- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Suggestions for Kids

- Fiction Suggestions

- Nonfiction Suggestions

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Harvard Square Book Circle

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

A History of Ideas: The most intriguing, relevant and helpful concepts from the story of humanity

A collection of humanity’s most inspiring ideas throughout time, bringing perspective to the challenges and wonders of being alive.

This is an unusual sort of history book: a history of ideas – and not just any old ideas, ideas from across time and space that are best suited to healing, enchanting and reviving us.

Along the way, we travel around the world, from the very beginnings of our species right up to the modern age. We hear about the Ancient Greeks and Romans, we learn about Buddhism and Islam, we acquire ideas from Hinduism and the European Renaissance, the Enlightenment and Modernity. Deliberately eclectic, the book gives us a panoramic, 3,000-year view over the finest insights of a diversity of civilisations.

Every idea hangs off an image – it could be a place, a document, a building or a work of art – that has something very specific to teach us. There are ideas here that will stick in our minds because they can help to answer the biggest puzzles we may have: about the direction of our lives, the issues of relationships, the meaning of existence.

The book amounts to a feast for the intellect and the imagination – to make us into the best sorts of historians, those who know how to use the past to shed light on their own lives.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

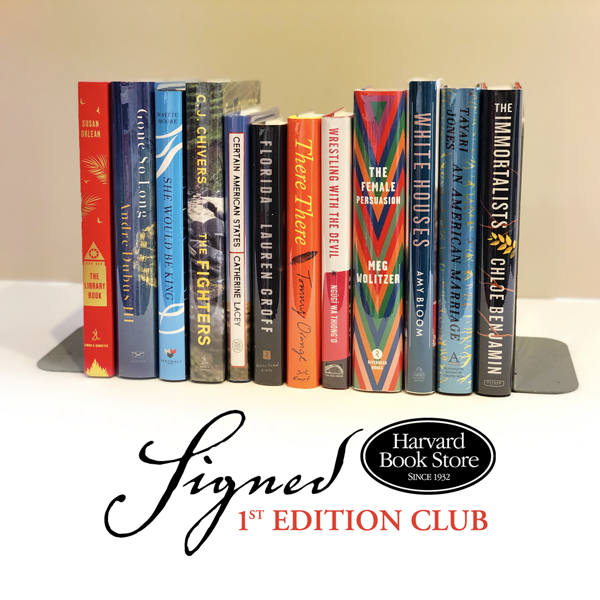

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

Mark Bevir establishes the framework and rationale for his tremendously ambitious book on the first page of the Preface (p. ix) when he says he draws on analytic philosophy to study the forms of reasoning appropriate to the history of ideas. He privileges what he calls logical and normative (as opposed to historical, sociological or psychological) analysis later referring to it as a post-analytic philosophy or anti-foundationalism. This procedure is given priority over the ontological hermeneutic tradition (chiefly of Gadamer) and provides his chosen route to the justification and explanation of understanding. He is careful to disclaim that what he is doing is incompatible with that other tradition arguing they can be complementary as different approaches to different issues. In contrast to the Skinner-Pocock school of textual interpretation Bevir argues no single method can logically prise open meaning objectively. Based on this belief is his reading of epistemologists and philosophers of the mind like the later Wittgenstein and Davidson.

In pursuing his substantial objective - to explain the logic of the history of ideas - in Wittgensteinian fashion the author attempts first to establish the reasoning and concepts associated with it. Bevir calls this the grammar of its concepts that can be determined by both deductive and inductive arguments (p. 2). Very quickly Bevir lays his cards on the table with his claim (in the context of his explication of the failings of analytical philosophy) that 'all our knowledge arises...in the context of our particular web of beliefs' (p. 5). Following Rorty, Bevir suggests that especially in its logical-positivist incarnation, all roads lead away from analytical philosophy (and Descartes and Kant), towards anti-foundationalism. As he says, he will 'go along with the anti-foundational (or post-analytic) conclusion that there are no given truths' (p. 6). However, while he eschews 'the given' both empirically and rationally, or any ultimate or privileged representation, he draws back from and positively rejects 'the irrationalist anti-foundationalism found in post-structuralists and post-modernists such as Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Jean François-Lyotard' (p. 6). This is the essential pivot of Bevir's position. In his effort to demonstrate through his version of the logic of the history of ideas, in which he blurs the distinction between synthetic and analytic propositional forms of knowledge, he attempts to construct and walk a middle road.

This middle road is predicated on Bevir's insistence that the logic of a discipline consists in a normative account of its logic or reasoning, and that invoking historical examples of reasoning simply serve to confuse the issue. In his analysis (of the abstract nature of logics) Bevir claims books like Collingwood's The Idea of History and White's Metahistory confuse the matter by ignoring the logic of explanation which is, of course, the logic of justified belief (deduction and induction). What Bevir tries to do, therefore, is provide a single form of justification that will compromise the synthetic/scientific/empirical and analytical/philosophic/rational forms of knowledge. Because this cannot be done by appeal to 'the given' or accurate representation, it can only be done by an appeal to 'the nature of our being in the world' (p.18). This is explained by a rebuttal of Hayden White's position that historians have no rational grounds for choosing one philosophy of history over another. Bevir suggests White's judgement that our reasons are aesthetic/tropic rather than, as White has recently suggested, logico-deductive (White 2000: 393) should lead him to accept that his choice of explanation in fact commits himself to a particular logic (which undermines his scepticism about knowing truthful things).

The strategy Bevir deploys to pursue his aim, which he does with a doggedness that is remarkable, a clarity of thought which is to be much admired, and a belief in his own abilities that is often breathtaking, is to offer chapter length examinations of the concepts of meaning, objectivity, and belief (the objects of study of the historian of ideas and the essential elements of his grammar of concepts), and synchronic and diachronic forms of explanation and what he calls distortions. By these examinations, and through the application of his 'logic', Bevir offers a valuable insight into the nature of historical thinking and its rethinking.

In his first exploration called 'on meaning', he addresses the nature of intentionalism (strong and weak versions) concluding that he has provided the 'core of a theory of historical meaning' that derives from an individual's weak intentionality in their individual utterances/viewpoints (pp. 76-7). How can the historian of ideas reconstruct the weak intentions of agents objectively? How can we really know what the intentions of the utterer were? By opposing objectivism and scepticism (fixed as the extremes of post-modernist relativism and irrationalism and foundationalist objectivism) Bevir concludes there is a middle road based on 'human practice'. This is Bevir's recognition that while we cannot be certain as to the grounds for what is good history, we can be reasonably sure about our knowledge of past intentions - his definition of objectivity - by comparing and contrasting competing rival webs of theories about meaning. We can also relate objectivity to truth because of what he calls his anthropological epistemology, that is, as he say 'because our ability to find our way around the world vouches for the broad content of our perceptions' (p. 109). Again Bevir walks - but more assuredly now - the middle road. Following on from his position that just because historians are implicated in the act of historical knowing, it does not mean they cannot have objective knowledge of the past, Bevir moves to his analysis of belief. Working from his argument that we can justify objective knowing through fallible 'human practice' and his intentional theory of historical meaning Bevir concludes that sincere, conscious and rational beliefs can be entertained if one does not also hold absolutist expectations of truthfulness. Hence we can explain intentionality in terms of the reasonable expectation of individuals holding such beliefs.

