Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 397 other subscribers.

Email Address

Understanding instruction words in academic essay titles

Posted in: essay-writing

Instruction or command words indicate what your tutor wants you to do in your written assignment. It's vital that you understand exactly what these instruction words mean so you can answer all parts of the essay question and provide a complete response.

Here's a list of some of the most common instruction/command words you'll see in essay questions (and examination questions as well), together with an explanation of what they mean.

Describe: Give a detailed account of…

Outline: Give the main features/general principles; don't include minor details.

Explain, account for, interpret: Describe the facts but also give causes and reasons for them. Depending on the context, these words may also suggest that you need to make the possible implications clear as well. For example: 'Explain X and its importance for Y'.

Comment on, criticise, evaluate, critically evaluate, assess: Judge the value of something. But first, analyse, describe and explain. Then go through the arguments for and against, laying out the arguments neutrally until the section where you make your judgement clear. Judgements should be backed by reasons and evidence.

Discuss, consider: The least specific of the instruction words. Decide, first of all, what the main issues are. Then follow the same procedures for Comment on, Criticise, Evaluate, Critically Evaluate and Assess.

Analyse: Break down into component parts. Examine critically or closely.

How far, how true, to what extent: These suggest there are various views on and various aspects to the subject. Outline some of them, evaluate their strengths and weaknesses, explore alternatives and then give your judgement.

Justify: Explain, with evidence, why something is the case, answering the main objections to your view as you go along.

Refute: Give evidence to prove why something is not the case.

Compare, contrast, distinguish, differentiate, relate: All require that you discuss how things are related to each other. Compare suggests you concentrate on similarities, which may lead to a stated preference, the justification of which should be made clear. These words suggest that two situations or ideas can be compared in a number of different ways, or from a variety of viewpoints. Contrast suggests you concentrate on differences.

Define: Write down the precise meaning of a word or phrase. Sometimes several co-existing definitions may be used and, possibly, evaluated.

Illustrate: Make clear and explicit; usually requires the use of carefully chosen examples.

State: Give a concise, clear explanation or account of…

Summarise: Give a concise, clear explanation or account of… presenting the main factors and excluding minor detail or examples (see also Outline).

Trace: Outline or follow the development of something from its initiation or point of origin.

Devise: Think up, work out a plan, solve a problem etc.

Apply (to): Put something to use, show how something can be used in a particular situation.

Identify: Put a name to, list something.

Indicate: Point out. This does not usually involve giving too much detail.

List: Make a list of a number of things. This usually involves simply remembering or finding out a number of things and putting them down one after the other.

Plan: Think about how something is to be done, made, organised, etc.

Report on: Describe what you have seen or done.

Review: Write a report on something.

Specify: Give the details of something.

Work out: Find a solution to a problem.

Adapted from: Coles, M. (1995), A Student’s Guide to Coursework Writing, University of Stirling, Stirling

Share this:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

So wonderful can anyone get the information

Thanks Josphat!

This is a life saver, do you have a youtube channel where you talk about all this stuff? If so I would love to know about it 🙂 Rachelle

Hi Rachelle, Thanks for your comment. We don't have a youtube channel but stay tuned for more posts and also check out the new My-skills portal (go.bath.ac.uk/My-skills) for lots more skills support. Tom

Quite helpful. I would definitely check this before my next essay.

Thank you, Dan.

Very helpful now I understand how construct my assignments and how to answer exam questions

I have understood it clearly;)

it is very useful for us to understand many instruction word and what we need to write down

There are some define of some words,and I find that there do have many common things for some words,but not all the same.Such as compare, contrast, distinguish, differentiate, relate,they all need people to compare but foucs on different ways.

Very helpful. Listed most of the words that might be misunderstood by foreign students. Now I know why my score of writing IELTS test is always 6, I even didn't get the point of what I was supposed to write!

I have already read all of this. And it gave me a brief instruction.

There are varied instruction words in essay questions. It's a good chance for me to have a overview of these main command words because I could response to requirements of questions precisely and without the risk of wandering off the topic.

When i encounter with an essay title with these instruction words above,I should understand exactly what these words mean so that i could know what my tutor would like me to do in the assignments.Also,these words may help me make an outline and read academic articles with percific purposes.

These words are accurate and appropriate. It is really helpful for me to response some assignment questions and I can know the orientation of my answers . I can also use these words to make an outline of my essay. However, in my view, for some instruction words which are confusing and hard to understand, it is better to give an example to help us understand.

It's the first time for me to recognise these instruction words , some of them are really similar with each other.

it is very helpful to my future study. it will be better to have some examples with it.

How to navigate Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools with confidence and integrity

Artificial intelligence (AI) is advancing rapidly, and new Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools like ChatGPT, Claude, Elicit, Perplexity, Bard and Bing are now easily accessible online. As university students, how can you incorporate these emerging technologies into your studies and campus...

8 ways to beat procrastination

Whether you’re writing an assignment or revising for exams, getting started can be hard. Fortunately, there’s lots you can do to turn procrastination into action.

What I learnt from a skills enrichment workshop on feedback

If your course is largely essay-based (like mine is with Politics and International Relations) you’ll understand the frustration of receiving the same feedback on your assignments – over and over and over again.

- Jump to menu

- Student Home

- Accept your offer

- How to enrol

- Student ID card

- Set up your IT

- Orientation Week

- Fees & payment

- Academic calendar

- Special consideration

- Transcripts

- The Nucleus: Student Hub

- Referencing

- Essay writing

- Learning abroad & exchange

- Professional development & UNSW Advantage

- Employability

- Financial assistance

- International students

- Equitable learning

- Postgraduate research

- Health Service

- Events & activities

- Emergencies

- Volunteering

- Clubs and societies

- Accommodation

- Health services

- Sport and gym

- Arc student organisation

- Security on campus

- Maps of campus

- Careers portal

- Change password

Glossary of Task Words

Understanding the meaning of words, especially task words, helps you to know exactly what is being asked of you. It takes you halfway towards narrowing down your material and selecting your answer.

