Political Instability And Uncertainty Loom Large In Nepal

By gaurab shumsher thapa.

- February 16, 2021

This article was originally published in South Asian Voices.

Nepal’s domestic politics have been undergoing a turbulent and significant shift. On December 20, 2020, at the recommendation of Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, President Bidya Devi Bhandari dissolved the House of Representatives, calling for snap elections in April and May 2021. Oli’s move was a result of a serious internal rift within the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) that threatened to depose him from power. Opposition parties and other civil society stakeholders have condemned the move as unconstitutional and several writs have been filed against the move at the Supreme Court (SC) with hearings underway. Massive protests have taken place condemning the prime minister’s move. If the SC reinstates the parliament, Oli is in course to lose the moral authority to govern and could be subject to a vote of no-confidence. If the SC validates his move, it is unclear if he would be able to return to power with a majority.

The formation of a strong government after decades of political instability was expected to lead to a socioeconomic transformation of Nepal. Regardless of the SC’s decision, the country is likely to see an escalation of political tensions in the days ahead. The internal rift that led to the December parliamentary dissolution and the political dimensions of the current predicament along with the domestic and geopolitical implications of internal political instability will lead to a serious and long-term weakening of Nepal’s democratic fabric.

Power Sharing and Legitimacy in the NCP

Differences between NCP chairs Oli and former Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal have largely premised on a power-sharing arrangement, leading to a vertical division in the party. In the December 2017 parliamentary elections, a coalition between the Oli-led Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist or UML) and the Dahal-led Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center or MC) won nearly two-thirds of the seats. In May 2018, both parties merged to form the NCP. However, internal politics weakened this merger. While both the factions claim to represent the authentic party, the Election Commission has sought clarifications from both factions before deciding on the matter. According to the Political Party Act , the faction that can substantiate its claim by providing signatures of at least 40 percent of its central committee members is eligible to get recognized as the official party. The faction that is officially recognized will get the privilege of retaining the party and election symbol, while the unrecognized faction will have to register as a new party which can hamper its future electoral prospects. A faction led by Dahal and former Prime Minister Madahav Kumar Nepal, was planning to initiate a vote of no-confidence motion against Oli but, sensing an imminent threat to his position, Oli decided to motion for the dissolution of the parliament.

Internal Party Dynamics

Several internal political dynamics have led to the current state of turmoil within the NCP. Dahal has accused Oli of disregarding the power-sharing arrangement agreed upon during the formation of NCP according to which Oli was supposed to hand over either the premiership or the executive chairmanship of the party to Dahal. In September 2020, both the leaders reached an agreement under which Oli would serve the remainder of his term as prime minister and Dahal would act as the executive chair of the party. Yet, Oli failed to demonstrate any intention to relinquish either post, increasing friction within the party. Additionally, Oli made unilateral appointments to several cabinet and government positions, further consolidating his individual authority over the newly formed NCP. He also sidelined the senior leader of the NCP and former Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal, leading Nepal to side with Dahal over Oli. Consequently, Oli chose to dissolve the parliament and seek a fresh mandate rather than face a vote of no-confidence. Importantly, party unity between the Marxist-Leninist CPN (UML) and the Maoist CPN (MC) did not lead to expected ideological unification.

Domestic Politics and Geopolitics

Geopolitical factors and external actors have historically impacted Nepal’s domestic political landscape. Recently, in a bid to cement his authority over the NCP, Oli has attempted to improve ties with India—lately strained due to Nepal’s inclusion of disputed territories in its new political map—resulting in recent high-level visits from both countries. India has also provided Nepal with one million doses of COVID-19 vaccines as part of its vaccine diplomacy efforts in the region. However, while India has previously interfered in Nepal’s domestic politics , it has described the current power struggle as an “ internal matter ” to prevent backlash from Nepali policymakers and to avoid a potential spillover of political unrest.

However, India’s traditionally dominant influence in Nepal has been challenged by China’s ascendancy in recent years. Due to fears of Tibetans potentially using Nepal’s soil to conduct anti-China activities, China considers Nepal important to its national security strategy. Beijing has traditionally maintained a non-interventionist approach to foreign policy; however, this approach is gradually changing as is evident from the Chinese ambassador to Nepal’s proactive efforts to address current crises within the NCP. Nepal’s media speculates that China is in favor of keeping the NCP intact as the ideological affinity between the NCP and the Communist Party of China could help China exert its political and economic influence over Nepal.

Although China is aware of India’s traditionally influential role in Nepal, it is also skeptical of growing U.S. interest in the Himalayan state; especially considering Oli’s push for parliamentary approval of the USD $500 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) grant assistance from the United States to finance the construction of electrical transmission lines in Nepal. In contrast, Dahal has opposed the MCC and has described it as part of the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Strategy to contain China. Given Nepal is a signatory to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing might prefer development projects under the BRI framework and could lobby the Nepali government to delay or reject U.S.-led projects.

Implications for Future Governance

After the political changes of 2006 which ended Nepal’s decade-long armed conflict, it was expected that political stability would usher in economic development to the country. Moreover, a strong majority government under Oli raised hopes of achieving modernization. Sadly, ruling party leaders have instead engaged in a bitter power struggle, and government corruption scandals have undermined trust in the administration.

Amidst the current turmoil within the NCP, the main opposition party, Nepali Congress (NC), is hoping that an NCP division will raise its prospects of coming to power in the future. Although the NC has denounced Oli’s move for snap elections as unconstitutional, it has also stated that it will not shy away from elections if the SC decides to dissolve the lower house. Sensing increasing instability, several royalist parties and groups have accused the government of corruption and protested on the streets for the reinstatement of the Hindu state and constitutional monarchy to reinvent and stabilize Nepal’s image and identity.

The last parliamentary elections had provided a mandate of five years for the NCP to govern the country. However, Oli decided to seek a fresh mandate, claiming that the Dahal-Nepal faction obstructed the smooth functioning of the government. Unfortunately, domestic political instability has resurfaced as the result of an internal personality rift within the party. This worsening democratic situation will not benefit either India or China—both want to circumvent potential spillover effects. Even if the SC validates Oli’s move, elections in April are not confirmed. If elections were not held within six months from the date of dissolution, a constitutional crisis could occur. If the Supreme Court overturns Oli’s decision, he could lose his position as both the prime minister and the NCP chair. Regardless of the outcome, Nepali politics is bound to face deepening uncertainty in the days ahead.

This article was originally published in South Asian Voices.

Recent & Related

About Stimson

Transparency.

- 202.223.5956

- 1211 Connecticut Ave NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20036

- Fax: 202.238.9604

- 202.478.3437

- Caiti Goodman

- Communications Dept.

- News & Announcements

Copyright The Henry L. Stimson Center

Privacy Policy

Subscription Options

Research areas trade & technology security & strategy human security & governance climate & natural resources pivotal places.

- Asia & the Indo-Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

Publications & Project Lists South Asia Voices Publication Highlights Global Governance Innovation Network Updates Mekong Dam Monitor: Weekly Alerts and Advisories Middle East Voices Updates 38 North: News and Analysis on North Korea

- All News & Analysis (Approx Weekly)

- 38 North Today (Frequently)

- Only Breaking News (Occasional)

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

In Nepal, Post-Election Politicking Takes Precedence Over Governance

The latest bout of coalition politics glosses over the country’s troubling drift toward further political instability.

By: Deborah Healy; Sneha Moktan

Publication Type: Analysis

This past November, Nepalis participated in the second federal and provincial election since its current constitution came into effect in 2015. With 61 percent voter turnout , notably 10 percent lower than the 2017 general elections, the polls featured a strong showing from independent candidates.

Almost half of the incumbent members of parliament — even former premiers, cabinet ministers and party leaders — lost their seats to independents or new political rivals. Amid the political instability that has wracked Nepal over the past several years, including a near constitutional crisis in 2021, the electorate appeared to be holding political leaders accountable at the ballot box for putting politicking above governing.

A Surprising Coalition in Parliament

However, what followed election day has dampened hopes for political reform or renewal. Spurred by public resentment toward the established parties, no single party or existing coalition secured a parliamentary majority. Most expected that the outgoing government, led by the Nepali Congress party, would form a new majority following a brief period of negotiation. However, talks between the Nepali Congress’ outgoing Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba and Pushpa Kamal Dahal, leader of Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Centre (CPN-MC), broke down when the two failed to agree on who would hold the post of prime minister.

After talks with the Nepali Congress ended, Dahal, who is often known by his nom-de-guerre “Prachanda” from his time leading insurgent forces during Nepal’s decade-long civil war from 1996-2006, swiftly brokered a new alliance with his sometime rival, sometime ally KP Sharma Oli and the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML). The two men agreed they would rotate the prime minister’s office between them, with Prachanda serving as prime minister first. With this agreement in hand, Prachanda was sworn in as prime minister on December 26.

Two weeks later, Prachanda was constitutionally obligated to face parliament for a confidence vote. In a surprising reversal, the Nepali Congress and other parties in the opposition announced that they, too, would support the new governing coalition — giving Prachanda a unanimous vote of confidence.

Some analysts suggest this was an attempt by the Nepali Congress to undermine Prachanda’s alliance from the outset by giving Prachanda and the CPN-MC a back-up coalition partner-in-waiting should their pact with the CPN-UML fall through. This would weaken Oli and the CPN-UML’s negotiating power in the new government. The move also dilutes parliamentary checks and balances and calls into question the opposition’s ability to independently scrutinize the actions of a prime minister and government that it helped put in place.

The unanimous vote of confidence creates issues for Prachanda as well, as he must now manage a multi-party coalition representing a spectrum from Marxists to monarchists. Meanwhile, Nepali citizens once again are frustrated and disappointed to see a government formed by parties that have lost a significant number of electoral seats acquire the lion’s share of cabinet positions.

Ongoing Struggle to Implement Federalism

Nepal’s political theme for the last decade has been precarity, and this latest political theater comes amid some worrying trends. Governments rarely run full terms and politicians have played musical chairs with political appointments. Meanwhile, closed-door power-grabs have undermined the electorate’s will. In the seven years since Nepal became a federal state, any initial optimism for the success of federalism has largely waned.

In 2021, only 32 percent of Nepalese said they were satisfied with provincial governments, and chief ministers have complained about the federal government’s reluctance to implement federalism. Provincial assemblies have received limited funding, resources and capacity building support to enable them to be an effective tier of government.

With the outcomes of the 2022 general elections, federalism will continue to face challenges. The governing coalition’s inclusion of the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP), which served as an umbrella party for the election’s independent candidates, will likely disrupt decisions affecting provincial governments. The RSP are anti-federalism — they did not field any candidates for the provincial government elections, and there were incidents on election day where their supporters visibly rejected Provincial Assembly ballot papers.

With such divergent views within the government, it remains to be seen whether provincial governments will get the support they need to provide effective governance or whether federalism will be able to plant stronger roots in the governance system of Nepal.

Walking a Geopolitical Tightrope

Nepal is wedged between China and India, meaning the country must maintain a delicate balancing act to keep amiable relationships with both powers. While the “left-leaning” parties such as CPN-UML and CPN-MC, who have traditionally been seen as being close to China, seek to strengthen those ties, Nepal has deep historical, cultural and religious ties to India.

However, in recent years, the relationship between Nepal and India has at times been fractious — especially when communist parties have occupied the prime minister's office in Nepal and the right-leaning Modi has occupied the prime minister's office in Delhi.

When Nepal was reeling from devastating earthquakes in 2015, there was an unofficial Indian blockade at the border later that year, which soured India-Nepal relations and saw Oli look to Beijing for support. And in 2019-2020, nationalistic sentiment both in Delhi and Kathmandu — when Oli was prime minister — came to the fore over disputed territories along the border, with both governments re-drawing the demarcations set out in the Sugauli Treaty of 1816.

While accusations of foreign interference in domestic politics have increased over recent years, the domestic political flux has actually made it difficult for foreign powers to negotiate, influence or broker power dynamics in a sustained manner. With fluid alliances and an average of just under one prime minister per year for the past 15 years in Nepal, neither China nor India seems to be able to pull geopolitical strings in the country for a sustained period.

The rollercoaster fate of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact further emphasizes this point. The MCC agreement provides $500 million in U.S. grants to support programs to improve electricity and transportation in Nepal. And while the previous Nepali Congress-led government got MCC ratification over the line, it was only after months of protests against the MCC that were fuelled largely by misformation. Now that the MCC is ratified, high-level U.S. officials have been visiting Nepal in quick succession .

While Prachanda’s political victory was welcomed by media outlets in Beijing, given the diverse political ideologies among the coalition, foreign powers near and far will likely struggle to identify true power brokers and influence national politics. On the other hand, this diplomatic uncertainty also makes it harder to build long-term sustained international relations.

Disinformation Continues to Fuel Conflict

In addition to Nepal’s political instability and diplomatic balancing act, social media has been rife with false information on various issues over the past few years, most notably the MCC. Disinformation around the MCC stoked concerns around Nepal’s sovereignty and fuelled several protests in Nepal in 2022.

The elections saw an uptick in this misinformation and disinformation, with doctored images, forged documents and false claims regarding various political leaders, as well as the former U.S. ambassador to Nepal, circulating over social media. This only served to stoke further allegations of U.S. interference in Nepal’s politics. Should this narrative be allowed to continue, it has the potential to fuel further anti-American sentiment in Nepal.

As political parties, politicians and allegedly foreign actors continue to utilize social media to control or twist narratives, senior journalists fear that the worst is yet to come for Nepal in terms of organized disinformation campaigns. In a country where political dissatisfaction has been simmering for decades, and with the government preoccupied with smoothing over the differences in the coalition, such campaigns could trigger political unrest and violence.

The Lack of Women on the Ballot

Nepal’s parliamentary electoral system is split: Voters are asked to choose from a list of candidates for their district’s parliamentary seat as well as for a political party in the country’s proportional representation (PR) system. 165 members of parliament are directly elected to parliament, while the remaining 110 seats are filled based on parties’ vote share in PR list results.

Out of the 4,611 candidates who directly contested seats in the federal parliament, only 225 (9.3 percent) were women. Of this number, only 25 were fielded by the main political parties. The lack of female candidates on the ballot resulted in only nine being directly elected in the country’s first-past-the-post system — only three more than in 2017.

To meet the constitutionally mandated one-third female representation rule, political parties fielded more female candidates under the PR list system. The PR list system was meant to provide electoral opportunities to women and candidates from marginalized and indigenous communities — but members of parliament can only serve one term through the PR list. The intent was to give these underrepresented groups a chance to build experience, after which they could contest a directly elected seat.

Instead, Nepal’s major political parties have repeatedly taken the easy option of nominating new female candidates to the PR list system to ensure they meet the one-third quota rather than nominate experienced women for directly elected seats.

While the parties are fulfilling the constitutional obligations by meeting the quota, there seems to be little long-term investment in developing women leaders. Going forward, the parties need to do more to increase female and marginalized community representation and promote a more representative and inclusive parliament that reflects the spirit of the constitution — not one dominated by the same figures who wish to maintain the status quo.

Where Does Nepal Go from Here?

The past two decades have yielded significant transitions for Nepal: a peaceful resolution to the decade-long Maoist conflict, as well as the end of monarchy and the promulgation of a new constitution that upheld secularism, inclusion and federalism.

But this positive momentum seems to now be staggering, with the same actors from several decades ago largely interested in maintaining a status quo while inflation steadily rises and federalism struggles.

While political forecasting in Nepal continues to be as accurate as reading tea leaves, there continues to be concerns about prolonged political instability — as can be seen by the fragility of the current coalition, which is already in danger of collapsing with the withdrawal of RSP, the third largest coalition partner.

Throw in the upcoming and contentious question of which party gets to nominate the president, and the Nepali people are once again left to witness blatant politicking at the expense of timely attention to economic and governance challenges.

Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry has warned that funding to provincial and local governments could be cut as a result of economic concerns. The entire federal system will be undermined if governments cannot deliver on services and development. Federalism was envisaged as a vehicle for economic development and if it flounders, it could have an impact on Nepal’s graduation to a lower middle-income country in 2026 based on the World Bank’s projections .

Still, the U.S. government sees Nepal as one of two places in Asia with an excellent opportunity for inclusion in the Partnership for Democratic Development. And with high-profile visits from U.S. government officials and scheduled high-profile visits from European governments on the way, there is an opportunity for the international community to urge Nepal’s government to stop politicking and start governing so that Nepal can flourish as a truly democratic nation that respects the rights of the many and not the few.

Deborah Healy is the senior country director for Nepal at the National Democratic Institute.

Sneha Moktan is the program director for Asia-Pacific at the National Democratic Institute.

Related Publications

China’s Engagement with Smaller South Asian Countries

Wednesday, April 10, 2019

By: Nilanthi Samaranayake

When the government of Sri Lanka struggled to repay loans used to build the Hambantota port, it agreed to lease the port back to China for 99 years. Some commentators have suggested that Sri Lanka, as well as other South Asian nations that have funded major infrastructure projects through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, are victims of “China’s debt-trap diplomacy.” This report finds that the reality is...

Type: Special Report

Environment ; Economics

Nonformal Dialogues in National Peacemaking

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

By: Derek Brown

Nonformal dialogues offer complementary approaches to formal dialogues in national peacemaking efforts in contexts of conflict. As exemplified by the nonformal dialogues in Myanmar, Lebanon, and Nepal examined in this report, nonformal dialogues are able to...

Type: Peaceworks

Mediation, Negotiation & Dialogue ; Peace Processes

Connecting Civil Resistance and Conflict Resolution

Thursday, August 10, 2017

By: Maria J. Stephan ; Tabatha Thompson

In 2011, the world watched millions of Egyptians rally peacefully to force the resignation of their authoritarian president, Hosni Mubarak. “When Mubarak stepped down … we realized we actually had power,"...

Nonviolent Action ; Mediation, Negotiation & Dialogue

Reconciliation and Transitional Justice in Nepal: A Slow Path

Wednesday, August 2, 2017

By: Colette Rausch

In 2006, the government of Nepal and Maoist insurgents brokered the end of a ten-year civil war that had killed thousands and displaced hundreds of thousands. The ensuing Comprehensive Peace Agreement laid out a path to peace and ushered in a coalition government. Nepal’s people were eager to see the fighting end. Their political leaders, however...

Type: Peace Brief

Reconciliation ; Justice, Security & Rule of Law

Nepal Politics Youth Participation in Politics: Shared vision and sustainability of federalism in Nepal

Youth protests in Nepal

Across the world, the youth has played a historically significant role in major political revolutions. What has also been seen is those young people who frequently lead protests but are not later included informal political proceedings are left frustrated, resulting in destabilization of the democratization process, which later leads to conflicts. To avoid adversities in the political and civil environments of a nation, encouraging the active participation of young people in these processes is thus necessary. This is the only way to frame a shared vision within a country.

Political transitions in Nepal have been a recurrent phenomenon. Since the 1950s, Nepal has witnessed major revolutions and regime changes every ten years – encompassing the Rana regime, one of democracy, the panchayat era, one of multi-party democracy, one involving the abolition of the monarchy, and another of federalism. One of the fundamental factors behind these frequent transformations has been the inability of the general populace to realize tangible benefits from the existent political system in the country.

Nepalese youth have always been at the forefront of these revolutions – they have fought at the frontline with the hope of reforms, to facilitate positive changes in society. However, the political representation of the youth in formal politics remains limited. Conventional political parties have, for a long time, used their young cadres in all political struggles, only to leave them out of proportional engagement in leadership roles, be it in parties or in governance. To this day, only 5 percent of the Nepali youth is represented in the federal parliament, as opposed to the global average of 13.5 percent. This is despite the fact that the definition of youth encompasses individuals between 16 to 40 years of age in Nepal, whereas a majority of countries including India, China, Pakistan, and the UK has limited the age of youth to 29; some countries, like Bhutan and the USA, have limited the definition to those below 25. This implies that the hopes and aspirations of young people regarding their economic development and Nepal’s future have never been translated into the national political agenda. The under-representation of youth in formal politics is a manifestation of top leaders’ parochial attitudes.

The low participation of youth in formal politics is attributable to several factors, amongst which specific legal provisions of the country and the unwillingness of political leaders to hand over leadership roles to the young are the foremost. The legislations state that an individual can contest in local elections only from the age of 21 and must wait until s/he reaches 25 years to contest provincial and federal elections. Furthermore, for an individual to be a part of a constitutional committee, s/he needs to be 45 years of age. In other words, the constitution of Nepal does not favor youth participation. The legislation also sets a convenient pretext for politicians to continue to be engaged in politics post-retirement. Consequently, Nepal is led by septuagenarian leaders; perhaps they’ve designed the system thus to serve their own political interests.

Around the globe, the youth are encouraged to participate in political processes, and numerous steps are taken, such as disseminating information on their rights to be involved in political processes, their training and their involvement to equip them for decision making. However, the same actions are absent in Nepal. For many youths, the idea that they can influence decisions made by the government seems too abstract, and the issues that engage and concern adults seem out of reach and (in many cases) irrelevant to their current lives. This has adversely affected political participation and awareness amongst the younger generation – often resulting in lesser engagement of the youth in political discourse and voting.

Federalism has provided Nepal a chance to change this and incentivize higher youth participation in politics. There are currently 36,000 elected representatives in local units alone. This can be viewed as a dividend of federalism, whereby Nepal can test its youth as well as train them for higher levels of political participation and decision-making. In fact, political representation of youth in local elections has been noteworthy. The May 13 local elections saw 41% youth participation in terms of candidacy. However, Nepal would do well to incentivize greater youth participation, with that of youth under the age of 30 standing at a mere 15.32 percent. This is very important for the sustainability of our federalism.

As representatives of the political system, youth is a quintessential aspect of modern democracy. Engaging young people in formal political processes certainly help shape politics in a way that contributes to the building of stable and peaceful societies that promptly respond to the needs of the general populace; the younger generation usually fosters its own unique and innovative strain of thinking, being full of energy as well as a passion for contributing to the improvement of its respective countries.

At Samriddhi Foundation, we realize the importance of working with the youth and helping them prepare themselves for political participation. We have developed a number of avenues to practice this philosophy. We engage them in Socratic discussions of liberal values like skepticism of power, individual freedom, rule of law, private property rights, markets, and competition so that they can bring an alternative lens to the development discourse. We also engage them in regular dialogues on contemporary policy processes so that they can test their ideas among political and apolitical leaders. We bring together young thinkers to informal discussion tables and help them exchange their ideas with each other to promote collective learning. A host of such youth-centered activities showcases our humble efforts to create a pipeline of educated and capable young individuals who could be leaders and change-makers tomorrow.

Youth Participation in Nepal Politics: Sharing Experiences

- FB Live Stream

- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

- Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- Sandeep Lamichhane

- Giri Bandhu Tea Estate controversy

- JSPN splits

- Lithuania-Nepal ties

- 2024 Kantipur Half Marathon

Insights into the modern political history of Nepal

Deepak Adhikari

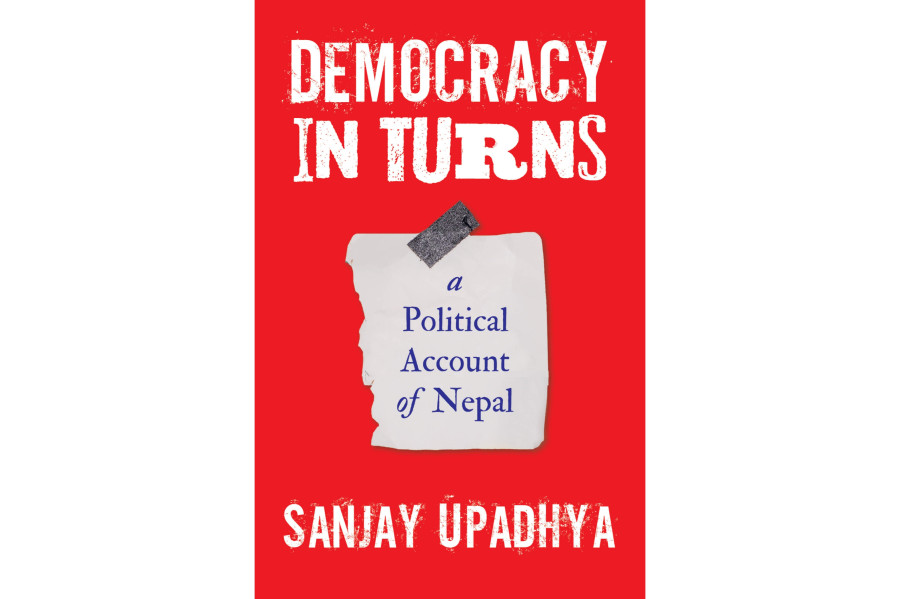

Author and geopolitical analyst Sanjay Upadhya explores Nepal’s complex political landscape in his most recent book, ‘Democracy in Turns: A Political Account of Nepal . ’ This is Upadhya’s fifth book. In his earlier works, he tackled Nepal’s political transformation after the end of the Maoist insurgency and the rivalry between China and India in Nepal and wrote about how India adopted British colonial policies vis-à-vis Nepal after its independence from the empire.

A year ago, through the publication of ‘Empowered and Imperiled: Nepal’s Peace Puzzle in Bits and Pieces,’ Upadhya exposed himself as the pseudonymous blogger behind sharp takes on Nepali politics that were published in the popular blog Nepali Netbook , where he wrote under ‘Maila Baje’.

Upadhya attempts to give readers a thorough overview of modern Nepali history, focusing on the political transformation beginning in the 1990s. And like most authors who write about Nepal’s modern history, he begins with the conquest of petty kingdoms by Prithvi Narayan Shah and his armies. When you begin at this historical juncture, you have to narrate the court intrigues and massacres in the palace until the end of the Rana autocracy. The author dutifully paints the period with short brushes.

One admirable quality of ‘Democracy in Turns’ is Upadhya’s presentation of a survey of modern Nepali history, allowing readers to grasp an overview of the country’s political landscape. The title chapter at the end provides a summary of the preceding chapters. The book ends with the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the parliament dissolution recommended by the Oli government on February 23, 2021. Upadhya has crammed all the significant events of the country’s modern history into 280 pages.

Such an ambitious project is bound to face challenges. Rather than providing new insights or original analysis, the book primarily recycles recent history. While some readers may appreciate the brevity and clarity of the writing style, others might yearn for a more in-depth exploration of the last 30 years of Nepali history.

Upadhya assumes a certain level of familiarity with the inside accounts of recent Nepali history, making it a challenging read for those less versed in the country’s political context. ‘Democracy in Turns’ demands prior knowledge or additional research about these events. Explaining historical events is just as important as chronicling them. The book fails to do this adequately.

One aspect that may disappoint readers is the author’s heavy reliance on international sources such as The New York Times, Time, and The Washington Post. Although these sources provide valuable perspectives, a more extensive inclusion of Nepali language publications would have offered more significant insights. The book may neglect the nuances and complexities of Nepal’s political landscape as experienced by Nepalis because it mostly draws from foreign and English sources. One book that comes to mind for its focus on local sources is ‘ People, Politics and Ideology: Democracy and Social Change in Nepal ’, which covers the two pro-democracy revolutions of 1950 and 1990.

Nevertheless, ‘Democracy in Turns’ does offer insightful commentary in certain instances. An example is when the author exposes the political parties’ deception: “Most parties acknowledged the political, social and economic grievances behind the movement while in opposition. Once in power, they relied on the reinforcement of police units.” The book captures the fast-paced political transformation during the period between the launch of the Maoist insurgency and the subsequent peace process. This roller-coaster period in Nepal’s recent history deserves a book of its own, given the intensity of the events that unfolded over the decade.

The book occasionally suffers from disjointed sentences that fail to build narrative tension—a common pitfall when attempting to condense a lengthy history into concise passages. Some sections present weighty sentences about consequential moves without adequately explaining their implications.

For example, the book talks about the transition from an autocratic Panchayat regime to constitutional monarchy and multi-party democracy in the 1990s: “[Prime Minister Krishna Prasad] Bhattarai then turned to dismantle the structure of the Panchayat regime to facilitate the functioning of the interim government.” The book provides no further elaboration on this, swiftly describing Bhattarai’s subsequent challenges of holding elections and drafting a constitution. The book also seems to display a bias in favour of the Shah monarchy, portraying it as benign while blaming its demise on the political parties and their dysfunction.

The book highlights the Maoist duplicity during the war and their dexterity at playing off power centres in Kathmandu and New Delhi. In contrast, the portrayal of King Gyanendra’s unconstitutional move is watered down, failing to adequately demonstrate the implications of what Indian journalist Siddharth Varadarajan defined as a “monumental folly.”

Here is what happened: The Royal Takeover led to a crackdown on civil spaces, including news media. Gyandendra eschewed anti-corruption agencies such as CIAA and set up an unconstitutional body, appointing his henchmen. The goal was not to crack down on corruption but to weaken the pro-democracy movement. He relied on a coterie of outdated politicians (like Tulsi Giri) who weren’t in sync with changing times.

Despite its limitations, ‘Democracy in Turns’ is a valuable primer on Nepal’s recent political history. It offers readers a starting point from which they can explore and deepen their understanding of the country’s democratic journey. Upadhya gives readers a foundation on which to build further knowledge by summarising the important events.

Democracy in Turns: A Political Account of Nepal

Author: Sanjay Upadhya

Publisher: FinePrint

Deepak Adhikari Adhikari is a freelance journalist based in Kathmandu.

Related News

Writing stories rooted in culture

FACTS of Nepal 2024 launched

My writings blend Nepali heritage with diasporic flavour

Reading today is more important than ever for critical observation

Why myths are always relevant

Writers should explore all aspects of their identity in writing

Most read from books.

Editor's Picks

Is judicial supremacy trumping constitutional supremacy in Nepal?

Between politics and education

Kagbeni residents fear monsoon havoc amid government inaction after last year’s flooding

Nepal’s agriculture, water resources under climate threat

Ilam bypoll: Fillip for old parties, reality check for RSP

E-paper | may 17, 2024.

- Read ePaper Online

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Language politics in Nepal: A socio-historical overview

This paper aims to outline the language politics in Nepal by focusing on the influences and expansions shifted from Global North to the Global South. Based on a small-scale case study of interviews and various political movements and legislative documents, this paper discusses linguistic diversity and multilingualism, globalization, and their impacts on Nepal’s linguistic landscapes. It finds that the language politics in Nepal has been shifted and changed throughout history because of different governmental and political changes. Different ideas have emerged because of globalization and neoliberal impacts which are responsible for language contact, shift, and change in Nepalese society. It concludes that the diversified politics and multilingualism in Nepal have been functioning as a double-edged sword, which on the one hand promotes and preserves linguistic and cultural diversity and on the other hand squeezes the size of diversity by vitalizing the Nepali and English languages through contact and globalization.

1 Introduction

Nepal is a multilingual, multicultural, multiracial, and multi-religious country. Despite its small size, Nepal is a country of linguistic diversity with four major language families, namely, Indo-Aryan, Tibeto-Burman, Dravidian (Munda), and Austro-Asiatic, and one language isolate, Kusunda ( Poudel and Baral 2021 ). The National Population and Household Census 2011 ( Central Bureau of Statistics 2012 ) records the number of speakers for 123 languages and some other includes an additional category of ‘other unknown languages’ with close to half a million speakers. The state intervention to preserve and promote these languages remained inconsistent throughout history, as some governments intentionally discouraged the planned promotion compared to others which designed some measures to promote them. Both monolingual and multilingual ideologies remained as points of debate in political and social spaces.

Language politics is the way language is used in the political arena in which people can observe the treatment of language by various governmental and non-governmental agencies. Research related to language politics focuses on identifying and critiquing any sets of beliefs about language articulated by users as a rationalization or justification of perceived language structure and use ( Dunmre 2012 : 742; Silverstein 1979 : 193). In this context, every political movement is the outcome of different conflicting ideas between language users and linguistic differences running through any society ( Pelinka 2018 ). The politics of language choice becomes particularly difficult when institutional choices have to be made in what language(s) the government will conduct its business and communicate its citizens, and, above all, what the language(s) of education will be ( Joseph 2006 : 10). Nepal’s language politics and democratic movements question whether democracy can promote linguistic diversity, or narrow down diversity by marginalizing ethnic/minority languages. In Nepal, linguistic diversity and democracy have been challenged by the contradiction between the normative assumption of existing demos and the reality of a society that is too complex to be defined by one orientation only by nation, culture, and religion ( Pelinka 2018 : 624). Nepal’s language politics has not been explained from such a perspective where we can see several factors influencing the issues related to language, culture, and society. Hence, this paper tries to overview the language politics in Nepal which has been influenced by various external and internal factors.

2 Brief history of language politics in Nepal

Following the Gorkha [1] conquest, Gorkhali or Khas (now known as Nepali), the language of ruling elites and mother tongue of many people in the Hills, was uplifted as the national official language in Nepal. After unification, [2] a hegemonic policy in terms of language and culture was formulated which promoted the code (linguistic and dress) of the Hill Brahmins, Chhetries, and Thakuris to the ideal national code (i.e. Nepali language and Daura Suruwal Topi-dress [3] ). This has been interpreted as one of the attempts to promote assimilatory national policy (in terms of language and culture) that contributed to curbing both linguistic and cultural diversity. However, for the rulers then, it was an attempt to establish a stronger national identity and integrity. The Rana regime further prolonged this ‘one nation-one language’ policy by uplifting the Nepali language in education and public communication. The Rana, during their rule, suppressed various language movements (Newar, Hindi, Maithili, etc.), which serves as evidence of their deliberate plan to eliminate all but one language, viz. Nepali. In this sense, we can understand that Nepal’s diversity and multilingual identity were suppressed historically in the name of nation-building and promoting national integration among people with diverse ethnic and cultural orientations.

Following the end of the Rana oligarchy in 1950, with the establishment of democracy, some changes were noticed concerning the recognition and mainstreaming of the other ethnic/indigenous languages. This instigated the policy change in terms of language use in education as well. However, the status quo of the Nepali language further strengthened as it was made the prominent language of governance and education. The Education in Nepal: Report of the Nepal Education Planning Commission ( Sardar et al. 1956 ), the first national report on education, basically reflected the ideology of monolingualism with the influence of Hugh. B. Wood. It stated, “If the younger generation is taught to use Nepali as the basic language then other languages will gradually disappear” ( Sardar et al. 1956 : 72). Though this report formed the backbone of Nepal’s education system, it also paved the way for minimizing the potential for empowering the languages of the nation. Pradhan (2019 : 169) also writes that this commission attempted to “coalesce the ideas of Nepali nationalism around the “triumvirate of Nepali language, monarchy, and Hindu religion”. The same idea was reinforced by K. I. Singh’s government in 1957 by prescribing Nepali as the medium of instruction in school education.

The Panchayat regime also promoted the use of Nepali as the only language of administration, education, and media in compliance with the Panchayat slogan ‘one language, one dress, one country’ ( eutaa bhasha, eutaa bhesh, eutaa desh ), again providing a supportive environment for strengthening the monolingual nationalistic ideology (i.e. the assimilatory policy). Not only in education but also in governance, English or Nepali language was made mandatory in recording all documents of companies through the Nepal Companies Act 1964 ( Government of Nepal 1964 ). Following the Panchayat system, with the restoration of democracy in 1990, the Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal 1990 ( Government of Nepal 1990 ) provisioned the Nepali language written in Devanagari script [4] as the national language, and also recognized all the mother tongues as the languages of the nation with their official eligibility as the medium of instruction in primary education. The Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063 ( Government of Nepal 2007 ), which came as a collective outcome of the various political movements and Andolan II continued to strengthen the Nepali language, but ensured (in Part 1, Article 5.2) that each community’s right to have education in their mother tongue and right to preserve and promote their languages, script, and culture as well.

The recognition of all the mother tongues as the languages of the nation was a progressive step ahead provisioned by the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063. Apart from further confirming the right of each community to preserve and promote its language, script, culture, cultural civility, and heritage, the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063 (Part 3, Article 17) clearly explained the right to each community to acquire basic education in their mother tongue as provided for in the law. The same was well articulated in the Constitution of Nepal 2072 ( Government of Nepal 2015 ) as well, and each state was given the authority to provide one or many languages spoken by the majority population as the official languages. Along with this, the language commission was established in 2016 to study and recommend other issues related to language and multilingualism (Part 1, Article 7 of the Constitution of Nepal 2072 ). However, it can be realized that these policy provisions that embrace diversity will have less effect if the concerned communities or agencies do not translate them into practice.

3 Research method

This study, following a qualitative approach, is based on a small-scale case study with primary and secondary data sets.

The author has obtained the primary data from semi-structured interviews with two selected individuals who have spent their lives in politics and especially language movements and advocacy for language preservation and promotion in Nepal. They were observed and interviewed informally on many occasions from 2019 to 2020 related to language issues like constitutions, language movements, language diversities and democracy, and so on. The interviews (altogether 3 h each) were recorded, transcribed, and translated into English, and were checked for accuracy and reliability.

Mr. Yonjan and Dr. Thakur [5] have been selected from two different political and linguistic backgrounds. Mr. Yonjan is a liberal democratic fellow who has been working as a freelance language activist for more than 40 years, involving himself in many governmental and non-governmental policies and programs related to language issues. Dr. Thakur worked as a politician (left-wing) and teacher educator who later joined Radio Nepal, engaged in various cultural advocacy forums of the ruling Communist Party of Nepal, and again moved to politics at the later part of his life. He was a member of the parliament in the Constituent Assembly. Mr. Yonjan is the native speaker of Tamang (a major Tibeto-Burman language) and Dr. Thakur is a native speaker of Bhojpuri (a major Indo-Aryan language), and both of them learn Nepali as a second language. In that, both of the individuals have active engagement in language politics and planning, however, are from different cultural, linguistic, and geopolitical backgrounds. It is assumed that their ideas would make the understanding of language politics in Nepal more enriched.

The secondary data is obtained from a detailed reading of available literature about language politics. Nepal’s language and educational history, various political movements, constitutions and legislative documents, policy documents, and other published research papers and documents have been carefully utilized.

4 Findings and discussion

Language politics in Nepal has a very long history since the beginning of modern Nepal. After the victory of Prithvi Narayan Shah, a Gurkha King whose mother tongue was Khas (Nepali), in Kathmandu valley (1769), Nepali became the language of law and administration ( Gautam 2012 ) where the vernacular language was Newar spoken by the majority of people. Since then, language politics has become the center of democratic and political movements in Nepal.

Nepali language was highlighted and became the language for all public and private activities after the Unification Movement (1736–1769) in Nepal. Janga Bahadur Rana’s visit to the United Kingdom and his relation to British India made it possible for the Nepalese rulers to start English Education formally in Durbar High school in 1854. After Rana Regime, Nepal experienced an unstable political scenario for 10 years before the establishment of the Panchayat Regime in 1961 which employed assimilatory language policy until 1990. The country was converted into a multiparty democratic system and eventually, most of the ethnic and minority linguistic groups flourished for the preservation and documentation of their ethnic and cultural heritages. At present, Nepalese politics has been influenced by ethnic, cultural, and language issues at the center.

4.1 Legal and constitutional provisions

Nepalese constitutions are the main sources of language politics in Nepal. Before the construction of the constitution in the country, some government policies played a vital role in creating language issues debatable all the time. The first legal court Muluki Ain [6] (1854) enforced Hinduisation and Nepalization in Nepal by ignoring most of the other ethnic languages. The establishment of the Nepal National Education Planning Commission (NNEPC) by the recommendation of the National Education Board of the Government of Nepal emphasized the Nepali language by implementing it as a medium of instruction in all levels of education.

The medium of instruction should be the national language (Nepali) in primary, middle, and higher educational institutions because any language which cannot be made lingua franca and which does not serve legal proceedings in court should not find a place. The use of national language can bring about equality among all classes of people. ( Sardar et al. 1956 : 56)

This excerpt indicates the emphasis given to the Nepali language by the government then. The use of Nepali in education was further reinforced by the K. I. Singh government in 1957 by prescribing Nepali as the medium of instruction. The case of Nepali was again strengthened during the Panchayat regime. In 1961, the National System of Education was introduced to promote the use of only Nepali in administration, education, and media in compliance with the Panchayat’s popular slogan of ‘one language, one dress, and one country’. In addition, the Nepal Companies Act was passed in 1964 directing all companies to keep their records in English or Nepali. The Panchayat constitution followed a nationalist assimilation policy to promote the Nepali language in different ways.

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal 1990 ( Government of Nepal 1990 : 4) framed after the restoration of democracy recognized languages other than Nepali and made the following provisions about the non-Nepali languages:

(1) The Nepali language in the Devanagari script is the language of the nation of Nepal. The Nepali language shall be the official language. (Part 1, Article 6.1) (2) All the languages spoken as the mother tongue in the various parts of Nepal are the national languages of Nepal. (Part 1, Article 6.2)

In addition, the constitution also made a provision for the use of mother tongues in primary education (Part 1, Article 18.2). It also guaranteed a fundamental right to the people to preserve their culture, scripts, and their languages (Part 1, Article 26.2).

Similarly, the Maoist movement that started in 1996 brought new changes and dynamics among all the ethnic minorities of Nepal. This political campaign motivated them to preserve and promote their languages and cultures which has been documented in the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063 . The Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063 ( Government of Nepal 2007 : 2), an outcome of the people’s revolution (Andolan II), made the following provisions for languages:

(1) All the languages spoken as the mother tongue in Nepal are the national languages of Nepal. (2) The Nepali Language in Devanagari script shall be the official language. (3) Notwithstanding anything contained in clause (2), it shall not be deemed to have hindered to use the mother language in local bodies and offices. State shall translate the languages when they are used for official purpose. (Part 1, Article 5)

Regarding education and cultural rights, the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063 ( Government of Nepal 2007 : 8) enshrined the following provisions:

(1) Each community shall have the right to receive basic education in their mother tongue as provided for in the law. (2) Every citizen shall have the right to receive free education from the State up to secondary level as provided for in the law (3) Each community residing in Nepal has the right to preserve and promote its language, script, culture, cultural civilization and heritage. (Part 3 Article 17)

The Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063 was more progressive and liberal than the constitution of 1991. For the first time, this constitution recognized all the languages spoken in Nepal as the national languages. Apart from further confirming the right of each community to preserve and promote its language, script, culture, cultural civility, and heritage, this constitution (Part 3, Article 17) discussed the right to each community to acquire basic education in their mother tongue as provided for in the law. However, the role of the government was to facilitate the speech communities to materialize these rights which still are not effective.

Likewise, the latest Constitution of Nepal 2072 ( Government of Nepal 2015 : 4) has clearly stated the following provisions:

Languages of the nation: All languages spoken as the mother tongues in Nepal are the languages of the nation. (Part 1, Article 6)

Official language: (1) The Nepali language in the Devanagari script shall be the official language of Nepal. (2) A State may, by a State law, determine one or more than one languages of the nation spoken by a majority of people within the State as its official language(s), in addition to the Nepali language. (3) Other matters relating to language shall be as decided by the Government of Nepal, on recommendation of the Language Commission. (Part 1 Article 7)

The Constitution of Nepal 2072 ( Government of Nepal 2015 ) conferred the right to basic education in mother tongue (Article 31.1), the right to use mother language (Article 32.1), and preservation and promotion of language (Article 32.3). This constitution states that each community shall have the right to preserve and promote its language, script, culture, cultural civility, and heritage. Unless the constitution articulates the responsibility of the government to preserve and promote the endangered languages, the efforts of the communities will be useless. Observing and analyzing the legal provisions, Nepal has manifested significant progress and gradual development in the use of languages along with historical events. The key measure of a language’s viability is not the number of people who speak it, but the extent to which children are still learning the language as their native tongue. The Constitution of Nepal 2072 ( Government of Nepal 2015 ) also made the provision of establishing a language commission in article 287 which was a landmark in Nepalese history.

4.2 Democracy and political movements

Nepal’s language politics is guided by various democratic and political movements in different periods. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights ( United Nations 1948 ) asserts that democracy assures the basic human rights for self-determination and full participation of people in the aspects of their living such as decision-making about their language and culture (Article 27). Nepal’s political parties and the ruling governments never understand the seriousness of political movements and democratic practices. Human rights also provide them with ways of assuring social benefits such as equal opportunities and social justice. In Nepal, diversity was promoted by democracy through the policy provisions, especially after the promulgation of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal 1990 . The basic rights for the use of indigenous languages were assured in the constitution as well as other educational acts formed as outcomes of democratic political turns. The changes in the policy provisions provided opportunities for linguists, language rights activists, and advocacy groups or individuals to explore more about their languages and cultures. Due to their attempts, also supported by the democratic political system, new languages were identified, and some others were streamlined through the preparation of educational materials such as textbooks for primary level education. However, pragmatic actions remained fragile for education in the schools to support the aspiration for promoting diversity, which ultimately resulted in squeezing multilingualism. The statistical data shows that the number of languages spoken as mother tongues in Nepal is 129, [7] some scholars still doubt whether these languages functionally exist in reality ( Gautam 2019a ), or if they are there, then the practice may be fragile. In having such a very weak practice in the field, it can be noted that various factors played key roles, including lack of community participation, hegemonic attitude, and agency of the individuals who could have purposive actions.

For instance, the recognition of linguistic diversity in Nepal can be observed clearly after the establishment of multiparty democracy in 1990. Sonntag (2007 : 205) stated that “the Nepali-only policy was discarded in favor of an official language policy that recognized Nepal’s linguistic diversity”. This shows that the democratic political system that remained open to the neoliberal economy embraced linguistic diversity as a resource, due to which the multilingual identity of Nepalese society was officially recognized. However, at the same time, this political system could not preserve the minority/indigenous languages as expected, which prompted us to question the co-existence of diversity and democracy. Also, “[i]t is very much a matter of democracy that everyone has the right to language and that society has a common language that everyone can understand and use” ( Rosén and Bagga-Gupta 2013 : 59). As democratic states (e.g. Nepal, India, and Sweden) which address the contradictory discourses of language rights and develop equal access for everyone to a common language (e.g. Nepali in Nepal) are struggling to settle the language issues. However, the fundamental question still not well-answered, at least in the case of Nepal, is whether democracy can, in a real sense, promote linguistic diversity, or it narrows down the diversity by marginalizing the ethnic/minority languages. While responding to this unanswered concern, this article finds that diversity as a resource and diversity as a problem are the two distinct discourses that emerged during the evolutionary process of democracy in Nepal, which is also emphasized by the two participants.

4.3 Linguistic diversity and politics

Linguistic, cultural, and geographical diversities are the essences of Nepalese democratic practices in different periods in history. Nepal’s modern history starts with the unification campaign of Prithvi Narayan Shah, the first Shah King of Nepal. Prithvi Narayan Shah’s unification modality worked indirectly to promote the politics of assimilation in nation-building, national integration, and identity. Roughly, all other systems of governance following the unification adopted similar ideological orientations, which (in) directly contributed to the marginalization of other mother tongues. Mr. Yonjan expressed his view as, “Historically, even before the unification movement of Nepal, there were several territories in which the state Kings used to speak their own languages, and the linguistic diversity was preserved and strengthened”. He further claimed, “The geopolitical, historical, socio-political, and anthropological history recognized the multilingual social dynamics, however, the national policies after the unification too could not embrace such diversity”. By saying so, Mr. Yonjan expressed that the current political systems and the ideologies of Nepali nationalism were guided by the notion of ultra-nationalism. Dr. Thakur also emphasized that the government’s multilingual policies would not operate as the practice had largely shaped people’s orientation towards Nepali and English, side-lining the regional and local languages. The same perception was reported by Mr. Yonjan as, “Though careful efforts were made in the policy level to promote the regional/local languages through status planning, there still existed the attitudinal problem which undermined the potential of bringing local and minority languages into practice”. Their claims also adhered to the statements made in the documents which reflect the hidden language politics of Nepal.

Both informants in this study argued that diversity has two different outcomes viz. as a resource and as a problem. Mr. Yonjan claims, “If any language of a community dies, the culture and lifestyle of that community disappears and it reduces biodiversity, and that ultimately will be a great threat to humanity”. He understands linguistic diversity as a part of the ecology and strongly argues that it should be protected. Agnihotri (2017 : 185) also echoes a similar belief as “Just as biodiversity enriches the life of a forest, linguistic diversity enhances the intellectual well-being of individuals and groups, both small and large”. But Dr. Thakur views that “In Nepal, along with the history, there remains an ideological problem that diversity is understood as a construct for division, rather than understanding it as a potential tool for nation-building”. He further clears that this community-level ideology and practice has led to the fragmentation of values associated with their languages, most probably harming the socio-historical harmony among languages. Mr. Yonjan further added, “No language should die or move towards the edge of extinction in the name of developing our own existence and condition”. Both Mr. Yonjan and Dr. Thakur pointed out that the discourse on diversity and multilingualism in Nepal had been strengthened and institutionalized after 1990 when the country entered a multiparty democratic system.

However, Mr. Yonjan thinks that the current legislative provisions have partially addressed the diversity needs to fit Nepal’s super diverse context. Dr. Thakur again indicates that the rulers for long “undermined the potential of the linguistic diversity and wished to impose a monolingual national system that marginalized the use of these languages”. Mr. Yonjan also provided a similar view as “in Nepal, throughout the history, there remained a political problem that diversity was understood as a construct for division, rather than a potential tool for nation-building”. His understanding also reflects what was discussed in the western countries as Nettle (2000 : 335) clarifies “the linguistic and ethnic fragmentation relates to low levels of economic development since it is associated with societal divisions and conflicts, low mobility, limited trade, imperfect markets, and poor communications in general”. Therefore, the direct economic benefits from learning a language were a great motivation for the people in the communities. In other words, they have preserved the sentimental functions of the minority languages while they have embraced the dominant languages associating them with educational and economic potential gains. This community-level politics and practices have led to the fragmentation of values associated with their languages, most probably harming the socio-historical harmony among languages. Gautam (2018) has pointed out this concern as a cause of intergenerational shifts in languages among the youths of indigenous languages (such as Newar, Sherpa, and Maithili in Kathmandu Valley). Consequently, this trend has influenced the participation of the relevant communities in campaigns for the revitalization of their languages that points to the influence of the Global North in bringing ultranationalist values in Nepal’s language politics and diversity.

4.4 Impact of globalization

The international political-economic structure seems stacked against a substantial or near future diminishment of “the North-South gap” ( Thompson and Reuveny 2009 : 66). The neoliberal trends that emerged from the Global North have traveled to the Global South, influencing these countries through the language and culture of the countries in the Global North. The unprecedented expansion of English as a global phenomenon ( Dearden 2014 ) can be a good example of such an effect. It involved various combinations of developmental states recalling domestic markets from foreign exporters (import substitution) and the recapture of domestic business (nationalization). The outcome, aided by investments in education, was a new elite of technical managers and professionals who could build on historical experiences and opportunities in the post-war environment to manufacture and market commodities involving increasing product complexity and scale. Migration and demographic changes have had variable impacts on the North-South gap. Nepali youths’ labor migration and their English preference have also influenced the generational shifts in languages ( Gautam 2020 : 140). The youths’ migration to the countries in the Middle East, and their participation in the global marketplaces in the Global North countries have contributed to the reshaping of their ideologies towards the home languages and English. Mr. Yonjan states, “We have made lots of choices in our society and education systems (e.g. choice of language for education, western culture, and lifestyles) attracted by the politics and ideologies created even by our immigrant Nepali population usually in the western world”. Among many, this expression can be understood as one of the causes for stressed deviating tendencies in language shifts, usually from mother tongues or heritage languages and dominant national languages to English. In the context of Nepal, either English or Nepali has been highlighted even though there have been lots of attempts of implementing mother tongue-based multilingual education.

4.4.1 English and globalization

English has become the global language because of its use, function, and popularity in most of the social, cultural, and academic areas. A sizeable body of scholarship has addressed the topic of globalization and its impact on the modern world ( Giddens 1991 ; Levitt 1983 ). Among several definitions, globalization refers to the multifarious transformations in time and place that influence human activities through the creation of linkages and connections across geographical borders and national differences ( Giddens 1991 ; Held et al. 1999 ). In the context of Nepal, these linkages and connections are often facilitated through various globalized activities, such as marketing, transportation, shipping, telecommunications, and banking. Similarly, sociolinguists and language planners have examined the phenomenon of global English and its impact on the linguistic landscape around the world. Crystal (2012) maintains that a language attains a global status once it has gained a distinctive role in every nation-state around the globe. This special role is manifested in three ways: functioning as the mother tongue of the majority of citizens, being assigned the official status, and/or playing the role of the major foreign language. Many observers view English as the global language par excellence of the Internet, science and education, entertainment, popular culture, music, and sports. The emergence of global English is also attributable to some factors, notably the economy, military, and politics.

Historical records show that English was used in Nepal as early as the seventeenth century ( Giri 2015 ). However, English language education started formally after Janga Bahadur visited the UK during British rule in India. He knew the importance of English and started English Education in Durbar School for selected Ranas. It was the first government-run English medium school in Nepal. It was only established for the Rana family as the Ranas saw an educated person as a threat to their control ( Caddell 2007 ). The first post-secondary (higher) educational institution in Nepal was Trichandra College (1918) where the language of instruction was English. The main purpose was to shelter students of Durbar School and to stop them from going abroad (India) for further education. The underlying purpose was to prevent Nepalese from getting radical ideas that could be dangerous for them and the entire Rana regime. Tri-Chandra College was affiliated with Patna University, India. It borrowed the syllabus and assessment system from there; therefore, there was a direct influence of the British Indian Education System in the Nepalese system. Another very important reason for the spread of English was the recruitment and the retirement of the Nepalese British army. As English was mandatory for their recruitment in the British army, the youngsters willing to join the British army learned English. After their retirement, these armies returned to their homeland and inspired their younger generations to learn English. In South Asian countries, English is viewed as a language of power and as a means of economic uplift and upward social mobility ( Kachru et al. 2006 : 90). It led to the establishment of many private schools and colleges and made English indispensable to the Nepalese curriculum. Later, it became the language of attraction for all academic activities. The spread of global English as an international lingua franca intensifies socio-economic disparities both within and between speech communities. Tollefson (1995) and Pennycook (1995) explain that the promotion of English as an international language is driven by social, economic, and political forces, thereby giving rise to economic inequalities. In the same way, Canagarajah (1999) noted that generally, native speakers of English are presented with better compensation and benefits packages compared to non-natives, regardless of their academic qualifications. In Nepal, the state’s neoliberal ideology in the post-1990 era, however, has valorized the commodity value of English as a global language, creating a hierarchy of languages in which minoritized languages like Newar, Sherpa, Maithili, Tharu, Limbu, etc. remain at the bottom ( Gautam 2021 ). Following the state’s neoliberal structural reforms, a large number of private schools popularly known as ‘English medium’ and ‘boarding’ schools have been established with private investments in many parts of the country ( Sharma and Phyak 2017 : 5). The establishment of various international non-governmental organizations like the United Nations Organization (UNO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the United National Education, the Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and regional organizations like the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) have spread the use and demand of English. After the restoration of democracy in 1990, Nepal’s active participation in such organizations made English vital in Nepalese society. Although it has a sort of colonial liability, it is now accepted as an asset in the form of a national and international language representing educational and economic processes ( Kachru et al. 2006 : 90). As Kachru (2005) opines that Nepalese learners do not learn English to communicate in their homeland but they learn to talk in their work abroad. Now, this view is partially true since mostly Nepalese learn English to talk in their workplace either it can be at home or abroad. Therefore, from the time of commencement of English education, English has been learned and taught for professional development, scientific and technological knowledge, international communication, mass media, travel, and tourism. Globalization and its impact on the flourishing of English in Nepal have been very productive in recent days when the country was converted into a Federal republic state after the 2006/2007 political change. Learning English is deeply rooted among Nepalese people across the country, although the government seems reluctant to force the users to use English as a medium of instruction formally and officially ( Gautam 2021 ).

4.4.2 Language contact and shift

The present world is diversified and multilingual by nature and practice. Language contact is the common phenomenon of multilingualism where people choose their codes in their conversations and discourses. Social, historical, political, and economic power relations are major forces that influence the linguistic outcome of language contact ( Thomason and Kaufman 1992 ) as they may shape ideologies and attitudes that social actors hold toward such languages. Consequently, there is always a change in the linguistic behavior of language communities in contact which may even result in language loss due to displacement ( Sankoff 2001 ). In the context of Nepal, language contact has been the common phenomenon in Nepalese discourse of all aspects of society which is moving slowly towards code-mixing, switching, translanguaging, and the shifting from the heritage languages to the dominant and global languages.

In multilingual countries like Nepal, speakers tend to switch back and forth between two languages (or more) in different situations, formal and informal contexts, and even within the same conversation. People may code switch for various reasons. They sometimes shift within the same domain or social situation depending on the audience. A speaker might code switch to indicate group membership and similar ethnicity with the addressee. The linguistic situation of Nepal is very complex since people in their daily lives often use their respective mother tongues, Nepali, Hindi, and English within the same conversation ( Milroy and Muysken 1995 ). Language practices are inherently political in so far as they are among the ways individuals have at their disposal of gaining access to the production, distribution, and consumption of symbolic and material resources, that is, in so far as language forms part of the process of power ( Heller 1995 : 161) which we can easily observe and experience in Nepal. Code-switching in Nepal is shifting towards Nepali and English among the minority and other language communities ( Gautam 2019b ) as a mark of modernization, high socioeconomic position, and identity with a certain type of elite group; and in stylistic terms, it marks what may be termed as “deliberate” style. A marker of “modernization” or civilization is the impact of western music and culture in Nepal ( Gautam 2021 : 20). Dr. Thakur says “Our political leaders speak multiple languages in different places to collect the emotional feelings of the speakers attached with their mother tongues. Many Madhesi politicians speak Hindi, Maithili, and Bhojpuri in Terai and Nepali in Kathmandu”. This indicates that language contact and shift have also been the center of Nepalese politics for collecting votes to win the election.

4.4.3 Christianity and neoliberal impact