Bevir next explains the nature of the forms of explanation deployed within the history of ideas first what he calls synchronic explanation. This he argues is the formulation or description of the webs of belief held by historians of ideas. This he explains with reference to the connections between tradition and agency. Bevir then attempts to explain how people develop, depart from and change their (inherited, traditional) webs of belief historically, i.e., diachronically. Because people have agency the historian of ideas must have an explanation that accounts for the exercise of that faculty. Bevir uses the concept of the dilemma to explain how rational people change their minds and adapt/adopt new beliefs/webs of belief while remaining sincere, conscious and rational. Bevir concludes his study with an assessment of the irrational, unconscious and deceitful distortions of belief that intrude upon any explanation in the history of ideas. He suggests historians can explain such distortions (deception, self-deception and irrationality) by first recognising such distortions and arguing they arose as logical consequences of the grammar of his concepts. Defined as rogue pro-attitudes explained within the folk-psychology of reason, desire or need. People will the distortions.

Bevir concludes his grand tour of the grammar of concepts and forms of explanation that deploy them by applying his logic to his own explanation. This is Socratic undertaking and an interesting procedure, and one I applaud up to a point. In a sense of course it is just a rationalisation within the terms established within the book and it cannot, therefore, be taken a serious reconsideration, and it certainly isn't a refutation of itself. The implications for the broader field of historical studies of Bevir's explanation of distorted beliefs cast as it is within a framework of rational action theory, is interesting in that it is, as I am sure many historians will point out, a statement of the blindingly obvious (p. 316). Historians 'know' from their own experience of folk psychology how deviancy can be explained and used to explain people's actions at a 'common sense' psychological level. Do historians need to be told how people behave in the ways described and codified by Bevir?

In his rejection of the given - empirical or rational - Bevir pursues his own middle of the road logic or grammar of those concepts operating in the discipline against a background of webs of beliefs. This activity of the justification of meaning and explanation is neither material nor linguistic, it is conceptual. The obvious question is whether you can have a logic or grammar of the concepts used in a discipline, especially history. The other question is, assuming you can have a grammar, has Bevir described it? Are there others? Indeed it is possible to offer detailed criticisms of each of the concepts as defined by Bevir in his grammar. Does he, for example, give adequate attention to Nietzsche's critique of objectivity, i.e., perspectivism? Why should we accept the basic premise of rational action theory? Bevir would, of course, say not to means falling into the miasma of post-structuralism and that is irrational.

Many historians will share Bevir's anti-foundational, liberal and non-reductionist position. Almost certainly the majority of historians would agree with him that our existence is affected/mediated by our concepts and that there is no absolute extra-discursive ground for knowing, that all texts are interpreted within the skein of our webs of ontological commitments, and they would certainly endorse his dismissive attitude toward the 'irrationalism' of postmodern approaches. What would make them less happy is his rejection of the correspondence theory of knowledge. These historians - what elsewhere I have called constructionist historians - would be unhappy with his assumption of rational action theory as the centre of historical understanding. Placing the individual making rational choices in a chaotic world at the centre of historical explanation is for most of them, frankly, unconvincing. To then build a whole logic of historical explanation on it is juvenile. To be more charitable, however, Bevir's position is simply very unfashionable. At worst it denies the role of structure, power, and the embedded nature of irrationalism in both motivation and argument (not as a descent from the ideal but the everyday practice of historical agents) in understanding and explaining the past. I suspect the majority of historians would say Bevir's efforts, though clever, could only be written by a non-practitioner or, even more alarmingly, by the naïve reconstructionist members of the profession.

Central to Bevir's undertaking is the very important question of agent intentionality. He seems to be defending the idea (hermeneuticist in inspiration) that we can accurately interpret the author's meaning when they wrote a text. He roundly attacks Pocock's and Skinner's view that we should take into account context and language rather than authorial intention in doing this (semantic as opposed to hermeneutic meaning). Bevir comes down on the side of 'weak intentionalism' that is the middle of the road position. So it is he establishes his ramparts against all-comers from post-structuralists to materialists. Bevir is not afraid of a fight. This is a good thing as the flaw in his argument (which can be pointed out by all and sundry - and no doubt will be) may be that his equation of meaning with a weak (or strong for that matter) version of intention. In a nutshell, it is possible to argue that just because an utterance is made, it need not necessarily express an intention. Knowing the intention of the author is of no use in determining what the text means unless you accept that intention does equate with meaning. Arguably, in history we have to make up our meanings unless we believe they pre-exist in the data/text and we can, therefore, 'discover' them.

For all its complexities and what for many will be his failings, not least Bevir's unqualified belief in rationalism over irrationalism, sincerity of insincerity and the conscious over the unconscious, the questions his book addresses are important to historians in their everyday work. Of course, those historians who harbour an anti-theory bias will never read it. The very title will put them off. Locate 'logic', 'history' and 'ideas' together in a book title and it is the kiss of death so far as most jobbing historians are concerned. For the majority, I fear, being a good historian does not mean knowing anything about logic, much less the history of ideas. But such a pre-judgement would be quite wrong. Bevir's explorations are useful reminders of the complex nature of agent intentionality, objectivity and belief. From the middle of the road Bevir is able to offer assistance to those who want to believe in the (more or less) accurate knowability of the past. Of course, if you walk down the middle of the road you are also very likely to get knocked over. But I think Bevir knows that and is ready to take the risk.

Note: A detailed examination of The Logic of the History of Ideas is to be found in Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice , 2000, 4.3: 295-350.

- White, Hayden (2000), 'An Old Question Raised Again: Is Historiography Art or Science?', Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice , 4.3, 391-406.

- Munslow, Alun (1997) Deconstructing History , Routledge: London and New York. February 2000

Author's response

Back to reviews index

Back to top

Created Autumn 2001 by the Institute of Historical Research . Copyright notice .

Journal of the History of Ideas

Edited by Manan Ahmed, Martin J. Burke, Stefanos Geroulanos, Ann E. Moyer, Sophie Smith, Don J. Wyatt

Subscriptions

Institutions: please contact your subscription agent or email [email protected] . All subscription payments will be credited toward 2024 subscriptions, which run from January 1st to December 31st. Payments after Oct.31 will receive the following year's issues.

- Journal Content

- Submit an article to the JHI

Journal Information

- ISSN: 0022-5037

- eISSN: 1086-3222

- Frequency: Quarterly

Description

Since its inception in 1940, the Journal of the History of Ideas has served as a medium for the publication of research in intellectual history that is of common interest to scholars and students in a wide range of fields. It is committed to encouraging diversity in regional coverage, chronological range, and methodological approaches. JHI defines intellectual history expansively and ecumenically, including the histories of philosophy, of literature and the arts, of the natural and social sciences, of religion, and of political thought. It also encourages scholarship at the intersections of cultural and intellectual history — for example, the history of the book and of visual culture.

If you have already purchased a subscription to this journal, please login to your account to access your subscription.

- Guidelines for Submission

- Forkosch Prizes

Journal of the History of Ideas 3440 Market Street Ste. 450 Philadelphia, PA 19104-2649 Phone: 215-746-7946 Email: [email protected]

B usiness inquiries, including advertising, should be sent to Penn Press :

University of Pennsylvania Press Journals Division 3905 Spruce Street Philadelphia, PA 19104-4112

Phone: 215-898-6261 Fax: 215-746-3636 Email: [email protected]

To place an order for the journal

Send payment in full, made out to “University of Pennsylvania Press” to: The Sheridan Press, Attn: Penn Press Journals P.O. Box 465 Hanover, PA 17331 Phone: 717-632-3535 – ask for subscriber services Fax: 717-633-8920 Email: [email protected]

The publication and programs of the JHI are made possible through subscription revenues and income derived from its endowment. You are invited to consider making a donation to the JHI in support of its mission. The JHI is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization; donations are tax deductible to the extent permitted by law.

