Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

How understanding nature made the atomic bomb inevitable.

A chain reaction of basic discoveries preceded the bombing of Hiroshima 75 years ago

By Tom Siegfried

Contributing Correspondent

August 6, 2020 at 6:00 am

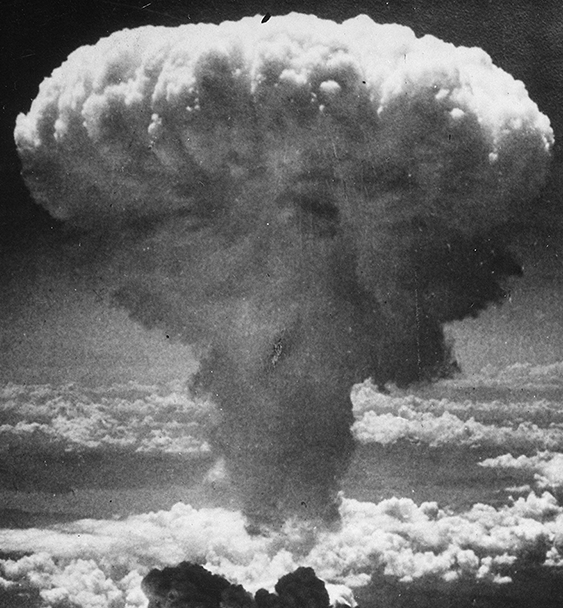

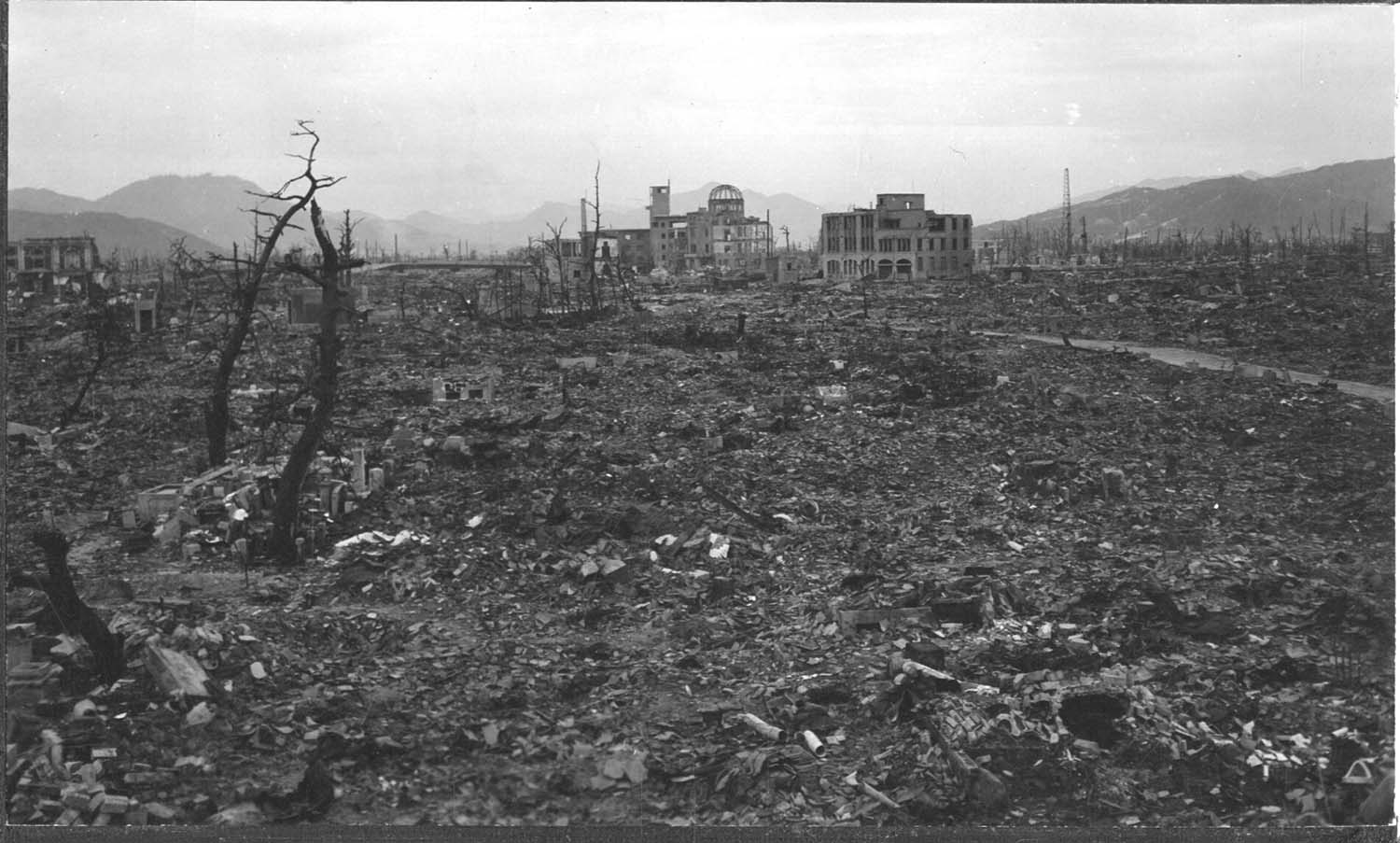

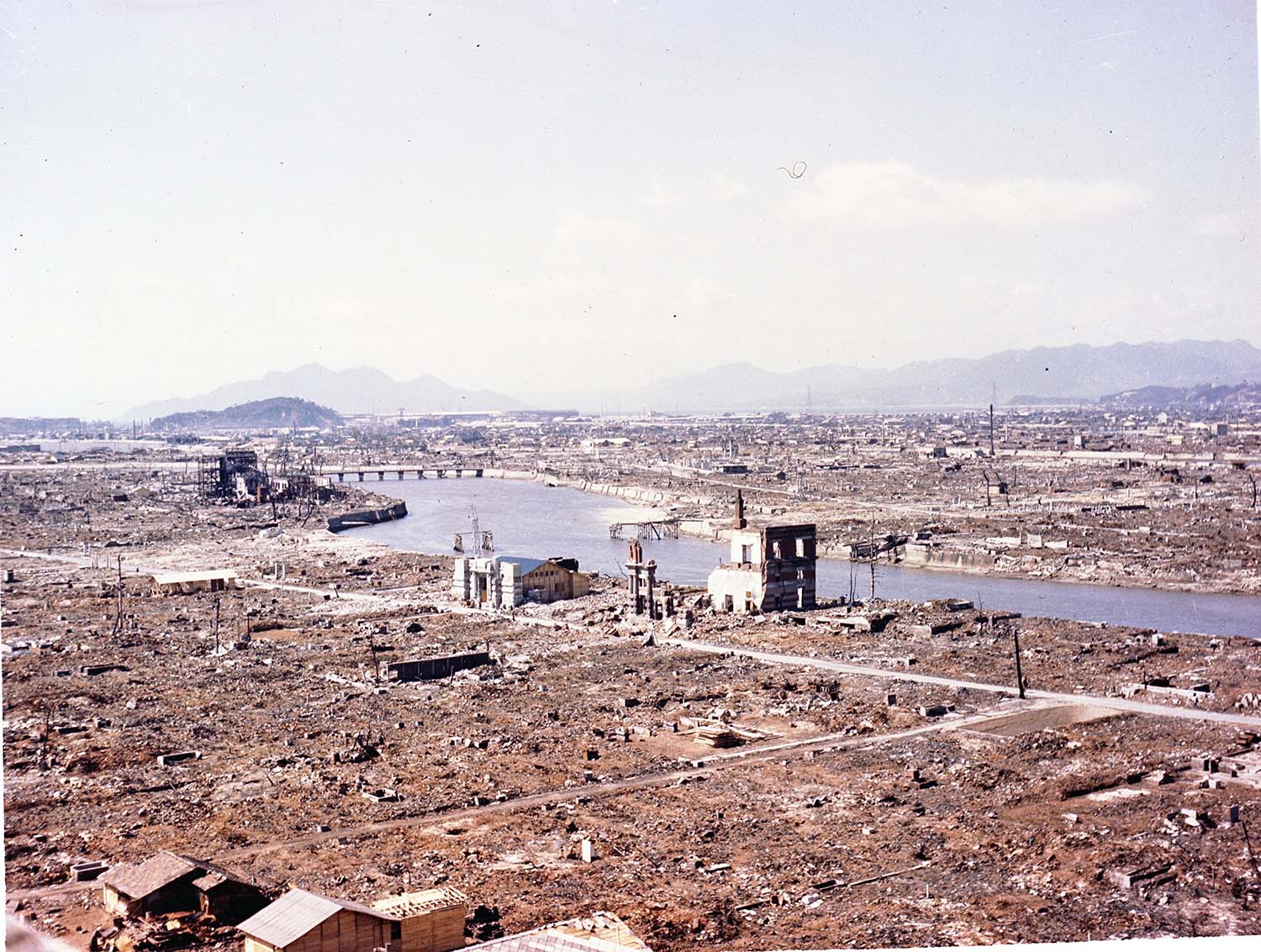

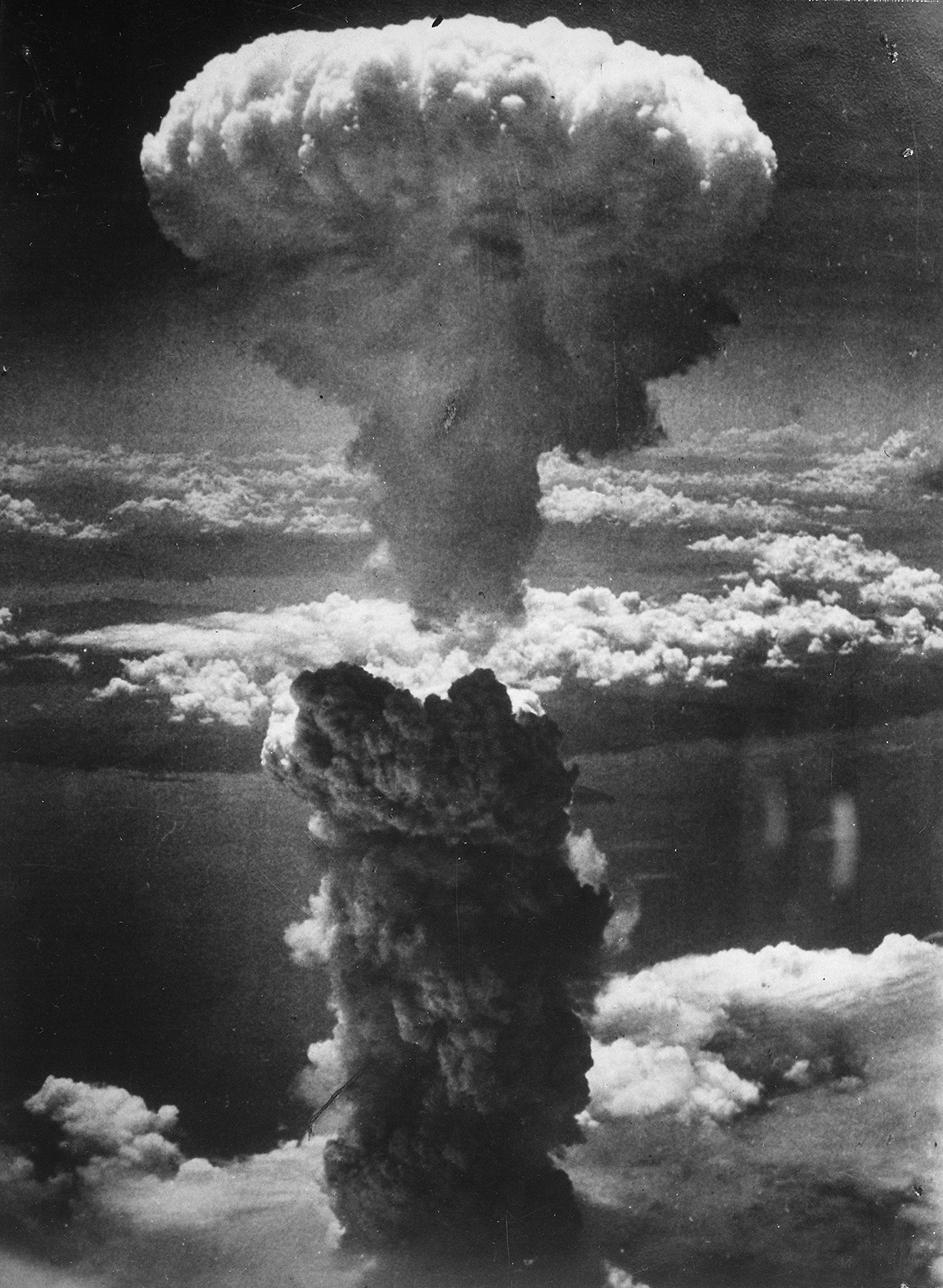

75 years ago, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan (shown). Three days later, another was dropped on Nagasaki.

509th Operations Group/Wikimedia Commons

Share this:

Atomic bombs hastened the end of World War II. But they launched another kind of war, a cold one, that threatened the entire planet with nuclear annihilation. So it’s understandable that on the 75th anniversary of the atomic bomb explosion that devastated Hiroshima (August 6, 1945), reflections tend to emphasize the geopolitical dramas during the decades that followed.

But it’s also worth reflecting on the scientific story of how the bombs came to be.

It’s not easy to pinpoint that story’s beginning. Nuclear fission — the source of the bomb’s energy — was discovered in 1938 , less than seven years before Hiroshima. But the science behind nuclear energy originated decades earlier. You could say 1905, when Einstein revealed to the world that E = mc 2 . Or perhaps it’s better to begin with Henri Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity in 1896. Radioactivity revealed a new sort of energy, of vast quantity, hidden within the most minuscule components of matter — the parts that made up atoms.

In any case, once science began to comprehend the subatomic world, no force could stop the eventual revelation of the atom’s power.

But the path from basic science to the bomb was not straightforward. There was no clear clue to how subatomic energy could be tapped for any significant use, military or otherwise. Writing in Science News Bulletin (the original Science News precursor) in 1921, physicist Robert Millikan noted that a gram of radium, in the process of disintegrating into lead, emits 300,000 times as much energy as burning a gram of coal. That wasn’t scary, Millikan said, because there wasn’t even enough radium in the world to make very much popcorn. But, he warned, “it is almost a foregone conclusion that similar stores of energy are also possessed by the atoms which … are not radioactive.”

Sign Up For the Latest from Science News

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your inbox

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

In 1923 editor Edwin Slosson of Science News-Letter (the immediate precursor to Science News ) also remarked that “all the elements have similar stores of energy if we only know how to release it.” But so far, he acknowledged, “scientists have not been able to unlock the atomic energy except by the employment of greater energy from another source.”

By then, physicists realized that the atom’s wealth of energy was stored in a nucleus — discovered by Ernest Rutherford in 1911 . But accessing nuclear energy for practical use seemed unfeasible — at least to Rutherford, who in 1933 said that anyone planning to exploit nuclear energy was “talking moonshine.” But just the year before, the tool for releasing nuclear power had been discovered by James Chadwick , in the form of the subatomic particle known as the neutron.

Having no electric charge, the neutron was the ideal bullet to shoot into an atom, able to penetrate the nucleus and destabilize it. Such experiments in Italy by Enrico Fermi in the 1930s did actually induce fission in uranium. But Fermi thought he had created new, heavier chemical elements. He had no idea that the uranium nucleus had split. He concluded that he had produced a new element , number 93, heavier than uranium (element 92).

Not everyone agreed. Ida Noddack, a German chemist-physicist , argued that the evidence was inconclusive, and Fermi might have produced lighter elements, fragments of the uranium nucleus. But she was defying the prevailing wisdom. As the German chemist Otto Hahn wrote years later, the idea of breaking a uranium nucleus into smaller pieces was “wholly incompatible with the laws of atomic physics. To split heavy atomic nuclei into lighter ones was then considered impossible.”

Nevertheless Hahn and Lise Meitner, an Austrian physicist , continued bombarding uranium with neutrons, producing what they too believed to be new elements. Soon Meitner had to flee Germany for Sweden to avoid Nazi persecution of Jews. Hahn continued the work with chemist Fritz Strassmann; in December 1938 they found that an element they thought was radium could not be chemically distinguished from barium — apparently because it was barium. Hahn and Strassmann couldn’t explain how that could be.

