Political Science

- Background Research

- Legislative Documents

- Executive Documents

- Judicial Documents

- Legal Publications

Introduction

Background resources, country profiles, key subject databases, comparative politics data resources.

- Conflict, Peace & Security

- Elections & Voting

- Historical & Primary Document Resources

- Political Behavior & Psychology

- Public Opinion Data & Survey Research

- Electoral Data

- Political Conflict Data

- Political Economy

- Political Theory

- United Nations This link opens in a new window

- Debating Resources for Politics and Public Policy

Comparative Politics

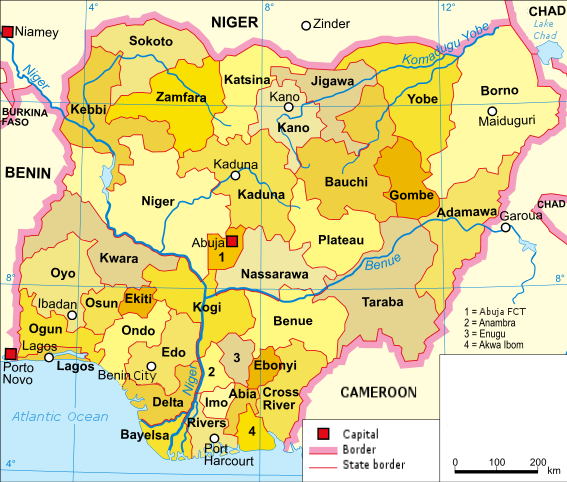

Comparative politics is the comparative study of other countries, citizens, different political units either in whole or in part, and analyzes the similarities and differences between those political units. Comparative politics also entails the political study of non-US political thought. Here are a few tips when choosing resources for comparative political research:

- Use a subject encyclopedia to research major comparative political theories and concepts.

- Use country profiles to locate basic information, facts, and statistics about individual countries.

- Search for research articles in a general article database such as EBSCO Discovery .

- Use a subject database such as PAIS to locate political-specific articles.

- International Encyclopedia of Political Science The International Encyclopedia of Political Science provides a definitive, comprehensive picture of all aspects of political life, recognizing the theoretical and cultural pluralism of our approaches and including findings from the far corners of the world. The eight volumes cover every field of politics, from political theory and methodology to political sociology, comparative politics, public policies, and international relations.

- The Oxford Companion to Comparative Politics The Oxford Companion to Comparative Politics focuses on the major theories, concepts, and conclusions that define the field, analyzing the similarities and differences between political units. Entries cover such topics as failed states, grand strategies, soft power, capital punishment, gender and politics, and totalitarianism, as well as countries such as China and Afghanistan.

This section includes databases that provide detailed profiles of most countries worldwide. Country profiles include basic country facts and figures such as population, capitol cities and so on. They also provide brief summaries of geography, environment, history, current politics and economics.

- BBC News Country Profiles Full profiles provide an instant guide to history, politics and economic background of countries and territories, and background on key institutions.They also include audio and video clips from BBC archives.

- CIA World Factbook Developed by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, the World Factbook offers updated country profiles providing information on the history, people, government, economy, geography, communications, transportation, military and transnational issues for 267 world nations. The website provides a comprehensive collection of world maps that can be freely downloaded. Also includes a Guide to Country Comparisons. Categories include, geography, people and society, the economy, communications, transportation and military. Information can be downloaded into data files.

- Europa World Yearbook This link opens in a new window Europa World Yearbook provides profiles for over 250 countries and territories. Profiles include political and economic information as well as statistics and information on religion, media and press.

- Political Risk Yearbook and CountryData This link opens in a new window Political Risk Yearbook provides political risk reports for the current year for many countries. CountryData allows users to generate exportable tables with political risk rankings and economic indicators for current and historical years, as well as current forecasts, for various countries. More information less... Country Data is available on campus only. Use NYU VPN for off-campus access.

- World Bank Country Profiles Country profiles prepared by World Bank staff are available for 157 nations. Sites provides direct links to the World Bank data catalog for each country along with access to the latest publications, news items, and development topics published by, or related to, World Bank operations.

- Statesman's Yearbook Online This link opens in a new window The Statesman's Yearbook provides information on international affairs, covering key historical events, population, city profiles, social statistics, climate, recent elections, current leaders, defense, international relations, economy, energy and natural resources, industry, international trade, religion, culture, and diplomatic representatives, as well as fact sheets and more.

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports Country profiles and information documents prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). CRS serves as nonpartisan shared staff to congressional committees and Members of Congress.

Subject-specific databases provide articles and resources solely within a specific discipline. This section lists the best political science databases providing coverage of scholarly literature across all major political science areas and sub-disciplines including comparative politics.

- Columbia International Affairs Online (CIAO) This link opens in a new window Columbia International Affairs Online (CIAO) is a source for theory and research in international affairs. It includes scholarship, working papers from university research institutes, occasional papers series from NGOs, foundation-funded research projects, proceedings from conferences, books, journals, case studies for teaching, and policy briefs.

- PAIS International This link opens in a new window PAIS International contains journal articles, books, government documents, statistical directories, grey literature, research reports, conference reports, publications of international agencies for public affairs, public and social policies, and international relations.

- Policy File This link opens in a new window Policy FIle offers access to U.S. foreign and domestic policy papers and gray literature, with abstracts and links to timely reports, papers, and documents from think tanks, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), research institutes, advocacy groups, agencies, and other entities.