Task words direct you and tell you how to go about answering a question. Here is a list of such words and others that you are most likely to come across frequently in your course.

Maddox, H 1967, How to Study , 2nd ed, Pan Books, London.

Marshall, L., & Rowland, F 1998, A guide to learning independently , Addison Wesley Longman, Melbourne.

Northedge, A 1997, The good study guide , Open University, Milton Keynes, UK.

Essay and assignment writing guide

- Essay writing basics

- Essay and assignment planning

- Complex assignment questions

- Glossary of task words

- Editing checklist

- Writing a critical review

- Annotated bibliography

- Reflective writing

- ^ More support

Study Hacks Workshops | All the hacks you need! 7 Feb – 10 Apr 2024

Understanding your assignment questions: A short guide

- Introduction

- Breaking down the question

Directive or task words

Task works for science based essays.

- Further reading and references

It is really important to understand the directive or task word used in your assignment.

This will indicate how you should write and what the purpose of the assignment in. The following examples show some task words and their definitions.

However, it is important to note that none of these words has a fixed meaning. The definitions given are a general guide, and interpretation of the words may vary according to the context and the discipline.

If you are unsure as the exactly what a lecturer means by a particular task word, you should ask for clarification.

Analyse : Break up into parts; investigate

Comment on : Identify and write about the main issues; give your reactions based on what you've read/ heard in lectures. Avoid just personal opinion.

Compare : Look for the similarities between two things. Show the relevance or consequences of these similarities concluding which is preferable.

Contrast : Identify the differences between two items or arguments. Show whether the differences are significant. Perhaps give reasons why one is preferable.

Criticise : Requires an answer that points out mistakes or weaknesses, and which also indicates any favourable aspects of the subject of the question. It requires a balanced answer.

Critically evaluate : Weigh arguments for and against something, assessing the strength of the evidence on both sides. Use criteria to guide your assessment of which opinions, theories, models or items are preferable.

Define : Give the exact meaning of. Where relevant, show you understand how the definition may be problematic.

Describe : To describe is to give an observational account of something and would deal with what happened, where it happened, when it happened and who was involved. Spell out the main aspects of an idea or topic or the sequence in which a series of things happened.

Discuss : Investigate or examine by argument; sift and debate; give reasons for and against; examine the implications.

Evaluate : Assess and give your judgement about the merit, importance or usefulness of something using evidence to support your argument.

Examine : Look closely into something

Explain : Offer a detailed and exact rationale behind an idea or principle, or a set of reasons for a situation or attitude. Make clear how and why something happens.

Explore : Examine thoroughly; consider from a variety of viewpoints

Illustrate : Make something clear and explicit, give examples of evidence

Justify : Give evidence that supports and argument or idea; show why a decision or conclusions were made

Outline : Give the main points/features/general principles; show the main structure and interrelations; omit details and examples

State : Give the main features briefly and clearly

Summarise : Draw out the main points only; omit details and examples

To what extent... : Consider how far something is true, or contributes to a final outcome. Consider also ways in which it is not true.

Task Words:

How to write e.g., discuss, argue etc.

Subject Matter:

What you should be writing about.

Limiting Words:

May narrow or change the focus of your answer. (Important - they stop you from including irrelevant info)

Below are some examples of questions and tips on how you might think about answering them.

Compare acute and chronic pain in terms of pathophysiology and treatment

Compare - Make sure you are comparing and not just describing the two things in isolation

Acute and chronic pain - Subject matter

In terms of pathophysiology and treatment - Important limiting phrase - focus ONLY on these things. Use them as a lens to highlight the differences between acute and chronic pain.

Tip : Assignments that ask you to compare two things can be structured in different ways. You may choose to alternate continually between the two things, making direct comparisons and organising your essay according to themes. Alternatively, you may choose to discuss one thing fully and then the next. If you choose the second approach, you must make the links and comparisons between the two things completely clear.

With reference to any particular example enzyme, outline the key structural and functional properties of its active site

With reference to any particular example enzyme - Important limiting phase - focus your answer on a specific example. Use this example to help demonstrate your understanding.

Outline - Factual description is needed. You must demonstrate your knowledge and understanding.

The key structural and functional properties of its active site - Subject matter

Tip : Assignments that ask you to outline or describe are assessing your understanding of the topic. You must express facts clearly and precisely, using examples to illuminate them.

There is no convincing evidence for the existence of life outside our solar systems

There is - Task words not so obvious this time. Try turning the title into a question: 'Is there any convincing evidence for...?'

Convincing - Important limiting word- there may be evidence but you need to assess whether or not it is convincing.

For the existence of life outside of our solar system - Subject matter

Tip : Assignment titles that are on actually a question are often simply asking 'how true is this statement?' You must present reasons it could be true and reasons it might not be, supported by evidence and recognising the complexity of the statement.

To what extent can nuclear power provide a solution to environmental issues?

Discuss - Explore the topic from different angles, in a critical way (not purely descriptive)

Nuclear power - Subject matter

Provide a solution to - Limiting phrase: discuss ways it can and ways it can't- don't be afraid to take a position based on evidence.

Environmental issues - Subject matter. Might be an idea to define/ discuss what could be meant by environmental issues? This might be important for your argument.

Tip : If an assignment is asking a direct question, make sure your essay answers it. Address it directly in the introduction, make sure each paragraph contributes something towards your response to it, and reinforce your response in your conclusion.

Discuss the issue of patient autonomy in relation to at least one case study

The issue of patient autonomy - Subject matter

In relation to at least one case study - Important limiting phrase - don't just discuss the issue of patient autonomy in general; discuss it in the context of one or more case studies. You should use the case study to illustrate all of your points about patient autonomy.

Tip : Assignments that ask you to discuss in relation to a case study, or to a placement or own experience, usually want to see a clear link between theory and practice (reality).

- << Previous: Breaking down the question

- Next: Further reading and references >>

- Last Updated: Nov 13, 2023 4:28 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bham.ac.uk/asc/understandingassignments

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that he or she will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove her point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, he or she still has to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and she already knows everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality she or he expects.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Essays: task words

Written Assignments

Explore what different task words mean and how they apply to your assignments

You'll need to understand what your assignments are asking you to do throughout your studies. Your assessments use 'task words' that explain what you need to do in your work.

