Research Methods for Public Policy

- Open Access

- First Online: 19 October 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Susan Mbula Kilonzo 3 &

- Ayobami Ojebode 4

23k Accesses

This chapter examined the nature of public policy and role of policy analysis in the policy process. It examines a variety of research methods and their use in public policy engagements and analysis for evidence-informed policymaking. It explains qualitative methods, quantitative methods, multiple and mixed-method research. Other issues addressed include causal research in public policy, report writing and communication and related issues in public policy research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Qualitative Methods for Policy Analysis: Case Study Research Strategy

Perspectives on Policy Analysis: A Framework for Understanding and Design

Social Research and Public Policy: Some Cautionary Notes

Introduction.

As implied by the topic, this chapter focuses on research methods applied or applicable in public policy research. Though the overriding focus is on specific research methods, we deemed it necessary to preface these with a brief discussion of the nature of public policy research and the nature of policy-engaged research problem or question. These are then followed by the specific research approaches or traditions and methods as applied to public policy. Given that public policy research deals with issues that have important implications for the society, the mixed-method research is often preferred as a means of arriving at findings and conclusion concrete and reliable enough to serve as a basis for policy. For this reason, we devoted a section to mixing methods in public policy research. This chapter is thus divided into four sections:

Nature of public policy research

The policy-engaged research problem or question,

Specific public policy research approaches and methods, and

Mixing methods in public policy research.

In the first section, we focus on the definitive characteristics of the kind of research that supports or evokes public policy, especially the solution-orientation of such research. In the second section, we focus on what it means for research to be policy-engaged—which is different from being policy-relevant. We propose the nature and source of a good problem or question for policy-engaged research and its basic design. In the third section, we focus on the two broad traditions of research: qualitative and quantitative traditions, and the specific methods under these traditions. We explain how these methods are used in public policy research using both hypothetical and existing examples. In the last section, we discuss mixing research methods in public policy research, stressing the reasons for it and summing up the process of doing it.

Nature of Public Policy Research

Public policy research is one whose primary aim is to understand or explain social, political, economic, cultural and other issues that are significant to the society and which require the intervention or attention of policy actors. In providing an understanding of such issues, the research also presents itself as a trustable basis for the actions and interventions of these policy actors. It must, therefore, be a piece of research based on sound evidence, produced out of convincing rigour and woven from start to finish around a societal issue of concern.

In addition to being thorough and trustable, public policy research must also go beyond describing a problem or situation into engaging the how and why of things (Osifo 2015 : 149) for it to establish causality with reference to a given problem and the options of addressing such a problem. Descriptive studies do sometimes provide an important basis for policy; however, causal studies often interest and command the attention of policy actors more than descriptive ones do.

A good public policy research is sensitive to both the policy and political agenda. These two environments or elements determine action or inaction. Howlett ( 2012 : 451) argues for an approach that encourages absorption of research outputs at two levels: enhancing instrumental arguments about policy programme content and ensuring a deeper political engagement experience.

Though policy makers do not entirely depend on research to make decisions on policy options (Edwards 2004 ; UK Cabinet Office 2009 ), the role of research, and specifically field-based research, in public policy remains critical (Mead 2005 ; Young 2005 ). Since scholarly research competes with expert knowledge, domestic and international policy, stakeholder consultations and evaluation of previous policies, among other sources (UK Cabinet 1999), evidence generated from research that is meant to inform public policy needs a strong basis for argument on the problem under scrutiny, as well as a variety of policy options from field evidence.

Recent studies show that research in policymaking over the last four decades plays a less direct role than is often assumed and expected (Howlett 2012 ). Nevertheless, the role of research in public policy is not to be downplayed, and as Mead ( 2005 : 535) explains, field research is essential to realistic policy research that ties governmental action to good outcomes. However, we need to take cognizance of the fact that, as Tierney and Clemens ( 2011 ) argue, many of today’s most pressing policy issues are extraordinarily complex and will benefit from carefully conceived and analysed studies utilizing multiple methodological approaches. Public policy researchers should understand this complexity of policy problems. This complex web determines, to a great extent, what forms of research and/or research methods a researcher should consider.

Literature shows that in the history of public policy research, statistical evidence was very important (Mead 2005 ). Studies meant to inform policy were therefore mostly, if not always, survey-based (Mead 2005 ). Survey-based research, as Mead ( 2005 : 544) shows, is good at generating accurate depictions of the clientele served by a given policy. Social problems and their correlates can be clearly captured. Earlier approaches to policy research favoured output that could be generalized across settings that were validated and reliable. In those early approaches, quantitative research, especially survey, was given priority. Qualitative research did not so much move into policy arena and research evidence from qualitative studies did not seem to find a place in policy discussion tables (Tierney and Clemens 2011 : 59).

Over the years, survey-based approach has been criticized for its narrow economistic approach because social problems are complex. The argument is that survey-based policy research projects onto its subjects, the psychology assumed by the quantitative researcher. Simply put on its own, the approach lacks the ability to explain why and how complex social problems arise, and what public policies would best be suited to address them in their complexity. Surveys, for instance, may not give the full range of information required to account for the behaviours of the poor, needy and dependent persons in certain circumstances. These people, though challenged by certain economic factors, can survive in difficult circumstances, but the how and why of their survival would be beyond the easy reach of survey. Thus, as Mead ( 2005 ) argues, there is need for a more complex and robust approach that incorporates those factors that are beyond the statistics. We argue that for a public policy research to claim authenticity of findings that capture the attention of policy makers, and subsequently inform the policy process, an integration of research methods, that is, mixed-method design, is important.

Public policy research is meant to provide solutions to social and public problems that are in many ways complex. Establishing causes and effects of these problems run beyond analysis of existing policies. Mead ( 2013 ), for instance, argues:

[Where] texts in public policy devote attention to both policy analysis and political analysis; they fail to capture the intimate connection between them. The two subjects appear as separate worlds, when they are really two sides of the same coin. The texts do not consider that political constraints should really be part of policy argument or that the policy-making process can sharply limit what best policy means. And in research on public policy, there is even less sense of policy and politics shaping and reshaping each other. Typically, the usual division prevails where economists recommend best policy while political scientists explain what government does. (p. 393)

These views relate to the policy and politics dichotomy, and how political analysis is good in reshaping policy analysis (Mead 2013 : 392). While it is important to pay attention in public policy research to how these two influence each other, it is also important to pay careful attention to the stakeholders. Good research methods for public policy should engage stakeholders in the research process to enhance the use of the research findings and recommendations for effective policies. Besides the policy makers, policy actors include the public, which is always at the receiving end of the end products of public policy research are important. Consultations with them at most, if not all levels, help researchers to articulate policies that include their ideas or address their concerns (Oxman et al. 2009 ) and result in the good policy performance.