Hahn wrote of this result to Meitner, who discussed it with her nephew Otto Frisch, a physicist studying at Niels Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen. Meitner and Frisch figured out what happened — the neutron had induced the uranium nucleus to split. Barium was one of the leftover chunks. Frisch told Bohr, about to board a ship to America, who realized instantly that fission confirmed his belief that an atomic nucleus behaved analogously to a drop of liquid. Upon arrival in the United States, Bohr began collaborating with John Archibald Wheeler at Princeton to explain the fission process. They quickly found that fission occurred much more readily in uranium-235, the rare form, than in the more common uranium-238. And their analysis revealed that an as yet undiscovered element, number 94, would also be especially efficient at fissioning. Their paper appeared on September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland to begin World War II.

Between Bohr’s arrival in America in January 1939 and the publication of his paper with Wheeler, news of fission’s reality spread, stunning physicists and chemists around the world. At the end of January, for instance, word of fission reached Berkeley, where the leading physicist was J. Robert Oppenheimer, who eventually became the scientist that led the Manhattan Project to build the bomb.

Among the attendees at the Berkeley seminar introducing fission was Glenn Seaborg, a young chemistry instructor (who in 1941 discovered the unknown element 94 predicted by Bohr and Wheeler, naming it plutonium). Seaborg recalled that at first Oppenheimer didn’t believe fission happened. But, “after a few minutes he decided it was possible,” Seaborg said in a 1997 interview. “It just caught everybody by surprise.”

After the initial surprise, physicists quickly established that fission was the key to unlocking the atom’s energy storehouse. “Lots of people verified that indeed when uranium is bombarded by neutrons, slow neutrons in particular, a process occurs which releases tremendous amounts of energy,” physicist Hans Bethe said in a 1997 interview. Soon the implications for warfare occupied everybody’s attention.

“The threat of war was getting closer and closer,” Wheeler said in an interview in 1985. “It was impossible not to think about what this business (fission) could mean in the event of war.” In early 1939, physicists meeting to discuss fission concurred that a fission bomb was thinkable. “Everybody agreed that it was perfectly possible to make a nuclear explosive,” Bethe remembered.

Concerns that Germany might develop a nuclear bomb prompted Albert Einstein’s famous letter to President Franklin Roosevelt , sent in August 1939, that eventually led to the Manhattan Project. It became clear that building a fission bomb would require generating a “chain reaction” — the fission process itself would need to release neutrons capable of inducing further fission. In December 1942, Fermi led the team at the University of Chicago that demonstrated a sustained chain reaction , after which work on the bomb proceeded in Los Alamos, N.M., under Oppenheimer’s direction.

At first some physicists thought a bomb could not be developed rapidly enough to be relevant to the war. Bethe, for instance, preferred to work on radar.

“I had considered the whole enterprise a boondoggle,” he said. “I thought this had nothing to do with the war.” But by April 1943 Oppenheimer succeeded in recruiting Bethe to Los Alamos. By that time the science was in place, and the path to designing and building a bomb was straightforward. “All we had to do was to find out that there were no unforeseen difficulties,” Bethe said.

Ultimately the prototype was exploded at Alamogordo in July 1945, about three weeks before the bomb’s use against Japan.

It was a weapon more horrifying than anything humankind had ever encountered or imagined. And science was responsible. But only because science succeeded in understanding nature more deeply than before. Nobody knew at first where that understanding would lead.

There was absolutely no way to foresee that the discovery of radioactivity, or the atomic nucleus, or even the neutron would eventually enable the construction of a weapon of mass destruction. Yet once it was known that a bomb was possible, it was inevitable.

After Germany’s surrender in World War II, the Allies detained several top German scientists, including Werner Heisenberg, leader of the Nazi bomb project, and eavesdropped on their conversations. It was clear that the Germans failed to build a bomb because they did not think it was practically possible. But after hearing of the bombing of Hiroshima, Heisenberg was quickly able to figure out how the bomb had, in fact, been feasible. Once scientists know for sure something is possible, it’s a lot easier to do it.

In the case of the atomic bomb, basic research seeking nature’s secrets initiated a chain reaction of new knowledge, impossible to control. So the mushroom cloud that resulted symbolizes one of science’s most disturbing successes.

More Stories from Science News on Physics

Physicists take a major step toward making a nuclear clock

During a total solar eclipse, some colors really pop. Here’s why

A teeny device can measure subtle shifts in Earth’s gravitational field

Timbre can affect what harmony is music to our ears

50 years ago, superconductors were warming up

Forests might serve as enormous neutrino detectors

‘Countdown’ takes stock of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile

Physicist Sekazi Mtingwa considers himself an apostle of science

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Columbia University Libraries

Columbia university archives: manhattan project.

