- Recent changes

- Random page

- View source

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Create account

What was the Third Wave Feminist Movement

Previous DailyHistory articles have discussed the First and Second Wave Feminist Movements. Like Second Wave feminism, Third Wave feminism emerged from some of the failures and conversations left behind from the wave before.

While there were many successes of the first two waves, including voting rights and greater access to reproductive control, Third Wave feminists have argued that these successes primarily benefited white middle-class women. The Third Wave feminists have actively sought to expand the rights of LBTQ and minority women. Mainly, they have been interested in trying to achieve parity with white women.

As is common with any large coalition, group goals need to be broad enough to encompass the desires of the majority of those involved. White, educated women with clout during the First Wave often advanced the need for white women's rights by suggesting they were better educated and equipped to exercise those rights than non-white men and women.

During the Second Wave, the general discussions about reproductive choice were often framed in terms of access to birth control and the right to an abortion for white women. While non-white women were fighting for the right to control reproduction on their own terms, and not to be forcibly sterilized. These rifts were not crippling, but often benefited one faction of a coalition more than the other.

For many non-white feminists during the Second Wave, their experiences as women were inseparable from their experiences as people of color. They could not compartmentalize their lives or experiences. A new wave of feminism needed to address all parts of their identity adequately.

Third Wave Feminism

Leaders of the third wave feminist movement were daughters of the second wave--often literally. They were born in the 1960s and 1970s and came of age in the 1980s and 1990s. They came of age after the Civil Rights movement and benefited from that in many ways--growing up in diverse neighborhoods, attending integrated schools, and seeing representations and contributions of people of color in media and society. Furthermore, these leaders were often the daughters of those who saw society transform because of Second Wave actions and expected their daughters to take advantage of those opportunities.

Third Wave Feminism differed from the first two waves not just goals, but in substance. While the first two waves generally accepted traditional gender identities and norms, the third wave challenged ideas about what was traditionally masculine and traditionally feminine. Not only did Third Wave feminists reject this strict separation and polarity between male and female, but they embraced a more complex and nuanced understanding of opportunities for gender and sexual expression, including identity.

Third Wave feminists took Second Wave feminism's "sexual liberation" one step further by also calling for the exploration and acceptance of a variety of sexual identities. Furthermore, Third Wave Feminists believe it is in their right to seek sexual pleasure on their own terms as well as a sex-positive movement.

Feminism in the Third Wave appropriated previously-insulting and derogatory terms. Third Wave Feminists unapologetically reclaimed words like "bitch" and spoke openly about themselves, their bodies, and their experiences. Third Wave Feminists, whose lives have been saturated with popular culture, are quick to challenge portrayals of women in beauty and in art. Third Wave Feminists see men as their equals and challenge institutions and conventions that dictate otherwise. [1]

Some have argued that Third Wave Feminism is--in part--a rejection of Second Wave Feminism or at least a strong critique against it. If Second Wave Feminism bolstered heterosexual privilege, Third Wave Feminism combats that by supporting the extension of civil rights to LGBT individuals. If Second Wave Feminism was empowering by rejecting conventional beauty ideals, Third Wave Feminism calls for an inclusive definition of beauty that includes a more diverse set of criteria. [2]

At its core, Third Wave Feminism argues that it is more inclusive and accepting of a variety of identities. Third Wave Feminism attempts to wrestle more fully with intersectionality, that is: that race and gender are not "mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis... Those who are multiply-burdened... cannot be understood" through a single lens or source of discrimination. [3] .

Third Wave Feminism does try to check its privilege at the door, it, like its predecessors, still does tend to have a white-middle class leaning. While this has been more openly discussed, it still also remains a point of contention for some feminists in the Third Wave with some feminists calling for toleration and others for more ardent antiracism.

Third Wave Feminism, like its predecessors, embodies a variety of opinions and beliefs and is not limited to just "women's issues;" nevertheless, these issues remained at the core of Third Wave Feminism's discussions.

Fourth Wave Feminism?

Related Articles

- What was the First Wave Feminist Movement?

- What was the Second Wave Feminist Movement?

- When did abortion become legal in the United States?

Some have argued that #MeToo movement, the 2016 Presidential Election, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court and the revelations about how common the sexual assault of women is may have ushered in a Fourth Wave of Feminism. Both sexual assault and harassment have become central issues within the existing movement. Only time will tell if this is an entirely new movement, or if this is simply a continuation of the Third Wave after a dormant period. If this is a new Fourth Wave, it is clearly building on some of the Third Wave but is unique in its focus on sexual harassment and rape culture.

Suggested Reading

- The Women's Movement Today: An Encyclopedia of Third Wave Feminism , ed. Leslie L. Heywood, (Greenwood, 2005)

- Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration , 2nd edition, ed. Stacy Gillis, Gillian Howie, and Rebecca Munford, (Palgrave Mcmillian, 2007)

- ↑ Laura Brunell and Elinor Burkett, "Feminism: Sociology," Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/feminism#ref216004

- ↑ R. Claire Snyder, "What is Third Wave Feminism? A New Directions Essay," Signs 34, 1 (Autumn 2008): 175-196.

- ↑ Kimberle Crenshaw, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics," Unversity of Chicago Legal Forum, vol. 1989, no. 1: 139-167, 139-140.

Admin and Aliciagutierrezromine

- Women's History

- United States History

- 20th Century History

- This page was last edited on 23 September 2021, at 05:37.

- Privacy policy

- About DailyHistory.org

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

Feminism: The Third Wave

FEMINISM : The Third Wave

The Third Wave

Much like the first and second waves, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the third wave of the feminist movement began. However, this resurgence of women’s rights activism is traditionally seen as a response to mainstream second wave feminism. As the third wave started in the 1990s, women’s rights activists longed for a movement that continued the work of their predecessors while addressing their current struggles. In addition, these women wanted to create a mainstream movement that was inclusive of the various challenges women from different races, classes, and gender identities were facing. Image: (L-R) Second Wave feminist Bella Abzug with law professor Anita Hill.

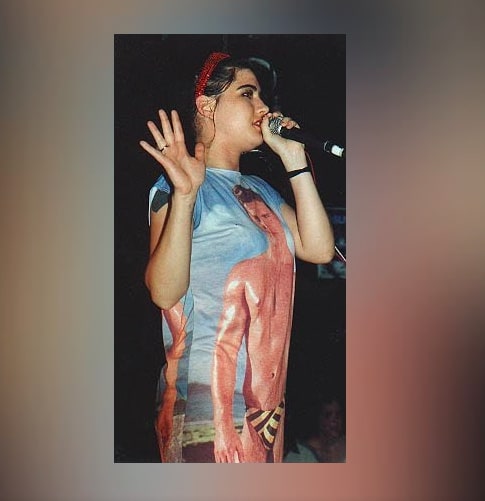

Although it is difficult to isolate the single incident that started the third wave, there are two events that are traditionally credited with inspiring a new generation of women’s rights activists. The first one was the 1991 Anita Hill hearings that sparked national feminist support when Hill testified against a Supreme Court nominee for sexual harassment. While watching the hearings, Rebecca Walker, daughter of second wave icon Alice Walker, began describing the political climate as ”The Third Wave.” In addition, beginning in the 1990s, underground feminist punk rock bands surfaced in “Riot Grrrl” groups. These “girrl” groups combined punk culture with politics, feminism, and style. Both of these occurrences helped to usher the feminist movement into a new era of women’s activism.

Third Wave Literature

Right at the beginning of the third wave, feminist scholars started to publish new literature that helped readers better understand feminist theory. In 1989, lawyer and theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw developed “intersectionality” to show how someone’s various identities (race, class, gender, etc.) overlap to influence how they are treated. This theory led to “intersectional feminism,” that formed as a response to the multiple ways women are oppressed. In 1990, two other revolutionary scholars incorporated the idea of intersectionality into their work. Judith Butler’s “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity” and Patricia Hill Collins’ “Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment” both approach feminist theory by studying women’s social and political identities.