The Policy-Engaged Research Problem/Question

With reference to their level of policy engagement, public policy research in Africa can be categorized into three: public policy-appended research, commissioned policy research and public policy analysis. Public policy-appended research is the most common of the three. For most African researchers, there is a mandatory section of their article or thesis that presents policy recommendations. In that section, researchers attempt to point out how their research findings can be applied to real-life policy situations and consequently change those situations for the better. Efforts are made by experienced researchers to ensure a close fit between the recommendations and the findings that precede it in the article or thesis. As common as this genre of public policy research is, it is a flawed approach for many reasons. The approach treats policy not as the centre of the research but as an appendage. Put differently, the researcher decides her or his research problem and question and decides on the methods most suitable for this. At the conclusion of the research, she or he then turns to policy actors with recommendations. Since the research was not informed by a policy need or gap, it can hardly fit into the existing agenda and conversations among policy actors. It neither speaks the language of policy actors nor considers their priorities. The researcher would not have attempted to include policy actors at most, if not all, stages of the research, and as we will discuss shortly, there are consequences of not doing this. It also assumes that policy actors (i.e. policy makers, civil society and other stakeholders, including citizens) are on the lookout for policy recommendations from researchers and can wade through the different sections of the research to find these recommendations. As Oyedele, Atela and Ojebode ( 2017 ) opined, this is hardly so. The researcher’s research is her or his business, not that of the policy actors. As a result, policy actors do not access the tonnes of policy recommendations made by researchers.

Commissioned public policy research projects are initiated by government agencies and non-governmental organizations to address specific policy or implementation problem. The driving research question and the nature of the expected findings are articulated by the commissioning organization. A critical objection to this genre of public policy research is researcher’s autonomy on crucial fronts. To what extent can a researcher turn out findings that conflict with the political aspirations and public image of the funding government or its agency? How can the researcher be sure that his or her findings are not spun or twisted in favour of government? Therefore, while the findings and recommendations of this genre of public policy research are likely to be more easily accepted by policy actors than the findings of public policy-appended research, there is usually a cloud of doubt around its objectivity and integrity.

A third genre of public policy research deals with policy analysis . These studies take on an existing policy and subject its components to critical analysis often conjecturing whether it would produce expected results. They explore inconsistencies, systemic barriers and feasibility of a policy, and then draw conclusions as to why a policy works or does not. They may serve as formative or summative studies depending on when they are conducted in the life cycle of a policy. The challenge of this approach to public policy research has been that the researcher/analyst is basically tied to the outcomes of policies in existence—policies that he or she did not play a role in formulating.

The foregoing genres of public policy research are, at best, only partially policy-engaged. They may be policy-relevant, but they are not policy-engaged. So, the questions for us here are: What is policy-engaged research? How does it differ from policy analysis, commissioned public policy research and public policy-appended research? What is it that the other three misses out that policy-engaged research is good for? And how do we then design research in a way that the methods used are relevant in informing the public policymaking processes?

A policy-engaged piece of research derives its roots from the questions that are being asked in policy circles. As a response to current public policy issues, it is driven by a research question that explores, extends or clarifies a policy question or problem. Policy-engaged research therefore means bringing on board the stakeholders relevant in the development of a given public policy (Lemke and Harris-Wai 2015 ), whether their role is interest or influence. This means that there is an all-round way of understanding the problem that the policy is intended to solve and the politics surrounding the decision-making process.

It is important for a researcher to understand in policy-engaged research, is the need to tailor the research in a way that the policy options suggested are practical. This is because, a policy attempts to solve or prevent a problem, or scale up progress, and policy actors are interested in “what works”. In other words, they are keen about what causes an outcome or makes things happen. A piece of public policy research would, therefore, do well if it were causal, rather than descriptive.

There are two fundamental characteristics of a public policy research problem or question: First, it should explore cause, outcome, and/or causal mechanism in relation to an existing policy or a policy action it intends to propose. In exploring these, the researcher can tease out the specific factors that are responsible for a certain policy problem/issue (outcome) and have conclusive findings from which to confidently suggest specific points of intervention in a policy progression. For instance, if the researcher discovers that misinformation is the cause of vaccine rejection, then he or she knows better than to suggest increased procurement of vaccines but would rather suggest media campaigns or community meetings to increase citizens’ awareness of that vaccination. If, in exploring the mechanism between misinformation and rejection, she discovers that misinformation leads to cognitive dissonance which then leads citizens to seek clarification from traditional birth attendants who then counsels them to abstain from vaccination and whom they then obey by rejecting the vaccination, she is further equipped to make pointed suggestion on which point in the chain to focus intervention or “tweaking”. Public policy research without such causal information can easily become a shot in the dark.

Second, the public policy research problem should resonate with the questions that policy actors are asking as well as the questions that they should be asking. While it is important for the public policy research question to evolve from policy questions, it is also important to note that policy questions are sometimes wrong or inadequate. Put bluntly, policy actors sometimes do not ask the right questions. It is, therefore, important for the researcher to identify these policy questions and give them the needed redirection. Policy actors, for instance, may be asking if the gap between male and female children about access to education is narrowing or widening following the adoption of an affirmative action policy in favour of the girl child. Whereas this is an important question, it is not likely to reveal information that is specific enough to be a basis for the right adjustment of the policy. It is not only simply descriptive but also narrow and unworthy of much research. The researcher should push harder with questions of cause, outcome and causal mechanism about the male-female disparity in access to education in this case. Has the policy produced a narrowing of the gap? If not, why has it not? What skills or resources are lacking that account for this lack of narrowing? Or what historical, religious or cultural factors combine or act alone to ensure continuity of the gap despite the policy? The public policy research question may not be the exact one that policy actors are asking, but it is indeed a vital extension and reflection of the policy question.

When we have public policy research problems that are unrelated to the problems that policy actors have, the consequence can be predicted. We will come up with findings that may be scientifically sound but unattractive to policy actors. Such findings will have little or no uptake. This approach speaks to the disconnection which a vast amount of literature points out—the disconnection between researchers and policy makers (Edwards 2004 : 2; Young 2005 : 730–1; Saetren 2005 ). When we ask public policy research questions that are not causal, the consequence can as well be predicted—our findings will not be convincing or informing enough to move policy actors to targeted action. Ultimately, questions that are not in line with the policy makers, and non-causal questions, render our research simply as just another piece of research for its sake.

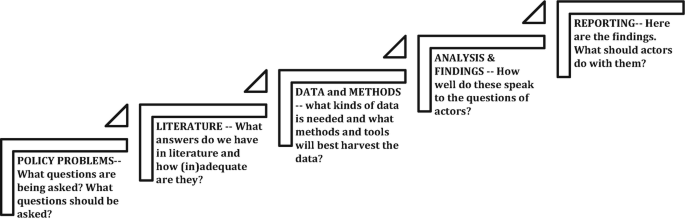

A research question largely dictates its own research design. The type of research question we advocate above implies an iterative approach that begins with policy actors and finally returns to them. It also implies a specific kind of methods. It is a back-and-forth movement that considers the concerns of the actors as the fulcrum. In addition to being iterative, the design is also causal. The stages given below may apply (Fig. 4.1 ).

Approach to designing policy research

The way in which research is designed determines the ability of the researcher to claim causal conclusions (Bachman 2007 ). This is important for it gives indication to policy makers on what influential factors lead to what outcomes. If this is not known, making relevant policy decisions is always not possible.

Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Public Policy Research

In this section, we explain the commonly used qualitative and quantitative research methods for public policy.

