How to Write an Article Critique Step-by-Step

Table of contents

- 1 What is an Article Critique Writing?

- 2 How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

- 3 Article Critique Outline

- 4 Article Critique Formatting

- 5 How to Write a Journal Article Critique

- 6 How to Write a Research Article Critique

- 7 Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

- 8 Tips for writing an Article Critique

Do you know how to critique an article? If not, don’t worry – this guide will walk you through the writing process step-by-step. First, we’ll discuss what a research article critique is and its importance. Then, we’ll outline the key points to consider when critiquing a scientific article. Finally, we’ll provide a step-by-step guide on how to write an article critique including introduction, body and summary. Read more to get the main idea of crafting a critique paper.

What is an Article Critique Writing?

An article critique is a formal analysis and evaluation of a piece of writing. It is often written in response to a particular text but can also be a response to a book, a movie, or any other form of writing. There are many different types of review articles . Before writing an article critique, you should have an idea about each of them.

To start writing a good critique, you must first read the article thoroughly and examine and make sure you understand the article’s purpose. Then, you should outline the article’s key points and discuss how well they are presented. Next, you should offer your comments and opinions on the article, discussing whether you agree or disagree with the author’s points and subject. Finally, concluding your critique with a brief summary of your thoughts on the article would be best. Ensure that the general audience understands your perspective on the piece.

How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

If you are wondering “what is included in an article critique,” the answer is:

An article critique typically includes the following:

- A brief summary of the article .

- A critical evaluation of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

- A conclusion.

When critiquing an article, it is essential to critically read the piece and consider the author’s purpose and research strategies that the author chose. Next, provide a brief summary of the text, highlighting the author’s main points and ideas. Critique an article using formal language and relevant literature in the body paragraphs. Finally, describe the thesis statement, main idea, and author’s interpretations in your language using specific examples from the article. It is also vital to discuss the statistical methods used and whether they are appropriate for the research question. Make notes of the points you think need to be discussed, and also do a literature review from where the author ground their research. Offer your perspective on the article and whether it is well-written. Finally, provide background information on the topic if necessary.

When you are reading an article, it is vital to take notes and critique the text to understand it fully and to be able to use the information in it. Here are the main steps for critiquing an article:

- Read the piece thoroughly, taking notes as you go. Ensure you understand the main points and the author’s argument.

- Take a look at the author’s perspective. Is it powerful? Does it back up the author’s point of view?

- Carefully examine the article’s tone. Is it biased? Are you being persuaded by the author in any way?

- Look at the structure. Is it well organized? Does it make sense?

- Consider the writing style. Is it clear? Is it well-written?

- Evaluate the sources the author uses. Are they credible?

- Think about your own opinion. With what do you concur or disagree? Why?

Article Critique Outline

When assigned an article critique, your instructor asks you to read and analyze it and provide feedback. A specific format is typically followed when writing an article critique.

An article critique usually has three sections: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

- The introduction of your article critique should have a summary and key points.

- The critique’s main body should thoroughly evaluate the piece, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses, and state your ideas and opinions with supporting evidence.

- The conclusion should restate your research and describe your opinion.

You should provide your analysis rather than simply agreeing or disagreeing with the author. When writing an article review , it is essential to be objective and critical. Describe your perspective on the subject and create an article review summary. Be sure to use proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation, write it in the third person, and cite your sources.

Article Critique Formatting

When writing an article critique, you should follow a few formatting guidelines. The importance of using a proper format is to make your review clear and easy to read.

Make sure to use double spacing throughout your critique. It will make it easy to understand and read for your instructor.

Indent each new paragraph. It will help to separate your critique into different sections visually.

Use headings to organize your critique. Your introduction, body, and conclusion should stand out. It will make it easy for your instructor to follow your thoughts.

Use standard fonts, such as Times New Roman or Arial. It will make your critique easy to read.

Use 12-point font size. It will ensure that your critique is easy to read.

How to Write a Journal Article Critique

When critiquing a journal article, there are a few key points to keep in mind:

- Good critiques should be objective, meaning that the author’s ideas and arguments should be evaluated without personal bias.

- Critiques should be critical, meaning that all aspects of the article should be examined, including the author’s introduction, main ideas, and discussion.

- Critiques should be informative, providing the reader with a clear understanding of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

When critiquing a research article, evaluating the author’s argument and the evidence they present is important. The author should state their thesis or the main point in the introductory paragraph. You should explain the article’s main ideas and evaluate the evidence critically. In the discussion section, the author should explain the implications of their findings and suggest future research.

It is also essential to keep a critical eye when reading scientific articles. In order to be credible, the scientific article must be based on evidence and previous literature. The author’s argument should be well-supported by data and logical reasoning.

How to Write a Research Article Critique

When you are assigned a research article, the first thing you need to do is read the piece carefully. Make sure you understand the subject matter and the author’s chosen approach. Next, you need to assess the importance of the author’s work. What are the key findings, and how do they contribute to the field of research?

Finally, you need to provide a critical point-by-point analysis of the article. This should include discussing the research questions, the main findings, and the overall impression of the scientific piece. In conclusion, you should state whether the text is good or bad. Read more to get an idea about curating a research article critique. But if you are not confident, you can ask “ write my papers ” and hire a professional to craft a critique paper for you. Explore your options online and get high-quality work quickly.

However, test yourself and use the following tips to write a research article critique that is clear, concise, and properly formatted.

- Take notes while you read the text in its entirety. Right down each point you agree and disagree with.

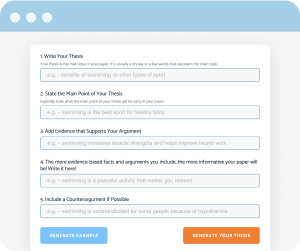

- Write a thesis statement that concisely and clearly outlines the main points.

- Write a paragraph that introduces the article and provides context for the critique.

- Write a paragraph for each of the following points, summarizing the main points and providing your own analysis:

- The purpose of the study

- The research question or questions

- The methods used

- The outcomes

- The conclusions were drawn by the author(s)

- Mention the strengths and weaknesses of the piece in a separate paragraph.

- Write a conclusion that summarizes your thoughts about the article.

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

When writing an article critique, it is important to use research methods to support your arguments. There are a variety of research methods that you can use, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. In this text, we will discuss four of the most common research methods used in article critique writing: quantitative research, qualitative research, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis.

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numbers and statistics to analyze data. This type of research is used to test hypotheses or measure a treatment’s effects. Quantitative research is normally considered more reliable than qualitative research because it considers a large amount of information. But, it might be difficult to find enough data to complete it properly.

Qualitative research is a research method that uses words and interviews to analyze data. This type of research is used to understand people’s thoughts and feelings. Qualitative research is usually more reliable than quantitative research because it is less likely to be biased. Though it is more expensive and tedious.

Systematic reviews are a type of research that uses a set of rules to search for and analyze studies on a particular topic. Some think that systematic reviews are more reliable than other research methods because they use a rigorous process to find and analyze studies. However, they can be pricy and long to carry out.