The Anita Hill Hearings

On October 11, 1991, the world watched as attorney Anita Hill testified against U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas for sexual harassment. In the televised hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Hill declared that Thomas had repeatedly harassed her while she was his employee at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. According to Hill, when she worked as his aide, Thomas frequently pressured her to go on dates and often made sexually inappropriate comments during their work conversations. Despite Hill’s testimony, Thomas was still confirmed as a Supreme Court Justice after the three-day hearings.

Although both Thomas and Hill were African American, Thomas believed that the hearing against him was equivalent to a “high tech lynching.” This metaphor suggested that he was being persecuted because of his race. As they both testified before an all-white, all male committee, the history of African American women also being lynched and persecuted was not discussed. Lawyer and author of the ”intersectionality” theory Kimberlé Crenshaw was a member of Hill’s legal team. She later wrote that the belief that lynching was the ultimate symbol of racist terror “erased black women from the picture.” In addition, one of the most prominent historical figures against the lynching of African Americans was a black woman.

National Women's History Museum Women's History Minute: “Ida B. Wells”

After the hearings, African American feminists and historians across the United States came together and collectively raised $50,000 to purchase a full-page ad in the New York Times. Their manifesto entitled, “African American Women in Defense of Ourselves,” was signed by 1,600 women including black feminist historians Barbara Ransby, Deborah King and Elsa Barkley Brown. These women fought against the treatment of Hill during the hearings and stated; “We are particularly outraged by the racist and sexist treatment of Professor Anita Hill, an African American woman who was maligned and castigated for daring to speak publicly of her own experience of sexual abuse.” Following Hill’s story, many other women had the courage to speak out against their own experiences with sexual misconduct.

The Year of the Woman

For many mainstream feminists, the Hill case marked a turning point in women’s activism. Not only were women speaking publicly about sexual assault, but the visibility of the case also caused women to question the male-dominated leadership in Congress. Before the hearings, seven democratic women from the House of Representatives marched over to the Senate to demand a further investigation of the accusations against Thomas. Although he was still confirmed as a justice, feminists began to push for a more active role in political leadership. The very next year, more women were elected to Congress on voting day than in any previous decade. That year became known as “The Year of the Woman,” and 27 women were elected to Congress.

One of the early women’s groups that contributed to the success of The Year of the Woman was “EMILY's List.” This women’s political network provided the fundraising and resources necessary for an endorsed candidate to successfully run for political office. These women used the strategy of raising money early in a candidate’s campaign so it would attract more donors. This principle was the foundation of the organization’s name “EMILY's List” that is an acronym for "Early Money Is Like Yeast,” because yeast “makes the dough rise.” EMILY's List continues to endorse pro-choice Democratic women running for office to this day.

Riot Grrrrl Movement

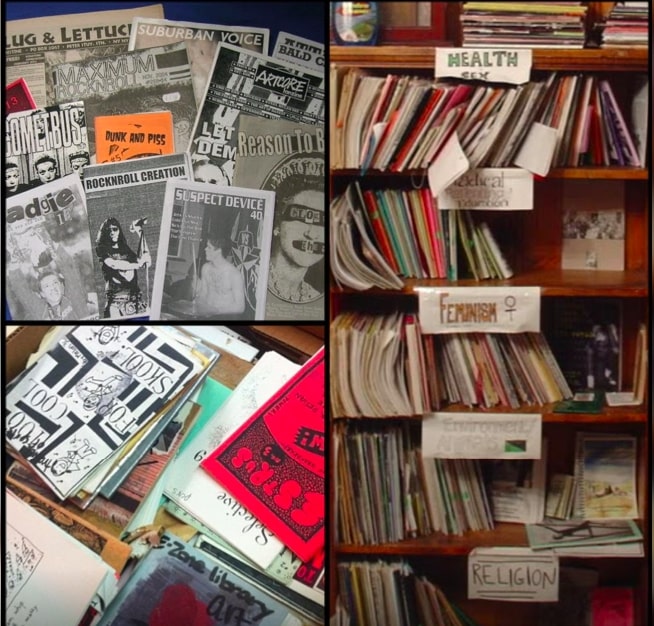

In addition to political affinity groups, punk rock musicians also began to emerge with distinctly feminist agendas. Responding to various forms of sexism, feminist musicians decided to organize a “girl riot” through their activism. These women started their own bands and created their own publications dedicated to women’s empowerment. Much of their content addressed issues including; sexism, patriarchy, abuse, racism, sexuality and rape. Popular bands such as Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy, all lead this trend of activism.

Guerilla Girls

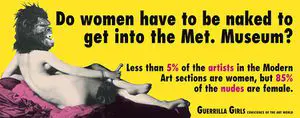

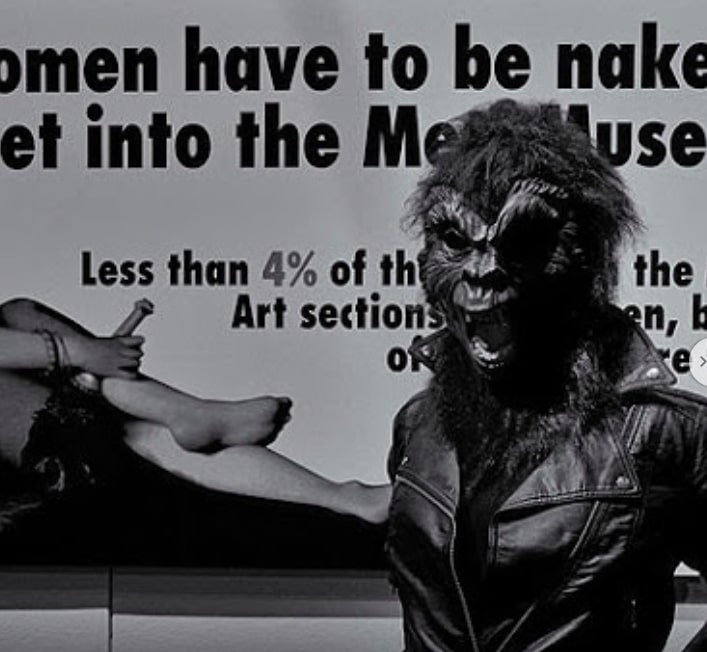

Prior to the evolution of the Riot Grrrl Movement, the Guerrilla Girls set the foundation for radical feminist revolt. They formed in 1985 in response to sexism and racism in the art world. This anonymous group of feminist artists from New York City decided to take the feminist art movement one step further by intentionally disrupting the status quo. These women created posters, billboards, and made public appearances in gorilla masks to reveal the sexist and racist practices in the creation and study of visual art. One of their most famous posters was an image of a naked woman in a gorilla mask next to the phrase “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” The poster also provides the statistics that show the low number of women featured in the Modern Art sections, compared to the high percentage of nude art that features women.

Starting in the early 1990s, radical feminist art seeped into the music world as women affiliated with the Riot Grrrl feminist movement emerged in Olympia, Washington. One of the frontrunners of this movement was Kathleen Hanna, the lead singer of the feminist band Bikini Kill. After collaborating with other Riot Grrrl artists on a small magazine called “Riot Grrrl,” The Bikini Kill Zine (fanzine) was created. These “zines” used punk rock culture to address feminist issues. By 1991, the Bikini Kill Zine published the Riot Grrrl Manifesto that clearly outlined the reasons for this recent surge of feminist activism through music.

Statements from The Riot Grrrl Manifesto, published in 1991 in the Bikini Kill Zine 2:

BECAUSE us girls crave records and books and fanzines that speak to US that WE feel included in and can understand in our own ways.

BECAUSE we wanna make it easier for girls to see/hear each other's work so that we can share strategies and criticize-applaud each other.

BECAUSE we don't wanna assimilate to someone else's (boy) standards of what is or isn’t.

BECAUSE we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.

Many women flocked to these punk rock groups that valued self expression and collective revolt. Kathleen Hanna was known for empowering women at her concerts by shouting “Revolution Girl Style Now!” or “Girls to the front!” to encourage her female attendees to come to the front of the audience. Not only did this provide a safe space for women at rock concerts, but this practice also became a symbol of the call for women to be brought to the forefront in all areas of life. As the movement grew, other Riot Grrrl bands developed across the country and established nationwide chapters. Many of these feminists played their music during pro-choice rallies and advocated for the reproductive rights of women.

