- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

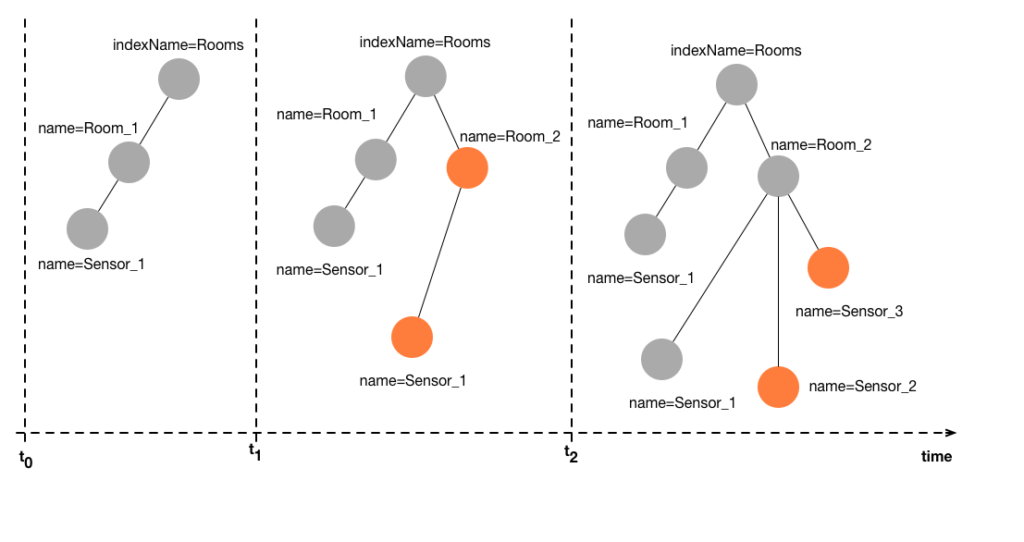

How to Use Tables & Graphs in a Research Paper

It might not seem very relevant to the story and outcome of your study, but how you visually present your experimental or statistical results can play an important role during the review and publication process of your article. A presentation that is in line with the overall logical flow of your story helps you guide the reader effectively from your introduction to your conclusion.

If your results (and the way you organize and present them) don’t follow the story you outlined in the beginning, then you might confuse the reader and they might end up doubting the validity of your research, which can increase the chance of your manuscript being rejected at an early stage. This article illustrates the options you have when organizing and writing your results and will help you make the best choice for presenting your study data in a research paper.

Why does data visualization matter?

Your data and the results of your analysis are the core of your study. Of course, you need to put your findings and what you think your findings mean into words in the text of your article. But you also need to present the same information visually, in the results section of your manuscript, so that the reader can follow and verify that they agree with your observations and conclusions.

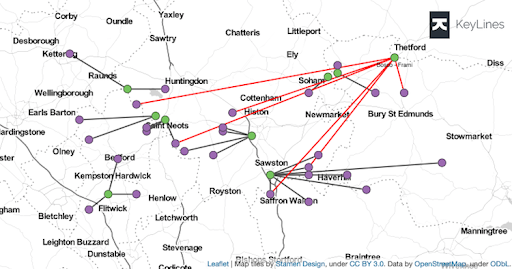

The way you visualize your data can either help the reader to comprehend quickly and identify the patterns you describe and the predictions you make, or it can leave them wondering what you are trying to say or whether your claims are supported by evidence. Different types of data therefore need to be presented in different ways, and whatever way you choose needs to be in line with your story.

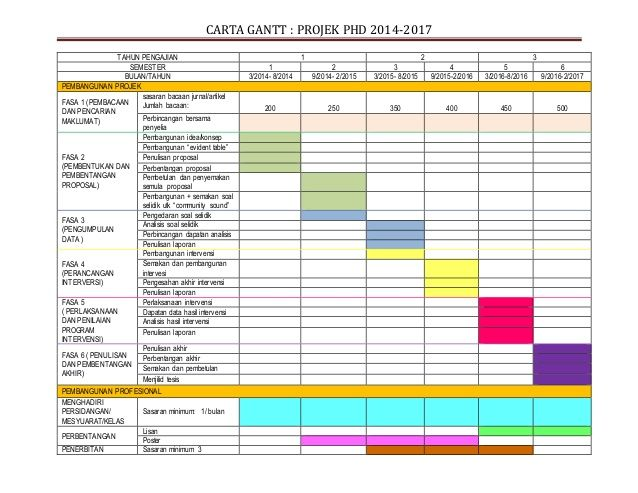

Another thing to keep in mind is that many journals have specific rules or limitations (e.g., how many tables and graphs you are allowed to include, what kind of data needs to go on what kind of graph) and specific instructions on how to generate and format data tables and graphs (e.g., maximum number of subpanels, length and detail level of tables). In the following, we will go into the main points that you need to consider when organizing your data and writing your result section .

Table of Contents:

Types of data , when to use data tables .

- When to Use Data Graphs

Common Types of Graphs in Research Papers

Journal guidelines: what to consider before submission.

Depending on the aim of your research and the methods and procedures you use, your data can be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data, whether objective (e.g., size measurements) or subjective (e.g., rating one’s own happiness on a scale), is what is usually collected in experimental research. Quantitative data are expressed in numbers and analyzed with the most common statistical methods. Qualitative data, on the other hand, can consist of case studies or historical documents, or it can be collected through surveys and interviews. Qualitative data are expressed in words and needs to be categorized and interpreted to yield meaningful outcomes.

Quantitative data example: Height differences between two groups of participants Qualitative data example: Subjective feedback on the food quality in the work cafeteria

Depending on what kind of data you have collected and what story you want to tell with it, you have to find the best way of organizing and visualizing your results.

When you want to show the reader in detail how your independent and dependent variables interact, then a table (with data arranged in columns and rows) is your best choice. In a table, readers can look up exact values, compare those values between pairs or groups of related measurements (e.g., growth rates or outcomes of a medical procedure over several years), look at ranges and intervals, and select specific factors to search for patterns.

Tables are not restrained to a specific type of data or measurement. Since tables really need to be read, they activate the verbal system. This requires focus and some time (depending on how much data you are presenting), but it gives the reader the freedom to explore the data according to their own interest. Depending on your audience, this might be exactly what your readers want. If you explain and discuss all the variables that your table lists in detail in your manuscript text, then you definitely need to give the reader the chance to look at the details for themselves and follow your arguments. If your analysis only consists of simple t-tests to assess differences between two groups, you can report these results in the text (in this case: mean, standard deviation, t-statistic, and p-value), and do not necessarily need to include a table that simply states the same numbers again. If you did extensive analyses but focus on only part of that data (and clearly explain why, so that the reader does not think you forgot to talk about the rest), then a graph that illustrates and emphasizes the specific result or relationship that you consider the main point of your story might be a better choice.

When to Use Data Graphs

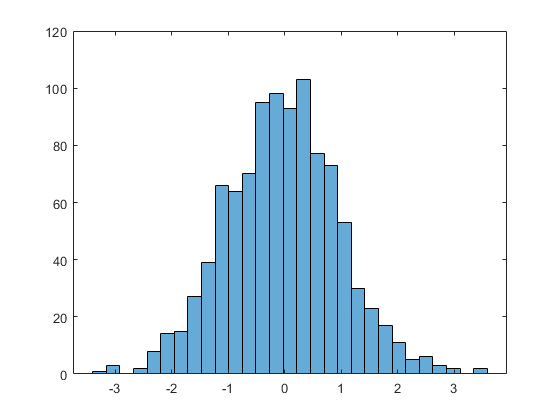

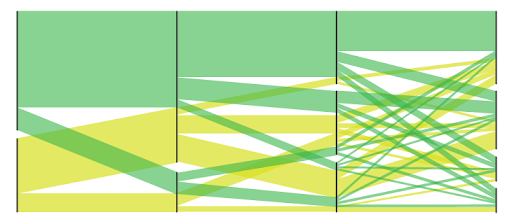

Graphs are a visual display of information and show the overall shape of your results rather than the details. If used correctly, a visual representation helps your (or your reader’s) brain to quickly understand large amounts of data and spot patterns, trends, and exceptions or outliers. Graphs also make it easier to illustrate relationships between entire data sets. This is why, when you analyze your results, you usually don’t just look at the numbers and the statistical values of your tests, but also at histograms, box plots, and distribution plots, to quickly get an overview of what is going on in your data.

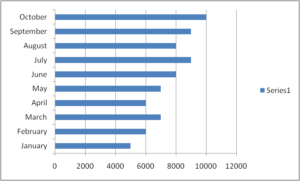

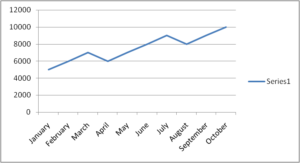

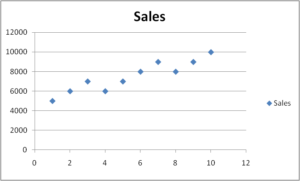

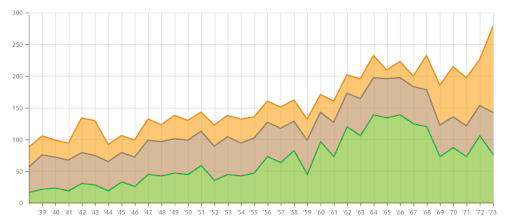

Line graphs

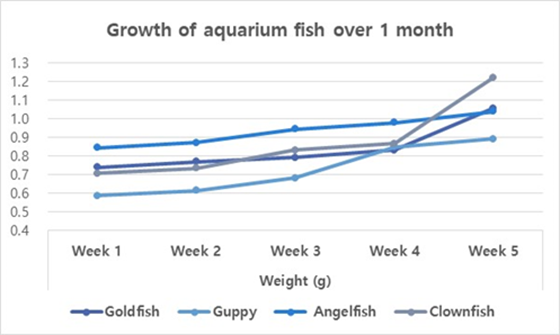

When you want to illustrate a change over a continuous range or time, a line graph is your best choice. Changes in different groups or samples over the same range or time can be shown by lines of different colors or with different symbols.

