- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

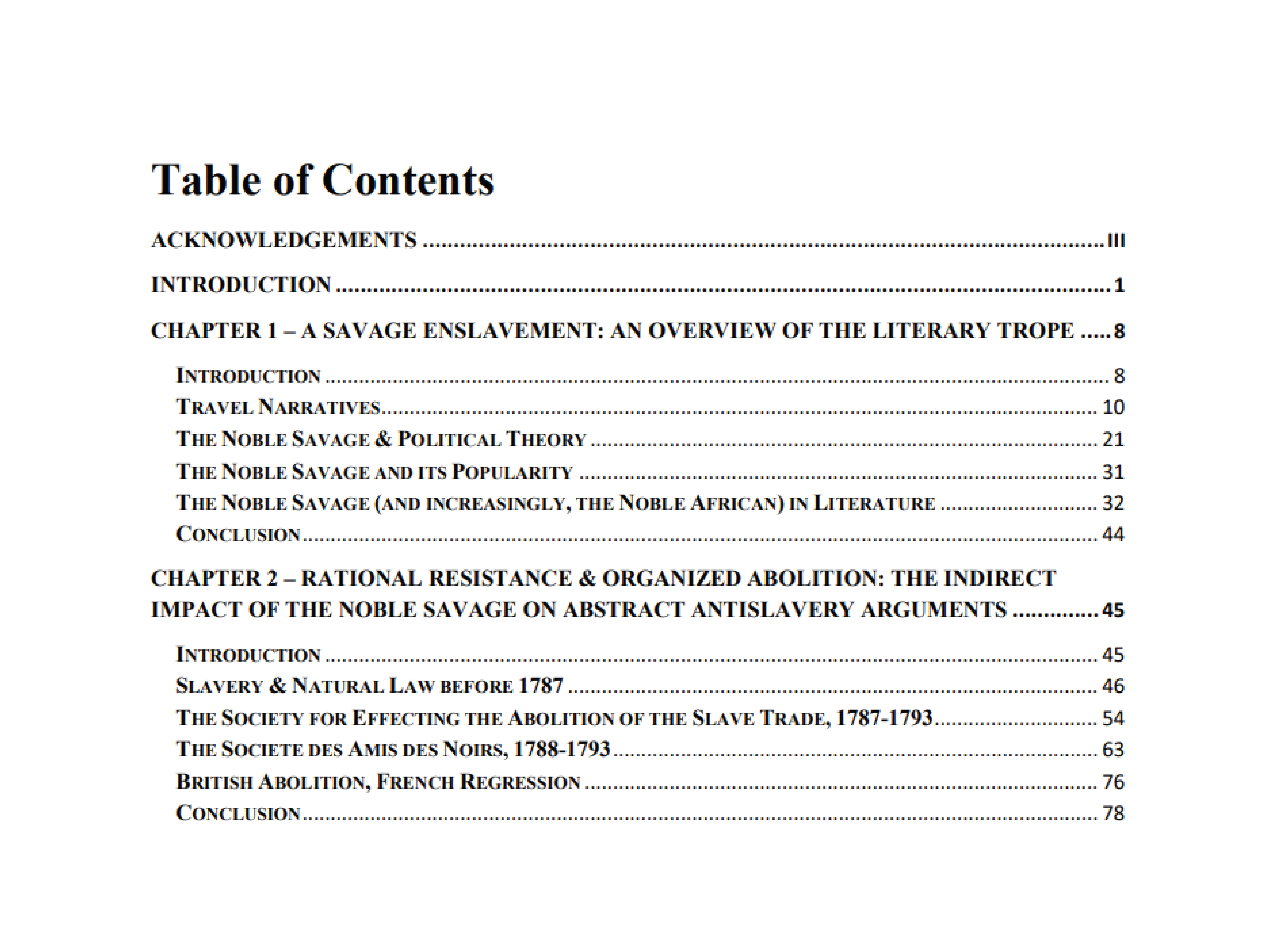

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

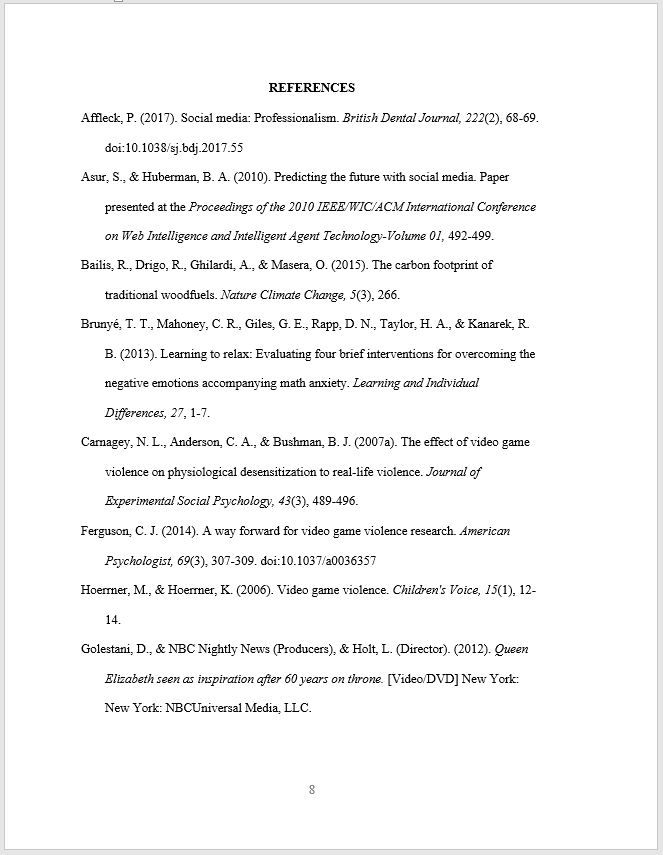

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

AI for Meta Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Table of contents.

Definition:

Thesis is a scholarly document that presents a student’s original research and findings on a particular topic or question. It is usually written as a requirement for a graduate degree program and is intended to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and their ability to conduct independent research.

History of Thesis

The concept of a thesis can be traced back to ancient Greece, where it was used as a way for students to demonstrate their knowledge of a particular subject. However, the modern form of the thesis as a scholarly document used to earn a degree is a relatively recent development.

The origin of the modern thesis can be traced back to medieval universities in Europe. During this time, students were required to present a “disputation” in which they would defend a particular thesis in front of their peers and faculty members. These disputations served as a way to demonstrate the student’s mastery of the subject matter and were often the final requirement for earning a degree.

In the 17th century, the concept of the thesis was formalized further with the creation of the modern research university. Students were now required to complete a research project and present their findings in a written document, which would serve as the basis for their degree.

The modern thesis as we know it today has evolved over time, with different disciplines and institutions adopting their own standards and formats. However, the basic elements of a thesis – original research, a clear research question, a thorough review of the literature, and a well-argued conclusion – remain the same.

Structure of Thesis

The structure of a thesis may vary slightly depending on the specific requirements of the institution, department, or field of study, but generally, it follows a specific format.

Here’s a breakdown of the structure of a thesis:

This is the first page of the thesis that includes the title of the thesis, the name of the author, the name of the institution, the department, the date, and any other relevant information required by the institution.

This is a brief summary of the thesis that provides an overview of the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

This page provides a list of all the chapters and sections in the thesis and their page numbers.

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the research question, the context of the research, and the purpose of the study. The introduction should also outline the methodology and the scope of the research.

Literature Review

This chapter provides a critical analysis of the relevant literature on the research topic. It should demonstrate the gap in the existing knowledge and justify the need for the research.

Methodology

This chapter provides a detailed description of the research methods used to gather and analyze data. It should explain the research design, the sampling method, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures.

This chapter presents the findings of the research. It should include tables, graphs, and charts to illustrate the results.

This chapter interprets the results and relates them to the research question. It should explain the significance of the findings and their implications for the research topic.

This chapter summarizes the key findings and the main conclusions of the research. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

This section provides a list of all the sources cited in the thesis. The citation style may vary depending on the requirements of the institution or the field of study.

This section includes any additional material that supports the research, such as raw data, survey questionnaires, or other relevant documents.

How to write Thesis

Here are some steps to help you write a thesis:

- Choose a Topic: The first step in writing a thesis is to choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. You should also consider the scope of the topic and the availability of resources for research.

- Develop a Research Question: Once you have chosen a topic, you need to develop a research question that you will answer in your thesis. The research question should be specific, clear, and feasible.

- Conduct a Literature Review: Before you start your research, you need to conduct a literature review to identify the existing knowledge and gaps in the field. This will help you refine your research question and develop a research methodology.

- Develop a Research Methodology: Once you have refined your research question, you need to develop a research methodology that includes the research design, data collection methods, and data analysis procedures.

- Collect and Analyze Data: After developing your research methodology, you need to collect and analyze data. This may involve conducting surveys, interviews, experiments, or analyzing existing data.

- Write the Thesis: Once you have analyzed the data, you need to write the thesis. The thesis should follow a specific structure that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, and references.

- Edit and Proofread: After completing the thesis, you need to edit and proofread it carefully. You should also have someone else review it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors.

- Submit the Thesis: Finally, you need to submit the thesis to your academic advisor or committee for review and evaluation.

Example of Thesis

Example of Thesis template for Students:

Title of Thesis

Table of Contents:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

Chapter 4: Results

Chapter 5: Discussion

Chapter 6: Conclusion

References:

Appendices:

Note: That’s just a basic template, but it should give you an idea of the structure and content that a typical thesis might include. Be sure to consult with your department or supervisor for any specific formatting requirements they may have. Good luck with your thesis!

Application of Thesis

Thesis is an important academic document that serves several purposes. Here are some of the applications of thesis:

- Academic Requirement: A thesis is a requirement for many academic programs, especially at the graduate level. It is an essential component of the evaluation process and demonstrates the student’s ability to conduct original research and contribute to the knowledge in their field.

- Career Advancement: A thesis can also help in career advancement. Employers often value candidates who have completed a thesis as it demonstrates their research skills, critical thinking abilities, and their dedication to their field of study.

- Publication : A thesis can serve as a basis for future publications in academic journals, books, or conference proceedings. It provides the researcher with an opportunity to present their research to a wider audience and contribute to the body of knowledge in their field.

- Personal Development: Writing a thesis is a challenging task that requires time, dedication, and perseverance. It provides the student with an opportunity to develop critical thinking, research, and writing skills that are essential for their personal and professional development.

- Impact on Society: The findings of a thesis can have an impact on society by addressing important issues, providing insights into complex problems, and contributing to the development of policies and practices.

Purpose of Thesis

The purpose of a thesis is to present original research findings in a clear and organized manner. It is a formal document that demonstrates a student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. The primary purposes of a thesis are:

- To Contribute to Knowledge: The main purpose of a thesis is to contribute to the knowledge in a particular field of study. By conducting original research and presenting their findings, the student adds new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- To Demonstrate Research Skills: A thesis is an opportunity for the student to demonstrate their research skills. This includes the ability to formulate a research question, design a research methodology, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- To Develop Critical Thinking: Writing a thesis requires critical thinking and analysis. The student must evaluate existing literature and identify gaps in the field, as well as develop and defend their own ideas.

- To Provide Evidence of Competence : A thesis provides evidence of the student’s competence in their field of study. It demonstrates their ability to apply theoretical concepts to real-world problems, and their ability to communicate their ideas effectively.

- To Facilitate Career Advancement : Completing a thesis can help the student advance their career by demonstrating their research skills and dedication to their field of study. It can also provide a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

When to Write Thesis

The timing for writing a thesis depends on the specific requirements of the academic program or institution. In most cases, the opportunity to write a thesis is typically offered at the graduate level, but there may be exceptions.

Generally, students should plan to write their thesis during the final year of their graduate program. This allows sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis. It is important to start planning the thesis early and to identify a research topic and research advisor as soon as possible.

In some cases, students may be able to write a thesis as part of an undergraduate program or as an independent research project outside of an academic program. In such cases, it is important to consult with faculty advisors or mentors to ensure that the research is appropriately designed and executed.

It is important to note that the process of writing a thesis can be time-consuming and requires a significant amount of effort and dedication. It is important to plan accordingly and to allocate sufficient time for conducting research, analyzing data, and writing the thesis.

Characteristics of Thesis

The characteristics of a thesis vary depending on the specific academic program or institution. However, some general characteristics of a thesis include:

- Originality : A thesis should present original research findings or insights. It should demonstrate the student’s ability to conduct independent research and contribute to the knowledge in their field of study.

- Clarity : A thesis should be clear and concise. It should present the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions in a logical and organized manner. It should also be well-written, with proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Research-Based: A thesis should be based on rigorous research, which involves collecting and analyzing data from various sources. The research should be well-designed, with appropriate research methods and techniques.

- Evidence-Based : A thesis should be based on evidence, which means that all claims made in the thesis should be supported by data or literature. The evidence should be properly cited using appropriate citation styles.

- Critical Thinking: A thesis should demonstrate the student’s ability to critically analyze and evaluate information. It should present the student’s own ideas and arguments, and engage with existing literature in the field.

- Academic Style : A thesis should adhere to the conventions of academic writing. It should be well-structured, with clear headings and subheadings, and should use appropriate academic language.

Advantages of Thesis

There are several advantages to writing a thesis, including:

- Development of Research Skills: Writing a thesis requires extensive research and analytical skills. It helps to develop the student’s research skills, including the ability to formulate research questions, design and execute research methodologies, collect and analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Contribution to Knowledge: Writing a thesis provides an opportunity for the student to contribute to the knowledge in their field of study. By conducting original research, they can add new insights and perspectives to the existing body of knowledge.

- Preparation for Future Research: Completing a thesis prepares the student for future research projects. It provides them with the necessary skills to design and execute research methodologies, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on their findings.

- Career Advancement: Writing a thesis can help to advance the student’s career. It demonstrates their research skills and dedication to their field of study, and provides a basis for future publications, presentations, or research projects.

- Personal Growth: Completing a thesis can be a challenging and rewarding experience. It requires dedication, hard work, and perseverance. It can help the student to develop self-confidence, independence, and a sense of accomplishment.

Limitations of Thesis

There are also some limitations to writing a thesis, including:

- Time and Resources: Writing a thesis requires a significant amount of time and resources. It can be a time-consuming and expensive process, as it may involve conducting original research, analyzing data, and producing a lengthy document.

- Narrow Focus: A thesis is typically focused on a specific research question or topic, which may limit the student’s exposure to other areas within their field of study.

- Limited Audience: A thesis is usually only read by a small number of people, such as the student’s thesis advisor and committee members. This limits the potential impact of the research findings.

- Lack of Real-World Application : Some thesis topics may be highly theoretical or academic in nature, which may limit their practical application in the real world.

- Pressure and Stress : Writing a thesis can be a stressful and pressure-filled experience, as it may involve meeting strict deadlines, conducting original research, and producing a high-quality document.

- Potential for Isolation: Writing a thesis can be a solitary experience, as the student may spend a significant amount of time working independently on their research and writing.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Theses and Capstone Projects: Writing your thesis or capstone project report

When a final project includes a written document of some sort, students are expected to follow the appropriate MSOE style guide. There are separate style guides for undergraduate and graduate work.

The applicable style guide can be found here:

- MSOE Graduate Student Documentation and Style Guide For Technical Documents

- MSOE Undergraduate Documentation and Style Guide

Thesis and Capstone Reports

MSOE librarians work closely with graduate students and their advisers during the thesis and capstone report phase of their education. The following resources, documents and information will help you complete your final project.

Graduate Thesis and Capstone Report Format Checks

In compliance with Graduate Programs Council (GPC) Policy 4.3.009, the library is responsible for verifying that all MSOE Graduate Thesis and Capstone Report documents comply with MSOE’s format requirements.

Graduate Thesis and Capstone Report Completion

- Graduate Thesis and Capstone Document Process This document walks through the process of completing a masters thesis or capstone document, including the library publication approval check and other considerations.

- Graduate Thesis and Capstone Publication Approval Form Complete this form and submit it to the library along with the thesis or capstone project to be reviewed.

- MSOE Electronic Thesis and Capstone Project Report Permission Form Use this Form to grant MSOE permission to electronically publish a graduate degree thesis or a graduate degree capstone project report or other independent graduate degree final report or essay.

- Library “Non-Circulation Status” Request Form Complete this from to request access restrictions for a thesis or capstone report.

Personal Thesis/Capstone Bindery Request

The library offers a bindery service for graduate students interested in having copies of their thesis or capstone report bound in a durable, sturdy, and attractive hardcover binding. Students are charged a fee per volume for the service. To request binding of a thesis or capstone report, please send an email to [email protected] .

Electronic Publications at MSOE

- Electronic Publications at MSOE A selection of theses and final capstone project reports completed by graduate students at MSOE that have been approved for electronic dissemination.

MSOE electronic publication provides the broadest possible method of disseminating your work. With electronic publication, the full text of your electronic thesis, capstone project report, or final independent report or essay is freely accessible world-wide on the Internet. Electronic publication of your document typically results in more recognition of your research work, wider dissemination of scholarly information, and acceleration of research.

The MSOE Library invites MSOE graduate students who have completed an approved master's thesis, capstone project report, or other independent final report or essay to submit their work to the MSOE Institutional Repository. In order to participate, graduate students must complete and submit a Permission Form in order to enable MSOE to electronically publish their work.

- About the Library

- List of all library guides

- Give feedback

- Print, scan, copy

- Troubleshoot digital access

- Book a study room

- Find eBooks

- Find Codes and Standards

- Find Patents

- References, Citations, and Study Guides

- Find a Journal

If you have suggestions for how to make this page better, please contact Elizabeth Jerow, Assistant Library Director ( [email protected] ).

- Last Updated: Feb 9, 2024 8:42 AM

- URL: https://libguides.msoe.edu/theses-capstone-projects

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .

A research aim is usually formulated as a broad statement of the main goal of the research and can range in length from a single sentence to a short paragraph. Although the exact format may vary according to preference, they should all describe why your research is needed (i.e. the context), what it sets out to accomplish (the actual aim) and, briefly, how it intends to accomplish it (overview of your objectives).

To give an example, we have extracted the following research aim from a real PhD thesis:

Example of a Research Aim

The role of diametrical cup deformation as a factor to unsatisfactory implant performance has not been widely reported. The aim of this thesis was to gain an understanding of the diametrical deformation behaviour of acetabular cups and shells following impaction into the reamed acetabulum. The influence of a range of factors on deformation was investigated to ascertain if cup and shell deformation may be high enough to potentially contribute to early failure and high wear rates in metal-on-metal implants.

Note: Extracted with permission from thesis titled “T he Impact And Deformation Of Press-Fit Metal Acetabular Components ” produced by Dr H Hothi of previously Queen Mary University of London.

Research Objectives

Where a research aim specifies what your study will answer, research objectives specify how your study will answer it.

They divide your research aim into several smaller parts, each of which represents a key section of your research project. As a result, almost all research objectives take the form of a numbered list, with each item usually receiving its own chapter in a dissertation or thesis.

Following the example of the research aim shared above, here are it’s real research objectives as an example:

Example of a Research Objective

- Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

- Investigate the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup.

- Determine the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types.

- Investigate the influence of non-uniform cup support and varying the orientation of the component in the cavity on deformation.

- Examine the influence of errors during reaming of the acetabulum which introduce ovality to the cavity.

- Determine the relationship between changes in the geometry of the component and deformation for different cup designs.

- Develop three dimensional pelvis models with non-uniform bone material properties from a range of patients with varying bone quality.

- Use the key parameters that influence deformation, as identified in the foam models to determine the range of deformations that may occur clinically using the anatomic models and if these deformations are clinically significant.

It’s worth noting that researchers sometimes use research questions instead of research objectives, or in other cases both. From a high-level perspective, research questions and research objectives make the same statements, but just in different formats.

Taking the first three research objectives as an example, they can be restructured into research questions as follows:

Restructuring Research Objectives as Research Questions

- Can finite element models using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum together with explicit dynamics be used to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion?

- What is the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup?

- What is the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types?

Difference Between Aims and Objectives

Hopefully the above explanations make clear the differences between aims and objectives, but to clarify:

- The research aim focus on what the research project is intended to achieve; research objectives focus on how the aim will be achieved.

- Research aims are relatively broad; research objectives are specific.

- Research aims focus on a project’s long-term outcomes; research objectives focus on its immediate, short-term outcomes.

- A research aim can be written in a single sentence or short paragraph; research objectives should be written as a numbered list.

How to Write Aims and Objectives

Before we discuss how to write a clear set of research aims and objectives, we should make it clear that there is no single way they must be written. Each researcher will approach their aims and objectives slightly differently, and often your supervisor will influence the formulation of yours on the basis of their own preferences.

Regardless, there are some basic principles that you should observe for good practice; these principles are described below.

Your aim should be made up of three parts that answer the below questions:

- Why is this research required?

- What is this research about?

- How are you going to do it?

The easiest way to achieve this would be to address each question in its own sentence, although it does not matter whether you combine them or write multiple sentences for each, the key is to address each one.

The first question, why , provides context to your research project, the second question, what , describes the aim of your research, and the last question, how , acts as an introduction to your objectives which will immediately follow.

Scroll through the image set below to see the ‘why, what and how’ associated with our research aim example.

Note: Your research aims need not be limited to one. Some individuals per to define one broad ‘overarching aim’ of a project and then adopt two or three specific research aims for their thesis or dissertation. Remember, however, that in order for your assessors to consider your research project complete, you will need to prove you have fulfilled all of the aims you set out to achieve. Therefore, while having more than one research aim is not necessarily disadvantageous, consider whether a single overarching one will do.

Research Objectives

Each of your research objectives should be SMART :

- Specific – is there any ambiguity in the action you are going to undertake, or is it focused and well-defined?

- Measurable – how will you measure progress and determine when you have achieved the action?

- Achievable – do you have the support, resources and facilities required to carry out the action?

- Relevant – is the action essential to the achievement of your research aim?

- Timebound – can you realistically complete the action in the available time alongside your other research tasks?

In addition to being SMART, your research objectives should start with a verb that helps communicate your intent. Common research verbs include:

Table of Research Verbs to Use in Aims and Objectives

Last, format your objectives into a numbered list. This is because when you write your thesis or dissertation, you will at times need to make reference to a specific research objective; structuring your research objectives in a numbered list will provide a clear way of doing this.

To bring all this together, let’s compare the first research objective in the previous example with the above guidance:

Checking Research Objective Example Against Recommended Approach

Research Objective:

1. Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

Checking Against Recommended Approach:

Q: Is it specific? A: Yes, it is clear what the student intends to do (produce a finite element model), why they intend to do it (mimic cup/shell blows) and their parameters have been well-defined ( using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum ).

Q: Is it measurable? A: Yes, it is clear that the research objective will be achieved once the finite element model is complete.

Q: Is it achievable? A: Yes, provided the student has access to a computer lab, modelling software and laboratory data.

Q: Is it relevant? A: Yes, mimicking impacts to a cup/shell is fundamental to the overall aim of understanding how they deform when impacted upon.

Q: Is it timebound? A: Yes, it is possible to create a limited-scope finite element model in a relatively short time, especially if you already have experience in modelling.

Q: Does it start with a verb? A: Yes, it starts with ‘develop’, which makes the intent of the objective immediately clear.

Q: Is it a numbered list? A: Yes, it is the first research objective in a list of eight.

Mistakes in Writing Research Aims and Objectives

1. making your research aim too broad.

Having a research aim too broad becomes very difficult to achieve. Normally, this occurs when a student develops their research aim before they have a good understanding of what they want to research. Remember that at the end of your project and during your viva defence , you will have to prove that you have achieved your research aims; if they are too broad, this will be an almost impossible task. In the early stages of your research project, your priority should be to narrow your study to a specific area. A good way to do this is to take the time to study existing literature, question their current approaches, findings and limitations, and consider whether there are any recurring gaps that could be investigated .

Note: Achieving a set of aims does not necessarily mean proving or disproving a theory or hypothesis, even if your research aim was to, but having done enough work to provide a useful and original insight into the principles that underlie your research aim.

2. Making Your Research Objectives Too Ambitious

Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time you have available. It is natural to want to set ambitious research objectives that require sophisticated data collection and analysis, but only completing this with six months before the end of your PhD registration period is not a worthwhile trade-off.

3. Formulating Repetitive Research Objectives

Each research objective should have its own purpose and distinct measurable outcome. To this effect, a common mistake is to form research objectives which have large amounts of overlap. This makes it difficult to determine when an objective is truly complete, and also presents challenges in estimating the duration of objectives when creating your project timeline. It also makes it difficult to structure your thesis into unique chapters, making it more challenging for you to write and for your audience to read.

Fortunately, this oversight can be easily avoided by using SMART objectives.

Hopefully, you now have a good idea of how to create an effective set of aims and objectives for your research project, whether it be a thesis, dissertation or research paper. While it may be tempting to dive directly into your research, spending time on getting your aims and objectives right will give your research clear direction. This won’t only reduce the likelihood of problems arising later down the line, but will also lead to a more thorough and coherent research project.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

The Thesis Process

The thesis is an opportunity to work independently on a research project of your own design and contribute to the scholarly literature in your field. You emerge from the thesis process with a solid understanding of how original research is executed and how to best communicate research results. Many students have gone on to publish their research in academic or professional journals.

To ensure affordability, the per-credit tuition rate for the 8-credit thesis is the same as our regular course tuition. There are no additional fees (regular per-credit graduate tuition x 8 credits).

Below are the steps that you need to follow to fulfill the thesis requirement. Please know that through each step, you will receive guidance and mentorship.

1. Determine Your Thesis Topic and Tentative Question

When you have completed between 24 and 32 credits, you work with your assigned research advisor to narrow down your academic interests to a relevant and manageable thesis topic. Log in to MyDCE , then ALB/ALM Community to schedule an appointment with your assigned research advisor via the Degree Candidate Portal.

Thesis Topic Selection

We’ve put together this guide to help frame your thinking about thesis topic selection.

Every effort is made to support your research interests that are grounded in your ALM course work, but faculty guidance is not available for all possible projects. Therefore, revision or a change of thesis topic may be necessary.

- The point about topic selection is particularly pertinent to scientific research that is dependent upon laboratory space, project funding, and access to private databases. It is also critical for our candidates in ALM, liberal arts fields (English, government, history, international relations, psychology, etc.) who are required to have Harvard faculty direct their thesis projects. Review Harvard’s course catalog online ( my.harvard.edu ) to be sure that there are faculty teaching courses related to your thesis topic. If not, you’ll need to choose an alternative topic.

- Your topic choice must be a new area of research for you. Thesis work represents thoughtful engagement in new academic scholarship. You cannot re-purpose prior research. If you want to draw or expand upon your own previous scholarship for a small portion of your thesis, you need to obtain the explicit permission of your research advisor and cite the work in both the proposal and thesis. Violations of this policy will be referred to the Administrative Board.

2. Prepare Prework for the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP) Course or Tutorial

The next step in the process is to prepare and submit Prework in order to gain registration approval for the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP) tutorial or course. The Prework process ensures that you have done enough prior reading and thinking about your thesis topic to benefit from the CTP.

The CTP provides an essential onramp to the thesis, mapping critical issues of research design, such as scope, relevance to the field, prior scholarly debate, methodology, and perhaps, metrics for evaluating impact as well as bench-marking. The CTP identifies and works through potential hurdles to successful thesis completion, allowing the thesis project to get off to a good start.

In addition to preparing, submitting, and having your Prework approved, to be eligible for the CTP, you need to be in good standing, have completed a minimum of 32 degree-applicable credits, including the statistics/research methods requirement (if pertinent to your field). You also need to have completed Engaging in Scholarly Conversation (if pertinent to your field). If you were admitted after 9/1/2023 Engaging in Scholarly Conversation (A and B) is required, if admitted before 9/1/2023 this series is encouraged.

Advising Note for Biology, Biotechnology, and Bioengineering and Nanotechnology Candidates : Thesis projects in these fields are designed to support ongoing scientific research happening in Harvard University, other academic institutions, or life science industry labs and usually these are done under the direction of a principal investigator (PI). Hence, you need to have a thesis director approved by your research advisor prior to submitting CTP prework. Your CTP prework is then framed by the lab’s research. Schedule an appointment with your research advisor a few months in advance of the CTP prework deadlines in order to discuss potential research projects and thesis director assignment.

CTP Prework is sent to our central email box: [email protected] between the following firm deadlines:

- April 1 and June 1 for fall CTP

- September 1 and November 1 for spring CTP.

- August 1 and October 1 for the three-week January session (ALM sustainability candidates only)

- International students who need a student visa to attend Harvard Summer School should submit their prework on January 1, so they can register for the CTP on March 1 and submit timely I-20 paperwork. See international students guidelines for more information.

Your research advisor will provide feedback on your prework submission to gain CTP registration approval. If your prework is not approved after 3 submissions, your research advisor cannot approve your CTP registration. If not approved, you’ll need to take additional time for further revisions, and submit new prework during the next CTP prework submission time period for the following term (if your five-year degree completion deadline allows).

3. Register and Successfully Complete the Crafting the Thesis Proposal Tutorial or Course

Once CTP prework is approved, you register for the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP) course or tutorial as you would any other course. The goal of the CTP is to produce a complete, well-written draft of a proposal containing all of the sections required by your research advisor. Creating an academically strong thesis proposal sets the foundation for a high-quality thesis and helps garner the attention of a well-respected thesis director. The proposal is normally between 15 to 25 pages in length.

The CTP tutorial is not a course in the traditional sense. You work independently on your proposal with your research advisor by submitting multiple proposal drafts and scheduling individual appointments. You need to make self-directed progress on the proposal without special prompting from the research advisor. You receive a final grade of SAT or UNSAT (failing grade).

The CTP for sustainability is a three-week course in the traditional sense and you receive a letter grade, and it must be B- or higher to receive degree credit for the course.

You are expected to incorporate all of your research advisor’s feedback and be fully committed to producing an academically strong proposal leading to a thesis worthy of a Harvard degree. If you are unable to take advice from your research advisor, follow directions, or produce an acceptable proposal, you will not pass the CTP.

Successful CTP completion also includes a check on the proper use of sources according to our academic integrity guidelines. Violations of our academic integrity policy will be referred to the Administrative Board.

Maximum of two attempts . If you don’t pass that CTP, you’ll have — if your five-year, degree-completion date allows — just one more attempt to complete the CTP before being required to withdraw from the program. If you fail the CTP just once and have no more time to complete the degree, your candidacy will automatically expire. Please note that a WD grade counts as an attempt.

If by not passing the CTP you fall into poor academic standing, you will need to take additional degree-applicable courses to return to good standing before enrolling in the CTP for your second and final time, only if your five-year, degree-completion date allows. If you have no more time on your five-year clock, you will be required to withdraw.

Human Subjects

If your thesis, regardless of field, will involve the use of human subjects (e.g., interviews, surveys, observations), you will need to have your research vetted by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (CUHS) of Harvard University. Please review the IRB LIFECYCLE GUIDE located on the CUHS website. Your research advisor will help you prepare a draft copy of the project protocol form that you will need to send to CUHS. The vetting process needs to be started during the CTP tutorial, before a thesis director has been assigned.

4. Thesis Director Assignment and Thesis Registration

We expect you to be registered in thesis soon after CTP completion or within 3 months — no later. You cannot delay. It is critical that once a research project has been approved through the CTP process, the project must commence in a timely fashion to ensure the academic integrity of the thesis process.

Once you (1) successfully complete the CTP and (2) have your proposal officially approved by your research advisor (RA), you move to the thesis director assignment phase. Successful completion of the CTP is not the same as having an officially approved proposal. These are two distinct steps.

If you are a life science student (e.g., biology), your thesis director was identified prior to the CTP, and now you need the thesis director to approve the proposal.

The research advisor places you with a thesis director. Do not approach faculty to ask about directing your thesis. You may suggest names of any potential thesis directors to your research advisor, who will contact them, if they are eligible/available to direct your thesis, after you have an approved thesis proposal.

When a thesis director has been identified or the thesis proposal has been fully vetted by the preassigned life science thesis director, you will receive a letter of authorization from the Assistant Dean of Academic Programs officially approving your thesis work and providing you with instructions on how to register for the eight-credit Master’s Thesis. The letter will also have a tentative graduation date as well as four mandatory thesis submission dates (see Thesis Timetable below).

Continuous Registration Tip: If you want to maintain continued registration from CTP to thesis, you should meet with your RA prior to prework to settle on a workable topic, submit well-documented prework, work diligently throughout the CTP to produce a high-quality proposal that is ready to be matched with a thesis director as soon as the CTP is complete.

Good academic standing. You must be good academic standing to register for the thesis. If not, you’ll need to complete additional courses to bring your GPA up to the 3.0 minimum prior to registration.

Thesis Timetable

The thesis is a 9 to 12 month project that begins after the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP); when your research advisor has approved your proposal and identified a Thesis Director.

The date for the appointment of your Thesis Director determines the graduation cycle that will be automatically assigned to you:

Once registered in the thesis, we will do a 3-month check-in with you and your thesis director to ensure progress is being made. If your thesis director reports little to no progress, the Dean of Academic Programs reserves the right to issue a thesis not complete (TNC) grade (see Thesis Grading below).

As you can see above, you do not submit your thesis all at once at the end, but in four phases: (1) complete draft to TA, (2) final draft to RA for format review and academic integrity check, (3) format approved draft submitted to TA for grading, and (4) upload your 100% complete graded thesis to ETDs.

Due dates for all phases for your assigned graduation cycle cannot be missed. You must submit materials by the date indicated by 5 PM EST (even if the date falls on a weekend). If you are late, you will not be able to graduate during your assigned cycle.

If you need additional time to complete your thesis after the date it is due to the Thesis Director (phase 1), you need to formally request an extension (which needs to be approved by your Director) by emailing that petition to: [email protected] . The maximum allotted time to write your thesis, including any granted extensions of time is 12 months.

Timing Tip: If you want to graduate in May, you should complete the CTP in the fall term two years prior or, if a sustainability student, in the January session one year prior. For example, to graduate in May 2025:

- Complete the CTP in fall 2023 (or in January 2024, if a sustainability student)

- Be assigned a thesis director (TD) in March/April 2024

- Begin the 9-12 month thesis project with TD

- Submit a complete draft of your thesis to your TD by February 1, 2025

- Follow through with all other submission deadlines (April 1, April 15 and May 1 — see table above)

- Graduate in May 2025

5. Conduct Thesis Research

When registered in the thesis, you work diligently and independently, following the advice of your thesis director, in a consistent, regular manner equivalent to full-time academic work to complete the research by your required timeline.

You are required to produce at least 50 pages of text (not including front matter and appendices). Chapter topics (e.g., introduction, background, methods, findings, conclusion) vary by field.

6. Format Review — Required of all Harvard Graduate Students and Part of Your Graduation Requirements

All ALM thesis projects must written in Microsoft Word and follow a specific Harvard University format. A properly formatted thesis is an explicit degree requirement; you cannot graduate without it.

Your research advisor will complete the format review prior to submitting your thesis to your director for final grading according to the Thesis Timetable (see above).

You must use our Microsoft Word ALM Thesis Template or Microsoft ALM Thesis Template Creative Writing (just for creative writing degree candidates). It has all the mandatory thesis formatting built in. Besides saving you a considerable amount of time as you write your thesis, the preprogrammed form ensures that your submitted thesis meets the mandatory style guidelines for margins, font, title page, table of contents, and chapter headings. If you use the template, format review should go smoothly, if not, a delayed graduation is highly likely.

Format review also includes a check on the proper use of sources according to our academic integrity guidelines. Violations of our academic integrity policy will be referred directly to the Administrative Board.

7. Mandatory Thesis Archiving — Required of all Harvard Graduate Students and Part of Your Graduation Requirements

Once your thesis is finalized, meaning that the required grade has been earned and all edits have been completed, you must upload your thesis to Harvard University’s electronic thesis and dissertation submission system (ETDs). Uploading your thesis ETDs is an explicit degree requirement; you cannot graduate without completing this step.

The thesis project will be sent to several downstream systems:

- Your work will be preserved using Harvard’s digital repository DASH (Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard).

- Metadata about your work will be sent to HOLLIS (the Harvard Library catalog).

- Your work will be preserved in Harvard Library’s DRS2 (digital preservation repository).

By submitting work through ETDs @ Harvard you will be signing the Harvard Author Agreement. This license does not constrain your rights to publish your work subsequently. You retain all intellectual property rights.

For more information on Harvard’s open access initiatives, we recommend you view the Director of the Office of Scholarly Communication (OSC), Peter Suber’s brief introduction .

Thesis Grading