23.1 Overview of the Digestive System

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the organs of the alimentary canal from proximal to distal, and briefly state their function

- Identify the accessory digestive organs and briefly state their function

- Describe the four fundamental tissue layers of the alimentary canal

- Contrast the contributions of the enteric and autonomic nervous systems to digestive system functioning

- Explain how the peritoneum anchors the digestive organs

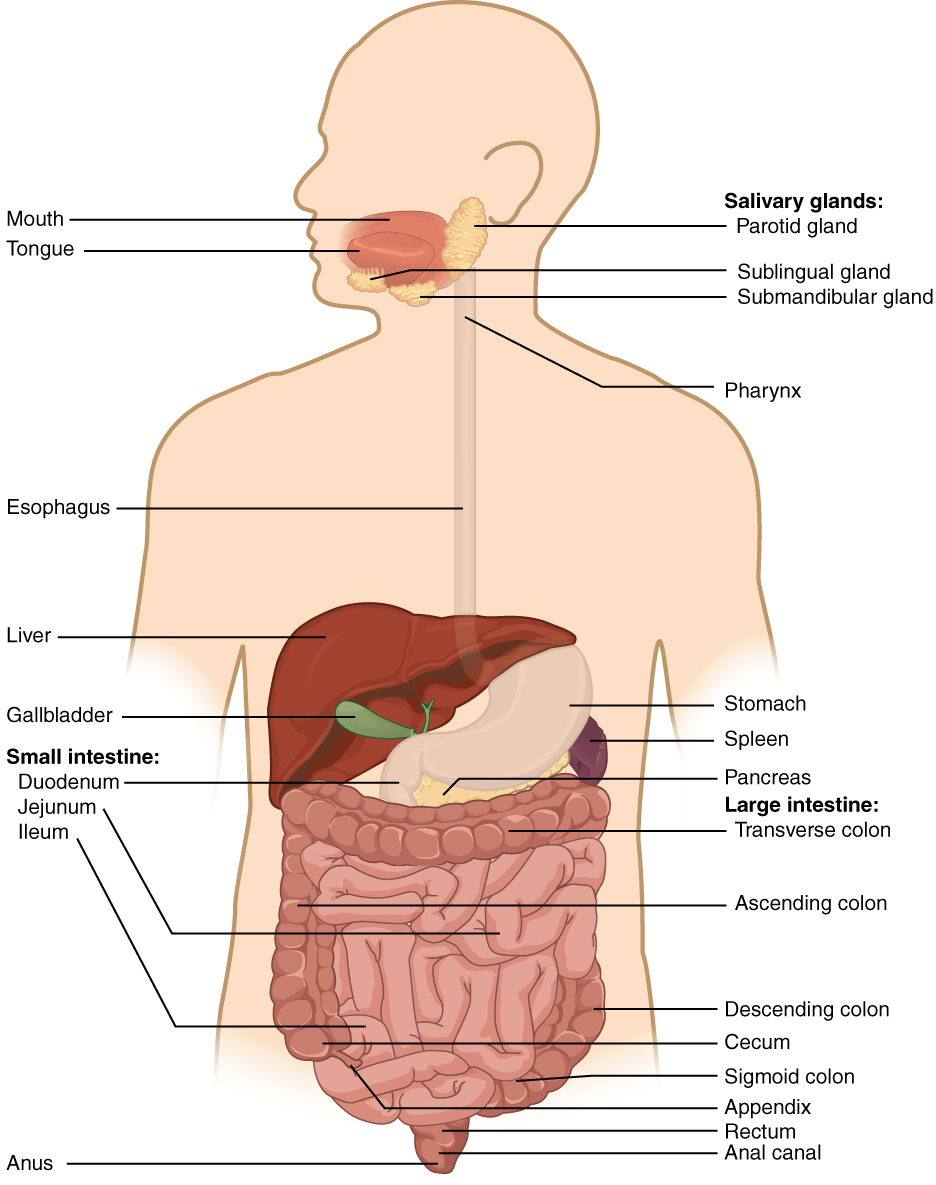

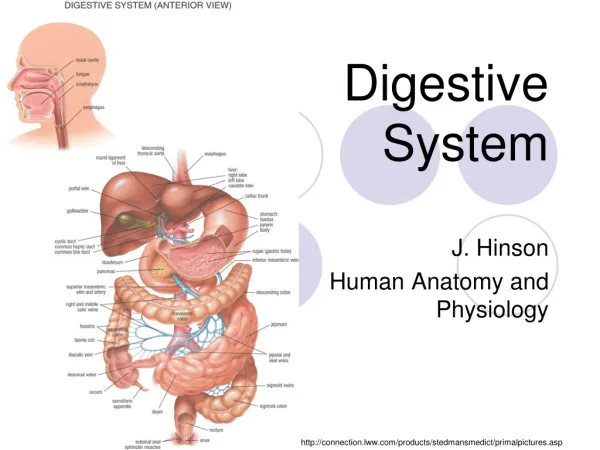

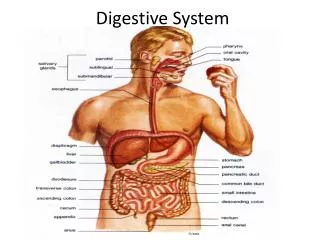

The function of the digestive system is to break down the foods you eat, release their nutrients, and absorb those nutrients into the body. Although the small intestine is the workhorse of the system, where the majority of digestion occurs, and where most of the released nutrients are absorbed into the blood or lymph, each of the digestive system organs makes a vital contribution to this process ( Figure 23.2 ).

As is the case with all body systems, the digestive system does not work in isolation; it functions cooperatively with the other systems of the body. Consider for example, the interrelationship between the digestive and cardiovascular systems. Arteries supply the digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients, and veins drain the digestive tract. These intestinal veins, constituting the hepatic portal system, are unique; they do not return blood directly to the heart. Rather, this blood is diverted to the liver where its nutrients are off-loaded for processing before blood completes its circuit back to the heart. At the same time, the digestive system provides nutrients to the heart muscle and vascular tissue to support their functioning. The interrelationship of the digestive and endocrine systems is also critical. Hormones secreted by several endocrine glands, as well as endocrine cells of the pancreas, the stomach, and the small intestine, contribute to the control of digestion and nutrient metabolism. In turn, the digestive system provides the nutrients to fuel endocrine function. Table 23.1 gives a quick glimpse at how these other systems contribute to the functioning of the digestive system.

Digestive System Organs

The easiest way to understand the digestive system is to divide its organs into two main categories. The first group is the organs that make up the alimentary canal. Accessory digestive organs comprise the second group and are critical for orchestrating the breakdown of food and the assimilation of its nutrients into the body. Accessory digestive organs, despite their name, are critical to the function of the digestive system.

Alimentary Canal Organs

Also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, the alimentary canal (aliment- = “to nourish”) is a one-way tube about 7.62 meters (25 feet) in length during life and closer to 10.67 meters (35 feet) in length when measured after death, once smooth muscle tone is lost. The main function of the organs of the alimentary canal is to nourish the body. This tube begins at the mouth and terminates at the anus. Between those two points, the canal is modified as the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines to fit the functional needs of the body. Both the mouth and anus are open to the external environment; thus, food and wastes within the alimentary canal are technically considered to be outside the body. Only through the process of absorption do the nutrients in food enter into and nourish the body’s “inner space.”

Accessory Structures

Each accessory digestive organ aids in the breakdown of food ( Figure 23.3 ). Within the mouth, the teeth and tongue begin mechanical digestion, whereas the salivary glands begin chemical digestion. Once food products enter the small intestine, the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas release secretions—such as bile and enzymes—essential for digestion to continue. Together, these are called accessory organs because they sprout from the lining cells of the developing gut (mucosa) and augment its function; indeed, you could not live without their vital contributions, and many significant diseases result from their malfunction. Even after development is complete, they maintain a connection to the gut by way of ducts.

Histology of the Alimentary Canal

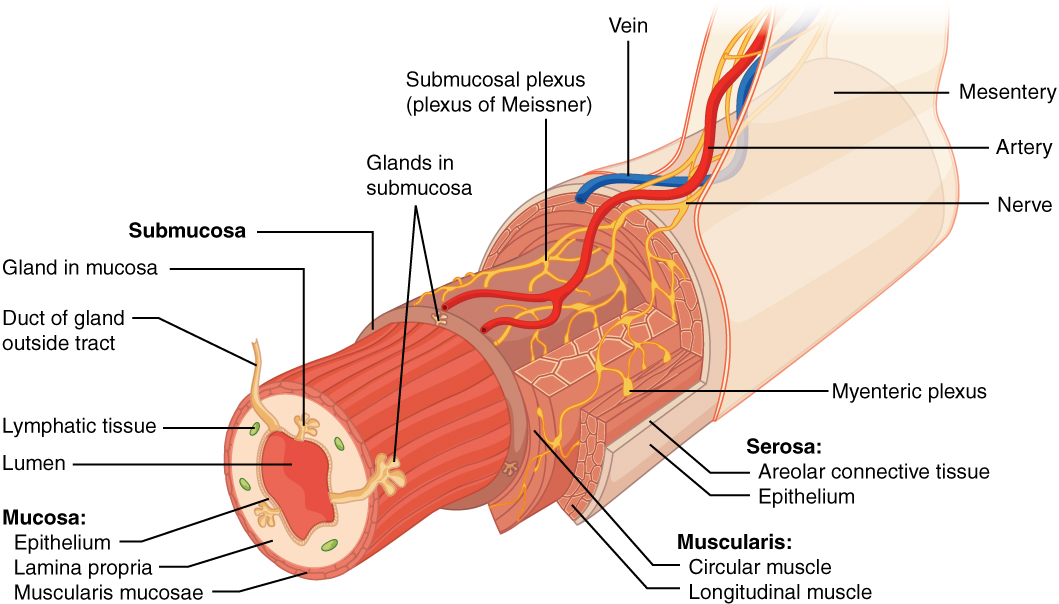

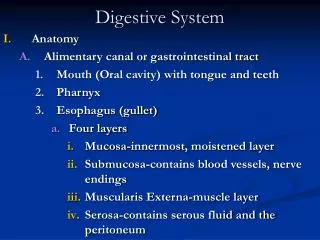

Throughout its length, the alimentary tract is composed of the same four tissue layers; the details of their structural arrangements vary to fit their specific functions. Starting from the lumen and moving outwards, these layers are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa, which is continuous with the mesentery (see Figure 23.3 ).

The mucosa is referred to as a mucous membrane, because mucus production is a characteristic feature of gut epithelium. The membrane consists of epithelium, which is in direct contact with ingested food, and the lamina propria, a layer of connective tissue analogous to the dermis. In addition, the mucosa has a thin, smooth muscle layer, called the muscularis mucosae (not to be confused with the muscularis layer, described below).

Epithelium —In the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and anal canal, the epithelium is primarily a non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium. In the stomach and intestines, it is a simple columnar epithelium. Notice that the epithelium is in direct contact with the lumen, the space inside the alimentary canal. Interspersed among its epithelial cells are goblet cells, which secrete mucus and fluid into the lumen, and enteroendocrine cells, which secrete hormones into the interstitial spaces between cells. Epithelial cells have a very brief lifespan, averaging from only a couple of days (in the mouth) to about a week (in the gut). This process of rapid renewal helps preserve the health of the alimentary canal, despite the wear and tear resulting from continued contact with foodstuffs.

Lamina propria —In addition to loose connective tissue, the lamina propria contains numerous blood and lymphatic vessels that transport nutrients absorbed through the alimentary canal to other parts of the body. The lamina propria also serves an immune function by housing clusters of lymphocytes, making up the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). These lymphocyte clusters are particularly substantial in the distal ileum where they are known as Peyer’s patches. When you consider that the alimentary canal is exposed to foodborne bacteria and other foreign matter, it is not hard to appreciate why the immune system has evolved a means of defending against the pathogens encountered within it.

Muscularis mucosae —This thin layer of smooth muscle is in a constant state of tension, pulling the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine into undulating folds. These folds dramatically increase the surface area available for digestion and absorption.

As its name implies, the submucosa lies immediately beneath the mucosa. A broad layer of dense connective tissue, it connects the overlying mucosa to the underlying muscularis. It includes blood and lymphatic vessels (which transport absorbed nutrients), and a scattering of submucosal glands that release digestive secretions. Additionally, it serves as a conduit for a dense branching network of nerves, the submucosal plexus, which functions as described below.

The third layer of the alimentary canal is the muscularis (also called the muscularis externa). The muscularis in the small intestine is made up of a double layer of smooth muscle: an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. The contractions of these layers promote mechanical digestion, expose more of the food to digestive chemicals, and move the food along the canal. In the most proximal and distal regions of the alimentary canal, including the mouth, pharynx, anterior part of the esophagus, and external anal sphincter, the muscularis is made up of skeletal muscle, which gives you voluntary control over swallowing and defecation. The basic two-layer structure found in the small intestine is modified in the organs proximal and distal to it. The stomach is equipped for its churning function by the addition of a third layer, the oblique muscle. While the colon has two layers like the small intestine, its longitudinal layer is segregated into three narrow parallel bands, the tenia coli, which make it look like a series of pouches rather than a simple tube.

The serosa is the portion of the alimentary canal superficial to the muscularis. Present only in the region of the alimentary canal within the abdominal cavity, it consists of a layer of visceral peritoneum overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. Instead of serosa, the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus have a dense sheath of collagen fibers called the adventitia. These tissues serve to hold the alimentary canal in place near the ventral surface of the vertebral column.

Nerve Supply

As soon as food enters the mouth, it is detected by receptors that send impulses along the sensory neurons of cranial nerves. Without these nerves, not only would your food be without taste, but you would also be unable to feel either the food or the structures of your mouth, and you would be unable to avoid biting yourself as you chew, an action enabled by the motor branches of cranial nerves.

Intrinsic innervation of much of the alimentary canal is provided by the enteric nervous system, which runs from the esophagus to the anus, and contains approximately 100 million motor, sensory, and interneurons (unique to this system compared to all other parts of the peripheral nervous system). These enteric neurons are grouped into two plexuses. The myenteric plexus (plexus of Auerbach) lies in the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal and is responsible for motility , especially the rhythm and force of the contractions of the muscularis. The submucosal plexus (plexus of Meissner) lies in the submucosal layer and is responsible for regulating digestive secretions and reacting to the presence of food (see Figure 23.3 ).

Extrinsic innervations of the alimentary canal are provided by the autonomic nervous system, which includes both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. In general, sympathetic activation (the fight-or-flight response) restricts the activity of enteric neurons, thereby decreasing GI secretion and motility. In contrast, parasympathetic activation (the rest-and-digest response) increases GI secretion and motility by stimulating neurons of the enteric nervous system.

Blood Supply

The blood vessels serving the digestive system have two functions. They transport the protein and carbohydrate nutrients absorbed by mucosal cells after food is digested in the lumen. Lipids are absorbed via lacteals, tiny structures of the lymphatic system. The blood vessels’ second function is to supply the organs of the alimentary canal with the nutrients and oxygen needed to drive their cellular processes.

Specifically, the more anterior parts of the alimentary canal are supplied with blood by arteries branching off the aortic arch and thoracic aorta. Below this point, the alimentary canal is supplied with blood by arteries branching from the abdominal aorta. The celiac trunk services the liver, stomach, and duodenum, whereas the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries supply blood to the remaining small and large intestines.

The veins that collect nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine (where most absorption occurs) empty into the hepatic portal system. This venous network takes the blood into the liver where the nutrients are either processed or stored for later use. Only then does the blood drained from the alimentary canal viscera circulate back to the heart. To appreciate just how demanding the digestive process is on the cardiovascular system, consider that while you are “resting and digesting,” about one-fourth of the blood pumped with each heartbeat enters arteries serving the intestines.

The Peritoneum

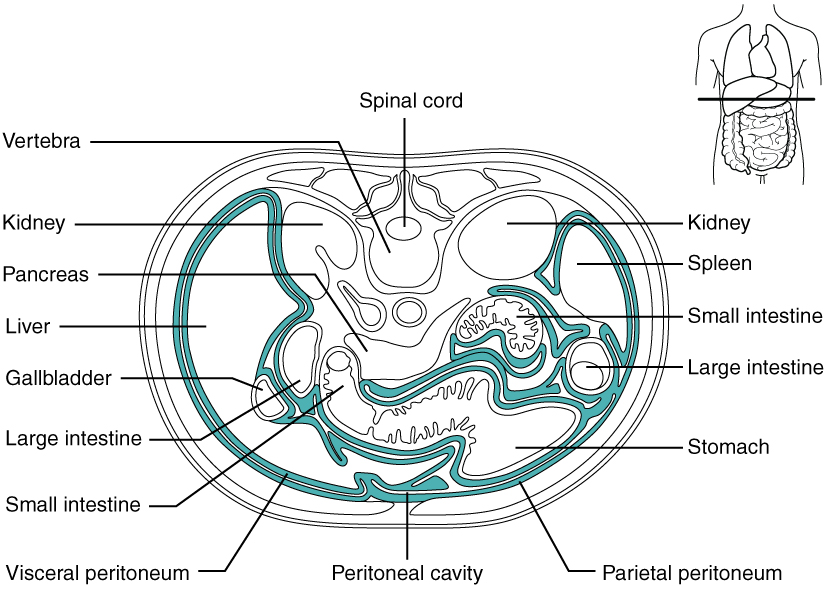

The digestive organs within the abdominal cavity are held in place by the peritoneum, a broad serous membranous sac made up of squamous epithelial tissue surrounded by connective tissue. It is composed of two different regions: the parietal peritoneum, which lines the abdominal wall, and the visceral peritoneum, which envelopes the abdominal organs ( Figure 23.4 ). The peritoneal cavity is the space bounded by the visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces. A few milliliters of watery fluid act as a lubricant to minimize friction between the serosal surfaces of the peritoneum.