Example: Let’s collapse across the different food types and look at the growth of our four fish species over time.

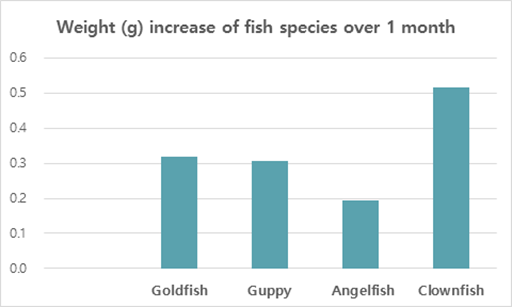

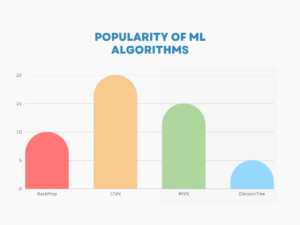

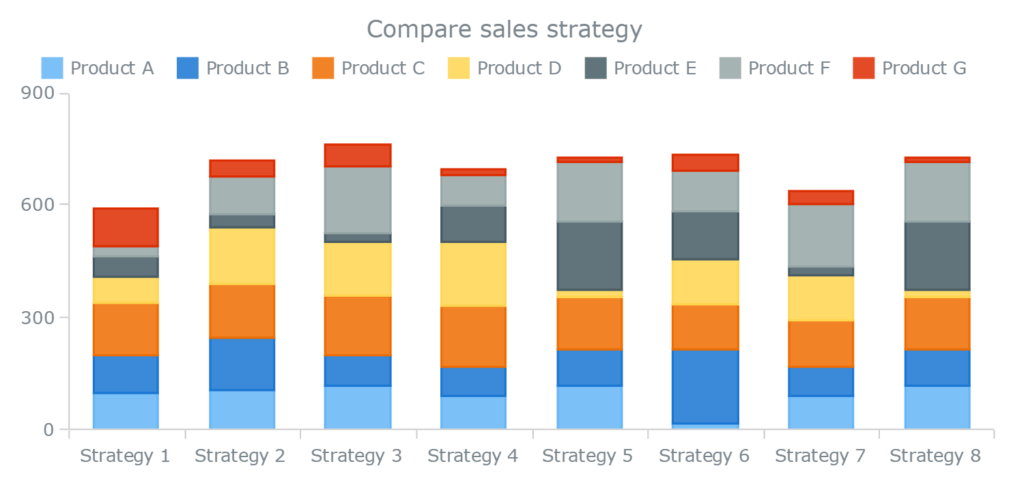

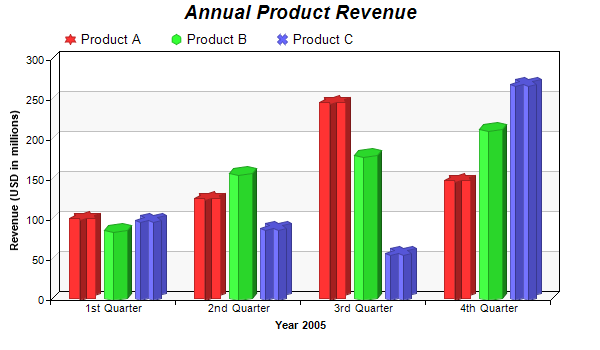

You should use a bar graph when your data is not continuous but divided into categories that are not necessarily connected, such as different samples, methods, or setups. In our example, the different fish types or the different types of food are such non-continuous categories.

Example: Let’s collapse across the food types again and also across time, and only compare the overall weight increase of our four fish types at the end of the feeding period.

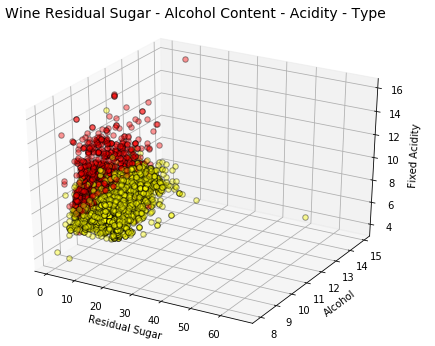

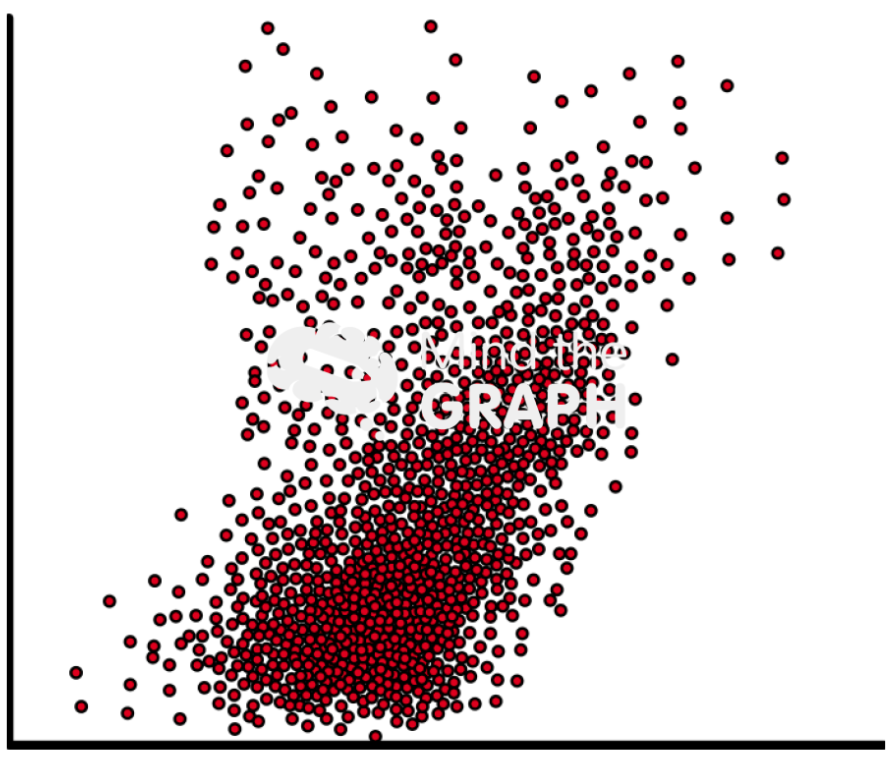

Scatter plots

Scatter plots can be used to illustrate the relationship between two variables — but note that both have to be continuous. The following example displays “fish length” as an additional variable–none of the variables in our table above (fish type, fish food, time) are continuous, and they can therefore not be used for this kind of graph.

As you see, these example graphs all contain less data than the table above, but they lead the reader to exactly the key point of your results or the finding you want to emphasize. If you let your readers search for these observations in a big table full of details that are not necessarily relevant to the claims you want to make, you can create unnecessary confusion. Most journals allow you to provide bigger datasets as supplementary information, and some even require you to upload all your raw data at submission. When you write up your manuscript, however, matching the data presentation to the storyline is more important than throwing everything you have at the reader.

Don’t forget that every graph needs to have clear x and y axis labels , a title that summarizes what is shown above the figure, and a descriptive legend/caption below. Since your caption needs to stand alone and the reader needs to be able to understand it without looking at the text, you need to explain what you measured/tested and spell out all labels and abbreviations you use in any of your graphs once more in the caption (even if you think the reader “should” remember everything by now, make it easy for them and guide them through your results once more). Have a look at this article if you need help on how to write strong and effective figure legends .

Even if you have thought about the data you have, the story you want to tell, and how to guide the reader most effectively through your results, you need to check whether the journal you plan to submit to has specific guidelines and limitations when it comes to tables and graphs. Some journals allow you to submit any tables and graphs initially (as long as tables are editable (for example in Word format, not an image) and graphs of high enough resolution.

Some others, however, have very specific instructions even at the submission stage, and almost all journals will ask you to follow their formatting guidelines once your manuscript is accepted. The closer your figures are already to those guidelines, the faster your article can be published. This PLOS One Figure Preparation Checklist is a good example of how extensive these instructions can be – don’t wait until the last minute to realize that you have to completely reorganize your results because your target journal does not accept tables above a certain length or graphs with more than 4 panels per figure.

Some things you should always pay attention to (and look at already published articles in the same journal if you are unsure or if the author instructions seem confusing) are the following:

- How many tables and graphs are you allowed to include?

- What file formats are you allowed to submit?

- Are there specific rules on resolution/dimension/file size?

- Should your figure files be uploaded separately or placed into the text?

- If figures are uploaded separately, do the files have to be named in a specific way?

- Are there rules on what fonts to use or to avoid and how to label subpanels?

- Are you allowed to use color? If not, make sure your data sets are distinguishable.

If you are dealing with digital image data, then it might also be a good idea to familiarize yourself with the difference between “adjusting” for clarity and visibility and image manipulation, which constitutes scientific misconduct . And to fully prepare your research paper for publication before submitting it, be sure to receive proofreading services , including journal manuscript editing and research paper editing , from Wordvice’s professional academic editors .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tables and Figures

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), which released in October 2019. The equivalent resources for the older APA 6 style can be found at this page as well as at this page (our old resources covered the material on this page on two separate pages).

