- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Vaping Q&A: Johns Hopkins Expert on E-Cigarettes and Tobacco Alternatives

Last updated September 17, 2019

Vaping-related illnesses and deaths have drawn national attention since they first were documented last month. More than 380 confirmed and probable cases of lung disease and six deaths associated with e-cigarette use have been recorded in 36 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands as of September 11, according to the CDC .

The illnesses and deaths emphasize that there are risks associated with vaping, says Joanna Cohen, PhD , Bloomberg Professor of Disease Prevention and director of the Institute for Global Tobacco Control at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

In this Q&A, Cohen shares her thoughts on myths behind vaping, what’s in e-liquids, how e-cigarettes are marketed to young people, and other issues.

What’s causing the sudden surge in illnesses and deaths related to vaping? At this point, health authorities have not been able to identify what is causing the illnesses and deaths related to vaping. So far, there has not been one factor—like type of e-liquid, brand, where the vaping device and e-liquid were purchased, etc.—that has been common across all cases.

When will we know what’s behind the cause? Hopefully very soon. The CDC and FDA are continuing to work around the clock to investigate what is causing these serious health problems.

How would people know if their vaping cartridges are safe? Vaping is not safe.

The propylene glycol and/or vegetable glycerin that form the basis of e-liquids are generally regarded as safe for ingestion, but we do not yet know the effects when inhaled. The Surgeon General has concluded that nicotine in e-cigarettes can harm the developing brain. Little is known about inhaling flavor chemicals, but some ingredients used as flavorants are clearly harmful when inhaled. And there can be many other kinds of chemicals in the liquids people vape.

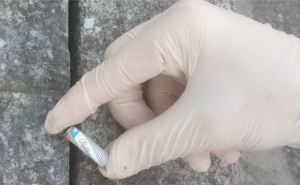

People have used vaping devices to vape other substances, including THC. There are no regulations yet on what the e-liquids contain, and there could be contaminants.

No one should be vaping unless they are a cigarette user trying to quit using cigarettes.

What’s your advice for people who used to smoke traditional cigarettes and have switched to vaping since it was supposed to be safer? Should they go back to tobacco? The only group who should use vaping products are cigarette smokers who are trying to quit smoking, or former smokers who have successfully switched to vaping. If you fully switched and no longer smoke cigarettes, congratulations! Now, it’s important to try to get off vaping products as well because these products are not safe.

If you are in the midst of trying to quit smoking, do not go back to using cigarettes. However, you should monitor yourself for the symptoms associated with the outbreak related to e-cigarette use. The CDC has advice for the public .

Why are flavors in e-cigarettes being targeted for regulations? Flavors are a focus of regulations because flavored products appeal to youth. Most youth who vape use a flavored product.

How has vaping been marketed to children and young people? Youth have been exposed to a marketing for e-cigarette products through a range of channels, including social media/social influencers, product displays in stores, and ads outside of stores.

What laws on e-cigarette sales to young people exist? The Public Health Law Center tracks e-cigarette laws at the state level. There are laws related to vendor licenses, product packaging, taxes, and sales to minors. Michigan recently announced that they are using an administrative rules process to ban the sale of flavored e-cigarettes unless and until they are authorized for sale by the FDA. Last year the city of San Francisco banned the sale of flavored e-cigarettes.

The FDA requires a warning on liquid nicotine. Last week the President indicated that unauthorized flavored e-cigarettes will have to come off the market, but no timelines are available yet. The Institute for Global Tobacco Control tracks e-cigarette policies at the country level .

What are some common myths/perceptions about vaping that are refuted by evidence? One common myth is that vaping is safe. E-cigarettes have been available for just over 10 years, and there is evidence that these products can result in negative effects on our lungs, breathing, and cardiovascular system. E-cigarettes are NOT safe. Cigarettes are also not safe; in fact, they are extremely lethal. So if cigarette smokers have tried various approaches to quitting smoking, unsuccessfully, it is felt at this time that they can try to use e-cigarettes to help them quit cigarettes.

What should schools do about young people and vaping? Pediatricians? Parents? No one other than cigarette smokers trying to quit smoking should be using e-cigarettes.

Schools should prohibit vaping … but realize that when they find a student who is vaping, that student needs their help to get off e-cigarettes. The same with parents and pediatricians. They should advise kids not to use e-cigarettes, and then provide help and support to quit if their child or patient is using these products.

What’s Big Tobacco’s role in e-cigarettes? All major tobacco companies own e-cigarette brands. For example, Altria has a 35% stake in Juul. RJ Reynolds Vapor company is a subsidiary of RJ Reynolds American and markets the Vuse line of e-cigarette products.

For more information on vaping and tobacco issues:

Institute for Global Tobacco Control

The Facts About Electronic Cigarettes—CDC

E-cigarettes, Juuls and Heat-Not-Burn Devices: The Science and Regulation of Vaping —Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health

Related Content

IGTC Research Presented at SRNT Meeting

Training Future Leaders in Latin America and the Caribbean

Research Base Grows in Bangladesh

Assessment of Littered Cigarette Butts in Brazil Informs Strengthening of Global Treaty

Reducing Youth Exposure

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Impact of vaping on...

Impact of vaping on respiratory health

Linked editorial.

Protecting children from harms of vaping

- Related content

- Peer review

- Andrea Jonas , clinical assistant professor

- Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

- Correspondence to A Jonas andreajonas{at}stanford.edu

Widespread uptake of vaping has signaled a sea change in the future of nicotine consumption. Vaping has grown in popularity over the past decade, in part propelled by innovations in vape pen design and nicotine flavoring. Teens and young adults have seen the biggest uptake in use of vape pens, which have superseded conventional cigarettes as the preferred modality of nicotine consumption. Relatively little is known, however, about the potential effects of chronic vaping on the respiratory system. Further, the role of vaping as a tool of smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction remains controversial. The 2019 E-cigarette or Vaping Use-Associated Lung Injury (EVALI) outbreak highlighted the potential harms of vaping, and the consequences of long term use remain unknown. Here, we review the growing body of literature investigating the impacts of vaping on respiratory health. We review the clinical manifestations of vaping related lung injury, including the EVALI outbreak, as well as the effects of chronic vaping on respiratory health and covid-19 outcomes. We conclude that vaping is not without risk, and that further investigation is required to establish clear public policy guidance and regulation.

Abbreviations

BAL bronchoalveolar lavage

CBD cannabidiol

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

DLCO diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

EMR electronic medical record

END electronic nicotine delivery systems

EVALI E-cigarette or Vaping product Use-Associated Lung Injury

LLM lipid laden macrophages

THC tetrahydrocannabinol

V/Q ventilation perfusion

Introduction

The introduction of vape pens to international markets in the mid 2000s signaled a sea change in the future of nicotine consumption. Long the mainstay of nicotine use, conventional cigarette smoking was on the decline for decades in the US, 1 2 largely owing to generational shifts in attitudes toward smoking. 3 With the advent of vape pens, trends in nicotine use have reversed, and the past two decades have seen a steady uptake of vaping among young, never smokers. 4 5 6 Vaping is now the preferred modality of nicotine consumption among young people, 7 and 2020 surveys indicate that one in five US high school students currently vape. 8 These trends are reflected internationally, where the prevalence of vape products has grown in both China and the UK. 9 Relatively little is known, however, regarding the health consequences of chronic vape pen use. 10 11 Although vaping was initially heralded as a safer alternative to cigarette smoking, 12 13 the toxic substances found in vape aerosols have raised new questions about the long term safety of vaping. 14 15 16 17 The 2019 E-cigarette or Vaping product Use-Associated Lung Injury (EVALI) outbreak, ultimately linked to vitamin E acetate in THC vapes, raised further concerns about the health effects of vaping, 18 19 20 and has led to increased scientific interest in the health consequences of chronic vaping. This review summarizes the history and epidemiology of vaping, and the clinical manifestations and proposed pathophysiology of lung injury caused by vaping. The public health consequences of widespread vaping remain to be seen and are compounded by young users of vape pens later transitioning to combustible cigarettes. 4 21 22 Deepened scientific understanding and public awareness of the potential harms of vaping are imperative to confront the challenges posed by a new generation of nicotine users.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched PubMed and Ovid Medline databases for the terms “vape”, “vaping”, “e-cigarette”, “electronic cigarette”, “electronic nicotine delivery”, “electronic nicotine device”, “END”, “EVALI”, “lung injury, diagnosis, management, and treatment” to find articles published between January 2000 and December 2021. We also identified references from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, as well as relevant review articles and public policy resources. Prioritization was given to peer reviewed articles written in English in moderate-to-high impact journals, consensus statements, guidelines, and included randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and case series. We excluded publications that had a qualitative research design, or for which a conflict of interest in funding could be identified, as defined by any funding source or consulting fee from nicotine manufacturers or distributors. Search terms were chosen to generate a broad selection of literature that reflected historic and current understanding of the effects of vaping on respiratory health.

