

- Enjoyed the book? If you loved reading the book, state it. Doing so makes your book analysis more personalized.

Writing a book review is something worth thinking about. Professors commonly assign this form of an assignment to students to enable them to express a grasp of a novel. Following the book review format is highly useful for beginners, as well as reading step-by-step instructions. Writing tips is also useful for people who are new to this essay type. If you need a book review or essay, ask our book report writing services ' write paper for me ' and we'll give you a hand asap!

We also recommend that everyone read the article about essay topics . It will help broaden your horizons in writing a book review as well as other papers.

Book Review Examples

Referring to a book review example is highly useful to those who wish to get a clearer understanding of how to review a book. Take a look at our examples written by our professional writers. Click on the button to open the book review examples and feel free to use them as a reference.

Book review

Kenneth Grahame’s ‘The Wind in the Willows’

Kenneth Grahame’s ‘The Wind in the Willows’ is a novel aimed at youngsters. The plot, itself, is not American humor, but that of Great Britain. In terms of sarcasm, and British-related jokes. The novel illustrates a fair mix of the relationships between the human-like animals, and wildlife. The narrative acts as an important milestone in post-Victorian children’s literature.

Book Review

Dr. John’s ‘Pollution’

Dr. John’s ‘Pollution’ consists of 3 major parts. The first part is all about the polluted ocean. The second being about the pollution of the sky. The third part is an in-depth study of how humans can resolve these issues. The book is a piece of non-fiction that focuses on modern-day pollution ordeals faced by both animals and humans on Planet Earth. It also focuses on climate change, being the result of the global pollution ordeal.

We can do your coursework writing for you if you still find it difficult to write it yourself. Send to our custom term paper writing service your requirements, choose a writer and enjoy your time.

Need To Write a Book Review But DON’T HAVE THE TIME

We’re here to do it for you. Our professionals are ready to help 24/7

Related Articles

.webp)

How to Write a Book Review: The Complete Guide

by Sue Weems | 23 comments

If you've ever loved (or hated) a book, you may have been tempted to review it. Here's a complete guide to how to write a book review, so you can share your literary adventures with other readers more often!

You finally reach the last page of a book that kept you up all night and close it with the afterglow of satisfaction and a tinge of regret that it’s over. If you enjoyed the book enough to stay up reading it way past your bedtime, consider writing a review. It is one of the best gifts you can give an author.

Regardless of how much you know about how to write a book review, the author will appreciate hearing how their words touched you.

But as you face the five shaded stars and empty box, a blank mind strikes. What do I say? I mean, is this a book really deserving of five stars? How did it compare to Dostoevsky or Angelou or Dickens?

Maybe there’s an easier way to write a book review.

Want to learn how to write a book from start to finish? Check out How to Write a Book: The Complete Guide .

The Fallacy of Book Reviews

Once you’ve decided to give a review, you are faced with the task of deciding how many stars to give a book.

When I first started writing book reviews, I made the mistake of trying to compare a book to ALL BOOKS OF ALL TIME. (Sorry for the all caps, but that’s how it felt, like a James Earl Jones voice was asking me where to put this book in the queue of all books.)

Other readers find themselves comparing new titles to their favorite books. It's a natural comparison. But is it fair?

This is honestly why I didn’t give reviews of books for a long time. How can I compare a modern romance or historical fiction war novel with Dostoevsky? I can’t, and I shouldn’t.

I realized my mistake one day as I was watching (of all things) a dog show. In the final round, they trotted out dogs of all shapes, colors, and sizes. I thought, “How can a Yorkshire Terrier compete with a Basset Hound?” As if he'd read my mind, the announcer explained that each is judged by the standards for its breed.

This was my “Aha!” moment. I have to take a book on its own terms. The question is not, “How does this book compare to all books I’ve read?” but “How well did this book deliver what it promised for the intended audience?”

A review is going to reflect my personal experience with the book, but I can help potential readers by taking a minute to consider what the author intended. Let me explain what I mean.

How to Write a Book Review: Consider a Book’s Promise

A book makes a promise with its cover, blurb, and first pages. It begins to set expectations the minute a reader views the thumbnail or cover. Those things indicate the genre, tone, and likely the major themes.

