What is self-plagiarism and what does it have to do with academic integrity?

Emerging trends series

By completing this form, you agree to Turnitin's Privacy Policy . Turnitin uses the information you provide to contact you with relevant information. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

Self-plagiarism—sometimes known as “ duplicate plagiarism ”—is a term for when a writer recycles work for a different assignment or publication and represents it as new.

For students, this may involve recycling an essay or large portions of text written for a prior course and resubmitting it to fulfill a different assignment in a different course. For researchers, this involves recycling prior published work and submitting it for publication to another journal without quotes or citation or acknowledgment of the prior work. Duplicate plagiarism, or “Submitting the same manuscript to multiple journals is widely considered unethical and would also likely constitute copyright infringement and violate the author-publisher contract of most journals” ( Moskowitz, 2021 ).

The broader act of recycling one’s own work in some areas like scientific research, which the Text Recycling Project expands upon, is more nuanced; in research, work is often cumulative and builds on prior research. In those cases, researchers may engage in developmental recycling, generative recycling, or adaptive publication to publish later work or revise the writing for a broader audience—all while citing prior publication ( Moskowitz, 2019 ).

Students who aren’t as familiar with this form of academic misconduct often don’t have a deeper understanding of academic integrity. Because they are reusing their own work, they may feel that this isn’t plagiarism or misconduct at all.

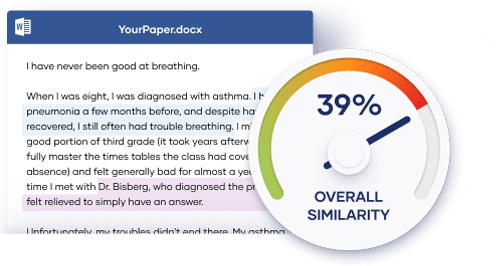

They may be stunned to find that they have, for instance, a higher similarity score when submitting to Turnitin, as it will match against a prior submission (their own). Students may then ask for that older paper to be deleted, not knowing they have engaged in duplicate plagiarism. In many cases, this is an opportunity to increase student understanding of academic integrity.

Academic integrity entails honesty and original work. But it also includes a deep understanding of the importance of citation and academic respect. Even if the paper is the student’s own, the work ought to be original for that particular assignment; duplicate plagiarism is a short-cut solution that hampers learning.

For researchers, duplicate plagiarism (wholesale republication of entire papers without citation) violates copyright and can affect the i mpact factor of both journals and researchers . A decrease in the impact factor detrimentally affects academic reputation and future publication possibilities.

While there are many instances of intentional duplicate plagiarism, most cases of self-plagiarism are unintentional and can be remedied with explicit instruction on the core principles of academic integrity, citation, and the prioritization of original work.

Many similarity check tools like iThenticate and Feedback Studio curtail self-plagiarism and also present learning opportunities to transform instances of plagiarism into teachable moments .

A more sophisticated understanding of academic integrity will help curtail self-plagiarism for both students and researchers. Researchers can mitigate the consequences of duplicate plagiarism by citing their previously published work. Having a deeper understanding of academic integrity avoids embarrassment and upholds learning as well as academic reputations.

Furthermore, designing assessments specific to your classroom can also help curtail self-plagiarism; when essay prompts are tailored to your classroom discussion, prior student work will likely not be relevant and be avoided.

We hope this post helps you on your academic integrity journey.

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is Self-Plagiarism, What is the Impact and How do you Avoid It?

- By Zebastian D.

- September 23, 2020

What Does Self-Plagiarism Mean?

Self-plagiarism is when you try to pass off all or a significant portion of work that you’ve previously done as something that is completely new.

What are Some Examples of Self-Plagiarism?

Examples of where you may be guilty of self-plagiarism are:

- Reusing the same set of data from a previous study or publication and not making this clear to the reader of your work.

- Submitting a piece of coursework, paper or other project work that you have already submitted elsewhere (e.g. for a different module).

- Writing up and submitting a manuscript for peer-review that has used the same data or drawn the same conclusions as work that you’ve already presented either in a previous publication or as a podium or poster presentation at a conference.

- Reusing the content of a literature review performed for one dissertation or thesis directly within another dissertation or thesis without referencing back to this.

You can see here that the theme is clear: if you give the impression that the work you’re submitting is completely new or original work, when in fact this is work you’ve previously presented, then this is self-plagiarism.

What can you do to avoid the risk of self-plagiarism?

If you’re an undergraduate or masters student, you may find yourself in a situation where the piece of coursework given to you is very similar or identical to work you’ve already done in the past. Avoid the temptation of resubmitting this previous work as something new.

Instead, seek out the advice of the lecturer or professor that has assigned the paper to you. Are they happy for you to build on the previous work you’ve done? If they are, make sure you appropriately reference your earlier work and be clear on what is genuinely new content in your current submission.

If you’re a PhD student, post-doc or any academic researcher, then be clear on what the journal you’re submitting to counts as self-plagiarism. Then be clear on whether or not they’ll allow this (with appropriate reference or citation to the previous work) or if they’re adamant that no level of self-plagiarism should occur. Note that this is normally different to self-citation of work.

Journals are likely to consider your submission if it has been presented at a conference only as a poster or podium talk. However, virtually all journals will not accept work that has previously been published in a different (or the same) peer-review journal.

Accidental plagiarism is not unusual, particularly if you’re using similar methods in your current research writing as you did previously. Some elements of text recycling can happen but it’s your responsibility as the author of the research paper to ensure that your publication is genuinely new work. If you do end up repeating text in your writing, make sure you give proper citation to this.

What Impact Could Self-Plagiarism Have on You?

Universities take all forms of plagiarism very seriously and the consequences of being caught doing this can be very severe, including being expelled from the university.

Some universities may view self-plagiarism (i.e. copying your own work) as less problematic than the form of plagiarism in which you copy the work of someone else and indeed, in some cases, they may even allow some level of self-plagiarism.

If they do allow it, then ensure you have the ok from the person that will be assessing your work (i.e. your professor). Please do not submit any work that you’ve already submitted before if you know your university does not allow self-plagiarism of any form.

If you’re an academic researcher, the consequences of being caught self-plagiarising your manuscript or paper may be at the very least a delay in your publication being accepted to, at worst, the manuscript being rejected altogether. If attempting to resubmit a duplicate publication already in one journal to another journal, you may also end up infringing on the journal’s copyright.

Beyond that, you may be accused of academic misconduct and even have your academic integrity called into question. Make sure that you as the author are clear on the plagiarism policy of the journal you’re submitting to and also be clear specifically on their rules on self-plagiarism.

Self-plagiarism can sometimes feel like a grey area, but you should be clear that resubmitting previously published work with the intention of passing it off as a completing new publication is not only poor academic practice but also scientific misconduct.

It’s ultimately your responsibility as the author of the research publication that you do not end up copying previously published material in your text. If you’re in any doubt about the rules surrounding self-plagiarism, then avoid the use of any duplicate publication in your material.

An In Press article is a paper that has been accepted for publication and is being prepared for print.

