On the Sabarmati riverfront: Urban planning as totalitarian governance in Ahmedabad, Gujarat – An article in EPW

Does the dominant discourse of “good governance” account for issues of poverty and inequity or does it exclude the poor from being seen as a category relevant to the goals of efficient governance institutions? What connects professional urban planning to the politics of governing urban populations and spaces characterised by poverty?

Highlighted here are the roles played by the architectural consultancy, city administrators and political managers, as well as community groups, civil society and academic institutions. The efficiency of the administration showed an active anti-poor stance in the court proceedings and in the violence of actual evictions and post-eviction suffering. The evidence presented here also shows how "world-class" urban planning has facilitated yet another blatant instance of "accumulation by dispossession" via the flow of the Sabarmati.

Apart from the violent demolition of their homes, evictions from habitations that provided access to livelihoods, schooling, social and physical security and public health services, the tens of thousands of urban working poor residents of the Sabarmati riverbank settlements experienced a traumatizing and stigmatising change in their relationship with society’s dominant sociopolitical institutions.

Having looked at the execution of the Sabarmati Riverfront project, especially through the lenses of the vast numbers of riverbank residents and the conversion of the riverfront to an elite recreation space, the paper highlights how non-state actors facilitate predatory and totalitarian state functioning in the context of an electoral democratic framework.

The riverfront project as it unfolds today is itself a totalitarian modernist planning project, treating (riverbank) space as devoid of the cultural, social, economic and political elements, through which the urban working poor negotiates its place in the city. Reduced to calculation friendly units, working class families become pieces on a social engineering chessboard. Fitted into uniform boxes, they tick the state’s requirement to provide “mass, scalable solutions”.

The planner whose grandiose designs were intended to create an urban imaginary layered with fantasies of western cities and amenities for the global tourist, and local and diasporic elites, has played an important role in the valorisation of riverbank space in distinct ways. Moreover, the idea that the river has been “disrespected” till the riverfront project came along, casts the riverbank residents as not worthy of “being around the river”, as it were.

Indirectly, the language used to characterize the problem to which the riverfront project is the solution frames the riverbank residents as unworthy and illegitimate users of the river. High value uses, and a commodified publicness are attributed to the upper income groups in Ahmedabad, positioning them as moral superiors. There emerges a very strong moral perspective in the planner’s vision, where the river is too valuable to be left to people who exhibit traits that are “uncivilised”. The riverfront project is what would bring civility and a higher moral order to their existence.

The paper states that according to Mahadevia (2011), the newest paradigm in urban governance is one of deliberate confusion, not only in terms of the policy pressures that favour selected groups of elites but also often overlay the discourse of social inclusion as a justification for schemes that claim to address issues of the poor. In the larger context of urban transformation where the JNNURM has had a major role to play, the process of planning was instituted on the premise that the poor were to be viewed as dependents of the state from the very start, or in the words of Mahadevia, “as beneficiaries or objects of change and thereby at the mercy of the official stakeholders, experts and the urban local body officials”. In Mahadevia’s view, “the urban story so far has been one of big visions and elite capture, bordering on scam, through a predatory local state in cahoots with crony capitalists”.

Adding to Mahadevia’s characterisation of the new urbanization story as a “paradigm of confusion”, where both anti-poor and pro-poor discourses and practices collide much to the detriment of the poor, is Scott’s (2010) “project of rule”, whereby it is necessary for the (neo-liberal) state to gain dominance in the public sphere by seeking “to bring non-state spaces and people to heel”.

His conception applies to “[G]overnments whether colonial or independent, communist or liberal, populist or authoritarian” and their “headlong pursuit of this end by regimes otherwise starkly different suggests that such projects of administrative economic and cultural standardisation are hard-wired into the administrative architecture of the modern state itself” (Scott, 2010). A paradigm of modernist urban planning such as the EPC design of a revitalised riverfront, must necessarily “include” the myriad activities and people carrying them out on the riverbank; one of its key goals was to create “legibility and enumeration” using the coercive bureaucratic structures of the state itself.

The problematisations to which the riverfront project is offered as the solution articulate the river as a non-place (Baviskar 2011, drawing on Auge 2008), even while it was inhabited by hundreds of thousands of working people and their families. As the Yamuna’s thriving cultural and social worlds were invisible to the rest of Delhi (Baviskar 2011), the Sabarmati’s million microcosms were actively made invisible under the barrage of colourful propaganda in the form of brochures, full-page colour spreads in daily newspapers like the Times of India, coffee-table books, glamorous exhibitions funded by New York-based institutions, advertising hoardings selling dreams of riverfront luxury, and public relations films aimed at the international investor.

Drawing on bourgeois environmentalist sentiments, the 10-year campaign waged by the urban planner, local authority, and corporate media encouraged social hostility against the poor, especially those living around the riverbank of the Sabarmati, who now appeared to the rest of the city as the obstacle in the city’s “development”, and its achievement of global aspirations (Baviskar 2011).

Through the demolitions and evictions campaigns, the complete evacuation of the riverfront provided a “blank slate” to the planners, who would now transfer their prior inscribed “planned” geometric lines from paper to the ground. The experiences of hunger, malnutrition, loss of livelihood, loss of life and loss of the will to live were some of the benefits first experienced by

Ahmedabad’s working poor who lived on the riverbank by the grand urban vision of the riverfront development project. It almost seemed like “planning for rehabilitation” had never been a priority or even a mandate for the urban planner. The focus had been on creating an abstract imaginary through modernist planning tools and techniques, not shaping a process of engagement with the everyday lives of hundreds of thousands of the city’s working poor who bore the brunt of such misshapen imaginations.

