Eat, Sleep, Wander

5 Examples of Problem Solving Scenarios + ROLE PLAY SCRIPTS

Problem-solving is an essential skill in our daily lives. It enables us to analyze situations, identify challenges, and find suitable solutions. In this article, we’ll explore five real-life problem-solving scenarios from various areas, including business, education, and personal growth. By understanding these examples, you can develop your problem-solving abilities and effectively tackle challenges in your life.

Examples of Problem Solving Scenarios

Improving Customer Service Scenario:

A retail store is experiencing a decline in customer satisfaction, with clients complaining about slow service and unhelpful staff.

Solution : The store manager assembles a team to analyze customer feedback, identify key issues, and propose solutions. They implement a new training program focused on customer service skills, streamline the checkout process, and introduce an incentive system to motivate employees. As a result, customer satisfaction improves, and the store’s reputation is restored.

Enhancing Learning Outcomes Scenario:

A high school teacher notices that her students struggle with understanding complex concepts in her science class, leading to poor performance on tests.

Solution : The teacher reevaluates her teaching methods and incorporates active learning strategies, such as group discussions, hands-on activities, and real-world examples, to make the material more engaging and relatable. She also offers additional support sessions and resources for students who need extra help. Consequently, students’ understanding improves, and test scores increase.

Overcoming Procrastination Scenario:

An individual consistently procrastinates, leading to increased stress and reduced productivity.

Solution : The person identifies the root cause of their procrastination, such as fear of failure or lack of motivation. They establish clear goals and deadlines, break tasks into manageable steps, and use time management tools, like the Pomodoro Technique , to stay focused. By consistently applying these strategies, they successfully overcome procrastination and enhance their productivity.

Reducing Patient Wait Times Scenario:

A medical clinic has long wait times, leading to patient dissatisfaction and overworked staff.

Solution : The clinic’s management team conducts a thorough analysis of the appointment scheduling process and identifies bottlenecks. They implement a new appointment system, hire additional staff, and optimize the workflow to reduce wait times. As a result, patient satisfaction increases, and staff stress levels decrease.

Reducing Plastic Waste Scenario:

A local community is struggling with an excessive amount of plastic waste, causing environmental pollution and health concerns.

Solution : Community leaders organize a task force to address the issue. They implement a recycling program, educate residents about the environmental impact of plastic waste, and collaborate with local businesses to promote the use of eco-friendly packaging alternatives. These actions lead to a significant reduction in plastic waste and a cleaner, healthier community.

Conclusion : These five examples of problem-solving scenarios demonstrate how effective problem-solving strategies can lead to successful outcomes in various aspects of life. By learning from these scenarios, you can develop your problem-solving skills and become better equipped to face challenges in your personal and professional life. Remember to analyze situations carefully, identify the root causes, and implement solutions that address these issues for optimal results.

- See also: 4 Medical Role Play Scenarios: Prepare for the Real Thing

- See also: 3 Financial Advisor Role Play Scenarios: Practice Your Skills!

- See also: 3 Insurance Role Play Examples

- See also: 3 Workplace Scenarios for Role Play

Role Play: Improving Customer Service in a Retail Store

Objective : To practice effective problem-solving and communication skills in a retail setting by addressing customer service issues and finding solutions to improve customer satisfaction.

Scenario : A retail store is experiencing a decline in customer satisfaction, with clients complaining about slow service and unhelpful staff.

Characters :

- Store Manager

- Sales Associate

- Assistant Manager

Role Play Script:

Scene 1 : Store Manager’s Office Store Manager: (Addressing the Assistant Manager and Sales Associate) I’ve noticed that our customer satisfaction has been declining lately. We’ve received several complaints about slow service and unhelpful staff. We need to address these issues immediately. Any suggestions?

Sales Associate : I’ve observed that the checkout process can be quite slow, especially during peak hours. Maybe we can improve our system to make it more efficient?

Assistant Manager : I agree. We could also implement a new training program for our staff, focusing on customer service skills and techniques.

Scene 2 : Staff Training Session Store Manager: (Addressing the entire staff) We’re implementing a new training program to improve our customer service. This program will cover effective communication, problem-solving, and time management skills. We’ll also introduce an incentive system to reward those who provide exceptional service.

Scene 3 : Retail Floor Customer: (Approaching the Sales Associate) Excuse me, I can’t find the product I’m looking for. Can you help me?

Sales Associate : (Smiling) Of course! I’d be happy to help. What product are you looking for?

Customer : I need a specific brand of shampoo, but I can’t find it on the shelves.

Sales Associate : Let me check our inventory system to see if we have it in stock. (Checks inventory) I’m sorry, but it seems we’re currently out of stock. However, we’re expecting a new shipment within two days. I can take your contact information and let you know as soon as it arrives.

Customer : That would be great! Thank you for your help.

Scene 4 : Store Manager’s Office Assistant Manager: (Reporting to the Store Manager) Since we implemented the new training program and made changes to the checkout process, we’ve seen a significant improvement in customer satisfaction.

Store Manager : That’s excellent news! Let’s continue to monitor our progress and make any necessary adjustments to ensure we maintain this positive trend.

More Examples of Problem Solving Scenarios on the next page…

10 Everyday uses for Problem Solving Skills

- Problem Solving & Decision Making Real world training delivers real world results. Learn More

Many employers are recognizing the value and placing significant investments in developing the problem solving skills of their employees. While we often think about these skills in the work context, problem solving isn’t just helpful in the workplace. Here are 10 everyday uses for problem solving skills that can you may not have thought about

1. Stuck in traffic and late for work, again

With busy schedules and competing demands for your time, getting where you need to be on time can be a real challenge. When traffic backs up, problem solving skills can help you figure out alternatives to avoid congestion, resolve the immediate situation and develop a solution to avoid encountering the situation in the future.

2. What is that stain on the living room carpet?

Parents, pet owners and spouses face this situation all the time. The living room carpet was clean yesterday but somehow a mysterious stain has appeared and nobody is claiming it. In order to clean it effectively, first you need to figure out what it is. Problem solving can help you track down the culprit, diagnose the cause of the stain and develop an action plan to get your home clean and fresh again.

3. What is that smell coming from my garden shed?

Drawing from past experiences, the seasoned problem solver in you suspects that the source of the peculiar odor likely lurks somewhere within the depths of the shed. Your challenge now lies in uncovering the origin of this scent, managing its effects, and formulating a practical plan to prevent such occurrences in the future.

4. I don’t think the car is supposed to make that thumping noise

As with many problems in the workplace, this may be a situation to bring in problem solving experts in the form of your trusted mechanic. If that isn’t an option, problem solving skills can be helpful to diagnose and assess the impact of the situation to ensure you can get where you need to be.

5. Creating a budget

Tap into your problem-solving prowess as you embark on the journey of budgeting. Begin by determining what expenses to include in your budget, and strategize how to account for unexpected financial surprises. The challenge lies in crafting a comprehensive budget that not only covers your known expenses but also prepares you for the uncertainties that may arise.

6. My daughter has a science project – due tomorrow

Sometimes the challenge isn’t impact, its urgency. Problem solving skills can help you quickly assess the situation and develop an action plan to get that science project done and turned in on time.

7. What should I get my spouse for his/her birthday?

As with many problems, this one may not have a “right answer” or apparent solution. Its time to apply those problem solving skills to evaluate the effects of past decisions combined with current environmental signals and available resources to select the perfect gift to put a smile on your significant other’s face.

8. The office printer suddenly stopped working, and there are important documents that need to be printed urgently.

Uh oh, time to think quickly. There is an urgent situation that must be addressed to get things back to normal, a cause to be identified (what’s causing the printer issue), and an action plan to resolve it. Problem solving skills can help you avoid stress and ensure that your documents are printed on time.

9. I’m torn between two cars! Which one should I choose?

In a world brimming with countless choices, employ decision analysis as your trusty tool to navigate the sea of options. Whether you’re selecting a car (or any other product), the challenge is to methodically identify and evaluate the best choices that align with your unique needs and preferences.

10. What’s for dinner?

Whether you are planning to eat alone, with family or entertaining friends and colleagues, meal planning can be a cause of daily stress. Applying problem solving skills can put the dinner dilemma into perspective and help get the food on the table and keep everyone happy.

Problem Solving skills aren’t just for the workplace – they can be applied in your everyday life. Kepner-Tregoe can help you and your team develop your problem solving skills through a combination of training and consulting with our problem solving experts.

We are experts in:

For inquiries, details, or a proposal!

Subscribe to the KT Newsletter

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

10 Problem-solving strategies to turn challenges on their head

Jump to section

What is an example of problem-solving?

What are the 5 steps to problem-solving, 10 effective problem-solving strategies, what skills do efficient problem solvers have, how to improve your problem-solving skills.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes — from workplace conflict to budget cuts.

Creative problem-solving is one of the most in-demand skills in all roles and industries. It can boost an organization’s human capital and give it a competitive edge.

Problem-solving strategies are ways of approaching problems that can help you look beyond the obvious answers and find the best solution to your problem .

Let’s take a look at a five-step problem-solving process and how to combine it with proven problem-solving strategies. This will give you the tools and skills to solve even your most complex problems.

Good problem-solving is an essential part of the decision-making process . To see what a problem-solving process might look like in real life, let’s take a common problem for SaaS brands — decreasing customer churn rates.

To solve this problem, the company must first identify it. In this case, the problem is that the churn rate is too high.

Next, they need to identify the root causes of the problem. This could be anything from their customer service experience to their email marketing campaigns. If there are several problems, they will need a separate problem-solving process for each one.

Let’s say the problem is with email marketing — they’re not nurturing existing customers. Now that they’ve identified the problem, they can start using problem-solving strategies to look for solutions.

This might look like coming up with special offers, discounts, or bonuses for existing customers. They need to find ways to remind them to use their products and services while providing added value. This will encourage customers to keep paying their monthly subscriptions.

They might also want to add incentives, such as access to a premium service at no extra cost after 12 months of membership. They could publish blog posts that help their customers solve common problems and share them as an email newsletter.

The company should set targets and a time frame in which to achieve them. This will allow leaders to measure progress and identify which actions yield the best results.

Perhaps you’ve got a problem you need to tackle. Or maybe you want to be prepared the next time one arises. Either way, it’s a good idea to get familiar with the five steps of problem-solving.

Use this step-by-step problem-solving method with the strategies in the following section to find possible solutions to your problem.

1. Identify the problem

The first step is to know which problem you need to solve. Then, you need to find the root cause of the problem.

The best course of action is to gather as much data as possible, speak to the people involved, and separate facts from opinions.

Once this is done, formulate a statement that describes the problem. Use rational persuasion to make sure your team agrees .

2. Break the problem down

Identifying the problem allows you to see which steps need to be taken to solve it.

First, break the problem down into achievable blocks. Then, use strategic planning to set a time frame in which to solve the problem and establish a timeline for the completion of each stage.

3. Generate potential solutions

At this stage, the aim isn’t to evaluate possible solutions but to generate as many ideas as possible.

Encourage your team to use creative thinking and be patient — the best solution may not be the first or most obvious one.

Use one or more of the different strategies in the following section to help come up with solutions — the more creative, the better.

4. Evaluate the possible solutions

Once you’ve generated potential solutions, narrow them down to a shortlist. Then, evaluate the options on your shortlist.

There are usually many factors to consider. So when evaluating a solution, ask yourself the following questions:

- Will my team be on board with the proposition?

- Does the solution align with organizational goals ?

- Is the solution likely to achieve the desired outcomes?

- Is the solution realistic and possible with current resources and constraints?

- Will the solution solve the problem without causing additional unintended problems?

5. Implement and monitor the solutions

Once you’ve identified your solution and got buy-in from your team, it’s time to implement it.

But the work doesn’t stop there. You need to monitor your solution to see whether it actually solves your problem.

Request regular feedback from the team members involved and have a monitoring and evaluation plan in place to measure progress.

If the solution doesn’t achieve your desired results, start this step-by-step process again.

There are many different ways to approach problem-solving. Each is suitable for different types of problems.

The most appropriate problem-solving techniques will depend on your specific problem. You may need to experiment with several strategies before you find a workable solution.

Here are 10 effective problem-solving strategies for you to try:

- Use a solution that worked before

- Brainstorming

- Work backward

- Use the Kipling method

- Draw the problem

- Use trial and error

- Sleep on it

- Get advice from your peers

- Use the Pareto principle

- Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Let’s break each of these down.

1. Use a solution that worked before

It might seem obvious, but if you’ve faced similar problems in the past, look back to what worked then. See if any of the solutions could apply to your current situation and, if so, replicate them.

2. Brainstorming

The more people you enlist to help solve the problem, the more potential solutions you can come up with.

Use different brainstorming techniques to workshop potential solutions with your team. They’ll likely bring something you haven’t thought of to the table.

3. Work backward

Working backward is a way to reverse engineer your problem. Imagine your problem has been solved, and make that the starting point.

Then, retrace your steps back to where you are now. This can help you see which course of action may be most effective.

4. Use the Kipling method

This is a method that poses six questions based on Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “ I Keep Six Honest Serving Men .”

- What is the problem?

- Why is the problem important?

- When did the problem arise, and when does it need to be solved?

- How did the problem happen?

- Where is the problem occurring?

- Who does the problem affect?

Answering these questions can help you identify possible solutions.

5. Draw the problem

Sometimes it can be difficult to visualize all the components and moving parts of a problem and its solution. Drawing a diagram can help.

This technique is particularly helpful for solving process-related problems. For example, a product development team might want to decrease the time they take to fix bugs and create new iterations. Drawing the processes involved can help you see where improvements can be made.

6. Use trial-and-error

A trial-and-error approach can be useful when you have several possible solutions and want to test them to see which one works best.

7. Sleep on it

Finding the best solution to a problem is a process. Remember to take breaks and get enough rest . Sometimes, a walk around the block can bring inspiration, but you should sleep on it if possible.

A good night’s sleep helps us find creative solutions to problems. This is because when you sleep, your brain sorts through the day’s events and stores them as memories. This enables you to process your ideas at a subconscious level.

If possible, give yourself a few days to develop and analyze possible solutions. You may find you have greater clarity after sleeping on it. Your mind will also be fresh, so you’ll be able to make better decisions.

8. Get advice from your peers

Getting input from a group of people can help you find solutions you may not have thought of on your own.

For solo entrepreneurs or freelancers, this might look like hiring a coach or mentor or joining a mastermind group.

For leaders , it might be consulting other members of the leadership team or working with a business coach .

It’s important to recognize you might not have all the skills, experience, or knowledge necessary to find a solution alone.

9. Use the Pareto principle

The Pareto principle — also known as the 80/20 rule — can help you identify possible root causes and potential solutions for your problems.

Although it’s not a mathematical law, it’s a principle found throughout many aspects of business and life. For example, 20% of the sales reps in a company might close 80% of the sales.

You may be able to narrow down the causes of your problem by applying the Pareto principle. This can also help you identify the most appropriate solutions.

10. Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Every situation is different, and the same solutions might not always work. But by keeping a record of successful problem-solving strategies, you can build up a solutions toolkit.

These solutions may be applicable to future problems. Even if not, they may save you some of the time and work needed to come up with a new solution.

Improving problem-solving skills is essential for professional development — both yours and your team’s. Here are some of the key skills of effective problem solvers:

- Critical thinking and analytical skills

- Communication skills , including active listening

- Decision-making

- Planning and prioritization

- Emotional intelligence , including empathy and emotional regulation

- Time management

- Data analysis

- Research skills

- Project management

And they see problems as opportunities. Everyone is born with problem-solving skills. But accessing these abilities depends on how we view problems. Effective problem-solvers see problems as opportunities to learn and improve.

Ready to work on your problem-solving abilities? Get started with these seven tips.

1. Build your problem-solving skills

One of the best ways to improve your problem-solving skills is to learn from experts. Consider enrolling in organizational training , shadowing a mentor , or working with a coach .

2. Practice

Practice using your new problem-solving skills by applying them to smaller problems you might encounter in your daily life.

Alternatively, imagine problematic scenarios that might arise at work and use problem-solving strategies to find hypothetical solutions.

3. Don’t try to find a solution right away

Often, the first solution you think of to solve a problem isn’t the most appropriate or effective.

Instead of thinking on the spot, give yourself time and use one or more of the problem-solving strategies above to activate your creative thinking.

4. Ask for feedback

Receiving feedback is always important for learning and growth. Your perception of your problem-solving skills may be different from that of your colleagues. They can provide insights that help you improve.

5. Learn new approaches and methodologies

There are entire books written about problem-solving methodologies if you want to take a deep dive into the subject.

We recommend starting with “ Fixed — How to Perfect the Fine Art of Problem Solving ” by Amy E. Herman.

6. Experiment

Tried-and-tested problem-solving techniques can be useful. However, they don’t teach you how to innovate and develop your own problem-solving approaches.

Sometimes, an unconventional approach can lead to the development of a brilliant new idea or strategy. So don’t be afraid to suggest your most “out there” ideas.

7. Analyze the success of your competitors

Do you have competitors who have already solved the problem you’re facing? Look at what they did, and work backward to solve your own problem.

For example, Netflix started in the 1990s as a DVD mail-rental company. Its main competitor at the time was Blockbuster.

But when streaming became the norm in the early 2000s, both companies faced a crisis. Netflix innovated, unveiling its streaming service in 2007.

If Blockbuster had followed Netflix’s example, it might have survived. Instead, it declared bankruptcy in 2010.

Use problem-solving strategies to uplevel your business

When facing a problem, it’s worth taking the time to find the right solution.

Otherwise, we risk either running away from our problems or headlong into solutions. When we do this, we might miss out on other, better options.

Use the problem-solving strategies outlined above to find innovative solutions to your business’ most perplexing problems.

If you’re ready to take problem-solving to the next level, request a demo with BetterUp . Our expert coaches specialize in helping teams develop and implement strategies that work.

Boost your productivity

Maximize your time and productivity with strategies from our expert coaches.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

8 creative solutions to your most challenging problems

5 problem-solving questions to prepare you for your next interview, what are metacognitive skills examples in everyday life, 31 examples of problem solving performance review phrases, what is lateral thinking 7 techniques to encourage creative ideas, leadership activities that encourage employee engagement, learn what process mapping is and how to create one (+ examples), how much do distractions cost 8 effects of lack of focus, can dreams help you solve problems 6 ways to try, similar articles, the pareto principle: how the 80/20 rule can help you do more with less, thinking outside the box: 8 ways to become a creative problem solver, experimentation brings innovation: create an experimental workplace, effective problem statements have these 5 components, contingency planning: 4 steps to prepare for the unexpected, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

10 Best Problem-Solving Therapy Worksheets & Activities

Cognitive science tells us that we regularly face not only well-defined problems but, importantly, many that are ill defined (Eysenck & Keane, 2015).

Sometimes, we find ourselves unable to overcome our daily problems or the inevitable (though hopefully infrequent) life traumas we face.

Problem-Solving Therapy aims to reduce the incidence and impact of mental health disorders and improve wellbeing by helping clients face life’s difficulties (Dobson, 2011).

This article introduces Problem-Solving Therapy and offers techniques, activities, and worksheets that mental health professionals can use with clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is problem-solving therapy, 14 steps for problem-solving therapy, 3 best interventions and techniques, 7 activities and worksheets for your session, fascinating books on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Problem-Solving Therapy assumes that mental disorders arise in response to ineffective or maladaptive coping. By adopting a more realistic and optimistic view of coping, individuals can understand the role of emotions and develop actions to reduce distress and maintain mental wellbeing (Nezu & Nezu, 2009).

“Problem-solving therapy (PST) is a psychosocial intervention, generally considered to be under a cognitive-behavioral umbrella” (Nezu, Nezu, & D’Zurilla, 2013, p. ix). It aims to encourage the client to cope better with day-to-day problems and traumatic events and reduce their impact on mental and physical wellbeing.

Clinical research, counseling, and health psychology have shown PST to be highly effective in clients of all ages, ranging from children to the elderly, across multiple clinical settings, including schizophrenia, stress, and anxiety disorders (Dobson, 2011).

Can it help with depression?

PST appears particularly helpful in treating clients with depression. A recent analysis of 30 studies found that PST was an effective treatment with a similar degree of success as other successful therapies targeting depression (Cuijpers, Wit, Kleiboer, Karyotaki, & Ebert, 2020).

Other studies confirm the value of PST and its effectiveness at treating depression in multiple age groups and its capacity to combine with other therapies, including drug treatments (Dobson, 2011).

The major concepts

Effective coping varies depending on the situation, and treatment typically focuses on improving the environment and reducing emotional distress (Dobson, 2011).

PST is based on two overlapping models:

Social problem-solving model

This model focuses on solving the problem “as it occurs in the natural social environment,” combined with a general coping strategy and a method of self-control (Dobson, 2011, p. 198).

The model includes three central concepts:

- Social problem-solving

- The problem

- The solution

The model is a “self-directed cognitive-behavioral process by which an individual, couple, or group attempts to identify or discover effective solutions for specific problems encountered in everyday living” (Dobson, 2011, p. 199).

Relational problem-solving model

The theory of PST is underpinned by a relational problem-solving model, whereby stress is viewed in terms of the relationships between three factors:

- Stressful life events

- Emotional distress and wellbeing

- Problem-solving coping

Therefore, when a significant adverse life event occurs, it may require “sweeping readjustments in a person’s life” (Dobson, 2011, p. 202).

- Enhance positive problem orientation

- Decrease negative orientation

- Foster ability to apply rational problem-solving skills

- Reduce the tendency to avoid problem-solving

- Minimize the tendency to be careless and impulsive

D’Zurilla’s and Nezu’s model includes (modified from Dobson, 2011):

- Initial structuring Establish a positive therapeutic relationship that encourages optimism and explains the PST approach.

- Assessment Formally and informally assess areas of stress in the client’s life and their problem-solving strengths and weaknesses.

- Obstacles to effective problem-solving Explore typically human challenges to problem-solving, such as multitasking and the negative impact of stress. Introduce tools that can help, such as making lists, visualization, and breaking complex problems down.

- Problem orientation – fostering self-efficacy Introduce the importance of a positive problem orientation, adopting tools, such as visualization, to promote self-efficacy.

- Problem orientation – recognizing problems Help clients recognize issues as they occur and use problem checklists to ‘normalize’ the experience.

- Problem orientation – seeing problems as challenges Encourage clients to break free of harmful and restricted ways of thinking while learning how to argue from another point of view.

- Problem orientation – use and control emotions Help clients understand the role of emotions in problem-solving, including using feelings to inform the process and managing disruptive emotions (such as cognitive reframing and relaxation exercises).

- Problem orientation – stop and think Teach clients how to reduce impulsive and avoidance tendencies (visualizing a stop sign or traffic light).

- Problem definition and formulation Encourage an understanding of the nature of problems and set realistic goals and objectives.

- Generation of alternatives Work with clients to help them recognize the wide range of potential solutions to each problem (for example, brainstorming).

- Decision-making Encourage better decision-making through an improved understanding of the consequences of decisions and the value and likelihood of different outcomes.

- Solution implementation and verification Foster the client’s ability to carry out a solution plan, monitor its outcome, evaluate its effectiveness, and use self-reinforcement to increase the chance of success.

- Guided practice Encourage the application of problem-solving skills across multiple domains and future stressful problems.

- Rapid problem-solving Teach clients how to apply problem-solving questions and guidelines quickly in any given situation.

Success in PST depends on the effectiveness of its implementation; using the right approach is crucial (Dobson, 2011).

Problem-solving therapy – Baycrest

The following interventions and techniques are helpful when implementing more effective problem-solving approaches in client’s lives.

First, it is essential to consider if PST is the best approach for the client, based on the problems they present.

Is PPT appropriate?

It is vital to consider whether PST is appropriate for the client’s situation. Therapists new to the approach may require additional guidance (Nezu et al., 2013).

Therapists should consider the following questions before beginning PST with a client (modified from Nezu et al., 2013):

- Has PST proven effective in the past for the problem? For example, research has shown success with depression, generalized anxiety, back pain, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and supporting caregivers (Nezu et al., 2013).

- Is PST acceptable to the client?

- Is the individual experiencing a significant mental or physical health problem?

All affirmative answers suggest that PST would be a helpful technique to apply in this instance.

Five problem-solving steps

The following five steps are valuable when working with clients to help them cope with and manage their environment (modified from Dobson, 2011).

Ask the client to consider the following points (forming the acronym ADAPT) when confronted by a problem:

- Attitude Aim to adopt a positive, optimistic attitude to the problem and problem-solving process.

- Define Obtain all required facts and details of potential obstacles to define the problem.

- Alternatives Identify various alternative solutions and actions to overcome the obstacle and achieve the problem-solving goal.

- Predict Predict each alternative’s positive and negative outcomes and choose the one most likely to achieve the goal and maximize the benefits.

- Try out Once selected, try out the solution and monitor its effectiveness while engaging in self-reinforcement.

If the client is not satisfied with their solution, they can return to step ‘A’ and find a more appropriate solution.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Positive self-statements

When dealing with clients facing negative self-beliefs, it can be helpful for them to use positive self-statements.

Use the following (or add new) self-statements to replace harmful, negative thinking (modified from Dobson, 2011):

- I can solve this problem; I’ve tackled similar ones before.

- I can cope with this.

- I just need to take a breath and relax.

- Once I start, it will be easier.

- It’s okay to look out for myself.

- I can get help if needed.

- Other people feel the same way I do.

- I’ll take one piece of the problem at a time.

- I can keep my fears in check.

- I don’t need to please everyone.

5 Worksheets and workbooks

Problem-solving self-monitoring form.

Answering the questions in the Problem-Solving Self-Monitoring Form provides the therapist with necessary information regarding the client’s overall and specific problem-solving approaches and reactions (Dobson, 2011).

Ask the client to complete the following:

- Describe the problem you are facing.

- What is your goal?

- What have you tried so far to solve the problem?

- What was the outcome?

Reactions to Stress

It can be helpful for the client to recognize their own experiences of stress. Do they react angrily, withdraw, or give up (Dobson, 2011)?

The Reactions to Stress worksheet can be given to the client as homework to capture stressful events and their reactions. By recording how they felt, behaved, and thought, they can recognize repeating patterns.

What Are Your Unique Triggers?

Helping clients capture triggers for their stressful reactions can encourage emotional regulation.

When clients can identify triggers that may lead to a negative response, they can stop the experience or slow down their emotional reaction (Dobson, 2011).

The What Are Your Unique Triggers ? worksheet helps the client identify their triggers (e.g., conflict, relationships, physical environment, etc.).

Problem-Solving worksheet

Imagining an existing or potential problem and working through how to resolve it can be a powerful exercise for the client.

Use the Problem-Solving worksheet to state a problem and goal and consider the obstacles in the way. Then explore options for achieving the goal, along with their pros and cons, to assess the best action plan.

Getting the Facts

Clients can become better equipped to tackle problems and choose the right course of action by recognizing facts versus assumptions and gathering all the necessary information (Dobson, 2011).

Use the Getting the Facts worksheet to answer the following questions clearly and unambiguously:

- Who is involved?

- What did or did not happen, and how did it bother you?

- Where did it happen?

- When did it happen?

- Why did it happen?

- How did you respond?

2 Helpful Group Activities

While therapists can use the worksheets above in group situations, the following two interventions work particularly well with more than one person.

Generating Alternative Solutions and Better Decision-Making

A group setting can provide an ideal opportunity to share a problem and identify potential solutions arising from multiple perspectives.

Use the Generating Alternative Solutions and Better Decision-Making worksheet and ask the client to explain the situation or problem to the group and the obstacles in the way.

Once the approaches are captured and reviewed, the individual can share their decision-making process with the group if they want further feedback.

Visualization

Visualization can be performed with individuals or in a group setting to help clients solve problems in multiple ways, including (Dobson, 2011):

- Clarifying the problem by looking at it from multiple perspectives

- Rehearsing a solution in the mind to improve and get more practice

- Visualizing a ‘safe place’ for relaxation, slowing down, and stress management

Guided imagery is particularly valuable for encouraging the group to take a ‘mental vacation’ and let go of stress.

Ask the group to begin with slow, deep breathing that fills the entire diaphragm. Then ask them to visualize a favorite scene (real or imagined) that makes them feel relaxed, perhaps beside a gently flowing river, a summer meadow, or at the beach.

The more the senses are engaged, the more real the experience. Ask the group to think about what they can hear, see, touch, smell, and even taste.

Encourage them to experience the situation as fully as possible, immersing themselves and enjoying their place of safety.

Such feelings of relaxation may be able to help clients fall asleep, relieve stress, and become more ready to solve problems.

We have included three of our favorite books on the subject of Problem-Solving Therapy below.

1. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual – Arthur Nezu, Christine Maguth Nezu, and Thomas D’Zurilla

This is an incredibly valuable book for anyone wishing to understand the principles and practice behind PST.

Written by the co-developers of PST, the manual provides powerful toolkits to overcome cognitive overload, emotional dysregulation, and the barriers to practical problem-solving.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Emotion-Centered Problem-Solving Therapy: Treatment Guidelines – Arthur Nezu and Christine Maguth Nezu

Another, more recent, book from the creators of PST, this text includes important advances in neuroscience underpinning the role of emotion in behavioral treatment.

Along with clinical examples, the book also includes crucial toolkits that form part of a stepped model for the application of PST.

3. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies – Keith Dobson and David Dozois

This is the fourth edition of a hugely popular guide to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies and includes a valuable and insightful section on Problem-Solving Therapy.

This is an important book for students and more experienced therapists wishing to form a high-level and in-depth understanding of the tools and techniques available to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists.

For even more tools to help strengthen your clients’ problem-solving skills, check out the following free worksheets from our blog.

- Case Formulation Worksheet This worksheet presents a four-step framework to help therapists and their clients come to a shared understanding of the client’s presenting problem.

- Understanding Your Default Problem-Solving Approach This worksheet poses a series of questions helping clients reflect on their typical cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to problems.

- Social Problem Solving: Step by Step This worksheet presents a streamlined template to help clients define a problem, generate possible courses of action, and evaluate the effectiveness of an implemented solution.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, check out this signature collection of 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

While we are born problem-solvers, facing an incredibly diverse set of challenges daily, we sometimes need support.

Problem-Solving Therapy aims to reduce stress and associated mental health disorders and improve wellbeing by improving our ability to cope. PST is valuable in diverse clinical settings, ranging from depression to schizophrenia, with research suggesting it as a highly effective treatment for teaching coping strategies and reducing emotional distress.

Many PST techniques are available to help improve clients’ positive outlook on obstacles while reducing avoidance of problem situations and the tendency to be careless and impulsive.

The PST model typically assesses the client’s strengths, weaknesses, and coping strategies when facing problems before encouraging a healthy experience of and relationship with problem-solving.

Why not use this article to explore the theory behind PST and try out some of our powerful tools and interventions with your clients to help them with their decision-making, coping, and problem-solving?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Cuijpers, P., Wit, L., Kleiboer, A., Karyotaki, E., & Ebert, D. (2020). Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis. European P sychiatry , 48 (1), 27–37.

- Dobson, K. S. (2011). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Dobson, K. S., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2021). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Eysenck, M. W., & Keane, M. T. (2015). Cognitive psychology: A student’s handbook . Psychology Press.

- Nezu, A. M., & Nezu, C. M. (2009). Problem-solving therapy DVD . Retrieved September 13, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/pubs/videos/4310852

- Nezu, A. M., & Nezu, C. M. (2018). Emotion-centered problem-solving therapy: Treatment guidelines. Springer.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-solving therapy: A treatment manual . Springer.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thanks for your information given, it was helpful for me something new I learned

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Empty Chair Technique: How It Can Help Your Clients

Resolving ‘unfinished business’ is often an essential part of counseling. If left unresolved, it can contribute to depression, anxiety, and mental ill-health while damaging existing [...]

29 Best Group Therapy Activities for Supporting Adults

As humans, we are social creatures with personal histories based on the various groups that make up our lives. Childhood begins with a family of [...]

47 Free Therapy Resources to Help Kick-Start Your New Practice

Setting up a private practice in psychotherapy brings several challenges, including a considerable investment of time and money. You can reduce risks early on by [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

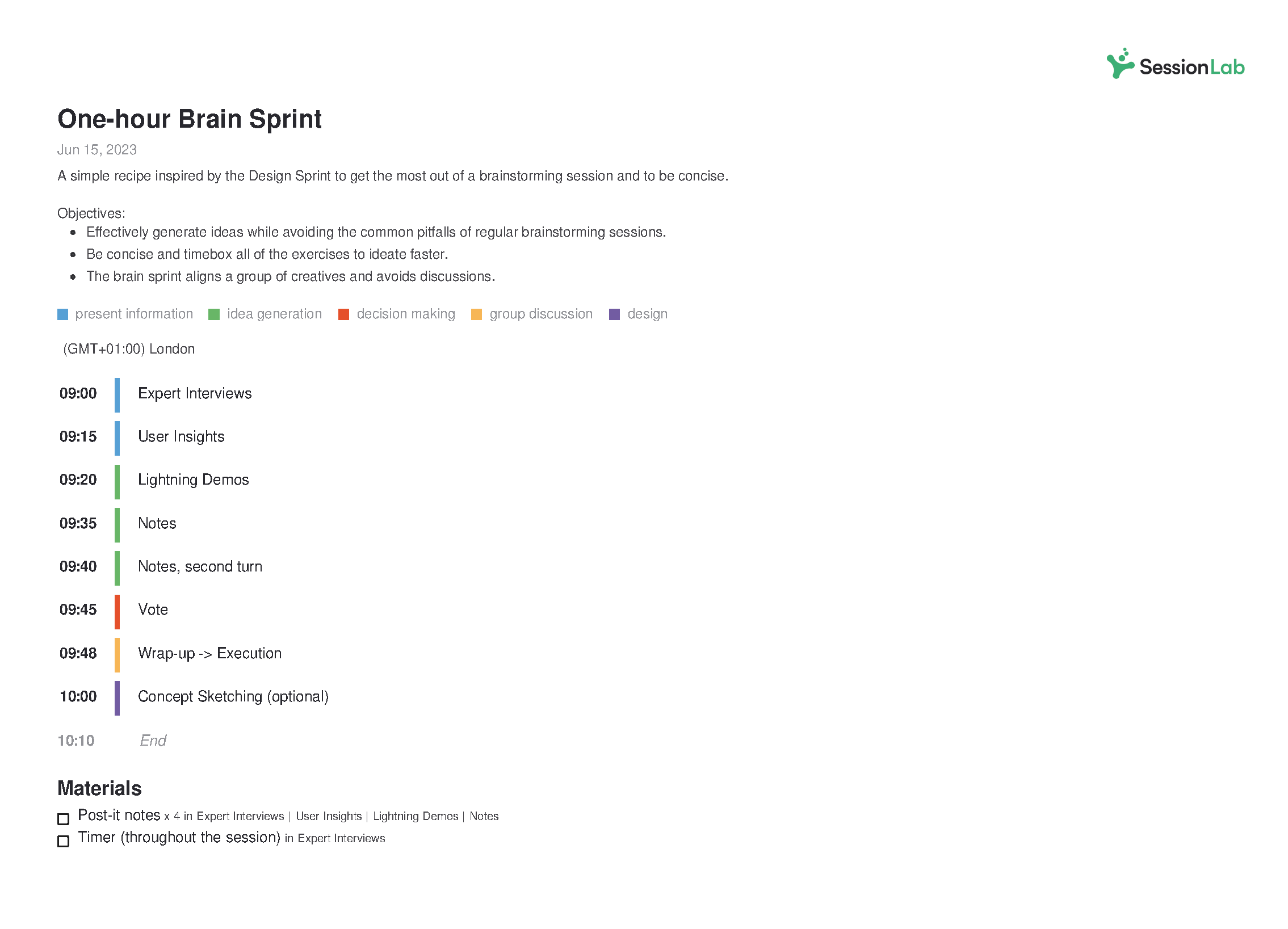

35 problem-solving techniques and methods for solving complex problems

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

All teams and organizations encounter challenges as they grow. There are problems that might occur for teams when it comes to miscommunication or resolving business-critical issues . You may face challenges around growth , design , user engagement, and even team culture and happiness. In short, problem-solving techniques should be part of every team’s skillset.

Problem-solving methods are primarily designed to help a group or team through a process of first identifying problems and challenges , ideating possible solutions , and then evaluating the most suitable .

Finding effective solutions to complex problems isn’t easy, but by using the right process and techniques, you can help your team be more efficient in the process.

So how do you develop strategies that are engaging, and empower your team to solve problems effectively?

In this blog post, we share a series of problem-solving tools you can use in your next workshop or team meeting. You’ll also find some tips for facilitating the process and how to enable others to solve complex problems.

Let’s get started!

How do you identify problems?

How do you identify the right solution.

- Tips for more effective problem-solving

Complete problem-solving methods

- Problem-solving techniques to identify and analyze problems

- Problem-solving techniques for developing solutions

Problem-solving warm-up activities

Closing activities for a problem-solving process.

Before you can move towards finding the right solution for a given problem, you first need to identify and define the problem you wish to solve.

Here, you want to clearly articulate what the problem is and allow your group to do the same. Remember that everyone in a group is likely to have differing perspectives and alignment is necessary in order to help the group move forward.

Identifying a problem accurately also requires that all members of a group are able to contribute their views in an open and safe manner. It can be scary for people to stand up and contribute, especially if the problems or challenges are emotive or personal in nature. Be sure to try and create a psychologically safe space for these kinds of discussions.

Remember that problem analysis and further discussion are also important. Not taking the time to fully analyze and discuss a challenge can result in the development of solutions that are not fit for purpose or do not address the underlying issue.

Successfully identifying and then analyzing a problem means facilitating a group through activities designed to help them clearly and honestly articulate their thoughts and produce usable insight.

With this data, you might then produce a problem statement that clearly describes the problem you wish to be addressed and also state the goal of any process you undertake to tackle this issue.

Finding solutions is the end goal of any process. Complex organizational challenges can only be solved with an appropriate solution but discovering them requires using the right problem-solving tool.

After you’ve explored a problem and discussed ideas, you need to help a team discuss and choose the right solution. Consensus tools and methods such as those below help a group explore possible solutions before then voting for the best. They’re a great way to tap into the collective intelligence of the group for great results!

Remember that the process is often iterative. Great problem solvers often roadtest a viable solution in a measured way to see what works too. While you might not get the right solution on your first try, the methods below help teams land on the most likely to succeed solution while also holding space for improvement.

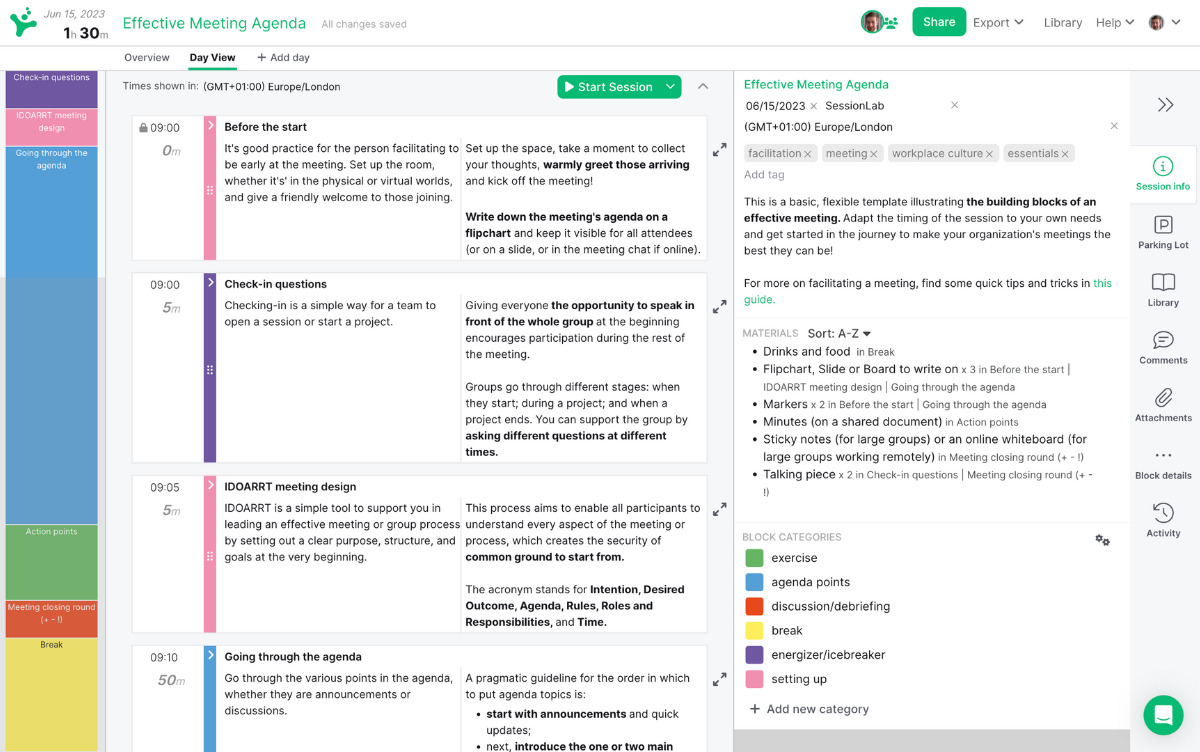

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . A well-structured workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

In SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Tips for more effective problem solving

Problem-solving activities are only one part of the puzzle. While a great method can help unlock your team’s ability to solve problems, without a thoughtful approach and strong facilitation the solutions may not be fit for purpose.

Let’s take a look at some problem-solving tips you can apply to any process to help it be a success!

Clearly define the problem

Jumping straight to solutions can be tempting, though without first clearly articulating a problem, the solution might not be the right one. Many of the problem-solving activities below include sections where the problem is explored and clearly defined before moving on.

This is a vital part of the problem-solving process and taking the time to fully define an issue can save time and effort later. A clear definition helps identify irrelevant information and it also ensures that your team sets off on the right track.

Don’t jump to conclusions

It’s easy for groups to exhibit cognitive bias or have preconceived ideas about both problems and potential solutions. Be sure to back up any problem statements or potential solutions with facts, research, and adequate forethought.

The best techniques ask participants to be methodical and challenge preconceived notions. Make sure you give the group enough time and space to collect relevant information and consider the problem in a new way. By approaching the process with a clear, rational mindset, you’ll often find that better solutions are more forthcoming.

Try different approaches

Problems come in all shapes and sizes and so too should the methods you use to solve them. If you find that one approach isn’t yielding results and your team isn’t finding different solutions, try mixing it up. You’ll be surprised at how using a new creative activity can unblock your team and generate great solutions.

Don’t take it personally

Depending on the nature of your team or organizational problems, it’s easy for conversations to get heated. While it’s good for participants to be engaged in the discussions, ensure that emotions don’t run too high and that blame isn’t thrown around while finding solutions.

You’re all in it together, and even if your team or area is seeing problems, that isn’t necessarily a disparagement of you personally. Using facilitation skills to manage group dynamics is one effective method of helping conversations be more constructive.

Get the right people in the room

Your problem-solving method is often only as effective as the group using it. Getting the right people on the job and managing the number of people present is important too!

If the group is too small, you may not get enough different perspectives to effectively solve a problem. If the group is too large, you can go round and round during the ideation stages.

Creating the right group makeup is also important in ensuring you have the necessary expertise and skillset to both identify and follow up on potential solutions. Carefully consider who to include at each stage to help ensure your problem-solving method is followed and positioned for success.

Document everything

The best solutions can take refinement, iteration, and reflection to come out. Get into a habit of documenting your process in order to keep all the learnings from the session and to allow ideas to mature and develop. Many of the methods below involve the creation of documents or shared resources. Be sure to keep and share these so everyone can benefit from the work done!

Bring a facilitator

Facilitation is all about making group processes easier. With a subject as potentially emotive and important as problem-solving, having an impartial third party in the form of a facilitator can make all the difference in finding great solutions and keeping the process moving. Consider bringing a facilitator to your problem-solving session to get better results and generate meaningful solutions!

Develop your problem-solving skills

It takes time and practice to be an effective problem solver. While some roles or participants might more naturally gravitate towards problem-solving, it can take development and planning to help everyone create better solutions.

You might develop a training program, run a problem-solving workshop or simply ask your team to practice using the techniques below. Check out our post on problem-solving skills to see how you and your group can develop the right mental process and be more resilient to issues too!

Design a great agenda

Workshops are a great format for solving problems. With the right approach, you can focus a group and help them find the solutions to their own problems. But designing a process can be time-consuming and finding the right activities can be difficult.

Check out our workshop planning guide to level-up your agenda design and start running more effective workshops. Need inspiration? Check out templates designed by expert facilitators to help you kickstart your process!

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

- Six Thinking Hats

- Lightning Decision Jam

- Problem Definition Process

- Discovery & Action Dialogue

Design Sprint 2.0

- Open Space Technology

1. Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

2. Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly The problem with anything that requires creative thinking is that it’s easy to get lost—lose focus and fall into the trap of having useless, open-ended, unstructured discussions. Here’s the most effective solution I’ve found: Replace all open, unstructured discussion with a clear process. What to use this exercise for: Anything which requires a group of people to make decisions, solve problems or discuss challenges. It’s always good to frame an LDJ session with a broad topic, here are some examples: The conversion flow of our checkout Our internal design process How we organise events Keeping up with our competition Improving sales flow

3. Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

4. The 5 Whys

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

5. World Cafe

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

6. Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

7. Design Sprint 2.0

Want to see how a team can solve big problems and move forward with prototyping and testing solutions in a few days? The Design Sprint 2.0 template from Jake Knapp, author of Sprint, is a complete agenda for a with proven results.

Developing the right agenda can involve difficult but necessary planning. Ensuring all the correct steps are followed can also be stressful or time-consuming depending on your level of experience.

Use this complete 4-day workshop template if you are finding there is no obvious solution to your challenge and want to focus your team around a specific problem that might require a shortcut to launching a minimum viable product or waiting for the organization-wide implementation of a solution.

8. Open space technology