Qualitative Methods in Public Research

Briefly stated, qualitative methods aim at providing deeper perspectives, attitudes, perceptions and contextual insights that surround the issue under investigation as experienced and understood by those living through it. The outcome of qualitative methods is usually the verbalized thoughts and viewpoints of the subjects of investigation rather than numbers or statistics. The following are some of the research methods used in qualitative research. Note that each of these methods applies a wide range of tools to collect data.

Historical and Archival Research

Libraries and archives store historical information in many forms including diaries, pictures, documents, minutes and artefacts, among others. These mean that they might have been stored as primary or secondary data. Historical or archival information that can be considered as primary is that which was collected from the author or field and stored in its original form without undergoing any form of analysis and change. Such may include minutes, diaries, pictures, artefacts, personal memoirs, autobiographies and others of the same nature. Any historical information that has gone through any studies or analysis then becomes secondary data. These may include journals, books and magazines, among others.

When a researcher wants to use historical and archival data, the aim is to research on the past and already existing information. However, historical and archival research does not always mean deriving data from the archives. A policy researcher may design a historical study in which they endeavour to visit the field and collect data from knowledgeable individuals concerning a certain historical issue of policy concern. They may partly engage documents from archives or libraries to historicize, contextualize and corroborate the issue under research. It is also the nature of many parliamentary researchers to “mine” data from parliamentary libraries/archives, some of which contain data that is classified as primary data.

Historical data is important in public policy, for it helps researchers situate their arguments within existing narratives, contexts and prior solutions suggested for policy problems. Roche ( 2016 ) argues that making assumptions about the ease with which historical research can be done is misleading. He advises that knowledge of context and a sequential approach should be given ascendance in the researcher’s priority. The researcher should be aware of chronology of information to clearly provide a coherent picture of the policy issue at hand. This implies that the past information should be relatable to the most current. With the advent in technology, most data are now digitalized, and as such, it is easy to get information from the Internet.

Archives are used to store vital government records such as personal letters, diaries, minutes, logbooks, plans, maps, photographs, among others, that easily qualify to be analysed as primary data (Roche 2016 : 174). Roche ( 2016 : 183–4) notes the challenge of fragmentation and partial availability of archival documents. He further alludes to technical challenges of the clarity of some of archival data. He cites examples of materials that were handwritten a while back and which may be ineligible. Historical and archival research apply both desk-based methods and interview techniques of data collection. Photography can also be used.

Ethnographic Methods

Ethnographic approach to research studies communities in their natural setting to understand their activities, behaviour, attitudes, perspectives and opinions within their social surrounding (Brewer 2000 ). To do so, ethnography entails close association with the research communities and sometimes participation in their activities (Brewer 2000 : 17). In fact, the commonly used methods of data collection in ethnography are participant (and sometimes non-participant) observation. The former allows for the researcher to get involved in the activities of the communities, while the latter is designed for the researcher to observe from the periphery. As Brewer argues, it is this day-to-day involvement in people’s activities that enable the researcher to make sense of the social worldviews of the research participants.

Non-participant observation describes a research situation where a researcher does not take part in the processes, events or activities that he or she is observing but removes himself or herself from the happenings to critically observe from a distance. This has challenges especially if the observed become aware of intrusion and subsequently alter their behaviour (Hawthorne effect). Sometimes the researcher may structure the observations or decide to use unstructured observations. The two differ in the sense of planning on the observation activities. For the structured type, the researcher has in mind what they want to observe and as such have a list and indications of what they would like to see. Take, for instance, a study on access to water meant to contribute to a water policy. A researcher may choose to observe how (many) times is water served at certain water points; how many people queue for the water in each of these servings; and this is likely to tell the researcher whether the water points are enough or otherwise. In unstructured observation, the researcher gets into the field with a research idea but without the specifics of that nature of data they expect from the field. Qualitative interview methods such as oral interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) may apply where necessary during ethnography. Note taking is often applied as well.

Phenomenology

This method focuses on lived experiences of a given phenomenon by an individual or a group of individuals. Individuals can describe their views and opinions about the phenomenon in question (Johnson and Christensen 2014 ). Research on fertility issues can target women who either have or do not have children, depending on what the researcher wants to unearth, with individual women providing their lived experiences on the issue under investigation. Phenomenology is also applicable when writing biographies (an account of someone’s life written by someone else). Generally, life histories, personal testimonies and experiences are best collected through this method. This implies that oral in-depth interviews and desk-based methods of data collection are important in understanding the stories in question.

Narrative Method

A narrative is a story that structures human activity to give it some form of meaning (Elçi and Devran 2014 ). Research that applies the narrative method encourages the research participants to tell their stories around a certain issue. The researcher listens to the stories and uses them to make informed analysis on the issue at hand. A researcher concerned about experiences of people living in zones of conflicts may ask questions that elicit stories of the victims or perpetrators of violence and present these in narrative form. Researchers who use phenomenology method often apply use of narratives, but not always. Phenomenological research may not rely on story telling alone. A researcher may use desk-based method to gain perspectives of the target communities as well.

Case Studies

A case study is an intensive analysis of a small number of phenomena (events, actors, activities, processes, organizations, communities, among others) in each context. Though one can use a mix of qualitative or quantitative data within a case study, meaning that case studies can also take quantitative route, a case study is always a detailed analysis of the relationships between the contextual factors and a visible occurrence. Case studies are therefore considered when there is need for detailed information on the issue(s) under investigation. A single case study aims at providing details on the variables of interest. A comparative case study has two or more cases (what literature refers to as small-N) for the purpose of making comparative causal explanations. A researcher uses comparative case studies when they want to tease out the similarities and/or differences between or among the cases, usually for the purpose of explaining causation.

Action Research

Action research is problem-solution focused. It falls under the category of applied research and subsequently, uses practical approach to solve an immediate problem. In this case, the researcher works together with a community or practitioners to identify a challenging issue within the community that requires a possible solution. They formulate the problem together and design the research in a way that the aim is to work towards getting a solution to the problem. Once the data collected is analysed and recommendations given, a plan of action is drawn and applied to the problem that the research was designed for. The community (and researcher) reflects on the effectiveness of the solutions applied to take appropriate measures. In a nutshell, Huang ( 2010 : 99) explains that action research proceeds from a praxis of participation guided by practitioners’ concerns for practicality; it is inclusive of stakeholders’ ways of knowing and helps to build capacity for ongoing change efforts. This form of research requires money and time. As Huang ( 2010 ) notes, action research can take a qualitative, quantitative or mixed-method perspective. Various methods of data collection including oral interviews, surveys, community mapping, observation, among others, may be applied in action research.

Grounded Theory Research

A researcher may apply two approaches, inductive or deductive, to do research. The deductive approach means that one has a theoretical basis from where hypotheses can be formulated and tested. Inductive approach, on the other hand, is grounded or bottom-up. The researcher in this case starts by making observations that then provide him or her with patterns from where conclusions and theory can be drawn. Grounded research therefore moves from the point of poor or no theory up to where a researcher can deduce an informed hypothesis and towards theory building, all from the observations and analysis made from data. It is similar with other qualitative methods in the use of the various methods of data collection including oral interviews, observation and use of all forms of documents (Strauss and Corbin 1994 ).

Quantitative Methods in Public Policy Research

Quantitative research generates numerical data using such research instruments as the questionnaire, tests, code sheets for content analysis and similar other sources. The data is then subjected to mathematical or statistical analysis (Muijs 2004 ).

