Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

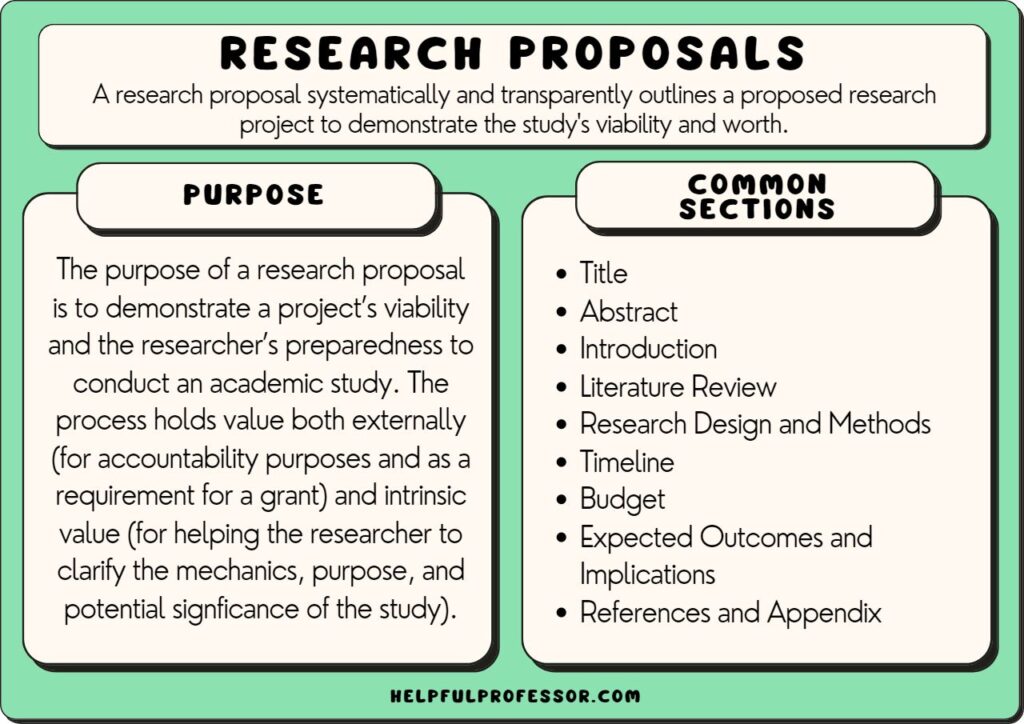

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How To Write A Research Proposal

A Straightforward How-To Guide (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2019 (Updated April 2023)

Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive , attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

– Understand exactly what a research proposal is – Ask yourself these 4 questions

The 5 essential ingredients:

- The title/topic

- The introduction chapter

- The scope/delimitations

- Preliminary literature review

- Design/ methodology

- Practical considerations and risks

What Is A Research Proposal?

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question) , worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here .

How do I know I’m ready?

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions . If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic .

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

- WHAT is my main research question? (the topic)

- WHO cares and why is this important? (the justification)

- WHAT data would I need to answer this question, and how will I analyse it? (the research design)

- HOW will I manage the completion of this research, within the given timelines? (project and risk management)

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic .

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

The 5 Essential Ingredients

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Ingredient #1 – Topic/Title Header

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title . Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

Need a helping hand?

Ingredient #2 – Introduction

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

- An overview of the broad area you’ll be researching – introduce the reader to key concepts and language

- An explanation of the specific (narrower) area you’ll be focusing, and why you’ll be focusing there

- Your research aims and objectives

- Your research question (s) and sub-questions (if applicable)

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Ingredient #3 – Scope

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations . In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

Ingredient #4 – Literature Review

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

- Demonstrate that you’ve done your reading and are familiar with the current state of the research in your topic area.

- Show that there’s a clear gap for your specific research – i.e., show that your topic is sufficiently unique and will add value to the existing research.

- Show how the existing research has shaped your thinking regarding research design . For example, you might use scales or questionnaires from previous studies.

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction . Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Ingredient #5 – Research Methodology

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions :

- How will you design your research? I.e., what research methodology will you adopt, what will your sample be, how will you collect data, etc.

- Why have you chosen this design? I.e., why does this approach suit your specific research aims, objectives and questions?

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part , because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

- Your intended research philosophy (e.g., positivism, interpretivism or pragmatism )

- What methodological approach you’ll be taking (e.g., qualitative , quantitative or mixed )

- The details of your sample (e.g., sample size, who they are, who they represent, etc.)

- What data you plan to collect (i.e. data about what, in what form?)

- How you plan to collect it (e.g., surveys , interviews , focus groups, etc.)

- How you plan to analyse it (e.g., regression analysis, thematic analysis , etc.)

- Ethical adherence (i.e., does this research satisfy all ethical requirements of your institution, or does it need further approval?)

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “ research onion ” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here .

Don’t forget the practicalities…

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

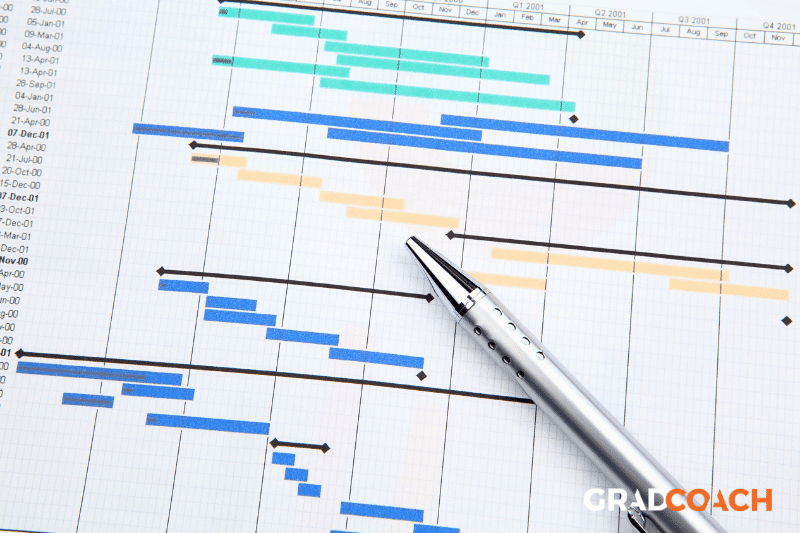

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management . In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

- What are the timelines for each phase of your project?

- Are the time allocations reasonable?

- What happens if something takes longer than anticipated (risk management)?

- What happens if you don’t get the response rate you expect?

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

Final Touches: Read And Simplify

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

Let’s Recap: Research Proposal 101

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- The purpose of the research proposal is to convince – therefore, you need to make a clear, concise argument of why your research is both worth doing and doable.

- Make sure you can ask the critical what, who, and how questions of your research before you put pen to paper.

- Title – provides the first taste of your research, in broad terms

- Introduction – explains what you’ll be researching in more detail

- Scope – explains the boundaries of your research

- Literature review – explains how your research fits into the existing research and why it’s unique and valuable

- Research methodology – explains and justifies how you will carry out your own research

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

29 Comments

Thank you so much for the valuable insight that you have given, especially on the research proposal. That is what I have managed to cover. I still need to go back to the other parts as I got disturbed while still listening to Derek’s audio on you-tube. I am inspired. I will definitely continue with Grad-coach guidance on You-tube.

Thanks for the kind words :). All the best with your proposal.

First of all, thanks a lot for making such a wonderful presentation. The video was really useful and gave me a very clear insight of how a research proposal has to be written. I shall try implementing these ideas in my RP.

Once again, I thank you for this content.

I found reading your outline on writing research proposal very beneficial. I wish there was a way of submitting my draft proposal to you guys for critiquing before I submit to the institution.

Hi Bonginkosi

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, we do provide a review service. The best starting point is to have a chat with one of our coaches here: https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Hello team GRADCOACH, may God bless you so much. I was totally green in research. Am so happy for your free superb tutorials and resources. Once again thank you so much Derek and his team.

You’re welcome, Erick. Good luck with your research proposal 🙂

thank you for the information. its precise and on point.

Really a remarkable piece of writing and great source of guidance for the researchers. GOD BLESS YOU for your guidance. Regards

Thanks so much for your guidance. It is easy and comprehensive the way you explain the steps for a winning research proposal.

Thank you guys so much for the rich post. I enjoyed and learn from every word in it. My problem now is how to get into your platform wherein I can always seek help on things related to my research work ? Secondly, I wish to find out if there is a way I can send my tentative proposal to you guys for examination before I take to my supervisor Once again thanks very much for the insights

Thanks for your kind words, Desire.

If you are based in a country where Grad Coach’s paid services are available, you can book a consultation by clicking the “Book” button in the top right.

Best of luck with your studies.

May God bless you team for the wonderful work you are doing,

If I have a topic, Can I submit it to you so that you can draft a proposal for me?? As I am expecting to go for masters degree in the near future.

Thanks for your comment. We definitely cannot draft a proposal for you, as that would constitute academic misconduct. The proposal needs to be your own work. We can coach you through the process, but it needs to be your own work and your own writing.

Best of luck with your research!

I found a lot of many essential concepts from your material. it is real a road map to write a research proposal. so thanks a lot. If there is any update material on your hand on MBA please forward to me.

GradCoach is a professional website that presents support and helps for MBA student like me through the useful online information on the page and with my 1-on-1 online coaching with the amazing and professional PhD Kerryen.

Thank you Kerryen so much for the support and help 🙂

I really recommend dealing with such a reliable services provider like Gradcoah and a coach like Kerryen.

Hi, Am happy for your service and effort to help students and researchers, Please, i have been given an assignment on research for strategic development, the task one is to formulate a research proposal to support the strategic development of a business area, my issue here is how to go about it, especially the topic or title and introduction. Please, i would like to know if you could help me and how much is the charge.

This content is practical, valuable, and just great!

Thank you very much!

Hi Derek, Thank you for the valuable presentation. It is very helpful especially for beginners like me. I am just starting my PhD.

This is quite instructive and research proposal made simple. Can I have a research proposal template?

Great! Thanks for rescuing me, because I had no former knowledge in this topic. But with this piece of information, I am now secured. Thank you once more.

I enjoyed listening to your video on how to write a proposal. I think I will be able to write a winning proposal with your advice. I wish you were to be my supervisor.

Dear Derek Jansen,

Thank you for your great content. I couldn’t learn these topics in MBA, but now I learned from GradCoach. Really appreciate your efforts….

From Afghanistan!

I have got very essential inputs for startup of my dissertation proposal. Well organized properly communicated with video presentation. Thank you for the presentation.

Wow, this is absolutely amazing guys. Thank you so much for the fruitful presentation, you’ve made my research much easier.

this helps me a lot. thank you all so much for impacting in us. may god richly bless you all

How I wish I’d learn about Grad Coach earlier. I’ve been stumbling around writing and rewriting! Now I have concise clear directions on how to put this thing together. Thank you!

Fantastic!! Thank You for this very concise yet comprehensive guidance.

Even if I am poor in English I would like to thank you very much.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write a Research Proposal: Template, Format, Tips

Learn how to write a research proposal that makes you stand out from the crowd, get the funding you need, and gain entry into your dream academic institution.

John McTale

14 minute read

You’ve put a lot of thought into that research project. You know it’s importan. The problem? Nobody else does. And no one is willing to fund it. Yet.

Research proposals are nerve-racking, notoriously difficult to write, and for good reason - they have a major impact on your academic career.

The best institutions and labs have thousands of talented researchers fighting to get in. And their most powerful weapon to get ahead of the pack is their research proposal.

So, how do you write a proposal that helps you outperform other applicants?

This guide will help you write stress-free research proposals that land the funding you deserve and launch your academic career .

What is a research proposal?

A research proposal is a formal academic document that outlines your research project and requests support for that project: either by funding or agreeing to supervise your research.

The main objective of a research proposal is to explain what you’re planning to research and why it’s worth researching. Research proposals are most commonly used in academia or across non-academic scientific organizations. Of course, no two research proposals are identical—in fact, those can vary greatly depending on the level of study you’re at, your field, or the exact nature of your project.

Still, there are some general requirements that all great proposals have to meet and must-have sections to include. This article will focus particularly on writing research proposals for academic grants at postgraduate level or PhD applications. However, even if you’re writing a thesis or a dissertation proposal, most of the same rules apply—it’s just that your proposal might not have to be as detailed and comprehensive. Speaking of which...

How long should a research proposal be?

Most research proposals in humanities and social sciences are between 10 and 25 pages long. Technical or scientific proposals might require you to include detailed specifications and more supporting documentation and can therefore be significantly longer. That said, each institution might have its own guidelines and requirements for research proposals and those often include the word count range. If that’s the case, you obviously have to play by the rules.

Try Storydoc for research proposals

If you want to add some flair to your research proposal and immediately stand out from hundreds of other, identically-looking documents, take our interactive proposal maker for a spin and create a visually stunning summary of your proposal. Storydoc is 100% free to use for verified .edu email addresses.

Alright, we covered the theoretical part. Time for some practical knowledge!

Here’s how to write a research proposal:

1. write an introduction to present the subject of your research.

“Wow, I can’t wait to see the outcome of this study!” This is the kind of response you want your research proposal introduction to receive. How to make that happen? Outline your research proposal intro around these four key issues:

- What is the research problem?

- Who is this problem relevant to (general society, fellow researchers, specialized professionals, etc.)?

- What is currently known about the problem and what key pieces are missing from the current state of knowledge?

- Why should anyone care about the potential outcomes?

The easiest way to write a captivating intro to a research proposal is to follow a four-paragraph format, where each paragraph addresses one of these questions. Let’s see a practical example. (Yes, I made it up, but it works as a convenient point of reference.)

Sample outline for a research proposal introduction

The problem Investigating the impact of remote work on new joiners to previously in-house teams. Who it’s relevant to Human resources professionals, workspace psychologists, working population, business management specialists and scholars. What’s currently known There is existing research about the impact of remote work on team morale and productivity, but no research has been centered around people joining fully-remote teams that had previously worked in-house and the implications of such a situation for new employees' mental health and sense of belonging. Why should anyone care? In the era of COVID, many offices have switched to remote-only work yet they’re still hiring new employees. The findings of this study might suggest a need to change onboarding practices and HR management techniques in order to aid employee satisfaction which, in turn, can help improve work performance, NPS scores and overall business results.

2. Explain the Context and Background

Whether or not you’ll need this section depends on how detailed your proposal is. If a research problem at hand is particularly complicated or advanced, it’s usually best to add this section. It will usually be entitled “Background and Significance,” or “Rationale.” For shorter proposals, most of the actual background will have been already included in the introduction. How to write the “Background” section of a research proposal?

- Describe the broader area of research that your project fits into.

- Focus on the gaps in existing studies and explain the need to fill these gaps. That said…

- Show how your research will build upon existing knowledge.

- Explain your hypothesis and the rationale behind it.

- Establish the limits of your study (in other words, explain what the research is not about).

- Finally, reiterate why your research is important and what benefits it can reap. In other words, provide the answer to the dreaded “So what?” question.

If your research project is complex and highly technical, describing the background in a separate section is particularly helpful: this way, you can make your introduction follow a free-flowing, “sexy” narrative, and let the “Background” part do the heavy lifting. That said— Don’t make this part too detailed either. Assume you’re dealing with a very busy reader who won’t have the time to get into your methodology and timeline but still wants some hard evidence behind the relevance of your project.

3. Provide a Detailed Literature Review

Arguably, the most important (and, yes, you guessed it, the most difficult) part of the whole document— One where you have to prove that you know *all* there is to know about the topic of interest and that your research will help advance the whole field of study. The Literature Review section is, in essence, a mini-dissertation. It has to follow a logical progression and put forward the argument for your study in relation to existing research: describe and summarize what has already been discussed and demonstrate that your research goes beyond that. In the digital era of easy access to information , it might be difficult to discuss all of the existing research on your subject in the Literature Review so be critical about what studies or papers you choose to include.

But there’s a handy set of rules to help you pick the right ones—the gold standard for academic Literature Review. It’s called “ the five Cs ” and refers to the following practices:

- Cite directly from the sources to avoid digressions and drifting away from the actual literature.

- Compare different theories or arguments (in arts and humanities), methodologies and findings (in sciences and tech).

- Contrast the approaches discussed above: highlight the main differences and areas of disagreement among scholars in the field.

- Critique the research of the past. Don’t shy away from pointing out inaccuracies, mutually exclusive findings, or controversies. At the same time, give credit where it’s due. Identify the findings you find most convincing, reliable, or accurate.

- Connect the whole of the literature reviewed to your own project. Are you basing your assumptions on any previous findings? Is your goal to confront, challenge, or even debunk certain pieces of research? Either way, you need to prove that your study will be intertwined with existing ones, not floating in an academic void.

How to structure your Literature Review?

- The easiest and most reader-friendly way to format the Literature Review section is to devote each paragraph to a separate piece of literature.

- For scientific projects, it’s best to go from the more general to the more specific studies.

- For projects in arts and humanities, a historical (or chronological) progression is the most commonly-used method as it helps develop an easy-to-follow narrative.

The hard part? DONE. (No, it really is). All of what comes next boils down to technicalities and formal requirements. If they’re sold on your vision by now, you just need to show how you’re planning to achieve what you set out to do.

4. List Your Key Aims and Objectives

This section can be called “Research Questions,” or just “Aims and Objectives.” Compared to the previous ones, it should be very succinct and to-the-point. Whether you need to write about your aims and objectives or formulate those as research questions usually depends on the formal requirements of the institution to which you’re applying. The key aspect of getting this part right is distinguishing between the three: an aim, an objective, and a research question. Here’s how:

- Aims describe what you want to achieve. An aim is usually stated in a broad term.

- Objectives are the specific, measurable outputs you need to produce in order to achieve your aim. There are usually multiple objectives associated with a single aim.

- Questions are a slightly more specific way to formulate your objectives—in essence, very similar in meaning, just slightly different in format.

Again, here’s a practical example. And again, it’s simplified and not based on actual research, just here to let you better understand the disambiguation.

Sample research aims and objectives for a research proposal

Research Aim

To understand the importance of the quality of food in school canteens on the nutritional health of children aged 6–10. Objectives:

- Investigate the weekly menus across 28 school canteens in New Jersey with a focus on key nutritional ingredients and portion sizes.

- Conduct desk-research of state policies regulating nutrition in primary schools.

- Interview the parents of children participating in the study about their children’s nutritional habits outside of school.

- Evaluate the key health-related metrics in children participating in the study.

As I mentioned, if such are the formal requirements, your objectives can easily be translated into research questions. For instance: “Conduct desk-research of state policies regulating nutrition in primary schools.” Becomes: “What state-wide policies regulating nutrition in primary schools are there in place in the state of New Jersey?”

Remember the five Cs of literature review? When it comes to your research objectives and questions, there’s another handy acronym to serve as a sanity check for you: SMART . It stands for:

- Specific: is the objective well-defined and can be achieved with a singular action?

- Measurable: will you end up with quantified, verifiable data?

- Achievable: considering your resources and capacity, is it realistic for you to reach your objective?

- Relevant: does this objective actually contribute to your research aim?

- Timebound: do you have enough time to complete this objective, in relation to the overall timeline of your project?

5. Outline the Research Methods and Design

The grant decision makers already know what you’re trying to achieve and have a general idea about how you’re planning to achieve that. This section should prove to them that you’re well equipped (both in terms of your skills and resources) to conduct the research. The main goal is to convince the reader that your methods are adequate and appropriate for the specific topic. Any idea why “specific” is in bold? Well, this is one of those parts of a research proposal that differs the most across different documents. There’s an ideal methodology for any particular academic project and no two kinds of research design are the same. Make sure your methodology matches all of your desired outcomes.

Some usual components of the Research Methods section include:

Research type:

- Qualitative or quantitative ,

- Collecting original data or basing your research on primary and secondary sources,

- Descriptive, correlational, or experimental.

Population and sample:

- The whole population of individuals or entities that meet eligibility criteria to be included in your research,

- The subset of the population that is going to be included in the particular study.

Data collection:

- What methods ( surveys , clinical analysis, biochemical analysis, interviews, experiments) will you use?

- Why are those methods optimal for achieving the desired objectives?

- How can you ensure that the chosen method eliminates bias?

Data analysis:

- How will you sort and code the data obtained?

- What tools, algorithms, or techniques will you use to analyze the data?

Operational issues:

- How much time will you need to collect the research material?

- How are you planning to gain access to the desired set of data or information?

- What obstacles might you encounter and how will you overcome them?

Now, I can’t stress that enough— This part of a research proposal will vary the most from one proposal to another. The outline above will work good for sciences (both social and exact), perhaps not equally great for arts and humanities. At the end of the day, you know your project better than anyone else. You’ll need to make the judgement call as to what methods are best.

6. (Optional) Discuss Ethical Considerations

No, this part isn’t optional because you might just disregard ethics or choose to be the evil scientist. But let’s face it— There aren’t going to be many ethical issues to consider if you’re investigating the vector shapes of tree leaves’ shadows (I kid you not, it’s a legit research issue, my friend did his PhD in Physics about it and absolutely killed it). But if your research has to do with humans, especially in fields such as medicine or psychology, it might introduce ethical problems in data collection , not often encountered by other researchers. You need to take extra care to protect your participants’ rights, get their explicit consent to process the data, as well as consult the research project with the authorities of your academic institution—for that purpose, your proposal needs to contain detailed information regarding these aspects.

7. Present Preliminary or Desired Implications and Contribution to Knowledge

This is the last argument-based part of your proposal. After that, everything will be about “boring” technicalities. This also means, it’s your last chance to convince the decision makers to back your project. Think about it this way— You already explained what exactly is going to be the scope of your project. You detailed the current state of knowledge and identified the most important gaps. You told them what you’re hoping to find out and how you’re planning to do it. Now, talk about the actual, feasible difference your finding can make. How your research can influence the future of the field, or even the very narrow niche. In other words, describe the implications of your research such as:

- How can your research challenge the current underlying assumptions on the subject matter?

- How can it inform future research and what new areas of research can it propel?

- What will the influence of your research be on policy decisions?

- What sorts of individuals, organizations, or other entities can your research benefit?

- What will be improved and optimized on the basis of your research?

All that while keeping one crucial thing in mind— Talking about the practical implications of your study shouldn’t sound like daydreaming. However “preliminary” or “desired” the said implications are, you need to base those on very clear evidence. In short, this section is about:

- Reiterating the gaps in the current state of knowledge.

- Showing how you’ll contribute to a new understanding of certain problems or even a scientific breakthrough.

- Clearly showing how your findings can be acted upon and what feasible change those actions will bring about.

And yes, it does sound lofty, but it’s true. As a researcher, you’re expanding the scope of human comprehension! Don’t shy away from highlighting the actual change you can bring to the world (or even just your narrow field, it’s just as valuable).

8. Detail Your Budget and Funding Requirements

If you do have a supervisor already, it’s best to consult this part with them. They’ve most likely submitted similar documents to the institution you’re reaching out to and will be able to provide invaluable insights on how much you can realistically expect to get paid. If you’re at a different stage of the application process, here are the key elements you should include in the funding requirements section:

- Operational costs: materials, equipment, access to labs, any software you might need, etc.

- Travel costs: including transportation, accommodation, and living costs.

- Staff: if you’ll need human assistants to help you carry out your research, you’ll most likely need to pay them. It might be the case that junior researchers or students will be able to help you to obtain necessary credits for graduation, but it’s still a cost for their institution you’ll need to include in the budget.

- Allowance: you’ll most likely have to give up on other duties that help you pay bills (be that teaching, publishing, or administrative work) but you still need those bills paid. Treat your allowance as a regular salary you need to make a living.

Note: if possible, do leave yourself some wiggle room and request for conditional extra allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays, or unexpected cost rises.

9. Provide a Timetable

Certain grant schemes come with predefined timetables (e.g. placements offered for 3, 6, or 9 months) and in such cases there’s no need for a very detailed timeline—all you need to do is convince them that the period of time for which you’ll be receiving funding is sufficient for you to complete the project. When you’re writing a proposal for a standalone project, detailing a timeline can help support your budget. The most common format is, you guessed it, a table. Divide your research into stages, list, in bullet points, what actions you’ll need to take at each stage, and list rough deadlines. I know I don’t have to tell you that but please, keep Murphy's Law in mind. Perhaps not everything that can go wrong will, but, well, expect the unexpected and be conservative with deadlines. All in all, it's easier to explain why you no longer need 3 months worth of funding than it is to ask for 6 months’ extra allowance. Don’t let delays derail your project. That’s all I have to say.

10. End with a List of Citations

This one really is self-explanatory, isn’t it. As a scholar, you need to cite the sources you’re referring to (no matter how harshly critical you are of some of those:)). Citations in research proposals can either be included in the form of references (so only the pieces of literature you actually cited) or bibliography (everything that informed your proposal). As is the case with many other elements of the proposal, the correct format depends almost exclusively on the institution you’re applying to, so make sure to check it with them or consult with your supervisor about which one is preferred. The same goes for the style of referencing. Most US universities use APA or Chicago style but each has its own set of rules and preferences. Double-check with the list of guidelines on their website. When in doubt, reach out to the head of the department you’re wishing to work with. (No, using the wrong style won’t ruin your chances but I don’t think I need to tell you how particular certain academics are so let’s not step on any toes, shall we?)

Found this post useful?

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Get notified as more awesome content goes live.

(No spam, no ads, opt-out whenever)

You've just joined an elite group of people that make the top performing 1% of sales and marketing collateral.

And that’s a wrap!

To sum up, this is what a typical research proposal should include:

- Introduction

- Context and Background

- Literature Review

- Aims and Objectives or Research Questions

- Methods and Design

- Ethical Considerations

- Contributions to Knowledge or Implications

Writing a research proposal can be hard and feel like a never-ending process. It really isn’t much different from writing an actual thesis or dissertation. Yup, this is my roundabout way of saying: don’t get disheartened. Allow yourself a few months up to half a year to complete your proposal, follow the steps outlined in this guide and, whenever in doubt, remember to reach out to senior researchers for help. Keeping my fingers crossed for your proposal!

Hi, I'm John, Editor-in-chief at Storydoc. As a content marketer and digital writer specializing in B2B SaaS, my main goal is to provide you with up-to-date tips for effective business storytelling and equip you with all the right tools to enable your sales efforts.

Make your best pitch deck to date

Try Storydoc for free for 14 days (keep your decks for ever!)

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Research Proposal: Checklist Example

If you are a PhD doctoral or Master’s student approaching graduation, then a large research project, dissertation, or thesis is in your future. These capstone research projects take months if not years of preparation, and the first step in this process is first writing a compelling, organized, and effective research proposal.

Check out the key differences between dissertation and thesis .

Research Proposal Checklists Are Important

We’ve got some good and bad news for the PhD and Master’s graduate students out there.

First, the bad news. Research proposals are not easy to write. They require lots of preparation and planning. They can also seem to be an administrative task, with your PhD advisors constantly reminding you to write something that you’re not yet sure about. And of course, it’s also yet another written document that could be rejected.

Now, the good news. Research proposals help you organize and focus your research. They also eliminate irrelevant topics that your research cannot or should not cover. Further, they help signal your academic superiors (professors, advisors, scientific community) that your research is worth pursuing.

Research proposal checklists go one step further. A research proposal checklist helps you identify what you will research, why it is important and relevant, and how you will perform the research.

This last part is critical. Research proposals are often rejected for not being feasible or being unfocused. But an organized research or thesis proposal checklist can help you stay on topic.

This article goes into the following topics about research proposal checklists:

What is a Research Proposal?

Research proposals are documents that propose a research project in the sciences or academic fields and request funding or sponsorship.

The primary objective is to convince others that you have a worthwhile research project as well as an organized plan to accomplish it.

A main purpose of a research plan is to clearly state the central research topic or question that you intend to research while providing a solid background of your particular area of research.

Your research proposal must contain a quick summary of the current literature , including gaps in your research area’s knowledge base as well as areas of controversy, which together demonstrate your proposal is relevant, timely, and worth pursuing.

But what functions does a research proposal perform?:

Research proposals explain your research topic

An effective research proposal should answer the following questions:

- What is my research about?

- What specific academic area will I be researching?

- What is the current scientific and academic literature?

- What are the accepted theories in my area of research?

- What are gaps in the knowledge base?

- What are key questions researchers are currently trying to answer?

Research proposals explain why your research topic is important

A compelling research proposal should answer the following questions:

- Why is my research important?

- Why is my research interesting to both academics and laypeople?

- What are my research questions ?

- How does my research contribute to the literature?

- How will my dissertation or thesis answer gaps or unsolved questions?

- How or why would my research earn funding in the future?

- How does my research relate to wider society or public health?

Research proposals explain how you will perform your research

A feasible research proposal should answer the following questions:

- How will my research be performed?

- What are my exact methods?

- What materials will I need to purchase?

- What materials will I need to borrow from other researchers in my field?

- What relationships do I need to make or maintain with other academics?

- What is my research proposal timeline?

- What are the standard research procedures?

- Are there any study limitations to discuss?

- Will I need to modify any research methods? What, if any, problems will this introduce?

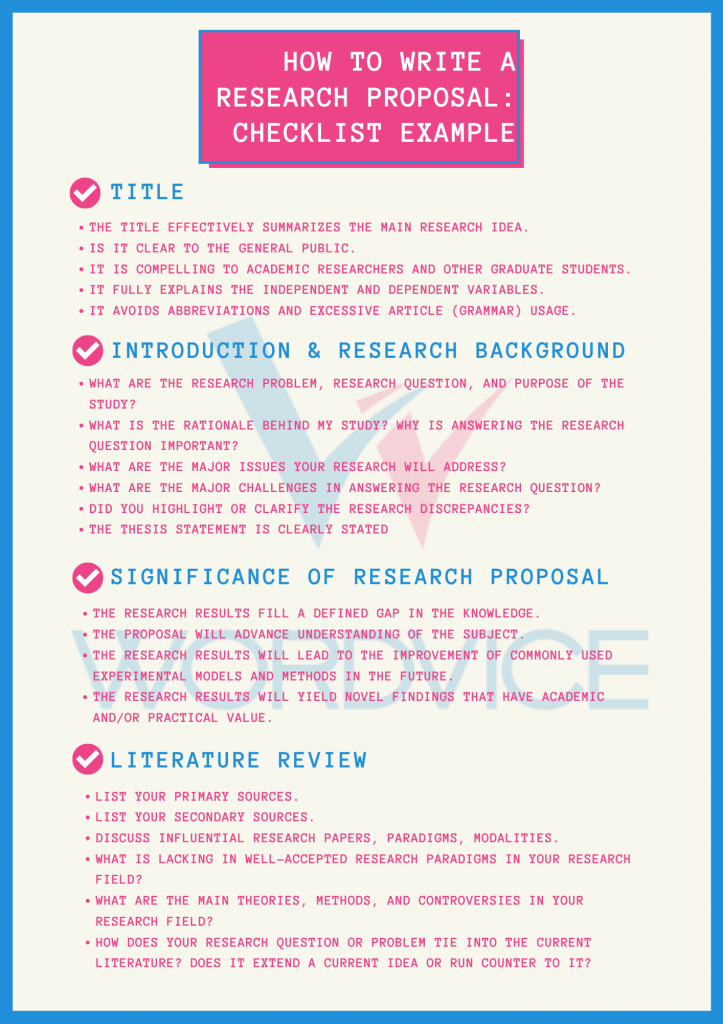

Research Proposal Example Checklist

Use this research proposal example checklist as an aid to draft your own research proposal. This can help you decide what information to include and keep your ideas logically structured.

Remember, if your research proposal cannot effectively answer every single question below, then you may want to consult your advisor. It doesn’t mean your chosen research topic is bad; it just means certain areas may need some additional focus.

Click here for the full Research Proposal Example Checklist in .pdf form

Research Proposal Title

The title of your research proposal must attract the reader’s eye, be descriptive of the research question, and be understandable for both casual and academic readers.

The title of your research proposal should do the following:

- Effectively summarize the main research idea

- Be clear to the general public

- Be compelling to academic researchers and other graduate students

- Fully explain the independent and dependent variables

- Avoid abbreviations and excessive use of articles

Research Proposal Introduction and Research Background

The introduction typically begins with a general overview of your research field, focusing on a specific research problem or question. This is followed by an explanation of why the study should be conducted.

The introduction of your research proposal should answer the following questions:

- What is the research problem, research question, and purpose of the study?

- What is the rationale behind my study?

- Why is answering this research question important?

- What are the major issues your research will address?

- What are the major challenges in answering the research question?

- Did you highlight or clarify the research discrepancies?

Significance of Research Proposal

Your proposal’s introduction section should also clearly communicate why your research is significant, relevant, timely, and valid.

To effectively confirm the significance of your proposal, make sure your study accomplishes the following:

- The research results fill a defined gap in the knowledge.

- The proposed study will advance understanding of the subject.

- The research results will lead to the improvement of commonly used experimental models and methods in the future.

- The research results will yield novel findings that have academic and/or practical value.

Research Proposal Literature Review

In the literature review section, you should provide a review of the current state of the literature as well as provide a summary of the results generated by your research. Determine relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research to support your research claim.

State an overview and significance of your primary resources and provide a critical analysis highlighting what those sources lack and future directions for research.

- List your primary sources.

- List your secondary sources.

- Discuss influential research papers, paradigms, and modalities.

- What is lacking in well-accepted research paradigms in your research field?

- What are the main theories, methods, and controversies in your research field?

- How does your research question or problem tie into the current literature? Does it extend a current idea or run counter to it?

Research Proposal Theoretical Methodology and Design

Following the literature review, it is a good idea to restate your main objectives, bringing the focus back to your own project. The research design or methodology section should describe the overall approach and practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To help you write a clear and structured methodology, use your plan and answer the following issues. This will give you an outline to follow and keep you on track when writing this section of your research proposal.

- Explain whether your research method will be a study or an experiment.

- Is your research for a PhD dissertation or Master’s program?

- Explain the theoretical resources motivating your choice of methods.

- Explain how particular methods enable you to answer your research question.

- Credit any colleagues or researchers you will collaborate with.

- Explain the advantages and disadvantages of your chosen methodology.

- What is the timeline of your research experiment or study?

- Compare/contrast your research design with that of the literature and other research on your topic.

- Are there any different or alternative methods or materials that will be used?

Additionally, explain how your results will be processed:

- How will your research results be processed and interpreted?

- What data types will your results be in?

- Explain the statistical models and processes you must perform (e.g. Student’s t-test).

- Will your study be more statistically rigorous than other studies?

Read about how to explain research methods clearly for reproducibility .

Research Proposal Discussion and Conclusion

Your discussion and conclusion section has an important purpose: to persuade the reader of your proposed research study’s potential impact. This section should also directly address potential weaknesses and criticisms put forth by other researchers and academics.

- Explain the limitations and weaknesses of the proposed research.

- Explain how any potential weaknesses would be justified by extenuating circumstances such as time and financial constraints.

- What, if any, alternative research questions or problems naturally can be answered in the future?

- How does the research strengthen, support, or challenge a current theoretical framework or model?

References and Bibliography

Although it comes at the end, your reference section is vital and will be carefully scrutinized. It should include all sources of information you used to support your research, and it should be in the correct citation format.

- Provide a complete list of references for all cited statements.

- Make sure citations are in the correct format (e.g. APA, Chicago, MLA, etc.)

- References are present in the introduction, literature review, and methodology sections.

Use the Wordvice APA Citation Generator to instantly generate citations in APA Style, or choose one of the formats below to generate citations for the citation style of your academic work:

Using Research Proposal Examples

Although every research proposal is unique, it is a good idea to take a look at examples of research proposals before writing your initial proposal draft. This will help you understand the academic level you should aim for. Be sure to include a reference list at the end of your proposal as described above.

In addition to reading research proposal examples, you should also outline your research proposal to make sure no crucial information or research proposal sections are missing from your final manuscript. Although the sections included in a research proposal may vary depending on whether it is a grant, doctoral dissertation, conference paper, or professional project, there are many sections in common. Knowing the differences before you draft will ensure that your proposal is cohesive and thorough.

Research Proposal Proofreading and Editing

It’s vital to take the time to redraft, edit, and proofread a research proposal before submitting it to your PhD advisor or committee. Researchers and graduate students usually turn to a professional English editing service like Wordvice to improve their research writing.

Our academic services, including thesis editing , dissertation editing , and research paper editing , will fully prepare any academic document for publication in academic journals.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on 13 June 2023.

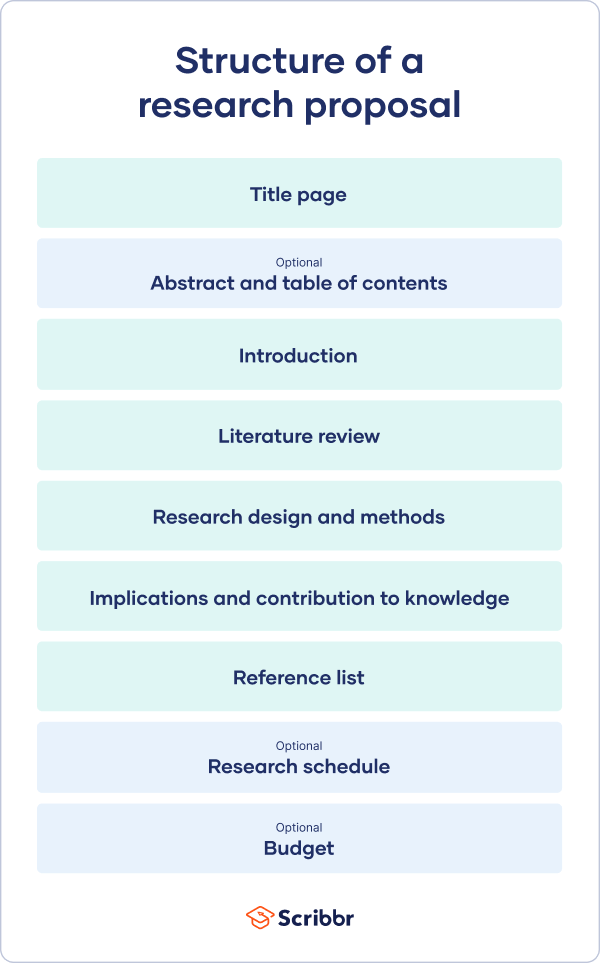

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organised and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, frequently asked questions.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: ‘A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management’

- Example research proposal #2: ‘ Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use’

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesise prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasise again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement.

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.