- Alumni Search

- Faculty Search

- Online Bulletins

- Master's Essays & Dissertations

- Individuals

- Student Life

- Buildings & Grounds

- Scanned Images

- 1968 Crisis

- 49th Street Campus

- Coeducation at Columbia

- Columbia and the Civil War

- Core Curriculum

- King's College

- LGBT Student Groups

Manhattan Project

- Seth Low Junior College

- Varsity Show

- University Presidents

- Schools & Departments

- Black Experience at Columbia

- Asian & Asian American Experience

University Archives

Phone: (212) 854-3786 Fax: (212) 854-1365 E-mail: [email protected]

Map | Hours | Directions

Related Collections

Barnard College The Barnard Archives and Special Collections serves as the final repository for the historical records of Barnard College, from its founding in 1889 to the present day. For more information, please contact [email protected] .

Health Sciences Library The Archives and Special Collections at the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library of Columbia University can help you find information about the schools of the Medical Center: College of Physicians & Surgeons, School of Nursing, College of Dental Medicine (formerly the School of Dental & Oral Surgery), Mailman School of Public Health, and the College of Pharmaceutical Sciences. For more information, please contact [email protected] .

How to find information about the Manhattan Project

The Department of Energy releases declassified Manhattan Project-related reports and documents on its OpenNet website. This searchable database includes bibliographical references to all documents declassified and made publicly available after October 1, 1994. Some documents can be viewed as full text. This website also provides a comprehensive Manhattan District History.

To start your research into Columbia's role in the Manhattan Project, read Laurence Lippsett's article "The race to make the bomb. The Manhattan Project: Columbia's wartime secret." The article appeared in Columbia College Today , Spring/Summer 1995, 18-21, 45.

- The Manhattan Project: Columbia's wartime secret Lippsett, Laurence. "The race to make the bomb. The Manhattan Project: Columbia's wartime secret." Columbia College Today, Spring/Summer 1995, pp. 18-21, 45.

- Archival Collections

- Additional Sources

The following are the most often consulted resources available at the University Archives. Archival collections are non-circulating and can only be viewed in the Rare Book & Manuscript Library's reading room (RBML). In order to use the University Archives collections at the RBML, y ou will be required to register your own Special Collections Research Account before your visit and to validate the account in person with government-issued photo identification or Columbia ID card. Once you have created your Special Collections Research Account , you will be able to request materials directly from the finding aid: click the check box located on the right for the box(es) you need, and then scroll back to the top of the container list document and click “Submit Request” button in the red-rimmed box at top. This should lead you directly to your Special Collections Research Account to complete the request form.

- Annual Reports The Annual Reports of the President and Treasurer to the Trustees offer a yearly "state of the University" from 1891 to 1946. You can find statements about Columbia's role in the 1945 Annual Report presented to the Trustees (starting on page 14).

- Central Files, 1890-1984 Central Files contain the core administrative records of the University. The records that comprise Central Files originated in the Office of the President starting in 1890 and continue through the present. Central Files chiefly contains correspondence (sent and received) between Columbia University administrators and other University officers, faculty, trustees, and individuals and organizations from outside the University. Box 301, folder 1 contains the August 6 and 14, 1945 telegrams from War Department to President Butler about continuing the secrecy of atomic bomb research. In addition to the War Department, Central Files includes correspondence with Fermi, Dunning, US Atomic Energy Commission, etc.

- George Braxton Pegram papers, 1903-1958 Nuclear physicist, professor of physics, and Dean of Graduate Faculties at Columbia University, Pegram conducted a great deal of defense-related research and was responsible for the famous meeting between Franklin Delano Roosevelt and American nuclear scientists prior to World War II that eventually led to the establishment of the Manhattan Project. The National Defense Research Committee contracts for work on uranium and the Physics Department, correspondence, 1940-1947 (declassified in 1960), can be found in the "Atomic Energy Commission" folder in Box 41. There is also a folder titled "Atomic Bomb Discussion" in this box. Box 41 is stored offsite and must be requested at least 48 business hours in advance of use in our reading room.

- Historical Photograph Collection - Series V: Atomic Energy A small series of images related to atomic research conducted by Columbia. Included are images of the Nevis and Pupin Laboratories and a 1948 exhibit about atomic energy; including the Seventh Biennial Award Dinner for The Atomic Bomb Project, sponsored by Chemical & Metallurgical Engineering; Waldorf-Astoria, 1946.

- "Atomic Energy Research, 1930s-1980s" in Box 6 folder 5

- "Manhattan Project, 1940s-2000s" in Box 41, folder 10

- "SAM Labs--Manhattan Project, 1940s-1990s" in Box 48, folder 3

For more information on how to access our collections, check out our Research & Access website. If you have any questions about how to find materials or how to access materials, please contact [email protected] .

Archival collections are non-circulating and can only be viewed in the Rare Book & Manuscript Library's reading room (RBML). In order to use the University Archives collections at the RBML, y ou will be required to register your own Special Collections Research Account before your visit and to validate the account in person with government-issued photo identification or Columbia ID card. Once you have created your Special Collections Research Account , you will be able to request materials directly from the finding aid: click the check box located on the right for the box(es) you need, and then scroll back to the top of the container list document and click “Submit Request” button in the red-rimmed box at top. This should lead you directly to your Special Collections Research Account to complete the request form.

- C. S. (Chien-shiung) Wu Papers The collection consists of speeches, reports, publications, research notes, and correspondence. The bulk of the collection relates to Wu's involvement in the American Physical Society as well as her research activities. The correspondence is chiefly professional, relating to C. S. Wu's physics research, professional commitments, appointments, meetings, conferences, and publications. Correspondence also includes letters from individuals around the world praising Wu for her accomplishments, asking advice, arranging speaking engagements, discussing administrative matters, and trading research notes, as well as information on publications and other topics. In addition, the collection contains information on Wu's involvement in the development of an affirmative action program at Columbia University in the 1970s.

- Selig Hecht papers, 1914-1937 Professor of biophysics at Columbia University, 1926-1947, and author of Explaining the Atom (1947).

- Dana Paul Mitchel Papers, [ca. 1925]-1960 Professional and personal correspondence, administrative records, manuscript lecture notes, and some miscellaneous printed materials. The general correspondence file, 1927-1958, contains letters, both personal and professional, with colleagues, with and about his students, about laboratory equipment, about weapons for the Army and Navy, and with industry concerning his research.

- Department of Physics Historical records, 1862-1997 This collection is made up of an assortment of historical material, consisting of photographs, negatives, faculty and guest lecturer correspondence, biographical materials for some of the faculty, programs from various lecture series given at Columbia, publications, picture postcards, and even a sheet of commemorative postage stamps. These documents were collected in The Columbia Physics Department: a brief history , a booklet of reproductions of some of the archival documents, correspondence, and photographs relating to the history of the Physics department of Columbia. It includes listing and photos of Columbia's Nobel Laureates and discussion of Columbia's involvement in the Manhattan Project. Correspondents include Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, H. A. Lorentz, R. A. Millikan, and Max Planck.

- Department of Physics records, 1870-1983 This collection contains records of the Physics Department of Columbia University and several of its affiliated research laboratories: the Columbia Radiation Laboratory, the Pupin Cyclotron Laboratory, the Nevis Cyclotron Laboratory, and the Pegram Nuclear Physics Laboratory.

- Columbia Alumni News Alumni News served as a Columbia news magazine in its earlier days, publishing biweekly issues during the academic year. The first September 1945 issue has as its main article " Columbia and the Atomic Bomb " as Columbia's role was no longer secret.

Columbia News online article: Shea, Christopher D. " Seen 'Oppenheimer'? Learn About Columbia's Role in Building the First Atom Bomb, 24 July 2023.

- Oral Histories The Columbia Center for Oral History Archives is one of the largest oral history collections in the United States. The Manhattan Project is discussed in a number of interviews under a number of projects. To search for these interviews, begin by exploring the Oral History Portal . When you have found an oral history interview that interests you, please click the link to view the Full CLIO record .The CLIO record will include information about restrictions and whether or not this interview is open to researchers. You can request the transcripts to be read at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library's reading room by using your Special Collections Research Account . For more information, please visit the Oral History Archives website .

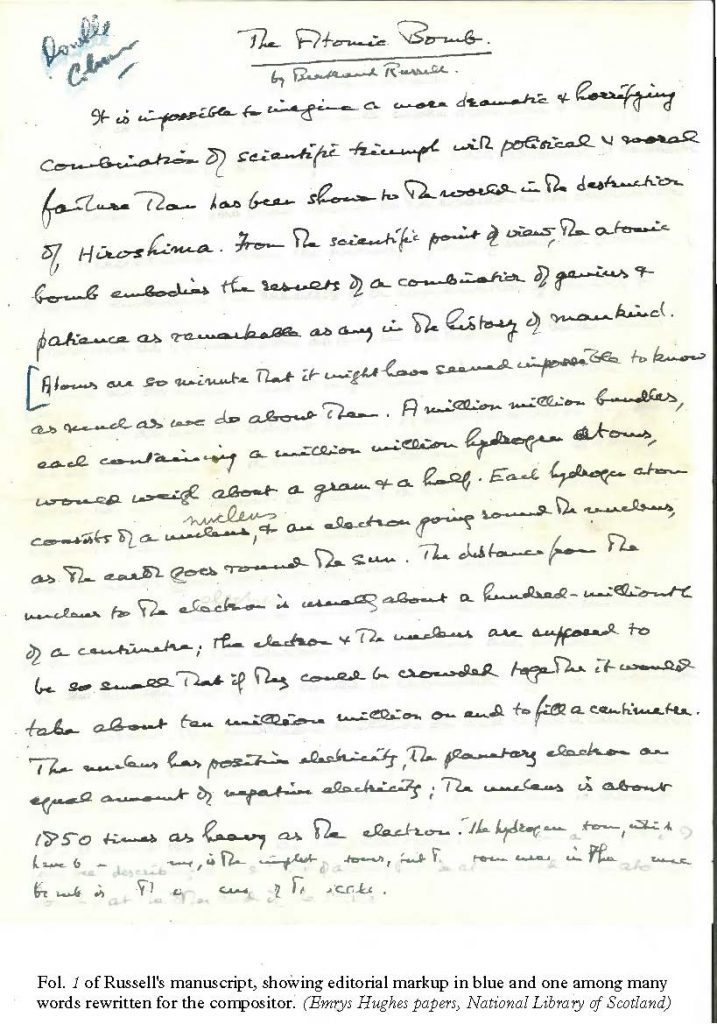

About the images

Top - Two graduate students assembling graphite blocks for the nuclear reactor. (Scan #3114) Historical Photograph Collection , , University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries.