Meta-analysis is a type of research that combines several studies’ results to understand a treatment’s overall effect better. Meta-analysis is generally considered one of the most reliable type of research because it uses data from several approved studies. Conversely, it involves a long and costly process.

Are you still struggling to understand the critique of an article concept? You can contact an online review writing service to get help from skilled writers. You can get custom, and unique article reviews easily.

Tips for writing an Article Critique

It’s crucial to keep in mind that you’re not just sharing your opinion of the content when you write an article critique. Instead, you are providing a critical analysis, looking at its strengths and weaknesses. In order to write a compelling critique, you should follow these tips: Take note carefully of the essential elements as you read it.

- Make sure that you understand the thesis statement.

- Write down your thoughts, including strengths and weaknesses.

- Use evidence from to support your points.

- Create a clear and concise critique, making sure to avoid giving your opinion.

It is important to be clear and concise when creating an article critique. You should avoid giving your opinion and instead focus on providing a critical analysis. You should also use evidence from the article to support your points.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- All eBooks & Audiobooks

- Academic eBook Collection

- Home Grown eBook Collection

- Off-Campus Access

- Literature Resource Center

- Opposing Viewpoints

- ProQuest Central

- Course Guides

- Citing Sources

- Library Research

- Websites by Topic

- Book-a-Librarian

- Research Tutorials

- Use the Catalog

- Use Databases

- Use Films on Demand

- Use Home Grown eBooks

- Use NC LIVE

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Make an Appointment

- Writing Tools

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing Center

Service Alert

Article Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing an article SUMMARY

- Writing an article REVIEW

Writing an article CRITIQUE

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- About RCC Library

Text: 336-308-8801

Email: [email protected]

Call: 336-633-0204

Schedule: Book-a-Librarian

Like us on Facebook

Links on this guide may go to external web sites not connected with Randolph Community College. Their inclusion is not an endorsement by Randolph Community College and the College is not responsible for the accuracy of their content or the security of their site.

A critique asks you to evaluate an article and the author’s argument. You will need to look critically at what the author is claiming, evaluate the research methods, and look for possible problems with, or applications of, the researcher’s claims.

Introduction

Give an overview of the author’s main points and how the author supports those points. Explain what the author found and describe the process they used to arrive at this conclusion.

Body Paragraphs

Interpret the information from the article:

- Does the author review previous studies? Is current and relevant research used?

- What type of research was used – empirical studies, anecdotal material, or personal observations?

- Was the sample too small to generalize from?

- Was the participant group lacking in diversity (race, gender, age, education, socioeconomic status, etc.)

- For instance, volunteers gathered at a health food store might have different attitudes about nutrition than the population at large.

- How useful does this work seem to you? How does the author suggest the findings could be applied and how do you believe they could be applied?

- How could the study have been improved in your opinion?

- Does the author appear to have any biases (related to gender, race, class, or politics)?

- Is the writing clear and easy to follow? Does the author’s tone add to or detract from the article?

- How useful are the visuals (such as tables, charts, maps, photographs) included, if any? How do they help to illustrate the argument? Are they confusing or hard to read?

- What further research might be conducted on this subject?

Try to synthesize the pieces of your critique to emphasize your own main points about the author’s work, relating the researcher’s work to your own knowledge or to topics being discussed in your course.

From the Center for Academic Excellence (opens in a new window), University of Saint Joseph Connecticut

Additional Resources

All links open in a new window.

Writing an Article Critique (from The University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center)

How to Critique an Article (from Essaypro.com)

How to Write an Article Critique (from EliteEditing.com.au)

- << Previous: Writing an article REVIEW

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://libguides.randolph.edu/summaries

IOE Writing Centre

- Writing a Critical Review

Writing a Critique

A critique (or critical review) is not to be mistaken for a literature review. A 'critical review', or 'critique', is a complete type of text (or genre), discussing one particular article or book in detail. In some instances, you may be asked to write a critique of two or three articles (e.g. a comparative critical review). In contrast, a 'literature review', which also needs to be 'critical', is a part of a larger type of text, such as a chapter of your dissertation.

Most importantly: Read your article / book as many times as possible, as this will make the critical review much easier.

1. Read and take notes 2. Organising your writing 3. Summary 4. Evaluation 5. Linguistic features of a critical review 6. Summary language 7. Evaluation language 8. Conclusion language 9. Example extracts from a critical review 10. Further resources

Read and Take Notes

To improve your reading confidence and efficiency, visit our pages on reading.

Further reading: Read Confidently

After you are familiar with the text, make notes on some of the following questions. Choose the questions which seem suitable:

- What kind of article is it (for example does it present data or does it present purely theoretical arguments)?

- What is the main area under discussion?

- What are the main findings?

- What are the stated limitations?

- Where does the author's data and evidence come from? Are they appropriate / sufficient?

- What are the main issues raised by the author?

- What questions are raised?

- How well are these questions addressed?

- What are the major points/interpretations made by the author in terms of the issues raised?

- Is the text balanced? Is it fair / biased?

- Does the author contradict herself?

- How does all this relate to other literature on this topic?

- How does all this relate to your own experience, ideas and views?

- What else has this author written? Do these build / complement this text?

- (Optional) Has anyone else reviewed this article? What did they say? Do I agree with them?

^ Back to top

Organising your writing

You first need to summarise the text that you have read. One reason to summarise the text is that the reader may not have read the text. In your summary, you will

- focus on points within the article that you think are interesting

- summarise the author(s) main ideas or argument

- explain how these ideas / argument have been constructed. (For example, is the author basing her arguments on data that they have collected? Are the main ideas / argument purely theoretical?)

In your summary you might answer the following questions: Why is this topic important? Where can this text be located? For example, does it address policy studies? What other prominent authors also write about this?

Evaluation is the most important part in a critical review.

Use the literature to support your views. You may also use your knowledge of conducting research, and your own experience. Evaluation can be explicit or implicit.

Explicit evaluation

Explicit evaluation involves stating directly (explicitly) how you intend to evaluate the text. e.g. "I will review this article by focusing on the following questions. First, I will examine the extent to which the authors contribute to current thought on Second Language Acquisition (SLA) pedagogy. After that, I will analyse whether the authors' propositions are feasible within overseas SLA classrooms."

Implicit evaluation

Implicit evaluation is less direct. The following section on Linguistic Features of Writing a Critical Review contains language that evaluates the text. A difficult part of evaluation of a published text (and a professional author) is how to do this as a student. There is nothing wrong with making your position as a student explicit and incorporating it into your evaluation. Examples of how you might do this can be found in the section on Linguistic Features of Writing a Critical Review. You need to remember to locate and analyse the author's argument when you are writing your critical review. For example, you need to locate the authors' view of classroom pedagogy as presented in the book / article and not present a critique of views of classroom pedagogy in general.

Linguistic features of a critical review

The following examples come from published critical reviews. Some of them have been adapted for student use.

