Conclusion: Peace Processes, Past, Present, and Future

- First Online: 12 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Anthony Wanis-St. John 3 &

- Roger Mac Ginty 4

1091 Accesses

Around 40 peace processes were underway in the year 2020, and there were hundreds of such processes underway in the past two decades. While many resulted in agreements, some of these were minor, temporary, and highly localized. A good number of these peace agreements were comprehensive, landmark accords that brought significant national and regional change.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of International Service, American University School of International Service, Washington, DC, USA

Anthony Wanis-St. John

Durham University, Durham, UK

Roger Mac Ginty

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Roger Mac Ginty .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of International Service, American University, Washington, DC, DC, USA

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Wanis-St. John, A., Mac Ginty, R. (2022). Conclusion: Peace Processes, Past, Present, and Future. In: Mac Ginty, R., Wanis-St. John, A. (eds) Contemporary Peacemaking. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82962-9_27

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82962-9_27

Published : 12 January 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-82961-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-82962-9

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Arts & Culture

Get Involved

Autumn 2023

Annual Gala Dinner

Internships

Why the Afghan peace process failed, and what could come next?

Aref Dostyar , Zmarai Farahi

After nearly two decades of U.S. presence, the Afghan conflict between the central government and the Taliban reached a deadly stalemate, taking a hundred lives a day from each side between 2018 and 2021. However sad, the international community viewed this impasse as a sign of Afghanistan’s ripeness for peace. Meanwhile, the U.S. shifted its policy from pursuing a military victory to achieving an expeditious political settlement. Yet despite multifaceted and multiparty motivations to finally end this drawn-out conflict, the peace process still failed. Why?

This article’s authors observed the peace process closely from within the Afghan government. The following identifies four interconnected factors that converged to spoil the final attempt to end the long war in Afghanistan, resulting in the Taliban unilaterally taking control of Kabul in August 2021. Additionally, the piece offers three sets of recommendations to the United States and the international community about how the lessons of the past 20 years could inform a workable peace process going forward.

Failure in shaping narratives

Aside from armed struggles over physical territory, the Afghan War was also fought on a parallel battleground: the minds of the people.

Afghanistan’s U.S.-backed government, which existed between December 2001 and August 2021, had the burden to prove two narratives: its ability to provide basic services — physical security at a minimum — to the local population and a capability to advance counterterrorism efforts both at home and beyond the country’s borders.

But the Taliban’s car bombs and suicide brigades continued to speak louder than the government’s infographics proclaiming the competence of its institutions. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan described civilian casualties in May-June 2021 — on the eve of the United States’ announced withdrawal date — as the highest on record for those two months since the mission began recording such data in 2009.

The government itself, seeking sustained global support in the fight against terrorism, reported during every major international meeting that more than 20 terrorist organizations with regional and international reach enjoyed safe havens in Afghanistan under the patronage of the Taliban.

The Taliban, by contrast, defined their existence in terms of the enemy, America, which occupied Afghanistan and established a “puppet” government in Kabul. Over the 20 years of war, the Taliban used sustained offensive attacks and some short-term ceasefires to promote themselves as a cohesive military force. And foreigners interpreted that characterization to mean that if the Taliban committed to something like crushing internationally designated terrorist groups, the Taliban could deliver on it. Whether they actually would remained to be seen.

No narrative promulgated by the last Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, who garnered less than a million votes in a contested election in September 2019, could change a simple reality: the war against the Taliban was widely perceived as lost.

Failure in leadership for peace

During the last decade of America’s presence in Afghanistan, the international community and the local government came to an understanding that the way to end the conflict was through peace negotiations with the Taliban. However, the stakeholders in these talks had conflicting interests.

For Afghan technocrats, peace initially meant a full Taliban surrender. The highest leadership bodies of the government held internal discussions regarding the “reintegration” of the Taliban fighters. During these meetings, the officials offered four types of incentives:

- Security in return for disarmament;

- Political space to run for office or be appointed to political posts;

- Economic incentives to provide jobs; and

- Legal incentives to remove the Taliban from international sanctions lists and release their prisoners.

For former mujahideen factions, peace meant a division of power among influential parties. But this process of power-sharing, which would inevitably break down along ethnic lines, would leave no room for the technocrats who now held the presidency. The share of power for Afghanistan’s ethnic Tajiks would go to the Jamiat party; that for the Pashtuns would be given to the Taliban and Hizb-e-Islami; the Wahdat party would claim the Hazaras; and the Junbish party would represent the Uzbeks. Where would the technocrats fit?

Some individuals in the technocrat and mujahideen camps accepted that one way to achieve peace was to hold elections with the participation of the Taliban. However, there were disagreements around the timing of these elections, not to mention the Taliban’s total disinterest in sharing in what they believed to be an illegitimate political system imposed by the United States. President Ghani, in turn, demanded that the transfer of power be based on votes alone, but he showed willingness to hold early elections for the sake of peace. Potential rival candidates argued that no credible election could take place under a party to the conflict. These candidates pushed President Ghani to step aside and let an interim government oversee the elections, which he refused.

In the internal debates regarding peace, three important segments of Afghan society remained outside the process. Youth, women, and civil society organizations, including the media in Afghanistan, did not know what benefits peace would bring them. Apart from symbolic representation in some meetings that were held by the government or the international community, these groups did not meaningfully participate in the wider peace process.

Disagreements over how non-Taliban groups could negotiate with the Taliban were also not resolved. Ghani wanted a two-sided table — the government and the Taliban — in order to portray a united Islamic Republic. But others viewed this format as an unacceptable opportunity for government technocrats to assume leadership roles in the peace negotiations. Therefore, political opponents of the president advocated for multi-party talks in which each side could bargain based on its own interests: the government, the Taliban, political parties, and civil society.

The lack of a shared vision or clear objectives for the peace process among non-Taliban factions ultimately was another factor that contributed to the inability to achieve a settlement.

Parallel structures

In addition to leadership challenges, technical chaos prevailed over the political peace process. The High Peace Council, which later transformed into the High Council of National Reconciliation under Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, was in constant rivalry with the Afghan president and never achieved the power needed to represent the political arm of the peace process. The State Ministry of Peace attempted but failed to project itself as the technical arm of the peace talks. Others rightly viewed “technical matters” as a strategic tool to influence the process.

There were also other governmental agencies that claimed leadership, which instead only added ambiguity to the process. Chief among these agencies was the Office of the National Security Council (ONSC), which maintained a Directorate of Peace and Reconciliation Affairs. Furthermore, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs struggled to preserve its perceived status as the point of contact on peace affairs for foreign countries. Disjointed involvement from too many people and institutions in the peace process meant local Afghans and foreign diplomats had difficulty coordinating their activities with the government.

To make matters worse, rivalries, incompetence, and ideological differences led to the formation of factions within the Afghan state’s negotiations team. When the president was finally able to create a government-led team, it was divided. A former head of the intelligence agency, Masoom Stanikzai, was the lead negotiator. But the Islamist Taliban disregarded Stanikzai because of his former affiliation with parties that were known for their adherence to communist ideologies. Via the Chinese and Uzbekistani governments, the Taliban asked the central government in Kabul to keep Stanikzai out of the peace negotiations. The government responded that the Taliban did not have veto power. Parallel to the official negotiations team, a secret channel of communication between the government and the Taliban opened in Doha, according to Fawzia Koofi, one of the negotiators .

The process was further complicated by foreign interventions. In December 2018, after a year-long effort, high-level representatives from Afghanistan, the United States, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia succeeded in bringing the Afghan government and Taliban negotiators to Abu Dhabi. Even though the two Afghan sides did not meet face-to-face during that time, this quadrilateral effort saw some progress until the Americans shifted the venue to Qatar.

Two years later, there was a new team of negotiators from Kabul and a new process was underway in Doha. At this moment, the U.S. administration changed and the newly appointed Secretary of State Antony Blinken asked the sides, via a letter , to appear for peace talks in Turkey. A meeting in Istanbul never materialized, perhaps because the Qataris, with significant influence over the Taliban, opposed it. Each change of plan meant more stakeholders offended, a reshuffling of negotiating teams to adjust their levels of participation, new logistical complexities, discontinuity, and, eventually, failure.

Peace negotiations never took place directly between the Afghan government and the Taliban. Composed of a few members, a governmental contact group repeatedly met with the Taliban in Qatar; but this was the extent of the face-to-face interaction between the two sides. They worked out the principles for the talks but never succeeded in developing an agenda, let alone negotiated over it.

Reducing peace to one element of a foreign deal

The role of the United States was equally important in forestalling peace.

For many years, the overriding stated purpose of the U.S. presence in Afghanistan was to counter terrorism. And so, under the influence of this policy, the Afghan government continuously presented its peace plans as a counterterrorism strategy.

Over time, America’s assessment of the nature of the threat changed, with major terrorist hotspots appearing in other areas of the world. So, America shifted its sights toward withdrawal from Afghanistan, prioritizing the end of its protracted involvement in the region. The agreement U.S. officials signed with the Taliban in 2020 demanded security guarantees for the pull back of U.S. troops and the Taliban’s commitment to counterterrorist actions; but it encouraged the mere start of peace talks among Afghans and only included a ceasefire as a topic for discussion in subsequent intra-Afghan negotiations.

Once the U.S. was determined to depart and the collapse of the Afghan government became conceivable, negotiations with the Taliban were deemed more important than negotiating with the Afghan government. Diplomats and military generals from the U.S., Europe, and regional countries queued up to talk with the Taliban. The insurgent group viewed this string of international visitors as proof of the effectiveness of their violent movement. Now that the whole world was at their door and the United Nations had endorsed the deal they signed with Washington, they sensed it was only a matter of time before they would seize Kabul.

The Taliban, thus, encouraged the U.S. side to pressure the Afghan government into giving in without preconditions. Most notably, under foreign insistence, the Afghan authorities released more than 5,000 dangerous Taliban detainees in 2020, in return for one-fifth that number of their own prisoners. Against their pledge, these violent extremists returned to the battlefield with greater resolve for vengeance, while the Taliban leadership rewarded their time spent behind bars by appointing them as field commanders.

Conclusion and recommendations

The last political peace process failed, but the need for peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan did not disappear. In fact, conditions likely to drive armed conflict — such as political exclusion and social oppression — are growing daily under the new regime. Therefore, Afghanistan requires a new political process that aims to not only prevent another civil war but also achieve lasting peace. Afghan leaders need to develop the capability to rally the public and align all Afghan sides of the conflict around a common vision for the future of the country.

The international community, particularly the United States, should undertake three specific sets of actions to foster the conditions for such a political process:

First, the U.S. should change its pragmatic engagement with the Taliban to a more inclusive engagement with all Afghan stakeholders , including civil society organizations, political parties, armed opposition groups, ethnic and religious minorities, women, and youth. While the U.S. has no diplomatic presence in Kabul, American officials can engage Afghan actors in the region around Afghanistan as well as communicate with those inside Afghanistan virtually, through video conference calls. Finally, Washington could better coordinate its efforts with the U.N. Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, which has a political office that is active on the ground.

Engagement with non-Taliban actors will have a range of repercussions. For leaders who remain inside Afghanistan, contact with the U.S. will come with security risks. Their identities should be protected; but ultimately, they must be allowed to determine for themselves whether the risks are worthwhile. U.S. interactions with the armed opposition to the Taliban can take place without providing material support to such factions. Engaging with America can still benefit armed groups as a means of exerting political pressure on the Taliban. If the U.S. administration shies away from such a policy, Congress should fill this gap.

In fact, Capitol Hill lawmakers ought to play a more active role regardless of the presidential administration’s stance vis-à-vis Afghanistan. American senators and House members should intensify their meetings with Afghans in the U.S. as well as travel to Europe and the region around Afghanistan to meet with leaders in exile. These meetings would broadcast a confident message that America stands with the people of Afghanistan in their struggle to create a peaceful and free country.

Second, the U.S. should use its leverage with the Taliban more strategically to encourage the start of a political process. For instance, the U.S. should work with the U.N. Security Council to turn international sanctions into effective tools of diplomacy rather than use them solely as punishment. Currently, neither imposed sanctions nor limited waivers are tied to specific political or accountability benchmarks and objectives. The unfreezing of Afghanistan’s assets and discussions about recognizing a new government should become conditional on progress in a legitimate political process.

Conditions and benchmarks for launching such a political process may include initiating a series of meetings between Afghan actors and the Taliban, developing a list of popular demands — from opening girls’ schools and reversing restrictive measures against women to creating a broad-based and people-centric government — and finally, delivering on these demands within agreed timeframes.

Identifying stakeholders to meet with the Taliban is complicated but not impossible. One way to group different segments of Afghan society is based on their ideological visions for the country: modernists who constitute much of the new generation of Afghan leaders, conservatives like the jihadist groups, fundamentalists such as the Taliban and their sympathizers, and moderates who have separated from or never joined the other three groups. Representation of all these ideological differences is important because not all civil society organizations, political parties, or women’s groups think alike.

Finally, Washington must revise its approach toward Afghanistan in light of the fact that al-Qaeda’s leader Ayman al-Zawahiri — who last month was eliminated by a U.S. drone strike — was found to have been sheltered in Kabul . America should, thus, take certain diplomatic steps to mobilize the region and the wider international community to ensure a political process leads to a government that does not harbor terrorists but promotes peace and stability in the world.

Al-Zawahiri’s presence only a few miles from Kabul’s Presidential Palace demonstrated that a Taliban-dominated Afghanistan can be dangerous for the region and beyond. A high-level visit from the U.S. administration or Congress to Central or South Asia in the near-term could potentially ignite momentum among regional countries to mobilize and diplomatically curb future threats that emanate from Afghanistan. The only sustainable means to achieve such an objective is to encourage the formation of a broad-based and people-centric government that is shaped by all Afghans through an inclusive political process. The fact that the Taliban continue to operate as a de facto “acting” government and have yet to announce a new constitution provides a window of opportunity for initiating such a political process.

These short- to medium-term measures by America are achievable. They could exert some pressure on the Taliban and reassure non-Taliban groups that they are not alone in their struggle. They could also mobilize the region to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a regime-run safehouse for terrorists with objectives reaching far beyond its borders. Lastly, these steps, if sustained long enough to jumpstart a potential political process and see it through to completion, could contribute to the restoration of America’s reputation after its catastrophic withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Aref Dostyar is a Senior Advisor for the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc-Pulte Afghanistan Peace and Development Research Program, and former Consul General of Afghanistan in Los Angeles. He tweets from @ArefDostyar.

Zmarai Farahi is former Head of the Peace Unit at the Office of the National Security Council of Afghanistan. He tweets from @FarahiZmarai. The views expressed in this piece are their own.

Photo by KARIM JAAFAR/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click her e .

More results...

PeaceRep : Peace and Conflict Resolution Centre

Rethinking peace & transition processes in a changing conflict landscape

Seminars, discussions and more from PeaceRep consortium members.

Key Findings: Peace Processes

Read our key findings on peace processes

Peace processes are structured attempts to resolve radical disagreement between conflict parties. PeaceRep examines how peace processes are designed and how they attempt to rework political settlements to form both an elite bargain capable of ending fighting, and an inclusive social contract between a government and the population. This research focuses on how conflict parties and mediators navigate the inclusion of people and agendas of change in peace processes. Central to this work are the PA-X Peace Agreement Database and the support the programme provides to peacemakers, particularly through its partner Conciliation Resources (see impact for examples).

Peace Processes (overview)

- Publications

Peace negotiations are one of the most common ways of ending conflict. Over 1800 formalised peace agreements in over 150 different peace processes have been signed between 1990 and mid-2020. These agreements have different goals, including establishing ceasefires, bringing conflict parties to the negotiation table, resolving substantive disagreement over power-sharing, or implementing previous agreements ( PA-X Peace Agreement Database ; Bell & Badanjak 2019 ).

Most peace agreements signed since 1990 deal with armed conflict within states ( PA-X Peace Agreement Database ). Only about 17% of peace agreements deal with interstate conflict. However, given the internationalised nature of many conflicts, resolution of internal conflict often requires international agreements to underpin it. Agreements between states can play an important role in ending outside support to conflict parties within a neighboring state. These agreements also offer opportunities to strengthen the role of international normative frameworks in peace processes, for example by emphasizing human rights norms ( Nash 2019 ).

Only just under 20% of peace agreements signed since 1990 (371 out of 1868 agreements) have provisions on women, gender or sexual violence. Many of these peace agreement references are single line and tokenistic, and only a few include a more holistic gender perspective throughout (see PSRP key findings on ‘gender’ for more analysis).

Peace processes are non-linear and messy. Often talks are started, break down, and restart. Multiple sequenced small steps tend to be the norm rather than one giant stride towards ending armed conflict (as visualized by the ‘ messy timeline ’). Peace processes normally include several rounds of talks, with sometimes at least 3 – but often more – ceasefires and revisions of earlier agreements between opposing factions. There were 39 ceasefires during the Bosnia conflict 1992-1995, alone.

Even comprehensive peace deals can unravel. There have been at least 15 cases since the Cold War that had to be signed and revisited when fighting re-ignited. These include Bosnia, Burundi, DRC, India, Somalia and Sudan ( PSRP infographic 2019 ).

Recent national-level peace processes have often ‘locked in’ disagreement rather than resolving it. Sometimes the need to compromise pushes conflict parties to agree on superficial or institutional reforms without tackling the root causes of a conflict. Power struggles are then carried forward into the new institutions, creating a form of ‘formalised political unsettlement’ in which conflict parties continue bargaining ( Bell & Pospisil 2017 ; Pospisil 2019 ).

Inclusion makes peace more durable. There is evidence suggesting that the involvement of civil society groups, such as women’s groups, in peace processes correlates with more enduring peace ( Nilsson 2012 ). Our research indicates that while framework peace negotiations focused on ‘comprehensive agreement’ often do have input from a wide range of actors even if they are not at the negotiating table, early stage agreements, such as ceasefires negotiated between armed actors alone, have often set the pathways for change. Similarly, implementation negotiations often narrow to armed actors. Focusing on inclusion at all stages of a peace process is important to any social contract that can help sustain the commitment to peace across peace agreement implementation ‘bumps’.

Local peace processes hold both opportunities and risks for wider peacemaking. Local peace agreements serve a variety of purposes, including halting violence, building momentum for national-level peacemaking, or enabling humanitarian access ( Pospisil, Wise and Bell 2020 ; Wise, Beaujouan, Epple and Wilson 2020 ). These agreements can reduce violence on the ground, build trust between conflict parties, and resolve disagreements that undermine national-level peace processes. However, local peace processes risk fracturing armed groups, potentially creating new forms of local autonomy and conflict ( Wise, Forster and Bell 2019 ).

The diversity of actors involved and the presence of potential spoilers often complicate peace agreement implementation. Continued mediation and third-party monitoring bodies can play a useful role in resolving disputes and overseeing implementation. While measuring peace and progress in implementation is inherently political and difficult, setting clear timelines and benchmarks may improve chances of successful implementation ( Molloy 2018 ).

Peace Process Publications

On the Law of Peace: Peace Agreements and the Lex Pacificatoria

This book provides a comprehensive analysis of the use of peace agreements from a legal perspective. It describes and evaluates the development of contemporary peace processes and the peace agreements that emerge. At its heart, the book grapples with the role of law in ending violent conflict and the broader questions this raises for the relationship of law to social change.

Infographic: Peace Processes

This infographic illustrates key themes from our research into 30 years of peace processes around the world. Available as an interactive infographic and static PDF.

Navigating Inclusion in Peace Settlements: Human Rights and the Creation of the common Good

In this report the authors argue that peace settlements often produce compromises between parties at the heart of conflict, which are difficult to deepen into broader political commitments to govern for all in the interest of ‘the common good’.

Peace in Political Unsettlement: Beyond Solving Conflict

This book maps a new understanding of peace processes as institutionalising formalised political unsettlement and points out new ways of engaging with it. The book points to the ways in which peace processes institutionalise forms of disagreement, creating ongoing processes to manage it, rather than resolve it.

Interstate Agreements to End Intrastate Conflicts

This PA-X report examines interstate agreements that have been used to resolve internal conflict using a global dataset (PA-X Peace Agreement Database).

Peace process protagonism: the role of regional organisations in Africa in conflict management. Global Change, Peace & Security

This article seeks to illuminate the changing landscape of regional security governance in Africa, primarily through the lens of formal peace agreements, which are important tools for ending violent conflict.

Untangling Conflict: Local Peace Agreements in Contemporary Armed Violence

This research draws on discussions held at two Joint Analysis Workshops in October and November 2019, in cooperation with The British Academy (BA) and the Rift Valley Institute (RVI). In total, over 100 participants from 25 countries involved with or researching on local peace agreements contributed to thematic discussions.

Introducing PA-X: a new peace agreement database and dataset

This article introduces PA-X, a peace agreement database designed to improve understanding of negotiated pathways out of conflict. PA-X enables scholars, mediators, conflict parties and civil society actors to systematically compare how peace and transition processes formalize negotiated commitments in an attempt to move towards peace.

December 2, 2021

Peace Is More Than War’s Absence, and New Research Explains How to Build It

A new project measures ways to promote positive social relations among groups

By Peter T. Coleman , Allegra Chen-Carrel & Vincent Hans Michael Stueber

PeopleImages/Getty Images

Today, the misery of war is all too striking in places such as Syria, Yemen, Tigray, Myanmar and Ukraine. It can come as a surprise to learn that there are scores of sustainably peaceful societies around the world, ranging from indigenous people in the Xingu River Basin in Brazil to countries in the European Union. Learning from these societies, and identifying key drivers of harmony, is a vital process that can help promote world peace.

Unfortunately, our current ability to find these peaceful mechanisms is woefully inadequate. The Global Peace Index (GPI) and its complement the Positive Peace Index (PPI) rank 163 nations annually and are currently the leading measures of peacefulness. The GPI, launched in 2007 by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), was designed to measure negative peace , or the absence of violence, destructive conflict, and war. But peace is more than not fighting. The PPI, launched in 2009, was supposed to recognize this and track positive peace , or the promotion of peacefulness through positive interactions like civility, cooperation and care.

Yet the PPI still has many serious drawbacks. To begin with, it continues to emphasize negative peace, despite its name. The components of the PPI were selected and are weighted based on existing national indicators that showed the “strongest correlation with the GPI,” suggesting they are in effect mostly an extension of the GPI. For example, the PPI currently includes measures of factors such as group grievances, dissemination of false information, hostility to foreigners, and bribes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The index also lacks an empirical understanding of positive peace. The PPI report claims that it focuses on “positive aspects that create the conditions for a society to flourish.” However, there is little indication of how these aspects were derived (other than their relationships with the GPI). For example, access to the internet is currently a heavily weighted indicator in the PPI. But peace existed long before the internet, so is the number of people who can go online really a valid measure of harmony?

The PPI has a strong probusiness bias, too. Its 2021 report posits that positive peace “is a cross-cutting facilitator of progress, making it easier for businesses to sell.” A prior analysis of the PPI found that almost half the indicators were directly related to the idea of a “Peace Industry,” with less of a focus on factors found to be central to positive peace such as gender inclusiveness, equity and harmony between identity groups.

A big problem is that the index is limited to a top-down, national-level approach. The PPI’s reliance on national-level metrics masks critical differences in community-level peacefulness within nations, and these provide a much more nuanced picture of societal peace . Aggregating peace data at the national level, such as focusing on overall levels of inequality rather than on disparities along specific group divides, can hide negative repercussions of the status quo for minority communities.

To fix these deficiencies, we and our colleagues have been developing an alternative approach under the umbrella of the Sustaining Peace Project . Our effort has various components , and these can provide a way to solve the problems in the current indices. Here are some of the elements:

Evidence-based factors that measure positive and negative peace. The peace project began with a comprehensive review of the empirical studies on peaceful societies, which resulted in identifying 72 variables associated with sustaining peace. Next, we conducted an analysis of ethnographic and case study data comparing “peace systems,” or clusters of societies that maintain peace with one another, with nonpeace systems. This allowed us to identify and measure a set of eight core drivers of peace. These include the prevalence of an overarching social identity among neighboring groups and societies; their interconnections such as through trade or intermarriage; the degree to which they are interdependent upon one another in terms of ecological, economic or security concerns; the extent to which their norms and core values support peace or war; the role that rituals, symbols and ceremonies play in either uniting or dividing societies; the degree to which superordinate institutions exist that span neighboring communities; whether intergroup mechanisms for conflict management and resolution exist; and the presence of political leadership for peace versus war.

A core theory of sustaining peace . We have also worked with a broad group of peace, conflict and sustainability scholars to conceptualize how these many variables operate as a complex system by mapping their relationships in a causal loop diagram and then mathematically modeling their core dynamics This has allowed us to gain a comprehensive understanding of how different constellations of factors can combine to affect the probabilities of sustaining peace.

Bottom-up and top-down assessments . Currently, the Sustaining Peace Project is applying techniques such as natural language processing and machine learning to study markers of peace and conflict speech in the news media. Our preliminary research suggests that linguistic features may be able to distinguish between more and less peaceful societies. These methods offer the potential for new metrics that can be used for more granular analyses than national surveys.

We have also been working with local researchers from peaceful societies to conduct interviews and focus groups to better understand the in situ dynamics they believe contribute to sustaining peace in their communities. For example in Mauritius , a highly multiethnic society that is today one of the most peaceful nations in Africa, we learned of the particular importance of factors like formally addressing legacies of slavery and indentured servitude, taboos against proselytizing outsiders about one’s religion, and conscious efforts by journalists to avoid divisive and inflammatory language in their reporting.

Today, global indices drive funding and program decisions that impact countless lives, making it critical to accurately measure what contributes to socially just, safe and thriving societies. These indices are widely reported in news outlets around the globe, and heads of state often reference them for their own purposes. For example, in 2017 , Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez, though he and his country were mired in corruption allegations, referenced his country’s positive increase on the GPI by stating, “Receiving such high praise from an institute that once named this country the most violent in the world is extremely significant.” Although a 2019 report on funding for peace-related projects shows an encouraging shift towards supporting positive peace and building resilient societies, many of these projects are really more about preventing harm, such as grants for bolstering national security and enhancing the rule of law.

The Sustaining Peace Project, in contrast, includes metrics for both positive and negative peace, is enhanced by local community expertise, and is conceptually coherent and based on empirical findings. It encourages policy makers and researchers to refocus attention and resources on initiatives that actually promote harmony, social health and positive reciprocity between groups. It moves away from indices that rank entire countries and instead focuses on identifying factors that, through their interaction, bolster or reduce the likelihood of sustaining peace. It is a holistic perspective.

Tracking peacefulness across the globe is a highly challenging endeavor. But there is great potential in cooperation between peaceful communities, researchers and policy makers to produce better methods and metrics. Measuring peace is simply too important to get only half-right.

Peace Processes

The United Nations Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth, Ms Jayathma Wickramanayake, launched today – Wednesday 17 July 2019 – the policy paper “ WE ARE HERE: An Integrated Approach to Youth-Inclusive Peace Processes ” during a briefing of the United Nations’ Security-Council on Youth, Peace and Security. This paper explores the roles that young people can play in peacebuilding processes.

Across the world, young people are actively working to support peace processes , and are calling for a space in ongoing peace negotiations but continue to be unrepresented and excluded from decisions that will directly impact their present and future prospects for peace. More critically, in transitioning to a post-war state, young people from the foundations of a democratic and just society. Today, one in three internet users is a young person, [1] creating opportunities for people-led movements to significantly influence ongoing peacemaking efforts. This too increases the need for better coordination between actors across the board. This complex and dynamic landscape offers a broad range of strategic entry points for third-party mediation support groups to look for creative solutions in negotiating peace.

Against this backdrop, and after several years of advocacy by over 11,000 young people from over 110 countries, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted its first-ever resolution on Youth, Peace and Security (UNSCR 2250) on December 9 th, 2015. [2] This important step places youth firmly on the peace and security/sustaining peace agenda , recognizing the role of youth in peacebuilding, and advocates for youth engagement and participation in peace processes. The UN Security Council Resolution 2419 (2018) further reaffirmed the need to fully implement 2250 and called on all relevant actors to consider ways for increasing the representation of young people when negotiating and implementing peace agreements. The Agenda 2030, and SDG 16 calls for the promotion of and support to peaceful, just and inclusive societies.

UNSCR 2250 (2015) and UNSCR 2419 (2018) make the clearest justification and urge member states to consider ways to increase the inclusive representation of youth in decision-making at all levels, including possible integrated mechanisms for youth to participate meaningfully in peace processes and dispute resolution . The Security Council recognized the critical need to engage young people not as a security threat, but as partners in key decision-making efforts including in political negotiations that have a direct impact on their lives today and in the future. The Resolution also mandates international bodies, including the United Nations, to partner with youth at a strategic level and to improve the coordination and interaction regarding the needs of youth in conflict situations.

To explore the roles that young people can play, based on research, politics, experiences of thought leaders and smart practice, and to understand what young people are currently doing to influence peace processes, the very first International Symposium focused on youth and peace processes was convened. The Symposium built and benefited from the past and ongoing work on the development process of the Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security. The symposium was co-hosted by the Governments of Finland, the State of Qatar, and the Government of Colombia, and co-organized by the office of the United Nations Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth (OSGEY) and Search For Common Ground (Search), in partnership with the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY). To learn more about the Symposium, please view the Summary Report HERE .

As part of the organization of the Symposium, two young researchers were contracted to research and develop the first global policy paper on youth participation in peace processes. The aim of the seminal paper was to document, assess and highlight where, how, and in what forms young people have participated in – and influenced – peace processes over the last 20 years. The paper set a foundation for the discussions and topics raised in the Symposium. The two independent researchers were Ali Altiok and Irena Grizelj, who spent the five months prior to the Symposium to design, research, develop and lead the drafting of the paper. The paper – ‘ We are Here: An Integrated Approach to Youth-Inclusive Peace Processes’ – was shared with the Symposium participants a few days ahead of the Symposium as a key reading.

Click HERE to read the Policy Paper “WE ARE HERE: An Integrated Approach to Youth-Inclusive Peace Processes”.

Click HERE to access the Press Release.

Click HERE to access the Trello board including visuals and messaging on Youth, Peace and Security.

[1] UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children . 2017 Report .

[2] The United Nations Security Council Resolution 2250 states: “the term youth is defined […] as persons of the age of 18–29 years old, and further noting the variations of definition of the term that may exist on the national and international levels.”

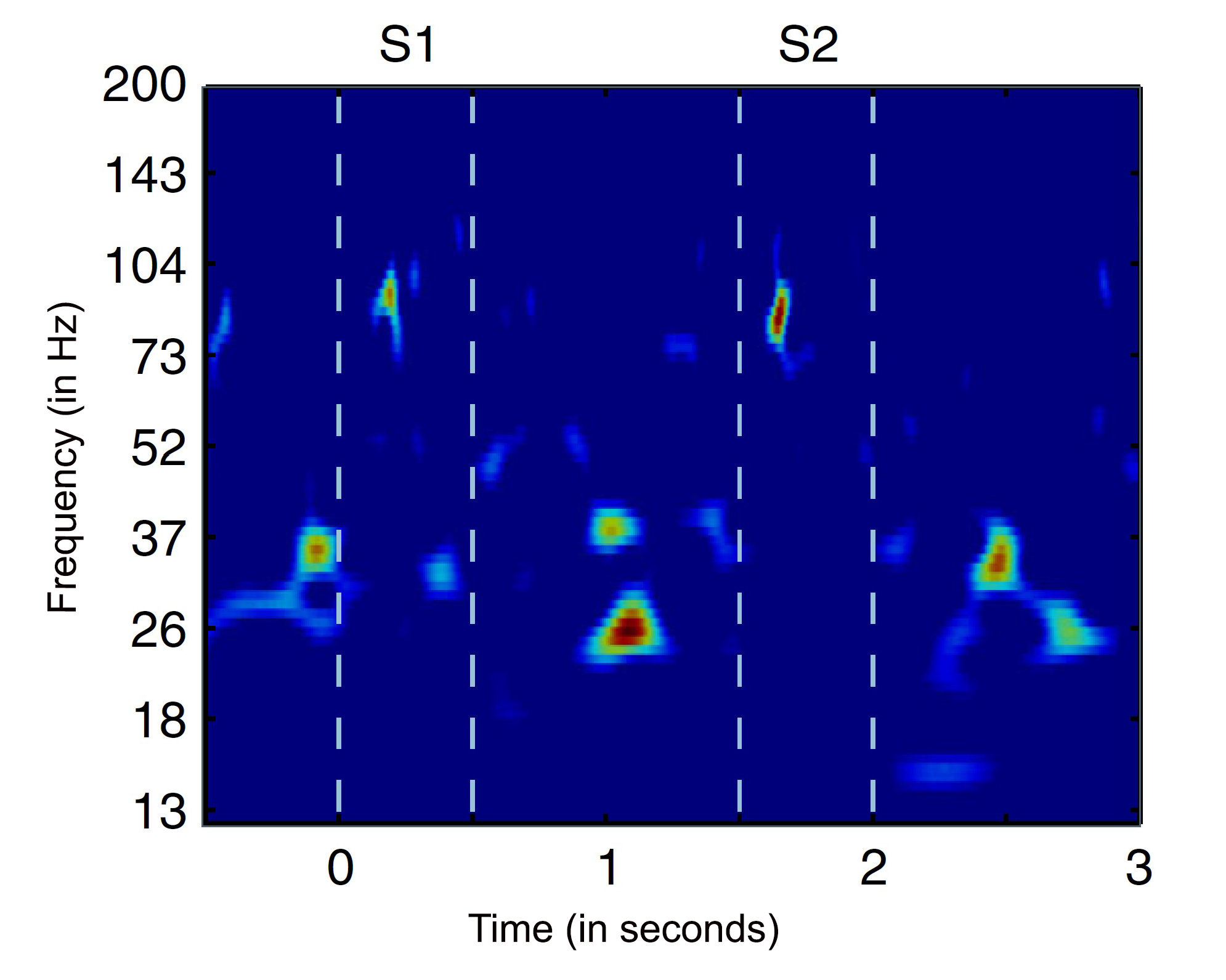

In the brain, bursts of beta rhythms implement cognitive control

Bursts of brain rhythms with “beta” frequencies control where and when neurons in the cortex process sensory information and plan responses. Studying these bursts would improve understanding of cognition and clinical disorders, researchers argue in a new review.

The brain processes information on many scales. Individual cells electrochemically transmit signals in circuits but at the large scale required to produce cognition, millions of cells act in concert, driven by rhythmic signals at varying frequencies. Studying one frequency range in particular, beta rhythms between about 14-30 Hz, holds the key to understanding how the brain controls cognitive processes—or loses control in some disorders—a team of neuroscientists argues in a new review article.

Drawing on experimental data, mathematical modeling and theory, the scientists make the case that bursts of beta rhythms control cognition in the brain by regulating where and when higher gamma frequency waves can coordinate neurons to incorporate new information from the senses or formulate plans of action. Beta bursts, they argue, quickly establish flexible but controlled patterns of neural activity for implementing intentional thought.

“Cognition depends on organizing goal-directed thought, so if you want to understand cognition, you have to understand that organization,” said co-author Earl K. Miller , Picower Professor in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. “Beta is the range of frequencies that can control neurons at the right spatial scale to produce organized thought.”

Miller and colleagues Mikael Lundqvist, Jonatan Nordmark and Johan Liljefors at the Karolinska Institutet and Pawel Herman at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden, write that studying bursts of beta rhythms to understand how they emerge and what they represent would not only help explain cognition, but also aid in diagnosing and treating cognitive disorders.

“Given the relevance of beta oscillations in cognition, we foresee a major change in the practice for biomarker identification, especially given the prominence of beta bursting in inhibitory control processes … and their importance in ADHD, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease,” they write in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences .

Experimental studies covering several species including humans, a variety of brain regions, and numerous cognitive tasks have revealed key characteristics of beta waves in the cortex, the authors write: Beta rhythms occur in quick but powerful bursts; they inhibit the power of higher frequency gamma rhythms; and though they originate in deeper brain regions, they travel within specific locations of cortex. Considering these properties together, the authors write that they are all consistent with precise and flexible regulation, in space and time, of the gamma rhythm activity that experiments show carry signals of sensory information and motor plans.

“Beta bursts thus offer new opportunities for studying how sensory inputs are selectively processed, reshaped by inhibitory cognitive operations and ultimately result in motor actions,” the authors write.

For one example, Miller and colleagues have shown in animals that in the prefrontal cortex in working memory tasks, beta bursts direct when gamma activity can store new sensory information, read out the information when it needs to be used, and then discard it when it’s no longer relevant. For another example, other researchers have shown that beta rises when human volunteers are asked to suppress a previously learned association between word pairs, or to forget a cue because it will no longer be used in a task.

In a paper last year, Lundqvist, Herman, Miller and others cited several lines of experimental evidence to hypothesize that beta bursts implement cognitive control spatially in the brain , essentially constraining patches of the cortex to represent the general rules of a task even as individual neurons within those patches represent the specific contents of information. For example, if the working memory task is to remember a pad lock combination, beta rhythms will implement patches of cortex for the general steps “turn left,” “turn right,” “turn left again,” allowing gamma to enable neurons within each patch to store and later recall the specific numbers of the combination. The two-fold value of such an organizing principle, they noted, is that the brain can rapidly apply task rules to many neurons at a time and do so without having to re-establish the overall structure of the task if the individual numbers change (i.e. you set a new combination).

Another important phenomenon of beta bursts, the authors write, is that they propagate across long distances in the brain, spanning multiple regions. Studying the direction of their spatial travels, as well as their timing, could shed further light on how cognitive control is implemented.

New ideas beget new questions

Beta rhythm bursts can differ not only in their frequency, but also their duration, amplitude, origin and other characteristics. This variety speaks to their versatility, the authors write, but also obliges neuroscientists to study and understand these many different forms of the phenomenon and what they represent to harness more information from these neural signals.

“It quickly becomes very complicated, but I think the most important aspect of beta bursts is the very simple and basic premise that they shed light on the transient nature of oscillations and neural processes associated with cognition,” Lundqvist said.“This changes our models of cognition and will impact everything we do. For a long time we implicitly or explicitly assumed oscillations are ongoing which has colored experiments and analyses. Now we see a first wave of studies based on this new thinking, with new hypothesis and ways to analyze data, and it should only pick up in years to come.”

The authors acknowledge another major issue that must be resolved by further research—How do beta bursts emerge in the first place to perform their apparent role in cognitive control?

“It is unknown how beta bursts arise as a mediator of an executive command that cascades to other regions of the brain,” the authors write.

The authors don’t claim to have all the answers. Instead, they write, because beta rhythms appear to have an integral role in controlling cognition, the as yet unanswered questions are worth asking.

“We propose that beta bursts provide both experimental and computational studies with a window through which to explore the real-time organization and execution of cognitive functions,” they conclude. “To fully leverage this potential there is a need to address the outstanding questions with new experimental paradigms, analytical methods and modeling approaches.”

Related Articles

Paper: to understand cognition—and its dysfunction—neuroscientists must learn its rhythms.

Study reveals a universal pattern of brain wave frequencies

Anesthesia blocks sensation by cutting off communication within the cortex

Anesthesia technology precisely controls unconsciousness in animal tests

COMMENTS

Journal of Peace Research (JPR) is an interdisciplinary and international peer reviewed bimonthly journal of scholarly work in peace research.Journal of Peace Research strives for a global focus on conflict and peacemaking. The journal encourages a wide conception of peace, but focuses on the causes of violence and conflict resolution.

In this paper, we propose a theoretical framework and methodologies to make peace beyond the absence of war researchable. The framework is designed to capture varieties of peace between and beyond ...

The origins of any peace process or agreement—changes in the geo-political or regional situation, initiatives from civil society, secret meetings, chance encounters between significant actors—are often unrecognized at the time. ... Summary of Results from a Comparative Research Project', CCDP Working Paper 4 (Geneva: CCDP, 2009). 15.

Conflict, peace and security are some of the enduring concerns of the Peace Research Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. They have become integrated in the dominant disciplines of international relations and political science and now are also part of most of the social science disciplines, such as economics, sociology, public policy, gender studies, international law and so on.

The ability of peacekeeping to safeguard the capital and key infrastructure also facilitates mediation efforts. As Arnault (2006) notes, the need to provide physical security extends to all parties involved in the mediation process, especially when the successful implementation of the peace process is still very much in doubt. 13

5 1 The four classic pillars of transitional justice are criminal prosecutions, truth seeking, reparations and various forms of reform and prevention, sometimes referred to as guarantees of non-repetition. This paper is aimed at understanding how the United Nations has engaged in transi-tional justice in the context of peace process-

the peace process, only 0.05 percent of each society met the other in. ... War and Defence—Essays in Peace Research, 2 (Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers, 1975), 282-304; Johan Galtung, "The ...

After nearly two decades of U.S. presence, the Afghan conflict between the central government and the Taliban reached a deadly stalemate, taking a hundred lives a day from each side between 2018 and 2021. However sad, the international community viewed this impasse as a sign of Afghanistan's ripeness for peace.

This paper examines how the research on, and the practice of, peace mediation has evolved in the past 25 years, with a particular focus on the hypothesised factors that explain mediation 'success' and argues for an explicit re-centring of the political in peacemaking. The analysis highlights how research on peacemaking has seen a growth of ...

The successive failure of the Middle East Peace Process (MEPP) warrants a reappraisal of the international community's role in moving the parties towards conflict resolution. Like few other issues, this dispute triggers unconscious assumptions, biases, and preconceptions even among those tasked with making peace.

Saad Abudayeh. Introduction. The aim of this paper is to explore the constraints and prospects. the Arab-Israeli peace process. It takes into account the developments since the establishment of Israel in 1948, when the British mandate ended, and the UN General Assembly through its Resolution No. divided Palestine and created the state of Israel.

This research focuses on how conflict parties and mediators navigate the inclusion of people and agendas of change in peace processes. Central to this work are the PA-X Peace Agreement Database and the support the programme provides to peacemakers, particularly through its partner Conciliation Resources (see impact for examples).

But peace is more than not fighting. The PPI, launched in 2009, was supposed to recognize this and track positive peace, or the promotion of peacefulness through positive interactions like ...

The overall aim is to provide researchers and actors in the global peace market with a distillation of the salient studies and findings from research on women's involvement in the peace process. Such an effort is necessary to bring together the sparse literature on women's contribution to peace and to reveal existing gaps in the literature ...

PDF | The article examines the issues and challenges in the peace process in Myanmar following the February 2021 military coup. | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ResearchGate

The media can play a positive role in peace building/conflict prevention. Recognition of ... need for more research. This review draws on a mixture of academic papers and grey literature. ... news and information (Betz, 2018: 2). 'Peace building' is defined as 'a process that facilitates the establishment of durable peace and tries to ...

Mediation, as a means to end armed conflicts, has gained prominence particularly in the past 25 years. This article reviews peace mediation research to date, with a particular focus on quantitative studies as well as on significant theoretical and conceptual works. The growing literature on international mediation has made considerable progress ...

As part of the organization of the Symposium, two young researchers were contracted to research and develop the first global policy paper on youth participation in peace processes. The aim of the ...

PAPER INFO ABSTRACT Received: March 11, 2021 Accepted: June 20, 2021 Online: June 25, 2021 This paper focuses on peace efforts that have been made to bring peace in Afghanistan. The end of the conflict to bring durable peace drives from peaceful dialogues to create a win-win situation for all parties involved in the conflict. Afghanistan

This research paper highlights the prospects and challenges in the ongoing peace efforts. America has taken the most important ... India, Iran, China and Russia welcomed this Peace Process and determined to support the people of Afghanistan. These efforts for peace are encouraged and supported from everywhere but

peace process, which we will refer to in this study as spoiling behaviours. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is largely one that is brought about by spoilers of varying shades and degrees.

Pew Research Center

This paper will consider what is meant by the word "peace" and will discuss the relevance of non-violent approaches to peacemaking in the world today.

In a paper last year, Lundqvist, Herman, Miller and others cited several lines of experimental evidence to hypothesize that beta bursts implement cognitive control spatially in the brain, essentially constraining patches of the cortex to represent the general rules of a task even as individual neurons within those patches represent the specific ...

The Taliban and America have Role of Pakistan in the Afghan Peace Process PJAEE, 17 (12) (2020) 325 signed a peace deal on 29 February 2020, in Doha to end the longest war in the history of ...