Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![how to write an abstract for a research presentation “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![how to write an abstract for a research presentation “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![how to write an abstract for a research presentation “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Contact AAPS

- Get the Newsletter

How to Write a Really Great Presentation Abstract

Whether this is your first abstract submission or you just need a refresher on best practices when writing a conference abstract, these tips are for you..

An abstract for a presentation should include most the following sections. Sometimes they will only be a sentence each since abstracts are typically short (250 words):

- What (the focus): Clearly explain your idea or question your work addresses (i.e. how to recruit participants in a retirement community, a new perspective on the concept of “participant” in citizen science, a strategy for taking results to local government agencies).

- Why (the purpose): Explain why your focus is important (i.e. older people in retirement communities are often left out of citizen science; participants in citizen science are often marginalized as “just” data collectors; taking data to local governments is rarely successful in changing policy, etc.)

- How (the methods): Describe how you collected information/data to answer your question. Your methods might be quantitative (producing a number-based result, such as a count of participants before and after your intervention), or qualitative (producing or documenting information that is not metric-based such as surveys or interviews to document opinions, or motivations behind a person’s action) or both.

- Results: Share your results — the information you collected. What does the data say? (e.g. Retirement community members respond best to in-person workshops; participants described their participation in the following ways, 6 out of 10 attempts to influence a local government resulted in policy changes ).

- Conclusion : State your conclusion(s) by relating your data to your original question. Discuss the connections between your results and the problem (retirement communities are a wonderful resource for new participants; when we broaden the definition of “participant” the way participants describe their relationship to science changes; involvement of a credentialed scientist increases the likelihood of success of evidence being taken seriously by local governments.). If your project is still ‘in progress’ and you don’t yet have solid conclusions, use this space to discuss what you know at the moment (i.e. lessons learned so far, emerging trends, etc).

Here is a sample abstract submitted to a previous conference as an example:

Giving participants feedback about the data they help to collect can be a critical (and sometimes ignored) part of a healthy citizen science cycle. One study on participant motivations in citizen science projects noted “When scientists were not cognizant of providing periodic feedback to their volunteers, volunteers felt peripheral, became demotivated, and tended to forgo future work on those projects” (Rotman et al, 2012). In that same study, the authors indicated that scientists tended to overlook the importance of feedback to volunteers, missing their critical interest in the science and the value to participants when their contributions were recognized. Prioritizing feedback for volunteers adds value to a project, but can be daunting for project staff. This speed talk will cover 3 different kinds of visual feedback that can be utilized to keep participants in-the-loop. We’ll cover strengths and weaknesses of each visualization and point people to tools available on the Web to help create powerful visualizations. Rotman, D., Preece, J., Hammock, J., Procita, K., Hansen, D., Parr, C., et al. (2012). Dynamic changes in motivation in collaborative citizen-science projects. the ACM 2012 conference (pp. 217–226). New York, New York, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145238

📊 Data Ethics – Refers to trustworthy data practices for citizen science.

Get involved » Join the Data Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

📰 Publication Ethics – Refers to the best practice in the ethics of scholarly publishing.

Get involved » Join the Publication Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

⚖️ Social Justice Ethics – Refers to fair and just relations between the individual and society as measured by the distribution of wealth, opportunities for personal activity, and social privileges. Social justice also encompasses inclusiveness and diversity.

Get involved » Join the Social Justice Topic Room on CSA Connect!

👤 Human Subject Ethics – Refers to rules of conduct in any research involving humans including biomedical research, social studies. Note that this goes beyond human subject ethics regulations as much of what goes on isn’t covered.

Get involved » Join the Human Subject Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🍃 Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics – Refers to the improvement of the dynamics between humans and the myriad of species that combine to create the biosphere, which will ultimately benefit both humans and non-humans alike [UNESCO 2011 white paper on Ethics and Biodiversity ]. This is a kind of ethics that is advancing rapidly in light of the current global crisis as many stakeholders know how critical biodiversity is to the human species (e.g., public health, women’s rights, social and environmental justice).

⚠ UNESCO also affirms that respect for biological diversity implies respect for societal and cultural diversity, as both elements are intimately interconnected and fundamental to global well-being and peace. ( Source ).

Get involved » Join the Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🤝 Community Partnership Ethics – Refers to rules of engagement and respect of community members directly or directly involved or affected by any research study/project.

