- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

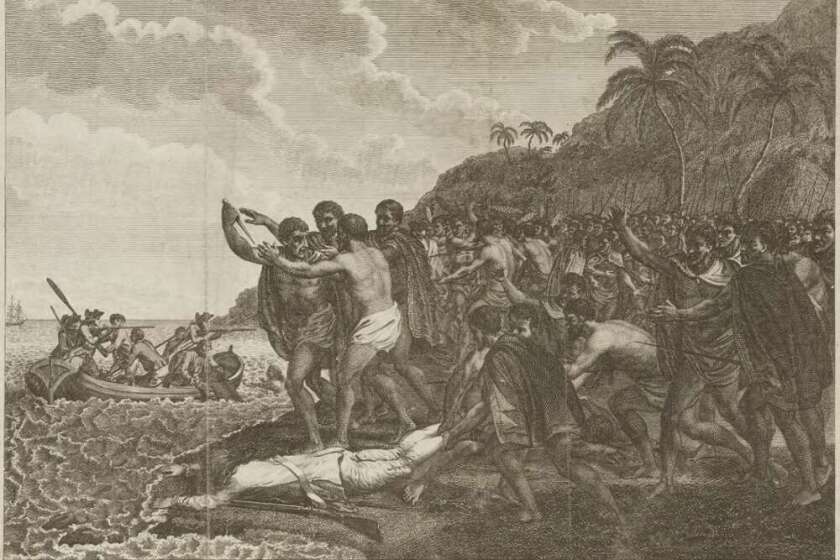

2 History and Memory

- Published: May 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter describes how memory has shaped the academic discipline of history. In the past two decades or so, ‘memory’ as a category to analyze and understand the relation of human beings to their past has become a nearly ubiquitous concept. Triggered jointly by the general crisis of representationalism and by a specific historical experience—the Holocaust—‘memory’ has replaced for some scholars a rather linear and monodimensional concept of ‘society’. Whereas in the past, memory was considered to be subjective and unreliable, it has now moved to centre-stage: it is in individual and collective memory that the past remains present in the contemporary agent. Memory, captured in methodological approaches such as oral history, also foregrounds the historical experience of ordinary people and thus carries the potential to counterbalance official, state-focused, and politically legitimate historical narratives, as well as those more broadly sanctioned by the academic enterprise.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Andrew Goldstone

- Christopher Kark

- Christopher Warley

- Claire Seiler

- Eleanor Courtemanche

- Gregory Freidin

- Gregory Jusdanis

- Irakli Zurab Kakabadze

- Joseph Lease

- Meredith Ramirez Talusan

- Mike Chasar

- Roland Greene

- William Egginton

- William Flesch

- All Authors

- All Multimedia

- Republics of Letters

You are here

Morrison’s Things: Between History and Memory

by Kinohi Nishikawa

Toni Morrison remains the most influential theorist of the black past in contemporary letters. Since the publication of Beloved and its companion essay “The Site of Memory” in 1987, Morrison has provided the impetus and vocabulary for those wishing to claim that the past is never past but always present. Indeed, the closest thing to a prevailing method in African American literary criticism could be described as the Morrisonian imperative to read how the past haunts the present, making itself known and felt among the living in ways both explicit and subtle. The field’s current keywords—aftermath, afterlife, repetition, and return—reflect that orientation. Christina Sharpe has gone so far as to describe the object of African American criticism as “the ditto ditto in the archives of the present.” [1]

Ironically, what’s been forgotten in this canonization of the Morrison of 1987 is that she began to formulate her engagement with the black past over a decade earlier, in a project for which she served as editor and makeshift curator of objects. In 1974 Random House brought out a book that Morrison had spent 18 months assembling with four collectors of black memorabilia. Though already a twice-published novelist, Morrison used her status as an influential editor at Random House to see the project through. The result was The Black Book : a 200-page, oversized compendium that conveys the story of African and African-descended people in the New World, from the era of colonization, through the age of chattel slavery, and up to the waning days of Jim Crow. “Conveys” because The Black Book does not offer a textual narrative of events. Instead, it relies on pictures—that is, photographic reproductions of specific objects Morrison culled from her collaborators’ collections—to evoke what Sharpe has called the “total climate” of blacks’ experience of transatlantic slavery and its aftermath. [2] The pictures tell their own story, one that is impressionistic rather than authoritative, fragmentary rather than whole. And that is the point. Unlike books written by academic historians, which tend to ascribe a telos to narratives about the past (i.e., from slavery to freedom), Morrison envisioned her work as a “genuine Black history book—one that simply recollected Black Life as lived.” [3] This notion of recollection—of literally re-collecting and figuratively recollecting “Black history”—is the forgotten materialist basis of what Morrison would famously term “rememory” in 1987.

Though a wide body of scholarship has been built up around Morrison, surprisingly little has been written about The Black Book . The oversight is odd since putting the volume together not only launched Morrison’s theorization of the black past but also introduced her to the source material for her best-known work. A nondescript clipping from the February 1856 issue of the American Baptist relates the story of an enslaved woman, Margaret Garner, who tried to kill her young children rather than have them grow up in bondage. Recounted by the Reverend P. S. Bassett, the episode is didactic, highlighting for a white abolitionist readership the impossible decisions enslaved people were compelled to make between freedom and survival. While this story has long been recognized as the inspiration for Beloved , only the critic Cheryl A. Wall has devoted more than passing attention to its place in The Black Book . Yet even she contends that the clipping’s significance lies in the way it prefigures Beloved ’s imperative to read the past in the present. [4] This despite the fact that the excerpt appears early in the book (page 10), when the reading experience is most disorienting, and is easily missed among two densely packed facing pages of clippings and text. Fifteen independent items—some photo-reproduced from original sources, others quoted and set in uniform type—crowd the layout. Smudges and other errors from the copying process further diminish the readability of the text. In the actual composition of The Black Book , nothing makes Garner’s story stand out, which, again, is the point: it is merely one piece of the dizzying puzzle of history.

