Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Key Points |

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

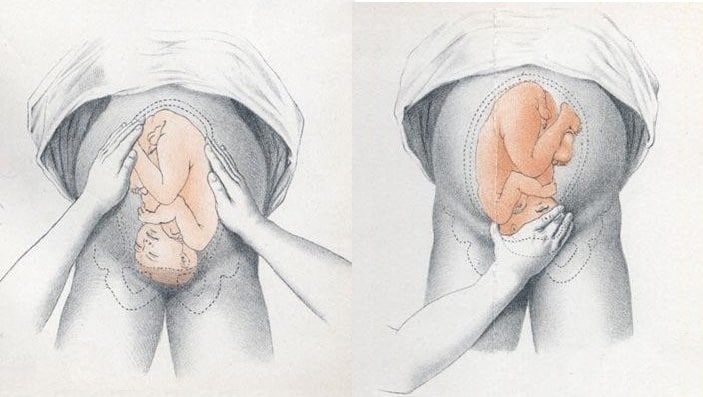

There are several types of breech presentation.

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Delivery, face and brow presentation.

Julija Makajeva ; Mohsina Ashraf .

Affiliations

Last Update: January 9, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Face and brow presentation is a malpresentation during labor when the presenting part is either the face or, in the case of brow presentation, it is the area between the orbital ridge and the anterior fontanelle. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of these two presentations and explains the role of the interprofessional team in managing delivery safely for both the mother and the baby.

- Describe the mechanism of labor in the face and brow presentation.

- Summarize potential maternal and fetal complications during the face and brow presentations.

- Review different management approaches for the face and brow presentation.

- Outline some interprofessional strategies that will improve patient outcomes in delivery cases with face and brow presentation issues.

- Introduction

The term presentation describes the leading part of the fetus or the anatomical structure closest to the maternal pelvic inlet during labor. The presentation can roughly be divided into the following classifications: cephalic, breech, shoulder, and compound. Cephalic presentation is the most common and can be further subclassified as vertex, sinciput, brow, face, and chin. The most common presentation in term labor is the vertex, where the fetal neck is flexed to the chin, minimizing the head circumference.

Face presentation – an abnormal form of cephalic presentation where the presenting part is mentum. This typically occurs because of hyperextension of the neck and the occiput touching the fetal back. Incidence of face presentation is rare, accounting for approximately 1 in 600 of all presentations. [1] [2] [3]

In brow presentation, the neck is not extended as much as in face presentation, and the leading part is the area between the anterior fontanelle and the orbital ridges. Brow presentation is considered the rarest of all malpresentation with a prevalence of 1 in 500 to 1 in 4000 deliveries. [3]

Both face and brow presentations occur due to extension of the fetal neck instead of flexion; therefore, conditions that would lead to hyperextension or prevent flexion of the fetal neck can all contribute to face or brow presentation. These risk factors may be related to either the mother or the fetus. Maternal risk factors are preterm delivery, contracted maternal pelvis, platypelloid pelvis, multiparity, previous cesarean section, black race. Fetal risk factors include anencephaly, multiple loops of cord around the neck, masses of the neck, macrosomia, polyhydramnios. [2] [4] [5]

These malpresentations are usually diagnosed during the second stage of labor when performing a digital examination. It is possible to palpate orbital ridges, nose, malar eminences, mentum, mouth, gums, and chin in face presentation. Based on the position of the chin, face presentation can be further divided into mentum anterior, posterior, or transverse. In brow presentation, anterior fontanelle and face can be palpated except for the mouth and the chin. Brow presentation can then be further described based on the position of the anterior fontanelle as frontal anterior, posterior, or transverse.

Diagnosing the exact presentation can be challenging, and face presentation may be misdiagnosed as frank breech. To avoid any confusion, a bedside ultrasound scan can be performed. [6] The ultrasound imaging can show a reduced angle between the occiput and the spine or, the chin is separated from the chest. However, ultrasound does not provide much predicting value in the outcome of the labor. [7]

- Anatomy and Physiology

Before discussing the mechanism of labor in the face or brow presentation, it is crucial to highlight some anatomical landmarks and their measurements.

Planes and Diameters of the Pelvis

The three most important planes in the female pelvis are the pelvic inlet, mid pelvis, and pelvic outlet.

Four diameters can describe the pelvic inlet: anteroposterior, transverse, and two obliques. Furthermore, based on the different landmarks on the pelvic inlet, there are three different anteroposterior diameters, named conjugates: true conjugate, obstetrical conjugate, and diagonal conjugate. Only the latter can be measured directly during the obstetric examination. The shortest of these three diameters is obstetrical conjugate, which measures approximately 10.5 cm and is a distance between the sacral promontory and 1 cm below the upper border of the symphysis pubis. This measurement is clinically significant as the fetal head must pass through this diameter during the engagement phase. The transverse diameter measures about 13.5cm and is the widest distance between the innominate line on both sides.

The shortest distance in the mid pelvis is the interspinous diameter and usually is only about 10 cm.

Fetal Skull Diameters

There are six distinguished longitudinal fetal skull diameters:

- Suboccipito-bregmatic: from the center of anterior fontanelle (bregma) to the occipital protuberance, measuring 9.5 cm. This is the presenting diameter in vertex presentation.

- Suboccipito-frontal: from the anterior part of bregma to the occipital protuberance, measuring 10 cm

- Occipito-frontal: from the root of the nose to the most prominent part of the occiput, measuring 11.5cm

- Submento-bregmatic: from the center of the bregma to the angle of the mandible, measuring 9.5 cm. This is the presenting diameter in face presentation where the neck is hyperextended.

- Submento-vertical: from the midpoint between fontanelles and the angle of the mandible, measuring 11.5cm

- Occipito-mental: from the midpoint between fontanelles and the tip of the chin, measuring 13.5 cm. It is the presenting diameter in brow presentation.

Cardinal Movements of Normal Labor

- Neck flexion

- Internal rotation

- Extension (delivers head)

- External rotation (Restitution)

- Expulsion (delivery of anterior and posterior shoulders)

Some of the key movements are not possible in the face or brow presentations.

Based on the information provided above, it is obvious that labor will be arrested in brow presentation unless it spontaneously changes to face or vertex, as the occipito-mental diameter of the fetal head is significantly wider than the smallest diameter of the female pelvis. Face presentation can, however, be delivered vaginally, and further mechanisms of face delivery will be explained in later sections.

- Indications

As mentioned previously, spontaneous vaginal delivery can be successful in face presentation. However, the main indication for vaginal delivery in such circumstances would be a maternal choice. It is crucial to have a thorough conversation with a mother, explaining the risks and benefits of vaginal delivery with face presentation and a cesarean section. Informed consent and creating a rapport with the mother is an essential aspect of safe and successful labor.

- Contraindications

Vaginal delivery of face presentation is contraindicated if the mentum is lying posteriorly or is in a transverse position. In such a scenario, the fetal brow is pressing against the maternal symphysis pubis, and the short fetal neck, which is already maximally extended, cannot span the surface of the maternal sacrum. In this position, the diameter of the head is larger than the maternal pelvis, and it cannot descend through the birth canal. Therefore the cesarean section is recommended as the safest mode of delivery for mentum posterior face presentations.

Attempts to manually convert face presentation to vertex, manual or forceps rotation of the persistent posterior chin to anterior are contraindicated as they can be dangerous.

Persistent brow presentation itself is a contraindication for vaginal delivery unless the fetus is significantly small or the maternal pelvis is large.

Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring is recommended for face and brow presentations, as heart rate abnormalities are common in these scenarios. One study found that only 14% of the cases with face presentation had no abnormal traces on the cardiotocograph. [8] It is advised to use external transducer devices to prevent damage to the eyes. When internal monitoring is inevitable, it is suggested to place monitoring devices on bony parts carefully.

People who are usually involved in the delivery of face/ brow presentation are:

- Experienced midwife, preferably looking after laboring woman 1:1

- Senior obstetrician

- Neonatal team - in case of need for resuscitation

- Anesthetic team - to provide necessary pain control (e.g., epidural)

- Theatre team - in case of failure to progress and an emergency cesarean section will be required.

- Preparation

No specific preparation is required for face or brow presentation. However, it is essential to discuss the labor options with the mother and birthing partner and inform members of the neonatal, anesthetic, and theatre co-ordinating teams.

- Technique or Treatment

Mechanism of Labor in Face Presentation

During contractions, the pressure exerted by the fundus of the uterus on the fetus and pressure of amniotic fluid initiate descent. During this descent, the fetal neck extends instead of flexing. The internal rotation determines the outcome of delivery, if the fetal chin rotates posteriorly, vaginal delivery would not be possible, and cesarean section is permitted. The approach towards mentum-posterior delivery should be individualized, as the cases are rare. Expectant management is acceptable in multiparous women with small fetuses, as a spontaneous mentum-anterior rotation can occur. However, there should be a low threshold for cesarean section in primigravida women or women with large fetuses.

When the fetal chin is rotated towards maternal symphysis pubis as described as mentum-anterior; in these cases further descend through the vaginal canal continues with approximately 73% cases deliver spontaneously. [9] Fetal mentum presses on the maternal symphysis pubis, and the head is delivered by flexion. The occiput is pointing towards the maternal back, and external rotation happens. Shoulders are delivered in the same manner as in vertex delivery.

Mechanism of Labor in Brow Presentation

As this presentation is considered unstable, it is usually converted into a face or an occiput presentation. Due to the cephalic diameter being wider than the maternal pelvis, the fetal head cannot engage; thus, brow delivery cannot take place. Unless the fetus is small or the pelvis is very wide, the prognosis for vaginal delivery is poor. With persistent brow presentation, a cesarean section is required for safe delivery.

- Complications

As the cesarean section is becoming a more accessible mode of delivery in malpresentations, the incidence of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality during face presentation has dropped significantly. [10]

However, there are still some complications associated with the nature of labor in face presentation. Due to the fetal head position, it is more challenging for the head to engage in the birth canal and descend, resulting in prolonged labor.

Prolonged labor itself can provoke foetal distress and arrhythmias. If the labor arrests or signs of fetal distress appear on CTG, the recommended next step in management is an emergency cesarean section, which in itself carries a myriad of operative and post-operative complications.

Finally, due to the nature of the fetal position and prolonged duration of labor in face presentation, neonates develop significant edema of the skull and face. Swelling of the fetal airway may also be present, resulting in respiratory distress after birth and possible intubation.

- Clinical Significance

During vertex presentation, the fetal head flexes, bringing the chin to the chest, forming the smallest possible fetal head diameter, measuring approximately 9.5cm. With face and brow presentation, the neck hyperextends, resulting in greater cephalic diameters. As a result, the fetal head will engage later, and labor will progress more slowly. Failure to progress in labor is also more common in both presentations compared to vertex presentation.

Furthermore, when the fetal chin is in a posterior position, this prevents further flexion of the fetal neck, as browns are pressing on the symphysis pubis. As a result, descend through the birth canal is impossible. Such presentation is considered undeliverable vaginally and requires an emergency cesarean section.

Manual attempts to change face presentation to vertex, manual or forceps rotation to mentum anterior are considered dangerous and are discouraged.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multidisciplinary team of healthcare experts supports the woman and her child during labor and the perinatal period. For a face or brow presentation to be appropriately diagnosed, an experienced midwife and obstetrician must be involved in the vaginal examination and labor monitoring. As fetal anomalies, such as anencephaly or goiter, can contribute to face presentation, sonographers experienced in antenatal scanning should also be involved in the care. It is advised to inform the anesthetic and neonatal teams in advance of the possible need for emergency cesarean section and resuscitation of the neonate. [11] [12]

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Julija Makajeva declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Mohsina Ashraf declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Makajeva J, Ashraf M. Delivery, Face and Brow Presentation. [Updated 2023 Jan 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Sonographic diagnosis of fetal head deflexion and the risk of cesarean delivery. [Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020] Sonographic diagnosis of fetal head deflexion and the risk of cesarean delivery. Bellussi F, Livi A, Cataneo I, Salsi G, Lenzi J, Pilu G. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 Nov; 2(4):100217. Epub 2020 Aug 18.

- Review Sonographic evaluation of the fetal head position and attitude during labor. [Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022] Review Sonographic evaluation of the fetal head position and attitude during labor. Ghi T, Dall'Asta A. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Jul 6; . Epub 2022 Jul 6.

- Stages of Labor. [StatPearls. 2024] Stages of Labor. Hutchison J, Mahdy H, Hutchison J. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Leopold Maneuvers. [StatPearls. 2024] Leopold Maneuvers. Superville SS, Siccardi MA. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Review Labor with abnormal presentation and position. [Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. ...] Review Labor with abnormal presentation and position. Stitely ML, Gherman RB. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005 Jun; 32(2):165-79.

Recent Activity

- Delivery, Face and Brow Presentation - StatPearls Delivery, Face and Brow Presentation - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Mammary Glands

- Fallopian Tubes

- Supporting Ligaments

- Reproductive System

- Gametogenesis

- Placental Development

- Maternal Adaptations

- Menstrual Cycle

- Antenatal Care

- Small for Gestational Age

- Large for Gestational Age

- RBC Isoimmunisation

- Prematurity

- Prolonged Pregnancy

- Multiple Pregnancy

- Miscarriage

- Recurrent Miscarriage

- Ectopic Pregnancy

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

- Breech Presentation

- Abnormal lie, Malpresentation and Malposition

- Oligohydramnios

- Polyhydramnios

- Placenta Praevia

- Placental Abruption

- Pre-Eclampsia

- Gestational Diabetes

- Headaches in Pregnancy

- Haematological

- Obstetric Cholestasis

- Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

- Epilepsy in Pregnancy

- Induction of Labour

- Operative Vaginal Delivery

- Prelabour Rupture of Membranes

- Caesarean Section

- Shoulder Dystocia

- Cord Prolapse

- Uterine Rupture

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism

- Primary PPH

- Secondary PPH

- Psychiatric Disease

- Postpartum Contraception

- Breastfeeding Problems

- Primary Dysmenorrhoea

- Amenorrhoea and Oligomenorrhoea

- Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

- Endometriosis

- Endometrial Cancer

- Adenomyosis

- Cervical Polyps

- Cervical Ectropion

- Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia + Cervical Screening

- Cervical Cancer

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- Ovarian Cysts & Tumours

- Urinary Incontinence

- Genitourinary Prolapses

- Bartholin's Cyst

- Lichen Sclerosus

- Vulval Carcinoma

- Introduction to Infertility

- Female Factor Infertility

- Male Factor Infertility

- Female Genital Mutilation

- Barrier Contraception

- Combined Hormonal

- Progesterone Only Hormonal

- Intrauterine System & Device

- Emergency Contraception

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Genital Warts

- Genital Herpes

- Trichomonas Vaginalis

- Bacterial Vaginosis

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- Obstetric History

- Gynaecological History

- Sexual History

Obstetric Examination

- Speculum Examination

- Bimanual Examination

- Amniocentesis

- Chorionic Villus Sampling

- Hysterectomy

- Endometrial Ablation

- Tension-Free Vaginal Tape

- Contraceptive Implant

- Fitting an IUS or IUD

Original Author(s): Minesh Mistry Last updated: 12th November 2018 Revisions: 7

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Preparation

- 3 General Inspection

- 4 Abdominal Inspection

- 5.1 Fundal Height

- 5.3 Presentation

- 5.4 Liquor Volume

- 5.5 Engagement

- 6 Fetal Auscultation

- 7 Completing the Examination

The obstetric examination is a type of abdominal examination performed in pregnancy.

It is unique in the fact that the clinician is simultaneously trying to assess the health of two individuals – the mother and the fetus.

In this article, we shall look at how to perform an obstetric examination in an OSCE-style setting.

Introduction

- Introduce yourself to the patient

- Wash your hands

- Explain to the patient what the examination involves and why it is necessary

- Obtain verbal consent

Preparation

- In the UK, this is performed at the booking appointment, and is not routinely recommended at subsequent visits

- Patient should have an empty bladder

- Cover above and below where appropriate

- Ask the patient to lie in the supine position with the head of the bed raised to 15 degrees

- Prepare your equipment: measuring tape, pinnard stethoscope or doppler transducer, ultrasound gel

General Inspection

- General wellbeing – at ease or distressed by physical pain.

- Hands – palpate the radial pulse.

- Head and neck – melasma, conjunctival pallor, jaundice, oedema.

- Legs and feet – calf swelling, oedema and varicose veins.

Abdominal Inspection

In the obstetric examination, inspect the abdomen for:

- Distension compatible with pregnancy

- Fetal movement (>24 weeks)

- Surgical scars – previous Caesarean section, laproscopic port scars

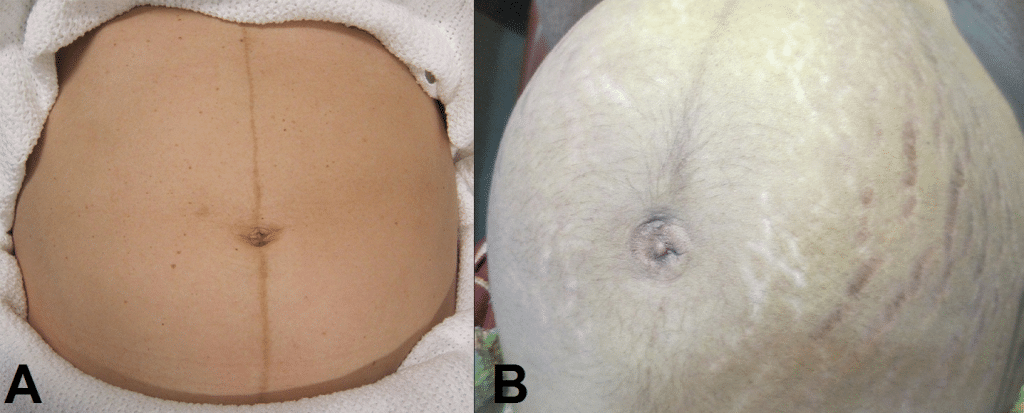

- Skin changes indicative of pregnancy – linea nigra (dark vertical line from umbilicus to the pubis), striae gravidarum (‘stretch marks’), striae albicans (old, silvery-white striae)

Fig 1 – Skin changes in pregnancy. A) Linea nigra. B) Striae gravidarum and albicans.

Ask the patient to comment on any tenderness and observe her facial and verbal responses throughout. Note any guarding.

Fundal Height

- Use the medial edge of the left hand to press down at the xiphisternum, working downwards to locate the fundus.

- Measure from here to the pubic symphysis in both cm and inches. Turn the measuring tape so that the numbers face the abdomen (to avoid bias in your measurements).

- Uterus should be palpable after 12 weeks, near the umbilicus at 20 weeks and near the xiphisternum at 36 weeks (these measurements are often slightly different if the woman is tall or short).

- The distance should be similar to gestational age in weeks (+/- 2 cm).

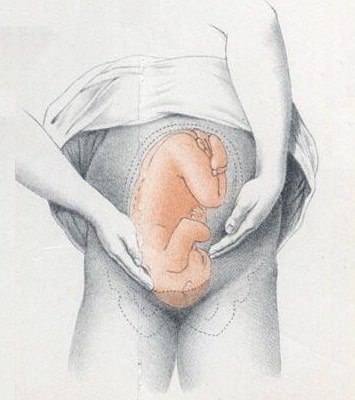

- Facing the patient’s head, place hands on either side of the top of the uterus and gently apply pressure

- Move the hands and palpate down the abdomen

- One side will feel fuller and firmer – this is the back. Fetal limbs may be palpable on the opposing side

Fig 2 – Assessing fetal lie and presentation.

Presentation

- Palpate the lower uterus (below the umbilicus) to find the presenting part.

- Firm and round signifies cephalic, soft and/or non-round suggests breech. If breech presentation is suspected, the fetal head can be often be palpated in the upper uterus.

- Ballot head by pushing it gently from one side to the other.

Liquor Volume

- Palpate and ballot fluid to approximate volume to determine if there is oligohydraminos/polyhydramnios

- When assessing the lie, only feeling fetal parts on deep palpation suggests large amounts of fluid

- Fetal engagement refers to whether the presenting part has entered the bony pelvis

- Note how much of the head is palpable – if the entire head is palpable, the fetus is unengaged.

- Engagement is measured in 1/5s

Fig 3 – Assessing fetal engagement.

Fetal Auscultation

- Hand-held Doppler machine >16 weeks (trying before this gestation often leads to anxiety if the heart cannot be auscultated).

- Pinard stethoscope over the anterior shoulder >28 weeks

- Feel the mother’s pulse at the same time

- Should be 110-160bpm (>24 weeks)

Completing the Examination

- Palpate the ankles for oedema and test for hyperreflexia (pre-eclampsia)

- Thank the patient and allow them to dress in private

- Summarise findings

- Blood pressure

- Urine dipstick

- Hands - palpate the radial pulse.

- Skin changes indicative of pregnancy - linea nigra (dark vertical line from umbilicus to the pubis), striae gravidarum ('stretch marks'), striae albicans (old, silvery-white striae)

- One side will feel fuller and firmer - this is the back. Fetal limbs may be palpable on the opposing side

Found an error? Is our article missing some key information? Make the changes yourself here!

Once you've finished editing, click 'Submit for Review', and your changes will be reviewed by our team before publishing on the site.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site and to show you relevant advertising. To find out more, read our privacy policy .

Privacy Overview

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

Diagnosis and management of face and brow presentations will be reviewed here. Other cephalic malpresentations are discussed separately. (See "Occiput posterior position" and "Occiput transverse position" .)

Prevalence — Face and brow presentation are uncommon. Their prevalences compared with other types of malpresentations are shown below [ 1-9 ]:

● Occiput posterior – 1/19 deliveries

● Breech – 1/33 deliveries

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation |

During pregnancy, the fetus can be positioned in many different ways inside the mother's uterus. The fetus may be head up or down or facing the mother's back or front. At first, the fetus can move around easily or shift position as the mother moves. Toward the end of the pregnancy the fetus is larger, has less room to move, and stays in one position. How the fetus is positioned has an important effect on delivery and, for certain positions, a cesarean delivery is necessary. There are medical terms that describe precisely how the fetus is positioned, and identifying the fetal position helps doctors to anticipate potential difficulties during labor and delivery.

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains growths such as fibroids .

The fetus has a birth defect .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Variations in fetal position and presentation.

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

When a fetus faces up, the neck is often straightened rather than bent,which requires more room for the head to pass through the birth canal. Delivery assisted by a vacuum device or forceps or cesarean delivery may be necessary.

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

In a first delivery, these problems may occur more frequently because a woman’s tissues have not been stretched by previous deliveries. Because of risk of injury or even death to the baby, cesarean delivery is preferred when the fetus is in breech presentation, unless the doctor is very experienced with and skilled at delivering breech babies or there is not an adequate facility or equipment to safely perform a cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains abnormal growths such as fibroids .

Other presentations

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

CHAPTER 22: Normal Labor

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Fetal orientation.

- MECHANISMS OF LABOR

- NORMAL LABOR CHARACTERISTICS

- MANAGEMENT OF NORMAL LABOR

- LABOR MANAGEMENT PROTOCOLS

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Labor is the process that leads to childbirth. It begins with the onset of regular uterine contractions and ends with delivery of the newborn and expulsion of the placenta. Pregnancy and birth are physiological processes. Thus, labor and delivery should be considered normal for most women.

Fetal position within the birth canal is critical to labor progress and to the delivery route. It should be determined in early labor, and sonography can be implemented for unclear cases. Important relationships include fetal lie, presentation, attitude, and position.

Of these, fetal lie describes the relationship of the fetal long axis to that of the mother. In more than 99 percent of labors at term, the fetal lie is longitudinal . A transverse lie is less frequent. Occasionally, the fetal and maternal axes may cross at a 45-degree angle to form an oblique lie . This is unstable and becomes longitudinal or transverse during labor.

Fetal Presentation

The presenting part is the portion of the fetal body either within or in closest proximity to the birth canal. It usually can be felt through the cervix on vaginal examination. In longitudinal lies, the presenting part is either the fetal head or the breech, creating cephalic and breech presentations, respectively. When the fetus lies with the long axis transversely, the shoulder is considered the presenting part.

Cephalic presentations are subclassified according to the relationship between the head and body of the fetus ( Fig. 22-1 ). Ordinarily, the head is flexed sharply so that the chin contacts the thorax. The occipital fontanel is the presenting part, and this presentation is referred to as a vertex or occiput presentation . Much less often, the fetal neck may be sharply extended so that the occiput and back come into contact, and the face is foremost in the birth canal— face presentation . The fetal head may assume a position between these extremes. When the neck is only partly flexed, the anterior (large) fontanel may present— sinciput presentation . When the neck is only partially extended, the brow may emerge— brow presentation . These latter two are usually transient. As labor progresses, sinciput and brow presentations almost always convert into occiput or face presentations by neck flexion or extension, respectively. If not, dystocia can develop ( Chap. 23 , p. 441).

FIGURE 22-1

Longitudinal lie, cephalic presentation. Differences in attitude of the fetal body in (A) occiput, (B) sinciput, (C) brow, and (D) face presentations. Note changes in fetal attitude as the fetal head becomes less flexed.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Cord presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created Yuranga Weerakkody had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Joshua Yap had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Funic presentation

- Cord (funic) presentation

A cord presentation (also known as a funic presentation or obligate cord presentation ) is a variation in the fetal presentation where the umbilical cord points towards the internal cervical os or lower uterine segment.

It may be a transient phenomenon and is usually considered insignificant until ~32 weeks. It is concerning if it persists past that date, after which it is recommended that an underlying cause be sought and precautionary management implemented.

On this page:

Epidemiology, radiographic features, treatment and prognosis, differential diagnosis.

- Cases and figures

The estimated incidence is at ~4% of pregnancies.

Associations

Recognized associations include:

marginal cord insertion from the caudal end of a low-lying placenta

uterine fibroids

uterine adhesions

congenital uterine anomalies that may prevent the fetus from engaging well into the lower uterine segment

cephalopelvic disproportion

polyhydramnios

multifetal pregnancy

long umbilical cord

Color Doppler interrogation is extremely useful and shows cord between the fetal presenting part and the internal cervical os. However, unlike a vasa previa , the placental insertion is usually normal.

As the complicating umbilical cord prolapse can lead to catastrophic consequences, most advocate an elective cesarean section delivery for persistent cord presentation in the third trimester 3 .

Complications

It can result in a higher rate of umbilical cord prolapse .

For the presence of umbilical cord vessels between the fetal presenting part and the internal cervical os on ultrasound consider:

vasa previa

- 1. Ezra Y, Strasberg SR, Farine D. Does cord presentation on ultrasound predict cord prolapse? Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2003;56 (1): 6-9. doi:10.1159/000072323 - Pubmed citation

- 2. Kinugasa M, Sato T, Tamura M et-al. Antepartum detection of cord presentation by transvaginal ultrasonography for term breech presentation: potential prediction and prevention of cord prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2007;33 (5): 612-8. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00620.x - Pubmed citation

- 3. Raga F, Osborne N, Ballester MJ et-al. Color flow Doppler: a useful instrument in the diagnosis of funic presentation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88 (2): 94-6. - Free text at pubmed - Pubmed citation

- 4. Bluth EI. Ultrasound, a practical approach to clinical problems. Thieme Publishing Group. (2008) ISBN:3131168323. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Variation in fetal presentation

- Vasa praevia

- Umbilical cord prolapse

- Vasa previa

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

SEQ indicates Sexual Experiences Questionnaire-short form.

a Sexual harassment was not reported by sex, but 530 of 907 respondents (58.4%) were female. The percentage of harassment at each training level was calculated based on the assumption that all respondents were medical students or residents prior to independent practice; 26 fellows experienced sexual harassment, but this was not included due to lack of denominator.

b Sexual harassment per SEQ was based on any answer other than never to any SEQ question. Sexually harassed was based on the answer yes to the question “Have you ever been sexually harassed in your training?”

eAppendix 1. Search Strategy

eAppendix 2. Study Methodology

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Gupta A , Thompson JC , Ringel NE, et al. Sexual Harassment, Abuse, and Discrimination in Obstetrics and Gynecology : A Systematic Review . JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(5):e2410706. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.10706

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Sexual Harassment, Abuse, and Discrimination in Obstetrics and Gynecology : A Systematic Review

- 1 Division of Urogynecology, University of Louisville Health, Louisville, Kentucky

- 2 Division of Urogynecology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwest Kaiser Permanente, Portland, Oregon

- 3 Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

- 4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

- 5 Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center/Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio

- 6 Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

- 7 Division of Urogynecology, MedStar Health, Washington, District of Columbia

- 8 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, District of Columbia

- 9 Center for Evidence Synthesis in Health, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island

- 10 Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Duke University Medical Center, Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, North Carolina

- 11 University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut

- 12 Atrium Health Levine Cancer, Charlotte, North Carolina

- 13 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York Medical College and Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, New York

Question What is the prevalence of sexual harassment, bullying, abuse, workplace discrimination, and other forms of harassment among medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians in obstetrics and gynecology (OB-GYN)?

Findings In this systematic review of 10 studies of harassment among 5852 participants and 12 studies among 2906 participants of interventions, sexual harassment (range, 28%-71%), workplace discrimination (range, 57%-67% among females; 39% among males), and bullying (53%) were frequent among OB-GYN respondents.

Meaning These findings suggest that there is high prevalence of harassment in OB-GYN despite the field being a female dominant for the last decade.

Importance Unlike other surgical specialties, obstetrics and gynecology (OB-GYN) has been predominantly female for the last decade. The association of this with gender bias and sexual harassment is not known.

Objective To systematically review the prevalence of sexual harassment, bullying, abuse, and discrimination among OB-GYN clinicians and trainees and interventions aimed at reducing harassment in OB-GYN and other surgical specialties.

Evidence Review A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted to identify studies published from inception through June 13, 2023. : For the prevalence of harassment, OB-GYN clinicians and trainees on OB-GYN rotations in all subspecialties in the US or Canada were included. Personal experiences of harassment (sexual harassment, bullying, abuse, and discrimination) by other health care personnel, event reporting, burnout and exit from medicine, fear of retaliation, and related outcomes were included. Interventions across all surgical specialties in any country to decrease incidence of harassment were also evaluated. Abstracts and potentially relevant full-text articles were double screened. : Eligible studies were extracted into standard forms. Risk of bias and certainty of evidence of included research were assessed. A meta-analysis was not performed owing to heterogeneity of outcomes.

Findings A total of 10 eligible studies among 5852 participants addressed prevalence and 12 eligible studies among 2906 participants addressed interventions. The prevalence of sexual harassment (range, 250 of 907 physicians [27.6%] to 181 of 255 female gynecologic oncologists [70.9%]), workplace discrimination (range, 142 of 249 gynecologic oncologists [57.0%] to 354 of 527 gynecologic oncologists [67.2%] among women; 138 of 358 gynecologic oncologists among males [38.5%]), and bullying (131 of 248 female gynecologic oncologists [52.8%]) was frequent among OB-GYN respondents. OB-GYN trainees commonly experienced sexual harassment (253 of 366 respondents [69.1%]), which included gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. The proportion of OB-GYN clinicians who reported their sexual harassment to anyone ranged from 21 of 250 AAGL (formerly, the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists) members (8.4%) to 32 of 256 gynecologic oncologists (12.5%) compared with 32.6% of OB-GYN trainees. Mistreatment during their OB-GYN rotation was indicated by 168 of 668 medical students surveyed (25.1%). Perpetrators of harassment included physicians (30.1%), other trainees (13.1%), and operating room staff (7.7%). Various interventions were used and studied, which were associated with improved recognition of bias and reporting (eg, implementation of a video- and discussion-based mistreatment program during a surgery clerkship was associated with a decrease in medical student mistreatment reports from 14 reports in previous year to 9 reports in the first year and 4 in the second year after implementation). However, no significant decrease in the frequency of sexual harassment was found with any intervention.

Conclusions and Relevance This study found high rates of harassment behaviors within OB-GYN. Interventions to limit these behaviors were not adequately studied, were limited mostly to medical students, and typically did not specifically address sexual or other forms of harassment.

Bullying, sexual harassment, and discrimination are pervasive across society, and mistreatment is often based on personal characteristics or demographics, such as sex, gender, and race and ethnicity. A 2021 systematic review 1 found that within academic medicine, bullying commonly involved overwork and was associated with negative outcomes for well-being and psychological distress. Academic bulling was associated with 44% of women reporting loss of career opportunities and 32% of men experiencing decreased confidence. 1 Unlike bullying, which can be more amorphous, sexual harassment in the workplace comprises 3 major forms: sexual coercion, consisting of using professional rewards or threats for sexual favors; unwanted sexual attention, such as unwelcome advances, touching, assault, or rape; and gender harassment, referring to offensive verbal slurs, gestures, or sexist remarks like “Women don’t belong in surgery.” 2 , 3 In 2018, the National Academies of Sciences (NAS) found that sexual harassment was highly prevalent, with more than 45% of women in medicine experiencing sexist hostility and 18% experiencing crude behavior. Findings confirmed that sexual harassment is associated with impeded professional and educational goal attainment for women, undermined research integrity, a reduced talent pool, and negative physical and mental health outcomes among targets and bystanders. 3

Building on the NAS report, several authors reported even higher rates of harassment in women 4 and extended findings to include men, transgender and gender nonbinary individuals, and those with intersectional identities across various medical subspecialties. 5 In 2023, harassment in various forms was reported via traditional media outlets and digital and social media. This led to multiple society statements condemning harassment and violence in medicine and a commitment by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 6 and other professional societies, including the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) and Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), to address needs of professional members. 7 The joint SGS/SGO statement, endorsed by 11 other societies and foundations, outlines the expectation that members uphold principles of ethical conduct; categorically opposes and condemns sexual or verbal harassment of any kind; reiterates that all people should be treated with dignity, respect, and compassion; and provides resources to individuals experiencing harassment. 7 The purpose of this systematic review was to investigate the prevalence of sexual harassment, bullying, abuse, workplace discrimination, and other forms of harassment in the obstetrics and gynecology (OB-GYN) field and evaluate interventions to reduce harassment across surgical specialties.

This systematic review was conducted as a joint venture between the SGS Systematic Review Group and SGO using standard systematic review methodology, including an a priori protocol (PROSPERO registration, CRD42023439415 ). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses ( PRISMA ) reporting guideline was followed. The University of Louisville Institutional Review Board determined that this systematic review did not require institutional review board approval because the project did not meet the Common Rule definition of human participant research.

The 12-member working team comprised gynecologists (A.G. and S.K.F.), urogynecologists (A.G., J.C.T., N.E.R., S.K.F., C.B.I., and C.L.G.), gynecologic oncologists (L.A.F., S.V.B., A.A.S., J.F.H., and J.B.), and a systematic review methodologist (E.M.B.). We searched PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to June 13, 2023. Full search strategies included broad terminology to identify interventions and outcomes of interest in surgical specialties (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1 ). Reference lists of similar systematic reviews were also screened.

We evaluated workplace harassment among and by health care workers. We excluded harassment by patients or family members. Eligibility criteria for prevalence and intervention studies, along with further details about methods, are described in eAppendix 2 in Supplement 1 . Abstracts were screened in duplicate using Abstrackr software (Brown University Center for Evidence Synthesis in Health). 8 Potentially relevant full-text articles were rescreened in duplicate. We extracted data in duplicate into SRDRplus. 9

Prevalence studies were assessed for clarity, completeness of reporting, representativeness of surveyed participants, response rate, and reliability and validity of the survey instrument. Intervention studies were assessed with the Cochrane risk of bias tool, and selected questions from the Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions tool were used as applicable per study. 10 , 11 Each study was assigned as good, fair, or poor quality based on likelihood of biases, scientific merit, and completeness of reporting.

The literature search identified 13 886 citations, of which 162 were retrieved for full-text screening. We also screened 54 systematic reviews for relevant references. In total, we included 22 studies that met eligibility criteria; 10 studies among 5852 participants addressed prevalence, 2 , 4 , 12 - 19 and 12 studies among 2906 participants addressed interventions 20 - 31 ( Figure 1 ). A meta-analysis was not feasible due to substantial study heterogeneity.

A total of 10 studies met inclusion criteria for reporting on prevalence of harassment, bullying, and mistreatment in OB-GYN in the US and Canada, including 6 studies 2 , 4 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 19 among 2214 practicing OB-GYN clinicians or OB-GYN clinicians in training and 4 studies 14 , 16 - 18 among 3638 medical students surveyed about mistreatment, harassment, belittlement, and verbal and physical abuse while on their OB-GYN clerkship. Studies were predominantly survey based and cross-sectional. Overall, the quality of studies was moderate, with concerns about low response rates (range, 907 of 7026 individuals [12.9%] 13 to 505 of 513 individuals [98.4%] 16 ) ( Table 1 ).

A total of 3 studies queried the prevalence of sexual harassment among OB-GYN clinicians ( Figure 2 ). 2 , 4 , 13 Definitions and reporting of sexual harassment differed by study. A survey of 402 gynecologic oncologists found that 256 respondents (63.6%) had experienced some form of sexual harassment, including unwanted sexual advances, sexist remarks, or the exchanging of sexual favors for an academic position. Sexual harassment was more common among females (181 of 255 respondents [70.9%]) but also commonly occurred among male respondents (75 of 147 respondents [51.0%]). 4

Among 907 physician members of the AAGL (formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopy), 250 respondents (27.6%) reported sexual harassment, including suggestive or offensive stories, attempts to establish a sexual relationship, bribes to engage in sexual behavior, and sexual assault. 13 Most respondents who had experienced sexual assault were within the US (198 respondents [79.2%]), and 226 perpetrators (90.4%) were physicians. 13

A survey of 366 OB-GYN trainees found that 253 respondents (69.1%), including 32 of 46 men (69.6%) and 202 of 294 women (68.7%), had experienced sexual harassment based on responses other than never on the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire. 2 This included gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. The largest group of perpetrators consisted of senior OB-GYN attending physicians (30.1%), while 13.1% were residents or fellows, 8.2% were patients, and 7.7% were operating room staff. 2 While 10.6% of perpetrators were women, they were the perpetrators in 57.7% of cases in which the individual experiencing harassment was a man trainee. 2

Reporting of sexual harassment to colleagues, supervisors, or other responsible parties varied widely. A total of 32 of 256 gynecologic oncologists (12.5%) and 21 of 250 AAGL members (8.4%) reported their sexual harassment. In the survey of 366 OB-GYN trainees, 32.6% of respondents who experienced harassment reported their harassment, predominantly (71.8%) to another trainee. 2 , 4 , 13 Among respondents who reported their harassment, 8% said that they did not feel that it was taken seriously. 2 From 63 of 188 individuals (33.5%) 4 to 80 of 199 individuals (40.2%) 13 experiencing harassment did not report due to fear of retaliation.

A total of 5 studies 4 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 19 evaluated bias, microaggressions, or workplace discrimination related to gender, sexual orientation, and race among OB-GYN clinicians. One study 12 considered OB-GYN to be a female-dominant surgical specialty and compared it with other surgical specialties considered to be male dominant (eg, general surgery, orthopedics, neurosurgery, and ear, nose, and throat surgery). Another study 19 queried multiple surgical specialists, including OB-GYN clinicians, about microaggressions against surgeons based on gender, race, and ethnicity. The other 3 studies 4 , 13 , 15 focused on OB-GYN clinicians.

A survey of 250 female gynecologic oncologists found that 131 of 248 respondents with data (52.8%) reported bullying and 142 of 249 respondents with data (57.0%) reported gender discrimination. Most respondents (208 individuals [83.2%]) reported microaggressions, including being told to smile more, dress in certain ways, or to “act more female” or “motherly.” 15 In another study of gynecologic oncologists, 4 71 of 215 women (33.0%) reported being denied opportunities for training or rewards based on gender compared with 25 of 131 men (19.1%). Although men experienced significantly less workplace discrimination than women (138 of 358 men [38.5%]) vs 354 of 527 women [67.2%]), gender discrimination was the most common form of discrimination for men (99 of 137 men [72.3%]) and women (318 of 353 women [90.1%]) in gynecologic surgery. 13 Although OB-GYN is considered a female-dominant specialty, among 18 OB-GYN trainees, 17 respondents (94.4%) had been mistaken as nonphysicians, while 16 respondents (88.9%) preapologized for asking for something from a surgical technician or a nurse and 15 respondents (83.3%) needed to make such requests multiple times. 12 Surgical technicians and circulating nurses were predominantly responsible for these microaggressions (13 respondents [72.2%]). 12 In another survey-based study assessing burnout as a sequela of microaggressions, 19 115 of 218 OB-GYN clinicians reported burnout experiences (52.8%).

There were 4 studies 14 , 16 - 18 that evaluated medical student experiences on clinical clerkships in OB-GYN. Among 668 medical students in 1 study, 18 168 respondents (25.1%) reported occasional or frequent mistreatment (eg, verbal abuse, coercion, or negative consequences) during OB-GYN rotations; resident physicians were the most common source. In another survey-based study 14 among 91 medical students, almost three-quarters of respondents (65 respondents [71.4%]) reported belittlement and 22 respondents (24.2%) reported harassment by OB-GYN residents. Across all clerkship rotations, including general surgery, OB-GYN was noted to have the lowest professionalism scores. 16 In a small study from 1992, 17 4 of 16 medical students (25.0%) reported that they had experienced physical abuse while on OB-GYN.

Among 12 studies that evaluated interventions, 4 studies 20 , 21 , 24 , 27 evaluated interventions at the resident level in 258 participants, 1 study 23 evaluated a facultywide cultural competency program in 148 participants, and 7 studies 22 , 25 , 26 , 28 - 31 evaluated interventions to decrease medical student mistreatment in 2500 participants. Intervention studies included 1 randomized clinical trial, 28 6 nonrandomized prospective studies, 21 , 23 - 25 , 30 , 31 3 studies with a prospective and retrospective component, 20 , 27 , 29 and 2 studies evaluating a single intervention without comparison. 22 , 26 The overall quality of evidence was low owing to incomplete description of intervention or measurement tools and high risk of bias (10 studies [83.3%] rated as poor quality) ( Table 2 ).

There were 2 studies that described institutionwide initiatives to decrease medical student mistreatment. 22 , 26 The Gender and Power Abuse Committee 22 and the Ending Mistreatment Task Force 26 created multipronged interventions with support from faculty, administrators, and medical student representatives engaging with hospital medical staff leaders, student body representatives, clinical clerkship directors, and faculty governance leaders. Interventions included a no abuse policy, an ombuds office, improved reporting with prompt action, workshops for medical students and residents, and faculty grand rounds sessions. These interventions were associated with a decrease in reported medical student mistreatment ranging from 62.9% of respondents to 40.3% of respondents over 6 years in 1 study, 26 although the incidence of sexual harassment remained unchanged at 13.4% (260 of 1940 students) across all 4 study periods in the other study ( Table 2 ). 22

We assessed 4 studies that evaluated video-based discussions, 21 , 25 , 28 , 30 1 study that evaluated videos in a multipronged intervention, 26 2 studies that evaluated clinical scenarios and case-based workshops to prompt discussion, 24 , 31 and 2 studies (by the same author evaluating different medical specialties) that evaluated a forum theater intervention. 20 , 27 Forum theater is a learning modality in which learners become participants who watch, respond to, and step in to the play to act out potential solutions while a facilitator debriefs and reinforces key messages. 20 Target audiences were residents, 20 , 21 , 24 , 27 medical students, 25 , 28 , 30 , 31 or faculty 26 in the specialties of general surgery, 21 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 OB-GYN and urology, 20 or the entire medical school or class. 26 , 31 Overall, programs helped trainees to recognize mistreatment and were associated with improved confidence in intervening on their own behalf or on the behalf of others ( Table 2 ).

There were 3 studies that described programs to improve trainee education regarding mistreatment reporting, 22 , 25 , 26 and 1 study evaluated a real-time, web-based reporting module for medical students on the surgical clerkship. 29 While students perceived less intimidation and greater satisfaction with systems designed to improve reporting, the decrease in perceived abuse was not statistically significant. The implementation of a video- and discussion-based mistreatment program during a surgery clerkship was associated with a decrease in medical student mistreatment reports from 14 reports the year prior to the mistreatment program to 9 reports in the first year and 4 in the second year after implementation. 25 Using a real time, web-based reporting module, students with access to modules were less intimidated than students in a control group based on a 1 to 10 intimidation score (4.02 vs 5.31) and faculty (5.26 vs 6.28). 29

There was 1 study that evaluated a 9-week, departmentwide cultural competency curriculum on bias based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender in the surgery department. 23 The curriculum included formal presentations, role play–based simulation, and small group interactions and engaged faculty, residents, and staff. Among 148 participants, 73.7% reported that these interventions helped to analyze their own bias, 65.5% reported improvement in responding to their own bias, and 68.1% reported an improved ability to respond when they see bias in the workplace. 23

This systematic review found high rates of sexual harassment, gender bias, bullying, and discrimination within OB-GYN. However, interventions to limit these behaviors have not been adequately studied, were limited to medical students, or did not specifically address sexual or other forms of harassment.

The current literature reports a high prevalence of harassment behaviors directed toward surgical trainees. This was consistent with a systematic review addressing academic bullying that found that 32% of general surgery, 25% of OB-GYN, and 21% of medicine interns and medical students reported bullying. 1 Another systematic review found that 27% of surgical trainees (including OB-GYN) reported sexual harassment 32 and a study reviewing harassment rates across multiple medical specialties found that OB-GYN was second only to general surgery as the specialty associated with the highest rates of sexual harassment. 33 Undermining and bullying behaviors are commonplace in surgical specialties, with several physicians condoning tantrums, swearing, humiliation, and undermining of trainees as a “rite of passage.” 34 This can create a cycle of mistreatment, as seen when medical students experience high rates of belittlement and harassment from OB-GYN residents, who may be modeling behavior seen in senior physicians. 14 , 34 Surgical specialties, including OB-GYN, are also high-pressure environments; combined with perfectionist characteristics seen in surgeons, this can create an environment of bullying and harassment. 34 Equipping OB-GYN clinicians to be better surgical educators, providing clinical support, and modeling positive behavior may help disrupt the culture of harassment. 34 , 35

The power differential between medical trainees and other health care professionals, including physicians and nursing staff, can also lead to underreported abuses of professional power. The role of gender is critical to understanding sexual harassment. Although sexual harassment and gender bias were more commonly reported by female OB-GYN respondents, male OB-GYN respondents also reported high rates of sexual harassment and gender discrimination, often by female perpetrators. This suggests that focus should be on perpetrators and leadership demographics to identify harassment behaviors. Unlike many other surgical specialties, OB-GYN has had an increase in the number of women clinicians, from 47% in 2010 to the majority (61%) in 2021. 36 Despite high numbers of women OB-GYN residents and overrepresentation of women in residency program director roles, women continue to be underrepresented in departmental leadership, making up 24% of chairs in 2013 and 34% of chairs in 2021. 36 , 37 However, the continued high rates of harassment in OB-GYN suggest that simply increasing the number of women in medicine is inadequate to address gender bias and discrimination. Rather, the role of power dynamics should be better studied and addressed to reduce harassment.

The high prevalence of sexual harassment in this review may be due in part to varied definitions of sexual harassment across studies. Sexual harassment can include a broad range of behaviors that humiliate, diminish, and demean a person on the basis of sex or gender, including gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. 2 , 3 Most women do not consider or report gender harassment as sexual harassment, 2 explaining the wide range of reported prevalence depending on terminology used in surveys. Additionally, many women underreport incidents of harassment and sexual assault, 3 and unclear definitions make it difficult for individuals who have experienced harassment to definitively come forward. All trainees should be better versed in all aspects of harassment to improve recognition and reporting in a confidential way free of fear of retaliation.

Interventions to address these pervasive behaviors would seem to be the obvious next step, but unfortunately, interventions to decrease harassment and specifically sexual harassment have been poorly studied. Successful interventions involved change at an institutional level and required support from multiple levels, including hospital administration, management, and leadership. 26 While providing tools to educate health care staff about harassment may be associated with improved trainee and bystander confidence in standing up for individuals experiencing harassment, the need to maintain confidentiality in reporting presents an additional challenge. 1 , 20 This is especially true in cases of sexual harassment where details may be known only to the perpetrator and the individual experiencing harassment. When physicians are required to report their grievances to immediate supervisors, they may perceive senior physicians as untouchable. 1 , 38 , 39 One viable approach appears to be establishing an office of gender equity, as reported by the Medical University of South Carolina, 38 comprising university faculty with experience in responding to sexual harassment and interpersonal violence. All complaints are evaluated by an intermediary third party who interviews the accuser and accused separately before coming to a determination, thus protecting the individual reporting harassment and alleged perpetrator. 38 Additional approaches include the Office of Professionalism developed by the University of Colorado School of Medicine, which provides nonpunitive feedback and makes professionalism a component of promotion. 26

This study has several limitations, with the major limitations related to the heterogenous evidence base, including wide variability of assessed forms of harassment and inconsistent or incompletely defined terminology. Additionally, variations in study participant specialties and subspecialties and level of training precluded meta-analyses across studies. Studies were predominantly survey based and retrospective, with moderate to low quality of evidence. Nonresponse and recall bias may have played a large role given that individuals who have been sexually harassed are less inclined to respond to this type of survey. 2 Therefore, the prevalence of sexual harassment may be different than that reported here. With 1 exception, 20 , 27 each intervention was evaluated by 1 study.

This study also has several strengths. It was a joint collaboration among experienced gynecologists, urogynecologists, and gynecologic oncologists and was conducted using a robust methodology. While other systematic reviews have addressed these topics in general surgery, this study specifically identified studies that included or were limited to OB-GYN to provide data within a surgical specialty that currently is majority female.

This systematic review found that 28% to 71% of participants reported sexual harassment, sexual coercion, or unwanted sexual advances within the field of OB-GYN in surveys. These events were often not reported to institutional leadership, however, given that individuals experiencing these forms of mistreatment feared retaliation and did not feel that their experiences would be taken seriously. There were also high rates of bullying, gender bias, and microaggressions among trainees and practicing physicians. Interventions to decrease harassment had not been adequately studied, but institutionwide, multipronged approaches with support from varying levels of stakeholders appeared to have the highest efficacy for reductions in mistreatment in medical training. Nevertheless, most interventions were not associated with reduced sexual harassment. National medical and hospital associations and departmental and institutional leaders should use these findings to acknowledge the prevalence of bullying, abuse, and sexual harassment and begin to work collectively on best practices to prevent harassment and discrimination, improve reporting, and intervene once reports of alleged misconduct, abuse, and sexual harassment are received. Future studies should focus on such interventions to improve the practicing climate, model professional behavior, and intervene appropriately when harassment behavior is identified within OB-GYN and medicine at large.

Accepted for Publication: March 9, 2024.

Published: May 8, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.10706

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2024 Gupta A et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Ankita Gupta, MD, MPH, Division of Urogynecology, University of Louisville Health, 4331 Churchman Ave, Ste 101, Louisville, KY 40215 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Dr Gupta had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Gupta, Thompson, Ringel, Blank, Iglesia, Balk, Hines, Brown, Grimes.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Gupta, Thompson, Ringel, Kim-Fine, Ferguson, Blank, Iglesia, Balk, Secord, Grimes.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Thompson, Ringel, Ferguson, Blank, Iglesia, Balk, Secord, Brown, Grimes.

Statistical analysis: Gupta, Thompson, Balk.