Literature divides quantitative research methods into two—experimental and non-experimental methods. Experimental methods are the quantitative approaches that are mainly concerned with manipulation situations with an aim of establishing cause and effect. Bachman ( 2007 : 151) argues that “the experimental design provides the most powerful design for testing causal hypotheses about the effect of a treatment or some other variable whose values can be manipulated by the researchers”. Experiments allow us to explain causality with some confidence because of the use of treatment and control. The basic and elementary type of experimental research involves setting up two groups (treatment and control groups) and introducing change to the treatment but nothing to the control. The effect of the change is measured in the differences in the behaviour or performance of the two groups after the treatment.

Experimental research has been criticized for their weakness in reflecting reality in that they take people out of their natural settings into a laboratory or pseudo-labs. Despite this, they can make important input to policymaking. For instance, micro-level policies on classroom instruction and curriculum have been largely influenced by experimental research.

Non-experimental methods do not manipulate. They are aimed and providing a descriptive picture of what is being studied. Non-experimental methods, as Muijs ( 2004 ) indicates, are more varied and may range from surveys to historical research, observations and analysis of existing data sets (applied quantitative methods). We will briefly look at the experimental and non-experimental quantitative research in the following sections.

Experimental Methods

The different types of experiments can range from randomized control trials (RCTs) to quasi-experiments, and sometimes, natural experiments.

Randomized Control Trials (RCTs)

In their simplest form, RCTs involve assigning individuals, groups, communities or settlements to experimental/treatment and control groups. The experimental group receives treatment—school feeding—while the control group receives no treatment (no school feeding). The difference in school attendance rates between these groups could then be attributed to the treatment, that is, school feeding. If statistics shows that attendance increases in the treatment group but stays the same or decreases in the control group, other things being equal, the researcher can make claims about school feeding causing increase in school attendance. Randomized control trials are expensive and are usually beyond the budget reach of most researchers. Public policy researchers therefore embark on other forms of experimental methods generally described as quasi-experimental methods.

Quasi-experiments

There is an unending controversy as to what constitutes a quasi-experiment. Given the little profit accruing from such a controversy, we would take a simple definition of that concept: any experiment that mimics as closely as possible the advantages of RCT (Muijs 2004 : 27). In quasi-experiments randomization is not possible (Muijs 2004 ). This makes it difficult to eliminate bias. The experimental group is already determined—they are the ones enjoying or experiencing the treatment of concern to the researcher. What the researcher does is to compare this group with another that is not experiencing the treatment. Often, the treatment is a government programme or some other kind of intervention out of the researcher’s control. Where it is possible to have another group to compare with, the researcher might work with data before treatment comparing that with data after treatment.

Take, for instance, the introduction of government-funded public examinations in some Nigerian prisons in 2019. Would the incidence of violence reduce in prisons because of this policy? A few years into the policy, a researcher might compare incidence of violence in Prison A where the policy is being implemented with Prison B where it is not being implemented. Or, where, for certain reasons that two-prison comparison is not possible, she might compare data on the incidence violence in Prison A before the policy with data on the incidence of violence in the same prison after the policy has been implemented.

Quasi-experiment templates consider space (spatial variation) and time (temporal variation) as important aspects that influence setting up of experimental research designs. Gerring ( 2007 ) and other scholars provide a variety of these templates. For instance, a researcher might be interested in explaining if and how a certain programme or policy, say a school feeding programme, increases students’ performance in national examinations. She can select two local government areas or sub-counties—one with a school feeding programme and the other without—and then compare school performances of students in both sub-counties and local government areas in national examination. It is important to ensure that the two cases (i.e. sub-counties or local government areas in this example) are similar in all other factors that might influence students’ performance in a national examination, the only difference being the presence of a school feeding programme in one and its absence in the other. The data can be collected by a variety of means—questionnaire, secondary data such as attendance registers, observation guide or any other that suits the research objective and question. A fruitful study of this type does not stop at showing that students in local government A where there is a school feeding programme perform better than their counterparts in local government B. That would be an interesting finding, but it leaves a lot unsaid. Rather, it should press on with an explanation of the causal mechanism—the pathway or trajectory by which the school feeding programme leads to better grades. This implies that what is largely categorized as quantitative study may require aspects of qualitative data to allow the researcher to get a complete picture of the issue under investigation.

Ojebode et al. ( 2016 ) attempted to explain the (in)effectiveness of community-based crime prevention practices in Ibadan, Nigeria. They selected two communities—one with a successful community-based crime prevention programme and another with a clearly unsuccessful one. These communities are similar in all the factors that matter to community-based crime prevention—population, ethnic mix, youth population, socio-economic status, and both have community-based crime prevention practices. Their puzzle was: why did the practice work so well in one community and fail so woefully in the other despite the similarities in these communities. Through different rounds of data collection and different instruments, their quantitative and qualitative analysis shows that the settlement patterns in the communities—dating several hundred years—perhaps explained the variation in the outcomes of the crime prevention practices.

Natural Experiments

Natural experiments take advantage of exogenous effect, that is, an intervention that is outside of the control of the researcher, which was also not intended to affect the outcome/dependent variable. The exogenous effect can be in the form of natural (such as a natural disaster), physical (like in the case of the colonial/government border) or historical event. They may also be a policy intervention. These were not intended for research or academic purposes. In other words, what becomes the treatment or causal factor happens through some “natural” occurrence or unplanned event. In some ways, these events may allow for observation of before and after they occurred. An example is Friedman et al. ( 2001 ) who carried out a kind of natural experiment during the 1996 Olympic games in Atlanta, Georgia. The researchers wanted to find out whether heavy traffic in the city was a cause of asthma in children. They made observations on how the city was organized during the 17 days of Olympics where the traffic rules changed. Small cars were forced onto alternative routes to leave main routes for mass transport, and this reduced traffic congestion on the major roads of the city. Through paediatric records (before and after Olympics), the study discovered 40% reduction in asthma attacks and emergency hospitalization. The researchers made a conclusion that traffic congestion contributes to paediatric asthma. This can be classified as a natural experiment, where the Olympics (manipulation/treatment) was not planned by the researcher and was exogenous (not related in any known way) to asthma. Such critically thought-out research can easily contribute to change in transport policies. Other studies, for instance, Daniel Posner’s on Chewas and Timbukas of Zambia and Malawi ( 2004 ), have used borders artificially created by colonial governments as boundaries of study groups. In his case, Posner shows how governments in two countries differently exploit similar ethnic compositions and the effect of this exploitation on inter-ethnic relations.

Non-experimental Quantitative Methods

Most quantitative researchers collect data using a standard questionnaire containing mostly close-ended questions. Some researchers may use a questerview, which combine both closed-ended and open-ended question. The latter is applicable when corroborative data or explanations to the closed-ended questions are needed. Survey questionnaires for this reason provide some standardized data that can be keyed into software for organization and analysis. The type of survey questionnaire depends on the nature of data that the researcher requires, the reach of the study population and ways in which the data is to be collected. One can decide to do telephone interviews, post the questionnaire, administer it online or have an ordinary written questionnaire.