- ProQuest Political Science This link opens in a new window ProQuest Political Science gives users access to leading political science and international relations journals. This collection provides the full-text of core titles, many of which are indexed in Worldwide Political Science Abstracts. New to ProQuest Political Science are hundreds of recent, full-text, political science dissertations from U.S. and Canadian universities, as well as thousands of current working papers from the Political Science Research Network.

- Worldwide Political Science Abstracts This link opens in a new window Worldwide Political Science Abstracts provides citations, abstracts, and indexing of the international serials literature in political science and its complementary fields, including international relations, law, and public administration.

- Comparative Study of Electoral Systems The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) is a collaborative program of cross-national research among election studies conducted in over fifty states.

- Comparative Political Dataset The "Comparative Political Data Set" (CPDS) is a collection of political and institutional country-level data provided by Prof. Dr. Klaus Armingeon and collaborators at the University of Berne. It consists of annual data for 36 democratic countries for the period of 1960 to 2014 or since their transition to democracy.

- Eurostat Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, provides statistics at the European level that enable comparisons between countries and regions. Users can bulk download tables and access full metadata and documentation for data that measures indicators across a range of socio-demographic and economic indicators.

- The Quality of Government (QOG) Institute The QOG Institute at the University of Gothenburg studies good governance and corruption on a global scale. QoG provides a range of datasets available for free, and data visualization tools. QoG Standard Dataset contains the most qualitative variables from the Standard Dataset. The QoG Expert Survey is a dataset based on our survey of experts on public administration around the world, available in an individual dataset and an aggregated dataset covering 107 countries.The QoG OECD dataset covers countries who are members of the OECD. The EU Regional Data consists of 450 variables from Eurostat and other sources, covering three levels of European regions - country, major socio-economic regions and basic regions for the application of regional policies.

- << Previous: Legal Publications

- Next: Conflict, Peace & Security >>

- Last Updated: Apr 30, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/polisci

Comparative Politics: its Past, Present and Future

- Original Article

- Published: 15 July 2016

- Volume 1 , pages 397–411, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Philippe C. Schmitter 1

17k Accesses

5 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Comparative politics has always been schzofrenic. It is a powerful method of analysis and a useful source of information. Both have a promising future, but to realize it both will have to change. This essay explores the dilemmas facing the sub-discipline and suggests some solutions regarding assumptions, concepts and units of analysis and description. One reason for optimism is its globalization and shift from a perspective rooted exclusively in the North and West to an increasing participation of scholars from the South and East.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Future of Comparative Politics is its Past

Introduction: Theory’s Landscapes

With the rise of china, what’s new for comparative politics.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Comparaison n’est pas raison, Maurice Duverger Raisonner er n’est pas comparer , Philippe Schmitter

Comparative politics has a promising future, both as a method of analysis and as a provider of useful information. To realize that future, however, it will have to change some—but not all—of its presuppositions and practices. Presently, it is at a critical juncture due to the impact of transformations in the nature of ‘real-existing’ politics. Thanks to its globalization as a sub-discipline of political science, it is likely profit from the opportunity. The shift in the recruitment of its practitioners from the North and West toward the East and South should facilitate taking the necessary changes in presuppositions and practices. In other words, the future of comparative politics is not what it used to be. These are the principle theses of the essay that follows.

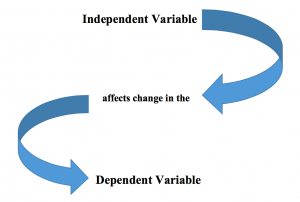

On the one hand, comparison is an analytical method—probably the best available one—for advancing valid and cumulative knowledge about politics. At least since Aristotle it has been argued that only by identifying and labeling the generic relations of power and then examining how they produce variable or invariable effects in otherwise different societies, can scholars claim that their discipline is scientific. The core of the method is really quite simple and it helps to explain why comparativists tend to be addicted to two things: (1) classification systems; and (2) the Latin expression, ceteris paribus . First, it is necessary to identify what units have in common by placing them in some generic category—say, democratic as opposed to autocratic regimes. Then, the category may be extended further into subtypes per genus et differentiam —say, democracies with single dominant party systems, with alternating two party systems, with alternating multiple party coalitional systems, and with hegemonic (non-alternating) multiparty systems. Once these factors have been controlled for, the Latin kicks in again, namely, the assumption that units in the same category share the same characteristics and, therefore, that “all things being equal” it must be something that they do not share—say, level of trade union organization that is responsible for producing the differences in outcome that the analyst is interested in—say, the level of public spending. Of course, waving that magic Latin wand does not really control for all of the potential things that might be causing variation in public spending, but it does help to eliminate some of them.

On the other hand, comparison has always had a practical objective, namely, to produce useful descriptive information about how politics is conducted in countries other than one’s own. Makers of public policy and investors of private funds, for example, need specialized bits of information to make reasonable choices when dealing with ‘exotic’ actors and organizations. They could not care less about the ‘scientific basis’ of the information, provided it is accurate and reliable. Predicting behavior and, thereby, lowering the risk involved in transactions with foreigners are what they are interested in, and fancy theories may be no better at this than simple projections from past experience or calculations of statistical probability.

While there is no reason why these two aspects of the sub-discipline should contradict each other in principal, they often do in practice. Accurate and reliable information for description usually comes in the form of expressions and perceptions generated by the actors themselves; cumulative and valid data for analysis depend on analogies and concepts rooted in generic categories, themselves embedded in specific theories. The closer they are to each other, the narrower will be the potential for comparison in time and space—until comparative politics becomes nothing more than a description of “other people’s politics,” and every case has its unique explanation. Footnote 1

1 A Challenging (but Rewarding) Specialization

The student in search of a field of specialization should be aware that the threshold for entry into comparative politics is high. You will normally be expected to learn at least one foreign language—the more the better and the more exotic the better! You will also have to spend long hours familiarizing yourself with someone else’s history and culture—and be willing to spend considerable time living away from home, often in rather uncomfortable places. The actors you study will be irrevocably “historical” in two senses: (1) their actions in the present will be affected by their memories of what happened in the past; and (2) their actions in the future will be altered by what they have learned from the present. If you have not spent those hours, you will not be able to understand what and why your subjects and their institutions behave the way they do.

