Free Site Analysis Checklist

Every design project begins with site analysis … start it with confidence for free!

Architecture Essays 101: How to be an effective writer

- Updated: October 25, 2023

The world of architecture stands at a fascinating crossroads of creativity and academia. As architects cultivate ideas to shape the physical world around us, we are also tasked with articulating these concepts through words.

Architecture essays, thus, serves as a bridge between the visual and the textual, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of architectural ideas and their implications.

The ability to articulate thoughts, analyses, and observations on design and theory is as crucial as creating the designs themselves. An architectural essay is not just about presenting information but about conveying an understanding of spaces, structures, and the stories they tell.

Whether you’re delving into the nuances of a specific architectural movement , analyzing the design of a historic monument, or predicting the future of sustainable design, the written word becomes a powerful tool to express intricate ideas.

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for crafting insightful architectural essays, ensuring that your perspectives on this multifaceted discipline are communicated effectively and engagingly.

Understanding the Unique Nature of Architecture Essay s

Architecture sits on a unique line between the aesthetic and the analytical, where designs are appreciated not only for their aesthetic appeal but also for their functionality and historical relevance.

An architecture essay isn’t just a manifestation of this intricate blend; it’s a testament to it. Aspiring architects or students of architecture must grasp the singular characteristics of this type of essay to truly succeed.

Embracing Creativity

When one imagines essays, the mind typically conjures up dense blocks of text. However, an architecture essay allows, and even demands, a flair of creativity.

Visual representations, be it in the form of diagrams , sketches , or photographs , aren’t just supplementary; they can form the core of your argument.

For instance, if you’re discussing the evolution of skyscraper designs , a chronological array of sketches can provide an insightful, immediate overview that words might struggle to convey.

Recognizing and capitalizing on this visual component can elevate the impact of your essay.

Theoretical Foundations

Yet, relying solely on creative illustrations won’t suffice. The foundation of every solid architecture essay is a strong understanding of architectural theories, principles , and historical contexts. Whether you’re analyzing the gothic cathedrals of Europe or the minimalist homes of Japan, delving deep into the why and how of their designs is crucial.

How did the social, economic, and technological conditions of the time influence these structures?

…How do they compare with contemporary designs?

Theoretical exploration provides depth to your essay, grounding your observations and opinions in recognized knowledge and pre-existing debates.

Furthermore, case studies play an essential role in these essays.

Instead of making sweeping statements, anchor your points in specific examples. Discussing the sustainability features of a particular building or the ergonomic design of another offers tangible evidence to support your arguments.

Blending the Two

The magic of an architecture essay lies in seamlessly weaving the creative with the theoretical.

While you showcase a building’s design through visuals, delve into its history, purpose, and societal implications with your words. This blend not only offers a holistic understanding of architectural marvels but also caters to a broad audience, ensuring your essay is both engaging and enlightening.

In conclusion, understanding the unique blend of design elements and theoretical discussion in an architecture essay sets the foundation for an impactful piece.

It’s about striking a balance between showing and telling, between the artist’s sketches and the academic’s observations. With this understanding, you’re better equipped to venture into the exciting world of architectural essay writing.

Choosing the Right Topic

Architectural essays stand apart in their blend of technical knowledge, aesthetic sense, and historical context. The topic you choose not only sets the tone for your essay but can also significantly affect the enthusiasm and rigor with which you approach the writing.

Here’s a comprehensive guide to selecting the right topic for your architecture essay:

Find your Golden Nugget:

- Personal Resonance: Your topic should excite you. Think about the architectural designs, movements, or theories that have made an impact on you. Perhaps it’s a specific building you’ve always admired or an architectural trend you’ve noticed emerging in your city.

- Uncharted Territory: Exploring less-known or under-discussed areas can give you a unique perspective and make your essay stand out. Instead of writing another essay on Roman architecture, consider focusing on the influence of Roman architecture on contemporary design or even on a specific region.

Researching Broadly:

- Diversify Your Sources: From books and academic journals to documentaries and interviews, use varied materials to spark ideas. Often, an unrelated article can lead to a unique essay topic.

- Current Trends and Issues: Look at contemporary architecture magazines , websites , and blogs to gauge what’s relevant and debated in today’s architectural world. It might inspire you to contribute to the discussion or even challenge some prevailing ideas.

Connecting with Design Projects:

- Personal Projects: If you’ve been involved in a design project, whether at school or professionally, consider exploring themes or challenges you encountered. This adds personal anecdotes and insights which enrich the essay.

- Case Studies: Instead of going broad, consider going deep. Dive into a single building or architect’s work. Analyzing one subject in-depth can offer nuanced perspectives and help demonstrate your analytical skills.

Feasibility of Research:

- Availability of Resources: While choosing an obscure topic can make your essay unique, ensure you have enough resources or primary research opportunities to support your arguments.

- Scope: The topic should be neither too broad nor too narrow. It should allow for in-depth exploration within the word limit of the essay. For instance, “Modern Architecture” is too broad, but “The Influence of Bauhaus on Modern Apartment Design in Berlin between 1950-1970” is more focused.

Finding the right topic is a journey, and sometimes it requires a few wrong turns before you hit the right path. Stay curious, be patient, and remember that the best topics are those that marry your personal passion with academic rigor. Your enthusiasm will shine through in your writing, making the essay engaging and impactful.

Organizational Tools and Systems for an Effective Architecture Essay

Writing an essay on architecture is a blend of creative expression and meticulous research. As you delve deep into topics, theories, and case studies, it becomes imperative to keep your resources organized and accessible.

This section introduces you to a set of tools and systems tailored for architectural essay writing.

Using Digital Aids

- Notion: This versatile tool provides a workspace that integrates note-taking, database creation, and task management. For an architecture essay, you can create separate pages for your outline, research, and drafts. The use of templates can streamline the writing process and help in maintaining a structured approach.

- MyBib: Citing resources is a crucial part of essay writing. MyBib acts as a lifesaver by generating citations in various styles (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) and organizing them for easy access. Make sure to cross-check and ensure accuracy.

- Evernote: This tool allows you to clip web pages, articles, or images that inspire or contribute to your essay. You can annotate, highlight, and categorize your findings in different notebooks.

Systematic Research

- Organizing Findings: Develop a system where each finding, whether it’s a quote, image, or data point, has its source attached. Use color-coding or tags to denote different topics or relevance levels.

- Note Galleries: Convert your key points into visual cards. This technique can be especially helpful in architectural essays, where visual concepts may be central to your argument.

- Sorting by Source Type: Separate your research into categories like academic journals, books, articles, and interviews. This will make it easier when referencing or looking for a particular kind of information.

Strategies for Effective Literature Review

- Skimming vs. In-depth Reading: Not every source needs a detailed read. Learn to differentiate between foundational texts that require in-depth understanding and those where skimming for key ideas is sufficient.

- Note-making Techniques: Adopt methods like the Cornell Note-taking System, mind mapping, or bullet journaling, depending on what suits your thought process best. These methods help in breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks.

- Staying Updated: The world of architecture is evolving. Ensure you’re not missing any recent papers, articles, or developments related to your topic. Setting up Google Scholar alerts or RSS feeds can be beneficial.

Organizing your research and using tools efficiently will not only streamline your writing process but will also enhance the quality of your essay. As you progress, you’ll discover what techniques and tools work best for you.

The key is to maintain consistency and always be open to trying out new methods to improve your workflow and efficiency.

Writing Techniques and Tips for an Architecture Essay

An architecture essay, while deeply rooted in academic rigor, is also a canvas for innovative ideas, design critiques, and a reflection of the architectural zeitgeist. Here’s a deep dive into techniques and tips that can elevate your essay from merely informative to truly compelling.

Learning from Others

- Read Before You Write: Before diving into your own writing, spend some time exploring essays written by others. Understand the flow, the structure, the narrative techniques, and how they tie their thoughts cohesively.

- Inspirational Sources: Journals, academic papers, architecture magazines, and opinion pieces offer a wealth of writing styles. Notice how varied perspectives bring life to similar topics.

Using Jargon Judiciously

- Maintain Clarity: While it’s tempting to use specialized terminology extensively, remember your essay should be accessible to a broader audience. Use technical terms when necessary, but ensure they’re explained or inferred.

- Balancing Act: Maintain a balance between academic writing and creative expression. Let the jargon complement your narrative rather than overshadowing your message.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

- Plagiarism – The Silent Offender: Always give credit where credit is due. Even if you feel you’ve paraphrased sufficiently, ensure your sources are adequately referenced. Utilize plagiarism check tools to ensure originality.

- Stay Focused: It’s easy to get lost in the vast world of architecture. Ensure your writing stays on topic, refraining from veering too far from your central theme.

- Conciseness: While detailed elaboration can be insightful, verbosity can drown your main points. Be succinct where necessary.

Craft a Compelling Introduction and Conclusion

- First Impressions: Your introduction should provide context, state the purpose of your essay, and capture the reader’s interest. Think of it as the blueprint of a building – it should give an idea of what to expect.

- Tying it All Together: Your conclusion should summarize your main points, reflect on the implications of your findings, and perhaps even propose further areas of study or exploration.

Use Active Voice

- Direct and Dynamic: Active voice makes your writing sound more direct and lively. Instead of writing, “The design was critiqued by several architects,” try “Several architects critiqued the design.”

Personalize your Narrative

- Your Unique Voice: Architecture, at its core, is about human experiences and spaces. Infuse your writing with personal observations, experiences, or reflections where relevant. This personal touch can make your essay stand out.

Revise, Revise, Revise

- The First Draft is Rarely the Final: Writing is a process. Once you’ve penned down your initial thoughts, revisit them. Refine the flow, enhance clarity, and ensure your argument is both cogent and captivating.

Remember, an architecture essay is both a testament to your academic understanding and a reflection of your perspective on architectural phenomena. Treat it as a synthesis of research, observation, creativity, and structured argumentation, and you’ll craft an essay that resonates.

Incorporating Sources Seamlessly

In architectural essays, as with most academic endeavors, sources form the backbone of your assertions and claims. They lend credibility to your arguments and showcase your understanding of the topic at hand. But it’s not just about listing references.

It’s about weaving them into your essay so seamlessly that your reader not only comprehends your point but also recognizes the strong foundation on which your arguments stand. Here’s how you can incorporate sources effectively:

Effective Quotation:

- Blend with the Narrative: Direct quotations should feel like a natural extension of your writing. For instance, instead of abruptly inserting a quote, use lead-ins like, “As architect Jane Smith argues, ‘…'”

- Use Sparingly: While direct quotes can validate a point, over-relying on them can overshadow your voice. Use them to emphasize pivotal points and always ensure you contextualize their significance.

- Adapting Quotes: Occasionally, for the sake of flow, you might need to change a word or phrase in a quote. If you do, denote changes with square brackets, e.g., “[The building] stands as a testament to modern design.”

Referencing Techniques:

- Parenthetical Citations: Most academic essays utilize parenthetical (or in-text) citations, where a brief reference (usually the author’s surname and the publication year) is provided within the text itself.

- Footnotes and Endnotes: Some referencing styles prefer notes, which can provide additional context or information without interrupting the flow of the essay.

- Consistency is Key: Stick to one referencing style throughout your essay, whether it’s APA, MLA, Chicago, or any other format.

Using Notes Effectively:

- Annotate as You Go: When reading, jot down insights or connections you make in the margins or in your note-taking app. This will help you incorporate sources in a way that feels relevant and organic.

- Maintain a Bibliography: Keeping a running list of all the sources you encounter will make the final citation process smoother. With tools like Zotero or MyBib, you can auto-generate and manage bibliographies with ease.

- Critical Analysis over Summary: While it’s vital to understand and convey the main points of a source, it’s equally crucial to critique, interpret, or discuss its relevance in the context of your essay.

Remember, the objective of referencing isn’t just to show that you’ve done the reading or to avoid accusations of plagiarism. It’s about building on the work of others to create your unique narrative and perspective.

Always strive for a balance, where your voice remains at the forefront, but is consistently and credibly supported by your sources.

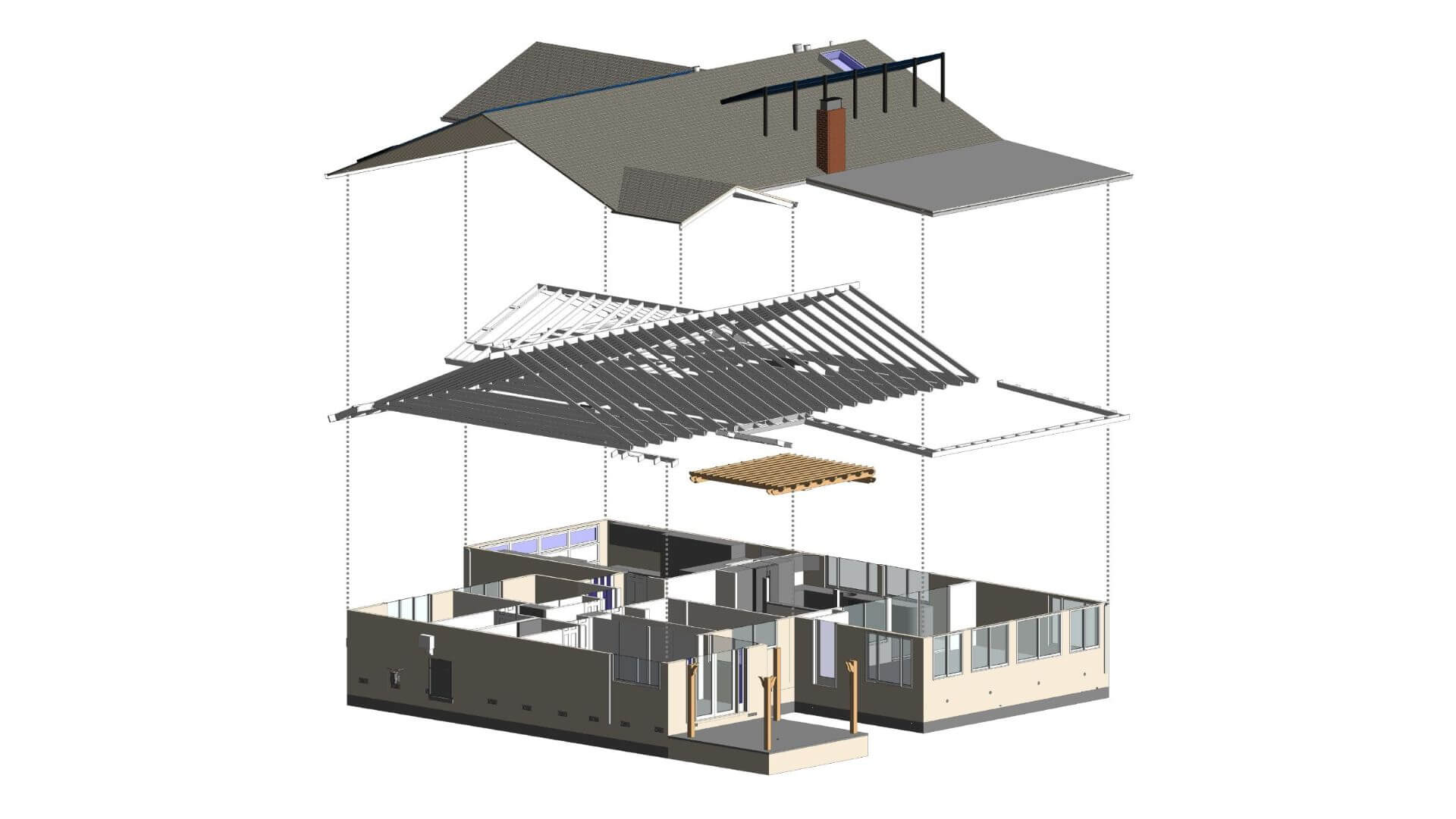

Designing Your Essay

Architecture is an intricate tapestry of creativity, precision, and innovation. Just as a building’s design can make or break its appeal, the visual presentation of your essay plays a pivotal role in how it’s received.

Below are steps and strategies to ensure your architecture essay isn’t just a treatise of words but also a feast for the eyes.

Visual Aesthetics: More Than Just Words

- Whitespace and Balance: Much like in architecture, the empty spaces in your essay—the margins, line spacing, and breaks between paragraphs—matter. Whitespace can make your essay appear more organized and readable.

- Fonts and Typography: Choose a font that is both legible and evocative of your essay’s tone. A serif font like Times New Roman may offer a traditional, academic feel, while sans-serif fonts like Arial or Calibri lend a modern touch. However, always adhere to submission guidelines if provided.

- Use of Imagery: If allowed, incorporating relevant images, charts, or diagrams can enhance understanding and add a visual flair to your essay. Make sure to caption them properly and ensure they’re of high resolution.

Relevance to Topic: Visuals That Complement Content

- Thematic Design: Ensure any design elements—be they color schemes, borders, or footers—tie back to your essay’s topic or the architectural theme you’re discussing.

- Visual Examples: If you’re discussing a specific architectural movement or an iconic building, consider incorporating relevant images, sketches, or blueprints to give readers a visual point of reference.

Examples of Unique Design Ideas

- Sidebars and Callouts: Much like how modern buildings might feature a unique design element that stands out, sidebars or callouts can be used to highlight crucial points, quotes, or tangential information.

- Integrated Infographics: For essays discussing data, trends, or historical timelines, infographics can be an innovative way to present information. They synthesize complex data into digestible visual formats.

- Annotations: If you’re critiquing or discussing a specific image, annotations can be helpful. They allow you to pinpoint and elaborate on specific elements within the image directly.

Consistency is Key

- Maintain a Theme: Just as in architectural design, maintaining a consistent visual theme throughout your essay creates harmony and cohesion. This could be in the form of consistent font usage, header designs, or color schemes.

- Captions and References: Any visual aid, be it a photograph, illustration, or chart, should be captioned consistently and sourced correctly to avoid plagiarism.

In the realm of architectural essays, the saying “ form follows function ” is equally valid. Your design choices should not just be aesthetic adornments but should serve to enhance understanding, readability, and engagement.

By taking the time to thoughtfully design your essay, you are not only showcasing your architectural insights but also your keen eye for design, thereby leaving a lasting impression on your readers.

Finalizing Your Essay

Finalizing an architecture essay is a task that demands a meticulous approach. The difference between an average essay and an outstanding one often lies in the refinement process. Here, we explore the steps to ensure that your essay is in its best possible form before submission.

Proofreading:

- Grammar and Syntax Checks: Always use tools like Grammarly or Microsoft Word’s spellchecker, but remember, they aren’t infallible. After an initial electronic check, read the essay aloud. This can help in catching awkward phrasing and any overlooked errors.

- Consistency in Language and Style: Ensure that you maintain a uniform style and tone throughout. If you begin with UK English, for instance, stick with it till the end.

- Flow and Coherence: The essay should have a logical progression. Each paragraph should lead seamlessly into the next, with clear transitions.

Feedback Loop:

- Peer Reviews: Having classmates or colleagues read your essay can provide fresh perspectives. They might catch unclear sections or points of potential expansion that you might have missed.

- Expert Feedback: If possible, seek feedback from instructors or professionals in the field. Their insights can greatly enhance the quality of your content.

- Acting on Feedback: Merely receiving feedback isn’t enough. Be prepared to make revisions, even if it means letting go of sections you’re fond of, for the overall improvement of the essay.

Aligning with University Requirements:

- Formatting: Adhere strictly to the specified format. Whether it’s APA, Chicago, or MLA, make sure your citations, font, spacing, and margins are in line with the guidelines.

- Word Count: Most institutions will have a stipulated word count. Ensure you’re within the limit. If you’re over, refine your content; if you’re under, see if there are essential points you might have missed.

- Supplementary Materials: For architecture essays, you might need to attach diagrams, sketches, or photographs. Ensure these are clear, relevant, and properly labeled.

- Referencing: Properly cite all your sources. Any claim or statement that isn’t common knowledge needs to be attributed to its source. Also, ensure that your bibliography or reference list is comprehensive and formatted correctly.

Final Read-through:

- After making all the changes, set your essay aside for a day or two, if time permits. Come back with fresh eyes and do one last read-through. This distance can often help you catch any remaining issues.

Finalizing your architecture essay is as vital as the initial stages of research and drafting. The care you take in refining and polishing your work reflects your commitment to excellence. When you’ve gone through these finalization steps, you can submit your essay confidently, knowing you’ve given it your best shot.

To Sum Up…

Writing an architecture essay is a unique challenge that requires a balance of creativity, critical thinking, and academic rigor. The process demands not just a deep understanding of architectural theories and case studies but also an ability to express these complex ideas clearly and compellingly.

Throughout this article, we have explored various facets of crafting an excellent architecture essay, from choosing a resonant topic and conducting thorough research to employing effective writing techniques and incorporating sources seamlessly.

The visual aspect of an architecture essay cannot be overlooked. As architects blend functionality with aesthetics in their designs, so too must students intertwine informative content with visual appeal in their essays. This is an opportunity to showcase not only your understanding of the subject matter but also your creativity and attention to detail.

Remember, a well-designed essay speaks volumes about your passion for architecture and your dedication to the discipline.

As we wrap up this guide, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of meticulous proofreading and seeking feedback. These final steps are vital in ensuring that your essay is free from errors and that your arguments are coherent and compelling.

Engaging in a feedback loop with peers, mentors, or advisors can provide valuable insights and help to refine your work further.

Additionally, always ensure that your essay aligns with the specific requirements set forth by your university or institution. Pay attention to details like font styles, referencing methods, and formatting guidelines.

These elements, while seemingly minor, play a significant role in creating a polished and professional final product.

Keep practicing, keep learning, and remember that each essay is a stepping stone toward mastering the art of architectural writing.

FAQs about Architecture Essays

Do architecture students have to write essays.

Yes, architecture students often have to write essays as part of their academic curriculum. While architecture is a field that heavily involves visual and practical skills, essays and written assignments play a crucial role in helping students develop their critical thinking, research, and analytical skills.

While hands-on design work and practical projects are integral parts of an architectural education, essays play a crucial role in developing the theoretical, analytical, and communication skills necessary for success in the field.

By writing essays, architecture students learn to think critically, research effectively, and communicate their ideas clearly, laying a strong foundation for their future careers.

Every design project begins with site analysis … start it with confidence for free!.

As seen on:

Unlock access to all our new and current products for life .

Providing a general introduction and overview into the subject, and life as a student and professional.

Study aid for both students and young architects, offering tutorials, tips, guides and resources.

Information and resources addressing the professional architectural environment and industry.

- Concept Design Skills

- Portfolio Creation

- Meet The Team

Where can we send the Checklist?

By entering your email address, you agree to receive emails from archisoup. We’ll respect your privacy, and you can unsubscribe anytime.

Best Architecture Essay Examples & Topics

Architecture essays can be challenging, especially if you are still a student and in the process of acquiring information. First of all, you are to choose the right topic – half of your success depends on it. Pick something that interests and excites you if possible. Second of all, structure your paper correctly. Start with an intro, develop a thesis, and outline your body paragraphs and conclusion. Write down all your ideas and thoughts in a logical order, excluding the least convincing ones.

In this article, we’ve combined some tips on how to deliver an excellent paper on the subject. Our team has compiled a list of topics and architecture essay examples you can use for inspiration or practice.

If you’re looking for architecture essay examples for college or university, you’re in the right place. In this article, we’ve collected best architecture essay topics and paper samples together with writing tips. Below you’ll find sample essays on modern architecture, landscape design, and architect’s profession. Go on reading to learn how to write an architecture essay.

Architecture Essay Types

Throughout your academic life, you will encounter the essay types listed below.

Argumentative Architecture Essay

This type uses arguments and facts to support a claim or answer a question. Its purpose is to lay out the information in front of the reader that supports the author’s position. It does not rely on the personal experiences of the writer. For instance, in an argumentative essay about architecture, students can talk about the positive aspects of green construction. You can try to demonstrate with facts and statistics why this type of building is the ultimate future.

Opinion Architecture Essay

This essay requires an opinion or two on the topic. It may try to demonstrate two opposing views, presenting a list of arguments that support them. Remember that the examples that you use have to be relevant. It should be clear which opinion you support. Such an essay for the architecture topic can be a critique of architectural work.

Expository Architecture Essay

This writing shares ideas and opinions as well as provides evidence. The skill that is tested in this essay is the expertise and knowledge of the subject. When you write an expository essay, your main goal is to deliver information. It would be best if you did not assume that your audience knows much about the subject matter. An expository essay about architecture can be dedicated to the importance of sustainable architecture.

Informative Architecture Essay

Such essays do not provide any personal opinions about the topic. It aims to provide as much data as possible and educate the audience about the subject. An excellent example of an informative essay can be a “how-to essay.” For instance, in architecture, you can try to explain how something functions or works.

Descriptive Architecture Essay

It’s an essay that aims to create a particular sentiment in the reader. You want to describe an object, idea, or event so that the reader gets a clear picture. There are several good ways to achieve it: using creative language, including major and minor details, etc. A descriptive essay about architecture can be focused on a building or part of a city. For instance, talk about a casino in Las Vegas.

Narrative Architecture Essay

Here, your goal is to write a story. This paper is about an experience described in a personal and creative way. Each narrative essay should have at least five elements: plot, character, setting, theme, and conflict. When it comes to the structure, it is similar to other essays. A narrative paper about architecture can talk about the day you have visited a monument or other site.

Architecture Essay Topics for 2022

- The most amazing architecture in the world and the most influential architects of the 21st century.

- Some pros and cons of vertical housing: vertical landscape in the history of architecture.

- A peculiar style of modern architecture in China.

- The style of Frank Lloyd Wright and architecture in his life.

- New tendencies in rural housing and architecture.

- Ancient Roman architecture reimagined.

- The role of architecture in pressing environmental problems in modern cities.

- Islamic architecture: peculiar features of the style.

- Earthquake-resistant infrastructure in building houses.

- How precise is virtual planning?

- Houses in rural areas and the cities. How similar are they?

- A theory of deconstruction in postmodern architecture.

- The influence of Greek architecture on modern architecture.

- Aspects to consider when building houses for visually impaired people.

- Disaster-free buildings: challenges and opportunities.

- European architectural influence on the Islamic world.

- The architecture of old Russian cities.

In the above section, we’ve given some ideas to help you write an interesting essay about architecture. You can use these topics for your assignment or as inspiration.

Thank you for reading the article. We’ve included a list of architecture essay examples further down. We also hope you found it helpful and valuable. Do not hesitate to share our article with your friends and peers.

410 Best Architecture Essay Examples

Mathematics in ancient greek architecture, the eiffel tower as a form of art.

- Words: 1361

Islamic Architecture: Al-Masjid Al-Haram, Ka’aba, Makka

- Words: 1190

Calligraphy Inscription in Islamic Architecture and Art

- Words: 3269

An Architectural Guide to the Cube Houses

- Words: 3584

Comparison of Traditional and Non-Traditional Mosques

- Words: 1611

Stonehenge and Its Significance

Filippo brunelleschi and religious architecture.

- Words: 2121

Context and Building in Architecture

- Words: 3367

The Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright

- Words: 3374

Traditional Roman vs. Chinese Courtyard House

- Words: 4070

The Architecture of Ancient Greece Found in Los Angeles

- Words: 1763

Paper Church Designed by Shigeru Ban

- Words: 1665

Charles Jencks: Language of Post Modern Architecture

- Words: 2204

Islamic Architectural Design

- Words: 1407

Monumentalism in Architecture

- Words: 2840

Symbolism and Superstition in Architecture and Design

- Words: 2252

Skyscrapers in Dubai: Buildings and Materials

- Words: 2468

Architecture History. Banham’s “Theory and Design in the First Machine Age”

- Words: 1254

Louis Sullivan: Form Follows Function

- Words: 1099

Futuristic Architecture: An Overview

- Words: 1740

Kidosaki House by Tadao Ando

- Words: 1064

Architecture as an Academic Discipline

- Words: 1375

The Parthenon and the Pantheon in Their Cultural Context

- Words: 1416

Gothic Revivalism in the Architecture of Augustus Pugin

- Words: 1704

S. R. Crown Hall: The Masterpiece of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

- Words: 2216

Architecture of the Gherkin Building

Saint peter’s basilica.

- Words: 1932

Harvard Graduate Center Building and Its Structure

Urbanism in architecture: definition and evolution, translation from drawing to building.

- Words: 2289

The Death of Modern Architecture

- Words: 2149

Connections of Steel Frame Buildings in 19th Century

- Words: 2681

Architectural Regionalism Definition

- Words: 3352

Empire State Building Structural Analysis With Comparisons

Postmodern architecture vs. international modernism.

- Words: 1655

The Dome of the Rock vs. the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus

- Words: 1506

Personal Opinion on the Colosseum as an Artwork

Ronchamp chapel from le corbusier.

- Words: 3434

Form and Function in Architecture

- Words: 3377

Architecture: Kansai International Airport

- Words: 3829

Ancient Chinese Architecture

- Words: 1097

Sydney Opera House

- Words: 2209

The Pantheon of Rome and the Parthenon of Athens

Architecture in colonialism and imperialism.

- Words: 2408

The First Chicago School of Architecture

Perspective drawing used by renaissance architects.

- Words: 2012

The BMW Central Building: Location and Structure

- Words: 2671

The Question of Ornament in Architectural Design

- Words: 1971

Islamic Gardens: Taj Mahal and Alhambra

Risks in construction projects: empire state building.

- Words: 2856

“4” Wonders of the World

The getty center in los angeles.

- Words: 1314

Greek Revival Influenced American Architecture

- Words: 3104

Influential Architecture: Summer Place in China

- Words: 1491

The Architecture of the Medieval Era: Key Characteristics

European influence on the architecture of the americas, professional and ethical obligation of architecture.

- Words: 2794

The History of Architecture and It Changes

- Words: 3330

Columns and Walls of Mies Van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion

- Words: 1518

Architect of the Future

Centre georges pompidou’s design analysis, gothic style and cult of the virgin in medieval art, modern patio house architecture, chrysler building in new york city, saint sernin and chartres cathedral.

- Words: 1196

Kandariya Mahadeva Temple and Taj Mahal: Style and Meaning

- Words: 1371

Greco-Roman Influence on Architecture

Frank lloyd wright’s approach to sustainability, the angkor vat temple, cambodia, the garden by the bay architectural design, design theory in “ornament and crime” essay by loos.

- Words: 1752

Alhambra Palace – History and Physical Description

- Words: 1214

Trinity Church: An Influential Architectural Design

- Words: 1374

The Architectural Design of Colosseum

- Words: 2161

The Evolution of the Greek Temple

- Words: 1934

The St. Louis Gateway Arch

- Words: 1630

Modern Architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier

- Words: 3291

Frank Lloyd Wright and his Contribution to Architecture

- Words: 3401

The Water Cube Project and Design-Build Approaches

Islamic architecture: environment and climate.

- Words: 1436

Expressionism in Architecture: The Late 19th and the Early 20th Century

- Words: 1927

The Church and Reliquary of Sainte-Foy: Contextual Analysis

Fashion and architecture: relationship.

- Words: 5634

Arc de Triomphe. History. Construction

- Words: 2326

Critical Evaluation of the Landscape Architecture

- Words: 2865

History of Architecture: Italian Mannerist and Baroque Architects

- Words: 3001

“Architecture: The Story of Practice” by Cuff

The vebjorn sand da vinci project.

- Words: 3579

Contemporary Issues in the Field of Architecture That Affect Working

Japanese shrines architecture uniqueness.

- Words: 2280

Modern Architecture: Mary Gates Hall

Tadao ando and the modern way of living.

- Words: 2170

Pyramids of Giza and Their Construction Mystery

Homa capital columns’ at ancient persian persepolis city, the portunus temple: a creation of the ancient times.

- Words: 1156

Perspective Drawing in Renaissance Architecture

Roman architecture and engineering, psychological consideration in proposed architectural plan, aspects of organic architectural philosophy, maya lin’s vietnam veterans memorial, modern architecture: style of architecture, the yangzhou qingpu slender west lake cultural hotel, how did adolf loos achieve sustainability, the lovell beach house by rudolph schindler, the st. denis basilica virtual tour, architecture of moscow vs. sankt petersburg, the east san josé carnegie branch library’s architecture, analysis of byzantine architecture, cultural impact on muslim architecture.

- Words: 1152

Egyptian & Greek Art & Architecture

The gothic style in architecture and art, how architectural styles reflect people’s beliefs.

- Words: 1720

Renaissance and Executive Order Draft: Summary

The building of the georgia state capitol and the sidney lanier bridge.

- Words: 1222

Five Points for an Architecture of Other Bodies

Vietnam veterans memorial by maya ying lin, beijing daxing international airport.

- Words: 3588

Architecture as Facility Management Principle

Architeture and function in buddhism, christianity, and islamic religion.

- Words: 1904

Architecture Essay Examples

20 Must-Read Architecture Essay Examples for Students

Published on: May 5, 2023

Last updated on: Jan 30, 2024

Share this article

Are you a student struggling with writing an architecture essay? Perhaps you are looking for inspiration, or maybe you need guidance on how to develop your argument.

Whatever the reason may be, you have come to the right place!

In this blog, we provide a range of architecture essay examples covering different styles, time periods, and topics. From modernist to postmodernist architecture, we offer examples that will help you gain a deeper understanding of the subject.

So, let's take a journey through the world of architecture essay examples together!

On This Page On This Page -->

What Is Architecture Essay

An architecture essay is a type of academic writing that explores the design, construction, and history of buildings, structures, and spaces. It requires technical knowledge and creative thinking to analyze and interpret architectural theories, and practices.

Letâs take a look at a short essay on architecture:

Architecture College Essay Examples

Let's take a look at some examples of compelling architecture college essays that demonstrate creativity and critical thinking skills.

The Influence of Cultural Heritage on Architectural Design

The Importance of Aesthetics in Architecture

Scholarship Essay Examples For Architecture

These scholarship essay examples for architecture demonstrate the writers' devotion to excellence and creativity. Letâs check them out!

From Blueprint to Reality: The Importance of Detail in Architecture

The Intersection of Technology and Artistry in Architecture

Common Architecture Essay Examples

Let's take a look at some common architecture essay pdf examples that students often encounter in their academic writing.

History of Architecture Essay Examples

The Evolution of Egyptian Architecture

The Influence of Islamic Architecture

Gothic Architecture Essay Examples

The Key Characteristics of Gothic Style Architecture

The Role of Gothic Architecture in Medieval Europe

Modern Architecture Essay Examples

The Development of Modernist Architecture

The Influence of Postmodern Architecture

Cornell Architecture Essay Examples

The Legacy of Cornell Architecture

Innovative Design Approaches in Cornell Architecture

Types of Architectural Essay

Here are some potential sample papers for each type of architectural essay:

- Historical Analysis

The Effect of Ancient Greece Architecture on Contemporary Design

- Critical Analysis

The Role of Materiality in Herzog and de Meuron's Tate Modern

- Comparative Analysis

A Comparison of Modernist and Postmodernist Approaches to Design

Additional Architecture Essay Examples

Architecture essays cover a broad range of topics and styles. Here are some additional architecture essay prompts to help you get started.

Essay on Architecture As A Profession

Essay About Architecture As Art

Architecture Essay Question Examples

How To Write An Architecture Essay

To write a successful architecture essay, follow these steps:

Step#1 Understand the assignment

Read the assignment prompt carefully to understand what the essay requires.

Step#2 Research

Conduct thorough research on the topic using reliable sources such as books, journals, and academic databases.

Step#3 Develop a thesis

Based on your research, develop a clear and concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument of your essay.

Step#4 Outline

Create an outline to organize your ideas and ensure that your essay flows logically and coherently.

Step#5 Write the essay

Start writing your essay according to your outline:

Introduction:

- Begin with a hook that grabs the reader's attention.

- Provide background information on the topic.

- End with a clear thesis statement.

Architecture Essay Introduction

- Use evidence to support your arguments.

- Organize your ideas logically with clear transitions.

- Address counterarguments.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the main points and restate the thesis.

- Provide final thoughts and consider broader implications.

- End with a memorable closing statement.

Architecture Essay Conclusion

Step#6 Edit and proofread

Review your essay for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. Make sure that your ideas are expressed clearly and concisely.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

History of Architecture Essay Topics

- The Impact of Ancient Greek Architecture on Modern Building Design in the United States

- The Development of Gothic Architecture as an Architectural Movement in Medieval Europe

- A Case Study of Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie Style Architecture and its Influence on American Home Design

- The Rise of Skyscrapers in the United States. A Look at the History and Impact of Tall Buildings on People Living and Working in Cities

- The Origins of Modernism in Architecture: Tracing the Roots of this Architectural Movement from Europe to the United States

- A Comparative Analysis of Chinese and Japanese Traditional Architecture: Exploring the Differences and Similarities of These Two Styles Originated from Asia

- The Influence of Islamic Architecture on the Development of Spanish Colonial Architecture in the United States

- A Case Study of Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye: Analyzing the Characteristics of This Architectural Movement and Its Influence on Modern Architecture

- The Evolution of Green Architecture: Examining the History of Sustainable Building Design and Its Impact on People Living and the Environment

- The Revival of Art Deco Architecture. Tracing the Return of This Style Originated in the 1920s and 1930s in the United States.

In summary!

We hope the examples we've provided have sparked your imagination and given you the inspiration you need to craft your essay. Writing about architecture requires good skills, and your essay is an opportunity to showcase your unique ideas in the field.

Remember, even the greatest architects started somewhere, and the key to success is practice. But if you're feeling stuck and need a little help bringing your vision to life, don't worry!

At CollegeEssay.org , our expert writers are here to provide you with top-quality essay writing service that will impress even the toughest critics.

Whether you need help finding the right words or want assistance with organizing your ideas, our AI essay generator can guide you every step of the way.

So why wait? Contact our architecture essay writing service today and take the first step toward building your dream career in architecture!

Nova A. (Literature, Marketing)

As a Digital Content Strategist, Nova Allison has eight years of experience in writing both technical and scientific content. With a focus on developing online content plans that engage audiences, Nova strives to write pieces that are not only informative but captivating as well.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

How to write an architecture essay tips

How to write an architecture essay advice, Architectural assignment writing tips, Online student work guide

How to Write an Architecture Essay

post updated 17 February 2024

Writing an essay can be a difficult assignment for any student. However, they are critical in advancing your academic career. These essays, especially if you’re pursuing architecture, demonstrate your knowledge of a subject as well as your ability to compose and present it elegantly on paper.

It’s not easy to write a good architecture essay. You won’t have to write an essay like this unless you’re an architectural student, and even then, you can have trouble finding suitable rules, even if you want to buy essays online. This article seeks to fill that need.

22 February 2022

So, what goes into writing an outstanding architectural essay? What are the considerations you should make before writing one?

You can get the best essay writing service today by following the link https://goalessay.com/

Read on as we walk you through the vital elements of a well-crafted architecture essay that will captivate your audience and aid your academic career!

It’s time to do some research now that you have a good notion about the issue you’re interested in. Investigate the journals, encyclopaedias, and articles available. It could be from your college’s library or a reputable online source.

Any source would suffice as long as it is credible and of good quality. Remember to alternate between your research and the architecture thesis statement you chose in the previous phase. You won’t get sidetracked this way. For instance, suppose you’re writing about a certain architectural structure or the works of a notable architect in history. You could start your essay by describing the aesthetics of a well-known structure. Move on to preparing the arrangement of your essay if you’re satisfied with your research abilities.

Develop Your Writing Creativity

You must be familiar with appropriate terminology and characterising terms when writing this type of essay. There is no way around it because it is a requirement of an architectural paper. Consider the following scenario: you’re describing a potential project to your lecturer or boss.

You must be in a position and possess the necessary skills to communicate your vision to them in the same way that you have it in your head. It’s how you’ll present your concept to others. You must learn to use adjectives effectively, unlike in other forms of essays. Visual imagery must be presented in such a way that the listener or reader can live vicariously through your wonderfully weaved words.

Write an Introduction

The first thing you should work on when writing an essay is the introduction paragraph. In no more than five sentences, try to capture the essay’s main point. However, you must make sure that these statements are strong enough to hold the reader’s attention and persuade them to finish reading. Your thesis statement must also be included here.

The Essay’s Body

These paragraphs should at the very least concisely describe one fact, with sufficient proof to back up your thesis. Now that you’ve learned how to write an excellent essay, it’s time to put your own spin on things.

This will help your work stand out and add a personal touch. Throughout the key portions of this essay, you must demonstrate your ability to write academically logical and sharp information. You can always start with a rough draft and work your way up to a polished essay. Keep the paper’s focus; this is when the planning comes in handy.

Concluding Paragraph

Finally, your architecture-based essay should be concluded in such a way that it recapitulates the main topic. This area is just as important as the others, and it requires your meticulous attention to detail in order to be perfected. Its purpose is to emphasise your idea one last time in order to create a lasting impression on the reader.

In one last paragraph, summarise the main points of your essay in a thought-provoking and convincing manner. To avoid losing effectiveness, try not to make this too long. Did you believe you’d be able to submit it now that you’ve finished it? – Certainly not. Even professionals stress the importance of proofreading. Check your essay for errors and coherence several times. For an unbiased evaluation, you can even ask a trustworthy person to conduct it for you.

You’ll undoubtedly entice the assessor if you follow these methods. You’ll be able to compose an essay that sticks with them for a long time. Without patience and hard work, nothing can be perfected. Begin practising and you’ll soon find yourself on your way to becoming an outstanding future architect.

Comments on this guide to how to write an architecture essay article are welcome.

Architecture Essays

Essays Posts

Choices for 2022: Reliable Writing Services

10 Effective Writing Strategies To Improve Your Essays

The Importance of Essay Writing Service

Higher Education

Higher Education Building Design – architectural selection below:

College building designs

University building designs

Student Work building designs

Comments / photos for the How to write an architecture essay advice page welcome.

How to Write an Ideal Architecture Essay

Composing a strong essay on architecture is far from easy. You will probably not have to write an essay of this type unless you are an architecture student, and when you do, you might find it hard to get your hands on relevant guidelines even if you’d like to buy essay online . That is precisely the gap this article aims to fill.

Getting started on your essay

Being unable to find a head-start is one of the most common difficulties a writer faces when it comes to devising an essay. Brainstorming ideas for choosing a topic is pressure in itself. If you get overwhelmed just by the thought of it, you are not alone. When it comes to essays about architecture, the field is undoubtedly broad and requires you to narrow down the scope of your focus. This is the first step you need to nail in order to come up with a good essay. You can put in all the effort, but it will go all in vain if the basic idea that you started with was not as impactful. You should check out Edu Jungles to find some high-level essays to get inspiration from. For this purpose, you need to zero in on a subject that can be broken down based on time period, geographical location, and style. This will provide you with the much-needed structure of your essay. Once you have it a decent idea about the direction you need your ship needs to be steered in, try shortlisting smaller topics in the subcategory. Depending on your interest, previous knowledge, and availability of sources decide a topic for crafting your essay.

Now that you would have a decent idea about the topic you are interested in, it is time to research. Dive into the journals, encyclopedias and articles that you can find. It can be from your college’s library or a reliable source on the internet. Any source would do as long as it has credibility and quality. Do not forget to keep switching between the research work and the architecture thesis statement that you settled on in the previous step.This will prevent you from getting sidetracked. For example, you are writing on a specific architectural structure or maybe describing the works of a famous architect in history. You may include the description of the aesthetics of a famous building and start building your essay from there. Once satisfied with your research proficiency, move to the planning of the structure of your essay. Needless to say, it will depend on the audience of your work. So keep in mind the requirements and expectations of the evaluator before starting working on your masterpiece. You have to be strategical and tactical when it comes to choosing the style. Mostly, you will be asked to follow an analytical style.

Tap into Creative Writing Skills

While crafting this type of essay, you need to be proficient with relevant vocabulary and describing words. It is the demand of an architecture paper, and there is no way around it. Now think about this, you are describing a future project to your professor or employer. You must be in the position and have the skillset to convey the vision to them just like you have in your mind. It is the way you will be pitching your idea. Unlike other types of essays, you must learn using adjectives effectively. You need to present visual imagery in such a way that the listener or reader lives vicariously through your beautifully woven words. It is an art form that not everybody can master but if you are here taking the initiative, consider it half the battle won. If you find yourself weak in this department, take support and get pre-written essays and learn to master the art of essay writing.

Writing an introduction

When you start building an essay, the first thing that needs to be perfected will be your introductory paragraph. Try to encapsulate the essential idea of the essay in no more than five sentences. However, you need to ensure that these statements are compelling enough to get the reader engrossed and convinced to read till the end. Here you will also have to include your thesis statement. Let us take a look at a few persuasive architecture thesis statement examples.

“Cities should allow for open spaces and structures that go well with surroundings” or maybe something along the lines of explaining the structure of a building and the reason for its prominence. Ensure that whatever you decide to go with has a debatable element. The reader does not want you to parrot back to them. Instead, they want your take on the subject.

The body of the essay

These paragraphs should aim to concisely articulate one fact at the least, with having enough evidence to support your thesis. Now that you are learning ways of crafting essay effectively, it is highly encouraged to add your original thoughts. This will help your work stand out and bring an element of uniqueness to it. You have to convey your ability to produce academically coherent and sharp content through the main sections of this essay. You can always start from a draft and work your way up to a well-thought-out essay. Do not lose the focus of the paper; this is where the planning helps.

Concluding paragraph

Lastly, conclude your architecture-based essay in such a way that it recapitulates the idea behind it. This section is just as significant as the others and needs your attention to detail for perfecting it. It aims to stress your point one last time to leave a lasting impact on the reader. Summarize the highlights of your essay in one final paragraph and write it in a thought-provoking and persuasive manner. Try not to elongate this to prevent losing effectiveness. Now that you are done with it, did you think you could submit it already? -Absolutely not. Even the experts emphasize on the significance of proofreading. Go through your essay multiple times to catch any possible mistakes and check for coherence while you are at it. You can even ask a reliable person to do it for you for an unbiased review.

With these steps followed, you are surely going to entice the evaluator. You will be able to write an essay that would linger in their heads for quite a while. With that said, nothing can be perfected without patience and hard work. Start practicing and see yourself emerge as an excellent future architect.

Hire an Expert:

Essay writing is a very daunting and time taking task, specially for those students who are not from English background or doing part-time jobs. In such a situation, it is always advisable to take help from an expert. There are many expert UK essay writers online and provide top essay writing services, which can provide you with high-quality and error-free essays.

Unveiling the Magic of Conceptual Architectural Design

The conceptual architectural design phase is not merely a preliminary step in the design process; it’s a crucible where ideas are forged into tangible forms. At this stage, architects embark on a conceptual architectural design journey of exploration and innovation, seeking to encapsulate the essence of their vision in a cohesive conceptual framework. This conceptual […]

50 Best Wall Moulding Design Inspirations For Your Interiors

Wall Moulding Design is a great way to amp up your space and elevate the overall look of your home. There are a wide range of moulding designs that can add a distinct character to your space. Wall moulding design comes from different kinds of materials, such as PVC, plaster, wood, etc. The right choice […]

TADstories With Ar. Deep Sakhare | Barakhadee Studio

Ar. Deep Sakhare, the founder of Barakhadee Studio, shares his passion for architecture and design which entwines with the admiration for travelling. Barakhadee Studio is an architectural and interior design studio, founded by Ar. Deep Sakhare in the city of Pune in Maharashtra. The firm focuses on approaching every project with a new perspective and […]

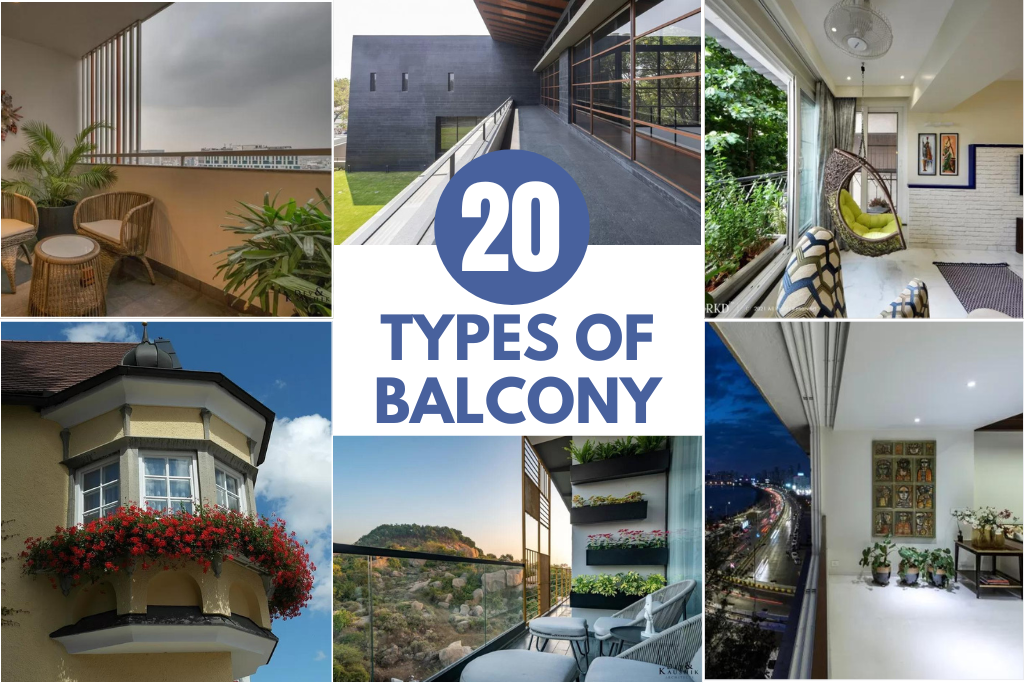

20 Types of Balcony That Redefine Outdoor Spaces

Different types of balcony, with their ability to extend indoor living spaces into the open air, have become an essential feature of architectural design. Across the globe, architects and designers have embraced different types of balcony as a means to enhance both the aesthetic appeal and functionality of buildings. In this comprehensive exploration, we delve […]

TADstories with Ar.Anup Murdia and Ar.Sandeep Jain | Design Inc.

Ar. Anup Murdia and Ar. Sandeep Jain, the founders of Design Inc. share their journey of embarking architecture with the passion for understanding spaces. Design Inc. is an architectural firm situated in Udaipur, founded by Ar. Anup Murdia and Ar. Sandeep Jain in 2011. The firm believes in creating spaces with overall understanding of certainties […]

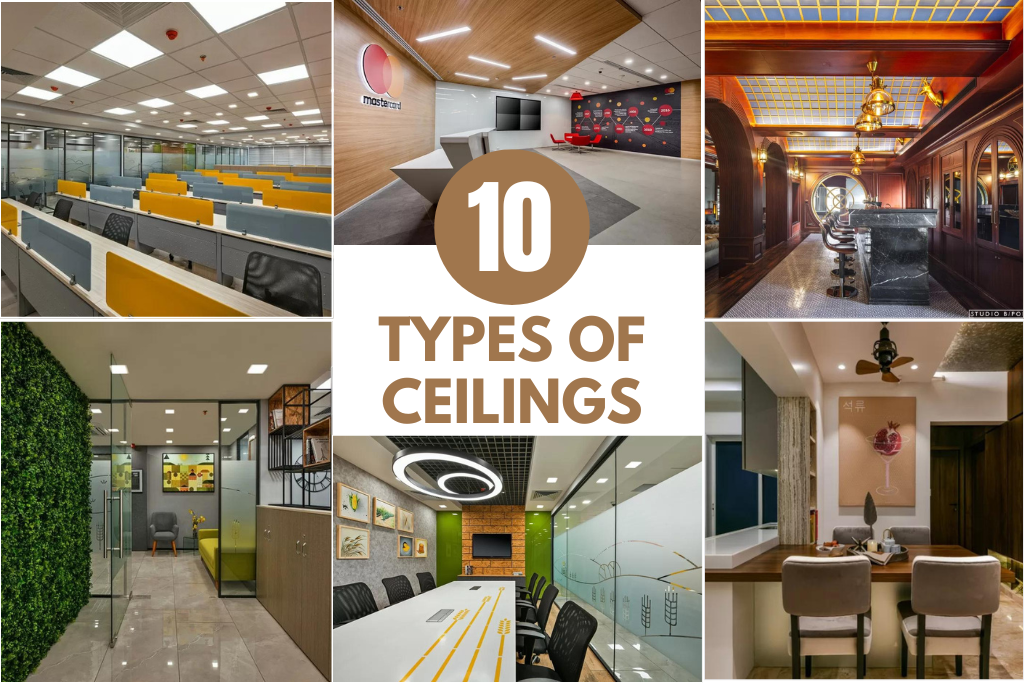

10 Types Of Ceilings That Elevates The Home

There are a lot of challenges that one faces while designing the interior of the house. One of which is giving the right choice of the types of ceilings. While looking out for the theme a house sets, the elements through which the theme is directed are also important. One such important element of the […]

50 Magnificent Gate Design That Will Protect Your Home

Gate Design is an important feature of any home. Numerous scopes for experimentation open up when delving into the design possibilities. Materials like wood and black steel are popular options in Indian homes. At the same time, designers also experiment with a combination of materials that suits their aesthetic. Buying mass-produced gate design has become […]

50 Refreshing Terrace Design Inspirations Essential for Urban Spaces

A rejuvenating terrace design is a breath of fresh air. One can experience the beauty of the outdoors from the comfort of their home. At the same time, a good terrace design can help one relax after a stressful day. It is a representation of one’s style and character. Terrace Design can seem minimalistic and semi-open or functional with a jacuzzi […]

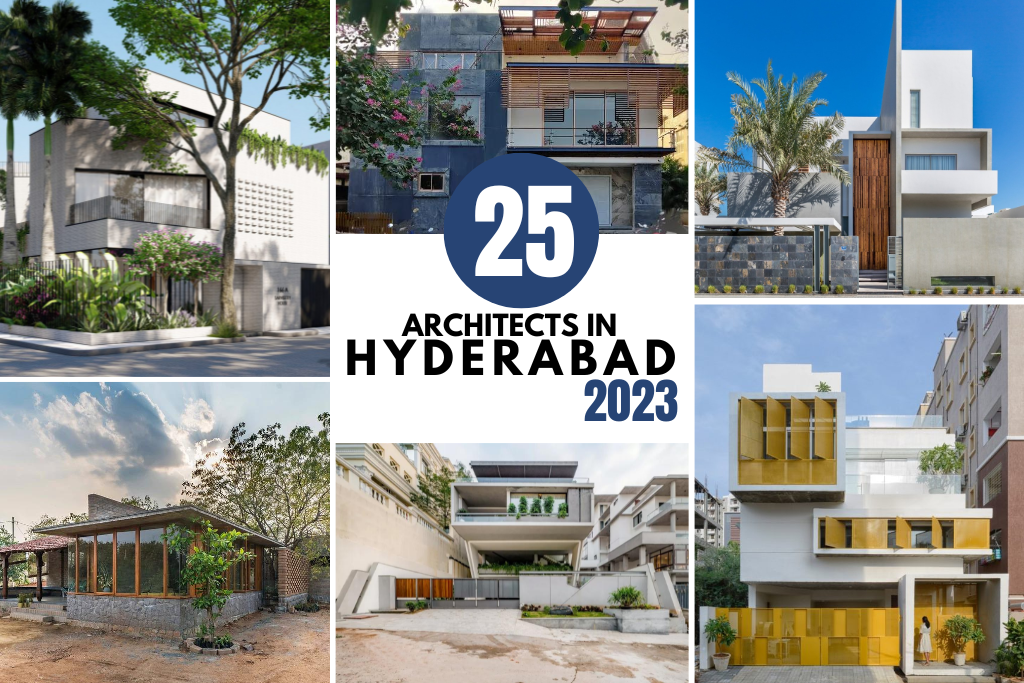

Top 25 Architects in Hyderabad

Hyderabad is a city that boasts a rich and diverse architectural heritage that has been shaped by its history and cultural influences. The city has been ruled by various dynasties, including the Qutb Shahis, the Mughals, and the Nizams, who have all left their mark on its architecture and influenced young architects in Hyderabad. The […]

TOP 25 INTERIOR DESIGNERS IN HYDERABAD

Hyderabad, the city of Nizams, is not just known for its rich cultural heritage but also for its booming interior design industry. With an increasing demand for quality and unique interior design solutions, the city has become a hub for talented and skilled interior designers in hyderabad who are making waves in the industry. In […]

Best 7 Tips Architecture College Student

How to Write a Resume for a Designer Position

- Login / Register

The AR looks beyond isolated buildings, commissioning in-depth theoretical essays that engage with the wider social, cultural and political context architecture sits in, as well as the impact and potential of architectural cultures and practices. Our writers include world-renowned critics, theorists, and architects, whose independent voices contribute to a thick-woven fabric of industrious longform journalism

Latest essays

Photo essay: life is a beach, in practice: daar on spatial justice in sicily and palestine, alberto ponis (1933–), salt of the earth: the past and future of building with brine, as far as the olive tree grows: unpacking the mediterranean diet, the long shadow of rome, regenerational divide: nicosia, cyprus, the mediterranean hypersea: mapping troubled waters, bodies of land: feminism and decolonisation, in practice: mycket on queerness, clubbing and architecture as the crowd, iwona buczkowska (1953–), angela davis (1944–), reparations as reconstruction, repairing allensworth, interview with kader attia, lin huiyin (1904–1955) and liang sicheng (1901–1972), retrospective: theaster gates, rebuilding gaza, in what style should we repair, who, where, when, why, what " rel="bookmark"> folio: who, where, when, why, what, editorial: open house, building coalition through contradictions: the sharjah architecture triennial 2023, dress rehearsal: chicago architecture biennial 2023, photo essay: the photographic work of francesca torzo, frames of reference: against the blank canvas, model matters: starting with found materials, tough competition: negotiating architecture contests, uneven playing fields: untold stories of starting a practice, back of a napkin: the enduring influence of an ephemeral sketch, forgotten history: a vision for palestinian refugees’ agricultural self-sufficiency, folio: ryue nishizawa’s desk, where to begin: ‘i started with coffee and cities’, editorial: first principles, donald judd (1928–1994), retrospective: khammash architects, apocalypse urbanism: cities for an uninhabitable world, dry ice: antarctica under review, desert dystopias: warnings from desertified worlds, interview with salma samar damluji, in practice: aziza chaouni on preserving morocco’s cultural heritage, border sands: policing in the sonoran desert, nuclear colonialism in maralinga, experimental saharanism: exploiting desert environments, folio: trafalgar road housing by james gowan, editorial: just deserts, return and resettlement: masterplan in ngarannam, nigeria by tosin oshinowo, imaginary property: artificial intelligence and design, cost of care: reflections on the skid row housing trust, the public housing paradox in singapore, this gameworld is yours: virtual exploitation, outrage: proptech, herman jessor (1894–1990), fiction: deeds, collective ownership against deforestation, cottage colonialism: lakeside property in ontario, in practice: architects against housing alienation on building an equitable housing system, typology: co-housing, property values: the enclosure of aotearoa new zealand, folio: stop hoarding housing by darren cullen, editorial: no trespassing.

City portraits

AR Reading Lists: weekly compilations of pieces old and new, free to read for registered users

Exhibitions

Gender and Sexuality

Photography

Postmodernism

Support the AR: join the conversation and stay safe at home with a subscription

Profiles and interviews

Reputations

Retrospective

Penguin Pool in London, UK by Tecton

‘architecture is now a tool of capital, complicit in a purpose antithetical to its social mission’, ‘complexity and contradiction changed how we look at, think and talk about architecture’, ‘pompidou cannot be perceived as anything but a monument’, architecture becomes music, auguste perret: the maverick grand old man of french architecture, belapur housing in navi mumbai, india by charles correa, dark matter: musée soulages in rodez by rcr arquitectes, empty gestures: starchitecture’s swan song, from the archive: british library in london by colin st john wilson and mj long, from the archive: moshe safdie’s habitat 67 in montreal, canada, how chicago, prototype of the modern city, was born, louis kahn: the space of ideas, lucien kroll and the dilemma of participation, memories of a bauhaus student, museum of contemporary art in niterói, rio de janeiro by oscar niemeyer, notopia: the singapore paradox and the style of generic individualism, outrage: dutch architecture no longer shows social imagination, outrage: future generations will laugh in horror and derision at the folly of facadism, outrage: the birth of subtopia will be the death of us, philip johnson’s at&t: the post post-deco skyscraper, principle v pastiche, perspectives on some recent classicisms, ronchamp chapel in france by le corbusier, sarah wigglesworth architects’ straw bale house, school at hunstanton, norfolk, by alison and peter smithson, the anatomy of wright’s aesthetic: inseparable from universal principles of form, the assembly, chandigarh, the interlace in singapore by oma/ole scheeren, the new brutalism by reyner banham, the strategies of mat-building, the ugly truth: the beauty of ugliness, thermal baths in vals, switzerland by peter zumthor, variations and traditions: the search for a modern indian architecture.

Since 1896, The Architectural Review has scoured the globe for architecture that challenges and inspires. Buildings old and new are chosen as prisms through which arguments and broader narratives are constructed. In their fearless storytelling, independent critical voices explore the forces that shape the homes, cities and places we inhabit.

Join the conversation online

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Architecture in renaissance italy.

Recto: Temple Types: in Antis and Prostyle (Vitruvius, Book 3, Chapter 2, nos. 2, 3); Verso: Temple Types: Peripteral (Vitruvius, Book 3, Chapter 2, no. 5).

Attributed to a member of the Sangallo family

Villa Almerico (Villa Rotunda), from I quattro libri dell'architettura di Andrea Palladio (Book 2, page 19)

Andrea Palladio

I quattro libri dell'architettura di Andrea Palladio. Ne'quale dopo un breue trattato de' cinque ordini (Book 2, page 19)

Department of European Paintings , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Italian Renaissance architects based their theories and practices on classical Roman examples . The Renaissance revival of classical Rome was as important in architecture as it was in literature. A pilgrimage to Rome to study the ancient buildings and ruins, especially the Colosseum and Pantheon, was considered essential to an architect’s training. Classical orders and architectural elements such as columns, pilasters, pediments, entablatures, arches, and domes form the vocabulary of Renaissance buildings. Vitruvius’ writings also influenced the Renaissance definition of beauty in architecture. As in the classical world, Renaissance architecture is characterized by harmonious form, mathematical proportion, and a unit of measurement based on the human scale .

During the Renaissance, architects trained as humanists helped raise the status of their profession from skilled laborer to artist. They hoped to create structures that would appeal to both emotion and reason. Three key figures in Renaissance architecture were Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, and Andrea Palladio.

Brunelleschi Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) is widely considered the first Renaissance architect. Trained as a goldsmith in his native city of Florence, Brunelleschi soon turned his interests to architecture, traveling to Rome to study ancient buildings. Among his greatest accomplishments is the engineering of the dome of Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore, also known as the Duomo). He was also the first since antiquity to use the classical orders Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian in a consistent and appropriate manner.

Although Brunelleschi’s structures may appear simple, they rest on an underlying system of proportion. Brunelleschi often began with a unit of measurement whose repetition throughout the building created a sense of harmony, as in the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Florence, 1419). This building is based on a modular cube, which determines the height of and distance between the columns, and the depth of each bay.

Alberti Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) worked as an architect from the 1450s onward, principally in Florence, Rimini, and Mantua. As a trained humanist and true Renaissance man, Alberti was as accomplished as an architect as he was a humanist, musician , and art theorist. Alberti’s many treatises on art include Della Pittura (On Painting), De Sculptura (On Sculpture), and De re Aedificatoria (On Architecture). The first treatise, Della Pittura , was a fundamental handbook for artists, explaining the principles behind linear perspective, which may have been first developed by Brunelleschi. Alberti shared Brunelleschi’s reverence for Roman architecture and was inspired by the example of Vitruvius, the only Roman architectural theorist whose writings are extant.

Alberti aspired to re-create the glory of ancient times through architecture. His facades of the Tempio Malatestiano (Rimini, 1450) and the Church of Santa Maria Novella (Florence, 1470) are based on Roman temple fronts. His deep understanding of the principles of classical architecture are also seen in the Church of Sant’Andrea (Mantua, 1470). The columns here are not used decoratively, but retain their classical function as load-bearing supports. For Alberti, architecture was not merely a means of constructing buildings; it was a way to create meaning.

Palladio Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) was the chief architect of the Venetian Republic, writing an influential treatise, I quattro libri dell’architettura (Four Books on Architecture, 1570; 41.100.126.19 ). Due to the new demand for villas in the sixteenth century, Palladio specialized in domestic architecture , although he also designed two beautiful and impressive churches in Venice, San Giorgio Maggiore (1565) and Il Redentore (1576). Palladio’s villas are often centrally planned, drawing on Roman models of country villas. The Villa Emo (Treviso, 1559) was a working estate, while the Villa Rotonda (Vicenza, 1566–69) was an aristocratic refuge. Both plans rely on classical ideals of symmetry, axiality, and clarity. The simplicity of Palladian designs allowed them to be easily reproduced in rural England and, later, on southern plantations in the American colonies .

Department of European Paintings. “Architecture in Renaissance Italy.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/itar/hd_itar.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Heydenreich, Ludwig H. Architecture in Italy, 1400–1500 . Rev. ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Hopkins, Andrew. Italian Architecture: From Michelangelo to Borromini . London: Thames & Hudson, 2002.

Lotz, Wolfgang. Architecture in Italy, 1500–1600 . Rev. ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Additional Essays by Department of European Paintings

- Department of European Paintings. “ The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity .” (October 2002)

- Department of European Paintings. “ Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) .” (originally published October 2004, last revised March 2010)

- Department of European Paintings. “ Titian (ca. 1485/90?–1576) .” (October 2003)

- Department of European Paintings. “ The Papacy and the Vatican Palace .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy

- The Idea and Invention of the Villa

- The Papacy and the Vatican Palace

- The Papacy during the Renaissance

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Architecture in Ancient Greece

- Baroque Rome

- Classical Antiquity in the Middle Ages

- Fontainebleau

- From Geometric to Informal Gardens in the Eighteenth Century

- The Grand Tour

- Italian Renaissance Frames

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- Medieval European Sculpture for Buildings

- The Neoclassical Temple

- Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe

- Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy

- Paintings of Love and Marriage in the Italian Renaissance

- Paolo Veronese (1528–1588)

- Profane Love and Erotic Art in the Italian Renaissance

- Renaissance Drawings: Material and Function

- Theater and Amphitheater in the Roman World

- Weddings in the Italian Renaissance

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- Architectural Element

- Architecture

- Central Italy

- Classical Ruins

- Colonial American Art

- Great Britain and Ireland

- High Renaissance

- Italian Literature / Poetry

- Literature / Poetry

- Musical Instrument

- Northern Italy

- Palladianism

- Printmaking

- Renaissance Art

- Southern Italy

Artist or Maker

- Palladio, Andrea

- Sangallo Family

Amazing Architecture

- {{ post.title }}

- No result found

- What Is Architecture: What to Cover in a Student's Short Ess...

What Is Architecture: What to Cover in a Student's Short Essay?

The word "architecture" may conjure up ideas for a person of a massive building with many floors and an impressive appearance. In actuality, architecture is so much more than that. If you are interested in learning about architecture, consider attending college and pursuing a degree in architecture, or you can buy architecture essays.

It is the art and science of creating buildings. The Greeks and Romans perfected this art form over thousands of years. Through their toil, architecture can be considered one of the most enduring arts practiced by humanity.

- Architecture

It is the art and science of designing buildings, structures, and spaces that meet the needs of people using them. Architecture originates from the Greek arkhitekton, or "master builder."

Architecture has been defined in different ways throughout history. It is a broad field of study that involves concepts such as engineering, aesthetics, functionality, and sustainability. Alternatively, architecture has been defined as the art and science of thinking about space, form, and scale to create functional structures within our environment.

Additionally, it can be described as a design, planning, and construction process that shapes our built environment to make it functional and beautiful while providing shelter against hazards such as weather or fire. For example, Luxury architecture is more than just a building. It's a lifestyle, a statement, and an experience.

In recent years there has been a shift in focus away from aesthetics toward sustainability. It is now widely accepted that buildings should be designed to meet aesthetic standards and promote good health for those who occupy them through passive heating and cooling strategies.

Architecture is a multi-faceted discipline with various sub-fields, including urban planning, interior design, industrial design, civil engineering, and environmental engineering. Moreover, it also includes construction management, landscape architecture, historic preservation, urban design, and structural dynamics.

Various Types of Architecture

Architecture is a broad discipline that can be divided into categories based on structure, location, or use. These include residential architecture, commercial architecture, industrial architecture, and many more.

1. Domestic Architecture

This type of architecture is the one that we use in our homes, offices, and other public places. The primary purpose of this type of architecture is to make our lives comfortable.

2. Vernacular" Architecture

The term vernacular refers to an area's native or indigenous style, often associated with rural regions or minority groups within a country. This architecture is not meant for people with high income but is made so that they can live comfortably with their family members and friends in their own house.

3. Religious Architecture

Religious architecture is the art and craft of designing places of worship such as churches, synagogues, or mosques; any structure is intended to perform religious rituals and ceremonies.