The 20 Best Business Plan Competitions to Get Funding

Business plan competitions can provide valuable feedback on your business idea or startup business plan template , in addition to providing an opportunity for funding for your business. This article will discuss what business planning competitions are, how to find them, and list the 20 most important business planning competitions.

On This Page:

What is a Business Plan Competition?

How do i find business plan competitions, 20 popular business plan competitions, tips for winning business plan competitions, other helpful business plan articles & templates.

A business plan competition is a contest between startup, early-stage, and/or growing businesses. The goal of the business plan competition is for participants to develop and submit an original idea or complete their existing business plan based on specific guidelines provided by the organization running the contest.

Companies are judged according to set criteria including creativity, feasibility, execution, and the quality of your business plan.

A quick Google search will lead you to several websites that list business planning competitions.

Each site has a different way of organizing the business planning competitions it lists, so you’ll need to spend some time looking through each website to find opportunities that are relevant for your type of business or industry.

Finish Your Business Plan Today!

Below we’ve highlighted 20 of these popular competitions, the requirements and how to find additional information. The following list is not exhaustive; however, these popular competitions are great places to start if you’re looking for a business competition.

Rice Business Plan Competition

The Rice University Business Plan Competition is designed to help collegiate entrepreneurs by offering a real-world platform on which to present their businesses to investors, receive coaching, network with the entrepreneurial ecosystem, fine-tune their entrepreneurship plan, and learn what it takes to launch a successful business.

Who is Eligible?

Initial eligibility requirements include teams and/or entrepreneurs that:

- are student-driven, student-created and/or student-managed

- include at least two current student founders or management team members, and at least one is a current graduate degree-seeking student

- are from a college or university anywhere in the world

- have not raised more than $250,000 in equity capital

- have not generated revenue of more than $100,000 in any 12-month period

- are seeking funding or capital

- have a potentially viable investment opportunity

You can find additional eligibility information on their website.

Where is the Competition Held?

The Rice Business Plan Competition is hosted in Houston, TX at Rice University, the Jones Graduate School of Business.

What Can You Win?

In 2021, $1.6 Million in investment, cash prizes, and in-kind prizes was awarded to the teams competing.

This two-part milestone grant funding program and pitch competition is designed to assist students with measurable goals in launching their enterprises.

Teams must be made up of at least one student from an institution of higher education in Utah and fulfill all of the following requirements:

- The founding student must be registered for a minimum of nine (9) credit hours during the semester they are participating. The credit hours must be taken as a matriculated, admitted, and degree-seeking student.

- A representative from your team must engage in each stage of Get Seeded (application process, pre-pitch, and final pitch)

- There are no restrictions regarding other team members; however, we suggest building a balanced team with a strong combination of finance, marketing, engineering, and technology skills.

- The funds awarded must be used to advance the idea.

The business plan competition will be hosted in Salt Lake City, UT at the Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute at the University of Utah.

There are two grants opportunities:

- Microgrant up to $500

- Seed Grant for $501 – $1,500

Global Student Entrepreneur Awards

The Global Student Entrepreneur Awards is a worldwide business plan competition for students from all majors. The GSEA aims to empower talented young people from around the world, inspire them to create and shape business ventures, encourage entrepreneurship in higher education, and support the next generation of global leaders.

- You must be enrolled for the current academic year in a university/college as an undergraduate or graduate student at the time of application. Full-time enrollment is not required; part-time enrollment is acceptable.

- You must be the owner, founder, or controlling shareholder of your student business. Each company can be represented by only one owner/co-founder – studentpreneur.

- Your student business must have been in operation for at least six consecutive months prior to the application.

- Your business must have generated US $500 or received US $1000 in investments at the time of application.

- You should not have been one of the final round competitors from any previous year’s competition.

- The age cap for participation is 30 years of age.

You can find additional eligibility information on their website.

Regional competitions are held in various locations worldwide over several months throughout the school year. The top four teams then compete for cash prizes during finals week at the Goldman Sachs headquarters in New York City.

At the Global Finals, students compete for a total prize package of $50,000 in cash and first place receives $25,000. All travel and lodging expenses are also covered. Second place gets US $10,000, while third place earns US $5,000. Additional prizes are handed out at the Global Finals for Social Impact, Innovation, and Lessons from the Edge.

Finish Your Business Plan in 1 Day!

The collegiate entrepreneurs organization business plan competition.

The Collegiate Entrepreneurs Organization Business Plan Competition (COEBPC) exists to help early-stage entrepreneurs develop their business skills, build entrepreneurial networks, and learn more about how they can transform ideas into reality. It also offers cash prizes to reward entrepreneurship, provide an opportunity for recognition of top student entrepreneurs around the world, and provide unique opportunities for networking.

To compete, you must:

- Be a currently enrolled student at an accredited institution

- Have a viable business concept or be the creator of an existing business that generates revenue.

If you are among the top three finalists of the business plan competition and successfully receive prize money, you will be required to submit a class schedule under your name for the current academic semester. Failure to do so will result in the forfeit of the prize money.

All competitions are held online. The finalist will receive a trip to the International Career Development Conference, where they have an opportunity to win additional prizes from CEO’s sponsors.

- First Place – $7,000

- Second Place – $5,000

- Third Place – $3,000

- People’s Choice Award – Collegiate Entrepreneur of the Year – $600

MIT 100k Business Plan Competition and Expo

The MIT 100K was created in 2010 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to foster entrepreneurship and innovation on campus and around the world. Consists of three distinct and increasingly intensive competitions throughout the school year: PITCH, ACCELERATE, and LAUNCH.

- Submissions may be entered by individuals or teams.

- Each team may enter one idea.

- Each team must have at least one currently registered MIT student; if you are submitting as an individual, you must be a currently registered MIT student.

- Entries must be the original work of entrants.

- Teams must disclose any funding already received at the time of registration.

Hosted in Cambridge, MA at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology beginning in October through May of each academic year.

Top finalists will have a chance to pitch their ideas to a panel of judges at a live event for the chance to win the $5,000 Grand Prize or the $2,000 Audience Choice Award.

20 Finalists are paired with industry-specific business professionals for mentorship and business planning and a $1,000 budget for marketing and/or business development expenses.

The 10 Top Finalists participate in the Showcase and compete for the $10,000 Audience Choice Award while the 3 Top Finalists automatically advance to LAUNCH semi-finals.

The grand prize winner receives a cash prize of $100,000 and the runner-up receives $25,000.

Florida Atlantic University (FAU) Business Plan Competition

The FAU business plan competition is open to all undergraduate and graduate student entrepreneurs. The competition covers topics in the areas of information technology, entrepreneurship, finance, marketing, operations management, etc.

All undergraduate and graduate students are eligible to participate.

The business plan competition will be held at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, Florida.

- First prize: $5,000 cash

- Second prize: $500 cash

Network of International Business Schools (NIBS) Business Plan Competition

The Network of International Business Schools (NIBS) Business Plan Competition is designed to offer an opportunity to develop your business plan with the guidance of industry experts. It provides the opportunity for you to compete against fellow entrepreneurs and explore big ideas.

- Participants must be the legal age to enter into contracts in the country of residence.

- Participants may not be employed by an organization other than their own company or business that they are launching for this competition.

- The plan should be for a new business, not an acquisition of another company.

The Network of International Business Schools (NIBS) Business Plan Competition is held in the USA.

There is a cash prize for first, second, and third place. There is also a potential for a business incubator opportunity, which would provide facilities and assistance to the winners of the competition.

Washington State University Business Plan Competition

The Washington State University Business Plan Competition has been serving students since 1979. The competition is a great opportunity for someone who is looking to get their business off the ground by gaining invaluable knowledge of running a successful business. It offers a wide range of topics and competition styles.

- Any college undergraduate, graduate, or professional degree-seeking student at Washington State University

- The company must be an early-stage venture with less than $250,000 in annual gross sales revenue.

The Washington State University Business Plan Competition is held in the Associated Students Inc. Building on the Washington State University campus which is located in Pullman, Washington.

There are a wide variety of prizes that could be won at the Washington State University Business Plan Competition. This is because the business plan competition has been serving students for over 30 years and as such, they have offered more than one type of competition. The common prize though is $1,000 which is awarded to the winner of each class. There are also awards for those who come in second place, third place, etc.

Milken-Penn GSE Education Business Plan Competition

The Milken-Penn GSE Education Business Plan Competition is one of the most well-known competitions in the country. They have partnered with many prestigious institutions to provide funding, mentorship, and expertise for the competition.

Education ventures with innovative solutions to educational inequity from around the world are encouraged to apply, especially those ventures founded by and serving individuals from marginalized and historically underrepresented communities.

We encourage applicants working in every conceivable educational setting–from early childhood through corporate and adult training. We also welcome both nonprofit and for-profit submissions.

The competition is held at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

All finalists receive $1,000 in cash and $5,000 in Amazon Web Services promotional credits.

Next Founders Business Plan Competition

Next Founders is a competition geared towards innovative startups with a social impact, looking to transform society by addressing key global human needs. The competition inspires and identifies energetic, optimistic entrepreneurs who are committed to achieving their vision.

Next Founders is for Canadian business owners of scalable, high-growth ventures.

Next Founders is held at the University of Toronto.

You could win up to $25,000 CAD in cash funding for your new business.

Hatch Pitch Competition

The Hatch Pitch competition is one of the most prestigious business competitions in the US. The winners of the Hatch Pitch Competition are given access to mentorship courses, discounted office space with all amenities included, incubators for startups, tailored education programs, financial counseling & more.

The competition is for companies with a business idea.

- The company’s product/service must have launched within the past 2 years, or be launched within 6 months after the Hatch Pitch event.

- Founders must retain some portion of ownership in the company.

- Received less than $5 million in funding from 3rd party investors.

- The presenter must actively participate in Hatch Pitch coaching.

The Hatch Pitch Competition is located at the Entrepreneur Space in Dallas.

The grand prize for this business plan competition is access to resources like incubators and mentorships that could prove invaluable in bringing your startup company to the next level.

TechCrunch’s Startup Battlefield

The Startup Battlefield is a business plan competition that is sponsored by TechCrunch. It awards the winner $50,000. There are two different rounds to this competition:

- First Round – 15 companies from all of the applicants that submitted their business plans for this round.

- Second Round – Two finalist companies compete against each other at TechCrunch Disrupt NY’s main stage.

At the time of the application process, companies must have a functional prototype to demo to the selection committee. In selecting final contestants, we will give preference to companies that launch some part of their product or business for the first time to the public and press through our competition. Companies that are in closed beta, private beta, limited release or generally have been flying under the radar are eligible. Hardware companies can have completed crowdfunding but those funds should have been directed to an earlier product prototype. Existing companies launching new feature sets do not qualify.

TechCrunch’s Startup Battlefield is held at different locations.

The Startup Battlefield rewards the winner with $50,000. In addition, the two runner-ups get a prize of $5,000 each.

New Venture Challenge

New Venture Challenge is a competition hosted by the University of Chicago. There are 3 main categories that will be judged:

- Innovative Concept – Arguably the most important category, this focuses on uniqueness, originality, and suitability.

- Market Fit/Business Model – Are you solving an actual problem for your target market? Does your project have the potential for profit?

- Presentation – Did you make a compelling, impactful presentation? Did you clearly communicate your goals and vision to potential investors?

You can find eligibility information on their website.

The New Venture Challenge competition is held in Chicago, IL.

Finalists are awarded:

- First Place: $50,000 equity investment and access to industry mentors and other resources.

- Second place: $25,000 equity investment and access to industry mentors and other resources.

- Third place: $15,000 equity investment and access to industry mentors and other resources.

New Venture Championship

The New Venture Championship is hosted by the University of Oregon and has been since 1987. The championship brings new ventures and innovative business ideas to life and the competition offers plan writing as a service to those who need it.

The University of Oregon New Venture Championship is open to university student teams with 2-5 members that have at least one graduate student involved with their venture. Students should be enrolled in a degree program or have finished their studies in the current academic year.

The New Venture Championship hosted by the University of Oregon is held in Eugene, Oregon.

Every business plan has a chance of winning a cash prize from $3,000 to $25,000 and additional benefits like plan coaching and office space rental.

Climatech & Energy Prize @ MIT

The Climatech & Energy Prize @ MIT is a competition that focuses on companies that are involved in the area of energy, environment, and climate change.

- Participants must be a team of two or more people.

- At least 50% of formal team members identified in the competition submission documentation must be enrolled as half-time or full-time college or university students.

The Climatech & Energy Prize @ MIT is held in Cambridge, MA.

The grand prize winner receives $100,000 and other winners may receive other monetary prizes.

Baylor Business New Venture Competition

This competition has been offered by Baylor for the last 20 years. It is designed to help aspiring entrepreneurs refine business ideas, and also gain valuable insights from judges and other entrepreneurs.

Must be a current undergraduate student at Baylor University or McLennan Community College.

The Baylor Business New Venture competition will be held at the Baylor University, Waco, TX.

The grand prize winner will receive $6,000. There are also other prizes given out to the other finalists in each category which are worth $1,500 – $2,000.

13th IOT/WT Innovation World Cup

The 13th IOT/WT Innovation World Cup was organized by the 13th IOT/WT Innovation World Cup Association. It was organized to provide a platform for innovators from all over the world to showcase their innovative ideas and projects. The competition aimed at drawing the attention of investors, venture capitalists, and potential business partners to meet with representatives from different companies and organizations in order to foster innovation.

The revolutionary Internet of Things and Wearable Technologies solutions from developers, innovative startups, scale-ups, SMEs, and researchers across the world are invited to participate. Eight different categories are available: Industrial, City, Home, Agriculture, Sports, Lifestyle, and Transport.

Only those submissions that have a functional prototype/proof of concept will advance in the competition, mere ideas will not be considered.

The competition is held in Cleveland, Ohio also an important center for innovation and cutting-edge technology.

Win prizes worth over $500,000, connect with leading tech companies, speed up your development with advice from tech experts, join international conferences as a speaker or exhibitor, and become part of the worldwide IoT/WT Innovation World Cup® network.

The U.Pitch is a competition that gives you a chance to share your idea and for the community of budding entrepreneurs, startup founders, CEOs, and venture capitalists to invest in your enterprise. It also provides mentoring by experts in the field.

- Currently enrolled in an undergraduate or graduate program

- Applicants may compete with either an idea OR business currently in operation

- Applicants must be 30 years of age or under

The U.Pitch is held in San Francisco, California.

Enter to win a part of the $10,000 prize pool.

At the core of CodeLaunch is an annual seed accelerator competition between individuals and groups who have software technology startup ideas.

If your startup has raised money, your product is stable, you have customers, and revenue, you are probably not a fit for CodeLaunch.

CodeLaunch is based in St. Louis, Missouri.

The “winner” may be eligible for more seed capital and business services from some additional vendors.

New York StartUP! Business Plan Competition

The New York StartUP! is a competition sponsored by the New York Public Library to help entrepreneurs from around the world to develop their business ideas.

- You must live in Manhattan, The Bronx, or Staten Island

- Your business must be in Manhattan, The Bronx, or Staten Island

- All companies must have a big idea or business model in the startup phase and have earned less than $10,000

The New York StartUP! competition is held in New York, NY.

Two winners are chosen:

- Grand Prize – $15,000

- Runner-up – $7,500

First, determine if the competition is worth your time and money to participate.

- What is the prize money?

- Who will be on the judging panel?

- Will there be any costs associated with entering and/or presenting at the competition (e.g., travel and lodging expenses)?

Once you’ve determined the worth of the competition, then shift to focusing on the details of the competition itself.

- What are the rules of the competition?

- Are there any disqualifying factors?

- How will you be judged during the different parts of the competition?

After conducting this research, it’s best to formulate an idea or product that appeals to the judges and is something they can really get behind. Make sure you thoroughly understand the rules and what is expected from your final product. Once you know what is expected from you, you’ll be able to refine and practice your pitch to help you move through the stages of the competition.

These competitions are a fantastic method to get new business owners thinking about business possibilities, writing business plans, and dominating the competition. These contests may assist you in gaining important feedback on your business concept or plan as well as potential monetary prizes to help your business get off the ground.

How to Finish Your Business Plan in 1 Day!

Don’t you wish there was a faster, easier way to finish your business plan?

With Growthink’s Ultimate Business Plan Template you can finish your plan in just 8 hours or less!

The Art of Creating a Pitch Deck Team Slide

The Startup’s Guide to Hiring a Pitch Deck Writer

The Airbnb Pitch Deck: An Expert Breakdown

Expert Tips: How To Launch A Startup

- Business Planning

How To Win A Business Plan Contest

A well-developed business plan creates the foundation on which a successful startup will be able to establish itself, and is especially necessary when considering participation in a business plan contest or pitch event. When every factor is considered – market and industry, finance, marketing, operations, and etc. – success becomes a long-term plan as opposed to a hope for a stroke of startup luck. Along with a solid pitch and pitch deck, a business plan is a critical element in your journey to landing a successful seed funding round. Writing an investor-ready business plan can be difficult, but securing funding without a solid plan in place is pretty much impossible.

Once you finally get the perfect business plan written, what’s next? For those who are far enough along in their business, submitting the plan directly to investors might be a wise step. For those who aren’t quite ready to approach VCs yet, but could use a financial boost to get things going, participating in business plan contests can be a tremendous help. Not only do these competitions often provide significant rewards for the winners, but they also often draw the attention of angels, VCs, and even corporations looking to invest in or partner with the next billion-dollar startup.

Unfortunately, where there is honey there are bees – business plan contests often attract some of the brightest minds, and the higher the reward, the more competition you can expect. In this post, we’ll explore everything you need to know to find a great business plan contest, enter it with confidence, and win against other participating startups!

The Benefits of Winning A Business Plan Contest

Business plan competitions are beneficial platforms that allow entrepreneurs to showcase their idea, product, or startup to a group of judges. Often, these competitions involve pitching the idea or startup to judges over one or more rounds. Once each competing startup has presented, judges vote on which business (or businesses) will receive the offered reward.

While business plan competitions highly benefit winning startups, they offer immense benefits to investors who attend them also – access to early-stage businesses that they can invest in before others have the opportunity. Furthermore, these competitions work to even out the playing field for entrepreneurs who otherwise may not have access to investors – winning a business plan contest could be the difference between funding your business’ launch or failing before you even get the chance to begin.

The most obvious benefit of winning a business plan contest is winning the offered reward. The reward value of these contests can vary from small amounts to extremely large amounts. For example, the Panasci Business Plan Competition by Syracuse University offers around $35,000 in total rewards, while the Rice Business Plan Competition offers over $1.2 million in seed funding to its winners and runner-ups. Winning the right competition can impact your business greatly; providing you with the app funding required to progress your business from the app idea phase to launch and beyond. There is something that should be considered though – some business plan competitions may come with specific conditions that must be met to receive the funding; such as headquartering the business in a certain location, offering up an equity percentage, or being involved in a startup incubator for some length of time.

High-profile angels and VCs often attend larger business plan competitions, and even participants that don’t win the contest may attract the attention of an investor. In some cases, teams that don’t win may end up with larger investments than those that the judges selected for first place. Investors aren’t always looking for the same things in a startup; your idea might not be of much interest to the judges, but may be exactly what an attending investor was looking for! These investors aren’t only good for the funds they bring – some of them may provide a critical mentorship component to your startup; helping to advise your team for greater success down the line.

Lastly, one of the least recognized but most effective benefits of participating in a business plan competition is having your business plan and startup critically reviewed by experienced judges, entrepreneurs, and investors. Even if you don’t win, the insight provided by the panel of judges will offer different perspectives regarding your startup. Ultimately, by applying this insight, you can further position your startup for success when participating in future events.

Finding The Right Business Plan Contest

The unique beauty of business plan contests is that they are relatively ubiquitous – and today, more competitions are popping up than ever before. A variety of organizations, educational institutions, and even individuals organize business plan competitions to seek out investable and fundable business ideas. In general, most business plan contests can be grouped into two categories:

- University Competitions: Many major universities organize some type of business plan contest through their business school. Eligibility may vary from contest to contest, but these contests are typically only available to those connected to the business program – students, alumni, and in some cases, even on-staff professionals. Due to these eligibility requirements, competition is generally limited – which means that participants have a much larger chance of winning when compared to contests with less regulation. Furthermore, universities know that any successful startups launched through these contests will give their business program a major boost in visibility and credibility. As a result, universities often go a step above to support winners of these programs – providing additional on-campus resources or even access to alumni professionals that can help them advance their businesses.

- Sponsored Contests: Sponsored business plans are those that are planned and hosted by an organization, corporation, individual or other entity. Specifically, these organizers ‘sponsor’ the competition – organizing the event, involving investors and judges, and securing rewards to incentivize winners and participants. Sometimes, these competitions may be sponsored by companies within a specific sector such as biotech, healthcare, urban transit, architecture, and etc.; while other times they may be part of a larger startup incubator or accelerator program.

Business plan and pitch deck competitions take place several times each year in most major cities – and even in many less popular upcoming startup regions. If you are a student or alumni, check with your university to see if they have a business plan competition in place – if not, maybe you can help them organize one! For those who are not eligible to join a university-sponsored competition, a simple Google search will provide you with several options. Search for “industry name + business plan contest” or “city + business plan contest” to see what upcoming business plan contest events you may be eligible to participate in.

Winning Big At Your First Business Plan Contest

Participating in a business plan contest can be extremely valuable, but the real goal is to win – and to win big! The key to winning a business plan competition of any type is to know what the judges are looking for and to position your startup, business plan, and pitch to exceed their expectations.

Judging The Judges

In general, whether you win a business plan contest or not will hinge upon how your business idea is perceived by the panel of judges, and how they perceive you as an entrepreneur and presenter. It is worth noting that judges often come from various backgrounds with varied experiences; what may be a top consideration for one judge may make little difference to another. However, most judges compare businesses on at least the following three factors:

- Originality: Successful business ideas need to be original in nature and able to improve upon an existing solution, solve a wide-scale problem, or effectively meet the current market demand. Businesses that simply spin-off from other successful ideas are not looked upon favorably by judges or investors – since they usually have little advantage to compete against already established players. To win a business plan contest, it is essential that your idea is fresh, scalable, sustainable and eventually, profitable.

- Ability To Generate Profit: Even the most creative ideas need to be able to turn a profit at some point. Understandably, most investors aren’t interested in funding businesses that won’t provide them with a return in the long-run. In order to gain interest in your business during a contest, your business plan should show exactly how your business will provide a return for investors in the long-term. While some investors may be interested in other aspects of a business, such as their social consciousness or involvement, the majority of investors are looking for opportunities to grow their portfolio by investing in businesses that are capable of generating strong profits.

- Effective Presentation : It’s not always the best idea that wins a business plan competition. A perfect business plan and an exciting idea means very little if an entrepreneur can not properly convey their message during their presentation. In most contests, participants are given a set time limit (such as 10 minutes) to present – and expressing all the necessary information within this time period can be rather difficult. Judges look for confident entrepreneurs who can articulate their business enough to convey the efficacy and scalability of their idea properly. The knowledge an entrepreneur needs to possess doesn’t end with just the text presented in their business plan or pitch deck . Most often, there is a Q&A portion during these events in which the entrepreneur will be required to answer specific questions by judges and investors. The inability to answer these questions properly and confidently can quickly dissuade an investor from investing, or can cause a judge to give a lower score than they would have otherwise.

Preparing For Business Plan Contest Success

Success at these events is often linked to how well an entrepreneur has prepared themselves beforehand. One thing is certain – your competitors will be prepared; and if you aren’t, it will be embarrassingly noticeable. Unfortunately, in a business plan contest, there is no way to mask unpreparedness, especially among an audience of experienced entrepreneurs and investors. To best prepare for an upcoming business plan competition, consider the following tips:

- Sell A Strong Team: There is one thing that’s more important than having a great business plan – having a strong and experienced team that can actually execute it. Management teams are what bind all the elements of a business plan together; combining the skills necessary to put the plan into action successfully. It is vital that your team encompasses a broad range of skills and that each team member has a specific job that will lead to the startup’s success.

- Present The Problem First : Startups that win (in contests and in general) are those that truly solve an existing problem – whether the problem is shared by a mass group of people, or by a niche audience. There’s a lot of “cool tech” out there, but even simple ideas can solve major problems. Taxis have existed for decades, but a simple idea like ride-sharing changed the way the world views personal transportation. Prepare a pitch that is challenge/solution heavy by focusing on what the problem is, why individuals experience the issue, why current solutions don’t solve the challenges effectively, and why your product/service is the right solution for the problem.

- Know Your Funding Requirements : Investors don’t want their funds to just sit in an account; they want to know that there is a plan in place to use these funds and effectively scale a startup from its current position. Have a funding plan in place – know how much funding is required, what actions need to be completed to successfully progress the business, and how each dollar will be spent to meet your launch or growth objectives.

- Be The Expert : If there is any gap in your business plan, it will be uncovered during the Q&A stage. Investors and judges are highly experienced in asking the right questions to get a full picture of your startup and to gauge whether you are well-informed about your business, market and the issue that you are attempting to solve. It’s not a good sign when an investor or judge knows more about your business than you do. Ensure that your business plan is all-encompassing with vital information, and that you can answer any necessary questions without needing to reference your business plan. During the Q&A session, you should be able to answer questions proficiently, confidently, and with enough expertise to prove that you know exactly what you are talking about.

- Listen, Learn and Apply : You can’t win every business plan or pitch contest, but you can definitely take the insights given during one competition and use it to propel your potential for success in future contests. It’s not everyday that you’re able to receive critical feedback from a group of investors, and when you can, you should take advantage of it as much as possible. Even if you don’t win anything in a business plan competition, the insights gained can be used to catapult your business to the next level.

Writing A Business Plan That Wins

Even if everything else is perfect – if you want to win, you must begin with a well-thought-out, perfectly articulated, and investor-ready business plan that tells your startup’s story in an effective manner. There are many factors to consider when writing a business plan from proper market analysis to financial projections – and any weak point in your plan will decrease your chances of winning. If you need more advice on writing a business plan, contact one of our experts today for a free business plan consultation!

You may also like

What Is The Best Business Plan Format?

The 5 Best Kickstarter Alternatives for App Startups

What Is Seed Money and Is Your Startup Ready for It?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Enter a Search Term

Rice Business Plan Competition

Congrats Grand Prize Winner: Protein Pints

Showcasing The Best University Startups from Around the US and the World | April 4-6, 2024 | Rice University, Houston, Texas

The competition, entering its 24th year, gives collegiate entrepreneurs real-world experience to pitch their startups, enhance their business strategy and learn what it takes to launch a successful company. Hosted and organized by the Rice Alliance for Technology and Entrepreneurship —which is Rice University's internationally-recognized initiative devoted to the support of entrepreneurship—and Rice Business . Over 23 years it has grown from nine teams competing for $10,000 in prize money in 2001, to 42 teams from around the world competing for more than $1 million in cash and prizes. It is the largest and richest student startup competition in the world.

Congrats to the Winners of the 2024 RBPC

Shaping the future.

Congrats to the winners

Read About the Prizes

Watch 2024 Elevator Pitches and Final Round

Stay up to date with rbpc 2024, funding. mentorship. connections..

Billion In funding raised by startups

Still in business or with successful exits

Jobs created

Explore the Rice Business Plan Competition

Get involved, explore the judge network, learn more about the $1.5 million in prizes, hear about successful rbpc competitors, meet our alumni—the 2022 competitors.

The RBPC is unique in its stature, size, format, participants—and especially, our judges. RBPC judges act as (and often are) early-stage investors, evaluating startups investment potential.

In total, more than $1.3 million in investment, cash and in-kind prizes was awarded to the teams at the 2020 Rice Business Plan Competition—with seven teams winning $100,000 or more in prizes.

From our first startup going public to IPOs, grants and more than $4.6 in funding, our startups are progressing and achieving success.

The 2022 competition provided the mentorship, guidance and access to capital that RBPC is known for and brought everyone back together on campus at Rice University! Check out the startups for the 2022 competition.

Featured Sponsors

Follow Along with #RBPC24

- Business Plan Competitions – Rice University & Others With Large Prize Pools

B-School Search

For the 2023-2024 academic year, we have 118 schools in our BSchools.org database and those that advertise with us are labeled “sponsor”. When you click on a sponsoring school or program, or fill out a form to request information from a sponsoring school, we may earn a commission. View our advertising disclosure for more details.

To help finance an MBA degree that now costs more than $200,000 at some of the best private business schools, future entrepreneurs could do what most MBA students typically do: apply for scholarships or take out student loans—or, they could enter a business plan competition.

In April 2019, two teams from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University won combined prizes from Rice University’s business plan competition that totaled over $500,000. Incredibly, neither of Kellogg’s two teams—one a neurology medical device startup firm and the other a coffee vendor—won the competition. That honor went to a team from Minnesota’s Mitchell Hamline School of Law who walked away with an even larger award for their innovation in helicopter safety: almost $700,000.

What’s even more interesting is that large prize pools for business plan competitions for student startups appear to be increasingly common, including the Hult Prize, the Hello Tomorrow Global Challenge, the International Business Model Competition, the Baylor New Venture Competition, and perhaps the most lucrative: the Rice University Business Plan Competition (RBPC).

The Rice Business Plan Competition: A Money Machine for Student Startups?

So just what is this competition, anyway? According to Rice University, the Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC) amounts to “the world’s richest and largest graduate-level student startup competition.” The event began 19 years ago as a joint initiative between the university’s Jones Graduate School of Business, the Brown School of Engineering, and the Wiess School of Natural Sciences, along with the school’s sponsored projects office. That year, in 2001, only nine teams competed for a paltry $10,000 prize pool.

Times have certainly changed for the RBPC. In 2013, another Northwestern University team that enhanced rechargeable lithium batteries took home almost 100 times that much —$1,000,000—after winning first-place honors. In the most recent 2019 event, the total prize pool amounted to a record $2.9 million, with the top seven finalists winning $355,000 on average and none of these teams receiving less than $100,000.

The RBPC appears to owe many of its larger awards in recent years to a single investor organization. A major sponsor of the competition is the oddly-named GOOSE Society of Texas; the acronym stands for “Grand Order of Successful Entrepreneurs.” Started by Jack Gill—the principal behind Vanguard Ventures, one of Silicon Valley’s first early-stage venture capital firms—this investor network funded $1,275,000 (or about 44 percent of the event’s awards) in 2019.

But the GOOSE gravy train doesn’t necessarily stop at the awards banquet. The network’s executive director, Samantha Lewis, told Houston’s online business magazine InnovationMap that the GOOSE Society may invest more after wrapping up their due diligence investigations . For example, the RBPC’s 2017 winning team from Carnegie Mellon University received a $300,000 GOOSE grand prize during the awards ceremony, but eventually netted $2 million from the network overall.

What is the RBPC’s Track Record in Creating Successful Companies?

Are the RBPC’s contestants mainly student projects or do these ventures live on as successful companies? Clearly, most of these teams experience considerable success long after the competition.

This interesting infographic summarizes the track record of the RBPC’s success stories. It illustrates how about 60 percent of the teams transformed into companies that raised about $2.36 billion in capital. Of the 239 successful firms, 197 continue to operate and 32 firms successfully “exited,” meaning they were acquired or conducted successful initial public offerings (IPOs). The value of these exits amounts to over $1.18 billion.

The chart also shows how two industries (tech innovation and life sciences) have the highest percentages of successful firms, with the life sciences and energy industries accounting for most of the funding.

These success stories are also geographically diverse. RBPC’s alumni teams represent 162 universities from 36 U.S. states and 18 nations on six continents. And despite the way that startups cluster in Western states like California and Washington, only three universities dominate the awards: Pennsylvania’s Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Role of Angel Investors as Judges and Donors

Traditionally, as this classic Harvard Business Review article points out, the venture capital industry has not provided the earliest seed funding to startups . Instead, angel investors typically invest in startups at the earliest stages, long before venture capital firms. Sometimes referenced by names like “angel funders,” “business angels,” or “seed investors,” angel investors often tend to be high net-worth individuals and families , sometimes with personal connections to the entrepreneurs they fund. They typically inject capital into startup firms in exchange for convertible debt —loans that can be converted to stock—or a proportion of the stock in the startup company.

For example, in 1977 former Intel electrical engineer Mike Markkula helped launch Apple with arguably the best investment of any angel in history. According to Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak , Markkula provided $250,000 to Wozniak and Steve Jobs. Of that sum, only $80,000 was an equity investment and the balance was a loan. In exchange, Markkula received a third of the company’s stock as the third employee, ran the company as CEO from 1981 to 1983, and served as chairman of the board from 1985 to 1997.

So-called “super angel” investor networks such as the GOOSE Society represent a blend between venture capital firms and angel investors. Here is how Fast Company described this newer breed of firms:

These crafty interlopers represent a hybrid between the two investing models that have long ruled the normally placid world of startup funding. Super angels raise funds like venture capitalists but invest early like angels and in sums between the two, on average from $250,000 to $500,000. By being smaller, faster, and less demanding of entrepreneurs than VCs, super angels are getting first dibs on the best new ideas.

So it’s not surprising that at RBPC’s 2018 competition, 40 percent of judges were angel or super angel investors . That’s more than double the proportion of judges from the venture capital industry and triple the proportion from the next highest sector: legal and financial services. It’s also not surprising that—barring some notable exceptions like Cisco Systems, NASA, and the Texas Medical Center—angel investors donated most of the largest prizes.

Other Business Plan Competitions With Large Prize Pools

Although our research disclosed no other competitions with prize pools quite as substantial as the RBMC’s nearly $3 million, we did find several events offering prizes large enough to provide compelling incentives for starving graduate students. Here are a few examples:

The objective behind the Hult Prize is to “launch a start-up enterprise that can radically change the world and breed the next generation of social entrepreneurs.” The prize is known for the involvement of the United Nations and President Bill Clinton, who presents awards to recipients. The top prize is $1 million for the winner.

Hello Tomorrow Global Challenge

The focus in the Hello Tomorrow Global Challenge , a Paris-based competition, encompasses launching “deep tech” emerging technology ventures with funding requirements far greater than cloud- or mobile-based Web applications. The current prize pool is about $235,000.

International Business Model Competition

The IBMC isn’t a business plan competition, per se. Technically, it’s a business model competition, which means that startup teams must adhere to lean startup methodologies and organize their pitches using a lean canvas framework. This Utah-based event offered a 2019 prize pool of $200,000. ( Learn more from our article about how the lean canvas approach provides an alternative to traditional business plans.)

Baylor New Venture Competition

Another Texas-based event, Baylor University’s New Venture Competition only offers about $100,000 in cash prizes. However, IBM has kicked in $120,000 in cloud credits for each of the top three finalists, making this competition especially attractive for cloud-based technology startups.

Douglas Mark

While a partner in a San Francisco marketing and design firm, for over 20 years Douglas Mark wrote online and print content for the world’s biggest brands , including United Airlines, Union Bank, Ziff Davis, Sebastiani, and AT&T. Since his first magazine article appeared in MacUser in 1995, he’s also written on finance and graduate business education in addition to mobile online devices, apps, and technology. Doug graduated in the top 1 percent of his class with a business administration degree from the University of Illinois and studied computer science at Stanford University.

Related Programs

- 1 AACSB-Accredited Online MBA Programs 1">

Related FAQs

- 1 How Do I Become a Certified Business Process Professional (CBPP)?

- 2 How Do I Get into Business School?

- 3 How Do I Secure an MBA Internship?

- 4 How Much Do Online MBA Programs Cost?

- 5 What Can I Do with an MBA Degree?

- 6 What are MBA Program Yield Management and Yield Protection?

- 7 What are MBA Yield Comparisons, Connotations, and Stakeholders?

Related Posts

Guide to mba scholarships for 2024.

Given that higher education has now become the second-largest expense for an individual in their lifetime, only topped by buying a home, it’s no wonder why so many students now look to scholarships and fellowships for help. Fortunately, research compiled for our profiles below revealed many scholarships that can help defray the cost of earning an MBA.

Guide to MBA Careers – Business Administration Career Paths

Over the last couple of years, the technology industry has begun to chip away at the share of MBA graduates joining the finance world, and more specifically, investment banking. Some studies even suggest that tech has already, or soon will, become the top recruiter of MBA graduates.

Online MBA Programs Ranked by Affordability (2023-2024)

These online programs ranked by affordability can be a viable alternative to more expensive programs while still receiving an excellent education and providing the flexibility working professionals need to balance work, family, and higher education demands.

List of MBA Associations and Organizations (2024)

Students should not limit themselves by relying exclusively on their school’s clubs for networking opportunities. Compelling arguments exist for joining local chapters of global, national, and regional professional organizations while students are still in business school.

MBA Salary Guide: Starting Salaries & Highest Paying MBA Concentrations (2023)

Specializations amount to critical choices in an MBA student’s career. They permit students to immediately deliver highly marketable skills to an employer upon graduation, the value for which most employers will gladly pay handsome salaries.

List of MBA Conferences for 2023-2024

MBA fairs are all about personal connections. School gatekeepers travel to these events to meet well-qualified applicants. Moreover, the savviest candidates understand that connecting in a personal way with a school's admissions team can award those applicants with their most critical advantage in the admissions process: a great lasting impression.

Harvard Professor Sues University for Defamation Over Misconduct Allegations

A superstar Harvard Business School professor accused of research misconduct has filed a defamation lawsuit against Harvard University, the school’s dean, and the three blog authors who levied the allegations. Tenured faculty member Dr. Francesca Gino—a famous leadership expert and author of two books plus more than 100 scholarly research papers—filed the suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts on August 2 after HBS had placed her on administrative leave.

Advertisement

Business plan competitions and nascent entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review and research agenda

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2023

- Volume 19 , pages 863–895, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Léo-Paul Dana ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0806-1911 1 , 2 ,

- Edoardo Crocco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9797-3962 3 ,

- Francesca Culasso ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8357-1914 3 &

- Elisa Giacosa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0445-3176 3

3652 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Business plan competitions (BPCs) are opportunities for nascent entrepreneurs to showcase their business ideas and obtain resources to fund their entrepreneurial future. They are also an important tool for policymakers and higher education institutions to stimulate entrepreneurial activity and support new entrepreneurial ventures from conceptual and financial standpoints. Academic research has kept pace with the rising interest in BPCs over the past decades, especially regarding their implications for entrepreneurial education. Literature on BPCs has grown slowly but steadily over the years, offering important insights that entrepreneurship scholars must collectively evaluate to inform theory and practice. Yet, no attempt has been made to perform a systematic review and synthesis of BPC literature. Therefore, to highlight emerging trends and draw pathways to future research, the authors adopted a systematic approach to synthesize the literature on BPCs. The authors performed a systematic literature review on 58 articles on BPCs. Several themes emerge from the BPC literature, including BPCs investigated as prime opportunities to develop entrepreneurial education, the effects of BPC participation on future entrepreneurial activity, and several attempts to frame an ideal BPC blueprint for future contests. However, several research gaps emerge, especially regarding the lack of theoretical underpinnings in the literature stream and the predominance of exploratory research. This paper provides guidance for practice by presenting a roadmap for future research on BPCs drawing from the sample reviewed. From a theoretical perspective, the study offers several prompts for further research on the topic through a concept map and a structured research agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Trends and patterns in entrepreneurial action research: a bibliometric overview and research agenda

Lancaster University

Re-thinking university spin-off: a critical literature review and a research agenda.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Business plan competitions (BPCs) give nascent entrepreneurs the chance to present their business ideas to an industry and investment peer group tasked with judging each project and picking the most viable one (Overall et al., 2018 ). Winners are awarded various prizes (McGowan & Cooper, 2008 ). The purpose of BPCs is to stimulate new entrepreneurial activity and support novel entrepreneurial ideas (Kwong et al., 2012 ). In return, BPC organizers emphasize the benefits of participating, such as cash prizes and financing (McGowan & Cooper, 2008 ), visibility and reputational benefits (Parente et al., 2015 ), networking with other aspiring entrepreneurs (Thomas et al., 2014 ), and meeting potential stakeholders, including customers and investors (Passaro et al., 2020 ).

BPCs have been used by new entrepreneurs to kickstart their business ideas (Cant, 2018 ). They have been popular throughout the years, especially during the global recession in the first decade of the 2000s. BPCs have become widely popular across both developed (Licha & Brem, 2018 ) and developing countries (Efobi & Orkoh, 2018 ; McKenzie & Sansone, 2019 ), as poor economic conditions have driven young entrepreneurs toward any opportunity they can find (Cant, 2018 ). Since the origin of BPCs in the USA in the 1980s (Buono, 2000 ), several universities have implemented them in their educational ecosystem to foster practical learning. From there, BPCs have rapidly spread in Europe (Riviezzo et al., 2012 ) and within developing nations in Asia (Wong, 2011 ) and Africa (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011 ). Despite contextual peculiarities, the significance of BPCs is equally pertinent for developed and emerging economies (Tipu, 2018 ), as they contribute to shaping a lively local entrepreneurial fabric (Barbini et al., 2021 ).

Opportunities arising from BPC participation come in various forms, including knowledge (Barbini et al., 2021 ), networking, and promotion (Cant, 2016a ); however, finding economic resources to finance entrepreneurial ventures has proven to be the main concern (Kwong et al., 2012 ; McGowan & Cooper, 2008 ). BPCs are attractive to entrepreneurs, as they can be prime opportunities not only to receive feedback on their ideas, but also to get the monetary funds needed to realize them (Mosey et al., 2012 ). In addition, a successful BPC does not merely identify the most intriguing business idea but also supports entrepreneurs during the early stages of their new ventures, whether or not they win the competition (Watson et al., 2015 ).

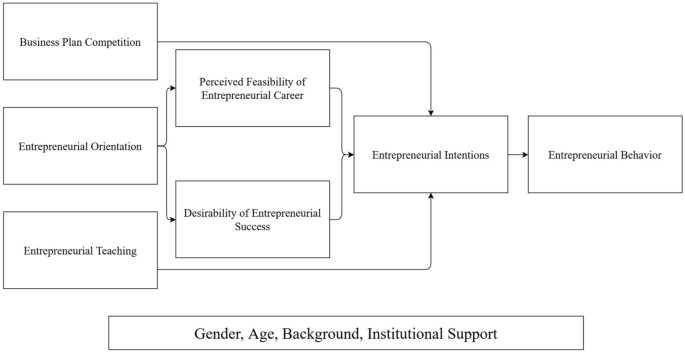

Several research streams have emerged around the topic of BPCs (Cant, 2018 ). For example, entrepreneurial education has been investigated in several studies (Licha & Brem, 2018 ; Olokundun et al., 2017 ) as a way to effectively provide learning support to nascent entrepreneurs and boost their chances of success. Moreover, university-based BPCs are being explored in terms of their potential as learning experiences and how specific lessons learned during these competitions may affect future entrepreneurial orientations (Overall et al., 2018 ). For example, some argue that promoting sustainable production during BPCs has a tangible impact on the integration of sustainability practices into future business activities (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020 ).

Start-up competitions have gained global prominence since the 1980s (Kraus & Schwarz, 2007 ; Ross & Byrd, 2011 ). Today, they are a popular form of support for nascent entrepreneurs (Dee et al., 2015 ), featuring steady growth in numbers over recent years (Fichter & Tiemann, 2020 ). Consistent with BPCs’ importance, the literature examining them is growing, with an increasing number of empirical studies published each year. However, despite the attention from policymakers and academics, no attempts have been made thus far to review the literature on BPCs systematically. Additionally, there is a need for a structured research agenda that could shed light on currently unexplored topics in entrepreneurship research, such as the role of institutions in emergent entrepreneurial intentions (Audretsch et al., 2022 ; Barbini et al., 2021 ), contextual factors stimulating nascent entrepreneurial intentions (Zhu et al., 2022 ), and the development of richer theory about practical entrepreneurial training (Clingingsmith et al., 2022 ).

To the best of our knowledge, the only previous attempt at synthesizing BPC literature was performed by Tipu ( 2018 ). While their contribution is of absolute importance, its scope was limited to 22 papers published in the early 2000s and late 90 s, thus leaving a consistent portion of recent academic literature unexplored. Consequently, we believe that a systematic review of the BPC literature could be of interest to both practitioners and academics. Building on previous systematic literature reviews (SLRs) from the entrepreneurship field, we aim to provide a detailed analysis of the relevant literature on BPCs. We focus on several key aspects of BPCs that emerged from the analysis, starting with the ways in which they are currently implemented, the benefits they provide to new entrepreneurs, and the role played by BPC promotion in the early stages of the entrepreneurial life cycle (Cant, 2016a ). Our analysis reveals several factors that influence the successful implementation of BPCs as ways to boost the effectiveness of novel entrepreneurial ventures, including entrepreneurial education for individuals who take part in the program (McGowan & Cooper, 2008 ) and entrepreneurs’ personal traits and dispositions (Kwong et al., 2012 ). Therefore, our study is not limited to a synthesis of the existing literature on the topic; rather, it develops a comprehensive framework for both professionals and academic researchers to guide future projects on BPCs. This study is guided by four main research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What is the current research profile of BPC literature?

RQ2: What are the key emerging topics to be found in BPC literature?

RQ3: What research gaps are currently present in the BPC literature and what future research agenda can be set according to said gaps?

RQ4: Can a comprehensive conceptual framework be synthesized from the literature to help academics, practitioners, and other relevant stakeholders?

Drawing on previous SLR research on entrepreneurship (Kraus et al., 2020 ), we synthesized the literature to reach our research goal and answer the questions listed above. RQ1 was addressed by gathering all the available literature that satisfied the inclusion criteria in terms of research scope, relevance, and keywords. The research profile was then obtained by conducting several descriptive observations meant to understand the volume of annual scientific production, the most cited sources, the geographical focus, the theoretical frameworks used by the authors, and the emerging themes across the sample. RQ2 was addressed by reviewing the literature presented in the sample through in-depth content analysis techniques. From the analysis, the following themes emerged across the sample: (1) BPCs as opportunities for entrepreneurial education, (2) the role of BPCs in the promotion and visibility of nascent entrepreneurs, (3) the contexts surrounding BPCs, and (4) methodological choices and research design in BPC publications. Regarding RQ3, we manually reviewed each document to identify relevant research gaps in the BPC literature. This allowed us to suggest several research questions that could serve as a foundation for future studies. Finally, RQ4 was addressed by developing a framework that synthesized the thematic findings of our SLR.

The present SLR can contribute significantly to both theory and practice. Overall, SLRs critically assess and synthesize extant research, developing a comprehensive theoretical framework that can guide scholars and practitioners. In other words, a systematic review highlights the different thematic areas of prior research, delineates the research profile of the existing literature, identifies research gaps, projects possible avenues for future research, and develops a synthesized research framework on the topic (Dhir et al., 2020 ). Thus, from a theoretical perspective, our study should interest a broad range of researchers, as it links back to the ongoing global conversation regarding BPCs. It does so by synthesizing the knowledge on the topic and formulating a structured research agenda that could serve as a reference for researchers to conduct future studies and address issues of topical interest that have yet to receive sufficient attention from authors. The research agenda is built upon extant gaps found in our in-depth analysis of the sample. Similarly, practitioners can use the findings to recognize the drivers and outcomes of BPC programs and shed light on their core characteristics when designing one. Likewise, policymakers should use the present work as a blueprint for BPC planning, as the findings presented in this paper summarize how to set up a BPC effectively.

The article begins by outlining the scope of the research and explaining what types of studies will be included in the SLR in terms of content. We then explain the methodology used to gather the research sample and provide a descriptive overview of the data. Next, we provide a thematic review of the studies featured in the SLR. We identify gaps in the literature and avenues for further research before finally discussing the study’s limitations, as well as its theoretical and practical implications.

Scope of the review

Specifying the scope of the SLR and outlining its conceptual boundaries enhance the search protocol's transparency and academic rigor (Dhir et al., 2020 ). We achieved the above by clearly defining the theoretical background of the phenomenon under investigation, thus establishing the definition of the term BPC and employing it as the conceptual boundary of the review.

The BPC literature is part of a broader stream of competition-based learning in higher education institutions (Connell, 2013 ; Olssen & Peters, 2005 ). The peculiarities of BPCs consist in the presence of rewards for participation (Brentnall et al., 2018 ), the development of core entrepreneurial competencies (Arranz et al., 2017 ; Florin et al., 2007 ), and the overall effectiveness in terms of entrepreneurial survival (Jones & Jones, 2011 ; Russell et al., 2008 ). Previous research has focused on the core elements of BPC programs, such as mentoring, feedback, and networking; the way they affect future entrepreneurial lives (McGowan & Cooper, 2008 ; Watson et al., 2015 ; Watson & McGowan, 2019 ); and the rewards from BPC participation (Russell et al., 2008 ).

From a geographical perspective, the significance of BPCs is equally pertinent for developed and emerging economies (Tipu, 2018 ), albeit nascent entrepreneurs face unique challenges in developing countries, such as the lack of educational support (Hyder & Lussier, 2016 ) and institutional instability (Farashahi & Hafsi, 2009 ). We find the most significant levels of literary production in the USA (Buono, 2000 ), where BPCs originated back in the 1980s, and Europe (Riviezzo et al., 2012 ). BPC programs are also gaining traction in developing countries, especially in Asia (Wong, 2011 ) and Africa (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011 ). In China, for instance, BPCs are recognized as a reasonable means to obtain practical entrepreneurial knowledge (Fayolle, 2013 ). Similarly, in Kenya, there is an unprecedented level of interest in BPCs, especially from stakeholders involved in entrepreneurial education (Mboha, 2018 ). Finally, in Australia, Lu et al. ( 2018 ) noted the importance of funding from the federal government, such as the New Colombo Plan or the Endeavour Mobility funding schemes, in terms of support and promotion of BPC programs.

Despite the broad geographical scope of BPC literature, there is still a considerable paucity of research on the impact of BPCs on local entrepreneurship and enterprise development. Additionally, the few published studies feature mixed results. For instance, the study by Russell et al. ( 2008 ) reported a positive impact of the MI50K Entrepreneurship Competition in terms of job creation and overall funding obtained. However, the results of the study by Fayolle and Klandt ( 2006 ) are contradictory, as they note how entrepreneurial training via BPC participation does not always equate to a successful future venture. In this regard, BPC literature echoes decades-old controversial stances in entrepreneurship research, such as the perceived usefulness of business plans (Gumpert, 2003 ; Leadbeater & Oakley, 2001 ).

At this juncture, we also consider it prudent to formulate the definition of BPC that will be used as a conceptual boundary for the present study. While BPCs worldwide share a core definition and essence, they come in various forms (McKenzie, 2017 ). We adopted Passaro et al.'s ( 2017 ) definition of BPC, highlighting three essential structural and procedural features. The first is the presence of an organizing committee overseeing the competition and sponsors willing to invest in the most promising entries (Bell, 2010 ). Second, the participants are required to submit business plans to participate in the competition, and participants often consist of teams, as knowledge sharing across multiple people is deemed a crucial component of entrepreneurial success (Weisz et al., 2010 ). Third, after an initial screening, only participants with the most promising ideas are asked to further develop their business plans in the final stages of the competition (Burton, 2020 ). Thus, with the above conceptual scope in mind, our study includes contributions that have examined BPCs, their core characteristics, their implications for entrepreneurship education, and both the antecedents and consequences of BPC participation. However, we do not include studies investigating entrepreneurship education, universities' incubators, and generic entrepreneurial themes. Such studies have already been discussed at length by previous researchers.

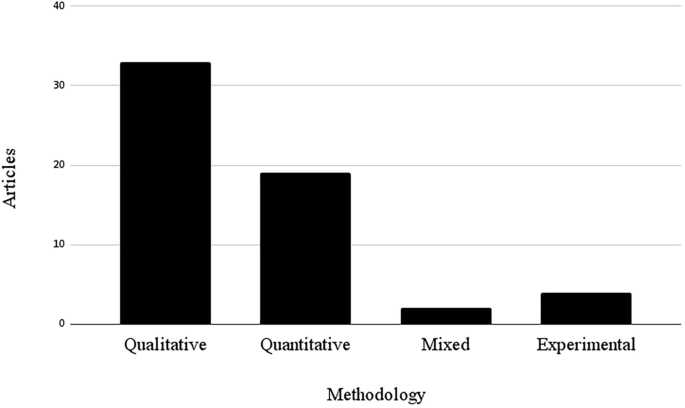

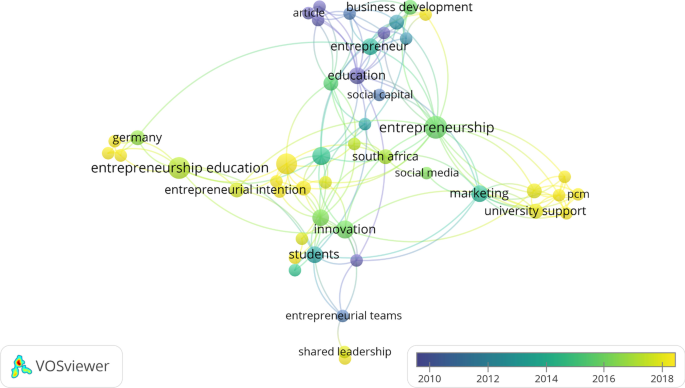

The SLR approach was undertaken in an attempt to present the current literature in a comprehensive and extensive way. SLRs have been widely used in entrepreneurship research, and we use previously published SLRs as a methodological reference to guide our study (Mary George et al., 2016 ; Paek & Lee, 2018 ; Tabares et al., 2021 ). In accordance with previous work (Hu & Hughes, 2020 ), we performed a systematic review of BPC literature divided into two distinct steps. We first extracted the dataset required to perform the study, in what we will refer to as the data extraction phase. We later profiled the sample obtained in terms of descriptive statistics, such as annual scientific production, most cited countries, authors’ networks, and collaborations. Additional analyses were conducted by using the VOSviewer software tool (version 1.6.10., Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands) and Microsoft Excel (Dhir et al., 2020 ). The tools make use of bibliographic data to determine the frequencies of the published materials, design relevant charts and graphs, construct and visualize the bibliometric networks, and calculate the citation metrics.

Data extraction

The three central databases utilized for the present study are Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and Google Scholar, as per the suggestions by Mariani et al. ( 2018 ). The first step in order to conduct the extraction of data was to identify the appropriate set of keywords. Based on the conceptual boundaries of the SLR, we determined an initial set of keywords. The keywords included ‘business plan competitions', ‘business plan contests’, and ‘business creation competitions’. The above keywords were used to perform an initial search on Google Scholar to examine if our keywords were sufficient. The first 50 results were taken into consideration (Dhir et al., 2020 ). We also searched the exact keywords in top journals, such as Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice ; Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal ; International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal ; and Entrepreneurship Research Journal . Subsequently, we updated the list with keywords from the above sources. We consulted the panel to finalize the set of keywords, which ultimately resulted in the following: business plan competition*, business creation competition*, social business plan competition*, business plan contest*, business creation competition*, pitch competition*, pitch contest*. Data were collected from two databases, Scopus and WoS, which are generally well renowned in previous SLR studies on entrepreneurship (Hu & Hughes, 2020 ). Then, a rigorous set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was established. As for the inclusion criterion, we wanted to include only peer-reviewed works. This decision was made to strengthen the validity of the findings. Consequently, all forms of literature that may not have been subjected to a rigorous review process were excluded. This exclusion criterion thus filtered out conference proceedings, book chapters, editorials, websites, and magazine articles from the sample. The English language was used as an additional inclusion criterion to avoid language bias (Dhir et al., 2020 ). A complete list of the inclusion/exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1 .

Data collection and screening of literature

The search for keywords, abstract, and title was done in selected databases using the search string featured in Table 2 . An initial search in Scopus attained 195 distinct records, including full-length articles, book chapters, conferences proceedings, review articles, and research notes. We filtered out three publications written in languages other than English. Further, after manually reviewing each record, we excluded 36 publications that were not related to BPCs and 29 publications other than peer-reviewed journal articles. This step allowed us to reduce the overall number to 76 unique records. The same research protocol was performed on the WoS database and provided an initial total of 68 records, all of which were published in English. We filtered out 24 records as they were conference proceedings, review articles, book chapters, or meeting abstracts. Subsequently, we merged the two collections and removed any duplicate records we found in the process. As a final step, we performed chain referencing to identify further relevant studies that were not found in the previous steps. We then reviewed each publication title to identify and exclude journals that could be referred to as gray literature. This brought the total number of publications to 58, which we agreed to as the definitive number to be considered for the SLR. While somewhat limited, the final sample size is in line with the standards set for management studies (Hiebl, 2021 ) and previously published SLRs in entrepreneurship research (Paek & Lee, 2018 ; Poggesi et al., 2020 ).

Research profiling

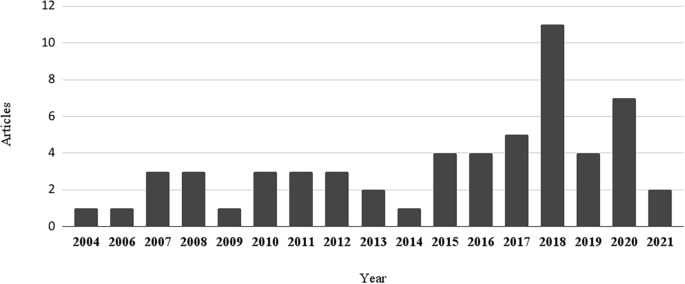

Research profiling allowed us to review the sample in terms of several descriptive statistics meant to give us a comprehensive understanding of the current state of the art of BPC research (Dhir et al., 2020 ). Starting with Fig. 1 , we address the annual scientific production of papers included in the sample. Data suggest how BPC literature has been steady over the past two decades, with a sharp increase in recent years. The year 2018 features a significant spike in publications, with 11 distinct records to consider. These trends are in line with the consistent growth in broader entrepreneurship literature, as policymakers have shown increasing levels of interest in BPCs as effective means to create new jobs, foster innovation, and recover from economic crisis (Barbini et al., 2021 ).

Year of publication of the selected studies

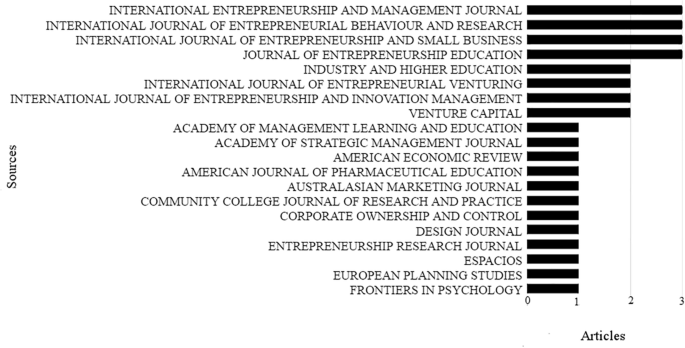

Figure 2 shows the distribution of articles throughout the various sources included in the sample. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal , International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research , Journal of Entrepreneurship Education , and International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business rank at the top.

Journals publishing the selected studies

In terms of publishing outlets, the variety of journals publishing relevant research on BPC further highlights the increasing attention scholars have devoted to this domain. Through a closer analysis, we note how leading entrepreneurship journals feature most of research articles on BPCs, thus testifying the intersection between the BPC stream and entrepreneurial education literature.

Establishments examined by the selected studies

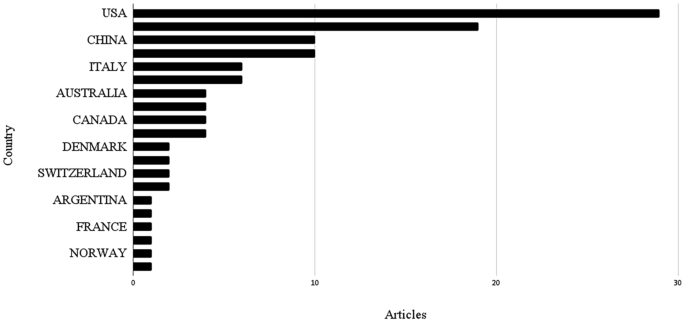

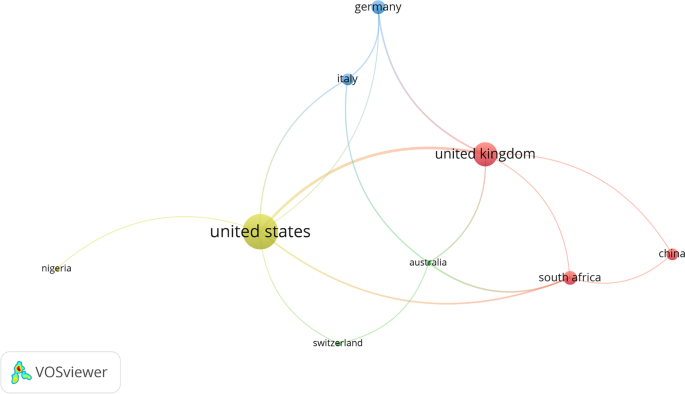

The examination of the geographic scope of the prior studies is featured in Fig. 3 and it suggests that the majority focused on a single country, with most conducted in the United States. The United Kingdom, China, and Germany also feature a significant number of publications in terms of corresponding authors’ nationality. Other countries include South Africa, Australia, Canada, Italy, Switzerland, Argentina, Brazil, France, Nigeria, and Venezuela. The above results corroborate extant research, as it sees the USA as predominant due to them being where BPC first originated (Buono, 2000 ), thus having a more prosperous and profound history. Consistently with previous research, we also find a solid scientific presence in Europe (Riviezzo et al., 2012 ; Waldmann et al., 2010 ) and China (Fayolle, 2013 ). However, developing countries are lagging, possibly because BPCs have only recently become popular there (House-Soremenkun & Falola, 2011 ).

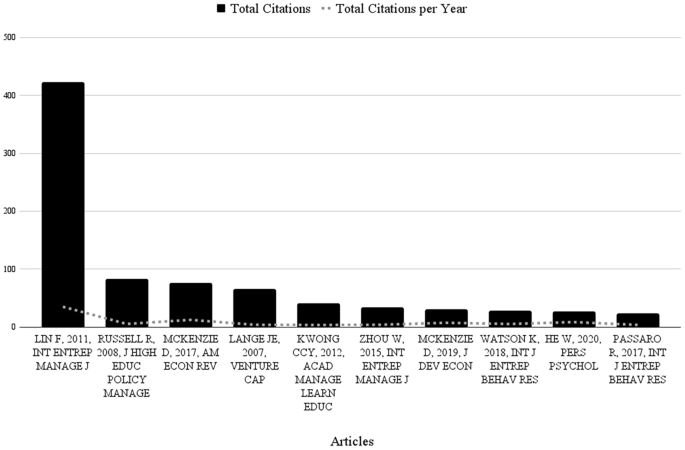

Figure 4 illustrates the top 10 most cited publications. The three most cited papers were published over a decade ago, thus acting as a theoretical foundation for development of the literature stream. More specifically, the work of Liñán et al. ( 2011 ) on factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels and education is the most cited. In their work, Liñán et al. ( 2011 ) consider and establish empathy as a necessary precursor to social entrepreneurial intentions. At the time of publication, their findings were exploratory in nature, thus prompting several additional studies to expand upon their results and further develop their conclusions.

Most cited global documents

Furthermore, the study by Russell et al. ( 2008 ) on the development of entrepreneurial skills and knowledge by higher education institutions ranks at second place. Russell et al. ( 2008 ) noted that BPCs provide fertile ground for new business start-ups and for encouraging entrepreneurial ideas. Russell et al. ( 2008 ) were among the first to suggest a positive correlation between BPCs and entrepreneurial development, thus becoming a theoretical cornerstone for studies willing to further explore the benefits of BPCs for nascent entrepreneurs (Passaro et al., 2017 ).

The study by Lange et al. ( 2007 ) is the third most cited work. Lange et al. ( 2007 ) supported the hypothesis that new ventures created with a written business plan do not outperform new ventures that did not have a written business plan. Their work is often cited among BPC literature when discussing theoretical assumptions against the effectiveness of business plans and, consequently, BPCs (Watson & McGowan, 2019 ).