Summary language

- This article / book is divided into two / three parts. First...

- While the title might suggest...

- The tone appears to be...

- Title is the first / second volume in the series Title, edited by...The books / articles in this series address...

- The second / third claim is based on...

- The author challenges the notion that...

- The author tries to find a more middle ground / make more modest claims...

- The article / book begins with a short historical overview of...

- Numerous authors have recently suggested that...(see Author, Year; Author, Year). Author would also be once such author. With his / her argument that...

- To refer to title as a...is not to say that it is...

- This book / article is aimed at... This intended readership...

- The author's book / article examines the...To do this, the author first...

- The author develops / suggests a theoretical / pedagogical model to…

- This book / article positions itself firmly within the field of...

- The author in a series of subtle arguments, indicates that he / she...

- The argument is therefore...

- The author asks "..."

- With a purely critical / postmodern take on...

- Topic, as the author points out, can be viewed as...

- In this recent contribution to the field of...this British author...

- As a leading author in the field of...

- This book / article nicely contributes to the field of...and complements other work by this author...

- The second / third part of...provides / questions / asks the reader...

- Title is intended to encourage students / researchers to...

- The approach taken by the author provides the opportunity to examine...in a qualitative / quantitative research framework that nicely complements...

- The author notes / claims that state support / a focus on pedagogy / the adoption of...remains vital if...

- According to Author (Year) teaching towards examinations is not as effective as it is in other areas of the curriculum. This is because, as Author (Year) claims that examinations have undue status within the curriculum.

- According to Author (Year)…is not as effective in some areas of the curriculum / syllabus as others. Therefore the author believes that this is a reason for some school's…

Evaluation language

- This argument is not entirely convincing, as...furthermore it commodifies / rationalises the...

- Over the last five / ten years the view of...has increasingly been viewed as 'complicated' (see Author, Year; Author, Year).

- However, through trying to integrate...with...the author...

- There are difficulties with such a position.

- Inevitably, several crucial questions are left unanswered / glossed over by this insightful / timely / interesting / stimulating book / article. Why should...

- It might have been more relevant for the author to have written this book / article as...

- This article / book is not without disappointment from those who would view...as...

- This chosen framework enlightens / clouds...

- This analysis intends to be...but falls a little short as...

- The authors rightly conclude that if...

- A detailed, well-written and rigorous account of...

- As a Korean student I feel that this article / book very clearly illustrates...

- The beginning of...provides an informative overview into...

- The tables / figures do little to help / greatly help the reader...

- The reaction by scholars who take a...approach might not be so favourable (e.g. Author, Year).

- This explanation has a few weaknesses that other researchers have pointed out (see Author, Year; Author, Year). The first is...

- On the other hand, the author wisely suggests / proposes that...By combining these two dimensions...

- The author's brief introduction to...may leave the intended reader confused as it fails to properly...

- Despite my inability to...I was greatly interested in...

- Even where this reader / I disagree(s), the author's effort to...

- The author thus combines...with...to argue...which seems quite improbable for a number of reasons. First...

- Perhaps this aversion to...would explain the author's reluctance to...

- As a second language student from ...I find it slightly ironic that such an anglo-centric view is...

- The reader is rewarded with...

- Less convincing is the broad-sweeping generalisation that...

- There is no denying the author's subject knowledge nor his / her...

- The author's prose is dense and littered with unnecessary jargon...

- The author's critique of...might seem harsh but is well supported within the literature (see Author, Year; Author, Year; Author, Year). Aligning herself with the author, Author (Year) states that...

- As it stands, the central focus of Title is well / poorly supported by its empirical findings...

- Given the hesitation to generalise to...the limitation of...does not seem problematic...

- For instance, the term...is never properly defined and the reader left to guess as to whether...

- Furthermore, to label...as...inadvertently misguides...

- In addition, this research proves to be timely / especially significant to... as recent government policy / proposals has / have been enacted to...

- On this well researched / documented basis the author emphasises / proposes that...

- Nonetheless, other research / scholarship / data tend to counter / contradict this possible trend / assumption...(see Author, Year; Author, Year).

- Without entering into detail of the..., it should be stated that Title should be read by...others will see little value in...

- As experimental conditions were not used in the study the word 'significant' misleads the reader.

- The article / book becomes repetitious in its assertion that...

- The thread of the author's argument becomes lost in an overuse of empirical data...

- Almost every argument presented in the final section is largely derivative, providing little to say about...

- She / he does not seem to take into consideration; however, that there are fundamental differences in the conditions of…

- As Author (Year) points out, however, it seems to be necessary to look at…

- This suggest that having low…does not necessarily indicate that…is ineffective.

- Therefore, the suggestion made by Author (Year)…is difficult to support.

- When considering all the data presented…it is not clear that the low scores of some students, indeed, reflects…

Conclusion language

- Overall this article / book is an analytical look at...which within the field of...is often overlooked.

- Despite its problems, Title offers valuable theoretical insights / interesting examples / a contribution to pedagogy and a starting point for students / researchers of...with an interest in...

- This detailed and rigorously argued...

- This first / second volume / book / article by...with an interest in...is highly informative...

Example extracts from a critical review

Writing critically.

If you have been told your writing is not critical enough, it probably means that your writing treats the knowledge claims as if they are true, well supported, and applicable in the context you are writing about. This may not always be the case.

In these two examples, the extracts refer to the same section of text. In each example, the section that refers to a source has been highlighted in bold. The note below the example then explains how the writer has used the source material.

There is a strong positive effect on students, both educationally and emotionally, when the instructors try to learn to say students' names without making pronunciation errors (Kiang, 2004).

Use of source material in example a:

This is a simple paraphrase with no critical comment. It looks like the writer agrees with Kiang. (This is not a good example for critical writing, as the writer has not made any critical comment).

Kiang (2004) gives various examples to support his claim that "the positive emotional and educational impact on students is clear" (p.210) when instructors try to pronounce students' names in the correct way. He quotes one student, Nguyet, as saying that he "felt surprised and happy" (p.211) when the tutor said his name clearly . The emotional effect claimed by Kiang is illustrated in quotes such as these, although the educational impact is supported more indirectly through the chapter. Overall, he provides more examples of students being negatively affected by incorrect pronunciation, and it is difficult to find examples within the text of a positive educational impact as such.

Use of source material in example b:

The writer describes Kiang's (2004) claim and the examples which he uses to try to support it. The writer then comments that the examples do not seem balanced and may not be enough to support the claims fully. This is a better example of writing which expresses criticality.

^Back to top

Further resources

You may also be interested in our page on criticality, which covers criticality in general, and includes more critical reading questions.

Further reading: Read and Write Critically

We recommend that you do not search for other university guidelines on critical reviews. This is because the expectations may be different at other institutions. Ask your tutor for more guidance or examples if you have further questions.

IOE Writing Centre Online

Self-access resources from the Academic Writing Centre at the UCL Institute of Education.