If a book cover includes a lip-locked couple in flowing linen on a beach, and I open to the first page to read about a pimpled vampire in a trench coat speaking like Mr. Knightly about his plan for revenge on the entire human race, there’s been a breach of contract before I even get to page two. These are the books we put down immediately (unless a mixed-message beachy cover combined with an Austen vampire story is your thing).

But what if the cover, blurb, and first pages are cohesive and perk our interest enough to keep reading? Then we have to think about what the book has promised us, which revolves around one key idea: What is the core story question and how well is it resolved?

Sometimes genre expectations help us answer this question: a romance will end with a couple who finds their way, a murder mystery ends with a solved case, a thriller’s protagonist beats the clock and saves the country or planet.

The stories we love most do those expected things in a fresh or surprising way with characters we root for from the first page. Even (and especially!) when a book doesn’t fit neatly in a genre category, we need to consider what the book promises on those first pages and decide how well it succeeds on the terms it sets for itself.

When I Don’t Know What to Write

About a month ago, I realized I was overthinking how to write a book review. Here at the Write Practice we have a longstanding tradition of giving critiques using the Oreo method : point out something that was a strength, then something we wondered about or that confused us, followed by another positive.

We can use this same structure to write a simple review when we finish books. Consider this book review format:

[Book Title] by [book author] is about ___[plot summary in a sentence—no spoilers!]___. I chose this book based on ________. I really enjoyed ________. I wondered how ___________. Anyone who likes ____ will love this book.

Following this basic template can help you write an honest review about most any book, and it will give the author or publisher good information about what worked (and possibly what didn’t). You might write about the characters, the conflict, the setting, or anything else that captured you and kept you reading.

As an added bonus, you will be a stronger reader when you are able to express why you enjoyed parts of a book (just like when you critique!). After you complete a few, you’ll find it gets easier, and you won’t need the template anymore.

What if I Didn’t Like It?

Like professional book reviewers, you will have to make the call about when to leave a negative review. If I can’t give a book at least three stars, I usually don’t review it. Why? If I don’t like a book after a couple chapters, I put it down. I don’t review anything that I haven’t read the entire book.

Also, it may be that I’m not the target audience. The book might be well-written and well-reviewed with a great cover, and it just doesn’t capture me. Or maybe it's a book that just isn't hitting me right now for reasons that have nothing to do with the book and everything to do with my own reading life and needs. Every book is not meant for every reader.

If a book kept me reading all the way to the end and I didn’t like the ending? I would probably still review it, since there had to be enough good things going on to keep me reading to the end. I might mention in my review that the ending was less satisfying than I hoped, but I would still end with a positive.

How to Write a Book Review: Your Turn

As writers, we know how difficult it is to put down the words day after day. We are typically voracious readers. Let’s send some love back out to our fellow writers this week and review the most recent title we enjoyed.

What was the last book you read or reviewed? Do you ever find it hard to review a book? Share in the comments .

Now it's your turn. Think of the last book you read. Then, take fifteen minutes to write a review of it based on the template above. When you're done, share your review in the Pro Practice Workshop . For bonus points, post it on the book's page on Amazon and Goodreads, too!

Don't forget to leave feedback for your fellow writers! What new reads will you discover in the comments?

Sue Weems is a writer, teacher, and traveler with an advanced degree in (mostly fictional) revenge. When she’s not rationalizing her love for parentheses (and dramatic asides), she follows a sailor around the globe with their four children, two dogs, and an impossibly tall stack of books to read. You can read more of her writing tips on her website .

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A book review is a thorough description, critical analysis, and/or evaluation of the quality, meaning, and significance of a book, often written in relation to prior research on the topic. Reviews generally range from 500-2000 words, but may be longer or shorter depends on several factors: the length and complexity of the book being reviewed, the overall purpose of the review, and whether the review examines two or more books that focus on the same topic. Professors assign book reviews as practice in carefully analyzing complex scholarly texts and to assess your ability to effectively synthesize research so that you reach an informed perspective about the topic being covered.

There are two general approaches to reviewing a book:

- Descriptive review: Presents the content and structure of a book as objectively as possible, describing essential information about a book's purpose and authority. This is done by stating the perceived aims and purposes of the study, often incorporating passages quoted from the text that highlight key elements of the work. Additionally, there may be some indication of the reading level and anticipated audience.

- Critical review: Describes and evaluates the book in relation to accepted literary and historical standards and supports this evaluation with evidence from the text and, in most cases, in contrast to and in comparison with the research of others. It should include a statement about what the author has tried to do, evaluates how well you believe the author has succeeded in meeting the objectives of the study, and presents evidence to support this assessment. For most course assignments, your professor will want you to write this type of review.

Book Reviews. Writing Center. University of New Hampshire; Book Reviews: How to Write a Book Review. Writing and Style Guides. Libraries. Dalhousie University; Kindle, Peter A. "Teaching Students to Write Book Reviews." Contemporary Rural Social Work 7 (2015): 135-141; Erwin, R. W. “Reviewing Books for Scholarly Journals.” In Writing and Publishing for Academic Authors . Joseph M. Moxley and Todd Taylor. 2 nd edition. (Lanham, MD: Rowan and Littlefield, 1997), pp. 83-90.

How to Approach Writing Your Review

NOTE: Since most course assignments require that you write a critical rather than descriptive book review, the following information about preparing to write and developing the structure and style of reviews focuses on this approach.

I. Common Features

While book reviews vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features. These include:

- A review gives the reader a concise summary of the content . This includes a description of the research topic and scope of analysis as well as an overview of the book's overall perspective, argument, and purpose.

- A review offers a critical assessment of the content in relation to other studies on the same topic . This involves documenting your reactions to the work under review--what strikes you as noteworthy or important, whether or not the arguments made by the author(s) were effective or persuasive, and how the work enhanced your understanding of the research problem under investigation.

- In addition to analyzing a book's strengths and weaknesses, a scholarly review often recommends whether or not readers would value the work for its authenticity and overall quality . This measure of quality includes both the author's ideas and arguments and covers practical issues, such as, readability and language, organization and layout, indexing, and, if needed, the use of non-textual elements .

To maintain your focus, always keep in mind that most assignments ask you to discuss a book's treatment of its topic, not the topic itself . Your key sentences should say, "This book shows...,” "The study demonstrates...," or “The author argues...," rather than "This happened...” or “This is the case....”

II. Developing a Critical Assessment Strategy

There is no definitive methodological approach to writing a book review in the social sciences, although it is necessary that you think critically about the research problem under investigation before you begin to write. Therefore, writing a book review is a three-step process: 1) carefully taking notes as you read the text; 2) developing an argument about the value of the work under consideration; and, 3) clearly articulating that argument as you write an organized and well-supported assessment of the work.

A useful strategy in preparing to write a review is to list a set of questions that should be answered as you read the book [remember to note the page numbers so you can refer back to the text!]. The specific questions to ask yourself will depend upon the type of book you are reviewing. For example, a book that is presenting original research about a topic may require a different set of questions to ask yourself than a work where the author is offering a personal critique of an existing policy or issue.

Here are some sample questions that can help you think critically about the book:

- Thesis or Argument . What is the central thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one main idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world that you know or have experienced? What has the book accomplished? Is the argument clearly stated and does the research support this?

- Topic . What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Is it clearly articulated? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? Can you detect any biases? What type of approach has the author adopted to explore the research problem [e.g., topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive]?

- Evidence . How does the author support their argument? What evidence does the author use to prove their point? Is the evidence based on an appropriate application of the method chosen to gather information? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author's information [or conclusions] conflict with other books you've read, courses you've taken, or just previous assumptions you had about the research problem?

- Structure . How does the author structure their argument? Does it follow a logical order of analysis? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense to you? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- Take-aways . How has this book helped you understand the research problem? Would you recommend the book to others? Why or why not?

Beyond the content of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the general presentation of information. Question to ask may include:

- The Author: Who is the author? The nationality, political persuasion, education, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the author is affiliated with a particular organization? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they wrote about? What other topics has the author written about? Does this work build on prior research or does it represent a new or unique area of research?

- The Presentation: What is the book's genre? Out of what discipline does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or other contextual standard upon which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know this. Keep in mind, though, that declarative statements about being the “first,” the "best," or the "only" book of its kind can be a risky unless you're absolutely certain because your professor [presumably] has a much better understanding of the overall research literature.

NOTE: Most critical book reviews examine a topic in relation to prior research. A good strategy for identifying this prior research is to examine sources the author(s) cited in the chapters introducing the research problem and, of course, any review of the literature. However, you should not assume that the author's references to prior research is authoritative or complete. If any works related to the topic have been excluded, your assessment of the book should note this . Be sure to consult with a librarian to ensure that any additional studies are located beyond what has been cited by the author(s).

Book Reviews. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Book Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Hartley, James. "Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (July 2006): 1194–1207; Motta-Roth, D. “Discourse Analysis and Academic Book Reviews: A Study of Text and Disciplinary Cultures.” In Genre Studies in English for Academic Purposes . Fortanet Gómez, Inmaculada et al., editors. (Castellò de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, 1998), pp. 29-45. Writing a Book Review. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Book Reviews. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Suárez, Lorena and Ana I. Moreno. “The Rhetorical Structure of Academic Journal Book Reviews: A Cross-linguistic and Cross-disciplinary Approach .” In Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, María del Carmen Pérez Llantada Auría, Ramón Plo Alastrué, and Claus Peter Neumann. Actas del V Congreso Internacional AELFE/Proceedings of the 5th International AELFE Conference . Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza, 2006.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Bibliographic Information

Bibliographic information refers to the essential elements of a work if you were to cite it in a paper [i.e., author, title, date of publication, etc.]. Provide the essential information about the book using the writing style [e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago] preferred by your professor or used by the discipline of your major . Depending on how your professor wants you to organize your review, the bibliographic information represents the heading of your review. In general, it would look like this:

[Complete title of book. Author or authors. Place of publication. Publisher. Date of publication. Number of pages before first chapter, often in Roman numerals. Total number of pages]. The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party's Revolution and the Battle over American History . By Jill Lepore. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. xii, 207 pp.)

Reviewed by [your full name].

II. Scope/Purpose/Content

Begin your review by telling the reader not only the overarching concern of the book in its entirety [the subject area] but also what the author's particular point of view is on that subject [the thesis statement]. If you cannot find an adequate statement in the author's own words or if you find that the thesis statement is not well-developed, then you will have to compose your own introductory thesis statement that does cover all the material. This statement should be no more than one paragraph and must be succinctly stated, accurate, and unbiased.

If you find it difficult to discern the overall aims and objectives of the book [and, be sure to point this out in your review if you determine that this is a deficiency], you may arrive at an understanding of the book's overall purpose by assessing the following:

- Scan the table of contents because it can help you understand how the book was organized and will aid in determining the author's main ideas and how they were developed [e.g., chronologically, topically, historically, etc.].

- Why did the author write on this subject rather than on some other subject?

- From what point of view is the work written?

- Was the author trying to give information, to explain something technical, or to convince the reader of a belief’s validity by dramatizing it in action?

- What is the general field or genre, and how does the book fit into it? If necessary, review related literature from other books and journal articles to familiarize yourself with the field.

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author's style? Is it formal or informal? You can evaluate the quality of the writing style by noting some of the following standards: coherence, clarity, originality, forcefulness, accurate use of technical words, conciseness, fullness of development, and fluidity [i.e., quality of the narrative flow].

- How did the book affect you? Were there any prior assumptions you had about the subject that were changed, abandoned, or reinforced after reading the book? How is the book related to your own personal beliefs or assumptions? What personal experiences have you had related to the subject that affirm or challenge underlying assumptions?

- How well has the book achieved the goal(s) set forth in the preface, introduction, and/or foreword?

- Would you recommend this book to others? Why or why not?

III. Note the Method

Support your remarks with specific references to text and quotations that help to illustrate the literary method used to state the research problem, describe the research design, and analyze the findings. In general, authors tend to use the following literary methods, exclusively or in combination.

- Description : The author depicts scenes and events by giving specific details that appeal to the five senses, or to the reader’s imagination. The description presents background and setting. Its primary purpose is to help the reader realize, through as many details as possible, the way persons, places, and things are situated within the phenomenon being described.

- Narration : The author tells the story of a series of events, usually thematically or in chronological order. In general, the emphasis in scholarly books is on narration of the events. Narration tells what has happened and, in some cases, using this method to forecast what could happen in the future. Its primary purpose is to draw the reader into a story and create a contextual framework for understanding the research problem.

- Exposition : The author uses explanation and analysis to present a subject or to clarify an idea. Exposition presents the facts about a subject or an issue clearly and as impartially as possible. Its primary purpose is to describe and explain, to document for the historical record an event or phenomenon.

- Argument : The author uses techniques of persuasion to establish understanding of a particular truth, often in the form of addressing a research question, or to convince the reader of its falsity. The overall aim is to persuade the reader to believe something and perhaps to act on that belief. Argument takes sides on an issue and aims to convince the reader that the author's position is valid, logical, and/or reasonable.

IV. Critically Evaluate the Contents

Critical comments should form the bulk of your book review . State whether or not you feel the author's treatment of the subject matter is appropriate for the intended audience. Ask yourself:

- Has the purpose of the book been achieved?

- What contributions does the book make to the field?

- Is the treatment of the subject matter objective or at least balanced in describing all sides of a debate?

- Are there facts and evidence that have been omitted?

- What kinds of data, if any, are used to support the author's thesis statement?

- Can the same data be interpreted to explain alternate outcomes?

- Is the writing style clear and effective?

- Does the book raise important or provocative issues or topics for discussion?

- Does the book bring attention to the need for further research?

- What has been left out?

Support your evaluation with evidence from the text and, when possible, state the book's quality in relation to other scholarly sources. If relevant, note of the book's format, such as, layout, binding, typography, etc. Are there tables, charts, maps, illustrations, text boxes, photographs, or other non-textual elements? Do they aid in understanding the text? Describing this is particularly important in books that contain a lot of non-textual elements.

NOTE: It is important to carefully distinguish your views from those of the author so as not to confuse your reader. Be clear when you are describing an author's point of view versus expressing your own.

V. Examine the Front Matter and Back Matter

Front matter refers to any content before the first chapter of the book. Back matter refers to any information included after the final chapter of the book . Front matter is most often numbered separately from the rest of the text in lower case Roman numerals [i.e. i - xi ]. Critical commentary about front or back matter is generally only necessary if you believe there is something that diminishes the overall quality of the work [e.g., the indexing is poor] or there is something that is particularly helpful in understanding the book's contents [e.g., foreword places the book in an important context].

Front matter that may be considered for evaluation when reviewing its overall quality:

- Table of contents -- is it clear? Is it detailed or general? Does it reflect the true contents of the book? Does it help in understanding a logical sequence of content?

- Author biography -- also found as back matter, the biography of author(s) can be useful in determining the authority of the writer and whether the book builds on prior research or represents new research. In scholarly reviews, noting the author's affiliation and prior publications can be a factor in helping the reader determine the overall validity of the work [i.e., are they associated with a research center devoted to studying the problem under investigation].

- Foreword -- the purpose of a foreword is to introduce the reader to the author and the content of the book, and to help establish credibility for both. A foreword may not contribute any additional information about the book's subject matter, but rather, serves as a means of validating the book's existence. In these cases, the foreword is often written by a leading scholar or expert who endorses the book's contributions to advancing research about the topic. Later editions of a book sometimes have a new foreword prepended [appearing before an older foreword, if there was one], which may be included to explain how the latest edition differs from previous editions. These are most often written by the author.

- Acknowledgements -- scholarly studies in the social sciences often take many years to write, so authors frequently acknowledge the help and support of others in getting their research published. This can be as innocuous as acknowledging the author's family or the publisher. However, an author may acknowledge prominent scholars or subject experts, staff at key research centers, people who curate important archival collections, or organizations that funded the research. In these particular cases, it may be worth noting these sources of support in your review, particularly if the funding organization is biased or its mission is to promote a particular agenda.

- Preface -- generally describes the genesis, purpose, limitations, and scope of the book and may include acknowledgments of indebtedness to people who have helped the author complete the study. Is the preface helpful in understanding the study? Does it provide an effective framework for understanding what's to follow?

- Chronology -- also may be found as back matter, a chronology is generally included to highlight key events related to the subject of the book. Do the entries contribute to the overall work? Is it detailed or very general?

- List of non-textual elements -- a book that contains numerous charts, photographs, maps, tables, etc. will often list these items after the table of contents in the order that they appear in the text. Is this useful?

Back matter that may be considered for evaluation when reviewing its overall quality:

- Afterword -- this is a short, reflective piece written by the author that takes the form of a concluding section, final commentary, or closing statement. It is worth mentioning in a review if it contributes information about the purpose of the book, gives a call to action, summarizes key recommendations or next steps, or asks the reader to consider key points made in the book.

- Appendix -- is the supplementary material in the appendix or appendices well organized? Do they relate to the contents or appear superfluous? Does it contain any essential information that would have been more appropriately integrated into the text?

- Index -- are there separate indexes for names and subjects or one integrated index. Is the indexing thorough and accurate? Are elements used, such as, bold or italic fonts to help identify specific places in the book? Does the index include "see also" references to direct you to related topics?

- Glossary of Terms -- are the definitions clearly written? Is the glossary comprehensive or are there key terms missing? Are any terms or concepts mentioned in the text not included that should have been?

- Endnotes -- examine any endnotes as you read from chapter to chapter. Do they provide important additional information? Do they clarify or extend points made in the body of the text? Should any notes have been better integrated into the text rather than separated? Do the same if the author uses footnotes.

- Bibliography/References/Further Readings -- review any bibliography, list of references to sources, and/or further readings the author may have included. What kinds of sources appear [e.g., primary or secondary, recent or old, scholarly or popular, etc.]? How does the author make use of them? Be sure to note important omissions of sources that you believe should have been utilized, including important digital resources or archival collections.

VI. Summarize and Comment

State your general conclusions briefly and succinctly. Pay particular attention to the author's concluding chapter and/or afterword. Is the summary convincing? List the principal topics, and briefly summarize the author’s ideas about these topics, main points, and conclusions. If appropriate and to help clarify your overall evaluation, use specific references to text and quotations to support your statements. If your thesis has been well argued, the conclusion should follow naturally. It can include a final assessment or simply restate your thesis. Do not introduce new information in the conclusion. If you've compared the book to any other works or used other sources in writing the review, be sure to cite them at the end of your book review in the same writing style as your bibliographic heading of the book.

Book Reviews. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Book Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Gastel, Barbara. "Special Books Section: A Strategy for Reviewing Books for Journals." BioScience 41 (October 1991): 635-637; Hartley, James. "Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (July 2006): 1194–1207; Lee, Alexander D., Bart N. Green, Claire D. Johnson, and Julie Nyquist. "How to Write a Scholarly Book Review for Publication in a Peer-reviewed Journal: A Review of the Literature." Journal of Chiropractic Education 24 (2010): 57-69; Nicolaisen, Jeppe. "The Scholarliness of Published Peer Reviews: A Bibliometric Study of Book Reviews in Selected Social Science Fields." Research Evaluation 11 (2002): 129-140;.Procter, Margaret. The Book Review or Article Critique. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Reading a Book to Review It. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Scarnecchia, David L. "Writing Book Reviews for the Journal Of Range Management and Rangelands." Rangeland Ecology and Management 57 (2004): 418-421; Simon, Linda. "The Pleasures of Book Reviewing." Journal of Scholarly Publishing 27 (1996): 240-241; Writing a Book Review. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Book Reviews. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University.

Writing Tip

Always Read the Foreword and/or the Preface

If they are included in the front matter, a good place for understanding a book's overall purpose, organization, contributions to further understanding of the research problem, and relationship to other studies is to read the preface and the foreword. The foreword may be written by someone other than the author or editor and can be a person who is famous or who has name recognition within the discipline. A foreword is often included to add credibility to the work.

The preface is usually an introductory essay written by the author or editor. It is intended to describe the book's overall purpose, arrangement, scope, and overall contributions to the literature. When reviewing the book, it can be useful to critically evaluate whether the goals set forth in the foreword and/or preface were actually achieved. At the very least, they can establish a foundation for understanding a study's scope and purpose as well as its significance in contributing new knowledge.

Distinguishing between a Foreword, a Preface, and an Introduction . Book Creation Learning Center. Greenleaf Book Group, 2019.

Locating Book Reviews

There are several databases the USC Libraries subscribes to that include the full-text or citations to book reviews. Short, descriptive reviews can also be found at book-related online sites such as Amazon , although it's not always obvious who has written them and may actually be created by the publisher. The following databases provide comprehensive access to scholarly, full-text book reviews:

- ProQuest [1983-present]

- Book Review Digest Retrospective [1905-1982]

Some Language for Evaluating Texts