How to Write an Effective Claim (with Examples)

Formulating a claim for your essay can be difficult even if you are already a masterful debater — especially if you are not quite sure what a claim is, and how it may differ from a counterclaim or thesis statement. This guide will make it easy to decide on your claim!

Essay Claim Basics

In essay writing, a claim can most succinctly be defined as "a debatable statement" — which the writer then defends with supporting evidence and rhetoric. It is easy to confuse a claim and a thesis statement, because the thesis is indeed a type of claim as well. Essays can contain further claims that orbit the topic of the thesis statement, however.

Claims straddle the line between opinion and fact. If you're hoping to make a strong claim that seamlessly fits into a powerful essay, you will need to make sure that your claim ticks the right boxes:

- Your claim can debated — solid arguments can be made both in favor and against. Therefore, statements such as "I live in Queens" or "Joe Biden is the President" are not claims. In an argumentative essay, "the death penalty should be abolished" is an example of a claim. Even scientific papers make claims, such as "Keyboards contain more germs than toilet seats", which can be tested. These are called hypotheses.

- You will state your claim as a matter of fact. "Many people oppose the death penalty, and with good reason" is not a good claim, but "the death penalty is no longer an appropriate punishment in modern America" can be.

- Your claim is sufficiently specific to allow you to explore all aspects that you intend to tackle. "The Victorian era was Britain's darkest era" give you more bite than you can comfortably chew. "Fast food should be taxed to reduce obesity rates" is more specific.

Types of Claim (With Examples!)

Claims are debatable statements, but there are numerous different types. If you have specifically been asked to present a claim in an essay, you may be able to choose what kind of claim you would like to work with.

1. Claim of Fact or Definition

In research essays, a claim of fact or definition is one that defines a fact, as you see it, and proceeds to lay out the evidence in favor of the claim. Here are some examples to show you how it works:

- Plant species are becoming extinct at a faster rate than animal species, yet the plight of plants has been overlooked.

- Amazon's Alexa has revolutionized many people's daily lives — but this appliance also makes us vulnerable to new forms of hacking.

- Commercial air travel transformed the way in which we do business.

2. Claim of Cause & Effect

In a claim of cause and effect, you argue that one thing causes another, such as:

- Internet gaming has a widespread negative effect on students' grades.

- Lax enforcement of preventative measures against Covid has enabled the pandemic to continue for much longer than it need have.

- Playing jigsaw puzzles leads to novel cognitive connections that help senior citizens stay sharp.

3. Claim of Value

Claims of value are more heavily opinion-based than other types of claims. If you are making a claim of value, you will usually want to compare two things. For example:

- George W Bush was a better President than George W H Bush.

- Emotional health is just as important as physical health.

- Stephen King is the best horror writer of al time.

4. Claim of Solution or Policy

Claims of solution or policy state a position on a proposed course of action. In high school and college essays, they typically focus on something that should be done, or something that should no longer be done. Examples might include:

- Depressed patients should always be offered talk therapy before they receive a prescription for antidepressants.

- The United States should not accept refugees from Afghanistan.

- First-time offenders should be given lighter sentences.

Claim vs. Counterclaim vs. Thesis Statement

If you've been told to make an essay claim, you may be confused about the differences between a claim, counterclaim, and thesis statement. That's understandable, because some people believe that there's no difference between a claim and a thesis statement.

There are important distinctions between these three concepts, however, and if you want to write a killer essay, it's important to be aware of them:

- A thesis statement is the very foundation of your essay — everything else rests on it. The thesis statement should contain no more than one or two sentences, and summarize the heart of your argument. "Regular exercise has consistently been shown to increase productivity in the workplace. Therefore, employers should offer office workers, who would otherwise be largely sedentary, opportunities to work out."

- A claim is a statement you can defend with arguments and evidence. A thesis statement is a type of claim, but you'll want to include other claims that fit neatly into the subject matter as well. For instance, "Employers should establish gyms for employees."

- A counterclaim is a statement that contradicts, refutes, or opposes a claim. Why would you want to argue against yourself? You can do so to show that arguments that oppose the claim are weak. For instance, "Many employers would balk at the idea of facilitating costly exercise classes or providing a gym space — employees can work out in their own time, after all. Why should the boss pay for workers to engage in recreational activities at work? Recent studies have shown, however, that workplaces that have incorporated aerobics classes enjoy 120% increase in productivity, showing that this step serves the bottom line."

Together, a thesis statement, claims, and some well-placed counterclaims make up the threads of your story, leading to a coherent essay that is interesting to read.

How to Write an Effective Claim

Now that you've seen some examples, you are well on your way to writing an effective claim for your essay. Need some extra tips? We've got you covered.

First things first — how do you start a claim in an essay? Your claim sentence or sentences should be written in the active voice, starting with the subject, so that your readers can immediately understand what you are talking about.

They'll be formulated as an "[Subject] should be [proposed action], because [argument]. You can stay with this general structure while making different word choices, however, such as:

- It is about time that

- We have an obligation to

- Is the only logical choice

- It is imperative that

Once you have formulated a claim, you will want to see if you can hook your readers with an interesting or provocative statement that can really get them thinking. You will want to break your argument down into sections. This will lead you to sub-claims. If your claim is your main argument, your sub-claims are smaller arguments that work to support it. They will typically appear naturally once you contemplate the subject deeply — just brainstorm, and as you research, keep considering why your claim is true. The reasons you come up with will sprout sub-claims.

Still not sure what to write? Take a look at these examples of strong claim statements:

- A lack of work experience has proven to be the main barrier to finding satisfying employment, so businesses should be incentivized to hire recent graduates.