Anonymous Suggestions Box

Information for Staff

Academic Writing Centre

Academic Writing Centre, UCL Institute of Education [email protected] Twitter: @AWC_IOE Skype: awc.ioe

Writing Critiques

Writing a critique involves more than pointing out mistakes. It involves conducting a systematic analysis of a scholarly article or book and then writing a fair and reasonable description of its strengths and weaknesses. Several scholarly journals have published guides for critiquing other people’s work in their academic area. Search for a “manuscript reviewer guide” in your own discipline to guide your analysis of the content. Use this handout as an orientation to the audience and purpose of different types of critiques and to the linguistic strategies appropriate to all of them.

Types of critique

Article or book review assignment in an academic class.

Text: Article or book that has already been published Audience: Professors Purpose:

- to demonstrate your skills for close reading and analysis

- to show that you understand key concepts in your field

- to learn how to review a manuscript for your future professional work

Published book review

Text: Book that has already been published Audience: Disciplinary colleagues Purpose:

- to describe the book’s contents

- to summarize the book’s strengths and weaknesses

- to provide a reliable recommendation to read (or not read) the book

Manuscript review

Text: Manuscript that has been submitted but has not been published yet Audience: Journal editor and manuscript authors Purpose:

- to provide the editor with an evaluation of the manuscript

- to recommend to the editor that the article be published, revised, or rejected

- to provide the authors with constructive feedback and reasonable suggestions for revision

Language strategies for critiquing

For each type of critique, it’s important to state your praise, criticism, and suggestions politely, but with the appropriate level of strength. The following language structures should help you achieve this challenging task.

Offering Praise and Criticism

A strategy called “hedging” will help you express praise or criticism with varying levels of strength. It will also help you express varying levels of certainty in your own assertions. Grammatical structures used for hedging include:

Modal verbs Using modal verbs (could, can, may, might, etc.) allows you to soften an absolute statement. Compare:

This text is inappropriate for graduate students who are new to the field. This text may be inappropriate for graduate students who are new to the field.

Qualifying adjectives and adverbs Using qualifying adjectives and adverbs (possible, likely, possibly, somewhat, etc.) allows you to introduce a level of probability into your comments. Compare:

Readers will find the theoretical model difficult to understand. Some readers will find the theoretical model difficult to understand. Some readers will probably find the theoretical model somewhat difficult to understand completely.

Note: You can see from the last example that too many qualifiers makes the idea sound undesirably weak.

Tentative verbs Using tentative verbs (seems, indicates, suggests, etc.) also allows you to soften an absolute statement. Compare:

This omission shows that the authors are not aware of the current literature. This omission indicates that the authors are not aware of the current literature. This omission seems to suggest that the authors are not aware of the current literature.

Offering suggestions

Whether you are critiquing a published or unpublished text, you are expected to point out problems and suggest solutions. If you are critiquing an unpublished manuscript, the author can use your suggestions to revise. Your suggestions have the potential to become real actions. If you are critiquing a published text, the author cannot revise, so your suggestions are purely hypothetical. These two situations require slightly different grammar.

Unpublished manuscripts: “would be X if they did Y” Reviewers commonly point out weakness by pointing toward improvement. For instance, if the problem is “unclear methodology,” reviewers may write that “the methodology would be more clear if …” plus a suggestion. If the author can use the suggestions to revise, the grammar is “X would be better if the authors did Y” (would be + simple past suggestion).

The tables would be clearer if the authors highlighted the key results. The discussion would be more persuasive if the authors accounted for the discrepancies in the data.

Published manuscripts: “would have been X if they had done Y” If the authors cannot revise based on your suggestions, use the past unreal conditional form “X would have been better if the authors had done Y” (would have been + past perfect suggestion).

The tables would have been clearer if the authors had highlighted key results. The discussion would have been more persuasive if the authors had accounted for discrepancies in the data.

Note: For more information on conditional structures, see our Conditionals handout .

Make a Gift

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write an Article Critique

Tips for Writing a Psychology Critique Paper

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Cultura RM / Gu Cultura / Getty Images

- Steps for Writing a Critique

Evaluating the Article

- How to Write It

- Helpful Tips

An article critique involves critically analyzing a written work to assess its strengths and flaws. If you need to write an article critique, you will need to describe the article, analyze its contents, interpret its meaning, and make an overall assessment of the importance of the work.

Critique papers require students to conduct a critical analysis of another piece of writing, often a book, journal article, or essay . No matter your major, you will probably be expected to write a critique paper at some point.

For psychology students, critiquing a professional paper is a great way to learn more about psychology articles, writing, and the research process itself. Students will analyze how researchers conduct experiments, interpret results, and discuss the impact of the results.

At a Glance

An article critique involves making a critical assessment of a single work. This is often an article, but it might also be a book or other written source. It summarizes the contents of the article and then evaluates both the strengths and weaknesses of the piece. Knowing how to write an article critique can help you learn how to evaluate sources with a discerning eye.

Steps for Writing an Effective Article Critique

While these tips are designed to help students write a psychology critique paper, many of the same principles apply to writing article critiques in other subject areas.

Your first step should always be a thorough read-through of the material you will be analyzing and critiquing. It needs to be more than just a casual skim read. It should be in-depth with an eye toward key elements.

To write an article critique, you should:

- Read the article , noting your first impressions, questions, thoughts, and observations

- Describe the contents of the article in your own words, focusing on the main themes or ideas

- Interpret the meaning of the article and its overall importance

- Critically evaluate the contents of the article, including any strong points as well as potential weaknesses

The following guidelines can help you assess the article you are reading and make better sense of the material.

Read the Introduction Section of the Article

Start by reading the introduction . Think about how this part of the article sets up the main body and how it helps you get a background on the topic.

- Is the hypothesis clearly stated?

- Is the necessary background information and previous research described in the introduction?

In addition to answering these basic questions, note other information provided in the introduction and any questions you have.

Read the Methods Section of the Article

Is the study procedure clearly outlined in the methods section ? Can you determine which variables the researchers are measuring?

Remember to jot down questions and thoughts that come to mind as you are reading. Once you have finished reading the paper, you can then refer back to your initial questions and see which ones remain unanswered.

Read the Results Section of the Article

Are all tables and graphs clearly labeled in the results section ? Do researchers provide enough statistical information? Did the researchers collect all of the data needed to measure the variables in question?

Make a note of any questions or information that does not seem to make sense. You can refer back to these questions later as you are writing your final critique.

Read the Discussion Section of the Article

Experts suggest that it is helpful to take notes while reading through sections of the paper you are evaluating. Ask yourself key questions:

- How do the researchers interpret the results of the study?

- Did the results support their hypothesis?

- Do the conclusions drawn by the researchers seem reasonable?

The discussion section offers students an excellent opportunity to take a position. If you agree with the researcher's conclusions, explain why. If you feel the researchers are incorrect or off-base, point out problems with the conclusions and suggest alternative explanations.

Another alternative is to point out questions the researchers failed to answer in the discussion section.

Begin Writing Your Own Critique of the Paper

Once you have read the article, compile your notes and develop an outline that you can follow as you write your psychology critique paper. Here's a guide that will walk you through how to structure your critique paper.

Introduction

Begin your paper by describing the journal article and authors you are critiquing. Provide the main hypothesis (or thesis) of the paper. Explain why you think the information is relevant.

Thesis Statement

The final part of your introduction should include your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the main idea of your critique. Your thesis should briefly sum up the main points of your critique.

Article Summary

Provide a brief summary of the article. Outline the main points, results, and discussion.

When describing the study or paper, experts suggest that you include a summary of the questions being addressed, study participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design.

Don't get bogged down by your summary. This section should highlight the main points of the article you are critiquing. Don't feel obligated to summarize each little detail of the main paper. Focus on giving the reader an overall idea of the article's content.

Your Analysis

In this section, you will provide your critique of the article. Describe any problems you had with the author's premise, methods, or conclusions. You might focus your critique on problems with the author's argument, presentation, information, and alternatives that have been overlooked.

When evaluating a study, summarize the main findings—including the strength of evidence for each main outcome—and consider their relevance to key demographic groups.

Organize your paper carefully. Be careful not to jump around from one argument to the next. Arguing one point at a time ensures that your paper flows well and is easy to read.

Your critique paper should end with an overview of the article's argument, your conclusions, and your reactions.

More Tips When Writing an Article Critique

- As you are editing your paper, utilize a style guide published by the American Psychological Association, such as the official Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association .

- Reading scientific articles can be challenging at first. Remember that this is a skill that takes time to learn but that your skills will become stronger the more that you read.

- Take a rough draft of your paper to your school's writing lab for additional feedback and use your university library's resources.

What This Means For You

Being able to write a solid article critique is a useful academic skill. While it can be challenging, start by breaking down the sections of the paper, noting your initial thoughts and questions. Then structure your own critique so that you present a summary followed by your evaluation. In your critique, include the strengths and the weaknesses of the article.

Archibald D, Martimianakis MA. Writing, reading, and critiquing reviews . Can Med Educ J . 2021;12(3):1-7. doi:10.36834/cmej.72945

Pautasso M. Ten simple rules for writing a literature review . PLoS Comput Biol . 2013;9(7):e1003149. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

Gülpınar Ö, Güçlü AG. How to write a review article? Turk J Urol . 2013;39(Suppl 1):44–48. doi:10.5152/tud.2013.054

Erol A. Basics of writing review articles . Noro Psikiyatr Ars . 2022;59(1):1-2. doi:10.29399/npa.28093

American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). Washington DC: The American Psychological Association; 2019.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

The Tech Edvocate

- Advertisement

- Home Page Five (No Sidebar)

- Home Page Four

- Home Page Three

- Home Page Two

- Icons [No Sidebar]

- Left Sidbear Page

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- My Speaking Page

- Newsletter Sign Up Confirmation

- Newsletter Unsubscription

- Page Example

- Privacy Policy

- Protected Content

- Request a Product Review

- Shortcodes Examples

- Terms and Conditions

- The Edvocate

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- Write For Us

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Assistive Technology

- Child Development Tech

- Early Childhood & K-12 EdTech

- EdTech Futures

- EdTech News

- EdTech Policy & Reform

- EdTech Startups & Businesses

- Higher Education EdTech

- Online Learning & eLearning

- Parent & Family Tech

- Personalized Learning

- Product Reviews

- Tech Edvocate Awards

- School Ratings

Product Review of the Tribit XSound Plus 2

Teaching reading to struggling students: everything you need to know, rhyming capacity: everything you need to know, phonological awareness: everything you need to know, product review of kate spade’s bloom: the perfect mother’s day gift, learning to read: everything you need to know, product review of the arzopa z1c portable monitor, how to teach phonics: everything you need to know, reading groups: everything you need to know, product review of the ultenic p30 grooming kit, how to write an article review (with sample reviews) .

An article review is a critical evaluation of a scholarly or scientific piece, which aims to summarize its main ideas, assess its contributions, and provide constructive feedback. A well-written review not only benefits the author of the article under scrutiny but also serves as a valuable resource for fellow researchers and scholars. Follow these steps to create an effective and informative article review:

1. Understand the purpose: Before diving into the article, it is important to understand the intent of writing a review. This helps in focusing your thoughts, directing your analysis, and ensuring your review adds value to the academic community.

2. Read the article thoroughly: Carefully read the article multiple times to get a complete understanding of its content, arguments, and conclusions. As you read, take notes on key points, supporting evidence, and any areas that require further exploration or clarification.

3. Summarize the main ideas: In your review’s introduction, briefly outline the primary themes and arguments presented by the author(s). Keep it concise but sufficiently informative so that readers can quickly grasp the essence of the article.

4. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses: In subsequent paragraphs, assess the strengths and limitations of the article based on factors such as methodology, quality of evidence presented, coherence of arguments, and alignment with existing literature in the field. Be fair and objective while providing your critique.

5. Discuss any implications: Deliberate on how this particular piece contributes to or challenges existing knowledge in its discipline. You may also discuss potential improvements for future research or explore real-world applications stemming from this study.

6. Provide recommendations: Finally, offer suggestions for both the author(s) and readers regarding how they can further build on this work or apply its findings in practice.

7. Proofread and revise: Once your initial draft is complete, go through it carefully for clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Revise as necessary, ensuring your review is both informative and engaging for readers.

Sample Review:

A Critical Review of “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health”

Introduction:

“The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is a timely article which investigates the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being. The authors present compelling evidence to support their argument that excessive use of social media can result in decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety, and a negative impact on interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and weaknesses:

One of the strengths of this article lies in its well-structured methodology utilizing a variety of sources, including quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the topic, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of social media on mental health. However, it would have been beneficial if the authors included a larger sample size to increase the reliability of their conclusions. Additionally, exploring how different platforms may influence mental health differently could have added depth to the analysis.

Implications:

The findings in this article contribute significantly to ongoing debates surrounding the psychological implications of social media use. It highlights the potential dangers that excessive engagement with online platforms may pose to one’s mental well-being and encourages further research into interventions that could mitigate these risks. The study also offers an opportunity for educators and policy-makers to take note and develop strategies to foster healthier online behavior.

Recommendations:

Future researchers should consider investigating how specific social media platforms impact mental health outcomes, as this could lead to more targeted interventions. For practitioners, implementing educational programs aimed at promoting healthy online habits may be beneficial in mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with excessive social media use.

Conclusion:

Overall, “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is an important and informative piece that raises awareness about a pressing issue in today’s digital age. Given its minor limitations, it provides valuable

3 Ways to Make a Mini Greenhouse ...

3 ways to teach yourself to play ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

5 Ways to Name a Stuffed Animal or Toy

How to Restrain a Dog: 7 Steps

3 Ways to Get a Tracking Number

3 Ways to Create a Perfect Circle Without Tracing

How to Talk Nicely: 11 Steps

5 Ways to Apply for a Grant

How to Write an Effective Article Review – Updated 2024 Guide

Purpose of an Article Review

Importance of writing an effective review, read the article thoroughly, identify the main arguments, take notes on key points.

- Evaluate the Author's Credibility

- Assess the Article's Structure and Organization

Examine the Use of Evidence and Examples

Write a concise summary of the article.

- Include the Article's Main Points

Avoid Personal Opinions in the Summary

Identify strengths and weaknesses.

- Evaluate the Article's Logic and Reasoning

- Discuss the Article's Impact and Relevance

Start with an Engaging Introduction

Provide a brief overview of the article.

- Critique the Article's Strengths and Weaknesses

Offer Suggestions for Improvement

Conclude with a summary and recommendation, check for grammar and spelling errors, ensure clarity and coherence of writing, revise for proper formatting and citations, review the overall structure and flow, make final edits and revisions, submit the article review.

Writing an article review can be a challenging task, but it is an essential skill for academics, researchers, and anyone who needs to critically evaluate published work. An article review is a written piece that provides a comprehensive analysis and evaluation of a scholarly article, book, or other published material. It goes beyond a simple summary by offering a critical assessment of the work’s strengths, weaknesses, and overall contribution to the field. In this blog post, we will explore the steps involved in writing an effective article review.

I. Introduction

The primary purpose of an article review is to provide a critical evaluation of a published work. It serves as a means of engaging with the ideas and arguments presented by the author(s) and assessing their validity, significance, and potential impact on the field. An article review allows the reviewer to analyze the work’s merits, identify its limitations, and offer constructive feedback or suggestions for further research or discussion.

Writing an effective article review is crucial for several reasons. First, it demonstrates the reviewer’s ability to critically analyze and synthesize complex information. This skill is highly valued in academic and professional settings, where critical thinking and analytical skills are essential . Second, article reviews contribute to the ongoing scholarly discourse by providing informed perspectives and critiques that can shape future research and discussions. Finally, well-written article reviews can help readers determine whether a particular work is worth reading or exploring further, making them valuable resources for researchers and scholars in the field.

II. Understanding the Article

The first step in writing an article review is to read the article carefully and thoroughly. This may seem obvious, but it is crucial to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the work before attempting to critique it. During the initial reading, focus on grasping the main arguments, key points, and the overall structure of the article. Take note of any unfamiliar concepts, terminology, or references that may require further research or clarification.

As you read the article, pay close attention to the author’s central arguments or thesis statements. Identify the main claims, hypotheses, or research questions that the article attempts to address. Understanding the core arguments is essential for evaluating the effectiveness of the author’s reasoning and the validity of their conclusions.

While reading the article, it is helpful to take notes on the key points, supporting evidence, and any critical or thought-provoking ideas presented by the author(s). These notes will serve as a reference when you begin writing the review and will help you organize your thoughts and critique more effectively.

III. Analyzing the Article

Evaluate the author’s credibility.

When analyzing an article, it is essential to consider the author’s credibility and expertise in the field. Research the author’s background, qualifications, and previous publications to assess their authority on the subject matter. This information can provide valuable context and help you determine the weight and reliability of the arguments presented in the article.

Assess the Article’s Structure and Organization

Evaluate the overall structure and organization of the article. Is the information presented in a logical and coherent manner? Does the article follow a clear progression from introduction to conclusion? Assessing the structure can help you determine whether the author has effectively communicated their ideas and arguments.

Critically examine the evidence and examples used by the author(s) to support their arguments. Are the sources credible and up-to-date? Are the examples relevant and well-chosen? Evaluating the quality and appropriateness of the evidence can help you assess the strength and validity of the author’s claims.

IV. Summarizing the Article

Before delving into your critique, it is essential to provide a concise summary of the article . This summary should briefly outline the article’s main arguments, key points, and conclusions. The goal is to give the reader a clear understanding of the article’s content without adding any personal opinions or critiques at this stage.

Include the Article’s Main Points

In your summary, be sure to include the article’s main points and the evidence or examples used to support them. This will help the reader understand the context and the basis for the author’s arguments, which is crucial for your subsequent critique.

When summarizing the article, it is important to remain objective and avoid injecting personal opinions or critiques. The summary should be a neutral representation of the article’s content, leaving the analysis and evaluation for the critique section.

V. Critiquing the Article

After providing a summary, it is time to analyze and critique the article. Begin by identifying the article’s strengths and weaknesses . Strengths may include well-reasoned arguments, thorough research, innovative ideas, or significant contributions to the field. Weaknesses could include flawed logic, lack of evidence, oversimplification of complex issues, or failure to address counterarguments.

Evaluate the Article’s Logic and Reasoning

Carefully evaluate the author’s logic and reasoning throughout the article. Are the arguments well-supported and logically consistent? Do the conclusions follow naturally from the evidence presented? Identify any logical fallacies, contradictions, or gaps in reasoning that may undermine the author’s arguments.

Discuss the Article’s Impact and Relevance

Consider the article’s potential impact and relevance within the broader context of the field. How does it contribute to existing knowledge or challenge prevailing theories? Does it open up new avenues for research or discussion? Discussing the article’s impact and relevance can help readers understand its significance and importance.

VI. Writing the Article Review

Begin your article review with an engaging introduction that captures the reader’s attention and provides context for the review. Briefly introduce the article, its author(s), and the main topic or research area. You can also include a concise thesis statement that summarizes your overall evaluation or critique of the article.

After the introduction, provide a brief overview or summary of the article. This should be a condensed version of the summary you wrote earlier, highlighting the article’s main arguments, key points, and conclusions. Keep this section concise and focused, as the main critique will follow.

Critique the Article’s Strengths and Weaknesses

In the critique section, present your analysis of the article’s strengths and weaknesses. Discuss the author’s use of evidence, the validity of their arguments, and the overall quality of their reasoning. Support your critique with specific examples and references from the article. Be sure to provide balanced criticism, acknowledging both the positive and negative aspects of the work.

In addition to critiquing the article , consider offering constructive suggestions for improvement. These suggestions could address areas where the author’s arguments were weak or where additional research or discussion is needed. Your suggestions should be specific and actionable, aimed at enhancing the quality and impact of the work.

Conclude your article review by summarizing your main points and providing an overall recommendation or final assessment of the article. This recommendation could be to read or not read the article, to use it as a reference in a specific context, or to consider it as a starting point for further research or discussion.

VII. Editing and Proofreading

After you have completed your initial draft, it is essential to carefully proofread and edit your work. Check for any grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, or typos that may have been overlooked during the writing process. These small errors can detract from the overall quality and professionalism of your review.

In addition to checking for mechanical errors , ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and coherent. Review your sentences and paragraphs for clarity, and make sure that your ideas flow logically from one point to the next. Avoid ambiguous or confusing language that could make your critique difficult to understand.

