- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2021

Recognising values and engaging communities across cultures: towards developing a cultural protocol for researchers

- Rakhshi Memon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6586-2248 1 ,

- Muqaddas Asif 2 ,

- Ameer B. Khoso 2 ,

- Sehrish Tofique 2 ,

- Tayyaba Kiran 2 ,

- Nasim Chaudhry 2 ,

- Nusrat Husain 3 , 4 ,

- Sarah J. L. Edwards 1 on behalf of

Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning (PILL)

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 47 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3261 Accesses

5 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Efforts to build research capacity and capability in low and middle income countries (LMIC) has progressed over the last three decades, yet it confronts many challenges including issues with communicating or even negotiating across different cultures. Implementing global research requires a broader understanding of community engagement and participatory research approaches. There is a considerable amount of guidance available on community engagement in clinical trials, especially for studies for HIV/AIDS, even culturally specific codes for recruiting vulnerable populations such as the San or Maori people. However, the same cannot be said for implementing research in global health. In an effort to build on this work, the Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning and University College London in the UK sought to better understand differences in beliefs, values and norms of local communities in Pakistan. In particular, they have sought to help researchers from high income countries (HIC) understand how their values are perceived and understood by the local indigenous researchers in Pakistan. To achieve this end, a group discussion was organised with indigenous researchers at Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning. The discussion will ultimately help inform the development of a cultural protocol for researchers from HIC engaging with communities in LMIC. This discussion revealed five common themes; (1) religious principles and rules, (2) differing concepts of and moral emphasis on autonomy and privacy, (3) importance of respect and trust; (4) cultural differences (etiquette); (5) custom and tradition (gift giving and hospitality). Based on the above themes, we present a preliminary cultural analysis to raise awareness and to prepare researchers from HIC conducting cross cultural research in Pakistan. This is likely to be particularly relevant in collectivistic cultures where social interconnectedness, family and community is valued above individual autonomy and the self is not considered central to moral thinking. In certain cultures, HIC ideas of individual autonomy, the notion of informed consent may be regarded as a collective family decision. In addition, there may still be acceptance of traditional professional roles such as ‘doctor knows best’, while respect and privacy may have very different meanings.

Peer Review reports

The debate on the ethics of international clinical research involving collaboration with Low and Middle Income Countries (LMIC) is of considerable significance because of increased interest in global health research [ 1 ]. This makes it an imperative that research is equitable, just, relevant to the context in which it is organised and responsive to local health needs. Global health ethics is emerging as a new discipline [ 2 , 3 ]. Although the field of global health ethics is largely underpinned by the concepts of bioethics from HIC, it is increasingly important to examine such concepts in different cultural and social contexts. Concerning ethics, Bernal and Adames [ 4 ] stated that “we caution to impose views, norms and values of the world’s dominant HIC society onto vulnerable populations such as ethno-cultural groups”. Considered in the round, the discipline of research ethics is mostly ‘Euro-American’ and not often recognised, let alone adapted for, within many other cultures [ 5 , 6 ]. For example, Zaman and Nahar note that when conducting research in Bangladesh, they found the word ‘research’ did not exist in the Bengali language and when translated meant ‘finding a lost cow’. Global health projects have too often been developed without the input of LMIC local partners, leading to claims of neo-colonialism [ 7 ]. The conditional adherence to HIC governance models by the funders of research who are predominantly from the global north could similarly be seen as neocolonial.

In defining “Global Health Ethics” Myers [ 8 ] likewise observed “that existing literature on global health ethics has majorly originated from north American medical doctors. This is corroborated by random searching of literature using the terms ‘community engagement’, ‘global health ethics’, ‘global health research and ‘global health partnerships’ from 2016 to 2020 revealed around 102 articles mostly from HIC. This was inferred by the first author’s names. Therefore, the question of whose perspectives, views, plans as well as advances, the global health ethics actually represents and how and why—invites scrutiny” [ 8 ]. As Japanese historian William LeFleur once commented, though, “bioethics has become international, it has not become ‘internationalised” [ 9 ]. HIC principles of bioethics focus on the individual’s rights of autonomy and consent disregarding the collectivistic cultural norms of interconnectedness of role of the family and how shared decision making is intertwined in some cultures. Consequently, despite all good intentions towards research participants, researchers possess a certain ‘ethnocentrism’ before research begins. While research carried out in a respectful manner has maximised social value [ 10 ], community engagement or community consultation in the proposed research projects has emerged as a requirement for ethical international research [ 7 ]. It refers to participation and involvement of people, groups, structures or community members for planning, design, decision-making, and governance to promote people centred delivery of services [ 11 ]. It is recently seen as critical and fundamental component of many health initiatives, particularly during disease outbreaks [ 12 ]. This entails understanding of the emergent global health gaps and of the lifestyle of potential research participants. In their book, Understanding Global Health, Velji and Bryant [ 13 ] state that when conducting research, global health ethics not only challenge its practitioners to identify potential research subjects but to assure respect for justice, dignity and human rights. It is necessary to understand the different mind sets, environments and frameworks of thinking while undertaking collaborative research in LMIC [ 2 ]. Kolev and Sprowl [ 14 ] emphasised the importance of addressing those aspects of health systems that continue to hinder efforts to meaningfully engage with patients, their families and local communities. In today’s world, when researchers may not reside in the communities where they work, knowing their experiences and culture i.e. differences in political, cultural and social structures, systems and processes among communities, social norms and beliefs is important.

With the World Health Organisation (WHO) global health agenda [ 15 ] and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) of 2030 [ 16 ] more and more young researchers want to apply their skills to global health research. It is a good thing that more and more research is being carried out in the pursuit of global health and that researchers and institutions from HIC are invited to build research capacity and capability. As part of these projects, researchers from HIC are often involved in community engagement workshops. In culturally diverse environments where linguistic and cultural barriers exist, standards for effective communication might be daunting [ 2 , 3 ]. Researchers from HIC are often unsure of the cultural norms, values and beliefs of local communities. Consequently, they may sometimes unknowingly come across as insensitive and disrespectful. “ How do we begin to think about unintended consequences when we are doing what we presume as ‘good’ for the patient, for their family, the community and society at large” [ 12 ].

Implementation of health research requires understanding and engaging key stakeholders at all levels of the local health systems. Cultural and linguistic variances, historic legacy of mistrust, manipulation within the research enterprise and scientific colonisation concerns further intensifies these conditions [ 17 ]. MacLachlan [ 18 ] highlighted how communities may see foreign aid workers as symbols of colonialism, capitalism, and eurocentrism. Conversely, communities may perceive the doctor from HIC to have magical powers and superior expertise. This can give rise to unrealistic expectations. To counter this, honesty must be a universal commitment [ 12 ].

Existing literature in research ethics has grappled with differences in culture to the extent that codes of conduct are now being developed to redress the balance. For example, the San Code of Research Ethics is written with the San people of South Africa for all research involving them [ 19 ]. Another code, the Te Ara Tika—Guidelines for Maori Research Ethics: A Framework for Researchers and Ethics Committee Members seeks to secure sensitivity to culture in the structural protections of research participants [ 20 ]. Community engagement guidance in clinical trials is available, particularly for HIV/AIDS in Africa [ 21 ] but there is a gap in guidance for implementing research in global health. To make interventions more relevant and meaningful to local people, whichever culture they are from, community participation has been regarded as essential.

Building on existing work in clinical trials and for research with specific cultures, thought to be vulnerable and in need of special consideration, more clear and specific guidance is needed for incorporating effective and relevant community engagement methodologies into planning and implementation [ 22 ]. Such guidance can help implementation researchers to engage community stakeholders in more strategic and practical ways to enhance quality and meaningful application of results in order to improve health and health system outcomes. This would not only assist planning for specific projects but would also be a useful contributor to ensure that new and early career researchers are better equipped to consciously and thoughtfully engage with communities affected by their work in ways that are respectful and empowering [ 22 ].

How we should think about differences in values between cultural and wider communities is a familiar topic to philosophers, yet the limits to cultural and moral relativism in global health research is yet to be resolved. If communities and cultures across the world were to have very different values, it would be almost impossible to find common ground and global health research would be effectively impossible to pursue. Rather than to start with relative moral values, it is possible to converse with members of different cultures about their values and to devise a ‘bottom up’, or rather a participatory framework informed by experience of global collaborations in the field. As a contribution towards moving forward the global health research endeavours, development of a cultural protocol would be a fundamental starting point to help dispel false preconceptions and improve communication for a better understanding of the research environment and its people. The essence of a participatory approach is to recognise ‘that people whose lives are to be changed by developing interventions should have a say in what these changes are to be, and how they will take place’ [ 23 ]. Although, there are various ways and approaches designed to facilitate stakeholder engagement at the national or institutional level [ 22 ], these tools are intended to assist as aids to discussion around community involvement issues within a particular partnership and/or as a way of exploring comparisons between partnerships. These are at a very early stage of development and have not yet been tested on the ground [ 24 ].

Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning (PILL) has many visiting researchers from HIC, who are involved in community engagement, training and development. PILL and University College London (UCL), UK have collaborated to identify the gap and to gain an understanding of the beliefs, cultural norms, and values of local communities with the aim to better understand and manage the differences in values and ethics in a different cultural setting. The rationale underpinning the development of a cultural protocol is that when there is no clear communication and understanding of the beliefs, culture, norms, nuances and values of a particular community, there is no foundation on which to build rapport, respect and trust needed for initiating the process of community engagement itself. If we believe in local participation and community engagement to be core values underpinning participatory approach, we need to make a concerted effort to gain insight into the belief system, norms and values of the communities we work with.

A culture protocol for researchers is not intended as a substitute for community engagement which itself is an important process for eliciting views and values of particular communities and relates to particular research proposals and projects. A cultural protocol, however, would prepare researchers to approach the process of community engagement with respectful cultural sensitivity. The aim of this paper is to present findings from a discussion group towards development of a cultural protocol for researchers for community engagement in Pakistan.

Methodology

This paper is based on a discussion group with local indigenous researchers from Pakistan.

The discussion group was convened on January 11th, 2019 at Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning (PILL) head office in Karachi with four other PILL centres from different cities via zoom. The discussion was in English and Urdu to facilitate communication. The participants were researchers from PILL (n = 32), they were all qualified psychologists who had experience of community engagement and partnership relied research activities across Pakistan and had volunteered for the group discussion. The discussion group lasted for one hour and 28 min. Written consent was taken from all the participants to audio record the discussion and to use the materials for publication.

A semi structured list of questions to facilitate the discussion was developed following literature review. This explored researcher cultural beliefs and the impact on their research activities, challenges and responsibilities as a researcher coming from another country. The discussion was moderated by RM (based in UK with a background in health services management and improvement sciences). The group discussion revolved around the experiences and learning of local researchers from community engagement activities.

The audio recording of discussion was transcribed by a qualitative researcher. The transcription was translated into English by a bilingual researcher. Translated transcript was then back translated into Urdu for checking by an independent researcher. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the discussion [ 25 ]. Steps involved in the analysis included familiarisation, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and finally transforming it in a report form. RM and MA did initial line by line coding and finalising the themes both were supervised by an experienced qualitative researcher (TK) to maintain data credibility and trust worthiness. TK reviewed the transcript and analysis.

The results presented here are based on the general themes that emerged from the discussion. The five themes from the discussion include: (1) religious principles and rules, (2) concept of autonomy and privacy, (3) notion of respect and trust, (4) cultural differences (etiquette) and (5) custom and tradition (gift giving and hospitality). The five themes which emerged from the discussion are as follows and the key messages from these five themes are in Table 1 .

Religious principles and rules

Following the British colonial rule in India, Pakistan was founded in 1947 on the basis of religion; Islam. Hence, religion and culture are very much intertwined. Most societal norms are underpinned by religious beliefs. The community religious leaders once engaged can be a great ally. This was stated in the Group “I think it is better to get hold of the imam in the community first. He prepares the ground for us by telling them who we are? And what we are trying to do? It makes our work much easier”.

As Islamic traditions and practices are virtually ingrained in all parts of Pakistani life, it is an imperative to understand the significance of prayer, religious festivals and festivities have in everyday life. This was expressed several times in the discussion Group “If it is prayer (namaaz) time specially Friday (Jummah) prayer we should not work during that time. Also, late afternoon (Asar prayer) and at sunset (Maghrib prayer). These prayer times are important so there should not be a clash with these times”. Prohibition of food in Ramadan and music and other festivities during the month of Moharram were also mentioned “During Ramadan people will be offended if you eat in public as everyone should be observing fast” “In Moharram, especially in Shia Sect we don’t play music or watch movies as it is the month of mourning”.

Islamic ideals and customs were further reiterated. A discussant mentioned “ We do Qurbani (slaughter of an animal in the name of Allah) on Eid ul Adha. It may be shocking for foreigners but it is our religion, we do it in the name of Allah”.

Concept of autonomy and privacy

It would be quite usual for the whole family to be involved in discussions and decision making on issues which in the HIC maybe perceived as violation of autonomy. The tension between the primacy of autonomy in HIC bioethics literature is sometimes in contrast and incompatible with the social value system of interconnectedness and interdependence within cultures such as Pakistan which are religiously grounded. “The whole families come and attend clinic with the patient. When people travel from far away villages, they have to camp outside hospitals for days as it is too costly and too far to go home every day”.

Respect for the elders of the family and especially the husband in a male dominated society make ‘surrogate’ decision making an expectation and the norm. “….. People come with their mother, husband, sometimes also friends. Mostly husband or mother will speak for them and decide.”

Notion of respect and trust

Distrust still exists within the (illegal) migrant community fleeing from Afghanistan to Pakistan since the Afghanistan war, as they may not possess identity cards. Young men dressed in foreign clothes are perceived to be government officials. “ So again it is related to credibility, integrity and trustworthiness. We experience in Orangi Town (in Karachi) that they don’t trust us. Actually as we are young men dressed in foreign clothes so they think that we are someone else, I mean they think we are ISI (Intelligence Services) or like that”.

As segregation still exists in most families, traditionally male researchers will be restricted from home visiting. This was expressed by a discussant “Only females can visit homes, male have to wait outside”.

However, being respectful to customs and traditions goes a long way to build trust. As someone in the Group said “if you sit on the chair and others are sitting on the floor, it is not good. It is all about respect”.

Family and family loyalties are held sacred in the Pakistani culture and social fabric of the society. This value system is derived from the Islamic belief of individual and collective responsibility for the welfare of kin and kinship. This translates into family loyalty as long as the family member fulfils the criteria, be it nuclear or extended, family comes above other social relationships and even commercial arrangements. As one discussant in the group eluded “ My uncle who is a cloth merchant wanted me to manage his shop when I completed my university education".

Cultural differences (etiquette)

Eye contact and physical touching between genders is considered disrespectful and an invasion into privacy. Eye contact with the elders is considered to be challenging to the status of the elders and therefore also disrespectful and rebellious. The cultural polarisation of understanding of the same gestures between cultures can be perceived as disrespect, misunderstanding and offensive; this can be detrimental to community engagement and distrust of researchers from HIC. “Making eye contact with your elders and opposite gender is considered disrespectful”.

The segregation of genders historically, religiously and traditionally has required ‘Parda’ separation between male and female outside the family confines. This cultural conditioning and tradition continues. As observed by one discussant: “Foreign professionals need to consider the cultural values before visiting other cultures. As most people don’t like to sit close to them or do hugs. Female professionals hesitate in sitting close with male foreigners”. The point was further reinforced by another “The girls don’t even shake hands with the boys, when they greet each other girls’ shake hands with each other but not with the boys”.

A similar comment was made in the Group: “You should prefer to wear long shirts with shawl and avoid wearing shorts or wear shawl or scarf. Is this relevant to female or is it relevant to male? Yes, both—So, they just should not go in shorts and t-shirts. Not shorts just jeans, trousers and shirts are best for male”.

The dress code signifies not only adherence to cultural norms of modesty but also signals religious significance. “I believe if people coming in foreign dress, they are seen as having more professional attitude, and coming with more professional background. They are having some kind of knowledge and people take them very seriously. Their comments and suggestions on any issue are taken very seriously”.

Interestingly, personal space and boundaries are not the same as in the west. People may stand quite close when communicating. Also, albeit out of respect they may call male ‘bhai’ (elder brother) and female ‘baji’ (elder sister). As a result, they perceive that they now have a close enough relationship “it is very common for people to become very friendly and ask very personal questions” and “they ask personal and intimate questions and also ask for personal numbers”.

Custom and tradition (gift giving and hospitality)

Pakistanis are renowned for their generosity and their love and respect towards their guests. In Islam, a guest is a blessing from Allah. So, however poor people are, they will go out of their way to welcome their guests with open arms. They believe that this would please Allah. “I don’t know what foreigners do when they go for community field work but in our culture, they offer us tea, coffee, eggs, even seasonal fruits and many other gifts”. Also, “we have to take tea with them and have lunch when they offer us meal, to give them assurance that we belong with them and to win their trust”.

Development of a cultural protocol for researchers would be a desirable step in fostering relationships between researchers from HIC and the communities they wish to recruit in research. In addition to accepted practices of community engagement and for special regard for protecting vulnerable cultures, observing a cultural protocol is another way in which researchers can show respect towards different cultural norms and values. A protocol would then become an integral part of community and participatory engagement process. We identified a number of key themes from discussion group including role of religious principles and rules, issues related to autonomy and privacy, notion of respect and trust, cultural differences in terms of etiquette and customs and traditions.

Previous evidence shows that involvement of religious leaders in raising awareness and community engagement is hugely important and they can play a significant role in bringing community on-board even when addressing taboo topic [ 26 ]. Therefore, engaging with and empowering religious leaders through capacity building and offering them support, recognition and appreciation can be an important component of community engagement [ 26 ]. Similar findings have been highlighted through this discussion group where researchers strongly emphasised the role of respecting religious practices and involving religious leaders to strengthen community involvement and trust.

An example of such a difference lies in the apparent need in HIC guidelines to protect the anonymity and confidentiality of participants [ 27 ]. However, this situation is different in Asian countries like Pakistan. In group discussion researchers emphasised the importance of shared decision making in Pakistani families. Accepting decisions made by elder members of the family is considered as matter of respect in Pakistani families and young people think that influence of elders is propitious for their life [ 28 ]. The joint decision making described in the results resonates with Dr Rose’s [ 12 ] narration in his book; A Blind Eye. He states ‘The Center is a buzz of clinical activity, like every facility in which I have worked in the developing world, the concept of privacy is wholly irrelevant. Observed by extended family, elders, and sometimes even village chiefs, several examinations take place in each room’.

Hospitality and gift giving is also considered as a universal behaviour in Pakistani culture that helps to integrate a society [ 29 ]. However, in a research context, gift giving poses an ethical challenge both for researchers and participants, since gift giving could be perceived by researchers from HIC as inducements, or worse, as bribes. In the discussion group, researchers highlighted that people in different communities express their hospitality by giving gifts. Therefore, people coming from other cultures should be aware of this gesture before visiting any community setting and be prepared to refuse gifts politely so that researcher-participant relationship is maintained.

In community based research, successful partnership between researchers and participants helps to generate trust and synergy [ 30 ]. Synergy in research is generated when participants hold space for a third culture that aims to integrate perspective of community members and academics, in order to generate innovative and valuable research [ 31 ]. Regarding trust Alpers [ 32 ] observed that ‘Cultural and linguistic differences may make it particularly challenging to build a trustful and positive relationship with patients of ethnic minority’. “Nepotism is seen positively as it assures hiring people who can be trusted” [ 33 ]. This would be an antithetical value stance from a HIC perspective. Attum, Waheed and Shamoon [ 34 ] in discussing cultural competence in the care of Muslim patients and their families state that “It is common understanding that women dress modestly. Men are mostly dressed to the knees or past the knees too. Although there is an impression that women dress modestly compared to men, but many men observe similar rules of modesty”.

Community engagement is concerned with directly approaching the host community and tapping into the community knowledge to identify the needs, issues and concerns. The community as the key stakeholder within the research process provides insight into the cultural and social context which is, as such, irreplaceable and invaluable to achieve the goals of the research. The enabling function of the protocol will be to inform and prepare researchers from HIC before they approach the community engagement process.

However, it is equally important to acknowledge that there are further sub-cultures within the different provinces of Pakistan so the development of a cultural protocol and guidance for community engagement with specific cultures will not only benefit visiting researchers from HIC it will also be of value to local indigenous researchers visiting different provinces within Pakistan.

In summary, from available literature and discussion group, it has been clear that understanding local cultural values and norms are important to understand before initiating community engagement in health research primarily to facilitate recruitment. Underpinned by this reflective inquiry, development of a cultural protocol for researchers from HIC can be an important part of an overall engagement strategy in Pakistan. This could potentially provide pathways to develop a cultural protocol for researchers in LMIC to ensure local cultural norms and values for research are considered.

Availability of data materials

A record of the full discussion used for the article is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Low and middle income countries

High income countries

Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning

University College London

Benatar SR. Justice and medical research: a global perspective. Bioethics. 2001;15(4):333–40.

Article Google Scholar

Benatar SR. Reflections and recommendations on research ethics in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(7):1131–41.

Marshall PA. Informed consent in international health research. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics JERHRE. 2006;1(1):25–42.

Bernal G, Adames C. Cultural adaptations: conceptual, ethical, contextual, and methodological issues for working with ethnocultural and majority-world populations. Prev Sci Off J Soc Prev Res. 2017;18(6):681–8.

Zaman S, Nahar P. Searching for a lost cow. Ethical dilemmas of doing medical anthropological research in Bangladesh. Med Anthrop. 2011;23(1):153–63.

Google Scholar

Stapleton G, Schroder-Back P, Laaser U, Meershoek A, Popa D. Global health ethics: an introduction to prominent theories and relevant topics. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23569.

Provenzano AM, Graber LK, Elansary M, Khoshnood K, Rastegar A, Barry M. Short-term global health research projects by US medical students: ethical challenges for partnerships. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2):211–4.

Defining MC. Global health ethics. J Bioethic Inq. 2015;12(1):5–10.

Fox R, Swazey J. Guest editorial: ignoring the social and cultural context of bioethics is unacceptable. Camb Quart Healthcare Ethics. 2010;19(3):278–81.

Molyneux S, Bull S. Consent and community engagement in diverse research contexts: reviewing and developing research and practice: participants in the community engagement and consent workshop, Kilifi, Kenya, March 2011. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2013;8(4):1–18.

Barker KM, Ling EJ, Fallah M, et al. Community engagement for health system resilience: evidence from Liberia’s Ebola epidemic. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:416–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz174 .

Rose A. A blind eye; 2019. [Cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.thebigroundtable.com/wpcontent/themes/brt/img/illustrations/blindness.png.

Velji A, Baryant JH. Global health ethics chapter. In: Markle WH, Fisher MA, Smego RA, editors. Understanding global health. New York: McGraw Hill; 2007. p. 295–317.

Odugleh-Kolev A, Parrish-Sprowl J. Universal health coverage and community engagement. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(9):660–1. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.202382 .

World Health Organisation. Global health agenda. (2020). Available from https://www.who.int/about/vision/global_health_agenda/en/.

United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: Division for Sustainable Development Goals; 2015.

King KF, Kolopack P, Merritt MW, Lavery JV. Community engagement and the human infrastructure of global health research. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15(1):84.

Maclachlan M. The aid triangle: recognising the human dynamics od dominance, justice and identity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; Zed Books; 2010.

Book Google Scholar

San Code of Research Ethics; 2017. [Cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.globalcodeofconduct.org/affiliated-codes/.

Health Research Council of New Zealand. TE ARA TIKA - guidelines for māori research ethics: a framework for researchers and ethics committee members; 2010. [Cited 2019 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.hrc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/Te%20Ara%20Tika%20FINAL%202010.pdf.

UNAIDS AVAC. Good Participatory Practice guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention trials. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011.

Glandon D, Paina L, Alonge O, Peters DH, Bennett S. 10 Best resources for community engagement in implementation research. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(10):1457–65.

Yang Y. Commitments and challenges in participatory development: a Korean NGO working in Cambodia. Dev Pract. 2016;26(7):853–64.

Stott L, Keatman T. Tools for exploring community engagement in partnerships; 2005.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Ruark A, Kishoyian J, Bormet M, Huber D. Increasing family planning access in Kenya through engagement of faith-based health facilities, religious leaders, and community health volunteers. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(3):478–90.

Turcotte-Tremblay AM, Mc Sween-Cadieux E. A reflection on the challenge of protecting confidentiality of participants while disseminating research results locally. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(1):5–11.

Qidwai W, Khushk IA, Allauddin S, Nanji K. Influence of elderly parent on family dynamics: results of a survey from Karachi, Pakistan. World Family Med J Incorp Middle East J Family Med. 2017;99(4100):1–7.

Sherry JF Jr. Gift giving in anthropological perspective. J Consum Res. 1983;10(2):157–68.

Coombe CM, Schulz AJ, Guluma L, Allen AJ III, Gray C, Brakefield-Caldwell W, Guzman JR, Lewis TC, Reyes AG, Rowe Z, Pappas LA. Enhancing capacity of community–academic partnerships to achieve health equity: results from the CBPR partnership academy. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(4):552–63.

Lucero JE, Emerson AD, Beurle D, Roubideaux Y. The holding space: a guide for partners in tribal research. Progress Commun Health Partnerships Res Educ Action. 2020;14(1):101–7.

Alpers LM. Distrust and patients in intercultural healthcare: a qualitative interview study. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(3):313–23.

Commisceo Global Consulting Ltd. Pakistan-language, culture, customs and ettiquette; 2019. [Cited 2019 sep 25]. Available from https://commisceo-global.com/resources/country-guides/Pakistan-guide.

Attum B, Waheed A, Shamoon Z. Cultural competence in the care of muslim patients and their families. StatPearls: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Discussion group participants: Prof Nasim Chaudhry, Mrs. Afshan Qureshi, Mrs. Shela Minhas, Ms. Tayyeba Kiran, Ms. Ambreen Khan, Ms. Sehrish Tofique, Ms. Maryam Tahir, Ms. Munazzah Farooq, Mr. Ashfaq Ahmed, Mr. Rab Dino, Ms. Maria Usman, Mr. Nawaz Khan, Ms. Tahira Khalid, Ms. Sehrish Irshad, Ms. Rabia Sattar, Mr. Akhtar Zaman, Mr. M. Asif, Ms. Ayesha, Ms Imrana Imrana, Mr. Sanaullah, Ms. Shafaq Ejaz, Mr. Umair Ahsan, Ms. Zainab Bibi, Ms. Amna Noureen, Ms, Anum Naz, Ms. Uzma Omer, Ms. Farhatulain, Mr. Awais Khan, Mr. Suleman Shakoor, Ms. Muqaddas Asif, Ms. Maham Rasheed and Mr. Usman Arshad. PILL website: www.pill.org.pk/events-2 . For their support during the Yale Bioethics Summer School and for commenting on early drafts of the paper, we would also like to thank Lori Bruce, Director Sherwin B Nuland Institute of Bioethics, Yale University, USA, Dr Aron Rose and Mayli Mertens, Faculty members of Sherwin B Nuland Institute of Bioethics, Yale University, USA.

RM’s PhD thesis is funded by PILL, while the other authors are, in part, funded by MRC/DFID/NIHR, Youth Culturally adapted Manual Assisted Psychological therapy (Y-CMAP) for adolescent Pakistani patients with a recent history of self-harm. Grant number: MR/R022461/1 and from the Global Challenges Research Fund “South Asia Harm Reduction Movement-SAHAR M” (MR/P028144/1) SJLE is also funded by the UK NIHR UCL/UCLH Biomedical Research Centre and the EDCTP. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University College London, London, UK

Rakhshi Memon & Sarah J. L. Edwards

Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning (PILL), Karachi, Pakistan

Muqaddas Asif, Ameer B. Khoso, Sehrish Tofique, Tayyaba Kiran & Nasim Chaudhry

University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Nusrat Husain

Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist Lancashire & South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust, Preston, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Nasim Chaudhry

- , Afshan Qureshi

- , Shela Minhas

- , Tayyeba Kiran

- , Ambreen Khan

- , Sehrish Tofique

- , Maryam Tahir

- , Munazzah Farooq

- , Ashfaq Ahmed

- , Maria Usman

- , Nawaz Khan

- , Tahira Khalid

- , Sehrish Irshad

- , Rabia Sattar

- , Akhtar Zaman

- , Imrana Imrana

- , Sanaullah

- , Shafaq Ejaz

- , Umair Ahsan

- , Zainab Bibi

- , Amna Noureen

- , Uzma Omer

- , Farhatulain

- , Awais Khan

- , Suleman Shakoor

- , Muqaddas Asif

- , Maham Rasheed

- & Usman Arshad

Contributions

The paper was conceived by SE, drafted mainly by RM and MA on the basis of their analysis of the Group discussion, with input from AB, ST, TK, NC, and NH. RM submitted an early version of the paper as an assignment for the Yale Bioethics Summer School of 2019 and has a poster of it accepted for the 14th World Conference on Bioethics, Medical Ethics & Health Law in Portugal 2020 (Conference postponed until March 2022 due to Covid 19 pandemic). All authors read and approved the final version of the paper. The names of all discussants in the PILL Group are listed in the Acknowledgements and on the website www.pill.org.pk/events-2 . All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rakhshi Memon .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

As this was a discussion group therefore ethics approval was waived. All researchers participating in the discussion have given written consent and are acknowledged (see acknowledgements below).

Consent for publication

All participants gave their consent for direct quotes from their discussion to be published in this manuscript.

Competing interests

Additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Memon, R., Asif, M., Khoso, A.B. et al. Recognising values and engaging communities across cultures: towards developing a cultural protocol for researchers. BMC Med Ethics 22 , 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00608-4

Download citation

Received : 12 May 2020

Accepted : 28 March 2021

Published : 26 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00608-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community engagement

- Global health

- Low and middle income countries (LMIC)

- Cultural protocol

- Researchers from high income countries (HIC)

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Cultural and economic value: a critical review

- Original Article

- Published: 02 November 2018

- Volume 43 , pages 173–188, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Francesco Angelini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7903-964X 1 &

- Massimiliano Castellani 1 , 2

3829 Accesses

29 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

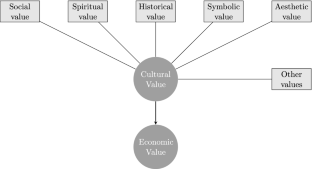

In this paper we present the state of the art concerning the distinction between economic and cultural value and the way the two values interact with each other. Our review espouses Klamer’s idea of creating a value-based approach in economics, systematizing the literature on the economic and cultural value of cultural goods. In order to analyze the relationship between the artist’s characteristics and the cultural goods’ values, we also propose a model of how fame and talent affect the economic and cultural value of cultural goods. In particular, the artist’s fame and talent and the cultural good’s price are included in the dynamic formation process of economic and cultural values.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Culinary Tourism as an Avenue for Tourism Development: Mapping the Flavors of the Philippines

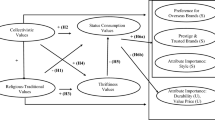

Unpacking collective materialism: how values shape consumption in seven Asian markets

Rajeev Batra, S. Arunachalam, … Michael S. W. Lee

When marketing strategy meets culture: the role of culture in product evaluations

Reo Song, Sangkil Moon, … Mark B. Houston

See also Klamer ( 2016a ).

For an analysis of the evaluation methods of the economic value of cultural goods, see Throsby ( 2001 ), Snowball ( 2008 ), and Gergaud and Ginsburgh ( 2017 ). A recent approach based on happiness and well-being of the art users has been developed by Hand ( 2018 ), Del Saz-Salazar et al. ( 2017 ), and Wheatley and Bickerton ( 2017 ).

See Throsby ( 2001 , pp. 28–29).

See also Snowball ( 2011 ).

See Klamer ( 2004 , pp. 147–150).

Another empirical investigation on the quality assessment is the one presented by Chossat and Gergaud ( 2003 ), which uses the experts official judgments to quantify the quality of gastronomy. Tobias ( 2004 ) uses the relationship between the experts opinion in the performing arts as a proxy for the quality and the economic variable, such as production costs.

The authors take the artwork “ Ballet français ” by Man Ray as an example, pointing out that one could extrapolate the artistic merit of the object and consider only its economic value linked to its value as a broom.

The importance of this value has been pointed out, later, also by Candela et al. ( 2009 ), studying the case of ethnic art, and by Radermecker et al. ( 2017 ), in an analysis of the influence of critics on market price.

See Bonus and Ronte ( 1997 ), Candela and Castellani ( 2000 ), Velthuis ( 2003 ), Candela and Scorcu ( 2004 ), McCain ( 2006 ), Hutter and Shusterman ( 2006 ), Hutter and Frey ( 2010 ), and Throsby and Zednik ( 2014 ), among the others.

The “social production of art” has been extensively studied in sociology, indeed, with focus on the importance of consensus on the value of cultural characteristics, on the difficulty in attaching value to a cultural good, and on the effect of the markets on the creation of cultural value. See, for example, Wolff ( 1981 ).

For an introduction of this topic, see Ginsburgh and Throsby ( 2014 ).

Besides price formation, also the construction of price indices is a widely studied topic in cultural economics. See, for example, Reitlinger ( 1963 , 1970 ), Anderson ( 1974 ), Goetzmann ( 1993 ), Pesando and Shum ( 1999 ), Ginsburgh and Jeanfils ( 1995 ), Frey and Pommerenhe ( 1989 ), Buelens and Ginsburgh ( 1993 ), Chanel ( 1995 ), Stein ( 1977 ), Candela and Scorcu ( 1997 ), Candela et al. ( 2004 ), Agnello and Pierce ( 1996 ), Flôres et al. ( 1999 ), Hellmanzik ( 2009 ), Scorcu and Zanola ( 2011 ), Kräussl et al. ( 2016 ), Angelini ( 2017 ), Vecco and Zanola ( 2017 ), and Assaf ( 2018 ).

See Adler ( 2006 ) for a review of stardom in economics literature.

For a recent survey on talent and its definitions, see Table 1 in Menger ( 2018 ).

Consider that the art-technical ability could depend also on the human capital accumulated by the artist throughout the art school years or the art training courses, in case she attended any (Towse 2006 ; Menger 2014 ).

A mathematical representation of the dynamic relationships between the variables in Fig. 2 is depicted in Appendix.

Adler, M. (1985). Stardom and talent. American Economic Review , 75 (1), 208–212.

Google Scholar

Adler, M. (2006). Stardom and talent. In V. A. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 895–906). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Agnello, R. J., & Pierce, R. K. (1996). Financial returns, price determinants, and genre effects in American art investment. Journal of Cultural Economics , 20 (4), 359–383.

Anderson, R. C. (1974). Paintings as an investment. Economic Inquiry , 12 (1), 13–26.

Angelini, F. (2017). Essays on the economics of the arts. Ph.D. thesis, IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca.

Angelini, F., & Castellani, M. Private pricing in the art market. Economics Bulletin (forthcoming) .

Angelini, F., & Castellani, M. (2018). Price and quality in the art market: a bargaining pricing model with asymmetric information . Mimeo.

Arora, P., & Vermeylen, F. (2013). The end of the art connoisseur? Experts and knowledge production in the visual arts in the digital age. Information, Communication and Society , 16 (2), 194–214.

Assaf, A. (2018). Testing for bubbles in the art markets: An empirical investigation. Economic Modelling , 68 , 340–355.

Ateca-Amestoy, V. (2007). Cultural capital and demand. Economics Bulletin , 26 (1), 1–9.

Baia Curioni, S., Forti, L., & Leone, L. (2015). Making visible. Artists and galleries in the global art system. In O. Velthuis & S. Baia Curioni (Eds.), Cosmopolitan canvases: The globalization of markets for contemporary art (pp. 55–77). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baumol, W. J., & Throsby, D. (2012). Psychic payoffs, overpriced assets, and underpaid superstars. Kyklos , 65 (3), 313–326.

Beckert, J., & Rössel, J. (2004). Art and prices. Reputation as a mechanism for reducing uncertainty in the art market. Kolner Zeitschrift fur Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie , 56 (1), 32–50.

Beckert, J., & Rössel, J. (2013). The price of art. European Societies , 15 (2), 178–195.

Benhamou, F., Moureau, N., & Sagot-Duvauroux, D. (2002). Opening the black box of the white cube: A survey of French contemporary art galleries at the turn of the millenium. Poetics , 30 (4), 263–280.

Blaug, M. (2001). Where are we now on cultural economics? Journal of Economic Surveys , 15 (2), 123–143.

Bonus, H., & Ronte, D. (1997). Credibility and economic value in the arts. Journal of Cultural Economics , 21 (2), 103–118.

Borghans, L., & Groot, L. (1999). Superstardom and monopolistic power: Why media stars earn more than their marginal contribution to welfare. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics , 154 (3), 546–571.

Bryson, A., Rossi, G., & Simmons, R. (2014). The migrant wage premium in professional football: A superstar effect? Kyklos , 67 (1), 12–28.

Buelens, N., & Ginsburgh, V. A. (1993). Revisiting Baumol’s art as floating crap game. European Economic Review , 37 (7), 1351–1371.

Cameron, S. (1995). On the role of critics in the culture industry. Journal of Cultural Economics , 19 (4), 321–331.

Candela, G., & Castellani, M. (2000). L’economia e l’arte. Economia Politica , 17 (3), 375–392.

Candela, G., Castellani, M., Pattitoni, P., & Di Lascio, F. M. (2016). On Rosen’s and Adler’s hypotheses in the modern and contemporary visual art market. Empirical Economics , 451 (1), 415–437.

Candela, G., Figini, P., & Scorcu, A. E. (2004). Price indices for artists: A proposal. Journal of Cultural Economics , 28 (4), 285–302.

Candela, G., Lorusso, S., & Matteucci, C. (2009). Information, documentation and certification in Western and ethnic art. Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage , 9 (1), 47–78.

Candela, G., & Scorcu, A. E. (1997). A price index for art market auctions. Journal of Cultural Economics , 21 (3), 175–196.

Candela, G., & Scorcu, A. E. (2004). Economia delle Arti . Bologna: Zanichelli.

Caves, R. E. (2003). Contracts between art and commerce. The Journal of Economic Perspectives , 17 (2), 73–84.

Champarnaud, L. (2014). Prices for superstars can flatten out. Journal of Cultural Economics , 38 (4), 369–384.

Chanel, O. (1995). Is art market behaviour predictable? European Economic Review , 39 (3–4), 519–527.

Chossat, V., & Gergaud, O. (2003). Expert opinion and gastronomy: The recipe for success. Journal of Cultural Economics , 27 (2), 127–141.

Chung, K. H., & Cox, R. A. K. (1994). A stochastic model of superstardom: An application of the Yule distribution. The Review of Economics and Statistics , 76 (4), 771–775.

Cox, R. A. K., & Felton, J. M. (1995). The concentration of commercial success in popular music: An analysis of the distribution of Gold records. Journal of Cultural Economics , 19 (4), 333–340.

Crain, W. M., & Tollison, R. D. (2002). Consumer choice and the popular music industry: A test of the superstar theory. Empirica , 29 (1), 1–9.

De Marchi, N. (2008). Confluence of value: Three historical moments. In M. Hutter & D. Throsby (Eds.), Beyond Price (pp. 200–219). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Dekker, E. (2014). Two approaches to study the value of art and culture, and the emergence of a third. Journal of Cultural Economics , 39 (4), 309–326.

Del Saz-Salazar, S., Navarrete-Tudela, A., Alcalá-Mellado, J. R., & Del Saz-Salazar, D. C. (2017). On the use of life satisfaction data for valuing cultural goods: A first attempt and a comparison with the Contingent Valuation Method. Journal of Happiness Studies . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9942-2 .

Ehrmann, T., Meiseberg, B., & Ritz, C. (2009). Superstar effects in deluxe gastronomy – An empirical analysis of value creation in German quality restaurants. Kyklos , 62 (4), 526–541.

Filimon, N., López-Sintas, J., & Padrós-Reig, C. (2011). A test of Rosen’s and Adler’s theories of superstars. Journal of Cultural Economics , 35 (2), 137–161.

Flôres, R. G. J., Ginsburgh, V. A., & Jeanfils, P. (1999). Long- and short-term portfolio choices of paintings. Journal of Cultural Economics , 23 (3), 191–208.

Fox, M. A., & Kochanowski, P. (2004). Models of superstardom: An application of the Lotka and Yule distributions. Popular Music and Society , 27 (4), 507–522.

Franck, E., & Nüesch, S. (2008). Mechanisms of superstar formation in German soccer: Empirical evidence. European Sport Management Quarterly , 8 (2), 145–164.

Franck, E., & Nüesch, S. (2012). Talent and/or popularity: What does it take to be a superstar? Economic Inquiry , 50 (1), 202–216.

Frey, B. S., & Pommerenhe, W. W. (1989). Muses and markets: Explorations in the economics of the arts . Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Gergaud, O., & Ginsburgh, V. A. (2017). Measuring the economic effects of events using Google Trends. In V. M. Ateca-Amestoy, V. A. Ginsburgh, I. Mazza, J. O’Hagan, & J. Prieto-Rodriguez (Eds.), Enhancing participation in the arts in the EU. Challenges and methods (pp. 337–353). Cham: Springer.

Ginsburgh, V. A. (2003). Awards, success and aesthetic quality in the arts. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 17 (2), 99–111.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Jeanfils, P. (1995). Long-term comovements in international markets for paintings. European Economic Review , 39 (3–4), 538–548.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & van Ours, J. C. (2003). Expert opinion and compensation: Evidence from a musical competition. American Economic Review , 93 (1), 289–296.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Throsby, D. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 2). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Weyers, S. (1999). On the perceived quality of movies. Journal of Cultural Economics , 23 (1), 269–283.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Weyers, S. (2006). Persistence and fashion in art Italian Renaissance from Vasari to Berenson and beyond. Poetics , 34 (1), 24–44.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Weyers, S. (2008). On the contemporaneousness of Roger de Piles’ Balance des Peintres. In J. Amariglio, J. W. Childers, & S. E. Cullenberg (Eds.), Sublime economy: On the intersection of art and economics (pp. 112–123). London: Routledge.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Weyers, S. (2008b). Quantitative approach to valuation in the arts, with an application to movies. In M. Hutter & D. Throsby (Eds.), Beyond price (pp. 179–199). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ginsburgh, V. A., & Weyers, S. (2010). On the formation of canons: The dynamics of narratives in art history. Empirical studies of the arts , 28 (1), 37–72.

Goetzmann, W. N. (1993). Accounting for taste: Art and financial market over three centuries. American Economic Review , 83 (5), 1370–1376.

Greenfeld, L. (1988). Professional ideologies and patterns of gatekeeping: Evaluation and judgment within two art worlds. Social Forces , 66 (4), 903–925.

Hamlen, W. A. J. (1991). Superstardom in popular music: Empirical evidence. The Review of Economics and Statistics , 73 (4), 729–733.

Hamlen, W. A. J. (1994). Variety and superstardom in popular music. Economic Inquiry , 32 (3), 395–406.

Hand, C. (2018). Do the arts make you happy? A quantile regression approach. Journal of Cultural Economics , 42 (2), 271–286.

Hellmanzik, C. (2009). Artistic styles: Revisiting the analysis of modern artists’ careers. Journal of Cultural Economics , 33 (3), 201–232.

Hernando, E., & Campo, S. (2017). An artist’s perceived value: Development of a measurement scale. International Journal of Arts Management , 19 (3), 33–47.

Humphreys, B. R., & Johnson, C. (2017). The effect of superstar players on game attendance: Evidence from the NBA. West Virginia University Working Paper no. 17–16 .

Hutter, M., & Frey, B. S. (2010). On the influence of cultural value on economic value. Revue d’économie politique , 120 (1), 35–46.

Hutter, M., Knebel, C., Pietzner, G., & Schäfer, M. (2007). Two games in town: A comparison of dealer and auction prices in contemporary visual arts markets. Journal of Cultural Economics , 31 (4), 247–261.

Hutter, M., & Shusterman, R. (2006). Value and the valuation of art in economic and aesthetic theory. In V. A. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 169–208). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Jansen, C. (2005). The performance of german motion pictures, profits and subsidies: Some empirical evidence. Journal of Cultural Economics , 29 (3), 191–212.

Kawashima, N. (1999). Distribution of the arts: British arts centres as gatekeepers’ in intersecting cultural production systems. Poetics , 26 (4), 263–283.

Klamer, A. (Ed.). (1996). The value of culture . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Klamer, A. (2004). Cultural goods are good for more than their economic value. In V. Rao & M. Walton (Eds.), Culture and public action (pp. 138–162). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Klamer, A. (2008). The lives of cultural goods. In J. Amariglio, J. W. Childers, & S. E. Cullenberg (Eds.), Sublime economy: On the intersection of art and economics (pp. 250–272). London: Routledge.

Klamer, A. (2016a). Doing the right thing: A value based economy . London: Ubiquity Press.

Klamer, A. (2016b). The value-based approach to cultural economics. Journal of Cultural Economics , 40 (4), 365–373.

Kräussl, R., Lehnert, T., & Martelin, N. (2016). Is there a bubble in the art market? Journal of Empirical Finance , 35 , 99–109.

Krueger, A. B. (2005). The economics of real superstars: The market for rock concerts in the material world. Journal of Labor Economics , 23 (1), 1–30.

Lang, G. E., & Lang, K. (1988). Recognition and renown: The survival of artistic reputation. American Journal of Sociology , 94 (1), 79–109.

Lehmann, E. E., & Schulze, G. G. (2008). What does it take to be a star? The role of performance and the media for German soccer players. Applied Economics Quarterly , 54 (1), 59–70.

Lévy-Garboua, L., & Montmarquette, C. (1996). A microeconometric study of theatre demand. Journal of Cultural Economics , 20 (1), 25–50.

Lucifora, C., & Simmons, R. (2003). Superstar effects in sport: Evidence from Italian soccer. Journal Of Sports Economics , 4 (1), 35–55.

MacDonald, G. M. (1988). The economics of rising stars. American Economic Review , 78 (1), 155–166.

McCain, R. A. (2006). Defining cultural and artistic goods. In V. A. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 147–167). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Menger, P. M. (2014). The economics of creativity . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Menger, P. M. (2018). Le talent et la physique sociale des inégalités. In P. M. Menger (Ed.), Le talent en débat . Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Muñiz Jr., A. M, Norris, T., & Fine, G. A. (2014). Marketing artistic careers: Pablo Picasso as brand manager. European Journal of Marketing , 48 (1/2), 68–88.

Oosterlinck, K., & Radermecker, A. S. (2018). “The Master of...”: Creating names for art history and the art market. Journal of Cultural Economics . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9329-1 .

Pesando, J. E., & Shum, P. M. (1999). The returns to Picasso’s prints and to traditional financial assets, 1977 to 1996. Journal of Cultural Economics , 23 (3), 183–192.

Peterson, K. (1997). The distribution and dynamics of uncertainty in art galleries: A case study of new dealerships in the Parisian art market, 1985–1990. Poetics , 25 (4), 241–263.

Pokorny, M., & Sedgwick, J. (2001). Stardom and the profitability of film making: Warner Bros. in the 1930s. Journal of Cultural Economics , 25 (3), 157–184

Preece, C., & Kerrigan, F. (2015). Multi-stakeholder brand narratives: An analysis of the construction of artistic brands. Journal of Marketing Management , 31 (11–12), 1207–1230.

Quemin, A., & van Hest, F. (2015). The impact of nationality and territory on fame and success in the visual arts sector: Artists, experts, and the market. In O. Velthuis & S. Baia Curioni (Eds.), Cosmopolitan canvases: The globalization of markets for contemporary art (pp. 170–192). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Radermecker, A. S., Ginsburgh, V., & Tommasi, D. (2017). The implicit value of arts experts: The case of Klaus Ertz and Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Working Papers ECARES 2017-17 , ULB - Universite Libre de Bruxelles.

Reinstein, D. A., & Snyder, C. M. (2005). The influence of expert reviews on consumer demand for experience goods: A case study of movie critics. The Journal of Industrial Economics , 53 (1), 27–51.

Reitlinger, G. (1963). The economics of taste: The rise and fall of the picture market, 1760–1963 . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Reitlinger, G. (1970). The economics of taste: The art market in the 1960s . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Rengers, M., & Velthuis, O. (2002). Determinants of prices for contemporary art in Dutch galleries, 1992–1998. Journal of Cultural Economics , 26 (1), 1–28.

Rosen, S. (1981). The economics of superstars. American Economic Review , 71 (5), 845–858.

Schönfeld, S., & Reinstaller, A. (2007). The effects of gallery and artist reputation on prices in the primary market for art: A note. Journal of Cultural Economics , 31 (2), 143–153.

Schroeder, J. E. (2005). The artist and the brand. European Journal of Marketing , 39 (11/12), 1291–1305.

Scorcu, A. E., & Zanola, R. (2011). The “right” price for art collectibles: A quantile hedonic regression investigation of Picasso paintings. Journal of Alternative Investments , 14 (2), 89–99.

Seaman, B. A. (2006). Empirical studies of demand for the performing arts. In V. A. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 415–472). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Smith, T. (2008). Creating value between cultures: Contemporary Australian aboriginal art. In M. Hutter & D. Throsby (Eds.), Beyond price (pp. 23–40). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Snowball, J. D. (2008). Measuring the value of culture . Berlin: Springer.

Snowball, J. D. (2011). Cultural value. In R. Towse (Ed.), A handbook of cultural economics (pp. 172–176). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Stein, J. P. (1977). The monetary appreciation of paintings. Journal of Political Economy , 85 (5), 1021–1036.

Teichgraeber III, R. F. (2008). More than Luther of these modern days: The construction of Emerson’s reputation in American culture, 1882–1903. In M. Hutter & D. Throsby (Eds.), Beyond price (pp. 159–175). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Throsby, D. (1990). Perception of quality in demand for the theatre. Journal of Cultural Economics , 14 (1), 65–82.

Throsby, D. (2001). Economics and culture . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Throsby, D. (2003). Determining the value of cultural goods: How much (or how little) does contingent valuation tell us? Journal of Cultural Economics , 27 (3–4), 275–285.

Throsby, D., & Zednik, A. (2014). The economic and cultural value of paintings: Some empirical evidence. In V. A. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 2, pp. 81–99). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Tobias, S. (2004). Quality in the performing arts: Aggregating and rationalizing expert opinion. Journal of Cultural Economics , 28 (2), 109–124.

Towse, R. (2006). Human capital and artists’ labour market. In V. A. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 865–894). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ursprung, H. W., & Wiermann, C. (2011). Reputation, price, and death: An empirical analysis of art price formation. Economic Inquiry , 49 (3), 697–715.

Van den Braembussche, A. (1996). The value of art: A philosophical perspective. In A. Klamer (Ed.), The value of culture (pp. 31–43). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Vecco, M., & Zanola, R. (2017). Don’t let the easy be the enemy of the good. Returns from art investments: What is wrong with it? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization , 140 , 120–129.

Velthuis, O. (2002). Promoters and parasites. An alternative explanation of price dispersion in the art market. In G. Mossetto & M. Vecco (Eds.), Economics of art auctions (pp. 130–150). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Velthuis, O. (2003). Symbolic meanings of prices: Constructing the value of contemporary art in Amsterdam and New York galleries. Theory and Society , 32 (2), 181–215.

Velthuis, O. (2007). Talking prices: Symbolic meanings of prices on the market for contemporary art . Princeton, MA: Princeton University Press.

Velthuis, O. (2011). Damien’s dangerous idea: Valuing contemporary art at auction. In J. Beckert & P. Aspers (Eds.), The worth of goods: Valuation and pricing in the economy (pp. 178–200). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Velthuis, O. (2012). The contemporary art market between stasis and flux. In M. Lind & O. Velthuis (Eds.), Contemporary art and its commercial markets (pp. 17–50). Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Vermeylen, F., van Dijck, M., & De Laet, V. (2013). The test of time: Art encyclopedia and the formation of the canon of seventeenth-century painters in the Low Countries. Empirical Studies of the Arts , 31 (1), 81–105

Wheatley, D., & Bickerton, C. (2017). Subjective well-being and engagement in arts, culture and sport. Journal of Cultural Economics , 41 (1), 23–45.

Wijnberg, N. M., & Gemser, G. (2000). Adding value to innovation: Impressionism and the transformation of the selection system in visual arts. Organization Science , 11 (3), 323–329.

Wolff, J. (1981). The social production of art . London: MacMillan Press.

Zakaras, L., & Lowell, J. F. (2008). Cultivating demand for the arts. Arts learning, arts engagement, and state arts policy . Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Zorloni, A. (2005). Structure of the contemporary art market and the profile of Italian artists. International Journal of Arts Management , 8 (1), 61–71.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Statistics, University of Bologna, Piazza Teatini, 10, Rimini, Italy

Francesco Angelini & Massimiliano Castellani

The Rimini Centre for Economic Analysis, Waterloo, On, Canada

Massimiliano Castellani

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Francesco Angelini .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

This study was not funded, and the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix: A mathematical model

The framework in Fig. 2 can be represented by using an analytical model, which would consider the dynamics of the variables and the relationships among them.

We define \(\tau\) and \(\phi\) , respectively, as the artist’s talent and fame, and CV , EV , and p , respectively, as the artwork’s cultural value, economic value, and price. Assuming a discrete timing, we can represent the framework described in our paper by using the following system of equations:

where t represents the current period of time.

Given the structure of equations of the model, the artwork’s cultural value in t is influenced by the artist’s talent, which has no subscript since it is time-invariant, and by the cultural value of all the periods before t (since the cultural value in \(t-1\) is influenced by the cultural value in \(t-2\) , and so on), because of both exchange and interaction between the individuals and critics’ assessment, as we have seen in Sect. 3 . The artwork’s cultural value in t affects the economic value in t , which is also influenced by the artist’s fame \(\phi\) in t . The artist’s fame in the current period is influenced both by the fame in all the previous periods, and by the price in \(t-1\) . Finally, price in t is influenced by the economic value in the same period.

The potential presence of exogenous shocks could be taken into account by letting the functional forms to be time-variant, for example by adding a random shock with a distribution to be chosen, possibly based on empirical observation. The variable which is most likely to be affected by exogenous shocks is the artist’s fame, since it could also change because of actions that she did not do. Also cultural value could be sensitive to exogenous shocks, since its components could change in value because of several reasons.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Angelini, F., Castellani, M. Cultural and economic value: a critical review. J Cult Econ 43 , 173–188 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9334-4

Download citation

Received : 09 January 2018

Accepted : 16 October 2018

Published : 02 November 2018

Issue Date : 01 June 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9334-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cultural good

- Cultural value

- Economic value

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Universality and Cultural Diversity in Moral Reasoning and Judgment

Many theories have shaped the concept of morality and its development by anchoring it in the realm of the social systems and values of each culture. This review discusses the current formulation of moral theories that attempt to explain cultural factors affecting moral judgment and reasoning. It aims to survey key criticisms that emerged in the past decades. In both cases, we highlight examples of cultural differences in morality, to show that there are cultural patterns of moral cognition in Westerners’ individualistic culture and Easterners’ collectivist culture. It suggests a paradigmatic change in this field by proposing pluralist “moralities” thought to be universal and rooted in the human evolutionary past. Notwithstanding, cultures vary substantially in their promotion and transmission of a multitude of moral reasonings and judgments. Depending on history, religious beliefs, social ecology, and institutional regulations (e.g., kinship structure and economic markets), each society develops a moral system emphasizing several moral orientations. This variability raises questions for normative theories of morality from a cross-cultural perspective. Consequently, we shed light on future descriptive work on morality to identify the cultural characteristics likely to impact the expression or development of reasoning, justification, argumentation, and moral judgment in Westerners’ individualistic culture and Easterners’ collectivist culture.

Introduction

Morality plays a fundamental role in the functioning of any human society by regulating social interactions and behaviors. The concept of morality denotes a set of values, implicit rules, principles, and long-standing, and shared cultural customs, drawn on the opposition between Good and Evil to guide social behavior ( Haidt, 2007 ). Morality often means having to make the decision “What should I do?” by linking mental states (emotions, reasoning, and desire) and the subsequent action(s). Moral principles thus define the guidelines as to what an individual should do, or is allowed to do, both toward others and themselves, and this is in relation to socially constructed beliefs ( Matsumoto and Juang, 2013 ). It is a common heritage that an individual acquires during their development, across different social environments. Consequently, morality is connected to culture. The notion of culture should be looked at according to the definition of Hong (2009) , who describes it as “a network of understanding, made up of opinion-based routines, of feelings and interactions with other people, as well as a body of affirmations and essential ideas on aspects of life.” The individual’s environment establishes shared cultural knowledge, which brings about affective, cognitive, and behavioral consequences on morality. This link leads us to ask ourselves: to what extent does culture impact upon human morality? More specifically, are there cultural patterns of moral cognition in Westerners’ individualistic culture and Easterners’ collectivist culture?

In this review, we are going to discuss the current formulation of moral theories that attempt to explain cultural factors affecting moral judgment and reasoning. The distinction will be to contrast the cognitive-developmental and the social interactional approaches to the later spectrum of approaches that address intercultural variation in moral judgment. We will present in detail cross-cultural studies on moral judgment, which will allow us to better understand universal and societal aspects of morality. Finally, we will consider cultural models of moral cognition by identifying specific moral justification and argumentation in Westerners’ individualistic culture and Easterners’ collectivist culture.

Going Beyond a Developmental Approach of Morality To Account For Intercultural Moral Variations

Numerous theories have shaped the concept of morality and its development by embedding it in the field of social systems and values of each culture.

The scientific psychological study of morality can primarily be traced to the influential moral constructivist theory of Piaget ( Piaget and Gabain, 1965 ; Piaget, 1985 ) and theory on the development of moral reasoning of Kohlberg (1976) . Those theories are shaped by a philosophic heritage, strengthened by a liberal and individualistic vision of morality, backed by the works of Kant (1765) , Mill (1863/2002) , and Rawls (1971) . For these authors, morality is universal as it is based on rationality which, by definition, is shared by individuals everywhere. Both Piaget and Kohlberg have developed stage theories that show different reasoning about moral issues depending on the level of moral development. Kohlberg (1976) developed his stage theory of moral development based on work of Piaget (1932) and he conceptualized three levels of moral development, and each level contains two substages. First, the pre-conventional stage precedes understanding and acceptance of social conventions. It refers to heteronomous morality, whereby the individual obeys the rules for fear of being punished. Second, the conventional stage refers to autonomous morality and represents conformity to expectations and conventions of society and authority. Finally, comes the post-conventional stage, in which the individual formulates and accepts general moral principles, which are implicit to the rules, and whereby the individual independently faces social approval. The stages and substages of Kohlberg’s theory of moral development are shown in Table 1 . The focal point of their research is to question whether the same stages of development can be found in all cultures ( Piaget, 1977 ; Kohlberg, 1981 ). A meta-analysis of 45 intercultural studies across 27 countries ( Snarey, 1985 ) examined the universal affirmation of Kohlberg’s theory. The hypothesis, according to which the development stages are invariable, was well supported when there was an accurate adaptation of the content and when the language of the interview matched that of the subject. The transversal and longitudinal results indicate the presence of the pre-conventional stage and the conventional stage in all of the studied cultures. Additionally, a more recent study ( Gibbs et al., 2007 ) compared 75 studies across 23 countries and suggests that the first two stages of Kohlberg’s theory are universal.

The stages and substages of Kohlberg’s theory of moral development.

A significant criticism concerning this theory was put forward by Bukatko and Daehler (2003) ; it fails to address the measuring of moral values specific to the cultures. Kohlberg is neither interested in the content of morality, nor in the specific values which emerge from it. His concern is rather in the structure of moral development, by looking at how thoughts and reasonings are transformed throughout the different stages. Nevertheless, understanding the values of each culture is necessary to apprehend the development of moral reasoning. For instance, the beliefs of the Afar people in Ethiopia valorize polygamy with shared spouses, which play an essential role in their society, whereas this practice is considered as a moral transgression in Western countries. Further still, people from Asian cultures react differently to moral dilemmas compared to those who come from Western cultures. Indeed, Asian societies focus more on maintaining a harmonious social order ( Dien Winfield, 1982 ). The development of moral reasoning theory does not account for these observations, while intercultural research shows that values and moral principles can influence moral structure.