Survey research considers a variety of factors including samples and sampling procedures, characteristics of the study population, among other issues. Surveys mainly apply probability sampling with an aim of giving all the elements a chance to be included in the study sample. This is the opposite of non-probability sampling those centres on purposive and convenient sampling. There are various sampling techniques in probability sampling, and these are available in various research methods books. Just to mention, some of the probability sampling approaches include simple random, stratified random, cluster, quota and multistage (see Muijs 2004 , 2011 ; Babbie 2004 ; Kothari 2004 ; Kumar 2011 ). For sample sizes, there are suggested formulas that researchers can apply for both finite and infinite populations.

Observational Studies

Observations are important for both qualitative and quantitative research. In quantitative research, observation is applied both as a research method and as a method of data collection. In qualitative research, observation is mostly categorized as a method of data collection and features in various research methods including ethnography, case study and action research. In quantitative studies, observational methods are important, for they enable a researcher to interact with the study environment and participants in a way that the questionnaire would not. Observational data for quantitative research is collected using standardized/structured observation schedules. A researcher can develop a descriptive observational record or a rating scale to help them collect observational data. This enables the researcher to observe and record the behaviour and activities in the selected study sites in a standardized way. Observations can also be made on existing reports within the institutions being studied, say for instance, school performance and statistical data collected from such reports (see Muijs 2004 ). In the end, the different methods may generate descriptive data of various types, that is, from open-ended and closed-ended descriptions. The selection of participants is also randomized to give all a chance to participate, and subsequently, those falling within the sample size are meant to represent the study population on which generalizations can be made.

Applied Quantitative Method

This method makes use of existing data sets. It applies analytical methods to facilitate description of data that has already been recorded and stored. Different research institutes store varied forms of data sets. These could be useful if a researcher is interested in analysing them with the purpose of achieving a certain research objective. For instance, one might be interested in understanding and describing the population growth trends. In such instances, one does not need to go to the field to collect fresh information when the national bureaux or offices of statistics have the data sets. All one needs is to get permission from relevant authorities to access such information. The challenge with using such data sets is that if they are erroneous in any way, then the errors are carried forth in the analysis. As Muijs ( 2004 ) indicates, the various quantitative research methods can be combined in a single study if this is necessary.

Mixed Methods in Public Policy Research

The advent of mixed-method research and the place that it currently occupies in social science research reinforce the arguments for the use of both traditions of qualitative and quantitative methods in public policy research. Statistics should be complemented and explained by meaning-making concepts, metaphors, symbols and descriptions from qualitative research to make sense of hard data. On the other hand, narratives on their own are not enough. Jones and McBeth ( 2010 : 330) show that despite the apparent power of stories in public policy, public policy studies have largely remained on the side-lines of the use narratives. The two scholars suggest the relevance of using a narrative policy framework as a methodological complement for positivists in the study of policy. Some scholars have also shown that for policy problems to be clearly defined, a narrative structure is needed. Narration, as Fischer ( 1998 ) and Stone ( 2002 : 138) explain, helps make sense of the socially constructed world that requires tangible solutions. Since qualitative approach may not be able to engage hypothesis testing to allow for replication and falsification (Jones and McBeth 2010 : 339), they should complement or be complemented by quantitative data.

Qualitative and quantitative methods have their own separate strengths. As noted above, qualitative research is about depth and qualitative is about breadth. This means, if a study requires both, then mixing the methods is important. Mixing methods therefore means a research problem requires both qualitative and quantitative data. Morse ( 1991 ) argued that triangulation of methods not only maximizes the strengths and minimizes those weaknesses of each approach, but also strengthens research results and contributes to theory and knowledge development.

Mixing research methods does not just imply mixing methods of data collection. A researcher must intentionally clarify which research methods (as discussed above) are applicable in their research to speak to qualitative and quantitative aspects, and by extension what methods of data collection will be used. Note that one research method may have many methods and tools data collection. If one is using ethnography, then participant observation, oral in-depth interviews, observations and focus group discussions are examples of applicable data collection methods. The various methods of data collection have their instruments/tools.

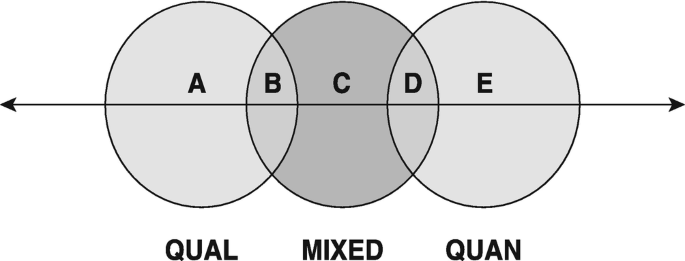

Mixing of methods entirely depends on the purpose for which the methods are mixed. This is determined by the research problem. Mixed research methods books provide a wide range of typologies of designing mixed-method research (see, for instance, Greene et al. 1989 ; Creswell and Clark 2011 ; Schoonenboom and Johnson 2017 ). Below is a simple illustration of the continuum for mixing methods (Fig. 4.2 ). A researcher can move from a purely quantitative or qualitative research method (A and E), towards integrating either quantitative (B) or qualitative (D) methods to the dominant method. A researcher can also design a fully mixed-method research (C). This is a simplified way of understanding how mixing can happen; there are other more complex typologies.

The mixed-method continuum. (Source: Teddlie and Yu 2007 : 84)

In public policy research, the mixing is important for various reasons. One might require results for complementary purpose, explanations to the statistical results, expansion of results from one domain (qualitative or quantitative) or confirmation of results. The dictates of mixing are found within the research problem and by extension research questions/objectives.

There is subtle blame game between bureaucrats and policy makers, on the one hand, and researchers, on the other hand, in Africa. While the latter accuse the former of not using the research they conduct, the former responds by claiming that many of the research do not speak to policy or societal issues and are thus not usable. They add that many of them are rendered in a language that is not accessible to non-academic actors. As a result, not a few policy decisions are based on political and other judgements rather than on sound research.

Our discussion so far suggests that the bureaucrats and policy makers may not be totally right in their accusation, but they are not totally wrong either. The preponderance of policy-appended research, and of solo-method research which offers little as a basis for policy, seems to justify their accusation. It is, therefore, important that public policy researchers weave their research around societal issues that are not only significant but also contemporary and topical, craft their design with the aim of policy engagement and stakeholder involvement, and adopt mixed methods as and when necessary, to provide findings and conclusion that command and compel policy actors’ attention.

Babbie, E. 2004. The Practice of Social Research . 10th ed. Belmont: Wandsworth.

Google Scholar

Bachman, R. 2007. Causation and Research Design. In The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice , ed. R. Bachman and R. Schutt, 3rd ed., 141–169. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Brewer, J. 2000. Ethnography . Buckingham: Philadelphia. Open University Press.

Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Edwards, M. 2004. Social Science Research and Public Policy: Narrowing the Divide. Occasional Paper 2/2004. Policy Paper #2. Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. Canberra. ASSA.

Elçi, A., and Devran, B.C. (2014). A Narrative Research Approach: The Experiences of Social Media Support in Higher Education, in P. Zaphiris (Eds.): Human-Computer Interaction, Part I, HCII 2014, LNCS 8523, pp. 36–42.

Fischer, F. 1998. Beyond Empiricism: Policy Inquiry in Postpositivist Perspective. Policy Studies Journal 26 (1): 129–146.

Article Google Scholar

Friedman, M., K. Powell, L. Hutwagner, L. Graham, and W. Teague. 2001. Impact of Changes in Transportation and Commuting Behaviours During the 1996 Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta on Air Quality and Childhood Asthma. JAMA. 285 (7): 897–905.

Gerring, J. 2007. Case Study Research Principles and Practices . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Greene, J.C., V.J. Caracelli, and W.F. Graham. 1989. Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11: 255–274.

Howlett, M. 2012. The Lessons of Failure: Learning and Blame Avoidance in Public Policymaking. International Political Science Review 33 (5): 539–555.

Huang, B.H. 2010. What Is Good Action Research? Why the Resurgent Interest? Action Research 8 (1): 93–109.

Johnson, Burke, and Larry B. Christensen. 2014. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches . Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Jones, M., and M. McBeth. 2010. A Narrative Policy Framework: Clear Enough to Be Wrong. The Policy Studies Journal 38 (2): 329–353.

Kothari, C. 2004. Research Methodology, Methods and Techniques . New Delhi: Wishwa Prakashan.

Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A Step by Step Guide for Beginners. London: Sage Publications Ltd. Third Edition.

Lemke, A., and J. Harris-Wai. 2015. Stakeholder Engagement in Policy Development: Challenges and Opportunities for Human Genomics. Genetics in Medicine 17 (12): 949–957.

Mead, L. 2005. Policy Research: The Field Dimension. Policy Studies Journal 33 (4): 535–557.

———. 2013. Teaching Public Policy: Linking Policy and Politics. JPAE 19 (3): 389–403.

Morse, M. 1991. Approaches to Qualitative and Quantitative Methodological: Triangulation. Qualitative Research 40 ( 1 ): 120–123.

Muijs, D. 2004. Doing Quantitative Research in Education . London: Sage Publications.

Book Google Scholar

———. 2011. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

Ojebode, A., Ojebuyi, B. R., Onyechi, N. J., Oladapo, O., Oyedele, O., and Fadipe, I. 2016. Explaining the Effectiveness of Community-Based Crime Prevention Practices in Nigeria. Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. http://www.ids.ac.uk/publication/explaining-the-effectiveness-of-community-based-crime-prevention-practices-in-ibadan-nigeria .

Osifo, C. 2015. Public Management Research and a Three Qualitative Research Strategy. Review of Pub. Administration and Management 3 (1): 149–156.

Oxman, A., S. Lewin, J. Lavis, and A. Fretheim. 2009. Support Tools for Evidence-Informed Health Policymaking (STP) 15: Engaging the Public in Evidence-Informed. Health Research Policy and Systems 7 (1): S15 Policymaking.

Oyedele, O., M. Atela, A. Ojebode. 2017. Two lessons for early involvement of stakeholders in research. https://i2insights.org/2017/11/14/early-stakeholder-involvement/

Posner, D. 2004. The Political Salience of Cultural Difference: Why Chewas and Tumbukas Are Allies in Zambia and Adversaries in Malawi. The American Political Science Review 98 (4): 529–545.

Roche, M. 2016. Historical Research and Archival Sources. In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography , ed. Iain Hay, 4th ed., 225–245. New York: Oxford University Press.

Saetren, H. 2005. Facts and Myths About Research on Public Policy Implementation: Out-of-Fashion, Allegedly Dead, But Still Alive and Relevant. Policy Studies Journal 33 (4): 559–582–559–582.

Schoonenboom, J., and B. Johnson. 2017. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. Köln Z Soziol 69 (Suppl 2): 107–131.

Stone, D. 2002. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, Revised Edition . 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton.

Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1994. Grounded Theory Methodology: An Overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research , ed. N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln, 273–285. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Teddlie, C., and F. Yu. 2007. Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology with Examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 1 (1): 77.

Tierney, W.G., and R.F. Clemens. 2011. Qualitative Research and Public Policy: The Challenges of Relevance and Trustworthiness. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research , ed. J. Smart and M. Paulsen, vol. 26, 57–83. Dordrecht: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

UK Cabinet Office. 2009. Professional Policy Making for the 21st Century. Report by Strategic Policy Making Team. September, 7(1).

Young, J. 2005. Research, Policy and Practice: Why Developing Countries Are Different. Journal of International Development 17: 727–734.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Religious Studies, Maseno University, Maseno, Kenya

Susan Mbula Kilonzo

Department of Communication and Language Arts, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Ayobami Ojebode

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Susan Mbula Kilonzo .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Political Science, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

E. Remi Aiyede

PASGR, Nairobi, Kenya

Beatrice Muganda

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Kilonzo, S.M., Ojebode, A. (2023). Research Methods for Public Policy. In: Aiyede, E.R., Muganda, B. (eds) Public Policy and Research in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99724-3_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99724-3_4

Published : 19 October 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-99723-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-99724-3

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Climate policy conflict in the U.S. states: a critical review and way forward

Joshua a. basseches.

1 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

Rebecca Bromley-Trujillo

2 Christopher Newport University, Newport News, USA

Maxwell T. Boykoff

3 University of Colorado, Boulder, USA

Trevor Culhane

4 Brown University, Providence, USA

5 Salem State University, Salem, USA

David J. Hess

6 Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA

7 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA

Rachel M. Krause

8 University of Kansas, Lawrence, USA

Harland Prechel

9 Texas A&M University, College Station, USA

J. Timmons Roberts

Jennie c. stephens.

10 Northeastern University, Boston, USA

Many U.S. states have taken significant action on climate change in recent years, demonstrating their commitment despite federal policy gridlock and rollbacks. Yet, there is still much we do not know about the agents, discourses, and strategies of those seeking to delay or obstruct state-level climate action. We first ask, what are the obstacles to strong and effective climate policy within U.S. states? We review the political structures and interest groups that slow action, and we examine emerging tensions between climate justice and the technocratic and/or market-oriented approaches traditionally taken by many mainstream environmental groups. Second, what are potential solutions for overcoming these obstacles? We suggest strategies for overcoming opposition to climate action that may advance more effective and inclusive state policy, focusing on political strategies, media framing, collaboration, and leveraging the efforts of ambitious local governments.

Introduction

Powerful interests have rebuffed climate policy efforts in the U.S., leading to decades of federal government inaction and heightened attention at the state level, where there has been comparative progress (Rabe 2007 ; Bromley-Trujillo et al. 2016 ). A great deal has been written about this shift to the states, and a robust literature on U.S. climate federalism has emerged (e.g., Karapin 2016 ; Rabe 2011 ; Thomson 2014 ; Woods 2021 ), including the significant climate policy action undertaken by states in the context of federal gridlock and policy rollbacks (Bromley-Trujillo and Holman 2020 ). For example, after President Trump announced U.S. withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, cities and states formed coalitions with major companies and institutions to proclaim, “We Are Still In” (We are still in 2021 ). Twenty-five governors joined the United States Climate Alliance (USCA), committing their states to the goals of the Paris Agreement (USCA 2019 ).

