The Lean Post / Articles / How the A3 Came to Be Toyota’s Go-To Management Process for Knowledge Work (intro by John Shook)

Problem Solving

How the A3 Came to Be Toyota’s Go-To Management Process for Knowledge Work (intro by John Shook)

By Isao Yoshino

August 2, 2016

A3 thinking is synonymous with Toyota. Yet many often wonder how exactly this happened. Even if we know A3 thinking was created at Toyota, how did it become so firmly entrenched in the organization’s culture? Retired Toyota leader Mr. Isao Yoshino spearheaded a special program that made A3s Toyota’s foremost means of problem-solving. Read more.

In the late 1970s, Toyota decided to invest in cultivating the managerial capabilities of its mid-level managers. Masao Nemoto, the same influential executive who led Toyota’s successful Deming Prize initiative in 1965, led a development program especially for non-production gemba managers called the “Kanri Nouryoku Program” – “Kan-Pro” for short. Nemoto chose to structure this critical management development initiative around the A3 process .

The A3 is well established now in the lean community. As a process, as a tool, as a way of thinking, managing and developing others. The question often comes up of where did it come from and how did it become a common practice. The basic answer is that it dispersed mainly from Toyota. But how did it become so prevalent in Toyota? And how did it evolve from its humble beginnings as a tool to tell a PDCA quality improvement story on an A3-sized sheet of paper, as it had been commonly used by many Japanese companies since the 1960s?

What had started as a simple tool to tell PDCA stories grew at Toyota into something more: the A3 process came to embody the company’s way of managing in an extraordinarily profound sense. How did this happen?

My first “kacho” (manager) at Toyota (in Japan starting in 1983), Mr. Isao Yoshino, was a member of Nemoto’s four-man team that created and delivered the “Kan-Pro” manager-development initiative that directly answers that question. The program has been unknown outside Toyota … until now.

-John Shook

Interview with Mr. Isao Yoshino

Q: what was the purpose of the kanri nouryoku program.

A: The main purpose was to nurture “Management Capabilities” of employees who were at manager (kacho) level and above. There were four rudimental capabilities for managers:

- Planning capability, judging capability

- Broad knowledge, experiences and perspectives

- Driving force to get job done, leadership, kaizen capability

- Presentation capability, persuasion capability, negotiation capability

Mr. Nemoto decided to take actions in reinvigorate managers (especially administrative) and help heighten awareness of their role. Mr. Isao Yoshino

Q: Why did Toyota decide it needed this program?

A: After introducing Total Quality Control (TQC) in 1961 and receiving the Deming Prize in 1965, TQC-based perspective had taken root widely across the company. In the late ‘70s, Mr. Nemoto (one of the main people behind launching TQC) noticed that management capabilities and TQC awareness was decreasing among managers, particularly within the non-manufacturing gemba or office divisions. Mr. Nemoto decided to take actions to reinvigorate the managers (especially administrative) and help heighten awareness of their role. And so, in 1978, he formed a task force that promoted a two-year program (the Kanri Nouryoku Program) for two thousand managers from all over the company. I was one of the four staff members on the task force in Toyota City.

Q: What sort of tools and activities did the Kanri Nouryoku employ?

A: All the managers went through “a presentation session” twice per year (June and December). The officers in charge of each department attended to have a Question and Answer session with the managers. Officers tried to focus on the problems each manager was facing as well as the effort and process needed to solve the problems. Officers focused more on “What is the major cause of the problem?”, rather than “Who made those mistakes?” This problem-focused attitude (as opposed to the who-made-the-mistake attitude) of the officers encouraged managers to share their problems rather than hide them.

The key to giving the presentations was that they had to be done using an A3. The managers learned how to select what information/data was needed and what was not needed, since an A3 has only limited space. This helped them acquire the seiri and seiton functions of the 5S concept as applied to knowledge work . A3 was also a great tool for officers. They could easily see, at a glance, all the key points that the presenter wanted to convey. As it is just one single document, you can quickly see from the left top corner to the right bottom of an A3 and grasp the key things the writer wants to communicate. This is something that you cannot get from a written document or PowerPoint presentation.

Q: What was your personal experience with the program?

A: First, I was fortunate to get acquainted with many admirable managers, who inspired me in many ways. I also learned how to express myself more effectively by studying A3 documents from two thousand managers. Strikingly, I discovered that managers whose A3s were excellent were also excellent managers at work.

Strikingly, I discovered that managers whose A3s were excellent were also excellent managers at work. Mr. Isao Yoshino

Nemoto-san highly praised managers who took a risk to report their mistakes (not success stories) on A3s with a hope of finding a solution. Nemoto valued their sincere and proactive attitudes. “Nemoto Lectures” were held for managers three or four times a year. Mr. Nemoto went through every single impression memo from the audience as feedback for his next speech.