Get involved » Join the Community Partnership Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

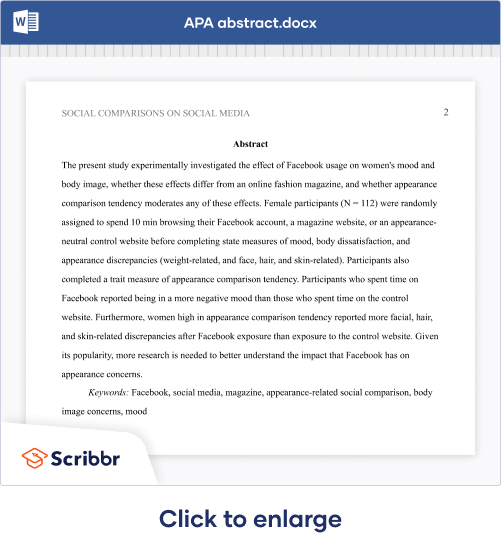

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

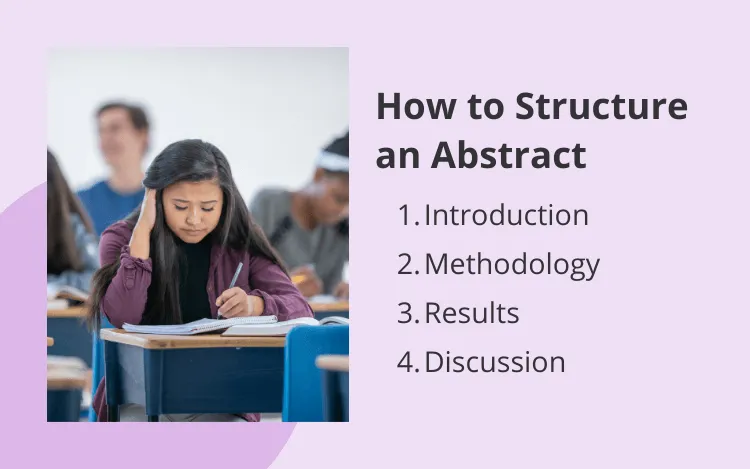

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

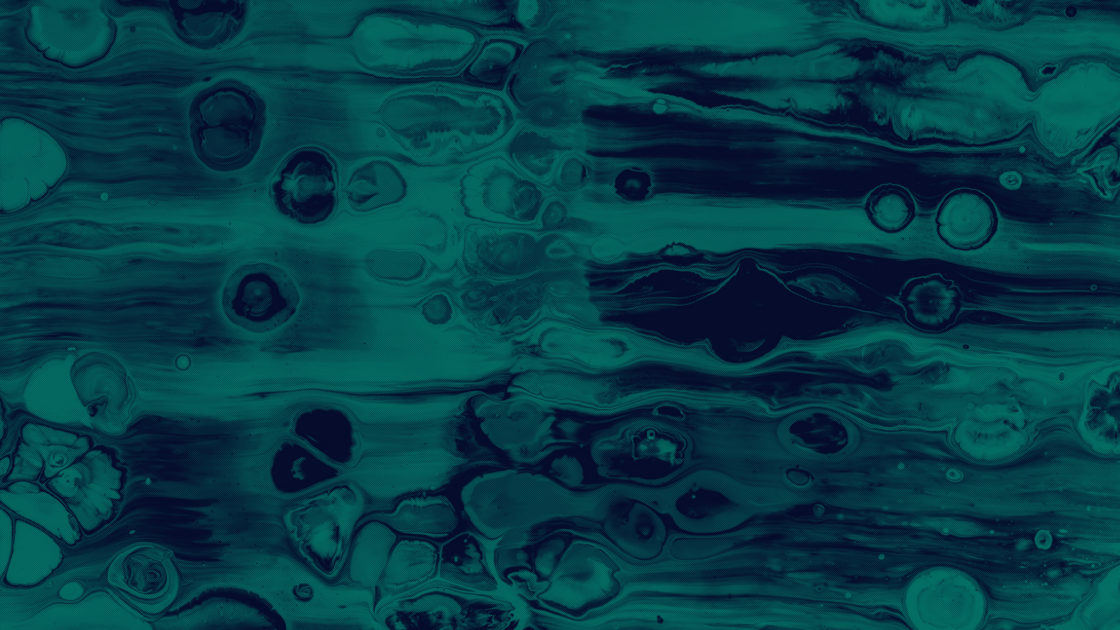

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Meetings & Events

- ACS Meetings & Expositions

- ACS Fall 2024

How to Write an Undergraduate Abstract

Writing an abstract for the undergraduate research poster session.

By Elzbieta Cook, Louisiana State University

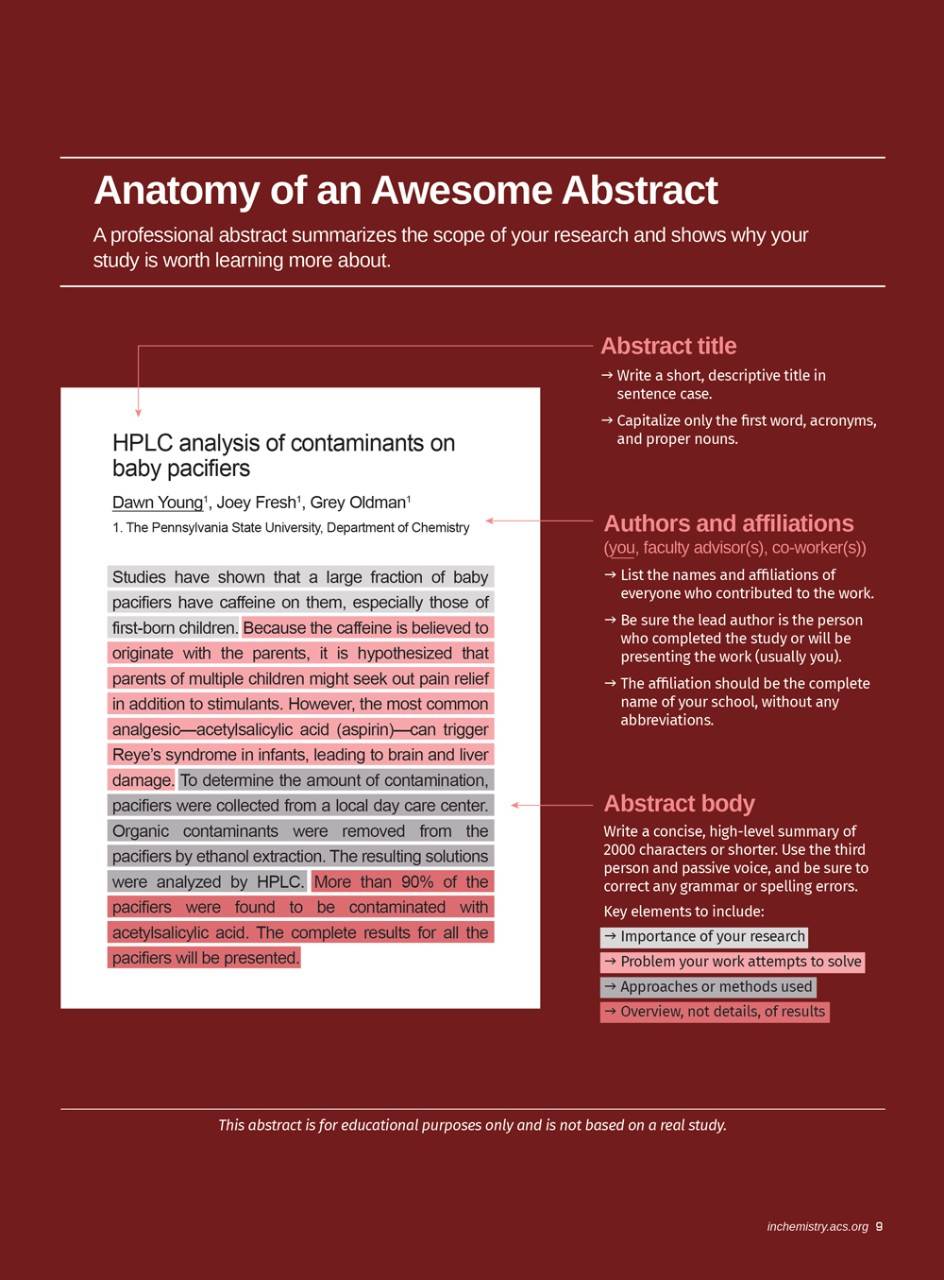

General Rules and Accepted Practices

Successful abstracts exhibit what is generally accepted as good scientific communication. The following guidelines specify all aspects of how a good abstract is written.

The Title is informative; it is neither too long nor too short, and it does not oversell or sensationalize the content of the presentation.

- Make the title descriptive, yet short and sweet.

- Do not start the t itle with “The”, “A”, or “An.”

- Capitalize only the first letter of the first word of the title, the first letter of the first word after a colon, and any proper names, acronyms (e.g., NMR) or chemical formulas (e.g., NaOH).

- Do not put a period at the end of the title.

The body of the abstract briefly frames the researched issue, succinctly describes the performed research, and outlines the findings and general conclusions without going into too many details or numbers.

- Do not write everything you did in your work. Briefly frame the research you will be describing. Your poster will be a better place to elaborate on selected aspects of your research. Instead, make general statements in regards to what was done, what techniques were used, what type of information was gained (without going into details of specific results), and what the potential benefits or significance of the findings are.

- Ensure that the content of the abstract is approved by your research advisor. In addition to getting valuable feedback on how you write, your research advisor will know which results are ready to be shared in your presentation and which belong elsewhere. Additionally, the advisor is responsible for your work and, consequently, your work and results.

- Do not make literature references to other published research in the abstract. A good place for literature references is in the introduction of your poster. Likewise, unless specifically requested by the session organizers, do not include funding information in the abstract. Your research program and funding sources can be mentioned in the acknowledgment part of your poster.

- Do not use “I” and “we” when reporting on you research. It is okay to state, for instance, that “research in our group is focused on…” The passive voice is still the standard in scientific literature, even if it makes your English teacher cringe.

- Exercise restraint when placing figures, schemes, and tables in the abstract. The body of your poster is a much better place for the majority of artwork. Having said that, figures, schemes, and tables are allowed in the abstract, but you need to watch the character count, as these features quickly add hundreds of characters.

- Limit the number of characters for the entire abstract to 2,500 . This includes the title, the body, and the authors, along with their affiliations.

The list of authors, in addition to the presenting undergraduate student(s), always includes the name of the research advisor(s) as well as any other non-presenting author who contributed to the presented work.

- The list of authors must include the presenting author(s) . The presenting author is you and any other undergraduate student who will present the research with you.

- Include the name(s) of your research advisor(s) on the list of poster authors. With few exceptions, undergraduate research is typically funded through a grant applied for and received by a research mentor, and must be properly acknowledged. Your research project is likely the brainchild of your research advisor, even if you contributed to its development. Remember that credit must go where it belongs! Even if you are the only person who performs the experiments, you do so under the supervision of a research advisor or graduate student (who, in turn, is financially supported by the mentor). In addition, the costs of hosting you in the laboratory, including disposables, software licenses, hazardous waste disposal, and even the costs of keeping the lab air-conditioned, the lights on and the elevator functioning, are typically courtesy of the host group (covered from your mentor’s indirect costs). The reviewer of your abstract will check whether the list of authors includes the name of the research advisor. Submissions without this information will not be accepted until the necessary correction is made.

- List the presenting author first. While there is no strict rule about the order of authors, it is common that the presenting author is listed first. If there is more than one presenting author, the order should follow that of their contributions, followed by non-presenting authors, with the research mentor being listed at the end. Some research mentors elect to be the first authors on undergraduate research posters, but care must be taken so that they are not listed as presenting authors. Again, the reviewer of your abstract will check to see whether the research mentor is listed as a presenting author, and if that is the case, the abstract will be returned to the authors for further clarification.

NOTE: Only undergraduate students are allowed to present in the Undergraduate Research Poster session. Any research mentor who wishes to present the results from an undergraduate project must do so in another session.

Affiliations

- Ensure that the name and the address of each college, university, institute, etc., is the same for all authors who come from that school. For instance, MAPS, the ACS’s abstract submission system, will “think” that Penn State and The Pennsylvania State University are two different schools and will assign two different affiliations to authors who were, after all, working in the same lab!

- The order of affiliations should follow the order of authors.

Submitting an Abstract to the Correct Session

It is a common error for students and faculty to submit a poster abstract to an incorrect session. The confusion often comes from the fact that the Chemical Education division of the ACS (DivCHED) accepts two types of poster abstracts: those from faculty about their chemical education research and those from undergraduate students about their research in a particular technical discipline.

The Undergraduate Research Poster Session in DivCHED is custom made for undergraduate student research. It is a good place to submit an abstract here, whether it’s your first presentation at a National Meeting or your third or fourth (as long as you’re still an undergrad).

Nevertheless, you should consult with your research advisor to find the right place to submit. If you do plan on submitting to a division other than DivCHED (e.g. Division of Analytical Chemistry), it’s a good idea to check with the division program chair to find the best place to showcase your research.

The Undergraduate Research Poster Session is meant only for undergraduate student presenters (i.e., you!). ACS has created several sub-divisions for the various sub-disciplines in chemistry, so you can present in an area that closely relates to your research.

In the Undergraduate Research Poster Session, you’ll want to choose the area of chemistry your research fits best, such as biochemistry, environmental, etc. If your undergraduate research is organic chemistry, for example, select Undergraduate Research Posters: Organic Chemistry-Poster . Only if you have helped to develop a new laboratory experiment or in-class demonstration, or you have analyzed learning outcomes of new learning strategies or a new pedagogy—will you want to submit your abstract to Undergraduate Research Posters: Chemical Education-Poster.

Remember, you, as an undergraduate researcher, must register and attend the meeting to present your work. Please note that if a faculty researcher, a postdoctoral candidate, or a graduate student wishes to present a poster on chemistry education research, they should submit their abstract to the CHED division in the General Poster Session. This article is not meant for such submissions.

Get Support

Talk to our meetings team.

Contacts for registration, hotel, presenter support or any other questions.

Contact Meetings Team

Denver, CO & Hybrid

Colorado Convention Center | August 18 - 22

#ACSFall2024

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

University of Missouri

- Bias Hotline: Report bias incidents

Undergraduate Research

- How to Write An Abstract

Think of your abstract or artist statement like a movie trailer: it should leave the reader eager to learn more but knowledgeable enough to grasp the scope of your work. Although abstracts and artist statements need to contain key information on your project, your title and summary should be understandable to a lay audience.

Please remember that you can seek assistance with any of your writing needs at the MU Writing Center . Their tutors work with students from all disciplines on a wide variety of documents. And they are specially trained to use the Abstract Review Rubric that will be used on the abstracts reviewed at the Spring Forum.

Types of Research Summaries

Students should submit artist statements as their abstracts. Artist statements should introduce to the art, performance, or creative work and include information on media and methods in creating the pieces. The statements should also include a description of the inspiration for the work, the meaning the work signifies to the artist, the artistic influences, and any unique methods used to create the pieces. Students are encouraged to explain the connections of the work with their inspirations or themes. The statements should be specific to the work presented and not a general statements about the students’ artistic philosophies and approaches. Effective artist statements should provide the viewer with information to better understand the work of the artists. If presentations are based on previous performances, then students may include reflections on the performance experiences and audience reactions.

Abstracts should describe the nature of the project or piece (ex: architectural images used for a charrette, fashion plates, advertising campaign story boards) and its intended purpose. Students should describe the project or problem that they addressed and limitations and challenges that impact the design process. Students may wish to include research conducted to provide context for the project and inform the design process. A description of the clients/end users may be included. Information on inspirations, motivations, and influences may also be included as appropriate to the discipline and project. A description of the project outcome should be included.

Abstracts should include a short introduction or background to put the research into context; purpose of the research project; a problem statement or thesis; a brief description of materials, methods, or subjects (as appropriate for the discipline); results and analysis; conclusions and implications; and recommendations. For research projects still in progress at the time of abstract submission, students may opt to indicate that results and conclusions will be presented [at the Forum].

Tips for writing a clear and concise abstract

The title of your abstract/statement/poster should include some language that the lay person can understand. When someone reads your title they should have SOME idea of the nature of your work and your discipline.

Ask a peer unfamiliar with your research to read your abstract. If they’re confused by it, others will be too.

Keep it short and sweet.

- Interesting eye-catching title

- Introduction: 1-3 sentences

- What you did: 1 sentence

- Why you did it: 1 sentence

- How you did it: 1 sentence

- Results or when they are expected: 2 sentences

- Conclusion: 1-3 sentences

Ideas to Address:

- The big picture your project helps tackle

- The problem motivating your work on this particular project

- General methods you used

- Results and/or conclusions

- The next steps for the project

Things to Avoid:

- A long and confusing title

- Jargon or complicated industry terms

- Long description of methods/procedures

- Exaggerating your results

- Exceeding the allowable word limit

- Forgetting to tell people why to care

- References that keep the abstract from being a “stand alone” document

- Being boring, confusing, or unintelligible!

Artist Statement

The artist statement should be an introduction to the art and include information on media and methods in creating the piece(s). It should include a description of the inspiration for the work, what the work signifies to the artist, the artistic influences, and any unique methods used to create the work. Students are encouraged to explain the connections of the work with their inspiration or theme. The artist statement (up to 300 words) should be written in plain language to invite viewers to learn more about the artist’s work and make their own interpretations. The statement should be specific to the piece(s) that will be on display, and not a general statement about the student’s artistic philosophy and approach. An effective artist statement should provide the viewer with information to better understand and experience viewing the work on display.

Research/Applied Design Abstract

The project abstract (up to 300 words) should describe the nature of the project or piece (ex: architectural images used for a charrette, fashion plates, small scale model of a theater set) and its intended purpose. Students should describe the project or problem that was addressed and limitations and challenges that impact the design process. Students may wish to include research conducted to provide context for the project and inform the design process. A description of the clients/end users may be included. Information on inspirations, motivations, and influences may also be included as appropriate to the discipline and project.

Key Considerations

- What is the problem/ big picture that your project helps to address?

- What is the appropriate background to put your project into context? What do we know? What don’t we know? (informed rationale)

- What is YOUR project? What are you seeking to answer?

- How do you DO your research? What kind of data do you collect? How do you collect it?

- What is the experimental design? Number of subjects or tests run? (quantify if you can!)

- Provide some data (not raw, but analyzed)

- What have you found? What are your results? How do you KNOW this – how did you analyze this?

- What does this mean?

- What are the next steps? What don’t we know still?

- How does this relate (again) to the bigger picture. Who should care and why? (what is your audience?)

More Resources

- Abstract Writing Presentation from University of Illinois – Chicago

- Sample Abstracts

- A 10-Step Guide to Make Your Research Paper More Effective

- Your Artist Statement: Explaining the Unexplainable

- How to Write an Artist Statement

Here is the Forum Abstract Review Rubric for you and your mentor to use when writing your abstract to submit to the Spring Research & Creative Achievements Forum.

Office of Undergraduate Research

- Office of Undergraduate Research FAQ's

- URSA Engage

- Resources for Students

- Resources for Faculty

- Engaging in Research

- Presenting Your Research

- Earn Money by Participating in Research Studies

- Transcript Notation

- Student Publications

How to Write an Abstract

How to write an abstract for a conference, what is an abstract and why is it important, an abstract is a brief summary of your research or creative project, usually about a paragraph long (250-350 words), and is written when you are ready to present your research or included in a thesis or research publication..

For additional support in writing your abstract, you can contact the Office of URSA at [email protected] or schedule a time to meet with a Writing and Research Consultant at the OSU Writing Center

Main Components of an Abstract:

The opening sentences should summarize your topic and describe what researchers already know, with reference to the literature.

A brief discussion that clearly states the purpose of your research or creative project. This should give general background information on your work and allow people from different fields to understand what you are talking about. Use verbs like investigate, analyze, test, etc. to describe how you began your work.

In this section you will be discussing the ways in which your research was performed and the type of tools or methodological techniques you used to conduct your research.

This is where you describe the main findings of your research study and what you have learned. Try to include only the most important findings of your research that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions. If you have not completed the project, talk about your anticipated results and what you expect the outcomes of the study to be.

Significance

This is the final section of your abstract where you summarize the work performed. This is where you also discuss the relevance of your work and how it advances your field and the scientific field in general.

- Your word count for a conference may be limited, so make your abstract as clear and concise as possible.

- Organize it by using good transition words found on the lef so the information flows well.

- Have your abstract proofread and receive feedback from your supervisor, advisor, peers, writing center, or other professors from different disciplines.

- Double-check on the guidelines for your abstract and adhere to any formatting or word count requirements.

- Do not include bibliographic references or footnotes.

- Avoid the overuse of technical terms or jargon.

Feeling stuck? Visit the OSU ScholarsArchive for more abstract examples related to your field

Contact Info

618 Kerr Administration Building Corvallis, OR 97331

541-737-5105

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write an Abstract (With Examples)

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is an abstract in a paper, how long should an abstract be, 5 steps for writing an abstract, examples of an abstract, how prowritingaid can help you write an abstract.

If you are writing a scientific research paper or a book proposal, you need to know how to write an abstract, which summarizes the contents of the paper or book.

When researchers are looking for peer-reviewed papers to use in their studies, the first place they will check is the abstract to see if it applies to their work. Therefore, your abstract is one of the most important parts of your entire paper.

In this article, we’ll explain what an abstract is, what it should include, and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of the details within a report. Some abstracts give more details than others, but the main things you’ll be talking about are why you conducted the research, what you did, and what the results show.

When a reader is deciding whether to read your paper completely, they will first look at the abstract. You need to be concise in your abstract and give the reader the most important information so they can determine if they want to read the whole paper.

Remember that an abstract is the last thing you’ll want to write for the research paper because it directly references parts of the report. If you haven’t written the report, you won’t know what to include in your abstract.

If you are writing a paper for a journal or an assignment, the publication or academic institution might have specific formatting rules for how long your abstract should be. However, if they don’t, most abstracts are between 150 and 300 words long.

A short word count means your writing has to be precise and without filler words or phrases. Once you’ve written a first draft, you can always use an editing tool, such as ProWritingAid, to identify areas where you can reduce words and increase readability.

If your abstract is over the word limit, and you’ve edited it but still can’t figure out how to reduce it further, your abstract might include some things that aren’t needed. Here’s a list of three elements you can remove from your abstract:

Discussion : You don’t need to go into detail about the findings of your research because your reader will find your discussion within the paper.

Definition of terms : Your readers are interested the field you are writing about, so they are likely to understand the terms you are using. If not, they can always look them up. Your readers do not expect you to give a definition of terms in your abstract.

References and citations : You can mention there have been studies that support or have inspired your research, but you do not need to give details as the reader will find them in your bibliography.

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

If you’ve never written an abstract before, and you’re wondering how to write an abstract, we’ve got some steps for you to follow. It’s best to start with planning your abstract, so we’ve outlined the details you need to include in your plan before you write.

Remember to consider your audience when you’re planning and writing your abstract. They are likely to skim read your abstract, so you want to be sure your abstract delivers all the information they’re expecting to see at key points.

1. What Should an Abstract Include?

Abstracts have a lot of information to cover in a short number of words, so it’s important to know what to include. There are three elements that need to be present in your abstract:

Your context is the background for where your research sits within your field of study. You should briefly mention any previous scientific papers or experiments that have led to your hypothesis and how research develops in those studies.

Your hypothesis is your prediction of what your study will show. As you are writing your abstract after you have conducted your research, you should still include your hypothesis in your abstract because it shows the motivation for your paper.

Throughout your abstract, you also need to include keywords and phrases that will help researchers to find your article in the databases they’re searching. Make sure the keywords are specific to your field of study and the subject you’re reporting on, otherwise your article might not reach the relevant audience.

2. Can You Use First Person in an Abstract?

You might think that first person is too informal for a research paper, but it’s not. Historically, writers of academic reports avoided writing in first person to uphold the formality standards of the time. However, first person is more accepted in research papers in modern times.

If you’re still unsure whether to write in first person for your abstract, refer to any style guide rules imposed by the journal you’re writing for or your teachers if you are writing an assignment.

3. Abstract Structure

Some scientific journals have strict rules on how to structure an abstract, so it’s best to check those first. If you don’t have any style rules to follow, try using the IMRaD structure, which stands for Introduction, Methodology, Results, and Discussion.

Following the IMRaD structure, start with an introduction. The amount of background information you should include depends on your specific research area. Adding a broad overview gives you less room to include other details. Remember to include your hypothesis in this section.

The next part of your abstract should cover your methodology. Try to include the following details if they apply to your study:

What type of research was conducted?

How were the test subjects sampled?

What were the sample sizes?

What was done to each group?

How long was the experiment?

How was data recorded and interpreted?

Following the methodology, include a sentence or two about the results, which is where your reader will determine if your research supports or contradicts their own investigations.

The results are also where most people will want to find out what your outcomes were, even if they are just mildly interested in your research area. You should be specific about all the details but as concise as possible.

The last few sentences are your conclusion. It needs to explain how your findings affect the context and whether your hypothesis was correct. Include the primary take-home message, additional findings of importance, and perspective. Also explain whether there is scope for further research into the subject of your report.

Your conclusion should be honest and give the reader the ultimate message that your research shows. Readers trust the conclusion, so make sure you’re not fabricating the results of your research. Some readers won’t read your entire paper, but this section will tell them if it’s worth them referencing it in their own study.

4. How to Start an Abstract

The first line of your abstract should give your reader the context of your report by providing background information. You can use this sentence to imply the motivation for your research.

You don’t need to use a hook phrase or device in your first sentence to grab the reader’s attention. Your reader will look to establish relevance quickly, so readability and clarity are more important than trying to persuade the reader to read on.

5. How to Format an Abstract

Most abstracts use the same formatting rules, which help the reader identify the abstract so they know where to look for it.

Here’s a list of formatting guidelines for writing an abstract:

Stick to one paragraph

Use block formatting with no indentation at the beginning

Put your abstract straight after the title and acknowledgements pages

Use present or past tense, not future tense

There are two primary types of abstract you could write for your paper—descriptive and informative.

An informative abstract is the most common, and they follow the structure mentioned previously. They are longer than descriptive abstracts because they cover more details.

Descriptive abstracts differ from informative abstracts, as they don’t include as much discussion or detail. The word count for a descriptive abstract is between 50 and 150 words.

Here is an example of an informative abstract:

A growing trend exists for authors to employ a more informal writing style that uses “we” in academic writing to acknowledge one’s stance and engagement. However, few studies have compared the ways in which the first-person pronoun “we” is used in the abstracts and conclusions of empirical papers. To address this lacuna in the literature, this study conducted a systematic corpus analysis of the use of “we” in the abstracts and conclusions of 400 articles collected from eight leading electrical and electronic (EE) engineering journals. The abstracts and conclusions were extracted to form two subcorpora, and an integrated framework was applied to analyze and seek to explain how we-clusters and we-collocations were employed. Results revealed whether authors’ use of first-person pronouns partially depends on a journal policy. The trend of using “we” showed that a yearly increase occurred in the frequency of “we” in EE journal papers, as well as the existence of three “we-use” types in the article conclusions and abstracts: exclusive, inclusive, and ambiguous. Other possible “we-use” alternatives such as “I” and other personal pronouns were used very rarely—if at all—in either section. These findings also suggest that the present tense was used more in article abstracts, but the present perfect tense was the most preferred tense in article conclusions. Both research and pedagogical implications are proffered and critically discussed.

Wang, S., Tseng, W.-T., & Johanson, R. (2021). To We or Not to We: Corpus-Based Research on First-Person Pronoun Use in Abstracts and Conclusions. SAGE Open, 11(2).

Here is an example of a descriptive abstract:

From the 1850s to the present, considerable criminological attention has focused on the development of theoretically-significant systems for classifying crime. This article reviews and attempts to evaluate a number of these efforts, and we conclude that further work on this basic task is needed. The latter part of the article explicates a conceptual foundation for a crime pattern classification system, and offers a preliminary taxonomy of crime.

Farr, K. A., & Gibbons, D. C. (1990). Observations on the Development of Crime Categories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 34(3), 223–237.

If you want to ensure your abstract is grammatically correct and easy to read, you can use ProWritingAid to edit it. The software integrates with Microsoft Word, Google Docs, and most web browsers, so you can make the most of it wherever you’re writing your paper.

Before you edit with ProWritingAid, make sure the suggestions you are seeing are relevant for your document by changing the document type to “Abstract” within the Academic writing style section.

You can use the Readability report to check your abstract for places to improve the clarity of your writing. Some suggestions might show you where to remove words, which is great if you’re over your word count.

We hope the five steps and examples we’ve provided help you write a great abstract for your research paper.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

Writing Informative Abstracts

Informative abstracts state in one paragraph the essence of a whole paper about a study or a research project. That one paragraph must mention all the main points or parts of the paper: a description of the study or project, its methods, the results, and the conclusions. Here is an example of the abstract accompanying a seven-page essay that appeared in 2002 in The Journal of Clinical Psychology :

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

The relationship between boredom proneness and health-symptom reporting was examined. Undergraduate students (N = 200) completed the Boredom Proneness Scale and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist. A multiple analysis of covariance indicated that individuals with high boredom-proneness total scores reported significantly higher ratings on all five sub-scales of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Obsessive–Compulsive, Somatization, Anxiety, Interpersonal Sensitivity, and Depression). The results suggest that boredom proneness may be an important element to consider when assessing symptom reporting. Implications for determining the effects of boredom proneness on psychological- and physical-health symptoms, as well as the application in clinical settings, are discussed. —Jennifer Sommers and Stephen J. Vodanovich, (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); “Boredom Proneness”

The first sentence states the nature of the study being reported. The next summarizes the method used to investigate the problem, and the following one gives the results: students who, according to specific tests, are more likely to be bored are also more likely to have certain medical or psychological symptoms. The last two sentences indicate that the paper discusses those results and examines the conclusion and its implications.

Writing Descriptive Abstracts

Descriptive abstracts are usually much briefer than informative abstracts and provide much less information. Rather than summarizing the entire paper, a descriptive abstract functions more as a teaser, providing a quick overview that invites the reader to read the whole. Descriptive abstracts usually do not give or discuss results or set out the conclusion or its implications. A descriptive abstract of the boredom-proneness essay might simply include the first sentence from the informative abstract plus a final sentence of its own:

The relationship between boredom proneness and health-symptom reporting was examined. The findings and their application in clinical settings are discussed.

Writing Proposal Abstracts

Proposal abstracts contain the same basic information as informative abstracts, but their purpose is very different. You prepare proposal abstracts to persuade someone to let you write on a topic, pursue a project, conduct an experiment, or present a paper at a scholarly conference. This kind of abstract is not written to introduce a longer piece but rather to stand alone, and often the abstract is written before the paper itself. Titles and other aspects of the proposal deliberately reflect the theme of the proposed work, and you may use the future tense, rather than the past, to describe work not yet completed. Here is a possible proposal for doing research on boredom:

Undergraduate students will complete the Boredom Proneness Scale and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist. A multiple analysis of covariance will be performed to determine the relationship between boredom-proneness total scores and ratings on the five sub-scales of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Obsessive–Compulsive, Somatization, Anxiety, Interpersonal Sensitivity, and Depression).

Key Features of a Research Paper Abstract

- A summary of basic information . An informative abstract includes enough information to substitute for the report itself, a descriptive abstract offers only enough information to let the audience decide whether to read further, and a proposal abstract gives an overview of the planned work.

- Objective description . Abstracts present information on the contents of a report or a proposed study; they do not present arguments about or personal perspectives on those contents. The informative abstract on boredom proneness, for example, offers only a tentative conclusion: “The results suggest that boredom proneness may be an important element to consider.”

- Brevity . Although the length of abstracts may vary, journals and organizations often restrict them to 120–200 words—meaning you must carefully select and edit your words.

A Brief Guide to Writing Abstracts

Consider the rhetorical situation.

- Purpose : Are you giving a brief but thorough overview of a completed study? Only enough information to create interest? Or a proposal for a planned study or presentation?

- Audience : For whom are you writing this abstract? What information about your project will your readers need?

- Stance : Whatever your stance in the longer work, your abstract must be objective.

- Media/Design : How will you set your abstract off from the rest of the text? If you are publishing it online, will you devote a single page to it? What format does your audience require?

Generating Ideas and Text