- The rise in uncertified "emotional support animals" directly causes suffering for people suffering from severe pet dander allergies. Such pets must be outlawed in public places to alleviate the very real harm allergy patients now experience on a daily basis.

- Emerging private space exploration ventures may be exciting, but they greatly increase CO2 emissions. At a time when the planet is in crisis, private space exploration should be banned.

Additional Tips in Writing a Claim the Right Way

You now know what you need to include in a claim paragraph to leave a strong impression. Understanding what not to do is equally important, however.

- Take a stand — if you're writing an argumentative essay, it is perfectly OK to take a controversial opinion, and no matter what you write, it is bound to have the potential to offend someone . Don't sit on the fence. Even when you're defending a position you disagree with, embrace it wholeheartedly.

- Narrow your claim down. The more specific you can get, the more compelling your argument can be, and the more depth you can add to each aspect of your argument.

- Have fun! You want your essay to be interesting to read, and any genuine passion you have will be apparent.

- Choose the right subject — one about which you can find a lot of data and facts.

What should you avoid in writing a claim, you wonder? Don't:

- Use any first-person statements. The claim is about your ideas, not about you.

- Base your claim on emotional appeal. You can work some pathos in, but don't make feelings your center.

- Clutter your claim with too many separate ideas, which will make the rest of your essay harder to read, less powerful, and unwieldy for you to develop.

How do you use a claim?

When you're writing your essay, you can think of the thesis statement as the spine. The claims you make are, then, your "ribs", so to speak. If you prefer a different analogy, the thesis is your trunk, and the claims branches. You use them to build a strong final product that shows you have considered all aspects of your argument, and can back them up with evidence and logic.

What is a good way to start a claim?

You can start with a shocking fact, objective data from a reliable source, or even an anecdote — or, if you prefer, you can simply offer your argument without bells and whistles.

Can a claim be in a paragraph or is it a single sentence only?

Claims are almost always limited to a single sentence. It can be a long compound sentence, though! The claim does not have to remain all alone in the paragraph. You can immediately surround it with rhetorical punches or further facts.

What are some examples of argumentative claims?

So, you want to learn to argue like a pro? Watching speeches politicians make is a great way to look out for claims, and court transcripts and academic debates are two other places you can look for great argumentative claims.

Is there a claim generator you can use?

Yes! Some claim generators are free to use, while others require a subscription. These tools can be interesting to play with, and can serve as inspiration. However, it's always best to tweak your final claim to fit your needs.

Related posts:

- Bone of Contention - Meaning, Usage and Origin

- I Beg to Differ - Meaning, Origin and Usage

- Chewing the Fat - Meaning, Usage and Origin

- All that Glitters is Not Gold - Meaning, Origin and Usage

- Ginning Up - Meaning, Usage and Origin

- Chime In - Meaning, Origin and Usage

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Writing Guide

- Assignment Writing

How to Write a Claim

- What is a claim in a thesis?

Types of claim used in the thesis

How to craft a great claim statement.

- How to write your claim in a right way

What is a claim in a thesis?

Cause and effect, the claim of solutions or policies, factual or definitive.

Read also: Find research paper writers hire services to take care of your papers.

Claim of value

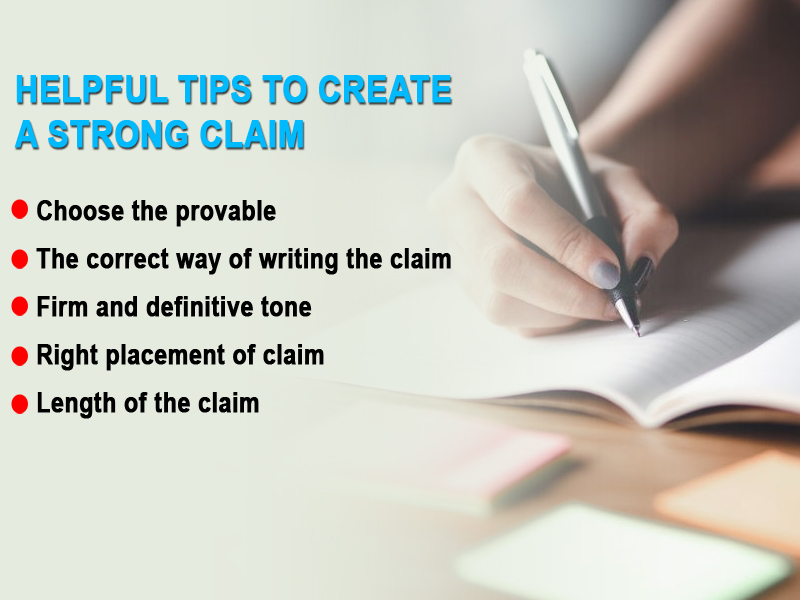

Choose and explore the topic of your interest, set a question and answer it with your thesis.

Read also: A reliable thesis statement maker will help you create a perfect thesis.

Define a goal of your paper

Take a stand for a single issue, take a different approach to the topic, write your claim in a right way, choose what you can prove, write your claim in a correct way, use a definitive yet firm tone.

Useful information: Dissertation writers for hire will help you complete your dissertation.

Place your claim in a proper place

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Get a 50% off

Study smarter with Chegg and save your time and money today!

Nathaniel Tower

Juggling writing and life

Understanding Claims in Writing and How to Craft Effective Ones

Last Updated on July 7, 2023 by Nathaniel Tower

In the realm of academic and persuasive writing, a claim holds significant importance. A claim serves as the central assertion or argument made by a writer to support their position or viewpoint. It is the backbone of an essay or any piece of writing, providing a clear focus and direction for the reader. Crafting a strong claim requires careful thought, analysis, and supporting evidence. In this article, we will delve into the concept of claims in writing and explore effective strategies for constructing compelling and persuasive claims.