Please click the “donate” button below to contribute via PayPal.

You are also welcome to mail your donation:

Journal of the History of Ideas 3440 Market Street, Suite 450 Philadelphia, PA 19104

Thank you for your commitment to the journal. We are deeply grateful for your support.

Style Sheet: Guide for Authors

Click to download the pdf

Please follow these guidelines when submitting your article to the Journal of the History of Ideas . The editors reserve the right to make editorial revisions in articles and reviews.

- Please submit all manuscripts for consideration through our web-based submission system, ScholarOne: mc04.manuscriptcentral.com/jhi . If you are unable to do so, please contact the editorial office.

- Submitted articles may not exceed 9,000 words, not including footnotes.

- The majority of articles published in the JHI sustain an argument for a minimum of 5,000 words. With rare exceptions, shorter submissions will not be considered.

- Normally, the JHI will not consider for publication articles previously published elsewhere, whether in print or online. Articles made available via university-sponsored open-access repositories are considered published.

- Please eliminate all references that would identify you, in order to facilitate anonymous peer review. To avoid compromising the review process, please do not use the first person in connection with references to your own published work, and use a title that would not be readily available to potential reviewers online, e.g. in a publicly available CV or repeating a conference paper you have given. (Please note that titles can be amended after the review, so you can return to a title of your original choice.)

- The JHI now offers authors the chance to communicate briefly to potential reviewers any considerations they think might be relevant to the evaluation of the article. If, for example, a specific decision has been taken to leave aside a scholarly engagement, and this might surprise the reviewer, then please signal the rationale. Such a note should not be a comment on the origins of the article, nor should it leave the Executive Editors with any concern that it might compromise the integrity of the review process , in which case the article will be returned to the author for re-submission without the note. You may upload the note as a supplemental file, designated “Author’s Note to Reviewers” in ScholarOne. Notes should not exceed 250 words.

Formatting your document :

- Please submit your file as a Word document (.doc or .docx); it will be converted to a PDF when you submit it.

- Please be sure that your file does not have visible editorial markups; that is, if you have edited your file with “track changes” or have made comments, remove those markings before submitting your file.

- Please do not “lock” your file.

- The body of the text should be double-spaced, including quotations, using Times New Roman font in 12-point size.

- Left-align all pages (do not justify) and use 1-inch margins on top and bottom, as well as right and left.

- Place page numbers on each page in the top right corner.

- Notes should be numbered consecutively and formatted as footnotes, in Times New Roman font, 10-point size, single-spaced.

- Notes should be used for citation purposes only; please incorporate all discussion and argumentation into the body of the article.

- If you use a citation manager (Zotero, EndNote, RefWorks, etc.), please remove all field codes from your footnotes prior to submitting your manuscript. To do so, please follow the instructions provided by your citation manager. Most citation managers will allow this procedure: 1. Save a working version of your file. 2. In the file you plan to submit: select the text of all your footnotes and press CTRL+6 for Windows, or CMD+6 for Mac. This will change all footnotes to plain text.

- When using quotation marks, periods and commas should be placed inside the closing quotation mark.

- Block quotations should be free of external quotation marks and indented 0.5 inches, flush-left.

- Inclusive page numbers and dates should be typed according to the following examples: 3–17, 23–26, 100–103, 104–7, 124–28, 1002–6, 1115–20, 1496–1504.

- Please use BCE/CE in lieu of BC/AD.

- Spelling, punctuation, and other conventions should follow standard American usage.

- Authors should obtain permission to reproduce any copyrighted materials (e.g., photographs) they wish to include with their articles. Please submit 300 dpi TIFF files. ScholarOne will accept all your files in series. Supply a list of figures and/or tables, including a caption for each, accompanied by a source line and such acknowledgments as are required. If you are unable to submit images in this format, please contact the editorial office.

Quotations in languages other than English

Please use these guidelines when quoting and citing non-English texts and their translations. These guidelines are designed to give readers access to the source in its original language, while also ensuring that JHI articles are immediately accessible to an Anglophone audience.

- All quotations should appear in the body of the article in English. Where essential to the argument, single words or short phrases in the original language may appear in the body of the article.

- If you quote a published English translation, the footnote should include references to both that translation and the relevant passage in the original-language edition.

- If there is no published English translation, please reproduce the quotation in its original language in the footnote and identify the translator, for example “Translation mine.”

- In some circumstances, when the original-language source is readily and widely available, it may be acceptable to omit the original-language text of quotations from the footnotes.

- In cases where standard scholarly translations of quoted texts are widely available, authors may rely upon them for both text and notes according to the professional standards of their discipline.

The JHI generally follows the current edition of the Chicago Manual of Style , “Documentation I: Notes and Bibliography” (not Author-Date format).

- Notes may be used for citation purposes only . That is, they should contain references to the sources, and may contain quotations in the original language. Notes may not include discursive comments or present additional information .

- The following basic citation examples apply for the first full reference; subsequent references should be shortened to author, short title, and page number. Use shortened citations instead of “ibid” (see CMOS 17th edition, chapter 14.34). See more guidelines regarding notes above.

Book : Richard S. Westfall, Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 200–211.

Translated book: Markus Fierz, Girolamo Cardano, 1501–1576: Physician, Natural Philosopher, Mathematician, Astrologer, and Interpreter of Dream s, trans. Helga Niman (Boston: Birkhäuser, 1983), 109.

Article from a collection of essays :

Jelle Kingma, “Spinoza Editions in the Nineteenth Century,” in Spinoza to the Letter: Studies in Words, Texts, and Books , ed. Fokke Akkerman and Piet Steenbakkers (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 273–81.

Book (part of a multivolume work):

Pierre Jurieu, Histoire du Calvinisme et celle du Papisme mises en parallèle (Rotterdam: Reinier Leers, 1683), 1:512–53.

Journal article :

J. H. M. Salmon, “The Legacy of Jean Bodin: Absolutism, Populism, or Constitutionalism?,” History of Political Though t 17 (1996): 500–522.

- For any author or text treated or discussed in a substantial manner, please use standard critical or scholarly editions, and standard English translations, when they exist.

- Please use full author names in citations, rather than a first initial and last name (except in those cases when the author formats his/her name thus).

- Following the Chicago Manual of Style , non-English titles should be formatted in “sentence style”: the first word of the title and subtitle are capitalized, and the rest of the title is in lower case, with the exception of proper nouns (or those nouns capitalized in the language in question).

Classical references

- The edition, as well as credit for translation, must be specified the first time a work is cited. Please use standard scholarly editions and translations when they exist, unless your argument requires otherwise.

- References to information supplied by a modern editor must include page numbers.

- Plato Republic 360E–361B.

- Cicero De officiis 1.133.

Submission of final draft for publication

- If your article is accepted for publication, you will be asked to submit a finalized manuscript, with all images as needed. Delays at this stage may affect publication date. To avoid delays in production, copyedited drafts and typeset page proofs will be sent to contributors on a strict schedule, in electronic format. The editors will take responsibility for editing and proofreading if they have not received a contributor’s corrections in time to meet production deadlines. The journal reserves the right to charge authors for any excessive amendments to the material at the proof stage.

Copyright and permissions

- It is a condition of publication in the journal that authors grant an exclusive license to the Journal of the History of Ideas, Inc. Authors will be provided with a copyright transfer agreement that must be signed and returned prior to the publication of any work in the journal. It is the author’s responsibility to obtain print and online permission to quote material from third-party sources and to cover any costs incurred in securing these rights. The editors should be alerted at the earliest opportunity as to any difficulty in securing these third-party rights.