The origins of vaping

Vaping achieved widespread popularity over the past decade, but its origins date back almost a century and are summarized in figure 1 . The first known patent for an “electric vaporizer” was granted in 1930, intended for aerosolizing medicinal compounds. 23 Subsequent patents and prototypes never made it to market, 24 and it wasn’t until 1979 that the first vape pen was commercialized. Dubbed the “Favor” cigarette, the device was heralded as a smokeless alternative to cigarettes and led to the term “vaping” being coined to differentiate the “new age” method of nicotine consumption from conventional, combustible cigarettes. 25 “Favor” cigarettes did not achieve widespread appeal, in part because of the bitter taste of the aerosolized freebase nicotine; however, the term vaping persisted and would go on to be used by the myriad products that have since been developed.

Timeline of vape pen invention to widespread use (1970s-2020)

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The forerunner of the modern vape pen was developed in Beijing in 2003 and later introduced to US markets around 2006. 26 27 Around this time, the future Juul Laboratories founders developed the precursor of the current Juul vape pen while they were students at the Stanford Byers-Center for Biodesign. 28 Their model included disposable cartridges of flavored nicotine solution (pods) that could be inserted into the vape pen, which itself resembled a USB flash drive. Key to their work was the chemical alteration of freebase nicotine to a benzoate nicotine salt. 29 The lower pH of the nicotine salt resulted in an aerosolized nicotine product that lacked a bitter taste, 30 and enabled manufacturers to expand the range of flavored vape products. 31 Juul Laboratories was founded a decade later and quickly rose to dominate the US market, 32 accounting for an estimated 13-59% of the vape products used among teens by 2020. 6 8 Part of the Juul vape pen’s appeal stems from its discreet design, as well as its ability to deliver nicotine with an efficiency matching that of conventional cigarettes. 33 34 Subsequent generations of vape pens have included innovations such as the tank system, which allowed users to select from the wide range of different vape solutions on the market, rather than the relatively limited selection available in traditional pod based systems. Further customizations include the ability to select different vape pen components such as atomizers, heating coils, and fluid wicks, allowing users to calibrate the way in which the vape aerosol is produced. Tobacco companies have taken note of the shifting demographics of nicotine users, as evidenced in 2018 by Altria’s $12.8bn investment in Juul Laboratories. 35

Vaping terminology

At present, vaping serves as an umbrella term that describes multiple modalities of aerosolized nicotine consumption. Vape pens are alternatively called e-cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (END), e-cigars, and e-hookahs. Additional vernacular terms have emerged to describe both the various vape pen devices (eg, tank, mod, dab pen), vape solution (eg, e-liquid, vape juice), as well as the act of vaping (eg, ripping, juuling, puffing, hitting). 36 A conventional vape pen is a battery operated handheld device that contains a storage chamber for the vape solution and an internal element for generating the characteristic vape aerosol. Multiple generations of vape pens have entered the market, including single use, disposable varieties, as well as reusable models that have either a refillable fluid reservoir or a disposable cartridge for the vape solution. Aerosol generation entails a heating coil that atomizes the vape solution, and it is increasingly popular for devices to include advanced settings that allow users to adjust features of the aerosolized nicotine delivery. 37 38 Various devices allow for coil temperatures ranging from 110 °C to over 1000 °C, creating a wide range of conditions for thermal degradation of the vape solution itself. 39 40

The sheer number of vape solutions on the market poses a challenge in understanding the impact of vaping on respiratory health. The spectrum of vape solutions available encompasses thousands of varieties of flavors, additives, and nicotine concentrations. 41 Most vape solutions contain an active ingredient, commonly nicotine 42 ; however, alternative agents include tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD). Vape solutions are typically composed of a combination of a flavorant, nicotine, and a carrier, commonly propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin, that generates the characteristic smoke appearance of vape aerosols. Some 450 brands of vape now offer more than 8000 flavors, 41 a figure that nearly doubled over a three year period. 43 Such tremendous variety does not account for third party sellers who offer users the option to customize a vape solution blend. Addition of marijuana based products such as THC or CBD requires the use of an oil based vape solution carrier to allow for extraction of the psychoactive elements. Despite THC vaping use in nearly 9% of high schoolers, 44 THC vape solutions are subject to minimal market regulation. Finally, a related modality of THC consumption is termed dabbing, and describes the process of inhaling aerosolized THC wax concentrate.

Epidemiology of vaping

Since the early 2000s, vaping has grown in popularity in the US and elsewhere. 8 45 Most of the 68 million vape pen users are concentrated in China, the US, and Europe. 46 Uptake among young people has been particularly pronounced, and in the US vaping has overtaken cigarettes as the most common modality of nicotine consumption among adolescents and young adults. 47 Studies estimate that 20% of US high school students are regular vape pen users, 6 48 in contrast to the 5% of adults who use vape products. 2 Teen uptake of vaping has been driven in part by a perception of vaping as a safer alternative to cigarettes, 49 50 as well as marketing strategies that target adolescents. 33 Teen use of vape pens is further driven by the low financial cost of initiation, with “starter kits” costing less than $25, 51 as well as easy access through peer sales and inconsistent age verification at in-person and online retailers. 52 After sustained growth in use over the 2010s, recent survey data from 2020 suggest that the number of vape pen users has leveled off among teens, perhaps in part owing to increased perceived risk of vaping after the EVALI outbreak. 8 53 The public health implications of teen vaping are compounded by the prevalence of vaping among never smokers (defined as having smoked fewer than 100 lifetime cigarettes), 54 and subsequent uptake of cigarette smoking among vaping teens. 4 55 Similarly, half of adults who currently vape have never used cigarettes, 2 and concern remains that vaping serves as a gateway to conventional cigarette use, 56 57 although these results have been disputed. 58 59 Despite regulation limiting the sale of flavored vape products, 60 a 2020 survey found that high school students were still predominantly using fruit, mint, menthol, and dessert flavored vape solutions. 48 While most data available surround the use of nicotine-containing vape products, a recent meta-analysis showed growing prevalence of adolescents using cannabis-containing products as well. 61

Vaping as harm reduction

Despite facing ongoing questions about safety, vaping has emerged as a potential tool for harm reduction among cigarette smokers. 12 27 An NHS report determined that vaping nicotine is “around 95% less harmful than cigarettes,” 62 leading to the development of programs that promote vaping as a tool of risk reduction among current smokers. A 2020 Cochrane review found that vaping nicotine assisted with smoking cessation over placebo 63 and recent work found increased rates of cigarette abstinence (18% v 9.9%) among those switching to vaping compared with conventional nicotine replacement (eg, gum, patch, lozenge). 64 US CDC guidance suggests that vaping nicotine may benefit current adult smokers who are able to achieve complete cigarette cessation by switching to vaping. 65 66

