- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Booker T. Washington

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 18, 2023 | Original: October 29, 2009

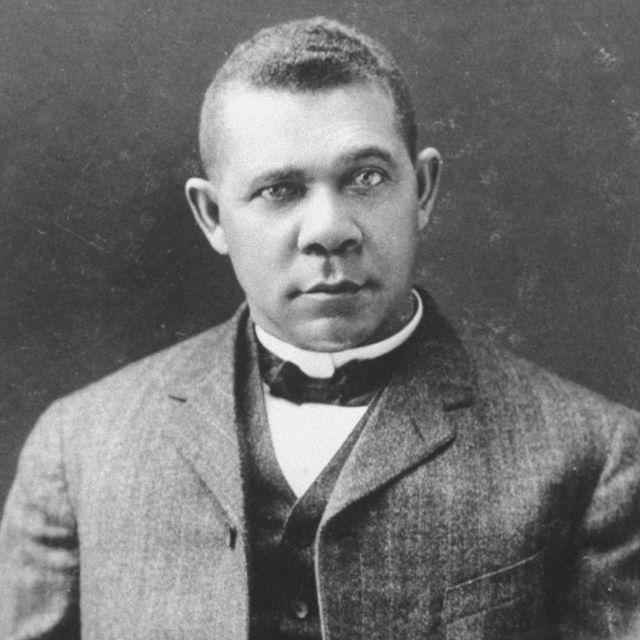

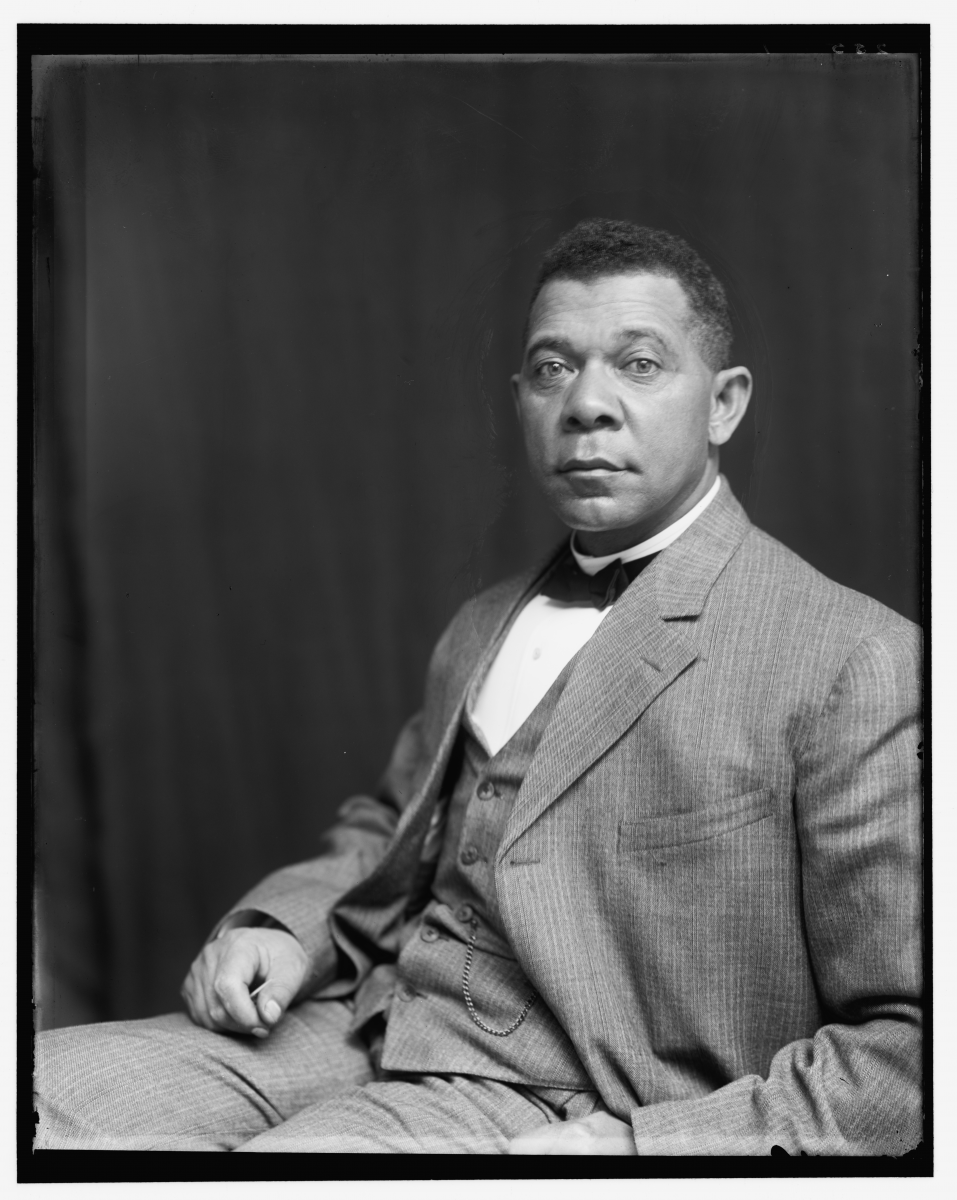

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) was born into slavery and rose to become a leading African American intellectual of the 19 century, founding Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (Now Tuskegee University) in 1881 and the National Negro Business League two decades later. Washington advised Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. His infamous conflicts with Black leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois over segregation caused a stir, but today, he is remembered as the most influential African American speaker of his time.

Booker T. Washington’s Parents and Early Life

Booker Taliaferro Washington was born on April 5, 1856 in a hut in Franklin County, Virginia . His mother was a cook for the plantation’s owner. His father, a white man, was unknown to Washington. At the close of the Civil War , all the enslaved people owned by James and Elizabeth Burroughs—including 9-year-old Booker, his siblings, and his mother—were freed. Jane moved her family to Malden, West Virginia. Soon after, she married Washington Ferguson, a free Black man.

Booker T. Washington’s Education

In Malden, Washington was only allowed to go to school after working from 4-9 AM each morning in a local salt works before class. It was at a second job in a local coalmine where he first heard two fellow workers discuss the Hampton Institute, a school for formerly enslaved people in southeastern Virginia founded in 1868 by Brigadier General Samuel Chapman. Chapman had been a leader of Black troops for the Union during the Civil War and was dedicated to improving educational opportunities for African Americans.

In 1872, Washington walked the 500 miles to Hampton, where he was an excellent student and received high grades. He went on to study at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., but had so impressed Chapman that he was invited to return to Hampton as a teacher in 1879. It was Chapman who would refer Washington for a role as principal of a new school for African Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama : The Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, today’s Tuskegee University. Washington assumed the role in 1881 at age 25 and would work at The Tuskegee Institute until his death in 1915.

It was Washington who hired George Washington Carver to teach agriculture at Tuskegee in 1896. Carver would go on to be a celebrated figure in Black history in his own right, making huge advances in botany and farming technology.

Booker T. Washington Beliefs And Rivalry with W.E.B. Du Bois

Life in the post- Reconstruction era South was challenging for Black people. Discrimination was rife in the age of Jim Crow Laws . Exercising the right to vote under the 15 Amendment was dangerous, and access to jobs and education was severely limited. With the dawn of the Ku Klux Klan , the threat of retaliatory violence for advocating for civil rights was real.

In perhaps his most famous speech, given on September 18, 1895, Washington told a majority white audience in Atlanta that the way forward for African Americans was self-improvement through an attempt to “dignify and glorify common labor.” He felt it was better to remain separate from whites than to attempt desegregation as long as whites granted their Black countrymen and women access to economic progress, education, and justice under U.S. courts:

"The wisest of my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than artificial forcing. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than to spend a dollar in an opera house."

His speech was sharply criticized by W.E.B. Du Bois , who repudiated what he called “The Atlanta Compromise” in a chapter of his famous 1903 book, “The Souls of Black Folk.” Opposition to Washington’s views on race inspired the Niagara Movement (1905-1909). Du Bois would go on to found the NAACP in 1909.

Because of Washington’s outsized stature in the Black community, dissenting views were strongly squashed. Du Bois and others criticized Washington’s harsh treatment of rival Black newspapers and Black thinkers who dared to challenge his opinions and authority.

Books By Booker T. Washington

Washington, a famed public speaker known for his sense of humor , was also the author of five books:

· “The Story of My Life and Work” (1900)

· “Up From Slavery” (1901)

· “The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery” (1909)

· “My Larger Education” (1911)

· “The Man Farthest Down” (1912)

Booker T. Washington: First African American in the White House

Booker T. Washington became the first African American to be invited to the White House in 1901, when President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to dine with him. It caused a huge uproar among white Americans—especially in the Jim Crow South—and in the press, and came on the heels of the publication of his autobiography, “Up From Slavery.” But Roosevelt saw Washington as a brilliant advisor on racial matters, a practice his successor, President William Howard Taft , continued.

Booker T. Washington Death And Legacy

Booker T. Washington’s legacy is complex. While he lived through an epic sea change in the lives of African Americans, his public views supporting segregation seem outdated today. His emphasis on economic self-determination over political and civil rights fell out of favor as the views of his largest critic, W.E.B. Du Bois, took root and inspired the civil rights movement . We now know that Washington secretly financed court cases that challenged segregation and wrote letters in code to defend against lynch mobs. His work in the field of education helped give access to new hope for thousands of African Americans.

By 1913, at the dawn of the administration of Woodrow Wilson , Washington had largely fallen out of favor. He remained at the Tuskegee Institute until congestive heart failure ended his life on November 14, 1915. He was 59.

Washington left behind a vastly improved Tuskegee Institute with over 1,500 students, a faculty of 200 and an endowment of nearly $2 million to continue to carry on its work.

Booker T. Washington. Biography.com The Debate Between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Frontline . Jim Crow Stories: Booker T. Washington. Thirteen.org. Booker T. Washington. Britannica .

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Booker T. Washington

(1856-1915)

Who Was Booker T. Washington?

Born to an enslaved person on April 5, 1856, Washington's life had little promise early on. In Franklin County, Virginia, as in most states prior to the Civil War, the child of an enslaved person also became enslaved. Washington's mother, Jane, worked as a cook for plantation owner James Burroughs. His father was an unknown white man, most likely from a nearby plantation. Washington and his mother lived in a one-room log cabin with a large fireplace, which also served as the plantation’s kitchen.

At an early age, Washington went to work carrying sacks of grain to the plantation’s mill. Toting 100-pound sacks was hard work for a small boy, and he was beaten on occasion for not performing his duties satisfactorily. Washington's first exposure to education was from the outside of a schoolhouse near the plantation; looking inside, he saw children his age sitting at desks and reading books. He wanted to do what those children were doing, but he was enslaved, and it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write.

After the Civil War, Washington and his mother moved to Malden, West Virginia, where she married freedman Washington Ferguson. The family was very poor, and nine-year-old Washington went to work in the nearby salt furnaces with his stepfather instead of going to school. Washington's mother noticed his interest in learning and got him a book from which he learned the alphabet and how to read and write basic words. Because he was still working, he got up nearly every morning at 4 a.m. to practice and study. At about this time, Washington took the first name of his stepfather as his last name, Washington.

In 1866, Washington got a job as a houseboy for Viola Ruffner, the wife of coal mine owner Lewis Ruffner. Mrs. Ruffner was known for being very strict with her servants, especially boys. But she saw something in Washington — his maturity, intelligence and integrity — and soon warmed up to him. Over the two years he worked for her, she understood his desire for an education and allowed him to go to school for an hour a day during the winter months.

In 1872, Washington left home and walked 500 miles to Hampton Normal Agricultural Institute in Virginia. Along the way, he took odd jobs to support himself. He convinced administrators to let him attend the school and took a job as a janitor to help pay his tuition. The school's founder and headmaster, General Samuel C. Armstrong, soon discovered the hardworking Washington and offered him a scholarship, sponsored by a white man. Armstrong had been a commander of a Union African American regiment during the Civil War and was a strong supporter of providing newly freed enslaved people with a practical education. Armstrong became Washington's mentor, strengthening his values of hard work and strong moral character.

Washington graduated from Hampton in 1875 with high marks. For a time, he taught at his old grade school in Malden, Virginia, and attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. In 1879, he was chosen to speak at Hampton's graduation ceremonies, where afterward General Armstrong offered Washington a job teaching at Hampton. In 1881, the Alabama legislature approved $2,000 for a "colored" school, the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now known as Tuskegee University). General Armstrong was asked to recommend a white man to run the school but instead recommended Washington. Classes were first held in an old church, while Washington traveled all over the countryside promoting the school and raising money. He reassured white people that nothing in the Tuskegee program would threaten white supremacy or pose any economic competition to white people.

Tuskegee Institute

Under Washington's leadership, Tuskegee became a leading school in the country. At his death, it had more than 100 well-equipped buildings, 1,500 students, a 200-member faculty teaching 38 trades and professions, and a nearly $2 million endowment. Washington put much of himself into the school's curriculum, stressing the virtues of patience, enterprise, and thrift. He taught that economic success for African Americans would take time, and that subordination to white people was a necessary evil until African Americans could prove they were worthy of full economic and political rights. He believed that if African Americans worked hard and obtained financial independence and cultural advancement, they would eventually win acceptance and respect from the white community.

Beliefs and the 'Atlanta Compromise'

In 1895, Washington publicly put forth his philosophy on race relations in a speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, known as the "Atlanta Compromise." In his speech, Washington stated that African Americans should accept disenfranchisement and social segregation as long as white people allow them economic progress, educational opportunity and justice in the courts.

Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois

This started a firestorm in parts of the African American community, especially in the North. Activists like W.E.B. Du Bois (who was working as a professor at Atlanta University at the time) deplored Washington's conciliatory philosophy and his belief that African Americans were only suited to vocational training. Du Bois criticized Washington for not demanding equality for African Americans, as granted by the 14th Amendment , and subsequently became an advocate for full and equal rights in every realm of a person's life.

Though Washington had done much to help advance many African Americans, there was some truth in the criticism. During Washington's rise as a national spokesperson for African Americans, they were systematically excluded from the vote and political participation through Black codes and Jim Crow laws as rigid patterns of segregation and discrimination became institutionalized throughout the South and much of the country.

White House Dinner With Theodore Roosevelt

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to the White House, making him the first African American to be so honored. But the fact that Roosevelt asked Washington to dine with him (inferring the two were equal) was unprecedented and controversial, causing an ferocious uproar among white people.

Both President Roosevelt and his successor, President William Howard Taft , used Washington as an adviser on racial matters, partly because he accepted racial subservience. His White House visit and the publication of his autobiography, Up from Slavery , brought him both acclaim and indignation from many Americans. While some African Americans looked upon Washington as a hero, others, like Du Bois, saw him as a traitor. Many Southern white people, including some prominent members of Congress, saw Washington's success as an affront and called for action to put African Americans "in their place."

With the aid of ghostwriters, Washington wrote a total of five books: The Story of My Life and Work (1900), Up from Slavery (1901), The Story of the Negro: The Rise of the Race from Slavery (1909), My Larger Education (1911), and The Man Farthest Down (1912).

Death and Legacy

Washington was a complex individual, who lived during a precarious time in advancing racial equality. On one hand, he was openly supportive of African Americans taking a "back seat" to white people, while on the other he secretly financed several court cases challenging segregation. By 1913, Washington had lost much of his influence. The newly inaugurated Wilson administration was cool to the idea of racial integration and African American equality.

Washington remained the head of Tuskegee Institute until his death on November 14, 1915, at the age of 59, of congestive heart failure.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Booker T. Washington

- Birth Year: 1856

- Birth date: April 5, 1856

- Birth State: Virginia

- Birth City: Hale's Ford

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Booker T. Washington was one of the foremost African American leaders of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, founding the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute.

- Civil Rights

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C.

- Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute

- Death Year: 1915

- Death date: November 14, 1915

- Death State: Alabama

- Death City: Tuskegee

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Booker T. Washington Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scholars-educators/booker-t-washington

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 23, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has had to overcome while trying to succeed.

- Those who have accomplished the greatest results are those who never grow excited or lose self control, but are always calm, self possessed, patient and polite.

- No race can prosper till it learns there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem.

- Excellence is to do a common thing in an uncommon way.

- You can't hold a man down without staying down with him.

- The negro has the right to study law, but success will come to the race sooner if it produces intelligent, thrifty farmers, mechanics to support the lawyers.

- Opportunities never come a second time, nor do they wait for our leisure.

- No man who continues to add something to the material, intellectual and moral well being of the place in which he lives is left long without proper reward.

- I shall allow no man to belittle my soul by making me hate him.

- Great men cultivate love ... only little men cherish a spirit of hatred.

- If you want to lift yourself up, lift up someone else.

Black History

Jesse Owens

Alice Coachman

Wilma Rudolph

Tiger Woods

Deb Haaland

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Octavia Spencer

Inventor Garrett Morgan’s Lifesaving 1916 Rescue

Get to Know 5 History-Making Black Country Singers

"Of Booker T. Washington and Others," from The Souls of Black Folk

- Civil Rights Movement

- Race and Equality

- Social Reform

No study questions

No related resources

Source: Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. “Of Booker T. Washington and Others,” in The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches , 41-59. United States: A. C. McClurg & Company, 1903. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Souls_of_Black_Folk/7psUAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 .

From birth till death enslaved; in word, in deed, unmanned! Hereditary bondsmen! Know ye not Who would be free themselves must strike the blow? BYRON.

EASILY the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington. It began at the time when war memories and ideals were rapidly passing; a day of astonishing commercial development was dawning; a sense of doubt and hesitation overtook the freedmen's sons,—then it was that his leading began. Mr. Washington came, with a simple definite programme, at the psychological moment when the nation was a little ashamed of having bestowed so much sentiment on Negroes, and was concentrating its energies on Dollars. His programme of industrial education, conciliation of the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights, was not wholly original; the Free Negroes from 1830 up to war-time had striven to build industrial schools, and the American Missionary Association had from the first taught various trades; and Price and others had sought a way of honorable alliance with the best of the Southerners. But Mr. Washington first indissolubly linked these things; he put enthusiasm, unlimited energy, and perfect faith into his programme, and changed it from a by-path into a veritable Way of Life. And the tale of the methods by which he did this is a fascinating study of human life.

It startled the nation to hear a Negro advocating such a programme after many decades of bitter complaint; it startled and won the applause of the South, it interested and won the admiration of the North; and after a confused murmur of protest, it silenced if it did not convert the Negroes themselves.

To gain the sympathy and coöperation of the various elements comprising the white South was Mr. Washington's first task; and this, at the time Tuskegee was founded, seemed, for a black man, well-nigh impossible. And yet ten years later it was done in the word spoken at Atlanta: "In all things purely social we can be as separate as the five fingers, and yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress ." This "Atlanta Compromise" is by all odds the most notable thing in Mr. Washington's career. The South interpreted it in different ways: the radicals received it as a complete surrender of the demand for civil and political equality; the conservatives, as a generously conceived working basis for mutual understanding. So both approved it, and to-day its author is certainly the most distinguished Southerner since Jefferson Davis, and the one with the largest personal following.

Next to this achievement comes Mr. Washington's work in gaining place and consideration in the North. Others less shrewd and tactful had formerly essayed to sit on these two stools and had fallen between them; but as Mr. Washington knew the heart of the South from birth and training, so by singular insight he intuitively grasped the spirit of the age which was dominating the North. And so thoroughly did he learn the speech and thought of triumphant commercialism, and the ideals of material prosperity, that the picture of a lone black boy poring over a French grammar amid the weeds and dirt of a neglected home soon seemed to him the acme of absurdities. One wonders what Socrates and St. Francis of Assisi would say to this.

And yet this very singleness of vision and thorough oneness with his age is a mark of the successful man. It is as though Nature must needs make men narrow in order to give them force. So Mr. Washington's cult has gained unquestioning followers, his work has wonderfully prospered, his friends are legion, and his enemies are confounded. To-day he stands as the one recognized spokesman of his ten million fellows, and one of the most notable figures in a nation of seventy millions. One hesitates, therefore, to criticise a life which, beginning with so little, has done so much. And yet the time is come when one may speak in all sincerity and utter courtesy of the mistakes and shortcomings of Mr. Washington's career, as well as of his triumphs, without being thought captious or envious, and without forgetting that it is easier to do ill than well in the world.

The criticism that has hitherto met Mr. Washington has not always been of this broad character. In the South especially has he had to walk warily to avoid the harshest judgments,—and naturally so, for he is dealing with the one subject of deepest sensitiveness to that section. Twice—once when at the Chicago celebration of the Spanish-American War he alluded to the color-prejudice that is "eating away the vitals of the South," and once when he dined with President Roosevelt—has the resulting Southern criticism been violent enough to threaten seriously his popularity. In the North the feeling has several times forced itself into words, that Mr. Washington's counsels of submission overlooked certain elements of true manhood, and that his educational programme was unnecessarily narrow. Usually, however, such criticism has not found open expression, although, too, the spiritual sons of the Abolitionists have not been prepared to acknowledge that the schools founded before Tuskegee, by men of broad ideals and self-sacrificing spirit, were wholly failures or worthy of ridicule. While, then, criticism has not failed to follow Mr. Washington, yet the prevailing public opinion of the land has been but too willing to deliver the solution of a wearisome problem into his hands, and say, "If that is all you and your race ask, take it."

Among his own people, however, Mr. Washington has encountered the strongest and most lasting opposition, amounting at times to bitterness, and even to-day continuing strong and insistent even though largely silenced in outward expression by the public opinion of the nation. Some of this opposition is, of course, mere envy; the disappointment of displaced demagogues and the spite of narrow minds. But aside from this, there is among educated and thoughtful colored men in all parts of the land a feeling of deep regret, sorrow, and apprehension at the wide currency and ascendancy which some of Mr. Washington's theories have gained. These same men admire his sincerity of purpose, and are willing to forgive much to honest endeavor which is doing something worth the doing. They coöperate with Mr. Washington as far as they conscientiously can; and, indeed, it is no ordinary tribute to this man's tact and power that, steering as he must between so many diverse interests and opinions, he so largely retains the respect of all.

But the hushing of the criticism of honest opponents is a dangerous thing. It leads some of the best of the critics to unfortunate silence and paralysis of effort, and others to burst into speech so passionately and intemperately as to lose listeners. Honest and earnest criticism from those whose interests are most nearly touched,—criticism of writers by readers, of government by those governed, of leaders by those led,—this is the soul of democracy and the safeguard of modern society. If the best of the American Negroes receive by outer pressure a leader whom they had not recognized before, manifestly there is here a certain palpable gain. Yet there is also irreparable loss,—a loss of that peculiarly valuable education which a group receives when by search and criticism it finds and commissions its own leaders. The way in which this is done is at once the most elementary and the nicest problem of social growth. History is but the record of such group-leadership; and yet how infinitely changeful is its type and character! And of all types and kinds, what can be more instructive than the leadership of a group within a group?—that curious double movement where real progress may be negative and actual advance be relative retrogression. All this is the social student's inspiration and despair.

Now in the past the American Negro has had instructive experience in the choosing of group leaders, founding thus a peculiar dynasty which in the light of present conditions is worth while studying. When sticks and stones and beasts form the sole environment of a people, their attitude is largely one of determined opposition to and conquest of natural forces. But when to earth and brute is added an environment of men and ideas, then the attitude of the imprisoned group may take three main forms,—a feeling of revolt and revenge; an attempt to adjust all thought and action to the will of the greater group; or, finally, a determined effort at self-realization and self-development despite environing opinion. The influence of all of these attitudes at various times can be traced in the history of the American Negro, and in the evolution of his successive leaders.

Before 1750, while the fire of African freedom still burned in the veins of the slaves, there was in all leadership or attempted leadership but the one motive of revolt and revenge,—typified in the terrible Maroons, the Danish blacks, and Cato of Stono, and veiling all the Americas in fear of insurrection. The liberalizing tendencies of the latter half of the eighteenth century brought, along with kindlier relations between black and white, thoughts of ultimate adjustment and assimilation. Such aspiration was especially voiced in the earnest songs of Phyllis, in the martyrdom of Attucks, the fighting of Salem and Poor, the intellectual accomplishments of Banneker and Derham, and the political demands of the Cuffes.

Stern financial and social stress after the war cooled much of the previous humanitarian ardor. The disappointment and impatience of the Negroes at the persistence of slavery and serfdom voiced itself in two movements. The slaves in the South, aroused undoubtedly by vague rumors of the Haytian revolt, made three fierce attempts at insurrection,—in 1800 under Gabriel in Virginia, in 1822 under Vesey in Carolina, and in 1831 again in Virginia under the terrible Nat Turner. In the Free States, on the other hand, a new and curious attempt at self-development was made. In Philadelphia and New York color-prescription led to a withdrawal of Negro communicants from white churches and the formation of a peculiar socio-religious institution among the Negroes known as the African Church,—an organization still living and controlling in its various branches over a million of men.

Walker's wild appeal against the trend of the times showed how the world was changing after the coming of the cotton-gin. By 1830 slavery seemed hopelessly fastened on the South, and the slaves thoroughly cowed into submission. The free Negroes of the North, inspired by the mulatto immigrants from the West Indies, began to change the basis of their demands; they recognized the slavery of slaves, but insisted that they themselves were freemen, and sought assimilation and amalgamation with the nation on the same terms with other men. Thus, Forten and Purvis of Philadelphia, Shad of Wilmington, Du Bois of New Haven, Barbadoes of Boston, and others, strove singly and together as men, they said, not as slaves; as "people of color," not as "Negroes." The trend of the times, however, refused them recognition save in individual and exceptional cases, considered them as one with all the despised blacks, and they soon found themselves striving to keep even the rights they formerly had of voting and working and moving as freemen. Schemes of migration and colonization arose among them; but these they refused to entertain, and they eventually turned to the Abolition movement as a final refuge.

Here, led by Remond, Nell, Wells-Brown, and Douglass, a new period of self-assertion and self-development dawned. To be sure, ultimate freedom and assimilation was the ideal before the leaders, but the assertion of the manhood rights of the Negro by himself was the main reliance, and John Brown's raid was the extreme of its logic. After the war and emancipation, the great form of Frederick Douglass, the greatest of American Negro leaders, still led the host. Self-assertion, especially in political lines, was the main programme, and behind Douglass came Elliot, Bruce, and Langston, and the Reconstruction politicians, and, less conspicuous but of greater social significance, Alexander Crummell and Bishop Daniel Payne.

Then came the Revolution of 1876, the suppression of the Negro votes, the changing and shifting of ideals, and the seeking of new lights in the great night. Douglass, in his old age, still bravely stood for the ideals of his early manhood,—ultimate assimilation through self-assertion, and on no other terms. For a time Price arose as a new leader, destined, it seemed, not to give up, but to re-state the old ideals in a form less repugnant to the white South. But he passed away in his prime. Then came the new leader. Nearly all the former ones had become leaders by the silent suffrage of their fellows, had sought to lead their own people alone, and were usually, save Douglass, little known outside their race. But Booker T. Washington arose as essentially the leader not of one race but of two,—a compromiser between the South, the North, and the Negro. Naturally the Negroes resented, at first bitterly, signs of compromise which surrendered their civil and political rights, even though this was to be exchanged for larger chances of economic development. The rich and dominating North, however, was not only weary of the race problem, but was investing largely in Southern enterprises, and welcomed any method of peaceful coöperation. Thus, by national opinion, the Negroes began to recognize Mr. Washington's leadership; and the voice of criticism was hushed.

Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission; but adjustment at such a peculiar time as to make his programme unique. This is an age of unusual economic development, and Mr. Washington's programme naturally takes an economic cast, becoming a gospel of Work and Money to such an extent as apparently almost completely to overshadow the higher aims of life. Moreover, this is an age when the more advanced races are coming in closer contact with the less developed races, and the race-feeling is therefore intensified; and Mr. Washington's programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races. Again, in our own land, the reaction from the sentiment of war time has given impetus to race-prejudice against Negroes, and Mr. Washington withdraws many of the high demands of Negroes as men and American citizens. In other periods of intensified prejudice all the Negro's tendency to self-assertion has been called forth; at this period a policy of submission is advocated. In the history of nearly all other races and peoples the doctrine preached at such crises has been that manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and that a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing.

In answer to this, it has been claimed that the Negro can survive only through submission. Mr. Washington distinctly asks that black people give up, at least for the present, three things,—

First, political power,

Second, insistence on civil rights,

Third, higher education of Negro youth,—and concentrate all their energies on industrial education, and accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South. This policy has been courageously and insistently advocated for over fifteen years, and has been triumphant for perhaps ten years. As a result of this tender of the palm-branch, what has been the return? In these years there have occurred:

1. The disfranchisement of the Negro.

2. The legal creation of a distinct status of civil inferiority for the Negro.

3. The steady withdrawal of aid from institutions for the higher training of the Negro.

These movements are not, to be sure, direct results of Mr. Washington's teachings; but his propaganda has, without a shadow of doubt, helped their speedier accomplishment. The question then comes: Is it possible, and probable, that nine millions of men can make effective progress in economic lines if they are deprived of political rights, made a servile caste, and allowed only the most meagre chance for developing their exceptional men? If history and reason give any distinct answer to these questions, it is an emphatic No . And Mr. Washington thus faces the triple paradox of his career:

1. He is striving nobly to make Negro artisans business men and property-owners; but it is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for workingmen and property- owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage.

2. He insists on thrift and self-respect, but at the same time counsels a silent submission to civic inferiority such as is bound to sap the manhood of any race in the long run.

3. He advocates common-school and industrial training, and depreciates institutions of higher learning; but neither the Negro common-schools, nor Tuskegee itself, could remain open a day were it not for teachers trained in Negro colleges, or trained by their graduates.

This triple paradox in Mr. Washington's position is the object of criticism by two classes of colored Americans. One class is spiritually descended from Toussaint the Savior, through Gabriel, Vesey, and Turner, and they represent the attitude of revolt and revenge; they hate the white South blindly and distrust the white race generally, and so far as they agree on definite action, think that the Negro's only hope lies in emigration beyond the borders of the United States. And yet, by the irony of fate, nothing has more effectually made this programme seem hopeless than the recent course of the United States toward weaker and darker peoples in the West Indies, Hawaii, and the Philippines,—for where in the world may we go and be safe from lying and brute force?

The other class of Negroes who cannot agree with Mr. Washington has hitherto said little aloud. They deprecate the sight of scattered counsels, of internal disagreement; and especially they dislike making their just criticism of a useful and earnest man an excuse for a general discharge of venom from small-minded opponents. Nevertheless, the questions involved are so fundamental and serious that it is difficult to see how men like the Grimkes, Kelly Miller, J. W. E. Bowen, and other representatives of this group, can much longer be silent. Such men feel in conscience bound to ask of this nation three things:

1. The right to vote.

2. Civic equality.

3. The education of youth according to ability.

They acknowledge Mr. Washington's invaluable service in counselling patience and courtesy in such demands; they do not ask that ignorant black men vote when ignorant whites are debarred, or that any reasonable restrictions in the suffrage should not be applied; they know that the low social level of the mass of the race is responsible for much discrimination against it, but they also know, and the nation knows, that relentless color-prejudice is more often a cause than a result of the Negro's degradation; they seek the abatement of this relic of barbarism, and not its systematic encouragement and pampering by all agencies of social power from the Associated Press to the Church of Christ. They advocate, with Mr. Washington, a broad system of Negro common schools supplemented by thorough industrial training; but they are surprised that a man of Mr. Washington's insight cannot see that no such educational system ever has rested or can rest on any other basis than that of the well-equipped college and university, and they insist that there is a demand for a few such institutions throughout the South to train the best of the Negro youth as teachers, professional men, and leaders.

This group of men honor Mr. Washington for his attitude of conciliation toward the white South; they accept the "Atlanta Compromise" in its broadest interpretation; they recognize, with him, many signs of promise, many men of high purpose and fair judgment, in this section; they know that no easy task has been laid upon a region already tottering under heavy burdens. But, nevertheless, they insist that the way to truth and right lies in straightforward honesty, not in indiscriminate flattery; in praising those of the South who do well and criticizing uncompromisingly those who do ill; in taking advantage of the opportunities at hand and urging their fellows to do the same, but at the same time in remembering that only a firm adherence to their higher ideals and aspirations will ever keep those ideals within the realm of possibility. They do not expect that the free right to vote, to enjoy civic rights, and to be educated, will come in a moment; they do not expect to see the bias and prejudices of years disappear at the blast of a trumpet; but they are absolutely certain that the way for a people to gain their reasonable rights is not by voluntarily throwing them away and insisting that they do not want them; that the way for a people to gain respect is not by continually belittling and ridiculing themselves; that, on the contrary, Negroes must insist continually, in season and out of season, that voting is necessary to modern manhood, that color discrimination is barbarism, and that black boys need education as well as white boys.

In failing thus to state plainly and unequivocally the legitimate demands of their people, even at the cost of opposing an honored leader, the thinking classes of American Negroes would shirk a heavy responsibility,—a responsibility to themselves, a responsibility to the struggling masses, a responsibility to the darker races of men whose future depends so largely on this American experiment, but especially a responsibility to this nation,—this common Fatherland. It is wrong to encourage a man or a people in evil-doing; it is wrong to aid and abet a national crime simply because it is unpopular not to do so. The growing spirit of kindliness and reconciliation between the North and South after the frightful differences of a generation ago ought to be a source of deep congratulation to all, and especially to those whose mistreatment caused the war; but if that reconciliation is to be marked by the industrial slavery and civic death of those same black men, with permanent legislation into a position of inferiority, then those black men, if they are really men, are called upon by every consideration of patriotism and loyalty to oppose such a course by all civilized methods, even though such opposition involves disagreement with Mr. Booker T. Washington. We have no right to sit silently by while the inevitable seeds are sown for a harvest of disaster to our children, black and white.

First, it is the duty of black men to judge the South discriminatingly. The present generation of Southerners are not responsible for the past, and they should not be blindly hated or blamed for it. Furthermore, to no class is the indiscriminate endorsement of the recent course of the South toward Negroes more nauseating than to the best thought of the South. The South is not "solid"; it is a land in the ferment of social change, wherein forces of all kinds are fighting for supremacy; and to praise the ill the South is to-day perpetrating is just as wrong as to condemn the good. Discriminating and broad-minded criticism is what the South needs,—needs it for the sake of her own white sons and daughters, and for the insurance of robust, healthy mental and moral development.

To-day even the attitude of the Southern whites toward the blacks is not, as so many assume, in all cases the same; the ignorant Southerner hates the Negro, the workingmen fear his competition, the money-makers wish to use him as a laborer, some of the educated see a menace in his upward development, while others—usually the sons of the masters—wish to help him to rise. National opinion has enabled this last class to maintain the Negro common schools, and to protect the Negro partially in property, life, and limb. Through the pressure of the money-makers, the Negro is in danger of being reduced to semi-slavery, especially in the country districts; the workingmen, and those of the educated who fear the Negro, have united to disfranchise him, and some have urged his deportation; while the passions of the ignorant are easily aroused to lynch and abuse any black man. To praise this intricate whirl of thought and prejudice is nonsense; to inveigh indiscriminately against "the South" is unjust; but to use the same breath in praising Governor Aycock, exposing Senator Morgan, arguing with Mr. Thomas Nelson Page, and denouncing Senator Ben Tillman, is not only sane, but the imperative duty of thinking black men.

It would be unjust to Mr. Washington not to acknowledge that in several instances he has opposed movements in the South which were unjust to the Negro; he sent memorials to the Louisiana and Alabama constitutional conventions, he has spoken against lynching, and in other ways has openly or silently set his influence against sinister schemes and unfortunate happenings. Notwithstanding this, it is equally true to assert that on the whole the distinct impression left by Mr. Washington's propaganda is, first, that the South is justified in its present attitude toward the Negro because of the Negro's degradation; secondly, that the prime cause of the Negro's failure to rise more quickly is his wrong education in the past; and, thirdly, that his future rise depends primarily on his own efforts. Each of these propositions is a dangerous half-truth. The supplementary truths must never be lost sight of: first, slavery and race-prejudice are potent if not sufficient causes of the Negro's position; second, industrial and common-school training were necessarily slow in planting because they had to await the black teachers trained by higher institutions,—it being extremely doubtful if any essentially different development was possible, and certainly a Tuskegee was unthinkable before 1880; and, third, while it is a great truth to say that the Negro must strive and strive mightily to help himself, it is equally true that unless his striving be not simply seconded, but rather aroused and encouraged, by the initiative of the richer and wiser environing group, he cannot hope for great success.

In his failure to realize and impress this last point, Mr. Washington is especially to be criticised. His doctrine has tended to make the whites, North and South, shift the burden of the Negro problem to the Negro's shoulders and stand aside as critical and rather pessimistic spectators; when in fact the burden belongs to the nation, and the hands of none of us are clean if we bend not our energies to righting these great wrongs.

The South ought to be led, by candid and honest criticism, to assert her better self and do her full duty to the race she has cruelly wronged and is still wronging. The North—her co-partner in guilt—cannot salve her conscience by plastering it with gold. We cannot settle this problem by diplomacy and suaveness, by "policy" alone. If worse come to worst, can the moral fibre of this country survive the slow throttling and murder of nine millions of men?

The black men of America have a duty to perform, a duty stern and delicate,—a forward movement to oppose a part of the work of their greatest leader. So far as Mr. Washington preaches Thrift, Patience, and Industrial Training for the masses, we must hold up his hands and strive with him, rejoicing in his honors and glorying in the strength of this Joshua called of God and of man to lead the headless host. But so far as Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice, North or South, does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds,—so far as he, the South, or the Nation, does this,—we must unceasingly and firmly oppose them. By every civilized and peaceful method we must strive for the rights which the world accords to men, clinging unwaveringly to those great words which the sons of the Fathers would fain forget: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

Of the training of black men, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Check out our collection of primary source readers

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.

Booker T. Washington and His Ideas

Introduction, social darwinism and faith in the fairness of the free market, the impact on the place of blacks in society, the origin and credibility of washington’s ideas, the success of washington’s approach to black advancement.

Booker T. Washington was one of the most influential leaders of ethnic minorities in the United States of the nineteenth century. He was also a researcher who proposed a row of practical actions to resolve the issues of these population groups, mostly of economic nature (Tozer et al., 2020). Therefore, this activist’s suggestions were distinct from other proposals regarding the matter by the orientation of specific measures, which should be taken to improve the lives of African American citizens (Washington, 2018). Hence, this paper aims to consider his ideas related to the problems of Blacks, their origin and impact on their place in society, as well as the outcome of this leader’s activity.

The development of Washington’s thought had several directions, which represented his position regarding the methods of establishing a reasonable quality of life for all people. The first consideration was the concept of Social Darwinism he learned when attending Hampton, which applies to societal and economic aspects of human activity and means the survival of the most capable members of society (Tozer et al., 2020). However, it did not correlate with the circumstances of Blacks’ lives, and the political initiatives were not useful for ensuring their development. From Washington’s perspective, the principal area, which should be covered by the policy intended to help these people, was industrial education intended to provide them with opportunities for material prosperity (Washington, 2018). In this way, he emphasized the importance of economic security and vocational skills in contrast to politics.

His opinion was underpinned by the considerations of the fairness of the free market in business as a principal circumstance leading to African Americans’ future prosperity. Thus, Washington claimed that their acceptance by white people is possible only in the case if they are economical, not politically, equal (Tozer et al., 2020). This perspective allowed the leader to prove the importance for Blacks to work and acquire new skills instead of attempting to be more active in the political arena.

The perceptions of Washington regarding the predominant role of economic factors not only shaped his views but also significantly affected the intention of African Americans to find their place in society. Their influence was conditional upon the fact that representatives of this population group did not have any efficient means to improve their situation at the time (Washington, 2018). On the contrary, most Black leaders were trying to attract public attention to their problems without suggesting any practical ways to solve them and gain equality (Tozer et al., 2020). From this point of view, the economic considerations of Washington based on the concept of Social Darwinism and his belief in the fairness of the free market were transmitted to Blacks. They demonstrated the appropriate course of action leading to improvements in quality of life.

The ideas of Booker T. Washington originated from his personal experience, and this fact adds credibility to them. Being born as a slave and further emancipated, he faced the challenge of the need to take responsibility for the future since freedom implied the ability to provide for himself (Washington, 2018). Washington noticed that Blacks did not possess the skills allowing them to survive in the world of white men. In his opinion, this situation could be explained by the lack of understanding of economic processes and, therefore, participation in them (Tozer et al., 2020). Nevertheless, despite the apparent logic of such thinking, his judgment seems to be naïve from the psychological perspective. The active participation of African Americans in business affairs resembles a utopia since the white population was unwilling to deal with them.

The approach of Booker T. Washington to Black advancement was quite successful in terms of initiating their economic involvement. However, his goals underlying the foundation of the National Negro Business League were not fully met (Washington, 2018). Thus, for example, the initiative to build a network of African American entrepreneurs was hindered by the civil rights movement, which came to the fore (Tozer et al., 2020). In this way, the attention of representatives of this ethnic group was focused on the actions for establishing equality rather than material prosperity as an indirect method to achieve this objective (Washington, 2018). Nevertheless, the economic movement started with the implementation of Washington’s ideas and marked the beginning of Black’s progress in this area.

To summarize, the political thought of Booker T. Washington based on the concept of Social Darwinism and the free market contributing to the improvement of the quality of life of African Americans had positive results. It allowed promoting their economic rights as a principal condition of future equality with the white population and, therefore, finding their place in society. The origin of Washington’s ideas related to his personal experience and struggles adds to the reasonability of his initiatives regarding the Blacks’ participation in business. Even though his perceptions were naïve from the perspective of all citizens’ acceptance of their intervention in this field, it can be concluded that they still significantly affected their wellbeing. Thus, Black advancement was a successful endeavor in terms of promoting the rights of African Americans throughout the country.

Tozer, S., Senese, G., & Violas, P. (2020). School and society: Historical and contemporary perspectives (8 th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Washington, B. T. (2018). The future of the American Negro. Outlook Verlag GmbH.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, March 9). Booker T. Washington and His Ideas. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/

"Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." StudyCorgi , 9 Mar. 2022, studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Booker T. Washington and His Ideas'. 9 March.

1. StudyCorgi . "Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." March 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." March 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Booker T. Washington and His Ideas." March 9, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/booker-t-washington-and-his-ideas/.

This paper, “Booker T. Washington and His Ideas”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: May 23, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

The Booker T. Washington Papers Digital Edition

Born into slavery, Booker T. Washington became the leading voice for Black Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. Author, pioneer in higher education, adviser to presidents and business leaders, and a pillar in the emerging Black elite and middle class, Washington helped conceive a future for an educated, prosperous Black society in the wake of emancipation and Reconstruction.

The son of an enslaved Virginia woman, Washington identified education as the pathway out of poverty, a necessity for his voracious intellect, and the focus of his professional life. He served as the first president of what is now Tuskegee University, to this day one of the premier historically Black universities in America. As president he forged relationships with the most powerful philanthropists of the day, including Carnegie and Rockefeller, establishing a network of donors that reflected a belief in and talent for working with the white establishment. Washington’s landmark Atlanta Exposition Speech in 1895 called for an African American investment in industrial education and accumulation of wealth as a way of integrating Blacks into society at large. This position was not uncontroversial—passionate activists such as NAACP cofounder W. E. B. Du Bois criticized it as being too conservative—and the surrounding debates are foundational to the most vital discussions in Black discourse: how can Black Americans best advance themselves, and can true equality and equity be achieved in the face of white oppression and the legacies of segregationist public policy?

This digital edition is based on the landmark fourteen-volume print series of Washington’s papers, one of the great documentary editions in American scholarship—“a major enterprise in Black historiography” (Times Literary Supplement). This online archive collects the complete contents of the print edition; it is fully searchable and is interoperable with other titles in Rotunda’s American History Collection.

Others in American Century Collection :

Back to all rotunda.

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

- General Inquiries

- Staff Directory

National Historical Publications & Records Commission

Booker T. Washington Papers

Booker T. Washington by Frances B. Johnston, c. 1895, Courtesy Library of Congress

University of Maryland

University of Illinois Press

Additional information at http://press.illinois.edu/books/catalog/54exz5ew9780252002427.html

Booker Taliaferro Washington (1856 –1915) was an African-American educator, author, orator, and advisor to presidents of the United States and became the leading voice of the formerly enslaved who were newly oppressed by the discriminatory laws enacted in the post reconstruction Southern states in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1890 and 1915 Washington was the dominant leader in the US African-American community. In 1895 his Atlanta Compromise called for avoiding confrontation over segregation and instead putting more reliance on long-term educational and economic advancement in the black community, with a goal of building the community's economic strength and pride by a focus on self-help and schooling. This collection is a selective edition of his writings, addresses, and correspondence.

Complete in 14 volumes, including a cumulative index volume

Previous Record | Next Record | Return to Index

The Booker T. Washington Papers

Essay title: Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington was the first African American whose likeness appeared on a United States postage stamp. Washington also was thus honored a quarter century after his death. In 1946 he also became the first black with his image on a coin, a 50-cent piece. The Tuskegee Institute, which Washington started at the age of 25, was the where the 10-cent stamps first were available. The educator's monument on its campus shows him lifting a symbolic veil from the head of a freed slave.

Booker Taliaferro Washington was born a slave on April 5, 1856, in Franklin County, Va. His mother, Jane Burroughs, was a plantation cook. His father was an unknown white man. As a child, Booker swept yards and brought water to slaves working in the fields. Freed after the American Civil War, he went with his mother to Malden, W. Va., to join Washington Ferguson, whom she had married during the war.

At about age 16 Booker set out for Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, which had been established by the chief of the Freedmen's Bureau to educate former slaves. He walked much of the way, working to earn the fare to complete the long, dusty journey to Virginia. For his admission test he repeatedly swept and dusted a classroom, and he was able to earn his board by working as a janitor. After graduation three years later he taught in Malden and at Hampton.

A former slave who had become a successful farmer, and a white politician in search of the Negro vote in Macon County obtained financial support for a training school for blacks in Tuskegee, Ala. When the board of commissioners asked the head of Hampton to send a principal for their new school, they had expected the principal to be white. Instead Washington arrived in June 1881. He began classes in July with 30 students in a shanty donated by a black church. Later he borrowed money to buy an abandoned plantation nearby and moved the school there. By the time of his death in Tuskegee in 1915 the institute had some 1,500 students, more than 100 well-equipped buildings, and a large faculty.

Washington believed that blacks could promote their constitutional rights by impressing Southern whites with their economic and moral progress. He wanted them to forget about political power and concentrate on their farming skills and learning industrial trades. Brickmaking, mattress making, and wagon building were among the courses Tuskegee offered. Its all-black faculty included the famous agricultural scientist George Washington Carver.

The open controversy over acceptable black leadership dated from 1895, when Washington was invited to address a white audience at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Ga. While emphasizing the importance of economic advancement to blacks, he repeatedly used the paraphrase, "Cast down your bucket where you are." Some blacks were incensed by his comment, "The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly." Others feared that the enemies of equal rights were encouraged by his promise, "In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress."

From 1895 until his death in 1915, Booker T. Washington, an ex-slave who had built Tuskegee Institute in Alabama into a major center of industrial training for black youths, was the nation's dominant black leader. In a speech made in Atlanta, in 1895, Washington called on both blacks and whites to "cast down your bucket where you are." He urged whites to employ the masses of black laborers. He called on blacks to cease agitating for political and social rights and to concentrate instead on working to improve their economic conditions. Washington felt that excessive stress had been placed on liberal arts education for blacks. He believed that their need to earn a living called instead for training in crafts and trades. In an effort to spur the growth of black business enterprise, Washington also organized the National Negro Business League in 1900. But black businessmen were handicapped by insufficient capital and by the competition of white-owned big businesses.

Washington was highly successful in winning influential white support. He became the most powerful black man in the nation's history. But his program of vocational training did not meet the changing needs of industry,

Booker T. Washington Papers Volume 1

About the book, about the author, also by this author.

Book Details

Related titles.

Stay Connected

How is Booker T Washington Related to Education

This essay about Booker T. Washington explores his profound impact on American education, emphasizing his rise from slavery to a key educational leader. It highlights his advocacy for vocational training and economic self-reliance as means to empower the African American community. Washington’s founding of the Tuskegee Institute and his broader influence on civil rights are discussed, alongside criticisms from peers like W.E.B. Du Bois. The essay concludes by affirming Washington’s enduring legacy as a catalyst for educational and social advancement.

How it works

Booker T. Washington’s influence on education forms a complex pattern, marked by his resilience, determination, and a steadfast belief in education’s power to transform. Born a slave in 1856, Washington rose from the depths of servitude to become a prominent figure in African American education, exemplifying triumph over adversity.

At the core of his educational philosophy was the conviction that knowledge could liberate and propel individuals forward, mitigating the shackles of oppression. He emphasized vocational education and economic independence as critical tools for uplifting the African American community.

Washington’s key contribution was the establishment of the Tuskegee Institute in 1881. Under his leadership, Tuskegee grew from a humble institution into a center of industrial and vocational training. There, students learned essential skills in various trades, empowering them to shape their futures and achieve economic stability.

Beyond Tuskegee, Washington’s impact reverberated nationwide. He promoted the virtues of self-reliance and personal improvement, fostering a sense of pride and resilience among African Americans facing systemic discrimination. His speeches and persistent advocacy championed education as a source of hope and progress.

Nevertheless, Washington’s strategies drew criticism from contemporaries like W.E.B. Du Bois, who opposed his seemingly accommodating stance on civil rights in favor of economic advancement. This disagreement sparked a significant discourse on the direction of African American advancement.

Despite these critiques, Washington maintained that education was essential for progress. His efforts reached into all corners of African American society, from urban centers to rural areas. Through his founding of the National Negro Business League and involvement in early civil rights movements, Washington made a lasting imprint on the struggle for equality.

Reflecting on Washington’s legacy, we recognize the enduring power of education to elevate and bridge divides. His life remains a source of inspiration, demonstrating the indomitable nature of the human spirit and the vast potential within those who aspire to rise. Washington’s contributions continue to light the way forward, underscoring his pivotal role in shaping the educational and social landscapes.

Cite this page

How Is Booker T Washington Related To Education. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/how-is-booker-t-washington-related-to-education/

"How Is Booker T Washington Related To Education." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/how-is-booker-t-washington-related-to-education/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). How Is Booker T Washington Related To Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/how-is-booker-t-washington-related-to-education/ [Accessed: 29 Apr. 2024]

"How Is Booker T Washington Related To Education." PapersOwl.com, Apr 29, 2024. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/how-is-booker-t-washington-related-to-education/

"How Is Booker T Washington Related To Education," PapersOwl.com , 29-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/how-is-booker-t-washington-related-to-education/. [Accessed: 29-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). How Is Booker T Washington Related To Education . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/how-is-booker-t-washington-related-to-education/ [Accessed: 29-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Why We Still Use Postage Stamps

The enduring necessity (and importance) of a nearly 200-year-old technology

In a decidedly digital age, the modest postage stamp seems to be slowly vanishing from daily life—no longer ubiquitous in wallets or pocketbooks, useful but maybe not essential.

They’re so overlooked that the comedian Nate Bargatze has an entire bit about how stamps make him “nervous.” “I don’t know how many you’re supposed to put on [a letter],” he says. “And they change the price of stamps, and that’s not in the news, you know? You don’t find that out on Twitter. You have to find out from old people. They’re the only people that know.” (As someone in the news, I am duty bound to report that stamps’ price increased from $0.66 to $0.68 on January 21.)

But stamps aren’t yet entirely anachronistic. Yes, the volume of first-class mail has been on the decline, but the U.S. Postal Service still sells about 12.5 billion stamps annually. Some of this is a matter of taste. “There are certain things where physical mail is still seen as the socially correct way to do things,” says Daniel Piazza, the chief curator of philately at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, pointing to mailing wedding invitations, birthday notes, and holiday cards.

But stamps serve a purpose that is not merely functional. If you look back far enough, they also tell a story about national identity, and the technological and cultural trajectory of America. Stamps “are both miniature art works and pieces of government propaganda,” Dennis Altman wrote in his 1991 book, Paper Ambassadors: The Politics of Stamps . “They can be used to promote sovereignty, celebrate achievement, define national, racial, religious, or linguistic identity, portray messages or exhort certain behaviour.”

Richard Morel, the curator of the British Library’s Philatelic Collection, put it to me more succinctly: “Stamps democratize our history and culture.” In short, the history of U.S. stamps tells a story of America.

The postage stamp as we know it today is a relatively young technology. Prior to the mid-1800s, “most letters were sent collect, so postage was paid by the recipient of the letter rather than by the sender,” Piazza told me. This turned out to be a very bad business model for the Postal Service. First, it required people to go to their post office to see whether they had mail. In fact, postmasters paid to run ads in local papers listing who had letters to collect so those people would retrieve them. (One true constant across time seems to be that people consider going to the post office a chore.) Then, if there was a letter for someone and they did pick it up, the receiver had to pay the postage, which they sometimes refused to do, given its expense. “So it’s a very cumbersome, sort of expensive system” for both the Postal Service and the receivers of mail, Piazza said.

Read: One Thousand Stamps, All Different (1939)

Until a breakthrough in 1840. The U.K. issued the Penny Black, the world’s first prepaid, adhesive stamp. With this stamp, people could send a half-ounce letter for a flat, prepaid rate of one penny. The Penny Black featured the face of Queen Victoria, and, in a sign of the times, some people believed that “licking the back of the queen’s head was undignified, if not potentially treasonous,” Altman wrote in his book. On a recent visit to the British Library, I was able to see the last remaining press of the type that printed the Penny Black. Displayed on the library’s upper-ground floor, the machine—which was smaller than I had imagined, given its function—looked as delicate as an antiquity of the Industrial Revolution can, with its large spindle, rope pulleys, and iron weights.

This British innovation in stamp production set the path for other countries to follow. In the 1840s and ’50s, several other nations developed their own postage stamps. The U.S. issued its first ones on July 1, 1847: a five-cent stamp featuring Benjamin Franklin, the country’s first postmaster general, and a 10-cent stamp featuring George Washington. (Washington, distinguished in so many ways, also has the distinction of having more appearances on U.S. stamps than anyone else.)

The start of stamps in the U.S. was an unheralded affair. A postmaster in Maine mailed a letter—without a stamp, postage due—to the postmaster general to inquire whether the stamps his office had received were “genuine,” according to Smithsonian Magazine . But by 1856, all mail required federal, prepaid postage stamps, and we largely entered the state of postage stamps as we know them today. Or, as Morel put it, their invention “triggered our information revolution.”

Stamp design, however, took a little longer to develop. For decades, American stamps followed the aesthetics of coin-face design, that is, profile drawings of heads of state. In our case, primarily dead presidents: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson. The U.S. didn’t begin issuing commemorative stamps until 1893, timed to the World’s Fair in Chicago, with a series of 16 stamps celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to the New World. Included in the series was a depiction of Queen Isabella of Spain, making her the first woman featured on a U.S. stamp. (The first American woman on a stamp was Martha Washington, in 1902.)

In the 130 years since that first commemorative stamp, hundreds and hundreds more designs have been issued. U.S. postage stamps have celebrated momentous events, such as the 1932 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid New York, home of the first U.S. Winter Olympics Games, and the moon landing, in 1969. There have been many stamp firsts: the first Hispanic American (Admiral David Farragut, 1903), the first Native American (Pocahontas, 1907), the first African American (Booker T. Washington, 1940). Some stamps impart social messages: Prevent Drug Abuse (1971) or Alcoholism: You Can Beat It (1981). They’ve even been used to fund causes. The Breast Cancer Research semipostal has sold more than 1 billion stamps since it was first issued, in 1998, and has raised millions of dollars for the cause.

“If you compare some of the American stamp designs … to other countries’, they’re incredibly progressive much earlier on,” Morel said. There’s the Black Heritage Series, which began in 1978 with an image of Harriet Tubman and still runs today with annual new releases. Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan were commemorated on a stamp in 1980. Even designs that might now be seen as dated or insensitive were bold in their own time. In 1969, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp that featured an image of a young child gradually emerging out of a wheelchair. The language on the stamp reads, Hope for the crippled . “The language is now problematic,” Morel said, “but it’s the intent that underlies the stamp design, which is actually a positive one.”

These design decisions are not made lightly. In 1957, the Postal Service created the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee, which consists of a group of people from across disciplines who consider stamp recommendations from the public. Anyone can suggest any subject to the council, which will weigh the recommendation so long as it meets its healthy list of criteria —for example, the design should honor a subject or a figure that made a significant contribution to American life, and the commemorated can’t be a living person.

It’s a deliberative process that can take several years—and for good reason. Nearly any stamp design is certain to irritate someone. In the early 1990s, when the Postal Service announced that it would be releasing a stamp featuring Elvis, some Americans were scandalized. They couldn’t fathom the idea of honoring someone who had addiction issues and was once considered too sexy for broadcast television. “I was appalled to see that a picture of Elvis Presley is being considered for a postage stamp,” one person wrote in a letter to the editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1992. “The picture on a postage stamp should be someone or something of historical significance or an individual who has made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of the human race … If Presley appears on a stamp, the postmaster general should be fired immediately.” The Postal Service won the day; the Elvis stamp is widely considered the most popular commemorative stamp in U.S. history. The decision to put Bugs Bunny on a stamp was also met with mild indignation. “That one probably didn’t go over as well with the serious stamp collectors,” says Jay Bigalke, the editor in chief of Linn’s Stamp News . People used it as an excuse to “write to the Postal Service and say, ‘If you can issue a stamp for Bugs Bunny, you can issue a stamp for fill-in-the-blank.’”

A reason these design choices are so freighted is that they have broad, international reach. “Trivial as they may seem, [stamps] are objects that are extremely dispersed both domestically and abroad, and which allow governments to propagate widely the official culture of a given state,” Altman wrote. Said another way, stamps let officials tell the story they want to tell. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a stamp collector himself, “nosed his way into stamp design, even sketching them out on a napkin and passing it along to the postmaster general at the time,” Bigalke told me. After Roosevelt signed the National Industrial Recovery Act, he asked for a stamp promoting the law to be issued. “He just recognized the importance of the postage stamp and conveying a message,” Bigalke said.

Other countries use their stamps to tell stories too, and sometimes those stories are deeply influenced by the United States. A number of African countries have released stamps featuring Martin Luther King Jr., for example, a testament to King’s international importance and popularity. The Apollo 11 mission has been featured on more than 50 stamps in other countries. A stamp issued by Iran in 1984 featured Malcolm X. American pop culture has also infiltrated international postage stamps. In the Caribbean, St. Vincent and the Grenadines has featured both Elvis and Michael Jackson on its stamps. (Jackson has not been featured on an American stamp.)

Read: Stamps for Me (1943)

Stamps are also used for more expressly political or propagandist purposes. In 1969, North Korea issued a stamp called “International Conference of Journalists Against US Imperialism,” showing several pens attacking President Richard Nixon. “The very fact that [North Korea] uses stamps as a medium to attack America is, again, proof [of] the value of stamps,” Morel said. “Because if there was no value, why bother?”

More recently, Ukraine used its stamp program as a sort of hearts-and-minds campaign. “When the invasion and the war broke out, they issued a postage stamp showing a soldier flipping off the battleship” off of Snake Island, Bigalke said. Ukraine has “been using stamps as a rallying cry in the country in a much more powerful way than any other country really has with their postage stamps,” he told me. “A lot of people have bought the stamps to help support Ukraine.”