A thesis and dissertation appendix contains additional information which supports your main arguments. Find out what they should include and how to format them.

You’ve impressed the supervisor with your PhD application, now it’s time to ace your interview with these powerful body language tips.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

Tenure is a permanent position awarded to professors showing excellence in research and teaching. Find out more about the competitive position!

Choosing a good PhD supervisor will be paramount to your success as a PhD student, but what qualities should you be looking for? Read our post to find out.

Christine is entering the 4th year of her PhD Carleton University, researching worker’s experiences of the changing conditions in the Non Profit and Social Service sector, pre and during COVID-19.

Daniel is a third year PhD student at the University of York. His research is based around self-play training in multiagent systems; training AIs on a game such that they improve overtime.

Join Thousands of Students

Frequently asked questions

What is self-plagiarism.

Self-plagiarism means recycling work that you’ve previously published or submitted as an assignment. It’s considered academic dishonesty to present something as brand new when you’ve already gotten credit and perhaps feedback for it in the past.

If you want to refer to ideas or data from previous work, be sure to cite yourself.

If you’re concerned that you may have self-plagiarized, Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker can help you turn in your paper with confidence. It compares your work to unpublished or private documents that you upload, so you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarized.

Frequently asked questions: Plagiarism

Academic integrity means being honest, ethical, and thorough in your academic work. To maintain academic integrity, you should avoid misleading your readers about any part of your research and refrain from offenses like plagiarism and contract cheating, which are examples of academic misconduct.

Plagiarism is a form of theft, since it involves taking the words and ideas of others and passing them off as your own. As such, it’s academically dishonest and can have serious consequences .

Plagiarism also hinders the learning process, obscuring the sources of your ideas and usually resulting in bad writing. Even if you could get away with it, plagiarism harms your own learning.

Most online plagiarism checkers only have access to public databases, whose software doesn’t allow you to compare two documents for plagiarism.

However, in addition to our Plagiarism Checker , Scribbr also offers an Self-Plagiarism Checker . This is an add-on tool that lets you compare your paper with unpublished or private documents. This way you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarized or self-plagiarized .

Compare two sources for plagiarism

Most institutions have an internal database of previously submitted student papers. Turnitin can check for self-plagiarism by comparing your paper against this database. If you’ve reused parts of an assignment you already submitted, it will flag any similarities as potential plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers don’t have access to your institution’s database, so they can’t detect self-plagiarism of unpublished work. If you’re worried about accidentally self-plagiarizing, you can use Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker to upload your unpublished documents and check them for similarities.

Yes, reusing your own work without acknowledgment is considered self-plagiarism . This can range from re-submitting an entire assignment to reusing passages or data from something you’ve turned in previously without citing them.

Self-plagiarism often has the same consequences as other types of plagiarism . If you want to reuse content you wrote in the past, make sure to check your university’s policy or consult your professor.

If you are reusing content or data you used in a previous assignment, make sure to cite yourself. You can cite yourself just as you would cite any other source: simply follow the directions for that source type in the citation style you are using.

Keep in mind that reusing your previous work can be considered self-plagiarism , so make sure you ask your professor or consult your university’s handbook before doing so.

Common knowledge does not need to be cited. However, you should be extra careful when deciding what counts as common knowledge.

Common knowledge encompasses information that the average educated reader would accept as true without needing the extra validation of a source or citation.

Common knowledge should be widely known, undisputed and easily verified. When in doubt, always cite your sources.

Plagiarism has serious consequences , and can indeed be illegal in certain scenarios.

While most of the time plagiarism in an undergraduate setting is not illegal, plagiarism or self-plagiarism in a professional academic setting can lead to legal action, including copyright infringement and fraud. Many scholarly journals do not allow you to submit the same work to more than one journal, and if you do not credit a co-author, you could be legally defrauding them.

Even if you aren’t breaking the law, plagiarism can seriously impact your academic career. While the exact consequences of plagiarism vary by institution and severity, common consequences include: a lower grade, automatically failing a course, academic suspension or probation, or even expulsion.

Accidental plagiarism is one of the most common examples of plagiarism . Perhaps you forgot to cite a source, or paraphrased something a bit too closely. Maybe you can’t remember where you got an idea from, and aren’t totally sure if it’s original or not.

These all count as plagiarism, even though you didn’t do it on purpose. When in doubt, make sure you’re citing your sources . Also consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

Incremental plagiarism means inserting quotes, passages, or excerpts from other works into your assignment without properly citing the original source.

Even if the vast majority of the text is yours, including any content that isn’t without citing it is plagiarism.

Consider using a plagiarism checker yourself before submitting your work. Plagiarism checkers work by scanning your document, comparing it to a database of webpages and publications, and highlighting passages that appear similar to other texts.

Patchwork plagiarism (aka mosaic plagiarism) means copying phrases, passages, or ideas from various existing sources and combining them to create a new text. While this type of plagiarism is more insidious than simply copy-pasting directly from a source, plagiarism checkers like Turnitin’s can still easily detect it.

To avoid plagiarism in any form, remember to cite your sources . Also consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Verbatim plagiarism means copying text from a source and pasting it directly into your own document without giving proper credit.

Even if you delete a few words or replace them with synonyms, it still counts as verbatim plagiarism.

To use an author’s exact words, quote the original source by putting the copied text in quotation marks and including an in-text citation .

If you’re worried abotu plagiarism, consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Global plagiarism means taking an entire work written by someone else and passing it off as your own. This can mean getting someone else to write an essay or assignment for you, or submitting a text you found online as your own work.

Global plagiarism is the most serious type of plagiarism because it involves deliberately and directly lying about the authorship of a work. It can have severe consequences .

To ensure you aren’t accidentally plagiarizing, consider running your work through plagiarism checker tool prior to submission. These tools work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Plagiarism can be detected by your professor or readers if the tone, formatting, or style of your text is different in different parts of your paper, or if they’re familiar with the plagiarized source.

Many universities also use plagiarism detection software like Turnitin’s, which compares your text to a large database of other sources, flagging any similarities that come up.

It can be easier than you think to commit plagiarism by accident. Consider using a plagiarism checker prior to submitting your paper to ensure you haven’t missed any citations.

Some examples of plagiarism include:

- Copying and pasting a Wikipedia article into the body of an assignment

- Quoting a source without including a citation

- Not paraphrasing a source properly, such as maintaining wording too close to the original

- Forgetting to cite the source of an idea

The most surefire way to avoid plagiarism is to always cite your sources . When in doubt, cite!

If you’re concerned about plagiarism, consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission. Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

Plagiarism means presenting someone else’s work as your own without giving proper credit to the original author. In academic writing, plagiarism involves using words, ideas, or information from a source without including a citation .

Plagiarism can have serious consequences , even when it’s done accidentally. To avoid plagiarism, it’s important to keep track of your sources and cite them correctly.

Academic dishonesty can be intentional or unintentional, ranging from something as simple as claiming to have read something you didn’t to copying your neighbor’s answers on an exam.