What was distinctive about Morrison’s engagement with the black past in 1974? How might a historicist obsession with 1987 obscure what she set out to do in The Black Book ? I take a first step toward answering these questions in what follows. I propose that The Black Book advances a more contingent and discontinuous view of history than the one usually attributed to Morrison. This view, I argue, owes much to the book’s composition, which is pictorial and iconic rather than textual and discursive. By “flattening” history into a series of decontextualized images, The Black Book encourages glossing, skipping pages, reading out of order, and finding meaning only in visual or “surface” resemblances. These (non-)reading practices are further encouraged by the fact that Morrison does not discriminate when it comes to identifying things that evoke the black past. Examples of black ingenuity and perseverance appear alongside those of racial parody and animus, while handcrafted wares and mass-produced commodities vie for attention in the same span of pages, confusing the distinction between folk and market. In short, The Black Book gives one access to the black past only through an inquisitive perusal—an actual looking at things. Accordingly, its view of history is premised on an awareness that readers’ grounding in the present is far from certain. Not everyone can or will want to engage The Black Book ’s arrangement of things. What matters for Morrison, here and in her work to come, is not the fact of recovery but the question of how one re-collects the past at all.

The first thing to note about The Black Book is that it’s chock-full of text. Captions and explanatory notes appear underneath or alongside most pictures. Several types of documents—letters, certificates, applications—naturally feature handwritten or printed text. And newspaper clippings and other text-heavy ephemera take up a lot of space in the book, especially early on. Still, I would maintain that The Black Book ’s composition is essentially pictorial insofar as it decouples “understanding” the text from reading it closely. Morrison lends meaning to any given thing by how she associates it with other things—on a single page, over facing pages, or across successive pages. Think of it like reading a museum catalog: the point is to get the gist of its visual organization, not to linger over every word.

At a pictorial level, certain layouts in The Black Book give a fairly coherent impression of the meaning behind the assembled artifacts. One facing-page layout, for example, combines the following: five fugitive slave ads printed in 1790; two undated classifieds, likely from the mid-1800s; W. H. Siebert’s 1896 historical map “‘Underground’ Routes to Canada”; Samuel Rowse’s 1850 lithograph The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia ; and an 1857 letter from William Brinkl[e]y, one of Harriet Tubman’s associates in Delaware. All of these things appear under the bold heading “I rode a railroad that had no track. ” [5] True, the individual pictures are decontextualized (supporting information on the lithograph and Brinkley do not appear in The Black Book ), with only Brown’s fugitive plot given an explanatory note. Still, the layout’s overall composition conveys the resolve and resourcefulness of fugitives from slavery as they ran toward freedom, as well as the desperate efforts of white enslavers to retrieve them. Sides are drawn, sympathies are channeled, and the “goal,” Canada, is clearly delineated. In this way, Morrison’s things not only document something called the Underground Railroad; they also evoke, in the present tense, what it would have meant and felt like for an enslaved person to take flight.

Yet the coherence of this particular display is a rarity in The Black Book . Discordant juxtapositions are far more common, such that any impression of historical perspective is immediately undercut with confounding, contingent details. One page, for example, has a small photograph that shows a black woman holding a white infant in her lap. The original caption reads “Slave and Friend.” But printed next to this image are lyrics for “All the Pretty Little Horses,” and underneath both is Morrison’s clarification that the song is “an authentic slave lullaby [that] reveals the bitter feelings of Negro mothers who had to watch over their white charges while neglecting their own children.” Trying to exert a measure of control over the artifact and its description, Morrison inserts another artifact whose narrativization is supposed to guide the reader toward a “correct” reading of the image. Yet the page’s pictorial composition is irreducible to that gesture, for underneath this tableau are antebellum newspaper clippings addressing black westward expansion (one from the New York Tribune , the other from the Liberator ) and a maniculed notice prohibiting “the employment of free colored persons on water-craft navigating the rivers of [Arkansas].” [6] What these artifacts have to do with each other from a historical perspective is a mystery. But their visual organization does elicit wonderfully weird associations, as one might detect between the white baby’s hand (clasped over the black woman’s) and the indexical manicule.