- The JHI follows the guidelines of Penn Press regarding permissions. Please note that after publication in the JHI , you have the nonexclusive right to republish your journal article in any work of which you are the sole author, provided only that you credit the original publication. The credit should include the copyright notice exactly as it appears in the original JHI publication. There is no fee for such use. Further information and guidelines are available at http://journals.pennpress.org/archive-and-digital-repository-policy/.

- The publisher will supply the author of an article with 2 copies of the issue in which his or her work is published; additional copies may be ordered at a discounted rate. Offprints may be ordered through the Penn Press website.

The JHI receives regular submissions for “clusters” of articles on a given topic and typically publishes one or two such symposia a year. Recent examples include the symposium “Translation in Action: Global Intellectual History and Early Modern Diplomacy” (82.3) and the symposium “Fascisms and their Afterli(v)es” (82.1).

- Before submitting a cluster of articles, please contact the managing editor for approval: [email protected] .

- Clusters should reflect the JHI ’s commitment to fostering diversity and inclusion among its authors.

- With the exception of article length and submission logistics, all of the instructions on this style guide apply to cluster articles. Authors should adhere to this guide when preparing articles for submission as part of a cluster.

- The total length of the entire cluster (including an introduction and all of the articles and footnotes) should not exceed roughly 30,000 words.

- Once approved, a complete collection of cluster articles should be submitted via e-mail (not ScholarOne) to the managing editor at [email protected] . For each article, please also send a 100-word abstract, 5–10 keywords, and e-mail contact information for the author.

Review Essays

The Journal of the History of Ideas publishes long review essays. The journal does not publish one-page reviews of individual books in the manner that many journals do.

Review essays are substantial discussions of multiple recent works on a given topic. The word length typically ranges from 5,000 to 9,000 words. Review essays are designed to bring readers up to date on significant developments in the field. We imagine our ideal audience to be the graduate student embarking on dissertation research and trying to understand the lay of the land ahead. No portion of the review essay should have been previously published elsewhere.

Peer review

Depending on the needs of the author and the expertise of the editors, review essays may or may not be sent out for peer review.

Submitting a proposal

Prospective authors may submit proposals for potential review essays through our web-based submission manager, Scholar One . Proposals should be roughly 250 words, including a list of titles (books and/or articles) to be addressed in the proposed essay. (In the submission portal, please upload the proposal as a Word doc where you would upload a regular article; an abstract is not necessary for the proposal.) If the proposal is approved, the author is expected to submit a draft within about six months.

Recently published JHI review essays

Steven Nadler, “The Many Lives of René Descartes” Sarah Johnson, “Farewell to The German Ideology” Alisa Zhulina, “The Tyrant and the Martyr: Recent Research on Sovereignty and Theater”

Review Process

- All submissions are read carefully by the JHI ’s executive editors; some are then sent out for external peer review. Please be advised that we do not provide evaluative reports on submissions that are not sent out for external review.

- Does this piece make a significant contribution to scholarship; and if so, what is the nature of that contribution?

- With what scholarly debates does it engage? Does it engage sufficiently with current scholarship; if not, what is missing?

- Are the sources appropriate for the argument? Should additional (or different) sources be used? Are appropriate editions cited?

- Have significant systemically marginalized perspectives been overlooked?

- Does the author make the main argument successfully? Are there points that need fuller development?

- How might this article be improved? How substantial are your recommendations for revision? Might such revisions produce a version that would merit publication in the JHI ?

The Journal of the History of Ideas awards the Selma V. Forkosch Prize ($750) for the best article published in the journal each year.

The winner of the JHI ‘s Selma V. Forkosch Prize for the best article published in 2022 is Dan Edelstein for “ A ‘Revolution’ in Political Thought: Translations of Polybius Book 6 and the Conceptual History of Revolution ” (volume 83, no. 1, pp. 17–40).

This paper excels in historical erudition, philological rigor, and conceptual clarity. It traces the history of the concept of revolution as a political category down to ancient times, to Polybius’s Book 6 and Aristotle’s notion of anacyclosis where it already stood for political change. In Aristotle, the political dimension of the concept was still related to the ideas of revolt and sedition, and not yet conceived as indicating a world-historical event. Likewise, all of the elements of the modern concept of revolution were already in Polybius and his many commentors, although with the implication that revolution had to be avoided and mixed government was the way to keep this danger at bay. It was the re-interpretation of Polybius’s ideas that, for Edelstein, paved the way to incorporate a new temporal dimension to it and eventually conceive of revolutions as the means of solving political problems and improving the future. Revolution is thus transformed from a disturbance of social life into the solution to the ills of modern politics. This article helps us rethink Koselleck’s theory of the temporalization of concepts between ca. 1750 and ca. 1850. Overall, this is an article that straddles the history of scholarship and political theory in a grand way one does not often see.

For a list of the Selma V. Forkosch prize winners click here .

The Journal of the History of Ideas awards the Morris D. Forkosch Prize ($2,500) for the best book in intellectual history each year.

The winner of the JHI ’s Morris D. Forkosch Prize for the best first book in intellectual history (2022) is Nathan Vedal for The Culture of Language in Ming China: Sound, Script, and the Redefinition of Boundaries of Knowledg e ( Columbia University Press , 2022).

The judging committee provides the following statement:

This year’s winner of the Morris D. Forkosch Book Prize is Nathan Vedal for his book The Culture of Language in Ming China: Sound, Script, and the Redefinition of Boundaries of Knowledge , published in 2022 by Columbia University Press . Recent years have witnessed a close reexamination of the early modern history of Chinese philology, to which Vedal’s volume makes an extraordinary contribution. Based on sources, primary and secondary, in a plethora of languages, Vedal draws attention to the distinctive work of Chinese scholars in the latter part of the Ming dynasty, drawing on work in the fields of the history of science, comparative linguistics, music, cosmology, and more. While studies of the Chinese language have blossomed in recent years, Vedal’s work stands out for its great breadth and depth, attending to a multitude of better- and lesser-known scholars, and the unexpected connections at play in their theories of language. Honorable mention for the 2022 prize: Mackenzie Cooley, The Perfection of Nature: Animals, Breeding, and Race in the Renaissance ( University of Chicago Press ).

Eligible submissions are limited to the first book published by a single author, and to books published in English. The subject matter of submissions must pertain to one or more of the disciplines associated with intellectual history and the history of ideas broadly conceived: viz., history (including the histories of the various arts and sciences); philosophy (including the philosophy of science, aesthetics, and other fields); political thought; the social sciences (including anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology); and literature (including literary criticism, history and theory).

No translations or collections of essays will be considered. The judges will favor publications displaying sound scholarship, original conceptualization, and significant chronological and interdisciplinary scope.

Submissions (three copies of each nominated book) are accepted directly from publishers or directly from authors. The deadline to submit books published in 2023 is March 1, 2024.

If you wish to nominate a book, please contact the JHI ‘s managing editor, Ida Stewart, at [email protected] for a shipping address and additional information.

For a list of the Morris D. Forkosch prize winners click here. .

