Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 10 Ways to Write a Survey Research Proposal with Samples and Examples

Mohammed Sameer

Research proposals are nerve-racking, notoriously challenging to write, and can skyrocket your academic career. Does that sound frightening? You bet! This blog will assist you in writing an effective survey research proposal .

The biggest challenge of actualizing a well-thought-out survey research proposal is “no funding.”

How will you persuade decision-makers to fund your research? Your quick answer: A survey research proposal template. The problem is…

You cannot just write a proposal; it must be flawless, especially now that the world has reopened and thousands of talented researchers are competing for positions.

How do you craft a proposal to help you outperform the competition? Spend 10 minutes reading this blog, and you'll know how to do it.

Before we sprint to the heart of the subject, let's establish some basics.

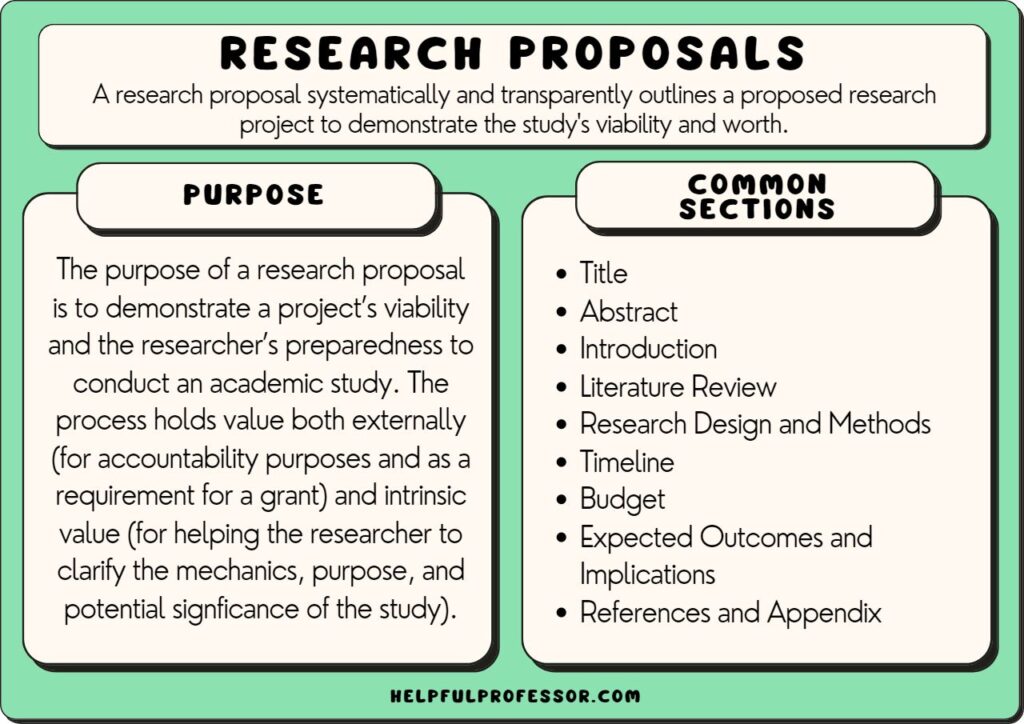

What is a Research Proposal?

A research proposal is a formal educational document. It outlines your research project and requests funding or agreement to supervise your project.

The primary goal of a research proposal is to explain what you intend to study and why it is worth looking into. Most research proposals are used in academia or by non-academic scientific organizations.

Of course, no two research proposals are the same, and they can vary greatly depending on your study level, field, or project specifics.

Still, there are certain general requirements that all significant proposals must meet, and the format that is non-negotiable.

Alright, we finished the theoretical part. It's time to get some practice!

Here's How to Write a Survey Research Proposal With Templates

1. write an introduction to present the subject of your research.

"Wow, I cannot wait to see how this study turns out!"

This is the type of response you want for your research proposal introduction.

How can that be accomplished? Structure your research proposal introduction around the following four key issues:

- What is the research question?

- Who is this issue important to (the general public, fellow researchers, specialized professionals, etc.)?

- What is currently known about the problem, and what key pieces of information are missing?

- Why should anyone be concerned about the outcomes?

The simplest way to write an engaging introduction to a research proposal is to use our pre-designed PPT Template.

Sample Survey Research Proposal Template

2. Explain the Context and Background

This section is optional, depending on how detailed your proposal is. It is usually added if the research problem at hand is complex. It is titled "Background and Importance" or "Rationale."

The introduction will include most of the factual background for shorter proposals.

How do you write the "Background" section of a research proposal?

- Describe the broader research area in which your project fits.

- Emphasize the gaps in existing studies and explain why they must be filled.

- Demonstrate how your research will add to existing knowledge.

- Explain your hypothesis and its rationale.

- Determine the scope of your research (in other words, explain what the research is not about).

- Finally, showcase the significance of your research and the benefits it can provide. In other words, respond to the dreaded "So what?" question.

If your research project is technical and complex, describing the background in a separate section is especially beneficial. It makes your introduction follow a free-flowing, "significant" narrative while letting the "Background" section do the heavy lifting.

If you encounter profound scientific discoveries while conducting your research, you’ll need additional help highlighting them. Here are the top 25 scientific PPT Templates to present your new findings .

3. Provide a Detailed Literature Review

The most critical (and the most challenging) section of the entire document is tackled here.

One in which you must demonstrate that you know everything there is to know about your subject of interest and that your research will help advance the entire field of study.

The section on Literature Review is essentially a mini-dissertation. It must follow a logical progression and present the case for your study about previous research: Explain and summarize what has already been discussed, and show that your research goes beyond that.

If there are some statistics you want to highlight here, you’ll need these 25 ways to show statistics in a presentation .

It may be difficult to discuss all the existing research on your subject in the Literature Review. In today's digital age of easy access to information, be selective about which studies or papers you include.

The difficult part? DONE. (No, it truly is.) Everything that follows is a matter of formalities and technicalities. If they're already sold onto your vision, you must show them how you intend to accomplish your goals.

4. List Your Key Aims and Objectives

This section is called "Research Questions" or "Aims and Objectives." It should be brief compared to the previous slides.

The formal requirements of the institution you're applying to dictate:

- Whether you need to write about your goals and objectives, or

- Formulate them as research questions.

The key to mastering this section is distinguishing between an aim, an objective, and a research question.

Here's another practical example to help you understand.

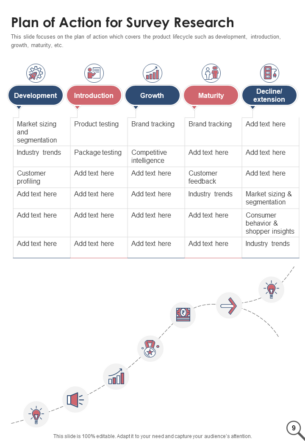

5. Outline the Research Methods and Design

The funding authorities already know what you're attempting to accomplish and have a general idea of how you intend to deliver results. This section demonstrates that you are adequately prepared (in terms of both skills and resources) to conduct the research.

The principal goal is to persuade the reader that your methods are suitable and appropriate for the specific topic.

Do you know why "specific" is in bold? It is one of the parts of a research proposal that varies the most between documents. There is an ideal methodology for every academic project, and no two research designs are alike. Check that your methodology corresponds to all of your desired outcomes.

After all, you know your project better than anyone else. You'll have to make a decision about which methods are best.

You can support your bet with an effective fact sheet you can build using these top 15 PPT Templates .

Here’s a sample template for you.

6. Discuss Ethical Considerations

No, this is not an optional step. If you're researching the vector shapes of tree leaf shadows (yes, it's a legitimate research topic), there won't be many ethical issues to consider.

However, if your research involves humans, particularly in fields such as medicine or psychology, ethical issues are bound to arise.

You must take extra precautions to protect your participants' rights, obtain their explicit consent to process data, and consult the research project with the authorities of your academic institution. For this purpose, your proposal must include detailed information on these topics.

7. Present Preliminary or Desired Implications and Contribution to Knowledge

It is the final argument in your proposal to persuade decision-makers to support your project. You've already stated what the scope of your project will be. You have described the current state of knowledge and highlighted the most significant gaps. You have told them what you want to learn and how you intend to do it.

Now, discuss the actual, measurable difference your discovery can make and how your research can impact the future of the field or even a specific niche.

8. Detail Your Budget and Funding Requirements

If you already have a supervisor (s), you should discuss this section with them. They've most likely submitted similar documents to the institution you're contacting. They can also provide insights into how much you can realistically expect to be paid.

Note: If possible, leave yourself some wiggle room and request a conditional extra allowance.

9. Provide a Timetable

Detailing a timeline in a proposal for a standalone project can help support your budget. The most common format is, as you might expect, a table. Divide your research into stages, list the actions you'll need to take at each stage in bullet points, and set tentative deadlines.

It prevents you from derailing your project.

We have an editable TOC template you can use to define your timetable.

10. End with a List of Citations

Citations in research proposals can take the form of references (which include only the pieces of literature you cited) or a bibliography (everything that you consulted for your proposal).

Double-check with them or consult your supervisor on the format.

The same is true for referencing style. Most universities in the United States use APA or Chicago Style, but each has its own set of rules and preferences. Check the list of guidelines on their website for confirmation. When in doubt, contact the head of the department with which you want to work.

Here’s an editable template you can use to include citations.

FAQs on Survey Research Proposal

What is an example of survey research.

Assume a researcher wants to learn about teenagers' eating habits. In that case, they will follow a group of teenagers for an extended period to ensure that the data gathered is reliable. A longitudinal study is frequently followed by cross-sectional survey research.

In a longitudinal study, researchers examine the same individuals repeatedly to detect any changes that may occur over time. Longitudinal studies are essentially correlational research in which researchers observe and collect data on several variables without attempting to influence them.

A cross-sectional study is a type of research design where data is collected from many people at once. In cross-sectional research, variables are observed without being influenced.

What should a survey proposal include?

The proposal should present your research methodology, with specific examples demonstrating how you will conduct your research (e.g., techniques, sample size, target populations, equipment, data analysis, etc.). Your methods could include going to specific libraries or archives, fieldwork, or conducting interviews.

What are the three types of survey research?

Most research can be classified into three types: exploratory , descriptive , and causal . Each serves a distinct purpose and can only be used in specific ways.

Exploratory Research

Any marketing or business strategy should include exploratory research. Its emphasis is on the discovery of ideas and insights rather than the collection of statistically accurate data. As a result, exploratory research is best suited as the first step in your overall research plan. It is most commonly used to define company issues, potential growth areas, alternative courses of action, and prioritizing areas that require statistical research.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research accounts for most online surveying and is considered conclusive due to its quantitative nature. In contrast to exploratory research, descriptive research is planned and structured for the information gathered to be statistically inferred from a population.

Causal Research

Causal research, like descriptive research, is quantitative, preplanned, and structured in design. As a result, it is also regarded as conclusive research. Causal research differs from other types of research in that it attempts to explain the cause-and-effect relationship between variables. It differs from descriptive research's observational style in that it uses experimentation to determine whether a relationship is causal.

What is the aim of survey research?

Historically, survey research has included large amounts of population-based data collection. The primary goal of this type of survey research was to quickly obtain information describing the features of a large sample of individuals of interest.

Over To You

Writing a research proposal can be difficult and time-consuming, and it's not that different from writing a thesis or dissertation.

Yes, this is our roundabout way of saying: Don't give up. Invest adequate time to complete your presentation using our actionable survey research proposal templates. When in doubt, reach out to senior researchers for assistance.

Related posts:

- 10 Most Impactful Ways of Writing a Research Proposal: Examples and Sample Templates (Free PDF Attached)

- How to Design the Perfect Service Launch Presentation [Custom Launch Deck Included]

- Quarterly Business Review Presentation: All the Essential Slides You Need in Your Deck

- [Updated 2023] How to Design The Perfect Product Launch Presentation [Best Templates Included]

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 10 One Page Research Proposal PowerPoint Templates to Present Your Project's Significance!

2 thoughts on “top 10 ways to write a survey research proposal with samples and examples”.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

Sales funnel results presentation layouts

3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Future plan powerpoint template slide

Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

Agenda powerpoint slide show

Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

Meet our team representing in circular format

17 Research Proposal Examples

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.

Introduction: Introductions are all about contextualization. They often set the background information with a statement of the problem. At the end of the introduction, the reader should understand what the rationale for the study truly is. I like to see the research questions or hypotheses included in the introduction and I like to get a good understanding of what the significance of the research will be. It’s often easiest to write the introduction last

Literature Review: The literature review dives deep into the existing literature on the topic, demosntrating your thorough understanding of the existing literature including themes, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the literature. It serves both to demonstrate your knowledge of the field and, to demonstrate how the proposed study will fit alongside the literature on the topic. A good literature review concludes by clearly demonstrating how your research will contribute something new and innovative to the conversation in the literature.

Research Design and Methods: This section needs to clearly demonstrate how the data will be gathered and analyzed in a systematic and academically sound manner. Here, you need to demonstrate that the conclusions of your research will be both valid and reliable. Common points discussed in the research design and methods section include highlighting the research paradigm, methodologies, intended population or sample to be studied, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures . Toward the end of this section, you are encouraged to also address ethical considerations and limitations of the research process , but also to explain why you chose your research design and how you are mitigating the identified risks and limitations.

Timeline: Provide an outline of the anticipated timeline for the study. Break it down into its various stages (including data collection, data analysis, and report writing). The goal of this section is firstly to establish a reasonable breakdown of steps for you to follow and secondly to demonstrate to the assessors that your project is practicable and feasible.

Budget: Estimate the costs associated with the research project and include evidence for your estimations. Typical costs include staffing costs, equipment, travel, and data collection tools. When applying for a scholarship, the budget should demonstrate that you are being responsible with your expensive and that your funding application is reasonable.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: A discussion of the anticipated findings or results of the research, as well as the potential contributions to the existing knowledge, theory, or practice in the field. This section should also address the potential impact of the research on relevant stakeholders and any broader implications for policy or practice.

References: A complete list of all the sources cited in the research proposal, formatted according to the required citation style. This demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the relevant literature and ensures proper attribution of ideas and information.

Appendices (if applicable): Any additional materials, such as questionnaires, interview guides, or consent forms, that provide further information or support for the research proposal. These materials should be included as appendices at the end of the document.

Research Proposal Examples

Research proposals often extend anywhere between 2,000 and 15,000 words in length. The following snippets are samples designed to briefly demonstrate what might be discussed in each section.

1. Education Studies Research Proposals

See some real sample pieces:

- Assessment of the perceptions of teachers towards a new grading system

- Does ICT use in secondary classrooms help or hinder student learning?

- Digital technologies in focus project

- Urban Middle School Teachers’ Experiences of the Implementation of

- Restorative Justice Practices

- Experiences of students of color in service learning

Consider this hypothetical education research proposal:

The Impact of Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Middle School Mathematics

Abstract: The proposed study will explore multiplayer game-based learning techniques in middle school mathematics curricula and their effects on student engagement. The study aims to contribute to the current literature on game-based learning by examining the effects of multiplayer gaming in learning.

Introduction: Digital game-based learning has long been shunned within mathematics education for fears that it may distract students or lower the academic integrity of the classrooms. However, there is emerging evidence that digital games in math have emerging benefits not only for engagement but also academic skill development. Contributing to this discourse, this study seeks to explore the potential benefits of multiplayer digital game-based learning by examining its impact on middle school students’ engagement and academic performance in a mathematics class.

Literature Review: The literature review has identified gaps in the current knowledge, namely, while game-based learning has been extensively explored, the role of multiplayer games in supporting learning has not been studied.

Research Design and Methods: This study will employ a mixed-methods research design based upon action research in the classroom. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test control group design will first be used to compare the academic performance and engagement of middle school students exposed to game-based learning techniques with those in a control group receiving instruction without the aid of technology. Students will also be observed and interviewed in regard to the effect of communication and collaboration during gameplay on their learning.

Timeline: The study will take place across the second term of the school year with a pre-test taking place on the first day of the term and the post-test taking place on Wednesday in Week 10.

Budget: The key budgetary requirements will be the technologies required, including the subscription cost for the identified games and computers.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: It is expected that the findings will contribute to the current literature on game-based learning and inform educational practices, providing educators and policymakers with insights into how to better support student achievement in mathematics.

2. Psychology Research Proposals

See some real examples:

- A situational analysis of shared leadership in a self-managing team

- The effect of musical preference on running performance

- Relationship between self-esteem and disordered eating amongst adolescent females

Consider this hypothetical psychology research proposal:

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress Reduction in College Students

Abstract: This research proposal examines the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on stress reduction among college students, using a pre-test/post-test experimental design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods .

Introduction: College students face heightened stress levels during exam weeks. This can affect both mental health and test performance. This study explores the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation as a way to mediate stress levels in the weeks leading up to exam time.

Literature Review: Existing research on mindfulness-based meditation has shown the ability for mindfulness to increase metacognition, decrease anxiety levels, and decrease stress. Existing literature has looked at workplace, high school and general college-level applications. This study will contribute to the corpus of literature by exploring the effects of mindfulness directly in the context of exam weeks.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n= 234 ) will be randomly assigned to either an experimental group, receiving 5 days per week of 10-minute mindfulness-based interventions, or a control group, receiving no intervention. Data will be collected through self-report questionnaires, measuring stress levels, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ experiences, and students’ test scores.

Timeline: The study will begin three weeks before the students’ exam week and conclude after each student’s final exam. Data collection will occur at the beginning (pre-test of self-reported stress levels) and end (post-test) of the three weeks.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: The study aims to provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing stress among college students in the lead up to exams, with potential implications for mental health support and stress management programs on college campuses.

3. Sociology Research Proposals

- Understanding emerging social movements: A case study of ‘Jersey in Transition’

- The interaction of health, education and employment in Western China

- Can we preserve lower-income affordable neighbourhoods in the face of rising costs?

Consider this hypothetical sociology research proposal:

The Impact of Social Media Usage on Interpersonal Relationships among Young Adults

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effects of social media usage on interpersonal relationships among young adults, using a longitudinal mixed-methods approach with ongoing semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data.

Introduction: Social media platforms have become a key medium for the development of interpersonal relationships, particularly for young adults. This study examines the potential positive and negative effects of social media usage on young adults’ relationships and development over time.

Literature Review: A preliminary review of relevant literature has demonstrated that social media usage is central to development of a personal identity and relationships with others with similar subcultural interests. However, it has also been accompanied by data on mental health deline and deteriorating off-screen relationships. The literature is to-date lacking important longitudinal data on these topics.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n = 454 ) will be young adults aged 18-24. Ongoing self-report surveys will assess participants’ social media usage, relationship satisfaction, and communication patterns. A subset of participants will be selected for longitudinal in-depth interviews starting at age 18 and continuing for 5 years.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of five years, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between social media usage and interpersonal relationships among young adults, potentially informing social policies and mental health support related to social media use.

4. Nursing Research Proposals

- Does Orthopaedic Pre-assessment clinic prepare the patient for admission to hospital?

- Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of providing psychological care to burns patients

- Registered psychiatric nurse’s practice with mentally ill parents and their children

Consider this hypothetical nursing research proposal:

The Influence of Nurse-Patient Communication on Patient Satisfaction and Health Outcomes following Emergency Cesarians

Abstract: This research will examines the impact of effective nurse-patient communication on patient satisfaction and health outcomes for women following c-sections, utilizing a mixed-methods approach with patient surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Introduction: It has long been known that effective communication between nurses and patients is crucial for quality care. However, additional complications arise following emergency c-sections due to the interaction between new mother’s changing roles and recovery from surgery.

Literature Review: A review of the literature demonstrates the importance of nurse-patient communication, its impact on patient satisfaction, and potential links to health outcomes. However, communication between nurses and new mothers is less examined, and the specific experiences of those who have given birth via emergency c-section are to date unexamined.

Research Design and Methods: Participants will be patients in a hospital setting who have recently had an emergency c-section. A self-report survey will assess their satisfaction with nurse-patient communication and perceived health outcomes. A subset of participants will be selected for in-depth interviews to explore their experiences and perceptions of the communication with their nurses.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including rolling recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing within the hospital.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the significance of nurse-patient communication in supporting new mothers who have had an emergency c-section. Recommendations will be presented for supporting nurses and midwives in improving outcomes for new mothers who had complications during birth.

5. Social Work Research Proposals

- Experiences of negotiating employment and caring responsibilities of fathers post-divorce

- Exploring kinship care in the north region of British Columbia

Consider this hypothetical social work research proposal:

The Role of a Family-Centered Intervention in Preventing Homelessness Among At-Risk Youthin a working-class town in Northern England

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effectiveness of a family-centered intervention provided by a local council area in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth. This case study will use a mixed-methods approach with program evaluation data and semi-structured interviews to collect quantitative and qualitative data .

Introduction: Homelessness among youth remains a significant social issue. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in addressing this problem and identify factors that contribute to successful prevention strategies.

Literature Review: A review of the literature has demonstrated several key factors contributing to youth homelessness including lack of parental support, lack of social support, and low levels of family involvement. It also demonstrates the important role of family-centered interventions in addressing this issue. Drawing on current evidence, this study explores the effectiveness of one such intervention in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth in a working-class town in Northern England.

Research Design and Methods: The study will evaluate a new family-centered intervention program targeting at-risk youth and their families. Quantitative data on program outcomes, including housing stability and family functioning, will be collected through program records and evaluation reports. Semi-structured interviews with program staff, participants, and relevant stakeholders will provide qualitative insights into the factors contributing to program success or failure.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Budget: Expenses include access to program evaluation data, interview materials, data analysis software, and any related travel costs for in-person interviews.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in preventing youth homelessness, potentially informing the expansion of or necessary changes to social work practices in Northern England.

Research Proposal Template

Get your Detailed Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

This is a template for a 2500-word research proposal. You may find it difficult to squeeze everything into this wordcount, but it’s a common wordcount for Honors and MA-level dissertations.

Your research proposal is where you really get going with your study. I’d strongly recommend working closely with your teacher in developing a research proposal that’s consistent with the requirements and culture of your institution, as in my experience it varies considerably. The above template is from my own courses that walk students through research proposals in a British School of Education.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

8 thoughts on “17 Research Proposal Examples”

Very excellent research proposals

very helpful

Very helpful

Dear Sir, I need some help to write an educational research proposal. Thank you.

Hi Levi, use the site search bar to ask a question and I’ll likely have a guide already written for your specific question. Thanks for reading!

very good research proposal

Thank you so much sir! ❤️

Very helpful 👌

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analysing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyse the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyse the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research: Investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research: Finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research: Collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics: Measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology: Researching personality traits, preferences, and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- University students in the UK

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18 to 24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalised to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every university student in the UK. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalise to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions.

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by post, online, or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by post is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g., residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low.

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyse.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds.

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping centre or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g., the opinions of a shop’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations.

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data : the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyses the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analysed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g., yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g., a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g., age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g., leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analysed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an ‘other’ field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic.

Use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no bias towards one answer or another.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by post, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analysing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also cleanse the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organising them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analysing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analysed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyse it. In the results section, you summarise the key results from your analysis.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/surveys/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples.

Faculty and researchers : We want to hear from you! We are launching a survey to learn more about your library collection needs for teaching, learning, and research. If you would like to participate, please complete the survey by May 17, 2024. Thank you for your participation!

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

- University Libraries

Survey Research: Design and Presentation

- Planning a Thesis Proposal

- Introduction to Survey Research Design

- Literature Review: Definition and Context

- Slides, Articles

- Evaluating Survey Results

- Related Library Databases

The goal of a proposal is to demonstrate that you are ready to start your research project by presenting a distinct idea, question or issue which has great interest for you, along with the method you have chosen to explore it.

The process of developing your research question is related to the literature review. As you discover more from your research, your question will be shaped by what you find.

The clarity of your idea dictates the plan for your dissertation or thesis work.

From the University of North Texas faculty member Dr. Abraham Benavides:

Elements of a Thesis Proposal

(Adapted from the Department of Communication, University of Washington)

Dissertation proposals vary but most share the following elements, though not necessarily in this order.

1. The Introduction

In three paragraphs to three or four pages very simply introduce your question. Use a narrative to style to engage readers. A well-known issue in your field, controversy surrounding some texts, or the policy implications of your topic are some ways to add context to the proposal.

2. Research Questions

State your question early in your proposal. Even if you are going to restate your research questionas part of the literature review, you may wish to mention it briefly at the end of the introduction.

Make sure if you have questions which follow from your main question that this is clearly indicated. The research questions should include any boundaries you have placed on your inquiry, for instance time, place, and topics. Terms with unusual meanings should be defined.

3. Literature Synthesis or Review

The proposal must be described within the broader body of scholarship around the topic. This is part of establishing the significance of your research. The discussion of the literature typically shows how your project will extend what’s already known.

In writing your literature review, think about the important theories and concepts related to your project and organize your discussion accordingly; you usually want to avoid a strictly chronological discussion (i.e., earliest study, next study, etc.).

What research is directly related to your topic? Discuss it thoroughly.

What literature provides context for your research? Discuss it briefly.

In your proposal you should avoid writing a genealogy of your field’s research. For instance, you don’t need to tell your committee about the development of research in the entire field in order to justify the particular project you propose. Instead, isolate the major areas of research within your field that are relevant to your project.

4. Significance of your Research Question

Good proposals leave readers with a clear understanding of the dissertation project’s overall significance. Consider the following:

- advancing theoretical understandings

- introducing new interpretations

- analyzing the relationship between variables

- testing a theory

- replicating earlier studies

- exploring the whether earlier findings can be demonstrated to hold true in new times, places, or circumstances

- refining a method of inquiry.

5. Research Method

The research method that will be used involves three levels of concern:

- overall research design

- delineation of the method

- procedures for executing it.

At the outset you have to show that your overall design is appropriate for the questions you’re posing.

Next, you need to outline your specific research method. What data will you analyze?

How will you collect the data? Supervisors sometimes expect proposals to sketch instruments (e.g., coding sheets, questionnaires, protocols) central to the project.

Third, what procedures will you follow as you conduct your research? What will you do with your data? A key here is your plan for analyzing data. You want to gather data in a form in which you can analyze it. [In this case the method is a survey administered to a group of people]. If appropriate, you should indicate what rules for interpretation or what kinds of statistical tests that you’ll use.

6. Tentative Dissertation Outline

Give your committee a sense of how your thesis will be organized. You can write a short (two- or three-sentence) paragraph summarizing what you expect to include in each section of the thesis.

7. Tentative Schedule for Completion

Be realistic in projecting your timeline. Don’t forget to include time for human subjects review, if appropriate .

8. References

If you didn’t use footnotes or endnotes throughout, you should include a list of references to the literature cited in the proposal.

9. Selected Bibliography of Other Sources

You might want to append a more extensive bibliography (check with your supervisor). If you include one, you might want to divide it into several subsections, for instance by concept, topic or field.

- << Previous: Introduction to Survey Research Design

- Next: Literature Review: Definition and Context >>

- Last Updated: Jan 22, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uml.edu/rohland_surveys

- Request new password

- Create a new account

Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches

Student resources, research proposal tools and sample student proposals.

Sample research proposals written by doctoral students in each of the key areas covered in Research Design --quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods—are provided as a useful reference. A Research Proposal checklist also serves to help guide your own proposal-writing.

› Morales Proposal_Qualitative Study

› Kottich Proposal_Quantitative Study

› Guetterman Proposal_Mixed Methods Study

› Research Proposal Checklist

How to Write a Survey Proposal

by Vicki A. Benge

Published on 26 Sep 2017

Researchers survey different populations for various reasons. Marketers test products through consumer surveys. Political candidates survey voters' concerns through questionnaires. One population group that is readily available and used for diverse types of surveys consists of college students. These surveys generally require that a written proposal be submitted to an approval committee. The written form requires the author to follow a few basic guidelines.

Introducing the Proposal

In the introduction, provide an overview of the survey. Identify the survey topic, the data sought and the target. The introduction should also explain the purpose of the survey, how the results will be used, how the volunteers or paid respondents will be contacted and how many persons will be questioned.

The Proposal

The dates on which the survey will begin and end should be included in the body of the proposal. Whether the participants' identities will be revealed along with the results should also be noted. A copy of the survey -- that is, the actual questions the surveyors will be asking -- should be a part of the proposal. This will give the review committee or the pertinent authority that will be approving or denying the survey an opportunity to analyze the intent fully. If the results are subject to sampling errors, explain how that data will be handled.

Be Specific

Suppose a professor of neurology heading a research group wants to survey the sleeping habits of college students and needs 100 volunteers to answer five short questions. The research team could contact students on campus to seek willing participants. The survey proposal would include details about what the neurology team is trying to learn, including background data on why the survey is important, such as citing prior research in the field.

Provide Contact Information

Not only should the names of surveyors be included in a survey proposal, but a contact person for the proposal also should be clearly identified. In addition, details about how participants will be contacted -- by email, telephone or in person -- should be included.

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Writing your research proposal

A doctoral research degree is the highest academic qualification that a student can achieve. The guidance provided in these articles will help you apply for one of the two main types of research degree offered by The Open University.

A traditional PhD, a Doctor of Philosophy, usually studied full-time, prepares candidates for a career in Higher Education.

A Professional Doctorate is usually studied part-time by mid- to late-career professionals. While it may lead to a career in Higher Education, it aims to improve and develop professional practice.

We offer two Professional Doctorates:

- A Doctorate in Education, the EdD and

- a Doctorate in Health and Social Care, the DHSC.

Achieving a doctorate, whether a PhD, EdD or DHSC confers the title Dr.

Why write a Research Proposal?

To be accepted onto a PhD / Professional Doctorate (PD) programme in the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies (WELS) at The Open University, you are required to submit a research proposal. Your proposal will outline the research project you would like to pursue if you’re offered a place.

When reviewing your proposal, there are three broad considerations that those responsible for admission onto the programme will bear in mind:

1. Is this PhD / PD research proposal worthwhile?

2. Is this PhD / PD candidate capable of completing a doctorate at this university?

3. Is this PhD / PD research proposal feasible?

Writing activity: in your notebook, outline your response to each of the questions below based on how you would persuade someone with responsibility for admission onto a doctoral programme to offer you a place:

- What is your proposed research about & why is it worthy of three or more years of your time to study?

- What skills, knowledge and experience do you bring to this research – If you are considering a PhD, evidence of your suitability will be located in your academic record for the Prof Doc your academic record will need to be complemented by professional experience.

- Can you map out the different stages of your project, and how you will complete it studying i) full-time for three years ii) part-time for four years.

The first sections of the proposal - the introduction, the research question and the context are aimed at addressing considerations one and two.

Your Introduction

Your Introduction will provide a clear and succinct summary of your proposal. It will include a title, research aims and research question(s), all of which allows your reader to understand immediately what the research is about and what it is intended to accomplish. We recommend that you have one main research question with two or three sub research questions. Sub research questions are usually implied by, or embedded within, your main research question.

Please introduce your research proposal by completing the following sentences in your notebook: I am interested in the subject of ………………. because ……………… The issue that I see as needing investigation is ………………. because ………………. Therefore, my proposed research will answer or explore [add one main research question and two sub research questions] …... I am particularly well suited to researching this issue because ………………. So in this proposal I will ………………. Completing these prompts may feel challenging at this stage and you are encouraged to return to these notes as you work through this page.

Research questions are central to your study. While we are used to asking and answering questions on a daily basis, the research question is quite specific. As well as identifying an issue about which your enthusiasm will last for anything from 3 – 8 years, you also need a question that offers the right scope, is clear and allows for a meaningful answer.

Research questions matter. They are like the compass you use to find your way through a complicated terrain towards a specific destination.

A good research proposal centres around a good research question. Your question will determine all other aspects of your research – from the literature you engage with, the methodology you adopt and ultimately, the contribution your research makes to the existing understanding of a subject. How you ask your question, or the kinds of question you ask, matters because there is a direct connection between question and method.

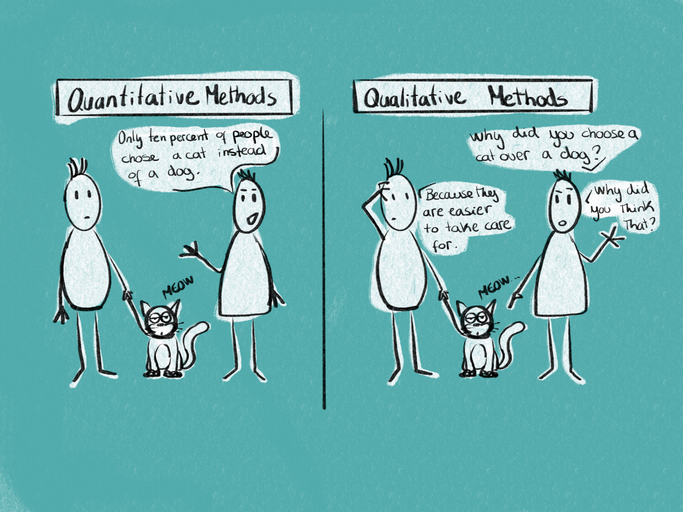

You may be inclined to think in simplistic terms about methods as either quantitative or qualitative. We will discuss methodology in more detail in section three. At this point, it is more helpful to think of your methods in terms of the kinds of data you aim to generate. Mostly, this falls into two broad categories, qualitative and quantitative (sometimes these can be mixed). Many academics question this distinction and suggest the methodology categories are better understood as unstructured or structured.

For example, let’s imagine you are asking a group of people about their sugary snack preferences.

You may choose to interview people and transcribe what they say are their motivations, feelings and experiences about a particular sugary snack choice. You are most likely to do this with a small group of people as it is time consuming to analyse interview data.

Alternatively, you may choose to question a number of people at some distance to yourself via a questionnaire, asking higher level questions about the choices they make and why.

Once you have a question that you are comfortable with, the rest of your proposal is devoted to explaining, exploring and elaborating your research question. It is probable that your question will change through the course of your study.

At this early stage it sets a broad direction for what to do next: but you are not bound to it if your understanding of your subject develops, your question may need to change to reflect that deeper understanding. This is one of the few sections where there is a significant difference between what is asked from PhD candidates in contrast to what is asked from those intending to study a PD. There are three broad contexts for your research proposal.

If you are considering a PD, the first context for your proposal is professional:

This context is of particular interest to anyone intending to apply for the professional doctorate. It is, however, also relevant if you are applying for a PhD with a subject focus on education, health, social care, languages and linguistics and related fields of study.

You need to ensure your reader has a full understanding of your professional context and how your research question emerges from that context. This might involve exploring the specific institution within which your professionalism is grounded – a school or a care home. It might also involve thinking beyond your institution, drawing in discussion of national policy, international trends, or professional commitments. There may be several different contexts that shape your research proposal. These must be fully explored and explained.

Postgraduate researcher talks about research questions, context and why it mattered

The second context for your proposal is you and your life:

Your research proposal must be based on a subject about which you are enthused and have some degree of knowledge. This enthusiasm is best conveyed by introducing your motivations for wanting to undertake the research. Here you can explore questions such as – what particular problem, dilemma, concern or conundrum your proposal will explore – from a personal perspective. Why does this excite you? Why would this matter to anyone other than you, or anyone who is outside of your specific institution i.e. your school, your care home.

It may be helpful here to introduce your positionality . That is, let your reader know where you stand in relation to your proposed study. You are invited to offer a discussion of how you are situated in relation to the study being undertaken and how your situation influences your approach to the study.

The third context for your doctoral proposal is the literature:

All research is grounded in the literature surrounding your subject. A legitimate research question emerges from an identified contribution your work has the potential to make to the extant knowledge on your chosen subject. We usually refer to this as finding a gap in the literature. This context is explored in more detail in the second article.

You can search for material that will help with your literature review and your research methodology using The Open University’s Open Access Research repository and other open access literature.

Before moving to the next article ‘Defining your Research Methodology’, you might like to explore more about postgraduate study with these links:

- Professional Doctorate Hub

- What is a Professional Doctorate?

- Are you ready to study for a Professional Doctorate?

- The impact of a Professional Doctorate

Applying to study for a PhD in psychology

- Succeeding in postgraduate study - OpenLearn - Open University

- Are you ready for postgraduate study? - OpenLearn - Open University

- Postgraduate fees and funding | Open University

- Engaging with postgraduate research: education, childhood & youth - OpenLearn - Open University

We want you to do more than just read this series of articles. Our purpose is to help you draft a research proposal. With this in mind, please have a pen and paper (or your laptop and a notebook) close by and pause to read and take notes, or engage with the activities we suggest. You will not have authored your research proposal at the end of these articles, but you will have detailed notes and ideas to help you begin your first draft.

More articles from the research proposal collection

Defining your research methodology

Your research methodology is the approach you will take to guide your research process and explain why you use particular methods. This article explains more.

Level: 1 Introductory

Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal

This article explores the ethical issues that may arise in your proposed study during your doctoral research degree.

Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview

The final article looks at writing your research proposal - from the introduction through to citations and referencing - as well as preparing for your interview.

Free courses on postgraduate study

Are you ready for postgraduate study?

This free course, Are you ready for postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and ensure you are ready to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Succeeding in postgraduate study

This free course, Succeeding in postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

This free OpenLearn course is for psychology students and graduates who are interested in PhD study at some future point. Even if you have met PhD students and heard about their projects, it is likely that you have only a vague idea of what PhD study entails. This course is intended to give you more information.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Tuesday, 27 June 2023

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'quantitative methods versus qualitative methods - shows 10% of people getting a cat instead of a dog v why they got a cat.' - The Open University under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'Applying to study for a PhD in psychology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Succeeding in postgraduate study' - Copyright: © Everste/Getty Images

- Image 'Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal' - Copyright: Photo 50384175 / Children Playing © Lenutaidi | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview' - Copyright: Photo 133038259 / Black Student © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Defining your research methodology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Writing your research proposal' - Copyright free

- Image 'Are you ready for postgraduate study?' - Copyright free

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

What’s Included: Research Proposal Template

Our free dissertation/thesis proposal template covers the core essential ingredients for a strong research proposal. It includes clear explanations of what you need to address in each section, as well as straightforward examples and links to further resources.

The research proposal template covers the following core elements:

- Introduction & background (including the research problem)

- Literature review

- Research design / methodology

- Project plan , resource requirements and risk management