If you do accept the challenge of comparing polities, be prepared to cope with controversy. There have been periods of relative tranquility when the sub-discipline was dominated by a single paradigm. For example, until the 1950s, scholarship consisted mostly of comparing constitutions and other formal institutions of Europe and North America, interspersed with wise comments about more informal aspects of national character and culture. ‘Behaviorialism’ became all the rage for a shorter while, during which time mass sample surveys were conducted across several polities in efforts to discover the common social bases of electoral results, to distinguish between “bourgeois/materialist” and “post-bourgeois/post-materialist” value sets, or to search for the ‘civic culture’ that was alleged to be a pre-requisite for stable democracy. ‘Aggregate data analysis’ of quantitative indicators of economic development, social structure, regime type and public policy at the national and sub-national levels emerged at roughly the same time. ‘Structural-functionalism’ responded to the challenge of bringing non-European and American polities into the purview of comparativists, by seeking to identify universal tasks that all political systems had to fulfill, regardless of differences in formal institutions or informal behaviors.

None of these approaches has completely disappeared and most major departments or faculties of political science are likely to have remnants of some of them. But none is “hegemonic” at the present moment. As one of its most distinguished practitioners described them, the present day comparativists are sitting at different tables, eating from different menus and not speaking to each other—not even to acknowledge their common inheritance from the same distinguished ancestors. Footnote 2

2 A Shifting Center of Gravity?

There is, however, one characteristic that they all share. Every one of these approaches originated in the United States of America, usually having been borrowed from some adjacent academic discipline. The prospective student interested in comparative politics had only to look at the dominant “fads and fashions” in American political science, trace their respective trajectories and intercepts, and he or she could predict where comparative politics would be going for the next decade or more. Who could doubt that this sub-discipline of political science as practiced in the United States of America showed the rest of the world “the face of its future”? Footnote 3

Nevertheless, a more rapidly growing number of comparativists have been coming from countries that barely recognized the discipline a few decades ago. There is a Chinese saying (exploited by Mao Tse-Dung): “Either the East Wind prevails over the West Wind or the West Wind prevails over the East Wind.” Increasingly, in comparative politics neither the East nor the West Wind prevails and the same is true of the North and South ones. The Winds of Change have become variable and more unpredictable. They no longer come overwhelmingly from a single direction (as Mao predicted), although it is not unimaginable that in a short time there will be more Chinese political scientists than American. Today, innovations in theories, concepts and methods can come from any direction.

One of the central assumptions of this essay is that the future of comparative politics should (and, hopefully, will) diverge to some degree from the trends and trajectories followed in recent years by many (if certainly not all) political scientists in the United States. As I have expressed it elsewhere, the sub-discipline is presently “at the crossroads” and the direction that its ontological and epistemological choices take in the near future will determine whether it will continue to be a major source of critical innovation for the discipline as a whole, or dissolve itself into the bland and conformist “Americo-centric” mainstream of that discipline. Footnote 4

3 An Improvement in Method and Design

Let me begin, however, with some self-congratulation. Thanks to the assiduous efforts of methodologically minded colleagues (mostly Americans, it is true), much fewer students applying the comparative method neglect to include in their dissertations: (1) an explicit defense of the cases selected—their number and analogous characteristics, (2) a conscious effort to ensure sufficient degrees of freedom between independent and dependent variables, (3) an awareness of the potential pitfalls involved in selecting the cases based on the latter, (4) a greater sensitivity to the universe of relevant units and to the limits to generalizing about the external validity of findings. Footnote 5

These important gains in methodological self-consciousness have produced (or been produced by) some diminution in the “class warfare” between quantitatively and qualitatively minded political scientists. Some of the former persist in asserting their intrinsic “scientific” superiority over the latter, but there is more and more agreement that many of the problems of design and inference are common to both and that the choice between the two should depend more on what it is the one wishes to explain or interpret than on the intrinsic superiority of one method over the other—or, worse, how one happens to have been trained as a graduate student. Indeed, from my recent experience in two highly cosmopolitan institutions, the European University Institute in Florence and the Central European University in Budapest, I have encountered an increasing number of dissertations in comparative politics that make calculated and intelligent use of both methods—frequently with an initial large N comparison wielding relatively simple quantitative indicators to establish the broad parameters of association, followed by a small N analysis of carefully selected cases with sets of qualitative variables to search for specific sequences and complex interactions to demonstrate causality (as well as the impact of neglected or ‘accidental’ factors). To use the imaginative vocabulary of Charles Tilly, such research combines the advantages of “lumping” and “splitting”. Footnote 6 Hopefully, this is a trend that will continue into the future.