Depending on the specific requirements or guidelines for your article review, you may need to revise your work to ensure proper formatting and citation styles. Check that you have correctly cited any references or quotes from the article you are reviewing, and that your formatting (e.g., headings, spacing, font) adheres to the specified guidelines.

VIII. Finalizing the Review

Before finalizing your article review , take a step back and review the overall structure and flow of your writing. Ensure that your introduction effectively sets the stage for your critique, and that your body paragraphs logically build upon one another, leading to a well-supported conclusion.

During this final review, consider whether your critique is balanced and objective, presenting both the strengths and weaknesses of the article in a fair and impartial manner. Also, check that you have provided sufficient evidence and examples to support your analysis and that your arguments are clearly articulated.

After reviewing the overall structure and flow, make any necessary final edits and revisions to your article review. This might involve reorganizing or reworking certain sections for better clarity, strengthening your arguments with additional evidence, or refining your writing style for greater impact.

Pay close attention to your choice of words and tone, ensuring that your critique remains respectful and professional, even when addressing the article’s shortcomings. Remember, the goal is to provide a constructive and well-reasoned analysis, not to disparage or attack the author’s work.

Once you are satisfied with your article review, it is time to submit it according to the appropriate guidelines or requirements . This might involve formatting your work in a specific style, adhering to word count or page limits, or following specific submission procedures.

If your article review is intended for publication, be sure to follow the guidelines provided by the journal or publication outlet. This may include submitting your work through an online portal, adhering to specific formatting requirements, or including additional materials such as an abstract or author biography.

Congratulations! By following these steps, you have successfully written a comprehensive and effective article review. Remember, the process of critically evaluating published work is an essential skill that not only demonstrates your ability to analyze and synthesize complex information but also contributes to the ongoing scholarly discourse within your field.

Writing an article review can be a challenging task, but it is a valuable exercise that sharpens your critical thinking, analytical, and communication skills. By carefully reading and understanding the article, assessing its strengths and weaknesses, and providing a well-reasoned critique, you contribute to the advancement of knowledge and foster a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

So, embrace the opportunity to write article reviews, and use each one as a platform to engage with the ideas and arguments presented by scholars and researchers. Your thoughtful and insightful critiques can shape future research, inspire new perspectives, and ultimately drive progress within your field of study.

- RESEARCH PAPER FOR SALE

- RESEARCH PAPER WRITER

- RESEARCH PROPOSAL WRITING SERVICES

- SCHOLARSHIP ESSAY HELP

- SPEECH HELP

- STATISTICS HOMEWORK HELP

- TERM PAPER WRITING HELP

- THESIS EDITING SERVICES

- THESIS PROPOSAL WRITING SERVICE

- TRIGONOMETRY HOMEWORK HELP

- ADMISSION ESSAY WRITING HELP

- BIOLOGY PAPER WRITING SERVICE

- BOOK REPORT WRITING HELP

- BUY BOOK REVIEW

- BUY COURSEWORKS

- BUY DISCUSSION POST

- BUY TERM PAPER

- CAPSTONE PROJECT WRITING SERVICE

- COURSEWORK WRITING SERVICE

- CRITIQUE MY ESSAY

- CUSTOM RESEARCH PAPER

- CUSTOMER CONDUCT

- DISSERTATION EDITING SERVICE

- DISSERTATION WRITERS

- DO MY DISSERTATION FOR ME

- DO MY POWERPOINT PRESENTATION

- EDIT MY PAPER

- English Research Paper Writing Service

- ENGLISH RESEARCH PAPER WRITING SERVICE

- ESSAY WRITING HELP

- ESSAYS FOR SALE

- GRADUATE PAPER WRITING SERVICE

- LAW ASSIGNMENT WRITING HELP

- MARKETING ASSIGNMENT WRITING HELP

- NON-PLAGIARIZED ESSAYS

- NURSING ASSIGNMENT HELP

- PAY FOR COURSEWORK

- PAY FOR ESSAYS

- PAY FOR LITERATURE REVIEW

- PAY FOR PAPERS

- PAY FOR RESEARCH PAPERS

- PERSONAL STATEMENT EDITING SERVICE

- PERSONAL STATEMENT WRITER

- PERSUASIVE ESSAY WRITING HELP

- PERSUASIVE ESSAY WRITING SERVICES

- PHD THESIS WRITING SERVICE

- PROOFREAD MY PAPER

- PSYCHOLOGY ESSAY WRITING SERVICES

- THESIS STATEMENT HELP

- WRITE MY ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR ME

- WRITE MY CASE STUDY

- WRITE MY DISCUSSION BOARD POST

- WRITE MY LAB REPORT

How to Write an Article Review: Tips and Examples

Did you know that article reviews are not just academic exercises but also a valuable skill in today's information age? In a world inundated with content, being able to dissect and evaluate articles critically can help you separate the wheat from the chaff. Whether you're a student aiming to excel in your coursework or a professional looking to stay well-informed, mastering the art of writing article reviews is an invaluable skill.

Short Description

In this article, our research paper writing service experts will start by unraveling the concept of article reviews and discussing the various types. You'll also gain insights into the art of formatting your review effectively. To ensure you're well-prepared, we'll take you through the pre-writing process, offering tips on setting the stage for your review. But it doesn't stop there. You'll find a practical example of an article review to help you grasp the concepts in action. To complete your journey, we'll guide you through the post-writing process, equipping you with essential proofreading techniques to ensure your work shines with clarity and precision!

What Is an Article Review: Grasping the Concept

A review article is a type of professional paper writing that demands a high level of in-depth analysis and a well-structured presentation of arguments. It is a critical, constructive evaluation of literature in a particular field through summary, classification, analysis, and comparison.

If you write a scientific review, you have to use database searches to portray the research. Your primary goal is to summarize everything and present a clear understanding of the topic you've been working on.

Writing Involves:

- Summarization, classification, analysis, critiques, and comparison.

- The analysis, evaluation, and comparison require the use of theories, ideas, and research relevant to the subject area of the article.

- It is also worth nothing if a review does not introduce new information, but instead presents a response to another writer's work.

- Check out other samples to gain a better understanding of how to review the article.

Types of Review

When it comes to article reviews, there's more than one way to approach the task. Understanding the various types of reviews is like having a versatile toolkit at your disposal. In this section, we'll walk you through the different dimensions of review types, each offering a unique perspective and purpose. Whether you're dissecting a scholarly article, critiquing a piece of literature, or evaluating a product, you'll discover the diverse landscape of article reviews and how to navigate it effectively.

.webp)

Journal Article Review

Just like other types of reviews, a journal article review assesses the merits and shortcomings of a published work. To illustrate, consider a review of an academic paper on climate change, where the writer meticulously analyzes and interprets the article's significance within the context of environmental science.

Research Article Review

Distinguished by its focus on research methodologies, a research article review scrutinizes the techniques used in a study and evaluates them in light of the subsequent analysis and critique. For instance, when reviewing a research article on the effects of a new drug, the reviewer would delve into the methods employed to gather data and assess their reliability.

Science Article Review

In the realm of scientific literature, a science article review encompasses a wide array of subjects. Scientific publications often provide extensive background information, which can be instrumental in conducting a comprehensive analysis. For example, when reviewing an article about the latest breakthroughs in genetics, the reviewer may draw upon the background knowledge provided to facilitate a more in-depth evaluation of the publication.

Need a Hand From Professionals?

Address to Our Writers and Get Assistance in Any Questions!

Formatting an Article Review

The format of the article should always adhere to the citation style required by your professor. If you're not sure, seek clarification on the preferred format and ask him to clarify several other pointers to complete the formatting of an article review adequately.

How Many Publications Should You Review?

- In what format should you cite your articles (MLA, APA, ASA, Chicago, etc.)?

- What length should your review be?

- Should you include a summary, critique, or personal opinion in your assignment?

- Do you need to call attention to a theme or central idea within the articles?

- Does your instructor require background information?

When you know the answers to these questions, you may start writing your assignment. Below are examples of MLA and APA formats, as those are the two most common citation styles.

Using the APA Format

Articles appear most commonly in academic journals, newspapers, and websites. If you write an article review in the APA format, you will need to write bibliographical entries for the sources you use:

- Web : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Title. Retrieved from {link}

- Journal : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Publication Year). Publication Title. Periodical Title, Volume(Issue), pp.-pp.

- Newspaper : Author [last name], A.A [first and middle initial]. (Year, Month, Date of Publication). Publication Title. Magazine Title, pp. xx-xx.

Using MLA Format

- Web : Last, First Middle Initial. “Publication Title.” Website Title. Website Publisher, Date Month Year Published. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

- Newspaper : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Newspaper Title [City] Date, Month, Year Published: Page(s). Print.

- Journal : Last, First M. “Publication Title.” Journal Title Series Volume. Issue (Year Published): Page(s). Database Name. Web. Date Month Year Accessed.

Enhance your writing effortlessly with EssayPro.com , where you can order an article review or any other writing task. Our team of expert writers specializes in various fields, ensuring your work is not just summarized, but deeply analyzed and professionally presented. Ideal for students and professionals alike, EssayPro offers top-notch writing assistance tailored to your needs. Elevate your writing today with our skilled team at your article review writing service !

.jpg)

The Pre-Writing Process

Facing this task for the first time can really get confusing and can leave you unsure of where to begin. To create a top-notch article review, start with a few preparatory steps. Here are the two main stages from our dissertation services to get you started:

Step 1: Define the right organization for your review. Knowing the future setup of your paper will help you define how you should read the article. Here are the steps to follow:

- Summarize the article — seek out the main points, ideas, claims, and general information presented in the article.

- Define the positive points — identify the strong aspects, ideas, and insightful observations the author has made.

- Find the gaps —- determine whether or not the author has any contradictions, gaps, or inconsistencies in the article and evaluate whether or not he or she used a sufficient amount of arguments and information to support his or her ideas.

- Identify unanswered questions — finally, identify if there are any questions left unanswered after reading the piece.

Step 2: Move on and review the article. Here is a small and simple guide to help you do it right:

- Start off by looking at and assessing the title of the piece, its abstract, introductory part, headings and subheadings, opening sentences in its paragraphs, and its conclusion.

- First, read only the beginning and the ending of the piece (introduction and conclusion). These are the parts where authors include all of their key arguments and points. Therefore, if you start with reading these parts, it will give you a good sense of the author's main points.

- Finally, read the article fully.

These three steps make up most of the prewriting process. After you are done with them, you can move on to writing your own review—and we are going to guide you through the writing process as well.

Outline and Template

As you progress with reading your article, organize your thoughts into coherent sections in an outline. As you read, jot down important facts, contributions, or contradictions. Identify the shortcomings and strengths of your publication. Begin to map your outline accordingly.

If your professor does not want a summary section or a personal critique section, then you must alleviate those parts from your writing. Much like other assignments, an article review must contain an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Thus, you might consider dividing your outline according to these sections as well as subheadings within the body. If you find yourself troubled with the pre-writing and the brainstorming process for this assignment, seek out a sample outline.

Your custom essay must contain these constituent parts:

- Pre-Title Page - Before diving into your review, start with essential details: article type, publication title, and author names with affiliations (position, department, institution, location, and email). Include corresponding author info if needed.

- Running Head - In APA format, use a concise title (under 40 characters) to ensure consistent formatting.

- Summary Page - Optional but useful. Summarize the article in 800 words, covering background, purpose, results, and methodology, avoiding verbatim text or references.

- Title Page - Include the full title, a 250-word abstract, and 4-6 keywords for discoverability.

- Introduction - Set the stage with an engaging overview of the article.

- Body - Organize your analysis with headings and subheadings.

- Works Cited/References - Properly cite all sources used in your review.

- Optional Suggested Reading Page - If permitted, suggest further readings for in-depth exploration.

- Tables and Figure Legends (if instructed by the professor) - Include visuals when requested by your professor for clarity.

Example of an Article Review

You might wonder why we've dedicated a section of this article to discuss an article review sample. Not everyone may realize it, but examining multiple well-constructed examples of review articles is a crucial step in the writing process. In the following section, our essay writing service experts will explain why.

Looking through relevant article review examples can be beneficial for you in the following ways:

- To get you introduced to the key works of experts in your field.

- To help you identify the key people engaged in a particular field of science.

- To help you define what significant discoveries and advances were made in your field.

- To help you unveil the major gaps within the existing knowledge of your field—which contributes to finding fresh solutions.

- To help you find solid references and arguments for your own review.

- To help you generate some ideas about any further field of research.

- To help you gain a better understanding of the area and become an expert in this specific field.

- To get a clear idea of how to write a good review.

View Our Writer’s Sample Before Crafting Your Own!

Why Have There Been No Great Female Artists?

Steps for Writing an Article Review

Here is a guide with critique paper format on how to write a review paper:

.webp)

Step 1: Write the Title

First of all, you need to write a title that reflects the main focus of your work. Respectively, the title can be either interrogative, descriptive, or declarative.

Step 2: Cite the Article

Next, create a proper citation for the reviewed article and input it following the title. At this step, the most important thing to keep in mind is the style of citation specified by your instructor in the requirements for the paper. For example, an article citation in the MLA style should look as follows:

Author's last and first name. "The title of the article." Journal's title and issue(publication date): page(s). Print

Abraham John. "The World of Dreams." Virginia Quarterly 60.2(1991): 125-67. Print.

Step 3: Article Identification

After your citation, you need to include the identification of your reviewed article:

- Title of the article

- Title of the journal

- Year of publication

All of this information should be included in the first paragraph of your paper.

The report "Poverty increases school drop-outs" was written by Brian Faith – a Health officer – in 2000.

Step 4: Introduction

Your organization in an assignment like this is of the utmost importance. Before embarking on your writing process, you should outline your assignment or use an article review template to organize your thoughts coherently.