Although many states have adopted climate policies, there remain significant obstacles to passing strong and effective state-level climate policies rather than merely symbolic policies that set goals without mandates or that do not include penalties for noncompliance (Stokes 2020 ). Even in liberal states without significant fossil fuel production, policy efforts often fail to meet their emission reduction targets (Basseches 2019 ; Culhane et al. 2021 ). While there has been a proliferation of research on state-level climate and energy policy since the mid-2000s, scholarship using politics as an organizing, theoretical frame has only exploded in the last few years, making a synthesis geared toward this question of political obstacles quite timely (Woods 2021 ). This review thus focuses on two core questions:

First, what are the obstacles to adopting robust climate policy within U.S. states? We review the political structures and interest groups that slow or dilute action, and we also examine emerging tensions between climate justice and the more market-oriented approaches traditionally taken by many mainstream environmental groups. Furthermore, we explore the ways that conservative countermovements have shaped public opinion and elite decision-making on climate policy.

Second, what are potential solutions for overcoming these obstacles? Rather than ending with a mere summation and call for more research, we distill some strategies for overcoming opposition to climate action that may advance more effective and inclusive state policy. We suggest strategies to advance ambitious solutions, with a focus on political strategies, media framing, collaboration, and leveraging the efforts of ambitious local governments.

This review is structured in three main sections: (1) an overview of state climate policy efforts, (2) obstacles to robust state-level climate mitigation policy, and (3) solutions to maximize state-level climate policy effectiveness. Although our focus is entirely on the U.S., many of the obstacles and strategies for overcoming them are not unique to the U.S., and this review is likely to be relevant for researchers, policymakers, and advocates in other countries and at other levels of government. We begin with a brief overview of state climate policy efforts before moving to our discussion of obstacles and solutions.

An overview of state climate efforts

The focus of this paper is on climate mitigation policy, which can take many forms including broad-based climate policies, transportation policies, and electricity sector policies that have climate change implications (Grant et al. 2014 ; Bromley-Trujillo and Holman 2020 ). In the U.S., states have led in this area since the early 2000s as detailed in scholarly work (e.g., Rabe 2004 ; Matisoff and Edwards 2014 ; Bromley-Trujillo and Holman 2020 ).

These studies demonstrate a wide range of policy activity that centers on broad-based climate change efforts such as climate action plans, carbon cap-and-trade, and GHG reduction targets, transportation sector policies including low carbon and alternative fuel standards, and electricity sector policies such as renewable portfolio standards, net metering, and decoupling.

While it would be impossible to discuss in detail every policy states have adopted here, we begin by presenting an overview of key policy instruments states have used with an emphasis on the more frequently adopted policies across the aforementioned categories (broad-based climate efforts, transportation sector and electricity sector policies). Table Table1 1 gives a description of state climate policy instruments, as identified by the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, which emphasize some of the more comprehensive state climate policies to date.

State climate policy innovations

Source: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions

Figure 1 shows the frequency of these policy adoptions by 2021, demonstrating considerable variance in total adoptions.

Key climate policy enactments across states by 2021

These policies are not the only efforts states engage in. For example, when it comes to the electricity sector and energy efficiency, 20 states have enacted a green building standard requiring public buildings to meet LEED or related standards (DSIRE 2021 ; May and Koski 2007 ). Another 15 states have adopted an appliance efficiency standard that goes beyond federal requirements. With regard to transportation, 45 states have adopted some form of incentive for hybrid/electric vehicles to date (Hartman and Shields 2021 ).

Across state legislatures in 2020, policy has centered on environmental justice and equity bills, development of electric vehicle infrastructure, and electrification of the transportation sector through tax incentives (Andersen et al. 2021 ). Despite these significant advances, it is clear that state policy actions are highly variable and currently insufficient to meet U.S. climate mitigation goals. Variability is evident when looking at RPS policies, which have been adopted by 37 states with considerable differences in stringency. For instance, South Carolina has a modest requirement of 2% generation capacity from renewable energy by 2021, compared to California, which requires 100% of electricity from renewable sources by 2045. Moreover, several states have engaged in policy retrenchment in recent years by making reductions to their state RPS targets (e.g., Ohio) or adjusting their net metering programs through phase outs, or the introduction of fees (e.g., Kentucky, Indiana) (Bromley-Trujillo and Holman 2020 ). Absent more consistent and stringent state policy coverage, the U.S. cannot meet climate mitigation objectives, necessitating efforts to reduce obstacles to more robust state climate policy activity.

Obstacles to subnational climate policy

In this section, we discuss the obstacles to more robust and widespread state-level climate policy. We examine four obstacle categories: (1) governance and institutions, (2) media and public opinion, (3) industry and interest group opposition, and (4) divided pro-climate coalitions.

Governance and institutions

Political party governance and institutional arrangements in state government are important obstacles to climate policy action, particularly as environmental issues have become more politically polarized over time (Daniels et al. 2012 ). Democratic control of state governments facilitates climate policy adoption while Republican leadership acts as a veto point for climate legislation, often necessitating a Democrat trifecta to achieve bill passage (Bromley-Trujillo et al. 2016 ; Coley & Hess 2012 ; Trachtman 2020 ). There is also evidence to suggest a “counter-partisan response” at the state level (Miras and Rouse 2021 ); that is, when one party controls the federal government, the opposing party may become emboldened to act at the state-level (Bromley-Trujillo and Holman 2020 ).

State institutional configurations such as legislative professionalism and administrative capacity also play an important role. Legislative professionalism, which refers to variation in time in session, salary, and staff in state legislatures (Squire 2007 ), can play a meaningful role in the quality and quantity of policy adopted by state governments. For climate change, it is particularly important because this issue is technical and complex. Professionalized legislatures tend to be more adept at crafting innovative legislation around complex issues, while refuting anti-climate “model legislation” from groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a conservative-business alliance known for providing anti-climate legislation for state legislators to formally introduce (Hertel-Fernandez 2014 ; Jansa et al. 2019 ).

Research also shows that the organization of the executive branch has an important effect on policy outcomes (Karapin 2016 ; Raymond 2016 ). To illustrate, Carlson ( 2017 ) demonstrates that administrative/regulatory capacity has been key to California’s climate policy innovation. Meckling and Nahm ( 2018 ) argue that when state legislatures delegate significant policymaking authority to executive branch agencies, the latter tend to be relatively depoliticized and less susceptible to powerful interest groups. However, the success of administrative delegation is contingent on administrative capacity (Meckling and Nahm 2018 ).

Another important institutional consideration is the formal powers afforded to majority party leaders and committee chairs in legislative bodies (e.g., Anzia and Jackman 2013 ; Anderson et al. 2016 ). Formal powers are in part a product of other institutional arrangements, such as the presence or absence of term limits (Carey et al. 2006 ; Mooney 2012 ; Shay 2020 ). Basseches ( 2019 ) shows that the concentration of institutional power in the hands of majority party leadership, even when the majority party is Democratic, facilitates access and influence for business actors while limiting it for environmental groups.

Media and public opinion

Media coverage and public opinion around climate change also present obstacles to robust climate policy in the case where public concern is low (Bromley-Trujillo and Poe 2020 ; Bromley-Trujillo et al. 2019 ) and when media coverage frequency and content fail to raise the issues’ salience (Boykoff et al. 2021 ).

Media representations are powerful conduits of climate science and policy (mis)information. Moreover, media coverage of climate change, which is heavily driven by elite cues, is likely to shape public attitudes (Carmichael and Brulle 2016 ). Research on media portrayals of science-based issues shows that quantity and content of media coverage influences state-level agenda-setting (Bromley-Trujillo and Karch 2019 ). As such, when coverage presents climate science as uncertain, or fails to engage the views of different subgroups (Howarth and Black 2015 ), that coverage can shift climate change off of public and governmental agendas (Boykoff et al. 2021 ).

Public opinion also emerges as a barrier to climate action through influence on state legislative agendas (Bromley-Trujillo et al. 2019 ) and broader public discourse. Despite the scientific consensus on climate change (IPCC 2014 ), public attitudes are highly polarized (Guber 2013 ; McCright and Dunlap 2011 ). Variation in climate attitudes tends to fall in four primary areas: public understanding and awareness, the existence of climate change, issue salience, and public policy (Egan and Mullin 2017 ). On understanding and awareness, a 2020 Yale survey showed that only a slight majority (55%) of the public believes that “most scientists think global warming is happening,” which does not reflect the current scientific consensus (Leiserowitz et al. 2020 ; Egan and Mullin 2017 ). Furthermore, while a large majority of the public (72%) say climate change is happening, only a smaller majority (57%) indicate that it is human-caused (Marlon et al. 2020 ).

With respect to issue salience (i.e., the level of importance placed on climate change), U.S. residents have historically seen climate change as a low governmental priority (McCarthy 2016 ), especially compared to the populaces of other countries (Egan and Mullin 2017 ). Attitudes toward specific climate policies are mixed, and sensitive to question wording. Support tends to be high for renewable energy investment and broad climate policy pronouncements (Bowman et al. 2016 ; Stoutenborough et al. 2014 ), but lower for more complex policies and for those imposing costs (Stokes and Warshaw 2017 ).

Partisan differences are also significant barriers to climate policy action. Republicans are more likely to believe that climate change does not exist, is the result of natural processes, or is too costly to address (Hornsey et al. 2016 ). Additionally, factors shown to influence climate attitudes (e.g., extreme weather experience and scientific knowledge) are moderated by partisanship (Shao et al. 2017 ). Direct experience with extreme weather is perceived differently by Republicans, Independents, and Democrats, with Republicans typically understating the seriousness of their experiences, and Independents most sharply swinging with recent weather (Hamilton 2011 ; Hamilton and Stampone 2013 ; Shao et al. 2017 ; Myers et al. 2012 ).

Industry and interest group opposition

A third source of climate policy obstacles are interest groups, including fossil fuel and business lobbies, electric utilities, and a broad conservative countermovement.

Fossil fuel lobbying, corporate political activity, and corporate-state relations

U.S. federalism delegates immense authority to states when it comes to climate and energy policy, and state efforts have expanded in the face of federal inaction (Karapin 2020 ; Thomson 2014 ; Rabe 2011 ). This creates new opportunities for corporations and their lobbyists to influence climate policy. Initially, the increased authority of states prompted researchers to anticipate a “race to the top” with some states setting higher environmental standards (Fiorino 2006 ). However, subsequent research showed that the political economy of the environment often generates a “race to the bottom,” with some states competing for fossil fuel companies to develop their energy resources (Rabe 2007 , 2013 ; Davis 2012 ; Cook 2017 ). Furthermore, after states become dependent on employment and tax revenues from the fossil fuel companies, they tend to make concessions to them. Wingfield and Marcus ( 2007 ) show that many of the states most dependent on fossil fuel industries have among the weakest environmental policies (e.g., Wyoming, Alabama, North Dakota, West Virginia, Louisiana).

The political alignment of subnational states and the fossil fuel sector is also motivated by economic co-dependence between state governments and the fossil fuel sector, resulting in states’ protecting business interests in order to advance the states’ economic growth and development agendas. However, this strategy can create conflict with neighboring states where air quality is adversely affected by high-polluting states. To mediate this conflict between states, the Obama Administration enacted the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule to limit the drift of airborne pollution across state borders. This policy quickly became a contested terrain between states and the federal government over jurisdiction, and it was resolved by the federal government making concessions to high-polluting states (Prechel 2012 ). Economic co-dependence also results in other actions by states that benefit the fossil fuel industry. To illustrate, several Republican lawmakers in Texas recently proposed legislation that threatened to divest the state’s more than $100 billion in retirement funds from banks and asset managers that boycott the fossil fuel sector (Douglas 2021 ).

Further, relaxed antitrust enforcement at the federal level has permitted the emergence of giant fossil fuel corporations (e.g., ExxonMobil, Koch Industries), which have virtually unlimited capital to spend on lobbying, political contributions, and media campaigns to oppose climate legislation. To illustrate, the Koch Brothers spent some of their $80 billion in wealth on an extensive media campaign to discredit scientific research on environmental pollution (Mayer 2017 ). Furthermore, during the 2019–2020 federal election cycle, the Koch Brothers’ Super PAC, Americans for Prosperity Action, spent more than $47.7 million on federal elections in disclosed contributions compared to less than $41.5 million for all contributions by the largest 20 environmental organizations (Open Secrets 2020a , 2020b ). Moreover, historically, Americans for Prosperity Action has spent much more on undisclosed contributions (i.e., dark money), which reached $407 million during the 2012 federal election (Fang 2014 ).

Some of the most active anti-climate policy trade groups include state chapters of the American Petroleum Institute, the Oil Heat Institute, and associations of manufacturers and state Chambers of Commerce. Trade organizations are often dominated by a few of the largest firms, which have key positions on boards of directors, experts to serve on policy-drafting committees, and influence over hiring in state governments. Interviews with Chamber of Commerce representatives and observations of testimony show substantial variation in major industry group positions, though they generally resist new taxes or regulations (Culhane et al. 2021 ).

Despite their massive resources, fossil fuel corporations and trade groups do not have the expertise to address every environmental issue. Thus, many are members of the neoliberal policy organization, ALEC, which is committed to small government and unregulated markets. ALEC is dominated by the largest corporations because it charges high membership dues in exchange for model legislation that it distributes to state lawmakers. ALEC also operates as a networking mechanism that facilitates connections between corporations with shared interests (Prechel 2021a ). For example, Koch Industries created a political coalition with the former Enron Corp. and succeeded in enacting model legislation in twenty-four U.S. states (Hertel-Fernandez 2019 ).

Given that electricity accounts for more than a quarter of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions (U.S. EPA 2018 ), electric utilities are critical actors in state-level climate policymaking (Prechel 2012 ; Basseches 2020 ; Isser 2015 ; Stokes 2020 ). The U.S. electric sector is complex, with variation across states in the degree to which utilities are private corporations (known as “investor-owned utilities”) or customer-owned utilities, which can either be government-owned or electricity cooperatives (Greenberg & McKendry 2021 ). However, most U.S. residents receive electricity from investor-owned utilities (IOUs) rather than from public or cooperative organizations (U.S. Energy Information Administration 2017 ). States vary in the degree to which they undertook efforts to break up vertically integrated utilities and introduce retail competition beginning in the late 1990s (Borenstein and Bushnell 2015 ), and this variation led to differences in how these actors came to view climate policy proposals (Basseches 2020 ).