An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Color and psychological functioning: a review of theoretical and empirical work

In the past decade there has been increased interest in research on color and psychological functioning. Important advances have been made in theoretical work and empirical work, but there are also important weaknesses in both areas that must be addressed for the literature to continue to develop apace. In this article, I provide brief theoretical and empirical reviews of research in this area, in each instance beginning with a historical background and recent advancements, and proceeding to an evaluation focused on weaknesses that provide guidelines for future research. I conclude by reiterating that the literature on color and psychological functioning is at a nascent stage of development, and by recommending patience and prudence regarding conclusions about theory, findings, and real-world application.

The past decade has seen enhanced interest in research in the area of color and psychological functioning. Progress has been made on both theoretical and empirical fronts, but there are also weaknesses on both of these fronts that must be attended to for this research area to continue to make progress. In the following, I briefly review both advances and weaknesses in the literature on color and psychological functioning.

Theoretical Work

Background and recent developments.

Color has fascinated scholars for millennia ( Sloane, 1991 ; Gage, 1993 ). Theorizing on color and psychological functioning has been present since Goethe (1810) penned his Theory of Colors , in which he linked color categories (e.g., the “plus” colors of yellow, red–yellow, yellow–red) to emotional responding (e.g., warmth, excitement). Goldstein (1942) expanded on Goethe’s intuitions, positing that certain colors (e.g., red, yellow) produce systematic physiological reactions manifest in emotional experience (e.g., negative arousal), cognitive orientation (e.g., outward focus), and overt action (e.g., forceful behavior). Subsequent theorizing derived from Goldstein’s ideas has focused on wavelength, positing that longer wavelength colors feel arousing or warm, whereas shorter wavelength colors feel relaxing or cool ( Nakashian, 1964 ; Crowley, 1993 ). Other conceptual statements about color and psychological functioning have focused on general associations that people have to colors and their corresponding influence on downstream affect, cognition, and behavior (e.g., black is associated with aggression and elicits aggressive behavior; Frank and Gilovich, 1988 ; Soldat et al., 1997 ). Finally, much writing on color and psychological functioning has been completely atheoretical, focused exclusively on finding answers to applied questions (e.g., “What wall color facilitates worker alertness and productivity?”). The aforementioned theories and conceptual statements continue to motivate research on color and psychological functioning. However, several other promising theoretical frameworks have also emerged in the past decade, and I review these frameworks in the following.

Hill and Barton (2005) noted that in many non-human animals, including primate species, dominance in aggressive encounters (i.e., superior physical condition) is signaled by the bright red of oxygenated blood visible on highly vascularized bare skin. Artificial red (e.g., on leg bands) has likewise been shown to signal dominance in non-human animals, mimicking the natural physiological process ( Cuthill et al., 1997 ). In humans in aggressive encounters, a testosterone surge produces visible reddening on the face and fear leads to pallor ( Drummond and Quay, 2001 ; Levenson, 2003 ). Hill and Barton (2005) posited that the parallel between humans and non-humans present at the physiological level may extend to artificial stimuli, such that wearing red in sport contests may convey dominance and lead to a competitive advantage.

Other theorists have also utilized a comparative approach in positing links between skin coloration and the evaluation of conspecifics. Changizi et al. (2006) and Changizi (2009) contend that trichromatic vision evolved to enable primates, including humans, to detect subtle changes in blood flow beneath the skin that carry important information about the emotional state of the conspecific. Increased red can convey anger, embarrassment, or sexual arousal, whereas increased bluish or greenish tint can convey illness or poor physiological condition. Thus, visual sensitivity to these color modulations facilitates various forms of social interaction. In similar fashion, Stephen et al. (2009) and Stephen and McKeegan (2010) propose that perceivers use information about skin coloration (perhaps particularly from the face, Tan and Stephen, 2012 ) to make inferences about the attractiveness, health, and dominance of conspecifics. Redness (from blood oxygenization) and yellowness (from carotenoids) are both seen as facilitating positive judgments. Fink et al. (2006) and Fink and Matts (2007) posit that the homogeneity of skin coloration is an important factor in evaluating the age, attractiveness, and health of faces.

Elliot and Maier (2012) have proposed color-in-context theory, which draws on social learning, as well as biology. Some responses to color stimuli are presumed to be solely due to the repeated pairing of color and particular concepts, messages, and experiences. Others, however, are presumed to represent a biologically engrained predisposition that is reinforced and shaped by social learning. Through this social learning, color associations can be extended beyond natural bodily processes (e.g., blood flow modulations) to objects in close proximity to the body (e.g., clothes, accessories). Thus, for example, red may not only increase attractiveness evaluations when viewed on the face, but also when viewed on a shirt or dress. As implied by the name of the theory, the physical and psychological context in which color is perceived is thought to influence its meaning and, accordingly, responses to it. Thus, blue on a ribbon is positive (indicating first place), but blue on a piece of meat is negative (indicating rotten), and a red shirt may enhance the attractiveness of a potential mate (red = sex/romance), but not of a person evaluating one’s competence (red = failure/danger).

Meier and Robinson (2005) and Meier (in press ) have posited a conceptual metaphor theory of color. From this perspective, people talk and think about abstract concepts in concrete terms grounded in perceptual experience (i.e., they use metaphors) to help them understand and navigate their social world ( Lakoff and Johnson, 1999 ). Thus, anger entails reddening of the face, so anger is metaphorically described as “seeing red,” and positive emotions and experiences are often depicted in terms of lightness (rather than darkness), so lightness is metaphorically linked to good (“seeing the light”) rather than bad (“in the dark”). These metaphoric associations are presumed to have implications for important outcomes such as morality judgments (e.g., white things are viewed as pure) and stereotyping (e.g., dark faces are viewed more negatively).

For many years it has been known that light directly influences physiology and increases arousal (see Cajochen, 2007 , for a review), but recently theorists have posited that such effects are wavelength dependent. Blue light, in particular, is posited to activate the melanopsin photoreceptor system which, in turn, activates the brain structures involved in sub-cortical arousal and higher-order attentional processing ( Cajochen et al., 2005 ; Lockley et al., 2006 ). As such, exposure to blue light is expected to facilitate alertness and enhance performance on tasks requiring sustained attention.

Evaluation and Recommendations

Drawing on recent theorizing in evolutionary psychology, emotion science, retinal physiology, person perception, and social cognition, the aforementioned conceptualizations represent important advances to the literature on color and psychological functioning. Nevertheless, theory in this area remains at a nascent level of development, and the following weaknesses may be identified.

First, the focus of theoretical work in this area is either extremely specific or extremely general. A precise conceptual proposition such as red signals dominance and leads to competitive advantage in sports ( Hill and Barton, 2005 ) is valuable in that it can be directly translated into a clear, testable hypothesis; however, it is not clear how this specific hypothesis connects to a broader understanding of color–performance relations in achievement settings more generally. On the other end of the spectrum, a general conceptualization such as color-in-context theory ( Elliot and Maier, 2012 ) is valuable in that it offers several widely applicable premises; however, these premises are only vaguely suggestive of precise hypotheses in specific contexts. What is needed are mid-level theoretical frameworks that comprehensively, yet precisely explain and predict links between color and psychological functioning in specific contexts (for emerging developments, see Pazda and Greitemeyer, in press ; Spence, in press ; Stephen and Perrett, in press ).