Right - "Two leaders in atom work at Columbia -- Dr. John R. Dunning (right), one of the country's pioneer atomic scientists, points out to Dr. Pegram the workings of his "atomic pinball machine," which he uses to explain atomic energy to the public." (Scan #0638) Historical Photograph Collection , University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries.

- << Previous: LGBT Student Groups

- Next: Seth Low Junior College >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 8:51 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.columbia.edu/uarchives

- Donate Books or Items

- Suggestions & Feedback

- Report an E-Resource Problem

- The Bancroft Prizes

- Student Library Advisory Committee

- Jobs & Internships

- Behind the Scenes at Columbia's Libraries

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOK REVIEW

- 19 April 2021

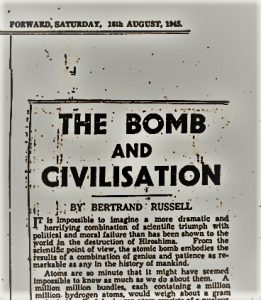

Born secret — the heavy burden of bomb physics

- Sharon Weinberger 0

Sharon Weinberger is the author of The Imagineers of War: The Untold Story of DARPA, the Pentagon Agency That Changed the World .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States Alex Wellerstein Univ. Chicago Press (2021)

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 592 , 505-506 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-01024-9

Related Articles

- Nuclear physics

After the genocide: what scientists are learning from Rwanda

News Feature 05 APR 24

Long-lost photos reveal details of world’s first police crime lab

News 05 APR 24

Why hand-operated front brakes were set to be the future of motoring

News & Views 02 APR 24

The science of Oppenheimer: meet the Oscar-winning movie’s specialist advisers

News Q&A 11 MAR 24

Space and nuclear pioneers show the value of empowering women in STEM

Correspondence 05 MAR 24

Building used by Marie Curie will be dismantled to erect cancer centre

News 02 FEB 24

The EU’s ominous emphasis on ‘open strategic autonomy’ in research

Editorial 03 APR 24

Cuts to postgraduate funding threaten Brazilian science — again

Correspondence 26 MAR 24

Don’t underestimate the rising threat of groundwater to coastal cities

High-Level Talents at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

For clinical medicine and basic medicine; basic research of emerging inter-disciplines and medical big data.

Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University

POSTDOCTORAL Fellow -- DEPARTMENT OF Surgery – BIDMC, Harvard Medical School

The Division of Urologic Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School invites applicatio...

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Director of Research

Applications are invited for the post of Director of Research at Cancer Institute (WIA), Chennai, India.

Chennai, Tamil Nadu (IN)

Cancer Institute (W.I.A)

Postdoctoral Fellow in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Join Atomic Lab in Boston as a postdoc in human immunology for universal flu vaccine project. Expertise in cytometry, cell sorting, scRNAseq.

Boston University Atomic Lab

Research Associate - Neuroscience and Respiratory Physiology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

National Archives News

The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, August 1945

Photograph of Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. (National Archives Identifier 22345671 )

The United States bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9, 1945, were the first instances of atomic bombs used against humans, killing tens of thousands of people, obliterating the cities, and contributing to the end of World War II. The National Archives maintains the documents that trace the evolution of the project to develop the bombs, their use in 1945, and the aftermath.

Online Exhibits

The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki features a letter written by Luis Alvarez, a physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, on August 6, 1945, after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan.

[Photograph: The atomic cloud rising over Nagasaki, Japan, August 9, 1945. National Archives Identifier 535795 ]

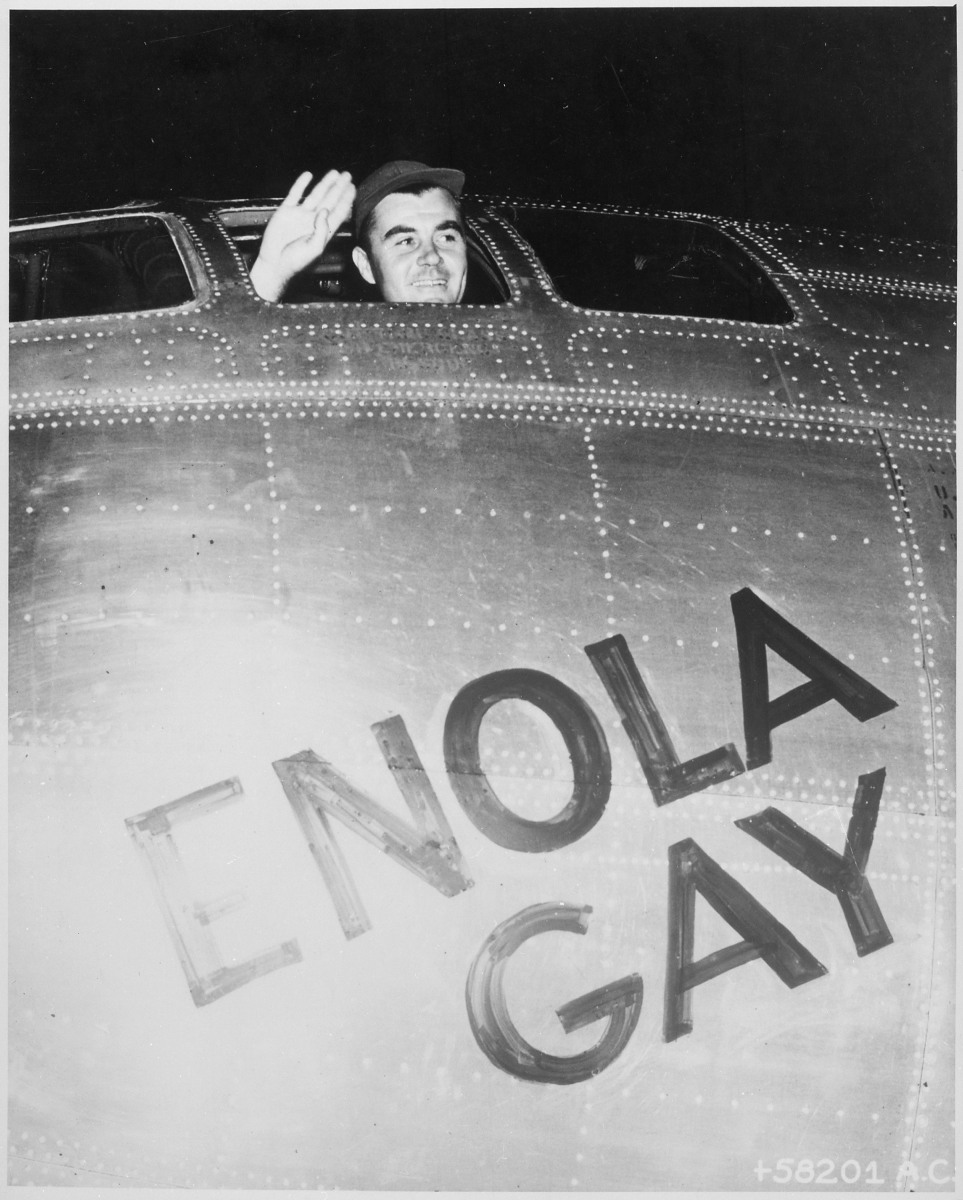

A People at War looks at the 509 Composite Group, the unit selected to carry the atomic bomb to Hiroshima.

[Photograph: Col. Paul Tibbets, Jr., waves from the cockpit of the Enola Gay before departing for Hiroshima, August 6, 1945. National Archives Identifier 535737 ]

Photograph Gallery

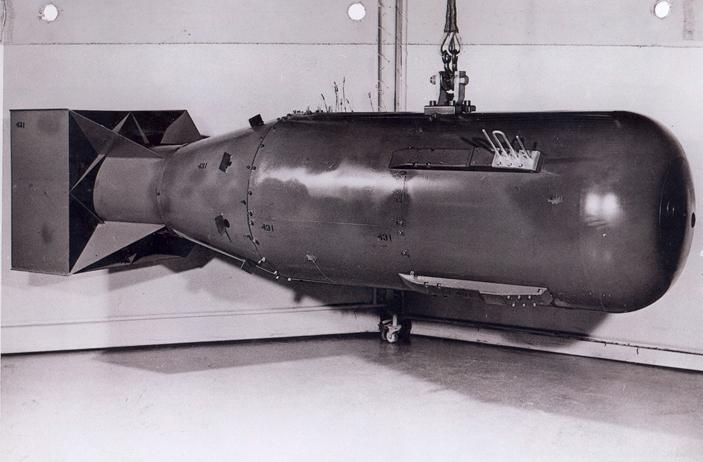

"Little Boy" atomic bomb being raised into plane on Tinian Island before the flight to Hiroshima. National Archives Identifier 76048583

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 22345671

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 22345679

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 22345680

Hiroshima after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 148728174

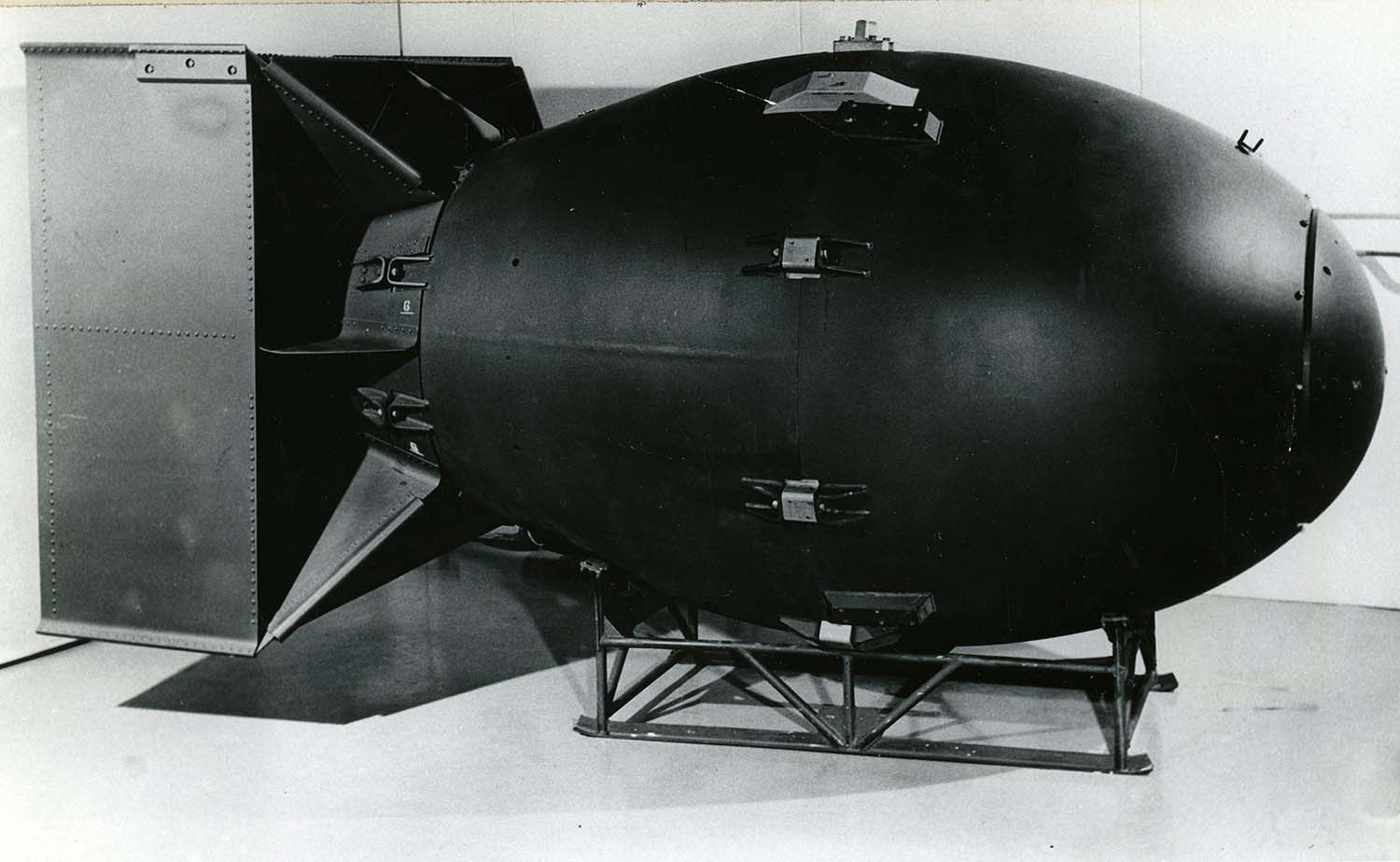

Nuclear weapon of the "Fat Man" type, the kind detonated over Nagasaki, Japan. National Archives Identifier 175539928

The atomic cloud rising over Nagasaki, Japan. National Archives Identifier 535795

Nagasaki after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 39147824

Nagasaki after the atomic bomb. National Archives Identifier 39147850

Additional Photographs

Atomic Bomb Preparations at Tinian Island, 1945

Photographs used in the report Effects of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, Japan

Manhattan Project Notebook

Atomic bomb/Enola Gay preparations for the bombing missions

Post-bombing aerial and on-the-ground images of Hiroshima

Empty bottle of Chianti Bertolli wine signed by scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project

Archival Film

Hiroshima and Nagasaki Effects, 1945

The Last Bomb , a 1945 film, done in Technicolor, by the Army Air Forces Combat Camera Units and Motion Picture Units covering the B-29 bombing raids on Japan

Effects on the human body of radiation from the atomic bomb

Additional Records

Photos: Atomic Bomb Preparations at Tinian Island, 1945

Atomic bomb/ Enola Gay preparations for the bombing missions

Post-Hiroshima bombing aerial and on-the-ground images

Color image of Hiroshima after bombing

Manhattan Project records from Oak Ridge, TN

Blogs and Social Media Posts

Unwritten Record: Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Unwritten Record: Witness to Destruction: Photographs and Sound Recordings Documenting the Hiroshima Bombing

Forward with Roosevelt: Found in the Archives: The Einstein Letter

Pieces of History: Little Boy: The First Atomic Bomb

Pieces of History: Harry Truman and the Bomb

Pieces of History: Morgantown Ordnance Works (part of the Manhattan Project) Panoramas, 1940–1942

Today's Document: Petition from Manhattan Project Scientists to President Truman

For Educators

Docs Teach resources on the atomic bomb

Teaching with Documents: Photographs and Pamphlet about Nuclear Fallout

Kennedy Library: “The Presidency in the Nuclear Age”

At the Presidential Libraries

Roosevelt Library: Albert Einstein’s letter to FDR regarding the atomic bomb

Truman Library: “The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb ”

Truman Library: Additional records on the bombing of Hiroshima

Truman Library: President Truman's Diary Entry for July 17, 1945 (the day before Truman learned that the United States had successfully tested the world's first atomic bomb)

Truman Library: Memo for the Record, Manhattan Project, July 20, 1945

Truman Library: Petition from Leo Szilard and other scientists to President Truman

Eisenhower Library: Atoms for Peace

Kennedy Library: “ The Presidency in the Nuclear Age: The Race to Build the Bomb and the Decision to Use It”

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II

A Collection of Primary Sources

Updated National Security Archive Posting Marks 75th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombings of Japan and the End of World War II

Extensive Compilation of Primary Source Documents Explores Manhattan Project, Eisenhower’s Early Misgivings about First Nuclear Use, Curtis LeMay and the Firebombing of Tokyo, Debates over Japanese Surrender Terms, Atomic Targeting Decisions, and Lagging Awareness of Radiation Effects

Washington, D.C., August 4, 2020 – To mark the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the National Security Archive is updating and reposting one of its most popular e-books of the past 25 years.

While U.S. leaders hailed the bombings at the time and for many years afterwards for bringing the Pacific war to an end and saving untold thousands of American lives, that interpretation has since been seriously challenged. Moreover, ethical questions have shrouded the bombings which caused terrible human losses and in succeeding decades fed a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union and now Russia and others.

Three-quarters of a century on, Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain emblematic of the dangers and human costs of warfare, specifically the use of nuclear weapons. Since these issues will be subjects of hot debate for many more years, the Archive has once again refreshed its compilation of declassified U.S. government documents and translated Japanese records that first appeared on these pages in 2005.

* * * * *

Introduction

By William Burr

The 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 is an occasion for sober reflection. In Japan and elsewhere around the world, each anniversary is observed with great solemnity. The bombings were the first time that nuclear weapons had been detonated in combat operations. They caused terrible human losses and destruction at the time and more deaths and sickness in the years ahead from the radiation effects. And the U.S. bombings hastened the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb project and have fed a big-power nuclear arms race to this day. Thankfully, nuclear weapons have not been exploded in war since 1945, perhaps owing to the taboo against their use shaped by the dropping of the bombs on Japan.

Along with the ethical issues involved in the use of atomic and other mass casualty weapons, why the bombs were dropped in the first place has been the subject of sometimes heated debate. As with all events in human history, interpretations vary and readings of primary sources can lead to different conclusions. Thus, the extent to which the bombings contributed to the end of World War II or the beginning of the Cold War remain live issues. A significant contested question is whether, under the weight of a U.S. blockade and massive conventional bombing, the Japanese were ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped. Also still debated is the impact of the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria, compared to the atomic bombings, on the Japanese decision to surrender. Counterfactual issues are also disputed, for example whether there were alternatives to the atomic bombings, or would the Japanese have surrendered had a demonstration of the bomb been used to produced shock and awe. Moreover, the role of an invasion of Japan in U.S. planning remains a matter of debate, with some arguing that the bombings spared many thousands of American lives that otherwise would have been lost in an invasion.

Those and other questions will be subjects of discussion well into the indefinite future. Interested readers will continue to absorb the fascinating historical literature on the subject. Some will want to read declassified primary sources so they can further develop their own thinking about the issues. Toward that end, in 2005, at the time of the 60th anniversary of the bombings, staff at the National Security Archive compiled and scanned a significant number of declassified U.S. government documents to make them more widely available. The documents cover multiple aspects of the bombings and their context. Also included, to give a wider perspective, were translations of Japanese documents not widely available before. Since 2005, the collection has been updated. This latest iteration of the collection includes corrections, a few minor revisions, and updated footnotes to take into account recently published secondary literature.

2015 Update

August 4, 2015 – A few months after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, General Dwight D. Eisenhower commented during a social occasion “how he had hoped that the war might have ended without our having to use the atomic bomb.” This virtually unknown evidence from the diary of Robert P. Meiklejohn, an assistant to Ambassador W. Averell Harriman, published for the first time today by the National Security Archive, confirms that the future President Eisenhower had early misgivings about the first use of atomic weapons by the United States. General George C. Marshall is the only high-level official whose contemporaneous (pre-Hiroshima) doubts about using the weapons against cities are on record.

On the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the National Security Archive updates its 2005 publication of the most comprehensive on-line collection of declassified U.S. government documents on the first use of the atomic bomb and the end of the war in the Pacific. This update presents previously unpublished material and translations of difficult-to-find records. Included are documents on the early stages of the U.S. atomic bomb project, Army Air Force General Curtis LeMay’s report on the firebombing of Tokyo (March 1945), Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s requests for modification of unconditional surrender terms, Soviet documents relating to the events, excerpts from the Robert P. Meiklejohn diaries mentioned above, and selections from the diaries of Walter J. Brown, special assistant to Secretary of State James Byrnes.

The original 2005 posting included a wide range of material, including formerly top secret "Magic" summaries of intercepted Japanese communications and the first-ever full translations from the Japanese of accounts of high level meetings and discussions in Tokyo leading to the Emperor’s decision to surrender. Also documented are U.S. decisions to target Japanese cities, pre-Hiroshima petitions by scientists questioning the military use of the A-bomb, proposals for demonstrating the effects of the bomb, debates over whether to modify unconditional surrender terms, reports from the bombing missions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and belated top-level awareness of the radiation effects of atomic weapons.

The documents can help readers to make up their own minds about long-standing controversies such as whether the first use of atomic weapons was justified, whether President Harry S. Truman had alternatives to atomic attacks for ending the war, and what the impact of the Soviet declaration of war on Japan was. Since the 1960s, when the declassification of important sources began, historians have engaged in vigorous debate over the bomb and the end of World War II. Drawing on sources at the National Archives and the Library of Congress as well as Japanese materials, this electronic briefing book includes key documents that historians of the events have relied upon to present their findings and advance their interpretations.

The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II: A Collection of Primary Sources

Seventy years ago this month, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, and the Japanese government surrendered to the United States and its allies. The nuclear age had truly begun with the first military use of atomic weapons. With the material that follows, the National Security Archive publishes the most comprehensive on-line collection to date of declassified U.S. government documents on the atomic bomb and the end of the war in the Pacific. Besides material from the files of the Manhattan Project, this collection includes formerly “Top Secret Ultra” summaries and translations of Japanese diplomatic cable traffic intercepted under the “Magic” program. Moreover, the collection includes for the first time translations from Japanese sources of high level meetings and discussions in Tokyo, including the conferences when Emperor Hirohito authorized the final decision to surrender. [1]

Ever since the atomic bombs were exploded over Japanese cities, historians, social scientists, journalists, World War II veterans, and ordinary citizens have engaged in intense controversy about the events of August 1945. John Hersey’s Hiroshima , first published in the New Yorker in 1946 encouraged unsettled readers to question the bombings while church groups and some commentators, most prominently Norman Cousins, explicitly criticized them. Former Secretary of War Henry Stimson found the criticisms troubling and published an influential justification for the attacks in Harper’s . [2] During the 1960s the availability of primary sources made historical research and writing possible and the debate became more vigorous. Historians Herbert Feis and Gar Alperovitz raised searching questions about the first use of nuclear weapons and their broader political and diplomatic implications. The controversy, especially the arguments made by Alperovitz and others about “atomic diplomacy” quickly became caught up in heated debates over Cold War “revisionism.” The controversy simmered over the years with major contributions by Martin Sherwin and Barton J. Bernstein but it became explosive during the mid-1990s when curators at the National Air and Space Museum met the wrath of the Air Force Association over a proposed historical exhibit on the Enola Gay. [3] The NASM exhibit was drastically scaled-down but historians and journalist continued to engage in the debate. Alperovitz, Bernstein, and Sherwin made new contributions as did other historians, social scientists, and journalists including Richard B. Frank, Herbert Bix, Sadao Asada, Kai Bird, Robert James Maddox, Sean Malloy, Robert P. Newman, Robert S. Norris, Tsuyoshi Hagesawa, and J. Samuel Walker. [4]

The continued controversy has revolved around the following, among other, questions:

- were the atomic strikes necessary primarily to avert an invasion of Japan in November 1945?

- Did Truman authorize the use of atomic bombs for diplomatic-political reasons-- to intimidate the Soviets--or was his major goal to force Japan to surrender and bring the war to an early end?

- If ending the war quickly was the most important motivation of Truman and his advisers to what extent did they see an “atomic diplomacy” capability as a “bonus”?

- To what extent did subsequent justification for the atomic bomb exaggerate or misuse wartime estimates for U.S. casualties stemming from an invasion of Japan?

- Were there alternatives to the use of the weapons? If there were, what were they and how plausible are they in retrospect? Why were alternatives not pursued?

- How did the U.S. government plan to use the bombs? What concepts did war planners use to select targets? To what extent were senior officials interested in looking at alternatives to urban targets? How familiar was President Truman with the concepts that led target planners chose major cities as targets?

- What did senior officials know about the effects of atomic bombs before they were first used. How much did top officials know about the radiation effects of the weapons?

- Did President Truman make a decision, in a robust sense, to use the bomb or did he inherit a decision that had already been made?

- Were the Japanese ready to surrender before the bombs were dropped? To what extent had Emperor Hirohito prolonged the war unnecessarily by not seizing opportunities for surrender?

- If the United States had been more flexible about the demand for “unconditional surrender” by explicitly or implicitly guaranteeing a constitutional monarchy would Japan have surrendered earlier than it did?

- How decisive was the atomic bombings to the Japanese decision to surrender?

- Was the bombing of Nagasaki unnecessary? To the extent that the atomic bombing was critically important to the Japanese decision to surrender would it have been enough to destroy one city?

- Would the Soviet declaration of war have been enough to compel Tokyo to admit defeat?

- Was the dropping of the atomic bombs morally justifiable?

This compilation will not attempt to answer these questions or use primary sources to stake out positions on any of them. Nor is it an attempt to substitute for the extraordinary rich literature on the atomic bombings and the end of World War II. Nor does it include any of the interviews, documents prepared after the events, and post-World War II correspondence, etc. that participants in the debate have brought to bear in framing their arguments. Originally this collection did not include documents on the origins and development of the Manhattan Project, although this updated posting includes some significant records for context. By providing access to a broad range of U.S. and Japanese documents, mainly from the spring and summer of 1945, interested readers can see for themselves the crucial source material that scholars have used to shape narrative accounts of the historical developments and to frame their arguments about the questions that have provoked controversy over the years. To help readers who are less familiar with the debates, commentary on some of the documents will point out, although far from comprehensively, some of the ways in which they have been interpreted. With direct access to the documents, readers may develop their own answers to the questions raised above. The documents may even provoke new questions.

Contributors to the historical controversy have deployed the documents selected here to support their arguments about the first use of nuclear weapons and the end of World War II. The editor has closely reviewed the footnotes and endnotes in a variety of articles and books and selected documents cited by participants on the various sides of the controversy. [5] While the editor has a point of view on the issues, to the greatest extent possible he has tried to not let that influence document selection, e.g., by selectively withholding or including documents that may buttress one point of view or the other. The task of compilation involved consultation of primary sources at the National Archives, mainly in Manhattan Project files held in the records of the Army Corps of Engineers, Record Group 77, but also in the archival records of the National Security Agency. Private collections were also important, such as the Henry L. Stimson Papers held at Yale University (although available on microfilm, for example, at the Library of Congress) and the papers of W. Averell Harriman at the Library of Congress. To a great extent the documents selected for this compilation have been declassified for years, even decades; the most recent declassifications were in the 1990s.

The U.S. documents cited here will be familiar to many knowledgeable readers on the Hiroshima-Nagasaki controversy and the history of the Manhattan Project. To provide a fuller picture of the transition from U.S.-Japanese antagonism to reconciliation, the editor has done what could be done within time and resource constraints to present information on the activities and points of view of Japanese policymakers and diplomats. This includes a number of formerly top secret summaries of intercepted Japanese diplomatic communications, which enable interested readers to form their own judgments about the direction of Japanese diplomacy in the weeks before the atomic bombings. Moreover, to shed light on the considerations that induced Japan’s surrender, this briefing book includes new translations of Japanese primary sources on crucial events, including accounts of the conferences on August 9 and 14, where Emperor Hirohito made decisions to accept Allied terms of surrender.

[ Editor’s Note: Originally prepared in July 2005 this posting has been updated, with new documents, changes in organization, and other editorial changes. As noted, some documents relating to the origins of the Manhattan Project have been included in addition to entries from the Robert P. Meiklejohn diaries and translations of a few Soviet documents, among other items. Moreover, recent significant contributions to the scholarly literature have been taken into account.]

I. Background on the U.S. Atomic Project

Documents 1A-C: Report of the Uranium Committee

1A . Arthur H. Compton, National Academy of Sciences Committee on Atomic Fission, to Frank Jewett, President, National Academy of Sciences, 17 May 1941, Secret

1B . Report to the President of the National Academy of Sciences by the Academy Committee on Uranium, 6 November 1941, Secret

1C . Vannevar Bush, Director, Office of Scientific Research and Development, to President Roosevelt, 27 November 1941, Secret

Source: National Archives, Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Record Group 227 (hereinafter RG 227), Bush-Conant papers microfilm collection, Roll 1, Target 2, Folder 1, "S-1 Historical File, Section A (1940-1941)."

This set of documents concerns the work of the Uranium Committee of the National Academy of Sciences, an exploratory project that was the lead-up to the actual production effort undertaken by the Manhattan Project. The initial report, May 1941, showed how leading American scientists grappled with the potential of nuclear energy for military purposes. At the outset, three possibilities were envisioned: radiological warfare, a power source for submarines and ships, and explosives. To produce material for any of those purposes required a capability to separate uranium isotopes in order to produce fissionable U-235. Also necessary for those capabilities was the production of a nuclear chain reaction. At the time of the first report, various methods for producing a chain reaction were envisioned and money was being budgeted to try them out.

Later that year, the Uranium Committee completed its report and OSRD Chairman Vannevar Bush reported the findings to President Roosevelt: As Bush emphasized, the U.S. findings were more conservative than those in the British MAUD report: the bomb would be somewhat “less effective,” would take longer to produce, and at a higher cost. One of the report’s key findings was that a fission bomb of superlatively destructive power will result from bringing quickly together a sufficient mass of element U235.” That was a certainty, “as sure as any untried prediction based upon theory and experiment can be.” The critically important task was to develop ways and means to separate highly enriched uranium from uranium-238. To get production going, Bush wanted to establish a “carefully chosen engineering group to study plans for possible production.” This was the basis of the Top Policy Group, or the S-1 Committee, which Bush and James B. Conant quickly established. [6]

In its discussion of the effects of an atomic weapon, the committee considered both blast and radiological damage. With respect to the latter, “It is possible that the destructive effects on life caused by the intense radioactivity of the products of the explosion may be as important as those of the explosion itself.” This insight was overlooked when top officials of the Manhattan Project considered the targeting of Japan during 1945. [7]

Documents 2A-B: Going Ahead with the Bomb

2A : Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt, 9 March 1942, with memo from Roosevelt attached, 11 March 1942, Secret

2B : Vannevar Bush to President Roosevelt, 16 December 1942, Secret (report not attached)

Sources: 2A: RG 227, Bush-Conant papers microfilm collection, Roll 1, Target 2, Folder 1, "S-1 Historical File, Section II (1941-1942): 2B: Bush-Conant papers, S-1 Historical File, Reports to and Conferences with the President (1942-1944)

The Manhattan Project never had an official charter establishing it and defining its mission, but these two documents are the functional equivalent of a charter, in terms of presidential approvals for the mission, not to mention for a huge budget. In a progress report, Bush told President Roosevelt that the bomb project was on a pilot plant basis, but not yet at the production stage. By the summer, once “production plants” would be at work, he proposed that the War Department take over the project. In reply, Roosevelt wrote a short memo endorsing Bush’s ideas as long as absolute secrecy could be maintained. According to Robert S. Norris, this was “the fateful decision” to turn over the atomic project to military control. [8]

Some months later, with the Manhattan Project already underway and under the direction of General Leslie Grove, Bush outlined to Roosevelt the effort necessary to produce six fission bombs. With the goal of having enough fissile material by the first half of 1945 to produce the bombs, Bush was worried that the Germans might get there first. Thus, he wanted Roosevelt’s instructions as to whether the project should be “vigorously pushed throughout.” Unlike the pilot plant proposal described above, Bush described a real production order for the bomb, at an estimated cost of a “serious figure”: $400 million, which was an optimistic projection given the eventual cost of $1.9 billion. To keep the secret, Bush wanted to avoid a “ruinous” appropriations request to Congress and asked Roosevelt to ask Congress for the necessary discretionary funds. Initialed by President Roosevelt (“VB OK FDR”), this may have been the closest that he came to a formal approval of the Manhattan Project.

Document 3 : Memorandum by Leslie R. Grove, “Policy Meeting, 5/5/43,” Top Secret

Source: National Archives, Record Group 77, Records of the Army Corps of Engineers (hereinafter RG 77), Manhattan Engineering District (MED), Minutes of the Military Policy Meeting (5 May 1943), Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 3, Target 6, Folder 23, “Military Policy Committee, Minutes of Meetings”

Before the Manhattan Project had produced any weapons, senior U.S. government officials had Japanese targets in mind. Besides discussing programmatic matters (e.g., status of gaseous diffusion plants, heavy water production for reactors, and staffing at Las Alamos), the participants agreed that the first use could be Japanese naval forces concentrated at Truk Harbor, an atoll in the Caroline Islands. If there was a misfire the weapon would be difficult for the Japanese to recover, which would not be the case if Tokyo was targeted. Targeting Germany was rejected because the Germans were considered more likely to “secure knowledge” from a defective weapon than the Japanese. That is, the United States could possibly be in danger if the Nazis acquired more knowledge about how to build a bomb. [9]

Document 4 : Memo from General Groves to the Chief of Staff [Marshall], “Atomic Fission Bombs – Present Status and Expected Progress,” 7 August 1944, Top Secret, excised copy

Source: RG 77, Correspondence ("Top Secret") of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, file 25M

This memorandum from General Groves to General Marshall captured how far the Manhattan Project had come in less than two years since Bush’s December 1942 report to President Roosevelt . Groves did not mention this but around the time he wrote this the Manhattan Project had working at its far-flung installations over 125,000 people ; taking into account high labor turnover some 485,000 people worked on the project (1 out of every 250 people in the country at that time). What these people were laboring to construct, directly or indirectly, were two types of weapons—a gun-type weapon using U-235 and an implosion weapon using plutonium (although the possibility of U-235 was also under consideration). As the scientists had learned, a gun-type weapon based on plutonium was “impossible” because that element had an “unexpected property”: spontaneous neutron emissions would cause the weapon to “fizzle.” [10] For both the gun-type and the implosion weapons, a production schedule had been established and both would be available during 1945. The discussion of weapons effects centered on blast damage models; radiation and other effects were overlooked.

Document 5 : Memorandum from Vannevar Bush and James B. Conant, Office of Scientific Research and Development, to Secretary of War, September 30, 1944, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, Harrison-Bundy Files (H-B Files), folder 69 (copy from microfilm)

While Groves worried about the engineering and production problems, key War Department advisers were becoming troubled over the diplomatic and political implications of these enormously powerful weapons and the dangers of a global nuclear arms race. Concerned that President Roosevelt had an overly “cavalier” belief about the possibility of maintaining a post-war Anglo-American atomic monopoly, Bush and Conant recognized the limits of secrecy and wanted to disabuse senior officials of the notion that an atomic monopoly was possible. To suggest alternatives, they drafted this memorandum about the importance of the international exchange of information and international inspection to stem dangerous nuclear competition. [11]

Documents 6A-D: President Truman Learns the Secret:

6A : Memorandum for the Secretary of War from General L. R. Groves, “Atomic Fission Bombs,” April 23, 1945

6B : Memorandum discussed with the President, April 25, 1945

6C : [Untitled memorandum by General L.R. Groves, April 25, 1945

6D : Diary Entry, April 25, 1945

Sources: A: RG 77, Commanding General’s file no. 24, tab D; B: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress); C: Source: Record Group 200, Papers of General Leslie R. Groves, Correspondence 1941-1970, box 3, “F”; D: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Soon after he was sworn in as president following President Roosevelt’s death, Harry Truman learned about the top secret Manhattan Project from a briefing from Secretary of War Stimson and Manhattan Project chief General Groves, who went through the “back door” to escape the watchful press. Stimson, who later wrote up the meeting in his diary, also prepared a discussion paper, which raised broader policy issues associated with the imminent possession of “the most terrible weapon ever known in human history.” In a background report prepared for the meeting, Groves provided a detailed overview of the bomb project from the raw materials to processing nuclear fuel to assembling the weapons to plans for using them, which were starting to crystallize.

With respect to the point about assembling the weapons, the first gun-type weapon “should be ready about 1 August 1945” while an implosion weapon would also be available that month. “The target is and was always expected to be Japan.” The question whether Truman “inherited assumptions” from the Roosevelt administration that that the bomb would be used has been a controversial one. Alperovitz and Sherwin have argued that Truman made “a real decision” to use the bomb on Japan by choosing “between various forms of diplomacy and warfare.” In contrast, Bernstein found that Truman “never questioned [the] assumption” that the bomb would and should be used. Norris also noted that “Truman’s `decision’ was a decision not to override previous plans to use the bomb.” [12]

II. Targeting Japan

Document 7 : Commander F. L. Ashworth to Major General L.R. Groves, “The Base of Operations of the 509 th Composite Group,” February 24, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g

The force of B-29 nuclear delivery vehicles that was being readied for first nuclear use—the Army Air Force’s 509 th Composite Group—required an operational base in the Western Pacific. In late February 1945, months before atomic bombs were ready for use, the high command selected Tinian, an island in the Northern Marianas Islands, for that base.

Document 8 : Headquarters XXI Bomber Command, “Tactical Mission Report, Mission No. 40 Flown 10 March 1945,”n.d., Secret

Source: Library of Congress, Curtis LeMay Papers, Box B-36

As part of the war with Japan, the Army Air Force waged a campaign to destroy major industrial centers with incendiary bombs. This document is General Curtis LeMay’s report on the firebombing of Tokyo--“the most destructive air raid in history”--which burned down over 16 square miles of the city, killed up to 100,000 civilians (the official figure was 83,793), injured more than 40,000, and made over 1 million homeless. [13] According to the “Foreword,” the purpose of the raid, which dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs, was to destroy industrial and strategic targets “ not to bomb indiscriminately civilian populations.” Air Force planners, however, did not distinguish civilian workers from the industrial and strategic structures that they were trying to destroy.

The killing of workers in the urban-industrial sector was one of the explicit goals of the air campaign against Japanese cities. According to a Joint Chiefs of Staff report on Japanese target systems, expected results from the bombing campaign included: “The absorption of man-hours in repair and relief; the dislocation of labor by casualty; the interruption of public services necessary to production, and above all the destruction of factories engaged in war industry.” While Stimson would later raise questions about the bombing of Japanese cities, he was largely disengaged from the details (as he was with atomic targeting). [14]

Firebombing raids on other cities followed Tokyo, including Osaka, Kobe, Yokahama, and Nagoya, but with fewer casualties (many civilians had fled the cities). For some historians, the urban fire-bombing strategy facilitated atomic targeting by creating a “new moral context,” in which earlier proscriptions against intentional targeting of civilians had eroded. [15]

Document 9 : Notes on Initial Meeting of Target Committee, May 2, 1945, Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5d (copy from microfilm)

On 27 April, military officers and nuclear scientists met to discuss bombing techniques, criteria for target selection, and overall mission requirements. The discussion of “available targets” included Hiroshima, the “largest untouched target not on the 21 st Bomber Command priority list.” But other targets were under consideration, including Yawata (northern Kyushu), Yokohama, and Tokyo (even though it was practically “rubble.”) The problem was that the Air Force had a policy of “laying waste” to Japan’s cities which created tension with the objective of reserving some urban targets for nuclear destruction. [16]

Document 10 : Memorandum from J. R. Oppenheimer to Brigadier General Farrell, May 11, 1945

Source: RG 77, MED Records, Top Secret Documents, File no. 5g (copy from microfilm)

As director of Los Alamos Laboratory, Oppenheimer’s priority was producing a deliverable bomb, but not so much the effects of the weapon on the people at the target. In keeping with General Groves’ emphasis on compartmentalization, the Manhattan Project experts on the effects of radiation on human biology were at the MetLab and other offices and had no interaction with the production and targeting units. In this short memorandum to Groves’ deputy, General Farrell, Oppenheimer explained the need for precautions because of the radiological dangers of a nuclear detonation. The initial radiation from the detonation would be fatal within a radius of about 6/10ths of a mile and “injurious” within a radius of a mile. The point was to keep the bombing mission crew safe; concern about radiation effects had no impact on targeting decisions. [17]

Document 11 : Memorandum from Major J. A. Derry and Dr. N.F. Ramsey to General L.R. Groves, “Summary of Target Committee Meetings on 10 and 11 May 1945,” May 12, 1945, Top Secret

Scientists and officers held further discussion of bombing mission requirements, including height of detonation, weather, radiation effects (Oppenheimer’s memo), plans for possible mission abort, and the various aspects of target selection, including priority cities (“a large urban area of more than three miles diameter”) and psychological dimension. As for target cities, the committee agreed that the following should be exempt from Army Air Force bombing so they would be available for nuclear targeting: Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura Arsenal. Japan’s cultural capital, Kyoto, would not stay on the list. Pressure from Secretary of War Stimson had already taken Kyoto off the list of targets for incendiary bombings and he would successfully object to the atomic bombing of that city. [18]

Document 12 : Stimson Diary Entries, May 14 and 15, 1945

Source: Henry Stimson Diary, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

On May 14 and 15, Stimson had several conversations involving S-1 (the atomic bomb); during a talk with Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, he estimated that possession of the bomb gave Washington a tremendous advantage—“held all the cards,” a “royal straight flush”-- in dealing with Moscow on post-war problems: “They can’t get along without our help and industries and we have coming into action a weapon which will be unique.” The next day a discussion of divergences with Moscow over the Far East made Stimson wonder whether the atomic bomb would be ready when Truman met with Stalin in July. If it was, he believed that the bomb would be the “master card” in U.S. diplomacy. This and other entries from the Stimson diary (as well as the entry from the Davies diary that follows) are important to arguments developed by Gar Alperovitz and Barton J. Bernstein, among others, although with significantly different emphases, that in light of controversies with the Soviet Union over Eastern Europe and other areas, top officials in the Truman administration believed that possessing the atomic bomb would provide them with significant leverage for inducing Moscow’s acquiescence in U.S. objectives. [19]

Document 13 : Davies Diary entry for May 21, 1945

Source: Joseph E. Davies Papers, Library of Congress, box 17, 21 May 1945

While officials at the Pentagon continued to look closely at the problem of atomic targets, President Truman, like Stimson, was thinking about the diplomatic implications of the bomb. During a conversation with Joseph E. Davies, a prominent Washington lawyer and former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Truman said that he wanted to delay talks with Stalin and Churchill until July when the first atomic device had been tested. Alperovitz treated this entry as evidence in support of the atomic diplomacy argument, but other historians, ranging from Robert Maddox to Gabriel Kolko, have denied that the timing of the Potsdam conference had anything to do with the goal of using the bomb to intimidate the Soviets. [20]

Document 14 : Letter, O. C. Brewster to President Truman, 24 May 1945, with note from Stimson to Marshall, 30 May 1945, attached, secret

Source: Harrison-Bundy Files relating to the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1108 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), File 77: "Interim Committee - International Control."