The purpose of tables and figures in documents is to enhance your readers' understanding of the information in the document; usually, large amounts of information can be communicated more efficiently in tables or figures. Tables are any graphic that uses a row and column structure to organize information, whereas figures include any illustration or image other than a table.

General guidelines

Visual material such as tables and figures can be used quickly and efficiently to present a large amount of information to an audience, but visuals must be used to assist communication, not to use up space, or disguise marginally significant results behind a screen of complicated statistics. Ask yourself this question first: Is the table or figure necessary? For example, it is better to present simple descriptive statistics in the text, not in a table.

Relation of Tables or Figures and Text

Because tables and figures supplement the text, refer in the text to all tables and figures used and explain what the reader should look for when using the table or figure. Focus only on the important point the reader should draw from them, and leave the details for the reader to examine on their own.

Documentation

If you are using figures, tables and/or data from other sources, be sure to gather all the information you will need to properly document your sources.

Integrity and Independence

Each table and figure must be intelligible without reference to the text, so be sure to include an explanation of every abbreviation (except the standard statistical symbols and abbreviations).

Organization, Consistency, and Coherence

Number all tables sequentially as you refer to them in the text (Table 1, Table 2, etc.), likewise for figures (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Abbreviations, terminology, and probability level values must be consistent across tables and figures in the same article. Likewise, formats, titles, and headings must be consistent. Do not repeat the same data in different tables.

Data in a table that would require only two or fewer columns and rows should be presented in the text. More complex data is better presented in tabular format. In order for quantitative data to be presented clearly and efficiently, it must be arranged logically, e.g. data to be compared must be presented next to one another (before/after, young/old, male/female, etc.), and statistical information (means, standard deviations, N values) must be presented in separate parts of the table. If possible, use canonical forms (such as ANOVA, regression, or correlation) to communicate your data effectively.

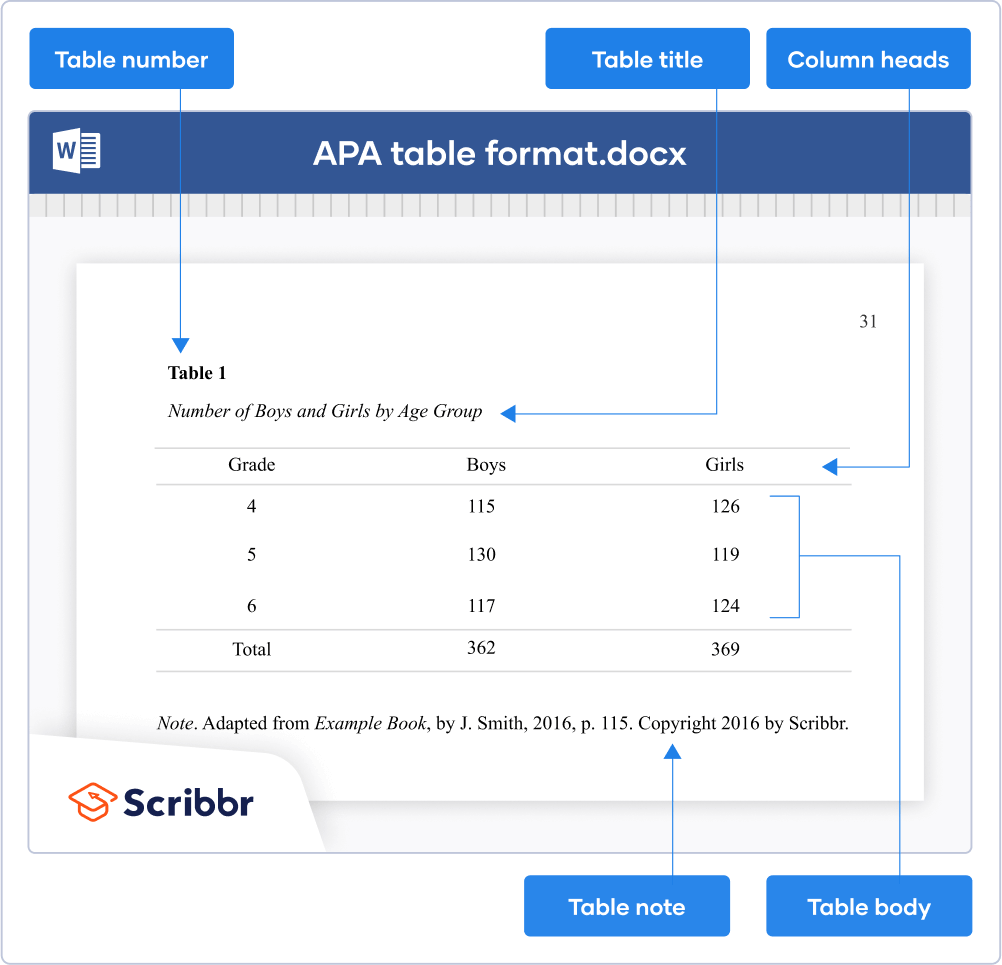

A generic example of a table with multiple notes formatted in APA 7 style.

Elements of Tables

Number all tables with Arabic numerals sequentially. Do not use suffix letters (e.g. Table 3a, 3b, 3c); instead, combine the related tables. If the manuscript includes an appendix with tables, identify them with capital letters and Arabic numerals (e.g. Table A1, Table B2).

Like the title of the paper itself, each table must have a clear and concise title. Titles should be written in italicized title case below the table number, with a blank line between the number and the title. When appropriate, you may use the title to explain an abbreviation parenthetically.

Comparison of Median Income of Adopted Children (AC) v. Foster Children (FC)

Keep headings clear and brief. The heading should not be much wider than the widest entry in the column. Use of standard abbreviations can aid in achieving that goal. There are several types of headings:

- Stub headings describe the lefthand column, or stub column , which usually lists major independent variables.

- Column headings describe entries below them, applying to just one column.

- Column spanners are headings that describe entries below them, applying to two or more columns which each have their own column heading. Column spanners are often stacked on top of column headings and together are called decked heads .

- Table Spanners cover the entire width of the table, allowing for more divisions or combining tables with identical column headings. They are the only type of heading that may be plural.

All columns must have headings, written in sentence case and using singular language (Item rather than Items) unless referring to a group (Men, Women). Each column’s items should be parallel (i.e., every item in a column labeled “%” should be a percentage and does not require the % symbol, since it’s already indicated in the heading). Subsections within the stub column can be shown by indenting headings rather than creating new columns:

Chemical Bonds

Ionic

Covalent

Metallic

The body is the main part of the table, which includes all the reported information organized in cells (intersections of rows and columns). Entries should be center aligned unless left aligning them would make them easier to read (longer entries, usually). Word entries in the body should use sentence case. Leave cells blank if the element is not applicable or if data were not obtained; use a dash in cells and a general note if it is necessary to explain why cells are blank. In reporting the data, consistency is key: Numerals should be expressed to a consistent number of decimal places that is determined by the precision of measurement. Never change the unit of measurement or the number of decimal places in the same column.

There are three types of notes for tables: general, specific, and probability notes. All of them must be placed below the table in that order.

General notes explain, qualify or provide information about the table as a whole. Put explanations of abbreviations, symbols, etc. here.

Example: Note . The racial categories used by the US Census (African-American, Asian American, Latinos/-as, Native-American, and Pacific Islander) have been collapsed into the category “non-White.” E = excludes respondents who self-identified as “White” and at least one other “non-White” race.

Specific notes explain, qualify or provide information about a particular column, row, or individual entry. To indicate specific notes, use superscript lowercase letters (e.g. a , b , c ), and order the superscripts from left to right, top to bottom. Each table’s first footnote must be the superscript a .

a n = 823. b One participant in this group was diagnosed with schizophrenia during the survey.

Probability notes provide the reader with the results of the tests for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate the values for which the null hypothesis is rejected, with the probability ( p value) specified in the probability note. Such notes are required only when relevant to the data in the table. Consistently use the same number of asterisks for a given alpha level throughout your paper.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

If you need to distinguish between two-tailed and one-tailed tests in the same table, use asterisks for two-tailed p values and an alternate symbol (such as daggers) for one-tailed p values.

* p < .05, two-tailed. ** p < .01, two-tailed. † p <.05, one-tailed. †† p < .01, one-tailed.

Borders

Tables should only include borders and lines that are needed for clarity (i.e., between elements of a decked head, above column spanners, separating total rows, etc.). Do not use vertical borders, and do not use borders around each cell. Spacing and strict alignment is typically enough to clarify relationships between elements.

Example of a table in the text of an APA 7 paper. Note the lack of vertical borders.

Tables from Other Sources

If using tables from an external source, copy the structure of the original exactly, and cite the source in accordance with APA style .

Table Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed., Section 7.20)

- Is the table necessary?

- Does it belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or can it go in an online supplemental file?

- Are all comparable tables presented consistently?

- Are all tables numbered with Arabic numerals in the order they are mentioned in the text? Is the table number bold and left-aligned?

- Are all tables referred to in the text?

- Is the title brief but explanatory? Is it presented in italicized title case and left-aligned?

- Does every column have a column heading? Are column headings centered?

- Are all abbreviations; special use of italics, parentheses, and dashes; and special symbols explained?

- Are the notes organized according to the convention of general, specific, probability?

- Are table borders correctly used (top and bottom of table, beneath column headings, above table spanners)?

- Does the table use correct line spacing (double for the table number, title, and notes; single, one and a half, or double for the body)?

- Are entries in the left column left-aligned beneath the centered stub heading? Are all other column headings and cell entries centered?

- Are confidence intervals reported for all major point estimates?

- Are all probability level values correctly identified, and are asterisks attached to the appropriate table entries? Is a probability level assigned the same number of asterisks in all the tables in the same document?

- If the table or its data are from another source, is the source properly cited? Is permission necessary to reproduce the table?

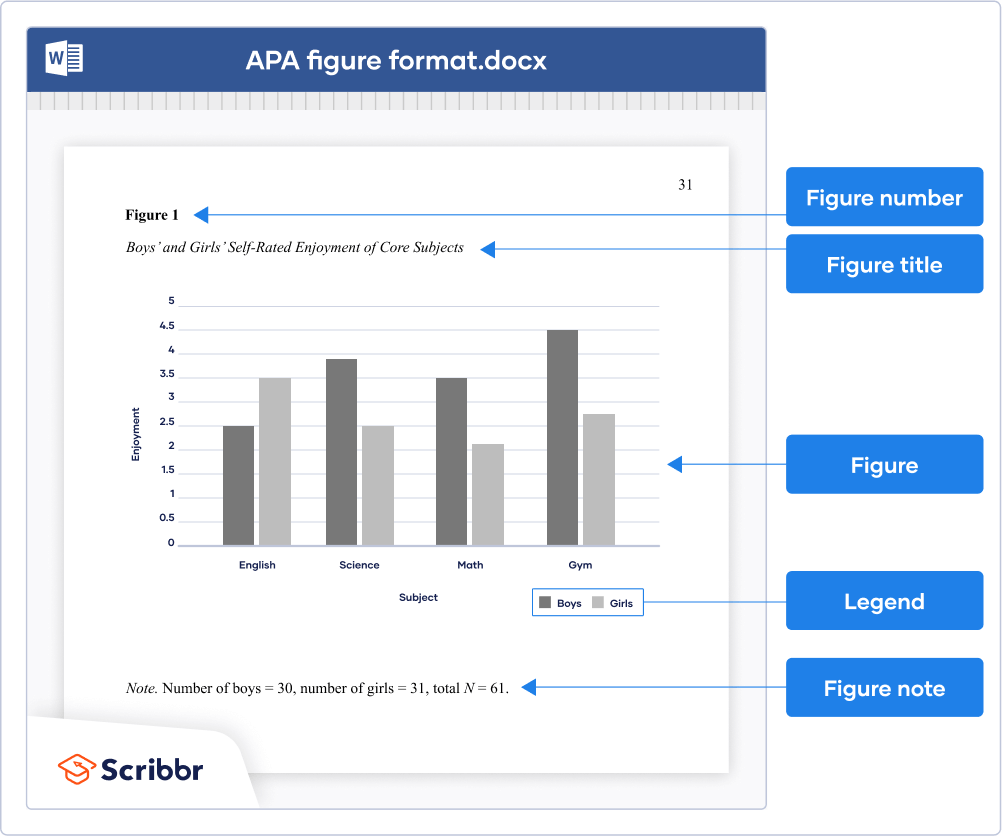

Figures include all graphical displays of information that are not tables. Common types include graphs, charts, drawings, maps, plots, and photos. Just like tables, figures should supplement the text and should be both understandable on their own and referenced fully in the text. This section details elements of formatting writers must use when including a figure in an APA document, gives an example of a figure formatted in APA style, and includes a checklist for formatting figures.

Preparing Figures

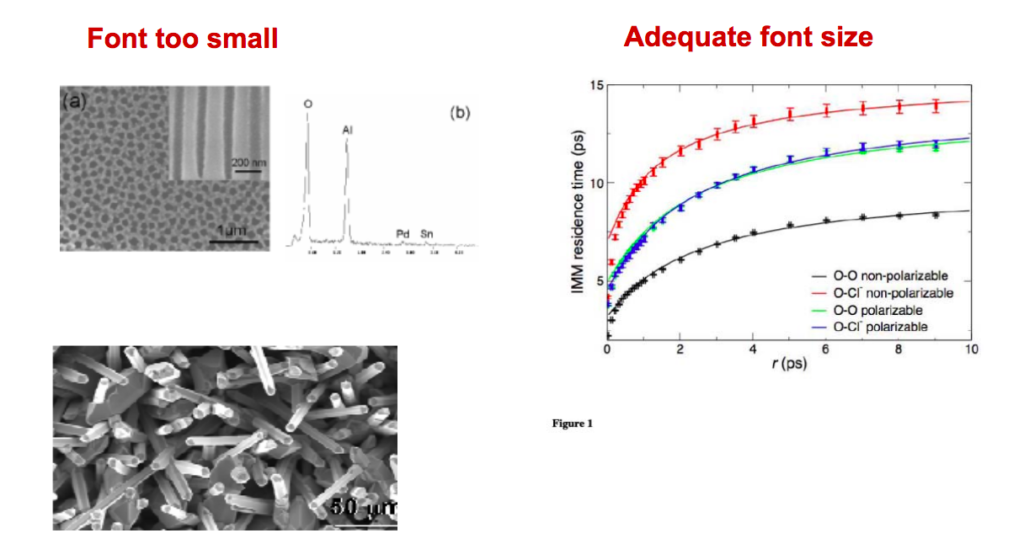

In preparing figures, communication and readability must be the ultimate criteria. Avoid the temptation to use the special effects available in most advanced software packages. While three-dimensional effects, shading, and layered text may look interesting to the author, overuse, inconsistent use, and misuse may distort the data, and distract or even annoy readers. Design properly done is inconspicuous, almost invisible, because it supports communication. Design improperly, or amateurishly, done draws the reader’s attention from the data, and makes him or her question the author’s credibility. Line drawings are usually a good option for readability and simplicity; for photographs, high contrast between background and focal point is important, as well as cropping out extraneous detail to help the reader focus on the important aspects of the photo.

Parts of a Figure

All figures that are part of the main text require a number using Arabic numerals (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Numbers are assigned based on the order in which figures appear in the text and are bolded and left aligned.

Under the number, write the title of the figure in italicized title case. The title should be brief, clear, and explanatory, and both the title and number should be double spaced.

The image of the figure is the body, and it is positioned underneath the number and title. The image should be legible in both size and resolution; fonts should be sans serif, consistently sized, and between 8-14 pt. Title case should be used for axis labels and other headings; descriptions within figures should be in sentence case. Shading and color should be limited for clarity; use patterns along with color and check contrast between colors with free online checkers to ensure all users (people with color vision deficiencies or readers printing in grayscale, for instance) can access the content. Gridlines and 3-D effects should be avoided unless they are necessary for clarity or essential content information.

Legends, or keys, explain symbols, styles, patterns, shading, or colors in the image. Words in the legend should be in title case; legends should go within or underneath the image rather than to the side. Not all figures will require a legend.

Notes clarify the content of the figure; like tables, notes can be general, specific, or probability. General notes explain units of measurement, symbols, and abbreviations, or provide citation information. Specific notes identify specific elements using superscripts; probability notes explain statistical significance of certain values.

A generic example of a figure formatted in APA 7 style.

Figure Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7 th ed., Section 7.35)

- Is the figure necessary?

- Does the figure belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or is it supplemental?

- Is the figure simple, clean, and free of extraneous detail?

- Is the figure title descriptive of the content of the figure? Is it written in italic title case and left aligned?

- Are all elements of the figure clearly labeled?

- Are the magnitude, scale, and direction of grid elements clearly labeled?

- Are parallel figures or equally important figures prepared according to the same scale?

- Are the figures numbered consecutively with Arabic numerals? Is the figure number bold and left aligned?

- Has the figure been formatted properly? Is the font sans serif in the image portion of the figure and between sizes 8 and 14?

- Are all abbreviations and special symbols explained?

- If the figure has a legend, does it appear within or below the image? Are the legend’s words written in title case?

- Are the figure notes in general, specific, and probability order? Are they double-spaced, left aligned, and in the same font as the paper?

- Are all figures mentioned in the text?

- Has written permission for print and electronic reuse been obtained? Is proper credit given in the figure caption?

- Have all substantive modifications to photographic images been disclosed?

- Are the figures being submitted in a file format acceptable to the publisher?

- Have the files been produced at a sufficiently high resolution to allow for accurate reproduction?

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to format tables and figures in APA Style

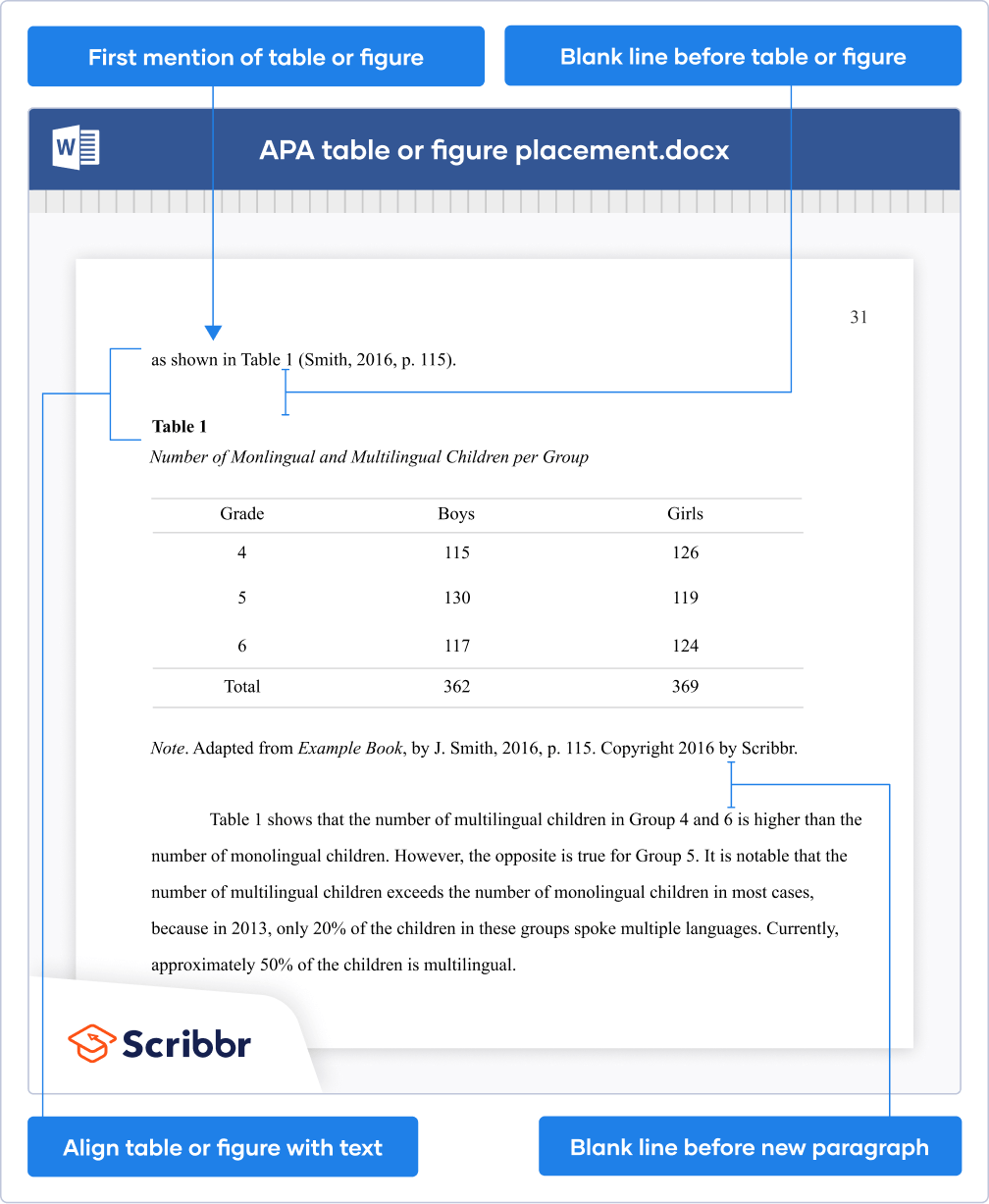

APA Format for Tables and Figures | Annotated Examples

Published on November 5, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on January 17, 2024.

A table concisely presents information (often numbers) in rows and columns. A figure is any other image or illustration you include in your text—anything from a bar chart to a photograph.

Tables and figures differ in terms of how they convey information, but APA Style presents them in a similar format—preceded by a number and title, and followed by explanatory notes (if necessary).

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Apa table format, apa figure format, numbering and titling tables and figures, formatting table and figure notes, where to place tables and figures, referring to tables and figures in the text, frequently asked questions about apa tables and figures.

Tables will vary in size and structure depending on the data you’re presenting, but APA gives some general guidelines for their design. To correctly format an APA table, follow these rules:

- Table number in bold above the table.

- Brief title, in italics and title case, below the table number.

- No vertical lines.

- Horizontal lines only where necessary for clarity.

- Clear, concise labels for column and row headings.

- Numbers consistently formatted (e.g. with the same number of decimal places).

- Any relevant notes below the table.

An example of a table formatted according to APA guidelines is shown below.

The table above uses only four lines: Those at the top and bottom, and those separating the main data from the column heads and the totals.

Create your tables using the tools built into your word processor. In Word, you can use the “ Insert table ” tool.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

Any images used within your text are called figures. Figures include data visualization graphics—e.g. graphs, diagrams, flowcharts—as well as things like photographs and artworks.

To correctly format an APA figure, follow these rules:

- Figure number in bold above the figure.

- Brief title, in italics and title case, under the figure number.

- If necessary, clear labels and legends integrated into the image.

- Any relevant notes below the figure.

An example of a figure formatted according to APA guidelines is shown below.

Keep the design of figures as simple as possible. Use colors only where necessary, not just to make the image look more appealing.

For text within the image itself, APA recommends using a sans serif font (e.g. Arial) with a size between 8 and 14 points.

For other figures, such as photographs, you won’t need a legend; the figure consists simply of the image itself, reproduced at an appropriate size and resolution.

Each table or figure is preceded by a number and title.

Tables and figures are each numbered separately, in the order they are referred to in your text. For example, the first table you refer to is Table 1; the fourth figure you refer to is Figure 4.

The title should clearly and straightforwardly describe the content of the table or figure. Omit articles to keep it concise.

The table or figure number appears on its own line, in bold, followed by the title on the following line, in italics and title case.

Where a table or figure needs further explanation, notes should be included immediately after it. These are not your analysis of the data presented; save that for the main text.

There are three kinds of notes: general , specific , and probability . Each type of note appears in a new paragraph, but multiple notes of the same kind all appear in one paragraph.

Only include the notes that are needed to understand the table or figure. It may be that it is clear in itself, and has no notes, or only probability notes; be as concise as possible.

General notes

General notes come first. They are preceded by the word “ Note ” in italics, followed by a period. They include any explanations that apply to the table or figure as a whole and a citation if it was adapted from another source, and they end with definitions of any abbreviations used.

Specific notes

Specific notes refer to specific points in the table or figure. Superscript letters (a, b, c …) appear at the relevant points in the table or figure and at the start of each note to indicate what they refer to. They are used when it’s necessary to comment on a specific data point or term.

Probability notes

Probability notes give p -values for the data in the table or figure. They correspond to asterisks (and/or other symbols) in the table or figure.

You have two options for the placement of tables and figures in APA Style:

- Option 1: Place tables and figures throughout your text, shortly after the parts of the text that refer to them.

- Option 2: Place them all together at the end of your text (after the reference list) to avoid breaking up the text.

If you place them throughout the text, note that each table or figure should only appear once. If you refer to the same table or figure more than once, don’t reproduce it each time—just place it after the paragraph in which it’s first discussed.

Align the table or figure with the text along the left margin. Leave a line break before and after the table or figure to clearly distinguish it from the main text, and place it on a new page if necessary to avoid splitting it across multiple pages.

If you place all your tables and figures at the end, you should have one table or figure on each page. Begin with all your tables, then place all your figures afterwards.

Avoid making redundant statements about your tables and figures in your text. When you write about data from tables and figures, it should be to highlight or analyze a particular data point or trend, not simply to restate what is already clearly shown in the table or figure:

- As Table 1 shows, there are 115 boys in Grade 4, 130 in Grade 5, and 117 in Grade 6 …

- Table 1 indicates a notable preponderance of boys in Grade 5. It is important to take this into account because …

Additionally, even if you have embedded your tables and figures in your text, refer to them by their numbers, not by their position relative to the text or by description:

- The table below shows…

- Table 1 shows…

- As can be seen in the image on page 4…

- As can be seen in Figure 3…

- The photograph of a bald eagle is an example of…

- Figure 1 is an example of…

In an APA Style paper , use a table or figure when it’s a clearer way to present important data than describing it in your main text. This is often the case when you need to communicate a large amount of information.

Before including a table or figure in your text, always reflect on whether it’s useful to your readers’ understanding:

- Could this information be quickly summarized in the text instead?

- Is it important to your arguments?

- Does the table or figure require too much explanation to be efficient?

If the data you need to present only contains a few relevant numbers, try summarizing it in the text (potentially including full data in an appendix ). If describing the data makes your text overly long and difficult to read, a table or figure may be the best option.

APA doesn’t require you to include a list of tables or a list of figures . However, it is advisable to do so if your text is long enough to feature a table of contents and it includes a lot of tables and/or figures.

A list of tables and list of figures appear (in that order) after your table of contents , and are presented in a similar way.

If you adapt or reproduce a table or figure from another source, you should include that source in your APA reference list . You should also acknowledge the original source in the note or caption for the table or figure.

Tables and figures you created yourself, based on your own data, are not included in the reference list.

In most styles, the title page is used purely to provide information and doesn’t include any images. Ask your supervisor if you are allowed to include an image on the title page before doing so. If you do decide to include one, make sure to check whether you need permission from the creator of the image.

Include a note directly beneath the image acknowledging where it comes from, beginning with the word “ Note .” (italicized and followed by a period). Include a citation and copyright attribution . Don’t title, number, or label the image as a figure , since it doesn’t appear in your main text.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2024, January 17). APA Format for Tables and Figures | Annotated Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/tables-and-figures/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, citing tables and figures from other sources in apa style, how to cite an image in apa style, how to write an apa results section, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Figures and Charts

What this handout is about.

This handout will describe how to use figures and tables to present complicated information in a way that is accessible and understandable to your reader.

Do I need a figure/table?

When planning your writing, it is important to consider the best way to communicate information to your audience, especially if you plan to use data in the form of numbers, words, or images that will help you construct and support your argument. Generally speaking, data summaries may take the form of text, tables or figures. Most writers are familiar with textual data summaries and this is often the best way to communicate simple results. A good rule of thumb is to see if you can present your results clearly in a sentence or two. If so, a table or figure is probably unnecessary. If your data are too numerous or complicated to be described adequately in this amount of space, figures and tables can be effective ways of conveying lots of information without cluttering up your text. Additionally, they serve as quick references for your reader and can reveal trends, patterns, or relationships that might otherwise be difficult to grasp.

So what’s the difference between a table and a figure anyway?

Tables present lists of numbers or text in columns and can be used to synthesize existing literature, to explain variables, or to present the wording of survey questions. They are also used to make a paper or article more readable by removing numeric or listed data from the text. Tables are typically used to present raw data, not when you want to show a relationship between variables.

Figures are visual presentations of results. They come in the form of graphs, charts, drawings, photos, or maps. Figures provide visual impact and can effectively communicate your primary finding. Traditionally, they are used to display trends and patterns of relationship, but they can also be used to communicate processes or display complicated data simply. Figures should not duplicate the same information found in tables and vice versa.

Using tables

Tables are easily constructed using your word processor’s table function or a spread sheet program such as Excel. Elements of a table include the Legend or Title, Column Titles, and the Table Body (quantitative or qualitative data). They may also include subheadings and footnotes. Remember that it is just as important to think about the organization of tables as it is to think about the organization of paragraphs. A well-organized table allows readers to grasp the meaning of the data presented with ease, while a disorganized one will leave the reader confused about the data itself, or the significance of the data.

Title: Tables are headed by a number followed by a clear, descriptive title or caption. Conventions regarding title length and content vary by discipline. In the hard sciences, a lengthy explanation of table contents may be acceptable. In other disciplines, titles should be descriptive but short, and any explanation or interpretation of data should take place in the text. Be sure to look up examples from published papers within your discipline that you can use as a model. It may also help to think of the title as the “topic sentence” of the table—it tells the reader what the table is about and how it’s organized. Tables are read from the top down, so titles go above the body of the table and are left-justified.

Column titles: The goal of column headings is to simplify and clarify the table, allowing the reader to understand the components of the table quickly. Therefore, column titles should be brief and descriptive and should include units of analysis.

Table body: This is where your data are located, whether they are numerical or textual. Again, organize your table in a way that helps the reader understand the significance of the data. Be sure to think about what you want your readers to compare, and put that information in the column (up and down) rather than in the row (across). In other words, construct your table so that like elements read down, not across. When using numerical data with decimals, make sure that the decimal points line up. Whole numbers should line up on the right.

Other table elements

Tables should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are labeled independently of one another. Tables should also have lines demarcating different parts of the table (title, column headers, data, and footnotes if present). Gridlines or boxes should not be included in printed versions. Tables may or may not include other elements, such as subheadings or footnotes.

Quick reference for tables

Tables should be:

- Centered on the page.

- Numbered in the order they appear in the text.

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text.

- Labeled with the table number and descriptive title above the table.

- Labeled with column and/or row labels that describe the data, including units of measurement.

- Set apart from the text itself; text does not flow around the table.

Table 1. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

Table 2. Physical characteristics of the Doctor in the new series of Doctor Who

Using figures

Figures can take many forms. They may be graphs, diagrams, photos, drawings, or maps. Think deliberately about your purpose and use common sense to choose the most effective figure for communicating the main point. If you want your reader to understand spatial relationships, a map or photograph may be the best choice. If you want to illustrate proportions, experiment with a pie chart or bar graph. If you want to illustrate the relationship between two variables, try a line graph or a scatterplot (more on various types of graphs below). Although there are many types of figures, like tables, they share some typical features: captions, the image itself, and any necessary contextual information (which will vary depending on the type of figure you use).

Figure captions

Figures should be labeled with a number followed by a descriptive caption or title. Captions should be concise but comprehensive. They should describe the data shown, draw attention to important features contained within the figure, and may sometimes also include interpretations of the data. Figures are typically read from the bottom up, so captions go below the figure and are left-justified.

The most important consideration for figures is simplicity. Choose images the viewer can grasp and interpret clearly and quickly. Consider size, resolution, color, and prominence of important features. Figures should be large enough and of sufficient resolution for the viewer to make out details without straining their eyes. Also consider the format your paper will ultimately take. Journals typically publish figures in black and white, so any information coded by color will be lost to the reader. On the other hand, color might be a good choice for papers published to the web or for PowerPoint presentations. In any case, use figure elements like color, line, and pattern for effect, not for flash.

Additional information

Figures should be labeled with a number preceding the table title; tables and figures are numbered independently of one another. Also be sure to include any additional contextual information your viewer needs to understand the figure. For graphs, this may include labels, a legend explaining symbols, and vertical or horizontal tick marks. For maps, you’ll need to include a scale and north arrow. If you’re unsure about contextual information, check out several types of figures that are commonly used in your discipline.

Quick reference for figures

Figures should be:

- Labeled (under the figure) with the figure number and appropriate descriptive title (“Figure” can be spelled out [“Figure 1.”] or abbreviated [“Fig. 1.”] as long as you are consistent).

- Referenced in the order they appear in the text (i.e. Figure 1 is referenced in the text before Figure 2 and so forth).

- Set apart from the text; text should not flow around figures.

Every graph is a figure but not every figure is a graph. Graphs are a particular set of figures that display quantitative relationships between variables. Some of the most common graphs include bar charts, frequency histograms, pie charts, scatter plots, and line graphs, each of which displays trends or relationships within and among datasets in a different way. You’ll need to carefully choose the best graph for your data and the relationship that you want to show. More details about some common graph types are provided below. Some good advice regarding the construction of graphs is to keep it simple. Remember that the main objective of your graph is communication. If your viewer is unable to visually decode your graph, then you have failed to communicate the information contained within it.

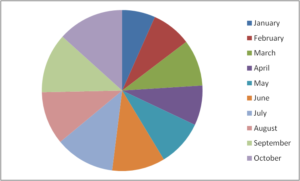

Pie charts are used to show relative proportions, specifically the relationship of a number of parts to the whole. Use pie charts only when the parts of the pie are mutually exclusive categories and the sum of parts adds up to a meaningful whole (100% of something). Pie charts are good at showing “big picture” relationships (i.e. some categories make up “a lot” or “a little” of the whole thing). However, if you want your reader to discern fine distinctions within your data, the pie chart is not for you. Humans are not very good at making comparisons based on angles. We are much better at comparing length, so try a bar chart as an alternative way to show relative proportions. Additionally, pie charts with lots of little slices or slices of very different sizes are difficult to read, so limit yours to 5-7 categories.

The chart shows the relative proportion of fifteen elements in Martian soil, listed in order from “most” to “least”: oxygen, silicon, iron, magnesium, calcium, sulfur, aluminum, sodium, potassium, chlorine, helium, nitrogen, phosphorus, beryllium, and other. Oxygen makes up about ⅓ of the composition, while silicon and iron together make up about ¼. The remaining slices make up smaller proportions, but the percentages aren’t listed in the key and are difficult to estimate. It is also hard to distinguish fifteen colors when comparing the pie chart to the color coded key.

The chart shows the relative proportion of five leisure activities of Venusian teenagers (tanning, trips to Mars, reading, messing with satellites, and stealing Earth cable). Although each of the five slices are about the same size (roughly 20% of the total), the percentage of Venusian teenagers engaging in each activity varies widely (tanning: 80%, trips to Mars: 40%, reading: 12%, messing with satellites: 30%, stealing Earth cable: 77%). Therefore, there is a mismatch between the labels and the actual proportion represented by each activity (in other words, if reading represents 12% of the total, its slice should take up 12% of the pie chart area), which makes the representation inaccurate. In addition, the labels for the five slices add up to 239% (rather than 100%), which makes it impossible to accurately represent this dataset using a pie chart.

Bar graphs are also used to display proportions. In particular, they are useful for showing the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variables are discrete (often nominal) categories. Some examples are occupation, gender, and species. Bar graphs can be vertical or horizontal. In a vertical bar graph the independent variable is shown on the x axis (left to right) and the dependent variable on the y axis (up and down). In a horizontal one, the dependent variable will be shown on the horizontal (x) axis, the independent on the vertical (y) axis. The scale and origin of the graph should be meaningful. If the dependent (numeric) variable has a natural zero point, it is commonly used as a point of origin for the bar chart. However, zero is not always the best choice. You should experiment with both origin and scale to best show the relevant trends in your data without misleading the viewer in terms of the strength or extent of those trends.

The graph shows the number of male and female spaceship crew members for five different popular television series: Star Trek (1965), Battlestar (1978), Star Trek: TNG (1987), Stargate SG-1 (1997), and Firefly (2002). Because the television series are arranged chronologically on the x-axis, the graph can also be used to look for trends in these numbers over time.

Although the number of crew members for each show is similar (ranging from 9 to 11), the proportion of female and male crew members varies. Star Trek has half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 6, respectively), Battlestar has fewer than one-fourth as many female crew members as male crew members (2 and 9, respectively), Star Trek: TNG has four female crew members and six male crew members, Stargate SG-1 has less than one-half as many female crew members as male crew members (3 and 7, respectively), and Firefly has four female and five male crew members.

Frequency histograms/distributions

Frequency histograms are a special type of bar graph that show the relationship between independent and dependent variables, where the independent variable is continuous, rather than discrete. This means that each bar represents a range of values, rather than a single observation. The dependent variables in a histogram are always numeric, but may be absolute (counts) or relative (percentages). Frequency histograms are good for describing populations—examples include the distribution of exam scores for students in a class or the age distribution of the people living in Chapel Hill. You can experiment with bar ranges (also known as “bins”) to achieve the best level of detail, but each range or bin should be of uniform width and clearly labeled.

XY scatter plots

Scatter plots are another way to illustrate the relationship between two variables. In this case, data are displayed as points in an x,y coordinate system, where each point represents one observation along two axes of variation. Often, scatter plots are used to illustrate correlation between two variables—as one variable increases, the other increases (positive correlation) or decreases (negative correlation). However, correlation does not necessarily imply that changes in one variable cause changes in the other. For instance, a third, unplotted variable may be causing both. In other words, scatter plots can be used to graph one independent and one dependent variable, or they can be used to plot two independent variables. In cases where one variable is dependent on another (for example, height depends partly on age), plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis, and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. In addition to correlation (a linear relationship), scatter plots can be used to plot non-linear relationships between variables.

The scatter plot shows the relationship between temperature (x-axis, independent variable) and the number of UFO sightings (y-axis, dependent variable) for 53 separate data points. The temperature ranges from about 0°F and 120°F, and the number of UFO sightings ranges from 1 to 10. The plot shows a low number of UFO sightings (ranging from 1 to 4) at temperatures below 80°F and a much wider range of the number of sightings (from 1 to 10) at temperatures above 80°F. It appears that the number of sightings tends to increase as temperature increases, though there are many cases where only a few sightings occur at high temperatures.

XY line graphs

Line graphs are similar to scatter plots in that they display data along two axes of variation. Line graphs, however, plot a series of related values that depict a change in one variable as a function of another, for example, world population (dependent) over time (independent). Individual data points are joined by a line, drawing the viewer’s attention to local change between adjacent points, as well as to larger trends in the data. Line graphs are similar to bar graphs, but are better at showing the rate of change between two points. Line graphs can also be used to compare multiple dependent variables by plotting multiple lines on the same graph.

Example of an XY line graph:

The line graph shows the age (in years) of the actor of each Doctor Who regeneration for the first through the eleventh regeneration. The ages range from a maximum of about 55 in the first regeneration to a minimum of about 25 in the eleventh regeneration. There is a downward trend in the age of the actors over the course of the eleven regenerations.

General tips for graphs

Strive for simplicity. Your data will be complex. Don’t be tempted to convey the complexity of your data in graphical form. Your job (and the job of your graph) is to communicate the most important thing about the data. Think of graphs like you think of paragraphs—if you have several important things to say about your data, make several graphs, each of which highlights one important point you want to make.

Strive for clarity. Make sure that your data are portrayed in a way that is visually clear. Make sure that you have explained the elements of the graph clearly. Consider your audience. Will your reader be familiar with the type of figure you are using (such as a boxplot)? If not, or if you’re not sure, you may need to explain boxplot conventions in the text. Avoid “chartjunk.” Superfluous elements just make graphs visually confusing. Your reader does not want to spend 15 minutes figuring out the point of your graph.

Strive for accuracy. Carefully check your graph for errors. Even a simple graphical error can change the meaning and interpretation of the data. Use graphs responsibly. Don’t manipulate the data so that it looks like it’s saying something it’s not—savvy viewers will see through this ruse, and you will come off as incompetent at best and dishonest at worst.

How should tables and figures interact with text?

Placement of figures and tables within the text is discipline-specific. In manuscripts (such as lab reports and drafts) it is conventional to put tables and figures on separate pages from the text, as near as possible to the place where you first refer to it. You can also put all the figures and tables at the end of the paper to avoid breaking up the text. Figures and tables may also be embedded in the text, as long as the text itself isn’t broken up into small chunks. Complex raw data is conventionally presented in an appendix. Be sure to check on conventions for the placement of figures and tables in your discipline.

You can use text to guide the reader in interpreting the information included in a figure, table, or graph—tell the reader what the figure or table conveys and why it was important to include it.

When referring to tables and graphs from within the text, you can use:

- Clauses beginning with “as”: “As shown in Table 1, …”

- Passive voice: “Results are shown in Table 1.”

- Active voice (if appropriate for your discipline): “Table 1 shows that …”

- Parentheses: “Each sample tested positive for three nutrients (Table 1).”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bates College. 2012. “ Almost everything you wanted to know about making tables and figures.” How to Write a Paper in Scientific Journal Style and Format , January 11, 2012. http://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWtablefigs.html.

Cleveland, William S. 1994. The Elements of Graphing Data , 2nd ed. Summit, NJ: Hobart Press..

Council of Science Editors. 2014. Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers , 8th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

University of Chicago Press. 2017. The Chicago Manual of Style , 17th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Figures in Research Paper – Examples and Guide

Figures in Research Paper – Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Figures in Research Paper

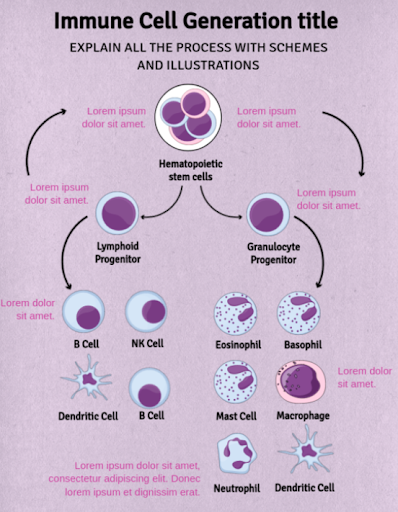

Figures play an essential role in research papers as they provide a visual representation of data, results, and concepts presented in the text. Figures can include graphs, charts, diagrams, photographs, and other visual aids that enhance the reader’s understanding of the research.

Importance of Figures in Research Paper

Here are some specific ways in which figures can be important in a research paper:

- Visual representation of data : Figures can be used to present data in a clear and concise way. This makes it easier for readers to understand the results of experiments and studies.

- Simplify complex ideas: Some concepts can be difficult to explain using words alone. Figures can be used to simplify complex ideas and make them more accessible to a wider audience.

- Increase reader engagement : Figures can make a research paper more engaging and interesting to read. They break up long blocks of text and can make the paper more visually appealing.

- Support arguments: Figures can be used to support arguments made in the paper. For example, a graph or chart can be used to show a correlation between two variables, providing evidence for a particular hypothesis.

- Convey important information: Figures can be used to convey important information quickly and efficiently. This is particularly useful when the paper is being read by someone who is short on time and needs to quickly understand the main points.

Types of Figures in Research Paper

There are several types of figures commonly used in research papers, including:

- Line graphs: These are used to show trends or changes in data over time.

- Bar graphs: These are used to compare data across different categories or groups.

- Pie charts: These are used to show proportions or percentages of data.

- Scatterplots : These are used to show the relationship between two variables.

- Tables : These are used to present large amounts of data in a structured format.

- Photographs or images : These are used to provide visual context or examples of the research being presented.

- Diagrams or schematics : These are used to illustrate complex processes or systems.

How to add Figures to Research Paper

Adding figures to a research paper can be a great way to visually convey important information to the reader. Here are some general guidelines for adding figures to your research paper:

- Determine the appropriate type of figure: Depending on the information you want to convey, you may want to use a graph, chart, table, photograph, or other type of figure.

- Label the figure: Give your figure a descriptive title and number it. Also, include a brief caption that explains what the figure shows.

- Place the figure in the appropriate location : Generally, figures should be placed as close as possible to the text that refers to them. For example, if you mention a figure in the middle of a paragraph, it should be placed within that paragraph.

- Format the figure appropriately: Ensure that the figure is clear and easy to read. Use consistent fonts and font sizes, and make sure the figure is large enough to be easily seen.

- Cite the source of the figure: If the figure was not created by you, you must cite the source of the figure in your paper. This includes citing the author or creator, the date of creation, and any relevant publication information.

- Consider copyright : Ensure that you have permission to use any figures that are copyrighted. If the figure is copyrighted, you may need to obtain permission from the copyright holder to use it in your paper.

How to Label Figures in Research Paper

Labeling figures in a research paper is an important task that helps readers to understand the content of the paper. Here are the steps to label figures in a research paper:

- Decide on the numbering system: Before labeling the figures, decide on the numbering system that you want to use. Typically, figures are numbered consecutively throughout the paper, with the first figure being labeled as “Figure 1,” the second figure as “Figure 2,” and so on.

- Choose a clear and concise caption: A caption is a brief description of the figure that appears below the figure. It should be clear and concise and should describe the content of the figure accurately. The caption should be written in a way that readers can understand the figure without having to read the entire paper.

- Place the label and caption appropriately: The label and caption should be placed below the figure. The label should be centered and should include the figure number and a brief title. The caption should be placed below the label and should describe the figure in detail.

- Use consistent formatting: Make sure that the formatting of the labels and captions is consistent throughout the paper. Use the same font, size, and style for all figures in the paper.

- Reference figures in the text : When referring to a figure in the text, use the figure number and label. For example, “As shown in Figure 1, the results indicate that…”

Figure 1. Distribution of survey responses

In this example, “Figure 1” is the figure number, and “Distribution of survey responses” is a brief title or description of the figure.

The label should be placed at the top of the figure and should be centered. It should be clear and easy to read. It’s important to use a consistent format for all figures in the paper to make it easier for readers to follow.

Examples of Figures in Research Paper

Examples of Figures in Research Papers or Thesis are as follows:

Line graphs Example

Bar graphs Example

Pie charts Example

Scatterplots Example

Tables Example

Photographs or images Example

Diagrams or schematics Example

Purpose of Figures in Research Paper

Some common purposes of figures in research papers are:

- To summarize data: Figures can be used to present data in a concise and easy-to-understand manner. For example, graphs can be used to show trends or patterns in data, while tables can be used to summarize numerical information.

- To support arguments : Figures can be used to support arguments made in the text of the research paper. For example, a figure showing the results of an experiment can help to demonstrate the validity of the conclusions drawn from the experiment.

- To illustrate concepts: Figures can be used to illustrate abstract or complex concepts that are difficult to explain in words. For example, diagrams or illustrations can be used to show the structure of a complex molecule or the workings of a machine.

- To enhance readability: Figures can make a research paper more engaging and easier to read. By breaking up long blocks of text, figures can help to make the paper more visually appealing and easier to understand.

- To provide context : Figures can be used to provide context for the research being presented. For example, a map or diagram can help to show the location or layout of a study site or experimental setup.

- To compare results : Figures can be used to compare results from different experiments or studies. This can help to highlight similarities or differences in the data and draw comparisons between different research findings.

- To show relationships : Figures can be used to show relationships between different variables or factors. For example, a scatter plot can be used to show the correlation between two variables, while a network diagram can be used to show how different elements are connected to each other.

- To present raw data: Figures can be used to present raw data in a way that is easier to understand. For example, a heat map can be used to show the distribution of data over a geographic region, while a histogram can be used to show the distribution of data within a single variable.

Advantages of Figures in Research Paper

Figures (such as charts, graphs, diagrams, and photographs) are an important component of research papers and offer several advantages, including:

- Enhancing clarity : Figures can help to visually communicate complex data or information in a clear and concise manner. They can help readers better understand the research and its findings.

- Saving space : Figures can often convey information more efficiently than text, allowing researchers to present more information in less space.

- Improving readability : Figures can break up large blocks of text and make a paper more visually appealing and easier to read.

- Supporting arguments: Figures can be used to support arguments made in the text and help to strengthen the overall message of the paper.

- Enabling comparisons: Figures can be used to compare different data points, which can be difficult to do with text alone. This can help readers to see patterns and relationships in the data more easily.

- Providing context : Figures can provide context for the research, such as showing the geographic location of study sites or providing a visual representation of the study population.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

Maximizing the Impact of Your Research Paper with Graphs and Charts

The value of visual aids in today’s data-driven study environment cannot be overlooked.

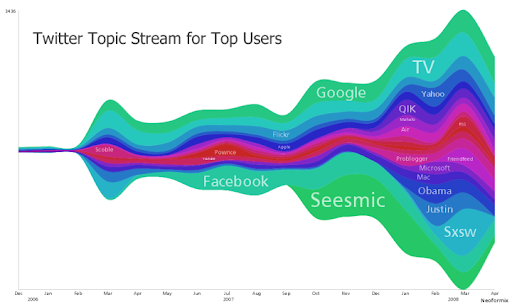

Graphs and charts are effective communication tools that enable academics to convey difficult information to their audience. These visual tools, which range from pie charts to bar graphs, can significantly improve the readability and impact of research articles.

Graphs and charts are indispensable in contemporary research, whether they are used to compare data points, depict trends and patterns, or just break up text-heavy parts.

In this article, the significance of graphs and charts in research papers will be examined, along with their benefits, types of visual aids that are frequently employed, recommended practices for their use, and typical pitfalls to avoid.

By the end of this article, you will have a comprehensive understanding of the role of graphs and charts in research, and how to use them effectively in your next paper.

If you are not well versed with charts and graphs there is a quick fix. Join online c ourses on Data visualization . This will help you learn tricks involved in representing the data in a quick way. If you are still not comfortable the hire a research consultant who will help you in representing the data in a most adorable way. I have written an article on Why Hiring a Research Consultant Can Benefit Your PhD Work? . Please refer the article for further details.

Why add Graphs and Charts to my research paper?

How graphs and charts in research papers are critical, enhance visual appeal and readability of data, convey complex information effectively, enable easy comparison of data points, facilitate understanding of trends and patterns, improved data visualization, enhanced readability, better communication of results, increased credibility, better understanding of data, choosing the right type of graph or chart, making sure the graph or chart is accurate, using clear and concise labelling, adding a title and caption, formatting the graph or chart appropriately, line graphs, scatter plots, best software options for drawing charts and graphs, how do i choose the appropriate scale for my charts and graphs, how do i handle missing data when creating charts and graphs, how to handle huge data sets using charts and graphs, when should i use logarithmic scales in my charts and graphs, how do i ensure that my charts and graphs are accessible to all audiences, including those with disabilities, whether charts and graphs come under copyright protection, what are some common mistakes to avoid when using charts and graphs in research papers, how many graphs and charts should be there in a research paper, what should be the size of graphs and charts in a research paper, can i place charts and graphs at the end of paper instead of in between text, can i place charts and graphs at the end of text as single column instead of two column text, introduction.

Graphs and charts are often used in the Results section of a research paper to visually represent data and findings obtained from experiments or analyses. They may also be included in the Discussion section to support or refute the hypotheses or research questions presented in the Introduction section.

In the Results section, graphs and charts may be used to display statistical analyses such as histograms, scatter plots, and box plots. They can also be used to show trends over time or across different groups, such as line graphs or bar charts. Tables may also be used to present numerical data in a more organized and concise manner.

I have written an article on How to write Results Section of your Research Paper . The article helps you to represent the results in a better fashion, which will in turn increase the chances of paper acceptance.

In the Discussion section, graphs and charts may be used to support the interpretation of the results and to draw conclusions. They may also be used to compare the findings of the current study to previous research or to provide visual examples of the phenomena being studied.

I have written an article on 07 Easy Steps for Writing Discussion Section of a Research Paper . This article will help you in analyzing the charts and graphs to gain better insights.

It is important to note that while graphs and charts can be useful tools in a research paper, they should be used sparingly and only when they add value to the presentation of the data. Too many or poorly designed graphs can make the paper difficult to read and understand.

In research papers, graphs and charts are used to aid in the audience’s comprehension of the material being given. Graphs and charts give the data a visual representation that is simple to comprehend, evaluate, and compare.

Researchers may successfully communicate difficult information using graphs and charts, which increases the impact and accessibility of their findings.

Data from the study are best presented using graphs and charts. They can be used to draw attention to significant patterns and trends in the data, to present information in a comprehensible manner, and to engage viewers.

Graphs and charts can assist you in clearly expressing your ideas and leaving an impact, whether you are summarising data for a research paper or presenting study findings to a big audience.

Advantages of Using Graphs and Charts in Research Papers

The use of graphs and charts in research papers offers many advantages that cannot be achieved through text alone. The following points clearly elaborate on the same.

Long passages of text can be broken up using graphs and charts, which also offer a more understandable visual depiction of the data. Additionally, they can improve the research paper’s aesthetic attractiveness, which will draw readers in and keep them reading.

When given in the form of text or raw statistics, data sets can frequently be convoluted and challenging to comprehend. This information can be made more understandable and easier to interpret for the reader by using graphs and charts. Additionally, they can be used to contrast several data sets, which makes it simpler to spot connections and trends.

Graphs and charts allow researchers to present data in a way that makes it easy to compare different data points. For example, a bar graph can be used to compare the values of different categories, while a line graph can be used to track changes over time.

Data trends and patterns that might not be immediately obvious through text alone might be found using graphs and charts. A histogram, for instance, can be used to see the distribution of data points while a scatter plot can be used to find correlations between two variables. Researchers can more easily make sense of their data by using graphs and charts to better comprehend the underlying patterns and trends.

The Benefits of Using Graphs and Charts in Research Papers

There are many benefits to using graphs and charts in research papers, including:

Graphs and charts can help researchers effectively visualize their data, making it easier for them to see patterns, trends, and relationships within their data. This can help researchers make more informed decisions and draw more accurate conclusions based on their data.

Graphs and charts can make research papers more visually appealing and easier to read. By breaking up long blocks of text, graphs and charts can help to hold the reader’s attention and make the information more engaging.

Graphs and charts can help researchers effectively communicate their results to a variety of audiences. By using visual aids, researchers can effectively convey complex data and ideas in a simple, straightforward manner.

The use of graphs and charts can help to increase the credibility of a research paper. By effectively visualizing their data, researchers can demonstrate that their findings are based on a strong understanding of the data and that their results are robust and reliable.

Graphs and charts can help researchers to better understand their data. By visualizing the data, researchers can identify patterns, relationships, and trends that might not be immediately apparent in raw data or text-based summaries.

By taking advantage of the benefits of using graphs and charts in research papers, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their research and effectively communicate their findings to a variety of audiences.

Best Practices for Using Graphs and Charts in Research Papers

There are several best practices that researchers should follow when using graphs and charts in their research papers. These include:

It is important to choose the right type of graph or chart to effectively convey the data and results. Researchers should consider the type of data they are working with, the relationships they want to highlight, and the message they want to convey when selecting a graph or chart.

It is important to ensure that the data represented in a graph or chart is accurate and that the graph or chart is properly labelled. Researchers should also be careful to ensure that the scale used in a graph or chart is appropriate for the data being displayed.

Labels should be clear, concise, and accurately describe the data being displayed. Researchers should use labelling to highlight the key points of their data and to make it easy for the reader to understand the message being conveyed.

A title and caption should be included with each graph or chart to provide context and to summarize the key findings. The title should accurately describe the graph or chart, while the caption should provide additional information and context.

The graph or chart should be presented in a clear, uncomplicated, and readable way. In addition to making sure the graph or chart has the right size and placement within the study report, researchers should avoid utilising too many colours or patterns.

Researchers can efficiently utilise graphs and charts to increase the visual appeal and readability of their research papers as well as to properly communicate their data and results by adhering to certain best practises.

Types of Graphs and Charts Commonly used in Research Papers

There are many types of graphs and charts that can be used in research papers, each with their own strengths and uses.

Bar graphs are used to compare the values of different categories or groups. They are best used to display data that is numerical in nature and can be represented in a structured, organized format. Bar graphs can be horizontal or vertical, and can be used to display data in a variety of ways, including grouped bar graphs, stacked bar graphs, and side-by-side bar graphs.

Line graphs are used to track changes over time and to display trends. They consist of a series of points connected by a line and can be used to display data in a variety of ways, including simple line graphs, multiple line graphs, and cumulative line graphs.

Pie charts are used to represent data as a proportion of the whole. They are best used to display data that is categorical in nature and to display the relationships between different categories.

Scatter plots are used to display the relationship between two variables. They consist of a series of points plotted on a set of axes, and can be used to identify correlations between the two variables.