What is a Claim?

A claim is a declarative statement that expresses the writer’s position or viewpoint on a particular subject. It is often referred to as a thesis statement or central argument. A well-crafted claim should be concise, specific, and debatable. It presents an opinion or interpretation that can be supported or challenged through logical reasoning and evidence.

Claims can take various forms, including factual claims that present verifiable information, value claims that express opinions about what is good or bad, and policy claims that propose specific courses of action. Regardless of the type, a claim should be formulated in a way that engages the reader and compels them to consider the writer’s perspective.

How to Write an Effective Claim

- Revise and Refine : Once you have drafted your claim, review and revise it to ensure clarity and effectiveness. Check for any logical fallacies, inconsistencies, or weak points in your argument. Seek feedback from peers or instructors to gain different perspectives and improve your claim.

What is a counterclaim in writing?

In writing, a counterclaim refers to a rebuttal or opposing argument presented by the writer to challenge or refute the main claim or thesis statement. It serves as a counterargument that acknowledges the opposing viewpoint and attempts to undermine its credibility or validity. A counterclaim adds depth and complexity to an argument by considering different perspectives and engaging in a more comprehensive analysis of the topic.

When constructing a counterclaim, it is essential to present a strong and logical argument that challenges the original claim. This entails conducting thorough research, gathering evidence, and providing convincing reasoning to support the counterargument. By doing so, the writer demonstrates their ability to critically evaluate multiple viewpoints and engage in a balanced discussion.

A well-crafted counterclaim should address the opposing side’s key points, highlight any weaknesses or fallacies in their argument, and provide a compelling alternative perspective. It is crucial to maintain a respectful tone and avoid personal attacks or derogatory language while presenting the counterclaim. Instead, focus on presenting a coherent and evidence-based argument that can effectively challenge the original claim.

In addition to presenting the counterclaim, it is essential to refute the opposing viewpoint by offering counter-evidence or providing a different interpretation of the existing evidence. This helps strengthen the writer’s position and credibility by demonstrating a comprehensive understanding of the topic and a willingness to engage with alternative perspectives.

By including a counterclaim in their writing, the author not only acknowledges the complexity of the issue but also shows a commitment to intellectual rigor and fairness. It encourages readers to consider multiple viewpoints, critically evaluate arguments, and arrive at a well-informed conclusion. In academic writing, including counterclaims demonstrates the writer’s ability to engage in scholarly discourse and contributes to the overall quality and credibility of the work.

Conclusion

Crafting a strong claim is essential for writing compelling and persuasive pieces. A well-constructed claim provides a clear focus and direction, engages the reader, and supports the writer’s position or viewpoint. By understanding the purpose of your writing, conducting thorough research, formulating a clear claim, providing evidence, and considering counterarguments, you can create a robust claim that strengthens your overall argument. Remember to revise and refine your claim to ensure its effectiveness. With a well-crafted claim, you can captivate your audience and present a convincing argument in your writing.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Privacy overview.

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that he or she will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove her point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, he or she still has to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and she already knows everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality she or he expects.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Understanding Writing Assignments

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How to Decipher the Paper Assignment

Many instructors write their assignment prompts differently. By following a few steps, you can better understand the requirements for the assignment. The best way, as always, is to ask the instructor about anything confusing.

- Read the prompt the entire way through once. This gives you an overall view of what is going on.

- Underline or circle the portions that you absolutely must know. This information may include due date, research (source) requirements, page length, and format (MLA, APA, CMS).

- Underline or circle important phrases. You should know your instructor at least a little by now - what phrases do they use in class? Does he repeatedly say a specific word? If these are in the prompt, you know the instructor wants you to use them in the assignment.

- Think about how you will address the prompt. The prompt contains clues on how to write the assignment. Your instructor will often describe the ideas they want discussed either in questions, in bullet points, or in the text of the prompt. Think about each of these sentences and number them so that you can write a paragraph or section of your essay on that portion if necessary.

- Rank ideas in descending order, from most important to least important. Instructors may include more questions or talking points than you can cover in your assignment, so rank them in the order you think is more important. One area of the prompt may be more interesting to you than another.

- Ask your instructor questions if you have any.

After you are finished with these steps, ask yourself the following:

- What is the purpose of this assignment? Is my purpose to provide information without forming an argument, to construct an argument based on research, or analyze a poem and discuss its imagery?

- Who is my audience? Is my instructor my only audience? Who else might read this? Will it be posted online? What are my readers' needs and expectations?

- What resources do I need to begin work? Do I need to conduct literature (hermeneutic or historical) research, or do I need to review important literature on the topic and then conduct empirical research, such as a survey or an observation? How many sources are required?

- Who - beyond my instructor - can I contact to help me if I have questions? Do you have a writing lab or student service center that offers tutorials in writing?

(Notes on prompts made in blue )

Poster or Song Analysis: Poster or Song? Poster!

Goals : To systematically consider the rhetorical choices made in either a poster or a song. She says that all the time.

Things to Consider: ah- talking points

- how the poster addresses its audience and is affected by context I'll do this first - 1.

- general layout, use of color, contours of light and shade, etc.

- use of contrast, alignment, repetition, and proximity C.A.R.P. They say that, too. I'll do this third - 3.

- the point of view the viewer is invited to take, poses of figures in the poster, etc. any text that may be present

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing I'll cover this second - 2.

- ethical implications

- how the poster affects us emotionally, or what mood it evokes

- the poster's implicit argument and its effectiveness said that was important in class, so I'll discuss this last - 4.

- how the song addresses its audience

- lyrics: how they rhyme, repeat, what they say

- use of music, tempo, different instruments

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing

- emotional effects

- the implicit argument and its effectiveness

These thinking points are not a step-by-step guideline on how to write your paper; instead, they are various means through which you can approach the subject. I do expect to see at least a few of them addressed, and there are other aspects that may be pertinent to your choice that have not been included in these lists. You will want to find a central idea and base your argument around that. Additionally, you must include a copy of the poster or song that you are working with. Really important!

I will be your audience. This is a formal paper, and you should use academic conventions throughout.

Length: 4 pages Format: Typed, double-spaced, 10-12 point Times New Roman, 1 inch margins I need to remember the format stuff. I messed this up last time =(

Academic Argument Essay

5-7 pages, Times New Roman 12 pt. font, 1 inch margins.

Minimum of five cited sources: 3 must be from academic journals or books

- Design Plan due: Thurs. 10/19

- Rough Draft due: Monday 10/30

- Final Draft due: Thurs. 11/9

Remember this! I missed the deadline last time

The design plan is simply a statement of purpose, as described on pages 40-41 of the book, and an outline. The outline may be formal, as we discussed in class, or a printout of an Open Mind project. It must be a minimum of 1 page typed information, plus 1 page outline.

This project is an expansion of your opinion editorial. While you should avoid repeating any of your exact phrases from Project 2, you may reuse some of the same ideas. Your topic should be similar. You must use research to support your position, and you must also demonstrate a fairly thorough knowledge of any opposing position(s). 2 things to do - my position and the opposite.

Your essay should begin with an introduction that encapsulates your topic and indicates 1 the general trajectory of your argument. You need to have a discernable thesis that appears early in your paper. Your conclusion should restate the thesis in different words, 2 and then draw some additional meaningful analysis out of the developments of your argument. Think of this as a "so what" factor. What are some implications for the future, relating to your topic? What does all this (what you have argued) mean for society, or for the section of it to which your argument pertains? A good conclusion moves outside the topic in the paper and deals with a larger issue.

You should spend at least one paragraph acknowledging and describing the opposing position in a manner that is respectful and honestly representative of the opposition’s 3 views. The counterargument does not need to occur in a certain area, but generally begins or ends your argument. Asserting and attempting to prove each aspect of your argument’s structure should comprise the majority of your paper. Ask yourself what your argument assumes and what must be proven in order to validate your claims. Then go step-by-step, paragraph-by-paragraph, addressing each facet of your position. Most important part!

Finally, pay attention to readability . Just because this is a research paper does not mean that it has to be boring. Use examples and allow your opinion to show through word choice and tone. Proofread before you turn in the paper. Your audience is generally the academic community and specifically me, as a representative of that community. Ok, They want this to be easy to read, to contain examples I find, and they want it to be grammatically correct. I can visit the tutoring center if I get stuck, or I can email the OWL Email Tutors short questions if I have any more problems.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.17: Discussion- Thesis Statements and Supporting Claims Assignment

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58274

- Lumen Learning

Select a reading from The Conversation website . Use the categories at the top of the page or the search bar to find something that sounds interesting to you. Include the URL to the website in your post.

First, read through the article and get a feel for what it’s about. Write a sentence about the main message of the article. After writing this sentence, go back to the text. Is there a sentence in the text that says something very similar to what you wrote down? This is likely the thesis statement.

STEP 1 : Identify this reading’s thesis. Is it an explicit or implicit thesis? If it’s explicit, include the sentence from the text as a quote that you identify as the thesis. If it’s implicit, describe why you feel the author chose not to put an explicit thesis in the work. Describe your thoughts about it—is it a good thesis statement?

STEP 2 : Next, write a paragraph that describes how the thesis relates to the topic sentences of at least two of the paragraphs. Include 2 topic sentences as quotes, and explain each’s relationship to the thesis.

STEP 3 : Write a paragraph that identifies the type of support that each paragraph from the reading uses to reinforce each of those 2 topic sentences. Are they narrative or personal examples? Are they facts or statistics? Are they quotes or paraphrases from research materials? What makes them effective or ineffective?

STEP 4 : Respond in a separate post to at least one classmate (in at least 75 words). Explicitly address their examples and try to extend, complicate, or redirect their points in a substantive, knowledge-demonstrating way. Be sure to cite relevant concepts and key terms from the module.

Contributors and Attributions

- Assignment: Thesis. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

It's Lit Teaching

High School English and TPT Seller Resources

- Creative Writing

- Teachers Pay Teachers Tips

- Shop My Teaching Resources!

- Sell on TPT

Claim, Evidence, Reasoning: What You Need to Know

Has an instructional coach or administrator told you to start using a claim, evidence, and reasoning (or C-E-R) framework for writing in your classroom?

Maybe you need to closely adhere to the Common Core State Standards but aren’t quite sure where to begin.

If you’re like me, your whole school may be committing to using a C-E-R language in all classes to build consistency and teacher equity for students.

Regardless, here you are wondering, what the heck is claim, evidence, and reasoning anyway ? In this post, I aim to break it down for you.

There are plenty of science examples out there, but that is not my specialty. For this post, I’ll focus on my subject area, high school English, but know that the C-E-R framework can be applied to multiple content areas.

If you’d like to teach the C-E-R writing framework to your students, I have a whole bundle of resources right here.

C-E-R (Claim, Evidence, Reasoning) Writing Overview

C-E-R writing is a framework that consists of three parts: Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning. Science classes use it frequently, but it works well in any content area. In fact, my entire school uses it–down to the gym classes!

A C-E-R writing framework works especially well for teachers adhering to the Common Core State Standards. The words “claim”, “evidence”, and “reasoning” are directly from the standards themselves.

C-E-R writing works especially well for argumentative or persuasive writing, but also holds true for research-based writing.

Note that these are academic forms of writing. You wouldn’t, for instance, probably use claims, evidence, or reasoning in a creative writing class or with a narrative or poetry unit.

While C-E-R may seem formulaic at first, it does come from a natural flow of solid arguments. Any attempt at persuasion must take a stance, support it with logic, and make a case.

The formulaic nature of C-E-R writing makes it a helpful writing scaffold for students who struggle to organize their ideas or generate them in the first place.

The claim sets the tone for the rest of the writing.

It is the argument, the stance, or the main idea of the writing that is to follow. Some may say that in C-E-R writing, the claim is the most important piece.

I have found that the placement and length of the claim will vary according to the length of the writing.

For a paragraph, I feel the claim makes a great topic sentence and thus, should be the first sentence. The body of the paragraph then will aim to support the topic sentence (or claim).

In a standard five-paragraph essay , the first introductory paragraph may build to the claim: the thesis. The body paragraphs then will each contain a sub-claim so-to-speak that supports the overarching claim or thesis.

Claims, while logical, should present an arguable stance on a topic.

I often have to remind my students that if they are writing in response to a question, restating the question in the form of a sentence and adding their answer is an easy way to write a claim.

A Claim Example for an English Class

Let’s use a Shakespearian example. A popular essay topic when reading Romeo and Juliet poses the following question: who is to blame for the deaths of Romeo and Juliet?

A claim that answers this question might read:

“Friar Laurence is most to blame for Romeo and Juliet’s deaths.”

This claim is strong for multiple reasons. First, it is direct. There’s no question about what the rest of the writing will be about or will be attempting to support. Second, this claim is arguable –not provable–but also logical. The idea can be supported by examples from the text.

A claim is not a fact. Evidence should support it, which we’ll discuss in a moment, but ultimately, it should not be something that can be proven .

The next step in the C-E-R writing framework is evidence.

Evidence is the logic, proof, or support that you have for your claim. I mentioned earlier that your claim, while arguable, should be rooted in logic. Evidence is where you present the logic you used to arrive at your claim.

This can take a variety of forms: research, facts, observations, lab experiments, or even quotes from interviews or authorities.

For literary analysis, evidence should generally be textual in nature.

That is, the evidence should be rooted–if not directly quoted from–in the text. For example, the writer may want to use quotes, paraphrasing, or a summary of events from the text.

I encourage my students to use word-for-word textual evidence quoted and cited from the text directly. This creates evidence with which it is difficult to argue.

An Evidence Example for an English Class

If we continue with the Romeo and Juliet example, we could support our previous claim that Friar Laurence is most to blame for the couple’s death by presenting several pieces of evidence from the play.

Our evidence may then read as follows:

“ In the play, Friar Laurence says to Juliet, ‘Take thou this vial, being then in bed/ And this distilled liquor drink thou off;/ …The roses in thy lips and cheeks shall fade/ … And in this borrow’d likeness of shrunk death/ Thou shalt continue two and forty hours,/And then awake as from a pleasant sleep ’ (4.1.93-106).”

This is strong evidence because the text proves it. This quote comes directly from Shakespeare; you can’t argue with it.

It is also on-topic. it shows a piece of the play that supports the idea that Friar Laurence is most to blame for Romeo and Juliet’s deaths.

For claim, evidence, and reasoning writing, the strength of the argument depends on its evidence.

Grab a FREE Copy of Must-Have Classroom Library Title!

Sign-up for a FREE copy of my must-have titles for your classroom library and regular updates to It’s Lit Teaching! Insiders get the scoop on new blog posts, teaching resources, and the occasional pep talk!

Marketing Permissions

I just want to make sure you’re cool with the things I may send you!

By clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provide will be processed in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

Reasoning is the thinking behind the evidence that led to the claim. It should explain the evidence if necessary, and then connect it to the claim.

In a one paragraph response, I usually recommend that students break down their reasoning into three sentences:

Personally, this is where my students struggle the most. They have a hard time understanding how to explain the evidence or connect it to their claim because it’s obvious to them.

- Explain or summarize the evidence that was just used

- Explain or show how this evidence supports the claim

- Finish with a conclusion sentence

If your students, like mine, struggle with crafting reasoning, I recommend giving them sentence starters like “This shows that…” or “This quote proves that….”

I also go over different ways to approach writing conclusion sentences, as my students often struggle in ending their writing.

(If you’d like help breaking this down for your students, my C-E-R Slideshow covers reasoning–including what to include and three different ways to write a conclusion sentence.)

A Reasoning Example for An English Class

For our Romeo and Juliet example, it may read something like this:

“This quote shows that Friar Laurence is the originator of the plan for the two lovers to fake their deaths. Had he not posed this plan, Romeo could not have mistaken Juliet for dead. Thus, he would never have committed suicide, nor Juliet. As the adult in the situation, Friar Laurence should have acted less rashly and helped the couple find a more suitable solution to their problems.”

This reasoning is strong for several reasons.

First, note the transition in the beginning. It discusses the textual evidence–the quote presented earlier–directly and explains what is happening in the quote.

Next, it walks the reader step-by-step through the writer’s rationale about the evidence that led her to believe the claim. Even if the reader does not agree with the reader’s claim, he or she must concede that the writer has a point.

You may have noticed that in this example, the reasoning tends to be longer than either the claim or the evidence. The length of the reasoning will vary according to the assignment, but I have found that good reasoning does tend to be the bulk of C-E-R writing.

Get Started with Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning Today!

And there you have it! An overview of the C-E-R writing framework. No doubt, you can see how this framework can easily be applied to a myriad of assignments in any content area.

If you need help getting started in using the C-E-R writing framework in your English class, I have a few resources in my Teachers Pay Teachers store that can help you. Check them out! Start with a FREE student guide to claim, evidence, and reasoning!

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

50 Fun Earth Day Crafts and Activities 🌎!

How I Teach Students to Write Historical Arguments

A world history teacher breaks it down step by step.

It never occurred to me that, as a high school history teacher, I would need to teach students how to write. But with students who struggle with writing in general and who have never really written in a history class, it became part of my job description. The writing we do in my world history class is based on a claim and supported with evidence. This is the process I use to teach students to write historical arguments.

Note: Most of what I do comes from the College, Career and Community Writers Program (C3WP) , a part of the National Writing Project. I did some training with the Oregon Writers Project in this Program and without it I would have no idea how to teach argument writing. I am so grateful for this program.

Step 1: Gather information

Historical arguments come at the end of a unit. Students have spent time with the material that they will be writing about. For example, the first writing assignment they do is a paragraph about which map projection schools should use to teach geography. Before writing, we explore various map projections, go over the pros and cons, and read about the map projections. By the time they write, students have a lot of information to form a claim and to use for evidence.

Step 2: Form an opinion

My students often struggle to form opinions about the topics we are studying. So, I have built opinion formation and discussion into my lesson structure. We have discussions about why things happened the way they did, how things could have happened differently, etc. We have these discussions throughout the year, so students practice forming opinions and using evidence to support those opinions.

For example, in early units we look at European exploration and imperialism. This unit does not end with a full-blown writing assignment, but conversations about how the world might be different without imperialism exist throughout the units. They become comfortable having these conversations and figuring out what they think about a topic. (I use guidance from Constructing Meaning and AVID to help them learn to talk to each other.)

Step 3: Make a claim

I teach writing claims, or thesis statements, first using tools from C3WP. Claims are “debatable and defensible,” meaning they are not a fact and they can be backed up with evidence. I spend a lot of time focusing on the “because” of the thesis: they must include why in their claim. So, they can’t just say, ”School should start later.” Instead, it must be something like “School short start later because students need more sleep to succeed in school.” We go through several “claim” statements to determine if they are actually claims or not. Then we rewrite them to make them better. Next, we build a claim together around a topic we are discussing in class.

At the beginning of the year, I give students a sentence frame like this one:

“Schools should use ___________________ map projection because ______________ and _____________.”

As the year goes on, claims get more nuanced. We start to acknowledge other perspectives and make claims more specific.

Step 4: Provide evidence

Since claims are laid out with specific reasons to support the opinion, these reasons become the evidence. I label them as Reason 1, Reason 2 and Reason 3 and each reason is discussed specifically after the claim. In a paragraph writing assignment, they write from one reason to the next with phrases like “another reason,” “also,” and “finally” to link the reasons together.

When students write full essays, each reason gets its own paragraph. Reason one becomes the topic of the first body paragraph, reason two becomes the second body paragraph, etc. I use the following outline to help students write body paragraphs:

- Sentence 1: First reason from claim

- Sentence 2: Quote or summarize a piece of evidence that supports your reason

- Sentence 3: Explain how this evidence supports your reason

- Sentence 4: Quote or summarize a piece of evidence that supports your reason

- Sentence 5: Explain how this evidence supports your reason

- Sentence 6: Restate your reason from your claim

More sentences can be added for more evidence or explanation, but this basic layout helps kids feel like they know what to do.

Extensions and struggles

This is a very basic outline of how I teach students to write historical arguments. It is meant to be a starting point. Eventually, students start creating more nuanced claims, looking at opposing arguments, justifying evidence sources, etc.

Student evidence can be a problem. To begin, I have them only use sources from class. That way, I know the information is correct and they should know how the material we used in class can support their claims. I find that beginning writers often can’t connect something they find online to discussions we’ve had in class.

Students also may struggle with explaining evidence. They think that just quoting a source proves their point. They need to be shown how to connect evidence to a claim with an explanation.

I’ve had pretty good luck with this format of teaching writing, but I’d love to hear your ideas, too!

How do you teach students to write historical arguments? Come and share your ideas in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, slam-dunk argumentative writing prompts for high school.

You Might Also Like

250+ Best Would You Rather Questions for Kids

Activate endless participation and spark curiosity. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Article III, Section 2, Clause 1:

The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority;—to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls;—to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party;—to Controversies between two or more States; between a State and Citizens of another State, between Citizens of different States,—between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

An assignment of a legal claim occurs when one party (the “assignor” ) transfers its rights in a cause of action to another party (the “assignee” ). 1 Footnote Black’s Law Dictionary 136 (9th ed. 2009) (defining “assignment” as “the transfer of rights or property” ). The Supreme Court has held that a private litigant may have standing to sue to redress an injury to another party when the injured party has assigned at least a portion of its claim for damages from that injury to the litigant. The Supreme Court in the 2000 case Vermont Agency of Natural Resources v. United States ex rel. Stevens held that private individuals may have Article III standing to bring a qui tam civil action in federal court under the federal False Claims Act (FCA) on behalf of the federal government if authorized to do so. 2 Footnote 529 U.S. 765, 768, 778 (2000) . The FCA imposes civil liability upon “any person” who, among other things, knowingly presents to the federal government a false or fraudulent claim for payment. 3 Footnote 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a) . To encourage citizens to enforce the Act, in certain circumstances, a private individual, known as a “relator,” may bring a civil action for violations of the Act. Such plaintiffs sue under the name of the United States and may receive a share of any recovered proceeds from the action. 4 Footnote Id. § 3730(d)(1)–(2) . Under the FCA, the relator is not merely the agent of the United States but an individual with an interest in the lawsuit itself. 5 Footnote Vt. Agency of Nat. Res. , 529 U.S. at 772 ( “For the portion of the recovery retained by the relator . . . some explanation of standing other than agency for the Government must be identified.” ) (citing 31 U.S.C. § 3730 ).