Executive Editors

Manan Ahmed Columbia University

Martin J. Burke The City University of New York

Stefanos Geroulanos New York University

Ann E. Moyer University of Pennsylvania

Sophie Smith University of Oxford

Executive Editors Emeriti

Warren Breckman Anthony Grafton

Managing Editor

Ida Stewart

Editorial Office 3440 Market Street Ste. 450 Philadelphia, PA 19104-2649 Phone: 215-746-7946 Email: [email protected]

Board of Editors

Keisha Blain Brown University

Ann M. Blair Harvard University

Warren Breckman University of Pennsylvania Thomas E. Burman University of Notre Dame

Michael C. Carhart Old Dominion University

Steven Cassedy University of California

Joyce E. Chaplin Harvard University

Marcia Colish Yale University

William J. Connell Seton Hall University

Joy Connolly American Council of Learned Societies

Joshua A. Fogel York University

Farah Godrej University of California

Ursula Goldenbaum Emory University

Peter Eli Gordon Harvard University

Anthony Grafton Princeton University

Maryanne C. Horowitz Occidental College

Florence Hsia University of Wisconsin

Joel Isaac University of Chicago

Donna Jones University of California

Allan Megill University of Virginia

Cary J. Nederman Texas A & M University

Robert E. Norton University of Notre Dame

Elías José Palti Universidad de Buenos Aires

David Harris Sacks Reed College

Jerrold Seigel New York University

Richard Serjeantson University of Cambridge

Peter T. Struck University of Pennsylvania

Nasser Zakariya University of California

Consulting Editors

Ernesto Bassi Alexander Bevilacqua Prachi Deshpande Katrina Forrester Marisa J. Fuentes Daniel Garber Bernard Geoghegan Adom Getachew Abhishek Kaicker Hyeok Hweon Kang Suzanne Marchand Durba Mitra Jacomien Prins Gisèle Sapiro Glenda Sluga

To subscribe, please use the button above.

2024 Subscription Rates

- Students: $32

- Students: $15 Online only

- Individuals: Print and online $52

- Individuals: Online only $42

- Institutions: Print and online $157

- Institutions: Online only $130

For institutional subscriptions please call 717-632-3535 (ask for subscriber services).

Single Issue Prices

- Institutions: $39

- Individuals: $25

To order a single issue, please contact [email protected] .

$21 will be added for shipping to non-US addresses.

To pay by check, please download this order form .

Ideas: A History from Fire to Freud

Published in the United States as: Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud

In this hugely ambitious and exciting book Peter Watson tells the history of ideas from prehistory to the present day, leading to a new way of telling the history of the world. The book begins over a million years ago with a discussion of how the earliest ideas might have originated. Looking at animal behaviour that appears to require some thought – tool-making, territoriality, counting, language (or at least sounds), pairbonding – Peter Watson moves on to the apeman and the development of simple ideas such as cooking, the earliest language, the emergence of family life. All the core areas are tackled – the Ancient Greeks, Christian theology, the ideas of Jesus, astrological thought, the soul, the self, beliefs about the heavens, the ideas of Islam, the Crusades, humanism, the Renaissance, Gutenberg and the book, the scientific revolution, the age of discovery, Shakespeare, the idea of Revolution, the Romantic imagination, Darwin, imperialism, modernism, Freud right up to the present day and the internet. But the book also looks delves into some original and innovative areas – the rise of accuracy (why it happened when it did and why it mattered), early understandings of time, how ideas in the New World differed from those in the Old.

Reviews of Ideas: A History from Fire to Freud

"A grand book … The history of ideas deserves treatment on this scale."

Evening Standard

"A masterpiece of historical writing."

New Statesman

- Non-Fiction Book Reviews

A History of Ideas by The School of Life – Book Review

A History of Ideas

- Publisher – The School of Life

- Release Date – 6th April 2023

- Pages – 248

- ISBN 13 – 978-1912891962

- Format – Hardcover

- Star Rating – 4

I received a free copy of this book. This post contains affiliate links.

A collection of humanity’s most inspiring ideas throughout time, bringing perspective to the challenges and wonders of being alive.

This is an unusual sort of history book: a history of ideas – and not just any old ideas, ideas from across time and space that are best suited to healing, enchanting and reviving us.

Along the way, we travel around the world, from the very beginnings of our species right up to the modern age. We hear about the Ancient Greeks and Romans, we learn about Buddhism and Islam, we acquire ideas from Hinduism and the European Renaissance, the Enlightenment and Modernity. Deliberately eclectic, the book gives us a panoramic, 3,000-year view over the finest insights of a diversity of civilisations.

Every idea hangs off an image – it could be a place, a document, a building or a work of art – that has something very specific to teach us. There are ideas here that will stick in our minds because they can help to answer the biggest puzzles we may have: about the direction of our lives, the issues of relationships, the meaning of existence.

The book amounts to a feast for the intellect and the imagination – to make us into the best sorts of historians, those who know how to use the past to shed light on their own lives.

Review by Stacey

A History of Ideas by The School of Life is a commendable non-fiction book that contains a collection of inspiring ideas throughout time. The book is split into seven sections. Some sections are different historical periods, others continents, and lastly different religions.

Starting with historiography (the history of history), each double-page represents something different and in various timelines. Beginning with a painting that was commissioned in the mid-18th century for the entrance to a private library featuring the Greek Goddess of Wisdom Athena, along with the figure of Truth titled ‘Truth and Wisdom Assist History in Writing’. We then move forward to 1979 and the Grammy Awards and how the wise teach us to look for patterns. This is a book that doesn’t stay in one era for long, jumping back and forth.

The book is very clever and tailored for individuals with a fervour for history or philosophy. It commands the reader’s attention and yet conveys the message of each section in just a few words and with one image. It does at times make you have to read passages over and over again to fully understand what the idea is that is being conveyed to the reader.

Overall, this is an unusual book that someone very knowledgeable would love. It is a book that makes the reader stop and think. It is not a collection of tales about how the wheel came about etc. It is a collection of things such as the idea that reading a book cannot possibly – or for long – change anyone’s thoughts or behaviour. It is a philosopher’s dream book!

Purchase Online:

- Amazon.co.uk

The School of Life

The School of Life is a groundbreaking enterprise which offers good ideas for everyday living. It address such issues as how to find fulfilling work, how to master the art of relationships and how better to understand, and as necessary change, the world – through classes, therapies, books and films. It is headquartered in London, with campuses in Melbourne, Paris, Amsterdam, Sao Paulo, Istanbul, Belgrade, Antwerp, Seoul, Tel Aviv.

The above links are affiliate links. I receive a very small percentage from each item you purchase via these links, which is at no extra cost to you. If you are thinking about purchasing the book, please think about using one of the links. All money received goes back into the blog and helps to keep it running. Thank you.

Tags: Amazon Author Blackwells Book Book Blog Book Blogger Book Review Book Reviewer Four Stars hardcover Non Fiction Review Stacey The School of Life

You may also like...

Word Perfect by Susie Dent – Book Review

by whispering stories · Published 14/04/2021

The Last Cadillac by Nancy Nau Sullivan – Book Review

by whispering stories · Published 19/04/2017 · Last modified 11/05/2022

Money Mum Official by Gemma Bird – Book Review

by whispering stories · Published 07/02/2022

- Next story The Knowing by Emma Hinds – Book Review

- Previous story Interview with Author Erin Pringle

- Author Interviews (101)

- Blog Posts (41)

- Blog Tours (581)

- Book Promo (69)

- Book Reviews (1,609)

- Children's Book Reviews (862)

- Cover Reveals (32)

- Excerpts (47)

- Guest Posts (198)

- Non-Fiction Book Reviews (75)

- Product Reviews (17)

- The Writing Life Of: (367)

- Whispering Wanders (20)

- Writing Tips (37)

- YA Book Reviews (217)

Goodreads Reading Challenge

2024 reading challenge.

Whispering Stories was established in 2015. The blog is here to share our love of books and the bookish world, alongside our other passions in life. We are based in the UK .

Authors, please read our review policy before contacting us for a review.