By the mid-1990s, Riot Grrrl bands became so well-known that pop culture started to incorporate some of the movement’s terminology. The phrase “Girl Power,” was often used by Bikini Kill and could be found throughout the pages of Riot Grrrl zines. However, this phrase quickly became a pop culture slogan after girl groups like The Spice Girls started promoting a “girl power” theme. Due to the mixed messaging, mainstream media began to attach the political Riot Grrrl groups to pop culture bands that were not associated with the movement. Many Riot Grrrl groups spoke out against this media misrepresentation, but unfortunately it had already become a pop culture phenomenon. In response, several Riot Grrrl groups dissolved. However, many former participants continued to make political music. Even though Bikini Kill released their last album in 1996, lead singer Kathleen Hanna has continued to merge music and activism.

Although the prominence of Riot Grrrl groups was short lived, their specific brand of feminism resonated with many women that may not have identified with the concerns or practices of mainstream “cookie-cutter” feminism. These Riot Grrrl groups inspired radical global activism for decades to come, with Riot Grrrl bands and chapters forming in Asia, Europe, Australia, and Latin America well into the 2000s.

The End of the Third Wave?

As third wave feminists transitioned into the 21st century, it was clear that there were several individualized goals of the movement. Women spoke out in various interest groups about everything including abortion, eating disorders, and sexual assault. However, the Anita Hill hearings and Riot Grrrl groups of the early 1990s were central to the development of this third wave. In 2003, Robin Morgan edited an updated version of her original feminist anthology written in 1970. Her new edition called, “Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium,” featured pieces by both Anita Hill (“The Nature of the Beast: Sexual Harassment”) and Kathleen Hanna of the Riot Grrrl movement (“Gen X Survivor: From Riot Grrrl Rock Star to Feminist Artist”). Some scholars believe that the third wave never came to an end and it continues on to this day. However for others, new technology and social campaigns have marked the beginning of a fourth wave of feminism.

Exhibit written and curated by Kerri Lee Alexander, NWHM Fellow 2018-2020

Adewunmi, Bim. “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality: ‘I Wanted to Come up with an Everyday Metaphor That Anyone Could Use.’” NewStatesman, April 4, 2014. https://www.newstatesman.com/lifestyle/2014/04/kimberl-crenshaw-intersectionality-i-wanted-come-everyday-metaphor-anyone-could.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. “Black Women Still in Defense of Ourselves.” The Nation, October 5, 2011. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/black-women-still-defense-ourselves/.

Feliciano, Stevie. “The Riot Grrrl Movement.” The New York Public Library, June 19, 2013. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2013/06/19/riot-grrrl-movement.

“Guerrilla Girls: 'You Have to Question What You See' .” Tate Modern, October 5, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/guerrilla-girls-6858/guerrilla-girls-interview-tateshots.

Harris-Perry, Melissa. “Where Are All the Black Feminists in Confirmation?” ELLE, April 18, 2016. https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/news/a35699/hbo-confirmation-black-feminists/.

Ryzik, Melena. “A Feminist Riot That Still Inspires.” The New York Times, June 3, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/05/arts/music/the-riot-grrrl-movement-still-inspires.html.

“The Year of the Woman, 1992.” US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Essays/Assembling-Amplifying-Ascending/Women-Decade/.

Walker, Rebecca, Gloria Steinem, and Angela Yvonne Davis. To Be Real: Telling the Truth and Changing the Face of Feminism. New York: Anchor Books, 1995. Pp.250

An Overview of Third-Wave Feminism

- History Of Feminism

- Important Figures

- Women's Suffrage

- Women & War

- Laws & Womens Rights

- Feminist Texts

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Ph.D., Religion and Society, Edith Cowan University

- M.A., Humanities, California State University - Dominguez Hills

- B.A., Liberal Arts, Excelsior College

What historians refer to as "first-wave feminism" arguably began in the late 18th century with the publication of Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), and ended with the ratification of the Twentieth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protected a woman's right to vote. First-wave feminism was concerned primarily with establishing, as a point of policy, that women are human beings and should not be treated like property.

The Second Wave

The second wave of feminism emerged in the wake of World War II , during which many women entered the workforce, and would have arguably ended with the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), had it been ratified. The central focus of the second wave was on total gender equality — women as a group having the same social, political, legal, and economic rights that men have.

Rebecca Walker and the Origins of Third-Wave Feminism

Rebecca Walker, a 23-year-old, Black bisexual woman born in Jackson, Mississippi, coined the term "third-wave feminism" in a 1992 essay. Walker is in many ways a living symbol of the way that second-wave feminism has historically failed to incorporate the voices of many young women, lesbians, bisexual women, and women of color.

Women of Color

Both first-wave and second-wave feminism represented movements that existed alongside, and at times in tension with, civil rights movements for people of color — a slight majority of whom happen to be women. But the struggle always seemed to be for the rights of white women, as represented by the women's liberation movement , and Black men, as represented by the civil rights movement . Both movements, at times, could have been legitimately accused of relegating women of color to asterisk status.

Lesbians and Bisexual Women

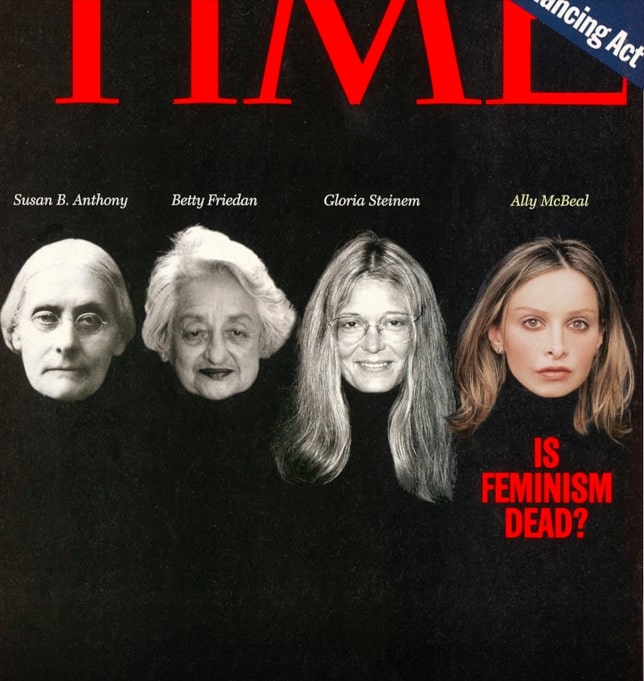

For many second-wave feminists, same gender attracted women were seen as an embarrassment to the movement. The great feminist activist Betty Friedan , for example, coined the term " lavender menace " in 1969 to refer to what she considered the harmful perception that feminists are lesbians. She later apologized for the remark, but it accurately reflected the insecurities of a movement that was still very heteronormative in many ways.

Low-Income Women

First- and second-wave feminism also tended to emphasize the rights and opportunities of middle-class women over poor and working-class women. The debate over abortion rights, for example, centers on laws that affect a woman's right to choose an abortion — but economic circumstances, which generally play a more significant role in such decisions today, are not necessarily taken into account. If a woman has the legal right to terminate her pregnancy, but "chooses" to exercise that right because she can't afford to carry a pregnancy to term, is this really a scenario that protects reproductive rights ?

Women in the Global South

First- and second-wave feminism, as movements, were largely confined to industrialized, Western nations. But third-wave feminism takes a different perspective by giving more platforms to feminist movements all over the world in an effort to show support and international solidarity. It also attempts to attribute knowledge to its original sources by uplifting the voices of women in the Global South, instead of overlooking them or empowering white feminists to steal credit.

A Generational Movement

Some second-wave feminist activists have questioned the need for a third wave. Others, both inside and outside of the movement, disagree with respect to what the third wave represents. Even the general definition provided above may not accurately describe the objectives of all third-wave feminists. But it's important to realize that third-wave feminism is a generational term — it refers to how the feminist struggle manifests itself in the world today. Just as second-wave feminism represented the diverse and sometimes competing for interests of feminists who struggled together under the banner of women's liberation, third-wave feminism represents a generation that has begun with the achievements of the second wave. We can only hope that the third wave will be so successful as to necessitate the fourth wave — and we can only imagine what that fourth wave might look like.

- Feminism in the United States

- Womanist: Definition and Examples

- Goals of the Feminist Movement

- 1970s Feminist Activities

- The Women's Liberation Movement

- Simone de Beauvoir and Second-Wave Feminism

- 10 Important Feminist Beliefs

- The Core Ideas and Beliefs of Feminism

- Feminist Organizations of the 1970s

- Biography of Betty Friedan, Feminist, Writer, Activist

- Top 20 Influential Modern Feminist Theorists

- Lavender Menace: the Phrase, the Group, the Controversy

- Combahee River Collective in the 1970s

- What Is Radical Feminism?

- Abortion on Demand: A Second Wave Feminist Demand

- The Women's Movement and Feminist Activism in the 1960s

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Gender Studies › Third Wave Feminism

Third Wave Feminism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 29, 2017 • ( 2 )

Third wave feminism has numerous definitions, but perhaps is best described in the most general terms as the feminism of a younger generation of women who acknowledge the legacy of second wave feminism , but also identify what they see as its limitations. These perceived limitations would include their sense that it remained too exclusively white and middle class, that it became a prescriptive movement which alienated ordinary women by making them feel guilty about enjoying aspects of individual self-expression such as cosmetics and fashion, but also sexuality – especially heterosexuality and its trappings, such as pornography. Moreover, most third wavers would assert that the historical and political conditions in which second wave feminism emerged no longer exist and therefore it does not chime with the experiences of today’s women. Third wave feminists seem to largely be women who have grown up massively influenced by feminism, possibly with feminist mothers and relations, and accustomed to the existence of women’s studies courses as the norm as well as academic interrogations of ‘race’ and class. These young, mainly university-educated women may well also have encountered post-structuralist and postmodernist theories, so that their approach to staple feminist concepts such as identity and sisterhood will be sceptical and challenging.

According to the conservative critic Rene Denfeld , the third wave was conceived by Rebecca Walker (daughter of the writer Alice Walker) and Shannon Liss in the early 1990s ( Denfeld 1995 : 263), but it seems likely that the term was applied across a number of sources synchronically and, like the second wave, its history is dispersed and caught up with the political tendencies of the age. It is interesting to point out, though, that much of its impetus derives from the writings of women of colour. Most third wave feminists seem to separate their perspectives from so-called ‘ post-feminism ’; as Lesley Heywood and Jennifer Drake assert, ‘Let us be clear: “post-feminist” characterizes a group of young, conservative feminists who explicitly define themselves against and criticize feminists of the second wave’ (1997: 1). They, conversely, seem very conscious of the second wave’s recent history and may well see their work as part of a continuum of feminist radical thought and theorising. This is in opposition to some contemporary commentators on feminism such as Katie Roiphe , whose The Morning After (1994) portrayed US campuses as overrun with misguided feminist radicals exaggerating the dangers of date rape and sexual harassment to the detriment of relationships between men and women – clearly part of the conservative tendency rejected by third wavers.

Naomi Wolf , however, gets a more mixed reception, but her Fire with Fire (1993) in many ways fits the third wave mould, particularly in her dismissal of what she calls ‘victim feminism’ – where women are supposedly encouraged to see themselves rendered passive by oppression within a second wave formulation. Wolf articulates her perspective as part of a generational shift in common with practically all third wave feminism whose genesis is based on a resistance to the ‘old guard’or framed in terms of the need for the ‘daughter’ to break away from her feminist ‘mother’ in order to define her own agenda.

Third wave feminism seems to have emerged from the academy in the loosest sense – that its key spokespeople developed these ideas as a response to their own feminist education – but is equally present in popular cultural forms, as these feminists see their lives as just as powerfully shaped by popular culture, particularly music, television, film and literature. Media figures such as the rock star Courtney Love represent third wave icons in their tendency to refuse to adhere to a feminist party line, but also in their resistance to comply with the types of ‘feminine’ behaviour deemed compatible with media and mainstream success. The Riot Grrrl movement which began around 1991, has close links with the emergence of third wave feminism and illustrates their claim that popular culture can be the site of activism, and that media such as music can be used to communicate political messages. The musical style of Riot Grrrls was heavily influenced by 1970s’ punk and it embraced punk’s inclusivity – the idea that anyone with a passion for music, but perhaps without formal training, could be involved in performance. Their influence soon went beyond the music scene to a broader-based movement – the 1992 Riot Grrrl convention in Washington, DC, for example, had workshops on sexuality, rape, racism and domestic violence (Klein in Heywood and Drake 1997: 214). Examples of Riot Grrl and subsequent third wave activism include making music (not an inconsiderable ambition in an industry famously dominated by men), running record labels, publishing fanzines and setting up cultural events. As all this suggests, being part of feminism’s third wave means realising one’s own politics through the mass media and popular culture – this is diametrically opposed to the ambitions of second wave feminism to keep its ‘authenticity’ by generally shunning the blandishments of the media for fear of being absorbed by patriarchal power structures. Despite the marginal and maverick status of Riot Grrrl performers, there is more generally an investment in women who have made success in a man’s world, using all the usual ‘patriarchal’ indicators of success, such as money, fame, media savvy. The sources for third wave inspiration reflect this cultural multi-lingualism, so that a third wave feminist is as likely to read Mary Wollstonecraft as she is to pick up Elizabeth Wurtzel ’s Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women (1999) or settle down to watch the latest episode of Buffy .

Beyond their cultural tastes, third wavers pride themselves on their global perspective and there is a commitment to look at the material conditions of people’s lives while embracing some of the key tenets of second wave feminism . Men and heterosexuality have a less problematic place in third wave feminism – and their analysis tends to take into account the dispossession of young males as well as females. In the USA in particular, its focus on a certain generation acts as a counterpoise to the characterisation of American generation-Xers as whining and idle.

It is certain that third wave activism is still in its relative infancy and that more academic commentaries will gradually emerge, which will themselves broaden its scope at the same time that they attempt to account for its particular philosophy. Very much at the heart of feminism’s third wave is the sense of generational conflict – one generation claiming its own space and fashioning the movement in its own image – in fact ‘generation X feminism’ is defined by age more than anything else. This marks a very different transition from the first to second waves of feminism, where the shape of political action and feminist purpose was transformed from a discourse of rights to that of liberation. There are hints of good old second wave collective activity in the websites, the zines and the concerts such as Ladyfest (which began in 2000 and are happening across the USA and Europe), but it has a more individualist edge, reflecting among other things a radical suspicion of the politics of identity, and a marked shift to ‘lifestyle’ politics (the idea that your politics said something about your individual taste in the same way that your clothes, furniture and car did – and was in fact part of the ‘package’) evident since the mid-1980s. Of course second wave feminism was itself largely a ‘young’ movement, comprised mainly of women who were in their twenties and thirties during its height, but they have grown old with it and presumably never imagined that its essential message couldn’t be conveyed to a new generation. Catherine Redfern , editor of the web-based The F-Word declares that ‘Second wavers often misunderstand young women’s enthusiasm for the term “third wave”. They think it’s because we don’t respect their achievements or want to disassociate ourselves from them. In actual fact I think it simply demonstrates a desire to feel part of a movement with relevance to our own lives and to claim it for ourselves, to stress that feminism is active today, right now . . . a lot has changed between Gen X and the baby boomers, partly because of the achievements of 70s feminism. Having said that, feminism still has unfinished business’ (Redfern 2002).

Source: Fifty Key Concepts in Gender Studies Jane Pilcher and Imelda Whelehan Sage Publications, 2004.

