Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Leadership: A Comprehensive Review of Literature, Research and Theoretical Framework

2020, Leadership: A Comprehensive Review of Literature, Research and Theoretical Framework. In: Journal of Economics and Business, Vol.3, No.1, 44-64.

This paper provides a comprehensive literature review on the research and theoretical framework of leadership. The author illuminates the historical foundation of leadership theories and then clarifies modern leadership approaches. After a brief introduction on leadership and its definition, the paper mentions the trait theories, summarizes the still predominant behavioral approaches, gives insights about the contingency theories and finally touches the latest contemporary leadership theories. The overall aim of the paper is to give a brief understanding of how effective leadership can be achieved throughout the organization by exploring many different theories of leadership, and to present leadership as a basic way of achieving individual and organizational goals. The paper is hoped to be an important resource for the academics and researchers who would like to study on the leadership field.

Related Papers

Sonali Sharma

Shanlax International Journal of Commerce

vivek deshwal

Journal of Leadership and Management; 2391-6087

Betina Wolfgang Rennison

The theoretical field of leadership is enormous-there is a need for an overview. This article maps out a selection of the more fundamental perspectives on leadership found in the management literature. It presents six perspectives: personal, functional, institutional, situational, relational and positional perspectives. By mapping out these perspectives and thus creating a theoretical cartography, the article sheds light on the complex contours of the leadership terrain. That is essential, not least because one of the most important leadership skills today is not merely to master a particular management theory or method but to be able to step in and out of various perspectives and competently juggle the many possible interpretations through which leadership is formed and transformed.

Fila Bertrand, Ph.D.

Leadership and the numerous concepts on leadership styles have been subjects of both study and debate for years. Every leader approaches challenges differently, and his or her personality traits and life experiences greatly influence his or her leadership style and the organizations they lead. Furthermore, leadership is a notion resulting from the interaction between a leader and followers, and not a position or title within the organization. This essay examines some of the contemporary theories of leadership, the leadership qualities and traits necessary to be successful in today's competitive environment, the impact of leadership to the organization, and the importance of moral leadership in today's world.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE

Vivian A . Ariguzo , Michael okoro

Diverse views have emerged on leadership definitions, theories, and classification in academic discourse. The debate and conscious efforts made to clarify leadership actively has generated socio-cultural and organizational research on its styles and behaviours. This study seeks to identify the theoretical views of various academic scholars on some of the main theories that emerged during the 20 th century include: the Thomas Carlyle's Great Man theory, Gordon Allport's Trait theory, Fred Fiedler's Contingency theory, Hersey and Blanchard Situational Theory, Max Weber's Transactional theory, MacGregor Burns' Transformational theory, Robert Houses' Path-goal theory, and Vroom and Yetton's Participative theory. Empirical discourse that revealed findings of academic scholars have enshrined the import of leadership in organizations. Various academic literature that already have been subject to validity and reliability tests were reviewed and used to arrive at the findings. The study postulated the Mystical-man theory after a rich discourse and recommended it as the ideal theory for all Christian leaders to adopt as it is assumed to provide above average performance at all times, irrespective of followership behaviour.

Neil D . Walshe

The three topics of this volume—leadership, change, and organization development (OD)—can be viewed as three separate and distinct organizational topics or they can be understood as three distinct lenses viewing a common psycho-organizational process. We begin the volume with a comprehensive treatment of leadership primarily because we view leadership as the fulcrum or crucible for any significant change in human behavior at the individual, team, or organizational level. Leaders must apply their understanding of how to effect change at behavioral, procedural, and structural levels in enacting leadership efforts. In many cases, these efforts are quite purposeful, planned, and conscious. In others, leadership behavior may stem from less-conscious understandings and forces. The chapters in Part I: Leadership provide a comprehensive view of what we know and what we don’t know about leadership. Alimo-Metcalfe (Chapter 2) provides a comprehensive view of theories and measures of leadershi...

Transylvanian review of administrative sciences

Cornelia Macarie

The paper endeavors to offer an overview of the major theories on leadership and the way in which it influences the management of contemporary organizations. Numerous scholars highlight that there are numerous overlaps between the concepts of management and leadership. This is the reason why the first section of the paper focuses on providing an extensive overview of the literature regarding the meaning of the two aforementioned concepts. The second section addresses more in depth the concept of leadership and managerial leadership and focuses on the ideal profile of the leader. The last section of the paper critically discusses various types of leadership and more specifically modern approaches to the concept and practices of leadership.

An organization constitute of a diverse group of individuals, working together towards a specified common goal. A robust organizational framework is based upon specified values, believes and positive culture accompanied by effective leaders and managers that are expected to understand their roles and responsibilities towards both the employees and the management of the organization. Culture is recognized as "the glue" that binds a group of people together (Martin and Meyerson, 1988). Therefore, organizational culture entails intelligent and great leaders who value and believe in nurturing employees and appreciate their active participation in the progression of the company (Balain & Sparrow 2009). With that said, management is also one of the crucial organisational activities that is necessary to ensure the coordination of individual efforts as well as the organization's resources and activities. Lastly, leadership in itself is a vital bond that connects effective management and splendid organizational culture. However, for a long time, there has been a disconnect and inconsistency on what entails leadership and management. We identify with scholars who questioned the overlying issues regarding the significant concepts of leadership and management (Schedlitzki & Edwards,2014). It is therefore paramount to understand how leadership and management play critical roles in shaping up contemporary organizations, fundamentally appreciating the applicability that arises with the various leadership styles and management theories while apprehending their link to organization culture.

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development

Prof. Dr. Satya Subrahmanyam

This research article was motivated by the premise that no corporate grows further without effective corporate leaders. The purpose of this theoretical debate is to examine the wider context of corporate leadership theories and its effectiveness towards improving corporate leadership in the corporate world. Evolution of corporate leadership theories is a comprehensive study of leadership trends over the years and in various contexts and theoretical foundations. This research article presents the history of dominant corporate leadership theories and research, beginning with Great Man thesis and Trait theory to Decision process theory to various leadership characteristics. This article also offers a convenient way to utilize theoretical knowledge to the practical corporate situation.

Public Administration Review

Montgomery Van Wart

RELATED PAPERS

Analysis of the economic adaptation of …

Jan Åge J G Riseth

International Journal of Production Economics

Saad A Javed

Wiwat Arkaravichien

chinonso eze

Francesco Saverio Minervini

The Nebraska Educator

Aprille Phillips

Altangerel Lkhamsuren

2010 IEEE 24th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops

altair santin

… : Revista de Ciencias Sociales del Instituto …

José María Lahoz Finestres

Heart Rhythm

Ayman mourad

Proceedings of the Workshop on Multimodal Understanding of Social, Affective and Subjective Attributes - MUSA2 '17

Delia Fernandez

Journal of Business Management & Economics

Areghan Isibor

2007 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing

fatma arslan

Developmental medicine and child neurology

Ann Carrellas

Abdeslam Elakkad

Inorganic Chemistry

Yang shao-horn

Libro de Contribuciones 2023 - 9° Congreso Internacional de Innovación Educativa

Maribel Veas

Applied sciences

Fabrizio Bambini

Nimas Safitri

Disease Markers

Mary Ritter

Indian Journal of Clinical Anatomy and Physiology

Innovative Publication

Revista Juridica Internacional

Carlos Domínguez Scheid

Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition

Gigi Veereman-wauters

56AK - Fauzan amin

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Leadership agility in the context of organisational agility: a systematic literature review