In what Stimson called the “letter of an honest man,” Oswald C. Brewster sent President Truman a profound analysis of the danger and unfeasibility of a U.S. atomic monopoly. [21] An engineer for the Kellex Corporation, which was involved in the gas diffusion project to enrich uranium, Brewster recognized that the objective was fissile material for a weapon. That goal, he feared, raised terrifying prospects with implications for the “inevitable destruction of our present day civilization.” Once the U.S. had used the bomb in combat other great powers would not tolerate a monopoly by any nation and the sole possessor would be “be the most hated and feared nation on earth.” Even the U.S.’s closest allies would want the bomb because “how could they know where our friendship might be five, ten, or twenty years hence.” Nuclear proliferation and arms races would be certain unless the U.S. worked toward international supervision and inspection of nuclear plants.

Brewster suggested that Japan could be used as a “target” for a “demonstration” of the bomb, which he did not further define. His implicit preference, however, was for non-use; he wrote that it would be better to take U.S. casualties in “conquering Japan” than “to bring upon the world the tragedy of unrestrained competitive production of this material.”

Document 15 : Minutes of Third Target Committee Meeting – Washington, May 28, 1945, Top Secret

More updates on training missions, target selection, and conditions required for successful detonation over the target. The target would be a city--either Hiroshima, Kyoto (still on the list), or Niigata--but specific “aiming points” would not be specified at that time nor would industrial “pin point” targets because they were likely to be on the “fringes” a city. The bomb would be dropped in the city’s center. “Pumpkins” referred to bright orange, pumpkin-shaped high explosive bombs—shaped like the “Fat Man” implosion weapon--used for bombing run test missions.

Document 16 : General Lauris Norstad to Commanding General, XXI Bomber Command, “509 th Composite Group; Special Functions,” May 29, 1945, Top Secret

The 509 th Composite Group’s cover story for its secret mission was the preparation of “Pumpkins” for use in battle. In this memorandum, Norstad reviewed the complex requirements for preparing B-29s and their crew for successful nuclear strikes.

Document 17 : Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy, “Memorandum of Conversation with General Marshal May 29, 1945 – 11:45 p.m.,” Top Secret

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson (“Safe File”), July 1940-September 1945, box 12, S-1

Tacitly dissenting from the Targeting Committee’s recommendations, Army Chief of Staff George Marshall argued for initial nuclear use against a clear-cut military target such as a “large naval installation.” If that did not work, manufacturing areas could be targeted, but only after warning their inhabitants. Marshall noted the “opprobrium which might follow from an ill considered employment of such force.” This document has played a role in arguments developed by Barton J. Bernstein that figures such as Marshall and Stimson were “caught between an older morality that opposed the intentional killing of non-combatants and a newer one that stressed virtually total war.” [22]

Document 18 : “Notes of the Interim Committee Meeting Thursday, 31 May 1945, 10:00 A.M. to 1:15 P.M. – 2:15 P.M. to 4:15 P.M., ” n.d., Top Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 100 (copy from microfilm)

With Secretary of War Stimson presiding, members of the committee heard reports on a variety of Manhattan Project issues, including the stages of development of the atomic project, problems of secrecy, the possibility of informing the Soviet Union, cooperation with “like-minded” powers, the military impact of the bomb on Japan, and the problem of “undesirable scientists.” Interested in producing the “greatest psychological effect,” the Committee members agreed that the “most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ houses.” Exactly how the mass deaths of civilians would persuade Japanese rulers to surrender was not discussed. Bernstein has argued that this target choice represented an uneasy endorsement of “terror bombing”--the target was not exclusively military or civilian; nevertheless, worker’s housing would include non-combatant men, women, and children. [23] It is possible that Truman was informed of such discussions and their conclusions, although he clung to a belief that the prospective targets were strictly military.

Document 19 : General George A. Lincoln to General Hull, June 4, 1945, enclosing draft, Top Secret

Source: Record Group 165, Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, American-British-Canadian Top Secret Correspondence, Box 504, “ABC 387 Japan (15 Feb. 45)

George A. Lincoln, chief of the Strategy and Policy Group at U.S. Army’s Operations Department, commented on a memorandum by former President Herbert Hoover that Stimson had passed on for analysis. Hoover proposed a compromise solution with Japan that would allow Tokyo to retain part of its empire in East Asia (including Korea and Japan) as a way to head off Soviet influence in the region. While Lincoln believed that the proposed peace teams were militarily acceptable he doubted that they were workable or that they could check Soviet “expansion” which he saw as an inescapable result of World War II. As to how the war with Japan would end, he saw it as “unpredictable,” but speculated that “it will take Russian entry into the war, combined with a landing, or imminent threat of a landing, on Japan proper by us, to convince them of the hopelessness of their situation.” Lincoln derided Hoover’s casualty estimate of 500,000. J. Samuel Walker has cited this document to make the point that “contrary to revisionist assertions, American policymakers in the summer of 1945 were far from certain that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria would be enough in itself to force a Japanese surrender.” [24]

Document 20 : Memorandum from R. Gordon Arneson, Interim Committee Secretary, to Mr. Harrison, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

In a memorandum to George Harrison, Stimson’s special assistant on Manhattan Project matters, Arneson noted actions taken at the recent Interim Committee meetings, including target criterion and an attack “without prior warning.”

Document 21 : Memorandum of Conference with the President, June 6, 1945, Top Secret

Source: Henry Stimson Papers, Sterling Library, Yale University (microfilm at Library of Congress)

Stimson and Truman began this meeting by discussing how they should handle a conflict with French President DeGaulle over the movement by French forces into Italian territory. (Truman finally cut off military aid to France to compel the French to pull back). [25] As evident from the discussion, Stimson strongly disliked de Gaulle whom he regarded as “psychopathic.” The conversation soon turned to the atomic bomb, with some discussion about plans to inform the Soviets but only after a successful test. Both agreed that the possibility of a nuclear “partnership” with Moscow would depend on “quid pro quos”: “the settlement of the Polish, Rumanian, Yugoslavian, and Manchurian problems.”

At the end, Stimson shared his doubts about targeting cities and killing civilians through area bombing because of its impact on the U.S.’s reputation as well as on the problem of finding targets for the atomic bomb. Barton Bernstein has also pointed to this as additional evidence of the influence on Stimson of an “an older morality.” While concerned about the U.S.’s reputation, Stimson did not want the Air Force to bomb Japanese cities so thoroughly that the “new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength,” a comment that made Truman laugh. The discussion of “area bombing” may have reminded him that Japanese civilians remained at risk from U.S. bombing operations.

III. Debates on Alternatives to First Use and Unconditional Surrender

Document 22 : Memorandum from Arthur B. Compton to the Secretary of War, enclosing “Memorandum on `Political and Social Problems,’ from Members of the `Metallurgical Laboratory’ of the University of Chicago,” June 12, 1945, Secret

Source: RG 77, MED Records, H-B files, folder no. 76 (copy from microfilm)

Physicists Leo Szilard and James Franck, a Nobel Prize winner, were on the staff of the “Metallurgical Laboratory” at the University of Chicago, a cover for the Manhattan Project program to produce fuel for the bomb. The outspoken Szilard was not involved in operational work on the bomb and General Groves kept him under surveillance but Met Lab director Arthur Compton found Szilard useful to have around. Concerned with the long-run implications of the bomb, Franck chaired a committee, in which Szilard and Eugene Rabinowitch were major contributors, that produced a report rejecting a surprise attack on Japan and recommended instead a demonstration of the bomb on the “desert or a barren island.” Arguing that a nuclear arms race “will be on in earnest not later than the morning after our first demonstration of the existence of nuclear weapons,” the committee saw international control as the alternative. That possibility would be difficult if the United States made first military use of the weapon. Compton raised doubts about the recommendations but urged Stimson to study the report. Martin Sherwin has argued that the Franck committee shared an important assumption with Truman et al.--that an “atomic attack against Japan would `shock’ the Russians”--but drew entirely different conclusions about the import of such a shock. [26]

Document 23 : Memorandum from Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew to the President, “Analysis of Memorandum Presented by Mr. Hoover,” June 13, 1945

Source: Record Group 107, Office of the Secretary of War, Formerly Top Secret Correspondence of Secretary of War Stimson (“Safe File”), July 1940-September 1945, box 8, Japan (After December 7/41)

A former ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew’s extensive knowledge of Japanese politics and culture informed his stance toward the concept of unconditional surrender. He believed it essential that the United States declare its intention to preserve the institution of the emperor. As he argued in this memorandum to President Truman, “failure on our part to clarify our intentions” on the status of the emperor “will insure prolongation of the war and cost a large number of human lives.” Documents like this have played a role in arguments developed by Alperovitz that Truman and his advisers had alternatives to using the bomb such as modifying unconditional surrender and that anti-Soviet considerations weighed most heavily in their thinking. By contrast, Herbert P. Bix has suggested that the Japanese leadership would “probably not” have surrendered if the Truman administration had spelled out the status of the emperor. [27]

Document 24 : Memorandum from Chief of Staff Marshall to the Secretary of War, 15 June 1945, enclosing “Memorandum of Comments on `Ending the Japanese War,’” prepared by George A. Lincoln, June 14, 1945, Top Secret

Commenting on another memorandum by Herbert Hoover, George A. Lincoln discussed war aims, face-saving proposals for Japan, and the nature of the proposed declaration to the Japanese government, including the problem of defining “unconditional surrender.” Lincoln argued against modifying the concept of unconditional surrender: if it is “phrased so as to invite negotiation” he saw risks of prolonging the war or a “compromise peace.” J. Samuel Walker has observed that those risks help explain why senior officials were unwilling to modify the demand for unconditional surrender. [28]

Document 25 : Memorandum by J. R. Oppenheimer, “Recommendations on the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons,” June 16, 1945, Top Secret

In a report to Stimson, Oppenheimer and colleagues on the scientific advisory panel--Arthur Compton, Ernest O. Lawrence, and Enrico Fermi—tacitly disagreed with the report of the “Met Lab” scientists. The panel argued for early military use but not before informing key allies about the atomic project to open a dialogue on “how we can cooperate in making this development contribute to improved international relations.”

Document 26 : “Minutes of Meeting Held at the White House on Monday, 18 June 1945 at 1530,” Top Secret