The public health benefit of vaping for smoking cessation is counterbalanced by vaping uptake among never smokers, 2 54 and questions surrounding the safety of chronic vaping. 10 11 Controversy surrounding the NHS claim of vaping as 95% safer than cigarettes has emerged, 67 68 and multiple leading health organizations have concluded that vaping is harmful. 42 69 Studies have demonstrated airborne particulate matter in the proximity of active vapers, 70 and concern remains that secondhand exposure to vaped aerosols may cause adverse effects, complicating the notion of vaping as a net gain for public health. 71 72 Uncertainty about the potential chronic consequences of vaping combined with vaping uptake among never smokers has complicated attempts to generate clear policy guidance. 73 74 Further, many smokers may exhibit “dual use” of conventional cigarettes and vape pens simultaneously, further complicating efforts to understand the impact of vape exposure on respiratory health, and the role vape use may play in smoking cessation. 12 We are unable to know with certainty the extent of nicotine uptake among young people that would have been seen in the absence of vaping availability, and it remains possible that some young vape pen users may have started on conventional cigarettes regardless. That said, declining nicotine use over the past several decades would argue that many young vape pen users would have never had nicotine uptake had vape pens not been introduced. 1 2 It remains an open question whether public health measures encouraging vaping for nicotine cessation will benefit current smokers enough to offset the impact of vaping uptake among young, never smokers. 75

Vaping lung injury—clinical presentations

Vaping related lung injury: 2012-19.

The potential health effects of vape pen use are varied and centered on injury to the airways and lung parenchyma. Before the 2019 EVALI outbreak, the medical literature detailed case reports of sporadic vaping related acute lung injury. The first known case was reported in 2012, when a patient presented with cough, diffuse ground glass opacities, and lipid laden macrophages (LLM) on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) return in the context of vape pen use. 76 Over the following seven years, an additional 15 cases of vaping related acute lung injury were reported in the literature. These cases included a wide range of diffuse parenchymal lung disease without any clear unifying features, and included cases of eosinophilic pneumonia, 77 78 79 hypersensitivity pneumonitis, 80 organizing pneumonia, 81 82 diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, 83 84 and giant cell foreign body reaction. 85 Although parenchymal lung injury predominated the cases reported, additional cases detailed episodes of status asthmaticus 86 and pneumothoraces 87 attributed to vaping. Non-respiratory vape pen injury has also been described, including cases of nicotine toxicity from vape solution ingestion, 88 89 and injuries sustained owing to vape pen device explosions. 90

The 2019 EVALI outbreak

In the summer of 2019 the EVALI outbreak led to 2807 cases of idiopathic acute lung injury in predominantly young, healthy individuals, which resulted in 68 deaths. 19 91 Epidemiological work to uncover the cause of the outbreak identified an association with vaping, particularly the use of THC-containing products, among affected individuals. CDC criteria for EVALI ( box 1 ) included individuals presenting with respiratory symptoms who had pulmonary infiltrates on imaging in the context of having vaped or dabbed within 90 days of symptom onset, without an alternative identifiable cause. 92 93 After peaking in September 2019, EVALI case numbers steadily declined, 91 likely owing to identification of a link with vaping, and subsequent removal of offending agents from circulation. Regardless, sporadic cases continue to be reported, and a high index of suspicion is required to differentiate EVALI from covid-19 pneumonia. 94 95 A strong association emerged between EVALI cases and the presence of vitamin E acetate in the BAL return of affected individuals 96 ; however, no definitive causal link has been established. Interestingly, the EVALI outbreak was nearly entirely contained within the US with the exception of several dozen cases, at least one of which was caused by an imported US product. 97 98 99 The pattern of cases and lung injury is most suggestive of a vape solution contaminant that was introduced into the distribution pipeline in US markets, leading to a geographically contained pattern of lung injury among users. CDC case criteria for EVALI may have obscured a potential link between viral pneumonia and EVALI, and cases may have been under-recognized following the onset of the covid-19 pandemic.

CDC criteria for establishing EVALI diagnosis

Cdc lung injury surveillance, primary case definitions, confirmed case.

Vape use* in 90 days prior to symptom onset; and

Pulmonary infiltrate on chest radiograph or ground glass opacities on chest computed tomography (CT) scan; and

Absence of pulmonary infection on initial investigation†; and

Absence of alternative plausible diagnosis (eg, cardiac, rheumatological, or neoplastic process).

Probable case

Pulmonary infiltrate on chest radiograph or ground glass opacities on chest CT; and

Infection has been identified; however is not thought to represent the sole cause of lung injury OR minimum criteria** to exclude infection have not been performed but infection is not thought to be the sole cause of lung injury

*Use of e-cigarette, vape pen, or dabbing.

†Minimum criteria for absence of pulmonary infection: negative respiratory viral panel, negative influenza testing (if supported by local epidemiological data), and all other clinically indicated infectious respiratory disease testing is negative.

EVALI—clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features

In the right clinical context, diagnosis of EVALI includes identification of characteristic radiographic and pathologic features. EVALI patients largely fit a pattern of diffuse, acute lung injury in the context of vape pen exposure. A systematic review of 200 reported cases of EVALI showed that those affected were predominantly men in their teens to early 30s, and most (80%) had been using THC-containing products. 100 Presentations included predominantly respiratory (95%), constitutional (87%), and gastrointestinal symptoms (73%). Radiological studies mostly featured diffuse ground glass opacities bilaterally. Of 92 cases that underwent BAL, alveolar fluid samples were most commonly neutrophil predominant, and 81% were additionally positive for LLM on Oil Red O staining. Lung biopsy was not required to achieve the diagnosis; however, of 33 cases that underwent tissue biopsy, common features included organizing pneumonia, inflammation, foamy macrophages, and fibrinous exudates.

EVALI—outcomes

Most patients with EVALI recovered, and prognosis was generally favorable. A systematic review of identified cases found that most patients with confirmed disease required admission to hospital (94%), and a quarter were intubated. 100 Mortality among EVALI patients was low, with estimates around 2-3% across multiple studies. 101 102 103 Mortality was associated with age over 35 and underlying asthma, cardiac disease, or mental health conditions. 103 Notably, the cohorts studied only included patients who presented for medical care, and the samples are likely biased toward a more symptomatic population. It is likely that many individuals experiencing mild symptoms of EVALI did not present for medical care, and would have self-discontinued vaping following extensive media coverage of the outbreak at that time. Although most EVALI survivors recovered well, case series of some individuals show persistent radiographic abnormalities 101 and sustained reductions in DLCO. 104 105 Pulmonary function evaluation of EVALI survivors showed normalization in FEV 1 /FVC on spirometry in some, 106 while others had more variable outcomes. 105 107 108

Vaping induced lung injury—pathophysiology

The causes underlying vaping related acute lung injury remain interesting to clinicians, scientists, and public health officials; multiple mechanisms of injury have been proposed and are summarized in figure 2 . 31 109 110 Despite increased scientific interest in vaping related lung injury following the EVALI outbreak, the pool of data from which to draw meaningful conclusions is limited because of small scale human studies and ongoing conflicts due to tobacco industry funding. 111 Further, insufficient time has elapsed since widespread vaping uptake, and available studies reflect the effects of vaping on lung health over a maximum 10-15 year timespan. The longitudinal effects of vaping may take decades to fully manifest and ongoing prospective work is required to better understand the impacts of vaping on respiratory health.

Schematic illustrating pathophysiology of vaping lung injury

Pro-inflammatory vape aerosol effects

While multiple pathophysiological pathways have been proposed for vaping related lung injury, they all center on the vape aerosol itself as the conduit of lung inflammation. Vape aerosols have been found to harbor a number of toxic substances, including thermal degradation products of the various vape solution components. 112 Mass spectrometry analysis of vape aerosols has identified a variety of oxidative and pro-inflammatory substances including benzene, acrolein, volatile organic compounds, and propylene oxide. 16 17 Vaping additionally leads to airway deposition of ultrafine particles, 14 113 as well as the heavy metals manganese and zinc which are emitted from the vaping coils. 15 114 Fourth generation vape pens allow for high wattage aerosol generation, which can cause airway epithelial injury and tissue hypoxia, 115 116 as well as formaldehyde exposure similar to that of cigarette smoke. 117 Common carrier solutions such as propylene glycol have been associated with increased airway hyper-reactivity among vape pen users, 31 118 119 and have been associated with chronic respiratory conditions among theater workers exposed to aerosolized propylene glycol used in the generation of artificial fog. 120 Nicotine salts used in pod based vape pen solutions, including Juul, have been found to penetrate the cell membrane and have cytotoxic effects. 121

The myriad available vape pen flavors correlate with an expansive list of chemical compounds with potential adverse respiratory effects. Flavorants have come under increased scrutiny in recent years and have been found to contribute to the majority of aldehyde production during vape aerosol production. 122 Compounds such as cinnamaldehyde, 123 124 2,5-dimethylpyrazine (chocolate flavoring), 125 and 2,3-pentanedione 126 are common flavor additives and have been found to contribute to airway inflammation and altered immunological responses. The flavorant diacetyl garnered particular attention after it was identified on mass spectrometry in most vape solutions tested. 127 Diacetyl is most widely associated with an outbreak of diacetyl associated bronchiolitis obliterans (“popcorn lung”) among workers at a microwave popcorn plant in 2002. 128 Identification of diacetyl in vape solutions raises the possibility of development of a similar pattern of bronchiolitis obliterans among individuals who have chronic vape aerosol exposure to diacetyl-containing vape solutions. 129

Studies of vape aerosols have suggested multiple pro-inflammatory effects on the respiratory system. This includes increased airway resistance, 130 impaired response to infection, 131 and impaired mucociliary clearance. 132 Vape aerosols have further been found to induce oxidative stress in lung epithelial cells, 133 and to both induce DNA damage and impair DNA repair, consistent with a potential carcinogenic effect. 134 Mice chronically exposed to vape aerosols developed increased airway hyper-reactivity and parenchymal changes consistent with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 135 Human studies have been more limited, but reveal increased airway edema and friability among vape pen users, as well as altered gene transcription and decreased innate immunity. 136 137 138 Upregulation of neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloproteases among vape users suggests increased proteolysis, potentially putting those patients at risk of chronic respiratory conditions. 139

THC-containing products

Of particular interest during the 2019 EVALI outbreak was the high prevalence of THC use among EVALI cases, 19 raising questions about a novel mechanism of lung injury specific to THC-containing vape solutions. These solutions differ from conventional nicotine based products because of the need for a carrier capable of emulsifying the lipid based THC component. In this context, additional vape solution ingredients rose to attention as potential culprits—namely, THC itself, which has been found to degrade to methacrolein and benzene, 140 as well as vitamin E acetate which was found to be a common oil based diluent. 141

Vitamin E acetate has garnered increasing attention as a potential culprit in the pathophysiology of the EVALI outbreak. Vitamin E acetate was found in 94% of BAL samples collected from EVALI patients, compared with none identified in unaffected vape pen users. 96 Thermal degradation of vitamin E acetate under conditions similar to those in THC vape pens has shown production of ketene, alkene, and benzene, which may mediate epithelial lung injury when inhaled. 39 Previous work had found that vitamin E acetate impairs pulmonary surfactant function, 142 and subsequent studies have shown a dose dependent adverse effect on lung parenchyma by vitamin E acetate, including toxicity to type II pneumocytes, and increased inflammatory cytokines. 143 Mice exposed to aerosols containing vitamin E acetate developed LLM and increased alveolar protein content, suggesting epithelial injury. 140 143

The pathophysiological insult underlying vaping related lung injury may be multitudinous, including potentially compound effects from multiple ingredients comprising a vape aerosol. The heterogeneity of available vape solutions on the market further complicates efforts to pinpoint particular elements of the vape aerosol that may be pathogenic, as no two users are likely to be exposed to the same combination of vape solution products. Further, vape users may be exposed to vape solutions containing terpenes, medium chain triglycerides, or coconut oil, the effects of which on respiratory epithelium remain under investigation. 144

Lipid laden macrophages

Lipid laden alveolar macrophages have risen to prominence as potential markers of vaping related lung injury. Alveolar macrophages describe a scavenger white blood cell responsible for clearing alveolar spaces of particulate matter and modulating the inflammatory response in the lung parenchyma. 145 LLM describe alveolar macrophages that have phagocytosed fat containing deposits, as seen on Oil Red O staining, and have been described in a wide variety of pulmonary conditions, including aspiration, lipoid pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, and medication induced pneumonitis. 146 147 During the EVALI outbreak, LLM were identified in the alveolar spaces of affected patients, both in the BAL fluid and on both transbronchial and surgical lung biopsies. 148 149 Of 52 EVALI cases reported in the literature who underwent BAL, LLM were identified in over 80%. 19 100 101 148 149 150 151 152 153 Accordingly, attention turned to LLM as not only a potential marker of lung injury in EVALI, but as a possible contributor to lung inflammation itself. This concern was compounded by the frequent reported use of oil based THC vape products among EVALI patients, raising the possibility of lipid deposits in the alveolus resulting from inhalation of THC-containing vape aerosols. 154 The combination of LLM, acute lung injury, and inhalational exposure to an oil based substance raised the concern for exogenous lipoid pneumonia. 152 153 However, further evaluation of the radiographic and histopathologic findings failed to identify cardinal features that would support a diagnosis of exogenous lipoid pneumonia—namely, low attenuation areas on CT imaging and foreign body giant cells on histopathology. 155 156 However, differences in the particle size and distribution between vape aerosol exposure and traditional causes of lipoid pneumonia (ie, aspiration of a large volume of an oil-containing substance), could reasonably lead to differences in radiographic appearance, although this would not account for the lack of characteristic histopathologic features on biopsy that would support a diagnosis of lipoid pneumonia.

Recent work suggests that LLM reflect a non-specific marker of vaping, rather than a marker of lung injury. One study found that LLM were not unique to EVALI and could be identified in healthy vape pen users, as well as conventional cigarette smokers, but not in never smokers. 157 Interestingly, this work showed increased cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 among healthy vape users, suggesting that cigarette and vape pen use are associated with a pro-inflammatory state in the lung. 157 An alternative theory supports LLM presence reflecting macrophage clearance of intra-alveolar cell debris rather than exogenous lipid exposure. 149 150 Such a pattern would be in keeping with the role of alveolar macrophages as modulating the inflammatory response in the lung parenchyma. 158 Taken together, available data would support LLM serving as a non-specific marker of vape product use, rather than playing a direct role in vaping related lung injury pathogenesis. 102

Clinical aspects

A high index of suspicion is required in establishing a diagnosis of vaping related lung injury, and a general approach is summarized in figure 3 . Clinicians may consider the diagnosis when faced with a patient with new respiratory symptoms in the context of vape pen use, without an alternative cause to account for their symptoms. Suspicion should be especially high if respiratory complaints are coupled with constitutional and gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients may present with non-specific markers indicative of an ongoing inflammatory process: fevers, leukocytosis, elevated C reactive protein, or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. 19

Flowchart outlining the procedure for diagnosing a vaping related lung injury

Vaping related lung injury is a diagnosis of exclusion. Chest imaging via radiograph or CT may identify a variety of patterns, although diffuse ground glass opacities remain the most common radiographic finding. Generally, patients with an abnormal chest radiograph should undergo a chest CT for further evaluation of possible vaping related lung injury.

Exclusion of infectious causes is recommended. Testing should include evaluation for bacterial and viral causes of pneumonia, as deemed appropriate by clinical judgment and epidemiological data. Exclusion of common viral causes of pneumonia is imperative, particularly influenza and SARS-CoV-2. Bronchoscopy with BAL should be considered on a case-by-case basis for those with more severe disease and may be helpful to identify patients with vaping mediated eosinophilic lung injury. Further, lung biopsy may be beneficial to exclude alternative causes of lung injury in severe cases. 92

No definitive therapy has been identified for the treatment of vaping related lung injury, and data are limited to case reports and public health guidance on the topic. Management includes supportive care and strong consideration for systemic corticosteroids for severe cases of vaping related lung injury. CDC guidance encourages consideration of systemic corticosteroids for patients requiring admission to hospital, or those with higher risk factors for adverse outcomes, including age over 50, immunosuppressed status, or underlying cardiopulmonary disease. 100 Further, given case reports of vaping mediated acute eosinophilic pneumonia, steroids should be implemented in those patients who have undergone a confirmatory BAL. 77 79

Additional therapeutic options include empiric antibiotics and/or antivirals, depending on the clinical scenario. For patients requiring admission to hospital, prompt subspecialty consultation with a pulmonologist can help guide management. Outpatient follow-up with chest imaging and spirometry is recommended, as well as referral to a pulmonologist. Counseling regarding vaping cessation is also a core component in the post-discharge care for this patient population. Interventions specific to vaping cessation remain under investigation; however, literature supports the use of behavioral counseling and/or pharmacotherapy to support nicotine cessation efforts. 66

Health outcomes among vape pen users

Health outcomes among chronic vape pen users remains an open question. To date, no large scale prospective cohort studies exist that can establish a causal link between vape use and adverse respiratory outcomes. One small scale prospective cohort study did not identify any spirometric or radiographic changes among vape pen users over a 3.5 year period. 159 Given that vaping remains a relatively novel phenomenon, many users will have a less than 10 “pack year” history of vape pen use, arguably too brief an exposure period to reflect the potential harmful nature of chronic vaping. Studies encompassing a longer period of observation of vape pen users have not yet taken place, although advances in electronic medical record (EMR) data collection on vaping habits make such work within reach.

Current understanding of the health effects of vaping is largely limited to case reports of acute lung injury, and health surveys drawing associations between vaping exposure and patient reported outcomes. Within these limitations, however, early work suggests a correlation between vape pen use and poorer cardiopulmonary outcomes. Survey studies of teens who regularly vape found increased frequencies of respiratory symptoms, including productive cough, that were independent of smoking status. 160 161 These findings were corroborated in a survey series identifying more severe asthma symptoms and more days of school missed owing to asthma among vape pen users, regardless of cigarette smoking status. 162 163 164 Studies among adults have shown a similar pattern, with increased prevalence of chronic respiratory conditions (ie, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) among vape pen users, 165 166 and higher risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, but lower risk of diabetes. 167

The effects of vaping on lung function as determined by spirometric studies are more varied. Reported studies have assessed lung function after a brief exposure to vape aerosols, varying from 5-60 minutes in duration, and no longer term observational cohort studies exist. While some studies have shown increased airway resistance after vaping exposure, 130 168 169 others have shown no change in lung function. 137 170 171 The cumulative exposure of habitual vape pen users to vape aerosols is much longer than the period evaluated in these studies, and the impact of vaping on longer term respiratory heath remains to be seen. Recent work evaluating ventilation-perfusion matching among chronic vapers compared with healthy controls found increased ventilation-perfusion mismatch, despite normal spirometry in both groups. 172 Such work reinforces the notion that changes in spirometry are a feature of more advanced airways disease, and early studies, although inconsistent, may foreshadow future respiratory impairment in chronic vapers.

Covid-19 and vaping

The covid-19 pandemic brought renewed attention to the potential health impacts of vaping. Studies investigating the role of vaping in covid-19 prevalence and outcomes have been limited by the small size of the populations studied and results have been inconsistent. Early work noted a geographic association in the US between vaping prevalence and covid-19 cases, 173 and a subsequent survey study found that a covid-19 diagnosis was five times more likely among teens who had ever vaped. 174 In contrast, a UK survey study found no association between vaping status and covid-19 infection rates, although captured a much smaller population of vape pen users. 175 Reports of nicotine use upregulating the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor, 176 which serves as the binding site for SARS-CoV-2 entry, raised the possibility of increased susceptibility to covid-19 among chronic nicotine vape pen users. 177 178 Further, vape use associated with sharing devices and frequent touching of the mouth and face were posited as potential confounders contributing to increased prevalence of covid-19 in this population. 179

Covid-19 outcomes among chronic vape pen users remain an open question. While smoking has been associated with progression to more severe infections, 180 181 no investigation has been performed to date among vaping cohorts. The young average age of chronic vape pen users may prove a protective factor, as risk of severe covid-19 infection has been shown to increase with age. 182 Regardless, a prudent recommendation remains to abstain from vaping to mitigate risk of progression to severe covid-19 infection. 183

Increased awareness of respiratory health brought about by covid-19 and EVALI is galvanizing the changing patterns in vape pen use. 184 Survey studies have consistently shown trends toward decreasing use among adolescents and young adults. 174 185 186 In one study, up to two thirds of participants endorsed decreasing or quitting vaping owing to a combination of factors including difficulty purchasing vape products during the pandemic, concerns about vaping effects on lung health, and difficulty concealing vape use while living with family. 174 Such results are reflected in nationwide trends that show halting growth in vaping use among high school students. 8 These trends are encouraging in that public health interventions countering nicotine use among teens may be meeting some measure of success.

Clinical impact—collecting and recording a vaping history

Vaping history in electronic medical records.

Efforts to prevent, diagnose, and treat vaping related lung injury begin with the ability of our healthcare system to identify vape users. Since vaping related lung injury remains a diagnosis of exclusion, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion when confronted with idiopathic lung injury in a patient with vaping exposure. Unlike cigarette use, vape pen use is not built into most EMR systems, and is not included in meaningful use criteria for EMRs. 187 Retrospective analysis of outpatient visits showed that a vaping history was collected in less than 0.1% of patients in 2015, 188 although this number has been increasing. 189 190 In part augmented by EMR frameworks that prompt collection of data on vaping history, more recent estimates indicate that a vaping history is being collected in up to 6% of patients. 191 Compared with the widespread use of vaping, particularly among adolescent and young adult populations, this number remains low. Considering generational trends in nicotine use, vaping will likely eventually overcome cigarettes as the most common mode of nicotine use, raising the importance of collecting a vaping related history. Further, EMR integration of vaping history is imperative to allow for retrospective, large scale analyses of vape exposure on longitudinal health outcomes at a population level.

Practical considerations—gathering a vaping history

As vaping becomes more common, the clinician’s ability to accurately collect a vaping history and identify patients who may benefit from nicotine cessation programs becomes more important. Reassuringly, gathering a vaping history is not dissimilar to asking about smoking and use of other tobacco products, and is summarized in box 2 . Collecting a vaping history is of particular importance for providers caring for adolescents and young adults who are among the highest risk demographics for vape pen use. Adolescents and young adults may be reluctant to share their vaping history, particularly if they are using THC-containing or CBD-containing vape solutions. Familiarity with vernacular terms to describe vaping, assuming a non-judgmental approach, and asking parents or guardians to step away during history taking will help to break down these barriers. 192

Practical guide to collecting a vaping history

Ask with empathy.

Young adults may be reluctant to share history of vaping use. Familiarity with vaping terminology, asking in a non-judgmental manner, and asking in a confidential space may help.

Ask what they are vaping

Vape products— vape pens commonly contain nicotine or an alternative active ingredient, such as THC or CBD. Providers may also inquire about flavorants, or other vape solution additives, that their patient is consuming, particularly if vaping related lung injury is suspected.

Source— ask where they source their product from. Sources may include commercially available products, third party distributors, or friends or local contacts.

Ask how they are vaping

Device— What style of device are they using?

Frequency— How many times a day do they use their vape pen (with frequent use considered >5 times a day)? Alternatively, providers may inquire how long it takes to deplete a vape solution cartridge (with use of one or more pods a day considered heavy use).

Nicotine concentration— For individuals consuming nicotine-containing products, clinicians may inquire about concentration and frequency of use, as this may allow for development of a nicotine replacement therapy plan.

Ask about other inhaled products

Clinicians should ask patients who vape about use of other inhaled products, particularly cigarettes. Further, clinicians may ask about use of water pipes, heat-not-burn devices, THC-containing products, or dabbing.

The following provides a practical guide on considerations when collecting a vaping history. Of note, collecting a partial history is preferable to no history at all, and simply recording whether a patient is vaping or not adds valuable information to the medical record.

Vape use— age at time of vaping onset and frequency of vape pen use. Vape pen use >5 times a day would be considered frequent. Alternatively, clinicians may inquire how long it takes to deplete a vape solution pod (use of one or more pods a day would be considered heavy use), or how frequently users are refilling their vape pens for refillable models.

Vape products— given significant variation in vape solutions available on the market, and variable risk profiles of the multitude of additives, inquiring as to which products a patient is using may add useful information. Further, clinicians may inquire about use of nicotine versus THC-containing vape solutions, and whether said products are commercially available or are customized by third party sellers.

Concurrent smoking— simultaneous use of multiple inhaled products is common among vape users, including concurrent use of conventional cigarettes, water pipes, heat-not-burn devices, and THC-containing or CBD-containing products. Among those using marijuana products, gathering a history regarding the type of product use, the device, and the modality of aerosol generation may be warranted. Gathering such detailed information may be challenging in the face of rapidly evolving product availability and changing popular terminology. Lastly, clinicians may wish to inquire about “dabbing”—the practice of inhaling heated butane hash oil, a concentrated THC wax—which may also be associated with lung injury. 193

Future directions

Our understanding of the effects of vaping on respiratory health is in its early stages and multiple trials are under way. Future work requires enhanced understanding of the effects of vape aerosols on lung biology, such as ongoing investigations into biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation among vape users (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03823885 ). Additional studies seek to elucidate the relation between vape aerosol exposure and cardiopulmonary outcomes among vape pen users ( NCT03863509 , NCT05199480 ), while an ongoing prospective cohort study will allow for longitudinal assessment of airway reactivity and spirometric changes among chronic vape pen users ( NCT04395274 ).

Public health and policy interventions are vital in supporting both our understanding of vaping on respiratory health and curbing the vaping epidemic among teens. Ongoing, large scale randomized controlled studies seek to assess the impact of the FDA’s “The Real Cost” advertisement campaign for vaping prevention ( NCT04836455 ) and another trial is assessing the impact of a vaping prevention curriculum among adolescents ( NCT04843501 ). Current trials are seeking to understand the potential for various therapies as tools for vaping cessation, including nicotine patches ( NCT04974580 ), varenicline ( NCT04602494 ), and text message intervention ( NCT04919590 ).

Finally, evaluation of vaping as a potential tool for harm reduction among current cigarette smokers is undergoing further evaluation ( NCT03235505 ), which will add to the body of work and eventually lead to clear policy guidance.

Several guidelines on the management of vaping related lung injury have been published and are summarized in table 1 . 194 195 196 Given the relatively small number of cases, the fact that vaping related lung injury remains a newer clinical entity, and the lack of clinical trials on the topic, guideline recommendations reflect best practices and expert opinion. Further, published guidelines focus on the diagnosis and management of EVALI, and no guidelines exist to date for the management of vaping related lung injury more generally.

Summary of clinical guidelines

- View inline

Conclusions

Vaping has grown in popularity internationally over the past decade, in part propelled by innovations in vape pen design and nicotine flavoring. Teens and young adults have seen the biggest uptake in use of vape pens, which have superseded conventional cigarettes as the preferred modality of nicotine consumption. Despite their widespread popularity, relatively little is known about the potential effects of chronic vaping on the respiratory system, and a growing body of literature supports the notion that vaping is not without risk. The 2019 EVALI outbreak highlighted the potential harms of vaping, and the consequences of long term use remain unknown.

Discussions regarding the potential harms of vaping are reminiscent of scientific debates about the health effects of cigarette use in the 1940s. Interesting parallels persist, including the fact that only a minority of conventional cigarette users develop acute lung injury, yet the health impact of sustained, longitudinal cigarette use is unquestioned. The true impact of vaping on respiratory health will manifest over the coming decades, but in the interval a prudent and time tested recommendation remains to abstain from consumption of inhaled nicotine and other products.

Questions for future research

How does chronic vape aerosol exposure affect respiratory health?

Does use of vape pens affect respiratory physiology (airway resistance, V/Q matching, etc) in those with underlying lung disease?

What is the role for vape pen use in promoting smoking cessation?

What is the significance of pulmonary alveolar macrophages in the pathophysiology of vaping related lung injury?

Are particular populations more susceptible to vaping related lung injury (ie, by sex, demographic, underlying comorbidity, or age)?

Series explanation: State of the Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason they are written predominantly by US authors

Contributors: AJ conceived of, researched, and wrote the piece. She is the guarantor.

Competing interests: I have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: AJ receives consulting fees from DawnLight, Inc for work unrelated to this piece.

Patient involvement: No patients were directly involved in the creation of this article.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. 2014. doi: 10.1037/e510072014-001 .

- Cornelius ME ,

- Loretan CG ,

- Marshall TR

- Fetterman JL ,

- Benjamin EJ ,

- Barrington-Trimis JL ,

- Leventhal AM ,

- Cullen KA ,

- Gentzke AS ,

- Sawdey MD ,

- ↵ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surgeon General’s Advisory on E-cigarette Use Among Youth. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

- Leventhal A ,

- Johnston L ,

- O’Malley PM ,

- Patrick ME ,

- Barrington-Trimis J

- ↵ Foundation for a Smoke-Free World https://www.smokefreeworld.org/published_reports/

- Kaisar MA ,

- Calfee CS ,

- Matthay MA ,

- ↵ Royal College of Physicians (London) & Tobacco Advisory Group. Nicotine without smoke: tobacco harm reduction: a report. 2016. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction

- ↵ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. 2018. doi: 10.17226/24952 OpenUrl CrossRef

- Manigrasso M ,

- Buonanno G ,

- Stabile L ,

- Agnihotri R

- LeBouf RF ,

- Koutrakis P ,

- Christiani DC

- Perrine CG ,

- Pickens CM ,

- Boehmer TK ,

- Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group

- Layden JE ,

- Esposito S ,

- Spindle TR ,

- Eissenberg T ,

- Kendler KS ,

- McCabe SE ,

- ↵ Joseph R. Electric vaporizer. 1930.

- ↵ Gilbert HA. Smokeless non-tobacco cigarette. 1965.

- ↵ An Interview With A 1970’s Vaping Pioneer. Ashtray Blog. 2015 . https://www.ecigarettedirect.co.uk/ashtray-blog/2014/06/favor-cigarette-interview-dr-norman-jacobson.html (2014).

- Benowitz N ,

- ↵ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, & Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes . (National Academies Press (US), 2018).

- ↵ Tolentino J. The Promise of Vaping and the Rise of Juul. The New Yorker . 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/14/the-promise-of-vaping-and-the-rise-of-juul

- ↵ Bowen A, Xing C. Nicotine salt formulations for aerosol devices and methods thereof. 2014.

- Madden DR ,

- McConnell R ,

- Gammon DG ,

- Marynak KL ,

- ↵ Jackler RK, Chau C, Getachew BD, et al. JUUL Advertising Over its First Three Years on the Market. Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Stanford University School of Medicine. 2019. https://tobacco-img.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/21231836/JUUL_Marketing_Stanford.pdf

- Prochaska JJ ,

- ↵ Richtel M, Kaplan S. Juul May Get Billions in Deal With One of World’s Largest Tobacco Companies. The New York Times . 2018.

- ↵ Truth Initiative. Vaping Lingo Dictionary: A guide to popular terms and devices. 2020. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/vaping-lingo-dictionary

- Williams M ,

- Pepper JK ,

- MacMonegle AJ ,

- Nonnemaker JM

- ↵ The Physics of Vaporization. Jupiter Research. 2020. https://www.jupiterresearch.com/physics-of-vaporization/

- Bonnevie E ,

- ↵ National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538680/

- Trivers KF ,

- Phillips E ,

- Stefanac S ,

- Sandner I ,

- Grabovac I ,

- ↵ Knowledge-Action-Change. Burning Issues: The Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction 2020. 2020. https://gsthr.org/resources/item/burning-issues-global-state-tobacco-harm-reduction-2020

- Creamer MR ,

- Park-Lee E ,

- Gorukanti A ,

- Delucchi K ,

- Fisher-Travis R ,

- Halpern-Felsher B

- Amrock SM ,

- ↵ Buy JUUL Products | Shop All JUULpods, JUUL Devices, and Accessories | JUUL. https://www.juul.com/shop

- Schiff SJ ,

- Kechter A ,

- Simpson KA ,

- Ceasar RC ,

- Braymiller JL ,

- Barrington-Trimis JL

- Moustafa AF ,

- Rodriguez D ,

- Audrain-McGovern J

- Berhane K ,

- Stjepanović D ,

- Hitchman SC ,

- Bakolis I ,

- Plurphanswat N

- Warner KE ,

- Cummings KM ,

- ↵ FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint. FDA . 2020 . https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- ↵ Henderson, E. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. 113.

- Hartmann-Boyce J ,

- McRobbie H ,

- Lindson N ,

- Phillips-Waller A ,

- ↵ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Electronic Cigarettes. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/index.htm l

- Patnode CD ,

- Henderson JT ,

- Thompson JH ,

- Senger CA ,

- Fortmann SP ,

- Whitlock EP

- Kmietowicz Z

- ↵ World Health Organization. E-cigarettes are harmful to health. 2020. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-02-2020-e-cigarettes-are-harmful-to-health

- Lachireddy K ,

- Sleiman M ,

- Montesinos VN ,

- Kalkhoran S ,

- Filion KB ,

- Kimmelman J ,

- Eisenberg MJ

- McCauley L ,

- Aoshiba K ,

- Nakamura H ,

- Wiggins A ,

- Hudspath C ,

- Kisling A ,

- Hostler DC ,

- Sommerfeld CG ,

- Weiner DJ ,

- Mantilla RD ,

- Darnell RT ,

- Khateeb F ,

- Agustin M ,

- Yamamoto M ,

- Cabrera F ,

- ↵ Long. Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage Due to Electronic Cigarette Use | A54. CRITICAL CARE CASE REPORTS: ACUTE HYPOXEMIC RESPIRATORY FAILURE/ARDS. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2016.193.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1862

- Ring Madsen L ,

- Vinther Krarup NH ,

- Bergmann TK ,

- Bradford LE ,

- Rebuli ME ,

- Jaspers I ,

- Clement KC ,

- Loughlin CE

- Bonilla A ,

- Alamro SM ,

- Bassett RA ,

- Osterhoudt K ,

- Slaughter J ,

- ↵ Health CO. on S. and. Smoking and Tobacco Use; Electronic Cigarettes. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html (2019).

- ↵ For State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Health Departments | Electronic Cigarettes | Smoking & Tobacco Use | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease/health-departments/index.html (2019).

- ↵ 2019 Lung Injury Surveillance Primary Case Definitions. 2.

- Callahan SJ ,

- Collingridge DS ,

- Armatas C ,

- Heinzerling A ,

- Blount BC ,

- Karwowski MP ,

- Shields PG ,

- Lung Injury Response Laboratory Working Group

- ↵ Government of Canada. Vaping-associated lung illness. 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/vaping-pulmonary-illness.html (2020).

- Marlière C ,

- De Greef J ,

- Casanova GS ,

- Blagev DP ,

- Guidry DW ,

- Grissom CK ,

- Werner AK ,

- Koumans EH ,

- Chatham-Stephens K ,

- Lung Injury Response Mortality Working Group

- Tsirilakis K ,

- Yenduri NJS ,

- Guillerman RP ,

- Anderson B ,

- Serajeddini H ,

- Knipping D ,

- Brasky TM ,

- Pisinger C ,

- Godtfredsen N ,

- Jensen RP ,

- Pankow JF ,

- Strongin RM ,

- Lechasseur A ,

- Altmejd S ,

- Turgeon N ,

- Goessler W ,

- Chaumont M ,

- van de Borne P ,

- Bernard A ,

- Kosmider L ,

- Sobczak A ,

- Aldridge K ,

- Afshar-Mohajer N ,

- Koehler K ,

- Varughese S ,

- Teschke K ,

- van Netten C ,

- Beyazcicek O ,

- Onyenwoke RU ,

- Khlystov A ,

- Samburova V

- Lavrich KS ,

- van Heusden CA ,

- Lazarowski ER ,

- Carson JL ,

- Pawlak EA ,

- Lackey JT ,

- Sherwood CL ,

- O’Sullivan M ,

- Vallarino J ,

- Flanigan SS ,

- LeBlanc M ,

- Kullman G ,

- Simoes EJ ,

- Wambui DW ,

- Vardavas CI ,

- Anagnostopoulos N ,

- Kougias M ,

- Evangelopoulou V ,

- Connolly GN ,

- Behrakis PK

- Sussan TE ,

- Gajghate S ,

- Thimmulappa RK ,

- Hossain E ,

- Perveen Z ,

- Lerner CA ,

- Sundar IK ,

- Garcia-Arcos I ,

- Geraghty P ,

- Baumlin N ,

- Coakley RC ,

- Mascenik T ,

- Staudt MR ,

- Hollmann C ,

- Radicioni G ,

- Coakley RD ,

- Kalathil SG ,

- Bogner PN ,

- Goniewicz ML ,

- Thanavala YM

- Massey JB ,

- Matsumoto S ,

- Traber MG ,

- Ranpara A ,

- Stefaniak AB ,

- Williams K ,

- Fernandez E ,

- Basset-Léobon C ,

- Lacoste-Collin L ,

- Courtade-Saïdi M

- Boland JM ,

- Maddock SD ,

- Cirulis MM ,

- Tazelaar HD ,

- Mukhopadhyay S ,

- Dammert P ,

- Kalininskiy A ,

- Davidson K ,

- Brancato A ,

- Heetderks P ,

- Dicpinigaitis PV ,

- Trachuk P ,

- Suhrland MJ

- Khilnani GC

- Simmons A ,

- Freudenheim JL ,

- Hussell T ,

- Cibella F ,

- Caponnetto P ,

- Schweitzer RJ ,

- Williams RJ ,

- Vindhyal MR ,

- Munguti C ,

- Vindhyal S ,

- Lappas AS ,

- Tzortzi AS ,

- Konstantinidi EM ,

- Antoniewicz L ,

- Brynedal A ,

- Lundbäck M ,

- Ferrari M ,

- Boulay MÈ ,

- Boulet LP ,

- Morissette MC

- Kizhakke Puliyakote AS ,

- Elliott AR ,

- Anderson KM ,

- Crotty Alexander LE ,

- Jackson SE ,

- McAlinden KD ,

- McKelvey K ,

- Patanavanich R ,

- NVSS - Provisional Death Counts for COVID-19 - Executive Summary

- Sokolovsky AW ,

- Hertel AW ,

- Micalizzi L ,

- Klemperer EM ,

- Peasley-Miklus C ,

- Villanti AC

- Henricks WH

- Young-Wolff KC ,

- Klebaner D ,

- Mowery DL ,

- Don’t Forget to Ask

- Stephens D ,

- Siegel DA ,

- Jatlaoui TC ,

- Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group ,

- Ramalingam SS ,

- Schuurmans MM

Essay on Vaping

Students are often asked to write an essay on Vaping in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Vaping

Introduction.

Vaping is a modern trend where people inhale vapor from e-cigarettes. These devices heat a liquid into vapor, which users then inhale.

