Peer-reviewed journal articles

- Overview of peer review

- Scholarly and academic - good enough?

- Find peer-reviewed articles

Using Library Search

Is a journal peer reviewed, check the journal.

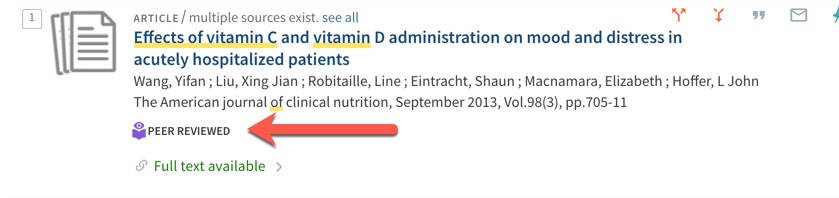

Resources listed in Library Search that are peer reviewed will include the Peer Reviewed icon.

For example:

If you have not used Library Search to find the article, which may indicate if it's peer reviewed, you can use Ulrichsweb to check.

- Go to Ulrichsweb

Screenshot of search box in UlrichsWeb © Proquest

- Enter the journal title in the search box.

Screenshot of results list in UlrichsWeb © Proquest

- If there are no results, do a search in Ulrichsweb to find journals in your field that are peer reviewed.

Be aware that not all articles in peer reviewed journals are refereed or peer reviewed, for example, editorials and book reviews.

If the journal is not listed in Ulrichsweb :

- Go to the journal's website

- Check for information on a peer review process for the journal. Try the Author guidelines , Instructions for authors or About this journal sections.

If you can find no evidence that a journal is peer reviewed, but you are required to have a refereed article, you may need to choose a different article.

- << Previous: Find peer-reviewed articles

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2023 2:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/how-to-find/peer-reviewed-articles

Ask A Librarian

- Webster University Ask a Librarian

Q. How can I tell if an article is peer reviewed?

- Ask a Librarian

- Tashkent Campus FAQs

- 24 Articles

- 10 Business

- 6 Citations

- 17 Databases

- 3 Dissertations

- 6 Full-text

- 1 ID numbers

- 11 Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- 2 International campuses

- 40 Library info

- 2 Peer-review

- 4 St. Louis campuses

- 16 Technology

- 2 Textbooks

- 13 University info

Answered By: Georgiana Grant Last Updated: Jan 04, 2024 Views: 20968

Peer Reviewed Articles go through a process in which experts in the field (the author's peers) verify that the information and research methods are up to standards. Peer reviewed articles are usually research articles or literature reviews and have certain characteristics in common. This page has an overview on how to identify peer reviewed articles: Recognize a scholarly/peer-reviewed article .

The journal publisher's website

If you are unsure whether or not an article is peer reviewed, you must look at the journal rather than the article. One of the best places to find out if a journal is peer-reviewed is the journal website. Most publications have a journal website that includes information for authors about the publication process. If you find the journal website, look for the link that says information for authors, instructions for authors, guidelines for authors or something similar. On this page is information about whether the articles are peer reviewed.

Article found in a library database

In an Ebsco database, you will look at the detailed record of the article (you will see this when you click on the title of a search result). Then click on the Source (the name of the publication):

You will then see information about the specific journal. The last item on the list will be a simple yes or no to your question:

Other databases may provide the same information using different words or visual cues. If you are still unsure, please give us a call, chat with us, or send us an email and a Research Librarian can help you.

Links & Files

- How do I find an academic article (also called a peer reviewed or scholarly article)?

- Evaluating Information

Comments (0)

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 7 No 0

Related Topics

- Peer-review

Need Help? Ask us!

24/7 Chat

Email us

Subject Librarians

Research: 314-246-6950

Circulation: 314-246-6952

Library hours

Report an issue with eResources

Faculty and researchers : We want to hear from you! We are launching a survey to learn more about your library collection needs for teaching, learning, and research. If you would like to participate, please complete the survey by May 17, 2024. Thank you for your participation!

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

- University Libraries

Peer Reviewed Articles: What Are They?

- How to Tell if a Journal Article is Peer Reviewed

- Review Articles

- Types of Literature Sources, (Grey Literature)

- What are Evidence Based Reviews?

Peer Reviewed?