You can commit academic dishonesty with the best of intentions, such as helping a friend cheat on a paper. Severe academic dishonesty can include buying a pre-written essay or the answers to a multiple-choice test, or falsifying a medical emergency to avoid taking a final exam.

Consequences of academic dishonesty depend on the severity of the offense and your institution’s policy. They can range from a warning for a first offense to a failing grade in a course to expulsion from your university.

For those in certain fields, such as nursing, engineering, or lab sciences, not learning fundamentals properly can directly impact the health and safety of others. For those working in academia or research, academic dishonesty impacts your professional reputation, leading others to doubt your future work.

Academic dishonesty refers to deceitful or misleading behavior in an academic setting. Academic dishonesty can occur intentionally or unintentionally, and varies in severity.

It can encompass paying for a pre-written essay, cheating on an exam, or committing plagiarism . It can also include helping others cheat, copying a friend’s homework answers, or even pretending to be sick to miss an exam.

Academic dishonesty doesn’t just occur in a classroom setting, but also in research and other academic-adjacent fields.

Paraphrasing without crediting the original author is a form of plagiarism , because you’re presenting someone else’s ideas as if they were your own.

However, paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you correctly cite the source . This means including an in-text citation and a full reference, formatted according to your required citation style .

As well as citing, make sure that any paraphrased text is completely rewritten in your own words.

Plagiarism means using someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as your own. Paraphrasing means putting someone else’s ideas in your own words.

So when does paraphrasing count as plagiarism?

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if you don’t properly credit the original author.

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if your text is too close to the original wording (even if you cite the source). If you directly copy a sentence or phrase, you should quote it instead.

- Paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you put the author’s ideas completely in your own words and properly cite the source .

Try our services

If you’ve properly paraphrased or quoted and correctly cited the source, you are not committing plagiarism.

However, the word correctly is vital. In order to avoid plagiarism , you must adhere to the guidelines of your citation style (e.g. APA or MLA ).

You can use the Scribbr Plagiarism Checker to make sure you haven’t missed any citations, while our Citation Checker ensures you’ve properly formatted your citations in APA style.

The consequences of plagiarism vary depending on the type of plagiarism and the context in which it occurs. For example, submitting a whole paper by someone else will have the most severe consequences, while accidental citation errors are considered less serious.

If you’re a student, then you might fail the course, be suspended or expelled, or be obligated to attend a workshop on plagiarism. It depends on whether it’s your first offense or you’ve done it before.

As an academic or professional, plagiarizing seriously damages your reputation. You might also lose your research funding or your job, and you could even face legal consequences for copyright infringement.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

- Skip to main content

We use cookies

Necessary cookies.

Necessary cookies enable core functionality. The website cannot function properly without these cookies, and can only be disabled by changing your browser preferences.

Analytics cookies

Analytical cookies help us improve our website. We use Google Analytics. All data is anonymised.

Hotjar and Clarity

Hotjar and Clarity help us to understand our users’ behaviour by visually representing their clicks, taps and scrolling. All data is anonymised.

Privacy policy

- Our research environment

- Support and Development for Postgraduate Researchers

- PGR Code of Practice

- Self-plagiarism

Defining Self Plagiarism

- University Regulation Regarding Plagiarism

- Copyright Issues Within Your Thesis

- Copyright Issues: Publishing After Your Thesis Is Submitted

- Self Plagiarism Q&A

- Additional Resources

Self-Plagiarism is defined as a type of plagiarism in which the writer republishes a work in its entirety or reuses portions of a previously written text while authoring a new work. Writers often maintain that because they are the authors, they can use the work again as they wish; they can’t really plagiarize themselves because they are not taking any words or ideas from someone else. But while the discussion continues on whether self-plagiarism is possible, the ethical issue of self-plagiarism is significant, especially because self-plagiarism can infringe upon a publisher’s copyright. Traditional definitions of plagiarism do not account for self-plagiarism, so writers may be unaware of the ethics and laws involved in reusing or repurposing texts.

Authors can quote from portions of other works with proper citations, but large portions of text, even quoted and cited can infringe on copyright and would not fall under copyright exceptions or “fair use” guidelines. The amount of text one can borrow under “fair use” is not specified, but the Chicago Manual of Style (2010) gives as a “rule of thumb, one should never quote more than a few contiguous paragraphs or stanzas at a time or let the quotations, even scattered, begin to overshadow the quoter’s own material” (pg. 146).

Ithenticate. The Ethics of Self-Plagiarism. ( White Paper) http://www.ithenticate.com/resources/papers/ethics-of-self-plagiarism . Viewed 06/08/2015.

Whereas plagiarism involves the presentation of others’ ideas, text, data, images, etc., as the products of our own creation, self-plagiarism, occurs when we decide to reuse in whole or in part our own previously disseminated ideas, text, data, etc without any indication of their prior dissemination. Perhaps the most commonly-known form of self-plagiarism is duplicate publication, but other forms exist and include redundant publication, augmented publication, also known as meat extender, and segmented publication, also known as salami, piecemeal, or fragmented publication. The key feature in all forms of self-plagiarism is the presence of significant overlap between publications and, most importantly, the absence of a clear indication as to the relationship between the various duplicates or related papers.

Miguel Roig. Plagiarism and self-plagiarism: What every author should know. Biochemia Medica 2010;20(3):295-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.11613/BM.2010.037

UCL Doctoral School

- Self-Plagiarism

Guidance on incorporating published work in your thesis

How you can include published work in your thesis and avoid self-plagiarism

Doctoral candidates who are worried about what they can include in their thesis can follow this guidance. It covers the inclusion of previously published papers and how to integrate them properly.

Publishing first, then submitting thesis for examination

If you've published before submitting your thesis:

- an appropriate citation of the original source in the relevant Chapter; and

- completing the UCL Research Paper Declaration form – this should be embedded after the Acknowledgments page in the thesis.

- Before using figures, table sheets, or parts of the text, find out from the editor of the journal if you transferred the copyrights when you submitted the paper.

- When in doubt, when you do not own copyright, get formal approval from copyright owners to re-use the material (this is frequently done for previously published data and figures to be included in a doctoral thesis; please see more information on the UCL Copyright advice website ).

- ensure the style matches that of the rest of the thesis, both in formatting and content,

- add additional information/context where beneficial, such as additional background/relevant literature, more detailed methods,

- offer additional data not included in the publication, such as preliminary data, null findings, anything included in supplementary materials.

- If you worked together with co-authors, your (and their) contributions to the publication should be specified in the UCL Research Paper Declaration form.

Examples of including previously published work in your thesis

After gaining approval from the copyright holder, you would be allowed to copy and paste sections from the published paper into your thesis.

You might make minor edits to the text to ensure that it fits the overall style of your thesis (e.g. changing “We” to “I”, where appropriate) and that it is written in your voice (see bullet point on ‘Initial drafts of papers’ below).

You might also incorporate additional text/figures/Tables that did not appear in the original publication.

Unacceptable

You cannot embed the unedited pdf of the published paper into your thesis.

You also cannot copy and paste the entire paper without making any attempt to match the style to the rest of the thesis.