Popularity of Vaping

Vaping has become popular, especially among teenagers. It’s often seen as a safer alternative to traditional smoking.

Vaping and Health

However, vaping can still harm health. It can lead to lung damage and addiction, as e-cigarettes often contain nicotine.

While vaping is popular and often seen as less harmful than smoking, it’s important to know it can still pose health risks.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on Vaping

250 Words Essay on Vaping

The emergence of vaping.

Vaping, the act of inhaling vapor produced by electronic cigarettes or similar devices, has emerged as a popular alternative to traditional smoking. These devices, often marketed as safer alternatives to cigarettes, have gained significant traction, especially among younger demographics.

Perceived Benefits and Risks

The perceived benefits of vaping include reduced exposure to harmful chemicals compared to traditional smoking and potential assistance in smoking cessation. However, these benefits are contested. The long-term health impacts are still largely unknown, and there’s evidence suggesting that vaping may serve as a gateway to traditional smoking for young people.

Regulation and Public Health

The regulation of vaping products is a contentious issue. Some advocate for stricter regulations to prevent youth access, while others argue for more lenient policies to promote harm reduction among adult smokers. Public health officials grapple with these complexities, striving to balance harm reduction, prevention of youth initiation, and the potential risks of unknown long-term health effects.

Future Implications

The future of vaping is uncertain, with scientific research and policy debates ongoing. It’s clear, however, that the conversation surrounding vaping is a microcosm of larger public health discussions about harm reduction, individual freedom, and the role of regulation in protecting public health. As such, the discourse on vaping serves as an important case study for students of public health, policy, and ethics.

500 Words Essay on Vaping

Vaping, a contemporary phenomenon, has rapidly gained popularity, particularly among young adults and adolescents. It involves inhaling vapor created by an electronic cigarette or other vaping devices. The trend has sparked significant debate due to its potential health implications, societal impact, and its role in nicotine addiction.

Understanding Vaping and Its Appeal

Vaping devices, also known as e-cigarettes, vape pens, or mods, heat a liquid—usually containing nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals—to create an aerosol that users inhale. The appeal of vaping lies primarily in its perceived safer profile compared to traditional smoking. Additionally, the variety of flavors offered by vape companies, from fruit to mint, attracts a younger demographic. The discreet nature of these devices, some of which resemble flash drives or pens, also adds to their appeal.

Health Implications of Vaping

The health effects of vaping are a significant concern. While e-cigarettes are often marketed as safer alternatives to traditional cigarettes, research suggests that they are not without risks. The aerosol users inhale and exhale from e-cigarettes can expose both themselves and bystanders to harmful substances, including heavy metals, volatile organic compounds, and other harmful ingredients.

Furthermore, nicotine, a primary ingredient in most e-cigarettes, is highly addictive and can harm adolescent brain development, which continues into the early to mid-20s. Long-term health effects of vaping remain uncertain due to its relatively recent emergence, but early research indicates potential risks to respiratory and cardiovascular health.

The Societal Impact of Vaping

Beyond individual health risks, vaping has broader societal implications. The rise in vaping, particularly among youth, has been declared an epidemic by public health officials. Schools are struggling to manage the surge in e-cigarette use, and families are grappling with the implications of nicotine addiction.

Moreover, there is a concern that vaping serves as a gateway to traditional smoking, particularly among young people. While some argue that e-cigarettes can aid in smoking cessation, others contend that they may encourage nicotine addiction and transition to more harmful tobacco products.

Regulatory Challenges and Future Directions

Regulating vaping poses significant challenges. The rapid evolution of vaping devices, the variety of substances they can deliver, and their widespread accessibility and appeal to youth make regulatory efforts complex.

Moving forward, comprehensive strategies are needed to tackle the vaping epidemic. These might include tighter regulations on marketing practices targeting youth, public education campaigns about the risks of vaping, and continued research into the long-term health effects of these products.

In conclusion, while vaping is often perceived as a safer alternative to traditional smoking, it is not without risks. The potential health implications, coupled with its societal impact and regulatory challenges, make it a complex and critical public health issue. As such, it is essential for ongoing research, public discourse, and effective policy measures to address this contemporary phenomenon.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Values

- Essay on Value of Time

- Essay on Vaccines

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction Essay

Over the years, the utilization of vaping products has dramatically increased, particularly among youth. With at least 12 deaths and close to 1,000 sickened, vaping, the enormously fashionable alternative for consuming nicotine or perhaps flavorful substances, has unexpectedly been riskier than predicted (Dinardo & Rome, 2019). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that more than 2 million young people smoked e-cigarettes in 2021 (Dinardo & Rome, 2019).

It might have a significant effect if state officials asked the region’s health authority to ban all flavored vape goods in reaction to this issue to safeguard the youth’s well-being (Domenico et al., 2021). A state does have other options in addition to that. The best way to overcome this difficulty is for nations to incorporate free science-based application innovations. While enforcing an immediate ban benefits many parents, incorporating an app is preferable since it immediately communicates with the youth by showing them the negative impacts and ultimately nullifies any possibility of teenagers smoking.

Banning commodities, especially which bring some preconceived pleasures increases the demand for those who want them instead of cutting them. It is correct that banning vapes will have a slight effect as parents will majorly appreciate it, but it would only make the youth go to more extraordinary lengths seeking the vapes, hence imposing a threat more. This solution would work in the short term and involve many state officers and laws to force the action.

Alternatively, using scientifically constructed applications that are freely accessible in any state would have a significant positive effect as it directly communicates with youth. Showcasing the adverse effects of vaping and providing statistical facts in the form of notifications on youth’s phones will, by a majority, cut vape users as they are spoken to intellectually and emotionally. On the other hand, this would work over the long term, which is more profitable for the future generation and the nation’s government.

Therefore, incorporating a scientifically created application solution is the best overall solution and should be integrated into states where vaping is prone. A significant drop will be evident as soon as the government spreads awareness of the new freely accessible application. As many people work now not for themselves but the betterment of future generations, this solution would pose the best course of action in entirely eradicating vaping for the youth soon, with no possibility of newly developing again.

Dinardo, P., & Rome, E. S. (2019). Vaping: The new wave of Nicotine Addiction . Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 86 (12), 789–798. Web.

Domenico, L., DeRemer, C. E., Nichols, K. L., Campbell, C., Moreau, J. R., Childs, G. S., & Merlo, L. J. (2021). Combatting the epidemic of e-cigarette use and vaping among students and transitional-age youth. Current Psychopharmacology, 10 (1), 5–16. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 22). Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teen-vaping-the-new-wave-of-nicotine-addiction/

"Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction." IvyPanda , 22 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/teen-vaping-the-new-wave-of-nicotine-addiction/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction'. 22 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction." November 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teen-vaping-the-new-wave-of-nicotine-addiction/.

1. IvyPanda . "Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction." November 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teen-vaping-the-new-wave-of-nicotine-addiction/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Teen Vaping: The New Wave of Nicotine Addiction." November 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teen-vaping-the-new-wave-of-nicotine-addiction/.

- Vaping and Its Negative Aspects

- Vaping Crisis in Jersey: Pros and Cons

- The Damage of Vaping

- E-Cigarettes Structure and Vaping Effects

- Vaping: Negative Effects and Harm Reduction

- The Prevalence of Vaping Among Youths in Ireland

- Vaping Products Abuse and Health Harms

- Discussion: Vaping and E-Cigarettes

- Laws Regarding Vaping and E-Cigarettes

- The Vaping Ages 13 and Up

- Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers

- Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Canada

- Misconceptions About Addiction

- Why Are Cigarettes Tightly Regulated?

- Episodes of The Business of Drugs Series

- Refer a Patient

- We want to help Call 800-767-4411 or request a screening. Refer a patient

- Free Screening

We are here to help you. Call 800-767-4411 or request a screening >

Your questions about vaping, answered

Share this article: