- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Case Study in Education Research

Introduction, general overview and foundational texts of the late 20th century.

- Conceptualisations and Definitions of Case Study

- Case Study and Theoretical Grounding

- Choosing Cases

- Methodology, Method, Genre, or Approach

- Case Study: Quality and Generalizability

- Multiple Case Studies

- Exemplary Case Studies and Example Case Studies

- Criticism, Defense, and Debate around Case Study

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Program Evaluation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- English as an International Language for Academic Publishing

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Case Study in Education Research by Lorna Hamilton LAST REVIEWED: 27 June 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 27 June 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0201

It is important to distinguish between case study as a teaching methodology and case study as an approach, genre, or method in educational research. The use of case study as teaching method highlights the ways in which the essential qualities of the case—richness of real-world data and lived experiences—can help learners gain insights into a different world and can bring learning to life. The use of case study in this way has been around for about a hundred years or more. Case study use in educational research, meanwhile, emerged particularly strongly in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom and the United States as a means of harnessing the richness and depth of understanding of individuals, groups, and institutions; their beliefs and perceptions; their interactions; and their challenges and issues. Writers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, advocated the use of case study as a form that teacher-researchers could use as they focused on the richness and intensity of their own practices. In addition, academic writers and postgraduate students embraced case study as a means of providing structure and depth to educational projects. However, as educational research has developed, so has debate on the quality and usefulness of case study as well as the problems surrounding the lack of generalizability when dealing with single or even multiple cases. The question of how to define and support case study work has formed the basis for innumerable books and discursive articles, starting with Robert Yin’s original book on case study ( Yin 1984 , cited under General Overview and Foundational Texts of the Late 20th Century ) to the myriad authors who attempt to bring something new to the realm of case study in educational research in the 21st century.

This section briefly considers the ways in which case study research has developed over the last forty to fifty years in educational research usage and reflects on whether the field has finally come of age, respected by creators and consumers of research. Case study has its roots in anthropological studies in which a strong ethnographic approach to the study of peoples and culture encouraged researchers to identify and investigate key individuals and groups by trying to understand the lived world of such people from their points of view. Although ethnography has emphasized the role of researcher as immersive and engaged with the lived world of participants via participant observation, evolving approaches to case study in education has been about the richness and depth of understanding that can be gained through involvement in the case by drawing on diverse perspectives and diverse forms of data collection. Embracing case study as a means of entering these lived worlds in educational research projects, was encouraged in the 1970s and 1980s by researchers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, who provided a helpful impetus for case study work in education ( Stenhouse 1980 ). Stenhouse wrestled with the use of case study as ethnography because ethnographers traditionally had been unfamiliar with the peoples they were investigating, whereas educational researchers often worked in situations that were inherently familiar. Stenhouse also emphasized the need for evidence of rigorous processes and decisions in order to encourage robust practice and accountability to the wider field by allowing others to judge the quality of work through transparency of processes. Yin 1984 , the first book focused wholly on case study in research, gave a brief and basic outline of case study and associated practices. Various authors followed this approach, striving to engage more deeply in the significance of case study in the social sciences. Key among these are Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 , along with Yin 1984 , who established powerful groundings for case study work. Additionally, evidence of the increasing popularity of case study can be found in a broad range of generic research methods texts, but these often do not have much scope for the extensive discussion of case study found in case study–specific books. Yin’s books and numerous editions provide a developing or evolving notion of case study with more detailed accounts of the possible purposes of case study, followed by Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 who wrestled with alternative ways of looking at purposes and the positioning of case study within potential disciplinary modes. The authors referenced in this section are often characterized as the foundational authors on this subject and may have published various editions of their work, cited elsewhere in this article, based on their shifting ideas or emphases.

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This is Merriam’s initial text on case study and is eminently accessible. The author establishes and reinforces various key features of case study; demonstrates support for positioning the case within a subject domain, e.g., psychology, sociology, etc.; and further shapes the case according to its purpose or intent.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Stake is a very readable author, accessible and yet engaging with complex topics. The author establishes his key forms of case study: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Stake brings the reader through the process of conceptualizing the case, carrying it out, and analyzing the data. The author uses authentic examples to help readers understand and appreciate the nuances of an interpretive approach to case study.

Stenhouse, L. 1980. The study of samples and the study of cases. British Educational Research Journal 6:1–6.

DOI: 10.1080/0141192800060101

A key article in which Stenhouse sets out his stand on case study work. Those interested in the evolution of case study use in educational research should consider this article and the insights given.

Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE.

This preliminary text from Yin was very basic. However, it may be of interest in comparison with later books because Yin shows the ways in which case study as an approach or method in research has evolved in relation to detailed discussions of purpose, as well as the practicalities of working through the research process.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender, Power and Politics in the Academy

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Nonformal and Informal Environmental Education

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.148.24.167]

- 185.148.24.167

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Using Case Study in Education Research

- Lorna Hamilton - University of Edinburgh, UK

- Connie Corbett-Whittier - Friends University, Topeka, Kansas

- Description

This book provides an accessible introduction to using case studies. It makes sense of literature in this area, and shows how to generate collaborations and communicate findings.

The authors bring together the practical and the theoretical, enabling readers to build expertise on the principles and practice of case study research, as well as engaging with possible theoretical frameworks. They also highlight the place of case study as a key component of educational research.

With the help of this book, graduate students, teacher educators and practitioner researchers will gain the confidence and skills needed to design and conduct a high quality case study.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

'Drawing on a wide range of their own and others' experiences, the authors offer a comprehensive and convincing account of the value of case study in educational research. What comes across - quite passionately - is the way in which a case study approach can bring to life some of the complexities, challenges and contradictions inherent in educational settings. The book is written in a clear and lively manner and should be an invaluable resource for those teachers and students who are incorporating a case study dimension into their research work' - Ian Menter, Professor of Teacher Education, University of Oxford

'This book is comprehensive in its coverage, yet detailed in its exposition of case study research. It is a highly interactive text with a critical edge and is a useful tool for teaching. It is of particular relevance to practitioner researchers, providing accessible guidance for reflective practice. It covers key matters such as: purposes, ethics, data analysis, technology, dissemination and communities for research. And it is a good read!' - Professor Anne Campbell, formerly of Leeds Metropolitan University

'This excellent book is a principled and theoretically informed guide to case study research design and methods for the collection, analysis and presentation of evidence' -Professor Andrew Pollard, Institute of Educaiton, University of London

This publication provides easy text, giving differing viewpoints to establish definitions for case study research. This book has been recommended to the Fd students to support projects of action research.

This has again been recommended for students on the Foundation Degree and Degree programmes as it is an easy text, providing differing viewpoints to establish definitions for case study research. Additionally recommended on the reading list for the BA programmes to provide a clearer insight into using Case Studies in preschool and school environments.

This is an excellent book - very clear

This text clearly discusses the case study approach and would be useful for both undergraduate and post graduate learners.

An easily accessible text, giving alternative points of view on what case study research actually is and how it might be interpreted at doctoral level.

This is a pleasant read with a number of useful group and individual tasks for students to engage with as they think through designing and doing a project. These tasks for useful not just for case studies but can be adapted as students consider other research designs.

Offers a good understanding of case study research in a clear and accessible manner. A perfect starting point for the researcher new to the case study method and will also offer the experienced researcher some useful tips and insights.

This text is clearly written and argues strongly for using case study in educational research, despite the challenges this approach faces in the dynamic world of shifting research paradigms. Step-by-step guidance from initial ideas through to the reality of undertaking case study in educational research is helpful

The book is written in a practical way, which gives a clear guide for undergraduate students especially for those who are using case study in education research. I will definitely add this book to recommended reading lists.

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Additional Resource 1

Additional Resource 2

Sample Chapter - Chapter 1

Activity 6.12 Observation 1 p98

Activity 6.12 Observation 2 p98

Activity 6.12 Observation 3 p98

Activity 6.18 Interview pupils

Activity 6.18 Interview schedule 1

Activity 6.19 and 6.20 Questionnaire P110

Activity 6.20 Questionnaire 2 p110

Activity 6.21 Sample interview teachers

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Research Guides

Case Studies

Dee Degner; Amani Gashan; and Natalia Ramirez Casalvolone

Description

Creswell and Poth (2018) define case study as a strategy that involves the study of an issue explored through one or more cases within a bounded system (i.e., a setting or a context), a methodology, a type of design in qualitative research, or an object of study, as well as a product of the inquiry.

Flyvbjerg (2011) defines case study as an intensive analysis of an individual unit (as a person or community) stressing developmental factors in relation to the environment. Case study methodology aims to describe one or more cases in depth. It examines how something may be occurring in a given case or cases and typically uses multiple data sources to gather information. Creswell and Poth also argue that the use of different sources of information is to provide depth to the case description. Case study methodology aims to describe one or more cases in depth. It examines how something may be occurring in a given case or cases and typically uses multiple data sources to gather the information. This is the first step of data analysis in a qualitative case study. Following this, researchers must decide whether there is a case study to analyze, determine the boundaries of their case study and its context, decide whether they wish to use single or multiple case studies, and explore approaches to analyzing themes and articulating findings. Creswell and Poth (2018) are an ideal resource for defining case study, learning about its parts, and executing case study methodology.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research: choosing among five approaches (4th ed.) . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. In N. K. Denzin, & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 301-316 ). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Key Research Books and Articles on Case Study Methodology

Ashley, L. D. (2017). Case study research. In R. Coe, M. Waring, L. Hedges & J. Arthur (Eds), Research methods & methodologies in education (2nd ed., pp. 114-121). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

This edited text discusses several research methods in education. Dr. Laura Day Ashley, a professor at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, contributes a chapter on case study research. Using research on how private and public schools impact education in developing countries, she describes case studies and gives an example.

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qualitative Report, 13 (4), 544-559. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1573&context=tqr

The authors of this study presented an account of the qualitative case study methodology that can provide beneficial tools for researchers to explore any phenomenon under study within its context. The aim of this study was to guide novice researchers in understanding the required information for the design and implementation of any qualitative case study research project. This paper offers an account of the types of case study designs along with practical recommendations to determine the case under study, write the research questions, develop propositions, and bind the case. It also includes a discussion of data resources and the triangulation procedure in case study research.

Creswell, J. W. & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research: choosing among five approaches (4th ed.) . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

The authors are both recognized academics in the field of qualitative research; Dr. Creswell has authored many articles and 26 books on topics such as mixed-methods research, qualitative research, and research design, and Dr. Poth has written more than 30 peer reviewed journal articles and was a guest co-editor at the International Journal of Qualitative Methods. The book thoroughly reviews and compares five qualitative and inquiry designs, including research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, and case study research. Chapter 4, which is titled Five Qualitative Approaches, gives a thorough description and explanation of what a case study research contemplates. It discusses its definition and origins, its features, the types of case study procedures to follow when doing a case study, and the challenges faced during case study development. In the appendix, on page 119, the authors offer an example of a case study and a question that can be used for discussion. The entire book has pertinent information for both novice and experienced researchers in qualitative research. It covers all parts of the research process, from posing a framework to data collection, data analysis, and writing up.

Yin, R. K. (2016). Qualitative research from start to finish . New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Yin is the CEO of an applied research firm. He has authored numerous articles in many fields, including education. He also authored Case Study Research, which is now in its Sixth Edition. This book uses three approaches (practical, inductive, and adaptive) to highlight many important aspects of Qualitative Research. He provides a definition of case study and references how case study differs from other types of research.

Recent Dissertations Using Case Study Methodology

Clapp, F. N. (2017). Teachers’ and researchers’ beliefs of learning and the use of learning progressions (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 10261732)

This study from Colorado State University was designed to identify the beliefs and discourse that both the Learning Progressions (LP) developers and the intended LP implementers held around student learning, teaching, and learning progressions. The study’s research questions were examined through the use of an instrumental case study. The researchers were deliberate in applying theory and study phenomena in their context, as it investigated teachers’ practices in the context of their respective classrooms.

Applying theory to the study phenomena, this study provided insight into the relationship between LP models and teachers’ perceptions about how students learn content in a particular context. The data was collected using interviews with teachers who participated in a year-long teacher-in-residence program. Researchers and content experts who conceptualized the LP were also interviewed to study the impact that it had on participants’ perceptions of the LP and any teacher reported changes in their respective classrooms. The findings of this study inform literature on both science teacher professional development and LP’s theory to practice.

Ruiz, A. M. (2011). Teachers and English language learners experiencing the secondary mainstream classroom: A case study (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3471646)

This study from Georgia State University answered the following questions: 1) How does a secondary mainstream teacher experience the phenomenon of the inclusion of ELLs in a mainstream content area classroom? 2) How do ELLs experience the phenomenon of inclusion within the secondary mainstream content area classrooms? 3) How do the points of interaction between the secondary mainstream teacher, the English language learners, the content and the context shape the experiences of the inclusive classroom?

To comprehend the socio-constructivist learning theory which guided the design of this study, one must begin with understanding the epistemological stance of constructionism. Constructionism is seated within an interpretivist paradigm which asserts that reality does exist outside the realm of human interpretation; rather, it is human interpretation which makes meaning of this reality. The researcher applied Denzin and Lincoln’s (2004) bricoleur approach to this study, as it offered them the opportunity “to piece together a set of representations that is fitted to the specifics of this complex situation in an overlapping series of events” (p. 4). The researcher stated that his worldview shaped his research questions which called for a single case study research design.

Smith, P. H. (2000). Community as resource for minority language learning: A case study of Spanish-English dual-language schooling (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 304578045)

The author studied a school where a dual language (Spanish- English) program was being developed. He focused on the role of the community and the students’ acquisition of Spanish. Through a case study design, his theoretical framework was contemplated under the fields of language planning, language revitalization, and funds of knowledge. The author believed that minority language (Spanish) acquisition could be supported by incorporating local language resources, and in this way undermine the strong influence of the English language. To analyze his data, he went through a triangulation process of participant observation in classrooms, literacy instruction, teacher, parent and community interviews, and document and archival analysis. Findings showed that minority language resources are less often incorporated in the curriculum than those of the language majority. Thus the study suggested that these types of programs should include the funds of knowledge and available resources of the language minority communities.

Internet Resources

Graham R Gibbs. (2012, October 24). Types of Case Study. Parts 1-3 on Case Studies .

This series of videos by Graham R. Gibbs at the University of Huddersfield effectively explains case studies. Some of Gibbs’ books on qualitative research include Qualitative Data Analysis: Explorations with NVivo (2002) and Analyzing Qualitative Data (2018).

Graham R Gibbs. (2012, October 24). Types of Case Study. Part 1 on Case Studies . Retrieved from https://youtu.be/gQfoq7c4UE4

The first part of this series is an attempt to define case studies. Dr. Gibbs argued that it is a contemporary study of one person, one event, or one company. This contemporary phenomenon cab be studied in its social life context by using multiple sources of evidence.

When completing a case study, we either examine what affects our case and what effect it has on others, or we study the relationship between “the case” and between the other factors. In a typical case study approach, you choose one site to do your work and then you collect information by talking to people, using observations, interviews, or focus groups at that location. Case study is typically descriptive, meaning “you write what you see”, but it could also be exploratory or explanatory.

Types of Case Study:

- Individual case study: One single person

- Set of individual case studies: Looking at three single practices

- Community studies: Many people in one community

- Social group studies: The case representing social phenomenon “how something is defined in a social position”

- Studies of organizations and institutions: The study of “election, ford, or fielding”

- Studies of events, roles, and relationships: Family relationships

Graham R Gibbs. (2012, October 24). Planning a case study. Part 2 on Case Studies . Retrieved from https://youtu.be/o1JEtXkFAr4

The second part of this series explains how to plan a case study. Dr. Gibbs argues that when planning to conduct a case study, we should think about the conceptual framework, research questions, research design, sampling/replication strategy, methods and instruments, and analysis of data.

For any type of research, a good source of inspiration could be either from personal experiences or from talking with people about a certain topic that we can adopt.

The Conceptual Framework: Displays the important features of a case study; shows the relationships between the features; makes assumptions explicit; is selective, iterative, and based on theory; takes account of previous research; includes personal orientations, and includes overlap and inconsistency.

Research questions should:

- Be consistent with your conceptual framework.

- Cover conceptual framework.

- Be structured and focused.

- Be answerable.

- Form a basis for data collection.

Graham R Gibbs. (2012, October 24). Replication or Single Cases. Part 3 of 3 on Case Studies . https://youtu.be/b5CYZRyOlys

In the final part of the three videos of case study, Dr. Gibbs examines case study designs and variations that are possible. He also discusses replication strategies which help give the studies reliability and test to see if they can be generalized. Dr. Gibbs highlights the methods and instruments used, how to analyze the data, and concludes with problems of validity you may encounter and common pitfalls of case study research. In summary, case studies can involve gathering a lot of data and you can start analyzing the data while collecting and going through it.

shirlanne84. (2014). Different types of case study </. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/tWsnvYs9Brs

In this short video (1.49 min.), three kinds of case studies (exploratory, descriptive, and explanatory) are described, as well as rationales for using them. These rationales are as follows:

- Exploratory: If you know nothing about the case.

- Descriptive: When you write what you see, you are describing the situation.

- Explanatory: When you try to understand why things are happening, then you explain them.

Shuttleworth, M. (2008, Apr. 1). Case study research design [website]. Retrieved Feb 20, 2018 from https://explorable.com/case-study-research-design

This is a useful website that provides a guide to almost all of the research methods. It offers a clear explanation about what a case study is, the argument for and against the case study research design, how to design and conduct a case study, and how to analyze the results. This source provides a journey from the introduction of case study until the analysis of your data.

Case Studies Copyright © 2019 by Dee Degner; Amani Gashan; and Natalia Ramirez Casalvolone is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Resources Home

- All Publications

- Digital Resources

- The BERA Podcast

- Research Intelligence

- BERA Journals

- Ethics and guidance

- BERA Blog Home

- About the blog

- Blog special issues

- Blog series

- Submission policy

- Opportunities Home

- Awards and Funding

- Communities Home

- Special Interest Groups

- Early Career Researcher Network

- Events Home

- BERA Conference 2024

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Past Conferences

- BERA Membership

Resources for research

Case studies in educational research

31 Mar 2011

Dr Lorna Hamilton

To cite this reference: Hamilton, L. (2011) Case studies in educational research, British Educational Research Association on-line resource. Available on-line at [INSERT WEB PAGE ADDRESS HERE] Last accessed [insert date here]

Case study is often seen as a means of gathering together data and giving coherence and limit to what is being sought. But how can we define case study effectively and ensure that it is thoughtfully and rigorously constructed? This resource shares some key definitions of case study and identifies important choices and decisions around the creation of studies. It is for those with little or no experience of case study in education research and provides an introduction to some of the key aspects of this approach: from the all important question of what exactly is case study, to the key decisions around case study work and possible approaches to dealing with the data collected. At the end of the resource, key references and resources are identified which provide the reader with further guidance.

More related content

Resources for research 10 Apr 2024

BERA Bites 5 Mar 2024

Research Intelligence 23 Feb 2024

Reports 18 Dec 2023

BERA in the news 19 Apr 2024

News 19 Mar 2024

BERA in the news 14 Mar 2024

News 7 Mar 2024

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. Professor at Harvard Business School and the former dean of HBS.

Partner Center

Case-Study Instruction in Educational Psychology: Implications for Teacher Preparation

- First Online: 01 January 2014

Cite this chapter

- Alyssa R. Gonzalez-DeHass 6 &

- Patricia P. Willems 6

Part of the book series: New Frontiers of Educational Research ((NFER))

2300 Accesses

3 Citations

Case-study instruction has become increasingly popular as a way for preprofessional teachers to actively engage in problem-solving for real-life classroom situations. Case-study activity allows for social dialog and exploration in an atmosphere of shared learning among peers and instructor, and it also affords prospective teachers the opportunity to see how a teacher works jointly with other stakeholders such as the school principal, guidance counselor, and students and their parents in order to assist a student’s academic learning. Benefits associated with this method of teaching include preservice teachers gaining an appreciation for the complexities involved in teaching, opportunities for scaffolding of critical thinking skills, students being involved in authentic learning experiences in teacher decision-making, and student motivation to learn academic content. The chapter also includes suggestions for instructors in teacher preparation programs wishing to successfully incorporate case-study instruction into their classrooms.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alesandrini, K., & Larson, L. (2002). Teachers bridge to constructivism. The Clearing House, 75 (3), 118–121.

Article Google Scholar

Ames, C. (1984). Achievement attributions and self-instructions under competitive and individualistic goal structures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76 , 478–487.

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80 (3), 260–267.

Archer, J. (1994). Achievement goals as a measure of motivation in university students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19 , 430–446.

Aspy, D. N., Aspy, C. B., & Quinby, P. M. (1993). What doctors can teach teachers about problem-based learning. Educational Leadership, 50 (7), 22–25.

Google Scholar

Barnett, M. (2008). Using authentic cases through a web-based professional development system to support preservice teachers in examining classroom practice. Action in Teacher Education, 29 (4), 3–14.

Bencse, L., Hewitt, J., & Pedretti, E. (2001). Multi-media case methods in preservice science education: Enabling an apprenticeship for praxis. Research in Science Education, 31 , 191–209.

Bohlin, L., Durwin, C. C., & Reese-Weber, M. (2009). EdPsych: Modules . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Bonk, C. J., & Cunningham, D. J. (1998). Searching for learner-centered, constructivist, and sociocultural components of collaborative educational learning tools. In C. J. Bonk & K. S. King (Eds.), Electronic collaborators: Learner-centered technologies for literacy, apprenticeship, and discourse . Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Bonk, J. C., Malikowski, S., Angeli, C., & East, J. (1998). Web-based case conferencing for preservice teacher education: Electronic discourse from the field. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 19 (3), 269–306.

Brooke, S. (2006). Using the case method to teach online classes: promoting Socratic dialogue and critical thinking skills. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 18 (2), 146.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18 (1), 32–42.

Bruning, R., Siwatu, K. O., Liu, X., PytlikZillig, L. M., Horn, C., Sic, S., et al. (2008). Introducing teaching cases with face-to-face and computer-mediated discussion: Two multi-classroom quasi-experiments. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33 , 299–326.

Burton, K. (2011). A framework for determining the authenticity of assessment tasks: Applied to an example in law. Journal of Learning Design, 4 (2), 20–28.

Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy Task Force on Teaching as a Profession. (1986). A Nation Prepared: Teachers for the 21st Century. Education Digest, 268 (120), 61–95.

Ching, C. P. (2011). Preservice teachers’ use of educational theories in classroom and behavior management course: A case based approach. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29 , 1209–1217.

Darling-Hammond, L., Ancess, J., & Falk, B. (1995). Authentic assessment in action: Studies of schools and students at work . New York: Teachers College Press.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Hammerness, K. (2002). Toward a pedagogy of cases in teacher education. Teaching Education, 13 (2), 125–135.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Snyder, J. (2000). Authentic assessment of teaching in context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16 , 523–545.

Day, S. L. (2002). Real kids, real risks: Effective instruction of students at risk of failure. NASSP Bulletin, 86 (632), 19–32.

DeCastro-Ambrosetti, D., & Cho, G. (2005). Synergism in learning: A critical reflection of authentic assessment. The High School Journal, 89 (1), 57–62.

DeMarco, R., Hayward, L., & Lynch, M. (2002). Nursing students’ experiences with strategic approaches to case-based instruction: A replication and comparison study between two disciplines. Journal of Nursing Education, 41 (4), 165–174.

Demetriadis, S. N., Papadopoulos, P. M., Stamelos, I. G., & Fischer, F. (2008). The effect of scaffolding students’ context-generating cognitive activity in technology-enhanced case-based learning. Computers and Education, 51 , 939–954.

Driscoll, M. P. (2005). Psychology of learning for instruction (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Driver, R., Asoko, H., Leach, J., Mortimer, E., & Scott, P. (1994). Constructing scientific knowledge in the classroom. Educational Researcher, 23 (7), 5–12.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41 , 1040–1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95 (2), 256–273.

Echeverri, J. F., & Sadler, T. D. (2011). Gaming as a platform for the development of innovative problem-based learning opportunities. Science Educator, 20 (1), 44–48.

Eggen, P., & Kauchak, D. (2009). Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice-Hall.

Engle, R. A., & Faux, R. B. (2006). Towards productive disciplinary engagement of prospective teachers in educational psychology: Comparing two methods of case-based instruction. Teaching Educational Psychology, 1 (2), 1–22.

Ennis, R. H. (2011). Twenty-one strategies and tactics for teaching critical thinking. Retrieved September 14, 2012 from http://www.criticalthinking.net/howteach.html .

Erdogan, I. & Campbell, T. (2008). Teacher questioning and interaction patterns in classrooms facilitated with differing levels of constructivist teaching practices. International Journal of Science Education, 30 (14), 1891–1914.

Fischer, C. F., & King, R. M. (1995). Authentic assessment: A guide to implementation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Furner, J. M., & Gonzalez-DeHass, A. (2011). How do students’ mastery and performance goals relate to math anxiety? Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science, and Technology Education, 7 (4), 167–182.

Gillies, R. M., & Boyle, M. (2010). Teachers’ reflection on cooperative learning: Issues of implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26 , 933–940.

Greenwood, G. E., Fillmer, H. T., & Parkay, F. W. (2002). Educational psychology cases (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice-Hall.

Grossman, R. W. (1994). Encouraging critical thinking using the case study method and cooperative learning techniques. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 5 , 7–20.

Grupe, F. H., & Jay, J. K. (2000). Incremental cases: Real-life, real-time problem solving. College Teaching, 48 (4), 123–128.

Gulikers, J. T. M., Bastiaens, T. J., & Kirschner, P. A. (2004). A five-dimensional framework for authentic assessment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 52 (3), 67–86.

Haley, M. H. (2004). Implications of using case study instruction in a foreign/second language methods course. Foreign Language Annual, 37 (2), 290–300.

Harrington, H. L. (1995). Fostering reasoned decisions: Case-based pedagogy and the professional development of teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11 (3), 203–214.

Havorson, S. J., & Wescoat, J. L. (2002). Problem-based inquiry on world water problems in large undergraduate classes. Journal of Geography, 101 (3), 91–102.

Heitzmann, R. (2008). Case study instruction in teacher education: Opportunity to develop students’ critical thinking, school smarts and decision-making. Education, 128 (4), 523–542.

Herman, W. E. (1998). Promoting pedagogical reasoning as preservice teachers analyze case vignettes. Journal of Teacher Education, 49 (5), 391–399.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16 (3), 235–266.

Hung, D. (2002). Situated cognition and problem-based learning: Implications for learning and instruction with technology. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 13 (4), 393–415.

Hushman, G. & Napper-Owen, G. (2011). Incorporating problem-based learning in physical education teacher education: Prepare new teachers to overcome real-world challenges. JOPERD–The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance , 82 (8), 17–23.

Jacobs, G. M., Power, M. A., & Inn, L. W. (2002). The teacher’s sourcebook for cooperative learning: Practical techniques, basic principles, and frequently asked questions . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Janesick, V. J. (2006). Authentic assessment primer . New York: Peter Lang.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38 (5), 365–379.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1995). Cooperative learning and individual student achievement in secondary schools. In J. E. Pedersen & A. D. Digby (Eds.), Secondary schools and cooperative learning: Theories, models, and strategies . New York: Garland.

Kaste, J. A. (2004). Scaffolding through cases: diverse constructivist teaching in the literacy methods course. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 20 (1), 31–45.

Kim, H., & Hannafin, M. J. (2008a). Situated case-based knowledge: An emerging framework for prospective teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24 , 1837–1845.

Kim, H., & Hannafin, M. J. (2008b). Grounded design of web-enhanced case-based activity. Education Tech Research Development, 56 , 161–179.

Kleinfeld, J. S. (1998). The use of case studies in preparing teachers for cultural diversity. Theory Into Practice, 37 (2), 40–147.

Kreber, C. (2001). Learning experientially through case studies? A conceptual analysis. Teaching in Higher Education, 6 (2), 217–228.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Lundeberg, M. N., & Scheurman, G. (1997). Looking twice means seeing more: Developing pedagogical knowledge through case analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13 (8), 783–797.

Mabry, L. (1999). Writing to the rubric: Lingering effects of traditional standardized testing on direct writing assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80 (9), 673–679.

Mayer, R.E. (2004). Should there be a three-strikes rule agains pure discovery learning? American Psychologist, 59 (1), 14–19.

Mayo, J. A. (2002). Case-based instruction: A technique for increasing conceptual application in introductory psychology. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 15 , 65–74.

Mayo, J. A. (2010). Constructing undergraduate psychology curricula: Promoting authentic learning and assessment in the teaching of psychology . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Merseth, K. K. (2008). Using case discussion materials to improve mathematics teaching practice. The Mathematics Educator, 11 (1), 3–20.

Moon, T. R., Brighton, C. M., Callahan, C. M., & Robinson, A. (2005). Development of authentic assessments for the middle school classroom. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 26 (2/3), 119–134.

O’Donnel, A. M., Reeve, J., & Smith, J. K. (2007). Educational psychology: Reflection for action . Danvers: Wiley.

Ormrod, J. E. (2011). Educational psychology: Developing learners (7th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Own, Z., Chen, D., & Chiang, H. (2010). A study on the effect of using problem-based learning in organic chemistry for web-based learning. International Journal of Instructional Media, 37 (4), 417–430.

Patrick, H., Anderman, L. H., Bruening, P. S., & Duffin, L. C. (2011). The role of educational psychology in teacher education: Three challenges for educational psychologists. Educational Psychologist, 46 (2), 71–83.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2001). A miniature guide for students on how to study & learn: A discipline using critical thinking concepts & tools . Dillon Beach: The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Pedersen, S., & Liu, M. (2002). The effects of modeling expert cognitive strategies during problem-based learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 26 (4), 353–380.

Powell, R. (2000). Case-based teaching in homogeneous teacher education contexts: A study of preservice teachers’ situative cognition. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16 , 389–410.

PytlikZillig, L. M., Horn, C. A., Bruning, R., Bell, S., Liu, X., Siwatu, K. O., et al. (2011). Face-to-face versus computer-mediated discussion of teaching cases: Impacts on preservice teachers’ engagement, critical analyses, and self-efficacy. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36 , 302–312.

Qin, Z., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1995). Cooperative versus competitive efforts and problem-solving. Review of Educational Research, 65 (2), 129–143.

Risko, V. J. (1991). Videodisc-based case methodology: A design for enhancing preservice teachers’ problem-solving abilities. American Reading Forum Online Yearbook, 11 , 121–137.

Rule, A. C. (2006). Editorial: The components of authentic learning. Journal of Authentic Learning, 3 (1), 1–10.

Santrock, J.W. (2011). Educational Psychology . 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Savoie, J. M., & Hughes, A. S. (1994). Problem-based learning as classroom solution: Strategies for success. Educational Leadership, 52 (3), 54–58.

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (3rd ed.). Columbus: Pearson.

Sears, S. (2003). Introduction to contextual teaching and learning. Phi Delta Kappa Fastbacks, 504 , 7–51.

Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Slavin, R. (2008). Casebook for educational psychology: Theory and practice . Upper Saddle River: Merrill/Prentice-Hall.

Slavin, R. (2009). Educational psychology: Theory and practice, instructor’s copy (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Snowman, J., & McCown, R. (2012). Psychology applied to teaching (13th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Stepien, W., & Gallagher, S. (1993). Problem-based learning: As authentic as it gets. Educational Leadership, 50 (7), 25–29.

Sudzina, M. R. (1997). Case study as a constructivist pedagogy for teaching educational psychology. Educational Psychology Review, 9 (2), 199–218.

Sungur, S., & Tekkaya, C. (2006). Effects of problem-based learning and traditional instruction on self-regulated learning. The Journal of Educational Research, 99 (5), 307–317.

Svinicki, M. D. (2005). Authentic assessment: Testing in reality. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 100 , 23–29.

Thoonen, E.E., Sleegers, P.J., Oort, F.J., Peetsma, T.T., & Geijsel, F.P. (2011). How to improve teaching practices: The role of teacher motivation, organizational factors, and leadership practices. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47 (3), 496–536.

Tuckman, B. W., & Monetti, D. M. (2011). Educational psychology . Belmont: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Vermette, P. J. (1998). Making cooperative learning work: Student teams in K-12 classrooms . Upper Saddle River: Merrill.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. (E. Hanfmann, & G. Vakar, Eds., Trans.). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment: Designing assessments to inform and improve student performance . San-Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Willems, P. P., & Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R. (2006). Educational psychology casebook . Boston: Pearson.

Woolfolk, A. (2011). Educational psychology: Active learning edition (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Wright, A. E., & Heeran, C. (2002). Utilizing case studies: Connecting the family, school, and community. School Community Journal, 12 (2), 103–115.

Yadav, A., Subedi, D., Lundeberg, M. A., & Bunting, C. F. (2011). Problem-based learning: Influence on students’ learning in an electrical engineering course. Journal of Engineering Education, 100 (2), 253–280.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, USA

Alyssa R. Gonzalez-DeHass & Patricia P. Willems

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alyssa R. Gonzalez-DeHass .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Institute of Educational Technology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Educational Methodology, Policy & Leadership, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, USA

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Gonzalez-DeHass, A.R., Willems, P.P. (2015). Case-Study Instruction in Educational Psychology: Implications for Teacher Preparation. In: Li, M., Zhao, Y. (eds) Exploring Learning & Teaching in Higher Education. New Frontiers of Educational Research. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55352-3_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55352-3_4

Published : 25 September 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-642-55351-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-642-55352-3

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Undergrad Neurosci Educ

- v.19(2); Spring 2021

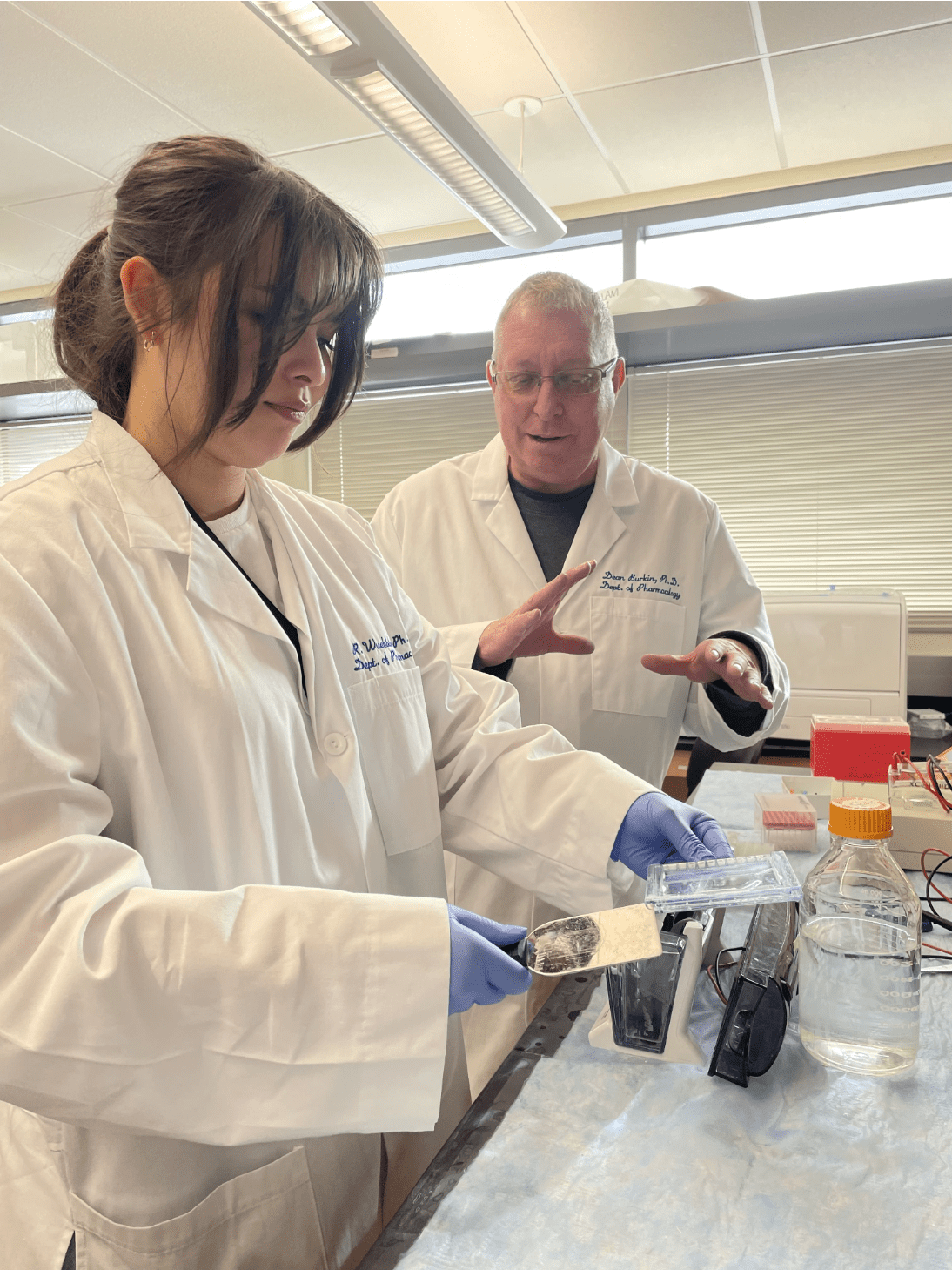

Effective Use of Student-Created Case Studies as Assessment in an Undergraduate Neuroscience Course

Dianna m. bindelli.

1 Neuroscience Department, Carthage College, Kenosha, WI 53140

Shannon A.M. Kafura

Alyssa laci, nicole a. losurdo, denise r. cook-snyder.

2 Department of Physiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee WI 53226

Case studies and student-led learning activities are both effective active learning methods for increasing student engagement, promoting student learning, and improving student performance. Here, we describe combining these instructional methods to use student-created case studies as assessment for an online neurovirology module in a neuroanatomy and physiology course. First, students learned about neurovirology in a flipped classroom format using free, open-access virology resources. Then, students used iterative writing practices to write an interrupted case study incorporating a patient narrative and primary literature data on the neurovirulent virus of their choice, which was graded as a writing assessment. Finally, students exchanged case studies with their peers, and both taught and completed the case studies as low-stakes assessment. Student performance and evaluations support the efficacy of case studies as assessment, where iterative writing improved student performance, and students reported increased knowledge and confidence in the corresponding learning objectives. Overall, we believe that using student-created case studies as assessment is a valuable, student-led extension of effective case study pedagogy, and has wide applicability to a variety of undergraduate courses.