Submitting thesis first (and the degree is successfully awarded) and published after

If your thesis is published first, then this must be declared to a journal publisher so that you can check with the editor about the acceptability of including part of your thesis.

You must make sure that you have cited the original source correctly (your thesis for example) and acknowledged yourself as author. Where possible, you could also provide a link.

This applies not just to reproducing your own material but also to ideas which you have previously published elsewhere.

Tips for reusing material in final thesis

We strongly recommend you write your upgrade document (and/or any progression documents) in the same style and format as you would your final thesis. This will help you plan the format of your final thesis early and you can then reuse as much of your upgrade material in your final thesis as makes sense.

Initial drafts of papers

We strongly recommend you keep your initial drafts of papers for use in your final thesis; this way it is written in your voice (not that of your supervisors, co-authors, or journal editor) and will be less likely to affect any copyright issues with the publisher. This does not mean you cannot incorporate supervisor corrections; however, all text should be written by you and not subject to vast rewriting/editing by others as is often the case with journal publications. You should still cite your published work where relevant.

Plan your thesis structure and project timings carefully from the start

This means considering thesis structure, time of upgrade/progression reviews, and, if appropriate, which chapters might be turned into publications and when.

Prioritise the thesis over any other priorities

Furthermore, as you approach the final months before your submission deadline (which you should check carefully with your supervisory team and funder as expectations may vary), we strongly encourage you to prioritise the thesis over any other conflicting priorities, e.g. internships, publications, etc…

Remember to follow these guidelines to ensure the appropriate use of published work in your doctoral thesis while avoiding self-plagiarism.

What is Self-Plagiarism

The UCL Academic Manual describes self-plagiarism as:

“The reproduction or resubmission of a student’s own work which has been submitted for assessment at UCL or any other institution. This does not include earlier formative drafts of the particular assessment, or instances where the department has explicitly permitted the re-use of formative assessments but does include all other formative work except where permitted.”

Read about this in more detail in Chapter 6, Section 9.2d of the UCL Academic Manual page .

How self-plagiarism applies to Doctoral Students

Re-use of material already used for a previous degree.

A research student commits self-plagiarism if they incorporate material (text, data, ideas) from a previous academic degree (e.g., Master's of Undergraduate) submission, whether at UCL or another institution, into their final these without explicit declaration.

Note on Upgrades

The upgrade report is not published nor is it used to confer a degree, and is therefore excluded from the above definition of “material”.

In effect, the upgrade report (and any other progression reviews) is a form of “thesis draft” owned by the student and we encourage the reuse of material in the upgrade report in the final thesis where relevant.

As a result, material written by yourself can be used both in publications and your final thesis, and the self-plagiarism rule does not apply here. However, since your final thesis will be ‘published’ online, there are several rules you must follow.

For additonal detail, visit the UCL Discovery web page .

Links to forms

UCL Research Paper Declaration Form for including published material in your thesis (to be embedded after the Acknowledgements page).

- Form in MS Word format (DOCX)

- Form in LaTeX format (TEX) , thanks to David Sheard, Dept of Mathematics

- Form in PDF preview (PDF)

Helpful resources

- Step-by-step guide and FAQs on publishing doctoral work

- Information about your own copyright

- Information on online copy of your thesis

Self-plagiarism in academic journal articles: from the perspectives of international editors-in-chief in editorial and COPE case

- Published: 08 February 2020

- Volume 123 , pages 299–319, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Wen-Yau Cathy Lin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4894-8031 1

3247 Accesses

10 Citations

22 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Scholarly misconduct causes significant impact on the academic community. To the extremes, results of scholarly misconduct could endanger public welfare as well as national security. Although self-plagiarism has drawn considerable amount of attention, it is still a controversial issue among different aspect of academic ethic related discussions. The main purpose of this study is to identify two concerns including what is self-plagiarism in academic journals, conceivable point of contention, based on journal editors’ viewpoint. Between 1990 and 2015, content of 57 editorials indexed in Scopus and WoS and 75 cases of self-plagiarism raised by international editors in COPE were analyzed to explore how journal editors identify these problems. The results show that self-plagiarism can be categorized to four facets, including its identification, types, norm, and remedy. And the editors are concerned about the issues about the detection software, salami-slicing and overlapping publication, the harm of copyright, and the retractions of published articles. Results from this study not only could obtain in-depth understandings on self-plagiarism among academic journal articles but also being applied on establishing academic guidelines in the future.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the american psychological association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Google Scholar

Anderson, M. S., & Steneck, N. H. (2011). The problem of plagiarism. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, 29 (1), 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.09.013 .

Article Google Scholar

Andreescu, L. (2013). Self-plagiarism in academic publishing: The anatomy of a misnomer. Science and Engineering Ethics, 19 (3), 775–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-012-9416-1 .

Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research . (2018). Retrieved from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-code-responsible-conduct-research-2018 .

Babalola, O., Grant-Kels, J. M., & Parish, L. C. (2012). Ethical dilemmas in journal publication. Clinics in Dermatology, 30 (2), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.06.013 .

Berlin, L. (2009). Plagiarism, salami slicing, and Lobachevsky. Skeletal Radiology, 38 (1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-008-0599-0 .

Berquist, T. H. (2013). Self-plagiarism: A growing problem in biomedical publication! American Journal of Roentgenology, 200 (2), 237. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.12.10327 .

BioMed Central. (2014a). Editorial policies: Text recycling . Retrieved from https://www.biomedcentral.com/getpublished/editorial-policies#text+recycling .

BioMed Central. (2014b). How to deal with text recycling. Retrieved from http://media.biomedcentral.com/content/editorial/BMC-text-recycling-editorial_guidelines.pdf .

Bird, S. (2002). Self-plagiarism and dual and redundant publications: What is the problem? Science and Engineering Ethics, 8 (4), 543–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-002-0007-4 .

Bretag, T., & Carapiet, S. (2007). A preliminary study to identify the extent of self-plagiarism in Australian academic research. Plagiary: Cross-Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication, and Falsification, 2, 92–103.

Broome, M. E. (2004). Self-plagiarism: Oxymoron, fair use, or scientific misconduct? Nursing Outlook, 52, 273–274.

Chrousos, G. P., Kalantaridou, S. N., Margioris, A. N., & Gravanis, A. (2012). The ‘self-plagiarism’ oxymoron: Can one steal from oneself? [editorial]. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 42 (3), 231–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2012.02645.x .

Code of Conduct for Scientists - Revised Version . (2013). Science Council of Japan. Retrieved from http://www.scj.go.jp/en/report/Code_of_Conduct_for_Scientists-Revised_version.pdf .

Code of Practice for Research: Promoting good practice and preventing misconduct . (2009). UK Research Integrity Office. Retrieved from http://www.ukrio.org/wp-content/uploads/UKRIO-Code-of-Practice-for-Research.pdf .

Collberg, C., & Kobourov, S. (2005). Self-plagiarism in computer science. Communications of the ACM, 48 (4), 88–94.