Quote of the Week

“Life isn’t meant to be lived perfectly…but merely to be LIVED. Boldly, wildly, beautifully, uncertainly, imperfectly, magically LIVED.” ― Mandy Hale

Top Tips for Book Lovers Q&A

How to involve my kids in reading?

Your browser is ancient! Upgrade to a different browser or install Google Chrome Frame to experience this site.

- Subscribe Today!

Literary Review

Book Reviews by subject: History of Ideas

- 17th Century

- 18th Century

- 19th Century

- 20th Century

- Anthropology

- Bibliophiles

- British Empire

- Cultural History

- Elizabethans

- Enlightenment

- History of Art

- History of Science

- Medicine & Disease

- Myths & Folklore

- Nationalism

- Political history

- Religion & Theology

- Russia & the Soviet Union

David Bromwich

Enthusiasm and its discontents, the end of enlightenment: empire, commerce, crisis, by richard whatmore, jonathan wolff, tomorrow is another election, in the long run: the future as a political idea, by jonathan white, richard v reeves, why some are more equal than others, equality: the history of an elusive idea, by darrin m mcmahon, darrin m mcmahon, adam smith the socialist, visions of inequality: from the french revolution to the end of the cold war, by branko milanovic, traders in our midst, free market: the history of an idea, by jacob soll, alexandra gajda, method in the melancholy, the elizabethan mind: searching for the self in an age of uncertainty, by helen hackett, timothy w ryback, bonfires of reason, burning the books: a history of knowledge under attack, by richard ovenden, richard vinen, history boys, conservative revolutionary: the lives of lewis namier, by d w hayton, sir john plumb: the hidden life of a great historian, by neil mckendrick, tim whitmarsh, in defence of reason, the history of philosophy, by a c grayling, a c grayling, a prodigious feat, terrible beauty: a history of the people & ideas that shaped the modern world, by peter watson, frank mclynn, what’s the big idea, out of our minds: what we think and how we came to think it, by felipe fernández-armesto, the joys of enlightenment, power, pleasure, and profit: insatiable appetites from machiavelli to madison, by david wootton, nicholas roe, the birth of romance, a revolution of feeling: the decade that forged the modern mind, by rachel hewitt, jonathan rée, experimental thinking, pain, pleasure, and the greater good: from the panopticon to the skinner box and beyond, by cathy gere, rooms with a view, grand hotel abyss: the lives of the frankfurt school, by stuart jeffries, richard bourke, rational selections, the dream of enlightenment: the rise of modern philosophy, by anthony gottlieb, ian mcbride, dublin’s new dawn, the irish enlightenment, by michael brown, charles elliott, the eleventh’s hour, everything explained that is explainable: on the creation of the encyclopaedia britannica’s celebrated eleventh edition, 1910–1911, by denis boyles, time out of mind, empires of time – calendars, clocks and cultures, by anthony aveni, richard cavendish, the history which never happened, mythology of the british isles, by geoffrey ashe, this new age business, by peter lemesurier, sign up to our newsletter.

@Lit_Review

Follow Literary Review on Twitter

Twitter Feed

‘I have to change’, Miles Davis once said. ‘It’s like a curse.’ @rwilliams1947 tells the story of how Davis made jazz cool.

Richard Williams - In Their Own Sweet Way

Richard Williams: In Their Own Sweet Way - 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the Lo...

literaryreview.co.uk

The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act by Fredric Jameson - review by Terry Eagleton via @Lit_Review

for the new(ish) April issue of @Lit_Review I commissioned a number of pieces, including Deborah Levy on Bowie, Rosa Lyster on creative non-fiction, @JonSavage1966 on Pulp, @mjohnharrison on Oyamada, @rwilliams1947 on Kind of Blue, @chris_power on HGarner

- Podcasts & Videos

- Newsletters

London Review of Books

More search Options

- Advanced search

- Search by contributor

- Browse our cover archive

Browse by Subject

- Arts & Culture

- Biography & Memoir

- History & Classics

- Literature & Criticism

- Philosophy & Law

- Politics & Economics

- Psychology & Anthropology

- Science & Technology

- Latest Issue

- Contributors

- About the LRB

- Close Readings

History of Ideas

David runciman’s acclaimed series of introductions to the most important thinkers and ideas behind modern politics. it’s now part of david’s new weekly podcast, past present future , in which david talks to historians, novelists, scientists and politicians about where the most interesting ideas come from, what they mean, and why they matter. then once a month, he’ll focus on one of the great political essayists, starting with montaigne. these new history of ideas solo talks will be posted here, along with an archive of previous episodes, and links to further reading in the lrb archive..

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Great Political Fictions: ‘Fathers and Sons’

David runciman, 23 february 2024.

This week’s Great Political Fiction is Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons (1862), the definitive novel about the politics – and emotions – of intergenerational conflict.

Great Political Fictions: ‘Mary Stuart’

David runciman, 22 february 2024.

This week’s Great Political Fiction is Friedrich Schiller’s monumental play Mary Stuart (1800), which lays bare the impossible choices faced by two queens – Elizabeth I of England and Mary Queen of Scots – in a world of men.

Great Political Fictions: ‘Gulliver’s Travels’

This week’s episode on the great political fictions is about Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) – part adventure story, part satire of early-eighteenth-century party politics, but above all a coruscating reflection on the failures of human perspective and self-knowledge.

Great Political Fictions: ‘Coriolanus’

In the first episode of our new series on the great political fictions, David talks about Shakespeare’s Coriolanus (1608-9), the last of his tragedies and perhaps his most politically contentious play.

Ta-Nehisi Coates

In the penultimate episode in our series on the great essays, David talks about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s ‘The Case for Reparations’, published in the Atlantic in 2014. Black American life has been marked by injustice from the beginning: this essay explores what can – and what can’t – be done to remedy it, from slavery to the housing market, from Mississippi to Chicago. Plus, what has this story got to do with the origins of the state of Israel?

Umberto Eco

This week’s episode in our series on the great essays and great essayists explores Umberto Eco’s ‘Thoughts on Wikileaks’ (2010). Eco writes about what makes a true scandal, what are real secrets, and what it would mean to expose the hidden workings of power. It is an essay that connects digital technology, medieval mystery and Dan Brown. Plus David talks about the hidden meaning of Julian Assange.

David Foster Wallace

This week’s episode in our series on the great political essays is about David Foster Wallace’s ‘Up, Simba!’, which describes his experiences following the doomed campaign of John McCain for the Republican presidential nomination in 2000. Wallace believed that McCain’s distinctive political style revealed some hard truths about American democracy. Was he right? What did he miss? And how do those truths look now in the age of Trump?

For the last episode in our summer season on the great twentieth-century essays and essayists, David discusses Joan Didion's 'The White Album' (1979), her haunting, impressionistic account of the fracturing of America in the late 1960s.

What was interpretation and why was Sontag so against it? David explores how an argument about art, criticism and the avant-garde can be applied to contemporary politics and can even explain the monstrous appeal of Donald Trump.

This week David discusses James Baldwin’s ‘Notes of a Native Son’ (1955), an essay that combines autobiography with a searing indictment of America’s racial politics.

This week’s episode in our series on the great essays and great essayists is about Simone Weil’s ‘Human Personality’ (1943). Written shortly before her death aged just 34, it is an uncompromising repudiation of the building blocks of modern life.

This week David discusses George Orwell’s ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’ (1941), his great wartime essay about what it does – and doesn’t – mean to be English.

David discusses Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece ‘A Room of One’s Own’ (1929), and how an essay on the conditions for women writing fiction ends up being about so much else besides.

For the third episode in this series about the great political essays, David explores Thoreau’s ‘Civil Disobedience’ (1849), a ringing call to resistance against democratic idiocy.