How do you determine whether an article qualifies as being a peer-reviewed journal article?

First, you need to be able to identify which journals are peer-reviewed. There are generally four methods for doing this

- Limiting a database search to peer-reviewed journals only. You can do this in the Article Quick Search tab in the Library's home page.

- Some databases allow you to limit searches for articles to peer reviewed journals only.

- If you cannot limit your initial search to peer-reviewed journals, you will need to check if the individual journal where the article was published is a peer-reviewed journal. You may want to utilize Method 3 below.

- Examining the publication to see if it is peer-reviewed.

If the first two methods described above did not identify the journal,(and the article), as peer-reviewed, you may then need to examine the journal physically or look at additional pages of the journal online to determine if it is peer-reviewed. This method is not always successful with resources available only online. Try the following steps:

- Locate the journal in the Library or online, then identify the most current entire year’s issues.

- Locate the masthead of the publication. This usually consists of a box towards either the front or the end of the periodical, and contains publication information such as the editors of the journal, the publisher, the place of publication, the subscription cost and similar information. It is way easier to find in a print copy of the journal

- Does the journal say that it is peer-reviewed? If so, you’re done. If not, search farther within the journal's website.

- Check in and around the masthead to locate the method for submitting articles to the publication. If you find information similar to “to submit articles, send three copies…”, the journal is probably peer-reviewed . In this case, you are inferring that the publication is then going to send the multiple copies of the article to the journal’s reviewers. This may not always be the case, so relying upon this information alone may not be foolproof.

- If you do not see this type of statement in the first issue of the journal that you look at, examine the remaining issues to see if this information is included. Sometimes publications will include this information in only a single issue a year.

- Is it scholarly, using technical terminology? Is the article format similar to the following - abstract, literature review, methodology, results, conclusion, and references? Are the articles written by scholarly researchers in the field? Is advertising non-existent, or kept to a minimum? Are there references listed in footnotes or bibliographies? If you answered yes to all these questions, the journal may very well be peer-reviewed. This determination would be strengthened by having met the previous criterion of a multiple-copies submission requirement. If you answered these questions no, the journal is probably not peer-reviewed.

- Find the journal web site on the internet, (not via library databases), and see if it states that the journal is peer-reviewed. Check the site URL to be sure it is the homepage of the journal or of the publisher of the journal.

Adapted from "How to Recognize Peer Reviewed Journals" , Angelo State University

- << Previous: What is a Scholarly or Peer Reviewed Article?

- Next: Types of Health Articles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 3:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uml.edu/healtharticle_types

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

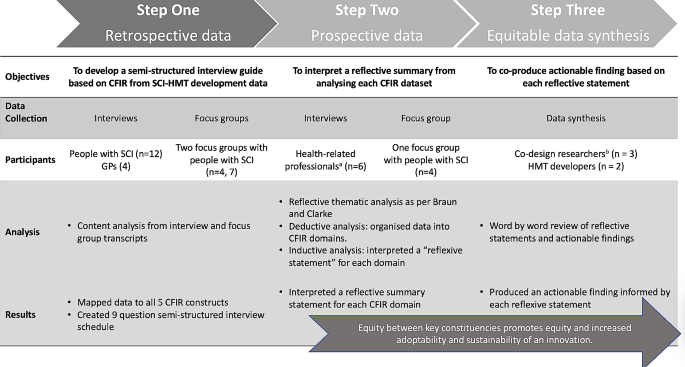

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Article Writing

How to Know if an Article Is Peer Reviewed

Last Updated: May 16, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Shweta Sharma . Shweta Sharma is a Biologist with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). With nearly ten years of experience, she specializes in insect management, integrated pest management, insect behavior, resistance management, ecology, and biological control. She earned her PhD in Urban Entomology and her MS in Environmental Horticulture from the University of Florida. She also holds a BS in Agriculture from the Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences, Nepal. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 66,242 times.

For an academic article to be peer-reviewed, journal editors send the article to researchers and scholars in the same field. The reviewers examine the article's research, data, and conclusions, and decide if the article deserves to be published. Peer-reviewed journal articles are more reliable, and should be your go-to for academic research. To determine if an article is peer-reviewed, you can look up the journal in an online database or search the journal's website.

Looking up the Journal in an Online Database

- If you found your article in a catalog, the journal name will be listed there.

- Some databases you can try are Academic Search Premiere, AcademicOneFile, or Ulrich's Periodical Directory.

- If you're not a student, check if your local library provides access. Some cities, counties, and states have libraries that buy access to databases. [3] X Research source

- Another word that is sometimes used is “refereed,” which means the same thing as peer-reviewed.

Finding out from the Journal Website

- If your article is in a paper journal, you can simply check the cover.

- If the article is from a newspaper or a blog, it's not an academic article!

- Peer review is also called “blind peer review,” “scholarly peer review,” and “refereed.” [8] X Research source

- Look for pages with titles like, “about us,” “submission guidelines,” and “editorial policies.”

Expert Q&A

- Dissertations aren't considered peer reviewed, because they are still student work. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

Expert Interview

Thanks for reading our article! If you’d like to learn more about caring for insects, check out our in-depth interview with Shweta Sharma .

- ↑ https://www.angelo.edu/library/handouts/peerrev.php

- ↑ https://guides.library.oregonstate.edu/c.php?g=285842&p=1906145

- ↑ https://medium.com/a-wikipedia-librarian/youre-a-researcher-without-a-library-what-do-you-do-6811a30373cd

- ↑ https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/peer-review

- ↑ https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/how-to-find/peer-reviewed-articles/check

- ↑ https://bowvalleycollege.libguides.com/c.php?g=10229&p=52137

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/library/verifypeerreview

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to know if an article is peer reviewed [6 key features]

Features of a peer reviewed article

How to find peer reviewed articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviewed articles, related articles.

A peer reviewed article refers to a work that has been thoroughly assessed, and based on its quality, has been accepted for publication in a scholarly journal. The aim of peer reviewing is to publish articles that meet the standards established in each field. This way, peer reviewed articles that are published can be taken as models of research practices.

A peer reviewed article can be recognized by the following features:

- It is published in a scholarly journal.

- It has a serious, and academic tone.

- It features an abstract at the beginning.

- It is divided by headings into introduction, literature review or background, discussion, and conclusion.

- It includes in-text citations, and a bibliography listing accurately all references.

- Its authors are affiliated with a research institute or university.

There are many ways in which you can find peer reviewed articles, for instance:

- Check the journal's features and 'About' section. This part should state if the articles published in the journal are peer reviewed, and the type of reviewing they perform.

- Consult a database with peer reviewed journals, such as Web of Science Master Journal List , PubMed , Scopus , Google Scholar , etc. Specify in the advanced search settings that you are looking for peer reviewed journals only.

- Consult your library's database, and specify in the search settings that you are looking for peer reviewed journals only.

➡️ Want to know if a source is scholarly? Check out our guide on scholarly sources.

➡️ Want to know if a source is credible? Find out in our guide on credible sources (+ how to find them).

A peer reviewed article refers to a work that has been thoroughly assessed, and based on its quality has been accepted to be published in a scholarly journal.

Once an article has been submitted for publication to a peer reviewed journal, the journal assigns the article to an expert in the field, who is considered the “peer”.

The easiest way to find a peer reviewed article is to narrow down the search in the "Advanced search" option. Then, mark the box that says "peer reviewed".

Consult a database with peer reviewed journals, such as Web of Science Master Journal List , PubMed , Scopus , etc.

There are many views on peer reviewed articles. Take a look at Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide for more insight on this topic.

- Course Reserves

- Google Scholar

- Site Search

I do not know if this article is scholarly or peer-reviewed

Scholarly articles (also known as academic articles ) are written by experts in a discipline for other experts in that field. They're usually published by a professional association or academic press. Their content focuses on research, has citations (like a bibliography or footnotes), and are professional in appearance with no spelling or grammatical errors, advertisements, or unrelated images.

Some scholarly articles go a bit further to be peer-reviewed . All peer-reviewed articles are scholarly articles, but not all scholarly articles are peer-reviewed.

NOTE : An article can be from a peer reviewed journal and not actually be peer reviewed. Editorials, news items, and book reviews do not necessarily go through the same review process. A peer reviewed article should be longer than just a couple of pages and include a bibliography.

There are several ways to determine whether or not an article is peer reviewed (also called refereed ).

1 . If you found the article using OneSearch , it will have a peer-reviewed icon:

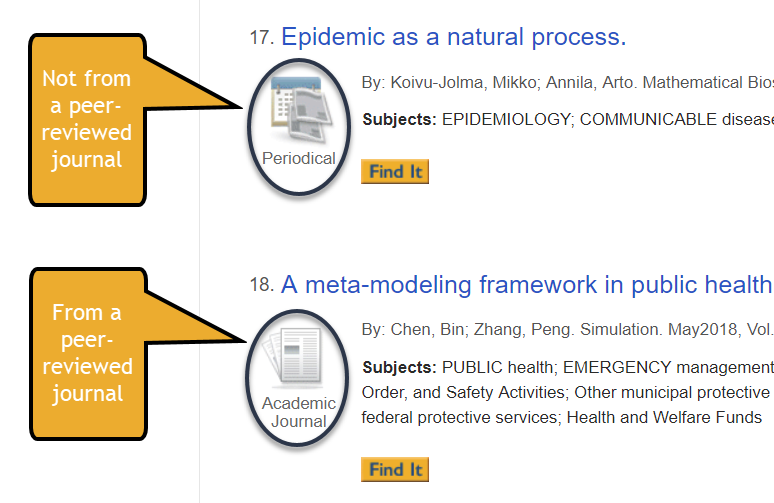

2. If you found the article in a library database, there may be some indicator as to whether the article is peer reviewed.

3. In the library databases, you might find that the journal name is a hyperlink as shown below. Clicking on it takes you to a page about the journal which should make it clear whether the journal is scholarly, academic, peer reviewed, or refereed.

4. You can look up the journal name in the library database called Ulrichs Web: Global Serials Directory (previously called Ulrichs Periodical Directory). Search for the journal title and find the correct entry in the results list. There may be multiple versions of the same journal--print, online, and microfilm formats--but there also may be two different journals with the same title.

Look to left of the title, and if you find a referee shirt icon , that means that the journal is peer-reviewed or refereed.

5. The publisher's website for the journal should indicate whether articles go through a peer review process. Find the instructions for authors page for this information.

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Finding Journal Articles 101

Peer-reviewed or refereed.

- Research Article

- Review Article

- By Journal Title

What Does "Peer-reviewed" or "Refereed" Mean?

Peer review is a process that journals use to ensure the articles they publish represent the best scholarship currently available. When an article is submitted to a peer reviewed journal, the editors send it out to other scholars in the same field (the author's peers) to get their opinion on the quality of the scholarship, its relevance to the field, its appropriateness for the journal, etc.

Publications that don't use peer review (Time, Cosmo, Salon) just rely on the judgment of the editors whether an article is up to snuff or not. That's why you can't count on them for solid, scientific scholarship.

Note:This is an entirely different concept from " Review Articles ."

How do I know if a journal publishes peer-reviewed articles?

Usually, you can tell just by looking. A scholarly journal is visibly different from other magazines, but occasionally it can be hard to tell, or you just want to be extra-certain. In that case, you turn to Ulrich's Periodical Directory Online . Just type the journal's title into the text box, hit "submit," and you'll get back a report that will tell you (among other things) whether the journal contains articles that are peer reviewed, or, as Ulrich's calls it, Refereed.

Remember, even journals that use peer review may have some content that does not undergo peer review. The ultimate determination must be made on an article-by-article basis.

For example, the journal Science publishes a mix of peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed content. Here are two articles from the same issue of Science .

This one is not peer-reviewed: https://science-sciencemag-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/content/303/5655/154.1 This one is a peer-reviewed research article: https://science-sciencemag-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/content/303/5655/226

That is consistent with the Ulrichsweb description of Science , which states, "Provides news of recent international developments and research in all fields of science. Publishes original research results, reviews and short features."

Test these periodicals in Ulrichs :

- Advances in Dental Research

- Clinical Anatomy

- Molecular Cancer Research

- Journal of Clinical Electrophysiology

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2023 9:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/journalarticles101

- Directories

- What is UW Libraries Search and how do I use it to find resources?

- Does the library have my textbook?

- Who can access databases, e-journals, e-books etc. and from where?

- How do I find full-text scholarly articles in my subject?

- How do I find e-books?

- How do I cite a source using a specific style?

- How do I find an article by citation?

- How do I renew books and other loans?

- Do I have access to this journal?

- How do I request a book/article we don't have?

- How do I request materials using Interlibrary Loan?

- What does the “Request Article” button mean?

- How do I connect Google Scholar with UW Libraries?

- How do I pay fines?

- How do I access resources from off-campus?

- How do I know if my sources are credible/reliable?

- How do I know if my articles are scholarly (peer-reviewed)?

- What is Summit?

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

FAQ: How do I know if my articles are scholarly (peer-reviewed)?

How to identify a scholarly, peer-reviewed journal article, what are scholarly, peer-reviewed journal articles.

Scholarly articles are those that are reviewed by multiple experts from their related field(s) and then published in academic journals. There are academic journals for every subject area. The primary purpose of scholarly journals is to represent and disseminate research and scholarly discussions among scholars (faculty, researchers, students) within, and across, different academic disciplines.

Scholarly peer-reviewed journal articles can be identified by the following characteristics:

- Author(s): They are typically written by professors, researchers, or other scholars who specialize in the field and are often identified by the academic institution at which they work.

- Purpose : They are published by professional associations, university publishers or other academic publishers to report research results or discuss ongoing research in detail.

- Language: They are highly specialized and may use technical language.

- Layout: They will cite their sources and include footnotes, endnotes, or parenthetical citations and/or a list of bibliographic references.

- Content : They may include graphs and tables and they undergo a peer review process before publication.

Helpful tips for finding scholarly articles:

What is a Scholarly Journal Article?

- << Previous: How do I know if my sources are credible/reliable?

- Next: What is Summit? >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 1:15 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/faq

What are Peer-Reviewed Journals?

- A Definition of Peer-Reviewed

- Research Guides and Tutorials

- Library FAQ Page This link opens in a new window

Research Help

540-828-5642 [email protected] 540-318-1962

- Bridgewater College

- Church of the Brethren

- regional history materials

- the Reuel B. Pritchett Museum Collection

Additional Resources

- What are Peer-reviewed Articles and How Do I Find Them? From Capella University Libraries

Introduction

Peer-reviewed journals (also called scholarly or refereed journals) are a key information source for your college papers and projects. They are written by scholars for scholars and are an reliable source for information on a topic or discipline. These journals can be found either in the library's online databases, or in the library's local holdings. This guide will help you identify whether a journal is peer-reviewed and show you tips on finding them.

What is Peer-Review?

Peer-review is a process where an article is verified by a group of scholars before it is published.

When an author submits an article to a peer-reviewed journal, the editor passes out the article to a group of scholars in the related field (the author's peers). They review the article, making sure that its sources are reliable, the information it presents is consistent with the research, etc. Only after they give the article their "okay" is it published.

The peer-review process makes sure that only quality research is published: research that will further the scholarly work in the field.

When you use articles from peer-reviewed journals, someone has already reviewed the article and said that it is reliable, so you don't have to take the steps to evaluate the author or his/her sources. The hard work is already done for you!

Identifying Peer-Review Journals

If you have the physical journal, you can look for the following features to identify if it is peer-reviewed.

Masthead (The first few pages) : includes information on the submission process, the editorial board, and maybe even a phrase stating that the journal is "peer-reviewed."

Publisher: Peer-reviewed journals are typically published by professional organizations or associations (like the American Chemical Society). They also may be affiliated with colleges/universities.

Graphics: Typically there either won't be any images at all, or the few charts/graphs are only there to supplement the text information. They are usually in black and white.

Authors: The authors are listed at the beginning of the article, usually with information on their affiliated institutions, or contact information like email addresses.

Abstracts: At the beginning of the article the authors provide an extensive abstract detailing their research and any conclusions they were able to draw.

Terminology: Since the articles are written by scholars for scholars, they use uncommon terminology specific to their field and typically do not define the words used.

Citations: At the end of each article is a list of citations/reference. These are provided for scholars to either double check their work, or to help scholars who are researching in the same general area.

Advertisements: Peer-reviewed journals rarely have advertisements. If they do the ads are for professional organizations or conferences, not for national products.

Identifying Articles from Databases

When you are looking at an article in an online database, identifying that it comes from a peer-reviewed journal can be more difficult. You do not have access to the physical journal to check areas like the masthead or advertisements, but you can use some of the same basic principles.

Points you may want to keep in mind when you are evaluating an article from a database:

- A lot of databases provide you with the option to limit your results to only those from peer-reviewed or refereed journals. Choosing this option means all of your results will be from those types of sources.

- When possible, choose the PDF version of the article's full text. Since this is exactly as if you photocopied from the journal, you can get a better idea of its layout, graphics, advertisements, etc.

- Even in an online database you still should be able to check for author information, abstracts, terminology, and citations.

- Next: Research Guides and Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Dec 12, 2023 4:06 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bridgewater.edu/c.php?g=945314

- Collections

- Services & Support

Which Source Should I Use?

- The Right Source For Your Need-Authority

- Finding Subject Specific Sources: Research Guides

- Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles

- Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles- Arts & Humanities

- How to Read a Journal Article

- Locating Journals

- How to Find Streaming Media

The Peer Review Process

So you need to use scholarly, peer-reviewed articles for an assignment...what does that mean?

Peer review is a process for evaluating research studies before they are published by an academic journal. These studies typically communicate original research or analysis for other researchers.

The Peer Review Process at a Glance:

Looking for peer-reviewed articles? Try searching in OneSearch or a library database and look for options to limit your results to scholarly/peer-reviewed or academic journals. Check out this brief tutorial to show you how: How to Locate a Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Article

Part 1: Watch the Video

Part 1: watch the video all about peer review (3 min.) and reflect on discussion questions..

Discussion Questions

After watching the video, reflect on the following questions:

- According to the video, what are some of the pros and cons of the peer review process?

- Why is the peer review process important to scholarship?

- Do you think peer reviewers should be paid for their work? Why or why not?

Part 2: Practice

Part 2: take an interactive tutorial on reading a research article for your major..

Includes a certification of completion to download and upload to Canvas.

Social Sciences

(e.g. Psychology, Sociology)

(e.g. Health Science, Biology)

Arts & Humanities

(e.g. Visual & Media Arts, Cultural Studies, Literature, History)

Click on the handout to view in a new tab, download, or print.

For Instructors

- Teaching Peer Review for Instructors

In class or for homework, watch the video “All About Peer Review” (3 min.) .

Video discussion questions:

- According to the video, what are some of the pros and cons of the peer review process

Assignment Ideas

- Ask students to conduct their own peer review of an important journal article in your field. Ask them to reflect on the process. What was hard to critique?

- Have students examine a journals’ web page with information for authors. What information is given to the author about the peer review process for this journal?

- Assign this reading by CSUDH faculty member Terry McGlynn, "Should journals pay for manuscript reviews?" What is the author's argument? Who profits the most from published research? You could also hold a debate with one side for paying reviewers and the other side against.

- Search a database like Cabell’s for information on the journal submission process for a particular title or subject. How long does peer review take for a particular title? Is it is a blind review? How many reviewers are solicited? What is their acceptance rate?

- Assign short readings that address peer review models. We recommend this issue of Nature on peer review debate and open review and this Chronicle of Higher Education article on open review in Shakespeare Quarterly .

Proof of Completion

Mix and match this suite of instructional materials for your course needs!

Questions about integrating a graded online component into your class, contact the Online Learning Librarian, Rebecca Nowicki ( [email protected] ).

Example of a certificate of completion:

- << Previous: Finding Subject Specific Sources: Research Guides

- Next: Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles- Arts & Humanities >>

- Last Updated: Dec 11, 2023 4:29 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sdsu.edu/WhichSource

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between peer-reviewed (scholarly) articles and everything else.

Peer-reviewed articles, also known as scholarly articles, are published based on the approval of a board of professional experts in the discipline relating to the article topic.

For instance, a paper discussing the psychological effects of homeschooling a child would need to be reviewed by a board of psychology scholars and professional psychologists in order to be approved for publication in a psychology journal.

Scholarly/peer-reviewed articles differ from other easily available print sources because the review process gives them more authority than, for example, a newspaper or magazine article.

Newspaper or popular magazine articles are written by journalists (not specialists in any field except journalism).

They are reviewed only by the magazine/newspaper editors (also not specialists in any field except editing).

For more information, see: https://wrtg150.lib.byu.edu/finding-sources .

- Research and Writing

Updated 2024-03-07 14:35:37 • LibAnswers page

- Library databases

- Library website

Evaluating Resources: Research Articles

Research articles.

A research article is a journal article in which the authors report on the research they did. Research articles are always primary sources. Whether or not a research article is peer reviewed depends on the journal that publishes it.

Published research articles follow a predictable pattern and will contain most, if not all, of the sections listed below. However, the names for these sections may vary.

- Title & Author(s)

- Introduction

- Methodology

To learn about the different parts of a research article, please view this tutorial:

Short video: How to Read Scholarly Articles

Learn some tips on how to efficiently read scholarly articles.

Video: How to Read a Scholarly Article

(4 min 16 sec) Recorded August 2019 Transcript

More information

The Academic Skills Center and the Writing Center both have helpful resources on critical and academic reading that can further help you understand and evaluate research articles.

- Academic Skills Center Guide: Developing Your Reading Skills

- Academic Skills Center Webinar Archive: Savvy Strategies for Academic Reading

- Writing Center Podcast: WriteCast Episode 5: Five Strategies for Critical Reading

If you'd like to learn how to find research articles in the Library, you can view this Quick Answer.

- Quick Answer: How do I find research articles?

- Previous Page: Primary & Secondary Sources

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Evidence-Based Health Care

- Learning About EBP

- The 6S Pyramid

- Forming Questions

- Identifying Peer-Reviewed Resources

What is Peer Review?

If an article is peer reviewed , it was reviewed by scholars who are experts in related academic or professional fields before it was published. Those scholars assessed the quality of the article's research, as well as its overall contribution to the literature in their field.

When we talk about peer-reviewed journals , we're referring to journals that use a peer-review process.

Related terms you might hear include:

- Academic: Intended for academic use, or an academic audience.

- Scholarly: Intended for scholarly use, or a scholarly audience.

- Refereed: Refers to a specific kind of peer-review process.

National University Library System. (2018). "Find Articles: How to Find Scholarly/Peer-Reviewed Articles". Retrieved from: http://nu.libguides.com/articles/PR.

How Do I Know If a Journal is Peer-Reviewed?

The easiest way to find out if a journal is peer-reviewed is to search for the title in a serials directory like UlrichsWeb:

- UlrichsWeb Global Serials Directory Includes in each record: ISBN, title, publisher, country of publication, status (Active, ceased, etc.), start year, frequency, refereed (Yes/No), media, language, price, subject, Dewey #, circulation, editor(s), email, URL, brief description Also known as: Ulrichs

- Type the name of the journal in the search bar and click the search button. NOTE: you need to use the full name of the journal, not an abbreviation.

- Locate the journal in the results list. You may see multiple entries for one journal because Ulrichs lists print, electronic, and international version separately.

How Do I Know If an Article is Peer-Reviewed?

Even if an article was published in a peer-reviewed journal, it may not necessarily be peer-reviewed itself; for example, a commentary article may undergo editorial review instead, meaning it was only reviewed by the journal editor.

There are some clues you can look for to help you identify if an article is peer-reviewed:

- Does the abstract discuss the author's/authors' research process?

- Does the abstract include a variation of the phrase "This study..."?

- Is there a Methodology or Data header in the text of the article?

- Does the paper discuss related research in a literature review?

- Is there an analysis of a need for further research, or gaps in the literature?

- Are the references for scholarly articles and books?

If an article published in a verified peer-reviewed journal includes these elements, it is most likely a peer-reviewed article.

- National University Library: Scholarly Checklist Use this printable checklist to help you identify scholarly, research-based articles

Peer Reviewed Material in PubMed & MEDLINE

Good news! Most of the journals in Medline/PubMed are peer reviewed. Generally speaking, if you find a journal citation in Medline/PubMed you should be just fine. However, there is no way to limit your results within the PubMed or the Medline on EBSCO interface to knock out the few publications that are not considered refereed titles.

However, EBSCO (a third-party vendor) does provide a list of all titles within Medline and lets you see which titles are considered peer reviewed. You can check if your journal is OK - see the "peer Review" tab in the report below to see the very small list of titles that don't make the cut.