Collberg, C., Kobourov, S., Louie, J., & Slattery, T. (2003). SPlaT: A system for self-plagiarism detection. Paper presented at the IADIS international conference WWW/INTERNET Algarve, Portugal .

Committee on Publication Ethics. (2013). Text recycling guidelines. Retrieved December 30, 2013, from http://publicationethics.org/text-recycling-guidelines .

Cronin, B. (2013). Self-plagiarism: An odious oxymoron. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64 (5), 873. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22966 .

Dellavalle, R. P., Banks, M. A., & Ellis, J. I. (2007). Frequently asked questions regarding self-plagiarism: How to avoid recycling fraud. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 57 (3), 527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.05.018 .

European Science Foundation. (2017). The European code of conduct for research integrity . Retrieved from https://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf .

García-Romero, A., & Estrada-Lorenzo, J. (2014). A bibliometric analysis of plagiarism and self-plagiarism through Déjà vu. Scientometrics, 101 (1), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1387-3 .

Green, L. (2005). Reviewing the scourge of self-plagiarism. M/C Journal, 8 (5). Retrieved from http://journal.media-culture.org.au/0510/07-green.php .

Guidelines for the Conduct of Research in the Intramural Research Program at NIH . (2016). National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://oir.nih.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/sourcebook/documents/ethical_conduct/guidelines-conduct_research.pdf .

Halupa, C., & Bolliger, D. (2013). Faculty perceptions of student self plagiarism: An exploratory multi-university study. Journal of Academic Ethics, 11 (4), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-013-9195-6 .

Halupa, C., & Bolliger, D. (2015). Student perceptions of self-plagiarism: A multi-university exploratory study. Journal of Academic Ethics, 13 (1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-015-9228-4 .

Halupa, C., Breitenbach, E., & Anast, A. (2016). A Self-plagiarism intervention for doctoral students: A qualitative pilot study. Journal of Academic Ethics, 14 (3), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9262-x .

Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Horbach, S. P. J. M. S., & Halffman, W. W. (2019). The extent and causes of academic text recycling or ‘self-plagiarism’. Research Policy, 48 (2), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.09.004 .

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. (2016). Overlapping publications. Retrieved from http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/publishing-and-editorial-issues/overlapping-publications.html .

Kokol, P., Završnik, J., Železnik, D., & Vošner, H. B. (2016). Creating a self-plagiarism research topic typology through bibliometric visualisation. Journal of Academic Ethics, 14 (3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9258-6 .

Lancet. (2009). Self-plagiarism: Unintentional, harmless, or fraud? [editorial]. Lancet, 374 (9691), 664. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61536-1 .

Loui, M. C. (2002). Seven ways to plagiarize: Handling real allegations of research misconduct. Science and Engineering Ethics, 8, 2002.

Martin, B. R. (2013). Whither research integrity? Plagiarism, self-plagiarism and coercive citation in an age of research assessment. Research Policy, 42 (5), 1005–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.03.011 .

Ministry of Science and Technology. (2017). Academic ethics guidelines for researchers by the ministry of science and technology . Retrieved from https://www.most.gov.tw/most/attachments/3d81520a-b403-4603-b8ef-b191c38ce80c? .

Neville, C. W. (2005). Beware the consequences of citing self-plagiarism. Communications of the ACM, 48 (6), 13.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pierson, C. A. (2015). Salami slicing: How thin is the slice? Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27 (2), 65.

Plagiarism.org., glossary. Retrieved December 30, 2013, from http://www.plagiarism.org/plagiarism-101/glossary .

Roig, M. (2015). Avoiding plagiarism, self - plagiarism, and other questionable writing practices: A guide to ethical writing. Retrieved from https://bsc.ua.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/plagiarism-1.pdf .

Rosenzweig, M., & Schnitzer, A. E. (2013). Self-plagiarism: Perspectives for librarians. College and Research Libraries News, 74 (9), 492–494.

Rosing, C. K., & Cury, A. A. D. (2013). Self-plagiarism in scientific journals: An emerging discussion [editorial material]. Brazilian Oral Research, 27 (6), 451–452.

Samuelson, P. (1994). Self-plagiarism or fair use? Communications of the ACM, 37 (8), 2125.

Scanlon, P. M. (2007). Song from myself: An anatomy of self-plagiarism. Plagiary, 2, 1–10.

Sun, Y. C., & Yang, F. Y. (2015). Uncovering published authors’ text-borrowing practices: Paraphrasing strategies, sources, and self-plagiarism. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 20, 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.05.003 .

Text Recycling . Committee on publication ethics. Retrieved from http://publicationethics.org/files/u661/Text%20recycling_notes%20from%20Forum%20meeting_final.pdf .

Wager, E., Barbour, V., Yentis, S., & Kleinert, S. (2009). Retraction guidelines. Retrieved December 29, 2013, from http://publicationethics.org/files/retraction%20guidelines.pdf .

Zhang, Y., & Jia, X. (2012). A survey on the use of CrossCheck for detecting plagiarism in journal articles. Learned Publishing, 25 (4), 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1087/20120408 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under Grant No. MOST 103-2410-H-032-067.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Information and Library Science, Tamkang University, No. 151, Yingzhuan Rd., Tamsui Dist., New Taipei City, 25137, Taiwan

Wen-Yau Cathy Lin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wen-Yau Cathy Lin .

Appendix 1: List of editorials containing self-plagiarism-related articles

- a Non-medical discipline journals

Appendix 2: List of self-plagiarism issues covered by the COPE cases

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lin, WY.C. Self-plagiarism in academic journal articles: from the perspectives of international editors-in-chief in editorial and COPE case. Scientometrics 123 , 299–319 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03373-0

Download citation

Received : 24 August 2019

Published : 08 February 2020

Issue Date : April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03373-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-plagiarism

- Academic journal

- Redundant publication

- Overlapping publication

- Research ethics

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Prevent plagiarism, run a free plagiarism check.

- Knowledge Base

- What Is Self-Plagiarism? | Definition & How to Avoid It

What Is Self-Plagiarism? | Definition & How to Avoid It

Published on 9 December 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on 26 July 2022.

Plagiarism often involves using someone else’s words or ideas without proper citation , but you can also plagiarise yourself. Self-plagiarism means reusing work that you have already published or submitted for a class. It can involve:

- Resubmitting an entire paper

- Copying or paraphrasing passages from your previous work

- Recycling previously collected data

- Separately publishing multiple articles about the same research

Self-plagiarism misleads your readers by presenting previous work as completely new and original. If you want to include any text, ideas, or data that you already submitted in a previous assignment, be sure to inform your readers by citing yourself .

Table of contents

Examples of self-plagiarism, why is self-plagiarism wrong, how to cite yourself, how do educational institutions detect self-plagiarism, frequently asked questions about plagiarism.

You may be committing self-plagiarism if you:

- Submit an assignment from a previous academic year to a current class

- Recycle parts of an old assignment without citing it (e.g., copy-pasting sections or paragraphs from previously submitted work)

- Use a dataset from a previous study (published or not) without letting your reader know

- Submit a manuscript for publication containing data, conclusions, or passages that have already been published without citing your previous publication

- Publish multiple similar papers about the same study in different journals

Examples: Self-plagiarism

- Reusing text from previous papers

- Simultaneous submission

- Recycling data

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

While self-plagiarism may not be considered as serious as plagiarising someone else’s work, it’s still a form of academic dishonesty and can have the same consequences as other forms of plagiarism. Self-plagiarism:

- Shows a lack of interest in producing new work

- Can involve copyright infringement if you reuse published work

- Means you’re not making a new and original contribution to knowledge

- Undermines academic integrity, as you’re misrepresenting your research

It can still be legitimate to reuse your previous work in some contexts, but you need to acknowledge you’re doing so by citing yourself.

It can be legitimate to reuse pieces of your previous work, but you need to ensure you have explicit permission from your instructor before doing so, and you must cite yourself .

You can cite yourself just like you would cite any other source. The examples below show how you could cite your own unpublished thesis or dissertation in various styles.

Example: Citing an unpublished thesis or dissertation

- Chicago style

In addition to plagiarism software databases, many educational institutions keep databases of submitted assignments. Sometimes, they even have access to databases at other institutions. If you hand in even a portion of an old assignment a second time, the plagiarism software will flag it as self-plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers not affiliated with a university don’t have access to the internal databases of educational institutions, and therefore their software cannot check your document for self-plagiarism.

In addition to our Plagiarism Checker, Scribbr also offers a Self-Plagiarism Checker . This unique tool allows you to upload your own original sources and compare them with your new assignment. It will flag any unintentional self-plagiarism, in addition to other forms of plagiarism, and helps ensure that you add the correct citations before submitting your assignment.

Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker

Online plagiarism scanners do not have access to internal university databases, and therefore cannot check your document for self-plagiarism.

Using Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker , you can upload your previous work and compare it to your current document:

- Your thesis or dissertation

- Your papers or essays

- Any other published or unpublished documents

The checker will scan the texts for similarities and flag any passages where you might have self-plagiarised.

Yes, reusing your own work without citation is considered self-plagiarism . This can range from resubmitting an entire assignment to reusing passages or data from something you’ve handed in previously.

Self-plagiarism often has the same consequences as other types of plagiarism . If you want to reuse content you wrote in the past, make sure to check your university’s policy or consult your professor.

If you are reusing content or data you used in a previous assignment, make sure to cite yourself. You can cite yourself the same way you would cite any other source: simply follow the directions for the citation style you are using.

Keep in mind that reusing prior content can be considered self-plagiarism , so make sure you ask your instructor or consult your university’s handbook prior to doing so.

Most institutions have an internal database of previously submitted student assignments. Turnitin can check for self-plagiarism by comparing your paper against this database. If you’ve reused parts of an assignment you already submitted, it will flag any similarities as potential plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers don’t have access to your institution’s database, so they can’t detect self-plagiarism of unpublished work. If you’re worried about accidentally self-plagiarising, you can use Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker to upload your unpublished documents and check them for similarities.

The consequences of plagiarism vary depending on the type of plagiarism and the context in which it occurs. For example, submitting a whole paper by someone else will have the most severe consequences, while accidental citation errors are considered less serious.

If you’re a student, then you might fail the course, be suspended or expelled, or be obligated to attend a workshop on plagiarism. It depends on whether it’s your first offence or you’ve done it before.

As an academic or professional, plagiarising seriously damages your reputation. You might also lose your research funding or your job, and you could even face legal consequences for copyright infringement.

Most online plagiarism checkers only have access to public databases, whose software doesn’t allow you to compare two documents for plagiarism.

However, in addition to our Plagiarism Checker , Scribbr also offers an Self-Plagiarism Checker . This is an add-on tool that lets you compare your paper with unpublished or private documents. This way you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarised or self-plagiarised .

Compare two sources for plagiarism

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, July 26). What Is Self-Plagiarism? | Definition & How to Avoid It. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/preventing-plagiarism/self-plagiarism/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, the 5 types of plagiarism | explanations & examples, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, consequences of mild, moderate & severe plagiarism.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Bosn J Basic Med Sci

- v.13(3); 2013 Aug

Plagiarism and Self-plagiarism

Plagiarism is unauthorized appropriation of other people’s ideas, processes or text without giving correct credit and with intention to present it as own property. Appropriation of own published ideas or text and passing it as original is denominated self-plagiarism and considered as bad as plagiarism. The frequency of plagiarism is increasing and development of information and communication technologies facilitates it, but simultaneously, thanks to the same technology, plagiarism detection software is developing[ 1 ].

Within academia, plagiarism by students, professors, or researchers is considered academic dishonesty or academic fraud, and offenders are punished by sanctions ranging from suspension to termination, along with the loss of credibility and perceived integrity[ 2 ].

When we talking about self-plagiarism avid B. Resnik clarifies, “Self-plagiarism involves dishonesty but not intellectual theft[ 3 ].” Roig (2002)[ 4 ] offers a useful classification system including four types of self-plagiarism:

- - duplicate publication of an article in more than one journal;

- - partitioning of one study into multiple publications, often called salami-slicing;

- - text recycling; and

- - copyright infringement.

In cases of proven plagiarism and academic self-plagiarism consequences may include[ 5 ]:

- - The author is obliged to withdraw the disputable manuscript which is already published or in different pre-publication stages.

- - In the event of co-authorship, the co-author must approve of publication withdrawal, even if the misconduct is not related to them.

- - Publications proved to be false by the Commission are erased from author’s bibliography or marked appropriately.

- - The procedure for detraction from academic degrees (MSc or PhD) at the University is initiated if obtained based on false thesis or dissertation.

- - The procedure for detraction from scientific and educational titles is initiated by a relevant body if based on false publications or other inappropriate way.

- - Scientific institutions, organizations and other relevant institutions are informed, especially those financing scientific projects, about scientific misconduct if they are directly related or in the event that the incriminated scientist works in a leading position or as a member of any decision-making body.

Withdrawal of scientific articles published in journals is becoming more common. Similar experiences recorded by one blog, Retraction Watch[ 6 ], which a year and a half follows the withdrawal of articles and consequences for the authors of these articles: from the prohibition of the publication to the dismissal from work.

Editor in Chief

Professor Bakir Mehić MD, PhD

Self-Plagiarism Q & A

Self-plagiarism Webcast »

SELF-PLAGIARISM Q&A FORUM

This page includes the Q&A portion of the webcast titled, "What's Mine is Mine: Self-plagiarism, Ownership and Author Responsiblity," which featured Rachael Lammey from CrossRef, Kelly McBride from Poynter and Jonathan Bailey from Plagiarism Today. Bob Creutz, Executive Director of iThenticate, joins the panel in providing responses to questions that were asked during the webcast.

Question about self-plagiarism? Ask the experts!

20 Q&A's about Self-plagiarism

Q1: "i asked about the difference between duplicate publication and self-plagiarism. i think the moderator kind of addressed that with asking the speakers to define self-plagiarism, but they didn't answer with respect to duplicate publication. they seem similar, but self-plagiarism is a somewhat expanded definition that isn't really addressed by icmje and gpp2.".

A: (Rachael) Here’s a really good link to an article in Biochemica Medica called ‘Plagiarism and self-plagiarism: what every author should know’. It goes into detail on the different types of self-plagiarism, duplicate publication being one of them: www.biochemia-medica.com/content/plagiarism-and-self-plagiarism-what-every-author-should-know

Q2: "Under what conditions an author can use some part of his/her previously published research article in his/her next research article?"

A: (Rachael) I think the key thing is making sure that you reference the previous work that you’re using correctly. Make it clear to anyone reading your paper which parts of your work have been published previously and where. Also, check with the particular publication you’re submitting to in case they have a specific policy to this effect. Here’s an example from the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) that reflects the policy for their titles: www.acm.org/publications/policies/plagiarism_policy . If you look at the second paragraph you’ll see that the text does not need to be quoted, but does need to be cited. Many publishers have policies such as this so it’s always worth checking those to see how best to reference your previously published work.

Q3: "Let’s say I am working on the same topic and write three papers. When writing the literature review of the second and third paper I am reusing some parts of the previous literature reviews and citing my previous work. Is this self-plagiarism?"

A: (Rachael) Again, I’d say check the publisher policy (or, if it’s not clear email them) but as long as you ensure that you’re citing your previous work and making it clear to anyone reading it that the material isn’t ‘new’ then you would avoid being accused of passing material off as new when it has already been used.

Q 4: "What is the difference between duplicate publication and self-plagiarism?"

A: (Rachael) See link in answer to Q1: duplicate publication is a type of self-plagiarism.

Q5: "As an author, where do I access policy and guidelines around what constitutes self-plagiarism?"

A: (Rachael) Most publishers have their own policies on self-plagiarism - I’d look to the author resources for the publisher you want to submit your research to for information. So here are some examples, you’ve seen the ACM one above, and there’s a policy from Nature here: www.nature.com/authors/policies/plagiarism.html . In fact, there are a series of really useful links on this page: www3.imperial.ac.uk/library/researchers/plagiarismdetection that will provide guidelines on self-plagiarism and how to think about citing your work so you can provide clarity for readers.

Q6: "If a scientist is describing a method that is used in different papers, can they use that same description?"

A: (Bob) Anecdotal feedback from CrossCheck members indicates that editors are largely unconcerned with plagiarism in method sections. In fact, it has been requested that iThenticate includes a feature that excludes methods from originality check.

(Rachael) I’d agree with Bob. An Editor reading the paper as a subject specialist will understand that there will necessarily be a degree of overlap/the same methods section if the same method has been used.

Q7: "What if someone do self-plagiarism few years ago but he wants to remove it?"

A: (Bob) Authors can request that publishers retract articles.

(Rachael) Yes, they can contact the publisher to request that the article be retracted or ask the publisher for advice.

Q8: "Is it right to considered different forms of self-plagiarism? Which might they be?"

A: (Rachael) See answer to Q1 and also the resource mentioned in Q5 for descriptions of different forms of self-plagiarism.

Q9: "Let’s say I am working on the same topic and write three papers. When writing the literature review of the second and third paper I am reusing some parts of the previous literature review papers and citing my previous work. Is this self-plagiarism?"

A: (Rachael) Same as Q3.

Q10: "When is it too much? What is the threshold of reusing info? 80% new ration to 20% reused? Or the other way around? How does the editor work with the author? Is it just a matter of reworking the references OR are there sanctions for the author? How do you determine intent?"

A: (Rachael) Every journal is a little different as it is often up to the Editor’s discretion as to what they’re looking for in a paper. If you are re-using a lot of text, then it’s always best to make it clear in your paper what is new about this version or why/how it differs from your previous work. Again, it’s always important to reference your previous work clearly in the paper. If you reference/cite as per the journal or publisher instructions then they will be able to see that your intent is not to mislead. Intent is almost impossible to prove, so many editors may un-submit the paper and ask for it to be properly referenced if they think that it is not or let the author provide additional information to clarify how the work has been used previously. It is unlikely that sanctions would be taken against an author in a case such as this, especially if the author co-operated with the Editor in providing the additional information requested.

Q11: "If someone else got published a part of your research with his own name, what can you do?"

A: (Rachael) I would contact the publisher who has published the work and provide the information you can on how your research has been appropriated by the other author. They should have a procedure that they can follow in order to follow-up on your concerns.

Q12: "Does the medium matter? If one has written a book, and later draws from that work for a newspaper column, for example, does this equate to self-plagiarism?"

A: (Rachael) I’d check with the newspaper what their policy is, but if you reference the book correctly then that will help provide clarity for readers.

Q13: "Is it self-plag. if there are some common data in a full paper and letter and conference paper?"

A: (Rachael) A lot of publishers will have their own policies on this and on re-using information from conference papers, so I would always check with them. Most are fine with authors re-using their own work in this way, but it’s best to check with them how to present it first.

Q14: "Is it legitimate to publish journal publications and re-use the information for the PhD thesis with a reference to the publication?"

A: (Rachael) This is normally fine - it falls a little under copyright. So if you publish in a journal, you will have to sign a copyright form. Check this form and the publisher’s copyright policy. Most will be fine with you re-using the information in a PhD thesis as it is not for commercial use, but it is always best to double check. And yes, you will need to make reference to the publication.

Q15: "Are there certain content pieces where self-plagiarism is more acceptable? ie Turning a PhD dissertation into a book, review article, annual update?"

A: (Rachael) Normally self-plagiarism refers to work that has already been published. If your PhD dissertation has been published then the policies described by the publisher would apply in terms of referencing etc. I’d always check with the publisher to be sure as depending on the subject area different approaches may apply to different content pieces.

Q16: "What happened with me is that I sent my research article for publication based on my PhD work, similarity report showed that someone has copied my work and got it published with his own name. What should I do in such situation?"

A: (Rachael) See answer to Q11.

Q17: "We upset terribly an author when we asked him to rewrite two self-plagiarised paragraphs in a manuscripts. He was so angry he was so angry he withdrew the manuscript immediately. Any hints on how to negate that situation?"

A: (Rachael) I agree that this is tricky. Many publishers/journals have standard letters that they use in cases where they want the author to either reference or re-write pieces of their work. Some authors will be pleased for the help, some might never resubmit and some might come back angrily and sadly I think that’s the case no matter how carefully you phrase the letter to them. I would ask your publisher if they do have any text you can use (and adapt to make specific to your publication) and if you treat each author who you need to contact in the same fashion then I think that’s all you can do.

Q18: What is exactly "black list"? Can plagiarism in a publisher cause black list in all the publishers? Or it is just related to each publisher?

A: (Rachael) There is a lot of discussion around follow-up actions with authors and it’s something that I would urge caution in doing. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) has a case regarding this: http://publicationethics.org/case/duplicate-publication-6 and they would always advise against black-listing authors as such an approach can lead to legal difficulties. If a journal or number of journals have had issues with an author then you will tend to remember them when they next come to submit, but realistically black-listing is difficult to enforce (i.e. the author could just come and resubmit under a different email address) and it can risk legal action against the publisher.

Q19: "Is it self-plagiarism if there are some common data in different works?"

A: (Kelly) From my point of view, self-plagiarism is limited to just the actual words and not the ideas, making it acceptable to reuse such content as long as nothing was copied verbatim.

Q20: "What should someone do if they want to correct an instance of self-plagiarism in their past?"

A: (Kelly) noted that, if it’s online, it’s trivial to edit the work or add a note to it for a correction. However, with printed works, it’s a much more difficult situation. This was echoed by Jonathan who noted nothing is set in stone on the Web but that with print, while there is a correction or a retraction policy, it often feels inappropriate to really address the issue as it may either be inadequate or too extreme depending upon the nature of the self-plagiarism.

Self-plagiarism webcast highlights (PDF)

The Ethics of Self-plagiarism (PDF)

For Instructors:

For Students:

For Educational Resources:

- Plagiarism: What Counts as Cheating?

Cheating has become that much more ubiquitous with the explosive popularity of the internet across the past couple decades. Countless students have been caught plagiarizing papers. However, there is a question as to what, exactly, qualifies as cheating. Plagiarizing has the potential to result in a lengthy suspension or even permanent expulsion. Every single student should clearly understand what constitutes cheating.

Because of this, c ountless students have been caught plagiarizing papers. However, there is a question as to what, exactly, qualifies as cheating . Plagiarizing has the potential to result in a lengthy suspension or even permanent expulsion. Every single student should clearly understand what constitutes cheating, and know that DC Student Defense is here to help if they are accused of cheating or plagiarizing.

Defining Plagiarism

Plagiarism is the use of another person’s ideas or words in one’s work while attempting to pass them off as original work. In fact, the definition of plagiarism even extends to self-plagiarism . If you re-use your marked work in an unauthorized manner, it is possible you will be accused of self-plagiarism. However, the most common occurrence of plagiarism is related to the use of texts, words and ideas published by others on the web, in books and other materials, without proper citation . Even using another student’s work or translating a text from another source without citing that source appropriately constitutes plagiarism.

Understand Your Academic Institution’s Plagiarism Rules

The rules pertaining to the type of content that can and cannot be used for guidance/inspiration differ by each unique academic institution as well as the course and course module in question. Do not assume the rules from your middle school or high school education will prove applicable to your post-secondary institution. Pinpoint the exact rules that apply to the assignment or course you are currently working on. Information pertaining to such rules should be made readily available through the student handbook, the individual class professor or the teaching assistant. Read through the entirety of these rules before commencing work on any particular project. The bottom line is it is your responsibility as a student to understand your academic institution’s nuanced plagiarism rules .

How to Avoid Plagiarism

Aside from learning about your academic institution’s idiosyncratic plagiarism rules, you should also get into the habit of stating sources used. When in doubt, list more sources than you assume are necessary. Always put quotation marks around portions of text taken from a source. Even if you are quoting an essay or another work you created, you should still use quotation marks and cite your own work as your source.

You can avoid accusations of plagiarism by refusing to use another student’s work or anyone else’s work as a model for your own work. In fact, it is even risky to use another’s work as inspiration when completing your own essays, summaries and other work. Something as subtle as simply re-wording parts of text used from the original when creating your own work dramatically hikes the chances of a plagiarism accusation.

Plagiarism Can Be Stolen Words or Ideas

United States law states it is possible for ideas and words to be stolen. The expression of an original idea constitutes intellectual property and therefore, is protected by copyright laws. This means one’s original ideas are similar to original inventions. Nearly every form of expression falls under the umbrella of copyright protection. However, the form of expression in question must be recorded in some manner, be it in the form of a book, website, computer file, etc.

Specific Examples of Plagiarism

If you turn in another person’s work and claim it is your own, you have plagiarized. Furthermore, copying ideas or words from another source without citing those sources constitutes plagiarism. The failure to put quotes in quotation marks also constitutes plagiarism. Even altering the order of words constitutes plagiarism if the source’s sentence structure is copied without providing the proper credit. In fact, it is possible to be found guilty of plagiarism when providing false information about the source of a string of words or source of a quotation used in one’s work.

Accused of Plagiarism? You Deserve a Strategic Legal Defense

If you are accused of plagiarism, do not assume you will be suspended or expelled.

Latest Posts

- More Than Meets the Eye: NJ Supreme Court Cardali Decision’s New Methodology Can Prevent Judicial Backlog and Increased Costs

- VASPA Creates More Access for Victims of Stalking and Cyber Harassment

- [Webinar] Cultivating and Sustaining Title IX Advisors - March 6th, 12:00 pm - 1:00 pm ET

- An SBA Public Service Announcement: If You See Something, Say Something

See more »

DISCLAIMER: Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

Refine your interests »

Written by:

Published In:

Cohen seglias pallas greenhall & furman pc on:.

"My best business intelligence, in one easy email…"

- Share full article

Advertisement

Subscriber-only Newsletter

The Ethicist

Should i confront our former minister over his plagiarized sermons.

The magazine’s Ethicist columnist on grace, intellectual property, and pastorly accountability.

By Kwame Anthony Appiah

I have an ethical problem, or rather, the retired minister of my church has one, and I don’t know what to do about it. After his retirement several years ago, some of us decided to gather his sermons from the past 10 years or so into a bound volume and present it to him. We would also put one into our library and make the digital version available on the members-only part of our website. We set out to work on proofing the sermons for typos, grammatical errors and missing citations.

Then we discovered something egregious: He had “borrowed” great swaths of text from stories, articles and online writing and presented them as his own. One example involved an amusing story that just happened to be lifted nearly whole from an Eat column in this very magazine. There was a very moving account of his visit to a local monastery, taken almost verbatim from an article — only the name and location of the monastery were changed. On and on it went, with as many as five or more instances of plagiarism in every single sermon.

He always presented himself as an erudite, eloquent writer; his sermons could be mesmerizing and inspiring. As a fellow writer, I was impressed by the depth and breadth of his reading.

Now the proofers know that he was not just reading but also trolling for copy. We are aghast. We are also near the end of the project. I presented our findings to the president of our board, who considers him a friend. Her advice was to stop the proofing, make just one bound copy (for our retired minister, not our library) and send the digital version only to those who requested it. We are also removing any of the footnotes we made directing people to a “similar” (ahem) article or story that he plundered. Some might discover his theft if they follow these publications, but most will not.

While this work would allow the project to be finished and presented to both our former minister and the congregation, I feel more and more unwilling to let his plagiarism slide. I want to tell him what we found. I would write only to him, and would not say a word to anyone else at the church. I do not want to shame him publicly, but I do want him to know that the small group who read and researched them with great care is aware of what he did, and is appalled. Perhaps I would use a less damning word — “disappointed”?

His actions make those of us who respected and admired him look like fools, especially because he’s a man of the cloth. But those of us who know what he did are not without compassion. He is elderly and has an ailing spouse. He is very proud of his years as a pastor. Should I tell him I know? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist: