Data Security and Privacy: Concepts, Approaches, and Research Directions

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2019

The GDPR and the research exemption: considerations on the necessary safeguards for research biobanks

- Ciara Staunton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3185-440X 1 ,

- Santa Slokenberga ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5621-8485 2 &

- Deborah Mascalzoni 3

European Journal of Human Genetics volume 27 , pages 1159–1167 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

63 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health policy

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force in May 2018. The aspiration of providing for a high level of protection to individuals’ personal data risked placing considerable constraints on scientific research, which was contrary to various research traditions across the EU. Therefore, along with the set of carefully outlined data subjects’ rights, the GDPR provides for a two-level framework to enable derogations from these rights when scientific research is concerned. First, by directly invoking provisions of the GDPR on a condition that safeguards that must include ‘technical and organisational measures’ are in place and second, through the Member State law. Although these derogations are allowed in the name of scientific research, they can simultaneously be challenging in light of the ethical requirements and well-established standards in biobanking that have been set forth in various research-related soft legal tools, international treaties and other legal instruments. In this article, we review such soft legal tools, international treaties and other legal instruments that regulate the use of health research data. We report on the results of this review, and analyse the rights contained within the GDPR and Article 89 of the GDPR vis-à-vis these instruments. These instruments were also reviewed to provide guidance on possible safeguards that should be followed when implementing any derogations. To conclude, we will offer some commentary on limits of the derogations under the GDPR and appropriate safeguards to ensure compliance with standard ethical requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Genome-wide association studies

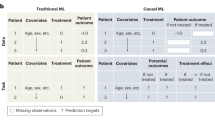

Causal machine learning for predicting treatment outcomes

Interviews in the social sciences

Introduction.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) seeks to ensure the free movement of data throughout the European Union (EU) and give expression to the right to personal data protection within and beyond the EU, as long as an EU data subject’s data or data collected in the EU are being processed. It details, the lawful basis of the processing of data (Article 6) and delineates prohibitions for processing special categories of data, such as health and genetic data (Article 9), sets out the conditions for consent (Article 7), outlines the individual rights of data subjects (Articles 13–22), and provides data subjects with a mechanism to enforce their rights (Articles 77–84).

The EU aspiration to provide a high level of protection to individuals’ personal data risked placing considerable constraints on scientific research, which was contrary to various research traditions across the EU. Therefore, along with the set of carefully outlined data subjects’ rights, the GDPR also provides for a two-level framework to enable derogations from these rights when scientific research is concerned. First, by directly invoking provisions of the GDPR on a condition that derogations be subject to safeguards that must include ‘technical and organisational measures’, and second, through the Member State law and subject to safeguards.

Although these derogations are allowed in the name of scientific research, they can simultaneously be seen as challenging in light of the ethical requirements and long-standing protection standards for participants in biobanking that have been established in various research-related soft legal tools, international treaties and other legal instruments. In relation to the use of broad consent, the GDPR itself explicitly references such standards and Recital 33 states that it is permitted to give ‘consent to certain areas of scientific research when in keeping with recognised ethical standards for scientific research’. The recognition of ethical standards is here related to broad consent and there is no explicit requirement to consider derogations in line with these ‘recognised ethical standards for scientific research’. Hence, research that could be deemed legal under the GDPR or Member State laws that permits further derogations, might not necessarily be in line with ethical standards that are currently required by research ethics committees (RECs). In other words, a gap between the ethical standard and legal requirements could emerge.

In this article, we review such soft legal tools, international treaties and other legal instruments (collectively referred to here as ‘instruments’) that regulate the use of health research data. We report on the results of this review, and analyse the rights contained within the GDPR and Article 89 of the GDPR vis-à-vis these instruments. These instruments were also reviewed to provide guidance on possible safeguards that should be followed when implementing any derogations. To conclude, we will offer some commentary on limits of the derogations under the GDPR and appropriate safeguards to ensure compliance with standard ethical requirements.

The ethical concerns related to biobanking

Ethical consideration for biobank-based biomedical research strike a balance between the societal need for scientific development and individual’s dignity and autonomy. The Taipei declaration states that ‘[r]esearch should pursue science advancement and public health development while respecting the dignity, autonomy, privacy and confidentiality of individuals’. Those rights do not include only the direct risks for individuals of being re-identified as ‘the rights to autonomy, privacy and confidentiality also entitle individuals to exercise control over the use of their personal data and biological material’.

In fact concerns about research aims may be unrelated to ‘re-identifiability’ but rather related to possible uses in research, potentially against one person’s ethical beliefs (use of health and genetic data to profile families and new generations, gender profiling, race profiling, communities discrimination, biological weapons based on genetic specificities etc.). Concerns about possible actors involved in the use of data (insurances, private companies etc.) are also major issues as an individual’s willingness to participate in research is often based on trust in specific institutions.

Biobank research is based on long-term organised collections of data and samples that can potentially be used for very diverse research aims. At the time of the collection it is unlikely that the researcher can carefully and truly inform participants on all possible future research uses, but it is possible to provide good information on the governance of data. Recent instruments show that consent (previously the main legal basis in which to lawfully conduct research) has been in fact paired with strong governance measures and third party oversight mechanisms to be adopted by institutions to regulate sharing, accessing and use of the data. Making public governance procedures on decision making is part of the trustworthiness of an institution and has ‘replaced’ in some cases specific consent as a hardly implementable option [ 1 , 2 ]. Strong governance and ethical oversight has been proposed to support the oversight of waivers of consent in the biobank practice [ 3 ] along with forms of ongoing dynamic options [ 4 ]. Detailed governance information comprising oversight policies are usually available to participants at the time of consent.

Processing of data including secondary uses is a very sensitive area in research, not only from a legal point of view but also from an ethical one. Those concerns lead to a great emphasis on principles of transparency, trust and partnership and to the development of models for ongoing information and dynamic consent accounting for changing landscapes of uses including secondary findings [ 5 ].

The GDPR provisions on research are built on exceptions and national derogations to a law that otherwise is committed to paying great attention to human rights. However, it is unclear whether those provisions are balanced by appropriate safeguards or if they are challenging recent advancement in ethics, leading one to question whether a project that is legally compliant under the GDPR is in fact ethically compliant.

The ethical rip-off: GDPR perspectives on data subject and biobanking

Lawful processing of data under the gdpr.

Article 6 GDPR sets forth legality requirements, but these requirements must be viewed jointly with the special protection afforded to special categories of data, including health and genetic data under Article 9 GDPR. Generally for biobanking purposes, the following three lawfulness basis are of particular relevance. First, the data subject’s consent under Article 6 (1)(a). Second, the performance of a task carried out in the public interest under Article 6(1)(e). Third, processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party under Article 6(1)(f), except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject, which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child.

A distinction can be drawn between primary research and secondary biomedical research based on data and samples. While lawful basis of primary research could be consent based, which might not necessarily be so for secondary use of personal data or research using residual biological material. In the latter cases, the claim of legitimate interest is of particular importance. When data are not processed based on the individual’s consent, the requirements set in Article 6(4) shall be met, which includes the existence of appropriate safeguards.

Article 9(1) prohibits the processing of special information that includes genetic information, but Article 9(2)(j) allows for processing the genetic data as part of a special category of data if ‘processing is necessary for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes.’ Furthermore, additional measures could be taken under Article 9(4) GDPR, through which Article 9(2) GDPR scope may be implicitly expanded allowing further conditions for processing health and genetic data, or constraining it. When applying Article 9(2)(j), this processing must be ‘in accordance with Article 89(1) based on Union or Member State law, which shall be proportionate to the aim pursued, respect the essence of the right to data protection and provide for suitable and specific measures to safeguard the fundamental rights and the interests of the data subject.’ In other words, for example, a Member State may attribute particular value to biobank research; they may limit a data subjects right to control the use of their data in research by removing the consent requirement for the processing of genetic data in biobanking, provided the national law respects the principle of proportionality, the essence of the right of data protection, and provides for suitable and specific measures to safeguard the rights and interests of data subjects. Yet, as further below is discussed, the GDPR is not very informative on these measures.

Individual rights and research-related derogations under GDPR

The GDPR provides data subjects with a number of rights. In biobanking, the following are of key importance: right to information (in particular, Art. 12–14), access rights (Art. 15), right to rectification (Art. 16), right to erasure (Art. 17), right to restriction of processing (Art. 18), right to data portability (Art. 20), right to object (Art. 21). Additional protective measures include, for example, a notification entitlement, providing the data subject has triggered it (Art. 19). Further to these rights and protection measures, at the data subject’s disposal is access to justice, including remedies, liability and penalties (Art. 77–84). However, this set of rights does not seem to be at the data subject’s disposal in all cases in biobank research. The exact set of rights at the data subject’s disposal depends on several circumstances, key being whether the Member State has derogated from the GDPR provisions under Article 89.2 GDPR, and/or the biobank relies on derogations through directly invoking the GDPR provisions under Article 89(1) GDPR and subsequent provisions throughout the GDPR.

Article 89(1) GDPR enables processing of genetic data for scientific research purposes, if there are appropriate safeguards for the rights and freedoms of the data subject. While the GDPR does not exhaustively specify what those safeguards are, it indicates their purpose is to ‘ensure that technical and organisational measures are in place in particular in order to ensure respect for the principle of data minimisation.’ These measures may include pseudonymisation provided it enables meeting the intended research purposes. In situations where data are not collected directly from the subject (e.g., residual material use), data subject’s right to information under Article 14 could be derogated from. Other rights that can be derogated from include the right to erasure under Article 17, as well as the right to object under Article 21.

In addition to these rights, EU or Member State law may provide for derogations from a set of other rights, provided that appropriate safeguards for the rights and freedoms of the data subject are in place. These derogations relate to the data subject’s access rights (Art. 15), right to rectification (Art. 16), right to restriction of processing (Art. 18), as well as right to object (Art. 21), and as specified in Article 89(2) GDPR, they can be applied if the derogations are necessary for research purposes.

While the data subject could remain with the data portability rights and additional protective measures, namely, the notification entitlement, these measures have a rather limited scope. First, the notification entitlement is closely related to information. If the data subject’s right to information is waived, the notification entitlement under Article 19 could be affected. Data portability, however, has a rather limited scope and it is inapplicable if biobank research relates to the performance of a task carried out in the public interest, as stated in Article 20 [ 6 ].

The potential scope of the research exemptions by directly invoking the GDPR and through the Member State laws that enables further derogations is so wide that, if applied to its full extent, not only is a data subject’s consent not necessary for the processing of personal data for research, but also the data subject can be stripped from a number of rights and others can be rendered ineffective, leaving the data subject with an enforcement mechanism only. This means, if, for example, data subjects do become aware of processing their data for biobank research, they might have no right to access information on this research or object to the research. The data subject could have no right to restrict the use of their data for research, correct any errors or request to erase the data. They would, however, be able to lodge a complaint with the data protection authority, and thus could retain some oversight [ 7 ]. However, one can then question the effectiveness of such a mechanism from a data subject’s perspective if there are no rights on the part of data subject what to oversee. The research exemption could thus undo many of the stated aims of the GDPR for research, and put at stake its own objective—the protection of privacy.

Soft legal tools, international treaties and other legal instruments (hereinafter collectively called ‘instruments’) that are influential on the regulation of health research were identified. Our review was limited to instruments that may be relevant to some or all Member States of the EU, which are either directly applicable to the Member States or to certain professions within the Member States. Our review did not include international consortia guidelines. A codebook was developed by CS and DM. All instruments were imported into Nvivo 11 and coded using thematic content analysis. A summary of the reviewed legally binding instruments can be found in Table 1 , instruments binding on particular bodies can be found in Table 2 and legally persuasive instruments can be found in Table 3 .

While the GDPR grants a number of rights to the data subjects (and simultaneously takes them away for research purposes), the focus of the other instruments is on the safeguards that must be in place for research participant data. Two exceptions are the right to information and the right to access.

Right to information

The requirements around information in the reviewed instruments is generally bound up with the consent requirements. All instruments, with the exception of the 2007 OECD Guidelines, have requirements regarding consent. It is clear from the instruments reviewed that the preference is in favour of specific, informed and written consent, where possible. Information is requested in all guidelines and should be given in plain language.

All legally binding instruments refer to the importance of informed consent, but do not necessarily set it as an obligatory pre-condition for secondary research. In addition, the GDPR introduces the possibility for electronic online consent as a viable option, provided the consent is clear and concise (Recital 32). Under the GDPR, a data subject must be informed about (among others) the identity and contact details of the data controller, the data protection officer, the purposes for which the data will be processed, the recipients of the data, the duration of storage and the right to withdraw consent if consent is the lawful basis of processing (Article 13). The 2016 Council of Europe Recommendation requires that participants be informed of the conditions applicable to the storage of the materials, including access and possible transfer policies and any relevant conditions governing the use of the materials, including re-contact and feedback (Article 10). The Council of Europe 2018 Convention mandates data subjects to be told the legal basis and the purposes of the intended processing, the categories of personal data processed, the recipients or categories of recipients of the personal data, and their rights as a data subject (Article 8).

Eminent guidance comes from the World Medical Association (WMA), historically among the first institutions to convey ethical rules for research. Its instruments sets professional standards for doctors, and are of importance in the regulation of health research globally. The Declaration of Helsinki requires that participants be informed of the aims of the research, methods, sources of funding, any possible conflict of interests, benefits and risks, institutional affiliations of the researchers and any other relevant information (Principle 26). The WMA Taipei Declaration seeks to regulate health databases and biobanks and provides more details on the requirements for consent: participants have to be informed about the purpose, the risks and burdens, storage and use of data and material, the nature of the data or material to be collected, the procedures for return of results including incidental findings, the rules of access to the health database or biobank, the protection of privacy, the governance arrangements, procedures to inform participants about the impact of anonymisation of data, their fundamental rights and safeguards as established in the Declaration, and when applicable, commercial use and benefit sharing, intellectual property issues and the transfer of data or material to other institutions or third countries (Article 12).

Allied with this extensive right to information, are the provisions on the right to withdraw consent and the obligation to inform data subjects about this right. Article 7(3) of the GDPR states that data subjects can withdraw their consent at any time and that it ‘shall be as easy to withdraw as to give consent’. The UNESCO Declaration on Bioethics (Article 6(1)), the Taipei Declaration (Article 15) and the 2017 OECD Recommendation (Article 5(2)) states that there must be procedures in place to accommodate withdrawal of consent. CIOMS states that participants need to be informed of their right to withdraw their consent, procedures need to be put in place, any withdrawal should be formalised and written, and future use of data are not permitted after this withdrawal.

Most instruments do recognise the limits on the withdrawal of consent. The 2009 OECD Guideline states that at the time of consent participants must be informed about the limits of a withdrawal of consent (Principle 4.G) as does the 2016 Council of Europe Recommendation (Article 13). Specifically, this can only be done for identified genetic data (UNESCO Declaration on Genetic Data, 2016 CoE Recommendation). It is not clear whether these limitations go beyond the practical limitation of the non-removal of anonymous data. Withdrawal of consent is thus seen of importance in both legally binding and other instruments where the legal processing of data are based on consent, but the limits on this withdrawal is recognised. Instruments that are of persuasive value state that the limits on the withdrawal of consent should be communicated to the participants.

Right to access

The GDPR, the Council of Europe 2018 Recommendation, the Taipei Declaration, the Oviedo Convention, the UNESCO Declaration on Genetic Data and the Council of Europe Recommendation all discuss the right of an individual to access their data, but there subtle differences. Under the GDPR, the data subject has the right to access information about their personal data including confirmation as to whether a data controller is processing their personal data and the purpose, other recipients of their personal data including to third countries (and the safeguards in place), where the data controller obtained the data when the data were not collected from the data subject, and expected storage period or the criteria to determine the storage period (Article 15). Article 15(3) also gives the data subject the right to access a copy of their personal data that is being processed. The Oviedo Convention states that individuals are ‘entitled to know any information collected about his or her health’ (Article 10(2)).

The WMA Taipei Declaration provides that individuals have the right to request and be provided with information about their data and requires health databases to adopt measures so that they can inform individuals about their activities (Article 14).

The 2017 OECD Guideline states that individuals must be provided with ‘information about the processing of their personal health data, including possible lawful access by third parties, the underlying objectives behind the processing, the benefits of the processing’. The Council of Europe also specifies that the management and use of the data should be made available to ‘persons’ concerned’, but this refers to the data collection in general and not the individual data (Article 6(7)). The 2006 UNESCO Declaration states that no one should be denied access to their data ‘unless domestic law limits such access in the interest of public health, public order or national security’ (Article 13).

There are limitations on this right to access. The GDPR states that the right to access does not apply when the data are anonymous and the right to access does fall within one of the possible national derogations under Article 89(2). The Oviedo Convention simply states that the right to access may be restricted in ‘exceptional’ cases with no further elaboration. The UNESCO Declaration on Genetic Data also states that the right to access does not apply when the data are anonymous and that the right to access can be limited by law in ‘the interest of public health, public order or national security’ (Article 13).

Some instruments also touch on feedback to participants as distinct from access to data. Generally, where it is discussed, a policy on feedback is required, but not necessarily that feedback must take place. Discussion on feedback of findings is confined to the non-binding instruments. The 2009 OCED Guidelines discusses ‘feedback’ to participants. It does not mandate that there is feedback to participants, only that there is a policy in place (Principle 4.9) and the results that can be feedback (Principle 4.14). The annotations to the Guideline do state that participants should be provided with information about the type of research that may be carried out on the data, whether it will be used for commercial research and if it will be transferred abroad. The 2016 CoE Recommendation similarly states that there must be a policy in place on feedback of findings and the importance of counselling (Article 17).

Right to rectification and right to erasure

The GDPR is alone in discussing the right to rectification and the right to erasure. None of the other instruments reviewed discussed these rights. The right to erasure may be linked to a right to withdraw from research as the withdrawal from any study may include the erasure of a participants’ data, but any recognised right to erasure would go further than a right to withdrawal. The right to withdrawal is arguably limited to ongoing and future research, whereas a right to erasure would include the removal from future, ongoing and past research, including potentially published research.

The right to data portability and the right to object

Article 20 of the GDPR gives data subjects the right to move their data from one data controller to another. The 2017 OECD Recommendation is the only other regulation reviewed that provides that data subjects should be permitted to request the sharing of their data for health-related purposes, and if this is rejected, they must be provided with a legal basis for that decision (Section 5(ii)(a) and (b)).

Article 21 of the GDPR provides data subjects with the right to object to the processing of their personal data, including for research purposes. Once again, the 2017 OECD Recommendation is the only regulation reviewed that states that where consent is not the lawful basis of processing, individuals should be able to object to the processing of their personal information. If this cannot be honoured, they should be provided with a relevant legal basis for the decision (Section 5(ii) (a) and (b)).

Safeguards to protect data subjects

Article 89(1) of the GDPR states that safeguards ‘shall ensure that technical and organisational measures are in place in particular in order to ensure respect for the principle of data minimisation’. These measures ‘may include pseudonymisation’, but offer no further insight into what they may also be.

Looking at the instruments reviewed, the importance of clear governance procedures (and by implication, transparency) is essential in the oversight of the use and re-use of data. This is of particular importance when the data subject has not provided specific consent to the use of the data. This may be in a manner prescribed by law, a requirement of institutional oversight that may include approval by an ethics committee or some other body, requirement of safeguards, or a combination. As outlined in Table 4 , there are three levels of oversight or protections discussed in the instruments: a legislative framework, institutional oversight that includes independent ethical review and provides for other safeguards.

The instruments reviewed have a different aim than the GDPR [ 8 ], are specifically developed for research and they do provide additional guidance that should be followed to ensure that biobanks meet standard ethical practice. First, although the derogations under the GDPR are potentially quite wide ranging, the instruments reviewed put some limits on these derogations, specifically in relation to the right to information and the right to access. Regarding the right to information, data subjects should be informed about re-contact, feedback, storage, and withdrawal of consent and any possible limits. Similarly, the instruments reviewed do strongly suggest that data subjects should be able to access their personal data, but a distinction is drawn between access of data and feedback of findings/results. The instruments do not mandate feedback of findings, but rather state that a policy should be in place. Whether there is in practice any real distinction between access of genetic data and feedback of findings, it is clear that at a minimum, biobanks should have a policy on feedback of findings in place stating whether or not this is foreseen.

Second, the instruments do provide guidance on possible safeguards. Article 89(1) and Article 89(2) speaks of the importance of the rights and freedoms of the data subject’ and this should be considered when invoking the research exemption. However, there is little guidance within the GDPR itself on striking the balance between research and individual rights. The words ‘in particular’ and ‘may include’ in Article 89(1) of the GDPR indicates that the safeguards include but are not confined to technical and organisational measures and pseudonymisation. The Article 29 WP (now the European Data Protection Board) states that safeguards could include ‘Information Security Management Systems (e.g., ISO/IEC standards) based on the analysis of information resources and underlying threats, measures for cryptographic protection during storage and transfer of sensitive data, requirements for authentication and authorisation, physical and logical access to data, access logging and others’ [ 9 ]. However, data protection is much more than a technical issue requiring technical solutions and the Article 29 WP has also spoken of the need for ‘additional legal, organisational and technical safeguards’ [ 9 ]. The safeguards must respond to the multitude of legal, ethical and social risks that are associated with the sharing of data. These risks are not static and change over time. Thus, any safeguards must be dynamic and responsive to an evolving science. In determining the safeguards that should be adopted, this review makes it clear that any derogations are subject to two pertinent factors.

First the importance of clear and transparent policies on a multitude of issues is evident. These policies may include policies on data transfer, feedback of findings, storage of data, withdrawal of consent, re-contact of data subjects, access requests from third parties, access requests of data subjects, governance, and (where applicable) intellectual property and commercial use. It is essential that biobanks have these policies in place and that they are publicly available. Having these policies available at the outset is also in line with the GDPR’s policy of privacy by design and default.

Second, it is evident that clear and transparent governance procedures that oversee the use of data are essential in protecting the rights of the data subject. Once again this is in line with the GDPR and the importance of transparency. A coherent and robust governance structure is key in fostering trust and trustworthiness that is so important in biobanking [ 10 ]. What emerges from the instruments reviewed is that there are broadly three levels to a governance structure that Member States should follow: a national legal and ethical framework; independent and interdisciplinary review and oversight of the research; and local policies on data sharing and protection.

At a minimum, national legislation should provide for the legal basis of processing of personal data for research purposes. The legislation should also mandate for local, independent approval and oversight prior to the use of data in research. Generally this will be in the form of institutional research ethics review. However, while each research project that seeks to collect and use personal data are currently subject to independent ethics review, the subsequent use and access of this data may not, with no body ensuring that the rights of data subjects are protected. Controlling access to the subsequent use of data are essential to ensure that there are no undue risks to the participant, and this review points to the importance of independent review of access requests for data. An independent body is best placed and likely to have the necessary expertise to consider the potential heterogeneous risks of an access request and these risks should not outweigh the benefits [ 11 ].

Third, each biobank must have transparent policies in place regarding the use of personal data. They should include but are not limited to policies on access, information, use and re-use of data, transfer to third parties and feedback of findings. These policies must be made publically available and submitted to a local ethics committee as part of the research protocol.

Finally, members of an ethics committee may be faced with a situation whereby a study under review meets the requirements and derogations under the GDPR, but have ethical concerns about the research. A resolution to this gap between the law and ethics may in part depended on the national legal order that is in place, but the purpose of such committees is to ensure the ethical conduct of research. The law is a minimal standard to which researchers must comply with and the Article 29 Working Party Guidelines on consent state that (where consent is the legal basis for processing) ‘consent for the use of personal data should be distinguished from other consent requirements that serve as an ethical standard or procedural obligation’ [ 12 ]. Ethics committees are not necessarily under the obligation to approve research that meets this legal threshold, but fails to meet ethical criteria.

The GDPR provides for derogations on certain individual rights for research on two separate grounds, but they must be subject to safeguards and provided for by Member State law. There is little insight or guidance contained within the GDPR as to the appropriate safeguards that must be in place, which is alarming considering the potential scope of the derogations. This review makes it clear that a full implementation of the derogations as provided for under the GDPR may render the research unethical and not in line with individuals interests. These instruments also suggest that clear governance procedures and policies on the use and re-use of personal data can go some way towards ensuring that there are necessary safeguards in place to ensure the protection of personal data. This would also ensure that any derogations continue to be in line with the GDPR’s transparency requirements and privacy by design and default. By following these necessary safeguards, biobanks can ensure that they may continue to conduct research, which ensuring the protection of personal data. In this way, research will not trump data protection, but there will be a balance of the (at times) two competing interests [ 13 ].

Mascalzoni D, Dove ES, Rubinstein Y, Dawkins H, Kole A, McCormack P, et al. International Charter of principles for sharing bio-specimens and data. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:721–8.

Article Google Scholar

Boers S, van Delden J, Bredenoord A. Broad consent is consent for governance. Am J Bioethics. 2015;15:53–5.

Gainotti S, Turner C, Woods S, Kole A, McCormack P, Lochmuller H, et al. Improving the informed consent process in international collaborative rare disease research: effective consent for effective research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1248–54.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kaye J, Whitley EA, Lund D, Morrison M, Teare H, Melham K. Dynamic consent: a patient interface for twenty-first century research networks. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:141–6.

Budin-Ljøsne I, Teare H, Kaye J, Beck S, Beate Bentzen H, Caenazzo, et al. Dynamic consent: a potential solution to some of the challenges of modern biomedical research. BMC Medical Ethics. 2017;18:4.

Chassang G, Southerington T, Tzortzatou O, Boeckhout M, Slokenberga S. Data portability in health research and biobanking : legal benchmarks for appropriate implementation. Eur Data Protection Law Rev. 2018;3:296–307.

Slokenberga S, Reichel J, Niringiye R, Croxton T, Swanepoel C, Okal J. EU data transfer rules and African legal realities: is data exchange for biobank research realistic? Int Data Privacy Law. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipy010.

Slokenberga S. Biobanking between the EU and third countries — can data sharing be facilitated via soft regulatory tools? Eur J Health Law. 2018;25:517–36. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718093-12550397

Article 29 Data Protection Working Party. Advice paper on special categories of data (“sensitive data”). Ares (2011) 444105.

Whitley EA, Kanellopoulou N, Kaye J. Consent and research governance in Biobanks: evidence from focus-groups with medical researchers. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15:232–42.

Shabani M, Borry P. Rules for processing genetic data for research purposes in view of the new EU General Data Protection Regulation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:149–56.

Article 29 Data Protection Working Party. Guidelines on consent underRegulation 2016/679. WP259 rev.01.

Mascalzoni D, Beate Bentzen H, Budin-Ljøsne I, Bygrave LA, Bell J, Dove ES, et al. Are requirements to deposit data in research repositories compatible with the European Union’s general data protection regulation? Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:332–4.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Innovation, Research and University of the Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano for covering the Open Access publication costs.

CS declares no financial support for this work. SS declares financial support by Stakeholder-informed ethics for new technologies with high socio-economic and human rights impact (SIENNA) H2020 project, grant agreement no. 741716. DM declares financial support by RD-Connect.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Law, Middlesex University, London and Centre for Biomedicine, EURAC, Bolzano, Italy

- Ciara Staunton

Faculty of Law, Lund University and Center for Research Ethics and Bioethics Uppsala University Sweden, Uppsala, Sweden

- Santa Slokenberga

Centre for Biomedicine, EURAC, Bolzano and CRB Uppsala University Sweden, Uppsala, Sweden

Deborah Mascalzoni

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ciara Staunton .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Staunton, C., Slokenberga, S. & Mascalzoni, D. The GDPR and the research exemption: considerations on the necessary safeguards for research biobanks. Eur J Hum Genet 27 , 1159–1167 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0386-5

Download citation

Received : 18 July 2018

Revised : 05 March 2019

Accepted : 07 March 2019

Published : 17 April 2019

Issue Date : August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0386-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Specific measures for data-intensive health research without consent: a systematic review of soft law instruments and academic literature.

- Julie-Anne R. Smit

- Menno Mostert

- Johannes J. M. van Delden

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

Ethical and social reflections on the proposed European Health Data Space

- Mahsa Shabani

GBA/GBN-position on the feedback of incidental findings in biobank-based research: consensus-based workflow for hospital-based biobanks

- Joerg Geiger

- Joerg Fuchs

- Roland Jahns

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

Embedding artificial intelligence in society: looking beyond the EU AI master plan using the culture cycle

- Simone Borsci

- Ville V. Lehtola

- Raul Zurita-Milla

AI & SOCIETY (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2021

Research under the GDPR – a level playing field for public and private sector research?

- Paul Quinn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6243-765X 1

Life Sciences, Society and Policy volume 17 , Article number: 4 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8597 Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scientific research is indispensable inter alia in order to treat harmful diseases, address societal challenges and foster economic innovation. Such research is not the domain of a single type of organization but can be conducted by a range of different entities in both the public and private sectors. Given that the use of personal data may be indispensable for many forms of research, the data protection framework will play an important role in determining not only what types of research may occur but also which types of actors may carry it out. This article looks at the role the EU’s General Data Regulation plays in determining which types of actors can conduct research with personal data. In doing so it focuses on the various legal bases that are available and attempts to discern whether the GDPR can be said to favour research in either the public or private domains. As this article explains, the picture is nuanced, with either type of research actor enjoying advantages and disadvantages in specific contexts.

1. Introduction

Research is without doubt of elemental importance to the wellbeing and advancement of any society (Mirowski and Sent 2002 ). It contributes to scientific knowledge, economic growth and can be used to address serious societal problems. Whilst the traditional image of research is that of a university research group or university hospital, the reality is that research has always and will always be conducted by a variety of actors. A large range of private entities, varying from small organisations to large and powerful tech and social media giants are continuously engaged in research. Whilst the motives of such research may often be more commercial in nature, it is nonetheless indispensable for innovation and economic growth.

The use of data is central to all forms of research. This often includes personal data. The ability of researchers to access personal data, is often a key factor in determining whether various forms of research are able to proceed (Heffetz and Ligett 2014 ). Regulatory frameworks, including data protection frameworks therefore play an important role in many instances in determining not only what forms of research may be conducted, but also what types of researchers are able to carry them out (Dalle Molle Araujo Dias 2017 ). This article looks at the importance of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in determining what types of research can be performed with personal data. In particular it focuses on the legal bases that exist within the GDPR that can be used for such purposes. As this paper discusses, the GDPR is, in general, friendly to research and presents a number of different options in terms of legal bases (informed consent being only one) that can be used in various contexts. This article aims to demonstrate which legal bases may be of most use to various types of research actor and aims in particular to contrast the position of researchers based in public sector institutions like universities with others working in the private sector e.g. for large commercial entities.

Section 2 of this article outlines the importance of personal data and consequently data protection frameworks for research. As section 3 discusses, this importance is only likely to increase given the increasingly data hungry nature of modern research, depending on inter alia access to forms of big data (Akoka et al. 2017 ). Sections 4 and 5 outline the research friendly nature of the GDPR and the various options it presents for those wishing to conduct research with personal data. These legal bases may be more appropriate for use in certain contexts and by certain types of actors than others. Whilst as sections 6 and 7 discuss, certain legal bases (e.g. allowing for research that is in the ‘public interest’ or for ‘scientific research’) may be in theory open to both public and private actors alike, the de facto reality surrounding their use means that private sector entities may find it more difficult to use them. This can be compared to the possibility to process personal data for ‘legitimate interests’. This can allow research in a number of important contexts but is in general only available to private entities and can not be used by public institutions. A further important possibility is the seemingly very broad option to further process any personal data a data controller may be in possession of for purposes of scientific research so long as it had a valid legal base for the possession of the data in the first place.

As this paper discusses, it is also important to consider the de facto context of various types of research entities. Large commercial entities (e.g. tech giants, social media platforms, or eCommerce vendors) may possess enormous pools of big data they have generated in relation to their clients. This may provide a significant practical advantage in certain conexts over researchers in public institutions. University researchers may by contrast often be dependent upon agreements with external parties to obtain research data. As sections 6 &7 discuss, these variations mean that the opportunities the GDPR provides for research are nuanced and may in reality not be equally available to all types of research actors. The answer to the question of whether there is a level playing field for research actors based in public and private research contexts is therefore complex, with neither enjoying a definitive advantage.

2. The use of personal data is becoming more common and complex in the age of big data

The importance of data protection frameworks to research has increased greatly in recent times. This is because more and more research is conducted using personal data and also because data protection frameworks have become more complex and far reaching. These changes are linked to the increasing ability to digitize more and more personal data and to share it in a world of ever increasing interconnectivity (Meszatos and Ho 2018 ). In the medical field for example patient dossiers are now routinely stored as Electronic Health Records (EHRs). Such data now forms a rich source of research data for a variety of researchers interested in investigating medical issues (Jensen et al. 2012 ). EHRs are but one example however. A wealth of diverse sources of data have emerged that can be of use for research (Connelly et al. 2016 ). These can vary from social media activity, phone tracking and efforts at citizen science (where individuals collect their own data for research purposes) (Corrales et al. 2017 ; Quinn 2018 ). Footnote 1 The ability to collect and combine any of these forms of ‘big data’ mean that researchers have a wealth of data to analyze for various research purposes. At the same time, computing power has been increasing enormously, meaning that the various analytical processes that can be applied to such data has increased greatly. This has led to an explosion of research that is solely data (or computational) based (Quinn and Quinn 2018 ). Footnote 2 Such research often does not depend on physically measuring or making impositions on individuals or objects, but rather makes use of pre-existing data. The use of such large forms of secondary data may have considerable advantages, including the analytic power that such large datasets often bring and also potentially the ability to avoid problems surrounding the primary collection of data, e.g. administrational, practical, ethical etc. Whilst this world of readily available big data might facilitate research in many ways it also brings more research within the purview of data protection. This is primarily for two reasons:

More personal data that ever before is now available.

In a digitized world individuals are able to upload and store data (on a permanent basis) to an extent that was not possible in the past. This ranges from official and important sources such as EHRs to apparently innocuous efforts at self-quantification (Swan 2013 ). It may include data taken from mobile phones (that can be linked to them) or relate to the information they post to social media. In other instances, it could come from a long history of online purchases. The continued creation, storage and ability to share such data means provides a rich source of material for researchers. The ability of researchers to access such data may vary depending on the type of entity they are and the context of the research in question (further discussed in section 6).

Many forms of big data may contain personal data (even where not immediately obvious).

In the big data world it may not always be intuitively obvious whether large data sets contain personal data within them. It may only become obvious after careful and considered inspection of the data in question. Such data may often be large, heterogeneous and unstructured. This means that it may contain personal data in ways that are not immediately obvious (Mai 2016 ). Discerning whether data is of a personal nature or not is of immense importance. The GDPR confirms that where data is anonymous it is not of application. Footnote 3 This means that researchers processing truly anonymous data do not have to concern themselves with the requirements of the GDPR (Quinn 2017 ). Footnote 4 By contrast however, where data in question is personal, the GDPR is of full application (no matter how pseudonymous or encrypted the data in question maybe). Footnote 5 Given that the bar for anonymization has been seemingly set very high, it is important not to rule out that any dataset may contain personal data even where this is not intuitively obvious. Footnote 6 This is especially true with large data sets. This is because it may be possible to combine various elements within a large data set or with data that is readily available elsewhere in order to arrive at conclusions about potentially identifiable individuals. Advances in computing power and in analytic software only increases such a possibility. Given that data is only going to become ‘bigger’, that computing power is only going to increase and that the availability of complimentary data is only going to grow, the likelihood of any large data set containing personal data is likely to increase. This factor means that it is becoming increasingly difficult to render datasets anonymous whilst allowing them to retain any useful value (e.g. for AI analysis).

3. The implications of data protection for research

A. personal data and harms.

Researchers and societies in general have long been aware of the potential for physical harms to be produced from experimentation in humans (Freidenfelds and Brandt 1996 ; Rothstein 2010 ; Drabiak 2017 ). In recent decades, and with scientific research becoming both more complex in its use of data (including data relating to human beings) an increasing awareness has been developing of harms that can be produced from the use of information in research. This has led to the creation of various strategies and approaches that have been formulated to regulate the use of personal data inter alia in research. Some of these may apply specifically to researchers whilst others may apply to other domains from which researchers may draw their data. Confidentiality laws may for instance limit the ability of researchers to obtain personal data (e.g. from medical professionals) (Berman 2002 ). Other approaches such as ethical or deontological codes may attempt to restrict what researchers can do with data in terms of research (discussed further in section 6) (Tene and Polonetsky 2016 ). Whilst such codes may not always be considered as law, they have had and continue to have an important role in regulating the use of data in research (see section 6).

In recent decades however and particularly within Europe, data protection frameworks have come to be seen as the most important form of regulation relating to the use of personal data. They are both general and of far reaching application, applying in most contexts where personal data is used, including for the purposes of research. Starting with Directive 95/46/EC Footnote 7 and more recently the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Footnote 8 the European Union has effectively crafted a (mostly) harmonized regime across Europe regulating the use of personal data. Footnote 9 Data protection has arguably risen from a position of relative obscurity, to become the central regulatory framework concerning the use of personal data in research. In doing so it has arguably come to overshadow older legal regimes (e.g. related to confidentiality) that may apply. The GDPR, being the legislative initiative that is both the most harmonizing and of the most general application, is of particular importance to researchers active across numerous domains (Quinn and Quinn 2018 ; Peloquin et al. 2020 ). Footnote 10 In terms of its general application, it does not apply to specific contexts, but rather to most instances where personal data is being processed (including but thus not limited to research). If the GDPR is of application personal data can only be processed if certain conditionality is met. Footnote 11 Some of the most prominent forms of conditionality relate to:

Data protection principles

The GDPR foresees a number of important principles which controllers must adhere to when processing personal data. They are of general application and usually apply whatever the legal base is for the processing of question. The principles themselves are somewhat abstract and the application to a particular context will require reflection on the part of the data controller (Mondshein and Cosimo 2019 ). Data minimization for example obliges data controllers to collect no more personal data than they need for the processing operation that is envisaged. The storage limitation principle requires controllers to delete data once they are no longer needed for the purposes that were originally envisaged. Other principles require data controllers to ensure that their processing operations are secure, transparent and that privacy and data protection are taken into account at all stages of processing and planning (Forgo 2017 ). One important principle which the GDPR allows to be applied differently in instances of scientific research is that of purpose limitation. In particular, the GDPR allows researchers more room in terms of the description of the purpose of processing they must present to the data subject. This can be used to allow a broader form of consent for the use of personal data in scientific research than may be possible for other forms of processing. Footnote 12

Data subject rights

Data controllers must facilitate a number of important data subject rights, including in research contexts. Footnote 13 These rights may, depending on the context in question, be onerous to facilitate and may entail the creation of various administrative structures. This can be costly and time consuming for researchers. Notable data subject rights include a right of ‘erasure’ (commonly known as ‘the right to be forgotten’), a right ‘to object to processing’, a right of ‘data portability’. In forms of research that require complicated forms of big data facilitation of such rights may be complex and are once again likely to require careful consideration of the context in question. One important consideration for researchers is that the legal base selected for the processing of personal data in research may determine the extent to which data subject rights apply given the ability the GDPR allows Member States to limit them in instances of scientific research (discussed further in section 4.b).

Administrative requirements

The GDPR foresees a number of important administrative requirements that are likely to apply to researchers, particularly when they use sensitive data. This includes the need to appoint a Data Protection Officer and potentially the need to perform a data protection impact assessment (Quinn and Quinn 2018 ). In addition to the requirements outlined in the GDPR, Member states may add further requirements, in particular for the processing of sensitive forms of data. Footnote 14

The need for a legal base

The above requirements will apply to most forms of processing. Before processing of personal data can be contemplated however, it is necessary to ensure that there is a legal base for processing. Footnote 15 A legal base represents a set of conditions or a context in which the processing of certain form of personal data are permitted. Without an applicable legal base researchers can not process personal data for research or any other reason. One of the most well known is that of ‘informed consent’. Footnote 16 As sections 4 and 5 describes this forms the legal base for many forms of research. The GDPR, like its predecessor, also foresees a range legal bases that do not require consent. Some of these will permit research in circumstances where obtaining consent from data subjects is not desirable or even possible. Each of these bases will be outlined and presented further in sections 4 and 5.

Researchers conducting research with personal data must take into account all of the elements outlined in (i)-(iv) above. Whilst each represents an important factor that should not be understated, a full analysis of them is beyond the scope of this paper. The remaining focus will be on (iv), i.e. the need for a valid legal base. A considered examination of this requirement is interesting from the perspective of this paper because the various legal bases that exist within the GDPR may not be equally available to all types of research entities. Subsequent sections of this paper will analysis this in the context of modern research in order to highlight the existence and consequent importance of such differences.

4. The GDPR provides a wealth of legal bases for researchers

A. several bases are available to varying types of actor.

The increasing engagement of research by data protection frameworks such as the GDPR discussed in section 3 means that the GDPR will consequently become more determinative of what forms of research are permitted and how they should be conducted. Whilst the GDPR was not created solely for the purposes of research, it was clearly a significant form of processing that was envisaged by the those responsible for creating it (Nyren et al. 2014 ). Footnote 17 Importantly, it does not attempt to shoehorn all forms of scientific research into one single legal context but rather appears to recognize that scientific research, and the various motivations behind it, are extremely heterogenous. A ‘one size fits all’ notion of scientific research does not exist. Research varies in terms of its goal (‘blue skies’, ‘not for profit’, ‘commercial’ etc.), the identity of the those carrying it out (universities, hospitals, large commercial actors) and the various data subjects involved (varying from vulnerable individuals to well informed consumers) (Shmueli and Greene 2018 ). The regulation accordingly foresees several legal bases that can be utilized by individuals or entities wising to conduct research. This seeming assortment of options is important given the diverse nature of scientific research. As recital 159 of the GDPR states:

“For the purposes of this Regulation, the processing of personal data for scientific research purposes should be interpreted in a broad manner including for example technological development and demonstration, fundamental research, applied research and privately funded research”

This points to a very open mind in terms of what the drafters of the GDPR regarded as ‘research’, with a concept that does not discriminate between research of varying types (e.g. public, private or commercially motivated). Various research activities may also be permitted under grounds that are not specifically related to research. The GDPR is accordingly not lacking in terms of potential legal bases that may be available to researchers in various contexts. On the contrary, it can almost be considered to contain an ‘embarrassment of riches’ in terms of potential legal bases that can be used for research involving personal data. The most prominent are described below (legal bases or sensitive data are discussed in section 5).

The use of consent

Consent is perhaps the most well known legal base for justifying data processing in general. It can be used to justify the processing of personal data in an almost undefinable range of circumstances where data subjects have provided their consent. This includes a wide spectrum of research contexts in both the public and private sector. The GDPR demands that such consent must represent a clear and unambiguous indication of a data subject’s wishes and that it must be informed. It is defined in the GDPR as. Footnote 18

“any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject's wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her”

Consent therefore can not be passive and individuals must receive a minimum of information in order to be able to provide their consent. In this regard, article 13 of the GDPR specifies a number of elements that must be explained to data subjects including, the purposes of the processing in question, the identity of the data controller and how long data will be kept for (Staunton et al. 2019 ). Footnote 19

Importantly the GDPR arguably foresees a slightly looser from of consent for scientific research than is available elsewhere. This is outlined by recital 33 which states that the purpose of processing can be described in less concrete terms for instances of scientific research. This may allow researchers some room where the nature of their research makes this difficult e.g. using AI or other computational processes with various forms of big data. This extra room should not be interpreted as a carte blanche for researchers. The purposes of research must nonetheless be described to a sufficient level. Footnote 20 Where this is not possible consent should not be used as a legal base for processing.

Although these conditions may not seem onerous, complying with them can produce considerable difficulties for researchers. Contacting (and even identifying) all potential data subjects may for example difficult, especially where research involved very large data sets. This may entail the use of complex administrative processes and consequentially further costs (Jamrozik 2004 ). Even where it is possible it may introduce an element of bias, where individuals who refuse consent may represent a statistically important group (Rothstein and Shoben n.d. ). For these reasons, the use of consent may not be practical in all instances where research is to be carried out.

Reasons of public interest

In many instances it may not be possible (or even desirable) to gain the consent of data subjects. The data subjects may be too many, too difficult to reach or the type of processing involved may be too difficult to explain. In certain contexts consent may not be ethically appropriate because of power imbalances (e.g. where the relationship between the data controller and subject makes it difficult for the latter to withhold consent) (Solove 2013 ; Corrigan 2003 ). Footnote 21 Numerous forms of research in the public interest fall into this latter category (Donnelly and McDonagh 2019 ). Footnote 22 This includes research needed to better organize public services or other forms of governance. In order to facilitate such forms processing (which are in the public interest) the GDPR foresees a particular legal base (described in article 6(e)) for processing in this context. Another important feature of this legal base that may often make it attractive to researchers is that Member States can, through legislation, limit a number of data subject rights normally incumbent upon instances of processing of personal data (discussed further below in (b)). This includes in a number of important areas relevant to research covering both a number of data protection principles (e.g. storage limitation) and data subject rights (e.g. the right to be forgotten). Footnote 23 In addition to obviating the need to obtain consent, the use of such a legal base can be highly advantageous to researchers in a number of contexts given that it may remove serious burdens upon researchers (i.e. the need to comply with strict understandings of various data processing principles or data subject rights) (Quinn and Quinn 2018 ).

Whilst being seemingly wide in terms of its scope, this legal base should not be viewed as being available for all forms of research. There are important limitations. Most importantly, it is only available where there is specific (European) Union or Member State law available (Donnelly and McDonagh 2019 ). This usually means that legislation must exist that identifies the controller in question as being able to carry out the type of processing in question. The use of this base represents one of the areas of data protection law where a considerable margin is left to the Member States to determine the specifics. As a result, there may be considerable variation in the exact nature of this base and its availability to researchers across Europe. As section 6 discusses, the legislation available in the various Member States may vary in terms of the extent it can be used by commercial forms of research. In some Member States legislation may be phrased in a manner that seemingly limits the applicability of this legal base to commercially motivated forms of research. Where such legislation does not exist, or is not applicable to a certain research context (i.e. commercially motivated research), this legal base for processing personal data will not be available. In addition, the use of this option must be necessary (and thus also proportional) in a specific context. Footnote 24 In other words it can not be simply opted for because of the innate advantages it may offer, but only when consent is clearly not appropriate.

Processing is necessary for the performance of a contract/ of a legal obligation

The GDPR recognizes forms of personal data processing are implicit to the execution of many forms of contract. Having to continually ask for consent from data subjects would be inefficient and make the goal (which both parties had contracted for difficult to achieve). Whilst one can imagine certain contexts where consumers contract with certain commercial entities to conduct research on their data, this type of relationship is not common in the public sector. Footnote 25 Similarly the GDPR recognizes that data controllers may have to comply with legal requirements in ways that involve the processing of data. This could be for instance when they are ordered by the courts to hand over certain data or when they are forced to defend themselves by legal proceedings (including where started by the data subject). Whilst such a potential ground may have societal importance, it is hard to see its potential relevance in permitting scientific research.

Legitimate interests

One legal base that is likely to be of more relevance to research is that of ‘legitimate interests’. Footnote 26 This represents an extremely broad option for non-governmental or public entities to process personal data when it is needed to do so in their interests (Donnelly and McDonagh 2019 ). Footnote 27 Where available it means that consent will not be required for processing of sensitive data (Olly 2018 ). This could for example include any number of instances where large commercial entities may wish to conduct further research on their customers’ data so that they can improve services to them, reduce the risk of criminality or other harms or improve their general commercial strategy. The concept of legitimate interests does however have some important limitations, some of which are outlined in recital 47 of the regulation. It states:

“The legitimate interests of a controller, including those of a controller to which the personal data may be disclosed, or of a third party, may provide a legal basis for processing, provided that the interests or the fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject are not overriding, taking into consideration the reasonable expectations of data subjects based on their relationship with the controller. Such legitimate interest could exist for example where there is a relevant and appropriate relationship between the data subject and the controller in situations such as where the data subject is a client or in the service of the controller. At any rate, the existence of a legitimate interest would need careful assessment including whether a data subject can reasonably expect at the time and in the context of the collection of the personal data that processing for that purpose may take place.”

The GDPR thus demonstrates that the relationship between the data controller and the data subject is central in determining how far the ground of legitimate interest can be used to justify processing of personal data inter alia for research purposes. Where the relationship is of greater proximity and transparency it will be easier for proposed research use of personal data to be foreseeable. Foreseeability (or ‘reasonable expectations’ as the GDPR describes) is crucial because it allows data subjects to exercise their data rights (e.g. the right to object or the right of erasure) in instances where they may want to stop forms of processing that are likely to be conducted under the guise of legitimate interests. Footnote 28

Conversely, when the relationship between data subject and controller is more convoluted and less transparent, it will be more difficult to argue that the research use of personal data is foreseeable in terms of the legitimate interests of the data controller. The use of legitimate interests might be more acceptable for example when a social media giant conducts research with its clients’ data in order to find ways to prevent future account hacking. Research of this type is arguably foreseeable and even to be expected by the data subject. Research by an another organization which only had a transient link with certain data subjects and for purposes that had a limited connection the original relationship might however be difficult to justify. In addition, as the EDPS pointed out in its opinion on scientific research (A Preliminary Opinion on data protection and scientific research”, European Data Protection Supervisor 2020 ), data controllers must perform a balancing exercise when discerning what is permissible in terms of their legitimate interests. This test was previously outlined by the Article 29 working party in 2014. Footnote 29 It is complex and involves balancing the legitimate interest sought by the data controller against the fundamental rights and freedoms of data subjects. This will involve taking into account the importance of the processing in question (to both the data controller and society at large) and balancing this against the interests of the data subject, including taking into account and potential privacy harms. Research that has a high value to the controller or to society in general will carry a higher weight in such a balancing exercise.

B. Informational obligations/data subject rights may vary according to the legal base used

In discerning what requirements may be attached to a particular legal base it is important to take into account the informational obligations and data subject rights that may be applicable in each instance.

Informational obligations connected to the use of differing legal bases

In terms of informational obligations, two GDPR articles are of particular importance. Article 13 outlines what information must be provided when data subjectd provide their consent for the processing in question. This includes information such as the name and contact details of the data controller, the aims of the processing and further information concerning the potential exercise of their data subjects rights. In general compliance with these requirements is not particularly difficult. This is because such information can be provided at the same time a data subject is providing consent (e.g. with a physical or electronic consent form). This is obviously not the case for the other legal bases described above where the data subject does not provide consent. In such instances article 14 comes into play, outlining certain forms of information that should be provided when consent has not been obtained from data subjects for the processing in question. Complying with article 14 in many instances of scientific research is however likely to be more problematic than may be the case for article 13. In many instances this may for the same reasons outlined above that make obtaining consent itself difficult. This may be because it may be difficult to contact all data subjects or systematically gain consent from them. Having to contact data subjects even in instances where consent is not used as the legal basis for processing would often present serious problems for researchers that opt for other bases such as public interest or legitimate interests (where such bases are indeed available). The GDPR appears to recognize that this may be a problem in inter alia research stating that the requirements of article 14 do not need to be met where Footnote 30 :

“the provision of such information proves impossible or would involve a disproportionate effort, in particular for processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes, subject to the conditions and safeguards referred to in Article 89 (1) or in so far as the obligation referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article is likely to render impossible or seriously impair the achievement of the objectives of that processing.”

This exception seemingly applies different tests to different research contexts, including the legal base that is opted for. For public interest or scientific research, the bar appears to be the creation of ‘disproportionate effort’. For other forms of processing it appears to be set higher i.e. ‘to render impossible or seriously impair’. This is important given that all of the legal bases discussed above may be used for research. Accordingly research that uses legitimate interest as a base will face a higher bar to demonstrate that they can use the exception outlined in Article 14 to not provide information to research subjects (i.e. they will need to demonstrate serious impairment or impossibility). Difficulty or high cost would not seem to be valid reasons. As Ducato states (Ducato 2020 ): Footnote 31

“This is not in any case a blanket exception and requires a balancing assessment. First of all, the “impossibility” and “disproportionate effort” must be tailored to “the number of data subjects, the age of the data and any appropriate safeguards”. Second, the EDPB has further stressed the need for the controller to evaluate “the effort involved for the data controller to provide the information to the data subject against the impact and effects on the data subject if he or she was not provided with the information”. This will consist at least of making the information publicly available (e.g. publication on website, newspapers, etc.)”