FURTHER READING Lesley Haywood and Jennifer Drake (1997) offer a lively account of the meanings of third wave feminism to date; Naomi Wolf (1993) is one of the most influential books for this generation of feminists. Because this is a movement that generates intense debate on the web, it is worth looking at some of the sites available, such as ‘The third wave – Feminism for the new millennium’ ( http://www.io.com/~wwwave/ ) or the UK’s ‘The FWord’ ( http://www.thefword.org.uk ).

Share this:

Categories: Gender Studies

Tags: Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women , Buffy , Catherine Redfern , Courtney Love , Elizabeth Wurtzel , Feminism , Fire with Fire , generation X feminism , Jennifer Drake , Katie Roiphe , Kristin Aune , Ladyfest , Lesley Heywood , Leslie Heywood Jennifer Drake , Linguistics , Mary Wollstonecraft , Naomi Wolf , Rebecca Walker , Reclaiming the F Word , Rene Denfeld , Riot Grrrl , Shannon Liss , The F-Word , The Morning After , Third Wave Agenda , Third Wave Feminism

Related Articles

- Postfeminism and Its Entanglement with the Fourth Wave – Literary Theory and Criticism

- Girlhood Studies – Literary Theory and Criticism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Third Wave Feminism

A Critical Exploration

- © 2007

- Latest edition

- Stacy Gillis (Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature) 0 ,

- Gillian Howie (Senior Lecturer in Philosophy) 1 ,

- Rebecca Munford (Lecturer in English Literature) 2

Newcastle University, UK

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

University of Liverpool, UK

Cardiff university, uk.

36k Accesses

188 Citations

10 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (23 chapters)

Front matter, generations and genealogies, ‘feminists love a utopia’.

- Lise Shapiro Sanders

On the Genealogy of Women

- Alison Stone

Kristeva and the Trans-Missions of the Intertext

Feminist dissonance.

- Gillian Howie, Ashley Tauchert

Transgender Feminism

- Susan Stryker

Theorising the Intermezzo

- Amanda D. Lotz

‘You’re Not One of Those Boring Masculinists, Are You?’

- Andrew Shail

Locales and Locations

Wa(i)ving it all away.

- Mridula Nath Chakraborty

‘It’s All About the Benjamins’

- Leslie Heywood, Jennifer Drake

Imagining Feminist Futures

- Niamh Moore

A Different Chronology

- Agnieszka Graff

Global Feminisms, Transnational Political Economies, Third World Cultural Production

- Winifred Woodhull

Neither Cyborg Nor Goddess

Stacy Gillis

Politics and Popular Culture

Contests for the meaning of third wave feminism.

- Ednie Kaeh Garrison

‘Also I Wanted So Much To Leave For the West’

- Anastasia Valassopoulos

(Un)fashionable Feminists

- Kristyn Gorton

About this book

'This expanded second edition of 'Third Wave Feminism' is an unexpected pleasure. While much work on 'the third wave' is ahistorical, nationally-bounded and analytically bankrupt, here the editors bring together an impressive range of articles living up to the volume's subtitle of 'critical exploration'. The anthology provides a historically and conceptually grounded background to the area, highlights the limits as well as possibilities of generational approaches, and constitutes a politically diverse, international set of reflections on the terrain. Essential reading.' - Clare Hemmings, Gender Institute, London School of Economics

'This is an excellent and important book that left me, as Imelda Whelehan puts it at the end of her foreword, "once again caring that I am a feminist, whatever the era.'' - Alice Ridout, Contemporary Women's Writing

Editors and Affiliations

Gillian Howie

Rebecca Munford

About the editors

Bibliographic information.

Book Title : Third Wave Feminism

Book Subtitle : A Critical Exploration

Editors : Stacy Gillis, Gillian Howie, Rebecca Munford

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593664

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan London

eBook Packages : Palgrave Religion & Philosophy Collection , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited 2007

Softcover ISBN : 978-0-230-52174-2 Published: 17 April 2007

eBook ISBN : 978-0-230-59366-4 Published: 17 April 2007

Edition Number : 2

Number of Pages : XXXIV, 310

Topics : Political Philosophy , Social Philosophy , Gender Studies , Feminism

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59085657/GettyImages_120385927.0.jpg)

Filed under:

The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained

If you have no idea which wave of feminism we’re in right now, read this.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained

If one thing’s for sure, it’s that the second-wave feminists are at war with the third-wave feminists.

No, wait, the second-wavers are at war with the fourth-wave feminists.

No, it’s not the second-wavers, it’s the Gen X-ers.

Are we still cool with the first-wavers? Are they all racists now?

Is there actually intergenerational fighting about feminist waves? Is that a real thing?

Do we even use the wave metaphor anymore?

As the #MeToo movement barrels forward, as record numbers of women seek office, and as the Women’s March drives the resistance against the Trump administration, feminism is reaching a level of cultural relevance it hasn’t enjoyed in years. It’s now a major object of cultural discourse — which has led to some very confusing conversations because not everyone is familiar with or agrees on the basic terminology of feminism. And one of the most basic and most confusing terms has to do with waves of feminism.

People began talking about feminism as a series of waves in 1968 when a New York Times article by Martha Weinman Lear ran under the headline “ The Second Feminist Wave .” “Feminism, which one might have supposed as dead as a Polish question, is again an issue,” Lear wrote. “Proponents call it the Second Feminist Wave, the first having ebbed after the glorious victory of suffrage and disappeared, finally, into the sandbar of Togetherness.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10434793/GettyImages_86088464.jpg)

The wave metaphor caught on: It became a useful way of linking the women’s movement of the ’60s and ’70s to the women’s movement of the suffragettes, and to suggest that the women’s libbers weren’t a bizarre historical aberration, as their detractors sneered, but a new chapter in a grand history of women fighting together for their rights. Over time, the wave metaphor became a way to describe and distinguish between different eras and generations of feminism.

It’s not a perfect metaphor. “The wave metaphor tends to have built into it an important metaphorical implication that is historically misleading and not helpful politically,” argued feminist historian Linda Nicholson in 2010 . “That implication is that underlying certain historical differences, there is one phenomenon, feminism, that unites gender activism in the history of the United States, and that like a wave, peaks at certain times and recedes at others. In sum, the wave metaphor suggests the idea that gender activism in the history of the United States has been for the most part unified around one set of ideas, and that set of ideas can be called feminism.”

The wave metaphor can be reductive. It can suggest that each wave of feminism is a monolith with a single unified agenda, when in fact the history of feminism is a history of different ideas in wild conflict.

It can reduce each wave to a stereotype and suggest that there’s a sharp division between generations of feminism, when in fact there’s a fairly strong continuity between each wave — and since no wave is a monolith, the theories that are fashionable in one wave are often grounded in the work that someone was doing on the sidelines of a previous wave. And the wave metaphor can suggest that mainstream feminism is the only kind of feminism there is, when feminism is full of splinter movements.

More from this series

The #MeToo generation gap is a myth

“You just accepted it”: why older women kept silent about sexual harassment — and younger ones are speaking out

Why women are worried about #MeToo

Video: women are not as divided on #MeToo as it may seem

And as waves pile upon waves in feminist discourse, it’s become unclear that the wave metaphor is useful for understanding where we are right now. “I don’t think we are in a wave right now,” gender studies scholar April Sizemore-Barber told Vox in January. “I think that now feminism is inherently intersectional feminism — we are in a place of multiple feminisms.”

But the wave metaphor is also probably the best tool we have for understanding the history of feminism in the US, where it came from and how it developed. And it’s become a fundamental part of how we talk about feminism — so even if we end up deciding to discard it, it’s worth understanding exactly what we’re discarding.

Here is an overview of the waves of feminism in the US, from the suffragettes to #MeToo. This is a broad overview, and it won’t capture every nuance of the movement in each era. Think of it as a Feminism 101 explainer, here to give you a framework to understand the feminist conversation that’s happening right now, how we got here, and where we go next.