For the second episode in this season of History of Ideas, David discusses the Scottish philosopher David Hume and explores how eighteenth-century arguments about the national debt can help make sense of American politics today.

Please enable Javascript

This site requires the use of Javascript to provide the best possible experience. Please change your browser settings to allow Javascript content to run.

Join Discovery, the new community for book lovers

Trust book recommendations from real people, not robots 🤓

Blog – Posted on Friday, Mar 29

17 book review examples to help you write the perfect review.

It’s an exciting time to be a book reviewer. Once confined to print newspapers and journals, reviews now dot many corridors of the Internet — forever helping others discover their next great read. That said, every book reviewer will face a familiar panic: how can you do justice to a great book in just a thousand words?

As you know, the best way to learn how to do something is by immersing yourself in it. Luckily, the Internet (i.e. Goodreads and other review sites , in particular) has made book reviews more accessible than ever — which means that there are a lot of book reviews examples out there for you to view!

In this post, we compiled 17 prototypical book review examples in multiple genres to help you figure out how to write the perfect review . If you want to jump straight to the examples, you can skip the next section. Otherwise, let’s first check out what makes up a good review.

Are you interested in becoming a book reviewer? We recommend you check out Reedsy Discovery , where you can earn money for writing reviews — and are guaranteed people will read your reviews! To register as a book reviewer, sign up here.

Pro-tip : But wait! How are you sure if you should become a book reviewer in the first place? If you're on the fence, or curious about your match with a book reviewing career, take our quick quiz:

Should you become a book reviewer?

Find out the answer. Takes 30 seconds!

What must a book review contain?

Like all works of art, no two book reviews will be identical. But fear not: there are a few guidelines for any aspiring book reviewer to follow. Most book reviews, for instance, are less than 1,500 words long, with the sweet spot hitting somewhere around the 1,000-word mark. (However, this may vary depending on the platform on which you’re writing, as we’ll see later.)

In addition, all reviews share some universal elements, as shown in our book review templates . These include:

- A review will offer a concise plot summary of the book.

- A book review will offer an evaluation of the work.

- A book review will offer a recommendation for the audience.

If these are the basic ingredients that make up a book review, it’s the tone and style with which the book reviewer writes that brings the extra panache. This will differ from platform to platform, of course. A book review on Goodreads, for instance, will be much more informal and personal than a book review on Kirkus Reviews, as it is catering to a different audience. However, at the end of the day, the goal of all book reviews is to give the audience the tools to determine whether or not they’d like to read the book themselves.

Keeping that in mind, let’s proceed to some book review examples to put all of this in action.

How much of a book nerd are you, really?

Find out here, once and for all. Takes 30 seconds!

Book review examples for fiction books

Since story is king in the world of fiction, it probably won’t come as any surprise to learn that a book review for a novel will concentrate on how well the story was told .

That said, book reviews in all genres follow the same basic formula that we discussed earlier. In these examples, you’ll be able to see how book reviewers on different platforms expertly intertwine the plot summary and their personal opinions of the book to produce a clear, informative, and concise review.

Note: Some of the book review examples run very long. If a book review is truncated in this post, we’ve indicated by including a […] at the end, but you can always read the entire review if you click on the link provided.

Examples of literary fiction book reviews

Kirkus Reviews reviews Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man :

An extremely powerful story of a young Southern Negro, from his late high school days through three years of college to his life in Harlem.

His early training prepared him for a life of humility before white men, but through injustices- large and small, he came to realize that he was an "invisible man". People saw in him only a reflection of their preconceived ideas of what he was, denied his individuality, and ultimately did not see him at all. This theme, which has implications far beyond the obvious racial parallel, is skillfully handled. The incidents of the story are wholly absorbing. The boy's dismissal from college because of an innocent mistake, his shocked reaction to the anonymity of the North and to Harlem, his nightmare experiences on a one-day job in a paint factory and in the hospital, his lightning success as the Harlem leader of a communistic organization known as the Brotherhood, his involvement in black versus white and black versus black clashes and his disillusion and understanding of his invisibility- all climax naturally in scenes of violence and riot, followed by a retreat which is both literal and figurative. Parts of this experience may have been told before, but never with such freshness, intensity and power.

This is Ellison's first novel, but he has complete control of his story and his style. Watch it.

Lyndsey reviews George Orwell’s 1984 on Goodreads:

YOU. ARE. THE. DEAD. Oh my God. I got the chills so many times toward the end of this book. It completely blew my mind. It managed to surpass my high expectations AND be nothing at all like I expected. Or in Newspeak "Double Plus Good." Let me preface this with an apology. If I sound stunningly inarticulate at times in this review, I can't help it. My mind is completely fried.

This book is like the dystopian Lord of the Rings, with its richly developed culture and economics, not to mention a fully developed language called Newspeak, or rather more of the anti-language, whose purpose is to limit speech and understanding instead of to enhance and expand it. The world-building is so fully fleshed out and spine-tinglingly terrifying that it's almost as if George travelled to such a place, escaped from it, and then just wrote it all down.

I read Fahrenheit 451 over ten years ago in my early teens. At the time, I remember really wanting to read 1984, although I never managed to get my hands on it. I'm almost glad I didn't. Though I would not have admitted it at the time, it would have gone over my head. Or at the very least, I wouldn't have been able to appreciate it fully. […]

The New York Times reviews Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry :

Three-quarters of the way through Lisa Halliday’s debut novel, “Asymmetry,” a British foreign correspondent named Alistair is spending Christmas on a compound outside of Baghdad. His fellow revelers include cameramen, defense contractors, United Nations employees and aid workers. Someone’s mother has FedExed a HoneyBaked ham from Maine; people are smoking by the swimming pool. It is 2003, just days after Saddam Hussein’s capture, and though the mood is optimistic, Alistair is worrying aloud about the ethics of his chosen profession, wondering if reporting on violence doesn’t indirectly abet violence and questioning why he’d rather be in a combat zone than reading a picture book to his son. But every time he returns to London, he begins to “spin out.” He can’t go home. “You observe what people do with their freedom — what they don’t do — and it’s impossible not to judge them for it,” he says.

The line, embedded unceremoniously in the middle of a page-long paragraph, doubles, like so many others in “Asymmetry,” as literary criticism. Halliday’s novel is so strange and startlingly smart that its mere existence seems like commentary on the state of fiction. One finishes “Asymmetry” for the first or second (or like this reader, third) time and is left wondering what other writers are not doing with their freedom — and, like Alistair, judging them for it.

Despite its title, “Asymmetry” comprises two seemingly unrelated sections of equal length, appended by a slim and quietly shocking coda. Halliday’s prose is clean and lean, almost reportorial in the style of W. G. Sebald, and like the murmurings of a shy person at a cocktail party, often comic only in single clauses. It’s a first novel that reads like the work of an author who has published many books over many years. […]

Emily W. Thompson reviews Michael Doane's The Crossing on Reedsy Discovery :

In Doane’s debut novel, a young man embarks on a journey of self-discovery with surprising results.

An unnamed protagonist (The Narrator) is dealing with heartbreak. His love, determined to see the world, sets out for Portland, Oregon. But he’s a small-town boy who hasn’t traveled much. So, the Narrator mourns her loss and hides from life, throwing himself into rehabbing an old motorcycle. Until one day, he takes a leap; he packs his bike and a few belongings and heads out to find the Girl.

Following in the footsteps of Jack Kerouac and William Least Heat-Moon, Doane offers a coming of age story about a man finding himself on the backroads of America. Doane’s a gifted writer with fluid prose and insightful observations, using The Narrator’s personal interactions to illuminate the diversity of the United States.

The Narrator initially sticks to the highways, trying to make it to the West Coast as quickly as possible. But a hitchhiker named Duke convinces him to get off the beaten path and enjoy the ride. “There’s not a place that’s like any other,” [39] Dukes contends, and The Narrator realizes he’s right. Suddenly, the trip is about the journey, not just the destination. The Narrator ditches his truck and traverses the deserts and mountains on his bike. He destroys his phone, cutting off ties with his past and living only in the moment.

As he crosses the country, The Narrator connects with several unique personalities whose experiences and views deeply impact his own. Duke, the complicated cowboy and drifter, who opens The Narrator’s eyes to a larger world. Zooey, the waitress in Colorado who opens his heart and reminds him that love can be found in this big world. And Rosie, The Narrator’s sweet landlady in Portland, who helps piece him back together both physically and emotionally.

This supporting cast of characters is excellent. Duke, in particular, is wonderfully nuanced and complicated. He’s a throwback to another time, a man without a cell phone who reads Sartre and sleeps under the stars. Yet he’s also a grifter with a “love ‘em and leave ‘em” attitude that harms those around him. It’s fascinating to watch The Narrator wrestle with Duke’s behavior, trying to determine which to model and which to discard.

Doane creates a relatable protagonist in The Narrator, whose personal growth doesn’t erase his faults. His willingness to hit the road with few resources is admirable, and he’s prescient enough to recognize the jealousy of those who cannot or will not take the leap. His encounters with new foods, places, and people broaden his horizons. Yet his immaturity and selfishness persist. He tells Rosie she’s been a good mother to him but chooses to ignore the continuing concern from his own parents as he effectively disappears from his old life.

Despite his flaws, it’s a pleasure to accompany The Narrator on his physical and emotional journey. The unexpected ending is a fitting denouement to an epic and memorable road trip.

The Book Smugglers review Anissa Gray’s The Care and Feeding of Ravenously Hungry Girls :

I am still dipping my toes into the literally fiction pool, finding what works for me and what doesn’t. Books like The Care and Feeding of Ravenously Hungry Girls by Anissa Gray are definitely my cup of tea.

Althea and Proctor Cochran had been pillars of their economically disadvantaged community for years – with their local restaurant/small market and their charity drives. Until they are found guilty of fraud for stealing and keeping most of the money they raised and sent to jail. Now disgraced, their entire family is suffering the consequences, specially their twin teenage daughters Baby Vi and Kim. To complicate matters even more: Kim was actually the one to call the police on her parents after yet another fight with her mother. […]

Examples of children’s and YA fiction book reviews

The Book Hookup reviews Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give :

♥ Quick Thoughts and Rating: 5 stars! I can’t imagine how challenging it would be to tackle the voice of a movement like Black Lives Matter, but I do know that Thomas did it with a finesse only a talented author like herself possibly could. With an unapologetically realistic delivery packed with emotion, The Hate U Give is a crucially important portrayal of the difficulties minorities face in our country every single day. I have no doubt that this book will be met with resistance by some (possibly many) and slapped with a “controversial” label, but if you’ve ever wondered what it was like to walk in a POC’s shoes, then I feel like this is an unflinchingly honest place to start.

In Angie Thomas’s debut novel, Starr Carter bursts on to the YA scene with both heart-wrecking and heartwarming sincerity. This author is definitely one to watch.

♥ Review: The hype around this book has been unquestionable and, admittedly, that made me both eager to get my hands on it and terrified to read it. I mean, what if I was to be the one person that didn’t love it as much as others? (That seems silly now because of how truly mesmerizing THUG was in the most heartbreakingly realistic way.) However, with the relevancy of its summary in regards to the unjust predicaments POC currently face in the US, I knew this one was a must-read, so I was ready to set my fears aside and dive in. That said, I had an altogether more personal, ulterior motive for wanting to read this book. […]

The New York Times reviews Melissa Albert’s The Hazel Wood :

Alice Crewe (a last name she’s chosen for herself) is a fairy tale legacy: the granddaughter of Althea Proserpine, author of a collection of dark-as-night fairy tales called “Tales From the Hinterland.” The book has a cult following, and though Alice has never met her grandmother, she’s learned a little about her through internet research. She hasn’t read the stories, because her mother, Ella Proserpine, forbids it.

Alice and Ella have moved from place to place in an attempt to avoid the “bad luck” that seems to follow them. Weird things have happened. As a child, Alice was kidnapped by a man who took her on a road trip to find her grandmother; he was stopped by the police before they did so. When at 17 she sees that man again, unchanged despite the years, Alice panics. Then Ella goes missing, and Alice turns to Ellery Finch, a schoolmate who’s an Althea Proserpine superfan, for help in tracking down her mother. Not only has Finch read every fairy tale in the collection, but handily, he remembers them, sharing them with Alice as they journey to the mysterious Hazel Wood, the estate of her now-dead grandmother, where they hope to find Ella.

“The Hazel Wood” starts out strange and gets stranger, in the best way possible. (The fairy stories Finch relays, which Albert includes as their own chapters, are as creepy and evocative as you’d hope.) Albert seamlessly combines contemporary realism with fantasy, blurring the edges in a way that highlights that place where stories and real life convene, where magic contains truth and the world as it appears is false, where just about anything can happen, particularly in the pages of a very good book. It’s a captivating debut. […]

James reviews Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight, Moon on Goodreads:

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown is one of the books that followers of my blog voted as a must-read for our Children's Book August 2018 Readathon. Come check it out and join the next few weeks!

This picture book was such a delight. I hadn't remembered reading it when I was a child, but it might have been read to me... either way, it was like a whole new experience! It's always so difficult to convince a child to fall asleep at night. I don't have kids, but I do have a 5-month-old puppy who whines for 5 minutes every night when he goes in his cage/crate (hopefully he'll be fully housebroken soon so he can roam around when he wants). I can only imagine! I babysat a lot as a teenager and I have tons of younger cousins, nieces, and nephews, so I've been through it before, too. This was a believable experience, and it really helps show kids how to relax and just let go when it's time to sleep.

The bunny's are adorable. The rhymes are exquisite. I found it pretty fun, but possibly a little dated given many of those things aren't normal routines anymore. But the lessons to take from it are still powerful. Loved it! I want to sample some more books by this fine author and her illustrators.

Publishers Weekly reviews Elizabeth Lilly’s Geraldine :

This funny, thoroughly accomplished debut opens with two words: “I’m moving.” They’re spoken by the title character while she swoons across her family’s ottoman, and because Geraldine is a giraffe, her full-on melancholy mode is quite a spectacle. But while Geraldine may be a drama queen (even her mother says so), it won’t take readers long to warm up to her. The move takes Geraldine from Giraffe City, where everyone is like her, to a new school, where everyone else is human. Suddenly, the former extrovert becomes “That Giraffe Girl,” and all she wants to do is hide, which is pretty much impossible. “Even my voice tries to hide,” she says, in the book’s most poignant moment. “It’s gotten quiet and whispery.” Then she meets Cassie, who, though human, is also an outlier (“I’m that girl who wears glasses and likes MATH and always organizes her food”), and things begin to look up.

Lilly’s watercolor-and-ink drawings are as vividly comic and emotionally astute as her writing; just when readers think there are no more ways for Geraldine to contort her long neck, this highly promising talent comes up with something new.

Examples of genre fiction book reviews

Karlyn P reviews Nora Roberts’ Dark Witch , a paranormal romance novel , on Goodreads:

4 stars. Great world-building, weak romance, but still worth the read.