- Published: 17 April 2024

Cite this article

- Latika Tandon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9937-072X 1 ,

- Tithi Bhatnagar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8469-7658 1 , 2 &

- Tanushree Sharma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7727-0258 3

65 Accesses

Explore all metrics

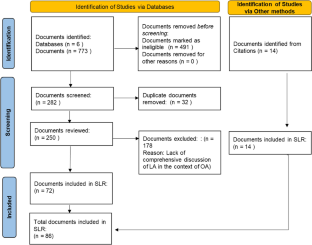

Organisations across the globe are looking to become agile and are seeking leaders to guide their transformation to agility. This paper conducts a systematic literature review across eighty-six papers spanning over 25 years (1999–2023), to develop an overview of how leadership agility is conceptualized in the context of organisational agility in the extant literature. This systematic review was conducted using the PRISMA framework. The databases searched for the review were: EBSCO, Emerald Insight, JStor, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, and Scopus. The data thus collected was organised and integrated using reflective thematic synthesis. Literature suggests that leadership agility is one of the key dimensions to foster organisational agility, though challenging in practice and difficult to implement. Based on the analysis of extant literature, this paper identifies four emergent themes of leadership agility: Leadership Agility Mindsets; Leadership Agility Competencies; Leadership Agility Styles; and Leadership Organisational Agility Functions . This study has conceptualized a framework of leadership agility in the context of organisational agility, anchored in the interplay of the emergent themes and their categories, contributing to leadership agility research, and promoting its adoption by the practitioners.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Agile Leadership and Bootlegging Behavior: Does Leadership Coping Dynamics Matter?

Positive Leadership: Moving Towards an Integrated Definition and Interventions

Leadership and Change Management: Examining Gender, Cultural and ‘Hero Leader’ Stereotypes

Data availability.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Adhiatma A, Fachrunnisa O, Lukman N, Majid MNA (2023) Comparative study on workforce transformation strategy and SME policies in Indonesia and Malaysia. Eng Manage Prod Ser 15(4):1–11. https://doi.org/10.2478/emj-2023-0024

Article Google Scholar

Ahmed J, Mrugalska B, Akkaya B (2022) Agile management and VUCA 2.0 (VUCA-RR) during industry 4.0. In: Akkaya B, Guah MW, Jermsittiparsert K, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Kaya Y (eds) Agile management and VUCA-RR: opportunities and threats in industry 4.0 towards society 5.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80262-325-320220002

Chapter Google Scholar

Akkaya B, Tabak A (2020) The link between organizational agility and leadership: a research in science parks. Acad Strateg Manag J 19:1–17

Google Scholar

Akkaya B, Waritay-Guah M, Jermsittiparsert K, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Kaya-Koçyiğit Y (2022) Agile management and VUCA-RR opportunities and threats in industry 4.0 towards society 5.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley

Book Google Scholar

Akkaya B, Üstgörül S (2020) Leadership styles and female managers in perspective of agile leadership. Agile Bus Leadersh Methods Ind 4:121–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80043-380-920201008

Akkaya B, Sever E (2022) Agile leadership and organization performance in the perspective of VUCA. In: Post-pandemic talent management models in knowledge organizations. IGI Global

Aldianto L, Anggadwita G, Permatasari A, Mirzanti IR, Williamson IO (2021) Toward a business resilience framework for startups. Sustainability (switzerland) 13(6):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063132

Appelbaum SH, Calla R, Desautels D, Hasan L (2017a) The challenges of organizational agility (part 1). Ind Commer Train 49(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-05-2016-0027

Appelbaum SH, Calla R, Desautels D, Hasan LN (2017b) The challenges of organizational agility: part 2. Ind Commer Train 49(2):69–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-05-2016-0028

As Global Growth Slows, Developing Economies Face Risk of ‘Hard Landing.’ (2022) The World Bank

Asseraf Y, Gnizy I (2022) Translating strategy into action: the importance of an agile mindset and agile slack in international business. Int Bus Rev 31(6):102036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2022.102036

Attar M, Abdul-Kareem A (2020) The role of agile leadership in organisational agility. In: Akkaya B (ed) Agile business leadership methods for industry 40. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80043-380-920201011

Avery CM (2004) The mindset of an agile leader. Cut IT J 17(6):22–27

Balázs V, Éva S (2023) Unlocking the key dimensions of organizational agility: a systematic literature review on leadership, structural and cultural antecedents. Soc Econ 45. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2023.00023

Benchea L, Ilie AG (2023) Preparing for a new world of work: leadership styles reconfigured in the digital age. Eur J Interdiscip Stud 15(1):135–143. https://doi.org/10.24818/ejis.2023.10

Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D (2016) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Brandt EN, Kjellström S, Andersson A-C (2019) Transformational change by a post-conventional leader. Leadersh Org Dev J 40(4):457–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0273

Buttigieg SC, Cassia MV, Cassar V (2023) The relationship between transformational leadership, leadership agility, work engagement and adaptive performance: a theoretically informed empirical study. In: Chambers N (ed) Research handbook on leadership in healthcare. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 235–251

Chakraborty T, Awan TM, Natarajan A, Kamran M (eds) (2023) Agile leadership for industry 4.0: an indispensable approach for the digital era, 1 edn. AAP/Apple Academic Press

Chatwani N (2019) Agility revisited. In: Chatwani N (ed) Organisational agility. Springer International Publishing, Berlin, pp 1–21

De Smet A, Lurie M, St George A (2018) Leading agile transformation: The new capabilities leaders need to build 21st-century organizations. Mckinsey.com, October 2018.

Denning S (2016) Agile’s ten implementation challenges. Strategy Leadersh 44(5):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-08-2016-0065

Denning S (2018a) Succeeding in an increasingly Agile world. Strategy Leadersh 46(3):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-03-2018-0021

Denning S (2018b) The role of the C-suite in Agile transformation: the case of Amazon. Strategy Leadersh 46(6):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-10-2018-0094

Denning S (2019a) Lessons learned from mapping successful and unsuccessful Agile transformation journeys. Strategy Leadersh 47(4):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-04-2019-0052

Denning S (2019b) The ten stages of the Agile transformation journey. Strategy Leadersh 47(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-11-2018-0109

Doz Y, Kosonen M (2008) The dynamics of strategic agility: Nokia’s rollercoaster experience. Calif Manage Rev 50(3):95–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166447

Dulay S (ed) (2023) Empowering educational leaders: How to thrive in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. Peter Lang, Lausanne

Eilers K, Peters C, Leimeister JM (2022) Why the agile mindset matters. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 179:121650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121650

Esamah A, Aujirapongpan S, Rakangthong NK, Imjai N (2023) Agile leadership and digital transformation in savings cooperative limited: impact on sustainable performance amidst COVID-19. J Hum Earth Future 4(1):36–53. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2023-04-01-04

Fachrunnisa O, Adhiatma A, Lukman N, Ab-Majid MN (2020) Towards SMEs’ digital transformation: the role of agile leadership and strategic flexibility. J Small Bus Strategy 30:65–85

Felipe CM, Roldán JL, Leal-Rodríguez AL (2016) An explanatory and predictive model for organizational agility. J Bus Res 69(10):4624–4631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.014