The real challenge currently facing comparative politics, however, comes from a third alternative, namely, “formal modeling” almost invariably based on individualist, rational choice assumptions. Much of this stems from a strong desire on the part of American political scientists to imitate what they consider to be the “success” of the economics profession in acquiring greater status within academe by driving out of its ranks a wide range of dissident approaches and establishing a foundation of theoretical (neo-liberalism) and methodological (mathematical modeling) orthodoxy upon which their research is based. This path toward the future would diverge both methodologically and substantively from the previously competing quantitative and qualitative ones. It would involve the acceptance of a much stronger set of limiting initial assumptions, exclusive reliance on the rational calculations of individual actors to provide “micro-foundations,” deductive presumptions about the nature of their interactions and reliance on either “stylized facts” or “mathematical proofs” to demonstrate the correctness of initial assumptions and hypotheses derived from them. The comparative dimension enters into these equations to prove that individual behavior is invariant across units or, where it is not, that institutions (previously chosen rationally) can make a difference. The “bread and butter” of comparison—namely, the contingent nature of politics due to the relevance of context—is excluded. Given the same incentives, actors (always individuals) will always choose the same thing.

4 A Common (but Still Diverse) Perspective

Presently, most comparativists would (probably) call themselves: institutionalists, although there exist many different types of them. About all they seem to agree upon is that “institutions matter.” They differ widely on what institutions are, how they come about, why is it that they matter, and which ones matter more than others. Moreover, some of them will even admit that other things also matter: collective identities, citizen attitudes, cultural values, popular memories, external pressures, economic dependencies, even instinctive habits and informal practices—not mention the old favorites of Machiavelli, fortuna and virtù —when it comes to explaining and, especially, to understanding political outcomes.

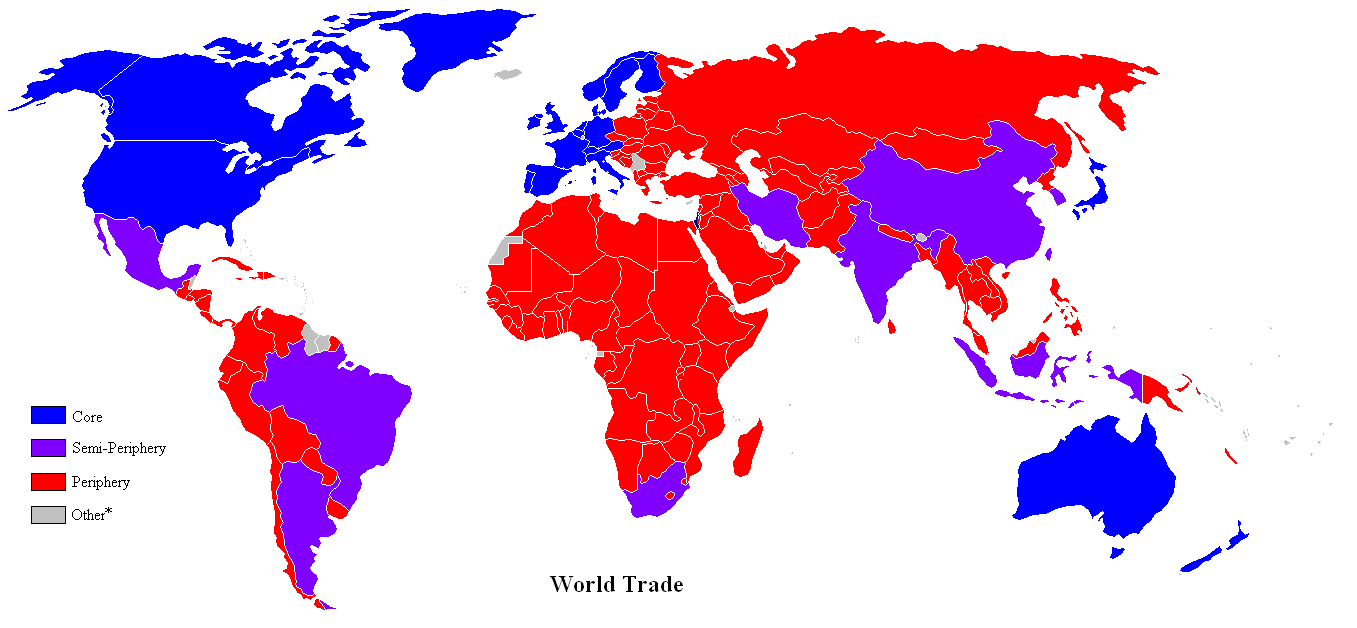

Comparative politics finds itself at a critical crossroad. The safest thing one can say today about its future of comparative politics is that it should not and will not be the same as in the past. Of course, not everything is going to have to change. Comparative politics will continue to bear major responsibility for the objective description of processes and events in “other peoples’ countries” and, hence, for providing systematic and reliable information to those politicians (in and out of power) and to those administrators (at the top and bottom) charged with making and implementing national policies concerning these countries. The end of the Cold War and collapse of the Soviet Empire has led to an impressive increase in the sheer number of polities whose (allegedly autonomous) behavior has to be described. The globalization of capitalism has produced increasingly indirect and articulated systems of cross-border production, transport and distribution that are much more sensitive to disturbances in the behavior of their most remote and marginal components. The ubiquitous penetration of information and communications technology (ICT) has meant that the happenings anywhere in the world are being immediately transmitted everywhere and comparativist pundits will be expected “to place them in context” for public consumption.

Comparison between “real-existing polities” will also remain the best available research method for analyzing similarities and differences in behavior and for inferring the existence of patterns of regularity with regard to the causes and consequences of politics. It will always be the second best instrument for this purpose, but as long as it remains impossible for students of politics to experiment with most of their subjects and subject matter, political scientists will have to settle for analyzing as systematically as possible variations they cannot control directly.

5 A Need for Adaptation

The core of my argument has been that comparative political analysis, if it is to remain significant, productive and innovative in the future, has to reflect the “real-existing” environment from which it should draw its observations and to which it should refer its findings. Most importantly, its assumptions and concepts will have to change to retain the same explanatory value. Take, for example, the admonition made by a comparativist advocate of rational choice, Carles Boix. He asserts that “clear models about actors and preferences, strategical interaction (i.e., ‘game theory PCS), endogenization of variables one-at-a-time” constitute a threesome that is capable of generating non-trivial findings about politics in the contemporary environment. But what if what is needed are “fuzzy and under-specified models about a plurality of types of actors with preferences that are contingent upon differences in political setting,” “strategic interaction between a large number of players at different levels of aggregation with inconsistent payoffs,” “constant communication and multiple interdependencies” and “endogenization not of single discrete variables, but of patterns of multiple variables within the same time frame”? Would not such a transposition from the simplified world of conceptual clarity, stylized two-person games and ‘stepwise’ causality risk producing findings that bare no relation to the complexity of the “real-existing” world of politics? My contention is that if their concepts, assumptions and hypotheses fail to capture, not all (that would be impossible), but at least some of the core characteristics of their subject matter, comparativists will at best report only trivial or irrelevant findings. They will address problems and provide answers to issues that are primarily internal to their own scholastic paradigm. These are not likely to be the problems that citizens and rulers have to cope with or the answers they expect comparative political research to provide.

One thing that differentiates comparativists from their colleagues who only study one polity or one international system is supposed to be greater sensitivity to contextual factors that are so deeply embedded that they are often taken for granted or treated as “exceptional” by Americanists or “unique” by international relations specialists. Inversely, they should be especially well equipped to identify and incorporate the trends that affect—admittedly, to differing degrees—virtually all the world’s polities.

6 A Change in the Unit of Analysis?

Two of these trends, in my opinion, are sufficiently pervasive as to affect the basic design and conduct of comparative research. They are: (1) increased complexity; and (2) increased interdependence. However independent their sources may be—for example, logically speaking, a polity may become more complex without increasing its interdependence upon other polities and a polity may enter into increasingly interdependent relations with others while reducing its internal complexity through specialization—these two trends tend to be related and, together, they produce something that Joseph Nye and Robert Keohane have called “complex interdependence”. Footnote 7

One major implication that I draw from this is that complex interdependence is having an increasing influence not just on the substance of politics, but also upon its form. It is changing, in other words, the units that we should be using for specifying our theories and collecting our data and the levels at which we should be analyzing these data.

Complexity: this undermines one of the key assumptions of most of traditional comparative political research, namely, that the variable selected and observed with equivalent measures will tend to produce the same or similar effect(s) across the units being compared.

Interdependence: this undermines the most important epistemological assumption in virtually all comparative research, namely, that the units selected for comparison are sufficiently independent of each other with regard to the cause–effect relationship being examined. Footnote 8

Complex Interdependence: the ‘compound’ condition makes it difficult, if not impossible, to determine what constitutes an independent cause (and, hence, an independent effect) and whether the units involved have an independent political capacity to choose and implement (and, therefore, to act as agents connecting cause and effect).

When Aristoteles (allegedly) gathered data on the ‘social constitutions’ of 158 Greek city-states, he set an important and enduring precedent. The apposite units for comparison should be of the same generic type of polity and at the same level of aggregation. And they should be more-or-less self-sufficient and possess a distinctive identity. Since then, almost all theorizing and empirical analysis has followed this model. One could compare “empires” or “alliances of states” or “colonies of states,” but not across these categories. Most of all, the vast proportion of effort has gone into studying supposedly ‘sovereign’ states whose populations supposedly shared a unique ‘national identity.’ It was taken for granted that only this type of polity possessed the requisite capacity for “agency” and, therefore, could be treated as equivalent for comparative purposes.

In the contemporary setting, due to differing forms of complexity and degrees of interdependence, as well as the compound product of the two, it has become less and less possible to rely on the properties of sovereignty and nationality to identify equivalent units. No polity can realistically connect cause and effect and produced intended results without regard for the actions of others. Virtually all polities have persons and organizations within their borders that have identities, loyalties and interests that overlap with persons and organizations in other polities. Nor can one be assured that polities at the same formal level of political status or aggregation will have the same capacity for agency. Depending on their insertion into multi-layered systems of production, distribution and governance, their capacity to act or react independently to any specific opportunity or challenge can vary enormously.

From these observations, I conclude not only that comparativists need to dedicate much more thought to the collectivities they do choose and the properties these units of analysis supposedly share with regard to the specific institution, policy or behavior that is being examined. However, I should stress that comparativists should not panic. There still remains a great deal of differences that can only be explained by conditions within national polities, but exorcising or ignoring the complex external context in which these units are embedded would be equally foolish.

But what is the method one should apply when comparing units in such complex settings? The traditional answer is “to tell a story.” After all, what does a political historian—comparative or not—do but construct a narrative that attempts to pull together all the factors within a specified time period that contributed to producing a specific outcome. Unfortunately, such narratives—however insightful—are usually written in “ideographic” terms, i.e., those used by the actors or the authors themselves. Systematic and cumulative comparison across units (or even within the same unit over time) requires a “nomothetic” language, i.e., one that is based on terms that are specific to a particular approach or theory, not to a unique case. A first step would be to invent or re-invent “ideal-type” concepts so that they were more capable of grasping “fuzzy,” “contaminated,” and “layered” interrelationships among individuals and, especially, organizations (since the latter are much more salient components of contemporary political life).

7 A ‘Prime Mover’?

The practice of comparative political research does follow and should recognize changes in “real-existing politics,” but it always does so with a considerable delay. Footnote 9 As I mentioned above, the most important set of generic changes that have occurred in recent decades involves the spread of “complex interdependence.” There is absolutely nothing new about the fact that formally independent polities have extensive relations with each other. What is novel is not only the sheer magnitude and diversity of these exchanges, but also the extent to which they penetrate into virtually all social, economic and cultural groups and into almost all geographic areas within these polities. Previously, they were mainly concentrated among restricted elites living in a few favored cities or regions. Now, it takes an extraordinary political effort—a “firewall”—to prevent the population anywhere within national borders from becoming “contaminated” by the flow of foreign ideas and enticements. “Globalization” has become the catch-all term for these developments, even if it tends to exaggerate the evenness of their spread and scope across the planet.

Globalization has certainly become the independent variable—the ‘prime mover’—of contemporary political science. It can be defined as an array of transformations at the macro-level that tend to cluster together, reinforce each other and produce an ever accelerating cumulative impact. All of these changes have something to do with encouraging the number and variety of exchanges between individuals and social groups regardless of national borders by compressing their interactions in time and space, lowering their costs and more easily overcoming previous barriers—some technical, some geographical, but mostly political. By most accounts, the driving forces behind globalization have been economic. However, behind the formidable power of increased market competition and technological innovation in goods and services lies a myriad of decisions by national political authorities to tolerate, encourage and, sometimes, subsidize these exchanges, often by removing policy-related obstacles that existed previously—hence, the close association of the concept of globalization with that of liberalization. The day-to-day manifestations of globalization appear so natural and inevitable that we often forget they are the product of deliberate decisions by governments that presumably understood the consequences of what they have decided to laisser passer and laisser faire .

Its impact upon specific national institutions and practices is highly contentious, but two (admittedly hypothetical) trends would seem to have special relevance for the conduct of comparative political inquiry:

Globalization narrows the potential range of policy responses, undermines the capacity of (no longer) sovereign national states to respond autonomously to the demands of their citizenry and, thereby, weakens the legitimacy of traditional political intermediaries and state authorities;

Globalization widens the resources available to non-state actors acting across national borders and shifts policy responsibility upward to trans-national quasi-state actors—both of which undermine formal institutions and informal arrangements at the national level, and promote the development of trans-national interests and the diffusion of trans-national norms.

Comparativists have occasionally given some thought to the implications of these developments for their units of observation and analysis, but have usually rejected the need to change their most deeply entrenched strategy, namely, to rely almost exclusively upon the so-called “sovereign national state” as the basis for controlling variation and inferring similarities and differences in response to the impact of variation in (allegedly) independent conditions. They (correctly) observe that most individuals still identify primarily (and many exclusively) with this unit and that national variables when entered into statistical regressions or cross-tabulations continue to predict a significant amount of variation in attitudes and behavior. Hence, if one is researching, say, the relation between gender and voting preferences, most of the subjects surveyed will differ from national state to national state—and this will usually be greater than the variation between sub-units within respective national states.

My conclusion is that it has become less and less appropriate to rely on the properties of sovereignty, nationality and stateness when identifying the relevant units for theory, observation and inference. No doubt, comparative politics at the descriptive level will continue to dedicate most of its effort to formally sovereign national states. That is the level at which such information is normally consumed by policy makers, the media and the public at large. But at the analytical level, it will have to break through that boundary and recognize that units with the same formal status, e.g., all members of the United Nations or of some regional organization, may have radically different capabilities for taking and implementing collective decisions—and that virtually no national state can afford to presume that it is politically sovereign, economically self-sufficient and culturally distinct. In other words, comparativists have to give more thought to what constitutes a relevant and equivalent case once they have chosen a problem or puzzle to analyze and to do so before they select the number and identity of the units they will compare.

The most difficult challenge will come from abandoning the presumption of “stateness.” Sovereignty has long been an abstract concept that “everyone knew” was only a convenient fiction, just as they also “knew” that almost all states had social groups within them that did not share the same common political identity. One could pretend that the units were independent of each other in choosing their organizations and policies and one could get away with assuming that something called “the national interest” existed and, when invoked, did have an impact upon such collective choices. But the notion of stateness impregnates the furthest corners of the vocabulary we use to discuss politics—especially stable, iterative, “normal” politics. Whenever we refer to the number, location, authority, status, membership, capacity, identity, type or significance of political units, we employ concepts that implicitly or explicitly refer to a universe composed of states and “their” surrounding national societies. It seems self-evident to us that this particular form of organizing political life will continue to dominate all others, spend most publicly generated funds, authoritatively allocate most resources, enjoy a unique source of legitimacy and furnish most people with a distinctive identity. However we may recognize that the sovereign national state is under assault from a variety of directions—beneath and beyond its borders, its “considerable resilience” has been repeatedly asserted. Footnote 10 To expunge it (or even to qualify it significantly) would mean, literally, starting all over and creating a whole new language for talking about and analyzing politics. The assiduous reader will have noted that I have already tried to do this by frequently referring to “polity’ when the normal term should have been “state.” Before comparative politics can embrace complex interdependence, it will have to admit to a much wider variety of types of decision-making units and question whether those with the same formal status are necessarily equivalent and, hence, capable of behaving in a similar fashion.

8 A Focus on Patterns not Variables

Contemporary comparative politics has tended to focus on variables. The antiquated version tried to use distinct conditions to explain the behavior of whole cases—often one of them at a time. The usual approach has been to choose a problem, to select some variable(s) from an appropriate theory, to decide upon a universe of relevant cases, to fasten upon some subset of them to control for other potentially relevant variables, and to go searching for “significant” associations. Not only were the units chosen presumed to reproduce the underlying causal relations independently of each other, but each variable was supposed to make an independent and equivalent contribution to explaining the outcome. We have already called into question the first assumption, and now let us do the same with the second.

Complex interdependence requires that the researcher should attempt to understand the effect(s) of a set of variables (a “context” or “ideal-type” if you will) rather than those of a single variable. And, normally, the problem or puzzle one is working on has a multi-dimensional configuration as well. In neither case is it sufficient simply to standard score and add up several variables (as one does, for example, with such variables as economic or human development, working class militancy, ethnic hostility, quality of democracy, rule of law, etc.). Footnote 11 The idea is to capture the prior interactions and dependencies that form such a context and produce such an outcome. In other words, the strength of any one independent variable depends on its relation with others, just as the importance of any chosen dependent variable depends on how and where it fits within the system as a whole.

There is another way of expressing this point. In the classical ‘analytical’ tradition, you begin by decomposing a complicated problem, institution or process and examining its component parts individually. Once you have accomplished this satisfactorily, you then synthesize by putting them back together and announce your findings about the behavior of the whole. But what if the parts once decomposed change their function or identity and, even more seriously, what if the individual parts cannot be re-composed to form a convincing replica of the whole? In complex political arrangements, the contribution of the parts is contingent upon their role in an interdependent whole. We comparativists have long been aware of the so-called “ecological fallacy,” namely, the potential for error when one infers from the behavior of the whole, the behavior of individuals within it (or vice versa). For example, just because electoral districts in the Weimar Republic with a larger proportion of Protestants and farmers tended to vote more for the Nazi Party (NSDAP), there is no proof that individual Protestants and farmers were more likely to have voted for that party. This can only be demonstrated by data at the apposite level. But what is more important in today’s complex world is the inverse, i.e., “the individualistic fallacy.” This consists in simply adding up—usually without any weighting or multiplying—the observations about individuals and proclaiming an explanation for what they do together. Hence, the more “democratic” the values of sampled persons, the more “democratic” their polity will be. While I would admit that this may work reasonably well where the political process being studied is itself additive, i.e., voting, it can lead to serious fallacies of inference when ‘rational’ individuals interact unequally within pre-existing institutions and networks. Just try to imagine the re-composition of individual preferences and rational choices into a model that would try to predict, say, the level of public spending or the extent of redistribution across social classes!

My contention is that fuzzy “ideal–typical” concepts are virtually indispensable in political science, even if attempts (and there have been many) to pin them down to identical, least of all quantifiable, measures and to rank composites of them have failed. In a world of steadily increasing “complex interdependence,” comparativists will have to rely more and more on such concepts, both to do the explaining and to specify what has to be explained. Just think of all those elements of contemporary politics that involve lengthy chains of causality, the intervention of indirect or delayed agents, the impact of un-intended consequences, the possibility of multiple equilibria, the cooperation of several layers of authority, the emergence of new (and, often, contradictory), properties, the ‘chaotic’ effect of minor variations, the concurrent presence of discrete causes and their compound impact, the un-expected resistance of entrenched habits and standard operating procedures, the effect of random or unique contingencies, the role of anticipated reactions, the ‘invisible constraints’ imposed by established powers, not to mention, the inability of any actor to understand how the whole arrangement functions.

9 A Bunch of Concluding Thoughts

I conclude with three suggestions about the sub-discipline:

Political scientists should abolish the distinction between comparative politics and international relations and re-insert an ontological one between political situations that are subject to rules, embedded in competing institutions and not likely to be resolved by violence, and those in which no reliable set of common norms exists, where monopolistic institutions (including but not limited to states) are in more or less continuous conflict and likely only to resolve these conflicts by force or the threat of force. It used to be believed that this line ran between politics within states and politics between states. This being no longer the case—the probability of war has become greater within the former than between the latter for some time—there is no generic reason that these two “historical” sub-disciplines should be kept apart. How about separating the students of politics into those working on “ruly” and on “unruly” polities, whether they are national, sub-national, supra-national or inter-national?

Comparativists should attempt to include the United States in their research designs when it seems apposite, but they should not expect their Americanist colleagues to join them—at least, not for some time. The present direction of politics in the US is virtually diametrically opposed to the trends I have noted above. Americans (or, better, their present leaders) have reacted with hostility to the prospect of “complex interdependence” and made all possible effort to assert both their internal and external sovereignty. They have repeatedly denied the supremacy of supra-national norms and the utility of international organizations by refusing to regard those legal or organizational constraints that do exist as binding when they contradict or limit the pursuit of so-called national interests, and by withdrawing from them when it seems expedient to do so.

Comparativists—whether of ruly or unruly politics—should be equipping themselves to conceptualize, measure and understand the great increase in the complexity of relations of power, influence and authority in the world that surrounds them. Admittedly, “complexity” is still only a specter haunting the future of their sub-discipline and the answer to meeting this need probably cannot come only from within their own ranks. Hopefully, comparative politics will attract successful “grafts” of theory and method from disciplines in the physical and mathematical sciences that deal with analogous situations, but in the meantime the challenge should be met and the opportunity seized by us. Just picking up a few scattered concepts from within political science, such as multi-layeredness, polycentricity and governance—as I have done—will not carry comparativists far enough. Although, if my experience in studying what must be the most complex polity in the world, the European Union is any indication, ‘real-existing’ politicians and administrators who have to cope with all of this contingency and complexity will be inventing expressive new terms everyday. We should be listening to them, as well as to scholars in other disciplines, to pick up on these emerging arrangements, specify them more clearly where this is possible and search for points in our theoretical frameworks where they can be inserted.

I cannot escape the conviction that this is the most promising path forward for the sub-discipline. And it also seems uniquely capable of explaining something that I think will become more and more salient in the future, namely, equifinality. Since its Aristotelian origins, the comparative method has been applied mainly to explaining differences. Why is it that polities sharing some characteristics, nevertheless, behave so differently? This has allowed the sub-discipline largely to ignore what John Stuart Mill long ago identified as one of the major barriers to developing cumulative social science: the simple fact that, in the “real-existing” world of politics, identical or similar outcomes can have different causes. Perhaps, it is only because my recent research has focused on two areas where this phenomenon has been markedly present: European integration and democratization that I am so sensitive to this ontological problem. In both of these sub-fields, the units involved had quite different points of departure, followed different transition paths, chosen different institutional mixes, generated and responded to quite different distributions of public opinion and, yet, ended up in roughly the same place. Granted there remain significant quantitative and qualitative divergences to be explained—presumably, by relying on the usual national suspects—but the major message they suggest is that of equifinality, i.e., convergence toward similar outcomes.

Of course, not all of the world’s polities are converging toward each other either in institutions, policies or behaviors. There will still be lots of room for comparing differences at the level of national states.

If you have any doubt about whether a given piece of research is comparative, I suggest that you apply “Sartori’s Test.” Check its footnotes and compare the number of them that are devoted exclusively to the country or countries in question and those that refer to general sources, either non-country specific or that include countries not part of the study. The higher the ratio of the latter over the former, the more likely the author will be a genuine comparativist. If the citations are only about the country or countries being analyzed, then, it is very unlikely that the author has applied the comparative method – regardless of what is claimed in the title or flyleaf! “Comparazione e Metodo Comparato,” Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica , Vol. XX, No. 3 (Dicembre 1990), p. 400.

Gabriel Almond ( 1990 ).

“Americanists”—those who study American politics—only very rarely engage in comparison with other countries. On the one hand, they insist that the US is ‘exceptional’ in its favored (and exemplary) status and, therefore, cannot be compared with others. On the other, they claim that everything they observe about American politics—including the methods they apply for making these observations—is ‘universal.’ Comparativists are much less likely to be so schizophrenic.

"Comparative Politics at the Crossroads", Estudios-Working Papers, 1991/27, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales, Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investicaciones (Madrid), 1991.

Here, considerable credit has to be given to the widespread use by comparativists of Gary King et al. ( 1994 ) and, more recently, to its critical counterpart, Henry et al. ( 2004 ). For a more European perspective, see Della Porta and Keating ( 2008 ).

Tilly C ( 1984 ).

Joseph Nye and Robert Keohane ( 1989 ).

This has been called “Galton”s Paradox,” so named for Sir Francis Galton who raised it at a meeting of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1889 by pointing out that the tribes studied by anthropologists might not be independent of each other and, therefore, that some of their traits could be the result of exogenous diffusion, not indigenous choice..The obvious solution to the paradox is to include unconscious diffusion and conscious imitation across units as potential explanatory variables – much as one should test for the spuriousness of any observed relationship. The major contemporary difference is the existence of multiple trans-national organizations – governmental and non-governmental – that are in the continuous business of promoting such exchanges at virtually all levels of society and the occasional existence of regional or global organizations that can back up these efforts with coercive authority or effective ‘conditionality.’

One of the repeated paradoxes of comparative politics is that scholars have a propensity for discovering and labeling novel phenomenon “at dusk, when the Owl of Minerva flies away,” i.e. at the very moment when the phenomenon is declining in importance or about to disappear. I suspect that this is because it is precisely institutions and practices that are in crisis that reveal themselves (and their internal workings) most clearly. Nevertheless, having been involved in “owl-chasing at dusk” several times, I can testify that it is a frustrating experience.

No one has insisted on this more consistently than Stanley Hoffmann ( 1982 ).

For a recent discussion of this trend, see Alexander Cooley and Jack Snyder ( 2015 ). For a criticism of this trend, see my “International Ratings and Rankings: Cure or Disease?” in the same volume.

Almond, Gabriel. 1990. A discipline divided. Schools and sects in political science . Newbury Park: Sage.

Google Scholar

Brady, Henry E., and David Collier. 2004. Rethinking social inquiry: diverse tools, shared standards . Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Cooley, Alexander, and Jack Snyder. 2015. Ranking the world . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Della Porta, Donatella, and Michael Keating. 2008. Approaches and methods in the social sciences. A pluralistic perspective . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

King, Gary, and O. Robert. 1994. Keohane and Sidney Verba, Designing Social Inquiry . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nye, Joseph, and Robert Keohane. 1989. Power and interdependence: world politics in transition , 2nd ed. Boston: Little Brown.

Stanley Hoffmann. 1982. Obstinate or obsolete: the fate of the nation-state and the case of Western Europe,” Daedalus, Vol. 95, 862–915.

Tilly, C. 1984. Big structures, large processes, huge comparisons . New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Political and Social Sciences, European University Institute, Badia Fiesolana, 50016, San Domenico di Fiesole, FI, Italy

Philippe C. Schmitter

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Philippe C. Schmitter .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Schmitter, P.C. Comparative Politics: its Past, Present and Future. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1 , 397–411 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0038-7

Download citation

Received : 03 March 2016

Accepted : 21 June 2016

Published : 15 July 2016

Issue Date : September 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0038-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Political science

- Comparative politics

- Conceptualization

- Complex interdependence

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse