Understanding Nursing Research

- Primary Research

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

- Experimental Design

- Is it a Nursing journal?

- Is it Written by a Nurse?

Secondary Research and Systematic Reviews

Comparative table.

- Quality Improvement Plans

Secondary Research is when researchers collect lots of research that has already been published on a certain subject. They conduct searches in databases, go through lots of primary research articles, and analyze the findings in those pieces of primary research. The goal of secondary research is to pull together lots of diverse primary research (like studies and trials), with the end goal of making a generalized statement. Primary research can only make statements about the specific context in which their research was conducted (for example, this specific intervention worked in this hospital with these participants), but secondary research can make broader statements because it compiled lots of primary research together. So rather than saying, "this specific intervention worked at this specific hospital with these specific participants, a piece of secondary research can say, "This intervention works at hospitals that serve this population."

Systematic Reviews are a kind of secondary research. The creators of systematic reviews are very intentional about their inclusion/exclusion criteria, or which articles they'll include in their review and the goal is to make a generalized statement so other researchers can build upon the practices or interventions they recommend. Use the chart below to understand the differences between a systematic review and a literature review.

Check out the video below to watch the Nursing and Health Sciences librarian describe the differences between primary and secondary research.

- "Literature Reviews and Systematic Reviews: What Is the Difference?" This article explains in depth the differences between Literature Reviews and Systematic Reviews. It is from the journal RADIOLOGIC TECHNOLOGY, Nov/Dec 2013, v. 85, #2. It is one to which Bell Library subscribes and meets copyright clearance requirements through our subscription to CCC.

- << Previous: Is it Written by a Nurse?

- Next: Permalinks >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 9:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.tamucc.edu/nursingresearch

Conducting a Literature Review: Types of Literature

- Introduction

- 1. Choose Your Topic

Types of Literature

- 3. Search the Literature

- 4. Read & Analyze the Literature

- 5. Write the Review

- Keeping Track of Information

- Style Guides

Different types of publications have different characteristics.

Primary Literature Primary sources means original studies, based on direct observation, use of statistical records, interviews, or experimental methods, of actual practices or the actual impact of practices or policies. They are authored by researchers, contains original research data, and are usually published in a peer-reviewed journal. Primary literature may also include conference papers, pre-prints, or preliminary reports. Also called empirical research .

Secondary Literature Secondary literature consists of interpretations and evaluations that are derived from or refer to the primary source literature. Examples include review articles (such as meta-analysis and systematic reviews) and reference works. Professionals within each discipline take the primary literature and synthesize, generalize, and integrate new research.

Tertiary Literature Tertiary literature consists of a distillation and collection of primary and secondary sources such as textbooks, encyclopedia articles, and guidebooks or handbooks. The purpose of tertiary literature is to provide an overview of key research findings and an introduction to principles and practices within the discipline.

Adapted from the Information Services Department of the Library of the Health Sciences-Chicago , University of Illinois at Chicago.

Types of Scientific Publications

These examples and descriptions of publication types will give you an idea of how to use various works and why you would want to write a particular kind of paper.

- Scholarly article aka empirical article

- Review article

- Conference paper

Scholarly (aka empirical) article -- example

Empirical studies use data derived from observation or experiment. Original research papers (also called primary research articles) that describe empirical studies and their results are published in academic journals. Articles that report empirical research contain different sections which relate to the steps of the scientific method.

Abstract - The abstract provides a very brief summary of the research.

Introduction - The introduction sets the research in a context, which provides a review of related research and develops the hypotheses for the research.

Method - The method section describes how the research was conducted.

Results - The results section describes the outcomes of the study.

Discussion - The discussion section contains the interpretations and implications of the study.

References - A references section lists the articles, books, and other material cited in the report.

Review article -- example

A review article summarizes a particular field of study and places the recent research in context. It provides an overview and is an excellent introduction to a subject area. The references used in a review article are helpful as they lead to more in-depth research.

Many databases have limits or filters to search for review articles. You can also search by keywords like review article, survey, overview, summary, etc.

Conference proceedings, abstracts and reports -- example

Conference proceedings, abstracts and reports are not usually peer-reviewed. A conference article is similar to a scholarly article insofar as it is academic. Conference articles are published much more quickly than scholarly articles. You can find conference papers in many of the same places as scholarly articles.

How Do You Identify Empirical Articles?

To identify an article based on empirical research, look for the following characteristics:

The article is published in a peer-reviewed journal .

The article includes charts, graphs, or statistical analysis .

The article is substantial in size , likely to be more than 5 pages long.

The article contains the following parts (the exact terms may vary): abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, references .

- << Previous: 2. Identify Databases & Resources to Search

- Next: 3. Search the Literature >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 3:04 PM

- URL: https://cob-bs.libguides.com/literaturereview

Research Basics

- What Is Research?

- Types of Research

- Secondary Research | Literature Review

- Developing Your Topic

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Additional Help

What is Secondary Research?

Secondary research, also known as a literature review , preliminary research , historical research , background research , desk research , or library research , is research that analyzes or describes prior research. Rather than generating and analyzing new data, secondary research analyzes existing research results to establish the boundaries of knowledge on a topic, to identify trends or new practices, to test mathematical models or train machine learning systems, or to verify facts and figures. Secondary research is also used to justify the need for primary research as well as to justify and support other activities. For example, secondary research may be used to support a proposal to modernize a manufacturing plant, to justify the use of newly a developed treatment for cancer, to strengthen a business proposal, or to validate points made in a speech.

The following guides, published by the library, offer more information on how to do secondary research or a literature review:

- << Previous: Types of Research

- Next: Developing Your Topic >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 3:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/research_basics

- Library Guides

The Literature Review

Primary and secondary sources, the literature review: primary and secondary sources.

- Searching the literature

- Grey literature

- Organising and analysing

- Systematic Reviews

- The Literature Review Toolbox

On this page

- Primary vs secondary sources: The differences explained

Can something be both a primary and secondary source?

Research for your literature review can be categorised as either primary or secondary in nature. The simplest definition of primary sources is either original information (such as survey data) or a first person account of an event (such as an interview transcript). Whereas secondary sources are any publshed or unpublished works that describe, summarise, analyse, evaluate, interpret or review primary source materials. Secondary sources can incorporate primary sources to support their arguments.

Ideally, good research should use a combination of both primary and secondary sources. For example, if a researcher were to investigate the introduction of a law and the impacts it had on a community, he/she might look at the transcripts of the parliamentary debates as well as the parliamentary commentary and news reporting surrounding the laws at the time.

Examples of primary and secondary sources

Primary vs secondary sources: The differences explained

Finding primary sources

- VU Special Collections - The Special Collections at Victoria University Library are a valuable research resource. The Collections have strong threads of radical literature, particularly Australian Communist literature, much of which is rare or unique. Women and urban planning also feature across the Collections. There are collections that give you a picture of the people who donated them like Ray Verrills, John McLaren, Sir Zelman Cowen, and Ruth & Maurie Crow. Other collections focus on Australia's neighbours – PNG and Timor-Leste.

- POLICY - Sharing the latest in policy knowledge and evidence, this database supports enhanced learning, collaboration and contribution.

- Indigenous Australia - The Indigenous Australia database represents the collections of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Library.

- Australian Heritage Bibliography - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Subset (AHB-ATSIS) - AHB is a bibliographic database that indexes and abstracts articles from published and unpublished material on Australia's natural and cultural environment. The AHB-ATSIS subset contains records that specifically relate to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.include journal articles, unpublished reports, books, videos and conference proceedings from many different sources around Australia. Emphasis is placed on reports written or commissioned by government and non-government heritage agencies throughout the country.

- ATSIhealth - The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Bibliography (ATSIhealth), compiled by Neil Thomson and Natalie Weissofner at the School of Indigenous Australian Studies, Kurongkurl Katitjin, Edith Cowan University, is a bibliographic database that indexes published and unpublished material on Australian Indigenous health. Source documents include theses, unpublished articles, government reports, conference papers, abstracts, book chapters, books, discussion and working papers, and statistical documents.

- National Archive of Australia - The National Archives of Australia holds the memory of our nation and keeps vital Australian Government records safe.

- National Library of Australia: Manuscripts - Manuscripts collection that is wide ranging and provides rich evidence of the lives and activities of Australians who have shaped our society.

- National Library of Australia: Printed ephemera - The National Library has been selectively collecting Australian printed ephemera since the early 1960s as a record of Australian life and social customs, popular culture, national events, and issues of national concern.

- National Library of Australia: Oral history and folklore - The Library’s Oral History and Folklore Collection dates back to the 1950’s and includes a rich and diverse collection of interviews and recordings with Australians from all walks of life.

- Historic Hansard - Commonwealth of Australia parliamentary debates presented in an easy-to-read format for historians and other lovers of political speech.

- The Old Bailey Online - A fully searchable edition of the largest body of texts detailing the lives of non-elite people ever published, containing 197,745 criminal trials held at London's central criminal court.

Whether or not a source can be considered both primary and secondary, depends on the context. In some instances, material may act as a secondary source for one research area, and as a primary source for another. For example, Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince , published in 1513, is an important secondary source for any study of the various Renaissance princes in the Medici family; but the same book is also a primary source for the political thought that was characteristic of the sixteenth century because it reflects the attitudes of a person living in the 1500s.

Source: Craver, 1999, as cited in University of South Australia Library. (2021, Oct 6). Can something be a primary and secondary source?. University of South Australia Library. https://guides.library.unisa.edu.au/historycultural/sourcetypes

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Searching the literature >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 2:06 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.vu.edu.au/the-literature-review

Tutorial: Evaluating Information: Peer Review

- Evaluating Information

- Scholarly Literature Types

- Primary vs. Secondary Articles

- Peer Review

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analysis

- Gray Literature

- Evaluating Like a Boss

- Evaluating AV

Types of scholarly literature

You will encounter many types of articles and it is important to distinguish between these different categories of scholarly literature. Keep in mind the following definitions.

Peer-reviewed (or refereed): Refers to articles that have undergone a rigorous review process, often including revisions to the original manuscript, by peers in their discipline, before publication in a scholarly journal. This can include empirical studies, review articles, meta-analyses among others.

Empirical study (or primary article): An empirical study is one that aims to gain new knowledge on a topic through direct or indirect observation and research. These include quantitative or qualitative data and analysis. In science, an empirical article will often include the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.

Review article: In the scientific literature, this is a type of article that provides a synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. These are useful when you want to get an idea of a body of research that you are not yet familiar with. It differs from a systematic review in that it does not aim to capture ALL of the research on a particular topic.

Systematic review: This is a methodical and thorough literature review focused on a particular research question. It's aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making. It may involve a meta-analysis (see below).

Meta-analysis: This is a type of research study that combines or contrasts data from different independent studies in a new analysis in order to strengthen the understanding of a particular topic. There are many methods, some complex, applied to performing this type of analysis.

Peer Reviewed Article vs. Review Article

TIP : Review articles and Peer-reviewed articles are not the same thing! Review articles synthesize and analyze the results of multiple studies on a topic; peer-reviewed articles are articles of any kind that have been vetted for quality by an expert or number of experts in the field. The bibliographies of review articles can be a great source of original, peer-reviewed empirical articles.

Peer Review in Three Minutes

Watch this 3 minute intro to peer review video by North Carolina State University or read this short introduction by the University of Texas at Austin Library.

Is It Peer-Reviewed & How Can I Tell?

There are a couple of ways you can tell if a journal is peer-reviewed:

- If it's online, go to the journal home page and check under About This Journal. Often the brief description of the journal will note that it is peer-reviewed or refereed or will list the Editors or Editorial Board.

- Go to the database Ulrich's and do a Title Keyword search for the journal. If it is peer-reviewed or refereed, the title will have a little umpire shirt symbol by it.

- BE CAREFUL! A journal can be refereed/peer-reviewed and still have non-peer reviewed articles in it. Generally if the article is an editorial, brief news item or short communication, it's not been through the full peer-review process. Databases like Web of Knowledge will let you restrict your search only to articles (and not editorials, conference proceedings, etc).

Checking Peer Review in Ulrich's

Using Ulrich's Periodicals Directory to Verify Peer Review of Your Journal Title

To use this, click on the Ulrich's link to enter the database (or search for it on the main library website).

Change the Quick Search dropdown menu to Title (Keyword) and type your full journal title (not your article title or keywords) into the Quick Search box, then click Search.

This will give you a list of journal titles which includes the title you typed in. Check the Legend in the upper right corner to view the Refereed symbol ("refereed" is another term for peer-reviewed.) Then check your journal title to make sure it has the refereed symbol next to it.

NOTE: Though a journal can be peer-reviewed, letters to the editor and news reports in those same scientific journals are not! Make sure your article is a primary research article.

- Ulrich's Periodicals Directory Contains information on currently published as well as discontinued periodicals. Includes magazines, journals, newsletters, newspapers, conference proceedings, and electronic publications, together with search and browse indexes. It also contains complete names and addresses of journal publishers.

Peer reviewed articles

They both come out once every month. They're both in English. Both published in the United States. Both of them are "factual".They both have pictures. They even cover some of the same topics.

The difference is that one--Journal of Geography--is peer-reviewed, whereas National Geographic is a popular-press title.

Peer review is scientists' and other scholars' best effort to publish accurate information. Each article has been submitted by a researcher, and then reviewed by other scholars in the same field to ensure that it is sound science. What they are looking for is that:

- The methodology has been fully described (and the study can thus be replicated by another researcher)

- There are no obvious errors of calculation or statistical analysis

- Crucially: The findings support the conclusions. That is, do the results of the research support what the researcher has said about them? The classic problematic example is a scientist claiming that hair growth causes time to pass: The correlation is clearly not causation.

Things to know about peer review:

- It isn't a perfect system: Scientists make errors (or commit fraud) as often as any other human being and sometimes bad articles slip through. But in general, peer-review ensures that many trained eyes have seen an article before it appears in print.

- Peer-reviewed journals are generally considered "primary source" material: When a new scientific discovery is made, a peer-reviewed journal is often--but not always--the first place it appears.

- Popular and trade publications are not peer-reviewed, they are simply edited. That does not mean they are any less potentially truthful or informative--most popular and trade publications take pride in careful fact-checking.* But when the topic is scientific research, the information is generally "secondary" : It has already appeared elsewhere (usually in a peer-reviewed journal) and has now been "digested" for a broader audience.

- Peer-reviewed journals will always identify themselves as such. If you want to verify that a journal is peer-reviewed, check Ulrich's Periodical Directory .

Some sources of peer-reviewed articles:

- Cornell University Library homepage In particular, check the Articles & Full-Text search and then choose "Limit to articles from scholarly publications, including peer-review" at the top-left.

- Google Scholar Google Scholar takes Google's PageRank algorithm and runs it on a pre-selected set of tables-of-contents and metadata from a preselected set of scholarly journals and papers. These are largely--though not entirely--peer-reviewed. It is a much better option than a regular Google search for scholarly information.

- Web of Science Choosing "All Databases" allows you to search an index of journal articles, conference proceedings, data sets, and other resources in the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities.

- << Previous: Primary vs. Secondary Articles

- Next: Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Oct 20, 2021 11:11 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evaluate

Literature Review vs Systematic Review

- Literature Review vs. Systematic Review

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Databases and Articles

- Specific Journal or Article

Original Research Article/Primary Research Article

Parts of the Article

Sample Author Search in Google Scholar

This is a search for the author, U Fayyad. Search for your author by first initial and last name. Note the number of times the article is cited. Use SJSU GetText to retrieve the article.

- << Previous: Literature Review vs. Systematic Review

- Next: Databases and Articles >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 10:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sjsu.edu/LitRevVSSysRev

Nursing Research: Primary Vs. Secondary

- Nursing/Health Library Resources

- Primary Vs. Secondary

- Peer-Reviewed

- How to Read a Scientific Article

- Research Databases & Tutorials This link opens in a new window

- PubMed & PubMed Central

- ATI & Nursing Certifications Materials

- Google Scholar

- APA 7th Ed.

- Klinck Memorial Library Facts

- Writing Center

- CougarNet This link opens in a new window

poem / novel / letter / diary

Interview / oral history / empirical research article / case study, law / court case / census data / data set / memoir / autobiography / photographs / speeches, primary sources.

Primary sources are created by people or organizations directly involved in an issue or event. Primary sources are information before it has been analyzed by scholars, students, and others.

Some examples of primary sources:

- diaries and letters

- academic articles presenting original scientific research

- news reports from the time of the event

- literature (poems, novels, plays, etc.)

- fine art (photographs, paintings, sculpture, pottery, music, etc.)

- official records from a government, judicial court, or company

- oral histories

- autobiographies

- dissertations: while they are considered primary resources, they are NOT considered peer-reviewed

critique / anthology / scholarly review

Book / literature review / essay , analysis of data / biography / political commentary / analysis, secondary sources.

Secondary sources analyze and interpret issues and events. Secondary sources, such as scholarly articles, are typically written by experts who study a topic but are not directly involved in events themselves. Also, secondary sources are usually produced some time after an event occurs and may well contain analysis of primary sources.

Some examples of secondary sources:

- scholarly articles that analyze, review, and/or compare past research

- news reports or articles looking back at a historical event

- documentaries

- biographies

- encyclopedias

- textbooks

TIP : If you are looking at peer-reviewed articles, look at the abstract to verify if is a primary or secondary source! If the title mentions the words: review , it is likely to be secondary.

- << Previous: Nursing/Health Library Resources

- Next: Peer-Reviewed >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 1:25 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cuchicago.edu/nursing_research

Klinck Memorial Library

Concordia University Chicago 7400 Augusta Street River Forest, Illinois 60305 (708) 209-3050 [email protected] Campus Maps and Directions

- Staff Directory

- Getting Started

- Databases A-Z

- Library Catalog

- Interlibrary Loan

Popular Links

- Research Guides

- Research Help

- Request Class Instruction

© 2021 Copyright: Concordia University Chicago, Klinck Memorial Library

- Skip to main content

- assistive.skiplink.to.heading

- assistive.skiplink.to.action.menu

- assistive.skiplink.to.quick.search

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | National Institutes of Health

- Researchers

- Created by Unknown User (marchiaj) , last modified by Pauly, Kelly (NIH/OD) [E] on Mar 27, 2024

Secondary Research

What is secondary research.

Secondary research is research with specimens/data initially collected for purposes other than the planned (or primary) research. In this case, the specimens/data were collected to answer a different research question or to test a different scientific hypothesis.

Examples of secondary research vs. primary research are included in the presentation given on 1/19/2021, “ Secondary Research: Fact, Fiction, Fears and Fantasies ” that is available on the Office of Human Subjects Research Protections (OHSRP) website in the Presentation Archive .

FAQs about Secondary Research

Download this section as a PDF or click on the answers below.

1. When does secondary research not require IRB review?

There are two circumstances in which secondary research with specimens/data collected from human subjects may not require prospective IRB review.

- All the individuals from which the specimens/data were collected are deceased, AND/OR

- The specimens/data are not identifiable to the research team (see below for further discussion on this).

Subjects are all deceased

If all the individuals from whom the specimens/data were collected are now deceased, the research with these materials does not meet the definition of human subjects research and does not require prospective IRB review. However, if the specimens/data were collected under another research protocol, the terms of the original consent still apply. For example, if the consent form contained any limitations on the future use of the specimens/data, those limitations must be honored. The investigator is responsible for ensuring that any proposed research is consistent with the original consent.

Specimens/data are not identifiable to the research team

Research, with specimens/data which are not identifiable to the research team, is not considered human subjects research and does not require IRB review and approval. For example, the specimens/data have been fully anonymized by removing all identifiers, or they have been coded, and the investigator(s) conducting the research do not have access to the code key and cannot otherwise re-identify the subjects. The term “coded” means that all identifying information has been replaced with a number, letter, symbol, or combination thereof (i.e., the code) and a key to decipher the code exists, enabling linkage of the identifying information to the specimens/data. See the Guidance for Determining Whether Data Constitutes Individually Identifiable Information Under 45 CFR 46 on the OHSRP website. Investigators should consult with OHSRP if they are unsure whether data or biospecimens being used in a specific research project would be considered individually identifiable.

2. When does secondary research require IRB review?

Secondary research is considered human subjects research that requires IRB review when the specimens/data are identifiable to the researchers and were collected for another purpose than the planned research. The following is an example of secondary research:

- An investigator learns of preliminary data from a study that suggests cigarette smoking leads to specific epigenetic changes that increase susceptibility to certain infections. She also has a large number of pre-treatment samples from cigarette smokers that would be ideal to initially test this hypothesis. The specimens were collected under protocols focused on the study of lung cancer. The samples are coded, and the investigator holds the code key with identifiers. Her planned research with the specimens/data is not described in the objectives of the original lung cancer protocols. The planned activity meets the definition of secondary research because the specimens/data were collected under another protocol for a different research purpose.

Note that if the planned research is related to the existing primary, secondary, or exploratory objectives described in the IRB-approved protocol (under which the specimens/data were originally collected), then it is not considered to be secondary research. This is research that should be conducted under the primary protocol (i.e., primary research). If the investigator is unsure whether the protocol should be amended to address the planned activities or whether the current description in the protocol is adequate to allow the new research to move forward, the investigator should contact the IRB. The following is an example of a proposed activity that does not meet the definition of secondary research:

- An investigator has collected samples as part of an IRB approved phase 1 protocol to determine the maximum tolerated dose of new checkpoint inhibitor drug XYZ123 for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer refractory to standard therapies. The protocol includes an exploratory objective to determine changes in immunologic profiles of subjects receiving the drug. After the trial is already complete, the investigator decides to have all the previously stored samples analyzed for T cell subsets. Since this additional analysis meets the exploratory objective of the original protocol, the planned activities would be considered primary research.

If your research involves the use of specimens/data to test a device, please see Question 4.

3. Does my research involving de-identified specimens or data (e.g. images) and a device require IRB review and approval?

If your research involves the use of specimens or data from one or more humans to test the safety or effectiveness of an investigational medical device (e.g. AI/machine learning, in vitro diagnostic (IVD), etc.), the study is considered a clinical investigation under the FDA regulations (see 21 CFR 812.3(h)). This research likely requires creation of a protocol, prospective IRB review and approval (21 CFR 56) and a device determination and either IRB consent or waiver of consent (21 CFR 50). This is because under the FDA regulations, a human subject is not defined based on identifiability. For more information, please consult with the IRB.

4. How do I know if the secondary research I am interested in performing requires IRB review?

To determine if your planned activity with specimens/data is secondary research that will require IRB review, ask yourself the following four questions in order. If the answer to all four of these questions is “yes,” then you are performing secondary research that requires review by the IRB.

- Research (2018 Common Rule) means a systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge. (45 CFR 46.102(l))

- Clinical investigation (FDA Regulations) means any experiment that involves a test article and one or more human subjects [1] , and that either must meet the requirements for prior submission to the Food and Drug Administration under section 505(i) or 520(g) of the act, or need not meet the requirements for prior submission to the Food and Drug Administration under these sections of the act, but the results of which are intended to be later submitted to, or held for inspection by, the Food and Drug Administration as part of an application for a research or marketing permit. The term does not include experiments that must meet the provisions of part 58, regarding nonclinical laboratory studies. The terms research, clinical research, clinical study, study, and clinical investigation are deemed to be synonymous for purposes of this part. (21 CFR 56.102(c))

- Does the planned activity meet the definition human subjects research? Consider the following regulatory definitions of human subject:

- Obtains information or biospecimens through intervention or interaction with the individual, and uses, studies, or analyzes the information or biospecimens; or

- Obtains, uses, studies, analyzes, or generates identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens.

- Human Subject (FDA Regulations) means an individual who is or becomes a participant in research, either as a recipient of the test article or as a control. A subject may be either a healthy human or a patient. ( 21 CFR 50.3(g) )

- Subject (FDA regulations related it use of investigational devices) means a human who participates in an investigation, either as an individual on whom or on whose specimen an investigational device is used or as a control. A subject may be in normal health or may have a medical condition or disease. ( 812.3.(p))

3. Are you using specimens/data that were collected for other purposes (either research or non-research) for the planned research?

4. Is the planned research use of these specimens/data unrelated to the aims or objectives of the current IRB-approved protocol, under which they were originally collected?

1. Please note that the FDA considers research involving human specimens and the use of a medical device to be “clinical investigations”, if data from the research will be used to support an IDE (including IVDs), device marketing application, or another submission to the FDA. In this regard, research involving leftover human specimens that are de-identified is included.

5. What type of IRB review process is required for secondary research?

Secondary research is subject to the same regulations and reviewed using the same processes as all other human subjects research. However, depending on the specifics of the study, it may be able to be determined to be exempt from IRB review. Refer to Exempt Research on the OHSRP website.

- Exempt: Submit an exempt protocol via the electronic IRB submission system. Exempt protocol templates and instructions for submitting for an exemption are available at the link above.

- Non-exempt: Submit a secondary research protocol via the electronic IRB submission system. Non-exempt research needs to go through either an expedited or full board IRB review process. Secondary research studies are typically considered minimal risk and are usually eligible for review and approval using expedited procedures. The secondary research protocol template is available on the OHSRP website.

6. Why does my secondary research need IRB review?

Secondary research that meets the definition of human subjects research is subject to the same regulatory requirements as all other human subjects research; therefore, it must undergo IRB review. The ethical underpinning of this expectation is to assure that the proposed use of the specimens/data meets regulatory requirements and does not violate subjects’ rights. When subjects, as part of an IRB approved protocol, provided their specimens/data, it was with an understanding they would be used for a specific named purpose. IRB review of a secondary research protocol is conducted to assure that the new use is not counter to that intent nor likely to introduce new risks, not previously disclosed to the subject or considered by the IRB. The IRB will also ensure that appropriate privacy and confidentiality protections are put in place.

7. What is the IRB considering during the review process of secondary research?

The original protocol title(s) and protocol number(s) from which the specimens/data were collected, when applicable, should be listed in the new protocol. When investigators will be using existing specimens/data collected under other research protocols, the IRB will look for information about how the investigator has access to the materials. Furthermore, the new protocol must include a summary of the consent language in all applicable consent versions (for all the original protocols) as it applies to sharing and use of specimens/data for future research. This information could be provided in a table or in summary form in the protocol or the previous consent document versions could be uploaded as part of an Appendix. This will allow the IRB to review the original consent language to understand what information was conveyed to subjects about the use of their research specimens/data. Any promises made in the consent regarding sharing and the future use of specimens/data must be honored.

Some examples of circumstances that could be considered include:

- If a previous subject(s) opted out of the use of their specimens/data for future research as part of the original consent, the specimens/data should not be used as part of the secondary research.

- If the original consent stated that the specimens/data would not be used for future research or would only be used for a specific type of future research (i.e., other than what is planned for this study), then the specimens/data cannot be used for secondary research without re-consent.

- If using the specimens/data for secondary research appears consistent with the terms of the original consent, then IRB can waive consent for the secondary research.

- If consent was silent on secondary research, then IRB will consider whether the proposed use is acceptable with a waiver, or alternatively, if re-consent is required.

- Please note that under the revised Common Rule (which applies to new protocols approved on or after January 21, 2019), there are new consent requirements which could affect what is allowable within a secondary research protocol. Please see FAQ 9.

- The IRB will consider if the secondary research would impose new or significantly greater risks (including privacy risks) not described in the original consent form.

- The IRB will also consider if the study population(s) may have known concerns about the proposed secondary use. An example of this would be Native American or Alaskan Native populations who have distinct culture, beliefs and values and have concerns for potential community harms based on past abuses and violations related to clinical research. Secondary research may require additional ethical review by an Indian Health Service or Tribal IRB and permission from a tribal government.

8. Doesn’t the future use language in the original consent document allow the research team to perform broad secondary research without new IRB approval or consent?

As with all human subjects research, either the specific consent of the subject to participate in the research must be obtained, or the IRB must waive consent. The future use language in consent forms does not contain all the required elements of consent. Typically, the future use language is very broad, so it does not adequately describe the purpose of the planned study. In addition, secondary research is a new research project that the IRB has not previously reviewed, so a determination that the project meets the IRB approval criteria must be made. Any permission granted for future use is best thought of as a statement of intent by the subject, that allows the IRB to waive consent for the future use of the specimens/data for research that is compatible with the original consent.

9. Is the language about storage, use and sharing of specimens/data for future research in the current consent templates required?

Under the revised Common Rule (which applies to the consent forms associated with new protocols approved on or after January 21, 2019), the original consent form must include:

- A statement that clarifies whether or not identifiers might be removed from the data or biospecimens and that, after such removal, the information or biospecimens could be used for future research studies or distributed to another investigator for future research studies without additional informed consent

- A statement that the subject’s biospecimens (even if identifiers are removed) may be used for commercial profit and whether the subject will or will not share in this commercial profit;

- For research involving biospecimens, a statement that the research will (if known) or might include whole genome sequencing (i.e., sequencing of a human germline or somatic specimen with the intent to generate the genome or exome sequence of that specimen), if applicable.

Furthermore, for new studies approved on or after the compliance date, OHSRP advises that if the investigator intends to share coded or identifiable specimens/data for future research, there should be language in the original consent form informing the subject of this. See the current Consent Templates for Use at NIH Sites .

10. Why is the use of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ check boxes with the storage, use, and sharing for future research language in consent forms optional for some studies and not optional for others?

If the primary research protocol has therapeutic intent or a prospect of direct benefit to the subject, then agreement to unspecified future use should be optional. This is to avoid any possible coercion of subjects who wishes to participate in research that has the prospect to benefit them but who otherwise might not wish to have their specimens/data used for future unspecified research. If the primary research protocol does not have any prospect of direct benefit, then agreement to future use does not have to be optional. In other words, the team could remove the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ check boxes, and the language would then communicate that if the subject chooses to participate in the research study, then their specimens and data may be used or shared for future research.

11. Can I share specimens/data from my primary protocol with other investigators for secondary research?

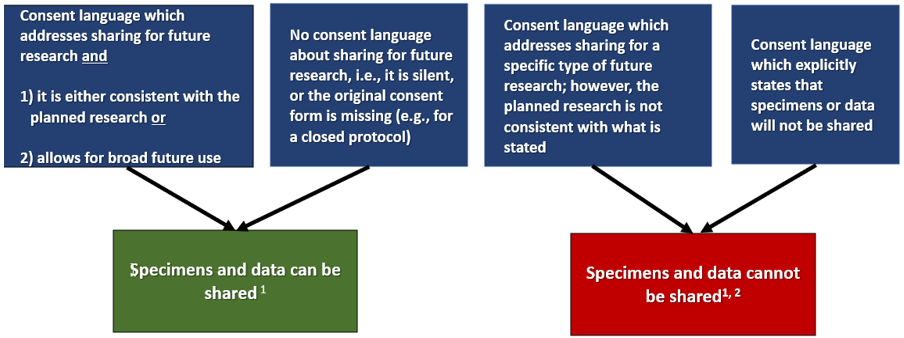

The sharing of specimens/data with other investigators does not require IRB approval per se. However, the new use of the specimens/data for research may require IRB approval. In order to share specimens/data from a protocol, the consent must allow for sharing, or at least not prohibit it. The proposed research use of the shared specimens/data should be consistent with the terms of the consent under which it was collected. Subjects agreed to participate in a specific study, not anyone's study. If the original consent says the specimens/data will never be shared, you must honor the terms of the consent. This means that the specimens/data cannot be shared even if de-identified. If you still would like to share the specimens/data, you would have to re-consent the applicable subjects with a consent document that is transparent about the plan for sharing. See the flow diagram below and FAQ 12 for examples.

In addition, please note that under the revised Common Rule (which applies to new protocols approved on or after January 21, 2019), there are new consent requirements which could limit the type of secondary research that is allowable as a result of the sharing. Please see FAQ 9.

Can I Share Specimens or Data from My IRB-Approved Protocol for Secondary Research*?

Review the consent form associated with the protocol to determine which scenario below is true. There is….

*Secondary research: research use of biospecimens or data for other than the original purpose(s) for which the biospecimens or data were initially collected through interaction or intervention with living individuals

1 If you will receive research results that you can link back to identifiers after sharing specimens or data, the project is considered to be human subjects research . You must submit a secondary research protocol to address the planned research and seek IRB approval prior to initiation of the activities. The protocol must include new consent or a justification of a waiver of consent for the planned research.

2 In some circumstances, it may be appropriate to re-consent the subject to allow their specimens and data to be shared. Consult the IRB if you wish to proceed with sharing.

12. When might I need IRB approval to share specimens/data?

If the terms of the original consent prohibit sharing, then you should consult with the IRB to determine if there is a path forward. If the IRB provides guidance that sharing might be allowed, they will require you to re-consent subjects prior to any sharing.

The other situation in which you should seek IRB approval is if you are getting identifiable results/data returned to you from your collaborator, and the research is not described in the primary protocol. In this case, you are considered to be conducting new secondary research yourself. In other words, if you are sharing coded specimens (for which you have the code key) with an investigator who does not have the code key, and you are getting individual level data back (not aggregate data), this is human subjects research. The rationale is that you are receiving new information about your subjects that you can link back to identifiers. This activity needs IRB approval not because the specimens are being shared, but because identifiable data is being returned to the NIH research team that will be used for research.

Note that if you are only sharing or collaborating in research involving specimens/data for which the NIH research team has no access to identifiers or the ability to re-identify, this is not considered to be human subjects research. Furthermore, the investigator does not need to submit for a request for determination of "not human subjects research" as was required in the past.

If you wish to share or receive human biospecimens and/or human data outside NIH under a Material Transfer Agreement, a Data Transfer/Use Agreement or a Research Collaborator Agreement, an Investigator Attestation must be completed and provided to the appropriate Tech Transfer contact. Please see NIH Tech Transfer on the OHSRP website for more details and a copy of this document .

13. What are some examples of language in the primary protocol consent that would prohibit the sharing of specimens/data and disallow them to be used in secondary research?

Sharing and secondary research with existing specimens/data must comply with the terms of the original informed consent document. Researchers are expected to review all previous versions of the consent form to determine who consented to what. If the original consent form addresses the use and sharing of specimens/data for future research, the new plan for sharing and research should be consistent with the language in the original consent document. If there is language in the original consent form which is contrary to sharing or future research generally or conflicts with the specific sharing and research plan, the investigator cannot proceed. This is true, even if the specimens/data are being used or shared in a de-identified manner, or if the subjects are deceased.

Some examples of prohibitive or restrictive language include:

- “Your specimens will be destroyed at the end of this study.” These means the specimens cannot be stored for future research.

- “Your specimens/data will be used for future research on cancer.” This would restrict any secondary research to only cancer-related research.

- If some subjects opt-out of future research with specimens/data by checking a box in the consent, then the NIH investigator must track this information over time. Failing to check any box is considered the same as not agreeing, i.e., opting out of future research.

- “Your data will never be shared outside of the NIH.” This would restrict the use to only NIH investigators. You would not be able to share even de-identified specimens/data outside of NIH.

- “Your data will never be shared outside of the NIH research team working on the protocol.” This would restrict the use to only the NIH research team members named on the primary protocol.

If the initial consent contained restrictive language and you wish to be able to do future research or share the specimens/data, consult with the IRB. Depending on the type of limitations, the IRB may require you to re-consent the subjects to allow the sharing or research to go ahead. After that point, the specimens/data, of those that provide consent, would now be able to be used.

14. What if the original consent document did not ask subjects’ permission to use their data and specimens for secondary research?

If the original consent form (for new protocols approved before January 21, 2019) was silent on the topic of sharing and future research, then IRB will consider whether the proposed use is acceptable with a waiver or if re-consent is required.

Per the revised Common Rule (for new protocols approved on or after January 21, 2019), there are new consent requirements which affect what is allowable as part of secondary research. Please see FAQ 9.

Furthermore, for protocols approved on or after the revised Common Rule implementation date, OHSRP advises that if the investigator intends to use coded or identifiable specimens/data for future research, there should be language in the consent form informing the subject of this. See the current Consent Templates for Use at NIH Sites .

15. If the primary consent document allows sharing, what is the next step to be able to perform secondary research?

Consent to use specimens/data for future research is not sufficient to allow the investigator to move forward with secondary research with identifiable specimens/data. This type of consent language simply allows the investigator to store the materials for future research (or use the materials once completely anonymized (stripped of all identifiers)). If the investigator will conduct new research using existing identifiable specimens/data, generally they are expected to submit a new research protocol and seek IRB approval.

16. What is a waiver of consent?

A waiver of consent is when the requirement to obtain informed consent for research is formally waived by the IRB. The waiver applies to the proposed research activity, not to the sharing of specimens/data. The IRB will consider whether the proposed use is consistent with the terms of the original consent and whether there are any new risks. If the conditions described below in the next FAQ are met, then the IRB may grant the waiver. The IRB will not grant a waiver that is counter to the terms of the original consent, nor can the IRB grant a waiver for broad, unspecified future use.

17. What are the criteria for being granted a waiver of consent?

When requesting a waiver for a research protocol being reviewed and approved on or after January 21, 2019, address and provide justification in the protocol for the following specific regulatory criteria:

- Example of a justification: The only risk to subjects is a possible breach of confidentiality.

- Example of a justification: The required number of specimens to conduct the research is so large that it would impede scientific validity and introduce bias if only those who were willing to consent were included.

- Example of a justification: Many of the subjects are lost to follow-up, or the research team has not been in contact with them for many years.

- Example of a justification: The research involves specimens and different types of data (medical records, imaging, lab results) that all must be linked together by a subject identifier to allow analysis.

- Example of a justification: Conducting the planned research with existing specimens/data (originally collected under informed consent) will not cause any harm to subjects.

- Example of a justification: We do not intend to contact subjects to share the results of our research.

- Example of a justification: The results of this research will not generate new clinically actionable findings.

18. Do I have to keep my primary protocol open, so that I can keep the identifiable specimens/data for future secondary research?

No. Identifiable specimens/data can be stored even after the primary protocol is closed; you do not have to discard or de-identify them. The primary protocol must only remain open if you are using the specimens/data for research purposes described in the protocol. The specimens/data can be stored unused until there is approval of a secondary research protocol. However, although it is permissible to store them, you cannot access or use the identifiable specimens/data for research without an IRB-approved protocol in place.

19. Instead of submitting a secondary research protocol, can I just amend the primary protocol to include my new research objective(s)?

If the proposed research is directly related to the primary protocol’s aims/objectives, then you can consider adding the new research to the primary protocol. However, if the new project is unrelated to the primary protocol’s aims/objectives, it would be considered new research and needs to be submitted as its own protocol. A protocol needs to be cohesive, and disconnected ideas and experiments are not considered approvable research.

20. Is guidance available for writing a protocol for secondary research?

The OHSRP website has templates to guide you in writing your secondary research protocol.

- There is a secondary research protocol template under the Observational Research Protocol Templates section on the OHSRP website. This template should be used for non-exempt research.

- If you think your secondary research may be exempt, refer to the protocol template for retrospective data or biospecimen review on the OHSRP website.

- The protocol template includes information about what types of secondary projects are eligible for an exemption. The webpage also includes instructions that will help guide you through requesting an exemption in the electronic system.

21. What if I anticipate having future research questions, and I would like to collect new specimens/data or retain existing specimens/data in a repository?

A repository is an organized system to collect, maintain and store specimens/data, most often for future research use. The materials may be prospectively collected from humans for inclusion in a repository, or the repository may house existing materials originally collected for other purposes, including non-research purposes. Repositories can also be referred to as registries, data banks, databases, or biobanks.

Repositories that are designed to prospectively collect specimens/data from humans for research purposes and/or to maintain and distribute specimens/data (that are linked to identifiers) to researchers must have IRB approval and oversight. Accordingly, a repository protocol should first be submitted for IRB review. The repository protocol itself generally does not describe the details of the secondary research. Any secondary research involving the identifiable specimens/data from the repository would require submission of a separate protocol to the IRB. Another option would be for the investigator conducting the secondary research to receive all of the specimens and data in an anonymized or coded and linked format, with no access to the code key. In this case, the investigator(s) overseeing the repository protocol would be acting as an “honest broker” and either permanently anonymize the specimens and data before sharing them or coding them and maintaining the code key, so that only they are in a position to re-link to the original identifiers.

22. Is guidance available for writing a repository protocol?

There is a repository protocol template on the OHSRP website under the Observational Research Protocol Templates.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

Primary versus secondary source of data in observational studies and heterogeneity in meta-analyses of drug effects: a survey of major medical journals

Guillermo prada-ramallal.

1 Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Santiago de Compostela, c/ San Francisco s/n, 15786 Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain

2 Health Research Institute of Santiago de Compostela (Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela - IDIS), Clinical University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Fatima Roque

3 Research Unit for Inland Development, Polytechnic of Guarda (Unidade de Investigação para o Desenvolvimento do Interior - UDI/IPG), 6300-559 Guarda, Portugal

4 Health Sciences Research Centre, University of Beira Interior (Centro de Investigação em Ciências da Saúde - CICS/UBI), 6200-506 Covilhã, Portugal

Maria Teresa Herdeiro

5 Department of Medical Sciences & Institute for Biomedicine – iBiMED, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

6 Higher Polytechnic & University Education Co-operative (Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Politécnico e Universitário - CESPU), Institute for Advanced Research & Training in Health Sciences & Technologies, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal

Bahi Takkouche

7 Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology & Public Health (CIBER en Epidemiología y Salud Pública – CIBERESP), Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Adolfo Figueiras

Associated data.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

The data from individual observational studies included in meta-analyses of drug effects are collected either from ad hoc methods (i.e. “primary data”) or databases that were established for non-research purposes (i.e. “secondary data”). The use of secondary sources may be prone to measurement bias and confounding due to over-the-counter and out-of-pocket drug consumption, or non-adherence to treatment. In fact, it has been noted that failing to consider the origin of the data as a potential cause of heterogeneity may change the conclusions of a meta-analysis. We aimed to assess to what extent the origin of data is explored as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of observational studies.

We searched for meta-analyses of drugs effects published between 2012 and 2018 in general and internal medicine journals with an impact factor > 15. We evaluated, when reported, the type of data source (primary vs secondary) used in the individual observational studies included in each meta-analysis, and the exposure- and outcome-related variables included in sensitivity, subgroup or meta-regression analyses.

We found 217 articles, 23 of which fulfilled our eligibility criteria. Eight meta-analyses (8/23, 34.8%) reported the source of data. Three meta-analyses (3/23, 13.0%) included the method of outcome assessment as a variable in the analysis of heterogeneity, and only one compared and discussed the results considering the different sources of data (primary vs secondary).

Conclusions

In meta-analyses of drug effects published in seven high impact general medicine journals, the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is underexplored as a source of heterogeneity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12874-018-0561-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Specific research questions are ideally answered through tailor-made studies. Although these ad hoc studies provide more accurate and updated data, designing a completely new project may not represent a feasible strategy [ 1 , 2 ]. On the other hand, clinical and administrative databases used for billing and other fiscal purposes (i.e. “secondary data”) are a valuable resource as an alternative to ad hoc methods (i.e. “primary data”) since it is easier and less costly to reuse the information than collecting it anew [ 3 ]. The potential of secondary automated databases for observational epidemiological studies is widely acknowledged; however, their use is not without challenges, and many quality requirements and methodological pitfalls must be considered [ 4 ].

Meta-analysis represents one of the most valuable tools for assessing drug effects as it may lead to the best evidence possible in epidemiology [ 5 ]. Consequently, its use for making relevant clinical and regulatory decisions on the safety and efficacy of drugs is dramatically increasing [ 6 ]. Existence of heterogeneity in a given meta-analysis is a feature that needs to be carefully described by analyzing the possible factors responsible for generating it [ 7 ]. In this regard, the results of a recent study [ 8 ] show that whether the origin of the data (primary vs secondary) is explored as a potential cause of heterogeneity may change the conclusions of a meta-analysis due to an effect modification [ 9 ]. Thus, considering the source of data as a variable in sensitivity and subgroup analyses, or meta-regression analyses, seems crucial to avoid misleading conclusions in meta-analyses of drug effects.

Given the evidence noted [ 8 , 9 ], we surveyed published meta-analyses in a selection of high-impact journals over a 6-year period, to assess to what extent the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is explored as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of observational studies.

Meta-analysis selection and data collection process

General and internal medicine journals with an impact factor > 15 according to the Web of Science were included in the survey [ 10 ]. This method has been widely used to assess quality as well as publication trends in medical journals [ 11 – 13 ]. The rationale is that meta-analyses published in high impact journals: (1) are likely to be rigorously performed and reported due to the exhaustive editorial process [ 12 , 14 ]; and, (2) in general, exert a higher influence on medical practice due to the major role played by these journals in the dissemination of the new medical evidence [ 14 , 15 ]. We searched MEDLINE on May 2018 using the search terms “meta-analysis” as publication type and “drug” in any field between January 1, 2012 and May 7, 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine ( NEJM ), Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association ( JAMA) , British Medical Journal ( BMJ ), JAMA Internal Medicine (JAMA Intern Med) , Annals of Internal Medicine ( Ann Intern Med ), and Nature Reviews Disease Primers (Nat Rev Dis Primers) .

Two investigators (GP-R, FR) independently assessed publications for eligibility. Abstracts were screened and if deemed potentially relevant, full text articles were retrieved. Articles were excluded if they met any of the following conditions: (1) were not a meta-analysis of published studies, (2) no drug effects were evaluated, (3) only randomized clinical trials were included in the meta-analysis (in order to consider observational studies), (4) less than two observational studies were included in the meta-analysis (since with a single study it would not have been possible to calculate a pooled measure). When a meta-analysis included both observational studies and clinical trials, only observational studies were considered.

A data extraction form was developed previously to extract information from articles. Two investigators (GP-R, FR) independently extracted and recorded the information and resolved discrepancies by referring to the original report. If necessary, a third author (AF) was asked to resolve disagreements between the investigators.

When available we extracted the following data from each eligible meta-analysis: first author, publication year, journal, drug(s) exposure and outcome(s); number of individual studies included in the meta-analysis based on each type of data source used (primary vs secondary), for both exposure and outcome assessment; and exposure- and outcome-related variables included in sensitivity, subgroup or meta-regression analyses. We extracted data directly from the tables, figures, text, and supplementary material of the meta-analyses, not from the individual studies.

Assessment of exposure and outcome

We considered “primary data” the information on drug exposure collected directly by the researchers using interviews –personal or by telephone– or self-administered questionnaires. The origin of the data was also considered primary when objective diagnostic methods were used for the determination of drug exposure (e.g. blood test). “Secondary data” are data that were formerly collected for other purposes than that of the study at hand and that were included in databases on drug prescription (e.g. prescription registers, medical records/charts) and dispensing (e.g. computerized pharmacy records, insurance claims databases). Regarding the outcome assessment, we considered primary data when an objective confirmation is available that endorses them (e.g. confirmed by individual medical ad hoc diagnosis, lab test or imaging results). These criteria are based on those commonly used in the risk assessment of bias for observational studies [ 16 – 19 ].

MEDLINE search results yielded 217 articles from the major general medical journals (3 from NEJM , 46 from Lancet , 26 from JAMA , 85 from BMJ , 19 from JAMA Intern Med, 38 from Ann Intern Med, and 0 from Nat Rev Dis Primers ) (see Fig. Fig.1). 1 ). A total of 194 articles were excluded (see list of excluded articles with reasons for exclusion in Additional file 1 ) leaving 23 articles to be examined [ 20 – 42 ]. General characteristics of the 23 included meta-analyses are outlined in Table Table1 1 .

Flow diagram of literature search results

Characteristics of the 23 included meta-analyses

Abbreviations : AABs antibodies against biologic agents, ACEIs , angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, Ann Intern Med Annals of Internal Medicine , ARBs angiotensin receptor blockers, BMJ British Medical Journal , DPP-4 Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4, GLP-1 glucagon like peptide-1, JAMA Journal of the American Medical Association , MIC minimum inhibitory concentration, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SGLT-2 sodium–glucose cotransporter 2, SSRIs selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Source of exposure and outcome data

Table Table2 2 summarizes the evidence regarding the type of data source included in each meta-analysis, according to the information presented in the data extraction tables of the article. The information was evaluated taking the study design into account. Only eight meta-analyses [ 21 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 38 , 41 ] reported the source of data, three of them [ 31 , 34 , 38 ] reporting mixed sources for both the exposure and outcome assessment. Five meta-analyses [ 21 , 24 , 26 , 32 , 41 ] reported only secondary sources for the exposure assessment, three of them [ 21 , 24 , 41 ] reporting as well only secondary sources for the outcome assessment, while in the other two [ 26 , 32 ] only primary and mixed sources for the outcome assessment were reported respectively.

Reporting of the data source in the data extraction tables of the included meta-analyses

Abbreviations : 1ry number of individual studies in each MA based on primary data sources, 2ry number of individual studies in each MA based on secondary data sources, NR number of individual studies in each MA with not reported data source

a Although the meta-analysis shows the results of methodological quality assessment based on a standardized scale, it does not indicate the type of data source used for each individual observational study included in the meta-analysis

b Cohort with nested case-control analysis

c The meta-analysis reports that most of the included observational studies assessed medication exposure through a review of medical records

d The meta-analysis reports only data from high-quality observational studies

Source of data in the analysis of heterogeneity

All but two [ 20 , 42 ] of the meta-analyses performed subgroup and/or sensitivity analyses. Although three of them [ 23 , 34 , 36 ] considered the methods of outcome assessment – type of diagnostic assay used for Clostridium difficile infection, method of venous thrombosis diagnosis confirmation, and type of scale for psychosis symptoms assessment respectively– as stratification variables, only the second referred to the origin of the data. Only five meta-analyses [ 22 , 28 , 33 , 35 , 39 ] included meta-regression analyses to describe heterogeneity, none of which considered the source of data as an explanatory variable. Other findings for the inclusion of the data source as a variable in the analysis of heterogeneity are presented in Table Table3 3 .

Inclusion of the data source as a variable in the analysis of heterogeneity of the included meta-analyses

Abbreviations : APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, MIC minimum inhibitory concentration, SSRIs selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, TNF tumor necrosis factor

We finally assessed if the influence of the data origin on the conclusions of the meta-analyses was discussed by their respective authors. We found that only four meta-analyses [ 21 , 31 , 32 , 34 ] noted limitations derived from the type of data source used.

The findings of this research suggest that the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is underexplored as a source of heterogeneity and an effect modifier in meta-analyses of drug effects published in general medicine journals with high impact. Few meta-analyses reported the source of data and only one [ 34 ] of the articles included in our survey compared and discussed the meta-analysis results considering the different sources of data.

Although it is usual to consider the design of the individual studies (i.e. case-control, cohort or experimental studies) in the analysis of the heterogeneity of a meta-analysis [ 43 , 44 ], the type of data source (primary vs secondary) is still rarely used for this purpose [ 9 , 45 ]. In fact, the current reporting guidelines for meta-analyses, such as MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [ 18 ] or PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) [ 46 , 47 ], do not recommend that authors specifically report the origin of the data. This is probably due to the close relationship that exists between the study design and the type of data source used, despite the fact that each criterion has its own basis. Performing this additional analysis is a simple task that involves no additional cost. Failure to do so may lead to diverging conclusions [ 8 ].

Conclusions about the effects of a drug that are derived from studies based exclusively on data from secondary sources may be dicey, among other reasons, because no information is collected on consumption of over-the-counter drugs (i.e. drugs that individuals can buy without a prescription) [ 48 ] and/or out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs (i.e. costs that individuals pay out of their own cash reserves) [ 49 ]. In the health care and insurance context, out-of-pocket expenses usually refer to deductibles, co-payments or co-insurance. Figure Figure2 2 shows the model that we propose to describe the relationship between the different data records according to their origin, including the possible loss of information (susceptible to be registered only through primary research).

Conceptual model of individual data recording. * Never dispensed. † Absence of dispensing of successive prescriptions (or self-medication) among patients with primary adherence, or inadequate secondary adherence

Failure to take these situations into account may lead to exposure measurement bias [ 48 , 49 ]. Consumption of a drug may be underestimated when only prescription data is used as secondary source without additionally considering unregistered consumption, such as over-the-counter consumption (e.g. oral contraceptives [ 34 , 50 ]), that may only be available from a primary database. Alternatively, this may occur when dispensing data for billing purposes (reimbursement) are used for clinical research, if out-of-pocket expenses are not considered (see Fig. Fig.2). 2 ). The portion of the medical bill that the insurance company does not cover, and that the individual must pay on his own, is unlikely to be recorded. Data on the sale of over-the-counter drugs will also not be available in this scenario.

The reverse situation may also occur and consumption may be overestimated when only prescription data is used, if the prescribed drug is not dispensed by the pharmacist; or when dispensing data is used, if the drug is not really consumed by the patient. While primary non-adherence occurs when the patient does not pick up the medication after the first prescription, secondary non-adherence refers to the absence of dispensing of successive prescriptions among patients with primary adherence, or to inadequate secondary adherence (i.e. ≥20% of time without adequate medication) [ 51 ] (see Fig. Fig.2). 2 ). In some diseases the medication adherence is very low [ 52 – 55 ], with percentages of primary non-adherence (never dispensed) that exceed 30% [ 56 ]. It should be noted that the impact of non-adherence varies from medication to medication. Therefore, it must be defined and measured in the context of a particular therapy [ 57 ].

Moreover, failing to take into consideration the portion of consumption due to over-the-counter and/or out-of-pocket expenses may lead to confounding , as that variable may be related to the socio-economic level and/or to the potential of access to the health system [ 58 ], which are independent risk factors of adverse outcomes of some medications (e.g. myocardial infarction [ 21 , 28 , 30 , 41 ]). Given the presence of high-deductible health plans and the high co-insurance rate for some drugs, cost-sharing may deter clinically vulnerable patients from initiating essential medications, thus negatively affecting patient adherence [ 59 , 60 ].

Outcome misclassification may also give rise to measurement bias and heterogeneity [ 61 ]. This occurs, for example, in the meta-analysis that evaluates the relationship between combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis [ 34 ]. In the studies without objective confirmation of the outcome, the women were classified erroneously regardless of the use of contraceptives. This led to a non-differential misclassification that may have underestimated the drug–outcome relationship, especially when the third generation of progestogen is analysed: Risk ratio (RR) primary data = 6.2 (95% confidence interval (CI) 5.2–7.4), RR secondary data = 3.0 (95% CI 1.7–5.4) [ 34 ].

On the one hand, medical records are often considered as being the best information source for outcome variables. However, they present important limitations in the recording of medications taken by patients [ 62 ]. On the other hand, dispensing records show more detailed data on the measurement of drug exposure. However, they do not record the over-the-counter or out-of-pocket drug consumption at an individual level [ 48 , 49 ], apart from offering unreliable data on outcome variables [ 62 , 63 ].

Limitations

The first limitation of this research is that its findings may not be applicable to journals not included in our survey such as journals with low impact factor. Despite the widespread use of the impact factor metric [ 64 ], this method has inherent weaknesses [ 65 , 66 ]. However, meta-analyses published in high impact general medicine journals are likely to be most rigorously performed and reported due to their greater availability of resources and procedures [ 12 , 14 ]. It is then expected that the overall reporting quality of articles published in other lesser-known journals will be similar. Another limitation would be related to the limited search period . In this sense, and given that the general tendency is the improvement of the methodology of published meta-analyses [ 67 , 68 ], we find no reason to suspect that the adverse conclusions could be different before the period from 2012 to 2018. Although it exceeds the objective of this research, one last limitation may be the inability to reanalyse the included meta-analyses stratifying by the type of data source since our study design restricts the conclusions to the published data of the meta-analyses, which were insufficiently reported , or the number of individual studies in each stratum was insufficient to calculate a pooled measure (see Table Table2 2 ).