This website uses cookies to ensure the best user experience. Privacy & Cookies Notice Accept Cookies

Manage My Cookies

Manage Cookie Preferences

Confirm My Selections

- Events and Workshops

- Research Labs

- PhD Program

- Resources for MBA Students

- Publications

- Our History

- Virtual Lab

- Pop Up Labs

Virtual Lab Online Research Studies

The pimco decision research virtual lab at the roman family center for decision research allows people from around the world to take paid research studies online using surveys, zoom video calls, and other remote tools..

Video Transcript

Transcript coming soon.

By participating in online behavioral science studies, you play a vital role in helping Chicago Booth researchers better understand judgment and decision-making.

Note: the Virtual Lab will be closed June 3-7.

Here's how you can take paid surveys and interactive studies from the comfort of home. Sign Up (New Participants) Log In (Existing Participants)

Take Studies in the Virtual Lab

You'll need:.

- A computer, smartphone, or tablet

- Internet connection

How to Get Started

- Sign up for an account. Within 1 business day, you'll receive an email with your login info and other important information.

- Tell us about yourself. The first time you log into your account, you'll be prompted to take a short prescreen survey about you and your background. Watch a video tutorial.

- Sign up for paid surveys: When you log in, you'll see the studies you are eligible to take. By default, participants are eligible for surveys, one of our two types of studies.

- Optional: Take the Zoom Prerequisite Study Pays $3 / 10-15 min. / Appointments Tu-Fri, 11am-4pm CT Many of our highest-paying studies are conducted via Zoom, a video chat platform. To become eligible for these more advanced studies, you must pass the Zoom Prerequisite Study. You'll need a computer with a working microphone, webcam, and audio. Video tutorial .

After completing these introductory tasks, you'll be able to sign up for behavioral science studies on our online research platform, Sona . Sign Up to Participate

Compensation

Participants are paid at a rate of $12 per hour ($1 for every 5 minutes). After completing a study, you'll be emailed an Amazon digital gift card as payment , typically within two business days.

Please note that if you are located outside of the United States, you will only be able to redeem Amazon electronic gift cards via the USA-based amazon.com site, and not on Amazon sites based in other countries.

What to Expect

Behavioral science combines psychology, economics, and other fields to better understand human decision-making.The Virtual Lab's online research studies involve simple, everyday tasks like filling out surveys, providing your opinions, or chatting with a study partner.

Interactive studies are conducted using Zoom, a video chat platform. These tend to be our highest paying studies and require appointments scheduled Tuesday-Friday. Before taking Zoom studies, you must first complete the Zoom Prerequisite Study. Tips for using Zoom .

We pride ourselves on creating an inclusive and safe environment for all participants and researchers, so please review the Virtual Lab code of conduct before participating.

Questions? Email us at [email protected] .

Current Participants

Log into your account to see the paid research studies you are currently eligible to complete. Don't see any studies? Check back soon! New studies & time slots are posted each weeknight by 8pm.

Surveys are available on-demand 24/7 and can be completed any time before the study's deadline.

Zoom studies are conducted Tuesday-Friday 11am-4 pm CT (UTC -5).

For Researchers

If you are a researcher interested in conducting online studies in the Virtual Lab, please visit the Researcher Portal (requires CNET ID) or contact the Virtual Lab to discuss your options. The labs team can help with IRB approval, study design, data analysis, and more.

Follow the Roman Family Center for Decision Research

DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY

- Participate in Research Studies

Paid Research Opportunities

The following studies are recruiting participants and pay for your time. Read the descriptions and requirements. If you are interested, email the researcher asking to participate. Information on some studies is also posted on bulletin boards in Swift Hall.

Daily Experiences Across Relationships (DEAR) Study

Northwestern’s Relationships and Motivation Lab and University of Chicago’s CEDAR Lab are conducting a 6-month study about people’s life experiences and romantic relationships. This study consists of all online surveys that can be done from home. It involves a quick introductory zoom session with a member of our research team, an hour-long initial survey, 2 weeks of short 5-minute surveys, and three 25-minute follow-up surveys that come 2, 4, and 6 months later. You and your partner can earn up to $120 each for participating ($240 per couple).

You may be eligible if you:

- Have been in a relationship for at least 6-months

- Both of you are at least 25 years old, current US residents, and fluent English-speakers

- Have regular internet access

- Have a romantic partner who is willing to participate

Please contact Erin at [email protected] for more information!

Principle investigator: Eli Finkel

Study Title: Daily Experiences Across Relationships Study

IRB #: STU00219294-MOD0001

Cognitive Architecture of Bilingual Language Processing

The Bilingualism and Psycholinguistics Research Group at Northwestern University is looking for Korean-English bilinguals for an EEG study on language and cognition. We are interested in how languages are represented in the mind. Electroencephalography (EEG) is a safe and non-invasive neuroimaging technique. We are recording the neural activity at the surface of the scalp as it naturally occurs in the brain. The testing session takes approximately 3 hours to complete. For your time and effort, you will be compensated $15 per hour.

You may be eligible to participate if:

-You are proficient in Korean and English.

-You are between the ages of 18 and 35.

-You are right-handed.

-You have normal or corrected-to-normal vision (glasses, contacts).

-You have no history of neurologic, cognitive, or psychiatric disorders.

The study takes place at Northwestern’s Evanston campus at 2240 Campus Drive (Frances Searle Building) in room 3-367. Appointments will be scheduled at a time that is most convenient for you.

If you are interested, please email Ashley Chung-Fat-Yim at [email protected] or give us a call at 847-467-2709.

Principal Investigator: Dr. Viorica Marian

Study Title: Cognitive Architecture of Bilingual Language Processing

IRB #: STU00023477

Can over-the-counter hearing aids help with hearing loss?

The Hearing Aid Laboratory at Northwestern University is looking for participants for a research study about how over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids impact how we listen and communicate with others. We are looking for adults with known or suspected mild-to-moderate hearing loss to bring a communication partner with them (i.e., spouse, friend, neighbor, adult child, etc.) to have a conversation together while wearing OTC hearing aids.

What to expect:

- The study involves a total of 2 visits to our lab.

- The first visit involves tests of memory, hearing, and communication with a partner for one visit to our lab, lasting approximately 2 hours. We will provide you with a free comprehensive hearing test, and you will be fit with OTC hearing aids during your visit to the lab.

- The second visit involves a test of speech in background noise while wearing OTC hearing aids.

You may be eligible to participate if:

• You have diagnosed or suspected mild to moderate hearing loss in both ears

• You are 18 years or older

• You are able to bring someone with you to your first visit

• You have normal or corrected-to-normal vision (glasses, contacts)

• No history of neurologic, cognitive, or psychiatric disorders

The person you bring to the study with you is eligible if:

• They have no hearing loss, OR wear hearing aids consistently if they have hearing loss

• Are at least 18 years of age

• English is their primary language

• Normal or corrected-to-normal vision (glasses, contacts)

The study takes place in either Northwestern’s main campus at 2240 Campus Drive in Evanston, or at our downtown location at 710 N Lake Shore Drive in Chicago. Visits will be scheduled at the located that is most convenient for you.

If you are interested, please email us at [email protected] or give us a call at 847-467-0897.

You can also fill out an initial interest form by clicking here.

Principal Investigator: Dr. Pamela Souza

Study Title: Investigation of direct-to-consumer hearing aids on conversation efficiency and listening effort

IRB #: STU00217791

Visual Adaptation, Selective Attention, and Shape Coding: An Integrative Investigation of Visual Attention; Understanding the Mechanisms that Control the Dynamics of Perceptual Switches

The laboratories of Dr. Satoru Suzuki and Dr. Marcia Grabowecky are currently seeking healthy adults to participate in research on perception. Studies take place on the Northwestern University Evanston campus. Participants are compensated $15/hour for volunteering. Note: no transportation or parking costs will be covered.

If you are interested in participating, please contact our laboratory by telephone (847) 467-6539, or email for more information: [email protected]

Once you contact the laboratory, you will be informed of studies in progress and their specific requirements (for example, handedness, age range, gender) and procedures. Typically, studies involve responding to images or sounds presented by a computer and last from 1-2 hours. Some studies also require responding to personality or mood questionnaires, or having physiological responses recorded (for example, brain waves or eye movements). The details of the particular study will be provided when you contact the laboratory. If you are interested in volunteering and you qualify to participate in any ongoing studies, an appointment will be scheduled.

Principal Investigators: Dr. Satoru Suzuki and Dr. Marcia Grabowecky

Study Title: Visual Adaptation, Selective Attention, and Shape Coding: An Integrative Investigation of Visual Attention; Understanding the Mechanisms that Control the Dynamics of Perceptual Switches

IRB #: CR1_STU00013229

Psychosis Risk Outcomes Network Study

We are seeking young people who are concerned about recent changes in mood, thinking or behavior. This research project aims to increase understanding of mental health concerns in young people and how to prevent the development of a more serious mental illness such as psychosis.

You may be eligible for the study if you meet any of the following criteria:

- Ages 12 - 30

- Noticing a recent change in thinking, behavior, or experiences, such as:

- Confusion about what is real or imaginary

- Feeling not in control of your own thoughts of ideas

- Feeling suspicious or paranoid

- Having experiences that may not be real, such as hearing sounds or seeing things that may not be there

- Having trouble communicating clearly

The study would entail visits over a 2-year period, and you would be paid $30 per hour for your participation. Eligible participants will be asked to come in for various assessments including:

- clinical interviews

- biological assessments (MRI & EEG brain scans; blood and saliva testing)

- cognitive testing

If you are interested, please email us at [email protected] or fill out this online eligibility survey , and a member of our team will get back to you shortly.

Principal investigator: Dr. Vijay Mittal Study Title: ProNET IRB #: STU00215145

Good at sleeping?

The Cognitive Neuroscience Lab in the Department of Psychology at Northwestern is recruiting volunteers to participate in sleep research ( STU00034353 )

Compensation is provided for studies ($12.50/hr)

You can participate in Chicago or at our sleep lab on the Evanston campus.

To sign up and learn more about the The Paller Lab, visit: www.northwestern.edu/people/kap/apply

Principal Investigator: Dr. Ken Paller

Study Title: Strategically strengthening declarative memories during sleep: Learning, Creative Problem-Solving, REM Sleep, and Dreaming

IRB# STU00034353-MOD0044

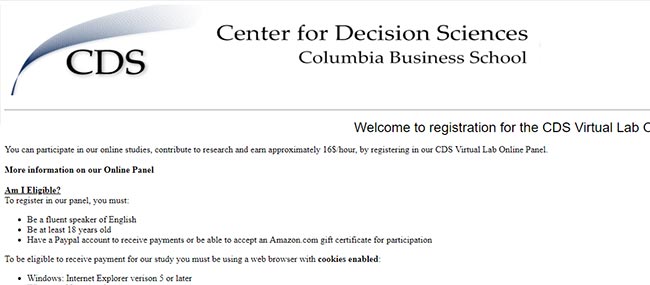

- Be a fluent speaker of English

- Be at least 18 years old

- Have a Paypal account to receive payments or be able to accept an Amazon.com gift certificate for participation

To be eligible to receive payment for our study you must be using a web browser with cookies enabled :

- Windows: Internet Explorer verison 5 or later

- Windows: Netscape 6 or later

- Mac: Safari

- Any: Firefox

If this sounds like you, please complete the following page. If you qualify, we will contact you by email in advance of the experiment.

Will I get paid?

You will not receive payment for filling out the form to register for our Online Panel. However, you will be paid for completing our online studies you will be invited to. Payments are mainly handled by PayPal ( www.paypal.com/ ) a free service. Therefore, make sure that the email you sign up with is the same email address associated with your Paypal account . This way your earnings can be directly deposited in your account. Alternatively, in many of our studies, you can choose to receive payment in the form of an Amazon.com gift certificate. If you do not wish to be paid via Paypal or with an Amazon.com gift certificate, please do not participate in this research. Payment is approximately $16 per hour , however this varies depending on the length of the study. You may also earn bonus payments, which depend on the study as well.

How is data I provide stored?

Information about you will be kept in strict confidentiality and stored on a remote server hosted by Amazon Web Services (AWS). Your information will not be shared with anyone outside the Center for Decision Sciences and you will not be contacted except as it concerns the Center for Decision Sciences Virtual Lab. Your personal information will be kept indefinitely until request for deletion and will under no circumstances be given out to third parties. You may choose to remove yourself from our online participant panel at any time without penalty by emailing [email protected] with the email address associated with your account. Likewise, the Center for Decision Sciences reserves the right to remove participants from our panel at any time. Please note that removal from the online panel itself doesn’t guarantee removal from past studies in which you have already participated. If removal occurs, periodic emails will be sent to ask if you prefer to have your information completely deleted from our system.

What do I consent to?

By registering in the CDS Virtual Lab Online Panel, you consent to receive email invitations from the Center for Decision Sciences to participate in online surveys for which you may qualify. Except as it concerns online studies, you will not be contacted. Your participation in online studies is entirely voluntary. You may choose to participate in certain surveys and decline to participate in others. However, you will not be able to participate in our web-based online studies if you do not join the online panel.

What research studies am I going to participate in?

For more information on the Center for Decision Sciences and our research projects please visit our homepage . If you have any questions or concerns, please contact us at [email protected] .

If at any time you have questions or concerns about your rights or welfare as a research subject, contact the Columbia University Morningside Institutional Review Board (IRB) by email at [email protected] , or by phone at 212-851-7040.

What are the research purpose, risks, and benefits?

The purpose of the CDS Virtual Lab Online Panel is to create a mailing list of participants (also called panelists) that r eceive invitations to participate in paid online surveys. There are no foreseeable risks to joining the online panel. There is no direct benefit to joining the panel (payment is not considered a benefit of research). It will take approximately 5 minutes to complete the registration form.

You can register now by clicking the button below!

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, alert: harvard yard closed to the public.

Please note, Harvard Yard gates are currently closed. Entry will be permitted to those with a Harvard ID only.

Last Updated: May 24, 7:32pm

Open Alert: Harvard Yard Closed to the Public

students in a lab with a professor. they are all wearing lab coats

Unlock Your World

From laboratory study to archival research to investigations in the field, Harvard students engage in world-class research across all disciplines and make groundbreaking contributions to their fields.

With support from a variety of funding sources, students collaborate with renowned faculty researchers whose work has been featured in top journals and awarded prestigious grants. Whether you assist your professor or lead your own project, you'll receive guidance, support, and the benefit of their expertise.

Research Opportunities

Are there research opportunities for undergraduates.

Yes - available to students as early as their freshman year. You may find research projects through individual inquiries with departments and professors, through the Harvard College Research Program (HCRP), or through the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program (MMUF). The Faculty Aide Program , run by the Student Employment Office, links professors to undergraduates interested in becoming research assistants. Read more about HCRP and MMUF on the Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships website , and find additional opportunities on the Student Employment Office website .

Expanding Our Campus

The state-of-the-art Science and Engineering Complex expands Harvard's campus with an additional 500,000 square feet of classrooms, active learning labs, maker space, and common areas.

Term-Time Research

During the academic year, you can conduct research for credit, as determined by the director of undergraduate study in each department.

Students can also receive funding from one of many sources. Additionally, many faculty members across academic departments hire students directly to serve as research assistants.

funding sources

Harvard college research program.

The Harvard College Research Program (HCRP) provides term-time and summer grants for students conducting independent research in collaboration with a faculty mentor.

Faculty Aide Program

The Faculty Aide Program (FAP) provides half of a student’s total wages when working for an approved faculty member as a research assistant.

Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program

The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program (MMUF) provides a term-time stipend, as well as the option for summer research funds, to a group of approximately 20 juniors and seniors, selected in the spring of their sophomore years.

Laboratories

Summer Research

Harvard offers many residential research programs for students staying on campus during the summer. In addition, funding is available to support independent research locally, domestically, and internationally.

Building Learning through Inquiry in the Social Sciences

Building Learning through Inquiry in the Social Sciences (BLISS) is a 10-week program for students working with Harvard faculty on research projects in the social sciences. BLISS provides a stimulating, collegial, and diverse residential community in which students conduct substantive summer research.

Harvard College-Mindich Program in Community-Engaged Research

The Harvard College-Mindich Program in Community-Engaged Research (PCER) introduces students to the field of engaged scholarship, which seeks to advance the public purpose of higher education through scholarship that has impact within and beyond the academy.

Program for Research in Markets and Organizations

The Program for Research in Markets and Organizations (PRIMO) is a 10-week summer program that allows students to work closely with Harvard Business School faculty on projects covering topics from business strategy to social media, and from innovation management to private equity.

Program for Research in Science and Engineering

The Program for Research in Science and Engineering (PRISE) is a 10-week summer program that aims to build community and stimulate creativity among Harvard undergraduate researchers in the life, physical/natural, engineering, and applied sciences.

Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program

The Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program (SHARP) is a 10-week summer immersion experience in which students engage in substantive humanities- and arts-based research designed by Harvard faculty and museum and library staff.

Summer Undergraduate Research in Global Health Program

The Summer Undergraduate Research in Global Health Program (SURGH) is a 10-week summer program in which students research critical issues in global health under the direction of a Harvard faculty or affiliate mentor. Participants live in a diverse residential community of researchers, attend weekly multidisciplinary seminars with professionals in the global health field, and make connections beyond the traditional health sphere.

Summer Program for Undergraduates in Data Science

The Summer Program for Undergraduates in Data Science (SPUDS) is a 10-week summer data science research experience that encourages community, creativity, and scholarship through applications across the arts, humanities, sciences and more fields. Students interested in mathematics, statistics, and computer science collaborate on projects with a Harvard faculty host.

Voyage of Discovery

The Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships helps students navigate the research opportunities available here on campus, in the Cambridge area, and around the world.

Related Topics

College offices.

Harvard College offices provide support and help students to navigate everything from academics to student billing.

From physical spaces to funding, Harvard provides the support for students to follow their curiosity as they investigate and explore their world.

Academic Environment

Explore what makes Harvard such a unique place to live and learn.

Toggle Academics Submenu

Be part of tomorrow's healthcare breakthroughs

When you participate in a University of Minnesota study, you can help create a healthier future.

Find a study that's right for you

Advanced search, how you could make a difference.

- Help someone who needs it - Your participation in research could benefit a friend, a family member, or someone across the world.

- Make healthcare better for everyone - Healthcare is safer and more effective for everyone when people from different backgrounds, ages, genders, races and ethnicity participate in health research.

- Help researchers solve health problems - Volunteers play a key role in research and make new discoveries possible. Your participation helps researchers find new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease.

Featured research opportunities

Research at the CSC

The M Health Fairview Clinics and Surgery Center houses a wide range of specialists all in one, easy to access location on the U of M campus. Find studies taking place in this unique space where clinical care and research connect.

Healthy volunteers needed

Healthy volunteers play a vital role in research. Some research studies rely on participation from healthy volunteers (people who do not have the condition being studied) to provide data that is used as a comparison for patient groups.

.png)

Rare disease studies

Did you know that 70% of genetic rare diseases start in childhood? Share U of M rare disease studies, and help generate change for the 300 million people worldwide living with a rare disease.

Research participants have rights

Every study is different. Some studies are looking for people with certain conditions, while others are open to healthy volunteers. Some studies involve visits to a clinic, while others can be done online.

One thing that is common to all research is that the decision to participate is personal and always voluntary. Whether agreeing to share your medical data or consenting to an experimental treatment, we want you to know that research participants have rights and protections.

Click the link below to read the research participants' Bill of Rights and to learn more about how the University of MInnesota reviews, approves and monitors research studies.

Join a national registry!

ResearchMatch

ResearchMatch.org connects volunteers with research studies across the country. Volunteers of any age, race, ethnicity, or health status are invited to join. Log on, register, and receive emails when studies might be a good fit for you.

ivetriedthat

35 Paid Online Research Studies Seeking Participants

How can one participate in paid online research studies and get paid for your brain, your health, and your opinions?

- Inbox Dollars - Get paid to check your email. $5 bonus just for signing up!

- Survey Junkie - The #1 survey site that doesn't suck. Short surveys, high payouts, simply the best.

- Nielsen - Download their app and get paid $50!

Well, you’re in the right place.

Today, let’s look at 35 different opportunities to get paid as a participant in research studies.

Types of Paid Online Research Studies

A medical study involves a group of people within an age group, gender, race, ethnic group, or individuals with the same specific health issues.

Participating in these studies often involves answering a combination of interviews, tests, surveys, or experimentation to be able to answer questions on how to diagnose, treat, prevent, or cure health disorders and diseases.

Aside from paid medical studies, market research makes use of paid online research to find out what customers want or need from various products and companies.

The cool thing about paid online research studies available today is that even if you are not a part of the target audience, you can still participate in the study in another capacity.

Online research studies can be either quantitative or qualitative.

Quantitative studies are the ones with static, pre-planned answers. A questionnaire with multiple-choice answers is a good example of this study. It is made as such so that the researcher can easily analyze the results.

Qualitative studies are a bit more complex since they involve open-ended answers.

However, this type of study ends up with better data. Focus groups and interviews are both methods used in qualitative studies.

How Much Can You Earn from Paid Research Studies?

Imagine earning up to $1,000 just for sharing your opinion, review of a product, or thoughts about a particular experience without even stepping out of the house.

You don’t even have to spend a cent to participate in these research studies.

Most of the time, you’d only have to be at least 18 years old and currently live in the US.

Even when you’re below 18 years old, researchers sometimes allow you to participate as long as you had a waiver from your parent or legal guardian.

The amount you earn from joining research studies depend on the following:

- Method of research — Did you join a focus group? Answered a lengthy interview? Filled out a survey form?

- Length of study — Some interviews only take an hour and earn you $150. Some focus groups could take several sessions and end only after several weeks.

- Type of payment — Not all companies pay cash. Some use PayPal, while others prefer checks, gift cards, prepaid cards, and so on.

Quick surveys can be as little as $10 and high as $100.

Focus group sessions range between $50 and $500 per session.

Interviews can earn you somewhere from $50 to $400 for an hour of your time.

Simply put, the amount you’ll be paid will vary from study to study.

Join These to Start Making Money Today!

Before digging into the list below, I suggest you sign up for the 3 best focus group/market research companies.

Anyone can participate and you will be invited to take part in research studies, focus groups, and product testing opportunities.

These companies pay in cash and offer cash signup bonuses to get you started.

- SurveyJunkie - Get paid CASH to share your thoughts on some of the world's biggest brands.

- Branded Surveys - Work directly with companies like Nike, Samsung, Amazon, and Disney to improve their product lines.

On to the list!

35 Ways to Get Paid for Research Studies Online

The following universities have year-long research studies in a wide range of topics.

1. Northwestern University Department of Psychology

Earn from $10 to $40 an hour if you participate in one of the school’s online studies.

The studies change regularly and vary widely from topics such as phone usage, changes in thoughts and feelings, Artificial Intelligence, sleeping patterns, psychosis, aging, and even products like hearing aids.

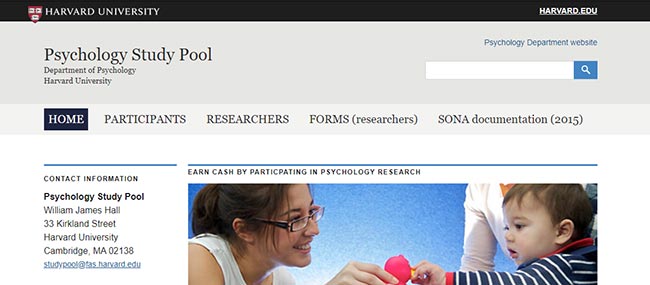

2. Harvard University Psychology Study Pool

Join Harvard’s Psychology Study Pool and earn from $10 to $25 an hour, paid via gift cards.

The online studies are available year-round for both Harvard students and guests.

3. Carnegie Mellon University

If you’re at least 18 years old, can read and speak English, and have never joined any research studies at the Center for Behavioral and Decision Research at Carnegie Mellon, you can sign up for their paid online research studies.

Topics range from personal beliefs, attitudes, decision-making, human judgment, interpersonal perceptions, and group performance, among others.

You’ll earn $8 an hour, paid in gift cards. Each study takes anywhere from 5 and 20 minutes.

Paid participants are needed for in-person studies in labs on campus, but may sometimes be able to participate online on a home computer.

Note that only students are accepted (ID will be requested).

4. Center for Decision Sciences Columbia Business School

For participating in an online survey or study, you can earn $16 an hour, as long as you’re 18+ years old and have a PayPal or Amazon.com account to receive payments.

No need to be a student at Columbia Business School, but you need to register in the CDS Virtual Lab Online Panel.

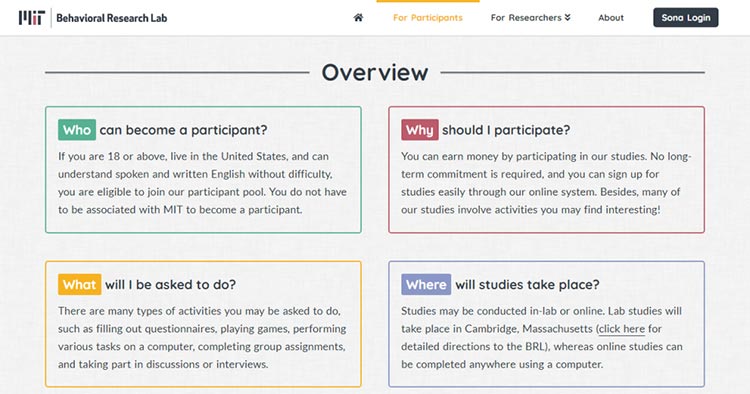

5. MIT Behavioral Research Lab

There are in-person and paid online research studies available at MIT.

Payment amounts vary from study to study, but participants usually earn $11 to $20 per hour for online studies.

Anyone aged 18 or older, residing in the United States, and proficient in spoken and written English can join the BRL participant pool.

Membership is open to all; you don’t need any association with MIT to participate. Other requirements may be needed for studies requiring specific respondents.

6. University of Maryland Robert H. Smith School of Business

As long as you’re a current Smith student (and eligible for certain studies), you can get paid for research studies online here.

Make sure you create an account, sign up for the studies that you want to participate in, and get paid once you fulfill your role.

7. Purdue University

You can find a lot of paid online studies here.

Currently, they have studies on Parkinson’s disease (and other neurodegenerative diseases), flavored water, biosensors, mushroom nutrition, linguistics, cancer, and so on.

Participants are paid somewhere between $10 and $500.

What’s great about Purdue University is that the studies are varied and open to the public.

8. Stanford Graduate School of Business

You’ll be paid up to $25 an hour for online research studies, but you’d have to be eligible and complete a prescreen form.

You also can’t participate in the same study more than once.

9. UCLA Anderson School of Management

The behavioral lab has some paid online studies, if you’re interested in topics like consumer behavior, organizational behavior, judgment, and other similar topics.

Most studies here pay from $10 to $20 an hour.

They also have in-lab and in-person studies.

10. Boston University Behavioral Lab

If you’re interested in human behavior and is willing to participate in online studies, try to join if you’re eligible.

These studies pay between $10 and $20 an hour.

The studies from Boston University’s Behavioral Lab is open to both BU students and the general public.

11. University of Maryland Department of Psychology

You need to create an account at the SONA System website to see available research studies.

Each of the studies have different eligibilities and payment.

12. University of Nebraska-Lincoln

This college holds a wide range of research studies revolving MRI research, human brain, behavior, and so on.

There are studies exclusively for seniors, and those that are for teens.

There are two ways to volunteer for these studies:

- Join the CB3 Research Participant Volunteer Registry (and wait for them to e-mail you)

- Pick the study and contact researchers directly.

Pay can go as high as $80 per study.

13. American University Psychology Department

Topics vary widely, but they are related to psychology and human behavior.

You can earn up to $20 an hour for just filling out a form as a smoker’s first-hand experience during stressful situations.

14. Respondent.IO

This next one isn’t a university, but it’s a comprehensive resource if you plan to participate in numerous market research and other online studies.

Pay ranges from $25 to $200.

Eligibility requirements vary between studies.

Make sure to check details and never pay to join a focus group or study.

15. Brand Institute

Want to be at the forefront of the pharmaceutical industry?

Join consumer market research panel groups by signing up with Brand Institute.

16. mindswarms

It’s sort of like an interview since you are required to answer ten questions with a video.

In exchange for your thoughts, you’ll be paid $50.

Earn somewhere between $50 and $250 by participating in healthcare or consumer market research studies.

18. Probe Market Research

The company pays people for online, phone or group interviews about their clients’ products, services, ads, or other campaigns.

Payment goes as high as $400.

19. Penn State University

(Quick shoutout to my Alma Mater… We Are!)

… and they are seeking just about anyone who’s alive to participate in a research study. With over 200 current open studies, odds are, you’ll qualify for something they have available.

Keep an eye out for “Total Compensation” to see just what the study pays.

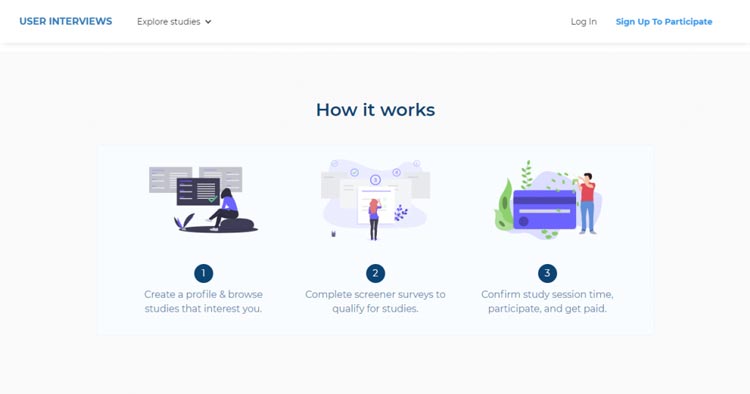

20. User Interviews

Get paid for your feedback on real projects.

Create an account by filling up a form and wait for project invitations if you’re eligible.

There are online and in-phone interviews available.

21. Yale School of Management

If you live anywhere near Yale campus, be sure to sign up for their newsletter as they frequently put out requests for both in person and paid online research studies.

You will be paid, in cash, at the completion of your study.

They also have a Facebook group that announces when new studies are available to participate in.

22. Georgetown University Department of Psychology

Georgetown’s Department of Psychology is regularly looking for both students and non-students alike to participate in studies.

Average pay will run you about $10 per hour, so it can be some nice change to pick up in your spare time.

Their research includes personality, memory, and impulse control tests to name a few.

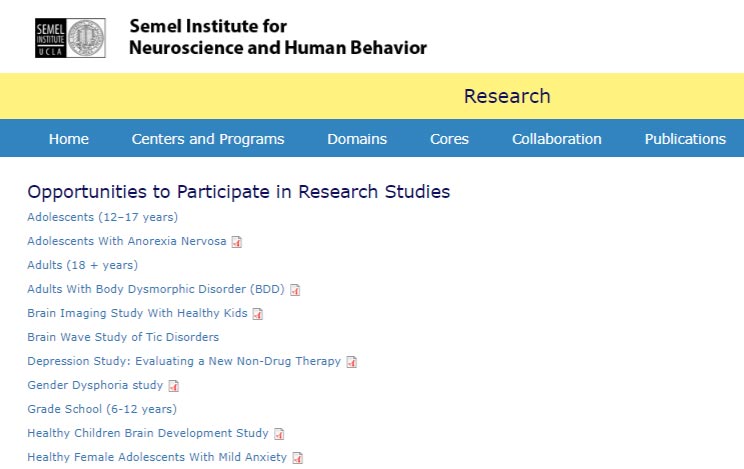

23. UCLA Semel Institute

UCLA offers both in-person and online research studies to check out.

They have a massive list of open opportunities for you to click through. The highest paying ones often need you to come into their offices for scans and interviews, but there are a lot of remote positions available too.

24. PingPong

Web designers and developers working on websites and applications value the input of real-life users and are willing to pay for these users’ opinions and insights

You can get paid anywhere from €15 to €40 per hour and even up to €100 for special projects.

Payment is credited through Transferwise or PayPal.

25. American Consumer Opinion

Yet another survey site, American Consumer Opinion (ACOP) pays you for your answers to their survey questions.

You can even get paid up to $100 if you fit a certain demographic and able to participate in special projects.

Research studies on this site may not be constantly available, though. It’s best to check back frequently.

26. Recruit and Field

Recruit and Field is a market research company that hosts paid online research studies all around the US and even in international locations.

They look for participants from any gender and age for their studies, including professionals and medical professionals (doctor, nurse, lab technician).

They normally pay via PayPal but also offer Amazon or digital gift cards.

The pay ranges from $100 to $275 for phone interviews, online surveys, and sometimes in-home product testing.

27. Focus Group

Focus Group is an aptly named online community comprised of participants interested in sharing opinions and views on popular products and brands through in-person, telephone, or online surveys.

The pay ranges from $75 to $200, and specialized health studies may pay more.

28. 20|20 Panel

Since 1986, 20|20 Panel has been recruiting participants to share their opinion on various companies.

They specialize in qualitative market research, which is achieved via in-person or online roundtable discussions. You can get paid from $50 to $350 to participate in these discussions.

They also send out quick surveys for which you can get paid smaller amounts (from $1 to $10).

29. FindFocusGroups

Wouldn’t it be great if there were a directory of all the paid research opportunities in the country?

FindFocusGroups is probably the closest one, as it lists more than 75,000 verified and legitimate focus groups in the country.

It’s quite simple to search by city and state, and check the information for details on whether the discussions are online or in-person.

It’s difficult to know how much the average payment would be, but upon browsing the first few studies on the homepage, they range from $50 to $300.

30. SIS International

SIS International conducts focus group discussions in cities all over the US and globally and collects consumer feedback on anything from appliances, skincare products, gadgets, and just about anything.

Rates range from $25 to $200 for 2 to 3 hours of your time.

31. Apex Focus Group

Apex Focus Group connects regular people like you and me with researchers, who will pay for participants to join clinical research trials, phone interviews and focus groups.

As a participant at any Apex Focus Group study, you can be paid up to $750 a week.

Online and in-person studies are available.

32. Fieldwork

If you live near New Jersey, New York City, Phoenix, San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, or Minneapolis, you can participate in current Fieldwork research studies.

Most of the paid focus groups are face-to-face (but online are sometimes available).

Each study lasts about 1 or 2 hours. Participants earn between $75 and $100 for their time.

33. Rare Patient Voice

This company mostly looks for participants who have rare diseases and medical conditions. As such, only eligible people can benefit from the studies.

However, anyone who qualifies will receive $120/hour.

You can share your views via online surveys, clinical trials, or web-assisted phone interviews.

34. ClinicalTrials.gov

The federal government continually seeks individuals willing to participate in clinical trials testing different medications and treatments.

Studies are often conducted by the National Institutes of Health.

You can check out a list of ongoing clinical trials at clinicaltrials.gov.

Unlike other paid online research studies on this list, DScout is an app you can download.

You need to register to become a “scout” and participate in research “missions,” which will earn you money after completion.

DScout studies are usually 1-on-1 interviews or video responses, so you’d have to be comfortable in front of the camera.

Missions pay from $50 to $100, each lasting about 30 minutes.

Can I turn these Paid Online Research Studies into a Full-Time Job?

While paid online studies are highly interesting and offer legitimate side cash, this gig cannot replicate the steady income and benefits you can get with a full-time job.

You’d have to consider that many research studies:

- have eligibility requirements (which means you’re not guaranteed a slot every time)

- cannot be joined twice (once you’ve participated in a specific study, you can’t do a repeat)

- have varying payments (there’s no stability in such income)

I do think it’s a legitimate side gig if you’re in between jobs or have a lot of free time on your hands.

You can also get paid answering surveys , joining focus groups , or testing products .

READ THIS NEXT: The EASIEST ways to make money online. See how.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

More Ways to Make Money

The HOTTEST New Way to Make Money in 2021

This is one of the best ways to make real money online. Don't pass this one up.

Continue Reading

100 Different Side Hustles to Fill Your Pockets with Cash

Everyone loves easy ways to make money online. You already have the skills. Turn those hidden talents into extra money from side gigs in 2021.

How to Sell Breast Milk and Make $2500 Per Month

Did you know that you can sell breast milk for up to $2.50 per ounce? It’s true! Here’s how to get started and make some decent side cash.

20 Online and Offline Summer Jobs for Teachers

Are you a teacher by profession? This list of doable summer jobs for teachers is what you need to earn side cash this summer break.

9 YouTube Monetization Alternatives for Your Online Biz

Here are 9 YouTube monetization alternatives if you plan to switch platforms or pick YouTube to launch your video creation journey online.

Search Stanford:

Other ways to search: Map Profiles

Main Content

From Nobel Prize winners to undergraduates, all members of the Stanford community are engaged in the creation of knowledge.

The Research Enterprise

Stanford’s culture of collaboration drives innovative discoveries in areas vital to our world, our health, and our intellectual life.

Interdisciplinary Research

At the intersection of disciplines is where new ideas emerge and innovative research happens.

Stanford Research

Institutes, Labs & Centers

Fifteen independent labs, centers, and institutes engage faculty and students from across the university.

Independent Laboratories, Centers and Institutes

Other Research Centers & Labs

Academic departments sponsor numerous other research centers and labs.

Listing of Stanford Research Centers

Where Research Happens

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

SLAC is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory operated by Stanford, conducting research in chemistry, materials and energy sciences, bioscience, fusion energy science, high-energy physics, cosmology and other fields.

Hoover Institution

The Hoover Institution, devoted to the study of domestic and international affairs, was founded in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer class of 1895 and the 31st U.S. president.

Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment

Working toward a future in which societies meet people’s needs for water, food and health while protecting and nurturing the planet.

Stanford Woods Institute

Stanford Humanities Center

Advancing research into the historical, philosophical, literary, artistic, and cultural dimensions of the human experience.

Stanford Bio-X

Biomedical and life science researchers, clinicians, engineers, physicists and computational scientists come together to unlock the secrets of the human body.

Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI)

Understanding problems, policies and processes that cross borders and affect lives around the world.

Freeman Spogli Institute

Stanford University Libraries

Stanford is home to more than 20 individual libraries, each with a world-class collection of books, journals, films, maps and databases.

Online Catalog

SearchWorks is Stanford University Libraries’ official online search tool providing metadata about the 8 million+ resources in our physical and online collections.

SearchWorks

Undergraduate Research

Undergraduate Advising and Research (UAR) connects undergraduates with faculty to conduct research, advanced scholarship, and creative projects.

Research Administration

The Office of the Vice Provost and Dean of Research, provides comprehensive information about the research enterprise at Stanford.

Find A Researcher

Search and read profiles of Stanford faculty, staff, students, and postdocs. Find researchers with whom you would like to collaborate.

Stanford Profiles

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Research & Faculty

You are in a modal window. Press the escape key to exit.

- News & Events

- See programs

Common Searches

- Why is it called Johns Hopkins?

- What majors and minors are offered?

- Where can I find information about graduate programs?

- How much is tuition?

- What financial aid packages are available?

- How do I apply?

- How do I get to campus?

- Where can I find job listings?

- Where can I log in to myJHU?

- Where can I log in to SIS?

- University Leadership

- History & Mission

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Notable Alumni

- Hopkins in the Community

- Hopkins Around the World

- News from Johns Hopkins

- Undergraduate Studies

- Graduate Studies

- Online Studies

- Part-Time & Non-Degree Programs

- Summer Programs

- Academic Calendars

- Advanced International Studies

- Applied Physics Laboratory

- Arts & Sciences

- Engineering

- Peabody Conservatory

- Public Health

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Plan a Visit

- Tuition & Costs

- Financial Aid

- Innovation & Incubation

- Bloomberg Distinguished Professors

- Undergraduate Research

- Our Campuses

- About Baltimore

- Housing & Dining

- Arts & Culture

- Health & Wellness

- Disability Services

- Calendar of Events

- Maps & Directions

- Contact the University

- Employment Opportunities

- Give to the University

- For Parents

- For News Media

- Office of the President

- Office of the Provost

- Gilman’s Inaugural Address

- Academic Support

- Study Abroad

- Nobel Prize winners

- Homewood Campus

- Emergency Contact Information

We are America’s first research university , founded on the principle that by pursuing big ideas and sharing what we learn, we can make the world a better place. For more than 140 years, our faculty and students have worked side by side in pursuit of discoveries that improve lives.

What kinds of discoveries? We made water purification possible, launched the field of genetic engineering, and authenticated the Dead Sea Scrolls. We invented saccharine, CPR, and the supersonic ramjet engine. Our efforts have resulted in child safety restraint laws; the creation of Dramamine, Mercurochrome, and rubber surgical gloves; and the development of a revolutionary surgical procedure to correct heart defects in infants.

The research opportunities here are just endless. That’s really what I was looking for, a place where it’s very easy to do research .

Researchers at our nine academic divisions and at the university’s Applied Physics Laboratory have made us the nation’s leader in federal research and development funding each year since 1979. Those same researchers mentor our inquisitive students—about two-thirds of our undergrads engage in some form of research during their time here.

Research isn’t just something we do—it’s who we are. Every day, our faculty and students work side by side in a tireless pursuit of discovery, continuing our founding mission to bring knowledge to the world.

Zika’s impact on early brain development

Johns Hopkins researchers contribute to breakthrough study showing likely biological link between Zika virus and microcephaly, a birth defect linked to abnormally small head size and stunted brain development in newborns.

- Johns Hopkins University

- Address Baltimore, Maryland

- Phone number 410-516-8000

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University. All rights reserved.

- Schools & Divisions

- Admissions & Aid

- Research & Faculty

- Campus Life

- University Policies and Statements

- Privacy Statement

- Title IX Information and Resources

- Higher Education Act Disclosures

- Clery Disclosure

- Accessibility

Participate in Studies

Help us further our discoveries of how the mind works

You do not have to be affiliated with Stanford University to participate in Psychology research. The majority of our paid studies take place on the Stanford campus, but we also offer opportunities to take part in our experiments online. We appreciate your participation, which is vital to the continued success of our department. Out of consideration for our researchers' time and resources, we ask that you please only sign up for studies you can attend and that you cancel any appointments you are unable to make.

Stanford students in Psychology classes can not receive course credit for participating in paid studies. Please check your course syllabus for participation instructions.

Sign up to participate

Existing participants can log in to browse our current studies and sign up for open timeslots.

Research Courses

- Social Sciences

Prescription Drug Regulation, Cost, and Access: Current Controversies in Context

Understand how the FDA regulates pharmaceuticals and explore debates on prescription drug costs, marketing, and testing.

Cancer Genomics and Precision Oncology

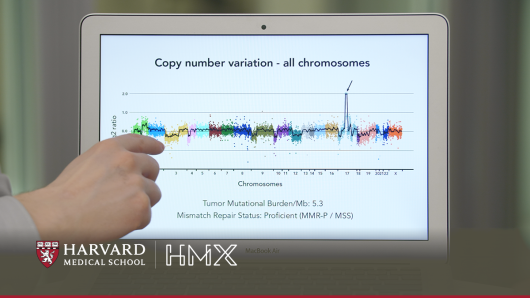

Learn how cancer treatment is evolving due to advances in genetics..

Gene Therapy

Explore recent advances in gene therapy and learn about the implications for patient care..

Immuno-oncology

See how the immune system is being used to improve cancer treatment..

Clinical Drug Development

Learning about the process of clinical drug development has important implications for anyone working in health care and related sectors.

Foundations of Clinical Research

This Harvard Medical School six-month, application-based certificate program provides the essential skill sets and fundamental knowledge required to begin or expand your clinical research career.

Global Clinical Scholars Research Training

This Harvard Medical School one-year, application-based certificate program provides advanced training in health care research and methods.

Join our list to learn more

Be part of tomorrow's health care breakthroughs

When you participate in a Penn State University study, you can help create a healthier future.

COVID-19 studies that need volunteers

Penn State University has several clinical trials to test experimental medicines that could help those with coronavirus.

Find a study that's right for you

Make a difference. get involved..

Participating in research is one of the most powerful things you can do to be part of tomorrow's health care breakthroughs. Penn State is always looking for people who are willing to participate in studies, so that our researchers can better understand how to diagnose, treat, and prevent diseases and conditions.

Use this Studyfinder website to quickly and easily identify studies across Penn State that need volunteers. Every study is different - some are looking for people with a specific condition, while others need healthy volunteers ( read more about that here ). That's why we've created search filters to help you find the study that's right for you. You can also filter by age, and search by keyword to find studies focused on specific conditions and diseases. Typing in a location, such as State College or Hershey, will also help you filter studies of interest.

You can also get answers to your questions about clinical research here .

By getting involved with research, you can help transform the lives of millions.

Research at Penn State University

Penn State University has research studies on a wide range of health issues, from cancer and diabetes to prevention and women's health.

Every study is different. Some studies are looking for people with certain conditions, while others are open to healthy volunteers. Some studies involve visits to a clinic, while others can be done online.

More ways to get involved

Explore your interests. Make a difference.

Important scientific discoveries start with you . Research studies couldn’t happen without the contributions of people from all walks of life, from all around the world! You can join regardless of your age or health status.

Community participants

Participate in studies you care about to advance research and improve our communities.

Researchers

Feature your study on the portal for an easier, quicker, and more successful recruitment process.

Explore the portal with students to analyze and participate in research projects across campus.

Research Plus Me makes participating in research easier than ever .

Find a variety of research studies and topics you care about – including health and medicine, the humanities, business, and more!

Match with studies based on your interests, through notifications and a personalized study feed.

Participate

Join a study easily and securely.

Our commitment to privacy and data protection

Your data will never be sold, lent or otherwise given to any vendor at any time. Your data will be stored in an online secure database. Individual research projects detail specifics about the data they collect and how it will be used to advance scientific knowledge. For more information, read our privacy policy below.

Center for Behavioral and Decision Research

Participate in Research

Cbdr is always looking for new research study participants..

Paid participants are needed for in-person studies in labs on the Carnegie Mellon University campus only. Therefore, we ask that only residents of Pittsburgh request a CBDR participant account. Please be sure to read the participation policies below before entering your information to request a CBDR account for research participation.

Lab Expectations of Participants

- Participants must present a valid state-issued or student photo ID in order to participate in each in-person study. The name on the valid ID must exactly match the spelling of the name used to sign up for an account. Any participant who presents an ID with a name that does not exactly match the name on their account will not be able to participate in the study and will not be compensated.

- Participants must show up on time to participate in studies; participants who show up after the listed study starting time may not be able to participate and will not be compensated.

- Participants are expected to attend all study sessions for which they sign up, or to cancel sign-ups on the website at least 24 hours in advance. Missing a study without online cancellation will result in an unexcused no-show. Participants who accumulate three unexcused no-shows will be banned from participating in studies for at least three months.

- Participants are asked to cancel or reschedule their study session if they are feeling unwell. This includes but is not limited to symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, fatigue, or any other signs of illness.

- Participants and researchers are required to maintain an environment of respect. Participants may not be under the influence of alcohol or illicit drugs while participating in studies. Use of vulgar or discriminatory language, threatening behavior, inappropriate communication, system abuse, etc. will result in permanent restriction from the system and from participation in studies.

Payment Details

For in-person studies, participants will be compensated immediately with cash or gift cards. Payment usually averages around $10 per hour for in-person studies. For online studies, p articipants will typically be compensated with online gift cards within one to two weeks after the study closes. Payment usually averages around $8 per hour for online studies, or participants may be e ntered into a lottery for a chance to win a larger prize. Payment information for each study can always be found in the study description. Participants must be a resident of the United States in order to recieve remote compensation.

CMU students participating in the Research Participation Program may also earn course credit for participating in specifically labeled studies. These CREDIT studies may not be completed for cash payment unless explicitly stated. Studies labeled "CREDIT" are therefore intended for CMU students only.

Study Topics

Studies vary widely across the broad spectrum of behavioral and decision research. Examples of topics studied are personal attitudes and beliefs, human judgment and decision-making, preferences, interpersonal perceptions, group performance, interaction with computers and machines, and perceptions of public policy.

Study Length

Each individual study posting will always contain the anticipated length. Online studies are typically shorter, ranging from 5 minutes to an hour (or longer). In-person lab studies are typically longer, ranging from 30 minutes to 1.5 hours. Some studies require multiple sessions or may fall outside of these ranges.

Contact the Lab Manager .

Sign In (Sona)

Request an Account

Eligibility

- Must be 18 years old or older

- Must be a resident of the United States

- Must not already have a participant account

- May not participate in any individual study more than once

- Must complete a prescreen form prior to signing up for studies

- Must speak and read English

- Must NOT be PhDs in Economics, Psychology, Organizational Behavior, or Marketing

Request a CBDR Account

Once you have read the participation policies you may sign up to create an account. Account creation may take up to 72 weekday hours. Do not resubmit information — this will return an error message. If you are a Carnegie Mellon student, please register with your CMU email address so that we may verify your student status. We are unfortunately unable to accept participants that are not residents of the United States at this time.

Once you receive your account information, you will be able to view and sign up for studies through our Sona Systems website .

For general questions about the participation pool, please first look at the FAQ section on the Sona Systems website .

Any questions about a particular study (including but not limited to questions about compensation, preparation, meeting time, eligibility, etc.) should be directed to the researcher(s) listed in the study posting online. In the case that a participant feels any matter must be reviewed by the lab system administrators, participants may email the CBDR lab manager at [email protected] .

Affiliate Schools

- Tepper School of Business

- Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences

- Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy

Office of Graduate & Professional Studies

Contact graduate admissions.

True Blue Summer Hours

Our office will be closed on fridays from may 17th through august 9th, nau office of graduate and professional studies, grad school, elevated.

A better world is waiting. If you’re ready to pursue your next opportunity—whether intellectual, professional, or personal—then Northern Arizona University’s flexible, challenging graduate programs will help you get to your next level. Study in Flagstaff, online or statewide.

Launch Northern Arizona University – Office of Graduate & Professional Studies Welcome

Graduate degrees and programs with a unique vantage point

Already an NAU student? Climb higher with an accelerated program that allows you to start earning your master’s while completing your bachelor’s degree.

Explore by degree level

Ready to take your next step? Learn about Office of Graduate & Professional Studies admissions.

Admissions requirements

Wondering if you’re eligible, or how to apply? Get more information.

International admissions

Want to join our community of international scholars? Discover how.

Paying for graduate school

Scholarships

Financial aid

Mailing Address

Social media.

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2024

The role of medical schools in UK students’ career intentions: findings from the AIMS study

- Tomas Ferreira 1 , 3 ,

- Alexander M. Collins 2 , 3 ,

- Arthur Handscomb 3 ,

- Dania Al-Hashimi 4 &

the AIMS Collaborative

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 604 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

313 Accesses

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

To investigate differences in students’ career intentions between UK medical schools.

Cross-sectional, mixed-methods online survey.

The primary study included all 44 UK medical schools, with this analysis comprising 42 medical schools.

Participants

Ten thousand four hundred eighty-six UK medical students.

Main outcome measures

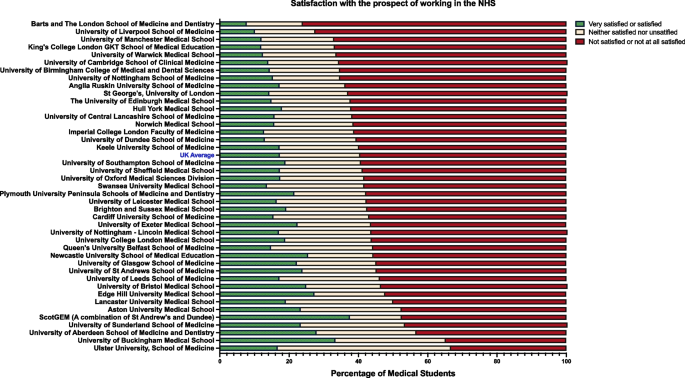

Career intentions of medical students, focusing on differences between medical schools. Secondary outcomes included variation in medical students’ satisfaction with a prospective career in the NHS, by medical school.

2.89% of students intended to leave medicine altogether, with Cambridge Medical School having the highest proportion of such respondents. 32.35% of respondents planned to emigrate for practice, with Ulster medical students being the most likely. Of those intending to emigrate, the University of Central Lancashire saw the highest proportion stating no intentions to return. Cardiff Medical School had the greatest percentage of students intending to assume non-training clinical posts after completing FY2. 35.23% of participating medical students intended to leave the NHS within 2 years of graduating, with Brighton and Sussex holding the highest proportion of these respondents. Only 17.26% were satisfied with the prospect of working in the NHS, with considerable variation nationally; Barts and the London medical students had the highest rates of dissatisfaction.

Conclusions

This study reveals variability in students’ career sentiment across UK medical schools, emphasising the need for attention to factors influencing these trends. A concerning proportion of students intend to exit the NHS within 2 years of graduating, with substantial variation between institutions. Students’ intentions may be shaped by various factors, including curriculum focus and recruitment practices. It is imperative to re-evaluate these aspects within medical schools, whilst considering the wider national context, to improve student perceptions towards an NHS career. Future research should target underlying causes for these disparities to facilitate improvements to career satisfaction and retention.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The rapidly changing dynamics of modern healthcare require a comprehensive understanding of the driving forces behind the career trajectories of doctors. As the landscape of patient care, healthcare policy, and medical technology continues to evolve, so too do the career choices of emerging doctors. These choices, as research increasingly demonstrates, are not solely the product of personal inclination or market demand but are deeply influenced by their experiences in medical school [ 1 ].

In recent years, the recruitment and retention of doctors within the United Kingdom’s (UK) National Health Service (NHS) have emerged as pressing concerns, requiring a detailed analysis of the factors influencing the career intentions of medical students [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. To address this, the Ascertaining the career Intentions of Medical Students (AIMS) study — the largest ever UK medical student survey — delineated the career intentions and underlying motivations of students, highlighting a significant trend towards alternative careers or emigration, influenced predominantly by remuneration, work-life balance, and working conditions within the NHS [ 5 ].

Expanding upon the insights of the AIMS study, we seek to further explore the nuanced differences in career intentions among medical students, in relation to their institutional affiliations, and foster a dialogue concerning medical education and workforce planning in the UK, highlighting the role of medical schools in shaping career trajectories. It is posited that these educational institutions, with their diverse curricular designs and teaching philosophies, may play a pivotal role in shaping the prospective professional trajectories of their students. Furthermore, the distinct socio-economic and cultural environments in which these schools are situated, and those of the students they attract, may also contribute to the varied perspectives and career aspirations of students. Historically, the field of medical education has been subject to a variety of pedagogical philosophies, curricular reforms, and institutional priorities. These variations across medical schools, while often subtle, can result in significant differences in the way students perceive their roles, responsibilities, and opportunities within the broader healthcare ecosystem. Literature suggests that various elements including the culture of a medical school and its sociocultural context play a significant role in shaping the professional aspirations of its students [ 1 , 6 ].

This manuscript seeks to identify and characterise these differences, with a focused analysis on how various medical schools in the UK might be influencing the career preferences and intended paths of their students. These findings may hold significant implications for various stakeholders within the healthcare sector. Policymakers could find guidance for strategic investments and resource allocation to areas anticipated to experience shortages, while educationalists could gain an opportunity for reflection on the potential influence of their institutions on student aspirations, thereby considering necessary adjustments. Furthermore, it affords insights for improved recruitment strategies, critical to ensuring the NHS’s continued role in the UK.

Study design

The AIMS study was a national, cross-sectional, multi-centre study of medical students conducted according to its published protocol and extensively described in its main publication [ 5 , 7 ]. Participants from 44 UK medical schools recognised by the General Medical Council (GMC) were recruited through a non-random sampling method via a novel, self-administered, 71-item questionnaire. The survey was hosted on the Qualtrics survey platform (Provo, Utah, USA), a GDPR-compliant online platform that supports both mobile and desktop devices.

Participant recruitment and eligibility

In an attempt to minimise bias and increase the survey’s reach to promote representativeness, a network of approximately 200 collaborators was recruited across 42 medical schools – one collaborator per year group, per school – prior to the study launch to disseminate the study. All students were eligible to apply to become a collaborator. This approach aimed to obtain a representative sample and improve our findings’ generalisability. The survey was disseminated between 16 January 2023 and 27 March 2023, by the AIMS Collaborative via social media (including Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn), word of mouth, medical student newsletters/bulletins, and medical school emailing lists.

Individuals were eligible to participate in the survey if they were actively enrolled in a UK medical school acknowledged by the GMC and listed by the Medical School Council (MSC). Certain new medical schools had received approval from the GMC but were yet to admit their inaugural cohort of students, so were excluded from the study.

Data processing and storage

To prevent data duplication, each response was restricted to a single institutional email address. Any replicated email entries were removed prior to data analysis. In cases where identical entries contained distinct responses, the most recent entry was kept. Responses for which valid institutional email addresses were missing were removed prior to data analysis to preserve the study’s integrity.

The findings of this subanalysis, and the AIMS study, were reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [ 8 ].

Quantitative data analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out with Microsoft Excel (V.16.71) (Arlington, Virginia, USA), and statistical inference was performed using RStudio (V.4.2.1) (Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Tables and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism (V.9.5.0) (San Diego, California, USA). ORs, CIs and p values were computed by fitting single-variable logistic regression models to explore the effect of various demographic characteristics on students’ career intentions. CIs were calculated at 95% level. We used p < 0.05 to determine the statistical significance for all tests.

Study population and exclusion

All current students of all year groups at UK medical schools recognised by the GMC and the MSC were eligible for participation. Brunel Medical School and Kent and Medway Medical School were excluded from this current analysis due to the limited number of respondents from these institutions ( n < 30), to avoid misrepresenting the career intentions and characteristics of their broader student populations.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Cambridge Research Ethics Committee (reference PRE.2022.124) on the 5th of January 2023. Prior to completing the survey, all participants provided informed consent. Participating medical schools were contacted prior to data collection to seek support and request permission to contact their students.

Demographics

In total, 10,486 students across all 44 UK medical schools participated in the survey. To enable comparison of students’ career intentions between medical schools, only 42 medical schools were considered due to the sample size gathered. The average number of responses per medical school was 244, with a median of 203 (IQR 135–281). Participants had a median age of 22 (IQR 20–23). Among the participants, 66.5% were female ( n = 6977), 32.7% were male ( n = 3429), 0.6% were non-binary ( n = 64), and 16 individuals chose not to disclose their gender. A detailed breakdown of participant characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, previous schooling, and course type, is illustrated in Supplemental Figs. 1 a-d.

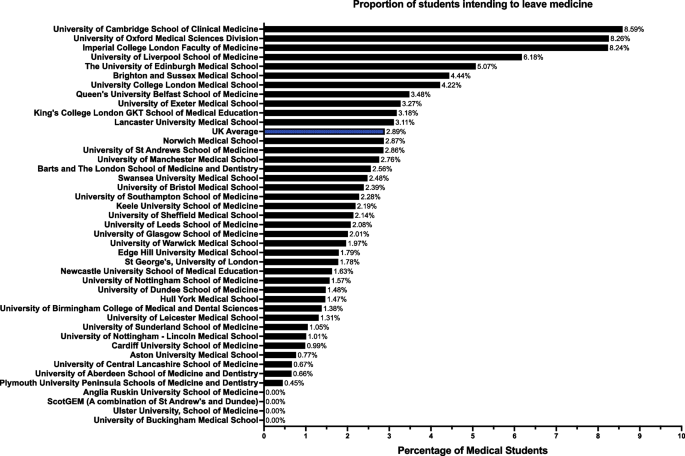

A total of 303/10,486 (2.89%, CI: 2.59, 3.23%) medical students intended to leave the profession entirely, either immediately after graduation ( n = 104/303, 34.32%, CI: 29.20, 39.84%), after completion of FY1 ( n = 132/303, 43.56%, CI: 38.1, 49.19%), or after completion of FY2 ( n = 67/303, 22.11%, CI: 17.8, 27.12%). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of these students throughout UK medical schools as a percentage of total response numbers per school. The medical schools of Cambridge, Oxford, and Imperial College medical schools had the highest proportion of students intending to leave the profession altogether.

Proportion of Medical Students Intending to Leave the Profession Across UK Medical Schools. The figure depicts the percentage of students at each UK medical school who intend to exit the medical field entirely. Percentages are calculated as a proportion of total respondents from each individual school

Furthermore, 32.35% of participating medical students ( n = 3392/10,486, CI: 31.46, 33.25%) expressed intentions to emigrate to practise medicine, either immediately after graduation ( n = 220/3292, 6.49%, CI: 5.71, 7.36%), after completion of FY1 ( n = 1101/3292 32.46%, CI: 30.90, 34.05%) or after FY2 ( n = 2071/3292, 61.06%, CI: 59.40, 62.68%). Figure 2 a demonstrates the distribution of these intentions across UK medical schools, relative to total response rates per school. Notably, Ulster University had the highest proportion of students considering emigration (45.45%), in contrast to Edge Hill, where 19.64% held similar intentions. Among students intending to emigrate, 49.56% ( n = 1681, CI: 47.88, 51.24%) planned a return to the UK after a few years abroad, while 7.87% ( n = 267, CI: 7.01, 8.83%) expected to return after completing their medical training abroad. The remaining 42.57% ( n = 1444, CI: 40.92, 44.24%) expressed no plans to return to practise in the UK, as demonstrated in Fig. 2 b.

Proportion of Medical Students Intending to Emigrate Across UK Medical Schools (a) and Return Prospects (b). a illustrates the proportion of students from each UK medical school who intend to emigrate for medical practice, relative to total respondents from each school. b delineates the return prospects among students planning to emigrate

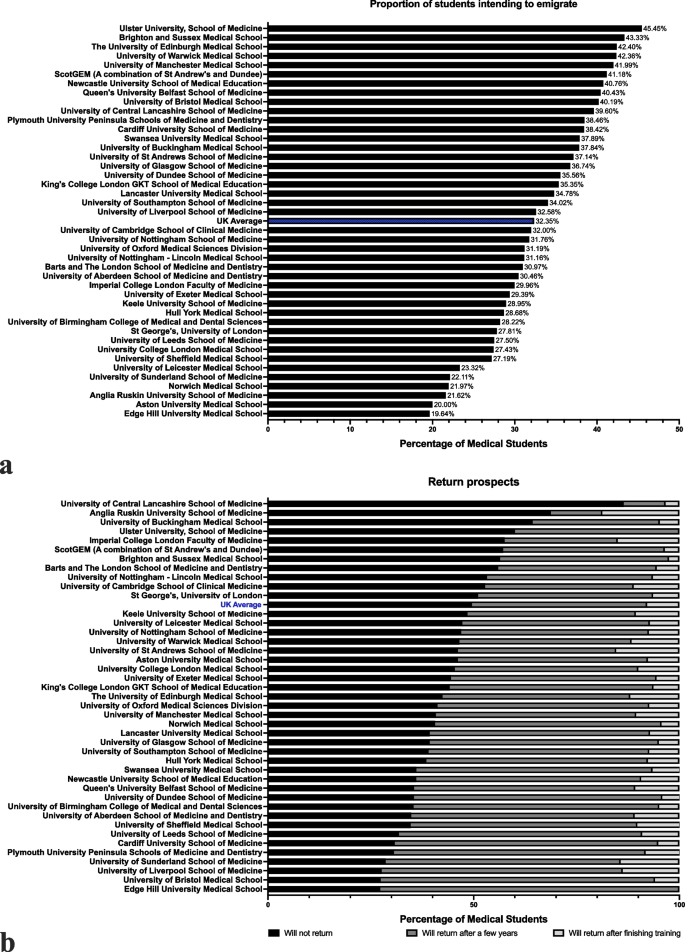

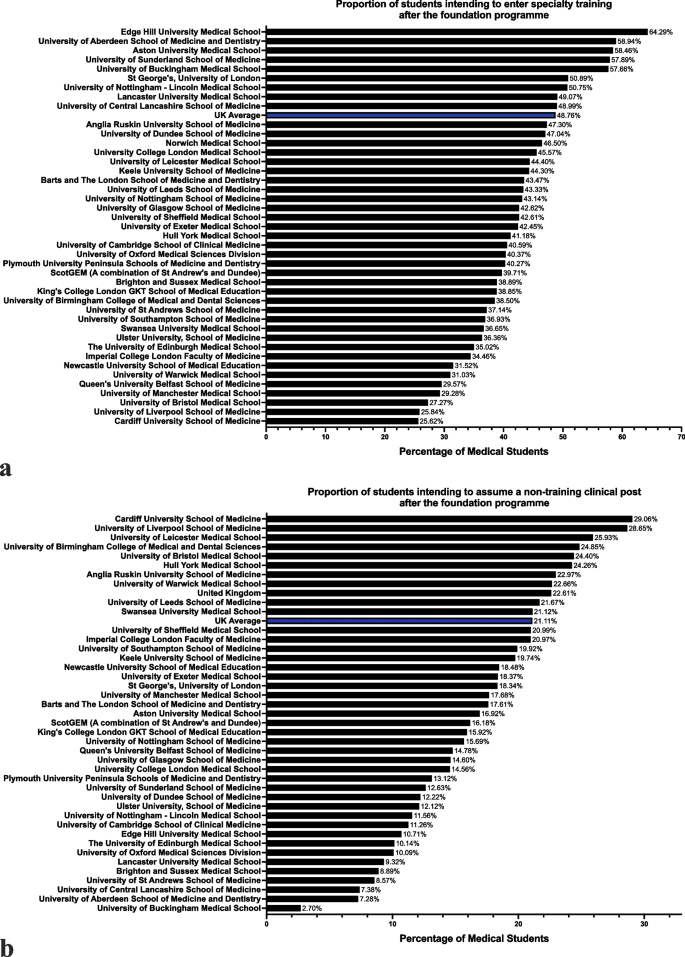

Of the 8806 respondents intending to complete both FY1 and FY2, 48.76% ( n = 4294, CI: 47.72, 49.81%) planned to enter specialty training in the UK immediately thereafter; 21.11% ( n = 1859, CI: 20.27, 21.98%) intended to enter a non-training clinical job in the UK (commonly comprising an ‘F3’ year, including a junior clinical fellowship or clinical teaching fellowship, or in locum roles). These ‘non-training’ roles, although valuable for gaining clinical experience, are largely standalone posts which do not contribute to accreditation within medical specialties. The school with the highest proportion of responses indicating plans to enter specialty training immediately after FY2 was Edge Hill (64.29%), whereas at Cardiff only 25.62% shared this intention. Cardiff students were also most likely to plan to enter non-training clinical posts after FY2, at 29.06%. Students from the University of Buckingham were, by far, the least likely to look to pursue non-training posts (2.70%). Figure 3 a and b present the distribution of these intentions across UK medical schools.

Distribution of Post-Foundation Programme Career Intentions Among UK Medical Students by School. a illustrates the proportion of students at each UK medical school intending to enter specialty training immediately following the Foundation Programme. b presents the proportion of students planning to enter non-training clinical roles (comprising ‘F3’ year roles, junior clinical fellowships, clinical teaching fellowships, or locum positions) in the UK after FY2

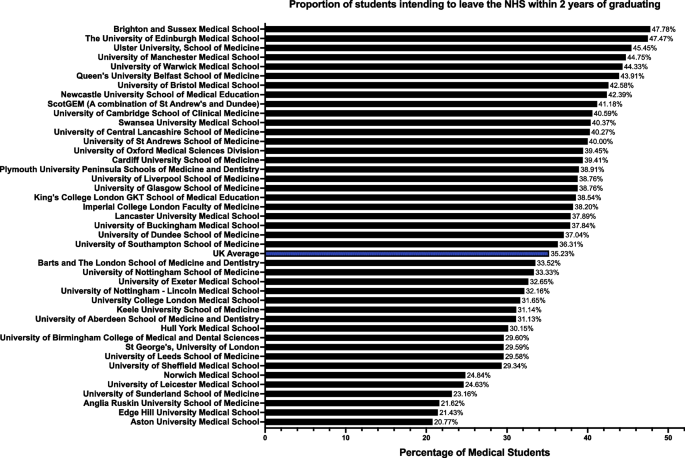

In total, 35.23% (3695/10,486) of medical students intend to leave the NHS within 2 years of graduating, either to practise abroad or leave medicine. Respondents from Brighton and Sussex Medical School expressed this intention most often (47.78%), whilst those from Aston Medical School were the least likely to do so (20.77%) (Fig. 4 ).

Proportion of UK Medical Students Intending to Leave the NHS Within 2 Years of Graduation, by School