- My Reading List

- Account Settings

- Newsletters & alerts

- Gift subscriptions

- Accessibility for screenreader

A pandemic year

How the pandemic is reshaping education

[ Parents and teachers: How are your kids handling school during the pandemic? ]

School by screen

Remote learning keeps going.

[ Do you have questions about how D.C.-area school systems are returning kids to the classroom? Ask The Post. ]

— Donna St. George

The great catch-up, schools set to attack lost learning.

[ 'A lost generation’: Surge of research reveals students sliding backward, most vulnerable worst affected ]

— Laura Meckler

When students struggle

More support for mental health.

[ Partly hidden by isolation, many of the nation’s schoolchildren struggle with mental health ]

— Donna St. George and Valerie Strauss

Teachers tested

Educators draw lessons from a challenging year.

[ Dispatches from education’s front lines: Teachers share their experiences as school returns during the pandemic ]

[ For locked-down high-schoolers, reading ‘The Plague’ is daunting, and then comforting ]

Connected at home

Laptops and hotspots likely to stick around.

[ A look back one year after the WHO declared the coronavirus a pandemic and changed how we live ]

D-plus school buildings

Pandemic spotlight offers real chance for reform, — hannah natanson, rethinking attendance, who attends, who is absent.

Funding schools

Changing the ‘butt-in-seats’ formula.

[ Answer Sheet: This is what inadequate funding at a public school looks and feels like — as told by an entire faculty ]

— Valerie Strauss

Wanted: new ways to assess students.

[ Answer Sheet: One month in, Biden angers supporters who wanted him to curb standardized testing ]

We noticed you’re blocking ads!

COVID-19 has fuelled a global ‘learning poverty’ crisis

The pandemic saw empty classrooms all across the world. Image: REUTERS/Marzio Toniolo

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joao Pedro Azevedo

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Before the pandemic, the world was already facing an education crisis.

- Last year, 53% of 10-year-old children in low- and middle-income countries either had failed to learn to read with comprehension or were out of school.

- COVID-19 has exacerbated learning gaps further, taking 1.6 billion students out of school at its peak.

- To mitigate the situation, parents, teachers, students, governments, and development partners must work together to remedy the crisis.

Even before COVID-19 forced a massive closure of schools around the globe, the world was in the middle of a learning crisis that threatened efforts to build human capital—the skills and know-how needed for the jobs of the future. More than half (53 percent) of 10-year-old children in low- and middle-income countries either had failed to learn to read with comprehension or were out of school entirely. This is what we at the World Bank call learning poverty . Recent improvements in Learning Poverty have been extremely slow. If trends of the last 15 years were to be extrapolated, it will take 50 years to halve learning poverty. Last year we proposed a target to cut Learning Poverty by at least half by 2030. This would require doubling or trebling the recent rate of improvement in learning, something difficult but achievable. But now COVID-19 is likely to deepen learning gaps and make this dramatically more difficult.

Have you read?

3 things we can do reverse the ‘covid slide’ in education, this indian state is a model of how to manage education during a pandemic, covid-19 is an opportunity to reset education. here are 4 ways how.

Temporary school closures in more than 180 countries have, at the peak of the pandemic, kept nearly 1.6 billion students out of school ; for about half of those students, school closures are exceeding 7 months. Although most countries have made heroic efforts to put remote and remedial learning strategies in place, learning losses are likely to happen. A recent survey of education officials on government responses to COVID-19 by UNICEF, UNESCO, and the World Bank shows that while countries and regions have responded in various ways, only half of the initiatives are monitoring usage of remote learning (Figure 1, top panel). Moreover, where usage is being monitored, the remote learning is being used by less than half of the student population (Figure 1, bottom panel), and most of those cases are online platforms in high- and middle-income countries.

COVID-19-related school closures are forcing countries even further off track from achieving their learning goals. Students currently in school stand to lose $10 trillion in labor earnings over their working lives. That is almost one-tenth of current global GDP, or half the United States’ annual economic output, or twice the global annual public expenditure on primary and secondary education.

In a recent brief I summarize the findings of three simulation scenarios to gauge potential impacts of the crisis on learning poverty. In the most pessimistic scenario, COVID-related school closures could increase the learning poverty rate in the low- and middle-income countries by 10 percentage points, from 53% to 63%. This 10-percentage-point increase in learning poverty implies that an additional 72 million primary-school-age children could fall into learning poverty , out of a population of 720 million children of primary-school age.

This result is driven by three main channels: school closures, effectiveness of mitigation and remediation, and the economic impact. School closures, and the effectiveness of mitigation and remediation, will affect the magnitude of the learning loss, while the economic impact will affect dropout rates. In these simulations, school closures are assumed to last for 70% of the school year, there will be no remediation, mitigation effectiveness will vary from 5%, 7% and 15% for low-, middle- or high-income countries, respectively. The economic channel builds on macro-economic growth projections , and estimates the possible impacts of economic contractions on household income, and the likelihood that these will affect primary school age-school-enrollment.

Most of the potential increase in learning poverty would take place in regions with a high but still average level of learning poverty in the global context pre-COVID, such as South Asia (which had a 63% pre-pandemic rate of learning poverty), Latin America (48%) , and East Asia and the Pacific (21%). In Sub-Saharan Africa and Low-income countries, where learning poverty was already at 87% and 90% before COVID, increases would be relatively small, at 4 percentage points and 2 percentage points, respectively. This reflects that most of the learning losses in those regions would impact students who were already failing to achieve the minimum reading proficiency level by the end of primary—that is, those who were already learning-poor.

To gauge at the impacts of the current crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and Northern Africa we need to examine other indicators of learning deprivation. In these two regions children are on average the furthest below the minimum proficiency level, with a Learning Deprivation Gap (the average distance of a learning deprived child to the minimum reading proficiency level) of approximately 20%. This rate is double the global average (10.5%), four times larger than the East Asia and Pacific Gap (5%), and more than tenfold larger the Europe and Central Asia average gap (1.3%). The magnitude of learning deprivation gap suggests that on average, students on those regions are one full academic year behind in terms of learning, or two times behind the global average.

In the most pessimistic scenario, COVID-19 school closures might increase the learning deprivation gap by approximately 2.5 percentage points in Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America. However, the same increase in the learning deprivation gap does not imply the same impact in qualitative terms. An indicator of the severity of learning deprivation, which captures the inequality among the learning deprived children, reveals that the severity of learning deprivation in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa could increase by approximately 1.5 percentage points, versus an increase of 0.5 percentage points in Latin America. This suggests that the new learning-deprived in Latin America would remain closer to the minimum proficiency level than children in Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa. As a consequence, the range of options required to identify students’ needs and provide learning opportunities, will be qualitatively different in these two groups of countries— more intense in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East than in Latin America.

In absolute terms, Sub-Sharan Africa and the Middle East and Northern Africa would remain the two regions with the largest number of learning-deprived children. The depth of learning deprivation in Sub-Saharan Africa will increase by three times more than the number of children who are learning-deprived. This is almost three times the global average, and four times more than in Europe and Central Asia. This suggests an increase in the complexity and the cost of tackling the learning crisis in the continent.

Going forward, as schools reopen , educational systems will need to be more flexible and adapt to the student’s needs. Countries will need to reimagine their educational systems and to use the opportunity presented by the pandemic and its triple shock—to health, the economy, and the educational system—to build back better . Several policy options deployed during the crisis, such as remote learning solutions, structured lesson plans, curriculum prioritization, and accelerated teaching programs (to name a few), can contribute to building an educational system that is more resilient to crisis, flexible in meeting student needs, and equitable in protecting the most vulnerable.

The results from these simulations are not destiny. Parents, teachers, students, governments, and development partners can work together to deploy effective mitigation and remediation strategies to protect the COVID-19 generation’s future. School reopening, when safe, is critical, but it is not enough. The simulation results show major differences in the potential impacts of the crisis on the learning poor across regions . The big challenge will be to rapidly identify and respond to each individual student’s learning needs flexibly and to build back educational systems more resilient to shocks, using technology effectively to enable learning both at school and at home.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on COVID-19 .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Winding down COVAX – lessons learnt from delivering 2 billion COVID-19 vaccinations to lower-income countries

Charlotte Edmond

January 8, 2024

Here’s what to know about the new COVID-19 Pirola variant

October 11, 2023

How the cost of living crisis affects young people around the world

Douglas Broom

August 8, 2023

From smallpox to COVID: the medical inventions that have seen off infectious diseases over the past century

Andrea Willige

May 11, 2023

COVID-19 is no longer a global health emergency. Here's what it means

Simon Nicholas Williams

May 9, 2023

New research shows the significant health harms of the pandemic

Philip Clarke, Jack Pollard and Mara Violato

April 17, 2023

Coronavirus and schools: Reflections on education one year into the pandemic

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, daphna bassok , daphna bassok nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @daphnabassok lauren bauer , lauren bauer fellow - economic studies , associate director - the hamilton project @laurenlbauer stephanie riegg cellini , stephanie riegg cellini nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy helen shwe hadani , helen shwe hadani former brookings expert @helenshadani michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies @drmikehansen douglas n. harris , douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99 brad olsen , brad olsen senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @bradolsen_dc richard v. reeves , richard v. reeves president - american institute for boys and men @richardvreeves jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies @jonvalant kenneth k. wong kenneth k. wong nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy.

March 12, 2021

- 11 min read

One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Reacting to the virus, schools at every level were sent scrambling. Institutions across the world switched to virtual learning, with teachers, students, and local leaders quickly adapting to an entirely new way of life. A year later, schools are beginning to reopen, the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill has been passed, and a sense of normalcy seems to finally be in view; in President Joe Biden’s speech last night, he spoke of “finding light in the darkness.” But it’s safe to say that COVID-19 will end up changing education forever, casting a critical light on everything from equity issues to ed tech to school financing.

Below, Brookings experts examine how the pandemic upended the education landscape in the past year, what it’s taught us about schooling, and where we go from here.

In the United States, we tend to focus on the educating roles of public schools, largely ignoring the ways in which schools provide free and essential care for children while their parents work. When COVID-19 shuttered in-person schooling, it eliminated this subsidized child care for many families. It created intense stress for working parents, especially for mothers who left the workforce at a high rate.

The pandemic also highlighted the arbitrary distinction we make between the care and education of elementary school children and children aged 0 to 5 . Despite parents having the same need for care, and children learning more in those earliest years than at any other point, public investments in early care and education are woefully insufficient. The child-care sector was hit so incredibly hard by COVID-19. The recent passage of the American Rescue Plan is a meaningful but long-overdue investment, but much more than a one-time infusion of funds is needed. Hopefully, the pandemic represents a turning point in how we invest in the care and education of young children—and, in turn, in families and society.

Congressional reauthorization of Pandemic EBT for this school year , its extension in the American Rescue Plan (including for summer months), and its place as a central plank in the Biden administration’s anti-hunger agenda is well-warranted and evidence based. But much more needs to be done to ramp up the program–even today , six months after its reauthorization, about half of states do not have a USDA-approved implementation plan.

In contrast, enrollment is up in for-profit and online colleges. The research repeatedly finds weaker student outcomes for these types of institutions relative to community colleges, and many students who enroll in them will be left with more debt than they can reasonably repay. The pandemic and recession have created significant challenges for students, affecting college choices and enrollment decisions in the near future. Ultimately, these short-term choices can have long-term consequences for lifetime earnings and debt that could impact this generation of COVID-19-era college students for years to come.

Many U.S. educationalists are drawing on the “build back better” refrain and calling for the current crisis to be leveraged as a unique opportunity for educators, parents, and policymakers to fully reimagine education systems that are designed for the 21st rather than the 20th century, as we highlight in a recent Brookings report on education reform . An overwhelming body of evidence points to play as the best way to equip children with a broad set of flexible competencies and support their socioemotional development. A recent article in The Atlantic shared parent anecdotes of children playing games like “CoronaBall” and “Social-distance” tag, proving that play permeates children’s lives—even in a pandemic.

Tests play a critical role in our school system. Policymakers and the public rely on results to measure school performance and reveal whether all students are equally served. But testing has also attracted an inordinate share of criticism, alleging that test pressures undermine teacher autonomy and stress students. Much of this criticism will wither away with different formats. The current form of standardized testing—annual, paper-based, multiple-choice tests administered over the course of a week of school—is outdated. With widespread student access to computers (now possible due to the pandemic), states can test students more frequently, but in smaller time blocks that render the experience nearly invisible. Computer adaptive testing can match paper’s reliability and provides a shorter feedback loop to boot. No better time than the present to make this overdue change.

A third push for change will come from the outside in. COVID-19 has reminded us not only of how integral schools are, but how intertwined they are with the rest of society. This means that upcoming schooling changes will also be driven by the effects of COVID-19 on the world around us. In particular, parents will be working more from home, using the same online tools that students can use to learn remotely. This doesn’t mean a mass push for homeschooling, but it probably does mean that hybrid learning is here to stay.

I am hoping we will use this forced rupture in the fabric of schooling to jettison ineffective aspects of education, more fully embrace what we know works, and be bold enough to look for new solutions to the educational problems COVID-19 has illuminated.

There is already a large gender gap in education in the U.S., including in high school graduation rates , and increasingly in college-going and college completion. While the pandemic appears to be hurting women more than men in the labor market, the opposite seems to be true in education.

Looking through a policy lens, though, I’m struck by the timing and what that timing might mean for the future of education. Before the pandemic, enthusiasm for the education reforms that had defined the last few decades—choice and accountability—had waned. It felt like a period between reform eras, with the era to come still very unclear. Then COVID-19 hit, and it coincided with a national reckoning on racial injustice and a wake-up call about the fragility of our democracy. I think it’s helped us all see how connected the work of schools is with so much else in American life.

We’re in a moment when our long-lasting challenges have been laid bare, new challenges have emerged, educators and parents are seeing and experimenting with things for the first time, and the political environment has changed (with, for example, a new administration and changing attitudes on federal spending). I still don’t know where K-12 education is headed, but there’s no doubt that a pivot is underway.

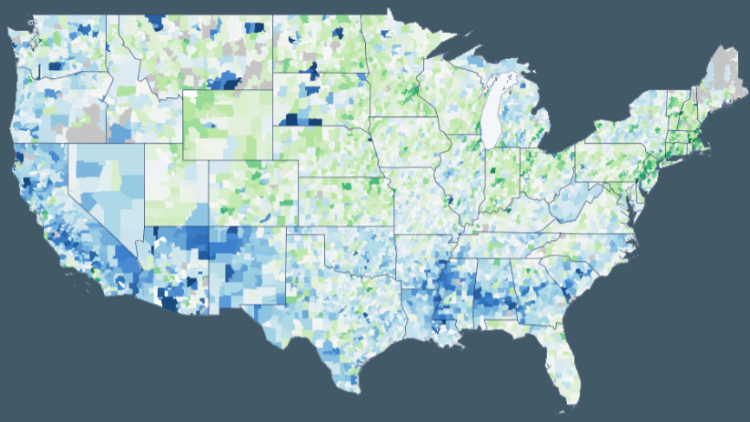

- First, state and local leaders must leverage commitment and shared goals on equitable learning opportunities to support student success for all.

- Second, align and use federal, state, and local resources to implement high-leverage strategies that have proven to accelerate learning for diverse learners and disrupt the correlation between zip code and academic outcomes.

- Third, student-centered priority will require transformative leadership to dismantle the one-size-fits-all delivery rule and institute incentive-based practices for strong performance at all levels.

- Fourth, the reconfigured system will need to activate public and parental engagement to strengthen its civic and social capacity.

- Finally, public education can no longer remain insulated from other policy sectors, especially public health, community development, and social work.

These efforts will strengthen the capacity and prepare our education system for the next crisis—whatever it may be.

Higher Education K-12 Education

Brookings Metro Economic Studies Global Economy and Development Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy Center for Universal Education

Brad Olsen, John McIntosh

April 3, 2024

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Jennifer B. Ayscue, Kfir Mordechay, David Mickey-Pabello

March 26, 2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 30 January 2023

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Bastian A. Betthäuser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4544-4073 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Anders M. Bach-Mortensen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7804-7958 2 &

- Per Engzell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2404-6308 3 , 4 , 5

Nature Human Behaviour volume 7 , pages 375–385 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

69k Accesses

104 Citations

1960 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social policy

To what extent has the learning progress of school-aged children slowed down during the COVID-19 pandemic? A growing number of studies address this question, but findings vary depending on context. Here we conduct a pre-registered systematic review, quality appraisal and meta-analysis of 42 studies across 15 countries to assess the magnitude of learning deficits during the pandemic. We find a substantial overall learning deficit (Cohen’s d = −0.14, 95% confidence interval −0.17 to −0.10), which arose early in the pandemic and persists over time. Learning deficits are particularly large among children from low socio-economic backgrounds. They are also larger in maths than in reading and in middle-income countries relative to high-income countries. There is a lack of evidence on learning progress during the pandemic in low-income countries. Future research should address this evidence gap and avoid the common risks of bias that we identify.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Aymee Alvarez-Rivero, Candice Odgers & Daniel Ansari

A methodological perspective on learning in the developing brain

Anna C. K. van Duijvenvoorde, Lucy B. Whitmore, … Kathryn L. Mills

Measuring and forecasting progress in education: what about early childhood?

Linda M. Richter, Jere R. Behrman, … Hirokazu Yoshikawa

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to one of the largest disruptions to learning in history. To a large extent, this is due to school closures, which are estimated to have affected 95% of the world’s student population 1 . But even when face-to-face teaching resumed, instruction has often been compromised by hybrid teaching, and by children or teachers having to quarantine and miss classes. The effect of limited face-to-face instruction is compounded by the pandemic’s consequences for children’s out-of-school learning environment, as well as their mental and physical health. Lockdowns have restricted children’s movement and their ability to play, meet other children and engage in extra-curricular activities. Children’s wellbeing and family relationships have also suffered due to economic uncertainties and conflicting demands of work, care and learning. These negative consequences can be expected to be most pronounced for children from low socio-economic family backgrounds, exacerbating pre-existing educational inequalities.

It is critical to understand the extent to which learning progress has changed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use the term ‘learning deficit’ to encompass both a delay in expected learning progress, as well as a loss of skills and knowledge already gained. The COVID-19 learning deficit is likely to affect children’s life chances through their education and labour market prospects. At the societal level, it can have important implications for growth, prosperity and social cohesion. As policy-makers across the world are seeking to limit further learning deficits and to devise policies to recover learning deficits that have already been incurred, assessing the current state of learning is crucial. A careful assessment of the COVID-19 learning deficit is also necessary to weigh the true costs and benefits of school closures.

A number of narrative reviews have sought to summarize the emerging research on COVID-19 and learning, mostly focusing on learning progress relatively early in the pandemic 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Moreover, two reviews harmonized and synthesized existing estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic 7 , 8 . In line with the narrative reviews, these two reviews find a substantial reduction in learning progress during the pandemic. However, this finding is based on a relatively small number of studies (18 and 10 studies, respectively). The limited evidence that was available at the time these reviews were conducted also precluded them from meta-analysing variation in the magnitude of learning deficits over time and across subjects, different groups of students or country contexts.

In this Article, we conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits 2.5 years into the pandemic. Our primary pre-registered research question was ‘What is the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning progress amongst school-age children?’, and we address this question using evidence from studies examining changes in learning outcomes during the pandemic. Our second pre-registered research aim was ‘To examine whether the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning differs across different social background groups, age groups, boys and girls, learning areas or subjects, national contexts’.

We contribute to the existing research in two ways. First, we describe and appraise the up-to-date body of evidence, including its geographic reach and quality. More specifically, we ask the following questions: (1) what is the state of the evidence, in terms of the available peer-reviewed research and grey literature, on learning progress of school-aged children during the COVID-19 pandemic?, (2) which countries are represented in the available evidence? and (3) what is the quality of the existing evidence?

Our second contribution is to harmonize, synthesize and meta-analyse the existing evidence, with special attention to variation across different subpopulations and country contexts. On the basis of the identified studies, we ask (4) to what extent has the learning progress of school-aged children changed since the onset of the pandemic?, (5) how has the magnitude of the learning deficit (if any) evolved since the beginning of the pandemic?, (6) to what extent has the pandemic reinforced inequalities between children from different socio-economic backgrounds?, (7) are there differences in the magnitude of learning deficits between subject domains (maths and reading) and between age groups (primary and secondary students)? and (8) to what extent does the magnitude of learning deficits vary across national contexts?

Below, we report our answers to each of these questions in turn. The questions correspond to the analysis plan set out in our pre-registered protocol ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021249944 ), but we have adjusted the order and wording to aid readability. We had planned to examine gender differences in learning progress during the pandemic, but found there to be insufficient evidence to conduct this subgroup analysis, as the large majority of the identified studies do not provide evidence on learning deficits separately by gender. We also planned to examine how the magnitude of learning deficits differs across groups of students with varying exposures to school closures. This was not possible as the available data on school closures lack sufficient depth with respect to variation of school closures within countries, across grade levels and with respect to different modes of instruction, to meaningfully examine this association.

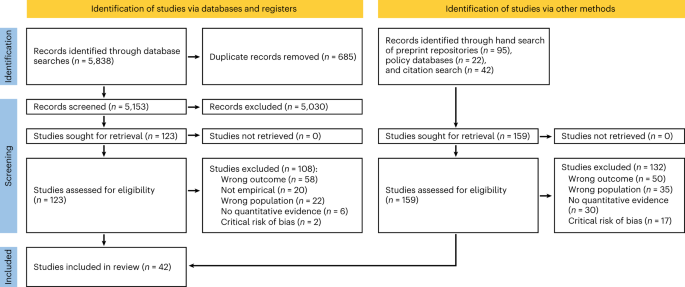

The state of the evidence

Our systematic review identified 42 studies on learning progress during the COVID-19 pandemic that met our inclusion criteria. To be included in our systematic review and meta-analysis, studies had to use a measure of learning that can be standardized (using Cohen’s d ) and base their estimates on empirical data collected since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (rather than making projections based on pre-COVID-19 data). As shown in Fig. 1 , the initial literature search resulted in 5,153 hits after removal of duplicates. All studies were double screened by the first two authors. The formal database search process identified 15 eligible studies. We also hand searched relevant preprint repositories and policy databases. Further, to ensure that our study selection was as up to date as possible, we conducted two full forward and backward citation searches of all included studies on 15 February 2022, and on 8 August 2022. The citation and preprint hand searches allowed us to identify 27 additional eligible studies, resulting in a total of 42 studies. Most of these studies were published after the initial database search, which illustrates that the body of evidence continues to expand. Most studies provide multiple estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits, separately for maths and reading and for different school grades. The number of estimates ( n = 291) is therefore larger than the number of included studies ( n = 42).

Flow diagram of the study identification and selection process, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The geographic reach of evidence is limited

Table 1 presents all included studies and estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits (in brackets), grouped by the 15 countries represented: Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the United States. About half of the estimates ( n = 149) are from the United States, 58 are from the UK, a further 70 are from other European countries and the remaining 14 estimates are from Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. As this list shows, there is a strong over-representation of studies from high-income countries, a dearth of studies from middle-income countries and no studies from low-income countries. This skewed representation should be kept in mind when interpreting our synthesis of the existing evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits.

The quality of evidence is mixed

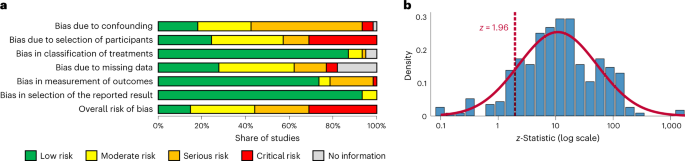

We assessed the quality of the evidence using an adapted version of the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool 9 . More specifically, we analysed the risk of bias of each estimate from confounding, sample selection, classification of treatments, missing data, the measurement of outcomes and the selection of reported results. A.M.B.-M. and B.A.B. performed the risk-of-bias assessments, which were independently checked by the respective other author. We then assigned each study an overall risk-of-bias rating (low, moderate, serious or critical) based on the estimate and domain with the highest risk of bias.

Figure 2a shows the distribution of all studies of COVID-19 learning deficits according to their risk-of-bias rating separately for each domain (top six rows), as well as the distribution of studies according to their overall risk of bias rating (bottom row). The overall risk of bias was considered ‘low’ for 15% of studies, ‘moderate’ for 30% of studies, ‘serious’ for 25% of studies and ‘critical’ for 30% of studies.

a , Domain-specific and overall distribution of studies of COVID-19 learning deficits by risk of bias rating using ROBINS-I, including studies rated to be at critical risk of bias ( n = 19 out of a total of n = 61 studies shown in this figure). In line with ROBINS-I guidance, studies rated to be at critical risk of bias were excluded from all analyses and other figures in this article and in the Supplementary Information (including b ). b , z curve: distribution of the z scores of all estimates included in the meta-analysis ( n = 291) to test for publication bias. The dotted line indicates z = 1.96 ( P = 0.050), the conventional threshold for statistical significance. The overlaid curve shows a normal distribution. The absence of a spike in the distribution of the z scores just above the threshold for statistical significance and the absence of a slump just below it indicate the absence of evidence for publication bias.

In line with ROBINS-I guidance, we excluded studies rated to be at critical risk of bias ( n = 19) from all of our analyses and figures, except for Fig. 2a , which visualizes the distribution of studies according to their risk of bias 9 . These are thus not part of the 42 studies included in our meta-analysis. Supplementary Table 2 provides an overview of these studies as well as the main potential sources of risk of bias. Moreover, in Supplementary Figs. 3 – 6 , we replicate all our results excluding studies deemed to be at serious risk of bias.

As shown in Fig. 2a , common sources of potential bias were confounding, sample selection and missing data. Studies rated at risk of confounding typically compared only two timepoints, without accounting for longer time trends in learning progress. The main causes of selection bias were the use of convenience samples and insufficient consideration of self-selection by schools or students. Several studies found evidence of selection bias, often with students from a low socio-economic background or schools in deprived areas being under-represented after (as compared with before) the pandemic, but this was not always adjusted for. Some studies also reported a higher amount of missing data post-pandemic, again generally without adjustment, and several studies did not report any information on missing data. For an overview of the risk-of-bias ratings for each domain of each study, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 .

No evidence of publication bias

Publication bias can occur if authors self-censor to conform to theoretical expectations, or if journals favour statistically significant results. To mitigate this concern, we include not only published papers, but also preprints, working papers and policy reports.

Moreover, Fig. 2b tests for publication bias by showing the distribution of z -statistics for the effect size estimates of all identified studies. The dotted line indicates z = 1.96 ( P = 0.050), the conventional threshold for statistical significance. The overlaid curve shows a normal distribution. If there was publication bias, we would expect a spike just above the threshold, and a slump just below it. There is no indication of this. Moreover, we do not find a left-skewed distribution of P values (see P curve in Supplementary Fig. 2a ), or an association between estimates of learning deficits and their standard errors (see funnel plot in Supplementary Fig. 2b ) that would suggest publication bias. Publication bias thus does not appear to be a major concern.

Having assessed the quality of the existing evidence, we now present the substantive results of our meta-analysis, focusing on the magnitude of COVID-19 learning deficits and on the variation in learning deficits over time, across different groups of students, and across country contexts.

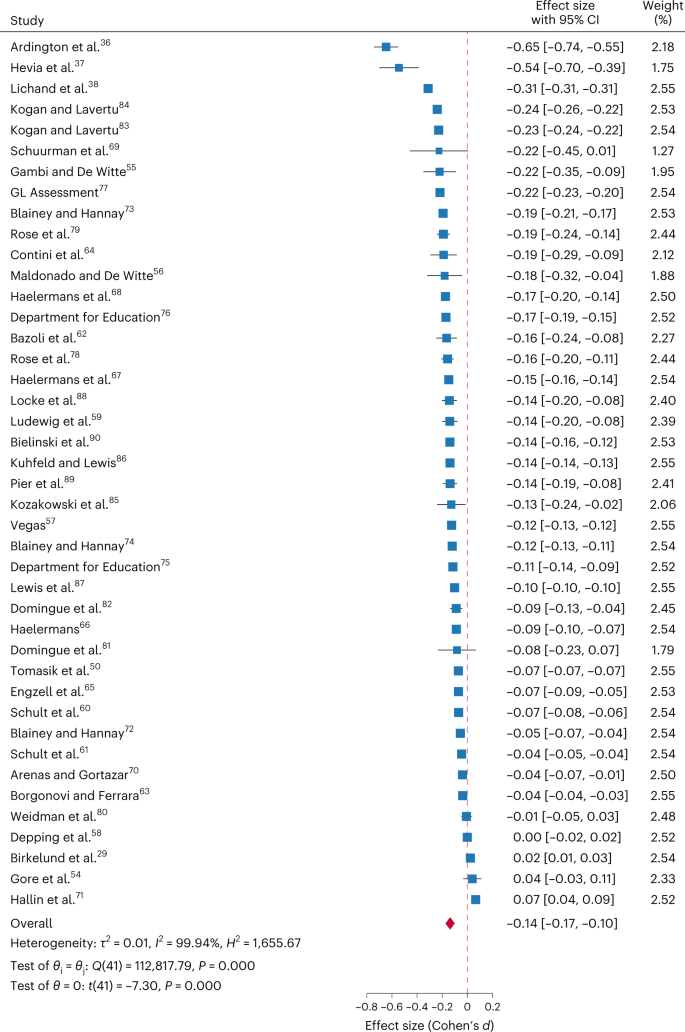

Learning progress slowed substantially during the pandemic

Figure 3 shows the effect sizes that we extracted from each study (averaged across grades and learning subject) as well as the pooled effect size (red diamond). Effects are expressed in standard deviations, using Cohen’s d . Estimates are pooled using inverse variance weights. The pooled effect size across all studies is d = −0.14, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.000, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.17 to −0.10. Under normal circumstances, students generally improve their performance by around 0.4 standard deviations per school year 10 , 11 , 12 . Thus, the overall effect of d = −0.14 suggests that students lost out on 0.14/0.4, or about 35%, of a school year’s worth of learning. On average, the learning progress of school-aged children has slowed substantially during the pandemic.

Effect sizes are expressed in standard deviations, using Cohen’s d , with 95% CI, and are sorted by magnitude.

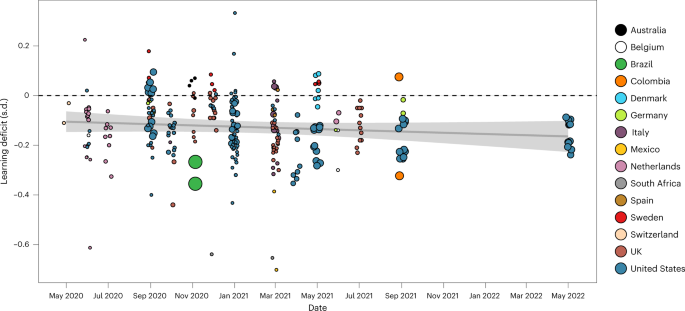

Learning deficits arose early in the pandemic and persist

One may expect that children were able to recover learning that was lost early in the pandemic, after teachers and families had time to adjust to the new learning conditions and after structures for online learning and for recovering early learning deficits were set up. However, existing research on teacher strikes in Belgium 13 and Argentina 14 , shortened school years in Germany 15 and disruptions to education during World War II 16 suggests that learning deficits are difficult to compensate and tend to persist in the long run.

Figure 4 plots the magnitude of estimated learning deficits (on the vertical axis) by the date of measurement (on the horizontal axis). The colour of the circles reflects the relevant country, the size of the circles indicates the sample size for a given estimate and the line displays a linear trend. The figure suggests that learning deficits opened up early in the pandemic and have neither closed nor substantially widened since then. We find no evidence that the slope coefficient is different from zero ( β months = −0.00, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.097, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.00). This implies that efforts by children, parents, teachers and policy-makers to adjust to the changed circumstance have been successful in preventing further learning deficits but so far have been unable to reverse them. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8 , the pattern of persistent learning deficits also emerges within each of the three countries for which we have a relatively large number of estimates at different timepoints: the United States, the UK and the Netherlands. However, it is important to note that estimates of learning deficits are based on distinct samples of students. Future research should continue to follow the learning progress of cohorts of students in different countries to reveal how learning deficits of these cohorts have developed and continue to develop since the onset of the pandemic.

The horizontal axis displays the date on which learning progress was measured. The vertical axis displays estimated learning deficits, expressed in standard deviation (s.d.) using Cohen’s d . The colour of the circles reflects the respective country, the size of the circles indicates the sample size for a given estimate and the line displays a linear trend with a 95% CI. The trend line is estimated as a linear regression using ordinary least squares, with standard errors clustered at the study level ( n = 42 clusters). β months = −0.00, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.097, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.00.

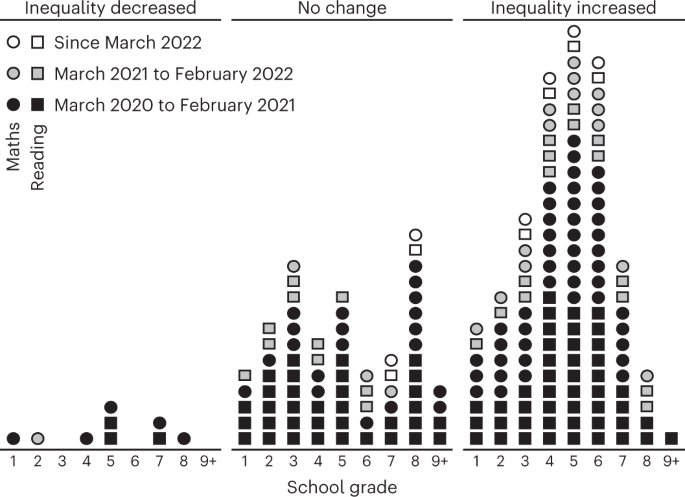

Socio-economic inequality in education increased

Existing research on the development of learning gaps during summer vacations 17 , 18 , disruptions to schooling during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone and Guinea 19 , and the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan 20 shows that the suspension of face-to-face teaching can increase educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds. Learning deficits during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to have been particularly pronounced for children from low socio-economic backgrounds. These children have been more affected by school closures than children from more advantaged backgrounds 21 . Moreover, they are likely to be disadvantaged with respect to their access and ability to use digital learning technology, the quality of their home learning environment, the learning support they receive from teachers and parents, and their ability to study autonomously 22 , 23 , 24 .

Most studies we identify examine changes in socio-economic inequality during the pandemic, attesting to the importance of the issue. As studies use different measures of socio-economic background (for example, parental income, parental education, free school meal eligibility or neighbourhood disadvantage), pooling the estimates is not possible. Instead, we code all estimates according to whether they indicate a reduction, no change or an increase in learning inequality during the pandemic. Figure 5 displays this information. Estimates that indicate an increase in inequality are shown on the right, those that indicate a decrease on the left and those that suggest no change in the middle. Squares represent estimates of changes in inequality during the pandemic in reading performance, and circles represent estimates of changes in inequality in maths performance. The shading represents when in the pandemic educational inequality was measured, differentiating between the first, second and third year of the pandemic. Estimates are also arranged horizontally by grade level. A large majority of estimates indicate an increase in educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds. This holds for both maths and reading, across primary and secondary education, at each stage of the pandemic, and independently of how socio-economic background is measured.

Each circle/square refers to one estimate of over-time change in inequality in maths/reading performance ( n = 211). Estimates that find a decrease/no change/increase in inequality are grouped on the left/middle/right. Within these categories, estimates are ordered horizontally by school grade. The shading indicates when in the pandemic a given measure was taken.

Learning deficits are larger in maths than in reading

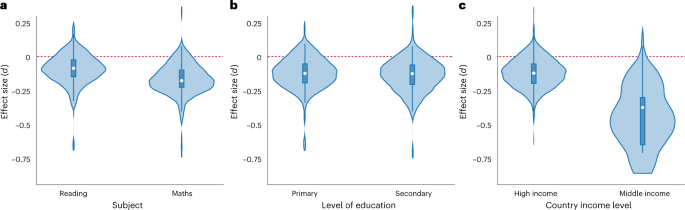

Available research on summer learning deficits 17 , 25 , student absenteeism 26 , 27 and extreme weather events 28 suggests that learning progress in mathematics is more dependent on formal instruction than in reading. This might be due to parents being better equipped to help their children with reading, and children advancing their reading skills (but not their maths skills) when reading for enjoyment outside of school. Figure 6a shows that, similarly to earlier disruptions to learning, the estimated learning deficits during the COVID-19 pandemic are larger for maths than for reading (mean difference δ = −0.07, t (41) = −4.02, two-tailed P = 0.000, 95% CI −0.11 to −0.04). This difference is statistically significant and robust to dropping estimates from individual countries (Supplementary Fig. 9 ).

Each plot shows the distribution of COVID-19 learning deficit estimates for the respective subgroup, with the box marking the interquartile range and the white circle denoting the median. Whiskers mark upper and lower adjacent values: the furthest observation within 1.5 interquartile range of either side of the box. a , Learning subject (reading versus maths). Median: reading −0.09, maths −0.18. Interquartile range: reading −0.15 to −0.02, maths −0.23 to −0.09. b , Level of education (primary versus secondary). Median: primary −0.12, secondary −0.12. Interquartile range: primary −0.19 to −0.05, secondary −0.21 to −0.06. c , Country income level (high versus middle). Median: high −0.12, middle −0.37. Interquartile range: high −0.20 to −0.05, middle −0.65 to −0.30.

No evidence of variation across grade levels

One may expect learning deficits to be smaller for older than for younger children, as older children may be more autonomous in their learning and better able to cope with a sudden change in their learning environment. However, older students were subject to longer school closures in some countries, such as Denmark 29 , based partly on the assumption that they would be better able to learn from home. This may have offset any advantage that older children would otherwise have had in learning remotely.

Figure 6b shows the distribution of estimates of learning deficits for students at the primary and secondary level, respectively. Our analysis yields no evidence of variation in learning deficits across grade levels (mean difference δ = −0.01, t (41) = −0.59, two-tailed P = 0.556, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.03). Due to the limited number of available estimates of learning deficits, we cannot be certain about whether learning deficits differ between primary and secondary students or not.

Learning deficits are larger in poorer countries

Low- and middle-income countries were already struggling with a learning crisis before the pandemic. Despite large expansions of the proportion of children in school, children in low- and middle-income countries still perform poorly by international standards, and inequality in learning remains high 30 , 31 , 32 . The pandemic is likely to deepen this learning crisis and to undo past progress. Schools in low- and middle-income countries have not only been closed for longer, but have also had fewer resources to facilitate remote learning 33 , 34 . Moreover, the economic resources, availability of digital learning equipment and ability of children, parents, teachers and governments to support learning from home are likely to be lower in low- and middle-income countries 35 .

As discussed above, most evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits comes from high-income countries. We found no studies on low-income countries that met our inclusion criteria, and evidence from middle-income countries is limited to Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. Figure 6c groups the estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits in these four middle-income countries together (on the right) and compares them with estimates from high-income countries (on the left). The learning deficit is appreciably larger in middle-income countries than in high-income countries (mean difference δ = −0.29, t (41) = −2.78, two-tailed P = 0.008, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.08). In fact, the three largest estimates of learning deficits in our sample are from middle-income countries (Fig. 3 ) 36 , 37 , 38 .

Two years since the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a growing number of studies examining the learning progress of school-aged children during the pandemic. This paper first systematically reviews the existing literature on learning progress of school-aged children during the pandemic and appraises its geographic reach and quality. Second, it harmonizes, synthesizes and meta-analyses the existing evidence to examine the extent to which learning progress has changed since the onset of the pandemic, and how it varies across different groups of students and across country contexts.

Our meta-analysis suggests that learning progress has slowed substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pooled effect size of d = −0.14, implies that students lost out on about 35% of a normal school year’s worth of learning. This confirms initial concerns that substantial learning deficits would arise during the pandemic 10 , 39 , 40 . But our results also suggest that fears of an accumulation of learning deficits as the pandemic continues have not materialized 41 , 42 . On average, learning deficits emerged early in the pandemic and have neither closed nor widened substantially. Future research should continue to follow the learning progress of cohorts of students in different countries to reveal how learning deficits of these cohorts have developed and continue to develop since the onset of the pandemic.

Most studies that we identify find that learning deficits have been largest for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. This holds across different timepoints during the pandemic, countries, grade levels and learning subjects, and independently of how socio-economic background is measured. It suggests that the pandemic has exacerbated educational inequalities between children from different socio-economic backgrounds, which were already large before the pandemic 43 , 44 . Policy initiatives to compensate learning deficits need to prioritize support for children from low socio-economic backgrounds in order to allow them to recover the learning they lost during the pandemic.

There is a need for future research to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender inequality in education. So far, there is very little evidence on this issue. The large majority of the studies that we identify do not examine learning deficits separately by gender.

Comparing estimates of learning deficits across subjects, we find that learning deficits tend to be larger in maths than in reading. As noted above, this may be due to the fact that parents and children have been in a better position to compensate school-based learning in reading by reading at home. Accordingly, there are grounds for policy initiatives to prioritize the compensation of learning deficits in maths and other science subjects.

A limitation of this study and the existing body of evidence on learning progress during the COVID-19 pandemic is that the existing studies primarily focus on high-income countries, while there is a dearth of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. This is particularly concerning because the small number of existing studies from middle-income countries suggest that learning deficits have been particularly severe in these countries. Learning deficits are likely to be even larger in low-income countries, considering that these countries already faced a learning crisis before the pandemic, generally implemented longer school closures, and were under-resourced and ill-equipped to facilitate remote learning 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 45 . It is critical that this evidence gap on low- and middle-income countries is addressed swiftly, and that the infrastructure to collect and share data on educational performance in middle- and low-income countries is strengthened. Collecting and making available these data is a key prerequisite for fully understanding how learning progress and related outcomes have changed since the onset of the pandemic 46 .

A further limitation is that about half of the studies that we identify are rated as having a serious or critical risk of bias. We seek to limit the risk of bias in our results by excluding all studies rated to be at critical risk of bias from all of our analyses. Moreover, in Supplementary Figs. 3 – 6 , we show that our results are robust to further excluding studies deemed to be at serious risk of bias. Future studies should minimize risk of bias in estimating learning deficits by employing research designs that appropriately account for common sources of bias. These include a lack of accounting for secular time trends, non-representative samples and imbalances between treatment and comparison groups.

The persistence of learning deficits two and a half years into the pandemic highlights the need for well-designed, well-resourced and decisive policy initiatives to recover learning deficits. Policy-makers, schools and families will need to identify and realize opportunities to complement and expand on regular school-based learning. Experimental evidence from low- and middle-income countries suggests that even relatively low-tech and low-cost learning interventions can have substantial, positive effects on students’ learning progress in the context of remote learning. For example, sending SMS messages with numeracy problems accompanied by short phone calls was found to lead to substantial learning gains in numeracy in Botswana 47 . Sending motivational text messages successfully limited learning losses in maths and Portuguese in Brazil 48 .

More evidence is needed to assess the effectiveness of other interventions for limiting or recovering learning deficits. Potential avenues include the use of the often extensive summer holidays to offer summer schools and learning camps, extending school days and school weeks, and organizing and scaling up tutoring programmes. Further potential lies in developing, advertising and providing access to learning apps, online learning platforms or educational TV programmes that are free at the point of use. Many countries have already begun investing substantial resources to capitalize on some of these opportunities. If these interventions prove effective, and if the momentum of existing policy efforts is maintained and expanded, the disruptions to learning during the pandemic may be a window of opportunity to improve the education afforded to children.

Eligibility criteria

We consider all types of primary research, including peer-reviewed publications, preprints, working papers and reports, for inclusion. To be eligible for inclusion, studies have to measure learning progress using test scores that can be standardized across studies using Cohen’s d . Moreover, studies have to be in English, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Norwegian, Spanish or Swedish.

Search strategy and study identification

We identified relevant studies using the following steps. First, we developed a Boolean search string defining the population (school-aged children), exposure (the COVID-19 pandemic) and outcomes of interest (learning progress). The full search string can be found in Section 1.1 of Supplementary Information . Second, we used this string to search the following academic databases: Coronavirus Research Database, the Education Resources Information Centre, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Politics Collection (PAIS index, policy file index, political science database and worldwide political science abstracts), Social Science Database, Sociology Collection (applied social science index and abstracts, sociological abstracts and sociology database), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Web of Science. Second, we hand-searched multiple preprint and working paper repositories (Social Science Research Network, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, IZA, National Bureau of Economic Research, OSF Preprints, PsyArXiv, SocArXiv and EdArXiv) and relevant policy websites, including the websites of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations, the World Bank and the Education Endowment Foundation. Third, we periodically posted our protocol via Twitter in order to crowdsource additional relevant studies not identified through the search. All titles and abstracts identified in our search were double-screened using the Rayyan online application 49 . Our initial search was conducted on 27 April 2021, and we conducted two forward and backward citation searches of all eligible studies identified in the above steps, on 14 February 2022, and on 8 August 2022, to ensure that our analysis includes recent relevant research.

Data extraction

From the studies that meet our inclusion criteria we extracted all estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic, separately for maths and reading and for different school grades. We also extracted the corresponding sample size, standard error, date(s) of measurement, author name(s) and country. Last, we recorded whether studies differentiate between children’s socio-economic background, which measure is used to this end and whether studies find an increase, decrease or no change in learning inequality. We contacted study authors if any of the above information was missing in the study. Data extraction was performed by B.A.B. and validated independently by A.M.B.-M., with discrepancies resolved through discussion and by conferring with P.E.

Measurement and standardizationr

We standardize all estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic using Cohen’s d , which expresses effect sizes in terms of standard deviations. Cohen’s d is calculated as the difference in the mean learning gain in a given subject (maths or reading) over two comparable periods before and after the onset of the pandemic, divided by the pooled standard deviation of learning progress in this subject:

Effect sizes expressed as β coefficients are converted to Cohen’s d :

We use a binary indicator for whether the study outcome is maths or reading. One study does not differentiate the outcome but includes a composite of maths and reading scores 50 .

Level of education

We distinguish between primary and secondary education. We first consulted the original studies for this information. Where this was not stated in a given study, students’ age was used in conjunction with information about education systems from external sources to determine the level of education 51 .

Country income level

We follow the World Bank’s classification of countries into four income groups: low, lower-middle, upper-middle and high income. Four countries in our sample are in the upper-middle-income group: Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. All other countries are in the high-income group.

Data synthesis

We synthesize our data using three synthesis techniques. First, we generate a forest plot, based on all available estimates of learning progress during the pandemic. We pool estimates using a random-effects restricted maximum likelihood model and inverse variance weights to calculate an overall effect size (Fig. 3 ) 52 . Second, we code all estimates of changes in educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds during the pandemic, according to whether they indicate an increase, a decrease or no change in educational inequality. We visualize the resulting distribution using a harvest plot (Fig. 5 ) 53 . Third, given that the limited amount of available evidence precludes multivariate or causal analyses, we examine the bivariate association between COVID-19 learning deficits and the months in which learning was measured using a scatter plot (Fig. 4 ), and the bivariate association between COVID-19 learning deficits and subject, grade level and countries’ income level, using a series of violin plots (Fig. 6 ). The reported estimates, CIs and statistical significance tests of these bivariate associations are based on common-effects models with standard errors clustered by study, and two-sided tests. With respect to statistical tests reported, the data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. The distribution of estimates of learning deficits is shown separately for the different moderator categories in Fig. 6 .

Pre-registration

We prospectively registered a protocol of our systematic review and meta-analysis in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021249944) on 19 April 2021 ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021249944 ).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in the analyses for this manuscript were compiled by the authors based on the studies identified in the systematic review. The data are available on the Open Science Framework repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/u8gaz ). For our systematic review, we searched the following databases: Coronavirus Research Database ( https://proquest.libguides.com/covid19 ), Education Resources Information Centre database ( https://eric.ed.gov ), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ibss-set-c/ ), Politics Collection ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ProQuest-Politics-Collection/ ), Social Science Database ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/pq_social_science/ ), Sociology Collection ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ProQuest-Sociology-Collection/ ), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature ( https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/cinahl-database ) and Web of Science ( https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/ ). We also searched the following preprint and working paper repositories: Social Science Research Network ( https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/DisplayJournalBrowse.cfm ), Munich Personal RePEc Archive ( https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de ), IZA ( https://www.iza.org/content/publications ), National Bureau of Economic Research ( https://www.nber.org/papers?page=1&perPage=50&sortBy=public_date ), OSF Preprints ( https://osf.io/preprints/ ), PsyArXiv ( https://psyarxiv.com ), SocArXiv ( https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv ) and EdArXiv ( https://edarxiv.org ).

Code availability

All code needed to replicate our findings is available on the Open Science Framework repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/u8gaz ).

The Impact of COVID-19 on Children. UN Policy Briefs (United Nations, 2020).

Donnelly, R. & Patrinos, H. A. Learning loss during Covid-19: An early systematic review. Prospects (Paris) 51 , 601–609 (2022).

Hammerstein, S., König, C., Dreisörner, T. & Frey, A. Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289 (2021).

Panagouli, E. et al. School performance among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Children 8 , 1134 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Patrinos, H. A., Vegas, E. & Carter-Rau, R. An Analysis of COVID-19 Student Learning Loss (World Bank, 2022).

Zierer, K. Effects of pandemic-related school closures on pupils’ performance and learning in selected countries: a rapid review. Educ. Sci. 11 , 252 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

König, C. & Frey, A. The impact of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 41 , 16–22 (2022).

Storey, N. & Zhang, Q. A meta-analysis of COVID learning loss. Preprint at EdArXiv (2021).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919 (2016).

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A. & Geven, K. Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A Set of Global Estimates (World Bank, 2020).

Bloom, H. S., Hill, C. J., Black, A. R. & Lipsey, M. W. Performance trajectories and performance gaps as achievement effect-size benchmarks for educational interventions. J. Res. Educ. Effectiveness 1 , 289–328 (2008).

Hill, C. J., Bloom, H. S., Black, A. R. & Lipsey, M. W. Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2 , 172–177 (2008).

Belot, M. & Webbink, D. Do teacher strikes harm educational attainment of students? Labour 24 , 391–406 (2010).

Jaume, D. & Willén, A. The long-run effects of teacher strikes: evidence from Argentina. J. Labor Econ. 37 , 1097–1139 (2019).

Cygan-Rehm, K. Are there no wage returns to compulsory schooling in Germany? A reassessment. J. Appl. Econ. 37 , 218–223 (2022).

Ichino, A. & Winter-Ebmer, R. The long-run educational cost of World War II. J. Labor Econ. 22 , 57–87 (2004).

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J. & Greathouse, S. The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a narrative and meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 66 , 227–268 (1996).

Allington, R. L. et al. Addressing summer reading setback among economically disadvantaged elementary students. Read. Psychol. 31 , 411–427 (2010).

Smith, W. C. Consequences of school closure on access to education: lessons from the 2013–2016 Ebola pandemic. Int. Rev. Educ. 67 , 53–78 (2021).

Andrabi, T., Daniels, B. & Das, J. Human capital accumulation and disasters: evidence from the Pakistan earthquake of 2005. J. Hum. Resour . https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2020/039 (2021).

Parolin, Z. & Lee, E. K. Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 522–528 (2021).

Goudeau, S., Sanrey, C., Stanczak, A., Manstead, A. & Darnon, C. Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 1273–1281 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Murnane, R. J. & Au Yeung, N. Achievement gaps in the wake of COVID-19. Educ. Researcher 50 , 266–275 (2021).

van de Werfhorst, H. G. Inequality in learning is a major concern after school closures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2105243118 (2021).

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R. & Olson, L. S. Schools, achievement, and inequality: a seasonal perspective. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 23 , 171–191 (2001).

Aucejo, E. M. & Romano, T. F. Assessing the effect of school days and absences on test score performance. Econ. Educ. Rev. 55 , 70–87 (2016).

Gottfried, M. A. The detrimental effects of missing school: evidence from urban siblings. Am. J. Educ. 117 , 147–182 (2011).

Goodman, J. Flaking Out: Student Absences and Snow Days as Disruptions of Instructional Time (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014).

Birkelund, J. F. & Karlson, K. B. No evidence of a major learning slide 14 months into the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. European Societies https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2022.2129085 (2022).

Angrist, N., Djankov, S., Goldberg, P. K. & Patrinos, H. A. Measuring human capital using global learning data. Nature 592 , 403–408 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Torche, F. in Social Mobility in Developing Countries: Concepts, Methods, and Determinants (eds Iversen, V., Krishna, A. & Sen, K.) 139–171 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).

World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise (World Bank, 2018).

Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and Beyond (United Nations, 2020).

One Year into COVID-19 Education Disruption: Where Do We Stand? (UNESCO, 2021).

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Geven, K. & Iqbal, S. A. Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: a set of global estimates. World Bank Res. Observer 36 , 1–40 (2021).

Google Scholar

Ardington, C., Wills, G. & Kotze, J. COVID-19 learning losses: early grade reading in South Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 86 , 102480 (2021).

Hevia, F. J., Vergara-Lope, S., Velásquez-Durán, A. & Calderón, D. Estimation of the fundamental learning loss and learning poverty related to COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 88 , 102515 (2022).

Lichand, G., Doria, C. A., Leal-Neto, O. & Fernandes, J. P. C. The impacts of remote learning in secondary education during the pandemic in Brazil. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6 , 1079–1086 (2022).

Major, L. E., Eyles, A., Machin, S. et al. Learning Loss since Lockdown: Variation across the Home Nations (Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2021).

Di Pietro, G., Biagi, F., Costa, P., Karpinski, Z. & Mazza, J. The Likely Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Reflections Based on the Existing Literature and Recent International Datasets (Publications Office of the European Union, 2020).

Fuchs-Schündeln, N., Krueger, D., Ludwig, A. & Popova, I. The Long-Term Distributional and Welfare Effects of COVID-19 School Closures (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Kaffenberger, M. Modelling the long-run learning impact of the COVID-19 learning shock: actions to (more than) mitigate loss. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 81 , 102326 (2021).

Attewell, P. & Newman, K. S. Growing Gaps: Educational Inequality around the World (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

Betthäuser, B. A., Kaiser, C. & Trinh, N. A. Regional variation in inequality of educational opportunity across europe. Socius https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211019890 (2021).

Angrist, N. et al. Building back better to avert a learning catastrophe: estimating learning loss from covid-19 school shutdowns in africa and facilitating short-term and long-term learning recovery. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 84 , 102397 (2021).

Conley, D. & Johnson, T. Opinion: Past is future for the era of COVID-19 research in the social sciences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104155118 (2021).

Angrist, N., Bergman, P. & Matsheng, M. Experimental evidence on learning using low-tech when school is out. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6 , 941–950 (2022).

Lichand, G., Christen, J. & van Egeraat, E. Do Behavioral Nudges Work under Remote Learning? Evidence from Brazil during the Pandemic (Univ. Zurich, 2022).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5 , 1–10 (2016).

Tomasik, M. J., Helbling, L. A. & Moser, U. Educational gains of in-person vs. distance learning in primary and secondary schools: a natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Switzerland. Int. J. Psychol. 56 , 566–576 (2021).

Eurybase: The Information Database on Education Systems in Europe (Eurydice, 2021).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1 , 97–111 (2010).

Ogilvie, D. et al. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8 , 1–7 (2008).

Gore, J., Fray, L., Miller, A., Harris, J. & Taggart, W. The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: an empirical study. Aust. Educ. Res. 48 , 605–637 (2021).

Gambi, L. & De Witte, K. The Resiliency of School Outcomes after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Standardised Test Scores and Inequality One Year after Long Term School Closures (FEB Research Report Department of Economics, 2021).

Maldonado, J. E. & De Witte, K. The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. Br. Educ. Res. J. 48 , 49–94 (2021).

Vegas, E. COVID-19’s Impact on Learning Losses and Learning Inequality in Colombia (Center for Universal Education at Brookings, 2022).

Depping, D., Lücken, M., Musekamp, F. & Thonke, F. in Schule während der Corona-Pandemie. Neue Ergebnisse und Überblick über ein dynamisches Forschungsfeld (eds Fickermann, D. & Edelstein, B.) 51–79 (Münster & New York: Waxmann, 2021).

Ludewig, U. et al. Die COVID-19 Pandemie und Lesekompetenz von Viertklässler*innen: Ergebnisse der IFS-Schulpanelstudie 2016–2021 (Institut für Schulentwicklungsforschung, Univ. Dortmund, 2022).

Schult, J., Mahler, N., Fauth, B. & Lindner, M. A. Did students learn less during the COVID-19 pandemic? Reading and mathematics competencies before and after the first pandemic wave. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2022.2061014 (2022).

Schult, J., Mahler, N., Fauth, B. & Lindner, M. A. Long-term consequences of repeated school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic for reading and mathematics competencies. Front. Educ. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.867316 (2022).

Bazoli, N., Marzadro, S., Schizzerotto, A. & Vergolini, L. Learning Loss and Students’ Social Origins during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (FBK-IRVAPP Working Papers 3, 2022).

Borgonovi, F. & Ferrara, A. The effects of COVID-19 on inequalities in educational achievement in Italy. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4171968 (2022).

Contini, D., Di Tommaso, M. L., Muratori, C., Piazzalunga, D. & Schiavon, L. Who lost the most? Mathematics achievement during the COVID-19 pandemic. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 22 , 399–408 (2022).

Engzell, P., Frey, A. & Verhagen, M. D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118 (2021).

Haelermans, C. Learning Growth and Inequality in Primary Education: Policy Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis (The European Liberal Forum (ELF)-FORES, 2021).

Haelermans, C. et al. A Full Year COVID-19 Crisis with Interrupted Learning and Two School Closures: The Effects on Learning Growth and Inequality in Primary Education (Maastricht Univ., Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market (ROA), 2021).

Haelermans, C. et al. Sharp increase in inequality in education in times of the COVID-19-pandemic. PLoS ONE 17 , e0261114 (2022).

Schuurman, T. M., Henrichs, L. F., Schuurman, N. K., Polderdijk, S. & Hornstra, L. Learning loss in vulnerable student populations after the first COVID-19 school closure in the Netherlands. Scand. J. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.2006307 (2021).

Arenas, A. & Gortazar, L. Learning Loss One Year after School Closures (Esade Working Paper, 2022).

Hallin, A. E., Danielsson, H., Nordström, T. & Fälth, L. No learning loss in Sweden during the pandemic evidence from primary school reading assessments. Int. J. Educ. Res. 114 , 102011 (2022).

Blainey, K. & Hannay, T. The Impact of School Closures on Autumn 2020 Attainment (RS Assessment from Hodder Education and SchoolDash, 2021).

Blainey, K. & Hannay, T. The Impact of School Closures on Spring 2021 Attainment (RS Assessment from Hodder Education and SchoolDash, 2021).

Blainey, K. & Hannay, T. The Effects of Educational Disruption on Primary School Attainment in Summer 2021 (RS Assessment from Hodder Education and SchoolDash, 2021).

Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 Academic Year: Complete Findings from the Autumn Term (London: Department for Education, 2021).

Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 Academic Year: Initial Findings from the Spring Term (London: Department for Education, 2021).

Impact of COVID-19 on Attainment: Initial Analysis (Brentford: GL Assessment, 2021).

Rose, S. et al. Impact of School Closures and Subsequent Support Strategies on Attainment and Socio-emotional Wellbeing in Key Stage 1: Interim Paper 1 (National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) , 2021).

Rose, S. et al. Impact of School Closures and Subsequent Support Strategies on Attainment and Socio-emotional Wellbeing in Key Stage 1: Interim Paper 2 (National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), 2021).

Weidmann, B. et al. COVID-19 Disruptions: Attainment Gaps and Primary School Responses (Education Endowment Foundation, 2021).

Bielinski, J., Brown, R. & Wagner, K. No Longer a Prediction: What New Data Tell Us About the Effects of 2020 Learning Disruptions (Illuminate Education, 2021).

Domingue, B. W., Hough, H. J., Lang, D. & Yeatman, J. Changing Patterns of Growth in Oral Reading Fluency During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PACE Working Paper (Policy Analysis for California Education, 2021).

Domingue, B. et al. The effect of COVID on oral reading fluency during the 2020–2021 academic year. AERA Open https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584221120254 (2022).