Fernandes V, Wong W, Noonan M (2023) Developing adaptability and agility in leadership amidst the COVID-19 crisis: experiences of early-career school principals. Int J Educ Manag 37(2):483–506. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2022-0076

Garton E, Noble A (2017) How to make agile work for the C-Suite. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/07/how-to-make-agile-work-for-the-c-suite

Govuzela S, Mafini C (2019) Organisational agility, business best practices and the performance of small to medium enterprises in South Africa. S Afr J Bus Manag 50(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v50i1.1417

Gren L, Ralph P (2022) What makes effective leadership in agile software development teams? In: Proceedings of the 44th international conference on software engineering, pp. 2402–2414. https://doi.org/10.1145/3510003.3510100

Gren L, Lindman M, Stray V, Hoda R, Paasivaara M, Kruchten P (2020) Agile processes in software engineering and extreme programming. 21st International Conference on Agile Software Development XP 2020 Copenhagen Denmark June 8–12, 2020 Proceedings What an Agile Leader Does: The Group Dynamics Perspective. Springer, Cham, pp 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49392-9

Grześ B (2023) Managing an agile organization – key determinants of orgnizational agility. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology Organization and Management Series. 2023(172). https://doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2023.172.17

Hartney E, Melis E, Taylor D, Dickson G, Tholl B, Grimes K, Chan M-K, Van Aerde J, Horsley T (2022) Leading through the first wave of COVID: a Canadian action research study. Leadersh Health Serv 35(1):30–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-05-2021-0042

Hill L (2020) Being the agile boss. MIT SMR, Fall (2020)

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2005) Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. Choice Rev 42(10):42–5937. https://doi.org/10.5860/CHOICE.42-5937

Holbeche L (2018) Organisational effectiveness and agility. J Organ Eff People Perform 5(4):302–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-07-2018-0044

Holbeche L (2019) Designing sustainably agile and resilient organizations. Syst Res Behav Sci 36(5):668–677. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2624

Horney N, Pasmore B, O’Shea T (2010) Leadership agility: a business imperative for a VUCA world. People Strategy 33(4):34

Howieson B, Grant K (2022) Wicked leadership development for wicked problems. In: Holland P, Bartram T, Garavan T, Grant K (eds) The emerald handbook of work, workplaces and disruptive issues in HRM. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-779-420221030

Jansen JJP, Vera D, Crossan M (2009) Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: the moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh Q 20(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.008

Joiner B (2009) Creating a culture of agile leaders: a developmental approach. People Strategy 32(4):28–35

Joiner B (2012) How to build an agile leader. Chief Learn off 11(8):48–51

Joiner B, Josephs S (2007) Developing agile leaders. Ind Commer Train 39(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850710721381

Jones S, Cass D (2022) Agile leadership: eight steps to becoming an agile team leader. Eff Exec 25(1):7–12

Kaya Y (2023) Agile leadership from the perspective of dynamic capabilities and creating value. Sustainability 15(21):15253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115253

Keleş HN (2023) Agile leadership in schools. In: Empowering educational leaders: How to thrive in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. Peter Lang AG

Konrad-Maerk M, Gfrerer A, Hutter K (2022) From transformational to agile leadership: what future skills it takes to act as agile leaders. Acad Manag Proc 2022(1):12343. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2022.12343abstract

Kumar S, Ray S (2023) Moving towards agile leadership to help organizations succeed. IUP J Soft Skills 17(1):2023. ProQuest

Lang D, Rumsey C (2018) Business disruption is here to stay: What should leaders do? Qual Access Success 19(S3):35–40

Leslie J (2015) The leadership gap: what you need, and still don’t have, when it comes to leadership talent. Cent Creative Leadersh. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2015.1014 (2015).

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339(1):b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

Luthia M (2023) Agile Leadership for Industry 4.0. An Indispensable Approach for the Digital Era. Apple Academic Press, New York

MacLean D, MacIntosh R, Seidl D (2015) Rethinking dynamic capabilities from a creative action perspective. Strateg Organ 13(4):340–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127015593274

McKenzie J, Aitken P (2012) Learning to lead the knowledgeable organization: developing leadership agility. Strateg HR Rev 11(6):329–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/14754391211264794

McPherson B (2016) Agile, adaptive leaders. Hum Resour Manag Int Dig 24(2):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-11-2015-0171

Menon S, Suresh M (2021) Factors influencing organizational agility in higher education. Benchmark Int J 28(1):307–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-04-2020-0151

Meyer R, Meijers R (2017) Leadership Agility: Developing Your Repertoire of Leadership Styles, 1st edn. Routledge, London

Modi S, Strode D (2020) Leadership in agile software development: a systematic literature review. In: ACIS 2020 proceedings. 55. https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2020/55

Morton J, Stacey P, Mohn M (2018) Building and maintaining strategic agility: an agenda and framework for executive IT leaders. Calif Manage Rev 61(1):94–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125618790245

Muafi M, Diamastuti E, Pambudi A (2020) Service innovation strategic consensus: a lesson from the Islamic banking industry in Indonesia. J Asian Finance Econ Bus 7(11):401–411. https://doi.org/10.13106/JAFEB.2020.VOL7.NO11.401

Muafi M, Uyun Q (2019) Leadership agility, the influence on the organizational learning and organizational innovation and how to reduce imitation orientation. Int J Qual Res 13(2):467–484. https://doi.org/10.24874/IJQR13.02-14

Mukherjee T (2023) The power of empathy: rethinking leadership agility during transition. In: Agile leadership for industry 4.0. An indispensable approach for the digital era , 1st edn. Apple Academic Press

Naslund D, Kale R (2020) Is agile the latest management fad? A review of success factors of agile transformations. Int J Qual Serv Sci 12(4):489–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-12-2019-0142

Oliveira SRM, Saraiva MA (2023) Leader skills interpreted in the lens of education 4.0. Procedia Comput Sci 217:1296–1304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.327

Orski K (2017) What’s your agility ability? Nurs Manage 48(4):44–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000511922.75269.6a

O’Brien E, Robertson P (2009) Future leadership competencies: from foresight to current practice. J Eur Ind Train 33(4):371–380. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590910959317

O’Reilly CA, Tushman ML (2008) Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res Organ Behavior 28:185–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.06.002

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Paul J, Criado AR (2020) The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int Bus Rev 29(4):101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101717

Pesut DJ, Thompson SA (2018) Nursing leadership in academic nursing: The wisdom of development and the development of wisdom. J Prof Nurs 34(2):122–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.11.004

Piwowar-Sulej K, Sołtysik M, Różycka-Antkowiak JŁ (2022) Implementation of management 3.0: its consistency and conditional factors. J Organ Change Manage 35(3):541–557. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-07-2021-0203

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lanc Univ https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1018.4643

Psychogios A (2022) Re-conceptualising total quality leadership: a framework development and future research agenda. TQM J. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-01-2022-0030

Rigby D, Elk S, Steve B (2020) The agile C-suite a new approach to leadership for the team at the top. Harv Bus Rev

Roux M, Härtel CEJ (2018) The cognitive, emotional, and behavioral qualities required for leadership assessment and development in the new world of work. In: Petitta L, Härtel CEJ, Ashkanasy NM, Zerbe WJ (eds) Research on emotion in organizations, vol 14, pp 59–69. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1746-979120180000014010

Rožman M, Oreški D, Tominc P (2023a) A multidimensional model of the new work environment in the digital age to increase a company’s performance and competitiveness. IEEE Access 11:26136–26151. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3257104

Rožman M, Tominc P, Štrukelj T (2023b) Competitiveness through development of strategic talent management and agile management ecosystems. Glob J Flex Syst Manage 24(3):373–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-023-00344-1

Şahin S, Alp F (2020) Agile leadership model in health care: Organizational and individual antecedents and outcomes. In: Akkaya B (ed) Agile business leadership methods for industry 4.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 47–68

Sampson CJ (2023) How agile leadership can sustain innovation in healthcare. Front Health Serv Manage 40(2):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/HAP.0000000000000186

Saputra N (2023) Digital quotient as mediator in the link of leadership agility to employee engagement of digital generation. In: 2023 8th International conference on business and industrial research (ICBIR), pp 706–710. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBIR57571.2023.10147472

Sharifi H, Zhang Z (1999) Methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organisations: an introduction. Int J Prod Econ 62(1):7–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00217-5

Sheffield R, Jensen KR, Kaudela-Baum S (2023) Inspiring and enabling innovation leadership: key findings and future directions. In: K. R. Jensen, S. Kaudela-Baum, R. Sheffield (eds) Innovation leadership in practice: how leaders turn ideas into value in a changing world. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83753-396-120231019

Silva-Martinez J (2023) Conceptualization of agile leadership characteristics and outcomes from NASA agile teams as a path to the development of an agile leadership theory. J Creat Value, 23949643231202894. https://doi.org/10.1177/23949643231202894

Spiegler SV, Heinecke C, Wagner S (2021) An empirical study on changing leadership in agile teams. Abstr Empirical Softw Eng 26(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-021-09949-5

Teece D, Peteraf M, Leih S (2016) Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. Calif Manage Rev 58(4):13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

The Center for Creative Leadership (2015) What you need, and don’t have, when it comes to leadership talent. Center for Creative Leadership

The World Bank (2022) As global growth slows, developing economies face risk of ‘Hard Landing’. The World Bank . The World Bank

Theobald S, Prenner N, Krieg A, Schneider K (2020) Agile leadership and agile management on organizational level—a systematic literature review. In: Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics), 12562 LNCS, pp 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64148-1_2

Turan HY, Cinnioğlu H (2022) Agile leadership and employee performance in VUCA world. In: Akkaya B, Guah MW, Jermsittiparsert K, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Kaya Y (eds) Agile management and VUCA-RR: opportunities and threats in industry 4.0 towards society 5.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 27–38

Ulrich D, Yeung A (2019) Agility: the new response to dynamic change. Strateg HR Rev 18(4):161–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-04-2019-0032

Vaszkun B, Sziráki É (2023) Unlocking the key dimensions of organizational agility: a systematic literature review on leadership, structural and cultural antecedents. Soc Econ 45(4):393–410. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2023.00023

Walter A-T (2021) Organizational agility: ill-defined and somewhat confusing? A systematic literature review and conceptualization. Manage Rev Q 71(2):343–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00186-6

Warner KSR, Wäger M (2019) Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: an ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan 52(3):326–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.12.001

Weiss L, Vergin L, Kanbach DK (2023) How agile leaders promote continuous innovation: an explorative framework. In: K. R. Jensen, S. Kaudela-Baum, R. Sheffield (eds) Innovation leadership in practice: How leaders turn ideas into value in a changing world. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83753-396-120231012

Zitkiene R, Deksnys M (2018) Organizational agility conceptual model. Monten J Econ 14(2):115–129. https://doi.org/10.14254/1800-5845/2018.14-2.7

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Research Ethics and Review Board (RERB) at O.P. Jindal Global University for their review and approval on our research study.

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India

Latika Tandon & Tithi Bhatnagar

National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bangalore, India

Tithi Bhatnagar

Jindal Global Business School, and Executive Director-Centre for Learning and Innovative Pedagogy (CLIP), O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India

Tanushree Sharma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by first author. The first draft of the manuscript was written by first author and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Latika Tandon .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See the Table 6 , 7 and 8 .

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tandon, L., Bhatnagar, T. & Sharma, T. Leadership agility in the context of organisational agility: a systematic literature review. Manag Rev Q (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00422-3

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2022

Accepted : 12 March 2024

Published : 17 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00422-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Leadership agility

- Agile leaders

- Agile leadership

- Organisational agility

- Leadership agility mindset

- Leadership agility competencies

- Leadership agility functions

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

- PMC10043496

Editorial: Leadership and management in organizations: Perspectives from SMEs and MNCs

Introduction.

Leadership and management are fundamental aspects for the smooth performance, progress, and growth of any organization with respect to its nature and the way it operates (Siyal et al., 2021a ). Every multinational, national, SME, and corporate sector needs effective management and leadership. This allows them to perform smoothly and produce significant output, which leads to growth and development. It is believed that the best leadership and management make remarkable contributions to the growth of institutions and yield remarkable outcomes (Siyal and Peng, 2018 ; Kouzes and Posner, 2023 ). This is due to the increasing recognition of and demand for effective leaders and managers by the corporate sectors, MNCs, and SMEs that are aiming to lead the global market. For this, they need qualified, trained, and committed leaders and managers who can efficiently and effectively lead the team, resources, and market. It is evident that several organizations acknowledge the need for effective leadership and efficient management, but they are still uncertain about the proper management, leadership style, and behaviors that are most effective for the growth and development of the corporate sector, MNCs, and SMEs, along with the development of their human resources (Kelly and Hearld, 2020 ; Siyal et al., 2021b ). Considering all these aspects and conflicting results from the past, the role of leadership and management in the smooth operationalization, growth, and development of the corporate sector, MNC, and SMEs remains unresolved.

This Research Topic focuses on leadership and management in organizations in diverse workplace settings including MNCs and SMEs. The call for papers was published between February 2022 and August 2022, during which the COVID-19 pandemic continued to impact some regions but not others. Scholars and practitioners were invited to submit research articles and brief reports pertaining to leadership and management in organizations, including corporations and SMEs, in the field of organizational psychology to the Frontiers in Psychology journal. In response to this call for papers, a huge number of academicians and practitioners submitted their research. Out of a total of 81 submissions, 18 were accepted and published under this theme. The Research Topic includes studies from diverse cultural and industrial settings, such as academia and industries including MNCs and SMEs, from across the globe. The businesses covered in this Research Topic are enterprises, manufacturers, SMEs, MNCs, educational institutes, logistics SMEs, and government sectors. The submitting authors were from different countries, including the Republic of Korea, China, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (Abu Dhabi), Oman, Qatar, Serbia, and Poland. The authors came up with new research approaches and methodologies, contributing to the theory and practice in this important emerging research domain of leadership and management.

Xu et al. investigated whether and how differential leadership in SMEs influences subordinate knowledge hiding. They analyzed the underlying mechanisms of chain-mediator–job insecurity and territorial consciousness and the boundary condition–leadership performance expectation. The results indicated that differential leadership plays a potential role in promoting subordinate knowledge hiding through the serial intervening mechanism of job insecurity and territorial consciousness in SMEs. This study contributes to the existing academic literature by empirically analyzing the under-investigated correlation between differential leadership and subordinate knowledge hiding in SMEs and by exploring the underlying mechanisms and boundary condition.

Ding et al. examined the link between an employee's professional identity and their success via the mediating role of critical thinking. They also examined the interaction of an employee's professional commitment and a leader's motivational language by critically analyzing employee success. This study was conducted on Chinese MNCs by use of a time-lagged study design. The results show a positive relation between an employee's professional identity and their success. Furthermore, the critical analysis mediated the link between professional identity and employee success.

Jun et al. examined the impact of supervisors' authentic leadership styles on the turnover of their subordinates in multiple organizations in the Republic of Korea. Their findings generalized the effects of leadership on turnover across different research contexts. Furthermore, they proposed a new mechanism and tested the mediation and moderation of the supervisor-perceived support and organizational identification, which reduces the turnover rate and help organizations to retain their best talents.

Leadership and management in organizations are crucial elements in ensuring the success of both MNCs and SMEs. While MNCs may have more resources and a more formal structure, SMEs often have a more flexible and agile approach to leadership and management. Both MNCs and SMEs can benefit from effective leadership and management practices such as clear communication, setting achievable goals, fostering a positive work culture, and continuously adapting to changing market conditions. Ultimately, the key to success in both types of organizations is having leaders and managers who are able to inspire and motivate their teams to achieve their goals.

In this regard, this Research Topic has introduced this novel research work by scholars and researchers from around the globe, with a focus on leadership and management perspectives and their role in organizations. Thus, the selected Research Topic is very important for the business, industry, management, academic, and economic value of practitioners and academic institutions at all levels, as well as those with country-wide and international offices. This Research Topic has contributed through novel approaches and provide suggestions for the managers and leaders of corporate sectors, MNCs and SMEs, academicians, academic institutions, social scientists, students, policymakers, government and non-government agencies, and other related stakeholders. Similarly, the findings in this Research Topic have suggested that investigating the impact of leadership and management in organizations could influence future research, and further studies could compare the effectiveness of leadership and management in MNCs and SMEs.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Kelly R. J., Hearld L. R. (2020). Burnout and leadership style in behavioral health care: A literature review . J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 47 , 581–600. 10.1007/s11414-019-09679-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kouzes J. M., Posner B. Z. (2023). The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations . New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Siyal S., Peng X. (2018). Does leadership lessen turnover? The moderated mediation effect of leader–member exchange and perspective taking on public servants . J. Public Affairs 18 , e1830. 10.1002/pa.1830 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Siyal S., Saeed M., Pahi M. H., Solangi R., Xin C. (2021a). They can't treat you well under abusive supervision: investigating the impact of job satisfaction and extrinsic motivation on healthcare employees . Ration. Soc . 33 , 401–423. 10.1177/10434631211033660 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Siyal S., Xin C., Umrani W. A., Fatima S., Pal D. (2021b). How do leaders influence innovation and creativity in employees? The mediating role of intrinsic motivation . Adm. Soc. 53 , 1337–1361. 10.1177/0095399721997427 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

2022 Impact Factor

- About Publication Information Subscriptions Permissions Advertising Journal Rankings Best Article Award Press Releases

- Resources Access Options Submission Guidelines Reviewer Guidelines Sample Articles Paper Calls Contact Us Submit & Review

- Browse Current Issue All Issues Featured Latest Topics Videos

California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

CMR INSIGHTS

Are we asking too much leadership from leaders.

by Herman Vantrappen and Frederic Wirtz

Image Credit | Nick Fewings

Leaders do not have an easy time. In the assumption that the headlines in the management literature are a reliable guide, leaders are expected not only to be brilliant but also servant, humble, transformational, vulnerable, authentic, emotionally intelligent, empathetic, unlocked and connecting – at the least. 1-9 That is a tall order, even for those who are labelled superhuman.

Related CMR Articles

“Transformational Leader or Narcissist? How Grandiose Narcissists Can Create and Destroy Organizations and Institutions” by Charles A. O’Reilly & Jennifer A. Chatman

Fortunately, leaders may not need to take all those exhortations too serious, or certainly not too literal. To begin with, some scholars warn of the shaky grounds of several leadership constructs. For example, Katja Einola et al. point to authentic leadership theory as an example of a “dysfunctional family of positive leadership theories celebrating good qualities in a leader linked with good outcomes and positive follower ‘effects’ almost by definition.” 10 They add that leadership studies should “raise the bar for what academic knowledge work is and better distinguish it from pseudoscience, pop-management, consulting, and entertainment.” Ouch!

Other scholars are adding precautions about the potentially detrimental effects of certain leader behaviors both for the leaders themselves and for the organizations they lead. For example, Joanna Lin et al. point to leader emotional exhaustion resulting from transformational leader behavior. 11 Charles O’Reilly et al. warn of the substantial overlaps of transformational leadership with grandiose narcissism. 12

Still other scholars emphasize that leadership skills are context-specific. For example, Raffaella Sadun emphasizes that the most effective leaders have social skills that are specific to their company and industry. 13 Nitin Nohria points out that charisma often is a liability, yet charismatic leaders can be especially useful at entrepreneurial startups and in corporate turnarounds. 14 Jasmin Hu et al. indicate that humble leaders are effective only when their level of humility matches to what team members expect. 15

The above tells us two things, whether we are a leader or a follower. First, the pertinence of a particular leader behavior depends on the situation. Second, we should temper our expectations of the effect of that behavior. But even then, the question remains: Are we demanding too much from leaders? The answer is nuanced: No, we cannot demand too much; but the real question is how we could lessen the need for those demands to emerge in the first place.

Reading the definitions of those leader behaviors, it would be hard to argue we are demanding too much. Just consider the following examples:

- Servant leaders “place the needs of their subordinates before their own needs and center their efforts on helping subordinates grow.” 1

- Humble leaders “are willing to admit it when they make a mistake, they recognize and acknowledge the skills of those they lead, and they continuously seek out opportunities to become better.” 16

- Vulnerable leaders “intentionally open themselves up to the potential of emotional harm while taking action (when possible) to create a positive outcome.” 4

- Emotionally intelligent leaders “are conscious about and responsive to their emotions, possessing the ability to harness and control them in order to deal with people effectively and make the best decisions.” 17

- Empathetic leaders “genuinely care for people, validate their feelings, and are willing to offer support.” 7

- Connecting leaders “concurrently contend with identities, actions, emotions of a leader and a follower.” 9

While these demands on leaders are pertinent, they are also taxing in terms of time and energy. To solve the quandary, we should look for ways to lessen the need for those demands to emerge in the first place. On many occasions, leaders at the top are led to activate the afore-mentioned behaviors because doubts, disagreements, tensions, trade-offs and eventually conflicts by and between people in the field are allowed to escalate. These frictions may emerge and escalate to the top for all kinds of reasons but they often land there due to organizational design faults: Some designs are intrinsically frictional; others lack mechanisms to resolve friction at origin. Precluding these design faults requires craftsmanship in organization design.

Let us take a stylized example. Laura is the commercial manager in charge of the Brazil region at Widget Inc. As sales this year are going more slowly than planned, she is desperately trying to win a specific new client. To have any chance of winning, she must be able to offer a special off-catalogue product. So she turns to Lucas, the global manager in charge of the product line concerned, who unfortunately has to tell her that the manufacturing plant is fully booked for the next six months, leaving no capacity for the mandatory testing of the special product for her client in Brazil. Tension rises, and the issue escalates to their respective bosses, the EVP Regions and the EVP Products. Unfortunately, these two do not manage to agree on a solution either. Even worse, the incident degenerates into an acrimonious confrontation at the company’s next executive team meeting, where the two blame each other for a chronic lack of flexibility.