Mr. Nemoto also appreciated the efforts by managers who tried to nurture excellent subordinates. This created a new company-wide notion that “developing your subordinates is a virtue.” It was amazing to see managers in their 40s and 50s willing to give 100 percent of their energy to work on hoshin kanri and A3 reporting, because they were convinced the program was practical and useful and worth using to bring themselves up to a higher level. Seeing all this happen at work truly helped me grow professionally.

Q: What was the effect of the program on Toyota?

A: Well for one, every mid-level manager who was involved in this program over the two years came to clearly understand their roles and responsibilities and also learned the importance of the hoshin kanri system. People at Toyota don’t hesitate to report bad news, which has been Toyota’s heritage since day one. The Kanri Nouryoku program has further reinforced this tradition because of its praise toward managers and others who were honest about their mistakes. And after the program was implemented to the back-office managers, the level of their awareness of their role rose up to the same level of that of manufacturing-related managers, which significantly strengthened the management foundation.

Everybody became familiar with using the A3 process when documented communication was needed – A3 thinking eventually became an essential part of Toyota’s culture. People learned how to distinguish what is important from what is not.

Managing to Learn

An Introduction to A3 Leadership and Problem-Solving.

Written by:

About Isao Yoshino

Isao Yoshino is a Lecturer at Nagoya Gakuin University of Japan. Prior to joining academia, he spent 40 years at Toyota working in a number of managerial roles in a variety of departments. Most notably, he was one of the main driving forces behind Toyota’s little-known Kanri Nouryoku program, a development activity for knowledge-work managers that would instill the A3 as the go-to problem-solving process at Toyota.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Revolutionizing Logistics: DHL eCommerce’s Journey Applying Lean Thinking to Automation

Podcast by Matthew Savas

Transforming Corporate Culture: Bestbath’s Approach to Scaling Problem-Solving Capability

Building a Problem-Solving Culture: Insights from Barton Malow’s Lean University

Related books

A3 Getting Started Guide

by Lean Enterprise Institute

The Power of Process – A Story of Innovative Lean Process Development

by Eric Ethington and Matt Zayko

Related events

April 16, 2024 | Coach-Led Online Course

Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata

June 10, 2024 | Coach-Led Online Course

Explore topics

Subscribe to get the very best of lean thinking delivered right to your inbox

Privacy overview.

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

Toyota’s Secret: The A3 Report

How Toyota solves problems, creates plans, and gets new things done while developing an organization of thinking problem-solvers.

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- Innovation Strategy

- Quality & Service

- Organizational Behavior

While much has been written about Toyota Motor Corp.’s production system, little has captured the way the company manages people to achieve operational learning. At Toyota, there exists a way to solve problems that generates knowledge and helps people doing the work learn how to learn. Company managers use a tool called the A3 (named after the international paper size on which it fits) as a key tactic in sharing a deeper method of thinking that lies at the heart of Toyota’s sustained success.

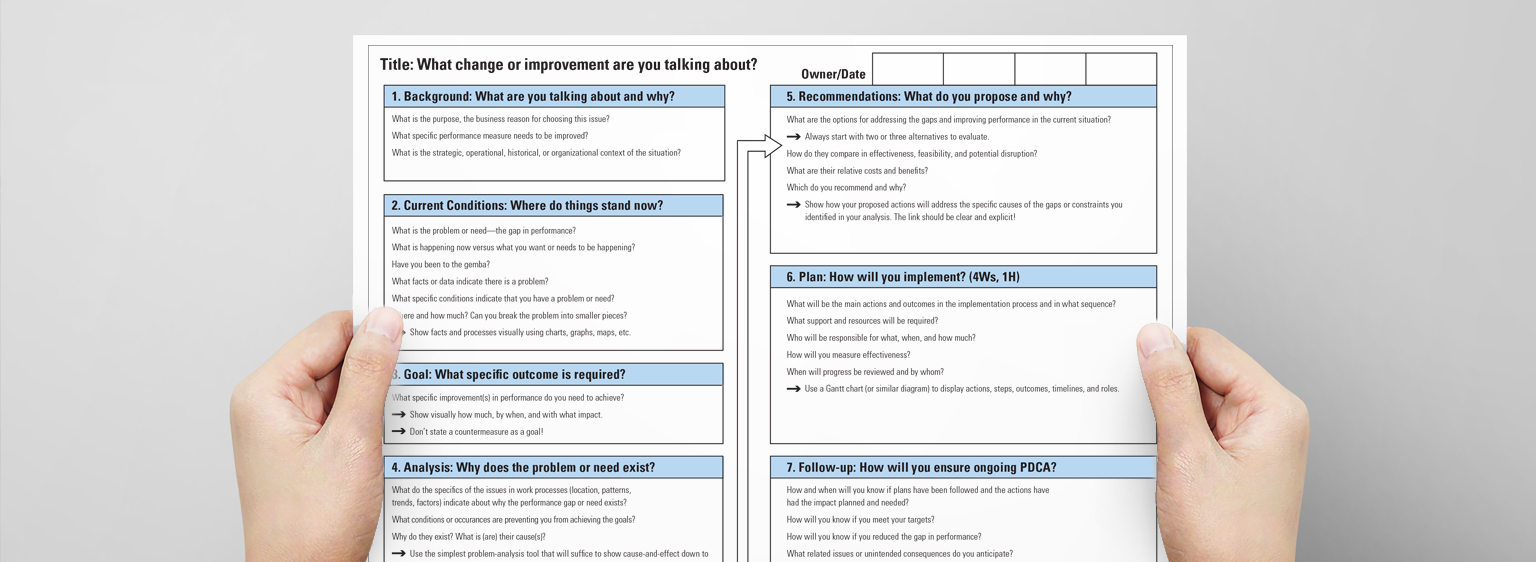

A3s are deceptively simple. An A3 is composed of a sequence of boxes (seven in the example) arrayed in a template. Inside the boxes the A3’s “author” attempts, in the following order, to: (1) establish the business context and importance of a specific problem or issue; (2) describe the current conditions of the problem; (3) identify the desired outcome; (4) analyze the situation to establish causality; (5) propose countermeasures; (6) prescribe an action plan for getting it done; and (7) map out the follow-up process.

The leading question

Toyota has designed a two-page mechanism for attacking problems. What can we learn from it?

- The A3’s constraints (just 2 pages) and its structure (specific categories, ordered in steps, adding up to a “story”) are the keys to the A3’s power.

- Though the A3 process can be used effectively both to solve problems and to plan initiatives, its greatest payoff may be how it fosters learning. It presents ideal opportunities for mentoring.

- It becomes a basis for collaboration.

However, A3 reports — and more importantly the underlying thinking — play more than a purely practical role; they also embody a more critical core strength of a lean company. A3s serve as mechanisms for managers to mentor others in root-cause analysis and scientific thinking, while also aligning the interests of individuals and departments throughout the organization by encouraging productive dialogue and helping people learn from one another. A3 management is a system based on building structured opportunities for people to learn in the manner that comes most naturally to them: through experience, by learning from mistakes and through plan-based trial and error.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

About the Author

John Shook is an industrial anthropologist and senior advisor to the Lean Enterprise Institute, where he works with companies and individuals to help them understand and implement lean production. He is author of Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process to Solve Problems, Gain Agreement, Mentor, and Lead (Lean Enterprise Institute), and coauthor of Learning to See (Lean Enterprise Institute). He worked with Toyota for 10 years, helping it transfer its production, engineering and management systems from Japan to its overseas affiliates and suppliers.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (22)

Sheila colinlak, patrick doyle, acta de constitución de proyecto ágil, un elemento diferenciador. | agilia, dave whaley, william harrod, howard s weinberg, systemental, khucxuanthinh.

MIT Libraries home DSpace@MIT

- DSpace@MIT Home

- MIT Sociotechnical Systems Research Center (SSRC)

- International Motor Vehicle Program

Creating and Managing a High Performance Knowledge-Sharing Network: The Toyota Case

Date issued

Series/report no., collections.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

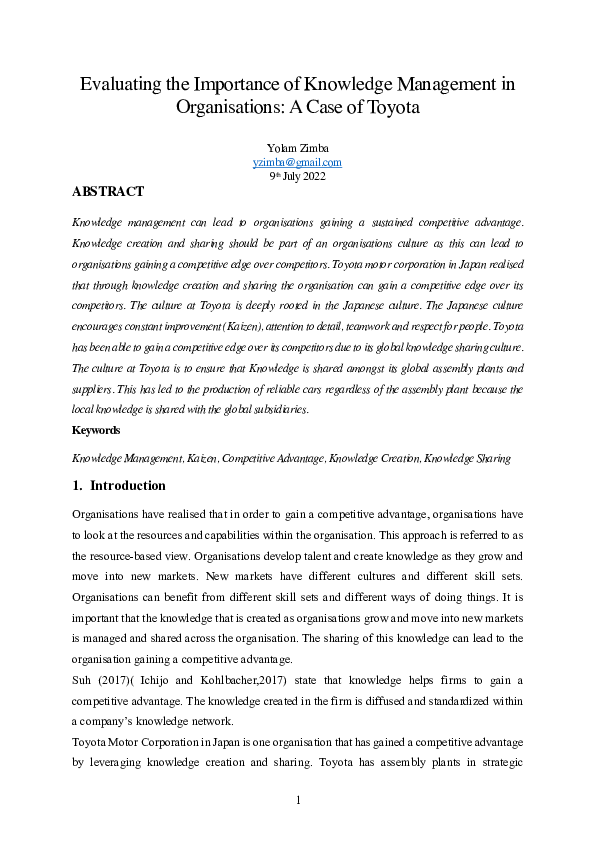

Evaluating the Importance of Knowledge Management in Organisations: A Case of Toyota

2022, Evaluating the Importance of Knowledge Management in Organisations: A Case of Toyota

Knowledge management can lead to organisations gaining a sustained competitive advantage. Knowledge creation and sharing should be part of an organisations culture as this can lead to organisations gaining a competitive edge over competitors. Toyota motor corporation in Japan realised that through knowledge creation and sharing the organisation can gain a competitive edge over its competitors. The culture at Toyota is deeply rooted in the Japanese culture. The Japanese culture encourages constant improvement (Kaizen), attention to detail, teamwork and respect for people. Toyota has been able to gain a competitive edge over its competitors due to its global knowledge sharing culture. The culture at Toyota is to ensure that Knowledge is shared amongst its global assembly plants and suppliers. This has led to the production of reliable cars regardless of the assembly plant because the local knowledge is shared with the global subsidiaries.

Related Papers

Jurnal Kemanusiaan

Che hasniza che Noh

Gerald Guan Gan Goh

International Review

Vida Samiei

Lưu Chí Hồng

Kajian Malaysia

Gerald Guan Gan GOH

Uma Mageswari

Purpose –For several decades the world's best-known forecasters of societal change have predicted the emergence of a new economy in which brainpower, not machine power, is the critical resource. But the future has already turned into the present, and the era of knowledge has arrived.--"The Learning Organization," Economist Intelligence Unit. This new world of business which is characterized by globalization, heightened level of competition, uncertainty about future makes the traditional factors of production land, labour and capital as irrelevant. The only source of sustainable competitive advantage is knowledge and intellectual capital. Hence Knowledge management practices become vital. Research Methodology – An empirical study was conducted by collecting primary data through questionnaire from employees of varied departments of the company. Statistical tools used for analysis in the study are Reliability analysis, factor analysis, correlation and simple research mode...

vijay selvamani

Irena Figurska

The article discusses the importance of appropriate organizational culture for effective knowledge management in the organization functioning in knowledge based economy. Forming such a culture is complicated, long-lasting process, and the success is not guaranteed. What is more, role of the corporate culture for the effectiveness of the organization is very often undervalued by both managers and subordinates. Usually they don’t even possess sufficient knowledge on: what elements constitute and what factors influence organizational culture, how to manage such a culture, what connections are between organizational culture and knowledge management, what features a corporate culture supporting the knowledge management should have, what areas of the corporate culture are of special importance for the effectiveness of the knowledge management, etc. This article is supposed to respond to above specified questions and build awareness of the role of the organizational culture for achieving a...

Mohammed S Msabah

RELATED PAPERS

Dominique Nicaise

Experimental Brain Research

Victor Frak

Thomas Barrios

Mitchell Benson

Papers. Sociología

Salvador Cardus

Georgios Karakonstantis

Mayurqa Revista Del Departament De Ciencies Historiques I Teoria De Les Arts

Emili Garcia Amengual

Vladimir Yefimov

Massimiliano Porreca

Mari Mar Boillos

Centre de recherches Archéologique en Ardenne

British Educational Research Journal

Noella Piquette

Georg Weltin

martin vargas

Bioscience Reports

Carlos Fernández

The biologist

Luis Eduardo Ccama Huaman

Václav Kaczmarczyk

Jiruth Sriratanaban

Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience

Frederic Alexandre

Surface Science

Gianfranco Pacchioni

Younes Benarioua

IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech and Language Processing

Ramani Duraiswami

IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement

Larry Wurtz

Brain Injury

Tammy Smith

Jurnal Pendidikan: Teori, Penelitian, dan Pengembangan

komang astina

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Product details

Teaching and learning

(Still) learning from Toyota

In the two years since I retired as president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN), I’ve had the good fortune to work with many global manufacturers in different industries on challenges related to lean management. Through that exposure, I’ve been struck by how much the Toyota production system has already changed the face of operations and management, and by the energy that companies continue to expend in trying to apply it to their own operations.

Yet I’ve also found that even though companies are currently benefiting from lean, they have largely just scratched the surface, given the benefits they could achieve. What’s more, the goal line itself is moving—and will go on moving—as companies such as Toyota continue to define the cutting edge. Of course, this will come as no surprise for any student of the Toyota production system and should even serve as a challenge. After all, the goal is continuous improvement.

Room to improve

The two pillars of the Toyota way of doing things are kaizen (the philosophy of continuous improvement) and respect and empowerment for people, particularly line workers. Both are absolutely required in order for lean to work. One huge barrier to both goals is complacency. Through my exposure to different manufacturing environments, I’ve been surprised to find that senior managers often feel they’ve been very successful in their efforts to emulate Toyota’s production system—when in fact their progress has been limited.

The reality is that many senior executives—and by extension many organizations—aren’t nearly as self-reflective or objective about evaluating themselves as they should be. A lot of executives have a propensity to talk about the good things they’re doing rather than focus on applying resources to the things that aren’t what they want them to be.

When I recently visited a large manufacturer, for example, I compared notes with a company executive about an evaluation tool it had adapted from Toyota. The tool measures a host of categories (such as safety, quality, cost, and human development) and averages the scores on a scale of zero to five. The executive was describing how his unit scored a five—a perfect score. “Where?” I asked him, surprised. “On what dimension?”

“Overall,” he answered. “Five was the average.”

When he asked me about my experiences at Toyota over the years and the scores its units received, I answered candidly that the best score I’d ever seen was a 3.2—and that was only for a year, before the unit fell back. What happens in Toyota’s culture is that as soon as you start making a lot of progress toward a goal, the goal is changed and the carrot is moved. It’s a deep part of the culture to create new challenges constantly and not to rest when you meet old ones. Only through honest self-reflection can senior executives learn to focus on the things that need improvement, learn how to close the gaps, and get to where they need to be as leaders.

A self-reflective culture is also likely to contribute to what I call a “no excuse” organization, and this is valuable in times of crisis. When Toyota faced serious problems related to the unintended acceleration of some vehicles, for example, we took this as an opportunity to revisit everything we did to ensure quality in the design of vehicles—from engineering and production to the manufacture of parts and so on. Companies that can use crises to their advantage will always excel against self-satisfied organizations that already feel they’re the best at what they do.

A common characteristic of companies struggling to achieve continuous improvement is that they pick and choose the lean tools they want to use, without necessarily understanding how these tools operate as a system. (Whenever I hear executives say “we did kaizen ,” which in fact is an entire philosophy, I know they don’t get it.) For example, the manufacturer I mentioned earlier had recently put in an andon system, to alert management about problems on the line. 1 1. Many executives will have heard of the andon cord, a Toyota innovation now common in many automotive and assembly environments: line workers are empowered to address quality or other problems by stopping production. Featuring plasma-screen monitors at every workstation, the system had required a considerable development and programming effort to implement. To my mind, it represented a knee-buckling amount of investment compared with systems I’d seen at Toyota, where a new tool might rely on sticky notes and signature cards until its merits were proved.

An executive was explaining to me how successful the implementation had been and how well the company was doing with lean. I had been visiting the plant for a week or so. My back was to the monitor out on the shop floor, and the executive was looking toward it, facing me, when I surprised him by quoting a series of figures from the display. When he asked how I’d done so, I pointed out that the tool was broken; the numbers weren’t updating and hadn’t since Monday. This was no secret to the system’s operators and to the frontline workers. The executive probably hadn’t been visiting with them enough to know what was happening and why. Quite possibly, the new system receiving such praise was itself a monument to waste.

Room to reflect

At the end of the day, stories like this underscore the fact that applying lean is a leadership challenge, not just an operational one. A company’s senior executives often become successful as leaders through years spent learning how to contribute inside a particular culture. Indeed, Toyota views this as a career-long process and encourages it by offering executives a diversity of assignments, significant amounts of training, and even additional college education to help prepare them as lean leaders. It’s no surprise, therefore, that should a company bring in an initiative like Toyota’s production system—or any lean initiative requiring the culture to change fundamentally—its leaders may well struggle and even view the change as a threat. This is particularly true of lean because, in many cases, rank-and-file workers know far more about the system from a “toolbox standpoint” than do executives, whose job is to understand how the whole system comes together. This fact can be intimidating to some executives.

Senior executives who are considering lean management (or are already well into a lean transformation and looking for ways to get more from the effort and make it stick) should start by recognizing that they will need to be comfortable giving up control. This is a lesson I’ve learned firsthand. I remember going to CAPTIN as president and CEO of the company and wanting to get off to a strong start. Hoping to figure out how to get everyone engaged and following my initiatives, I told my colleagues what I wanted. Yet after six or eight months, I wasn’t getting where I wanted to go quickly enough. Around that time, a Japanese colleague told me, “Deryl, if you say ‘do this’ everybody will do it because you’re president, whether you say ‘go this way,’ or ‘go that way.’ But you need to figure out how to manage these issues having absolutely no power at all.”

So with that advice in mind, I stepped back and got a core group of good people together from all over the company—a person from production control, a night-shift supervisor, a manager, a couple of engineers, and a person in finance—and challenged them to develop a system. I presented them with the direction but asked them to make it work.

And they did. By the end of the three-year period we’d set as a target, for example, we’d dramatically improved our participation rate in problem-solving activities—going from being one of the worst companies in Toyota Motor North America to being one of the best. The beauty of the effort was that the team went about constructing the program in ways I never would have thought of. For example, one team member (the production-control manager) wanted more participation in a survey to determine where we should spend additional time training. So he created a storyboard highlighting the steps of problem solving and put it on the shop floor with questionnaires that he’d developed. To get people to fill them out, his team offered the respondents a hamburger or a hot dog that was barbecued right there on the shop floor. This move was hugely successful.

Another tip whose value I’ve observed over the years is to find a mentor in the company, someone to whom you can speak candidly. When you’re the president or CEO, it can be kind of lonely, and you won’t have anyone to talk with. I was lucky because Toyota has a robust mentorship system, which pairs retired company executives with active ones. But executives anywhere can find a sounding board—someone who speaks the same corporate language you do and has a similar background. It’s worth the effort to find one.

Finally, if you’re going to lead lean, you need knowledge and passion. I’ve been around leaders who had plenty of one or the other, but you really need both. It’s one thing to create all the energy you need to start a lean initiative and way of working, but quite another to keep it going—and that’s the real trick.

Room to run

Even though I’m retired from Toyota, I’m still engaged with the company. My experiences have given me a unique vantage point to see what Toyota is doing to push the boundaries of lean further still.

For example, about four years ago Toyota began applying lean concepts from its factories beyond the factory floor—taking them into finance, financial services, the dealer networks, production control, logistics, and purchasing. This may seem ironic, given the push so many companies outside the auto industry have made in recent years to drive lean thinking into some of these areas. But that’s very consistent with the deliberate way Toyota always strives to perfect something before it’s expanded, looking to “add as you go” rather than “do it once and stop.”

Of course, Toyota still applies lean thinking to its manufacturing operations as well. Take major model changes, which happen about every four to eight years. They require a huge effort—changing all the stamping dies, all the welding points and locations, the painting process, the assembly process, and so on. Over the past six years or so, Toyota has nearly cut in half the time it takes to do a complete model change.

Similarly, Toyota is innovating on the old concept of a “single-minute exchange of dies” 2 2. Quite honestly, the single-minute exchange of dies aspiration is really just that—a goal. The fastest I ever saw anyone do it during my time at New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) was about 10 to 15 minutes. and applying that thinking to new areas, such as high-pressure injection molding for bumpers or the manufacture of alloy wheels. For instance, if you were making an aluminum-alloy wheel five years ago and needed to change from one die to another, that would require about four or five hours because of the nature of the smelting process. Now, Toyota has adjusted the process so that the changeover time is down to less than an hour.

Finally, Toyota is doing some interesting things to go on pushing the quality of its vehicles. It now conducts surveys at ports, for example, so that its workers can do detailed audits of vehicles as they are funneled in from Canada, the United States, and Japan. This allows the company to get more consistency from plant to plant on everything from the torque applied to lug nuts to the gloss levels of multiple reds so that color standards for paint are met consistently.

The changes extend to dealer networks as well. When customers take delivery of a car, the salesperson is accompanied by a technician who goes through it with the new owner, in a panel-by-panel and option-by-option inspection. They’re looking for actionable information: is an interior surface smudged? Is there a fender or hood gap that doesn’t look quite right? All of this checklist data, fed back through Toyota’s engineering, design, and development group, can be sent on to the specific plant that produced the vehicle, so the plant can quickly compare it with other vehicles produced at the same time.

All of these moves to continue perfecting lean are consistent with the basic Toyota approach I described: try and perfect anything before you expand it. Yet at the same time, the philosophy of continuous improvement tells us that there’s ultimately no such thing as perfection. There’s always another goal to reach for and more lessons to learn.

Deryl Sturdevant, a senior adviser to McKinsey, was president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN) from 2006 to 2011. Prior to that, he held numerous executive positions at Toyota, as well as at the New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) plant (a joint venture between Toyota and General Motors), in Fremont, California.

Explore a career with us

Ask a question from expert

Knowledge Management: Preparing Case Study for Toyota, Japan

Added on 2023-05-29

About This Document

This article presents a case study on the knowledge management practices at Toyota, Japan. It discusses the importance of absorptive capacity, individual theories of learning and their psychological perspectives in enhancing organizational culture and productivity. The article also highlights the role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation.

Motivational Theory Case lg ...

Impact of leadership and organizational learning on company profitability: a case study on m&s lg ..., different learning styles for john lewis partnership's staff member lg ..., employability skills assignment tesco lg ..., leadership and management development | assignment lg ....

We apologize for the inconvenience...

To ensure we keep this website safe, please can you confirm you are a human by ticking the box below.

If you are unable to complete the above request please contact us using the below link, providing a screenshot of your experience.

https://ioppublishing.org/contacts/

Committed to connecting the world

- Media Centre

- Publications

- Areas of Action

- Regional Presence

- General Secretariat

- Radiocommunication

- Standardization

- Development

- Members' Zone

ITU: Committed to connecting the world

Share your digital innovation story

World Telecommunication and Information Society Day 2024 celebrates the power of digital innovation in advancing sustainable development and prosperity for all.

Share your story or event by 17 April.

International Girls in ICT Day

Girls in ICT Day focuses on supporting women leaders in science, engineering, technology and mathematics – join the celebrations on 25 April.

Learn more and register

Final Acts from WRC-23

ITU’s recent World Radiocommunication Conference achieved key regulatory decisions on spectrum use for space, science, and terrestrial radio services. Download the Final Acts

Global E-Waste Monitor

Electronic waste is increasing five times faster than the documented amounts being recycled, according to the UN latest report. Read more

Machine translation by ITU Translate. See full disclaimer . Provide feedback .

News and views

Digital-related emissions data in demand

Satellites watching over our planet

From small islands to Smart Islands

In depth

Facts and Figures 2023

Connectivity in Small Island Developing States

Outcomes of the World Radiocommunication Conference

PARTNER2CONNECT

A.I. FOR GOOD

KALEIDOSCOPE 2024

- Who we are

- Our regional presence

- ITU Strategic Plan

- Connect 2030 Agenda

- ITU Activities 2022-2023 and the full report PDF version

- World Telecommunication & Information Society Day

- Gender equality

- History of ITU

- ITU Headquarters: New Building Project

- Procurement

- Ethics Office

- ITU Plenipotentiary Conference

- ITU Council

- Basic Texts of the Union

- ITU Information/Document Access Policy

- Regional Telecommunication Organizations

- Conferences

© ITU All Rights Reserved

- Privacy notice

- Accessibility

- Report misconduct

COMMENTS

Strategic Management Journal Strat. Mgmt. J., 21: 345-367 (2000) CREATING AND MANAGING A HIGH-PERFORMANCE KNOWLEDGE-SHARING NETWORK: THE TOYOTA CASE JEFFREY H. DYER1* and KENTARO NOBEOKA2 'Marriott School of Management, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, U.S.A. 2Research Institute for Economics and Business Administration, Kobe University ...

1. Knowledg e Network of T oy ota: Creation, Diffusion, and. Standardization of Knowledge. Yo u n g k yo S UHa) Abstract: Knowledge is a source of firm's competitiveness and i s. created ...

In the late 1970s, Toyota decided to invest in cultivating the managerial capabilities of its mid-level managers. Masao Nemoto, the same influential executive who led Toyota's successful Deming Prize initiative in 1965, led a development program especially for non-production gemba managers called the "Kanri Nouryoku Program" - "Kan-Pro" for short.

Abstract. This paper presents insights from two case studies of Toyota Motor Corporation and its way of strategic global knowledge creation. We will show how Toyota's knowledge creation has moved ...

An A3 is composed of a sequence of boxes (seven in the example) arrayed in a template. Inside the boxes the A3's "author" attempts, in the following order, to: (1) establish the business context and importance of a specific problem or issue; (2) describe the current conditions of the problem; (3) identify the desired outcome; (4) analyze ...

This study offers a detailed case study of how Toyota facilitates interorganizational knowledge transfers among within its production network. In particular, we identiify and examine six key ...

CREATING AND MANAGING A HIGH PERFORMANCE KNOWLEDGE-SHARING NETWORK: THE TOYOTA CASE Jeffrey H. Dyer Stanley Goldstein Term Assistant Professor of Management Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania 2000 Steinberg-Dietrich Hall Philadelphia, PA 19104-6370 (215) 898-9371 [email protected]. edu Kentaro Nobeoka Associate Professor of Management ...

The case discusses the various Knowledge Management (KM) practices at Toyota Motors, the world's most profitable automobile company. It also describes how Toyota enables wide knowledge sharing not just within the organization but also across its supply chain. It details the practices that make Toyota a true learning organization. It further explores the role of traditional organizational ...

Knowledge network of Toyota 93 Management Consulting Division (O MCD), and the Global Production Center (GPC) as nodes on Toyota's domestic knowledge network. ... Through two case studies, this section explains knowledge diffusion within Toyota's knowledge network. Case 1: The yamazumi table is a tool developed to allocate

At Toyota, knowledge sharing was intertwined with its people-based enterprise culture, referred to as the Toyota Way. The five key principles that summed up the Toyota Way were: Challenge 10 , Kaizen (improvement), Genchi Genbutsu (go and see), Respect and Teamwork. The Toyota Way recognized employees as the company's strength and attached ...

This study offers a detailed case study of how Toyota facilitates interorganizational knowledge transfers among within its production network. In particular, we identiify and examine six key institutionalized knowledge sharing routines developed by Toyota and its suppliers. By examining how Toyota facilitates knowledge-sharing with, and among ...

The case discusses the various Knowledge Management (KM) practices at Toyota Motors, the world's most profitable automobile company. It also describes how Toyota enables wide knowledge sharing not just within the organization but also across its supply chain. It details the practices that make Toyota a true learning organization. It further explores the role of traditional organizational ...

The Role of Culture in Knowledge Management: A Case Study of Two Global Firms. Lưu Chí Hồng. Download Free PDF ... The Toyota way views mistakes as learning points for the employees. (Zarate, 2007). The Toyota approach to knowledge management is what has led to its success and this has made the organisation gain a sustained competitive ...

This is a Japanese version. The case discusses the various knowledge management (KM) practices at Toyota Motors, the world's most profitable automobile company. It also describes how Toyota enables wide knowledge sharing not just within the organisation but also across its supply chain. It details the practices that make Toyota a true learning ...

There's always another goal to reach for and more lessons to learn. Deryl Sturdevant, a senior adviser to McKinsey, was president and CEO of Canadian Autoparts Toyota (CAPTIN) from 2006 to 2011. Prior to that, he held numerous executive positions at Toyota, as well as at the New United Motor Manufacturing (NUMMI) plant (a joint venture ...

This article looks at the inter-linkages and causalities between innovation and knowledge management in terms of sustainable development goals through the case study method. Taking the case of the Toyota Prius, these concepts are further developed in detail.

From knowledge to competitive advantage: The Toyota knowledge network case study. December 2010. DOI: 10.1109/ICISE.2010.5690476. Authors: Tang Chenglin. Gu Xin. To read the full-text of this ...

This article presents a case study on the knowledge management practices at Toyota, Japan. It discusses the importance of absorptive capacity, individual theories of learning and their psychological perspectives in enhancing organizational culture and productivity. The article also highlights the role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation.

This article looks at the inter-linkages and causalities between innovation and knowledge management in terms of sustainable development goals through the case study method. Taking the case of the Toyota Prius, these concepts are further developed in detail.

A new ITU case study offers an evaluation of Moscow's progress in meeting the objectives of its 'smart city' strategies and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The case study , Implementing ITU-T International Standards to Shape Smart Sustainable Cities: The Case of Moscow, was undertaken using the Key Performance ...

The Project Management Institute (PMI) creates a project management body of knowledge (PMBOK) [1], which contains basic schemes, principles, methods, practices and a glossary. The "theoretical standard" of project management, and which provides the basis for professional activities under the project management.

Proc. Russian Conference on Digital Economy and Knowledge Management, Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research (2020), 10.2991/aebmr.k ... No. 9003 in the Philippines on MSW management: a case study of cebu city. Waste Manag., 34 (2014), pp. 971-979, 10.1016/j.wasman.2013.10.040. View PDF View article View in Scopus Google ...

Similarly, in the case of forests in Indonesia, climate change can influence local knowledge of forest management. Consequently, there is a need for studies on how communities adapt their traditional practices to climate change and the impact of such adaptations on the sustainability of forest resources.

Objectives. The estimation of the current status of Moscow as a Smart City. The identification of current weaknesses in Moscow's smart strategy for the benefit of future planning. The identification of new directions for Smart City development based on expert opinions. Determining the most efficient way to share best practices in the Smart ...