Second, the extant theoretical work is limited in scope in terms of range of hues, range of color properties, and direction of influence. Most theorizing has focused on one hue, red, which is understandable given its prominence in nature, on the body, and in society ( Changizi, 2009 ; Elliot and Maier, 2014 ); however, other hues also carry important associations that undoubtedly have downstream effects (e.g., blue: Labrecque and Milne, 2012 ; green: Akers et al., 2012 ). Color has three basic properties: hue, lightness, and chroma ( Fairchild, 2013 ). Variation in any or all of these properties could influence downstream affect, cognition, or behavior, yet only hue is considered in most theorizing (most likely because experientially, it is the most salient color property). Lightness and chroma also undoubtedly have implications for psychological functioning (e.g., lightness: Kareklas et al., 2014 ; chroma: Lee et al., 2013 ); lightness has received some attention within conceptual metaphor theory ( Meier, in press ; see also Prado-León and Rosales-Cinco, 2011 ), but chroma has been almost entirely overlooked, as has the issue of combinations of hue, lightness, and chroma. Finally, most theorizing has focused on color as an independent variable rather than a dependent variable; however, it is also likely that many situational and intrapersonal factors influence color perception (e.g., situational: Bubl et al., 2009 ; intrapersonal: Fetterman et al., 2015 ).

Third, theorizing to date has focused primarily on main effects, with only a modicum of attention allocated to the important issue of moderation. As research literatures develop and mature, they progress from a sole focus on “is” questions (“Does X influence Y?”) to additionally considering “when” questions (“Under what conditions does X influence Y and under what conditions does X not influence Y?”). These “second generation” questions ( Zanna and Fazio, 1982 , p. 283) can seem less exciting and even deflating in that they posit boundary conditions that constrain the generalizability of an effect. Nevertheless, this step is invaluable in that it adds conceptual precision and clarity, and begins to address the issue of real-world applicability. All color effects undoubtedly depend on certain conditions – culture, gender, age, type of task, variant of color, etc. – and acquiring an understanding of these conditions will represent an important marker of maturity for this literature (for movement in this direction, see Schwarz and Singer, 2013 ; Tracy and Beall, 2014 ; Bertrams et al., 2015 ; Buechner et al., in press ; Young, in press ). Another, more succinct, way to state this third weakness is that theorizing in this area needs to take context, in all its forms, more seriously.

Empirical Work

Empirical work on color and psychological functioning dates back to the late 19th century ( Féré, 1887 ; see Pressey, 1921 , for a review). A consistent feature of this work, from its inception to the past decade, is that it has been fraught with major methodological problems that have precluded rigorous testing and clear interpretation ( O’Connor, 2011 ). One problem has been a failure to attend to rudimentary scientific procedures such as experimenter blindness to condition, identifying, and excluding color deficient participants, and standardizing the duration of color presentation or exposure. Another problem has been a failure to specify and control for color at the spectral level in manipulations. Without such specification, it is impossible to know what precise combination of color properties was investigated, and without such control, the confounding of focal and non-focal color properties is inevitable ( Whitfield and Wiltshire, 1990 ; Valdez and Mehrabian, 1994 ). Yet another problem has been the use of underpowered samples. This problem, shared across scientific disciplines ( Maxwell, 2004 ), can lead to Type I errors, Type II errors, and inflated effect sizes ( Fraley and Vazire, 2014 ; Murayama et al., 2014 ). Together, these methodological problems have greatly hampered progress in this area.

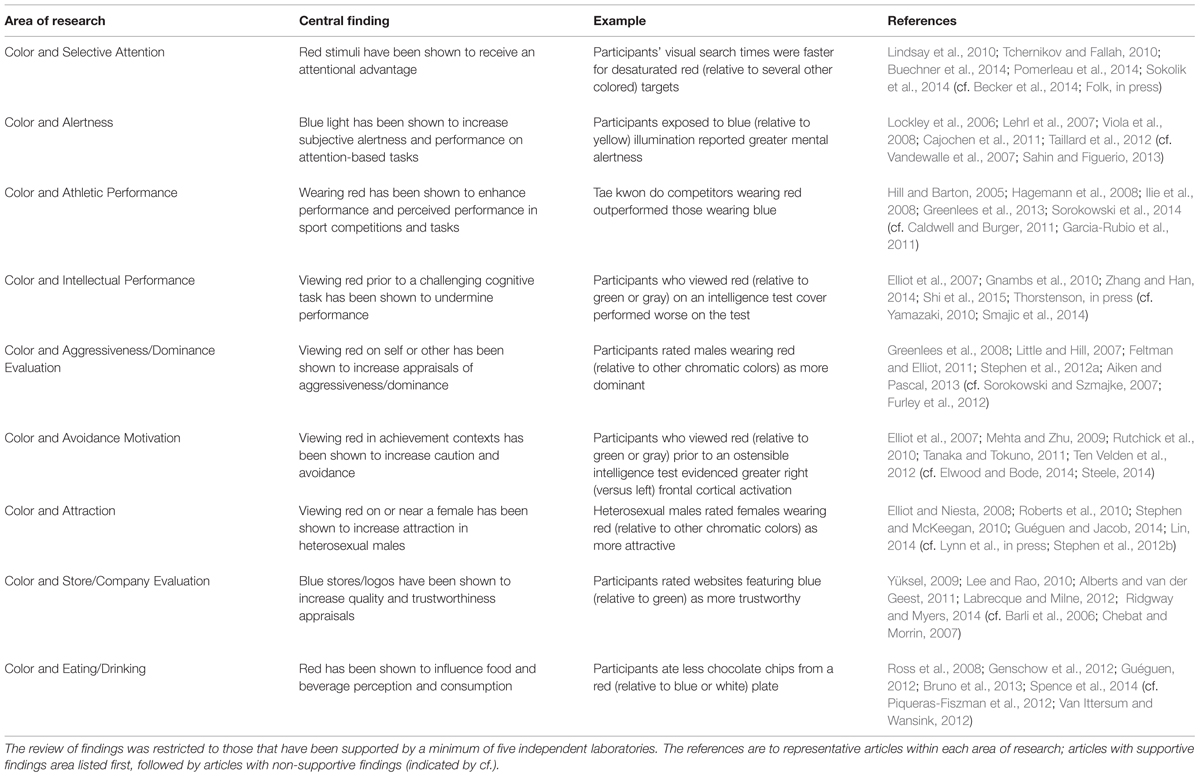

Although some of the aforementioned problems remain (see “Evaluation and Recommendations” below), others have been rectified in recent work. This, coupled with advances in theory development, has led to a surge in empirical activity. In the following, I review the diverse areas in which color work has been conducted in the past decade, and the findings that have emerged. Space considerations require me to constrain this review to a brief mention of central findings within each area. I focus on findings with humans (for reviews of research with non-human animals, see Higham and Winters, in press ; Setchell, in press ) that have been obtained in multiple (at least five) independent labs. Table Table1 1 provides a summary, as well as representative examples and specific references.

Research on color and psychological functioning.

In research on color and selective attention, red stimuli have been shown to receive an attentional advantage (see Folk, in press , for a review). Research on color and alertness has shown that blue light increases subjective alertness and performance on attention-based tasks (see Chellappa et al., 2011 , for a review). Studies on color and athletic performance have linked wearing red to better performance and perceived performance in sport competitions and tasks (see Maier et al., in press , for a review). In research on color and intellectual performance, viewing red prior to a challenging cognitive task has been shown to undermine performance (see Shi et al., 2015 , for a review). Research focused on color and aggressiveness/dominance evaluation has shown that viewing red on self or other increases appraisals of aggressiveness and dominance (see Krenn, 2014 , for a review). Empirical work on color and avoidance motivation has linked viewing red in achievement contexts to increased caution and avoidance (see Elliot and Maier, 2014 , for a review). In research on color and attraction, viewing red on or near a female has been shown to enhance attraction in heterosexual males (see Pazda and Greitemeyer, in press , for a review). Research on color and store/company evaluation has shown that blue on stores/logos increases quality and trustworthiness appraisals (see Labrecque and Milne, 2012 , for a review). Finally, empirical work on color and eating/drinking has shown that red influences food and beverage perception and consumption (see Spence, in press , for a review).