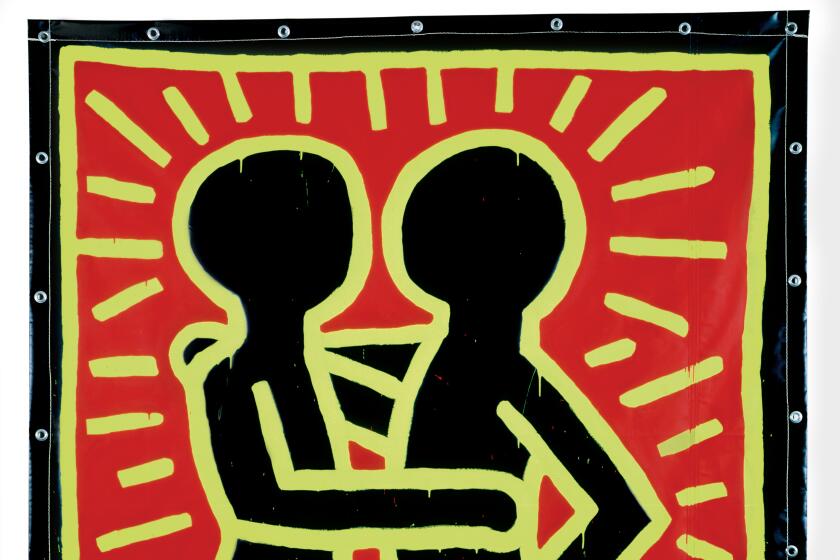

This narratively incoherent but visually abundant mélange is not just a function of single-page compositions. It can be seen in facing-page layouts, as when a handwritten letter by Frederick Douglass defending his right to marry “a lady a few shades lighter in complexion than [himself]” appears directly opposite ledgers that list the human property of black enslaver John C. Stanley. It can be seen in successive pages, as is the case with the 16-page color insert, where minstrel-inspired advertising for commodities such as soap and baking powder gives way to photographs of the folk art and handiwork of enslaved people. And, perhaps most spectacularly, it can be seen on the front cover of the book itself (Figure 1): a riot of color and black-and-white images—36 in all—that practically asks (or begs) the question, What is this “black” in The Black Book ? [7]

In earlier versions of this essay, I was tempted to read such confounding pictorial juxtapositions against the grain of Morrison’s intentions for the project. I assumed she had gathered these different things to make them useful to the present, only to find that their recombination failed to do so. I now think this reading is a mistake, an imposition of the way critics historicize Morrison circa 1987 onto her earlier, far more experimental, engagement with the black past. I now believe that the contingency and discontinuity of The Black Book —in short, its refusal to make a teleological narrative available to readers—is its raison d’être . Morrison was well aware that many of the things she had gathered from collections would perplex readers. But rather than force these artifacts into a historical arc, she made their achronicity, or their out-of-timeness, a feature of the book itself. How else can one explain its strange juxtapositions? They were by design, not some unintended consequence of a historicist project.

Morrison said as much in her contemporaneous essays on the project. In them she identified at least two ways in which her work departed from academic historiography. First, it questioned the ideological limitations of historians’ primary research site: the archive. The problem with conventional histories, Morrison implied, was that they were bound to the legitimizing procedures of institutional archives. As such, histories that relied on archives would inevitably reflect the interests and concerns of the powerful, or those deemed worthy of having their effects saved for posterity. By contrast, Morrison wanted The Black Book to give voice to the masses, or “people who had always been viewed only as percentages.” To do that, she turned her attention from scholars to collectors—that is, “people who had the original raw material documenting our life: posters, letters, newspapers, advertising cards, sheet music, photographs, movie frames, books, artifacts and mementos.” Collectors Middleton “Spike” Harris, Morris Levitt, Roger Furman, and Ernest Smith were respected keepers of such “raw material,” and so they became her preferred entry point into the black past. Morrison paid her collaborators the highest compliment she could think of when she said all four possessed “an intense love for black expression and a zest wholly free of academic careerism.” [8]

The second way Morrison departs from historiography followed from the first. By operating at the margins of institutional legitimation, collectors risked being cut off from institutional recognition. It was debatable whether collectors had a legitimate claim to history at all. Doesn’t The Black Book ultimately only reflect what four collectors of varying interests and dispositions had made available to Morrison? The volume’s most outspoken critic, cultural nationalist Kalamu Ya Salaam, made a similar point when he complained, “[T]o throw all of these images and documents together without a text to explain the meaning, context and original intent does not serve to help us truely [sic] understand what our history, our real history of struggle is about.” [9] Yet Morrison would have welcomed the idea that Salaam did not glean “history,” much less a “history of struggle,” from her book. Historians, Morrison wrote, “habitually leave out life lived by everyday people”; in their writing, they seemed more concerned with “defend[ing] a new idea or destroy[ing] and old one.” [10] She wanted The Black Book to convey something messier, murkier, less institutionally recognized about the black experience in the New World. Rather than a history, she aimed to put together a work of memory.

This goal helps explain The Black Book ’s artifactual resemblance to a scrapbook. Although the print-heavy layout does suggest a catalog, the variety of pictorial forms—iconic, indexical, textual, and otherwise—makes the volume reminiscent of a collection of ephemera. This perception is lent further credence by the book’s introduction, in which none other than Bill Cosby muses:

Suppose a three-hundred-year-old black man had decided, oh, say when he was about ten, to keep a scrapbook—a record of what it was like for himself and his people in these United States. He would keep newspaper articles that interested him, old family photos, trading cards, advertisements, letters, handbills, dreambooks, and posters—all sorts of stuff.

“No such man kept such a book,” Cosby observes, before adding, wryly, “But it’s okay—because it’s here, anyway.” [11] As if passed down through time by a mythic ancestor, The Black Book arrives in the contemporary reader’s hands like an anonymous scrapbook. It contains remnants that are random, ephemeral, incomplete—and, precisely because of that, it comes as close as possible to documenting “Black Life as lived.” The illusion being broached here is that of ordinary remembering, or everyday recollection. A scrapbook is indifferent to the sweeps and arcs (much less teloses) of capital “H” history. All it does is keep what an amateur historian decides to set down as worthy of recalling in the moment of composition. This is why when we “read” a scrapbook, we approach it not as a bird’s-eye chronicle but as what Pierre Nora has called a “site of memory” ( lieu de mémoire ) .[12]

Morrison’s commitment to ordinary remembering is so thoroughgoing that her name appears nowhere on or in The Black Book . The collectors are credited with putting the book together, but even their names are absented from the cover. This is by design, of course, as it supports the illusion that the volume is authorless, the product of a collective mythos rather than a single guiding hand. The one decidedly personal indulgence Morrison allows herself is to insert an oval-shaped, black-and-white portrait of her mother, Ramah Wofford, on the front cover and in an illustrated tableau of anonymous subjects’ portraits .[13] Nothing calls attention to her mother’s figure in either of these locations, or indeed to the fact that it is the ghost editor’s mother. Though she stares out at the reader, so do a number of the other figures among whom she is clustered. Thus, Wofford blends into the composition as just another picture in the collection. She is one memory among many.

Since 1987, critics have interpreted Morrisonian memory, or rememory, as Beloved terms it, as a charge to read the past in the present. The ethos of such criticism presumes a standpoint that can identify how contemporary circumstances are but an extension, or repetitive realization, of the past. Yet, having traced Morrison’s theorization of memory back to The Black Book , I think this is only a partially correct reading of her work. Morrison did believe in something like collective memory, a sense of the past that bound people to one another in the present. But she consistently refused an absolute knowledge of the past, one that confirms what we believe we already know (Sharpe’s ditto ditto, for example). Instead, Morrison supposed that people could access collective memory only through fragments, traces, the detritus and hauntings of history. This stuff, for Morrison, possessed its own historical weight and was not assimilable to confident determinations of the past. In making The Black Book , her intention was not to integrate readers into a discourse of “their history” but to confront them with buried memories—things in which they might not even recognize themselves. [14]

It may be fitting that, as I revised this essay for publication, The Black Book went out of and came back into print. The original 1974 edition had long been out of print, but the 2009 35 th anniversary edition followed course in the late 2010s. That second disappearance turned The Black Book into something like one of the things it reproduces—a relic of the past, a memory among other memories. For a period, copies of the 2009 edition cost upwards of $150, and as much as $2,500, from online and antiquarian booksellers. Yet The Black Book ’s obsolescence was short-lived. With the passing of Morrison in 2018 there came renewed demand for her work, including this long-overlooked book.

The most recent edition (2019) is an artifact of our times. An image of the original cover, showing noticeable shelfwear, is set within a gray frame. The look approximates a well-worn family photo, as if the book itself is being memorialized. Morrison’s name appears front and top-center, her behind-the-scenes work on the project now highlighted in yellow. Yet there is one element that is ghosted from the previous editions: Bill Cosby’s introduction. The reasons for this are obvious, even though the exclusion is unannounced in the text. That the change was made at all—silently, posthumously—confirms Morrison’s intuition that history is not ditto ditto but contingent and discontinuous. Reading The Black Book today is not the same as reading it in 1974, and that is the abiding point.

[1] Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 82. Sharpe’s application of “ditto ditto” to the concept of the archive is adapted from her reading of M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2008).

[2] Sharpe, 104-5.

[3] Toni Morrison, “Behind the Making of The Black Book ,” Black World , February 1974, 89.

[4] Cheryl A. Wall, “Reading The Black Book : Between the Lines of History,” Arizona Quarterly 68, no. 4 (2012): 105-30.

[5] Middleton Harris, et al., The Black Book (New York: Random House, 1974), 68-69.

[6] Ibid., 65.

[7] Ibid., 24-25, 89-104, front cover. The last part of this paragraph riffs on Stuart Hall’s field-shaping essay, “What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?,” in Black Popular Culture , ed. Gina Dent (Seattle: Bay Press, 1992), 21-33.

[8] Toni Morrison, “Rediscovering Black History,” New York Times Book Review , August 11, 1974, 16.

[9] Kalamu ya Salaam, review of The Black Book , by Middleton Harris, et al., Black Books Bulletin , 3, no. 1 (1975): 73.

[10] Morrison, “Behind,” 88.

[11] Bill Cosby, “Introduction,” in The Black Book , v.

[12] Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations, no. 26 (1989): 7-24. The subtitle of my essay, and the distinction between history and memory I draw on here, is indebted to this piece.

[13] Harris, front cover, 196-97.

[14] This point about (non-)recognition echoes Christopher Freeburg’s analysis of The Black Book as fostering a “personalized and contingent” black interiority rather than subjecting readers to a predetermined historical script. Christopher Freeburg, Black Aesthetics and the Interior Life (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2017), 130.

Join the Colloquy

Thing Theory in Literary Studies

View the discussion thread.

Covering books and digital resources across all fields of history

ISSN 1749-8155

Memory and History: Understanding Memory as Source and Subject

Officially, the designated revolution that took place in historical theory since the Second World War is that of the so-called ‘linguistic turn’. But as the postmodernist era in historical theory begins to fade, one begins to wonder if the real revolution in post-war historical theory actually consisted of the rise of memory studies. As the editor of this collection points out in her introduction, ‘Memory is now as familiar a category for historians as politics, war or empire’ (p. 1). The rise of memory studies began at the turn of the 1970s, and the reasons for its rise are multifarious. The Holocaust and the idea of the ‘duty to remember’ undoubtedly played a part, as did some of the new social history of the 1960s; the decline of positivism’s standing in historical method and the ‘cultural turn’ must also be taken into account. One might say that, ‘taking all of the aforementioned factors together, that the ‘memory boom’ of recent years has been over-determined’ (p. 5). Nonetheless, regardless from whence it sprung, the point is that memory is now an inescapable feature of the historiographical landscape.

The collection under review is published as part of The Routledge Guides to Using Historical Sources series; and unsurprisingly, the introduction argues that what distinguishes the volume from other introductions to history and memory is its focus on sources. The volume is divided into three sections, with the first looking at working with oral testimonies; the second deals with memorialisation and commemoration; while the third examines the intersections between individual and collective memory. A select bibliography is provided for all three areas at the end of the book.

One of the key critical issues in the area of memory studies is the reception of memory, with more than one commentator arguing that not enough has been done to address the issue. Most historical studies of memory ‘favour analysis of the textual, visual or oral representations of the past over the pursuit of evidence for responses to those cultural artifacts’ (p. 8). The issue of reception is touched upon in several of the essays in Memory and History . Polly Low looks at the use of inscribed monuments in Ancient Athens to examine not only what the Athenians were attempting to communicate with these monuments; but also whether their attempts were successful. However, the evidence for whether the attempts were successful is slim, and the answer to the question is left somewhat opaque; commemorative monuments ‘may well have been set up with specific intentions, but it does not follow that they were always or only used for those purposes’ (p. 81). In her essay on the role that photography plays in museums, Susan A. Crane asks ‘how did the inclusion of photographs in museums shape the way that diverse audiences, from curators to scholars to the visiting public, interacted with the visual presence of the past?’ (p. 123). But as with Low’s chapter on Athenian monuments, the essay by and large focuses on what those who exhibited the photographs intended them to portray, as opposed to how said photographs were received by their audience. Audience reception is only really addressed in the last two pages of the chapter. Finally, Jason Crouthamel admits on the second page of his chapter on the characterisation of ‘shellshock’ in the Weimar Republic that ‘individual memory proves to be more difficult to locate and analyze’ – although to be fair it should be noted that Crouthamel is more successful in trying to present the reception of memory than either Crane or Low (p. 144). Nonetheless, the impression one gets from Memory and History is that the gauging the reception of memory is a highly problematic affair which even the doyens of the field have struggled to get to grips with. In her introduction Tumblety states that the aim of the volume is to ‘animate and interrogate’ rather than resolve outstanding problems – but with regards to the reception of memory, animation seems thin on the ground.

A theme that runs throughout the entire collection – or ‘haunts’ the volume as Tumblety puts it (like a spectre perhaps?) – is the problematic notion of collective memory. In Lindsey Dodd’s chapter on French oral history during the Second World War (by far the best essay in the book), the author emphasises the importance of ‘cultural scripts’. If there is a gap between individual memories and ‘public’ forms of remembering, then the individual may be left feeling alienated as a result (p. 37). The Allied bombing of France during the Second World War has been described a ‘black hole’ with regard to French collective memory of the war: Dodd’s doctoral research found that it was fairly well remembered at a local/individual level, but a silence prevails at a public and institutional level (p. 37). On Dodd’s reading, public memory acts as a kind of ‘jelly mould’ that shapes personal memories; with no such mould to hand, the individuals memories will be shapeless, and in the case of Dodd’s interviewee, coalesce around other psychological landmarks.

Continuing the theme, Rosanne Kennedy’s essay ‘Memory, history and the law’ examines the role of the law in shaping collective memory. The Nuremberg trials chose documentation over testimony with regard to the evidence, and therefore did not significantly contribute to the collective memory of the Holocaust. By contrast, the trial of Albert Eichmann in 1961 was designed almost as more of an exercise in collective memory than as a trial (1) ; lead prosecutor Gideon Hauser allowed witnesses to present narratives – opposed to the usual courtroom fare of question and answer – and the trial was significant in ‘bringing Holocaust survivors, who had been marginalised in Israeli society, into the forefront of national consciousness, and making the Holocaust central to national identity and remembrance in Israel’ (p. 55). As Peter Novick has noted, ‘collective memory works selectively; it is a form of myth-making that is shaped by the needs of groups, and the formation of group identity, in the present’ (p. 57). A historical approach to the past recognises the complexity of events, whereas memory tends to simplify – shaping the past to fit within the jelly mould of a cultural script. I will return to the tension between ‘history’ and ‘memory’ shortly.

Another theme raised in this collection is the idea of visual memory. Franziska Seraphim makes the obvious, but nonetheless important point that images function differently from texts; ‘we see with memory … Images tend to tap into the habits of mind (as distinct from critical thinking) … to make sense’ (p. 98). Similarly, Joan Tumblety documents how the image of resistance fighters in post-war France was cultivated through films which were ‘often publically funded and controlled’ (p. 109). Such films functioned as historical sources ‘in the absence of much written material about that had been of necessity secret’ (p. 109). Tumblety also examines the written form of memory in her essay, through an examination of the challenge to official memory via the written memoirs of those ‘with an axe to grind about the present regime and its alleged manipulation of the past’ (p. 115).

The final essay deals with the idea of memory and materiality. (2) Susan M. Stabile puts it that a palimpsest is not only a material object, but also a metaphor for memory. (3) The original ‘inscription’ – the act itself – is erased and forgotten, and thus lived experience is deposited in memory, and reposited in narrative (p. 194). But memory changes with each iteration, ‘shaped by the moment in which it is recalled. That recollection will be overwritten at a future moment, shadowed by a new memory’ (p. 194). The past therefore, only exists as a fragment or ruin – or if you’re a fan of Hayden White, as synecdoche. But traces of the past survive in what has come to be known as a ‘cumulative palimpsest’. In the words of Geoff Bailey, ‘successive episodes of deposition … remain superimposed one upon the other without loss of evidence, but are so re-worked and mixed together that it is difficult or impossible to separate them out into their original constituents’ (p. 195). Stabile’s essay examines 19th-century antiquarian John Watson, and in particular his perpetuation of colonial ruins through a relic box. Material culture is a palimpsest – ‘the literal things that people leave behind…material culture embodies and evokes memory’ (p. 197).

I spoke above of the tension between history – as in academic history – and memory. The historian has often been sceptical of oral testimony; Anna Wieviorka makes the case that the Eichmann trial was crucial in legitimising testimony as an epistemically acceptable form of truth telling about the past – and that this had a negative impact on historical writing. The Holocaust thus came ‘to be defined as a succession of individual experiences with which the public was supposed to identify’ (p. 56). The problem is that this is not a particularly good foundation for writing history; D. J. Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners is probably the most high profile example of this. One can learn a lot from listening to personal testimonies – ‘but does one learn history?’ (p. 57). At the other end of the pendulum, Pierre Nora felt that history had been a bad thing for memory; ‘true’ memory has been obliterated by ‘modern’ memory – the latter consisting of ‘the practise of oral history, heritage, commemoration, archives and genealogy’ (p. 160). There are some commentators however, who occupy a position somewhere between these two poles, James Young feels that the distinction between history and memory – ‘history as that which happened, memory as that which is remembered of what happened’ – is somewhat forced (p. 58). Similarly, Hannah Ewence contends at the start of her essay that ‘Nora establishes between history and memory appear fabricated and unnecessarily provocative, overlooking the ways in which history and memory can, and do, successfully overlap and crossfertilize’ (p. 160). Even ‘atomized memory’ uses the materials and milestones of ‘official’ memory to construct and reconstruct the past (p. 161).

It is the tension between ‘history’ and ‘memory’ that provides the jumping off point for Ewence’s essay ‘Memories of suburbia: autobiographical fiction and minority narratives’. Ewence studies three autobiographical novels to not only make the point that history, memory and fiction share points of similarity; but also as a means of introducing the idea of the ‘spatial turn’ – ‘ideas about space and place are encoded with individual and collective identity(ies), memories and histories’ (p. 162). All three novels contain autobiographical elements, but their respective authors have resisted attempts to draw explicit parallels with their own lives – and the fact that they are not straightforward autobiographies is one of their strengths, as ‘Fiction alone has the capacity, perhaps the audacity, to challenge history … whilst autobiography typically prefers to “save face”’ (p. 169). In all three novels, a clear sense of space is ‘fundamental within their writing as a site for exploring history, memory and identity’ (p. 172). Fiction allows authors to explore and deposit memory, and readers can draw upon their own memories to evoke their own past experiences; and to an extent it allows the negation of power structures that determine what history can be told by whom in a way that sometimes oral history cannot.

One of the interesting things about this collection is the lack of reference made to those we might call some of the doyens of postmodernism. I recently had a rather spirited exchange with Alun Munslow in these pages over whether postmodernism was on the wane or not. (4) It could be argued that the absence of the likes of Derrida and Barthes from these pages might be taken as an indicator that the postmodernist turn in historical theory is on the decline. In a review of a similar work on memory a few years ago, Patrick Hutton noted that the ‘diminishing enthusiasm among historians for postmodernist theory’ might prompt a ‘return to the old and very practical historiographical problems of testimony, evidence, and interpretation’. (5) The approach and contents of Memory and History would suggest that this has indeed taken place.

Memory and History provides an interesting cross-section of essays from the front-line of memory studies; but its broadly based empiricist tone is both the book’s main strength and weakness, depending on your predilections in these matters. If you tend towards the view that historical theory should be aligned more closely with historical practice, then this collection of essays will be seen as a step in the right direction. If on the other hand, one inclines towards what we might call the Wulf Kansteiner/ Jörn Rüsen end of the spectrum, then there will be a woeful lack of theory in this one for your tastes, and a quick retreat to the pages of History and Memory journal may be necessary.

- I am aware of the anachronism of using the term ‘collective memory’ here. Back to (1)

- Although this is addressed tangentially in chapters one and four as well. Back to (2)

- For the uninitiated, a palimpsest is ‘Paper, parchment, or other writing material designed to be reusable after any writing on it has been erased’. Definition taken from the Oxford English Dictionary . Back to (3)

- See < http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1356 > [accessed 3 June 2013]. Back to (4)

- Patrick H. Hutton, ‘Memories of trauma: problems of interpretation’, History and Theory , 43 (2004), 258. Back to (5)

Author's Response

I would like to thank the reviewer for his close reading of the volume. It is not my intention in this response to take issue with any element of the review; rather to reflect on a few of the general comments made in it about the apparent wane of (postmodernist) theorising in the discipline of history. I agree with the reviewer that the edited volume is broadly empiricist in tone, as well as in method. And I think he is right to suggest that it will more readily satisfy those who like to see their theory closely aligned with historical practice. This is indeed deliberate, not least because Memory and History sits within the Routledge Using Historical Sources series, whose remit is not to exclude – if neither solely to address – an audience of undergraduate and post-graduate students, as well as non-specialist scholars working in the Anglophone university sphere, who may well turn to the book for pointers about how to approach the study of memory through extant primary material rather than for a theoretical Weltanschauung . That is why the chapters consider distinct genres of source – letters, photography, fiction, trial testimony, etc. – as well as disparate periods and places.

Yet, as the reviewer suggests, the request for some kind of systematic theorization within memory studies has been a common refrain in the scholarly literature. This is not necessarily a demand for theorising memory itself (although that has been common enough, especially where collective memory is concerned); rather, it is a conviction that getting a handle on the multiple, and perhaps interpenetrating analytical frameworks within which ‘memory’ of one kind or another has been, or can be, understood across a range of disciplines, enables a more rigorous and dialogic engagement among scholars.(1) And it has also been a plea for a historicisation of the notion of memory itself, as the introduction to the volume explores.

What strikes me about the most serious, systematic and – above all – influential attempts in English to theorize memory in this way, however, is that they have emanated from sociologists, or sociologically inclined historians – such as Jeffrey Olick and Wulf Kansteiner – who generally bypass the long-lived engagement within literary criticism and some kinds of intellectual history with (largely French) structuralist or post-structuralist theories of language. Thus while a few foundational works in the field draw in some measure on the work of Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida (and these theorists find some echo in current scholarship), I would say that the loudest scholarly conversations in memory studies over the last two decades or so – precisely the period of the cross-disciplinary fight over the value of postmodernist approaches – barely mention them. (2) Instead, it is the significance for the field of the writings of early sociologists such as Maurice Halbwachs and Emile Durkheim that is stressed in the great volume of scholarly writing on memory. And although Marek Tamm has recently championed the semiotically inclined works of continental European writers on memory such as Astrid Erll, the central plank of his argument – that historians would do well to deploy a notion of ‘mnemohistory’ in their work; in other words to become attuned to ‘the two levels he [the historian] is simultaneously working on: the historicisation of the phenomenon of the past and the historicisation of his own work’ – does not depend overtly on post-structuralist insights.(3)

Clearly, one does not need postmodernism (or its component part, post-structuralism) in order to theorise memory. And neither does one need postmodernism, I would argue, in order to identify and to explain the impact of the so-called linguistic turn on the development of memory studies and on the historical discipline as a whole, however much scholars continue to conflate the ‘linguistic turn’ with ‘[t]he deconstructionist impulse of postmodernism’.(4) The epistemologically radical refusal of objective truth, so associated with post-structuralist approaches to language, is worlds away from the kind of linguistic turn made famous after the late 1960s by the outstanding historian of early modern political thought, Quentin Skinner, whose methodology drew instead on the ‘speech act’ theories of British analytical philosopher John Austin.(5) In any case, the generalisation within the discipline of the insight that our evidence is almost always in some sense rhetorically constructed – an appreciation that has undoubtedly nourished the scholarly memory boom – is as characteristic of what some postmodernist historians call ‘constructivist’ history writing as of ‘deconstructionist’ varieties.(6) It is not so much that postmodernism is on the wane in studies of memory, as that it never secured a foothold there in the first place.

Ultimately, I am in two minds about the value of systematic theorising. While rigour in the thinking and writing about memory – or any subject – should prevent the facile replication of buzz words wrenched free from any meaningful intellectual or other context, I sometimes wonder whether the drive towards systematisation that characterises some sociological investigation on the subject might not lead to a new positivism for the 21st century, something that in fact runs counter to the very scholarly trends that enabled the rise of ‘memory studies’ in the first place, at least among mainstream historians. Like the temptation to draw on recent discoveries in neuroscience as a potential arbiter of ‘what memory really means’, there is a danger that we permit a new essentialism to take hold.(7) Better, I would think, for historians to work towards a more conceptually reflective and robust kind of empiricism. This is what is offered by Neil Gregor in his recent social history of memory in post-war Nuremberg, an ‘empirically saturated study’ of grassroots memorial cultures whose immersion in source material that speaks to the words and deeds of those enmeshed in local networks, manages practically to collapse – and thus to resolve – one entrenched methodological divide in the field of memory, that between the representational and the experiential. (8)

(1) See The Collective Memory Reader , ed. Jeffrey K. Olick, Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, and Daniel Levy (Oxford and New York, NY, 2011), and especially the lengthy attempt to systematise what – and how – we know about memory in its introduction, pp. 3–62.

(2) Aleida Assmann, Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives (Cambridge, 2011 [orig. German edition 1999]) draws on Roland Barthes’ theories of the image and Jacques Derrida’s approach to the ‘archive’. In Caroline Wake, ‘Regarding the recording: the viewer of video testimony, the complexity of coprescence and the possibility of tertiary witnessing’, History and Memory, 25, 1 (2013), 111–44, the ideas of both Barthes and Derrida, despite being cited, take a back seat to the author’s engagement with the works of intellectual historian Dominick LaCapra and sociologist Shanyang Zhao.

(3) Marek Tamm, ‘Beyond history and memory: new perspectives in memory studies’, History Compass, 11, 6 (2013), 458–73; here 464. Tamm is consciously building on the approach of Jan Assmann, which in turn is in part derived from the philosophy of Hans-Georg Gadamer.

(4) Gavriel D. Rosenfeld, ‘A Looming crash or a soft landing? Forecasting the future of the memory “industry”’, The Journal of Modern History, 81, 1 (2009), 134. See also Richard J. Evans, In Defence of History (London, 1997), who seems to conflate postmodernism with what is often called the ‘new cultural history’, pp. 243–9, in his discussion of the work of Natalie Zemon Davis and Robert Darnton.

(5) Quentin Skinner, ‘Meaning and understanding in the History of Ideas’, History and Theory , 8, 1 (1969), 3–53.

(6) These are two of the main categories used to describe tendencies within historical scholarship in The Nature of History Reader, ed. Keith Jenkins and Alun Munslow (London, 2004).

(7) For engagement with neuroscience, see several contributions to Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates , ed. Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz (New York, NY, 2010).

(8) Neil Gregor, Haunted City: Nuremberg and the Nazi Past, (New Haven, CT and London, 2008), p. 20.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Memory vs. History: On the Neverending Struggle to See Clearly Into the Past

Sarisha kurup tries to map the personal over the public.

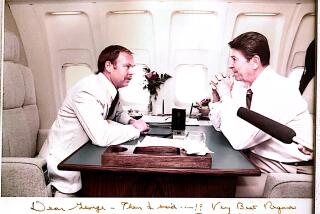

In autumn of 1993, as River Phoenix convulsed on a Los Angeles sidewalk, his body riddled with cocaine and morphine, my father sat somewhere in San Francisco, only four years older than the child star who would forever be 23.

Bill Clinton had just become president and a van had exploded outside the World Trade Center, killing six and injuring over 1,000. Rodney King testified against the four LAPD officers that brutally beat him, sending two of them to prison. Rivers flooded the American Midwest all April; the IRS granted the Church of Scientology full tax exemption; and my father tucked himself away in the Silicon Valley, making computer chips for Cirrus Logic.

My mother tells me these details over a broken phone signal. She still lives in the Bay Area, where she moved in August of 1994, and met my father only a month later. Today I am in a hotel room in Amsterdam, and I can barely ask her any of my questions because we rarely talk about him directly. I find myself stuttering, the words dissolving on my tongue. The easiest way to ask these questions is in a steady, emotionless voice, like an automated message.

What he was doing that autumn, how he spent his free time, who he called on an empty evening, what time he fell asleep, if he slept much at all—it’s all a mystery. He never kept any journals. He rarely changed his wardrobe throughout his adult life, so I can imagine, at least, how he dressed. Light wash jeans, black or brown belt, the kind of polo shirts where the shoulders hang down to mid upper arm. The printed photos in our family albums are not dated, and there are few of my father before he met my mother. She was always the photographer.

Photos of River Phoenix in 1993 are plentiful and, now, strange. His hair is long, blonde—the kind of hair one looks at in hindsight and laughs—his smile is mischievous. He doesn’t look like he should be in the last year of life. And yet, the night before Halloween, outside a club in Los Angeles, his younger brother placed a shaky 911 call and by the time the paramedics had arrived, River Phoenix was in cardiac arrest.

When people die young, it is often said that they are frozen in time. That while all their peers age and turn soft and grey, they will forever exist in photos and our minds just as they did in their last days. But I think there are people like River Phoenix, people who are so famous whose names roll off everyone’s tongues, people who, when they die, freeze even the time around them. We don’t all understand time the way historians do, and even they cannot control all of what we remember. Memory is inexplicable and selective, and nostalgia is strong. As the past collapses and scatters into something messier, less linear, we collectively remember only the road markers, the people and the things that cut the deepest.

Nineteen ninety-three will always belong to River Phoenix: frozen the moment he lost consciousness on the filthy sidewalk of the Sunset Strip. My memories do not extend to 1993, and yet when I think of that year I think of Johnny Depp and his band singing inside The Viper Room as River Phoenix slips from life just steps away, without them knowing, out in the evening air.

They found JFK Jr.’s body 120 feet below the surface of the Atlantic in July of 1999, only a few months after I was born. My father lived with me and my mother in a rented house then. On the day that John Jr’s plane went down the house was crowded with relatives who stumbled over each other in the little space, cooing and clapping to get the attention of the new baby. My father had started his own company only two years earlier. I understood very little about technology growing up, and still can’t wrap my head around the way most machines work, so I could never explain much to people who asked what it was that my father did. But I could say he helmed a tech company that was called Vitalect. There are photos from this period in his life, and videos too. My mother was the videographer, and the moving images are shot from her perspective. When you watch them you can see the way she must have seen us—a thirty-three-year-old man and a six-month-old baby, both with the same dimple indented into our left cheeks.

When his plane hit the Atlantic, JFK Jr. died on impact. They didn’t find his body until three days later. At the site of the wreckage he was still buckled in, trapped in the pilot’s seat. His family scattered his ashes in the Atlantic. I always thought this was strange—giving him back to the very thing that took him.

We scattered my father’s ashes at the base of the orange tree in our backyard. He loved that tree. It was heavy with fruit each December without fail, and on early grey mornings you could find him there, reaching up among the branches.