Disorders of the...

Digestive system: peritonitis.

Inflammation of the peritoneum is called peritonitis. Chemical peritonitis can develop any time the wall of the alimentary canal is breached, allowing the contents of the lumen entry into the peritoneal cavity. For example, when an ulcer perforates the stomach wall, gastric juices spill into the peritoneal cavity. Hemorrhagic peritonitis occurs after a ruptured tubal pregnancy or traumatic injury to the liver or spleen fills the peritoneal cavity with blood. Even more severe peritonitis is associated with bacterial infections seen with appendicitis, colonic diverticulitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (infection of uterine tubes, usually by sexually transmitted bacteria). Peritonitis is life threatening and often results in emergency surgery to correct the underlying problem and intensive antibiotic therapy. When your great grandparents and even your parents were young, the mortality from peritonitis was high. Aggressive surgery, improvements in anesthesia safety, the advance of critical care expertise, and antibiotics have greatly improved the mortality rate from this condition. Even so, the mortality rate still ranges from 30 to 40 percent.

The visceral peritoneum includes multiple large folds that envelope various abdominal organs, holding them to the dorsal surface of the body wall. Within these folds are blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves that innervate the organs with which they are in contact, supplying their adjacent organs. The five major peritoneal folds are described in Table 23.2 . Note that during fetal development, certain digestive structures, including the first portion of the small intestine (called the duodenum), the pancreas, and portions of the large intestine (the ascending and descending colon, and the rectum) remain completely or partially posterior to the peritoneum. Thus, the location of these organs is described as retroperitoneal .

Interactive Link

By clicking on this link you can watch a short video of what happens to the food you eat, as it passes from your mouth to your intestine. Along the way, note how the food changes consistency and form. How does this change in consistency facilitate your gaining nutrients from food?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble, Peter DeSaix

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Anatomy and Physiology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 20, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Entire Site

- Research & Funding

- Health Information

- About NIDDK

- Digestive Diseases

- Your Digestive System & How it Works

- Español

Your Digestive System & How it Works

On this page:

What is the digestive system?

Why is digestion important, how does my digestive system work, how does food move through my gi tract, how does my digestive system break food into small parts my body can use, what happens to the digested food, how does my body control the digestive process, clinical trials.

The digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal tract—also called the GI tract or digestive tract—and the liver , pancreas , and gallbladder. The GI tract is a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus . The hollow organs that make up the GI tract are the mouth, esophagus , stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system.

The small intestine has three parts. The first part is called the duodenum. The jejunum is in the middle and the ileum is at the end. The large intestine includes the appendix , cecum, colon , and rectum. The appendix is a finger-shaped pouch attached to the cecum. The cecum is the first part of the large intestine. The colon is next. The rectum is the end of the large intestine.

Bacteria in your GI tract, also called gut flora or microbiome, help with digestion . Parts of your nervous and circulatory systems also help. Working together, nerves, hormones , bacteria, blood, and the organs of your digestive system digest the foods and liquids you eat or drink each day.

Digestion is important because your body needs nutrients from food and drink to work properly and stay healthy. Proteins , fats , carbohydrates , vitamins , minerals , and water are nutrients. Your digestive system breaks nutrients into parts small enough for your body to absorb and use for energy, growth, and cell repair.

- Proteins break into amino acids

- Fats break into fatty acids and glycerol

- Carbohydrates break into simple sugars

MyPlate offers ideas and tips to help you meet your individual health needs .

Each part of your digestive system helps to move food and liquid through your GI tract, break food and liquid into smaller parts, or both. Once foods are broken into small enough parts, your body can absorb and move the nutrients to where they are needed. Your large intestine absorbs water, and the waste products of digestion become stool . Nerves and hormones help control the digestive process.

The digestive process

Food moves through your GI tract by a process called peristalsis. The large, hollow organs of your GI tract contain a layer of muscle that enables their walls to move. The movement pushes food and liquid through your GI tract and mixes the contents within each organ. The muscle behind the food contracts and squeezes the food forward, while the muscle in front of the food relaxes to allow the food to move.

Mouth. Food starts to move through your GI tract when you eat. When you swallow, your tongue pushes the food into your throat. A small flap of tissue, called the epiglottis, folds over your windpipe to prevent choking and the food passes into your esophagus.

Esophagus. Once you begin swallowing, the process becomes automatic. Your brain signals the muscles of the esophagus and peristalsis begins.

Lower esophageal sphincter. When food reaches the end of your esophagus, a ringlike muscle—called the lower esophageal sphincter —relaxes and lets food pass into your stomach. This sphincter usually stays closed to keep what’s in your stomach from flowing back into your esophagus.

Stomach. After food enters your stomach, the stomach muscles mix the food and liquid with digestive juices . The stomach slowly empties its contents, called chyme , into your small intestine.

Small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with digestive juices from the pancreas, liver, and intestine, and push the mixture forward for further digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into your bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine.

Large intestine. Waste products from the digestive process include undigested parts of food, fluid, and older cells from the lining of your GI tract. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from liquid into stool. Peristalsis helps move the stool into your rectum.

Rectum. The lower end of your large intestine, the rectum, stores stool until it pushes stool out of your anus during a bowel movement .

Watch this video to see how food moves through your GI tract .

As food moves through your GI tract, your digestive organs break the food into smaller parts using:

- motion, such as chewing, squeezing, and mixing

- digestive juices, such as stomach acid, bile , and enzymes

Mouth. The digestive process starts in your mouth when you chew. Your salivary glands make saliva , a digestive juice, which moistens food so it moves more easily through your esophagus into your stomach. Saliva also has an enzyme that begins to break down starches in your food.

Esophagus. After you swallow, peristalsis pushes the food down your esophagus into your stomach.

Stomach. Glands in your stomach lining make stomach acid and enzymes that break down food. Muscles of your stomach mix the food with these digestive juices.

Pancreas. Your pancreas makes a digestive juice that has enzymes that break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The pancreas delivers the digestive juice to the small intestine through small tubes called ducts.

Liver. Your liver makes a digestive juice called bile that helps digest fats and some vitamins. Bile ducts carry bile from your liver to your gallbladder for storage, or to the small intestine for use.

Gallbladder. Your gallbladder stores bile between meals. When you eat, your gallbladder squeezes bile through the bile ducts into your small intestine.

Small intestine. Your small intestine makes digestive juice, which mixes with bile and pancreatic juice to complete the breakdown of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. Bacteria in your small intestine make some of the enzymes you need to digest carbohydrates. Your small intestine moves water from your bloodstream into your GI tract to help break down food. Your small intestine also absorbs water with other nutrients.

Large intestine. In your large intestine, more water moves from your GI tract into your bloodstream. Bacteria in your large intestine help break down remaining nutrients and make vitamin K . Waste products of digestion, including parts of food that are still too large, become stool.

The small intestine absorbs most of the nutrients in your food, and your circulatory system passes them on to other parts of your body to store or use. Special cells help absorbed nutrients cross the intestinal lining into your bloodstream. Your blood carries simple sugars, amino acids, glycerol, and some vitamins and salts to the liver. Your liver stores, processes, and delivers nutrients to the rest of your body when needed.

The lymph system , a network of vessels that carry white blood cells and a fluid called lymph throughout your body to fight infection, absorbs fatty acids and vitamins.

Your body uses sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, and glycerol to build substances you need for energy, growth, and cell repair.

Your hormones and nerves work together to help control the digestive process. Signals flow within your GI tract and back and forth from your GI tract to your brain.

Cells lining your stomach and small intestine make and release hormones that control how your digestive system works. These hormones tell your body when to make digestive juices and send signals to your brain that you are hungry or full. Your pancreas also makes hormones that are important to digestion.

You have nerves that connect your central nervous system—your brain and spinal cord—to your digestive system and control some digestive functions. For example, when you see or smell food, your brain sends a signal that causes your salivary glands to "make your mouth water" to prepare you to eat.

You also have an enteric nervous system (ENS)—nerves within the walls of your GI tract. When food stretches the walls of your GI tract, the nerves of your ENS release many different substances that speed up or delay the movement of food and the production of digestive juices. The nerves send signals to control the actions of your gut muscles to contract and relax to push food through your intestines.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov .

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

154 23.1 Overview of the Digestive System

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the organs of the alimentary canal from proximal to distal, and briefly state their function

- Identify the accessory digestive organs and briefly state their function

- Describe the four fundamental tissue layers of the alimentary canal

- Contrast the contributions of the enteric and autonomic nervous systems to digestive system functioning

- Explain how the peritoneum anchors the digestive organs

The function of the digestive system is to break down the foods you eat, release their nutrients, and absorb those nutrients into the body. Although the small intestine is the workhorse of the system, where the majority of digestion occurs, and where most of the released nutrients are absorbed into the blood or lymph, each of the digestive system organs makes a vital contribution to this process ( Figure 1 ).

As is the case with all body systems, the digestive system does not work in isolation; it functions cooperatively with the other systems of the body. Consider for example, the interrelationship between the digestive and cardiovascular systems. Arteries supply the digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients, and veins drain the digestive tract. These intestinal veins, constituting the hepatic portal system, are unique; they do not return blood directly to the heart. Rather, this blood is diverted to the liver where its nutrients are off-loaded for processing before blood completes its circuit back to the heart. At the same time, the digestive system provides nutrients to the heart muscle and vascular tissue to support their functioning. The interrelationship of the digestive and endocrine systems is also critical. Hormones secreted by several endocrine glands, as well as endocrine cells of the pancreas, the stomach, and the small intestine, contribute to the control of digestion and nutrient metabolism. In turn, the digestive system provides the nutrients to fuel endocrine function. Table 1 gives a quick glimpse at how these other systems contribute to the functioning of the digestive system.

Digestive System Organs

The easiest way to understand the digestive system is to divide its organs into two main categories. The first group is the organs that make up the alimentary canal. Accessory digestive organs comprise the second group and are critical for orchestrating the breakdown of food and the assimilation of its nutrients into the body. Accessory digestive organs, despite their name, are critical to the function of the digestive system.

Alimentary Canal Organs

Also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, the alimentary canal (aliment- = “to nourish”) is a one-way tube about 7.62 meters (25 feet) in length during life and closer to 10.67 meters (35 feet) in length when measured after death, once smooth muscle tone is lost. The main function of the organs of the alimentary canal is to nourish the body. This tube begins at the mouth and terminates at the anus. Between those two points, the canal is modified as the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines to fit the functional needs of the body. Both the mouth and anus are open to the external environment; thus, food and wastes within the alimentary canal are technically considered to be outside the body. Only through the process of absorption do the nutrients in food enter into and nourish the body’s “inner space.”

Accessory Structures

Each accessory digestive organ aids in the breakdown of food ( Figure 2 ). Within the mouth, the teeth and tongue begin mechanical digestion, whereas the salivary glands begin chemical digestion. Once food products enter the small intestine, the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas release secretions—such as bile and enzymes—essential for digestion to continue. Together, these are called accessory organs because they sprout from the lining cells of the developing gut (mucosa) and augment its function; indeed, you could not live without their vital contributions, and many significant diseases result from their malfunction. Even after development is complete, they maintain a connection to the gut by way of ducts.

Histology of the Alimentary Canal

Throughout its length, the alimentary tract is composed of the same four tissue layers; the details of their structural arrangements vary to fit their specific functions. Starting from the lumen and moving outwards, these layers are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa, which is continuous with the mesentery (see Figure 2 ).

The mucosa is referred to as a mucous membrane, because mucus production is a characteristic feature of gut epithelium. The membrane consists of epithelium, which is in direct contact with ingested food, and the lamina propria, a layer of connective tissue analogous to the dermis. In addition, the mucosa has a thin, smooth muscle layer, called the muscularis mucosa (not to be confused with the muscularis layer, described below).

Epithelium —In the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and anal canal, the epithelium is primarily a non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium. In the stomach and intestines, it is a simple columnar epithelium. Notice that the epithelium is in direct contact with the lumen, the space inside the alimentary canal. Interspersed among its epithelial cells are goblet cells, which secrete mucus and fluid into the lumen, and enteroendocrine cells, which secrete hormones into the interstitial spaces between cells. Epithelial cells have a very brief lifespan, averaging from only a couple of days (in the mouth) to about a week (in the gut). This process of rapid renewal helps preserve the health of the alimentary canal, despite the wear and tear resulting from continued contact with foodstuffs.

Lamina propria —In addition to loose connective tissue, the lamina propria contains numerous blood and lymphatic vessels that transport nutrients absorbed through the alimentary canal to other parts of the body. The lamina propria also serves an immune function by housing clusters of lymphocytes, making up the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). These lymphocyte clusters are particularly substantial in the distal ileum where they are known as Peyer’s patches. When you consider that the alimentary canal is exposed to foodborne bacteria and other foreign matter, it is not hard to appreciate why the immune system has evolved a means of defending against the pathogens encountered within it.

Muscularis mucosa —This thin layer of smooth muscle is in a constant state of tension, pulling the mucosa of the stomach and small intestine into undulating folds. These folds dramatically increase the surface area available for digestion and absorption.

As its name implies, the submucosa lies immediately beneath the mucosa. A broad layer of dense connective tissue, it connects the overlying mucosa to the underlying muscularis. It includes blood and lymphatic vessels (which transport absorbed nutrients), and a scattering of submucosal glands that release digestive secretions. Additionally, it serves as a conduit for a dense branching network of nerves, the submucosal plexus, which functions as described below.

The third layer of the alimentary canal is the muscalaris (also called the muscularis externa). The muscularis in the small intestine is made up of a double layer of smooth muscle: an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. The contractions of these layers promote mechanical digestion, expose more of the food to digestive chemicals, and move the food along the canal. In the most proximal and distal regions of the alimentary canal, including the mouth, pharynx, anterior part of the esophagus, and external anal sphincter, the muscularis is made up of skeletal muscle, which gives you voluntary control over swallowing and defecation. The basic two-layer structure found in the small intestine is modified in the organs proximal and distal to it. The stomach is equipped for its churning function by the addition of a third layer, the oblique muscle. While the colon has two layers like the small intestine, its longitudinal layer is segregated into three narrow parallel bands, the tenia coli, which make it look like a series of pouches rather than a simple tube.

The serosa is the portion of the alimentary canal superficial to the muscularis. Present only in the region of the alimentary canal within the abdominal cavity, it consists of a layer of visceral peritoneum overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. Instead of serosa, the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus have a dense sheath of collagen fibers called the adventitia. These tissues serve to hold the alimentary canal in place near the ventral surface of the vertebral column.

Nerve Supply

As soon as food enters the mouth, it is detected by receptors that send impulses along the sensory neurons of cranial nerves. Without these nerves, not only would your food be without taste, but you would also be unable to feel either the food or the structures of your mouth, and you would be unable to avoid biting yourself as you chew, an action enabled by the motor branches of cranial nerves.

Intrinsic innervation of much of the alimentary canal is provided by the enteric nervous system, which runs from the esophagus to the anus, and contains approximately 100 million motor, sensory, and interneurons (unique to this system compared to all other parts of the peripheral nervous system). These enteric neurons are grouped into two plexuses. The myenteric plexus (plexus of Auerbach) lies in the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal and is responsible for motility , especially the rhythm and force of the contractions of the muscularis. The submucosal plexus (plexus of Meissner) lies in the submucosal layer and is responsible for regulating digestive secretions and reacting to the presence of food (see [link] ).

Extrinsic innervations of the alimentary canal are provided by the autonomic nervous system, which includes both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. In general, sympathetic activation (the fight-or-flight response) restricts the activity of enteric neurons, thereby decreasing GI secretion and motility. In contrast, parasympathetic activation (the rest-and-digest response) increases GI secretion and motility by stimulating neurons of the enteric nervous system.

Blood Supply

The blood vessels serving the digestive system have two functions. They transport the protein and carbohydrate nutrients absorbed by mucosal cells after food is digested in the lumen. Lipids are absorbed via lacteals, tiny structures of the lymphatic system. The blood vessels’ second function is to supply the organs of the alimentary canal with the nutrients and oxygen needed to drive their cellular processes.

Specifically, the more anterior parts of the alimentary canal are supplied with blood by arteries branching off the aortic arch and thoracic aorta. Below this point, the alimentary canal is supplied with blood by arteries branching from the abdominal aorta. The celiac trunk services the liver, stomach, and duodenum, whereas the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries supply blood to the remaining small and large intestines.

The veins that collect nutrient-rich blood from the small intestine (where most absorption occurs) empty into the hepatic portal system. This venous network takes the blood into the liver where the nutrients are either processed or stored for later use. Only then does the blood drained from the alimentary canal viscera circulate back to the heart. To appreciate just how demanding the digestive process is on the cardiovascular system, consider that while you are “resting and digesting,” about one-fourth of the blood pumped with each heartbeat enters arteries serving the intestines.

The Peritoneum

The digestive organs within the abdominal cavity are held in place by the peritoneum, a broad serous membranous sac made up of squamous epithelial tissue surrounded by connective tissue. It is composed of two different regions: the parietal peritoneum, which lines the abdominal wall, and the visceral peritoneum, which envelopes the abdominal organs ( Figure 3 ). The peritoneal cavity is the space bounded by the visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces. A few milliliters of watery fluid act as a lubricant to minimize friction between the serosal surfaces of the peritoneum.

Digestive System: Peritonitis

Inflammation of the peritoneum is called peritonitis. Chemical peritonitis can develop any time the wall of the alimentary canal is breached, allowing the contents of the lumen entry into the peritoneal cavity. For example, when an ulcer perforates the stomach wall, gastric juices spill into the peritoneal cavity. Hemorrhagic peritonitis occurs after a ruptured tubal pregnancy or traumatic injury to the liver or spleen fills the peritoneal cavity with blood. Even more severe peritonitis is associated with bacterial infections seen with appendicitis, colonic diverticulitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (infection of uterine tubes, usually by sexually transmitted bacteria). Peritonitis is life threatening and often results in emergency surgery to correct the underlying problem and intensive antibiotic therapy. When your great grandparents and even your parents were young, the mortality from peritonitis was high. Aggressive surgery, improvements in anesthesia safety, the advance of critical care expertise, and antibiotics have greatly improved the mortality rate from this condition. Even so, the mortality rate still ranges from 30 to 40 percent.

The visceral peritoneum includes multiple large folds that envelope various abdominal organs, holding them to the dorsal surface of the body wall. Within these folds are blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves that innervate the organs with which they are in contact, supplying their adjacent organs. The five major peritoneal folds are described in Table 2 . Note that during fetal development, certain digestive structures, including the first portion of the small intestine (called the duodenum), the pancreas, and portions of the large intestine (the ascending and descending colon, and the rectum) remain completely or partially posterior to the peritoneum. Thus, the location of these organs is described as retroperitoneal .

By clicking on this link you can watch a short video of what happens to the food you eat, as it passes from your mouth to your intestine. Along the way, note how the food changes consistency and form. How does this change in consistency facilitate your gaining nutrients from food?

Chapter Review

The digestive system includes the organs of the alimentary canal and accessory structures. The alimentary canal forms a continuous tube that is open to the outside environment at both ends. The organs of the alimentary canal are the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The accessory digestive structures include the teeth, tongue, salivary glands, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. The wall of the alimentary canal is composed of four basic tissue layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. The enteric nervous system provides intrinsic innervation, and the autonomic nervous system provides extrinsic innervation.

Interactive Link Questions

By clicking on this link , you can watch a short video of what happens to the food you eat as it passes from your mouth to your intestine. Along the way, note how the food changes consistency and form. How does this change in consistency facilitate your gaining nutrients from food?

Answers may vary.

Review Questions

1. Which of these organs is not considered an accessory digestive structure?

- salivary glands

2. Which of the following organs is supported by a layer of adventitia rather than serosa?

- small intestine

- large intestine

3. Which of the following membranes covers the stomach?

- falciform ligament

- parietal peritoneum

- visceral peritoneum

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Explain how the enteric nervous system supports the digestive system. What might occur that could result in the autonomic nervous system having a negative impact on digestion?

2. What layer of the alimentary canal tissue is capable of helping to protect the body against disease, and through what mechanism?

Answers for Review Questions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- The enteric nervous system helps regulate alimentary canal motility and the secretion of digestive juices, thus facilitating digestion. If a person becomes overly anxious, sympathetic innervation of the alimentary canal is stimulated, which can result in a slowing of digestive activity.

- The lamina propria of the mucosa contains lymphoid tissue that makes up the MALT and responds to pathogens encountered in the alimentary canal.

Anatomy and Physiology Copyright © 1999-2016 by Rice University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

21.3: Digestive System Processes and Regulation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 22410

- Whitney Menefee, Julie Jenks, Chiara Mazzasette, & Kim-Leiloni Nguyen

- Reedley College, Butte College, Pasadena City College, & Mt. San Antonio College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

By the end of the section, you will be able to:

- Discuss seven fundamental activities of the digestive system, giving an example of each

- Describes the functions of each digestive organs

- Describe the difference between mechanical digestion and chemical digestion

- Describe the difference between peristalsis and segmentation

The digestive system uses mechanical and chemical activities to break food down into absorbable substances during its journey through the digestive system. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) provides an overview of the basic functions of the digestive organs.

Digestive Processes

The processes of digestion include seven activities: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical or physical digestion, chemical digestion, secretion, absorption, and defecation.

The first of these processes, ingestion , refers to the entry of food into the alimentary canal through the mouth. There, the food is chewed and mixed with saliva secreted by salivary glands, which contains enzymes that begin breaking down the carbohydrates in the food plus some lipid digestion via lingual lipase. Chewing increases the surface area of the food and allows an appropriately sized bolus (chunk) to be produced.

Food leaves the mouth when the tongue and pharyngeal muscles propel it into the esophagus. This act of swallowing, the last voluntary act until defecation, is an example of propulsion , which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis. Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of of circular and longitudinal layers of the muscularis externa (alimentary wall smooth muscles), which act to propel food along (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). These waves also play a role in mixing food with digestive juices. Peristalsis is so powerful that foods and liquids you swallow enter your stomach even if you are standing on your head.

Digestion includes both mechanical and chemical processes. Mechanical digestion is a purely physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food. Instead, it makes the food smaller to increase both surface area and mobility. It includes mastication , or chewing, as well as tongue movements that help break food into smaller bits and mix food with saliva. Although there may be a tendency to think that mechanical digestion is limited to the first steps of the digestive process, it occurs after the food leaves the mouth, as well. The mechanical churning of food in the stomach serves to further break it apart and expose more of its surface area to digestive juices, creating an acidic “soup” called chyme . Segmentation , which occurs mainly in the small intestine, consists of localized contractions of circular muscle of the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal. These contractions isolate small sections of the intestine, moving their contents back and forth while continuously subdividing, breaking up, and mixing the contents. By moving food back and forth in the intestinal lumen, segmentation mixes food with digestive juices and facilitates absorption.

Chemical digestion is aided by secretion of enzymes. Starting in the mouth, digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks (for example, proteins into separate amino acids). These secretions vary in composition, but typically contain water, various enzymes, acids, and salts. The process is completed in the small intestine.

Food that has been broken down is of no value to the body unless it enters the bloodstream and its nutrients are put to work. This occurs through the process of absorption , which takes place primarily within the small intestine. There, most nutrients are absorbed from the lumen of the alimentary canal into the bloodstream through the epithelial cells that make up the mucosa. Lipids are absorbed into lacteals and are transported via the lymphatic vessels to the bloodstream (the subclavian veins near the heart). The details of these processes will be discussed later.

In defecation , the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces.

AGING AND THE...

Digestive System: From Appetite Suppression to Constipation

Age-related changes in the digestive system begin in the mouth and can affect virtually every aspect of the digestive system. Taste buds become less sensitive, so food isn’t as appetizing as it once was. A slice of pizza is a challenge, not a treat, when you have lost teeth, your gums are diseased, and your salivary glands aren’t producing enough saliva. Swallowing can be difficult, and ingested food moves slowly through the alimentary canal because of reduced strength and tone of muscular tissue. Neurosensory feedback is also dampened, slowing the transmission of messages that stimulate the release of enzymes and hormones.

Pathologies that affect the digestive organs—such as hiatal hernia, gastritis, and peptic ulcer disease—can occur at greater frequencies as you age. Problems in the small intestine may include duodenal ulcers, maldigestion, and malabsorption. Problems in the large intestine include hemorrhoids, diverticular disease, and constipation. Conditions that affect the function of accessory organs—and their abilities to deliver pancreatic enzymes and bile to the small intestine—include jaundice, acute pancreatitis, cirrhosis, and gallstones.

In some cases, a single organ is in charge of a digestive process. For example, ingestion occurs only in the mouth and defecation from the anus. However, most digestive processes involve the interaction of several organs and occur gradually as food moves through the alimentary canal (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Figure 21.3.2 shows the digestive tract with the locations of propulsion, chemical digestion, mechanical digestion, and absorption in different organs.

While most chemical digestion occurs in the small intestine, some occurs in the mouth (carbohydrates and lipids) and stomach (proteins). Absorption, also largely carried out by the small intestine, some can occur in the mouth, stomach, and large intestine. For example, alcohol and aspirin are absorbed by the stomach and water and many ions are absorbed by the large intestine.

Regulatory Mechanisms

Neural and endocrine regulatory mechanisms work to maintain the optimal conditions in the lumen needed for digestion and absorption. These regulatory mechanisms, which stimulate digestive activity through mechanical and chemical activity, are controlled both extrinsically and intrinsically.

Neural Controls

The walls of the alimentary canal contain a variety of sensors that help regulate digestive functions. These include mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and osmoreceptors, which are capable of detecting mechanical, chemical, and osmotic stimuli, respectively. For example, these receptors can sense when the presence of food has caused the stomach to expand, whether food particles have been sufficiently broken down, how much liquid is present, and the type of nutrients in the food (lipids, carbohydrates, and/or proteins). Stimulation of these receptors provokes an appropriate reflex that furthers the process of digestion. This may entail sending a message that activates the glands that secrete digestive juices into the lumen, or it may mean the stimulation of muscles within the alimentary canal, thereby activating peristalsis and segmentation that move food along the intestinal tract.

The walls of the entire alimentary canal are embedded with nerve plexuses (enteric nervous system, submucosal and myenteric plexuses) that interact with the central nervous system and other nerve plexuses—either within the same digestive organ or in different ones. These interactions prompt several types of reflexes. Extrinsic nerve plexuses orchestrate long reflexes, which involve the central and autonomic nervous systems and work in response to stimuli from outside the digestive system. Short reflexes, on the other hand, are orchestrated by intrinsic nerve plexuses within the alimentary canal wall. These two plexuses and their connections were introduced earlier as the enteric nervous system. Short reflexes regulate activities in one area of the digestive tract and may coordinate local peristaltic movements and stimulate digestive secretions. For example, the sight, smell, and taste of food initiate long reflexes that begin with a sensory neuron delivering a signal to the medulla oblongata. The response to the signal is to stimulate cells in the stomach to begin secreting digestive juices in preparation for incoming food. In contrast, food that distends the stomach initiates short reflexes that cause cells in the stomach wall to increase their secretion of digestive juices.

Hormonal Controls

A variety of hormones are involved in the digestive process. The main digestive hormone of the stomach is gastrin, which is secreted in response to the presence of food. Gastrin stimulates the secretion of gastric acid by the parietal cells of the stomach mucosa. Other GI hormones are produced and act upon the gut and its accessory organs. Hormones produced by the duodenum include secretin, which stimulates a watery secretion of bicarbonate by the pancreas; cholecystokinin (CCK), which stimulates the secretion of pancreatic enzymes and bile from the liver and release of bile from the gallbladder; and gastric inhibitory peptide, which inhibits gastric secretion and slows gastric emptying and motility. These GI hormones are secreted by specialized epithelial cells, called enteroendocrine cells, located in the mucosal epithelium of the stomach and small intestine. These hormones then enter the bloodstream, through which they can reach their target organs.

Concept Review

The digestive system ingests and digests food, absorbs released nutrients, and excretes food components that are indigestible. The six activities involved in this process are ingestion (mouth), motility (GI tract), mechanical digestion (mouth, stomach, small intestine), chemical digestion (mouth, stomach, small intestine), absorption (mouth, stomach, small and large intestines), and defecation (anus). Contractions of smooth muscles (muscularis externa) result in peristalsis to push contents along in the GI tract and segmentation to mix the content with enzymes. These processes are regulated by neural and hormonal mechanisms.

Review Questions

Q. Which of these processes occurs in the mouth?

A. ingestion

B. mechanical digestion

C. chemical digestion

D. all of the above

Q. Which of these processes occurs throughout most of the alimentary canal?

B. propulsion

C. segmentation

D. absorption

Q. Which of the following occur(s) in the mouth?

A. mechanical digestion

B. chemical digestion

C. mastication

Q. Which of these statements about the colon is false?

A. Chemical digestion occurs in the colon.

B. Absorption occurs in the colon.

C. Peristalsis occurs in the colon.

D. Diverticular disease occurs in the colon.

Critical Thinking Questions

Q. Offer a theory to explain why segmentation occurs and peristalsis slows in the small intestine.

A. The majority of digestion and absorption occurs in the small intestine. By slowing the transit of chyme, segmentation and a reduced rate of peristalsis allow time for these processes to occur.

Q. Which organ is mostly responsible for diarrhea and constipation and why?

A. The colon absorbs water. If it absorbs too much water, then the remaining contents (stool) may be hard and constipation may result. If it absorbs very little water or even secretes water, then the remaining contents will be loose and watery, resulting in diarrhea.

Contributors and Attributions

OpenStax Anatomy & Physiology (CC BY 4.0). Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

46 templates

suicide prevention

8 templates

49 templates

18 templates

41 templates

29 templates

Science Subject for High School - 9th Grade Human Body. Digestive System

Science subject for high school - 9th grade human body. digestive system presentation, free google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

From the mouth through the esophagus into the stomach and passing through the small and large intestine and secreted by the anus. The journey of a piece of food takes many steps in our digestive system. Teach your students all about this system and the organs that take part in digestion, as well as the pancreas, liver or gallbladder, with these slides filled with illustrations of the human body and its organs. Show them where they’re located and their important functions in our lives.

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 34 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

Register for free and start editing online

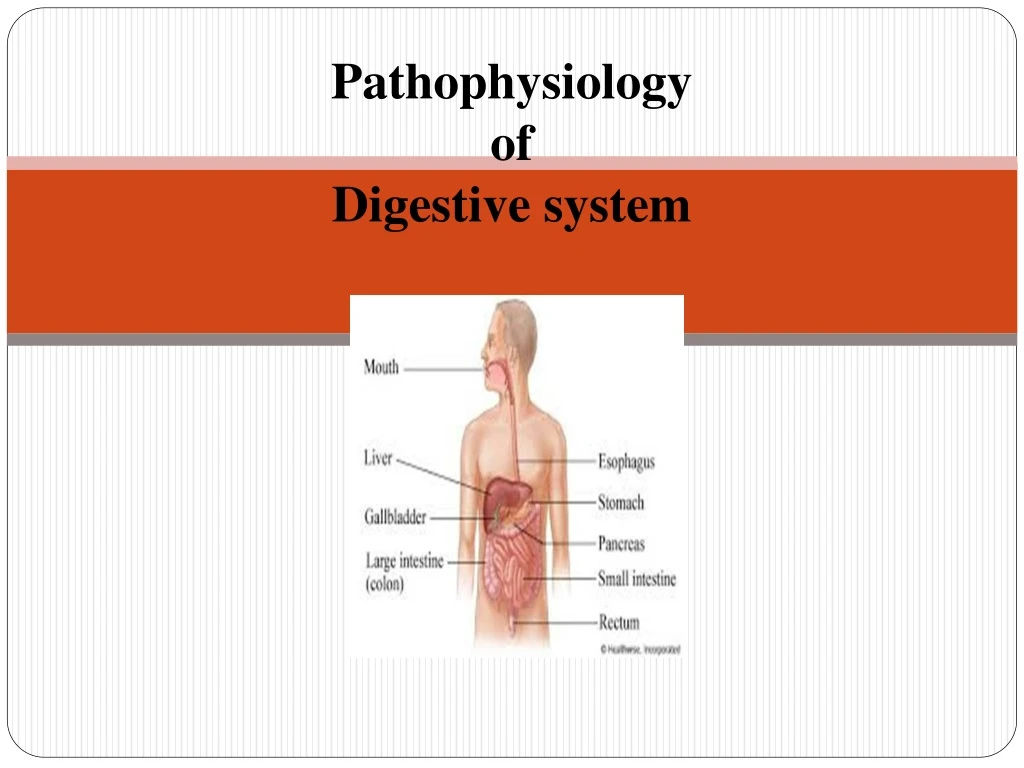

Pathophysiology of Digestive system

Nov 07, 2019

500 likes | 551 Views

Pathophysiology of Digestive system. Structure of alimentary canal. Extending from mouth to anus. Is about 4.5-6 meters in length. It consists of: 1-Mouth 2-Oral Cavity 3-Pharynx 4-Esophagus 5-Stomach 6-Small intestine: Duodenum, Jejunum and ileum 7-Large intestine: 9-Anal canal.

Share Presentation

- abdominal pain

- chronic gastritis

- means inflammation

- small intestine duodenum

- 4 abnormal fat metabolism

Presentation Transcript

Structure of alimentary canal • Extending from mouth to anus. • Is about 4.5-6 meters in length. • It consists of: 1-Mouth 2-Oral Cavity 3-Pharynx 4-Esophagus 5-Stomach 6-Small intestine: Duodenum, Jejunum and ileum 7-Large intestine: 9-Anal canal

Accessory structures • Not in tube path • Organs • Teeth • Tongue • Salivary glands • Liver • Gall bladder • Pancreas

Functions of The Digestive System 4 Functions: 1- Motility 2- Secretion 3- Digestion 4- Absorption

General Symptoms of GI diseases 1-Anorexia : loss of appetite 2-Nausea 3-Vomiting 4-Diarrhea , constipation 5-Abdominal pain: which may be burning, dull aching or colicky (means gradually becoming worse, then easing off again.) 6-Bleeding: obvious or occult 7- Heartburn 8- Indigestion, bloating

GI diseases

Dysphagia • Difficulty swallowing. • It is usually a sign of a problem with throat or esophagus,( the muscular tube that moves food and liquids from the back of mouth to stomach Risk factors • Aging. • Certain health conditions. People with certain neurological or nervous system disorders are more likely to experience difficulty swallowing.

Symptoms • Having pain while swallowing • Being unable to swallow • Having the sensation of food getting stuck in your throat or chest or behind your breastbone (sternum) • Drooling • Coughing when swallowing

Causes: • There are two types of problems : • * Impaired motility of esophageal wall (the muscles and nerves that help move food through the throat and esophagus are not working right) caused by neurologic disorders: e.g. brain injury, stroke or parkinson’s disease • *Something is blocking throat or esophagus (esophageal obstruction), this may happen in case of tumors

Gastritis • Gastritis means inflammation of the gastric mucosa. • Gastritis may occur suddenly (acute gastritis), or it can occur slowly over time (chronic gastritis). Weaknesses in the mucus-lined barrier that protects stomach wall allow digestive juices to damage and inflame stomach lining.

What Are the Symptoms of Gastritis? • upper abdominal pain • indigestion or bloating • nausea and vomiting • belching • loss of appetite or weight loss In more extreme cases, you may experience stomach bleeding and/or black stools

Causes of Gastritis • Long-term use of certain medications (aspirin) • Excessive alcohol consumption • Bacteria that cause stomach ulcers (H. pylori) • Certain illnesses (kidney failure) • A viral infection in a weakened immune system • Persistent, intense stress

1- Acute Gastritis • Acute gastritis refers to a transient inflammation of the gastric mucosa. • It is most commonly associated with local irritants such as bacterial endotoxins, alcohol, and aspirin.

2- Chronic Gastritis • Involves swelling or inflammation of the stomach lining • There are three major types of chronic gastritis: • Type A is caused by immune system destroying stomach cells. • Type B, the most common type, is caused by Helicobacter • pylori bacteria, and can cause stomach ulcers, intestinal ulcers, and cancer. • Type C is caused by chemical irritants like alcohol.

Complications of chronic gastritis • Gastric atrophy 2. Achlorhydria: it means that stomach fails to secret hydrochloric acid. 3. Pernicious anemia: the loss of the stomach to secret intrinsic factor will cause the loss of the ability to absorbed vitamin B12. Vitamin B12 is needed for normal production of RBC this is why its deficiency causes Pernicious anemia.

Peptic ulcer • Is an open sores that develop on the inside lining of stomach and the upper portion of small intestine caused by the digestive action of gastric juice. Peptic ulcers include: Gastric ulcers that occur on the inside of the stomach Duodenal ulcers that occur on the inside of the upper portion of small intestine (duodenum)

Site : • - First few centimeters of the duodenum (most frequent site). • - Along the lesser curvature of antral region • - Lower end of esophagus (rare).

Pathophysiology of peptic ulcer • The basic cause of peptic ulcer is too much secretion of gastric juice in relation to the degree of protection by gastroduodenal mucosal barrier • So, peptic ulcers are caused by A. Excess secretion of acid and pepsin by gastric mucosa. B. Decreased capability of gastroduodenal mucosal barrier to protect against the digestive action of acid-pepsin complex. e.g, 1-Stress ,2. Alcohols ,3. Aspirin. 4. Salts and sugars of high concentrations.

Peptic Ulcer (contin) • Manifestations: 1- Burning stomach pain 2-GI bleeding 3- The vomiting of blood — which may appear red or black 4- Dark blood in stools or stools that are black 5- Nausea or vomiting • Treatment: 1-Avoidance of smoking 2-Antibiotics to treat H.pylori 3-Antacids that neutralize stomach acid 4- Medications that block acid production (Proton pump) inhibitors reduce stomach acid 5-Surgical Treatment : used when medical treatment fails.

Intestine: irritable bowel syndrome • One of the most common GI disorders that affects the large intestine (colon). • Symptoms: 1-GI pain 2-Gas bloating 3-Altered bowel functions: diarrhea or constipation • Cause: hypereactivity of the bowels.

It doesn't cause changes in bowel tissue or increase risk of colorectal cancer. Only a small number of people with irritable bowel syndrome have severe signs and symptoms. Some people can control their symptoms by managing diet, lifestyle and stress. Others will need medication and counseling

Causes It's not known exactly what causes irritable bowel syndrome, but a variety of factors play a role. The walls of the intestines are lined with layers of muscle that contract and relax in a coordinated rhythm If you have irritable bowel syndrome, the contractions may be stronger and last longer than normal, causing gas, bloating and diarrhea. Or the opposite may occur, with weak intestinal contractions slowing food passage and leading to hard, dry stools.

Common triggers include Foods Stress Hormones Other illnesses • Treatment: • 1-Tranquilizers • 2-Dietary: increased fiber consumption • 3-Symptomatic treatment as antidiarrhea and antispasmodic

Gall bladder • Gall bladder is a sac-like structure that stores bile formed in the liver • At time of meal its wall contract , so bile passes to the duodenum • In the duodenum, bile salts cause fat digestion and absorption • Bile is composed of : water, bile salts, cholesterol and bile pigments (bilirubin)

Gall stone formation (Cholelithiasis) • Is the most common disorder in digestive system • Predisposing factors: • 1- Aging • 2- Excess cholesterol • 3- Obesity • 4- Abnormal fat metabolism

Gall stone formation (Cholelithiasis) Types of gallstones •Cholesterol gallstones. Is the most common type of gallstone, often appears yellow in color. These gallstones are composed mainly of undissolved cholesterol, but may contain other components. •Pigment gallstones. These dark brown or black stones form. They're made up of bilirubin • Manifestations: 1- Acute and severe abdominal pain 2- Nausea, vomiting, fever and chills 3- Jaundice if obstruction occurs • Diagnosis: 1- Radiography 2- Ultrasonography 3- Cholecystoscopy

Gall stone formation (contin) • Treatment: 1- Surgical removal of gall bladder (Cholecystectomy) 2- Endoscopic removal of gall stones 3-Lithotripsy: use of ultrasound waves to break up the gall stones 4- Low fat diet • N.B. Cholecystitis: is an acute or chronic inflammation of gall bladder. Most commonly caused by the presence of gall stones. Treatment like that of gall stone formation.

Liver: Functions 1- Carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism 2- Metabolism of steroid and sex hormones 3- Formation of bile and elimination of bilirubin 4- Synthesis of plasma proteins and clotting factors 5- Storage of glycogen, minerals and vitamins 6- Drug metabolism

Liver: Hepatitis • Definition: means inflammation and possible injury of the liver. • Causes: 1- Viruses (most important) 2- Alcohol 3- Toxins 4- Drugs

Viral Hepatitis • Means inflammation of the liver caused by viral infection. • Hepatitis viruses include: A,B,C,D and E • All hepatitis viruses target the liver cells as their site of infection and replication • Manifestations of viral hepatitis: 1-Range from asymptomatic to severe 2-Fatigue, malaise, anorexia and nausea 3-Jaundice 4-Liver inflammation and abdominal pain 5-Abnormal liver functions and enzyme levels.

Hepatitis B This type is transmitted through Sexual contact. Sharing of needles. Accidental needle sticks. Mother to child Hepatitis A This type of hepatitis is most commonly transmitted by consuming food or water contaminated by feces from a person infected with hepatitis Being in close contact with a person who's infected —

Hepatitis C is transmitted through direct contact with infected body fluids, typically through injection drug use and sexual contact Hepatitis D HDV is contracted through puncture wounds or contact with infected blood

Treatment of hepatitis • Many hepatitis infections will resolve within 4-8 weeks without treatment. The long- term course of hepatitis B and C make it less predictable. • Alpha interferon (IM or SC) is used for both treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C. • IV glucose administration if oral intake is inadequate. • Avoidance of active exercise.

Cirrhosis • Cirrhosis is characterized by diffuse scarring and fibrosis of the liver in response to chronic inflammation and injury. • Manifestations of liver cirrhosis: 1- Hepatosplenomegaly 2- Portal hypertension is (an increase in the blood pressure within a system of veins called the portal venous system) 3- Ascites 4- Edema 5- Esophageal varices(enlarged veins in the lower part of the esophagus ) and hematemesis (the vomiting of blood) 6- Liver failure 7- Jaundice 8- Hepatic encephalopathy 9- Hepatorenalsyndrome

Treatment of liver cirrhosis 1-Nutritional and vitamin supplementation. Reduced-protein diet is useful to decrease ammonia 2- Diuretics to relieve fluid accumulation 3-Management of symptoms

Formation of bile pigments • Old red blood cells become too fragile to exist in the circulatory system. Their cell membrane rupture and the released hemoglobin is phagocytosed by the reticuloendothelial system (REs). Here, the hemoglobin splits into globin and heme and the heme ring is opened to give a) Free iron that is transported in the blood by transferrin, b) Bilivirdin, the first bile pigment which is rapidly reduced to bilirubin which is gradually released from RES into the plasma. • The free bilirubin immediately combines strongly with plasma albumin to form hemebilirubin, free or unconjugatedbilirubin.

Formation of bile pigments • Within hours, the bilirubin is absorbed through the hepatic cell membrane, leaving the plasma albumin. • Inside the liver cells, bilirubin is conjugated with either glucuronic acid or sulphateto form conjugated bilirubin (cholebilirubin) • In the intestine, the conjugated bilirubin (cholebilirubin) is converted by bacterial action to urobilinogen where, - 25% is reabsorbed by the intestine to the liver. 20% is resecreted by the liver back into the gut and 5% is excreted in the urine. After exposure of the urine to air, urobilinogen is oxidized into urobilin. - 75% is converted to stercobilinogen. After exposure of feces to air stercobilingen is oxidised to stercobilin that causes the normal brownish colour of the stools.

Jaundice • Definition : yellowish colouration of the skin and mucous membranes due to increased concentration of total bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinemia). Normally, total bilirubin (free and conjugated) is 0.5 mg/dl. Jaundice appears when the concentration of total bilirubin in blood rises above 1.5 mg/dl.

Causes and Types of jaundice 1. Hemolytic (prehepatic) jaundice : - Caused by increased destruction of RBCs (hemolysis) • The rate of formation and excretion of bilirubin is increased, however, the rate of formation exceeds the rate of hepatic uptake. • 2. Obstructive or cholestatic (post'hepatic) jaundice : • Caused by obstruction of the biliary passages. 3. Hepatogenous (Hepatic) Jaundice - Caused by damage of the liver cells mainly as a result of viral hepatitis. • The diseased liver cells are unable to take all the hemebilirubin formed, increasing hembilirubin concentration in the blood.

- More by User

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM. GENERAL. 1 st System to Develop “Tube” Within a Tube Contents Remain External Until Absorbed Through Walls Humans are (Anatomical) Omnivores Consists of Alimentary Canal/Digestive Tract and Accessory Organs. DIGESTIVE SYSTEM FUNCTIONS.

2.99k views • 45 slides

Digestive System

Digestive System. J. Hinson Human Anatomy and Physiology. http://connection.lww.com/products/stedmansmedict/primalpictures.asp. I. Introduction. Digestion Includes Alimentary Canal (aliment/o = nourish) : mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine

2.21k views • 36 slides

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM. lecture no. 1 RESPIRATORY INSUFFICIENCY and acute (adult) respiratory distress syndrome ( ARDS). P. Marsalek, (with J. Kofranek, E. Necas), one of next lectures also by Z. Humlova. Outline. We use definitions of :

955 views • 68 slides

digestive system

digestive system. Structure. Abdominal Quadrants. Abdominal Regions . Mouth. where the digestive process begins consists of the tongue, salivary glands, teeth, and pharynx. Esophagus. A tube 10 to 12 inches long that carries food from the mouth to the stomach. Stomach.

926 views • 27 slides

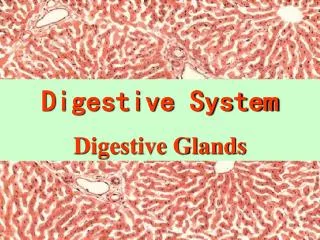

Digestive System Digestive Glands

Digestive System Digestive Glands. Components of Digestive Glands. ◇ small digestive glands: found in the wall of digestive tract. ◇ accessory glands (large digestive glands):. salivary glands pancreas liver. General Structure of Digestive Glands.

2.15k views • 82 slides

Human Digestive Digestive System - YouTube.flv System

Human Digestive Digestive System - YouTube.flv System. http://vimeo.com/76306734 Video link. 5 Digestion Processes (IDAAE). Ingestion : taking in of food into the body. Digestion : breaking down of food into simpler substances

1.29k views • 31 slides

CLINICAL PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF KIDNEY SYSTEM

CLINICAL PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF KIDNEY SYSTEM. Nephrological syndromes.

745 views • 38 slides

Digestive System. The Digestive Process. During digestion, food is broken down into forms that the body can use. This breaking down process involves both physical and chemical changes in the food. What is physical change?. It is a change in the physical properties of a substance.

184 views • 7 slides

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM. 3 major components: Oral cavity. Alimentary canal. Associated Glands: Salivary glands. Liver. Pancreas. Wall of the Alimentary Canal. Four concentric layers: Mucosa : Epithelial Lining: Simple columnar epithelium (in stomach & intestine). Lamina propria :

687 views • 20 slides

Digestive System. Anatomy Alimentary canal or gastrointestinal tract Mouth (Oral cavity) with tongue and teeth Pharnyx Esophagus (gullet) Four layers Mucosa-innermost, moistened layer Submucosa-contains blood vessels, nerve endings Muscularis Externa-muscle layer

303 views • 25 slides

Digestive system

Digestive system. Aerik, Damon ,David. Major organs. Mouth You Chou and then the tongue splits your food apart . Make’s saliva and breaks down chemicals. The tongue pushes food around When your food is chewed up it is called Bolus Trachea Swallow the food. esophagus.

184 views • 12 slides

Digestive System Digestive Glands. Components of Digestive Glands. Salivary glands Pancreas Liver. Small digestive glands: found in the wall of digestive tract Accessory glands (large digestive glands). General structure of Digestive Glands. Parenchyma: (functional portion of an organ )

1.71k views • 70 slides

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM DISORDERS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM DISORDERS. Mehtap KACAR KOÇAK M.D. PhD Pathophysiologist. Learning Objectives. Describe to Cell adhesion molecules Describe to injury of ischemia-reperfusion Describe to atherosclerosis Describe to hypertension Ischemic heart diseases

2.43k views • 184 slides

Digestive System. Ch 23. What is the function of the digestive system?. Provide the body w/nutrients, water and electrolytes. The organs of this system are responsible for: Food ingestion Digestion Absorption Elimination

767 views • 65 slides

Digestive System. Chapter 22 – Day 4. Large Intestine – Digestion. Digestion of Macromolecules Lipids (Fats): Fats are broken up into smaller globules Emulsification requires bile Fats → Fatty Acids (monoglycerides): needs lipase Nucleic Acids

316 views • 21 slides

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM. Oral cavity & salivary glands Originally given BY: Dr. ALI ALTIB Done and typed by: د. شموخ Edited & made up 2 date by: Abo Malek Thanks for: Dr.Abdullah. Digestive System. Consists of : Oral cavity ( mouth cavity ). Alimentary tract. Glands. THE ORAL Mucosa.

554 views • 40 slides

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF RESPIRATORY SYSTEM DISEASES

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF RESPIRATORY SYSTEM DISEASES. Mehtap KAÇAR KOÇAK M.D. PhD Yeditepe University Medicine School, Pathophysiology. General Introduction. Respiratory diseases is often classified as acute or chronic, obstructive or restrictive, and infectious or noninfectious.

1.96k views • 184 slides

Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular System

Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular System. Lecture # 3. Mrs.Iman Alajeyan [email protected]. Circulation of blood. The human circulatory system is a two-part system :

469 views • 32 slides

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NERVOUS SYSTEM DISEASES

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NERVOUS SYSTEM DISEASES. OVERWIEV. Seizures and Epilepsy Cerebrovascular Diseases (Ischemic stroke) Dementias (Alzheimer’s Disease) Movement Disorders (Parkinson’s Disease) Motor Neuron Diseases (ALS) Demyelinating Diseases (Multiple Sclerosis)

1.57k views • 151 slides

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NERVOUS SYSTEM DISEASES. Mehtap KAÇAR KOÇAK MD PhD Yeditepe University Medicine School. OVERWIEV. 1- Alterations in Cognitive Networks 2- Seizures and Epilepsy 3- Cerebrovascular Diseases (Ischemic stroke) 4- Dementias (Alzheimer’s Disease)

1.58k views • 154 slides

Pathophysiology of Respiratory system

Pathophysiology of Respiratory system. Lecture # 6. What is the respiratory system? Respiratory system is made up of the organs in your body that help you to breathe. Remember, that Respiration = Breathing .

442 views • 32 slides

Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular System. Lec.4. Cardiac Ischemia (myocardial ischemia). Occurs when blood flow to your heart muscle is decreased by a partial or complete blockage of your heart's arteries (coronary arteries). The decrease in blood flow reduces your heart's oxygen supply .

414 views • 34 slides

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Jonida Kollcaku. Digestive system ppt. Education. 1 of 43. Download now. Each type of tooth will appear then a diagram will appear. The diagram is has an arrow pointing to the tooth and is emphasised to show the tooth. Each item comes in separately so that you have time to explain the tooth and get students to see if they can identify their own ...

Structures and functions of the human digestive system. The abdominal organs are supported and protected by the bones of the pelvis and ribcage and are covered by the greater omentum, a fold of peritoneum that consists mainly of fat. The digestive tract begins at the lips and ends at the anus. It consists of the mouth, or oral cavity, with its ...