The aforementioned findings represent important contributions to the literature on color and psychological functioning, and highlight the multidisciplinary nature of research in this area. Nevertheless, much like the extant theoretical work, the extant empirical work remains at a nascent level of development, due, in part, to the following weaknesses.

First, although in some research in this area color properties are controlled for at the spectral level, in most research it (still) is not. Color control is typically done improperly at the device (rather than the spectral) level, is impossible to implement (e.g., in web-based platform studies), or is ignored altogether. Color control is admittedly difficult, as it requires technical equipment for color assessment and presentation, as well as the expertise to use it. Nevertheless, careful color control is essential if systematic scientific work is to be conducted in this area. Findings from uncontrolled research can be informative in initial explorations of color hypotheses, but such work is inherently fraught with interpretational ambiguity ( Whitfield and Wiltshire, 1990 ; Elliot and Maier, 2014 ) that must be subsequently addressed.

Second, color perception is not only a function of lightness, chroma, and hue, but also of factors such as viewing distance and angle, amount and type of ambient light, and presence of other colors in the immediate background and general environmental surround ( Hunt and Pointer, 2011 ; Brainard and Radonjić, 2014 ; Fairchild, 2015 ). In basic color science research (e.g., on color physics, color physiology, color appearance modeling, etcetera; see Gegenfurtner and Ennis, in press ; Johnson, in press ; Stockman and Brainard, in press ), these factors are carefully specified and controlled for in order to establish standardized participant viewing conditions. These factors have been largely ignored and allowed to vary in research on color and psychological functioning, with unknown consequences. An important next step for research in this area is to move to incorporate these more rigorous standardization procedures widely utilized by basic color scientists. With regard to both this and the aforementioned weakness, it should be acknowledged that exact and complete control is not actually possible in color research, given the multitude of factors that influence color perception ( Committee on Colorimetry of the Optical Society of America, 1953 ) and our current level of knowledge about and ability to control them ( Fairchild, 2015 ). As such, the standard that must be embraced and used as a guideline in this work is to control color properties and viewing conditions to the extent possible given current technology, and to keep up with advances in the field that will increasingly afford more precise and efficient color management.

Third, although in some research in this area, large, fully powered samples are used, much of the research remains underpowered. This is a problem in general, but it is particularly a problem when the initial demonstration of an effect is underpowered (e.g., Elliot and Niesta, 2008 ), because initial work is often used as a guide for determining sample size in subsequent work (both heuristically and via power analysis). Underpowered samples commonly produce overestimated effect size estimates ( Ioannidis, 2008 ), and basing subsequent sample sizes on such estimates simply perpetuates the problem. Small sample sizes can also lead researchers to prematurely conclude that a hypothesis is disconfirmed, overlooking a potentially important advance ( Murayama et al., 2014 ). Findings from small sampled studies should be considered preliminary; running large sampled studies with carefully controlled color stimuli is essential if a robust scientific literature is to be developed. Furthermore, as the “evidentiary value movement” ( Finkel et al., 2015 ) makes inroads in the empirical sciences, color scientists would do well to be at the leading edge of implementing such rigorous practices as publically archiving research materials and data, designating exploratory from confirmatory analyses, supplementing or even replacing significant testing with “new statistics” ( Cumming, 2014 ), and even preregistering research protocols and analyses (see Finkel et al., 2015 , for an overview).

In both reviewing advances in and identifying weaknesses of the literature on color and psychological functioning, it is important to bear in mind that the existing theoretical and empirical work is at an early stage of development. It is premature to offer any bold theoretical statements, definitive empirical pronouncements, or impassioned calls for application; rather, it is best to be patient and to humbly acknowledge that color psychology is a uniquely complex area of inquiry ( Kuehni, 2012 ; Fairchild, 2013 ) that is only beginning to come into its own. Findings from color research can be provocative and media friendly, and the public (and the field as well) can be tempted to reach conclusions before the science is fully in place. There is considerable promise in research on color and psychological functioning, but considerably more theoretical and empirical work needs to be done before the full extent of this promise can be discerned and, hopefully, fulfilled.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Aiken K. D., Pascal V. J. (2013). Seeing red, feeling red: how a change in field color influences perceptions. Int. J. Sport Soc. 3 107–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Akers A., Barton J., Cossey R., Gainsford P., Griffin M., Micklewright D. (2012). Visual color perception in green exercise: positive effects of mood on perceived exertion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 8661–8666 10.1021/es301685g [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alberts W., van der Geest T. M. (2011). Color matters: color as trustworthiness cue in websites. Tech. Comm. 58 149–160. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barli Ö., Bilgili B., Dane Ş. (2006). Association of consumers’ sex and eyedness and lighting and wall color of a store with price attraction and perceived quality of goods and inside visual appeal. Percept. Motor Skill 103 447–450 10.2466/PMS.103.6.447-450 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker S. I., Valuch C., Ansorge U. (2014). Color priming in pop-out search depends on the relative color of the target. Front. Psychol. 5 : 289 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00289 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bertrams A., Baumeister R. F., Englert C., Furley P. (2015). Ego depletion in color priming research: self-control strength moderates the detrimental effect of red on cognitive test performance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B. 41 311–322 10.1177/0146167214564968 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brainard D. H., Radonjić A. (2014). “Color constancy” in The New Visual Neurosciences , eds Werner J., Chalupa L. (Cambridge, MA; MIT Press; ), 545–556. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruno N., Martani M., Corsini C., Oleari C. (2013). The effect of the color red on consuming food does not depend on achromatic (Michelson) contrast and extends to rubbing cream on the skin. Appetite 71 307–313 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bubl E., Kern E., Ebert D., Bach M., Tebartz van Elst L. (2009). Seeing gray when feeling blue? Depression can be measures in the eye of the diseased. Biol. Psychiat. 68 205–208 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buechner V. L., Maier M. A., Lichtenfeld S., Elliot A. J. Emotion expression and color: their joint influence on perceptions of male attractiveness and social position. Curr. Psychol . (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Buechner V. L., Maier M. A., Lichtenfeld S., Schwarz S. (2014). Red – take a closer look. PLoS ONE 9 : e108111 10.1371/journal.pone.0108111 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cajochen C. (2007). Alerting effects of light. Sleep Med. Rev . 11 453–464 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cajochen C., Frey S., Anders D., Späti J., Bues M., Pross A., et al. (2011). Evening exposure to a light-emitting diodes (LED)-backlit computer screen affects circadian physiology and cognitive performance. J. Appl. Phsysoil. 110 1432–1438 10.1152/japplphysiol.00165.2011 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cajochen C., Münch M., Kobialka S., Kräuchi K., Steiner R., Oelhafen P., et al. (2005). High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 90 1311–1316 10.1210/jc.2004-0957 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caldwell D. F., Burger J. M. (2011). On thin ice: does uniform color really affect aggression in professional hockey? Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2 306–310 10.1177/1948550610389824 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Changizi M. (2009). The Vision Revolution . Dallas, TX: Benbella. [ Google Scholar ]

- Changizi M. A., Zhang Q., Shimojo S. (2006). Bare skin, blood and the evolution of primate colour vision. Biol. Lett. 2 217–221 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0440 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chebat J. C., Morrin M. (2007). Colors and cultures: exploring the effects of mall décor on consumer perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 60 189–196 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.11.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chellappa S. L., Steiner R., Blattner P., Oelhafen P., Götz T., Cajochen C. (2011). Non-visual effects of light on melatonin, alertness, and cognitive performance: can blue-enriched light keep us alert? PLoS ONE 26 : e16429 10.1371/journal.pone.0016429 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Committee on Colorimetry of the Optical Society of America (1953). The Science of Color . Washington, DC: Optical Society of America. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crowley A. E. (1993). The two dimensional impact of color on shopping. Market. Lett. 4 59–69 10.1007/BF00994188 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cumming G. (2014). The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 7–29 10.1177/0956797613504966 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuthill I. C., Hunt S., Cleary C., Clark C. (1997). Color bands, dominance, and body mass regulation in male zebra finches ( Taeniopygia guttata ). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Sci. 264 1093–1099 10.1098/rspb.1997.0151 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drummond P. D., Quay S. H. (2001). The effect of expressing anger on cardiovascular reactivity and facial blood flow in Chinese and Caucasians. Psychophysiology 38 190–196 10.1111/1469-8986.3820190 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Maier M. A. (2012). Color-in-context theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45 61–125 10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00002-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Maier M. A. (2014). Color psychology: effects of perceiving color on psychological functioning in humans. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65 95–120 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115035 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Maier M. A., Moller A. C., Friedman R., Meinhardt J. (2007). Color and psychological functioning: the effect of red on performance attainment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 136 154–168 10.1037/0096-3445.136.1.154 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Niesta D. (2008). Romantic red: red enhances men’s attraction to women. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 95 1150–1164 10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1150 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elwood J. A., Bode J. (2014). Student preferences vis-à-vis teacher feedback in university EFL writing classes in Japan. System 42 333–343 10.1016/j.system.2013.12.023 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairchild M. D. (2013). Color Appearance Models, 3rd Edn New York, NY: Wiley Press; 10.1002/9781118653128 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairchild M. D. (2015). Seeing, adapting to, and reproducing the appearance of nature. Appl. Optics 54 B107–B116 10.1364/AO.54.00B107 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feltman R., Elliot A. J. (2011). The influence of red on perceptions of dominance and threat in a competitive context. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 33 308–314. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fetterman A. K., Liu T., Robinson M. D. (2015). Extending color psychology to the personality realm: interpersonal hostility varied by red preferences and perceptual biases. J. Personal. 83 106–116 10.1111/jopy.12087 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Féré C. (1887). Note sur les conditions physiologiques des émotions. Revue Phil. 24 561–581. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink B., Grammer K., Matts P. J. (2006). Visible skin color distribution plays a role in the perception of age, attractiveness, and health in female faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 27 433–442 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.08.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink B., Matts P. J. (2007). The effects of skin colour distribution and topography cues on the perception of female age and health. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. 22 493–498 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02512.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Finkel E. J., Eastwick P. W., Reis H. T. (2015). Best research practices in psychology: Illustrating epistemological and pragmatic considerations with the case of relationship science. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108 275–297 10.1037/pspi0000007 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Folk C. L. (in press) “The role of color in the voluntary and involuntary guidance of selective attention,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraley R. C., Vazire S. (2014). The N-pact factor: evaluating the quality of empirical journals with respect to sample size and statistical power. PLoS ONE 9 : e109019 10.1371/journal.pone.0109019 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank M. G., Gilovich T. (1988). The dark side of self and social perception: black uniforms and aggression in professional sports. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54 74–85 10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.74 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Furley P., Dicks M., Memmert D. (2012). Nonverbal behavior in soccer: the influence of dominant and submissive body language on the impression formation and expectancy of success of soccer players. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 34 61–82. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gage J. (1993). Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia-Rubio M. A., Picazo-Tadeo A. J., González-Gómez F. (2011). Does a red shirt improve sporting performance? Evidence from Spanish football. Appl. Econ. Lett. 18 1001–1004 10.1080/13504851.2010.520666 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gegenfurtner K. R., Ennis R. (in press) “Fundamentals of color vision II: higher order color processing,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Genschow O., Reutner L., Wänke M. (2012). The color red reduces snack food and soft Drink intake. Appetite 58 699–702 10.1016/j.appet.2011.12.023 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gnambs T., Appel M., Batinic B. (2010). Color red in web-based knowledge testing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26 1625–1631 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goethe W. (1810). Theory of Colors . London: Frank Cass. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldstein K. (1942). Some experimental observations concerning the influence of colors on the function of the organism. Occup. Ther. Rehab. 21 147–151 10.1097/00002060-194206000-00002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenlees I. A., Eynon M., Thelwell R. C. (2013). Color of soccer goalkeepers’ uniforms influences the outcomed of penalty kicks. Percept. Mot. Skill. 116 1–10 10.2466/30.24.PMS.117x14z6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenlees I., Leyland A., Thelwell R., Filby W. (2008). Soccer penalty takers’ uniform color and pre-penalty kick gaze affect the impressions formed of them by opposing goalkeepers. J. Sport Sci. 26 569–576 10.1080/02640410701744446 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guéguen N. (2012). Color and women attractiveness: when red clothed women are perceived to have more intense sexual intent. J. Soc. Psychol. 152 261–265 10.1080/00224545.2011.605398 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guéguen N., Jacob C. (2014). Coffee cup color and evaluation of a beverage’s “warmth quality.” Color Res. Appl. 39 79–81 10.1002/col.21757 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagemann N., Strauss B., Leißing J. (2008). When the referee sees red. Psychol. Sci . 19 769–771 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02155.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higham J. P., Winters S. (in press) “Color and mate choice in non-human animals,” in Handbook of Color Psychology, eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Hill R. A., Barton R. A. (2005). Red enhances human performance in contests. Nature 435 293 10.1038/435293a [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hunt R. W. G., Pointer M. R. (2011). Measuring Colour , 4th Edn New York, NY: Wiley Press; 10.1002/9781119975595 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ilie A., Ioan S., Zagrean L., Moldovan M. (2008). Better to be red than blue in virtual competition. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 11 375–377 10.1089/cpb.2007.0122 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ioannidis J. P. A. (2008). Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology 19 640–648 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson G. M. (in press) “Color appearance phenomena and visual illusions,” in Handbook of Color Psychology, eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Kareklas I., Brunel F. F., Coulter R. A. (2014). Judgment is not color blind: the impact of automatic color preference on product advertising preferences. J. Consum. Psychol. 24 87–95 10.1016/j.jcps.2013.09.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krenn B. (2014). The impact of uniform color on judging tackles in association football. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 15 222–225 10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.11.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuehni R. (2012). Color: An Introduction to Practice and Principles , 3rd Edn New York, NY: Wiley; 10.1002/9781118533567 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Labrecque L. L., Milne G. R. (2012). Exciting red and competent blue: the importance of color in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 40 711–727 10.1007/s11747-010-0245-y [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lakoff G., Johnson M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenges to Western Thought . New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee S., Lee K., Lee S., Song J. (2013). Origins of human color preference for food. J. Food Eng. 119 508–515 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.06.021 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee S., Rao V. S. (2010). Color and store choice in electronic commerce: the explanatory role of trust. J. Electr. Commer. Res. 11 110–126. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrl S., Gerstmeyer K., Jacob J. H., Frieling H., Henkel A. W., Meyrer R., et al. (2007). Blue light improves cognitive performance. J. Neural Trans. 114 457–460 10.1007/s00702-006-0621-4 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levenson R. W. (2003). Blood, sweat, and fears: the automatic architecture of emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 1000 348–366 10.1196/annals.1280.016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin H. (2014). Red-colored products enhance the attractiveness of women. Displays 35 202–205 10.1016/j.displa.2014.05.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindsay D. T., Brown A. M., Reijnen E., Rich A. N., Kuzmova Y. I., Wolfe J. M. (2010). Color channels, not color appearance of color categories, guide visual search for desaturated color targets. Psychol. Sci. 21 1208–1214 10.1177/0956797610379861 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Little A. C., Hill R. A. (2007). Attribution to red suggests special role in dominance signaling. J. Evol. Psychol. 5 161–168 10.1556/JEP.2007.1008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lockley S. W., Evans E. E., Scheer F. A., Brainard G. C., Czeisler C. A., Aeschbach D. (2006). Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep 29 161–168. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lynn M., Giebelhausen M., Garcia S., Li Y., Patumanon I. Clothing color and tipping: an attempted replication and extension. J. Hosp. Tourism Res. doi: 10.1177/1096348013504001. (in press) [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier M. A., Hill R., Elliot A. J., Barton R. A. (in press) “Color in achievement contexts in humans,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell S. (2004). The persistence of underpowered studies in psychological research: causes and consequences. Psychol. Methods 9 147–163 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.147 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mehta R., Zhu R. (2009). Blue or red? Exploring the effect of color on cognitive task performances. Science 323 1226–1229 10.1126/science.1169144 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meier B. P. (in press) “Do metaphors color our perception of social life?,” in Handbook of Color sychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Meier B. P., Robinson M. D. (2005). The metaphorical representation of affect. Metaphor Symbol. 20 239–257 10.1207/s15327868ms2004_1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murayama K., Pekrun R., Fiedler K. (2014). Research practices that can prevent an inflation of false-positive rates. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 18 107–118 10.1177/1088868313496330 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nakashian J. S. (1964). The effects of red and green surroundings on behavior. J. Gen. Psychol. 70 143–162 10.1080/00221309.1964.9920584 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Connor Z. (2011). Colour psychology and colour therapy: caveat emptor. Color Res. Appl. 36 229–334 10.1002/col.20597 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pazda A. D., Greitemeyer T. (in press) “Color in romantic contexts in humans,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Piqueras-Fiszman B., Alcaide J., Roura E., Spence C. (2012). Is it the plate or is it the food? Assessing the influence of the color (black or white) and shape of the plate on the perception of food placed on it. Food Qual. Prefer. 24 205–208 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.08.011 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pomerleau V. J., Fortier-Gauthier U., Corriveau I., Dell’Acqua R., Jolicœur P. (2014). Colour-specific differences in attentional deployment for equiluminant pop-out colours: evidence from lateralized potentials. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 91 194–205 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.10.016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prado-León L. R., Rosales-Cinco R. A. (2011). “Effects of lightness and saturation on color associations in the Mexican population,” in New Directions in Colour Studies , eds Biggam C., Hough C., Kay C., Simmons D. (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Publishing Company; ), 389–394. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pressey S. L. (1921). The influence of color upon mental and motor efficiency. Am. J. Psychol. 32 327–356 10.2307/1413999 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ridgway J., Myers B. (2014). A study on brand personality: consumers’ perceptions of colours used in fashion brand logos. Int. J. Fash. Des. Tech. Educ. 7 50–57 10.1080/17543266.2013.877987 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts S. C., Owen R. C., Havlicek J. (2010). Distinguishing between perceiver and wearer effects in clothing color-associated attributions. Evol. Psychol. 8 350–364. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross C. F., Bohlscheid J., Weller K. (2008). Influence of visual masking technique on the assessment of 2 red wines by trained consumer assessors. J. Food Sci. 73 S279–S285 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00824.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rutchick A. M., Slepian M. L., Ferris B. D. (2010). The pen is mightier than the word: object priming of evaluative standards. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 40 704–708 10.1002/ejsp.753 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sahin L., Figuerio M. G. (2013). Alerting effects of short-wavelength (blue) and long-wavelength (red) lights in the afternoon. Physiol. Behav. 116 1–7 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.03.014 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwarz S., Singer M. (2013). Romantic red revisited: red enhances men’s attraction to young, but not menopausal women. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49 161–164 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Setchell J. (in press) “Color in competition contexts in non-human animals,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Shi J., Zhang C., Jiang F. (2015). Does red undermine individuals’ intellectual performance? A test in China. Int. J. Psychol. 50 81–84 10.1002/ijop.12076 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sloane P. (1991). Primary Sources, Selected Writings on Color from Aristotle to Albers . New York, NY: Design Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smajic A., Merritt S., Banister C., Blinebry A. (2014). The red effect, anxiety, and exam performance: a multistudy examination. Teach. Psychol. 41 37–43 10.1177/0098628313514176 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sokolik K., Magee R. G., Ivory J. D. (2014). Red-hot and ice-cold ads: the influence of web ads’ warm and cool colors on click-through ways. J. Interact. Advert. 14 31–37 10.1080/15252019.2014.907757 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Soldat A. S., Sinclair R. C., Mark M. M. (1997). Color as an environmental processing cue: external affective cues can directly affect processing strategy without affecting mood. Soc. Cogn. 15 55–71 10.1521/soco.1997.15.1.55 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorokowski P., Szmajke A. (2007). How does the “red wins: effect work? The role of sportswear colour during sport competitions. Pol. J. Appl. Psychol. 5 71–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorokowski P., Szmajke A., Hamamura T., Jiang F., Sorakowska A. (2014). “Red wins,” “black wins,” “blue loses” effects are in the eye of the beholder, but they are culturally niversal: a cross-cultural analysis of the influence of outfit colours on sports performance. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 45 318–325 10.2478/ppb-2014-0039 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spence C. (in press) “Eating with our eyes,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Spence C., Velasco C., Knoeferle K. (2014). A large sampled study on the influence of the multisensory environment on the wine drinking experience. Flavour 3 8 10.1186/2044-7248-3-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steele K. M. (2014). Failure to replicate the Mehta and Zhu (2009) color-priming effect on anagram solution times. Psychon. B. Rev. 21 771–776 10.3758/s13423-013-0548-3 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Law Smith M. J., Stirrat M. R., Perrett D. I. (2009). Facial skin coloration affects perceived health of human faces. Int. J. Primatol. 30 845–857 10.1007/s10764-009-9380-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., McKeegan A. M. (2010). Lip colour affects perceived sex typicality and attractiveness of human faces. Perception 39 1104–1110 10.1068/p6730 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Oldham F. H., Perrett D. I., Barton R. A. (2012a). Redness enhances perceived aggression, dominance and attractiveness in men’s faces. Evol. Psychol. 10 562–572. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Scott I. M. L., Coetzee V., Pound N., Perrett D. I., Penton-Voak I. S. (2012b). Cross-cultural effects of color, but not morphological masculinity, on perceived attractiveness of men’s faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 33 260–267 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.10.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Perrett D. I. (in press) “Color and face perception,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Stockman A., Brainard D. H. (in press) “Fundamentals of color vision I: processing in the eye,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Taillard J., Capelli A., Sagaspe P., Anund A., Akerstadt T. (2012). In-car nocturnal blue light exposure improves motorway driving: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 7 : e46750 10.1371/journal.pone.0046750 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan K. W., Stephen I. D. (2012). Colour detection thresholds in faces and colour patches. Perception 42 733–741 10.1068/p7499 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tanaka A., Tokuno Y. (2011). The effect of the color red on avoidance motivation. Soc. Behav. Pers. 39 287–288 10.2224/sbp.2011.39.2.287 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tchernikov I., Fallah M. (2010). A color hierarchy for automatic target selection. PLoS ONE 5 : e9338 10.1371/journal.pone.0009338 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thorstenson C. A. Functional equivalence of the color red and enacted avoidance behavior? Replication and empirical integration. Soc. Psychol. (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy J. L., Beall A. T. (2014). The impact of weather on women’s tendency to wear red pink when at high risk for conception. PLoS ONE 9 : e88852 10.1371/journal.pone.0088852 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ten Velden F. S., Baas M., Shalvi S., Preenen P. T. Y., De Dreu C. K. W. (2012). In competitive interaction displays of red increase actors’ competitive approach and perceivers’ withdrawal. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol . 48 1205–1208 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.04.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Valdez P., Mehrabian A. (1994). Effects of color on emotions. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 123 394–409 10.1037/0096-3445.123.4.394 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Ittersum K., Wansink B. (2012). Plate size and color suggestability, The Deboeuf Illusion’s bias on serving and eating behavior. J. Consum. Res. 39 215–228 10.1086/662615 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandewalle G., Schmidt C., Albouy G., Sterpenich V., Darsaud A., Rauchs G., et al. (2007). Brain responses to violet, blue, and green monochromatic light exposures in humans: prominent role of blue light and the brainstem. PLoS ONE 11 : e1247 10.1371/journal.pone.0001247 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viola A. U., James L. M., Schlangen L. J. M., Dijk D. J. (2008). Blue-enriched white lightin the workplace improves self-reported alertness, performance and sleep quality. Scan. J. Work Environ. Health 34 297–306 10.5271/sjweh.1268 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitfield T. W., Wiltshire T. J. (1990). Color psychology: a critical review. Gen. Soc. Gen. Psychol. 116 385–411. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yamazaki A. K. (2010). An analysis of background-color effects on the scores of a computer-based English test. KES Part II LNI. 6277 630–636 10.1007/978-3-642-15390-7_65 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Young S. The effect of red on male perceptions of female attractiveness: moderationby baseline attractiveness of female faces. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol . (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Yüksel A. (2009). Exterior color and perceived retail crowding: effects on tourists’ shoppingquality inferences and approach behaviors. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tourism 10 233–254 10.1080/15280080903183383 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zanna M. P., Fazio R. H. (1982). “The attitude behavior relation: Moving toward a third generation of research,” in The Ontario Symposium , Vol. 2 eds Zanna M., Higgins E. T., Herman C. (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 283–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang T., Han B. (2014). Experience reverses the red effect among Chinese stockbrokers. PLoS ONE 9 : e89193 10.1371/journal.pone.0089193 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Color Psychology: How Colors Influence the Mind

The psychology of color in persuasion..

Posted August 20, 2014 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

The psychology of color as it relates to persuasion is one of the most interesting—and most controversial—aspects of marketing .

The reason: Most of today’s conversations on colors and persuasion consist of hunches, anecdotal evidence and advertisers blowing smoke about “colors and the mind.”

To alleviate this trend and give proper treatment to a truly fascinating element of human behavior, today we’re going to cover a selection of the most reliable research on color theory and persuasion.

Misconceptions around the psychology of color

Why does color psychology invoke so much conversation, but is backed with so little data?

As research shows , it’s likely because elements such as personal preference, experiences, upbringing, cultural differences, context, etc., often muddy the effect individual colors have on us. So the idea that colors such as yellow or purple are able to evoke some sort of hyper-specific emotion is about as accurate as your standard Tarot card reading.

It’s time to take a look at some research-backed insights on how color plays a role in persuasion.

The Importance of Colors in Branding

First, let’s address branding, which is one of the most important issues relating to color perception and the area where many articles on this subject run into problems.

There have been numerous attempts to classify consumer responses to different individual colors. The truth of the matter is that color is too dependent on personal experiences to be universally translated to specific feelings.

But there are broader messaging patterns to be found in color perceptions. For instance, colors play a fairly substantial role in purchases and branding.

In an appropriately titled study called Impact of Color in Marketing, researchers found that up to 90% of snap judgments made about products can be based on color alone (depending on the product).

And in regards to the role that color plays in branding, results from studies such as The Interactive Effects of Colors show that the relationship between brands and color hinges on the perceived appropriateness of the color being used for the particular brand (in other words, does the color "fit" what is being sold).

The study Exciting Red and Competent Blue also confirms that purchasing intent is greatly affected by colors due to the impact they have on how a brand is perceived. This means that colors influence how consumers view the " personality " of the brand in question (after all, who would want to buy a Harley Davidson motorcycle if they didn’t get the feeling that Harleys were rugged and cool?).

Additional studies have revealed that our brains prefer recognizable brands , which makes color incredibly important when creating a brand identity . It has even been suggested that it is of paramount importance for new brands to specifically target logo colors that ensure differentiation from entrenched competitors (if the competition all uses blue, you'll stand out by using purple).

When it comes to picking the “right” color, research has found that predicting consumer reaction to color appropriateness in relation to the product is far more important than the individual color itself. So, if Harley owners buy the product in order to feel rugged, you could assume that the pink and glitter edition wouldn't sell all that well.

Psychologist and Stanford professor Jennifer Aaker has conducted studies on this very topic via research on Dimensions of Brand Personality , and her studies have found five core dimensions that play a role in a brand’s personality:

(Brands can sometimes cross between two traits, but they are mostly dominated by one. High fashion clothing feels sophisticated, camping gear feels rugged.)

Additional research has shown that there is a real connection between the use of colors and customers’ perceptions of a brand’s personality.

Certain colors do broadly align with specific traits (e.g., brown with ruggedness, purple with sophistication, and red with excitement). But nearly every academic study on colors and branding will tell you that it’s far more important for your brand’s colors to support the personality you want to portray instead of trying to align with stereotypical color associations.

Consider the inaccuracy of making broad statements such as “green means calm.” The context is missing; sometimes green is used to brand environmental issues such as Timberland’s G.R.E.E.N standard , but other times it’s meant to brand financial spaces such as Mint.com .

And while brown may be useful for a rugged appeal (think Saddleback Leather), when positioned in another context brown can be used to create a warm, inviting feeling (Thanksgiving) or to stir your appetite (every chocolate commercial you’ve ever seen).

Bottom line: I can’t offer you an easy, clear-cut set of guidelines for choosing your brand’s colors, but I can assure you that the context you’re working within is an absolutely essential consideration.

It’s the feeling, mood, and image that your brand creates that play a role in persuasion. Be sure to recognize that colors only come into play when they can be used to match a brand’s desired personality (i.e., the use of white to communicate Apple’s love of clean, simple design).

Without this context, choosing one color over another doesn't make much sense, and there is very little evidence to support that "orange" will universally make people purchase a product more often than "silver."

Color Preferences by Gender

Perceived appropriateness may explain why the most popular car colors are white, black, silver and gray … but is there something else at work that explains why there aren’t very many purple power tools?

One of the better studies on this topic is Joe Hallock’s Colour Assignments . Hallock’s data showcases some clear preferences in certain colors across gender .

It’s important to note that one’s environment—and especially cultural perceptions —plays a strong role in dictating color appropriateness for gender, which in turn can influence individual choices. Consider, for instance, this coverage by Smithsonian magazine detailing how blue became the color for boys and pink was eventually deemed the color for girls (and how it used to be the reverse!).

The most notable points included the supremacy of blue across both genders (it was the favorite color for both groups) and the disparity between groups on purple. Women list purple as a top-tier color, but no men list purple as a favorite color. (Perhaps this is why we have no purple power tools, a product largely associated with men?)

Additional research in studies on color perception and color preferences show that when it comes to shades, tints and hues men seem to prefer bold colors while women prefer softer colors. Also, men were more likely to select shades of colors as their favorites (colors with black added), whereas women were more receptive to tints of colors (colors with white added):

Given the starkly different taste preferences shown, it pays to appeal more to men or women if they make up a larger percentage of your ideal buyers.

Color Coordination + Conversions

Debunking the “best” color for conversion rates on websites has recently been a very popular topic (started here and later here ). They make some excellent points, because it is definitely true that there is no single best color for conversions.

The psychological principle known as the Isolation Effect states that an item that "stands out like a sore thumb" is more likely to be remembered. Research clearly shows that participants are able to recognize and recall an item far better (be it text or an image) when it blatantly sticks out from its surroundings.

The studies Aesthetic Response to Color Combinations and Consumer Preferences for Color Combinations also find that while a large majority of consumers prefer color patterns with similar hues, they favor palettes with a highly contrasting accent color.

In terms of color coordination ( as highlighted in this KISSmetrics graphic ), this would mean creating a visual structure consisting of base analogous colors and contrasting them with accent complementary colors (or you can use tertiary colors).

Another way to think of this is to utilize background , base and accent colors to create a hierarchy (as Josh from StudioPress showcases below) on your site that “coaches” customers on which color means take action.

Why this matters: Although you may start to feel like an interior decorator after reading this section, this stuff is actually incredibly important in helping you understand the why behind conversion jumps and slumps. As a bonus, it will help keep you from drinking the conversion rate optimization Kool-Aid that misleads so many people.

Consider, for instance, this often-cited example of a boost in conversions due to a change in button color. The button change to red boosted conversions by 21 percent, but that doesn’t mean that red holds some sort of magic power to get people to take action.

We find additional evidence of the isolation effect in a myriad of multivariate tests, including this one conducted by Paras Chopra and published in Smashing Magazine . Chopra was testing to see how he could get more downloads for his PDFProducer program. The image with the most contrast outperformed the others by a large margin. While this is but one study of many, the isolation effect should be kept in mind when testing color palettes to create contrast in your web design and guide people to important action areas.

Why We Love “Mocha” but Hate “Brown”

Although different colors can be perceived in different ways, the names of those colors matters as well.

According to one study , when subjects were asked to evaluate products with different color names (such as makeup), “fancy” names were preferred far more often. For example, mocha was found to be significantly more likeable than brown —despite the fact that the researchers showed subjects the same color!

Additional research finds that the same effect applies to a wide variety of products; consumers rated elaborately named paint colors as more pleasing to the eye than their simply named counterparts.

It has also been shown that more unusual and unique color names can increase the intent to purchase. For instance, jelly beans with names such as razzmatazz were more likely to be chosen than jelly beans names such as lemon yellow . This effect was also found in non-food items such as sweatshirts.

As strange as it may seem, choosing creative, descriptive and memorable names to describe certain colors (such as “sky blue” over “light blue”) can be an important part of making sure the color of the product achieves its biggest impact.

Gregory Ciotti writes at HelpScout.net , where he explores the intersection of consumer behavior and customer loyalty .

Gregory Ciotti writes about the intersection of creative work and human behavior.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

STEM Writing Contest Winner

Color and the Brain: Are We All Simply Puppets of the Color Palette?

We are honoring the top eight winners of our Student STEM Writing Contest by publishing their essays. This one is by Helen Roche.

By The Learning Network

This essay, by Helen Roche, 17, from Lakewood High School in Lakewood, Ohio , is one of the top eight winners of The Learning Network’s third annual STEM Writing Contest , for which we received 3,564 entries.

You can find the work of all of our student winners here .

Just as we consume food, we consume color at an even greater rate, constantly digesting the different tonalities that paint our world. But little do we know that the beige of the library walls we study in, the red of busy hallways and restaurants, and the blue of your own bedroom have been strategically chosen from millions of different swatches and tones and shades to control our bodily functions and alter our emotional behavior.

From the moment you entered the world, you were swaddled in a baby pink blanket. The same pink of the padded walls that consoled a kicking and screaming child detained at the San Bernardino County Probation Department in California to sleep within 10 minutes. The same pink that covers the buildings of urban cities to prevent vandalism. And the same pink on the walls of visiting football teams’ locker rooms to calm grown men into submission and defeat. This shade of “Baker-Miller” pink finds itself recurring in our lives, all resulting in the same effect — comfort.

It’s known that color sets a mood: red feels energetic; orange and yellow are lively and a bit overwhelming; green and blue bring calmness; violet feels creative; pink is comforting; and neutrals feel … neutral. But it’s not so known how and why. Stephen Westland, a professor and the chair of color science and technology at the University of Leeds, explains that these effects are based on “light but not vision.” When exposed to color, the retinal cells of the eye don’t just send signals to the visual cortex to recognize such color, but also to the hypothalamus, the part of the brain in charge of the body’s self-regulation — the part of the brain unable to recognize visual images at all . Simply seeing a color, or, more particularly, the light the color gives off, can affect a person’s mood, temperature, sleep, heart rate, ability to eat and breathing patterns.

This stands true in an experiment conducted by Harold Wohlfarth, published in a 1982 issue of the International Journal of Biosocial Research, in which he repainted an orange and white classroom in shades of blue and installed gray carpeting in place of the previous orange rug; all of the students’ blood pressure, respiration rates and pulses dropped, and they all became calmer, after the room makeover. That included two blind students: Although their eyes were unable to see the physical changes, their hypothalami picked up the changes in wavelengths, so they were ultimately able to reap the same benefits of those with sight.

It might seem silly, but simple changes in colors can save lives. All around the world, each day, the color blue saves lives, whether by bathing a premature baby in blue light to replace blood transfusions or by shining blue light on the platforms of Tokyo’s Yamanote rail lines to keep a survivor of depression here to live another day. Blue is just one color, so imagine what the whole rainbow could do with a little research.

Maybe now you’ll think a little harder about that shirt you wear tomorrow — not only what it will say about you, but what it will do to you.

Works Cited

Gruson, Lindsey. “ Color Has a Powerful Effect on Behavior, Researchers Assert .” The New York Times, 19 Oct. 1982.

“ The Psychology of Color .” The New York Times, 8 Jan. 2006.

“ The Psychology of Colors and Their Meanings. ” Color Psychology, 2021.

Westland, Stephen. “ Does Color Really Affect Our Mind and Body? A Professor of Color Science Explains .” The Conversation, 25 Sept. 2017.

How Colors Affect Human Behavior

- Archaeology

- B.A., Biology, Emory University

- A.S., Nursing, Chattahoochee Technical College

Color psychology is the study of how colors affect human behavior, mood, or physiological processes. Colors are thought to influence our buying choices, our feelings, and even our memories. Ideas related to color psychology are heavily implemented in the areas of marketing and design. Companies choose colors that they believe will motivate customers to buy their products and improve brand awareness. Colors have even been used in color therapy techniques to treat various diseases.

Color Perception

Color psychology is a relatively new area of study that faces several challenges. A major difficulty that arises when investigating this topic is determining how to actually measure the effects of color. Color perception is very subjective, as different people have different ideas about and responses to colors. Several factors influence color perception, which makes it difficult to determine if color alone impacts our emotions and actions.

Factors that influence color perception include age , gender , and culture . In some cultures, for example, white is associated with happiness and purity. In a situation where a woman is wearing a white wedding dress, is she happy because she is influenced by the color white or because she is getting married? To someone from a different culture, wearing white may signify sadness. This is because in those cultures, white is associated with grief and death. These and similar factors must be considered when investigating the influence of colors on human emotions and behavior.

Color Associations

While no direct cause and effect relationship between color and behavior has been found, some generalizations about colors and what they may symbolize have been determined. Colors including red, yellow, and orange are considered warm colors and are thought to stimulate excited emotions.

Cool colors are found on the blue end of the visible light spectrum and include blue, violet, and green. These colors are associated with calmness, coolness, and tranquility.

Color symbolism is often employed in the field of graphic design and publishing to evoke certain emotions. Whether influenced by age, gender, culture, or not, research studies indicate that colors do have some impact on physiology, behavior, and mood in some individuals.

Ideas, attitudes, and emotions associated with the color red include:

Red is the longest wavelength of light on the visible light spectrum. In western cultures, red is associated with power, control, and strength. It also signals danger and triggers alertness. Red on traffic lights signal drivers to be alert and to stop. Some animals, such as snakes , have red coloration to indicate that they are dangerous and deadly.

Red also signifies passion and invokes the fight or flight response. This instinct is triggered by the brain's amygdala when we are confronted with danger or a threatening situation. It is what causes us to either fight or flee. Red is thought to raise metabolism and blood pressure, which are needed to prepare for action during an alarming situation.

Associations with the color blue include:

Blue is associated with calmness and tranquility. It is a symbol of logic, communication, and intelligence. It is linked with low stress, low temperature, and low pulse rate. Blue is also associated with a lack of warmth, emotional distance, and indifference. In spite of the negative associations, blue is often chosen as the most popular color in research surveys worldwide.

In research studies, blue light has also been found to reset our circadian rhythms or sleep-wake cycles. It is the blue wavelengths of light from the sun that inhibit the pineal gland from releasing melatonin during the day. Melatonin signals the body that it is time to sleep. Blue light stimulates us to stay awake.

Yellow is vivid and lively. Associations with yellow include:

Yellow is a bright color and the most visible color to the eye. It is associated with happiness, friendliness, and signifies competence. Yellow is the color of optimism and creativity. It attracts our attention and signifies caution as yellow is often used along with black on traffic signs, taxis, and school buses. Interestingly, yellow is also associated with fear, cowardice, and sickness.

Green symbolizes ideas such as:

Green is located between yellow and blue on the visible light spectrum and represents balance. It is the color of springtime and is commonly associated with growth, life, fertility, and nature. Green represents safety and is linked to prosperity, wealth, good fortune, and finances. It is considered a relaxing, soothing color that is thought to have a calming effect and to relieve stress. Negative associations with green include greed, jealousy, apathy, and lethargy.

Associations with the color orange include:

Orange is found between red and yellow on the visible light spectrum. It is thought to symbolize qualities that are a combination of the high-energy color red and the emotionally upbeat color yellow. Orange is associated with warmth, enthusiasm, and encouragement.

Orange is thought to affect appetite by increasing hunger. It also is thought to increase mental activity and acumen. In research studies, exposure to orange light has been shown to improve cognition and alertness. Orange is the primary color of fall and is also associated with summer. Light shades of orange are considered welcoming, while dark shades are identified with dishonesty.

Purple represents ideas and attitudes related to:

Purple or violet is the shortest wavelength on the visible light spectrum. It is a combination of blue and red and represents nobility, power, and royalty. Purple communicates a sense of worth, quality, and value. It is also associated with spirituality, sacredness, and gracefulness. Light purple colors represent romance and delicateness, while dark purple symbolizes sorrow, fear, and apprehensiveness.

Pink is considered a fun color that also represents:

- Passiveness

- Lack of willpower

Pink is the color most associated with femininity. It is tied to ideas of happiness, love, playfulness, and warmth. Pink is also related to harmony and closeness. Light pink signifies sensitivity and kindness, while hot pink represents passion and flirtatiousness. Pink is thought to have a calming effect and many prisons have pink holding cells in an attempt to reduce violent behavior among inmates. Negative associations with the color pink include immaturity, physical weakness, and low self-confidence.

Associations with black include:

Black absorbs all wavelengths of the visible light spectrum. It does not reflect color and adding black to a color creates different shades of the color. Black is viewed as mysterious, and in many cultures, it is associated with fear, death, the unknown, and evil. It also represents power, authority, and sophistication. Black signifies seriousness, independence, and is commonly associated with sadness and negativity.

White is perceived as delicate and pure. Other associations with white include:

- Cleanliness

White is the opposite of black and reflects all wavelengths of the visible light spectrum. When added to black, white lightens its color. In eastern cultures, white is associated with grief and death. In western cultures, it represents purity, innocence, and sterility. White is also associated with safety, spirituality, and faith. Negative associations with white include isolation, emptiness, and a sense of inaccessibility.

How We See Color

We don't actually see colors with our eyes. We see colors with our brains . Our eyes are important for detecting and responding to light, but it is the brain 's visual center in the occipital lobes that processes visual information and assigns color. The colors we see are determined by the wavelength of light that is reflected.

Visible color wavelengths range from about 380 nanometers (nm) to about 750 nanometers. Different colors along the visible light spectrum have different wavelengths. For example, red has wavelengths ranging from 620-750 nm, yellow from 570-590 nm, and blue from 450-495 nm. Our eyes are equipped with special photoreceptors called rods and cones. Rods are more sensitive to light than cones and allow us to see in dim light. Rods are not able to detect color. Cones detect a range of color light wavelengths.

Our eyes have three types of cones: blue, green, and red. The red cones are most sensitive to red wavelengths, blue cones to blue wavelengths, and green cones to green wavelengths. When a color is reflected from an object, the light wavelength hits the eyes and cones send signals to the visual cortex of the brain for processing. Our brain associates the wavelength with a color. Although our eyes have three cone types, the different wavelengths of light detected by the cones overlap. The brain integrates these overlapping wavelength signals sent from cones enabling us to distinguish between millions of different colors.

- Azeemi, S. T. Y., & Raza, S. M. (2005). A Critical Analysis of Chromotherapy and Its Scientific Evolution. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2 (4), 481–488. http://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/neh137

- Chellappa, S. L., Ly, J., Meyer, C., Balteau, E., Degueldre, C., Luxen, A., Phillips, C., Cooper, H., & Vandewalle, G. (2014). Photic memory for executive brain responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111 (16), 6087-6091. doi:doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320005111

- Dzulkifli, M. A., & Mustafar, M. F. (2013). The Influence of Colour on Memory Performance: A Review. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences : MJMS, 20 (2), 3–9.

- Holzman, D. C. (2010). What's in a Color? The Unique Human Health Effects of Blue Light. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118 (1), A22–A27.

- How Color Psychology Affects Blog Design

- What Is the Visible Light Spectrum?

- Visible Light Definition and Wavelengths

- The Visible Spectrum: Wavelengths and Colors

- Why Is Snow White?

- Why Is the Sun Yellow?

- Why Is the Sky Blue?

- Impossible Colors and How to See Them

- Structure and Function of the Human Eye

- Doppler Effect in Light: Red & Blue Shift

- Why Ice is Blue

- Why Milk Is White

- How Flame Test Colors Are Produced

- Why Is the Ocean Blue?

- Colors of Ancient Egypt

MINI REVIEW article

Color and psychological functioning: a review of theoretical and empirical work.

- Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA

In the past decade there has been increased interest in research on color and psychological functioning. Important advances have been made in theoretical work and empirical work, but there are also important weaknesses in both areas that must be addressed for the literature to continue to develop apace. In this article, I provide brief theoretical and empirical reviews of research in this area, in each instance beginning with a historical background and recent advancements, and proceeding to an evaluation focused on weaknesses that provide guidelines for future research. I conclude by reiterating that the literature on color and psychological functioning is at a nascent stage of development, and by recommending patience and prudence regarding conclusions about theory, findings, and real-world application.

The past decade has seen enhanced interest in research in the area of color and psychological functioning. Progress has been made on both theoretical and empirical fronts, but there are also weaknesses on both of these fronts that must be attended to for this research area to continue to make progress. In the following, I briefly review both advances and weaknesses in the literature on color and psychological functioning.

Theoretical Work

Background and recent developments.