Task words are the words or phrases in a brief that tell you what to do. Common examples of task words are 'discuss', 'evaluate', 'compare and contrast', and 'critically analyse'. These words are used in assessment marking criteria and will showcase how well you've answered the question.

None of these words have a fixed meaning. Your lecturers may have specific definitions for your subject or task so you should make sure you have a good idea of what these terms mean in your field. You can check this by speaking to your lecturer, checking your course handbook and reading your marking criteria carefully.

Task words and descriptions

- Account for : Similar to ‘explain’ but with a heavier focus on reasons why something is or is not the way it is.

- Analyse : This term has the widest range of meanings according to the subject. Make a justified selection of some of the essential features of an artefact, idea or issue. Examine how these relate to each other and to other ideas, in order to help better understand the topic. See ideas and problems in different ways, and provide evidence for those ways of seeing them.

- Assess : This has very different meanings in different disciplines. Measure or evaluate one or more aspect of something (for example, the effectiveness, significance or 'truth' of something). Show in detail the outcomes of these evaluations.

- Compare : Show how two or more things are similar.

- Compare and contrast : Show similarities and differences between two or more things.

- Contrast : Show how two or more things are different.

- Critically analyse : As with analysis, but questioning and testing the strength of your and others’ analyses from different perspectives. This often means using the process of analysis to make the whole essay an objective, reasoned argument for your overall case or position.

- Critically assess : As with “assess”, but emphasising your judgments made about arguments by others, and about what you are assessing from different perspectives. This often means making the whole essay a reasoned argument for your overall case, based on your judgments.

- Critically evaluate : As with 'evaluate', but showing how judgments vary from different perspectives and how some judgments are stronger than others. This often means creating an objective, reasoned argument for your overall case, based on the evaluation from different perspectives.

- Define : Present a precise meaning.

- Describe : Say what something is like. Give its relevant qualities. Depending on the nature of the task, descriptions may need to be brief or the may need to be very detailed.

- Discuss : Provide details about and evidence for or against two or more different views or ideas, often with reference to a statement in the title. Discussion often includes explaining which views or ideas seem stronger.

- Examine : Look closely at something. Think and write about the detail, and question it where appropriate.

- Explain : Give enough description or information to make something clear or easy to understand.

- Explore : Consider an idea or topic broadly, searching out related and/or particularly relevant, interesting or debatable points.

- Evaluate : Similar to “assess”, this often has more emphasis on an overall judgement of something, explaining the extent to which it is, for example, effective, useful, or true. Evaluation is therefore sometimes more subjective and contestable than some kinds of pure assessment.

- Identify : Show that you have recognised one or more key or significant piece of evidence, thing, idea, problem, fact, theory, or example.

- Illustrate : Give selected examples of something to help describe or explain it, or use diagrams or other visual aids to help describe or explain something.

- Justify : Explain the reasons, usually “good” reasons, for something being done or believed, considering different possible views and ideas.

- Outline : Provide the main points or ideas, normally without going into detail.

- Summarise : This is similar to 'outline'. State, or re-state, the most important parts of something so that it is represented 'in miniature'. It should be concise and precise.

- State : Express briefly and clearly.

Download our essay task words revision sheet

Download this page as a PDF for your essay writing revision notes.

Writing: flow and coherence

Writing clear sentences

Explore our top tips for writing clear sentences and download our help sheet.

Find an undergraduate or postgraduate degree course that suits you at Portsmouth.

Guidance and support

Find out about the guidance and support you'll get if you need a helping hand with academic life – or life in general – when you study with us at Portsmouth.

Study Toolbox: Understanding Instructional Words in Essays, Assignments & Exams

- General Study Tips

- Note Taking

- Mind Mapping

- Searching Online Databases

- Searching Business Source Complete

- Searching CINAHL Ultimate

- Searching ProQuest Central

- Searching Science Direct

- Critically Evaluating Articles

- Critically Evaluating Websites

- Using Ebook Central

- Assignment Process

- Structure of an Academic Essay

- Understanding Instructional Words in Essays, Assignments & Exams

- Essay Checklist

- Literature Review

- APA Referencing

- Studying for Exams and Tests

- Tips for taking Exams

Before you can answer a question, you need to know what it means. When you are trying to understand the question look for instructional words, words that tell you what to do. Examples of these are analyse, describe and review.

Understanding Instructional Words

This table provides a list of instructional words and explains clearly what they require you to do in your essay, assignment or exam.

- Printable copy of Understanding Instructional Words This is a printable version of the table above. It provides a list of instructional words and explains what each requires you to do in your essay, assignment, test or exam.

- << Previous: Structure of an Academic Essay

- Next: Essay Checklist >>

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://sitacnz.libguides.com/Study_Toolbox

- Study and research support

- Academic skills

Plan your writing

Interpret your assignment.

Planning how you approach your writing will make sure that you understand the task, can manage your time, and present a researched, structured and focused assignment.

Before you start writing, you need to understand what type of writing you are required to produce. For example, you might be asked to produce a report, an essay, an annotated bibliography or a literature review. This will shape how you will prepare, research and write your assignment. Take time to understand the conventions of each type of assignment and what is expected of you.

Understand instructional words

Instructional verbs in the assignment task will indicate how to plan your approach. Choose the instructional words that you have been given below to reveal what they mean.

Instructional verbs

Examine an issue in close detail and break it into its constituent parts. Look in depth at each part, consider the evidence, and show you understand the relationship between them.

Decide on the importance or usefulness of something and give reasons and evidence for your decision.

Identify similarities and differences between two or more things, problems or arguments. Draw a conclusion about which (if either) you think is preferable or more convincing.

Outline the meaning of a word, concept or theory as it is used in your discipline. In some cases it may be necessary or desirable to examine different possible, or often used, definitions.

Present factual information about something, using appropriate evidence to support your description.

Examine the arguments and the evidence to support them. Consider different sides of the issue and weigh up the implications of each argument.

Make an appraisal of the worth of something, an argument or a set of beliefs, in the light of its validity or value. This does involve making your own judgements, but they must be supported by an evidenced argument and justification.

Explain or clarify something using evidence, diagrams, figures, or case studies.

Provide adequate reasons for a decision or a conclusion by supporting it with sufficient evidence and argument; answer the main objections that are likely to be made to it.

Summarise the main features or the general principles of a subject, topic or theory.

Provide a thorough examination of a topic. You may be asked to draw your own conclusions.

To what extent

Explore and present the argument(s) for a particular topic and state the degree to which you agree with them.

Accordion 1

Sample accordion 1

Adapted from: Greetham, B. 2018. How to write better essays . 4th ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Scope and focus

Look at the assignment task to identify whether there is a specific aspect of the topic that you are being asked to focus on. For example:

- Is the topic or question limited to a certain time period, region, or group of people?

- Are you being asked to consider a particular angle (for example, political, social, economic aspects of the topic)?

If the assignment task does not include information about the scope or limitations of the topic, you should choose these yourself. Think about what key issues have been covered in your module and whether you could use any of these to produce a focused answer to the question.

If something in the assignment brief is unclear, check with your module leader as soon as possible before starting to plan your answer.

Watch this short video on how to plan and get started with your assignment.

Define your purpose and reader

The next step before writing is to clearly define the purpose of the writing and the audience.

Most formal academic writing at university is set by, and written for, an academic tutor or assessor. There should be clear criteria against which they will mark your work. Your tutor may ask you to write for different audiences such as a lay audience or your peers, so make sure you know who your intended audience is before you start writing.

Once you have a clear idea of what is required for your assignment, you can start to plan what you are going to write.

- Wigan and Leigh College

- Learning Resources

- Study Skills Guides

Help to boost your grades

- Key words in Assignment Briefs

Assignment Brief

- Researching Information

- Note Taking

- Writing Essays & Assignments

- Writing Reports

- Writing a Critique

- Writing a literature review

- Writing short answer questions

- Reflective Writing

- Designing & Analysing Questionnaires

- Oral Presentations

- Creating a Podcast

- Creating a Blog

- Fast Reading Techniques

- Time Management

- Referencing This link opens in a new window

- Further help and advice

It is important to understand what an essay question or assignment brief is asking of you. Before you start to research or write, it is worth spending time considering the wording of the question and any learning outcomes that may accompany it. Each assignment will generally have at least three learning outcomes which you must cover if you are to achieve a pass.

Breaking down an assignment question

Before you attempt to answer an assignment question, you need to make sure you understand what it is asking. This includes not only the subject matter, but also the way in which you are required to write. Different questions may ask you to discuss, outline, evaluate… and many more. The task words are a key part of the question.

- Key Words in Assignment Briefs

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Researching Information >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 11:24 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wigan-leigh.ac.uk/Boost_Your_Grades

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Types of Assignments

Cristy Bartlett and Kate Derrington

Introduction

As discussed in the previous chapter, assignments are a common method of assessment at university. You may encounter many assignments over your years of study, yet some will look quite different from others. By recognising different types of assignments and understanding the purpose of the task, you can direct your writing skills effectively to meet task requirements. This chapter draws on the skills from the previous chapter, and extends the discussion, showing you where to aim with different types of assignments.

The chapter begins by exploring the popular essay assignment, with its two common categories, analytical and argumentative essays. It then examines assignments requiring case study responses , as often encountered in fields such as health or business. This is followed by a discussion of assignments seeking a report (such as a scientific report) and reflective writing assignments, common in nursing, education and human services. The chapter concludes with an examination of annotated bibliographies and literature reviews. The chapter also has a selection of templates and examples throughout to enhance your understanding and improve the efficacy of your assignment writing skills.

Different Types of Written Assignments

At university, an essay is a common form of assessment. In the previous chapter Writing Assignments we discussed what was meant by showing academic writing in your assignments. It is important that you consider these aspects of structure, tone and language when writing an essay.

Components of an essay

Essays should use formal but reader friendly language and have a clear and logical structure. They must include research from credible academic sources such as peer reviewed journal articles and textbooks. This research should be referenced throughout your essay to support your ideas (See the chapter Working with Information ).