The originally operational issue thus lands with a thick thud on the CEO’s desk. After suppressing a deep sigh, she activates various leader behaviors. She is empathetic (“I sense how strongly you both feel about this important matter …”), servant (“I don’t blame you for bringing this to my attention …”), humble (“I realize I should have put in place a way of preventing issues like this …”), vulnerable (“In fact, I once struggled myself with a similar issue …”), and more…

The CEO may be doing all the right things at that moment, but could she have been spared the onus of dealing with the originally operational friction if only the company’s organization had been designed differently? Widget Inc.’s organization architecture features two equally-weighted primary verticals, i.e., “region” and “product”, both having full P&L responsibility, hence competing with each other directly for resources, decision power and attention. While there is no general rule that such an architecture must not be chosen, in general it tends to be an intrinsically frictional design.

The general message for leaders is: When you seek remedies for pain points in your organization, do not count on leader behavior only, but check also for architectural design faults or ambiguities. Here are three examples, each linked to a variable that defines an organization’s architecture.

1. The primary vertical

Small mono-product and mono-market companies tend to have a function-based architecture (e.g., product development, purchasing, production, sales, distribution, after-sales). At large companies, that architecture can be intrinsically frictional. For example, if you are in the business of developing, constructing and maintaining power plants worldwide, the business development people, when they make a bid, might be tempted to foresee low maintenance costs so as to increase their chances of winning the bid. Alas, if the bid is won, the maintenance division will bear the brunt. Such operational tension is inherent to this type of business, but you do not want that tension to constantly manifest itself at the C-suite level. Therefore, consider having “region” rather than “function” as primary vertical and then setting up a function-based organization within each region. 18

2. The corporate parent

Each of a company’s business entities has specific objectives, challenges and priorities. Imagine your company has a mix of large businesses operating in its mature home market and small ventures in promising overseas markets. The latter may be keen to tap into the talent and knowledge that reside in the former, while the former may be reluctant to lend to the latter. Obviously, you do not want every such request and refusal to be elevated to the C-suite level. A global knowledge management and talent mobility system could solve the problem, and you might expect the businesses, out of enlightened self-interest, to set it up among themselves. Alas, that is unlikely to happen, as the benefits are contingent on participation by all businesses. Therefore, consider having a corporate function kick-start the initiative. 19

3. Lateral coordination

Imagine that your organization architecture consists of business entities focused on “product” and others on “customer segment”. Even though these entities by design are relatively self-contained, “product” and “customer segment” still need to coordinate daily on operational matters, such as defining product specs, setting price levels, launching commercial campaigns, etc. Hence you decide to create a matrix, with sales managers reporting both to a product line manager and a customer segment manager. And you expect these matrixed sales managers to make the best possible trade-offs between the partially diverging interests of their two bosses. Alas, a matrix between two verticals with P&L responsibility tends to be intrinsically frictional. 20 The matrixed manager’s anxiety about role conflict and their bosses’ fear of power loss may create festering conflicts escalating to the C-suite level. Therefore, in this case, consider a soft-wired coordination mechanism (such as a periodic joint planning cycle) instead of a hard-wired matrix.

There are many other examples of organization design faults or ambiguities, not only related to organizational architecture but also to governance, business processes, company culture, people and systems. Admittedly, the perfect organization design does not exist – tension and friction are a fact of corporate life. And we could hardly demand too much authenticity, emotional intelligence, empathy and other commendable behaviors from our leaders, as described at start. But there is an issue when senior leaders are compelled to activate these behaviors to resolve internal conflicts that should not have escalated to the top of the organization. By identifying and removing glaring design faults and ambiguities about roles, we can help lessen the emergence and escalation of such conflicts, and consequently reduce the opportunity cost of senior leaders devoting energy and time to resolving stoppable conflicts. Senior leaders had better focus on genuine people issues, external stakeholders, and the organization’s strategic choices.

References

R.C. Liden, S.J. Wayne, H. Zhao and D. Henderson, “Servant Leadership: Development of a Multidimensional Measure and Multi-Level Assessment,” The Leadership Quarterly 19, no. 2 (2008): 161-177..

E.H. Schein and P.A. Schein, “Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust,” 2nd ed. (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2018).

B.M. Bass, “Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1985).

J. Morgan, “Leading with Vulnerability: Unlock Your Greatest Superpower to Transform Yourself, Your Team, and Your Organization” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2023).

B. George, “Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value” (New York: Jossey-Bass, 2004).

D. Goleman, “The Emotionally Intelligent Leader” (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2019).

O. Valadon, “What We Get Wrong About Empathic Leadership,” Harvard Business Review, Oct. 17, 2023.

H. Le Gentil, “The Unlocked Leader: Dare to Free Your Own Voice, Lead with Empathy, and Shine Your Light in the World” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2023).

“The Connecting Leader: Serving Concurrently as a Leader and a Follower,” ed. Z. Jaser (Charlotte: IAP, 2021).

K. Einola and M. Alvesson, “The Perils of Authentic Leadership Theory,” Leadership 17, no. 4 (2021): 483-490.

J. Lin, B.A. Scott and F.K. Matta, “The Dark Side of Transformational Leader Behaviors for Leaders Themselves: A Conservation of Resources Perspective,” Academy of Management Journal 62, no. 5 (2019): 1556-1582.

C.A. O’Reilly and J.A. Chatman, “Transformational Leader or Narcissist? How Grandiose Narcissists Can Create and Destroy Organizations and Institutions,” California Management Review 62, no. 3 (2020): 5-27.

R. Sadun, “The Myth of the Brilliant, Charismatic Leader,” Harvard Business Review, Nov. 23, 2022.s

N. Nohria, “When Charismatic CEOs Are an Asset — and When They’re a Liability,” Harvard Business Review, Dec. 1, 2023.

J. Hu, B. Erdogan, K. Jiang and T.N. Bauer, “Research: When Being a Humble Leader Backfires,” Harvard Business Review, April 4, 2018.

T.K. Kelemen, S.H. Matthews, M.J. Matthews and S.E. Henry, “Essential Advice for Leaders from a Decade of Research on Humble Leadership,” LSE Business Review, Jan. 17, 2023.

S.T.A. Phipps, L.C. Prieto and E.N. Ndinguri, “Emotional Intelligence: Is It Necessary for Leader Development?” Journal of Leadership, Accountability & Ethics 11, no.1 (2014): 73-89.

H. Vantrappen and F. Wirtz, “When to Change Your Company’s P&L Responsibilities,” Harvard Business Review, April 14, 2022.

H. Vantrappen and F. Wirtz, “How To Get a Corporate Parent That Is Better For Business,” California Management Review, March 5, 2024.

J. Wolf and W.G. Egelhoff, “An Empirical Evaluation of Conflict in MNC Matrix Structure Firms,” International Business Review 22, no. 3 (2013): 591-601.

Recommended

Current issue.

Volume 66, Issue 2 Winter 2024

Recent CMR Articles

The Changing Ranks of Corporate Leaders

The Business Value of Gamification

Hope and Grit: How Human-Centered Product Design Enhanced Student Mental Health

Four Forms That Fit Most Organizations

Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Agility

Berkeley-Haas's Premier Management Journal

Published at Berkeley Haas for more than sixty years, California Management Review seeks to share knowledge that challenges convention and shows a better way of doing business.

- Open access

- Published: 19 April 2024

A scoping review of continuous quality improvement in healthcare system: conceptualization, models and tools, barriers and facilitators, and impact

- Aklilu Endalamaw 1 , 2 ,

- Resham B Khatri 1 , 3 ,

- Tesfaye Setegn Mengistu 1 , 2 ,

- Daniel Erku 1 , 4 , 5 ,

- Eskinder Wolka 6 ,

- Anteneh Zewdie 6 &

- Yibeltal Assefa 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 487 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

732 Accesses

Metrics details

The growing adoption of continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiatives in healthcare has generated a surge in research interest to gain a deeper understanding of CQI. However, comprehensive evidence regarding the diverse facets of CQI in healthcare has been limited. Our review sought to comprehensively grasp the conceptualization and principles of CQI, explore existing models and tools, analyze barriers and facilitators, and investigate its overall impacts.

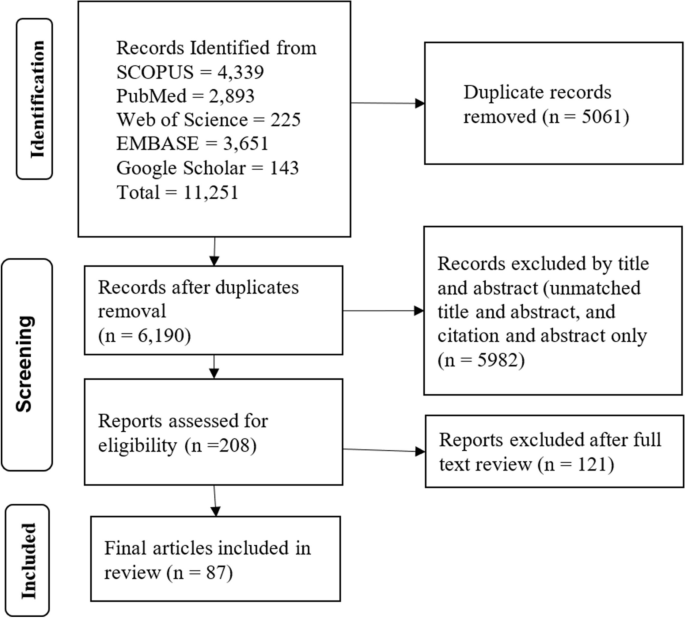

This qualitative scoping review was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework. We searched articles in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and EMBASE databases. In addition, we accessed articles from Google Scholar. We used mixed-method analysis, including qualitative content analysis and quantitative descriptive for quantitative findings to summarize findings and PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) framework to report the overall works.

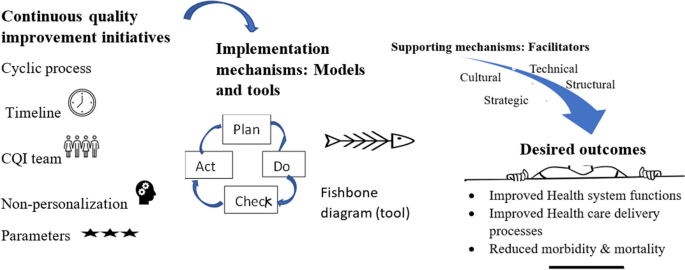

A total of 87 articles, which covered 14 CQI models, were included in the review. While 19 tools were used for CQI models and initiatives, Plan-Do-Study/Check-Act cycle was the commonly employed model to understand the CQI implementation process. The main reported purposes of using CQI, as its positive impact, are to improve the structure of the health system (e.g., leadership, health workforce, health technology use, supplies, and costs), enhance healthcare delivery processes and outputs (e.g., care coordination and linkages, satisfaction, accessibility, continuity of care, safety, and efficiency), and improve treatment outcome (reduce morbidity and mortality). The implementation of CQI is not without challenges. There are cultural (i.e., resistance/reluctance to quality-focused culture and fear of blame or punishment), technical, structural (related to organizational structure, processes, and systems), and strategic (inadequate planning and inappropriate goals) related barriers that were commonly reported during the implementation of CQI.

Conclusions

Implementing CQI initiatives necessitates thoroughly comprehending key principles such as teamwork and timeline. To effectively address challenges, it’s crucial to identify obstacles and implement optimal interventions proactively. Healthcare professionals and leaders need to be mentally equipped and cognizant of the significant role CQI initiatives play in achieving purposes for quality of care.

Peer Review reports

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiative is a crucial initiative aimed at enhancing quality in the health system that has gradually been adopted in the healthcare industry. In the early 20th century, Shewhart laid the foundation for quality improvement by describing three essential steps for process improvement: specification, production, and inspection [ 1 , 2 ]. Then, Deming expanded Shewhart’s three-step model into ‘plan, do, study/check, and act’ (PDSA or PDCA) cycle, which was applied to management practices in Japan in the 1950s [ 3 ] and was gradually translated into the health system. In 1991, Kuperman applied a CQI approach to healthcare, comprising selecting a process to be improved, assembling a team of expert clinicians that understands the process and the outcomes, determining key steps in the process and expected outcomes, collecting data that measure the key process steps and outcomes, and providing data feedback to the practitioners [ 4 ]. These philosophies have served as the baseline for the foundation of principles for continuous improvement [ 5 ].

Continuous quality improvement fosters a culture of continuous learning, innovation, and improvement. It encourages proactive identification and resolution of problems, promotes employee engagement and empowerment, encourages trust and respect, and aims for better quality of care [ 6 , 7 ]. These characteristics drive the interaction of CQI with other quality improvement projects, such as quality assurance and total quality management [ 8 ]. Quality assurance primarily focuses on identifying deviations or errors through inspections, audits, and formal reviews, often settling for what is considered ‘good enough’, rather than pursuing the highest possible standards [ 9 , 10 ], while total quality management is implemented as the management philosophy and system to improve all aspects of an organization continuously [ 11 ].

Continuous quality improvement has been implemented to provide quality care. However, providing effective healthcare is a complicated and complex task in achieving the desired health outcomes and the overall well-being of individuals and populations. It necessitates tackling issues, including access, patient safety, medical advances, care coordination, patient-centered care, and quality monitoring [ 12 , 13 ], rooted long ago. It is assumed that the history of quality improvement in healthcare started in 1854 when Florence Nightingale introduced quality improvement documentation [ 14 ]. Over the passing decades, Donabedian introduced structure, processes, and outcomes as quality of care components in 1966 [ 15 ]. More comprehensively, the Institute of Medicine in the United States of America (USA) has identified effectiveness, efficiency, equity, patient-centredness, safety, and timeliness as the components of quality of care [ 16 ]. Moreover, quality of care has recently been considered an integral part of universal health coverage (UHC) [ 17 ], which requires initiatives to mobilise essential inputs [ 18 ].

While the overall objective of CQI in health system is to enhance the quality of care, it is important to note that the purposes and principles of CQI can vary across different contexts [ 19 , 20 ]. This variation has sparked growing research interest. For instance, a review of CQI approaches for capacity building addressed its role in health workforce development [ 21 ]. Another systematic review, based on random-controlled design studies, assessed the effectiveness of CQI using training as an intervention and the PDSA model [ 22 ]. As a research gap, the former review was not directly related to the comprehensive elements of quality of care, while the latter focused solely on the impact of training using the PDSA model, among other potential models. Additionally, a review conducted in 2015 aimed to identify barriers and facilitators of CQI in Canadian contexts [ 23 ]. However, all these reviews presented different perspectives and investigated distinct outcomes. This suggests that there is still much to explore in terms of comprehensively understanding the various aspects of CQI initiatives in healthcare.

As a result, we conducted a scoping review to address several aspects of CQI. Scoping reviews serve as a valuable tool for systematically mapping the existing literature on a specific topic. They are instrumental when dealing with heterogeneous or complex bodies of research. Scoping reviews provide a comprehensive overview by summarizing and disseminating findings across multiple studies, even when evidence varies significantly [ 24 ]. In our specific scoping review, we included various types of literature, including systematic reviews, to enhance our understanding of CQI.

This scoping review examined how CQI is conceptualized and measured and investigated models and tools for its application while identifying implementation challenges and facilitators. It also analyzed the purposes and impact of CQI on the health systems, providing valuable insights for enhancing healthcare quality.

Protocol registration and results reporting

Protocol registration for this scoping review was not conducted. Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework was utilized to conduct this scoping review [ 25 ]. The scoping review procedures start by defining the research questions, identifying relevant literature, selecting articles, extracting data, and summarizing the results. The review findings are reported using the PRISMA extension for a scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) [ 26 ]. McGowan and colleagues also advised researchers to report findings from scoping reviews using PRISMA-ScR [ 27 ].

Defining the research problems

This review aims to comprehensively explore the conceptualization, models, tools, barriers, facilitators, and impacts of CQI within the healthcare system worldwide. Specifically, we address the following research questions: (1) How has CQI been defined across various contexts? (2) What are the diverse approaches to implementing CQI in healthcare settings? (3) Which tools are commonly employed for CQI implementation ? (4) What barriers hinder and facilitators support successful CQI initiatives? and (5) What effects CQI initiatives have on the overall care quality?

Information source and search strategy

We conducted the search in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and EMBASE databases, and the Google Scholar search engine. The search terms were selected based on three main distinct concepts. One group was CQI-related terms. The second group included terms related to the purpose for which CQI has been implemented, and the third group included processes and impact. These terms were selected based on the Donabedian framework of structure, process, and outcome [ 28 ]. Additionally, the detailed keywords were recruited from the primary health framework, which has described lists of dimensions under process, output, outcome, and health system goals of any intervention for health [ 29 ]. The detailed search strategy is presented in the Supplementary file 1 (Search strategy). The search for articles was initiated on August 12, 2023, and the last search was conducted on September 01, 2023.

Eligibility criteria and article selection

Based on the scoping review’s population, concept, and context frameworks [ 30 ], the population included any patients or clients. Additionally, the concepts explored in the review encompassed definitions, implementation, models, tools, barriers, facilitators, and impacts of CQI. Furthermore, the review considered contexts at any level of health systems. We included articles if they reported results of qualitative or quantitative empirical study, case studies, analytic or descriptive synthesis, any review, and other written documents, were published in peer-reviewed journals, and were designed to address at least one of the identified research questions or one of the identified implementation outcomes or their synonymous taxonomy as described in the search strategy. Based on additional contexts, we included articles published in English without geographic and time limitations. We excluded articles with abstracts only, conference abstracts, letters to editors, commentators, and corrections.

We exported all citations to EndNote x20 to remove duplicates and screen relevant articles. The article selection process includes automatic duplicate removal by using EndNote x20, unmatched title and abstract removal, citation and abstract-only materials removal, and full-text assessment. The article selection process was mainly conducted by the first author (AE) and reported to the team during the weekly meetings. The first author encountered papers that caused confusion regarding whether to include or exclude them and discussed them with the last author (YA). Then, decisions were ultimately made. Whenever disagreements happened, they were resolved by discussion and reconsideration of the review questions in relation to the written documents of the article. Further statistical analysis, such as calculating Kappa, was not performed to determine article inclusion or exclusion.

Data extraction and data items

We extracted first author, publication year, country, settings, health problem, the purpose of the study, study design, types of intervention if applicable, CQI approaches/steps if applicable, CQI tools and procedures if applicable, and main findings using a customized Microsoft Excel form.

Summarizing and reporting the results

The main findings were summarized and described based on the main themes, including concepts under conceptualizing, principles, teams, timelines, models, tools, barriers, facilitators, and impacts of CQI. Results-based convergent synthesis, achieved through mixed-method analysis, involved content analysis to identify the thematic presentation of findings. Additionally, a narrative description was used for quantitative findings, aligning them with the appropriate theme. The authors meticulously reviewed the primary findings from each included material and contextualized these findings concerning the main themes1. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of complex interventions and health systems, acknowledging quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Search results

A total of 11,251 documents were identified from various databases: SCOPUS ( n = 4,339), PubMed ( n = 2,893), Web of Science ( n = 225), EMBASE ( n = 3,651), and Google Scholar ( n = 143). After removing duplicates ( n = 5,061), 6,190 articles were evaluated by title and abstract. Subsequently, 208 articles were assessed for full-text eligibility. Following the eligibility criteria, 121 articles were excluded, leaving 87 included in the current review (Fig. 1 ).

Article selection process

Operationalizing continuous quality improvement

Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) is operationalized as a cyclic process that requires commitment to implementation, teamwork, time allocation, and celebrating successes and failures.

CQI is a cyclic ongoing process that is followed reflexive, analytical and iterative steps, including identifying gaps, generating data, developing and implementing action plans, evaluating performance, providing feedback to implementers and leaders, and proposing necessary adjustments [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ].

CQI requires committing to the philosophy, involving continuous improvement [ 19 , 38 ], establishing a mission statement [ 37 ], and understanding quality definition [ 19 ].

CQI involves a wide range of patient-oriented measures and performance indicators, specifically satisfying internal and external customers, developing quality assurance, adopting common quality measures, and selecting process measures [ 8 , 19 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 ].

CQI requires celebrating success and failure without personalization, leading each team member to develop error-free attitudes [ 19 ]. Success and failure are related to underlying organizational processes and systems as causes of failure rather than blaming individuals [ 8 ] because CQI is process-focused based on collaborative, data-driven, responsive, rigorous and problem-solving statistical analysis [ 8 , 19 , 38 ]. Furthermore, a gap or failure opens another opportunity for establishing a data-driven learning organization [ 41 ].

CQI cannot be implemented without a CQI team [ 8 , 19 , 37 , 39 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. A CQI team comprises individuals from various disciplines, often comprising a team leader, a subject matter expert (physician or other healthcare provider), a data analyst, a facilitator, frontline staff, and stakeholders [ 39 , 43 , 47 , 48 , 49 ]. It is also important to note that inviting stakeholders or partners as part of the CQI support intervention is crucial [ 19 , 38 , 48 ].

The timeline is another distinct feature of CQI because the results of CQI vary based on the implementation duration of each cycle [ 35 ]. There is no specific time limit for CQI implementation, although there is a general consensus that a cycle of CQI should be relatively short [ 35 ]. For instance, a CQI implementation took 2 months [ 42 ], 4 months [ 50 ], 9 months [ 51 , 52 ], 12 months [ 53 , 54 , 55 ], and one year and 5 months [ 49 ] duration to achieve the desired positive outcome, while bi-weekly [ 47 ] and monthly data reviews and analyses [ 44 , 48 , 56 ], and activities over 3 months [ 57 ] have also resulted in a positive outcome.

Continuous quality improvement models and tools