In the imagination of the planners, the river appears as an assemblage of tubes and pipes with commodified openings for leisure and entertainment, not as seasonal ecological systems with floodplains as an integral part of its flows (Baviskar, 2011).

The floods downstream and even within the city were ignored as if they were caused by some external factor, other than attempts to “pinch the river” (Bimal Patel, quoted in D’Monte 2011). The arrogance of modernism rises to the surface when “respect for the river” is imagined as forcing it into hydraulic calculations, which the river itself seldom obeys, as illustrated by the floods in Ahmedabad, downstream in Dholka, or even in Delhi, Mumbai and New Orleans where ecological water systems were actively ignored (Baviskar 2011).

The role of efficient administrators was highlighted in their active antipoor stance in the court proceedings and the violence of actual evictions and post-eviction suffering. The evidence presented here shows how the role of the world-class urban planner has been to actively facilitate yet another blatant instance of “accumulation by dispossession” via the flow of the Sabarmati.

- Street Food

- Pub & Disc

- Health Care

- Home Essentials

- Medical Store

- Where to Travel in Indore

- Nearby Destinations

- Fun & Entertainment

Indore is all set to get a city-centric riverfront on ‘forgotten’ river Kahn!

- Facebook Twitter Google Plus Pinterest Email Copy Link

After Ahmedabad and Lucknow, Indore is set to clean its inline city stream Kahn that turned into a sewage line, and develop its city centered riversides as a dedicated River Front. For more information on this, do read the whole story.

River Front: A need or a deed?

Before informing anything about the development of River Front on Kahn, anything that comes in mind is that “What is the need of developing a river front in such an intense area with loads of traffic and frustration due to it?, why not broaden roads to reduce traffic?”

Well, the public is priority, If seen logically, there are several requirements!

Indore is the cleanest city in India as per Swatchata Sarvekshan. But anyone who passes through Rajwada, which is the most central region of Indore, gets to know that the inline river of Indore – Kahn, which is no more than a sewage stream now. Rapid industrialization and growth exploits natural resources up to a great extent, which is a serious issue.

What it would be like if you have a clean peripheral city, A1 waste management, class 1 roads, public toilets all over the city, but still the central river is polluted like a dumping ground in the middle of a palace. That is the primary reason for developing a river front. Rivers are treated as Mother in India as river’s sustain life and maintains the habitat of the place, and they should not be polluted anymore.

“Indore cannot get decorated with the cleanest city status until the Kahn river is reinstated.”

Other Prospects of having a river front:

There are many advantages of having a river front:

- If seen from tourism point of view, it would be a must visit place for tourists as well as localized as the city loves the Rajwada Fort, and will surely visits its banks if clean and lushy to watch.

- If thinking socially, it would be the city’s pride as a only few metro’s have a dedicated river front and will set an example before everyone to “get in the mess and start cleansing the surroundings instead of just criticizing.”

- If seen strategically, apart from being just a tourist place, it would be a new location for Indorians, and will create market revenue as well as opportunities, like in Lucknow and Ahmedabad, which had a market’s nearby a river front, thus, the visitors uplifts their mood in the river front and visits nearby market as well.

- If taken Psychologically, it will reduce agitation and frustration of people due to busy and tensed roads which initiates a chain reaction of mood uplift, which definitely affects the market.

What lead to the degradation of Kahn river?

Indore being the largest and most populous city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh is the commercial capital for exchange of goods and services, and recently many big and small scale industries have set up their operations in the city. Since the mid-19th century, Indore has seen rapid industrial and population growth, which no doubt increased sewerage flow in the Kaahn River, affecting the condition of the river drastically. More than 100 industrial units have been polluting Kahn river since decades. Also, setting up of slum area’s beside the river has affected the perquisite habitat which is hard to change now. But after so long, the Indore Municipal Corporation has taken a significant and determined decision to clean and rejuvenate the stream and develop a riverfront on it, which is appreciable.

Project description:

The Indore Municipal Corporation (IMC) has started riverfront development work of Kahn River which is a key initiative of the city in making Indore a Smart City. The first phase of development of riverfront would be done from Rambagh Bridge to Krishnapura. In the second stage, the stretch from Jawahar Marg to Gangaur Ghat is planned for renovation. The scope of the work includes:

- Construction of retaining walls and dredging of riverbed along 3.9 km of riverfront

- Development of landscaping and open spaces

- Development of City-level recreational space

- Development of Fruits & Vegetables Market to accommodate shops/ hawkers in the area

- Development of adequate parking areas

Benefits to Indore:

Once the construction works are completed, the following are benefits are expected:

- Restoration/ visual improvement of the riverfront

- Preventing entry of sewerage into the river

- Creation of a city-level recreational area

- The enhanced opportunity of the riverfront for tourism purpose

“This data is provided by The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, this is only tentative data available, actual parameters may change afterward.”

After the riverfront develops completely, it can be said that no major unclean stuff is left to be considered for rejuvenation in the City. Ultimately “Cleanliness is next to Godliness.”

We should make our Indore; divine as much that, it becomes God’s own city.

You may also like

Little Yogis: Kids-friendly Yoga Workshop for a Healthier Generation!

Having a smartphone is not enough now, be really smart, cyber security issues, you need to know!

Subscribe us on youtube.

Follow us on Twitter

- Lost Your Password

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- DC vs RR Live Score

- HP Board Result 2024 Live

- Lok Sabha Election 2024

- Election Schedule 2024

- DC vs RR Live

- IPL 2024 Schedule

- IPL Points Table

- IPL Purple Cap

- IPL Orange Cap

- The Interview

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

Riverfront development plan: After PM launches the project, MVA forms panel to examine it

The announcement came after nationalist congress party (ncp) chief sharad pawar met the state authorities regarding the project.

PUNE Days after Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled Pune Municipal Corporation’s (PMC) ambitious riverfront development project on March 6, the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) government has ordered a committee to review it. The state government on Saturday ordered an inter-departmental committee “to ensure contradictions and doubts” are removed before the project starts in Pune.

The announcement came after Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) chief Sharad Pawar met the state authorities regarding the project. The meeting was attended by water resources minister Jayant Patil, tourism and environment minister Aaditya Thackeray and environmentalists.

The project, which is facing opposition from the Congress and the NCP, was supported by the latter during the PMC general body meeting.

The MVA government will hold a meeting with the irrigation department, environmentalists and other departments concerned to address the concerns which, according to activists, may result into over 80% concretisation along the river banks, barrages to block the free-flowing nature of both the rivers, Mula and Mutha, and change floodlines which might cause flooding in areas along the river banks.

After Saturday’s meeting, Thackeray, who holds the environment portfolio, tweeted, “A meeting to discuss the proposed river front development was held in the presence of @PawarSpeaksji and Minister @Jayant_R_Patilji. While everyone wants a cleaner and safer Mula-Mutha, there are some doubts raised by environmentalists and experts. An inter departmental committee has been formed to ensure that the contradictions and doubts are removed and work begins for a clean, safe rive.”

The project is one of the ambitious ones pushed by the BJP with PMC being the executing authority.

Pawar said, “The project has been undertaken for the purpose of cleaning and decontaminating Mula, Mutha and Mula-Mutha rivers in Pune, lowering the flood level of rivers, developing and beautifying the river banks, connecting the existing roads with the rivers, connecting citizens with the rivers. However, considering the objections, questions and suggestions from environmentalists, NGOs and citizens, the ambiguity created in the implementation seems to be essential for the success of the project. The environmentalist delegation also called for conservation and conservation of biodiversity while improving the river, taking care not to disrupt the food chain.”

Last week, Pawar had raised environmental concerns while pointing at a letter from the water resources department of Maharashtra. He had said the letter mentioned that the project may bring problem for the river flow and if the riverbed is reduced, it can cause floods.

During the meet, Patil suggested that a study group of experts from the department of water resources, environment, urban development and representatives of eco-friendly organisations should be appointed to consider the changes to address the course of the river, obstruction of flow and reduction of carrying capacity.

PMC’s ₹ 2,619-crore beautification project aims to make the river accessible for residents for recreational purposes, which is now limited to a few.

Thackeray suggested that any ambiguity should be removed immediately. “I am confident that the ambiguity will be removed within 15 days after the immediate appointment of the study group.” he said.

Meanwhile, PMC has already okayed handing over the Sangamwadi-Bundgarden stretch contract after the general body approved ₹ 250 crore for the plan. The civic body during 2017-2019 had also completed surveys, base map preparation and environment impact assessment for the project.

Environmentalist Sarang Yadwadkar, who has been following up on the issue since it was first proposed, said, “The riverfront development project is full of contradictions. The project says that it will not disrupt the flow of the river, but also proposes multiple barrages. It states that there would be no built-up area, but over 80% of the funds would be used for concretisation. Also, the project does not consider the over 450 million litres of untreated water which would still be released into the river even after the (Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) project. The project also revises the natural floodlines for the sake of the project which means that the areas around the river could cause flooding during monsoon. The stagnation of water would kill the river and its flora and fauna.”

‘Move only for political gain’

Terming NCP’s move as political, BJP councillor and city mayor Murlidhar Mohol said, “The river improvement project has been finalised after careful study at various levels. The important thing is that the NCP had supported the project at all levels in the past. Yet, doubts have been raised regarding the plan for political gains, especially after Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the project’s foundation stone. Puneites will notice that politics is more important to the NCP than the project which will benefit the city.”

IPL 2024 Coverage

Join Hindustan Times

Create free account and unlock exciting features like.

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

- Weather Today

- HT Newsletters

- Subscription

- Print Ad Rates

- Code of Ethics

- IPL Live Score

- T20 World Cup Schedule

- IPL 2024 Auctions

- T20 World Cup 2024

- Cricket Teams

- Cricket Players

- ICC Rankings

- Cricket Schedule

- T20 World Cup Points Table

- Other Cities

- Income Tax Calculator

- Budget 2024

- Petrol Prices

- Diesel Prices

- Silver Rate

- Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Taylor Swift: A Primer

- Telugu Cinema

- Tamil Cinema

- Board Exams

- Exam Results

- Competitive Exams

- BBA Colleges

- Engineering Colleges

- Medical Colleges

- BCA Colleges

- Medical Exams

- Engineering Exams

- Horoscope 2024

- Festive Calendar 2024

- Compatibility Calculator

- The Economist Articles

- Lok Sabha States

- Lok Sabha Parties

- Lok Sabha Candidates

- Explainer Video

- On The Record

- Vikram Chandra Daily Wrap

- EPL 2023-24

- ISL 2023-24

- Asian Games 2023

- Public Health

- Economic Policy

- International Affairs

- Climate Change

- Gender Equality

- future tech

- Daily Sudoku

- Daily Crossword

- Daily Word Jumble

- HT Friday Finance

- Explore Hindustan Times

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Subscription - Terms of Use

- HYDROVISION

- Career Center

Koteshwar: Case Study of Efficient Development in India

By R.S.T. Sai and D.V. Singh To conform to a tight construction schedule, the owner of the 400 MW Koteshwar project on the Bhagirathi River (a tributary of the Ganges River) in India scrapped many of its previous plans and used a hands-on managerial approach. This innovation enabled the plant to be commissioned ahead of schedule.

To conform to a tight construction schedule, the owner of the 400 MW Koteshwar project on the Bhagirathi River (a tributary of the Ganges River) in India scrapped many of its previous plans and used a hands-on managerial approach. This innovation enabled the plant to be commissioned ahead of schedule.

By R.S.T. Sai and D.V. Singh

In an industry often marked by slow progress and long struggles for project authorization, the 400 MW Koteshwar Hydroelectric Project in India can provide a model of effective and efficient construction and operation. First proposed in 2000, the project was under construction in early 2007. Two of the four generating units were commissioned just four years later. The progress of the facility can be credited in large part to hands-on management practices and construction methodology used by the plant’s owner, THDC India Limited.

To overcome a construction delay and finish the Koteshwar project in a timely manner, THDC implemented a unique management methodology that placed decision-making ability in the hands of a small committee and those working directly on the project. This eliminated much of the red tape that often halts hydropower development. Additionally, innovative construction techniques were used to shorten building time and make more efficient use of available resoures and manpower. Completing side-by-side construction activities simultaneously with the help of innovative organization was one method used to finish the project ahead of schedule. Many of these innovations and managerial strategies could be applied to other hydropower projects.

Project summary

The Koteshwar project is a vital component of the larger 2,400 MW Tehri Hydropower Complex, the first major attempt to harness the potential of the Ganges River.

Koteshwar is the most quickly-implemented hydro project of its type in the nation, according to sources within the Ministry of Power, which commended the project and its owners and contractors. Contractor PCL-Intertech LenHydro Consortium began construction work in April 2007, the first two units were commissioned in March 2011, and the third and fourth units were commissioned in January 2012 and March 2012, respectively.

The Koteshwar project is comprised of a 97.5 meter-high concrete gravity dam on the Bhagirathi River, a tributary of the Ganges River, and a powerhouse at the toe of the dam on the right bank that houses four 100 MW turbine-generating units. Each generator is a vertical shaft, semi-umbrella type and is coupled to a Francis turbine. The turbines, generators, transformers and balance of plant equipment were provided by Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd. of New Delhi, India.

Power generated at this plant contributes considerably to the ability of the Tehri Hydro Complex to provide a combined peak capacity of 2,400 MW to the local grid once the final phase is completed. The complex is operating at a capacity of 1,400 MW. The third component of the project, the 1,000 MW Tehri Pumped Storage Plant, is under construction and is expected to be commissioned by2017. Annual energy generation from Koteshwar is 1,155 GWh based on 90% water availability.

Water released from the Tehri Reservoir, situated 20 km upstream of Koteshwar Dam, is being regulated by the Koteshwar powerhouse for irrigation purposes. Also, the reservoir impounded by Koteshwar Dam functions as a balancing reservoir for the pumped storage plant.

Complex prevailing conditions and issues

Despite its considerably fast construction and implementation time (3.5 years as opposed to the nation’s average of six to 10 years), the Koteshwar project faced a number of complex issues that temporarily impeded progress. The innovations that enabled the project to be completed early were developed and implemented as a response to the issues faced.

Major work on the project began on August 31, 2002, when a US$66 million contract was awarded to PCL-Intertech LenHydro, with a scheduled completion date of May 31, 2006. The first river diversion milestone was achieved on December 28, 2003, only 28 days behind schedule. Thereafter, the pace of work was sluggish, largely due to the resettlement of families affected and repeated geological failures on both river banks.

The village Pendaras, where all the major structures were to be constructed, was to be completely vacated in March 2005. However, those vacating the land disturbed the construction activities by organizing sporadic agitations with various motivations, such as seeking employment with the contracting company. Officers and contractors were often man-handled and physically attacked.

Apart from this, two of the quarries being used to supply materials for the dam were in the villages of Mulani and Gairogisera. The state government relinquished control of the last one in 2007, substantially delaying construction work.

Further, soaring prices of raw materials also created a problem. For example, the price of steel started increasing, from US$547 per unit in 2007 to US$948 in 2008. As the prices increased, the project contractors did not receive adequate compensation as per the price adjustment formula in the contract agreement. The resulting cash-flow problem made it difficult for the contractor to procure materials. Additionally, payments to suppliers and for salaries were not made on time, promoting an attitude of distrust toward the project and its development team. As a result, work progressed very slowly up to February 2007, delaying all other development work past the initially scheduled completion date.

THDC management had two options: terminate the work and seek a fresh tender, or take some innovative management action to streamline the finances and resources of the contractor and get the work done through this company.

Termination was not an ideal option, as the owner would have to terminate a signed contract and risk a stay order, and progress up to that point would be lost through demobilization of the site. The project would essentially have to be restarted from scratch, creating an additional delay in completion of 18 months to two years. In addition, THDC would face a revenue loss of US$80 million per year.

Moreover, delay in completing this project would jeopardize development of the pumped-storage project, as the Koteshwar Reservoir was designed to be the lower reservoir. In addition, the delay would result in lost revenue from the Tehri plant, as it would not be able to function as a peaking station in the true sense. Currently, the Koteshwar plant fulfills the needed water requirement in the river by running one unit in base mode. If Koteshwar had not been implemented, Tehri would have to meet this need by running one unit in base mode around the clock. This means instead of getting peaking revenue, THDC would receive normal revenue. With all these factors considered, THDC management chose the second option.

Implementation of effective management

The value of work completed by the civil works contractor up to March 2007 was about US$20 million, as compared to a total contract price of US$66 million. At this stage, THDC felt that if the availability of required equipment, material and workforce could be ensured, the project could be completed within a minimal time frame by taking advantage of the resources/equipment already mobilized by the contractor. Accordingly, the THDC management board decided to carry out work at the project by “risk and cost” methodology. This meant making decisions at the site and making payments to manufacturers, suppliers, transporters and piece rate workers directly at the behest of the contractor and on that contractor’s written requests.

THDC’s management team empowered the project team with the decision-making abilities to cut short the procedural delays. The managing engineer for civil works was redesignated chief project officer (CPO) and was authorized to procure material, manpower, specialized work force and spares for maintenance of tools and equipment. He was also authorized to induct labor gangs/piece rate workers and fix their rates, if the contractor failed to do so. Finally, the CPO was authorized to set targets and directly distribute incentives to work gangs to accelerate the pace of work.

To speed progress of the project as a whole, an “empowered committee” was established in March 2007 to ensure there were plentiful resources available. The committee was comprised of the CPO and one member each from the design and engineering and corporate finance departments. Decisions made by the committee were recorded as meeting minutes and were deemed to have standing approval of the CMD (Chairman Managing Director). Such vast powers were vested with the committee to make administrative, technical and financial decisions required for bringing the project on track and to develop infrastructure so the project could be commissioned. The actions of the empowered committee drastically reduced the procedural and regulatory hang-ups that could slow progress.

Work proceeded quickly. The organizational set-up of the work site was restructured to increase efficiency. Executives with proven track records with the Tehri project were inducted into the new management team. Four independent sections were created within the civil works team, divided by the section each team would work on (dam, powerhouse, power intake and switchyard), each headed by an experienced senior manager.

All of the construction activities at site were planned and handled by THDC engineers. Incentives were distributed to the laborers directly by THDC as they achieved locally set targets. This ignited stiff competition between labor groups deployed at different locations on site, thus stimulating the pace of work. The uninterrupted cash flow and timely payment also boosted morale and confidence among contractors, workmen and suppliers and resulted in accelerated progress.

The hands-on management strategy adopted at Koteshwar was an unprecedented move in the history of Indian hydro. When the plant was commissioned, the efforts were lauded by the government of India.

Innovative construction

The unusual delay and later innovative methodology adopted for managing the project required a shift in approach toward innovative construction techniques to catch up on the tight schedule. The engineers at the project site dared to think out of the box and adopt innovative techniques to replace conventional construction methods. The empowered committee stood behind these innovations and encouraged more unique developments.

Some of the innovations used at the site are described below:

Erection of turbines using a crawler crane

Conventionally, the erection of turbine parts is achieved with the assistance of an electrical overhead traveling crane, which travels on the crane beam cast on the walls on either side of the machine hall. The same methodology was planned for Koteshwar. However, based on the project requirements, a hydraulic crawler crane with a maximum lifting capacity of 250 MT was used. The crane was kept on the downstream side of the powerhouse in the tailrace channel area.

Erection of such turbine parts as the draft tube, stay rings and spiral casings was achieved using a mobile crane while the other parts were being constructed simultaneously. Use of this mobile tower crane enabled the project to engage in both civil and electromechanical activities, saving time and setting a new precedent for efficient development.

Using trusses to support the powerhouse

The above-ground powerhouse was constructed using roller-compacted-concrete columns, walls and beam structures. Conventionally, in a surface powerhouse, the roof slab is cast after raising the walls and columns to roof level. Thereafter, scaffolding erected from ground to roof level provides support and shuttering for the slab. In such a case, erection of electromechanical equipment is delayed until the scaffolding and shuttering material can be cleared from around the units.

To construct the powerhouse and install the units simultaneously, steel trusses of 21 meter span were constructed to support the shuttering of the slab. This made the entire unit area accessible, saving four months of construction time.

Alternative approach during excavation

Excavation for the penstocks was originally planned from the downstream side of the dam near the powerhouse. The excavated muck would be dumped into the powerhouse pit for disposal. To work on both tasks simultaneously, a methodology was developed to forego the interdependence of both the structures. Initially, construction of a partition wall between the powerhouse and stilling basin was suspended in this area to enable access from the stilling basin side. Later, the partition wall was raised, leaving an opening 8 meters wide by 8 meters tall at an elevation of 529 meters for carrying out activities in the powerhouse.

Alternative approach to service bay area

The only approach to the service bay and powerhouse area was through a 376 meter-long main access tunnel, with an inlet at Elevation 570 meters on the right bank. This area of the right bank had very unsteady geology, marked by repeated slope failures. Consequently, excavation of the tunnel was delayed until June 2007.

To move forward with work despite this delay, THDC chose to take an alternative approach from the downstream side, through the tailrace channel up to the service bay area of the powerhouse. Excavation of the tailrace channel would be connected with the downstream main approach of the stilling basin.

Although the main access tunnel was not fully operational until July 2009 because of the slope failures, service bay work began in early 2008. This approach not only helped keep the project ahead of schedule and provided access for both men and materials, it also provided a means for an electrical overhead traveling crane to be transported to the service bay, where it was erected in early 2009.

Concreting of generator barrel

Concreting of the generator barrel of Unit 1 was a challenge because there was not sufficient time to complete the task conventionally. To shorten the length of time required, THDC decided the discharge ring, which was to be placed in the turbine pit after hydraulic testing of the spiral casing, would be placed after completion of the concreting, which would shave 15 to 20 days off the schedule.

For this to happen, a temporary gallery nearly 1 meter wide was left around the stay ring pedestals below the spiral casing. Once the discharge ring was lowered, concrete work around it was completed from this gallery. Meanwhile, the turbine was erected alongside this work.

As a result, concreting of the Unit 1 generator barrel was completed on September 26, 2009, in only 57 days as compared to the planned 75. This was a great achievement because this activity conventionally takes as much as five months. Nearly one month was saved as per the schedule and nearly 2.5 months if it had been completed conventionally.

Arrangement for erection of steel liners

Construction of the steel liners for the penstocks was to be carried out through the lower horizontal penstocks, but due to rock ledge failure and further delay in excavation of the lower horizontal penstocks, this could not be achieved. To facilitate the erection of penstocks from the upper side, the contractor built cement concrete buttresses between all four penstocks. The contractor also installed a track-mounted gantry crane with the rail track at Elevation 590 meters up to Penstock 4. The steel liners were constructed with the help of this arrangement, which prevented a possible construction delay.

Arrangement of canopy for simultaneous work

Conventionally, hydromechanical/electromechanical construction work is completed once the civil works have been completely finished, which takes a considerable amount of time. To save time, erection work of the electromechanical/hydromechanical equipment began after completing the civil works up to mid-level only. To do this, workers created a canopy of steel to facilitate simultaneous working.

Substantial time was saved in the construction of the power intake and draft tube gates of the powerhouse, which were ready to house gates even before completion of the civil works up to the top level.

Accelerated reservoir filling and commissioning of Units 1 and 2

A geological event occurred on December 17, 2010, above the underground diversion tunnel of the project. As a result, the excavated muck found its way into the diversion tunnel, blocking the flow of water. As soon as the blockade was noticed, all four units of the Tehri plant located upstream were immediately shut down to avoid sending any more water into the Koteshwar powerhouse.

The balance of the civil and hydromechanial works that were pre-requisites to reservoir impoundment had to be completed so that water could be passed downstream through the spillway. The diversion tunnel gate at Koteshwar was lowered on January 23, 2011, and water passed through the spillway on the 27th.

At the time of reservoir impoundment, the penstocks of Units 1 and 2 were complete; however, the penstocks of Units 3 and 4 were not connected to their spiral casings and were expected to take more time. This would delay filling the reservoir and, consequently, could have delayed commissioning of Units 1 and 2.

To allow for filling the reservoir, the water flowing through the incomplete inlet pipes of Units 3 and 4 would have to be rerouted. Leakage water was routed to a draft tube by erecting a barrier of steel plates with stiffeners inside the penstock, with pipes and gate valves to discharge the accumulated water behind the plate.

This arrangement made it possible to fill the reservoir even though the Unit 3 and 4 penstocks were not entirely complete.

Fully operational since March 2012, the Koteshwar project can be seen as a model for hydro plant development in India due to the effective management techniques that were put into practice. However, success could not have been achieved without the innovation in construction techniques mentioned above.

R.S.T. Sai is chairman and managing director and D.V. Singh is technical director and former chief project officer of the 400 MW Koteshwar project with THDC India Limited.

Related Posts

Latest Hydro Review News

Urban Design Thesis

Udl thesis publication 2023.

Curating the best thesis Globally !

Hybrid Thresholds | Saba Amini

The proposal envisions the threshold between the built urban fabric and the natural environment at the water’s edge. It focuses on the development of public

Urban Design and Development of a Public Space

This thesis uses a case study approach at the proposed Transit Hub for the City of Kitchener to focus on opportunities for a high quality

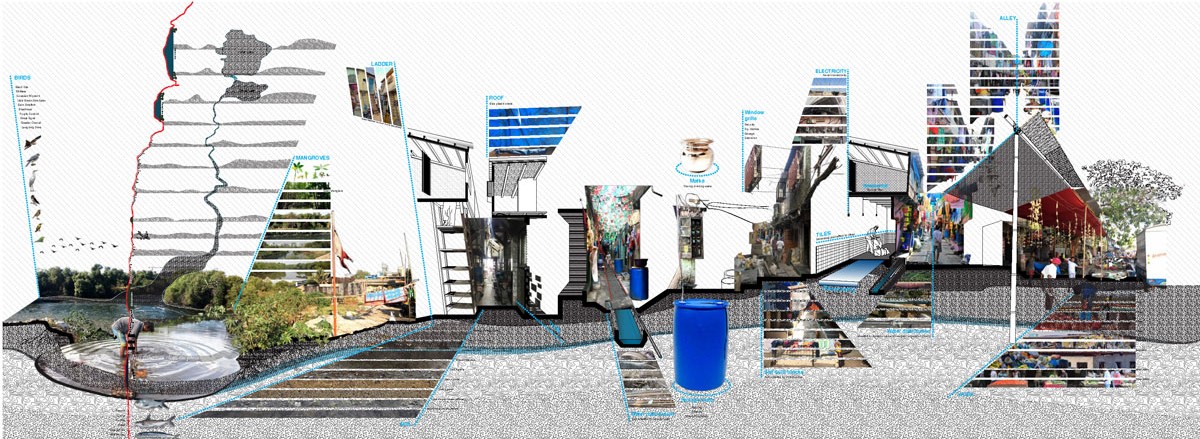

(Slum)scapes of adaptation Weak Grounds, Risk Ecologies, Community Initiatives | Harvard GSD

Rapid population growth, rural-urban migration, and the occupation of vulnerable territories are powerful characteristics for the increase of informal settlements. Largely, informal settlements have been

In the Name of Heritage: Conservation as an Agent of Differential Development, Spatial Cleansing, and Social Exclusion | Mehrauli, Delhi

I intend to study the impacts of the architectural conservation of the Qutub Minar Complex on the urban village of Mehrauli, New Delhi, because the

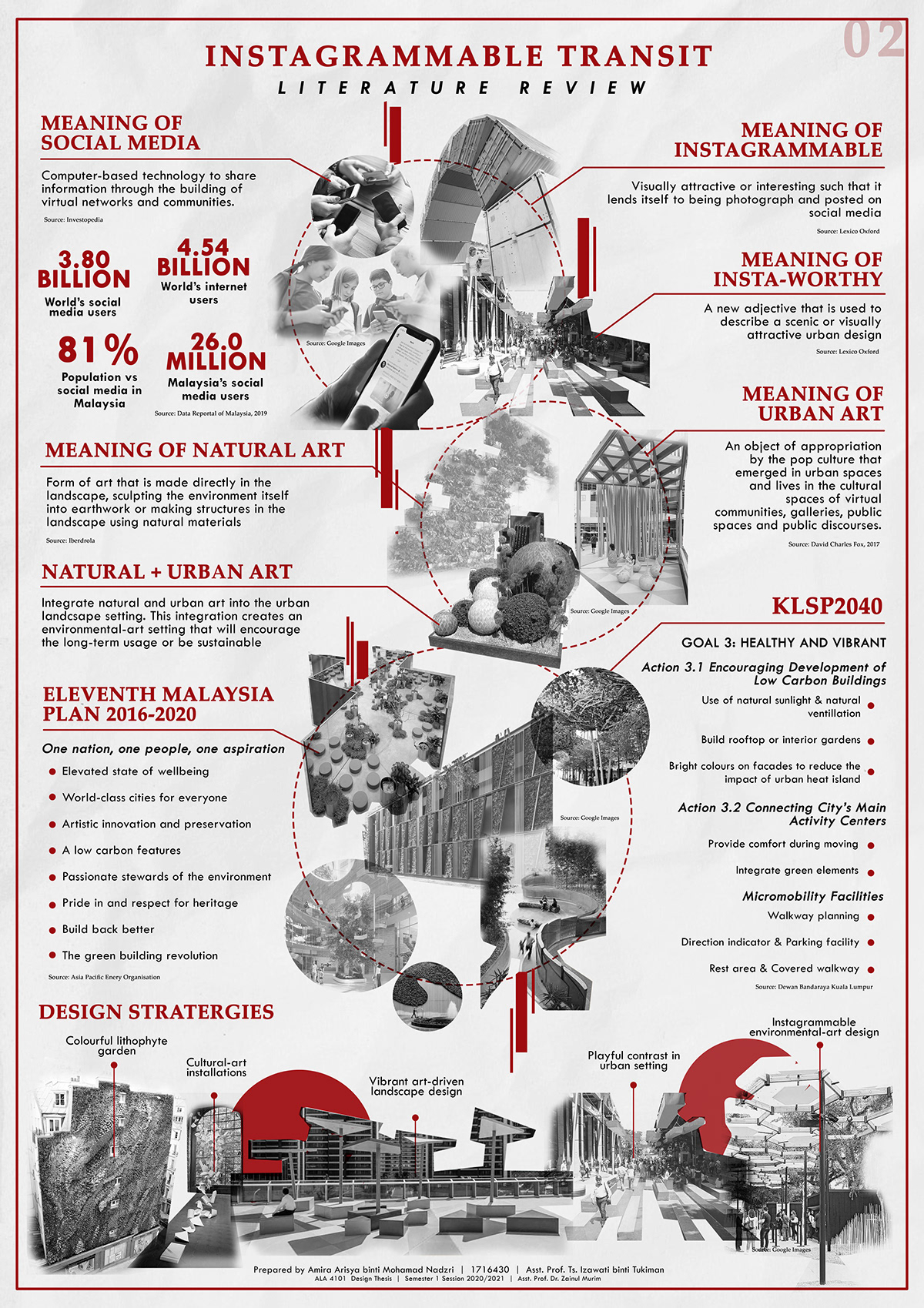

Instagramable Transit | Amira Arisya

Thesis Title: Instagramable Transit Name: Amira Arisya Program: Landscape Architecture Location: Malasia University: International Islamic University

Art Hub as a Public Space | Uneeb Ahmad

The thesis analyzes factors that hinder the communication of artists and the public and aims to conclude a way by which communication may be improved.

UDL Photoshop

Masterclass.

Decipher the secrets of

Urban Mapping and 3D Visualisation

Session Dates

4th-5th May, 2024

UDL Thesis Publication

A Comprehensive Guide

Post-thesis opportunities and resources.

Urban Design | Landscape| Planning

Join the largest social media community.

STAY UPDATED

Join our whatsapp group.

Recent Posts

Architecture Thesis Report Writing Guide

- Article Posted: May 5, 2024

Architecture Thesis Projects Inspiration 2024

- Article Posted: May 3, 2024

What Is an Urban Heat Island?

- Article Posted: March 28, 2024

What is urban Health?

Top Architecture Thesis Topics for Community Development

- Article Posted: March 26, 2024

Architecture Thesis Topics for the Digital Age

- Article Posted: March 25, 2024

15 Inspirational Riverfront Development Case Studies

Future Trends in Architecture Thesis

- Article Posted: March 24, 2024

Top Urban Design Colleges in India – 2024

- Article Posted: March 18, 2024

Career Opportunities After B.Arch

- Article Posted: March 17, 2024

Scholarships for Urban Planning Students 2024

- Article Posted: February 28, 2024

World Wetlands Day 2024 | The Ramsar Convention

- Article Posted: February 3, 2024

Sign up for our Newsletter

Please go through our Newsletter Policy

© 2019 UDL Education Pvt. Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Overview

A comprehensive guide (free e-book).

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In this paper, the case study Sabarmati riverfront at Ahmedabad is discussed. The main concern is to decrease the river pollution, protection from flood and increase the tourism. The development ...

a 'case study method' (Yin R.K. 2003; Kothari, C. 2004) involving the archival research, the field study, including observations, visual survey, and interviews to investigate the reasons for establishing the relation between the waterfront and city in case of Surat city in India. The process has been explained below in fig 4.

Journal of Geography and Regional Planning. Full Length Research Paper. Revitalization of Dravayawati River, Jaipur, India: A. water-front development project. Aman Randhawa* and Tarush Chandra ...

In this paper, the case study Sabarmati riverfront at Ahmedabad is discussed. The main concern is to decrease the river pollution, protection from flood and increase the tourism. The development ...

This document outlines strategies and guidelines for waterfront developments. It discusses the background of urban waterfront redevelopments in the 1980s. The research objectives are to produce general strategies and design guidelines for waterfront areas. Some strategic guidelines include ensuring accessibility to the waterfront, maintaining a ...

the riverfront but these projects driven more by investment need than by community or environmental needs. In addition, inadequate regulations and guidelines relating to riverfront development, is having negative impact on environment. In Lucknow there is also a proposal of riverfront development, in three different stretches along river Gomti.

The Mula-Mutha riverfront development project will be executed in 11 stretches; during the first three years, the PMC will spend ₹700 crore on the first few stretches after which the project ...

This paper by Navdeep Mathur questions whether the official narrative that presents Ahmedabad as a pioneer in urban transformation in India engages with the experiences of the urban poor in Ahmedabad by examining processes around the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project.

The first phase of development of riverfront would be done from Rambagh Bridge to Krishnapura. In the second stage, the stretch from Jawahar Marg to Gangaur Ghat is planned for renovation. The scope of the work includes: Construction of retaining walls and dredging of riverbed along 3.9 km of riverfront; Development of landscaping and open spaces

Days after PM laid the foundation stone for the ambitious riverfront development project, the MVA government has ordered a committee to review it. ... Patil suggested that a study group of experts ...

A case study of the Huangpu Riverfront in Shanghai, China. Author links open overlay panel Li ... on the right bank of the Sabarmati river, India, shown an average RCI of about 1.57 °C and 1.71 °C during ... such as wind direction, in the development of riverfront areas. Our study suggests that downwind areas can receive more cooling benefits ...

Following portfolio is a collection of work of four year undergraduate program (Bachelors of Planning) at CEPT University, Ahmedabad, India. Batch of 2012, by Shaurya Patel.

Koteshwar: Case Study of Efficient Development in India. To conform to a tight construction schedule, the owner of the 400 MW Koteshwar project on the Bhagirathi River (a tributary of the Ganges River) in India scrapped many of its previous plans and used a hands-on managerial approach. This innovation enabled the plant to be commissioned ahead ...

The main objective of this research is to investigate the main impacts of waterfront development on both urban and. social development of the city, taking the Jeddah's waterfront as a case study ...

This thesis uses a case study approach at the proposed Transit Hub for the City of Kitchener to focus on opportunities for a high quality ... 15 Inspirational Riverfront Development Case Studies. ... March 24, 2024; Top Urban Design Colleges in India - 2024. Article Posted: March 18, 2024; Career Opportunities After B.Arch. Article Posted ...

Urban Studies 48(10) 2085-2100, August 201 1 Reclaiming the City: Waterfront Development in Singapore T. C. Chang and Shirlena Huang [Paper first received, June 2009; in final form, May 2010] Abstract In its quest to be a world city, many of Singapore's urban spaces have been subjected to constant redevelopment.