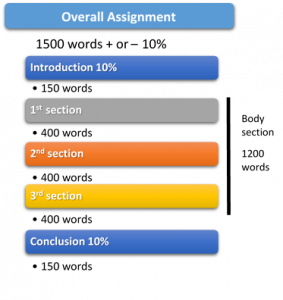

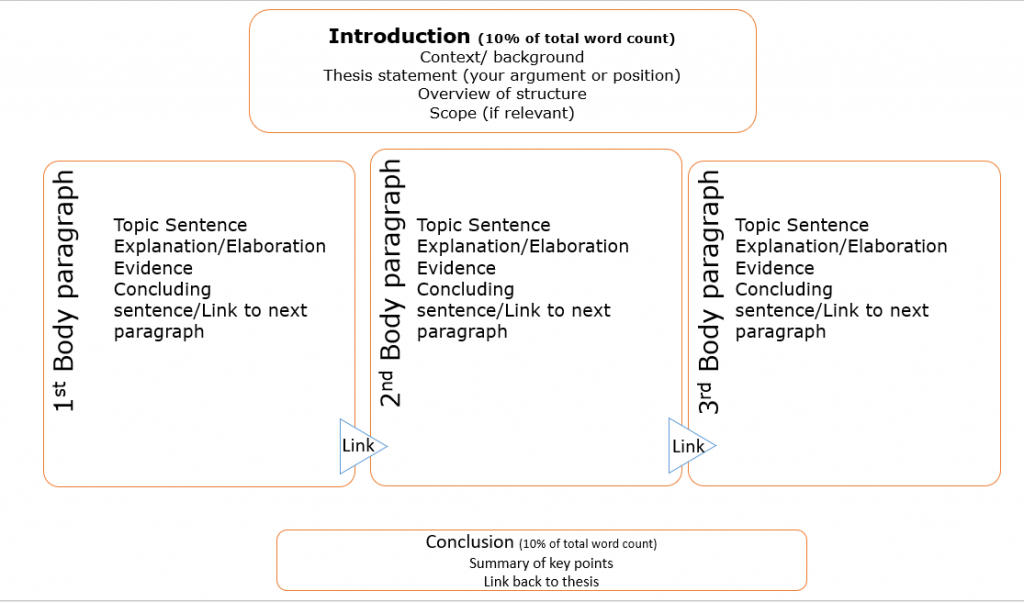

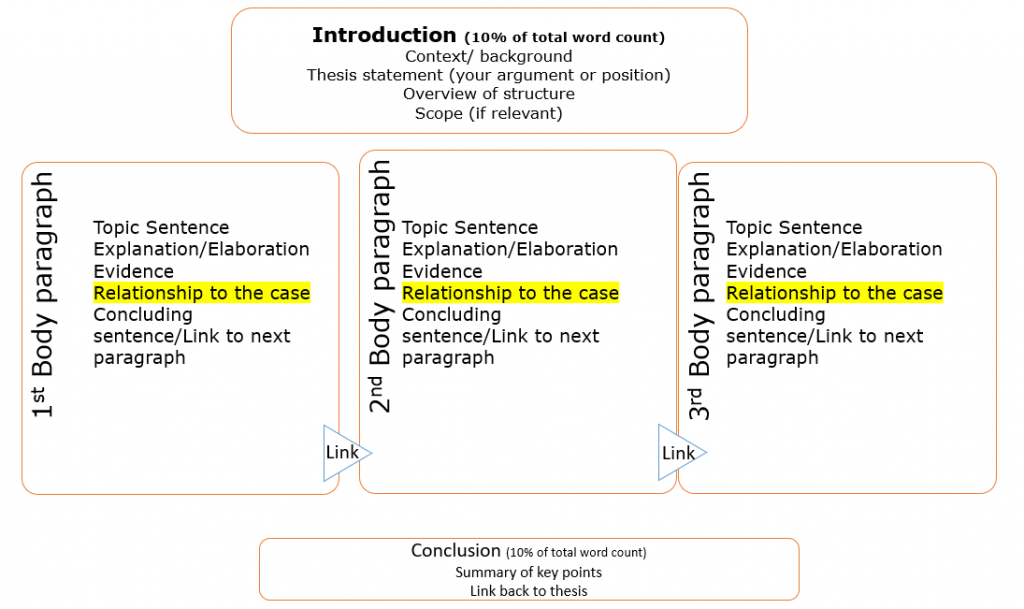

If you have never written an essay before, you may feel unsure about how to start. Breaking your essay into sections and allocating words accordingly will make this process more manageable and will make planning the overall essay structure much easier.

- An essay requires an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion.

- Generally, an introduction and conclusion are approximately 10% each of the total word count.

- The remaining words can then be divided into sections and a paragraph allowed for each area of content you need to cover.

- Use your task and criteria sheet to decide what content needs to be in your plan

An effective essay introduction needs to inform your reader by doing four basic things:

Table 20.1 An effective essay

An effective essay body paragraph needs to:

An effective essay conclusion needs to:

Common types of essays

You may be required to write different types of essays, depending on your study area and topic. Two of the most commonly used essays are analytical and argumentative . The task analysis process discussed in the previous chapter Writing Assignments will help you determine the type of essay required. For example, if your assignment question uses task words such as analyse, examine, discuss, determine or explore, you would be writing an analytical essay . If your assignment question has task words such as argue, evaluate, justify or assess, you would be writing an argumentative essay . Despite the type of essay, your ability to analyse and think critically is important and common across genres.

Analytical essays

These essays usually provide some background description of the relevant theory, situation, problem, case, image, etcetera that is your topic. Being analytical requires you to look carefully at various components or sections of your topic in a methodical and logical way to create understanding.

The purpose of the analytical essay is to demonstrate your ability to examine the topic thoroughly. This requires you to go deeper than description by considering different sides of the situation, comparing and contrasting a variety of theories and the positives and negatives of the topic. Although in an analytical essay your position on the topic may be clear, it is not necessarily a requirement that you explicitly identify this with a thesis statement, as is the case with an argumentative essay. If you are unsure whether you are required to take a position, and provide a thesis statement, it is best to check with your tutor.

Argumentative essays

These essays require you to take a position on the assignment topic. This is expressed through your thesis statement in your introduction. You must then present and develop your arguments throughout the body of your assignment using logically structured paragraphs. Each of these paragraphs needs a topic sentence that relates to the thesis statement. In an argumentative essay, you must reach a conclusion based on the evidence you have presented.

Case Study Responses

Case studies are a common form of assignment in many study areas and students can underperform in this genre for a number of key reasons.

Students typically lose marks for not:

- Relating their answer sufficiently to the case details

- Applying critical thinking

- Writing with clear structure

- Using appropriate or sufficient sources

- Using accurate referencing

When structuring your response to a case study, remember to refer to the case. Structure your paragraphs similarly to an essay paragraph structure but include examples and data from the case as additional evidence to support your points (see Figure 20.5 ). The colours in the sample paragraph below show the function of each component.

The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) Code of Conduct and Nursing Standards (2018) play a crucial role in determining the scope of practice for nurses and midwives. A key component discussed in the code is the provision of person-centred care and the formation of therapeutic relationships between nurses and patients (NMBA, 2018). This ensures patient safety and promotes health and wellbeing (NMBA, 2018). The standards also discuss the importance of partnership and shared decision-making in the delivery of care (NMBA, 2018, 4). Boyd and Dare (2014) argue that good communication skills are vital for building therapeutic relationships and trust between patients and care givers. This will help ensure the patient is treated with dignity and respect and improve their overall hospital experience. In the case, the therapeutic relationship with the client has been compromised in several ways. Firstly, the nurse did not conform adequately to the guidelines for seeking informed consent before performing the examination as outlined in principle 2.3 (NMBA, 2018). Although she explained the procedure, she failed to give the patient appropriate choices regarding her health care.

Topic sentence | Explanations using paraphrased evidence including in-text references | Critical thinking (asks the so what? question to demonstrate your student voice). | Relating the theory back to the specifics of the case. The case becomes a source of examples as extra evidence to support the points you are making.

Reports are a common form of assessment at university and are also used widely in many professions. It is a common form of writing in business, government, scientific, and technical occupations.

Reports can take many different structures. A report is normally written to present information in a structured manner, which may include explaining laboratory experiments, technical information, or a business case. Reports may be written for different audiences including clients, your manager, technical staff, or senior leadership within an organisation. The structure of reports can vary, and it is important to consider what format is required. The choice of structure will depend upon professional requirements and the ultimate aims of the report. Consider some of the options in the table below (see Table 20.2 ).

Table 20.2 Explanations of different types of reports

Reflective writing.

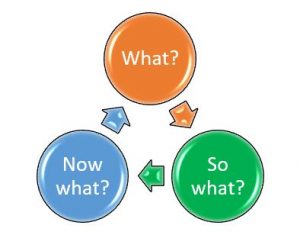

Reflective writing is a popular method of assessment at university. It is used to help you explore feelings, experiences, opinions, events or new information to gain a clearer and deeper understanding of your learning. A reflective writing task requires more than a description or summary. It requires you to analyse a situation, problem or experience, consider what you may have learnt and evaluate how this may impact your thinking and actions in the future. This requires critical thinking, analysis, and usually the application of good quality research, to demonstrate your understanding or learning from a situation. Essentially, reflective practice is the process of looking back on past experiences and engaging with them in a thoughtful way and drawing conclusions to inform future experiences. The reflection skills you develop at university will be vital in the workplace to assist you to use feedback for growth and continuous improvement. There are numerous models of reflective writing and you should refer to your subject guidelines for your expected format. If there is no specific framework, a simple model to help frame your thinking is What? So what? Now what? (Rolfe et al., 2001).

Table 20.3 What? So What? Now What? Explained.

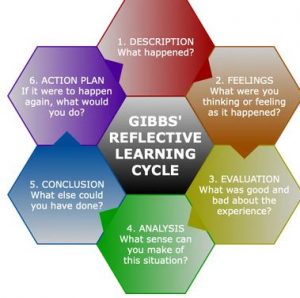

The Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

The Gibbs’ Cycle of reflection encourages you to consider your feelings as part of the reflective process. There are six specific steps to work through. Following this model carefully and being clear of the requirements of each stage, will help you focus your thinking and reflect more deeply. This model is popular in Health.

The 4 R’s of reflective thinking

This model (Ryan and Ryan, 2013) was designed specifically for university students engaged in experiential learning. Experiential learning includes any ‘real-world’ activities including practice led activities, placements and internships. Experiential learning, and the use of reflective practice to heighten this learning, is common in Creative Arts, Health and Education.

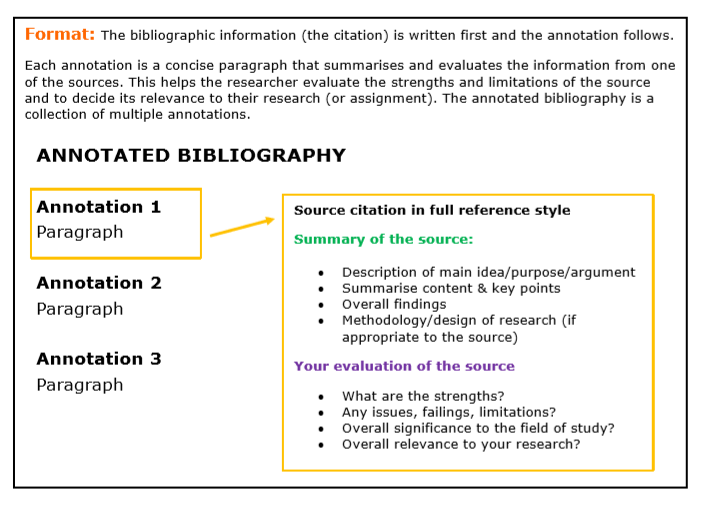

Annotated Bibliography

What is it.

An annotated bibliography is an alphabetical list of appropriate sources (books, journals or websites) on a topic, accompanied by a brief summary, evaluation and sometimes an explanation or reflection on their usefulness or relevance to your topic. Its purpose is to teach you to research carefully, evaluate sources and systematically organise your notes. An annotated bibliography may be one part of a larger assessment item or a stand-alone assessment piece. Check your task guidelines for the number of sources you are required to annotate and the word limit for each entry.

How do I know what to include?

When choosing sources for your annotated bibliography it is important to determine:

- The topic you are investigating and if there is a specific question to answer

- The type of sources on which you need to focus

- Whether they are reputable and of high quality

What do I say?

Important considerations include:

- Is the work current?

- Is the work relevant to your topic?

- Is the author credible/reliable?

- Is there any author bias?

- The strength and limitations (this may include an evaluation of research methodology).

Literature Reviews

It is easy to get confused by the terminology used for literature reviews. Some tasks may be described as a systematic literature review when actually the requirement is simpler; to review the literature on the topic but do it in a systematic way. There is a distinct difference (see Table 20.4 ). As a commencing undergraduate student, it is unlikely you would be expected to complete a systematic literature review as this is a complex and more advanced research task. It is important to check with your lecturer or tutor if you are unsure of the requirements.

Table 20.4 Comparison of Literature Reviews

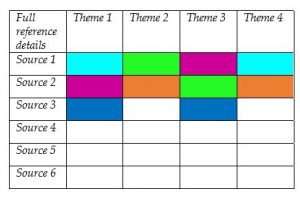

Generally, you are required to establish the main ideas that have been written on your chosen topic. You may also be expected to identify gaps in the research. A literature review does not summarise and evaluate each resource you find (this is what you would do in an annotated bibliography). You are expected to analyse and synthesise or organise common ideas from multiple texts into key themes which are relevant to your topic (see Figure 20.10 ). Use a table or a spreadsheet, if you know how, to organise the information you find. Record the full reference details of the sources as this will save you time later when compiling your reference list (see Table 20.5 ).