Ordinarily, if the relator’s financial interest in the outcome of the case were merely a byproduct of the suit itself, there would be no injury sufficient for standing. 6 Footnote Id. at 772–73 ( “An interest unrelated to injury in fact is insufficient to give a plaintiff standing. . . . A qui tam relator has suffered no [invasion of a legally protected right]—indeed, the ‘right’ he seeks to vindicate does not even fully materialize until the litigation is completed and the relator prevails.” ) (citations omitted). The Supreme Court has held that a litigant’s interest in recovering attorneys’ fees or the costs of bringing suit by itself normally does not confer standing to sue. E.g. Steel Co. v. Citizens for a Better Env’t, 523 U.S. 83, 107 (1998) ( “The litigation must give the plaintiff some other benefit besides reimbursement of costs that are a byproduct of the litigation itself.” ); Diamond v. Charles, 476 U.S. 54, 70–71 (1986) ( “[T]he mere fact that continued adjudication would provide a remedy for an injury that is only a byproduct of the suit itself does not mean that the injury is cognizable under Art. III.” ). In Stevens , however, the Supreme Court recognized a distinction that confers standing upon qui tam plaintiffs in FCA cases. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the Court, determined that assignments of claims are distinguishable from cases in which a litigant has a mere financial interest in the outcome of the suit because the assignee-plaintiff actually owns a stake in the dispute as a legal matter. 7 Footnote Vt. Agency of Nat. Res. , 529 U.S. at 773 . Justice Scalia drew support for this distinction from the long-standing historical practice of the government assigning a portion of its damages claim to a private party and allowing that party to assert the injury suffered by the federal government as a representative of the United States. 8 Footnote Id. at 774, 778 The Court noted the “long tradition of qui tam actions in England and the American colonies,” 9 Footnote Id. concluding that “Article III’s restriction of the judicial power to ‘Cases’ and ‘Controversies’ is properly understood to mean ‘cases and controversies of the sort traditionally amenable to, and resolved by, the judicial process.’” 10 Footnote Id. Although the Court held that the relator had standing to sue under the qui tam provision, it ultimately determined that the plaintiff could not maintain the action against a state agency for allegedly submitting false grant claims to the EPA because states were not “persons” subject to liability under the False Claims Act. Id. at 787 .

Eight years after deciding Stevens , the Supreme Court again found that an assignee of a claim had standing, even when the assignee had promised to remit all of the money it recovered in the proceedings to the assignor. 11 Footnote Sprint Commc’ns Co. v. APCC Servs., Inc. , 554 U.S. 269 , 271 (2008) . In Sprint Communications Co. v. APCC Services, Inc. , payphone operators had assigned their legal claims for money owed to them by long-distance communications carriers to third-party collection agencies. 12 Footnote Id. at 271–72 . The agencies were authorized to bring suit on behalf of the payphone operators and promised to pay all of the proceeds of the litigation to the payphone operators for a fee. 13 Footnote Id. at 272 . The Court held that these collection agencies had standing to pursue the operators’ claims because of the long history of courts’ acceptance of such claims. 14 Footnote Id. at 273–75 . The Court noted that “federal courts routinely entertain suits which will result in relief for parties that are not themselves directly bringing suit. Trustees bring suits to benefit their trusts; guardians ad litem bring suits to benefit their wards; receivers bring suit to benefit their receiverships; assignees in bankruptcy bring suit to benefit bankrupt estates; executors bring suit to benefit testator estates; and so forth.” Id. at 287–88 . Assignment was sufficient to transfer the injury to the collections agencies, and the injury to the operators that had been transferred to the collection agencies would be redressed by a favorable judicial decision, even if the agencies would subsequently pay all of the proceeds to the operators. 15 Footnote Id. at 286–87 ( “[I]f the [collection agencies] prevail in this litigation, the long-distance carriers would write a check to [them] for the amount of dial-around compensation owed. What does it matter what the [agencies] do with the money afterward?” ).

The Stevens and Sprint cases could have broader implications for Article III standing doctrine, as they suggest a way in which the constitutional limitations on standing may be bypassed through the assignment of rights to a third party. 16 Footnote See also ArtIII.S2.C1.6.4.3 Particularized Injury. For instance, if Congress enacts a federal statute recognizing an injury to the federal government that otherwise satisfies Article III’s requirements, it may assign a portion of its claim to a private party, thereby potentially giving that plaintiff standing to sue as a representative of the United States. 17 Footnote See Vt. Agency of Nat. Res. , 529 U.S. at 773 . This is essentially the operation of the False Claims Act. 18 Footnote 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729–3733 . However, it is unclear whether every such statute would necessarily resolve all Article III standing concerns. In Stevens and Sprint , the Court gave significant weight to the lengthy history of courts recognizing the types of assignments at issue when determining that the litigants in those cases had standing to sue. 19 Footnote See id. at 774, 778 ; Sprint Commc’ns Co. , 554 U.S. at 273–75 . Moreover, there may be a number of concerns about the constitutionality and practicality of using assignments to delegate core government functions (e.g., criminal prosecutions) to private parties when courts have not historically recognized claims based on such assignments, including concerns about interference with the Executive Branch’s Article II powers and prosecutorial discretion. 20 Footnote See Heather Elliott , Congress’s Inability to Solve Standing Problems , 91 B.U. L. Rev. 159 , 195–204 (2011) (questioning whether Congress’s assignment of claims to citizen suitors in order to confer standing would be constitutional or practical).

Module 4: Writing in College

Writing assignments, learning objectives.

- Describe common types and expectations of writing tasks given in a college class

Figure 1 . All college classes require some form of writing. Investing some time in refining your writing skills so that you are a more confident, skilled, and efficient writer will pay dividends in the long run.

What to Do With Writing Assignments

Writing assignments can be as varied as the instructors who assign them. Some assignments are explicit about what exactly you’ll need to do, in what order, and how it will be graded. Others are more open-ended, leaving you to determine the best path toward completing the project. Most fall somewhere in the middle, containing details about some aspects but leaving other assumptions unstated. It’s important to remember that your first resource for getting clarification about an assignment is your instructor—they will be very willing to talk out ideas with you, to be sure you’re prepared at each step to do well with the writing.

Writing in college is usually a response to class materials—an assigned reading, a discussion in class, an experiment in a lab. Generally speaking, these writing tasks can be divided into three broad categories: summary assignments, defined-topic assignments, and undefined-topic assignments.

Link to Learning

Empire State College offers an Assignment Calculator to help you plan ahead for your writing assignment. Just plug in the date you plan to get started and the date it is due, and the calculator will help break it down into manageable chunks.

Summary Assignments

Being asked to summarize a source is a common task in many types of writing. It can also seem like a straightforward task: simply restate, in shorter form, what the source says. A lot of advanced skills are hidden in this seemingly simple assignment, however.

An effective summary does the following:

- reflects your accurate understanding of a source’s thesis or purpose

- differentiates between major and minor ideas in a source

- demonstrates your ability to identify key phrases to quote

- shows your ability to effectively paraphrase most of the source’s ideas

- captures the tone, style, and distinguishing features of a source

- does not reflect your personal opinion about the source

That last point is often the most challenging: we are opinionated creatures, by nature, and it can be very difficult to keep our opinions from creeping into a summary. A summary is meant to be completely neutral.

In college-level writing, assignments that are only summary are rare. That said, many types of writing tasks contain at least some element of summary, from a biology report that explains what happened during a chemical process, to an analysis essay that requires you to explain what several prominent positions about gun control are, as a component of comparing them against one another.

Writing Effective Summaries

Start with a clear identification of the work.

This automatically lets your readers know your intentions and that you’re covering the work of another author.

- In the featured article “Five Kinds of Learning,” the author, Holland Oates, justifies his opinion on the hot topic of learning styles — and adds a few himself.

Summarize the Piece as a Whole

Omit nothing important and strive for overall coherence through appropriate transitions. Write using “summarizing language.” Your reader needs to be reminded that this is not your own work. Use phrases like the article claims, the author suggests, etc.

- Present the material in a neutral fashion. Your opinions, ideas, and interpretations should be left in your brain — don’t put them into your summary. Be conscious of choosing your words. Only include what was in the original work.

- Be concise. This is a summary — it should be much shorter than the original piece. If you’re working on an article, give yourself a target length of 1/4 the original article.

Conclude with a Final Statement

This is not a statement of your own point of view, however; it should reflect the significance of the book or article from the author’s standpoint.

- Without rewriting the article, summarize what the author wanted to get across. Be careful not to evaluate in the conclusion or insert any of your own assumptions or opinions.

Understanding the Assignment and Getting Started

Figure 2 . Many writing assignments will have a specific prompt that sends you first to your textbook, and then to outside resources to gather information.

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt —will explain the purpose of the assignment and the required parameters (length, number and type of sources, referencing style, etc.).

Also, don’t forget to check the rubric, if there is one, to understand how your writing will be assessed. After analyzing the prompt and the rubric, you should have a better sense of what kind of writing you are expected to produce.

Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment! In a situation like that, consider the following tips:

- Focus on the verbs . Look for verbs like compare, explain, justify, reflect , or the all-purpose analyze . You’re not just producing a paper as an artifact; you’re conveying, in written communication, some intellectual work you have done. So the question is, what kind of thinking are you supposed to do to deepen your learning?

- Put the assignment in context . Many professors think in terms of assignment sequences. For example, a social science professor may ask you to write about a controversial issue three times: first, arguing for one side of the debate; second, arguing for another; and finally, from a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective, incorporating text produced in the first two assignments. A sequence like that is designed to help you think through a complex issue. If the assignment isn’t part of a sequence, think about where it falls in the span of the course (early, midterm, or toward the end), and how it relates to readings and other assignments. For example, if you see that a paper comes at the end of a three-week unit on the role of the Internet in organizational behavior, then your professor likely wants you to synthesize that material.

- Try a free-write . A free-write is when you just write, without stopping, for a set period of time. That doesn’t sound very “free”; it actually sounds kind of coerced, right? The “free” part is what you write—it can be whatever comes to mind. Professional writers use free-writing to get started on a challenging (or distasteful) writing task or to overcome writer’s block or a powerful urge to procrastinate. The idea is that if you just make yourself write, you can’t help but produce some kind of useful nugget. Thus, even if the first eight sentences of your free write are all variations on “I don’t understand this” or “I’d really rather be doing something else,” eventually you’ll write something like “I guess the main point of this is…,” and—booyah!—you’re off and running.

- Ask for clarification . Even the most carefully crafted assignments may need some verbal clarification, especially if you’re new to a course or field. Professors generally love questions, so don’t be afraid to ask. Try to convey to your instructor that you want to learn and you’re ready to work, and not just looking for advice on how to get an A.

Defined-Topic Assignments

Many writing tasks will ask you to address a particular topic or a narrow set of topic options. Defined-topic writing assignments are used primarily to identify your familiarity with the subject matter. (Discuss the use of dialect in Their Eyes Were Watching God , for example.)

Remember, even when you’re asked to “show how” or “illustrate,” you’re still being asked to make an argument. You must shape and focus your discussion or analysis so that it supports a claim that you discovered and formulated and that all of your discussion and explanation develops and supports.

Undefined-Topic Assignments