Social Determinants of Health: Call for Nursing Education Reform

- First Online: 11 February 2023

Cite this chapter

- Linda McCauley 4

970 Accesses

Nursing has long been at the forefront of understanding the importance of communities—places of work, prayer, and play, and the overall environment—in determining the health of individuals. These factors have gained prominence as we have become a more global community and seen the stark disparities in longevity, overall health, and flourishing among populations. This chapter outlines why the nursing profession must integrate social determinants of health into twenty-first century curricula. We review our historic roots in caring for people in their communities, and why SDOH is being newly conceptualized as a fundamental premise of all nursing care. Adequately preparing the nursing workforce of the future will require a systematic approach to integrating these concepts into all aspects of nursing curricula.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

World Health Organization (WHO). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; 2008.

Google Scholar

Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31.

Article Google Scholar

McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21:78–93.

Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, Dimaggio C, Karpati A. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1456–65.

Fee E, Bu L. The origins of public health nursing: the Henry Street Visiting Nurse Service. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1206–7.

American Nurses Association (ANA). About ANA. 2020. Nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana

Beck AJ, Boulton ML. The public health nurse workforce in U.S. state and local health departments, 2012. Public Health Rep. 2016;131:145–52.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). For the public’s health: investing in a healthier future. Washington, DC: Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health; 2012.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). The future of nursing 2020–2030: charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press; 2021.

Thornton RL, Glover CM, Cené CW, Glik DC, Henderson JA, Williams DR. Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:1416–23.

Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:590–5.

Lathrop B. Nursing leadership in addressing the social determinants of health. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2013;14:41–7.

Dankwa-Mullan I, Rhee KB, Williams K, et al. The science of eliminating health disparities: summary and analysis of the NIH summit recommendations. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S12–8.

Chhabra M, Sorrentino AE, Cusack M, Dichter ME, Montgomery AE, True G. Screening for housing instability: providers’ reflections on addressing a social determinant of health. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1213–9.

Higginbotham K, Davis Crutcher T, Karp SM. Screening for social determinants of health at well-child appointments: a quality improvement project. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019;54:141–8.

Morgenlander MA, Tyrrell H, Garfunkel LC, Serwint JR, Steiner MJ, Schilling S. Screening for social determinants of health in pediatric resident continuity clinic. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19:868–74.

Morone J. An integrative review of social determinants of health assessment and screening tools used in pediatrics. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;37:22–8.

Walter LA, Schoenfeld EM, Smith CH, et al. Emergency department-based interventions affecting social determinants of health in the United States: a scoping review. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28:666–74.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing high-quality primary care: rebuilding the foundation of health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021.

National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR). The National Institute of Nursing Research 2022–2026 strategic plan. 2022.

Porter K, Jackson G, Clark R, Waller M, Stanfill AG. Applying social determinants of health to nursing education using a concept-based approach. J Nurs Educ. 2020;59:293–6.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). The essentials. AACN; 2021.

U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2030. 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health . Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Linda McCauley

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Linda McCauley .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Jill B. Hamilton

Emory Nursing Learning Center, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing,, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Beth Ann Swan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

McCauley, L. (2023). Social Determinants of Health: Call for Nursing Education Reform. In: Hamilton, J.B., Swan, B.A., McCauley, L. (eds) Integrating a Social Determinants of Health Framework into Nursing Education . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21347-2_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21347-2_1

Published : 11 February 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-21346-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-21347-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2022

The impact of social determinants of health on early childhood development: a qualitative context analysis in Iran

- Omolbanin Atashbahar 1 ,

- Ali Akbari Sari 2 , 3 ,

- Amirhossein Takian 2 , 4 , 5 ,

- Alireza Olyaeemanesh 5 ,

- Efat Mohamadi 5 &

- Sayyed Hamed Barakati 6

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 1149 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Social determinants have a significant impact on children’s development and their abilities and capacities, especially in early childhood. They can bring about inequity in living conditions of children and, as a result, lead to differences in various dimensions of development including the social, psychological, cognitive and emotional aspects. We aimed to identify and analyze the social determinants of Early Childhood Development (ECD) in Iran and provide policy implications to improve this social context.

In a qualitative study, data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 40 experts from October 2017 to June 2018. Based on Leichter’s (1979) framework and using the deductive approach, two independent researchers conducted the data analysis. We used MAXQDA.11 software for data management.

We identified challenges related to ECD context in the form of 8 themes and 22 subthemes in 4 analytical categories relevant to the social determinants of ECD including: Structural factors (economic factors: 6 subthemes, political factors: 2 subthemes), Socio-cultural factors (the socio-cultural setting of society: 6 subthemes, the socio-cultural setting of family: 4 subthemes), Environmental or International factors (the role of international organizations: 1 subtheme, political sanctions: 1 subtheme), and Situational factors (genetic factors: 1 subtheme, the phenomenon of air pollution: 1 subtheme). We could identify 24 policy recommendations to improve the existing ECD context from the interviews and literature.

With regard to the challenges related to the social determinants of ECD, such as increasing social harms, decreasing social capital, lack of public awareness, increasing socio-economic inequities, economic instability, which can lead to the abuse and neglect of children or unfair differences in their growth and development, the following policy-making options are proposed: focusing on equity from early years in policies and programs, creating integration between policies and programs from different sectors, prioritizing children in the welfare umbrella, empowering families, raising community awareness, and expanding services and support for families, specially the deprived families subject to special subsidies.

Peer Review reports

There is a lot of evidence that shows vital development in children begins before their birth and continues in the first 8 years of life [ 1 ]. In various literatures, this period is considered the most critical period in human life because it is the fastest period of brain development [ 2 ]. Also, it is the most cost-effective period of life to invest in the development of human capital [ 3 ]. However, an important consideration in this regard is that early childhood development (ECD) is not only affected by heredity but there are also numerous variables in the child’s living environment at the micro, meso, exo and macro levels which play an important role in ECD [ 4 ].

Among the factors that can affect ECD, the following can be mentioned: education of parents [ 5 ], maternal mental health [ 6 , 7 ], malnutrition, infectious diseases, exposure to environmental toxins [ 8 ], limitations of intrauterine growth [ 7 ], ethnicity [ 9 ], characteristics of family environment [ 10 ], quality of child care [ 7 , 11 ], parent-child interactions [ 12 ], socio-cultural context, biological factors, and genetic inheritance [ 5 ], child’s educational opportunities or cognitive motivators, and exposure to violence [ 7 ]. On the other hand, children’s failure to realize their developmental potential plays an important role in the intergenerational transmission of poverty [ 5 ]. The fact is that more than 200 million children in developing countries are failing to reach their developmental potential [ 13 ].

Given the nature of ECD, the issue of inequity has a particular importance, since unequal conditions and opportunities in society will have adverse effects on the development of children’s capacities and abilities in various social, psychological, emotional, and physical aspects [ 14 ]. Inadequate and unequal living conditions are the result of deeper structural factors that together shape the way societies are organized with inappropriate social programs and policies, unfair economic conditions, and inappropriate policies. In this regard, the new global agenda on health equity states that Our children have dramatically different opportunities to live, depending on where they are born. In Japan or Sweden, they can expect to live more than 80 years; in Brazil 72 years, in India it is 63 years and in one of several African countries, it is less than 50 years [ 15 ]. Between and inside the countries, there are huge differences in the chance of survival, and this can be seen all over the world. In many countries, at all income levels, the development of children and the outcomes of children and families follow a social gradient: the lower the socio-economic conditions are, the poorer the children’s pertaining conditions will be, and finally, the more unfavorable developmental status they will have. In this regard, and as reflected in a report by the World Health Organization’s Commission for Social Determinants of Health, (2008), entitled “Closing the Gap in a Generation”, ECD has been emphasized [ 16 ]. Also, in the sixth chapter of the Health in All Policies report entitled “ Seizing opportunities, implementing policies “ published by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland in 2013, the promotion of equity from the start through the ECD and health has been focused on in all policies [ 17 ].

In Iran, after the setting up of a Committee for Social Determinants of Health and the selection of ECD as one of its highest priority subjects, it was proposed that a policy document on ECD be drawn up by the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and the Welfare Organization in 2008. Nevertheless, this policy document has not been implemented at a national level [ 18 ]. As experts and policy makers in the field of children have reached a consensus, the current situation of Iranian society at all levels of ECD policy making is facing many challenges [ 19 ] such as the lack of integration and coordination between policies and programs in various sectors, the lack of focus on all aspects of ECD, and lack of emphasis on eliminating the existing inequities [ 20 ]. These problems regarding children’s development in the country have prevented them from fully achieving their rights [ 21 ].

In relation to child health, according to Iran’s Multiple Indicator Demographic and Health Survey (IrMIDHS, 2010), the rate of underweight and short stature in children has been reported to be 4.8 and 6.83%. Also, a heterogeneous distribution of child malnutrition at the national level with high prevalence in deprived provinces was seen [ 22 ]. The sampling method in this survey was multi-stage stratified cluster-random. The final sample size in this study was 31,350 households in the country. Information on sampling clusters was obtained from the Statistics Center of Iran [ 23 ]. Based on the national survey of anthropometric indices in children under 5, which was conducted in 2017, the percentage of underweight and short stature was reported to be 4.3 and 4.8% respectively and a significant difference was seen between urban and rural areas. In this study, the sample size is 600 children for each province and the data obtained from health ministry software (SIB software) were selected randomly [ 24 ]. Various studies have also shown a reduction in child mortality rates in Iran in recent decades [ 22 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. In this regard, in the IrMIDHS survey (2010), the mortality rates of under-5 children, infants and neonates per thousand live births were reported to be 22.52, 20.32 and 15.29 respectively and there were differences among various provinces of the country [ 22 ]. Moreover, based on Hosseinpoor’s (2005 and 2006.) studies, a significant difference was seen in infant mortality rate between various provinces and the lowest and highest socioeconomic quintiles [ 25 , 26 ]. In these studies, data extracted from the Iran’s Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), which was conducted in 2000 [ 28 ]. The concentration index of infant mortality was used to measure the socioeconomic inequalities [ 25 , 26 ].

On the other hand, in relation to child education and according to the Educational Inequality Index (UNDP) (2014), Iran ranks 12th in the region with a score of 0.433 followed by Syria, Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan [ 29 ]. Based on the report from the Social Welfare Studies Office, some reasons for the increase of inequality in education include the neglect of the quality of manpower in education, non-compulsory and non-free preschool education, failure to provide statistical reports on indicators of educational inequality by the government, and no attention paid to the field of education by civil society [ 30 ]. Given that, no study has so far been conducted in Iran to examine the policy context of ECD. Also, with regards to the importance of the early years in human capital development and sustainable development of the society as well as the critical role of social determinants in ECD, the study aims to identify and clarify the contextual factors affecting ECD and its policy process in order to identify policy recommendations to improve the current situation. The context refers to the circumstances and settings in which children are born and raised. It includes systematic economic, political, social, and cultural factors at national and international levels which may influence the ECD [ 31 ]. This study answers the following questions: What factors (including structural, situational, social, economic, political, and international) affect ECD and policymaking in various levels of micro, meso, exo and macro in Iran? What works to decrease the existing inequities and improve the context for optimal ECD?

Conceptual framework

In this qualitative study, the researchers attempted to explore the ECD context of Iran. We used the Leichter (1979) conceptual framework for policy context analysis. This divided contextual factors into four categories including: situational factors (irregular and unstable events such as war), cultural factors (values of society or different groups in society), structural factors (more stable factors of social organizations such as economic-political system) and environmental factors (factors outside the national system of politics such as multinational corporations) [ 32 ]. To collect the data, the researchers made use of interviews with experts from different sectors related to children including health and nutrition, early care and education, and protection.

Data collection

Forty face-to-face, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted from October 2017 to June 2018 using an interview guide (Appendix 1 ) in Tehran, Iran. Since no new data was added to our study during the last interviews, we concluded that the data has reached the saturation level. All interviews took place in the interviewees’ workplaces and each interview lasted for 30–90 minutes.

Sampling method

To select the participants, we used the purposive sampling approach with maximum variation in terms of scientific background, activity domain, employment status, gender, and executive experience. In addition, the snowball sampling method was used to identify more interviewees. The participants were divided into five groups including policymakers (PM), managers (M), academics and researchers (Aca), NGOs’ representatives (NGO-R), and children service providers (CSP) from different organizations related to ECD (Ministry of Health and Medical Education; State Welfare Organization; Ministry of Education; Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare; Ministry of Justice; Children’s Medical Center; The Islamic Consultative Assembly; Society for Protecting the Rights of the Child (SPRC); universities and research centers, etc.) (Appendix 2 ). The participants met at least one of the following criteria:

Specializing in majors related to children or neuroscience, social sciences, human sciences, and rehabilitation sciences

Having at least 3 years of professional experience with children in non-governmental or governmental sectors

Having a position related to children’s affairs in non-governmental or governmental sectors at the time of the study (Appendix 2 )

Data analysis

For data analysis, a deductive approach was used. In this regard, the interviews were transcribed verbatim, the codes were extracted from the summaries of the interviews, the open coding was carried out, and the extracted codes were finally categorized based on Leichter’s (1979) framework [ 32 ] using the thematic analysis approach. Coding and data categorization were done manually. MAXQDA.11 software was also used to assist data management. To ensure the accuracy of statements, transcripts were sent to the participants who were asked to confirm if necessary It should be noted that in the meantime, no changes were made to the transcripts. AA and OA also analyzed the data separately and then cross-checked the extracted themes and sub-themes, discussing the differences among some of the obtained themes and sub-themes and reaching a consensus. The consensus was then finalized by two team supervisors (AT, EM) and the confirmation was made by cheking these changes to ensure the validity of the qualitative analysis and the consistency of the findings among the authors.

Ethical considerations

Before the interviews, necessary information regarding the study and its objectives were given to the participants and informed consent was obtained from them verbally. Moreover, they were assured that their information would remain confidential and the data of the study would be analyzed anonymously. Also, the current study has been confirmed by the Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.REC.1396.2694).

The results of this study are presented based on Leichter’s (1979) framework under analytical categories including structural, socio-cultural, environmental (international), and situational factors. In our study, 8 themes and 22 subthemes were identified (Tables 1 , 2 , 3 and 4 ). These categories are presented in the following:

Structural factors

In this analytical category, two themes and eight sub-themes were identified.

Economic factors

The participants stated that economic factors change the well-being of children through various ways. These factors can directly affect children’s well-being and development by increasing or decreasing family financial resources. Indirectly, these factors can affect government revenues and the sustainability of government resources to provide beneficial services to children. Although the living conditions of the family are affected by the macroeconomic status of the country, even in prosperous and developed countries, there are deprived and poor families. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the economic status of families separately. In this study, factors such as parents’ employment status, family income and housing status have been identified as indicators of family living conditions. Also, the concept of economic inequities was repeatedly cited by experts in the interviews as one of the most important factors influencing children’s opportunities for optimal development and ultimately the continuous vicious cycle of poverty.

“Well, when you compare countries, you certainly see countries that have high economic growth and their economic situation is better, the quality of life of their children is higher, and they receive the high-quality services (CSP 4) .”

“If the family is suffering from issues such as poverty and unemployment, this family will not be able to take positive actions in this regard, no matter how much you talk about the development of the children and increase the knowledge of that family (PM10) .”

“If you look at the investment curve of the country, it is a linear curve, which is the complete opposite of opportunity. We have the highest investments in the third, fourth and fifth decades of human life and the resources are spent there, while milestones of development are established in early years (PM9) .”

“ Inequities and gaps between the rich and the poor in the country and the problems caused by the poverty of families such as the phenomenon of working children, addiction, child abuse, etc. exacerbate the issue (PM 8) .”

Political factors

Political factors were one of the important issues which have a significant impact on ECD and the design of programs and policies in this regard. In this category, participants pointed to the politicization and policy-based decisions made by these streams of thought and politics.

“The fact is that our political and national discourse on children only goes back to school education. That means we do not have a very coherent, comprehensive discourse on children (PM 22) .”

“One of the main problems that we face in the field of children, which is perhaps less seen, is the contradictory political attitudes and thoughts that we have towards family, women and children (PM 12) .”

Socio-cultural factors

In this analytical category, two themes and ten sub-themes were identified.

The socio-cultural setting of society

Another point that was mentioned in the interviews as an important factor in ECD was the socio-cultural factors of society. According to the findings of this study, the socio-cultural context of society affects ECD directly and indirectly (by influencing the socio-cultural context of the family). In this study, the socio-cultural context of society has been identified by several concepts including social inequalities, uneven urban development, declining social capital, misconceptions and ignorance of society, development of communication technology and media, and issues in the national educational system. In several interviews, for instance, the uneven development of urbanization was mentioned as a social-cultural factor which has made cities an unsafe and unfriendly environment for children. Participants stated that the uneven development of urbanization is associated with many consequences, including increasing social harm, expanding marginalization, changing lifestyles, creating a harsh city, air pollution, noise pollution, etc., each of which will affect ECD in special ways. Another concept that was mentioned as an effective factor in children’s development was the social capital. In other words, the interviewees referred to the negative impacts of decreased social capital on children’s personality by decreasing public trust and weakening empathy, social responsibility, and identity.

“How many of us are marginalized now? Statistics say that we have twelve million marginalized people, some say eighteen million, right? What does marginalized mean? That is, those who do not receive education, care and health facilities that are necessary for the growth and development of their children? (CSP 18) .”

“Social capital in our society has decreased, distrust is too much; this affects how the child's personality is formed (M 17) . “

“Many parents, people and teachers still consider physical and verbal punishment as correct methods of nurturing while these are examples of child abuse (Aca 4) .”

The socio-cultural setting of family

The family plays an important role in the well-being and development of children. Parental behavior and family environment can promote or inhibit children’s development. In this study, factors such as socio-demographic variables of the family have been identified as effective factors in ECD in relation to the socio-cultural context of the family. For example, many participants referred to family harms including various types of domestic violence (such as physical, sexual, psychological, and verbal violence and indifference), mental problems of parents (such as stress, anxiety, depression), parental conflict, separation or loss of parents) as factors influencing children’s development. Another very important factor that was repeatedly mentioned in the interviews was the knowledge, attitude and practice of parents regarding parenting. In other words, parenting style was believed to have a tremendous impact on the formation of children’s personality and development. In several interviews, the weakness of families in nurturing their children has been mentioned. Issues which were mentioned in connection with the role of parenting included nurturing of dependent and non-capable children, children with inability to say no, those with inability to solve problems and those who lack social skills. Such issues also included nurturing children with emotional deficiencies and mental problems as well as children who will face academic failure and social harms in the future.

“I think we have some defects in parenting. With my experience in psychology, we do not have many independent children. Or we sometimes see that they do not have the ability to say no or their problem-solving abilities are weak. There are a number of nurturing problems (Aca 26) . “

“Domestic violence, from physical and verbal violence to other types of violence in our country, is at a high rate. Research has shown that children have this experience in terms of psychology (PM 13) .”

“Our children have little information about their rights. Families should provide some information and lessons to their children, but we see that families do not even educate their children about healthy behaviors (NGO-P 11) .”

Environmental (international) factors

In this analytical category, two themes and two sub-themes were identified.

The role of international organizations

Among the interviews, the role of international organizations including UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization was mentioned. Interviewees stated that the political commitment of international organizations to ECD could play an important role in facilitating national political commitments to young children. Interviewees cited the financial and technical support of these international organizations to the countries.

“International programs also have an impact on the national context of countries, such as the Sustainable Development Goals, which include seventeen core programs, some of which are directly related to health and some are directly related to poverty alleviation.” “It can also have a positive effect on our country so that we can finally pay more attention to these programs (Aca 1) . ”

Political sanctions

Another issue raised by some interviewees was political sanctions as an external and international factor influencing the conditions and well-being of society, including the development of children.

“Well, now these sanctions that we are facing act as a lever of pressure and disturb the condition in the country, so that they can have many effects on different people in society and lead to the violation of the rights of people, including children (PM33) .”

Situational factors

In this analytical category, three themes and three sub-themes were identified.

Genetic factors

Genetic factors are mentioned as a situational factor in interviews with health policy makers and health service providers. They stated that development is the result of a combination of both environmental and genetic factors. Therefore, genetic factors can be the source of some developmental disorders and defects in children.

“Children's development is affected by various factors, including psychological, social, hereditary and environmental factors, so we can say that children's development is the result of a dynamic and continuous interaction of biological and acquired factors (CSP 18) .”

The phenomenon of air pollution

Air pollution in some regions of the country was another situational factor mentioned in our study. This phenomenon has adverse effects on the physical and mental development of children as one of the vulnerable and sensitive groups in the society. It has also been stated that children living in societies with low socioeconomic status are more likely to be exposed to toxic waste, air pollution, poor water quality, excessive noise, and poor housing quality.

“Well, look at the problem of air pollution and dust, which can have an impact on the health of society, especially pregnant women and children. Some of these problems manifest themselves in the short term, such as shortness of breath, allergies, asthma, and some manifest themselves in the long term. (PM 40) .”

“The effects of air pollution, noise pollution, and poor environmental quality are greater on poor children because they probably have very poor access to protective equipment and facilities (M14) .”

According to the results of this study, economic factors can make a significant difference in children’s life conditions and affect the financial space of governments and families to invest in ECD. This issue has been emphasized in many studies. According to the World Bank, OECD member countries spend about 1.6% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on family and preschool services for children aged 0 to 6, of which 0.43% is spent on kindergartens alone. By comparison, low-income countries such as Nepal, Kenya, and Tajikistan spend only 0.1% of their GDP on preschool services, compared with less than 0.002% in Nicaragua and Senegal [ 33 ]. Based on the results of PISA study (2012), the mathematical performance of 15-year-old students in countries such as Italy, Greece, Finland, Thailand, Spain, etc., as compared to their performance in 2003, shows an increase of 25 points, which is due to an increase in the enrollment rate in preschools in this period in the mentioned countries [ 34 ]. In Iran, privatization in public education and, at the same time, a significant (50%) reduction in the share of education in the public budget are the main reasons for the increase of educational inequalities [ 30 ] so that statistics from 2011 to 2012 shows that the government’s involvement in preschool education was only for licensing. According to statistics, the number of government-run preschool centers have dropped to zero in this year [ 35 ]. World Bank’s report (2003) it was stated that the positive impact of preschool on improving education and breaking the poverty cycle can be proven in the case of Iran [ 30 ].

Economic inequities were also emphasized in our study. This shows that economic growth alone is not enough, but the distribution and quality of this growth is very important. In this regard, Boyden has emphasized the nature and quality of economic growth for ECD in his study. He states that policies should be made to ensure the sustainability of investments, to focus on the most vital stage in childhood, and to bring about benefits for all children [ 36 ]. Another study by Bennett has shown that improvements in children’s access have been distributed differently among different socioeconomic groups, and different results have been achieved [ 6 ]. Abbasian and Mahmoudi, in their study, examined the situation of child poverty in Iran. The results showed that on average between 22 and 27% of children suffered from poverty during 1983–2013. This study also showed that rural children and girls have a higher poverty rate than urban children and boys [ 37 ]. Also, according to the Social Studies and Research Institute of Iran, 34.7% of street children are hungry [ 38 ]. In the area of education, the difference in preschool coverage rates between urban and rural areas has not changed in Iran during the 1980s and 1990s, and the gap between the two areas has always been 15 to 20% [ 29 ]. For example, the coverage rate for urban and rural preschools in 2006 was 56.7 and 34.7%, respectively [ 30 ].

Another issue mentioned in this study is the role of political factors in the form of various political and intellectual mainstreams which impact the design of appropriate programs and policies for children. Since the influence of attitudes, interests, expediencies and political decisions on phenomena at the level of community is quite evident, the role of the political context in ECD has been emphasized in several studies [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Vegas states that the political context influences a country’s investment in ECD and the type of policies and programs it finances [ 39 ]. Also, Moussa’s study shows that the political violence affects the children’s mental health [ 41 ].

In our study, the effect of socio-cultural factors on ECD, like economic factors, has been considered at both macro and micro levels. The essence and quality of the social environment affect the ECD and the performance of families [ 42 ]. Among these factors, social inequalities play a critical role. The increased risk of adverse health outcomes is not limited to the lowest levels of poverty and socioeconomic status, but many child health outcomes indicate that there is a social slope. For example, birth weight indicates a specific social slope that has profound effects not only on childhood and infancy but also on adulthood [ 43 ]. Vaida argues in his study that racial and ethnical inequalities play a significant role in birth outcomes in Wisconsin. A higher proportion of infants born to black/African American women than infants born to white women are low birth weight and premature, which is the leading cause of death for black/African American infants [ 44 ]. Participants also cited the consequences of uneven urban development as lifestyle changes, increased marginalization, and social harm, all of which have negative effects on children’s development, including obesity, increased violence against children, and the creation of an insecure environment for children. Based on Jalili Moayad’s results, Iranian working children experience a relatively high rate of abuse in their work environments. 77.6% of these children have experienced at least one type of abuse, of which emotional abuse is the highest at 70.4%, followed by negligence at 52% [ 45 ].

Also, the report on the kids in communities shows that neighborhoods marked with security concerns, garbage on the streets, and delinquency were associated with a number of adverse health behaviors and consequences, including overweight and childhood obesity, behavioral problems, and other negative consequences of child development [ 39 ]. Moreover, Powers et al. emphasized the role of social capital and stated that poor social cohesion, social capital, and social support are associated with increased maternal postpartum depression, child abuse, and alcohol drinking and smoking in pregnancy [ 46 ] and potentially play a role in the current health slope among children [ 47 ]. This finding is consistent with the results of our study. In addition to addressing the social and economic causes of childhood inequities, it is important to consider cultural factors as well. In this study, cultural factors that can affect the physical and psychological development of children are referred to. These factors appear in the form of misconceptions and lack of awareness in the society with regard to parenting methods such as the belief in physical punishment in child rearing or their beliefs about the unnecessity of child sexual education. Such misconceptions have also been addressed in other studies. For example, Moore states that one of the cultural misconceptions among Australians is that young children are passive in absorbing concepts and their lives are perceived to be so simple that will not be disturbed or disrupted by influential factors. He argues that these misconceptions can indirectly increase or maintain early childhood inequities by influencing public opinions in general, and the extent of governmental support and investments in reducing early childhood inequities [ 47 ]. In Iran, negative beliefs such as avoiding to feed the baby with colostrum to prevent neonatal jaundice are seen among some ethnicities, especially those living in rural areas [ 48 ] Based on Oveisi’s study, in general, the families believe that the use of physical punishment in raising children is sometimes necessary [ 49 ]. Also, according to IRMDIS study, 18.18% of parents considered the use of physical punishment appropriate for raising a child and 79.33% used verbal punishment to raise a child [ 22 ].

Based on our findings, Families play a critical role in the well-being and development of children. Parental behavior and family environment can promote or inhibit children’s development. Because families are the first environments in which children interact with others from birth, they play a very important role in preparing children with stimulation, support and kindness. These characteristics are, in turn, influenced by the resources that families have to devote to parenting (strongly influenced by income), which is the same as their parenting style. Such characteristics tend to provide a rich and responsive environment (strongly influenced by parents’ education levels) [ 39 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Hesterman states that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) such as abuse, neglect, domestic violence, discrimination, etc. and toxic stress (non- tolerable stress) threaten the physical and mental health of the child, impairing their brain development and emotional regulation. Moreover, their long-term effects are evident in adulthood [ 53 ]. In this regard, Hajnasiri in a meta-analysis study with a sample size of 15,514 on 31 articles from 2000 to 2014 estimated the prevalence of domestic violence at 66% in Iran [ 54 ] which could have adverse effects on children’s development. Still, there are not enough legislations or organizations to support these victims [ 55 ].

This study revealed that international factors, including the political commitment of international organizations to ECD, could play an important role in facilitating national political commitments to young children. Strong sponsors of ECD investment such as the UNESCO, the UNICEF, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization can provide financial support and technical advice to country leaders, including the latest evidence and the best practices. In addition, international development treaties can support national and social policies that focus on the needs of children. International policies, such as the Millennium Development Goals, offer developing countries a challenge and an opportunity. Millennium Development Goals are very child-centered, with a strong focus on children and synergies at the international and national levels that can be used to promote common child-friendly policies [ 40 ].

According to the results of our study, genetic factors are among the situational factors that can be the source of some developmental disorders and defects in children. The analysis of the effect of genes and the environment on the transmission of antisocial behaviors from parents to children, depression and hyperactivity shows that both genetics and family environment play a role in this regard [ 51 ]. The results of various studies have shown a vigorous relationship between early adverse conditions and epigenetic changes in genes related to stress responses, immunity, and the increase of mental disorders [ 56 ]. For example, based on the results of Roth’s study, early infant ill-treatment was associated with decreased expression of genes responsible for appropriate serotonin required to preserve mood balance [ 57 ]. In this regard, Vaida states that the integrated nature of growth and development is largely preserved through constant interactions between genes, hormones, nutrients, and other factors. Some of these factors that affect physical function are rooted in heredity. Factors such as season, dietary restrictions, and severe psychological stress are rooted in the environment. Other factors, such as the socioeconomic class, reflect a complex combination of hereditary and environmental effects which are likely to play a role throughout development [ 44 ]. Many studies have also emphasized the negative effects of air pollution as a situational factor on pregnant mothers and children. In this regard, Pem states in his study that fetuses that are exposed to lead and arsenic before birth may be born prematurely or at a low birth weight, and as a result, this can affect the development of the child [ 52 ].

ECD focuses on equity and reducing the gap between rich and poor from the early years. Inequity in socioeconomic conditions will adversely affect the integrated development of early childhood, and children ‘s lack of optimal development will lead to the continuation of this unfavorable cycle. This principle is very weak in the current policies and programs of the country. Fair promotion of economic, cultural and social conditions of the society and consequently of the families can be very helpful in ECD and achieving the sustainable development of the society. While the context of our country is facing many challenges such as increasing social harms, reducing social capital, lack of public awareness, increasing socio-economic inequities, reducing economic growth, economic instability, etc. this will provide conditions for the abuse and neglect of children or their unfair growth and development. We should, therefore, consider creating integration between policies and programs of different sectors, prioritizing children in the welfare umbrella, empowering families, raising community awareness, and expanding services and support for families, specially the deprived families subject to special subsidies. Finally, we recommend that further studies be conducted on ECD in Iran including a survey of developmental disorders and delays in children and their relationship with social determinants of health, designing and surveying indicators in early care and education and support areas of children such as quality of early care and education, play, children with special needs, poverty, abuse, neglect, domestic violence, discrimination, children street, toxic stress and etc., conducting an evaluation/review of progress in reducing inequalities in various aspects of ECD, assessing the knowledge, attitude and practice of parents in relation to ECD in rural and urban areas, and examining the pilot implementation of ECD policy and its consequences in order to provide policy solutions.

Strengths and limitations

This study was the first of its kind in conducting a deep and extensive analysis of social determinants of ECD in Iran. The results of the current study can improve the developmental conditions of children and lead to more attention to contextual factors in formulating policies related to ECD. However, our study has two main limitations; first, we have not presented the developmental status of children in various areas of ECD in the form of figures due to the lack of statistics and information in this field in our country. Second, some participants were not able to participate in the confirmation process because of their busy schedule and the lack of time.

Policy recommendations

Availability of data and materials.

The data of this study are raw data which were accessible to the researchers in the interviews and are reported in the paper. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Avan BI, Kirkwood BR. Review of the theoretical frameworks for the study of child development within public health and epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:388–93.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Busolo B, Agembo W. Access and equity in early childhood education: challenges and opportunities. Baraton Interdiscip Res J. 2017;7:1–7.

Google Scholar

Heckman JJ, Cunha F. Investing in our young people. The National Institutes of Health and the Committee for Economic DevelopmentChicago: University of Chicago; 2006. http://jenni.uchicago.edu

Woodhead M, Bolton L, Featherstone I, Robertson P. Early childhood development: delivering inter-sectoral policies, programmes and services in low-resource settings. In: The Health & Education Advice & Resource Team (HEART); 2014.

McGregor SG, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B, et al. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:60–70.

Article Google Scholar

Bennett IM, Schott W, Krutikova S, Behrman JR. Maternal mental health and child growth and development in four low-income and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:168–73.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Walker SP, Wachs TD, Gardner JM, Lozoff B, Wasserman GA, Pollitt E, et al. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:145–57.

Walker SP, Wachs TD, Grantham-McGregor S, Black MM, Nelson CA, Huff man SL, et al. Inequality in early childhood: risk and protective factors for early child development. Lancet. 2011;378:1325–38.

Sacker A, J. Kelly Y. Ethnic differences in growth in early childhood: an investigation of two potential mechanisms. Eur J Pub Health. 2012;22(2):197–203.

Schoon I, Jones E, Cheng H, Maughan B. Family hardship, family instability and cognitive development. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:716–22.

Gialamas A, Mittinty MN, Sawyer MG, Zubrick SR, Lynch J. Social inequalities in childcare quality and their effects on children’s development at school entry: findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:841–8.

De Falco S, Emer A, Martini L, Rigo P, Pruner S, Venuti P. Predictors of mother–child interaction quality and child attachment security in at-risk families. Front Psychol. 2014;5:898. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00898 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Engle P, Black M, Behrman J, Cabral de Mello M, Gertler P, Kapiriri L, et al. Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet. 2007;369:229–42.

Moore T, McDonald M, McHugh-Dillon H. Early childhood development and the social determinants of health inequities: a review of the evidence. Parkville: Centre for Community Child Health at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and the Royal Children’s Hospital; 2014.

WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health final report. World Health Organization; 2008.

Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houwelin TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–9.

Leppo K, Ollila E, Pen˜a S, Wismar M, Cook S. Health in all policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. In: Ministry of social affairs and health, Finland; 2013.

National Secretariat of the integrated of early childhood development. National policy document on integrated early child development. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Ministry of education and welfare organization; 2013. (origin persian).

Vameghi R, Marandi A, Sajedi F, Soleymani F, Shahshahanipour S, Hatamizadeh N. Strategic analysis of the situation in Iran regarding the development of young children (analysis swot) and proposed strategies and activities. J Soc Welf. 2010;9(35):379–412 ( origin persian).

Atashbahar O, Akbari Sari A, Takian A, Olyaeemanesh A, Mohamadi E, Barakat SH. Integrated early childhood development policy in Iran: a qualitative policy process analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:649.

Rarani MA, Nosratabadi M, Moeeni M. Early childhood development in Iran and its provinces: Inequality versus average. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(4):1136–45.

Rashidian A, Khosravi A, Khabiri R, Khodayari-Moez E, Elahi E, Arab M, et al. Islamic Republic of Iran's multiple Indicator demographic and health survey (IrMIDHS) 2010. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2012. (origin persian)

Rashidian A, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Khosravi A, et al. Iran's multiple Indicator demographic and health survey - 2010: study protocol. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(5):632–42.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ministry of Health and Medical Education. national survey of anthropometric status, nutritional and growth and development indicators, and some indicators of health services evaluation in children Under five years. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2018. (origin persian).

Hosseinpoor AR, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R, Naghavi M, Abolhassani F, Sousa A, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in infant mortality in Iran and across its provinces. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:837–44.

Hosseinpoor AR, Van Doorslaer E, Speybroeck N, Naghavi M, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R, et al. Decomposing socioeconomic inequality in infant mortality in Iran. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1211–9.

Khosravi A, Taylor R, Naghavi M, Lopez AD. Mortality in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1964-2004. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:607–14.

Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Population and Health in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Iran Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2000. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2000. (origin persian).

Abasi L, Bayat M. With the people's representatives in the tenth parliament, report 19. Introduction to the education sector. In: Office of Social Studies, Parliamentary Research Center, vol. 14870; 2016. https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/report/show/970064 . (origin Persian).

Karimian J. Collection of reports on poverty, inequality and conflict of interest: poverty and inequality in education: Ministry of Cooperatives, labor and social welfare, deputy of social welfare, Office of Social Welfare Studies; 2020. https://poverty-research.ir/blog/study-reports/5276/ .(origin Persian)

O'Brien GL, Sinnott SJ, Walshe V, Mulcahy M, Byrne S. Health policy triangle framework: narrative review of the recent literature. Health Policy Open. 2020;1:100016.

Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making health policy. UK: McGraw-hill Education; 2012.

Lake A. Early childhood development—global action is overdue. Lancet. 2011;378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61450-5 .

OECD (2014) PISA in focus – 2014/06 (June) does pre-primary education reach those who need it most?

Abasi L, Pouzesh SH. Assessing the preschool situation with emphasis on legal documents and duties of the welfare organization and the Ministry of Education, vol. 13662: Office of Social Studies, Parliamentary Research Center; 2014. https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/report/show/887366 . (origin Persian)

Boyden J, Dercon S. Child development and economic development: lessons and future challenges: Young Lives; 2012. www.younglives.org.uk

Abasian E, Mahmoudi V. Multidimensional poverty of families with children in Kerman province using the generational approach: 1983–2013. Soc Dev Quarterly. 2016;11(1):35–52 origin Persian.

Vameghi M, Dejman M, Rafiei H, Roshanfekr P. Urgent assessment of children’s street situation in Tehran: causes and risk of working children on the street. Quarterly Soc Stud Res Iran Univ Tehran. 2013;4(1):34–53.

Goldfeld S, Villanueva K, Lee JL, Robinson R., Moriarty A, Peel D et al. Foundational community factors (FCFs) for Early Childhood Development: A report on the Kids in Communities Study; 2017.

Vegas E, Santibáñez L, Brière BL, Caballero A, Hautier JA, Devesa DR. The promise of early childhood development in Latin America and the Caribbean: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / the World Bank; 2010. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-7759-8 .

Book Google Scholar

Moussa S, El Kholy M, Enaba D, Salem K, Ali A, Nasreldin M, et al. Impact of political violence on the mental health of school children in Egypt. J Ment Health. 2015;24(5):289–93. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1019047 .

Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Spencer N. Social, economic, and political determinants of child health. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3):704–6.

Vaida N. A study on various factors affecting growth during the first two years of life. Eur Sci J. 2003;8(29):16–37.

Jalili Moayad S, Mohaqeqi Kamal SH, Sajjadi H, Vameghi M, Ghaedamini Harouni Gh, Makki Alamdari S. Child labor in Tehran, Iran: Abuses experienced in work environments. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;117:105054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105054 .

Powers JR, McDermott LJ, Loxton DJ, Chojenta CL. A prospective study of prevalence and predictors of concurrent alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:76–84.

Moore TG, McDonald M, Carlon L, O’Rourke K. Early childhood development and the social determinants of health inequities. Health Promot Int. 2015;30:S2 ii102–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav031 .

Keshavar Z, Abassi A-SMJ, Ebadi A, Alavi moghadam F, Salari E. Ethnic, cultures and reproductive behavior in North Khorasan. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2017;9(1):109–19 origin Persian.

Oveisi S, Eftekhare Ardabili H, Majdzadeh R, Mohammadkhani P, Jean AR, Loo J. Mothers’ attitudes toward corporal punishment of children in Qazvin- Iran. J Fam Violence. 2010;25(2):159–64.

Maggi S, Irwin LG, Siddiqi A, Poureslami I, Hertzman E, Hertzman C. Knowledge network for early child development. Analytic and Strategic Review Paper: International Perspectives on Early Child Development. World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health; Human Early Learning Partnership; 2005. p. 6–9.

Ibberson CL. Environmental factors among young children contributing to the onset of behavior disorders. In: Culminating projects in Special Education, vol. 46; 2017. http://repository.stcloudstate.edu/sped.etds/46 .

Pem D. Factors Affecting early childhood growth and development: golden 1000 days. J Adv Pract Nurs. 2015;1(1). https://doi.org/10.4172/2573-0347.1000101 .

Hesterman M. The effects of adverse childhood experiences on long-term brain development and health development and health. Aisthesis. 2021;12(1).

Hajnasiri H, Gheshlagh Ghanei R, Sayehmiri K, Moafi F, Farajzadeh M. Domestic violence among Iranian women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(6):e34971 (origin Persian).

Ghaffarihosseini F, Jalali Nadoushan AM, Alavi K, Bolhari J. Supporting the victims of domestic violence in Iran: two decades of effort. J Inj Violence Res. 2021;13(2):161–4. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.vo113i2.1638 .

Sokolowski MB, Boyce WT. Epigenetic embedding of early adversity and developmental risk. In: ENCYCLOPEDIA on Early Childhood Development (CEECD); 2017.

Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):760–9.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Ministry of education, Welfare Organization of Iran and Tehran University of Medical sciences for their participation in the interviews.

This research was funded by Tehran University of Medical sciences.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health, Sirjan School of Medical Sciences, Sirjan, Iran

Omolbanin Atashbahar

Department of Health Management and Economics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Ali Akbari Sari & Amirhossein Takian

National Institute for Health Research, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Ali Akbari Sari

Department of Global Health and Public Policy, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Amirhossein Takian

Health Equity Research Centre (HERC), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, No. 70, Bozorgmehr Ava., Vesal St., Keshavars Blvd, Tehran, 1416833481, Iran

Amirhossein Takian, Alireza Olyaeemanesh & Efat Mohamadi

Population, Family and School Health Office, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Tehran, Iran

Sayyed Hamed Barakati

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

OA, AS, AT and AO designed this study and determined its methods. OA conducted the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data with assistance from AS and AT for revising the analytical approach. OA and HB carried out the analytical experiment. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. OA, AS and EM wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the development and approval of the final manuscript. AS is the guarantor.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Efat Mohamadi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics and consent to participate.

In our study, before the interviews, necessary information regarding the study and its objectives were given to the participants and informed consent was obtained from them verbally and recorded audio. The current study is approved by the Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Science (code: IR.TUMS.REC.1396.2694) and all the used methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The verbal informed consent procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Science that confirmed the present study (code: IR.TUMS.REC.1396.2694). It should also be noted that written consent was not necessary for this study because the names of the interviewees were not mentioned in the findings. Moreover, participants were assured that their information would remain confidential and the data of the study would be analyzed anonymously.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Atashbahar, O., Sari, A.A., Takian, A. et al. The impact of social determinants of health on early childhood development: a qualitative context analysis in Iran. BMC Public Health 22 , 1149 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13571-5

Download citation

Received : 08 October 2021

Accepted : 03 June 2022

Published : 08 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13571-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Early childhood development

- Social determinants

- Policy analysis

- Health policy

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Social Determinants of Health

What are social determinants of health.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

SDOH can be grouped into 5 domains:

Suggested citation

Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved [date graphic was accessed], from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) have a major impact on people’s health, well-being, and quality of life. Examples of SDOH include:

- Safe housing, transportation, and neighborhoods

- Racism, discrimination, and violence

- Education, job opportunities, and income

- Access to nutritious foods and physical activity opportunities

- Polluted air and water

- Language and literacy skills

SDOH also contribute to wide health disparities and inequities. For example, people who don't have access to grocery stores with healthy foods are less likely to have good nutrition. That raises their risk of health conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and obesity — and even lowers life expectancy relative to people who do have access to healthy foods.

Just promoting healthy choices won't eliminate these and other health disparities. Instead, public health organizations and their partners in sectors like education, transportation, and housing need to take action to improve the conditions in people's environments.

That's why Healthy People 2030 has an increased and overarching focus on SDOH.

How Does Healthy People 2030 Address SDOH?

One of Healthy People 2030’s 5 overarching goals is specifically related to SDOH: “Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and well-being for all.”

In line with this goal, Healthy People 2030 features many objectives related to SDOH. These objectives highlight the importance of "upstream" factors — usually unrelated to health care delivery — in improving health and reducing health disparities.

More than a dozen workgroups made up of subject matter experts with different backgrounds and areas of expertise developed these objectives. One of these groups, the Social Determinants of Health Workgroup , focuses solely on SDOH.

Explore Research Related to SDOH

Social determinants of health affect nearly everyone in one way or another. Our literature summaries provide a snapshot of the latest research related to specific SDOH.

View SDOH Infographics

Each SDOH infographic represents a single example from each of the 5 domains of the social determinants of health. You can download them, print them, and share them with your networks.

Learn How SDOH Affect Older Adults

SDOH have a big impact on our chances of staying healthy as we age. Healthy People’s actionable scenarios highlight ways professionals can support older adults’ health and well-being.

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity

Samantha Artiga and Elizabeth Hinton Published: May 10, 2018

- Issue Brief

Introduction

Efforts to improve health in the U.S. have traditionally looked to the health care system as the key driver of health and health outcomes. However, there has been increased recognition that improving health and achieving health equity will require broader approaches that address social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health. This brief provides an overview of these social determinants of health and discusses emerging initiatives to address them.

What are Social Determinants of Health?

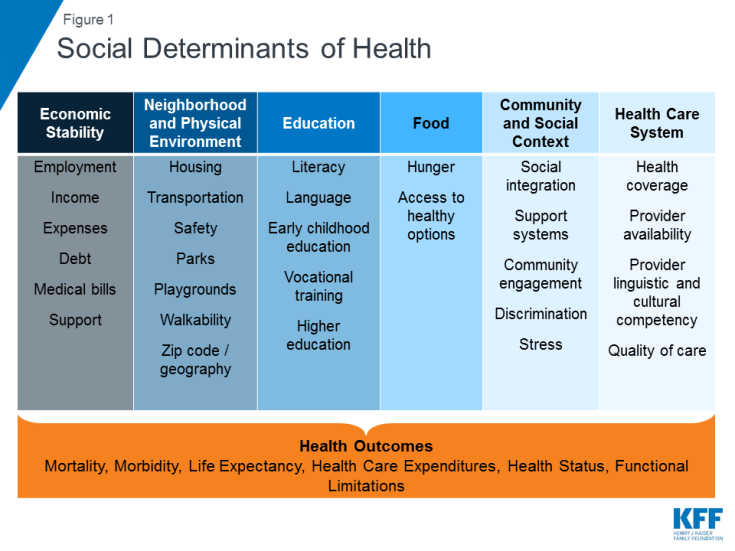

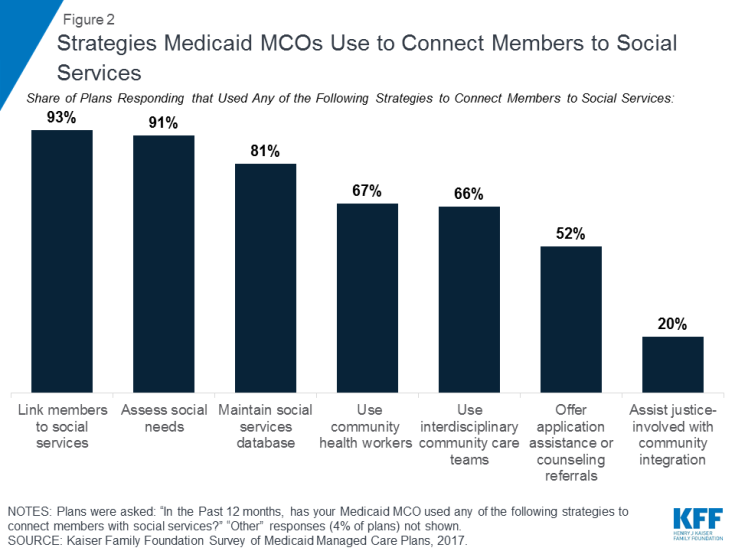

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. 1 They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Social Determinants of Health

Addressing social determinants of health is important for improving health and reducing health disparities. 2 Though health care is essential to health, it is a relatively weak health determinant. 3 Research shows that health outcomes are driven by an array of factors, including underlying genetics, health behaviors, social and environmental factors, and health care. While there is currently no consensus in the research on the magnitude of the relative contributions of each of these factors to health, studies suggest that health behaviors, such as smoking, diet, and exercise, and social and economic factors are the primary drivers of health outcomes, and social and economic factors can shape individuals’ health behaviors. For example, children born to parents who have not completed high school are more likely to live in an environment that poses barriers to health such as lack of safety, exposed garbage, and substandard housing. They also are less likely to have access to sidewalks, parks or playgrounds, recreation centers, or a library. 4 Further, evidence shows that stress negatively affects health across the lifespan 5 and that environmental factors may have multi-generational impacts. 6 Addressing social determinants of health is not only important for improving overall health, but also for reducing health disparities that are often rooted in social and economic disadvantages.

Initiatives to Address Social Determinants of Health

A growing number of initiatives are emerging to address social determinants of health. Some of these initiatives seek to increase the focus on health in non-health sectors, while others focus on having the health care system address broader social and environmental factors that influence health.

Focus on Health in Non-Health Sectors

Policies and practices in non-health sectors have impacts on health and health equity. For example, the availability and accessibility of public transportation affects access to employment, affordable healthy foods, health care, and other important drivers of health and wellness. Nutrition programs and policies can also promote health, for example, by supporting healthier corner stores in low-income communities, 7 farm to school programs 8 and community and school gardens, and through broader efforts to support the production and consumption of healthy foods. 9 The provision of early childhood education to children in low-income families and communities of color helps to reduce achievement gaps, improve the health of low-income students, and promote health equity. 10

“Health in All Policies” is an approach that incorporates health considerations into decision making across sectors and policy areas. 11 A Health in All Policies approach identifies the ways in which decisions in multiple sectors affect health, and how improved health can support the goals of these multiple sectors. It engages diverse partners and stakeholders to work together to promote health, equity, and sustainability, and simultaneously advance other goals such as promoting job creation and economic stability, transportation access and mobility, a strong agricultural system, and improved educational attainment. States and localities are utilizing the Health in All Policies approach through task forces and workgroups focused on bringing together leaders across agencies and the community to collaborate and prioritize a focus on health and health equity. 12 At the federal level, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the National Prevention Council, which brings together senior leadership from 20 federal departments, agencies, and offices, who worked with the Prevention Advisory Group, stakeholders, and the pubic to develop the National Prevention Strategy.

Place-based initiatives focus on implementing cross-sector strategies to improve health in neighborhoods or communities with poor health outcomes. There continues to be growing recognition of the relationship between neighborhoods and health, with zip code understood to be a stronger predictor of a person’s health than their genetic code. 13 A number of initiatives focus on implementing coordinated strategies across different sectors in neighborhoods with social, economic, and environmental barriers that lead to poor health outcomes and health disparities. For example, the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ) project focuses on children within a 100-block area in Central Harlem that had chronic disease and infant mortality rates that exceeded rates for many other sections of the city as well as high rates of poverty and unemployment. HCZ seeks to improve the educational, economic, and health outcomes of the community through a broad range of family-based, social service, and health programs.

Addressing Social Determinants in the Health Care System

In addition to the growing movement to incorporate health impact/outcome considerations into non-health policy areas, there are also emerging efforts to address non-medical, social determinants of health within the context of the health care delivery system. These include multi-payer federal and state initiatives, Medicaid initiatives led by states or by health plans, as well as provider-level activities focused on identifying and addressing the non-medical, social needs of their patients.

Federal and State Initiatives

In 2016, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which was established by the ACA, announced a new “Accountable Health Communities” model focused on connecting Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries with community services to address health-related social needs. The model provides funding to test whether systematically identifying and addressing the health-related social needs of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries through screening, referral, and community navigation services will affect health costs and reduce inpatient and outpatient utilization. In 2017, CMMI awarded 32 grants to organizations to participate in the model over a five-year period. Twelve awardees will provide navigation services to assist high-risk beneficiaries with accessing community services and 20 awardees will encourage partner alignment to ensure that community services are available and responsive to the needs of enrollees. 14

Through the CMMI State Innovation Models Initiative (SIM), a number of states are engaged in multi-payer delivery and payment reforms that include a focus on population health and recognize the role of social determinants. SIM is a CMMI initiative that provides financial and technical support to states for the development and testing of state-led, multi-payer health care payment and service delivery models that aim to improve health system performance, increase quality of care, and decrease costs. To date, the SIM initiative has awarded nearly $950 million in grants to over half of states to design and/or test innovative payment and delivery models. As part of the second round of SIM grant awards, states are required to develop a statewide plan to improve population health. States that received Round 2 grants are pursuing a variety of approaches to identify and prioritize population health needs; link clinical, public health, and community-based resources; and address social determinants of health.

- All 11 states that received Round 2 SIM testing grants plan to establish links between primary care and community-based organizations and social services. 15 For example, Ohio is using SIM funds, in part, to support a comprehensive primary care (CPC) program in which primary care providers connect patients with needed social services and community-based prevention programs. As of December 2017, 96 practices were participating in the CPC program. Connecticut’s SIM model seeks to promote an Advanced Medical Home model that will address the wide array of individuals’ needs, including environmental and socioeconomic factors that contribute to their ongoing health.

- A number of the states with Round 2 testing grants are creating local or regional entities to identify and address population health needs and establish links to community services. For example, Washington State established nine regional “Accountable Communities of Health,” which will bring together local stakeholders from multiple sectors to determine priorities for and implement regional health improvement projects. 16 Delaware plans to implement ten “Healthy Neighborhoods” across the state that will focus on priorities such as healthy lifestyles, maternal and child health, mental health and addiction, and chronic disease prevention and management. 17 Idaho is creating seven “Regional Health Collaboratives” through the state’s public health districts that will support local primary care practices in Patient-Centered Medical Home transformation and create formal referral and feedback protocols to link medical and social services providers. 18

- The Round 2 testing grant states also are pursuing a range of other activities focused on population health and social determinants. Some of these activities include using population health measures to qualify practices as medical homes or determine incentive payments, incorporating use of community health workers in care teams, and expanding data collection and analysis infrastructure focused on population health and social determinants of health. 19

Medicaid Initiatives

Delivery system and payment reform.

A number of delivery and payment reform initiatives within Medicaid include a focus on linking health care and social needs. In many cases, these efforts are part of the larger multi-payer SIM models noted above and may be part of Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers. 20 For example, Colorado and Oregon are implementing Medicaid payment and delivery models that provide care through regional entities that focus on integration of physical, behavioral, and social services as well as community engagement and collaboration.