Overall, this chapter has provided an introduction to the types of assignments you can expect to complete at university, as well as outlined some tips and strategies with examples and templates for completing them. First, the chapter investigated essay assignments, including analytical and argumentative essays. It then examined case study assignments, followed by a discussion of the report format. Reflective writing , popular in nursing, education and human services, was also considered. Finally, the chapter briefly addressed annotated bibliographies and literature reviews. The chapter also has a selection of templates and examples throughout to enhance your understanding and improve the efficacy of your assignment writing skills.

- Not all assignments at university are the same. Understanding the requirements of different types of assignments will assist in meeting the criteria more effectively.

- There are many different types of assignments. Most will require an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion.

- An essay should have a clear and logical structure and use formal but reader friendly language.

- Breaking your assignment into manageable chunks makes it easier to approach.

- Effective body paragraphs contain a topic sentence.

- A case study structure is similar to an essay, but you must remember to provide examples from the case or scenario to demonstrate your points.

- The type of report you may be required to write will depend on its purpose and audience. A report requires structured writing and uses headings.

- Reflective writing is popular in many disciplines and is used to explore feelings, experiences, opinions or events to discover what learning or understanding has occurred. Reflective writing requires more than description. You need to be analytical, consider what has been learnt and evaluate the impact of this on future actions.

- Annotated bibliographies teach you to research and evaluate sources and systematically organise your notes. They may be part of a larger assignment.

- Literature reviews require you to look across the literature and analyse and synthesise the information you find into themes.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ryan, M. & Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development , 32(2), 244-257. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.661704

Academic Success Copyright © 2021 by Cristy Bartlett and Kate Derrington is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Justification (Typesetting and Composition)

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

SEAN GLADWELL / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In typesetting and printing, the process or result of spacing text so that the lines come out even at the margins .

The lines of text on this page are left-justified— that is, the text is lined up evenly on the left side of the page but not on the right (which is called ragged right ). As a general rule, use left justification when preparing essays, reports, and research papers.

Pronunciation: jus-te-feh-KAY-shen

Examples and Observations

" Research papers follow a standard presentation format...Do not right- justify (align) your paper. The right margins should be ragged. Your computer will automatically justify your left margin." (Laurie Rozakis, Schaum's Quick Guide to Writing Great Research Papers . McGraw-Hill, 2007)

Manuscript Guidelines (Chicago Style)

"To avoid the appearance of inconsistent spacing between words and sentences, all text in a manuscript should be presented flush left (ragged right)--that is, lines should not be 'justified' to the right margin. To leave enough room for handwritten queries, margins of at least one inch should appear on all four sides of the hard copy." ( The Chicago Manual of Style , 16th ed. The University of Chicago Press, 2010)

Full Justification

"Left- justified margins are generally easier to read than full-justified margins that can produce irregular spaces between words and unwanted blocks of text. However, because left-justified (ragged-right) margins look informal, full-justified text is more appropriate for publications aimed at a broad readership that expects a more formal, polished appearance. Further, full justification is often useful with multiple-column formats because the spaces between the columns (called alleys ) need the definition that full justification provides." (Gerald J. Alred, Charles T. Brusaw, and Walter E. Oliu, The Business Writer's Handbook , 7th ed. Macmillan, 2003)

Justification on Resumes

"Do not set full justification on an ASCII resume . Instead, left justify all lines so the right margin is ragged." (Pat Criscito, How to Write Better Résumés and Cover Letters . Barron's Educational Series, 2008)

- Margin (Composition Format) Definition

- 140 Key Copyediting Terms and What They Mean

- What Is Justification in Page Layout and Typography?

- What Is an Indentation?

- Definition and Examples of Spacing in Composition

- Forced Justification for Aligning Text

- Formatting Papers in Chicago Style

- Publishing Your Family History Book

- How to Set Justified Text With CSS

- MLA Sample Pages

- What Is a C-Fold Document?

- The Correct Usage of the HTML P and BR Elements

- Tips for Typing an Academic Paper on a Computer

- Initial letter

- How to Double Space Your Paper

- Bibliography: Definition and Examples

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of justify verb from the Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

Questions about grammar and vocabulary?

Find the answers with Practical English Usage online, your indispensable guide to problems in English.

- 3 justify something ( technology ) to arrange lines of printed text so that one or both edges are straight

Nearby words

Welcome to GoodWritingHelp.com!

- How to Write an Essay

- Justification Essay

How to Write a Good Justification Essay

A justification essay is a common assignment at high school and college. Students are supposed to learn how to persuade someone in their points of view and how to express their thoughts clearly. This job is quite difficult, so you are able to improve your justification essay writing skills with the help of our professional writing guidelines.

Step One: Research Your Topic

If you want to persuade someone in the relevance and importance of your subject, you should be able to describe it in the best way. Your primary duty is to research your topic well and collect as many useful facts about it as possible. You will have to look through several books, periodicals, articles in the Internet, etc. to accumulate enough facts and arguments about your subject. Try to note all essential ideas to avoid losing them.

Step Two: Write an Outline

One cannot complete a good justification essay if he does not plan the process of writing carefully. You should plan your essay accurately and build a sound and informative piece of writing. Your outline contains all sections of your essay, all ideas, concepts, solutions and decisions. If you write down an informative outline, you will not miss any important point. You should also think about the structure of your justification essay. It should start from an introduction, proceed with the main body and finish with a denouement.

Step Three: Prepare a Sound Introduction

A good introductory part should clarify the choice of your topic, its relevance and importance. You should write in the most understandable and precise manner if you want to attract reader’s attention and to make him accept your point of view. You are able to improve your introduction with the help of bright quotations and a brilliant thesis statement that describes the whole idea of your analysis to your audience.

Step Four: Compose the Main Body

The main body of your justification essay should contain all essential ideas and quality arguments that support your opinion about the subject. Remember that you have to justify why you think in the definite way. Teachers often assign controversial topics in order to make students take the definite side in this discussion. Your duty is to prove to your audience that your point of view is better. You are able to present arguments starting from the least important ones and proceeding with the most essential arguments.

Step Five: Make a Good Conclusion

When you summarize your justification essay, you should enumerate its key points in brief. Moreover, you are able to write the final comment on your subject in order to leave space for suggestion to your readers.

How to Write a Good:

- Research Paper

- Dissertation

- Book Report

- Book Review

- Personal Statement

- Research Proposal

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Reaction Paper

- Annotated Bibliography

- Grant Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Movie Review

- Creative Writing

- Critical Thinking

- Article Critique

- Literature Review

- Research Summary

- English Composition

- Short Story

- Poem Analysis

- Reflection Paper

- Disciplines

Essay Types

- 5-Paragraph essay

- Admission essay

- Analytical essay

- Argumentative essay

- Cause and Effect essay

- Classification essay

- Compare and Contrast essay

- Critical essay

- Deductive essay

- Definition essay

- Descriptive essay

- Discussion essay

- Exploratory essay

- Expository essay

- Informal essay

- Narrative essay

- Personal essay

- Persuasive essay

- Research essay

- Response essay

- Scholarship essay

- 5-page essay

- Process essay

- Justification essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Understanding Writing Assignments

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource describes some steps you can take to better understand the requirements of your writing assignments. This resource works for either in-class, teacher-led discussion or for personal use.

How to Decipher the Paper Assignment

Many instructors write their assignment prompts differently. By following a few steps, you can better understand the requirements for the assignment. The best way, as always, is to ask the instructor about anything confusing.

- Read the prompt the entire way through once. This gives you an overall view of what is going on.

- Underline or circle the portions that you absolutely must know. This information may include due date, research (source) requirements, page length, and format (MLA, APA, CMS).

- Underline or circle important phrases. You should know your instructor at least a little by now - what phrases do they use in class? Does he repeatedly say a specific word? If these are in the prompt, you know the instructor wants you to use them in the assignment.

- Think about how you will address the prompt. The prompt contains clues on how to write the assignment. Your instructor will often describe the ideas they want discussed either in questions, in bullet points, or in the text of the prompt. Think about each of these sentences and number them so that you can write a paragraph or section of your essay on that portion if necessary.

- Rank ideas in descending order, from most important to least important. Instructors may include more questions or talking points than you can cover in your assignment, so rank them in the order you think is more important. One area of the prompt may be more interesting to you than another.

- Ask your instructor questions if you have any.

After you are finished with these steps, ask yourself the following:

- What is the purpose of this assignment? Is my purpose to provide information without forming an argument, to construct an argument based on research, or analyze a poem and discuss its imagery?

- Who is my audience? Is my instructor my only audience? Who else might read this? Will it be posted online? What are my readers' needs and expectations?

- What resources do I need to begin work? Do I need to conduct literature (hermeneutic or historical) research, or do I need to review important literature on the topic and then conduct empirical research, such as a survey or an observation? How many sources are required?

- Who - beyond my instructor - can I contact to help me if I have questions? Do you have a writing lab or student service center that offers tutorials in writing?

(Notes on prompts made in blue )

Poster or Song Analysis: Poster or Song? Poster!

Goals : To systematically consider the rhetorical choices made in either a poster or a song. She says that all the time.

Things to Consider: ah- talking points

- how the poster addresses its audience and is affected by context I'll do this first - 1.

- general layout, use of color, contours of light and shade, etc.

- use of contrast, alignment, repetition, and proximity C.A.R.P. They say that, too. I'll do this third - 3.

- the point of view the viewer is invited to take, poses of figures in the poster, etc. any text that may be present

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing I'll cover this second - 2.

- ethical implications

- how the poster affects us emotionally, or what mood it evokes

- the poster's implicit argument and its effectiveness said that was important in class, so I'll discuss this last - 4.

- how the song addresses its audience

- lyrics: how they rhyme, repeat, what they say

- use of music, tempo, different instruments

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing

- emotional effects

- the implicit argument and its effectiveness

These thinking points are not a step-by-step guideline on how to write your paper; instead, they are various means through which you can approach the subject. I do expect to see at least a few of them addressed, and there are other aspects that may be pertinent to your choice that have not been included in these lists. You will want to find a central idea and base your argument around that. Additionally, you must include a copy of the poster or song that you are working with. Really important!

I will be your audience. This is a formal paper, and you should use academic conventions throughout.

Length: 4 pages Format: Typed, double-spaced, 10-12 point Times New Roman, 1 inch margins I need to remember the format stuff. I messed this up last time =(

Academic Argument Essay

5-7 pages, Times New Roman 12 pt. font, 1 inch margins.

Minimum of five cited sources: 3 must be from academic journals or books

- Design Plan due: Thurs. 10/19

- Rough Draft due: Monday 10/30

- Final Draft due: Thurs. 11/9

Remember this! I missed the deadline last time

The design plan is simply a statement of purpose, as described on pages 40-41 of the book, and an outline. The outline may be formal, as we discussed in class, or a printout of an Open Mind project. It must be a minimum of 1 page typed information, plus 1 page outline.

This project is an expansion of your opinion editorial. While you should avoid repeating any of your exact phrases from Project 2, you may reuse some of the same ideas. Your topic should be similar. You must use research to support your position, and you must also demonstrate a fairly thorough knowledge of any opposing position(s). 2 things to do - my position and the opposite.

Your essay should begin with an introduction that encapsulates your topic and indicates 1 the general trajectory of your argument. You need to have a discernable thesis that appears early in your paper. Your conclusion should restate the thesis in different words, 2 and then draw some additional meaningful analysis out of the developments of your argument. Think of this as a "so what" factor. What are some implications for the future, relating to your topic? What does all this (what you have argued) mean for society, or for the section of it to which your argument pertains? A good conclusion moves outside the topic in the paper and deals with a larger issue.