- Medline: List of Full-Text Journals These journals cover a wide range of subjects within the biomedical and health fields containing information needed by doctors, nurses, health professionals, and researchers engaged in clinical care, public health, and health policy development. Information on peer-reviewed status available within table of titles.

Peer Reviewed Material in CINAHL and PsycINFO

Both The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) & PsycInfo databases, feature a Peer Reviewed subset. You can limit your search from the main search screen by checking the "Peer Review" box.

- What is the definition of peer review for the CINAHL products?

- << Previous: Forming Questions

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 9:13 AM

- URL: https://libguides.libraries.wsu.edu/EBHC

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

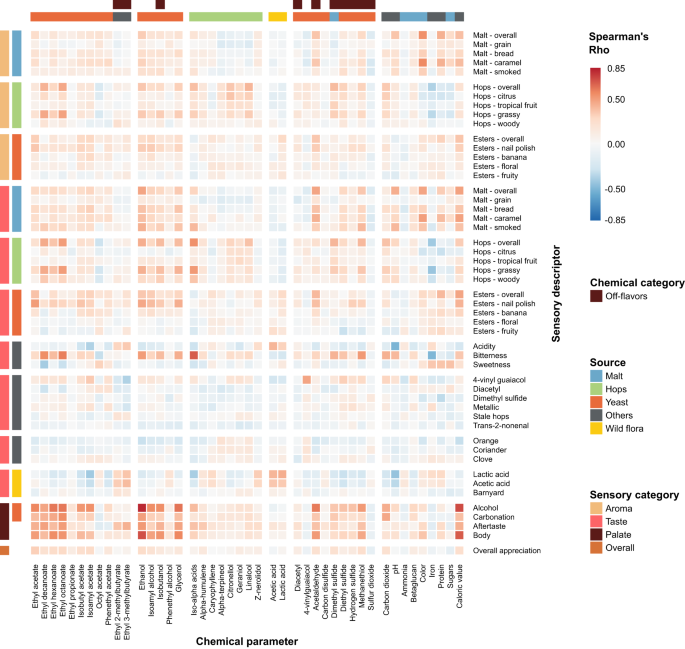

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].

Fake peer review, an extreme example of conflict of interest, is another form of misconduct that has surfaced in the time of mass proliferation of gold open-access journals and publication of articles without quality checks [ 38 ]. Fake reviews are generated by manipulating authors and commercial editing agencies with full access to their own manuscripts and peer review evaluations in the journal editorial management systems. The sole aim of these reviews is to break the manuscript evaluation process and to pave the way for publication of pseudoscientific articles. Authors of these articles are often supported by funds intended for the growth of science in non-Anglophone countries [ 39 ]. Iranian and Chinese authors are often caught submitting fake reviews, resulting in mass retractions by large publishers [ 38 ]. Several suggestions have been made to overcome this issue, with assigning independent reviewers and requesting their ORCID IDs viewed as the most practical options [ 40 ].

Conclusions

The peer review process is regulated by publishers and editors, enforcing updated global editorial recommendations. Selecting the best reviewers and providing authors with constructive comments may improve the quality of published articles. Reviewers are selected in view of their professional backgrounds and skills in research reporting, statistics, ethics, and language. Quality reviewer comments attract superior submissions and add to the journal’s scientific prestige [ 41 ].

In the era of digitization and open science, various online tools and platforms are available to upgrade the peer review and credit experts for their scholarly contributions. With its links to the ORCID platform and social media channels, Publons now offers the optimal model for crediting and keeping track of the best and most active reviewers. Publons Academy additionally offers online training for novice researchers who may benefit from the experience of their mentoring editors. Overall, reviewer training in how to evaluate journal submissions and avoid related misconduct is an important process, which some indexed journals are experimenting with [ 42 ].

The timelines and rigour of the peer review may change during the current pandemic. However, journal editors should mobilize their resources to avoid publication of unchecked and misleading reports. Additional efforts are required to monitor published contents and encourage readers to post their comments on publishers’ online platforms (blogs) and other social media channels [ 43 , 44 ].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Evaluating Information Sources: What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article?

- Should I Trust Internet Sources?

What Is A Peer-Reviewed Article?

Anali Perry, a librarian from Arizona State University Libraries, gives a quick definition of a peer-reviewed article.

The Library Minute: Academic Articles from ASU Libraries on Vimeo .