THE DEPRESSION

Everyone was so shocked and panicky. No one knew what was ahead. — Dorothea Lange

THE DEPRESSION Topics

Discovering a Purpose: Early Documentary Work

The Dust Bowl

On the Road

In the Camps

In the Fields

Deep South: Picturing Race and Power

An American Exodus: A New Kind of Book

Migrant Mother: Birth of An Icon

Previous Section

EARLY WORK / PERSONAL WORK

Next Section

WORLD WAR II AT HOME

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Real Story Behind the ‘Migrant Mother’ in the Great Depression-Era Photo

By: Sarah Pruitt

Published: May 8, 2020

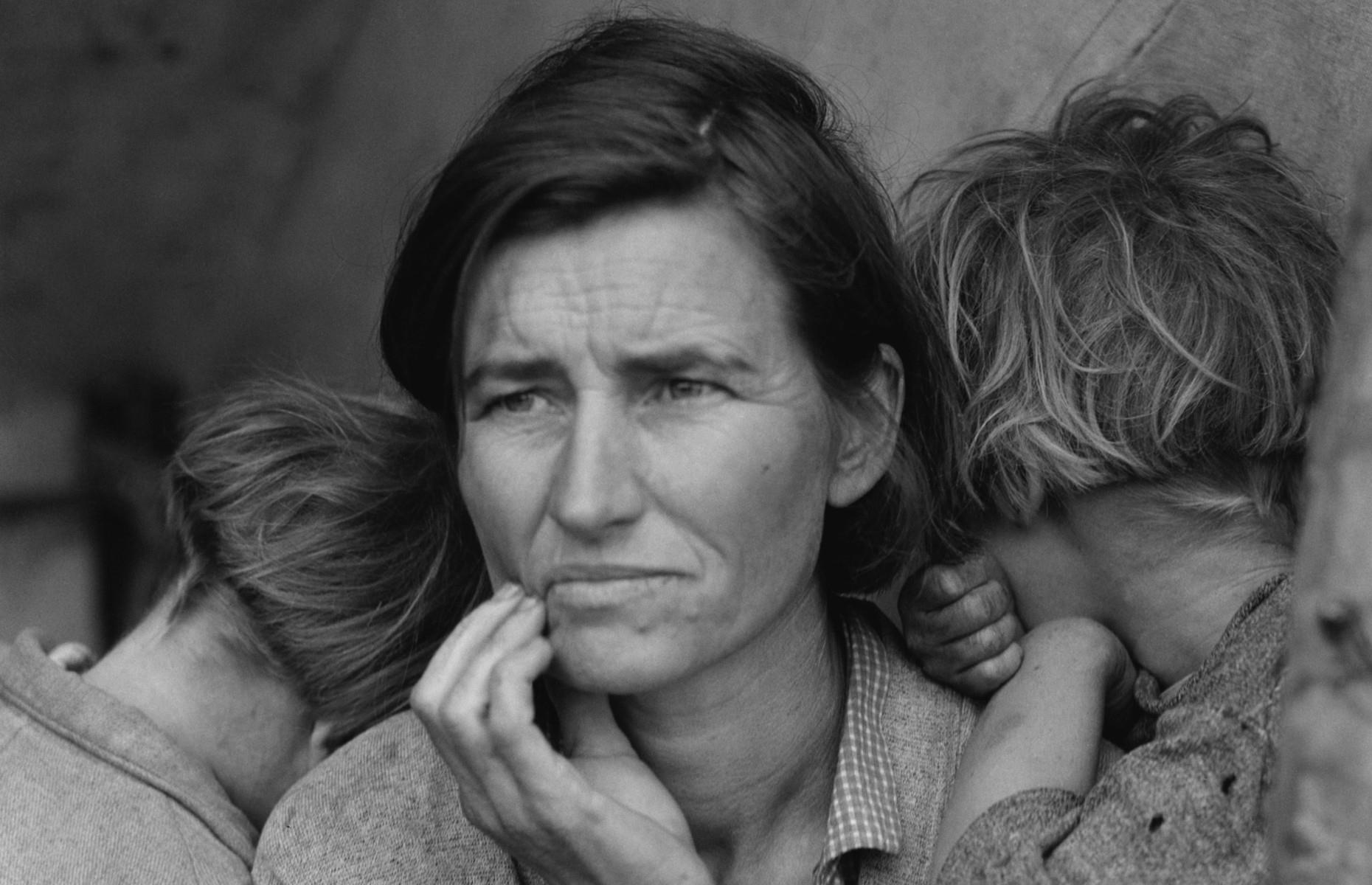

It’s one of the most iconic photos in American history. A woman in ragged clothing holds a baby as two more children huddle close, hiding their faces behind her shoulders. The mother squints into the distance, one hand lifted to her mouth and anxiety etched deep in the lines on her face.

From the moment it first appeared in the pages of a San Francisco newspaper in March 1936, the image known as “Migrant Mother” came to symbolize the hunger, poverty and hopelessness endured by so many Americans during the Great Depression . The photographer Dorothea Lange had taken the shot, along with a series of others, days earlier in a camp of migrant farm workers in Nipomo, California.

Lange was working for the federal government’s Resettlement Administration—later the Farm Security Administration (FSA)—the New Deal -era agency created to help struggling farm workers. She and other FSA photographers would take nearly 80,000 photographs for the organization between 1935 to 1944, helping wake up many Americans to the desperate plight of thousands of people displaced from the drought-ravaged region known as the Dust Bowl .

How the Photo Was Taken

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother as if drawn by a magnet,” Lange told Popular Photography magazine in 1960 . She had spotted a sign for the migrant workers’ campsite driving north on Highway 101 through San Luis Obispo County, some 175 miles north of Los Angeles. Bad weather had destroyed the local pea crop, and the pickers were out of work, many of them on the brink of starvation.

Lange didn’t ask the woman’s name, or find out her history. She claimed the woman told her she was 32, that she and her children were living on frozen vegetables and birds the children had killed, and that she had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.

Soon after the photos were published in the San Francisco News , the U.S. government announced it was sending 20,000 pounds of food to the pea-pickers’ campsite. But by the time it arrived, the still-anonymous woman and her family had moved on. Even as her image was widely reprinted and reproduced on everything from magazine covers to postage stamps, the “Migrant Mother” herself appeared to have vanished.

The Real ‘Migrant Mother’

Then in 1978, a woman named Florence Owens Thompson wrote a letter to the editor of the Modesto Bee newspaper. She was the mother in the famous “Migrant Mother” photo, Thompson said—and she wanted to set the record straight.

In an Associated Press article that followed, titled “Woman Fighting Mad Over Famous Depression Photo,” Thompson told a reporter that she felt “exploited” by Lange’s portrait. As Geoffrey Dunn wrote in the San Luis Obispo New Times in 2002 , Thompson and her children disputed other details in Lange’s account and sought to dispel the image of themselves as stereotypical Dust Bowl refugees.

Born in Oklahoma, Thompson was actually a full-blooded Native American; both her parents were Cherokee. In the mid-1920s, she and her first husband, Cleo Owens, moved to California, where they found mill and farm work. Cleo died of tuberculosis in 1931, and Florence was left to support six children by picking cotton and other crops.

When Bill Ganzel, a photographer for Nebraska Public Television, interviewed and photographed Thompson in 1979, she told him that while a young mother, she typically picked around 450-500 pounds of cotton a day, leaving home before daylight and coming home after dark. “We just existed,” she said. “We survived, let’s put it that way.”

When Lange found her in Nipomo that day in March 1936, she had two more children and was living with a man named Jim Hill, the father of her infant daughter Norma. After their car broke down on the way to find work picking lettuce, the family had been forced to pull off into the pea-pickers’ camp.

Two of Florence’s older sons were in town when the iconic picture was taken, getting the car’s radiator fixed. One of them, Troy Owens, flatly denied that his mother had sold their tires to buy food, as Lange had claimed. “I don’t believe Dorothea Lange was lying, I just think she had one story mixed up with another,” Troy told Dunn . “Or she was borrowing to fill in what she didn’t have."

Life After the Famous Photo

The family kept moving after Nipomo, following farm work from one place to another, and Florence would have three more children. After World War II , she settled in Modesto, California and married George Thompson, a hospital administrator.

By 1983, five years after claiming her identity as the “Migrant Mother,” Thompson was living alone in a trailer. She suffered from cancer and heart problems, and at one point her children had to solicit donations for her medical expenses. According to Dunn, thousands of letters poured in, along with more than $35,000 in contributions.

Florence Owens Thompson died in September 1983, just after her 80th birthday, ending a life marked by economic hardship, maternal sacrifice and human dignity.

Even President Ronald Reagan offered his condolences , writing that “Mrs. Thompson's passing represents the loss of an American who symbolizes strength and determination in the midst of the Great Depression.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Dorothea Lange's Moving Photographs of The Depression Era

Editorial feature.

By Google Arts & Culture

Words by Rebecca Fulleylove

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco (1933) by Dorothea Lange San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

Meet the woman who showed America the consequences of the Great Depression

1. White Angel Breadline , San Francisco, 1933

White Angel Breadline, San Francisco by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

2. Migrant Mother , Nipomo, California, 1936

Migrant Mother, Nipoma, California (1936, printed 1976) by Dorothea Lange The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

3. Damaged Child, Shacktown , Elm Grove, Oklahoma, 1936

Damaged Child, Shacktown, Elm Grove, Oklahoma (1936) by Dorothea Lange George Eastman Museum

Damaged Child, Shacktown, Oklahoma by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of George Eastman Museum)

4. Ex-Slave With Long Memory , Alabama, 1937

Ex-Slave with Long Memory, Alabama (1937) by Dorothea Lange George Eastman Museum

Ex-Slave With Long Memory, Alabama by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of George Eastman Museum)

5. Six Tenant Farmers Without Farms , Hardeman County, Texas, 1937

Six Tenant Farmers without Farms, Hardeman County, Texas (May 1937, printed 1976) by Dorothea Lange The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Six Tenant Farmers Without Farms by Dorothea Lange (From the collection of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

Explore more: – 7 Gordon Parks Images That Changed American Attitudes

The Usable Past: Reflections on American History 2000–2017

The museum of fine arts, houston, eastman: the inventor, george eastman museum, passion for perfection: the straus collection of renaissance art, cameras + fashion, space city: photographs from the museum of fine arts, houston, a renaissance couple, latino experience in the usa: works from the mfah collection, funny faces, #5womenartists, artistic genus: depictions of animals in the collections of the museum of fine arts, houston.

- 1865-1925: Hunger in the Industrial City

- 1929-1940: America in Crisis and Recovery

- 1945-1965: WWII and the Paradoxes of the Postwar Era

- 1955-1980: The Fight for the Right for Food

- 1975-1996: The Unmaking of the Great Society

- 1997-Present: How It Is — And How It Should Be

- Museum Lobby

- The Wishing Tree

- The SNAP Café

- Terrace Restaurant

- Get Involved

- Book a Tour

- Leave your Wish

- Patron Program

- Educational Curriculum

- The Hunger Museum

- About MAZON

- In the News

“To live a visual life is an enormous undertaking, practically unattainable, but when the great photographs are produced, it will be down that road. I have only touched it, just touched it.” – Dorothea Lange, 1965

Dorothea Lange: Documenting the Great Depression

A new deal for hungry americans, the food stamp program.

Dorothea Lange moved to San Francisco in 1918, where she started her career as a portrait photographer, drawing a mostly elite clientele. After the collapse of the stock market, her business declined. She left her studio to photograph the devastating impacts of the Depression. Her photographs caught the eye of Paul Taylor, an agricultural economist at the University of California, Berkeley, who hired Lange to work for the California State Emergency Relief Administration in 1935 and later encouraged colleagues in the Farm Security Administration to do the same. Lange soon married Taylor, beginning their years-long partnership.

Lange’s first assignment was for the California State Emergency Relief Administration, investigating the conditions of migrant farmers. Farm work in California had long relied on migrant labor, but Lange found the fields populated by an increasing number of “Dust Bowl refugees” — displaced tenant farmers and smallholders from the plains desperately seeking work out west. She documented the appalling conditions of these families, not only by taking intimate portraits, but also by adding captions that described their experiences. Lange’s most famous work is representative of this period, known today as “Migrant Mother.”

While Lange’s annotations often reflected long conversations with her subjects, her caption for “Migrant Mother” was a gross misrepresentation. The woman in the photograph, Florence Owens Thompson, later revealed that her family were not recent migrants. They had lived in the state for years and were simply passing through Nipomo when their car broke down. Although she became the quintessential “Okie,” Thompson was not an Oklahoma refugee of the Dust Bowl but rather a member of the Cherokee Nation whose husband was in town with their older children at the time buying car parts.

Davis, Lennard J. “Migrant Mother: Dorothea Lange and the Truth of Photography,” Los Angeles Review of Books, March 4, 2020.

“Migrant Mother” was often in the newspaper, alongside a series about the pea pickers’ camp. The image and related articles helped rally concern for conditions in the camp, prompting the State Relief agency to send vital food assistance. But Florence Owens Thompson’s family did not benefit from that aid, nor did they feel appropriately compensated. Thompson wrote to Lange, asking that she remove the image from circulation. “Migrant Mother” serves as a reminder to consider the social relations between photographers and their subjects, the limits of photography as advocacy, and the ethical stakes of documenting poverty and hunger.

Davis, Lennard J. “Migrant Mother: Dorothea Lange and the Truth of Photography, Los Angeles Review of Books , March 4, 2020.

This photo and its caption demonstrate Lange’s ethnographic process. The photograph appears to have been taken impromptu rather than staged as a formal portrait, as the mother looks away towards her other child rather than at the camera. But clearly, Lange spent time with this family discussing their experiences. The details also suggest the message Lange wanted to convey to policy-makers — that this family ended up in this situation through no fault of their own, and they were worthy of help and support, even when they didn’t want to ask.

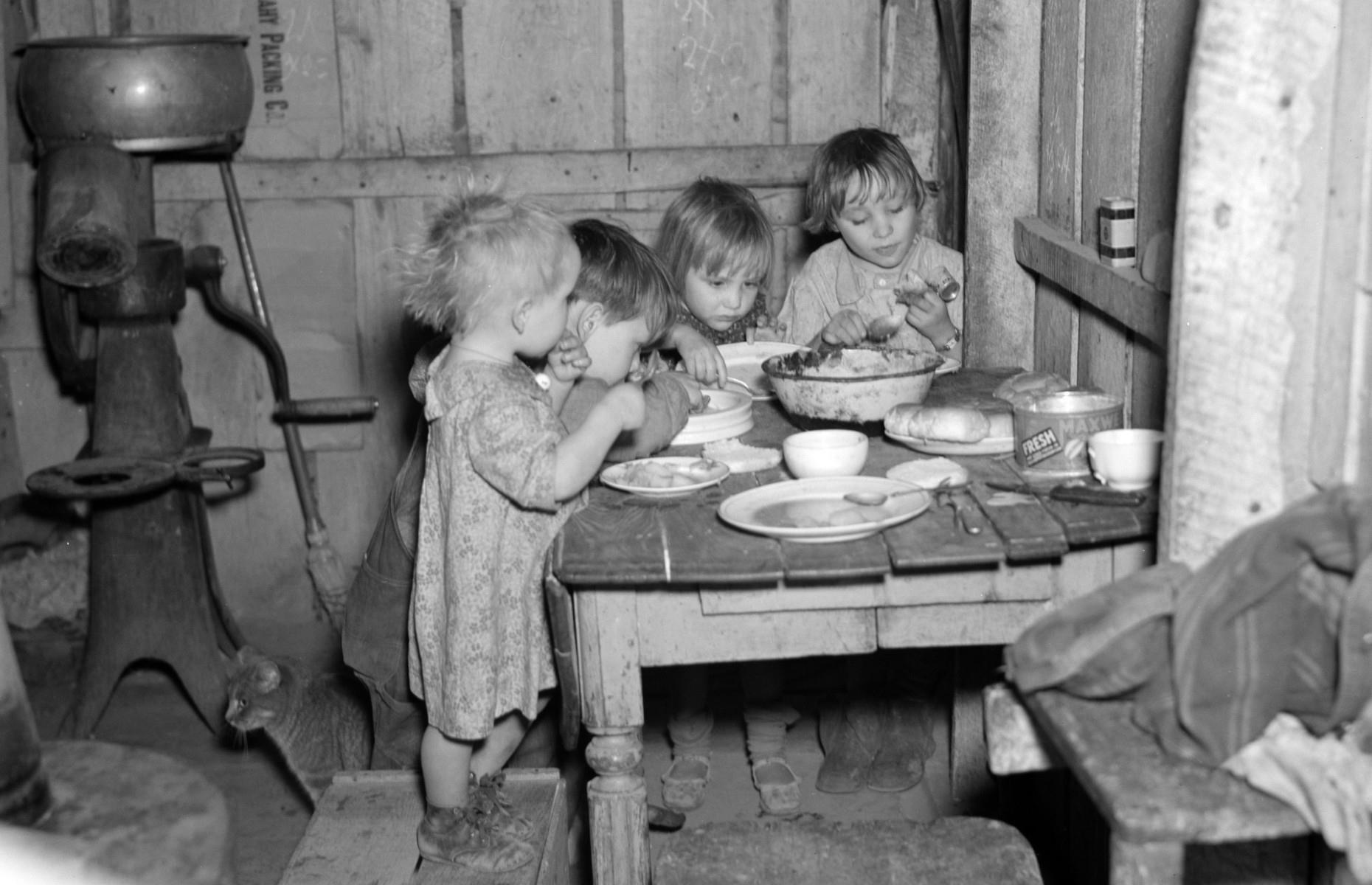

While many of Lange’s photos depicted moments of misery and hardship, others captured more familiar scenes of domestic family life. Her photographs of families displaced by the Dust Bowl were often taken at meal times, revealing how the families cooked and ate on the road. Here, she even caught glimpses of the communal value that family meals could bring in spite of harsh surroundings.

The bulk of Lange’s work in California focused on documenting agricultural labor. Her photographs aimed to illuminate not only the day-to-day realities faced by farmworkers but also the economic and racial systems in which those workers operated and the inequities those systems reinforced. Lange took nearly 200 photographs of the production of California’s crops, including some photos of workers picking cotton and peas, pulling carrots, and cutting lettuce and cabbage. Images like this provided new portraits of the migrant laborers, including those of Mexican, Japanese, and Filipino descent, who made California’s agricultural economy possible.

Gordon, Linda. “Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist,” Journal of American History, 93, 3 (Dec. 2006): 706.

While Lange often hid the faces of agricultural workers in her photographs, others offered glimpses of children and older individuals to challenge popular impressions of who did farm work. These photographs reveal the intergenerational dynamics of farm communities. But unlike her other portraits, Lange’s photos of migrant farm workers did not include extensive captions, suggesting that she did not have long conversations with those families.

In 1936, Lange and Taylor traveled to the southern Great Plains to observe the displacement crisis of the Dust Bowl at its source. While highly critical of the ecological devastation wrought by over-farming and poor land-stewardship practices, Taylor was equally concerned by the large-scale commercial farms replacing smaller, family-owned ones and, in particular, by the plight of the tenant farmers who worked them. In Oklahoma and North Texas, Lange’s photographs captured both the parched, abandoned fields and the poverty and hardship that resulted, offering intimate portraits of farm communities impacted by the Dust Bowl.

When photographing farm families displaced from the plains, Lange seemed particularly interested in pointing to the hardships that predated the Dust Bowl. In Texas, she highlighted the experiences of tenant farmers in particular, who had long been mistreated by landowners. While often subtle in their critique, images like this highlight both the urgent material needs of farm families and the deeper inequities endemic in the American agricultural system.

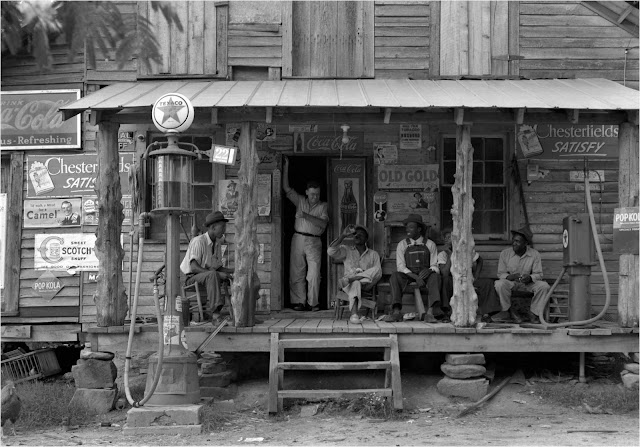

Between 1936 and 1939, Lange and Taylor traveled extensively throughout the Jim Crow South, confronting a type of poverty and racial stratification that they — like many Americans — had never seen before. While Lange did not document specific acts of racial violence, her photographs and notes captured the subtle ways that white supremacy manifested in social and economic relations in rural communities, the endurance of plantation capitalism, and the deep racial hierarchies that structured day-to-day life.

Lange sought to document and expose all aspects of the racial caste system of the Jim Crow South. So, too, did she capture more quiet moments of interracial intimacy and camaraderie. Compared to other regions where she documented the impacts of farm mechanization and industrialization, her photographs in the South often showcased a world untouched by modern life and haunted by its past.

Labor Exploitation in the Jim Crow South

Lange’s primary interest in the South was in documenting the economic relations that both shaped and were shaped by the Jim Crow system. Her photographs captured every aspect of the southern agricultural economy, describing in detail the hiring systems, crop liens and debt servitude system, and abysmal wages through which white planters exploited Black workers. Her work focused on three primary crops — cotton, tobacco, and turpentine — recording every step in the process from start to finish, revealing them not simply as commodities but as products of human labor that were largely hidden from view.

Lange’s photographs in the South focused on housing and the appalling racial inequities. As with her photographs of Asian and Mexican farmworkers in California, her depictions of Black farmers included intergenerational families to demonstrate their deep ties to the land. Her portraits of Black family homes — always taken on the exterior of their dwellings — aimed not simply to showcase the conditions in which they lived but also to lift up their dignity, pride, and resilience, positioning them as equally deserving of full and equal rights for a white audience.

Over the course of their work together, Lange and Taylor became strong advocates for housing assistance and other relief programs that improved the lives of agricultural workers and their families. Most often, their appeals for federal intervention were implicit, expressed in the ways that Lange staged and framed her photographs. Still, in some cases, she made them more explicit in both the composition of her photographs and in her captions.

As a strong believer in the need for government intervention and support for struggling farmworkers, Lange sought to document how relief programs were (and were not) reaching those in need. Many of her photographs featured those seeking aid in rural areas, showcasing both the scale of the need and how the government implemented assistance programs in small towns.

Lange sought not only to document government assistance programs but also how farm communities organized to support one another through crisis — including mutual aid efforts, cooperative ventures, and community organizing. Of particular interest was the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, a first-of-its-kind interracial organization that helped sharecroppers and tenant farmers hit hard by the Depression. Union members worked together to fight evictions, demanding a more equitable share of the profits their labor produced. In addition to photographing union members, Lange tried to capture the vicious harassment and violence they faced.

After many years on the road with the U.S. government’s Farm Security Administration (FSA), Lange was awarded the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1941. But shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she gave up the fellowship to take an assignment with the War Relocation Authority to document the forceful evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans. Lange’s photographs of the evacuation captured the hardships and painful experiences of evacuated families, illuminating the contradictory meanings of American citizenship and belonging during World War II.

Lange’s most intimate portraits from her work with the War Relocation Authority (WRA) were those of families, particularly women and children. Here, too, she aimed to capture both hardship and resilience, framing her subjects in ways that evoked empathy and, perhaps, stirred collective action. But unlike her previous works, her photographs documenting internment were not made publicly available as the WRA impounded them until after the war. Their impact instead came later, providing a poignant archive of a shameful chapter in American history.

Lange continued to work as a photographer after the war, teaching, publishing, traveling, and holding exhibitions. Her photographs often explored how California was growing and changing in the post-war years, capturing new construction and veterans re-adjusting to civilian life. She died in 1965, years before many of her photographs were ever publicly displayed.

The ethnographic import and historical context illuminated in Lange’s work are significant. The many migrant mothers she captured in her photographs in the 1930’s provide a unique and indelible portrait of American life that continues to inform how we understand the Depression to this day.

Lange spent significant time with her subjects, earning their trust, learning about them, and staging the scene. But when her works were displayed, these captions were sometimes left out, contributing to the common perception that her work reflected her “natural” eye or “feminine intuition” for capturing intimate emotions. Biographer Linda Gordon suggests such gendered assumptions belie the thoughtfulness and expertise Lange brought to her work: “far from being passively receptive, she was an assertive visual intellectual, […] working systematically to develop a photography that could be maximally communicative and revealing.”

Gordon, Linda. “Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist,” Journal of American History, 93, 3 (Dec. 2006): 696-727. See also Lennard J. Davis, “Migrant Mother: Dorothea Lange and the Truth of Photography,” Los Angeles Review of Books, March 4, 2020.

Established in 1935, the U.S. government’s Resettlement Agency was tasked with improving the lives of poor farmers, particularly those displaced by drought and the Dust Bowl. The agency’s “Information Division” documented the plight of farm families to promote the agency’s work.

With the goal of “introducing America to Americans,” the Agency’s photographers — including Dorothea Lange — offered intimate portraits of the everyday lives of millions of Americans struggling to survive the Depression. Lange’s photography fundamentally changed how Americans imagined poverty and hunger. Along with her husband Paul Taylor, she traveled across the country documenting rural communities. While taken in a journalistic, documentary style, Lange’s photos were intentionally composed to raise concern among political leaders and urbanites about the plight of farm families, the injustices of the agricultural political economy, and the racial exploitation upon which it was based.

Dorothea Lange interviewed by Peter Odergard in The Closer for Me, Part II, WNET Public Broadcasting, 1965. Linda Gordon, “Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist,” Journal of American History, 93, 3 (Dec. 2006): 696-727. See also Lennard J. Davis, “Migrant Mother: Dorothea Lange and the Truth of Photography,” Los Angeles Review of Books , March 4, 2020.

Dorothea Lange helped create a “visual encyclopedia” of the Depression that fundamentally changed how Americans imagined hunger. Explore the map to discover how Lange documented the plight of rural communities across the country.

Galleries & Exhibits

Great Depression Project

Main pages and sections.

- BROWSE SITE CONTENT

- Video: Great Depression in Washington State

- Labor events yearbooks 1930-1939

- Brief history in chapters

- Economics and poverty

- Hoovervilles and homelessness

- Everyday life

- Strikes & unions

- Radicalism - special section

- Civil Rights and racial politics

- Public works

- Art & Culture

- Visual Arts

- Theatre Arts

- Unemployed Citizens League and poverty action

- Washington Commonwealth Federation

Select Articles

- University of Washington

- Hunger marches

- Bank crisis 1933

- Berry Lawson murder case

- Dorothea Lange Yakima photos

- Building Grand Coulee dam

- Japanese American community in early 1930s

- Jewish women in Seattle

- New Order of Cincinnatus

- Ronald Ginther watercolors

Dorothea Lange's Yakima Valley Photographs

The Farm Security Administration commissioned Dorothea Lange to document the conditions of migrant farm workers and FSA programs and clients in Washington's Yakima Valley in 1939. Lange had previously photographed migrant workers in California and rural poverty in Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas. Here are some of Lange's Yakima photographs, culled from the Library of Congress American Memory photograph archives. Click the image to enlarge and read her full captions. Click here to see the full gallery of her Yakima pictures .

Dorothea Lange's 1939 Yakima Valley photographs. Click to see full collection and enlarge images.

- How to cite and copyright information

- About the project

- Contact James Gregory

The Story Behind the Iconic “Migrant Mother” Photograph and How Dorothea Lange Almost Didn’t Take It

By maria popova.

Among the biographical sketches is also the story of Lange’s best-known, infinitely expressive, most iconic photograph of all — Migrant Mother , depicting an agricultural worker named Florence Owens Thompson with her children — which came to capture the harrowing realities of the Great Depression not merely as an economic phenomenon but as a human tragedy.

In 1935, Lange and her second husband, the Berkeley economics professor and self-taught photographer Paul Taylor, were transferred to the Resettlement Administration (RA), one of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs designed to help the country recover from the depression. Lange began working as a Field Investigator and Photographer under Roy Stryker, head of the Information Division.

In early February of 1936, while living in a small two-bedroom house in California with Taylor and her two step-children, Lange received an assignment to photograph California’s rural and urban slums and farmworkers. She was supposed to spend a month on the road, but severe weather along the coast delayed her departure. When she finally set out for Los Angeles, the first destination on her route, she wrote in a letter to Stryker:

Tried to work in the pea camps in heavy rain from the back of the station wagon. I doubt that I got anything. . . . Made other mistakes too. . . . I make the most mistakes on subject matter that I get excited about and enthusiastic. In other words, the worse the work, the richer the material was.

It was in the pea camps that she captured her most iconic image less than two weeks later — an image that, due to its unshakable grip of empathy, would transcend the status of mere visual icon and effect critical cultural awareness on both a social and political level. Partridge writes:

Two weeks of sleet and steady rain had caused a rust blight, destroying the pea crop. There was no work, no money to buy food. Dorothea approached “the hungry and desperate mother,” huddled under a torn canvas tent with her children. The family had been living on frozen vegetables they’d gleaned from the fields and birds the children killed. Working quickly, Dorothea made just a few exposures, climbed back in her car, and drove home. Dorothea knew the starving pea pickers couldn’t wait for someone in Washington, DC to act. They needed help immediately. She developed the negatives of the stranded family, and rushed several photographs to the San Francisco News . Two of her images accompanied an article on March 10th as the federal government rushed twenty thousand pounds of food to the migrants.

The most remarkable part of the story, however, is that this was an image Lange almost didn’t take: At the end of that cold and wretched winter, she had been on the road for almost a month, with only the insufficient protection of her camera lens between her and the desperate, soul-stirringly dejected living and working conditions of California’s migratory farm workers. Downhearted and weary, both physically and psychologically, she decided she had seen and captured enough, packed up her clunky camera equipment, and headed north on Highway 101, bickering with herself in her notebook: “Haven’t you plenty of negatives already on the subject? Isn’t this just one more of the same?” But then something happened — a fleeting glance, one of those pivotal chance encounters that shape lives . Partridge transports us to that fateful March day:

The cold, wet conditions of Northern California gave way to sweltering heat in Los Angeles, a “vile town,” Dorothea wrote. By the beginning of March she was headed home, exhausted, her camera bags packed on the front seat beside her. Hours later, the hand-lettered “Pea pickers camp” sign flashed by her. Did she have it in her to try one more time? She did. The long, hard rains that had delayed Dorothea at the outset of her journey had deluged the Nipomo pea pickers. And even as Dorothea drove north and homeward, the camp was still floundering in water and mud. Not long before Dorothea arrived, Florence Thompson and four of her six children, along with some of the other stranded migrants, had moved to a higher, sandy location nearby. Thompson left word at the first camp for her partner, Jim Hill, on where to find them. Earlier in the day he’d set off walking with Thompson’s two sons to find parts for their broken-down car. The sandy camp in front of a windbreak of eucalyptus trees is where Dorothea pulled in and found Florence Thompson and her children. They were waiting for Hill and the boys to show up, for the ground to dry, for crops to ripen for harvesting. They were waiting for their luck to change. In minutes, Dorothea took the photograph that would become the definitive icon of the Great Depression, intuitively conveying the migrants’ perilous predicament in the frame of her camera.

Complement Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning , illuminating in its entirety, with this excellent short film on the power of photojournalism and Susan Sontag on the violence of photography .

Images courtesy of Chronicle Books

— Published November 6, 2013 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2013/11/06/dorothea-lange-migrant-mother-elizabeth-partridge/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture dorothea lange history photography, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

The Story of the Great Depression in Photos

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

- B.A., History, University of California at Davis

This collection of pictures of the Great Depression offers a glimpse into the lives of Americans who suffered through it. Included in this collection are pictures of the dust storms that ruined crops, leaving many farmers unable to keep their land. Also included are pictures of migrant workers—people who had lost their jobs or their farms and traveled in the hopes of finding some work. Life was not easy during the 1930s, as these evocative photos make plain.

Migrant Mother (1936)

George Eastman House Collection/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

This famous photograph is searing in its depiction of the utter desperation the Great Depression brought to so many and has become a symbol of the Depression. This woman was one of many migrant workers picking peas in California in the 1930s to make just enough money to survive.

It was taken by photographer Dorothea Lange as she traveled with her new husband, Paul Taylor, to document the hardships of the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration.

Lange spent five years (1935 to 1940) documenting the lives and hardships of the migrant workers, ultimately receiving the Guggenheim Fellowship for her efforts.

Less known is that Lange later went on to photograph the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II .

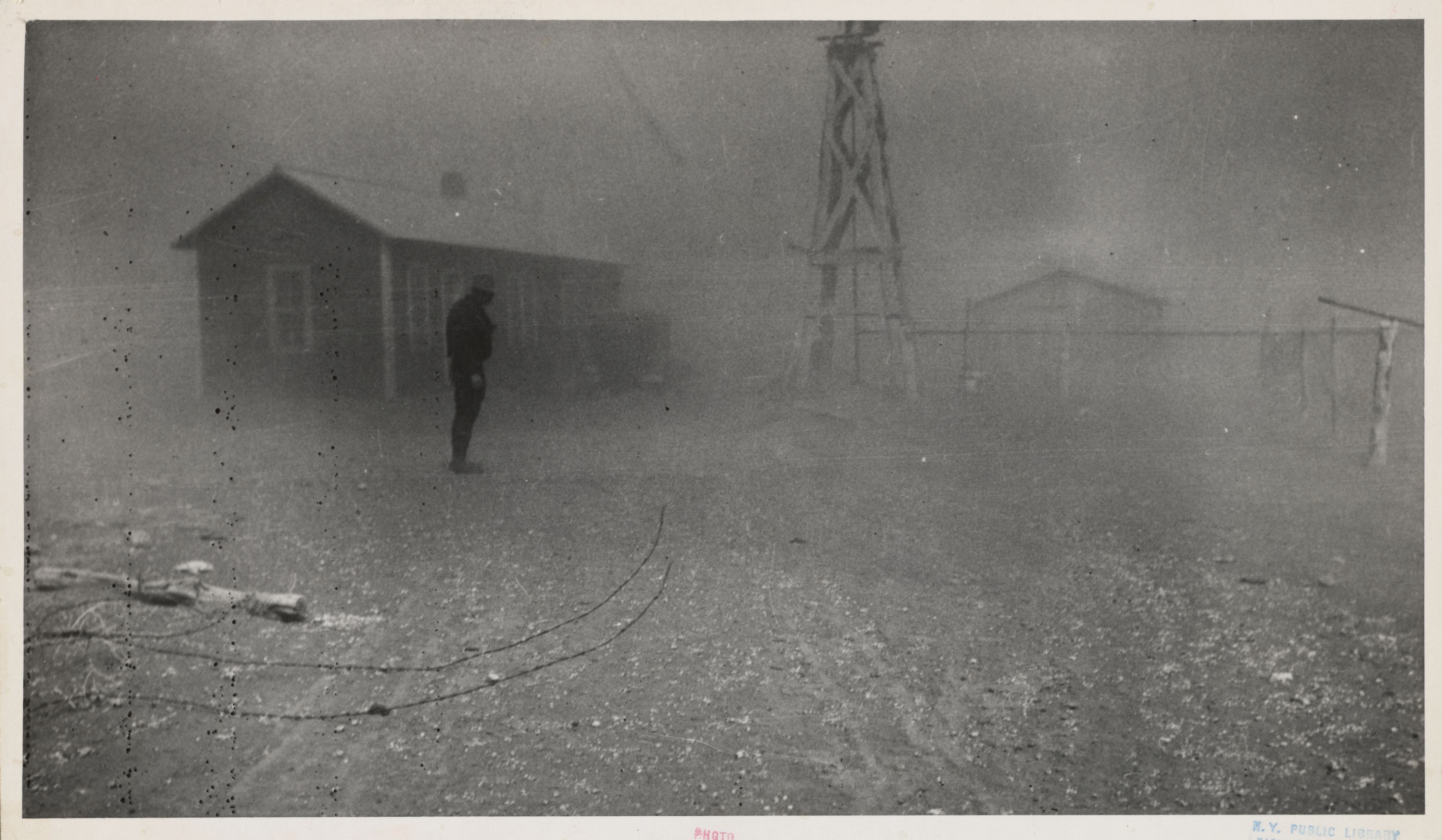

The Dust Bowl

Picture from the FDR Library, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Hot and dry weather over several years brought dust storms that devastated the Great Plains states, and they came to be known as the Dust Bowl . It affected parts of Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado and Kansas. During the drought from 1934 to 1937, the intense dust storms, called black blizzards, caused 60 percent of the population to flee for a better life. Many ended up on the Pacific Coast.

Farms for Sale

Picture from the FDR Library, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The drought, dust storms, and boll weevils that attacked Southern crops in the 1930s, all worked together to destroy farms in the South.

Outside the Dust Bowl, where farms and ranches were abandoned , other farm families had their own share of woes. Without crops to sell, farmers could not make money to feed their families nor to pay their mortgages. Many were forced to sell the land and find another way of life.

Generally, this was the result of foreclosure because the farmer had taken out loans for land or machinery in the prosperous 1920s but was unable to keep up the payments after the Depression hit, and the bank foreclosed on the farm.

Farm foreclosures were rampant during the Great Depression.

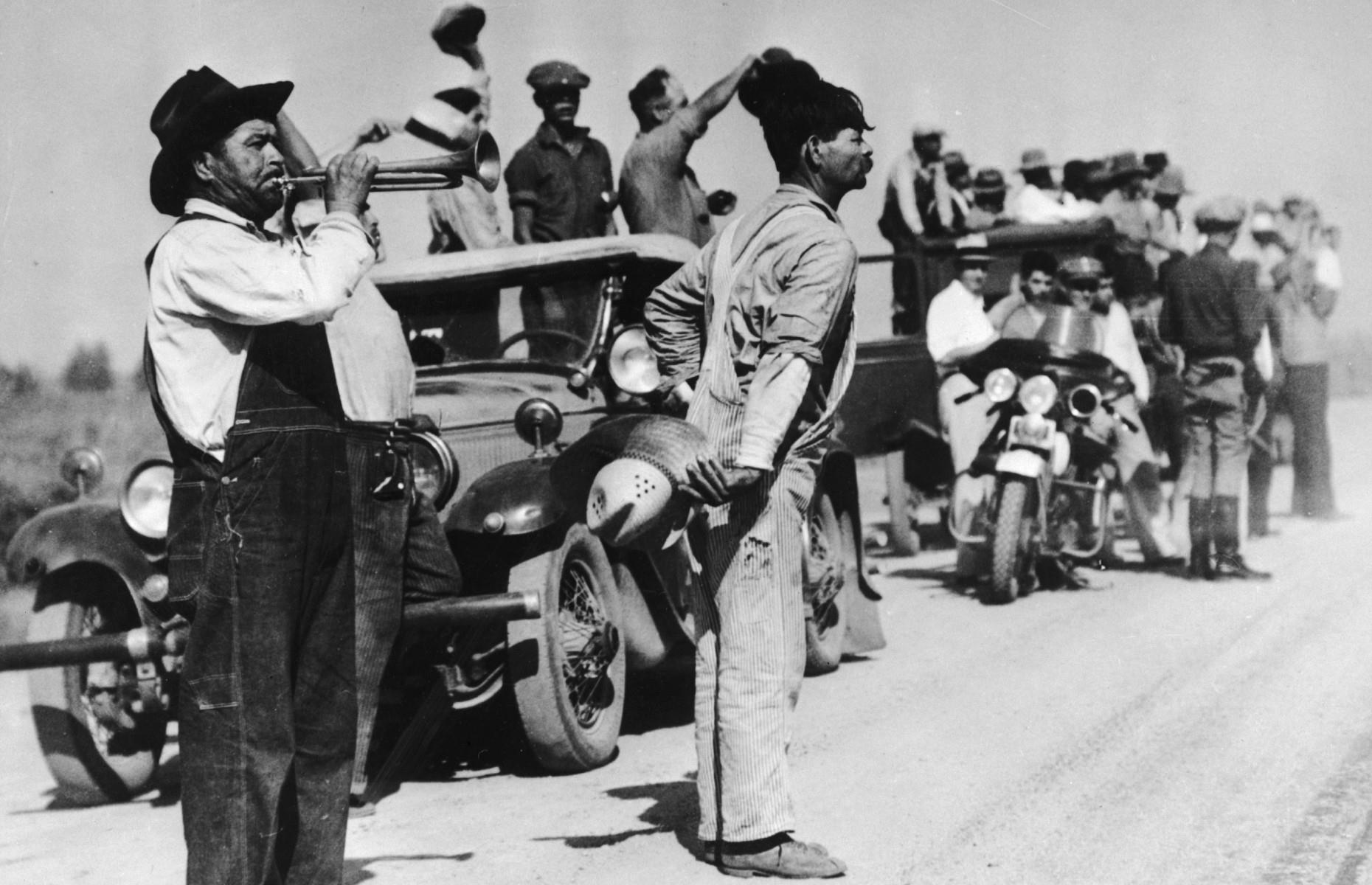

Relocating: On the Road

Picture by Dorothea Lange, from FDR Library, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The vast migration that occurred as the result of the Dust Bowl in the Great Plains and the farm foreclosures of the Midwest has been dramatized in movies and books so that many Americans of later generations are familiar with this story. One of the most famous of these is the novel " The Grapes of Wrath " by John Steinbeck, which tells the story of the Joad family and their long trek from Oklahoma's Dust Bowl to California during the Great Depression. The book, published in 1939, won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a movie in 1940 that starred Henry Fonda.

Many in California, themselves struggling with the ravages of the Great Depression, did not appreciate the influx of these needy people and began calling them the derogatory names of "Okies" and "Arkies" (for those from Oklahoma and Arkansas, respectively).

The Unemployed

In 1929, before the crash of the stock market that marked the beginning of the Great Depression, the unemployment rate in the United States was 3.14 percent. In 1933, in the depths of the Depression, 24.75 percent of the labor force was unemployed. Despite the significant attempts at economic recovery by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal , real change only came with World War II.

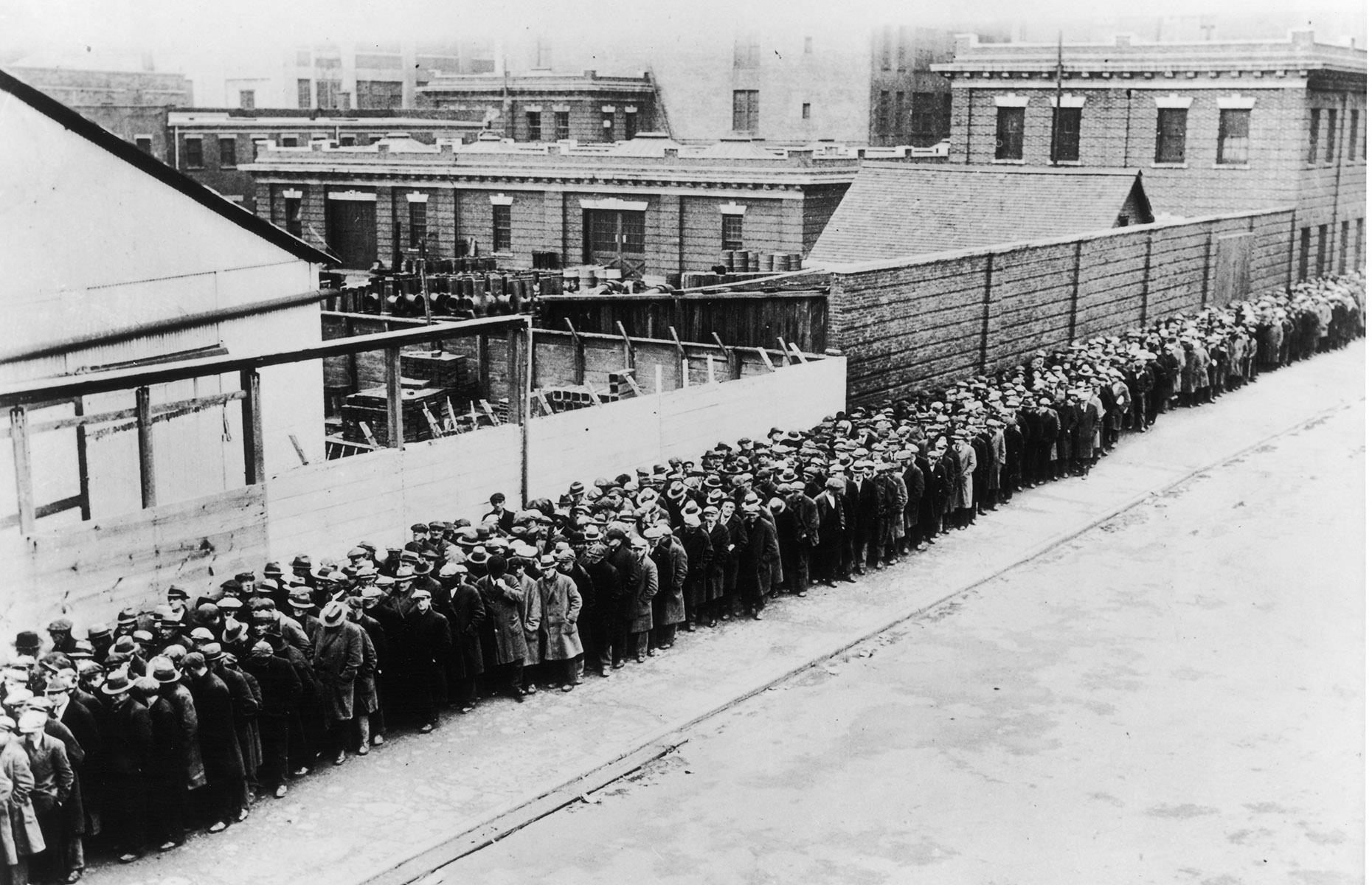

Breadlines and Soup Kitchens

Because so many were unemployed, charitable organizations opened soup kitchens and breadlines to feed the many hungry families brought to their knees by the Great Depression.

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps was part of FDR's New Deal. It was formed in March 1933 and promoted environmental conservation as it gave work and meaning to many who were unemployed. Members of the corps planted trees, dug canals and ditches, built wildlife shelters, restored historic battlefields and stocked lakes and rivers with fish.

Wife and Children of a Sharecropper

Picture from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

At the beginning of the 1930s, many living in the South were tenant farmers, known as sharecroppers. These families lived in very poor conditions, working hard on the land but only receiving a meager share of the farm's profits.

Sharecropping was a vicious cycle that left most families perpetually in debt and thus especially susceptible when the Great Depression struck.

Two Children Sitting on a Porch in Arkansas

Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

Sharecroppers, even before the Great Depression, often found it difficult to earn enough money to feed their children. When the Great Depression hit, this became worse.

This particular touching picture shows two young, barefoot boys whose family has been struggling to feed them. During the Great Depression, many young children got sick or even died from malnutrition.

A One-Room Schoolhouse

Picture from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

In the South, some children of sharecroppers were able to periodically attend school but often had to walk several miles each way to get there.

These schools were small, often only one-room schoolhouses with all levels and ages in one room with a single teacher.

A Young Girl Making Supper

For most sharecropping families, however, education was a luxury. Adults and children alike were needed to make the household function, with children working alongside their parents both inside the house and out in the fields.

This young girl, wearing just a simple shift and no shoes, is making dinner for her family.

Christmas Dinner

For sharecroppers, Christmas did not mean lots of decoration, twinkling lights, large trees, or huge meals.

This family shares a simple meal together, happy to have food. Notice that they don't own enough chairs or a large enough table for them all to sit down together for a meal.

Dust Storm in Oklahoma

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library/National Records and Archives Administration

Life changed drastically for farmers in the South during the Great Depression. A decade of drought and erosion from over-farming led to huge dust storms that ravaged the Great Plains, destroying farms.

A Man Standing in a Dust Storm

The dust storms filled the air, making it hard to breathe, and destroyed what few crops existed. These dust storms turned the area into a " Dust Bowl ."

Migrant Worker Walking Alone on a California Highway

Picture by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

With their farms gone, some men struck out alone in the hopes that they could somehow find somewhere that would offer them a job.

While some traveled the rails, hopping from city to city, others went to California in the hopes that there was some farm work to do.

Taking with them only what they could carry, they tried their best to provide for their family -- often without success.

A Homeless Tenant-Farmer Family Walking Along a Road

While some men went out alone, others traveled with their entire families. With no home and no work, these families packed only what they could carry and hit the road, hoping to find somewhere that could provide them a job and a way for them to stay together.

Packed and Ready for the Long Trip to California

Those fortunate enough to have a car would pack everything they could fit inside and head west, hoping to find a job in the farms of California.

This woman and child sit next to their over-filled car and trailer, packed high with beds, tables, and much more.

Migrants Living Out of Their Car

Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

Having left their dying farms behind, these farmers are now migrants, driving up and down California searching for work. Living out of their car, this family hopes to soon find work that will sustain them.

Temporary Housing for Migrant Workers

Some migrant workers used their cars to expand their temporary shelters during the Great Depression.

Arkansas Squatter Near Bakersfield, California

Photo courtesy the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum

Some migrant workers made more "permanent" housing for themselves out of cardboard, sheet metal, wood scraps, sheets, and any other items they could scavenge.

A Migrant Worker Standing Next to His Lean-to

Picture by Lee Russell, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Temporary housing came in many different forms. This migrant worker has a simple structure, made mostly from sticks, to help protect him from the elements while sleeping.

18-Year-Old Mother From Oklahoma Now a Migrant Worker in California

Life as a migrant worker in California during the Great Depression was hard and rough. Never enough to eat and tough competition for every potential job. Families struggled to feed their children.

A Young Girl Standing Next to an Outdoor Stove

Picture by Lee Russell, courtesy the Library of Congress

Migrant workers lived in their temporary shelters, cooking and washing there as well. This little girl is standing next to an outdoor stove, a pail, and other household supplies.

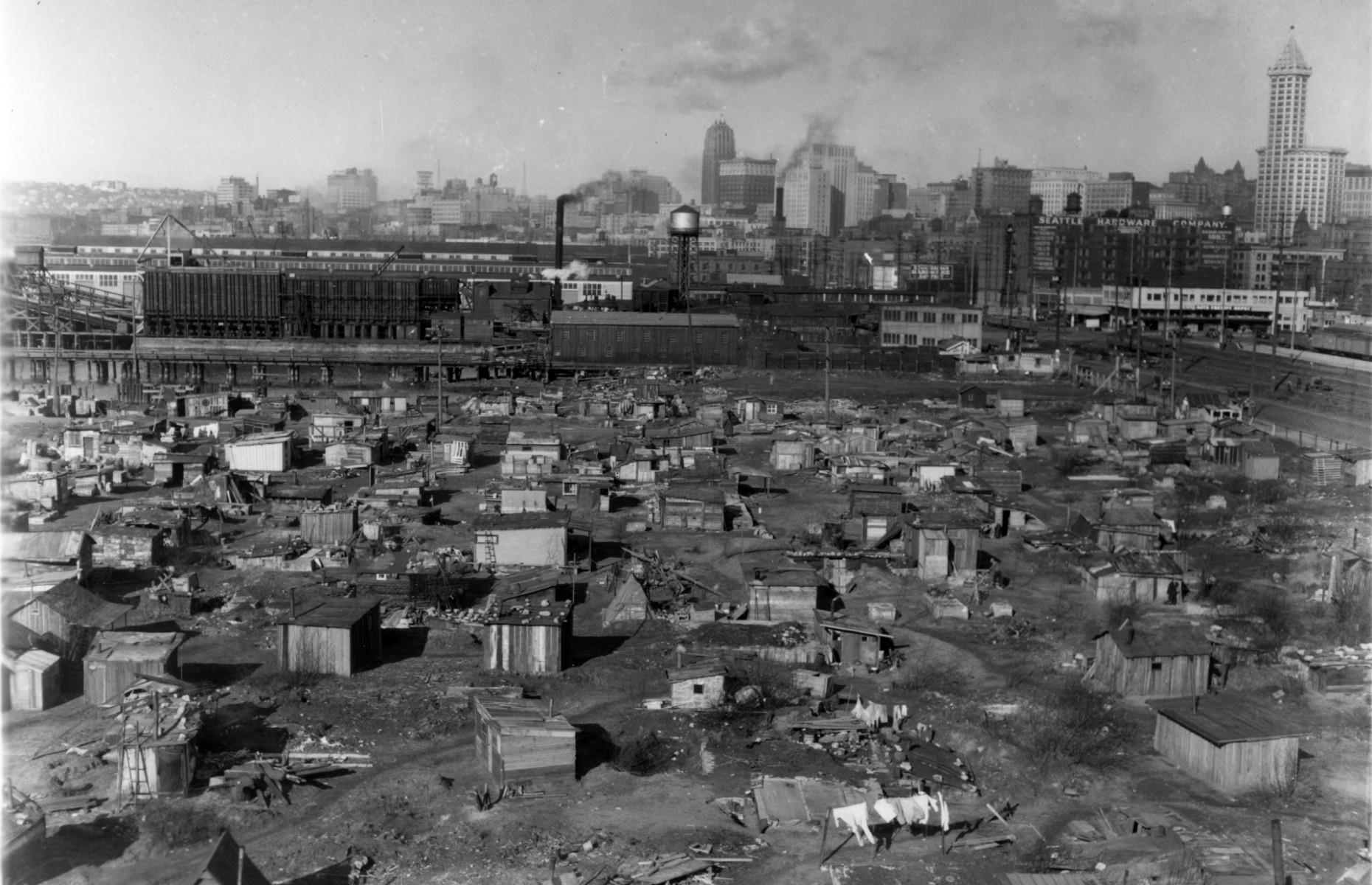

View of a Hooverville

Picture by Dorothea Lange, courtesy the Library of Congress

Collections of temporary housing structures such as these are usually called shantytowns, but during the Great Depression, they were given the nickname "Hoovervilles" after President Herbert Hoover .

Breadlines in New York City

Picture from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Large cities were not immune to the hardships and struggles of the Great Depression. Many people lost their jobs and, unable to feed themselves or their families, stood in long breadlines.

These were the lucky ones, however, for the breadlines (also called soup kitchens) were run by private charities and they did not have enough money or supplies to feed all of the unemployed.

Man Laying Down at the New York Docks

Sometimes, without food, a home, or the prospect of a job, a tired man might just lay down and ponder what lay ahead.

For many, the Great Depression was a decade of extreme hardship, ending only with the war production caused by the start of World War II.

- Complete List of John Steinbeck's Books

- Great Depression Pictures

- A Short History of the Great Depression

- History of the Dust Bowl

- Great Depression in Canada Pictures

- The Dust Bowl: The Worst Environmental Disaster in the United States

- The 1930's Dust Bowl Drought

- Top 5 Causes of the Great Depression

- Hoovervilles: Homeless Camps of the Great Depression

- Dorothea Lange

- Woody Guthrie, Legendary Songwriter and Folk Singer

- The Great Depression, World War II, and the 1930s

- 7 New Deal Programs Still in Effect Today

- Financial Panics of the 19th Century

- 9 Books From the 1930s That Resonate Today

- Biography of Bonnie and Clyde, Notorious Depression-Era Outlaws

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Notes on the Culture

How Dorothea Lange Defined the Role of the Modern Photojournalist

She created one of the most enduring images of the 20th century, but she also created a new model for her discipline.

By Alice Gregory

FOR THE ENTIRE second half of Dorothea Lange ’s life, a quotation from the English philosopher Francis Bacon floated in her peripheral vision: “The contemplation of things as they are, without error or confusion, without substitution or imposture, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention.” She pinned a printout of these words up on her darkroom door in 1933. It remained there until she died, at 70, in 1965 — three months before her first retrospective opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and three decades after she took the most iconic photograph in the medium’s history.

“Migrant Mother,” Lange’s 1936 portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, whose identity wasn’t known for more than 40 years, shows the rag-shrouded torso and shining face of a handsome young woman. She’s seated at a California campsite for migrant workers during the Great Depression, and yet she looks timeless. Her fingers lightly touch the corner of her mouth as she squints into the distance, two of her children hiding from the camera behind her shoulders. Overwhelming hardship but also resilience are evident in both her facial expression and body language. Taken while Lange was working for the federal government’s Resettlement Administration, a New Deal program that aided the high volume of economically displaced, the picture was in MoMA’s inaugural photography exhibition in 1940, alongside works by Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand. Since then, it’s likely been exhibited there more times than any other photograph, and it is on view again at the museum’s second retrospective of Lange , which opened this month. The image, which has appeared on postage stamps, jigsaw puzzles, magazine covers and T-shirts, is familiar even to American schoolchildren. Because it was taken while Lange was a government employee, its rights are in the public domain. It can be — and is — reproduced by anyone, at any time, for any reason.

Unlike a large portion of Lange’s work, the image was never obscure. On the same day that Thompson’s likeness was published in the San Francisco News, it was announced that the federal government was sending 20,000 pounds of food to the California migrant camp where she and her children had been living. “I did not ask her name or her history,” Lange recalled. She learned her age, which was 32, and a few atmospheric details that Thompson would later dispute, but nothing more.

The lack of contextualizing information was atypical for Lange, who believed, uncommonly for a photographer, that “there is no photograph ... that can’t be fortified by words.” If Lange is remembered disproportionately for one photograph out of thousands, she is also remembered disproportionately for pictures in a career that also very much included words. After photographing her subjects, she rushed to take down what they said to use as a caption or a title, and then selected choice quotes, with an ear for the poetry of vernacular language. “ An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion ,” her book on rural poverty from 1939, includes some of the most bracing examples, and even its endpapers are printed with captions like: “Burned out, blowed out, eat out, tractored out,” “We made a dollar working from dawn until you just can’t see,” “I’ve wrote back that we are well and such as that, but I never have wrote that we live in a tent.”

Looking at Lange’s career today, it’s possible to see that her photographic innovations were less visual and technical than they were interpersonal. She spoke while taking people’s pictures. Before asking them any questions at all, she talked about herself. She explained where she was from and her job as she understood it to be; she spoke of her children and of how much she missed them while on assignment. By revealing herself, subjects showed themselves to her in return. More than perhaps any other photographer’s work, Lange’s was less about bearing witness to history than it was about engaging directly with it, of being part of history itself.

Like the new journalists of the 1960s and 1970s, people like Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe , who brought frank personal bias to forms of writing previously heralded as objective, Lange, decades earlier, did something similar in photography. She blurred the line between reportage and fine art and, in so doing, opened the medium for its most celebrated practitioners, the people who would be the inheritors of Lange’s expressiveness and empathy, from Robert Frank to Wolfgang Tillmans . Her contemporary Ansel Adams called her pictures “both records of actuality and exquisitely sensitive emotional documents.” She was an artist under the guise of a journalist and an activist under the guise of a dispassionate civil servant, and it would be impossible to think of any of these roles today without her influence.

LANGE WAS BORN at the very end of the 19th century to educated and prosperous first-generation German-Americans. She read literature, patronized the arts and contracted polio. She retained the limp for the rest of her life. “... [It] formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me,” she said. She grew up in Hoboken, N.J., but attended high school in Manhattan. For fun, she strolled along the Bowery after class — “a lame little girl walking down that street unprotected,” as she once put it. It was then that she first “learned to be unseen.” This combination of looking and disappearing led her to announce, before she ever owned a camera, that she would become a photographer.

After working in New York for several years post high school — and taking a class at Columbia University with the famed art photographer Clarence H. White — she decided to take off on a trip around the world with a friend; a pickpocket curtailed their ambitions and they never made it farther than California. Lange would live there for the next half century. Despite her brief experience with White, she was mostly self-taught, trained in the commercial demands of commissioned portrait photography, whose wealthy subjects sat for her in a rented San Francisco studio. She grew into her aesthetic style and moral motivations, which came to her, together, at once. She was still married to her first husband at the time, an esteemed landscape and mural painter, and her two sons were young. It was 1933, and the Great Depression had reached its lowest point. Lange looked out the window of her studio, where her wealthy and safely ensconced patrons sat, and saw the ravages of joblessness and hunger on the streets below. It was then that she took her first documentary photograph, “ White Angel Breadline ,” which today remains a kind of visual shorthand for food scarcity during the Depression.

This single image — of a group of downtrodden men, all with their backs to the camera except one, whose dirty face is looking hopelessly at the ground — would position Lange alongside Woody Guthrie as a primary witness to America’s decline in the 1930s. With her camera she would capture remarkably intimate images that were universal in their communication of shared suffering: an oddly thin baby nursing at his mother’s breast inside a homemade tent in Blythe, Calif. (“ Drought Refugees From Oklahoma Camping by the Roadside ,” 1936); a man sitting beside an upturned wheelbarrow, his head bowed low in desperation (“ Man Beside Wheelbarrow ,” 1934); two laborers walking down a long and empty dirt road with perhaps all they own in their hands, as they stride past a mocking billboard advertisement for the Southern Pacific railway that reads “Next Time Try the Train, Relax” (“ Toward Los Angeles, California ,” 1937).

Not long after abandoning society pictures, Lange was separated from her husband and working alongside Paul Taylor, a Berkeley agricultural economist whom she would soon marry. The California State Emergency Relief Administration hired Taylor in 1934 to study migrant workers, and he convinced them to hire Lange in 1935, sneaking her onto his research trips as a typist, knowing very well that she would, in fact, be photographing everything. They traversed the state and together devised a new kind of multimedia sociology, one that was part oral history and part visual documentation. Sometimes their tactics were wily. In Arizona, Taylor got a running count of migrants by hiring a gas-station attendant to clock them. His figures, alongside Lange’s photographs of extreme destitution and hopelessness, were the first records of what would become known as the Dust Bowl, the name given to the drought-choked Southern Plains. The physical image we retain of this era was almost single-handedly shaped by Lange. Her initial joint report with Taylor was spiral-bound and included over 50 of Lange’s photographs. These were bureaucratic reports conceived like novels, with Lange capturing the sort of detail no pie chart could render — the decaying roll of linoleum, for instance, that a homeless family had been carting around for three years in hopes of once again having a kitchen floor.

For the next four years, Lange was employed by the federal government’s Resettlement Administration, renamed the Farm Security Administration in 1937, and developed a compassionate but matter-of-fact style that focused merely on the subjects of the day, ones that have once again become familiar: environmental degradation, rural poverty, mass migration. Her depictions of these topics would define the rest of her career and help create a topical lexicon of American concerns, and her mythic compositions made from ordinary lives appear neither intentionally newsworthy nor artificially arranged. Lange’s attention to texture and detail make individual human subjects look like evidence of a national crime. Indeed, her 1942 photographs of Manzanar, the concentration camp in eastern California where Japanese-Americans were held during World War II, were impounded and then censored by the military. Among the ones found most dangerous to the national image showed workers picking crops in a greenhouse, whose intricate frame cast striped shadows that resembled prison bars. In their depictions of inhospitably barren landscapes, institutional living facilities and tiny children with numbered tags hung around their necks, they look eerily similar to photographs being taken today at the Mexican border. These images, alongside her portraits of the Dust Bowl, did nothing less than heighten the stakes of what we expect from a photograph, expectations that persist: These days, the camera, whether a Leica or an iPhone, is not so much a documentary tool as a politicking one — an incitement to outrage, a method through which to seek dramatic transformations of the status quo.

IT WASN’T UNTIL a 1963 trip around the world with Taylor, Lange said, that she truly considered herself to be an artist. For a few years before the journey, she had been a freelance photographer at Life magazine and thought of her work as something closer to straightforward journalism. But it was in places where she knew no one, didn’t speak the language and traveled by rickshaw and motorbike that the sensitivity of her own vision became clear even to herself. By this time, she was suffering from esophageal cancer and so thin that her clothes had to be held up with safety pins. When she returned, she began assembling decades’ worth of work for her MoMA retrospective — she thought of it as making sentences out of pictures, paragraphs if she was lucky. Lange was only eating soft foods by this point and rarely ventured outside. She kept a camera around her neck, though, “for health,” and continued to take photographs — of her house, of her family. Her son wrote to the curator saying that he thought she was staying alive almost entirely for his visits. He estimated her chances of living to see the show open as 50-50.

MoMA, which hadn’t devoted a major show to Lange since, reopened last fall after months of renovation with a fortified list of existential priorities, one of which is to approach its permanent collection with the enthusiasm and scholarship that in the past was typically spent on loaned works. It’s in this spirit that the curator Sarah Meister organized “Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures.” The exhibition spans approximately a hundred photographs. It unfolds more or less chronologically, but in keeping with Lange’s belief that a photograph’s effect can be fortified with text, the gallery layout includes reading areas so visitors can experience the text as they would in a book, instead of uncomfortably on the wall.

What does Lange’s career look like in 2020? It’s clear she was an anomaly from the start, an evident female star in a field dominated by men, a photographer whose work was both funded by the federal government and embraced by the contemporary art world of her day. She produced evidence of the worst moments in this country’s history: the migration of the sick and starved across the country during the Depression, the cruel folly of Japanese internment and the moral disaster of segregation. (In 1941, her photographs of black farmers in the South would accompany Richard Wright ’s prose in the book “12 Million Black Voices.”) But it was in looking at these grim, often ignored corners of life that Lange found figures of resilience, dignity and unlikely survival. Her legacy combines two fields — art and journalism — whose entirely separate constraints and ethics can still, at their best, change the world.

For a woman whose images seemed to reveal so much about others, there is only a small amount of material that reveals Lange herself, just a handful of blurry images from her travels through the ruins of the American West during the Depression, her small frame almost eclipsed by her hulking camera. Perhaps the greatest portrait that exists of her is an excerpt from crackly, black-and-white film footage from 1964, where she’s seen discussing the negative of a picture she shot of some elegantly proportioned pueblo steps in New Mexico, beside which lies a bit of rubbish. “The man with a certain kind of training will never remove those two cans and the other man must,” she says. She pauses, mutters the words “these wretched little cans down here,” and then she sighs. “Well,” she concludes, “you accept it.” Lange didn’t necessarily accept the flaws in the world around her, but she didn’t look away, either.

Alice Gregory is a contributing editor at T, where she covers art, culture, and travel. She also writes for the Book Review. More about Alice Gregory

Art and Museums in New York City

A guide to the shows, exhibitions and artists shaping the city’s cultural landscape..

At the Museum of Modern Art, the documentary photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier honors those who turn their energies to a social good .

Jenny Holzer signboards predated by a decade the news “crawl.” At the Guggenheim she is still bending the curve: Just read the art, is the message .

The artist-turned-film director Steve McQueen finds new depths in “Bass,” an immersive environment of light and sound in Dia Beacon keyed to Black history and “where we can go from here.”

A powerful and overdue exhibition at El Museo del Barrio links Amalia Mesa-Bains’s genre-defying installations for the first time.

Looking for more art in the city? Here are the gallery shows not to miss in June .

21 April 2024

The depression era photography of dorothea lange.

Give a Gift

If you enjoyed this article, please consider making a gift to help Kuriositas to continue to bring you fascinating features, photographs and videos.

Follow Kuriositas on the socials

More articles from kuriositas.

Allow the use of cookies in this browser?

National Trust for Historic Preservation: Return to home page

Site navigation, america's 11 most endangered historic places.

This annual list raises awareness about the threats facing some of the nation's greatest treasures.

Join The National Trust

Your support is critical to ensuring our success in protecting America's places that matter for future generations.

Take Action Today

Tell lawmakers and decision makers that our nation's historic places matter.

Save Places

- PastForward National Preservation Conference

- Preservation Leadership Forum

- Grant Programs

- National Preservation Awards

- National Trust Historic Sites

Explore this remarkable collection of historic sites online.

Places Near You

Discover historic places across the nation and close to home.

Preservation Magazine & More

Read stories of people saving places, as featured in our award-winning magazine and on our website.

Explore Places

- Distinctive Destinations

- Historic Hotels of America

- National Trust Tours

- Preservation Magazine

Saving America’s Historic Sites

Discover how these unique places connect Americans to their past—and to each other.

Telling the Full American Story

Explore the diverse pasts that weave our multicultural nation together.

Building Stronger Communities

Learn how historic preservation can unlock your community's potential.

Investing in Preservation’s Future

Take a look at all the ways we're growing the field to save places.

About Saving Places

- About the National Trust

- African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund

- Where Women Made History

- National Fund for Sacred Places

- Main Street America

- Historic Tax Credits

Support the National Trust Today

Make a vibrant future possible for our nation's most important places.

Leave A Legacy

Protect the past by remembering the National Trust in your will or estate plan.

Support Preservation As You Shop, Travel, and Play

Discover the easy ways you can incorporate preservation into your everyday life—and support a terrific cause as you go.

Support Us Today

- Gift Memberships

- Planned Giving

- Leadership Giving

- Monthly Giving

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538187

Photo Essay: Manzanar Relocation Center through Dorothea Lange's Lens

- By: Katharine Keane

- Photography: Dorothea Lange

Best known for her iconic Depression-era image Migrant Mother , photographer Dorothea Lange—on assignment for the War Relocation Authority (WRA)—spent months chronicling the forced removal and internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

The majority of Lange’s photos did not conform to the WRA’s aim of showing a positive side of the incarceration, and for this reason many of her hundreds of images were impounded. Unfortunately, the WRA retained the right to caption images submitted by their photographers, often altering the truth—a manipulation that affected Lange after she completed her assignment.

photo by: LC-USF34-002392-E

Dorothea Lange with her camera.

In a letter to her friend and colleague Ansel Adams (who also photographed life at Manzanar ), Lange wrote, “I fear the intolerance and prejudice is constantly growing. We have a disease. It’s Jap-baiting and hatred. You have a job on your hands to do to make a dent in it—but I don’t know a more challenging nor more important one. I went through an experience I’ll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot, even if I accomplished nothing.”

Scroll down for a glimpse of what Lange saw during her time at Manzanar Relocation Center.

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538123

Manzanar housed over 110,000 incarcerated Japanese-Americans from 1942-1945.

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538087

The WRA captioned this image: "Evacuees enjoying the creek which flows along the outer border of this War Relocation Authority center."

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 537992

Grandfather and grandson at Manzanar.

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 537955

Young students returning to their barracks from classes.

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538076

A young boy reads the funnies.

“I went through an experience I’ll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot, even if I accomplished nothing.” Dorothea Lange

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538012

The WRA caption: "Little evacuee of Japanese ancestry in a happy mood at this War Relocation Authority center."

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538184

The first grave at Manzanar Relocation Center.

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 537969

Two girls wait outside the mess hall for lunch.

photo by: Dorothea Lange/WRA/National Archives 538011

Around two-thirds of all Japanese-Americans at Manzanar were Americans by birth.

Japanese-American History : Photo Essay: The Manzanar War Relocation Center

In 1943, at the invitation of his friend, camp director Ralph Merritt, Ansel Adams came to Manzanar War Relocation Center to document the camp and the people interned there.

Katharine Keane is a former editorial assistant at Preservation Magazine. She enjoys getting lost in new cities, reading the plaques at museums, and discovering the next great restaurant.

Like this story? Then you’ll love our emails. Sign up today.

Sign up for email updates, sign up for email updates email address.

Related Stories

Announcing the 2024 list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places.

Love Exploring

America's Great Depression Brought To Life In Heartbreaking Photos

Posted: June 1, 2024 | Last updated: June 1, 2024

Snapshots of suffering

At the beginning of the 1930s, the US was cast into the Great Depression. Over the next decade millions of Americans were plunged into poverty, and thanks to increasingly cheap and accessible cameras this horrendous socio-economic downturn was photographed for posterity. These pictures now provide snapshots of the lives of ordinary Americans during the unprecedented crisis, from the chaos of the Wall Street Crash to the escapism of The Wizard of Oz .

Click through our gallery to see the most amazing and somber images from the Great Depression...

1929: Disaster on Wall Street

There were few signs of impending economic disaster during the 1920s, a decade so prosperous that Americans called it the Roaring Twenties. Easy credit meant that it wasn’t just traders who could make a quick buck on the Wall Street Stock Exchange trading floor, pictured here.

Ordinary Americans with little understanding of the financial markets were caught up in the speculation, and the boom years came to an abrupt end in 1929 when rumors of an impending recession caused investors to begin selling their stocks.

1929: Black Thursday

The stock market crash began on Thursday October 24 1929, now known as Black Thursday. Stock prices plunged as panicking traders tried to sell off their stocks before they dropped further, which only pushed the going rate even lower.

The vicious cycle saw the market drop 13% on the following Monday ('Black Monday'), and another 12% on the Tuesday ('Black Tuesday'). Traders who previously made gigantic sums suddenly found themselves losing everything, like poor Walter Thornton pictured here.

1930: Minigolf takes off

Away from Wall Street, the effects of the crash took time to materialize, and life initially continued as normal. For many American families, that involved a weekend round of minigolf.

More than 30,000 minigolf courses were built during the 1930s, with prices ranging from 25 to 50 cents per round – a reasonable price, even when belt straps had to be tightened. The best players were invited to play at minigolf tournaments in stadiums like this one in Chicago.

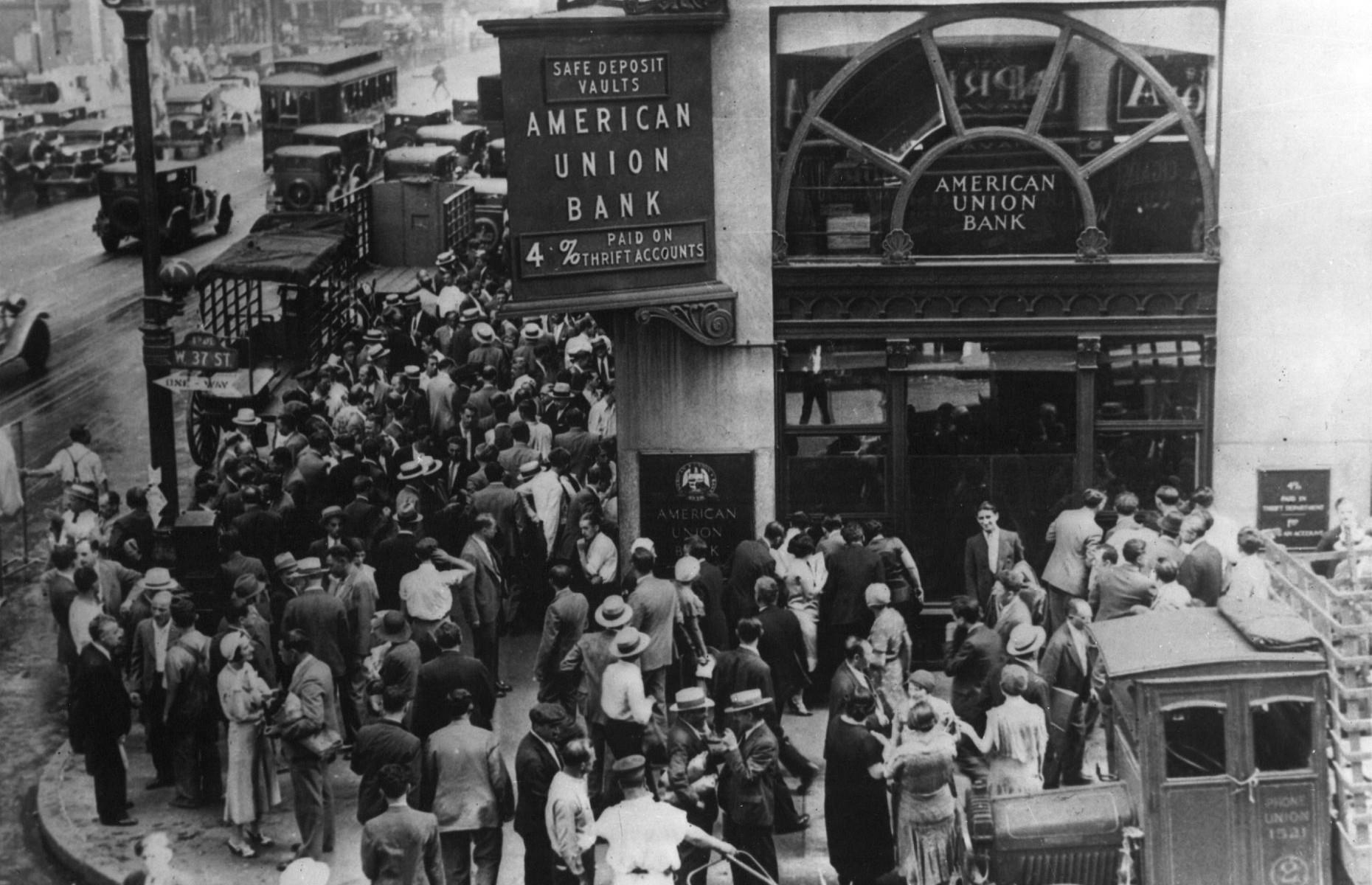

1930: The banking crisis deepens

Squeezed by the loss of business after the Wall Street Crash, several high-profile banks were in trouble by the end of 1930 and worried customers flocked to withdraw their savings while they still could. These bank runs made the situation worse, and hundreds of banks closed their doors for good, including the American Union Bank in New York (pictured).

Little help was on hand for the unlucky Americans who couldn't get their money back and many lost their entire life savings.

c. 1930: Queuing for aid

As workers tumbled into poverty thanks to rapidly rising unemployment and, in some cases, the total loss of their savings, they were forced to rely on the state for help. Local government initiatives to feed and shelter those in need were overwhelmed by crowds of people, like this long queue of men patiently waiting for a free dinner at a municipal boarding house in New York.

1931: Soup kitchens provide a lifeline

As the government became overwhelmed with requests for aid, voluntary organizations did their best to step into the breach. Local benefactors across the country set up facilities to provide simple but nutritious fare.

This soup kitchen served an average of 2,200 hungry Chicagoans every day – and the man who funded it was notorious gangster Al Capone, who fed the people of his city to improve his public image.

1931: The first hunger march

The occasional free meal wasn’t enough for most unemployed workers, who wanted the government to provide more support. In December 1931, 1,670 hunger marchers converged on Washington DC, having set out in four columns from Boston, Buffalo, Chicago, and St Louis.

They insisted that the government provide financial relief and insurance, but political leaders in Congress refused to meet with them and the marchers returned home no better off than when they left.

1932: The rise of the radio

During the 1930s, the proportion of American households with radios grew from roughly 40% to 83%. Families like this one temporarily left their cares behind by tuning into the latest exploits of the Lone Ranger and the Green Hornet.

Kids enjoyed Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie, while sports fans listened to broadcasts of baseball and boxing, and politicians made use of the new medium to speak directly to voters.

1932: President Herbert Hoover

President Herbert Hoover failed to recognize the severity of the Depression when it first struck and he tried to keep the federal government out of direct relief efforts.

In May 1932, President Hoover finally got to his feet and promised greater state aid for poverty-stricken Americans in a news conference at the White House. It was too little, too late. Most voters had already made their minds up that Hoover was to blame for the dire state of the country.

Liking this? Click on the Follow button above for more great stories from loveEXPLORING

1932: The Bonus Army marches on Washington

In the summer of 1932, between 10,000 and 25,000 First World War veterans (estimates vary) and their families marched on Washington DC and set up camp in the capital. The demonstrators demanded the immediate pay-out of insurance bonuses earned during the war to alleviate the effects of the Depression.

These bonuses had been approved by Congress but were not yet due in full, and the Senate rejected a bill that authorized the payment. However, President Hoover couldn’t ignore the starving former servicemen right outside his gates.

1932: The Bonus Army is evicted

Embarrassed by the presence of so many campaigners and disquieted by the unrest, the government authorized the army and police to evict the demonstrators by force. General Douglas MacArthur used tanks and tear gas to remove the veterans, who did not go quietly, and at least one former soldier was killed by gunfire.

Though the demonstrators were moved on and their camp burned, the sight of former servicemen being attacked by the country they served was a political blow for Hoover.

c.1932: Hoovervilles spring up across the country

The Bonus Army camp wasn’t the only temporary settlement that arose during the Depression. Hundreds of shantytowns cropped up on the outskirts of cities as unemployed workers were evicted from their homes and built shelters out of whatever they could lay their hands on.

Named Hoovervilles after the increasingly unpopular President Hoover, the shantytowns in St Louis and Seattle (pictured here) were particularly large, with thousands of inhabitants.

1933: President Roosevelt’s inauguration

Few were surprised when Americans voted for new leadership in the 1932 Presidential Election. Herbert Hoover had presided over the biggest economic crisis in the country’s history, while his opponent, Franklin D Roosevelt, promised to tackle the Depression by increasing state aid for the poor and taking a more active role in the economy. Roosevelt’s campaign ended in a landslide win: he carried 42 of the 48 states and, as shown here, took the oath of office in March 1933.

c. 1933: The New Deal

Among President Roosevelt’s campaign promises in the 1932 election was a "new deal for the American people." During a busy first hundred days in power, Roosevelt created several new federal agencies in the hope of kickstarting the economy.

These workers for the new Civilian Conservation Corps were paid to build a road – one of a wide range of new state-run projects that also included building irrigation canals, planting trees, and constructing infrastructure in federal and state parks.

1933: Sharecropper strikes hinder production

Not every worker lost their job during the Depression, but those who remained employed were often still impacted by the crash, and some agitated for change to help them cope. Spurred on by the New Deal, employees banded together to argue for better conditions.

The Sharecroppers' Union was founded in Alabama in 1931, and in 1933 California's sharecroppers went on strike, refusing to harvest the year's valuable cotton crop. Here, picketers near Tulare watch for workers crossing the line and breaking the strike.

1934: Building California's roads

As the Depression continued, President Roosevelt pushed for more money to be spent on job creation projects, but his critics complained that the money was being wasted. These workers from the Civil Works Administration are building the Lake Merced Parkway Boulevard in San Francisco, but an inflated workforce made the road-building process inefficient and expensive.

Site managers struggled to find enough meaningful jobs and some laborers were set useless tasks like digging and refilling ditches and breaking rocks with sledgehammers.

c. 1935: Board games become big business

Board games like Scrabble and checkers (pictured) were a popular and cheap form of recreation, and they were joined in 1935 by a new smash hit: Monopoly. The irony of a game that celebrated the rich getting richer while the poor went bankrupt wasn’t lost on most players – indeed, it was originally devised as a warning about the evils of capitalism – but they enjoyed the escapism and value for money of a game that families could play over and over.

c. 1935: Soapbox racing takes off

A way for energetic kids to have fun without spending money, soapbox derbies – racing homemade karts down hills – spent the early 1930s evolving into an all-American championship sponsored by Chevrolet. Boys (girls couldn’t compete until 1971) raced in regional qualifiers like this one in Los Angeles, hoping to win a spot in the national Soap Box Derby in Akron in Ohio, first held there in 1935.

1935: Homelessness is widespread

As the Depression continued to bite, unemployed workers who were unable to pay rent found themselves cast onto the streets. Many made their way to large cities like New York (pictured) and San Francisco in search of work.

Unable to pay for even the simplest hostels, they roamed the streets and found shelter under bridges, in culverts, or camped in alleys and doorways. Some cities turned a blind eye to the homeless; others turfed them out and hoped they’d move on.

1935: Volunteers serve Thanksgiving dinner

The Volunteers of America was an organization formed to combat poverty in the 1890s, but during the Depression it was nigh impossible to cater to everybody in need. The volunteers advertised job opportunities in employment bureaus, staffed penny pantries where every item cost one cent, and ran soup kitchens to feed those who couldn’t even afford that.

The 1935 Thanksgiving dinner served to more than 3,000 homeless New Yorkers (pictured here) included 1,500 lbs of turkey and 400 pies.

1936: The Dust Bowl spells disaster for farmers

Mass westward migration over the previous century had turned millions of acres of formerly uncultivated land into vast fields of wheat and corn, but the beginning of the Depression coincided with a terrible drought, and the bare fields lacked the deep-rooted grasses that could have held the soil in place. When the winds picked up, the soil simply blew away, putting more than 35 million acres of farmland out of commission and bringing into being the so-called 'Dust Bowl.'

1936: Dust storms engulf the plains

The dust storms, nicknamed 'black blizzards' blew across the country in vast clouds, as shown here in Texas. The grubby air covered windows in New York and coated the decks of ships on the Atlantic.

President Roosevelt extended his New Deal to include tree planting and reforestation of farmland, but the Dust Bowl only began to ease when regular rainfall patterns resumed in 1939.

1936: Migrant Mother makes history

Two and a half million people were forced away from the Dust Bowl states – among them a woman called Florence Thompson who spent time at a migrant camp in Nipomo, California. It was there that famous documentary photographer Dorothea Lange spotted her huddled in a tent with her children and her anxious expression came to epitomize the Depression era.

Thompson had already left the camp by the time she became famous and was only identified in 1978 – until then, she was simply known as Migrant Mother.

1936: The rise and fall of Charles Coughlin

Franklin D Roosevelt won four consecutive presidential elections by huge margins, but the United States wasn’t totally devoid of political debate. One of his loudest critics was Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest who split from the Democrats in 1934 and set up the National Union for Social Justice to challenge Roosevelt’s New Deal.

His words clearly had an audience – in this image, 26,000 people attend one of his speeches in Cleveland, Ohio. Coughlin moved steadily to the right and eventually became a mouthpiece for Nazi propaganda in America.

1936: Difficult Christmases

Belts were fastened so tight that many families didn’t have cash to spare for Christmas in the 1930s, and the festive fare at this Christmas dinner in Iowa was potatoes, cabbage, and pie.