The first wave: 1848 to 1920

People have been suggesting things along the line of “Hmmm, are women maybe human beings?” for all of history, so first-wave feminism doesn’t refer to the first feminist thinkers in history. It refers to the West’s first sustained political movement dedicated to achieving political equality for women: the suffragettes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10449045/GettyImages_514900826.jpg)

For 70 years, the first-wavers would march, lecture, and protest, and face arrest, ridicule, and violence as they fought tooth and nail for the right to vote. As Susan B. Anthony’s biographer Ida Husted Harper would put it , suffrage was the right that, once a woman had won it, “would secure to her all others.”

The first wave basically begins with the Seneca Falls convention of 1848 . There, almost 200 women met in a church in upstate New York to discuss “the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.” Attendees discussed their grievances and passed a list of 12 resolutions calling for specific equal rights — including, after much debate, the right to vote.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10434813/GettyImages_517324498.jpg)

The whole thing was organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who were both active abolitionists. (They met when they were both barred from the floor of the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London; no women were allowed.)

At the time, the nascent women’s movement was firmly integrated with the abolitionist movement: The leaders were all abolitionists, and Frederick Douglass spoke at the Seneca Falls Convention, arguing for women’s suffrage. Women of color like Sojourner Truth , Maria Stewart , and Frances E.W. Harper were major forces in the movement, working not just for women’s suffrage but for universal suffrage.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10449095/GettyImages_2001082.jpg)

But despite the immense work of women of color for the women’s movement, the movement of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony eventually established itself as a movement specifically for white women, one that used racial animus as fuel for its work.

The 15th Amendment’s passage in 1870 , granting black men the right to vote, became a spur that politicized white women and turned them into suffragettes. Were they truly not going to be granted the vote before former slaves were?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442527/GettyImages_96796024.jpg)

“If educated women are not as fit to decide who shall be the rulers of this country, as ‘field hands,’ then where’s the use of culture, or any brain at all?” demanded one white woman who wrote in to Stanton and Anthony’s newspaper, the Revolution. “One might as well have been ‘born on the plantation.’” Black women were barred from some demonstrations or forced to walk behind white women in others.

Despite its racism, the women’s movement developed radical goals for its members. First-wavers fought not only for white women’s suffrage but also for equal opportunities to education and employment, and for the right to own property.

And as the movement developed, it began to turn to the question of reproductive rights. In 1916, Margaret Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the US, in defiance of a New York state law that forbade the distribution of contraception. She would later go on to establish the clinic that became Planned Parenthood.

In 1920, Congress passed the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote. (In theory, it granted the right to women of all races, but in practice, it remained difficult for black women to vote , especially in the South.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442577/GettyImages_514881096.jpg)

The 19th Amendment was the grand legislative achievement of the first wave. Although individual groups continued to work — for reproductive freedom, for equality in education and employment, for voting rights for black women — the movement as a whole began to splinter. It no longer had a unified goal with strong cultural momentum behind it, and it would not find another until the second wave began to take off in the 1960s.

Further reading: first-wave feminism

A Vindication of the Rights of Women , Mary Wollstonecraft (1791)

Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions , Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1848)

Ain’t I a Woman? Sojourner Truth (1851)

Criminals, Idiots, Women, and Minors: Is the Classification Sound? A Discussion on the Laws Concerning the Property of Married Women , Frances Power Cobbe (1868)

Remarks by Susan B. Anthony at her trial for illegal voting (1873)

A Room of One’s Own , Virginia Woolf (1929)

Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings , edited by Miriam Schneir (1994)

The second wave: 1963 to the 1980s

The second wave of feminism begins with Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique , which came out in 1963. There were prominent feminist thinkers before Friedan who would come to be associated with the second wave — most importantly Simone de Beauvoir, whose Second Sex came out in France in 1949 and in the US in 1953 — but The Feminine Mystique was a phenomenon. It sold 3 million copies in three years .

The Feminine Mystique rails against “the problem that has no name”: the systemic sexism that taught women that their place was in the home and that if they were unhappy as housewives, it was only because they were broken and perverse. “I thought there was something wrong with me because I didn’t have an orgasm waxing the kitchen floor,” Friedan later quipped .

But, she argued, the fault didn’t truly lie with women, but rather with the world that refused to allow them to exercise their creative and intellectual faculties. Women were right to be unhappy; they were being ripped off.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442663/GettyImages_515575478.jpg)

The Feminine Mystique was not revolutionary in its thinking, as many of Friedan’s ideas were already being discussed by academics and feminist intellectuals. Instead, it was revolutionary in its reach . It made its way into the hands of housewives, who gave it to their friends, who passed it along through a whole chain of well-educated middle-class white women with beautiful homes and families. And it gave them permission to be angry.

And once those 3 million readers realized that they were angry, feminism once again had cultural momentum behind it. It had a unifying goal, too: not just political equality, which the first-wavers had fought for, but social equality.

“The personal is political,” said the second-wavers. (The phrase cannot be traced back to any individual woman but was popularized by Carol Hanisch .) They would go on to argue that problems that seemed to be individual and petty — about sex, and relationships, and access to abortions, and domestic labor — were in fact systemic and political, and fundamental to the fight for women’s equality.

So the movement won some major legislative and legal victories: The Equal Pay Act of 1963 theoretically outlawed the gender pay gap; a series of landmark Supreme Court cases through the ’60s and ’70s gave married and unmarried women the right to use birth control; Title IX gave women the right to educational equality; and in 1973, Roe v. Wade guaranteed women reproductive freedom.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10449255/GettyImages_50542207.jpg)

The second wave worked on getting women the right to hold credit cards under their own names and to apply for mortgages. It worked to outlaw marital rape, to raise awareness about domestic violence and build shelters for women fleeing rape and domestic violence. It worked to name and legislate against sexual harassment in the workplace.

But perhaps just as central was the second wave’s focus on changing the way society thought about women. The second wave cared deeply about the casual, systemic sexism ingrained into society — the belief that women’s highest purposes were domestic and decorative, and the social standards that reinforced that belief — and in naming that sexism and ripping it apart.

The second wave cared about racism too, but it could be clumsy in working with people of color. As the women’s movement developed, it was rooted in the anti-capitalist and anti-racist civil rights movements, but black women increasingly found themselves alienated from the central platforms of the mainstream women’s movement.

The Feminine Mystique and its “problem that has no name” was specifically for white middle-class women: Women who had to work to support themselves experienced their oppression very differently from women who were socially discouraged from working.

Earning the right to work outside the home was not a major concern for black women, many of whom had to work outside the home anyway. And while black women and white women both advocated for reproductive freedom, black women wanted to fight not just for the right to contraception and abortions but also to stop the forced sterilization of people of color and people with disabilities , which was not a priority for the mainstream women’s movement. In response, some black feminists decamped from feminism to create womanism. (“Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender,” Alice Walker wrote in 1983 .)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10449281/GettyImages_634778694.jpg)

Even with its limited scope, second-wave feminism at its height was plenty radical enough to scare people — hence the myth of the bra burners. Despite the popular story, there was no mass burning of bras among second-wave feminists .

But women did gather together in 1968 to protest the Miss America pageant and its demeaning, patriarchal treatment of women. And as part of the protest, participants ceremoniously threw away objects that they considered to be symbols of women’s objectification, including bras and copies of Playboy.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442707/GettyImages_515301968.jpg)

That the Miss America protest has long lingered in the popular imagination as a bra-burning, and that bra-burning has become a metonym for postwar American feminism, says a lot about the backlash to the second wave that would soon ensue.

In the 1980s, the comfortable conservatism of the Reagan era managed to successfully position second-wave feminists as humorless, hairy-legged shrews who cared only about petty bullshit like bras instead of real problems, probably to distract themselves from the loneliness of their lives, since no man would ever want a ( shudder ) feminist.

“I don’t think of myself as a feminist,” a young woman told Susan Bolotin in 1982 for the New York Times Magazine. “Not for me, but for the guy next door that would mean that I’m a lesbian and I hate men.”

Another young woman chimed in, agreeing. “Look around and you’ll see some happy women, and then you’ll see all these bitter, bitter women,” she said. “The unhappy women are all feminists. You’ll find very few happy, enthusiastic, relaxed people who are ardent supporters of feminism.”

That image of feminists as angry and man-hating and lonely would become canonical as the second wave began to lose its momentum, and it continues to haunt the way we talk about feminism today. It would also become foundational to the way the third wave would position itself as it emerged.

Further reading: second-wave feminism

The Second Sex , Simone de Beauvoir (1949)

The Feminine Mystique , B e tty Fried a n ( 1963)

Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape , Susan Brownmiller (1975)

Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination , Catharine A. MacKinnon (1979)

The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination , Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar (1979)

Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism , bell hooks (1981)

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose , Alice Walker (1983)

Sister Outsider , Audre Lorde (1984)

The third wave: 1991(?) to ????

It is almost impossible to talk with any clarity about the third wave because few people agree on exactly what the third wave is, when it started, or if it’s still going on. “The confusion surrounding what constitutes third wave feminism,” writes feminist scholar Elizabeth Evans , “is in some respects its defining feature.”

But generally, the beginning of the third wave is pegged to two things: the Anita Hill case in 1991, and the emergence of the riot grrrl groups in the music scene of the early 1990s.

In 1991, Anita Hill testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her at work. Thomas made his way to the Supreme Court anyway, but Hill’s testimony sparked an avalanche of sexual harassment complaints , in much the same way that last fall’s Harvey Weinstein accusations were followed by a litany of sexual misconduct accusations against other powerful men.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442739/AP_911011014.jpg)

And Congress’s decision to send Thomas to the Supreme Court despite Hill’s testimony led to a national conversation about the overrepresentation of men in national leadership roles. The following year, 1992, would be dubbed “ the Year of the Woman ” after 24 women won seats in the House of Representatives and three more won seats in the Senate.

And for the young women watching the Anita Hill case in real time, it would become an awakening. “I am not a postfeminism feminist,” declared Rebecca Walker (Alice Walker’s daughter) for Ms. after watching Thomas get sworn into the Supreme Court. “I am the Third Wave.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10452143/AP_920405028.jpg)

Early third-wave activism tended to involve fighting against workplace sexual harassment and working to increase the number of women in positions of power. Intellectually, it was rooted in the work of theorists of the ’80s: Kimberlé Crenshaw , a scholar of gender and critical race theory who coined the term intersectionality to describe the ways in which different forms of oppression intersect; and Judith Butler , who argued that gender and sex are separate and that gender is performative. Crenshaw and Butler’s combined influence would become foundational to the third wave’s embrace of the fight for trans rights as a fundamental part of intersectional feminism.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442753/GettyImages_907803092.jpg)

Aesthetically, the third wave is deeply influenced by the rise of the riot grrrls, the girl groups who stomped their Doc Martens onto the music scene in the 1990s.

“BECAUSE doing/reading/seeing/hearing cool things that validate and challenge us can help us gain the strength and sense of community that we need in order to figure out how bullshit like racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-semitism and heterosexism figures in our own lives,” wrote Bikini Kill lead singer Kathleen Hanna in the Riot Grrrl Manifesto in 1991. “BECAUSE we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.”

The word girl here points to one of the major differences between second- and third-wave feminism. Second-wavers fought to be called women rather than girls : They weren’t children, they were fully grown adults, and they demanded to be treated with according dignity. There should be no more college girls or coeds: only college women, learning alongside college men.

But third-wavers liked being girls. They embraced the word; they wanted to make it empowering, even threatening — hence grrrl . And as it developed, that trend would continue: The third wave would go on to embrace all kinds of ideas and language and aesthetics that the second wave had worked to reject: makeup and high heels and high-femme girliness.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10442825/GettyImages_85618271.jpg)

In part, the third-wave embrace of girliness was a response to the anti-feminist backlash of the 1980s, the one that said the second-wavers were shrill, hairy, and unfeminine and that no man would ever want them. And in part, it was born out of a belief that the rejection of girliness was in itself misogynistic: girliness, third-wavers argued, was not inherently less valuable than masculinity or androgyny.

And it was rooted in a growing belief that effective feminism had to recognize both the dangers and the pleasures of the patriarchal structures that create the beauty standard and that it was pointless to punish and censure individual women for doing things that brought them pleasure.

Third-wave feminism had an entirely different way of talking and thinking than the second wave did — but it also lacked the strong cultural momentum that was behind the grand achievements of the second wave. (Even the Year of Women turned out to be a blip, as the number of women entering national politics plateaued rapidly after 1992.)

The third wave was a diffuse movement without a central goal, and as such, there’s no single piece of legislation or major social change that belongs to the third wave the way the 19th Amendment belongs to the first wave or Roe v. Wade belongs to the second.

Depending on how you count the waves, that might be changing now, as the #MeToo moment develops with no signs of stopping — or we might be kicking off an entirely new wave.

Further reading: third-wave feminism

Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity , Judith Butler (1990)

The Beauty Myth , Naomi Woolf (1991)

“ Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color ,” Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991)

“ The Riot GRRRL Manifesto ,” Kathleen Hanna (1991)

Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women , Susan Faludi (1991)

The Bust Guide to the New Girl Order , edited by Marcelle Karp and Debbie Stoller (1999)

Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics , bell hooks (2000)

Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture , Ariel Levy (2005)

The present day: a fourth wave?

Feminists have been anticipating the arrival of a fourth wave since at least 1986, when a letter writer to the Wilson Quarterly opined that the fourth wave was already building. Internet trolls actually tried to launch their own fourth wave in 2014 , planning to create a “pro-sexualization, pro-skinny, anti-fat” feminist movement that the third wave would revile, ultimately miring the entire feminist community in bloody civil war. (It didn’t work out.)

But over the past few years, as #MeToo and Time’s Up pick up momentum, the Women’s March floods Washington with pussy hats every year, and a record number of women prepare to run for office , it’s beginning to seem that the long-heralded fourth wave might actually be here.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10452169/GettyImages_632364590.jpg)

While a lot of media coverage of #MeToo describes it as a movement dominated by third-wave feminism, it actually seems to be centered in a movement that lacks the characteristic diffusion of the third wave. It feels different.

“Maybe the fourth wave is online,” said feminist Jessica Valenti in 2009 , and that’s come to be one of the major ideas of fourth-wave feminism. Online is where activists meet and plan their activism, and it’s where feminist discourse and debate takes place. Sometimes fourth-wave activism can even take place on the internet (the “#MeToo” tweets), and sometimes it takes place on the streets (the Women’s March), but it’s conceived and propagated online.

As such, the fourth wave’s beginnings are often loosely pegged to around 2008, when Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube were firmly entrenched in the cultural fabric and feminist blogs like Jezebel and Feministing were spreading across the web. By 2013, the idea that we had entered a fourth wave was widespread enough that it was getting written up in the Guardian . “What’s happening now feels like something new again,” wrote Kira Cochrane.

Currently, the fourth-wavers are driving the movement behind #MeToo and Time’s Up, but in previous years they were responsible for the cultural impact of projects like Emma Sulkowicz’s Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight) , in which a rape victim at Columbia University committed to carrying their mattress around campus until the university expelled their rapist.

The trending hashtag #YesAllWomen after the UC Santa Barbara shooting was a fourth-wave campaign, and so was the trending hashtag #StandWithWendy when Wendy Davis filibustered a Texas abortion law. Arguably, the SlutWalks that began in 2011 — in protest of the idea that the way to prevent rape is for women to “stop dressing like sluts” — are fourth-wave campaigns.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10257625/454110136.jpg.jpg)

Like all of feminism, the fourth wave is not a monolith. It means different things to different people. But these tentpole positions that Bustle identified as belonging to fourth-wave feminism in 2015 do tend to hold true for a lot of fourth-wavers; namely, that fourth-wave feminism is queer, sex-positive, trans-inclusive, body-positive, and digitally driven. (Bustle also claims that fourth-wave feminism is anti-misandry, but given the glee with which fourth-wavers across the internet riff on ironic misandry , that may be more prescriptivist than descriptivist on their part.)

And now the fourth wave has begun to hold our culture’s most powerful men accountable for their behavior. It has begun a radical critique of the systems of power that allow predators to target women with impunity.

Further reading: fourth-wave feminism

The Purity Myth , Jessica Valenti (2009)

How to Be a Woman , Caitlin Moran (2012)

Men Explain Things to Me , Rebecca Solnit (2014)

We Should All Be Feminists , Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2014)

Bad Feminist , Roxane Gay (2014)

So is there a generational war between feminists?

As the fourth wave begins to establish itself, and as #MeToo goes on, we’ve begun to develop a narrative that says the fourth wave’s biggest obstacles are its predecessors — the feminists of the second wave.

“The backlash to #MeToo is indeed here,” wrote Jezebel’s Stassa Edwards in January , “and it’s liberal second-wave feminism.”

Writing with a lot less nuance, Katie Way, the reporter who broke the Aziz Ansari story , smeared one of her critics as a “burgundy-lipstick, bad-highlights, second-wave-feminist has-been.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10452341/Image_uploaded_from_iOS_4.jpg)

And there certainly are second-wave feminists pushing a #MeToo backlash. “If you spread your legs because he said ‘be nice to me and I’ll give you a job in a movie’ then I’m afraid that’s tantamount to consent,” second-wave feminist icon Germaine Greer remarked as the accusations about Weinstein mounted, “and it’s too late now to start whingeing about that.” (Greer, who has also said on the record that she doesn’t believe trans women are “real women,” has become something of a poster child for the worst impulses of the second wave. Die a hero or live long enough to become a villain, etc.)

But some of the most prominent voices speaking out against #MeToo, like Katie Roiphe and Bari Weiss , are too young to have been part of the second wave. Roiphe is a Gen X-er who was pushing back against both the second and the third waves in the 1990s and has managed to stick around long enough to push back against the fourth wave today. Weiss, 33, is a millennial. Other prominent #MeToo critics, like Caitlin Flanagan and Daphne Merkin , are old enough to have been around for the second wave but have always been on the conservative end of the spectrum.

“In the 1990s and 2000s, second-wavers were cast as the shrill, militant, man-hating mothers and grandmothers who got in the way of their daughters’ sexual liberation. Now they’re the dull, hidebound relics who are too timid to push for the real revolution,” writes Sady Doyle at Elle . “And of course, while young women have been telling their forebears to shut up and fade into the sunset, older women have been stereotyping and slamming younger activists as feather-headed, boy-crazy pseudo-feminists who squander their mothers’ feminist gains by taking them for granted.”

It is not particularly useful to think of the #MeToo debates as a war between generations of feminists — or, more creepily, as some sort of Freudian Electra complex in action. And the data from our polling shows that these supposed generational gaps largely don’t exist . It is perhaps more useful to think of it as part of what has always been the history of feminism: passionate disagreement between different schools of thought, which history will later smooth out into a single overarching “wave” of discourse (if the wave metaphor holds on that long).

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10452363/GettyImages_633756048.jpg)

The history of feminism is filled with radicals and progressives and liberals and centrists. It’s filled with splinter movements and reactionary counter-movements. That’s part of what it means to be both an intellectual tradition and a social movement, and right now feminism is functioning as both with a gorgeous and monumental vitality. Rather than devouring their own, feminists should recognize the enormous work that each wave has done for the movement, and get ready to keep doing more work.

After all, the past is past. We’re in the middle of the third wave now.

Or is it the fourth?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10452375/GettyImages_907764878.jpg)

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

So, what was the point of John Mulaney’s live Netflix talk show?

Inside the bombshell scandal that prompted two miss usas to step down, macklemore’s anthem for gaza is a rarity: a protest song in an era of apolitical music, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Skip to Content

- Current Contributors

- Submissions

- Call For Papers

Other ways to search:

- Events Calendar

Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Motherhood

At the time when I wrote “Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Motherhood,” I lacked a critical frame for understanding neoliberalism. Instead, my concerns over the ideological reshaping of twenty-first century reproductive lives gravitated towards my dissatisfaction with so-called third wave feminism and its practitioners’ uncritical celebration of “choice.”

My frustration may not have been wholly misplaced. Events of the early twenty-first century reveal that the concept of a third wave may not stand the test of time and, in fact, despite the efforts of stalwart defenders such as Alison Piepmeier, only “dramatizes differences” that do not exist between feminists. Indeed, the Trump administration has re-ignited feminist activism and, in this moment of solidarity against a common foe, current feminist resistance draws on the experience and involvement of feminists of all ages, as seen in The Women’s March, the Indivisible Movement, the SisterSong Collective, and smaller grassroots groups such as GRR! Grandmothers for Reproductive Rights. The conflicts within feminist movement are apparent but do not clearly reflect generational lines. Third wave defenders did not resolve the challenges of intersectional politics nor did they contribute more than other feminists to the ongoing struggle to understand, expose, and dismantle oppression as it is reinvented and reified. It remains to be seen if the wave metaphor is jettisoned or merely replaced by a new wave defined by nostalgia for earlier feminist movement.

In proclaiming a third wave of feminism that was not to be confused with postfeminsm, Rebecca Walker missed the real problem: what bell hooks terms lifestyle feminism. In addition to perpetuating a false drama of intergenerational conflict (that was ageist and played into patriarchal fantasies of cat-fights), those like Walker who espoused the idea of a third wave demonstrated a lack of critical distance on the lifestyle culture they believed they alone were capable of critiquing. Instead, they fed a media and consumer culture-fueled version of women’s empowerment, now reflected in the rise of femvertising ads, rather than offering analysis of structural inequality. Lifestyle feminism has been promoted through the apolitical mantras of “choice” and love for women, affirmations that do not require identification with feminist movement or materialist feminist consciousness.

As I noted above, my essay’s discussion of twenty-first century biopolitics lacked the critical term for neoliberalism; however, in third wave defenders’ celebration of choice I now see a troublesome alignment with its values. During and following the publication of my essay, work by Lisa Duggan, Wendy Brown, and Nancy Fraser contributed to feminist understandings of this economic and political moment. Their work points to how the state privileges the market, and, according to Wendy Brown, citizens are accordingly “interpellated as entrepreneurial actors” practicing agency through self-care. Thus a new morality of what Rickie Solinger calls “good and bad choice-makers” arises in reproductive practices, behaviors, and judgments, simultaneously reflecting and contributing to the biopolitics of neoliberal hegemony. The deceptive promise of empowerment through “choice” replaces meaningful rights-based organizing and coalitions. Angela McRobbie’s analysis of “top girls,” in particular, reveals how those young women whose access to choices (reproductive and otherwise) serve the modern state’s identity (as progressive, permissive, unrepressed) come forward into “luminosity” and cultural approbation, while other women are pushed further into the background. Even without this critical framework my essay “smelled a rat” and anticipated McRobbie’s observation that “Choice is surely, within lifestyle culture, a modality of constraint. The individual is compelled to be the kind of subject who can make the right choices” (19).

Two other critical developments since the publication of my essay require acknowledgment: the academic field of motherhood studies and the reproductive justice movement.

Motherhood Studies responds in part to the new momism described by Douglas and Michaels, whose work informed my essay. Since Adrienne Rich made a distinction between motherhood as a patriarchal institution and mothering as a woman’s potential relationship to her powers of reproduction and children, a wealth of feminist research and theorizing on motherhood has developed. Drawing on social construction theory, motherhood studies has examined motherhood as a political, social, philosophical, economic, and biological phenomenon that is mythologized through hegemonic constructions of natural mothers, maternal instincts, and biological clocks. This is the work now being defined, expanded, and refined by Andrea O’Reilly, who coined the term motherhood studies in 2006 and who founded the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement (MIRCI), which she developed from the former Association for Research on Mothering (ARM) at York University in Canada. MIRCI houses the Journal of Motherhood Initiative ( JMI ) and is partnered with Demeter Press, an independent press dedicated to publishing peer-reviewed scholarship on motherhood, mothering, and reproduction. Scholars in motherhood studies have explored more fully some of the concerns I struggled to identify in my essay: attachment parenting that disproportionately relies on maternal labor; myths of natural mothers and problematic, bioessentialized instinct; and unchallenged pronatalism.