- Advertise With Us

The Fight against Bullying in Indonesia

Another survey conducted by UNICEF Indonesia in 2015 revealed that as many as 50 percent of local students, aged 13 to 15, have been bullied in their schools.

I guess it is best to once again remind students, teachers and parents, who are active participants in the education system, that no matter the extent of bullying, it should never be tolerated.

Related posts

Face-to-face school in jakarta starts 30th august, students and mental health during online learning, a creative approach to uplifting lives: bringing the joy of reading and literacy to city slum kids, the fight against paediatric cancer, trans retail group launches the largest snow playground in indonesia, wyndham surabaya raises more than idr 22 million in funds for medical and frontline workers.

Understanding Bullying Cases in Indonesia

- First Online: 30 July 2022

Cite this chapter

- Ihsana Sabriani Borualogo 12 &

- Ferran Casas 13 , 14

Part of the book series: International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life ((IHQL))

397 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Bullying cases are increasing over time in Indonesia and there are a growing number of serious and fatal cases. Both school and sibling bullying happen in Indonesia. Although children reported being physically bullied more frequently by siblings than by other children at school, however studies in sibling bullying in Indonesia are still very limited. School bullying cases in Indonesia increase the numbers over years. This chapter aims to review scientific studies on bullying cases in Indonesia, including the Indonesian context of parenting style and cultural context, in order to present an overall panorama of the knowledge available and the situation that emphasises the need of improving political and social action to overcome the diverse negative effects of bullying on Indonesian boys and girls.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abubakar, A., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., Suryani, A. O., Handayani, P., & Pandia, W. S. (2015). Perceptions of parenting styles and their associations with mental health and life satisfaction among urban Indonesian adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 , 2680–2692.

Article Google Scholar

Azis, A. R. (2015). Efektivitas pelatihan asertivitas untuk meningkatkan perilaku asertif siswa korban bullying [The effectiveness of assertiveness training to increase assertive behaviour of bullying victims]. Jurnal Konseling dan Pendidikan, 3 (2), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.29210/12500

Borualogo, I. S. (2021). The role of parenting style to the feeling of adequately heard and subjective well-being in perpetrators and bullying victims. Jurnal Psikologi, 48 (1), 96–117. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.61860

Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2021a). Subjective well-being of bullied children in Indonesia. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16 (2), 753–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09778-1

Borualogo, I. S., & Casas, F. (2021b). The relationship between frequent bullying and subjective well-being in Indonesian children. Population Review, 60 (1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1353/prv.2021.0002

Borualogo, I. S., & Gumilang, E. (2019). Kasus perundungan anak di Jawa Barat: Temuan Awal Children’s Worlds Survey di Indonesia. Psympathic, 6 (1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.15575/psy.v6i1.4439

Google Scholar

Borualogo, I. S., & Van de Vijver, F. (2016). Values and migration motives in three ethnic groups in Indonesia. In C. Roland-Lévy, P. Denoux, B. Voyer, P. Boski, & W. K. Gabrenya Jr. (Eds.), Unity, diversity, and culture: Research and scholarship selected from the 22nd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology (pp. 253–260). International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology.

Borualogo, I. S., Wahyudi, H., & Kusdiyati, S. (2020a). Bullying victimisation in elementary school students in Bandung City. 2nd Social and Humaniora Research Symposium . Atlantis Press, 112–116. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.200225.024

Borualogo, I. S., Wahyudi, H., & Kusdiyati, S. (2020b). Prediktor perundungan siswa sekolah dasar [Predictors of bullying in elementary school students]. Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi Terapan, 8 (1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.22219/jipt.v8i1.9841

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22 (6), 723–742.

Casas, F. (2016). Children, adolescents and quality of life: The social sciences perspective over two decades. In F. Maggino (Ed.), A life devoted to quality of life. Festschrift in Honor of Alex C. Michalos (pp. 3–21). Springer Publisher. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20568-7_1

Chapter Google Scholar

Cummins, R. A. (2014). Understanding the well-being of children and adolescents through homeostatic theory. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frones, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective (pp. 635–662). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8

DP3AKB Jabar. (n.d.). Mengenal dan mengembangkan sekolah ramah anak [Identifying and developing child-friendly schools]. https://dp3akb.jabarprov.go.id/mengenal-dan-mengembangkan-sekolah-ramah-anak/

Eisenberg, N., Liew, J., & Pidada, S. U. (2001). The relations of parental emotional expressivity with quality of Indonesian children’s social functioning. Emotion, 1 (2), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.2.116

Febriani, H. (2020, January 8). Siswi SMP bunuh diri akibat bullying, tagar #RIPNadila ramai di twitter. [Junior high school student committed suicide due to being bullying victim, hashtag #RIPNadila was viral in twitter]. Pikiran Rakyat . https://pikiran-rakyat.com/nasional/pr-01332873/siswi-smp-bunuh-diri-akibat-bullying-tagar-ripnadila-ramai-di-twitter

Fikri, D. A. (2018, May 4). 4 kasus bullying paling menggemparkan di Indonesia, korbannya ada yang meninggal [The 4 most shocking bullying cases in Indonesia, some of the victims died]. Oke Lifestyle . https://lifestyle.okezone.com/read/2018/05/04/196/1894566/4-kasus-bullying-paling-menggemparkan-di-indonesia-korbannya-ada-yang-meninggal

French, D. C., Setiono, K., & Eddy, J. M. (1999). Bootstrapping through the cultural comparison minefield: Childhood social status and friendship in the United States and Indonesia. In W. A. Collins & B. Laursen (Eds.), Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology: Vol. 30. Relationships as developmental contexts (pp. 109–131). Erlbaum.

Hasibuan, R. L., & Wulandari, R. L. H. (2015). Efektivitas Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) untuk meningkatkan self-esteem pada siswa SMP korban bullying. [The effectiveness of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) to increase self-esteem in bullying victims of junior high school students]. Jurnal Psikologi, 11 (2), 103–110.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind . McGraw-Hill.

Koentjaraningrat. (1985). Javanese culture . Oxford University Press.

Kumara, A., & Shore, M. E. (2018). Anti-bullying research programs in kindergartens and high schools conducted at the University of Gadjah Mada (UGM), Yogyakarta, Indonesia: 2010–2017. In B. Hinitz (Ed.), Impeding bullying among young children in international group contexts . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47280-5_5

Lika, L. (2019). Pelatihan empati sebagai upaya mengurangi perilaku perundungan pada siswa SMP [Empathy training to reduce bullying behaviour in junior high school students]. Persona, 8 (2), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.30996/persona.v8i2.2365

Magnis-Suseno, F. (1997). Javanese ethics and world-view: The Javanese idea of the good life . Gramedia Pustaka utama.

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2016). TIMSS 2015 international research in mathematics . International Study Center Lynch School of Education Boston College. http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/international-results/wp-content/uploads/filebase/full%20pdfs/T15-International-Results-in-Mathematics.pdf

Olweus, D. (1997). Bully/victim problems in school: Facts and intervention. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 12 (4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03172807

Pennington, K. (2018, March 28). David Beckham tackles bullying and violence in Indonesian schools. Reuters . https://reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-education-celebrities/david-beckham-tackles-bullying-and-violence-in-indonesian-schools-idUSKBN1H4235

Rahmawati, S. W. (2016). Peran iklim sekolah terhadap perundungan. Jurnal Psikologi, 43 (2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.12480

Riany, Y. E., Meredith, P., & Cuskelly, M. (2016). Understanding the influence of traditional cultural values on Indonesian parenting. Marriage and Family Review, 53 (3), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2016.1157561

Saftiani, T., Hamiyati, H., & Rasha, R. (2018). Pengaruh tingkat konformitas teman sebaya terhadap intensitas perundungan (bullying) yang terjadi pada anak sekolah dasar [Effect of peers conformity to bullying intentions on elementary school students]. Jurnal Kesejahteraan Keluarga dan Pendidikan, 5 (2), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.21009/JKKP

Saptandari, E. W., & Adiyanti, M. G. (2013). Mengurangi bullying melalui program pelatihan “Guru Peduli”. Jurnal Psikologi, 40 (2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.22146/jpsi.6977

Schleicher, A. (2018). PISA 2018 insight and interpretation . https://oecd.org/pisa/PISA%2020%Insights%20and%20Interpretation%20FINAL%20PDF.pdf

Sheridan, S. M., Warnes, E. D., & Dowd, S. (2004). Home-school collaboration and bullying: An ecological approach to increase social competence in children and youth. In D. L. Espelage & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: A social ecological perspective on prevention and intervention (pp. 245–267). Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

Sittichai, R., & Smith, P. K. (2015). Bullying in South-East Asian countries: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23 , 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.06.002

Sumargi, A., Sofronoff, K., & Morawska, A. (2015). Understanding parenting practices and parents’ views of parenting programs: A survey among Indonesian parents residing in Indonesia and Australia. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 , 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9821-3

Tim KPAI. (2020). Sejumlah kasus bullying sudah warnai catatan masalah anak di awal 2020, begini kata Komisioner KPAI [Number of bullying cases has noted as child problems in early 2020, said the Commissioner of KPAI]. https://www.kpai.go.id/publikasi/sejumlah-kasus-bullying-sudah-warnai-catatan-masalah-anak-di-awal-2020-begini-kata-komisioner-kpai

Utami, S. H., & Frizona, V. D. (2019, July 26). Kekerasan anak masih terjadi dalam keluarga, ini imbauan Yohana Yembise [Child abuse still occurs in the family, this is Yohana Yembise’s requests]. Suara.com . https://suara.com/health/2019/07/26/173000/kekerasan-anak-masih-terjadi-dalam-keluarga-ini-imbauan-yohana-yembise

Utomo, A. J. (2012). Women as secondary earners: Gendered preferences on marriage and employment of university students in modern Indonesia. Asian Population Studies, 8 (1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2012.646841

Volk, A. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2014). What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Developmental Review, 34 (4), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.09.001

Wekoadi, G. M., Ridwan, M., & Sugiarto, A. (2018). Writing therapy terhadap penurunan cemas pada remaja korban bullying [Writing therapy reduce anxiety in bullying victims]. Jurnal Riset Kesehatan, 7 (1), 37–44. https://ejournal.poltekkes-smg.ac.id/ojs/index.php/jrk

Zevalkink, J., & Riksen-Walraven, J. M. (2001). Parenting in Indonesia: Inter- and intracultural differences in mothers’ interactions with their young children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25 , 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250042000113

Download references

Acknowledgments

Children’s Worlds Survey in Indonesia was supported by UNISBA (Universitas Islam Bandung), UNICEF Indonesia, and Statistics Indonesia (BPS). This survey was funded by UNICEF Indonesia and supported by BAPPENAS (Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning). Thanks to all enumerators who helped with data collection and to all participating schools and children.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Islam Bandung, Bandung, Indonesia

Ihsana Sabriani Borualogo

Doctoral Program on Education and Society, Faculty of Education and Social Sciences, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile

Ferran Casas

ERIDIqv Research Team, University of Girona, Girona, Spain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ihsana Sabriani Borualogo .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Laboratory of Educational Processes & Social Context (Labo-PECS), Université d’Oran 2, Oran, Algeria

Habib Tiliouine

UNICOM, School of Social Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Lomas de Zamora, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Denise Benatuil

School of Graduate Studies / Institute of Policy Studies, Lingnan University, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Maggie K. W. Lau

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Borualogo, I.S., Casas, F. (2022). Understanding Bullying Cases in Indonesia. In: Tiliouine, H., Benatuil, D., Lau, M.K.W. (eds) Handbook of Children’s Risk, Vulnerability and Quality of Life. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01783-4_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01783-4_12

Published : 30 July 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-01782-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-01783-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Geopolitics

- Environment

Bullying in Indonesia

In this file photo Indonesian celebrities hold a peace protest in Jakarta to encourage people to stop bullying against children. (Adek Berry / AFP Photo)

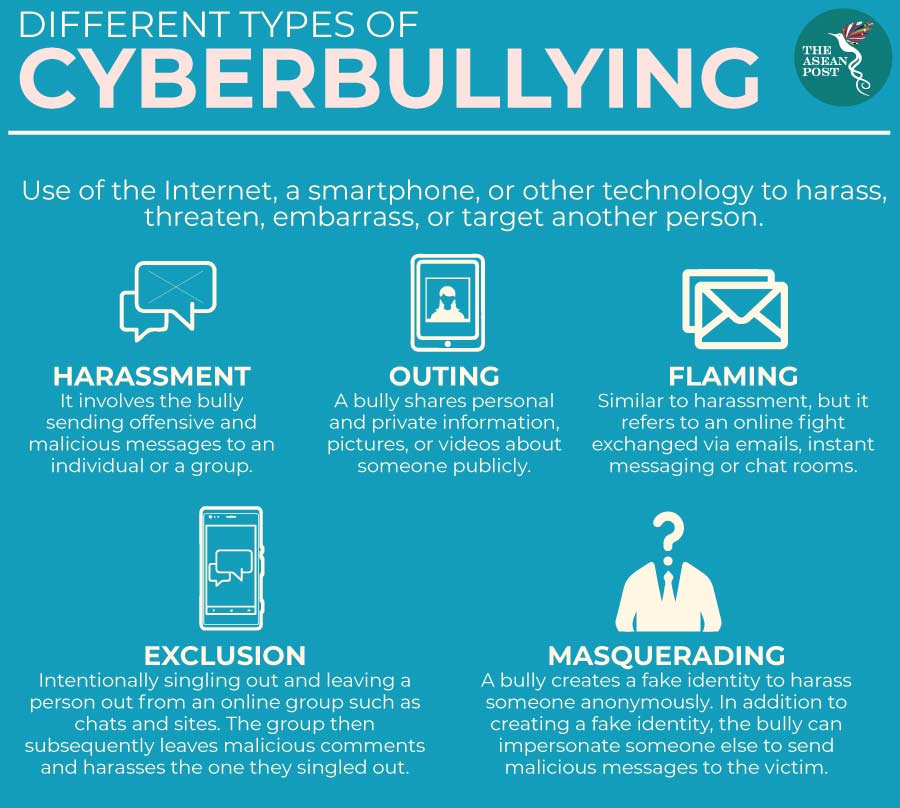

Recently, The ASEAN Post published an article on cyberbullying in Cambodia which pointed to results from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) five-week poll involving one million young people as well as suggestions from its series of student-led #ENDviolence Youth Talks. Following its findings, UNICEF called on Cambodia to put in place a new policy that would help protect the nation’s children from cyberbullying.

It seems, however, that Cambodia isn’t the only country in the region that is facing an issue with policies to combat cyberbullying.

Towards the end of 2018, Indonesian actress Ussy Sulistiawati filed reports against several Instagram users for having posted insults aimed at her children’s physical appearances. What was worth noting about the case was that Ussy had filed reports against the perpetrators under the 2008 Electronic Information and Transactions Law which covers violations including electronic information or documents that contain insults or defamation.

Later, on 29 January, an article published on an online media outlet cited the case and pointed out that the problem with the current law was that it did not include specific provisions for the term “cyberbullying”.

“This makes law enforcers assume that online insults and cyberbullying are the same thing when, in fact, they are different. Cyberbullying does not always take the form of insults. It can also often come in the form of threats and intimidation. Therefore, the law is ineffective at combatting cyberbullying in Indonesia,” the article read.

This matter is pertinent due to several factors which include the high internet penetration in Indonesia, the looming Fourth Industrial Revolution, and most importantly; the statistics related to bullying in Indonesia.

Cyberbullying concerns

In 2015, Indonesia’s Social Minister Khofifah Indar Parawansa said that 40 percent of children in Indonesia who commit suicide do so as a result of bullying. She added that she even knew of instances where student had cut their own wrists after being taunted to do so through text messages from bullies.

Three years earlier, in a 2012 survey released by Indonesia’s National Child Protection Commission (KPAI), 87.6 percent of 1,026 participants polled reported they had been bullied either physically or verbally in school. Many schools, the organisation found, are indifferent to bullying, considering it a natural part of their culture.

The more recent 2018 statistics from the KPAI are also gloomy. It reveals that out of the 161 cases of child abuse it received up until 30 May 2018, 22.4 percent of them involved bullying. Bullying was also the fourth highest cause of crime against children in the country in 2018 after law violations, abusive parents, and cybercrime.

Statistics from an anti-bullying movement in Indonesia, called Sudah Dong (translated to English as “Enough”) states that 10 percent of Indonesian students leave school because of bullying, 71 percent of Indonesian students regard bullying as a problem in their schools, while 90 percent of students from Standard 4 all the way to Year 2 in Middle School have reported being bullied in school.

Cyberbullying, on the other hand, is just a more technologically advanced version of what numerous children in schools all over Indonesia are already facing. And since Indonesia is advancing technologically, cyberbullying should be a worry .

According to We Are Social’s 2018 report, Indonesia has a 50 percent (132.7 million) penetration rate of Internet users, 49 percent (130.0 million) penetration rate of active social media users, 67 percent (177.9 million) penetration rate of unique mobile users, and 45 percent (120 million) penetration rate of active mobile social users. Visiting a social network (which is naturally where most cyberbullying occurs) was placed as the highest weekly online activity with 37 percent of said activity occurring via mobile phones, and six percent by computer.

The most connected demographic in Indonesia according to Indonesia’s Internet Service Provider Association are children aged between 10 to 14 years where penetration has already reached 100 percent.

ASEAN continues down the path of technological achievement and advancement. The bloc does not want to be left behind and certainly wants to remain relevant in an increasingly technologically advanced world. These aspirations are no different for Indonesia but while technology does present many advantages and opportunities, it is not without its dark areas. In order to truly usher in the future, ASEAN must also look at (and address) the challenges that come with it. Cyberbullying is one of those immediate challenges.

Related articles:

Cambodia’s cyberbullied children

Children and social media

Tangshan And Xuzhou: China's Treatment Of Women

Myanmar's suu kyi: prisoner of generals, philippines ends china talks for scs exploration, ukraine war an ‘alarm for humanity’: china’s xi, china to tout its governance model at brics summit, wrist-worn trackers detect covid before symptoms.

- Mode Terang

- Gabung Kompas.com+

- Konten yang disimpan

- Konten yang disukai

- Berikan Masukanmu

- Megapolitan

- Surat Pembaca

- Kilas Daerah

- Kilas Korporasi

- Kilas Kementerian

- Sorot Politik

- Kilas Badan Negara

- Kelana Indonesia

- Kalbe Health Corner

- Kilas Parlemen

- Konsultasi Hukum

- Infrastructure

- Apps & OS

- Tech Innovation

- Kilas Internet

- Elektrifikasi

- Timnas Indonesia

- Liga Indonesia

- Liga Italia

- Liga Champions

- Liga Inggris

- Liga Spanyol

- Internasional

- Sadar Stunting

- Spend Smart

- Smartpreneur

- Kilas Badan

- Kilas Transportasi

- Kilas Fintech

- Kilas Perbankan

- Tanya Pajak

- Sorot Properti

- Tips Kuliner

- Tempat Makan

- Panduan Kuliner Yogyakarta

- Beranda UMKM

- Jagoan Lokal

- Perguruan Tinggi

- Pendidikan Khusus

- Kilas Pendidikan

- Jalan Jalan

- Travel Tips

- Hotel Story

- Travel Update

- Nawa Cahaya

- Ohayo Jepang

- Kehidupan sehat dan sejahtera

- Air bersih dan sanitasi layak

- Pendidikan Berkualitas

- Energi Bersih dan Terjangkau

- Penanganan Perubahan Iklim

- Ekosistem Lautan

- Ekosistem Daratan

- Tanpa Kemiskinan

- Tanpa Kelaparan

- Kesetaraan Gender

- Pekerjaan Layak dan Pertumbuhan ekonomi

- Industri, Inovasi & Infrastruktur

- Berkurangnya Kesenjangan

- Kota & Pemukiman yang Berkelanjutan

- Konsumsi & Produksi yang bertanggungjawab

Menilik Fenomena "Bullying" Pelajar Indonesia

Kompas.com Tren

Saat ini, aktivitas mendengarkan siniar ( podcast ) menjadi aktivitas ke-4 terfavorit dengan dominasi pendengar usia 18-35 tahun. Topik spesifik serta kontrol waktu dan tempat di tangan pendengar, memungkinkan pendengar untuk melakukan beberapa aktivitas sekaligus, menjadi nilai tambah dibanding medium lain.

Medio yang merupakan jaringan KG Media, hadir memberikan nilai tambah bagi ranah edukasi melalui konten audio yang berkualitas, yang dapat didengarkan kapan pun dan di mana pun. Kami akan membahas lebih mendalam setiap episode dari channel siniar yang belum terbahas pada episode tersebut.

Info dan kolaborasi: [email protected]

Menilik Fenomena "Bullying" Pelajar Indonesia

Oleh: Alifia Putri Yudanti dan Rizky Nauvalif

KOMPAS.com - Aksi perundungan atau bullying bisa terjadi di mana saja dan oleh siapa saja. Mulai dari lingkungan sekolah, pertemanan, hingga pekerjaan yang berdampak langsung terhadap kesehatan mental korban.

Sering kali, korban yang dirundung merasa trauma dan dibayang-bayangi perilaku perundungan yang menimpanya. Hal ini karena aksi tersebut dilakukan saat korban berada di bangku sekolah yang seharusnya menjadi masa bersenang-senang dan mengeksplorasi banyak hal.

Di sisi lain, banyak pelaku yang tak sadar dan tetap hidup bebas padahal mereka telah menorehkan luka ke para korban. Isu ini juga dibahas oleh Kukuh dan Dwik dalam siniar Balada +62 episode “Jadi Pelaku Bully Bisa Hidup Enak?” dengan tautan s.id/Balada62Bully .

Sayangnya, meskipun banyak kasus yang diangkat ke media, namun aksi perundungan terus terjadi di sekitar kita. Lantas, mengapa hal ini bisa terjadi?

Fenomena Bullying di Kalangan Pelajar Indonesia

Perundungan di lingkungan akademik yang seharusnya menjadi ruang aman untuk menuntut ilmu menambah bukti mirisnya pendidikan Indonesia.

Dalam laporan UNICEF (2020) tercatat setidaknya ada 41 persen pelajar di Indonesia berusia 15 tahun pernah mengalami perundungan. Sementara itu, 22 persen perundungan yang mereka terima berupa ejekan dan penghancuran barang secara paksa.

Selain itu, masih banyak sekolah dan tenaga pendidik yang kurang peduli terhadap hal ini. Beberapa dari mereka bahkan menganggap perundungan sebagai candaan biasa antarteman. Bahkan, ada pula tenaga pendidik yang turut memberikan candaan berlebihan kepada siswanya.

Menurut Anggin Nuzula Rahmah , Asisten Deputi Pemenuhan Hak Anak atas Kesehatan dan Pendidikan, tidak pula sedikit guru yang melakukan kekerasan dengan tujuan pendisiplinan. Mereka mendisiplinkan anak-anak dengan cara-cara kekerasan yang juga termasuk ke dalam aksi perundungan.

Baca juga: Ajarkan Anak Keberagaman dan Inklusivitas

Padahal, kasus perundungan yang kurang mendapat perhatian, bisa menyebabkan jatuhnya korban. Hal yang sangat disayangkan, kasus perundungan yang dianggap sepele terjadi karena efek yang belum tampak secara langsung.

Selain itu, banyak pula korban yang enggan melapor karena takut, malu, atau takut diancam oleh pelaku. Bisa pula korban sudah melapor namun tidak mendapat tanggapan serius oleh pihak sekolah.

Itulah mengapa, pembentukan budaya dan lingkungan sekolah yang sadar akan kasus perundungan sangat dibutuhkan. Sekolah harus memiliki program pencegahan, intervensi, dan sosialisasi yang memadai sekaligus penanganan yang sungguh-sungguh.

Dampak Bullying bagi Anak yang Masih Pelajar

Seorang pelajar yang menjadi korban perundungan tentu akan berdampak terhadap kesehatan mental. Mereka akan menjadi pribadi yang tertutup dan enggan bergabung dengan teman-teman yang lain.

Hal ini terjadi karena mereka memiliki ketakutan untuk mulai berinteraksi dengan orang baru karena khawatir akan mengalami aksi yang serupa. Perasaan takut ini pun bisa bertumbuh hingga mereka dewasa dan menjadi perasaan trauma.

Bahkan, perasaan traumatis ini pun kini tak menunggu mereka dewasa. Sebab, ada beberapa kasus yang merenggut nyawa korbannya.

Melansir Kompas.com, pada Juli 2023…

Tag bullying perundungan medio by kg media balada 62 bullying pelajar indonesia.

Instagram Paling Rawan Cyber Bullying, Twitter Paling Aman, Mengapa?

"Bullying" Picu Siswa SMP di Temanggung Bakar Sekolah, Jadi Tersangka, Disebut Kepsek Caper

9 Cara Mencegah Bullying, Apa Saja?

Mengapa Banyak Kasus "Bullying" Terjadi di Korsel?

TTS Eps 137: Yuk Lebaran

TTS Eps 136: Takjil Khas di Indonesia

TTS Eps 135: Serba Serbi Ramadhan

Games Permainan Kata Bahasa Indonesia

TTS - Serba serbi Demokrasi

TTS Eps 130 - Tebak-tebakan Garing

TTS - Musik Yang Paling Mengguncang

Berita terkait.

Terkini Lainnya

Perusahaan Brunei Ingin Bangun Kereta Cepat Lintasi IKN dan Malaysia

BMKG: Daftar Wilayah yang Berpotensi Gelombang Tinggi pada 3-5 April 2024

Syarat dan Cara Berobat di Luar Kota Pakai BPJS Kesehatan Saat Mudik Lebaran

Ilmuwan Deteksi Gempa Bumi Tertua dari Batuan yang Berumur Miliaran Tahun

Jarang Diketahui, Ini Tanda Tubuh Terlalu Banyak Minum Teh

Taylor Swift Masuk Daftar Miliarder Dunia Versi Forbes dengan Total Kekayaan Rp 17,5 Triliun

Jam Operasional BCA Selama Libur Lebaran 2024

UI Buka Suara soal Pengunduran Diri Seluruh Anggota Satgas PPKS

Analisis Gempa M 5,6 yang Guncang Laut Jawa, Tidak Berpotensi Tsunami

7 Minuman yang Bisa Menghilangkan Lemak Perut, Apa Saja?

Jam Pelayanan BPJS Kesehatan dan BPJS Ketenagakerjaan Selama Lebaran 2024

Ada Promo Tiket Masuk Gembira Loka, Bisa Buat Libur Lebaran 2024

Chan Chan Kota Lumpur

Eks Agen FBI Ungkap Tanda-tanda Orang yang Tidak Jujur Saat Berkomunikasi

Jam Operasional Bank Mandiri Selama Libur Lebaran 2024

Ilmuwan temukan samudra di perut bumi, tiga kali lipat lebih besar dari lautan biasa, 5 air rebusan bahan alami untuk menurunkan gula darah, lebaran 2024 tanggal berapa ini menurut muhammadiyah, nu, dan pemerintah, apakah gerhana matahari total akan mengakibatkan bumi gelap gulita, kata sri mulyani, risma, airlangga, dan muhadjir usai diminta hadir sidang sengketa pilpres 2024, now trending.

Ketua MK Heran Respons Laporan Bawaslu Tak Seragam dan Rugikan Pelapor

KPK Tanyakan soal Dugaan Investasi Fiktif di PT Taspen kepada Eks Dirut

Gempa Dahsyat Taiwan: 9 Orang Tewas, 900 Terluka, 50 Pekerja Masih Hilang

Kata Bos Tokopedia soal Dugaan "Predatory Pricing" di TikTok Shop

Nadiem Bantah Pramuka Dihapus dari Ekskul Wajib Sekolah, Ingin Masukkan ke Kurikulum Merdeka

Momen Hotman Paris dan BW Saling Ejek di Sidang MK, Sampai Ditengahi Hakim Saldi Isra

Tak Dibantah KPU, Kubu Anies dan Ganjar Anggap Pencalonan Gibran Tidak Sah Terbukti

Anggota TNI Tewas Bersimbah Darah di Bekasi, Ternyata Korban Pembunuhan

Mungkin anda melewatkan ini.

8 Pelayanan Gigi yang Ditanggung BPJS Kesehatan, Termasuk Protesa Gigi

Video Viral Orang Utan Kurus Berjalan di Area Tambang, Ini Kata BKSDA

Gratis Tiket Masuk Ancol 26 September 2023, Ini Syarat dan Caranya

Hobi Minum Latte Bisa Picu Jerawat, Ini Penjelasan Dokter

Jumlah Air Putih yang Perlu Diminum Penderita Diabetes, Berapa Banyak?

- Entertainment

- Pesona Indonesia

- Artikel Terpopuler

- Artikel Terkini

- Topik Pilihan

- Artikel Headline

- Harian KOMPAS

- Kompasiana.com

- Pasangiklan.com

- Gramedia.com

- Gramedia Digital

- Gridoto.com

- Bolasport.com

- Kontan.co.id

- Kabar Palmerah

- Kebijakan Data Pribadi

- Pedoman Media Siber

Copyright 2008 - 2023 PT. Kompas Cyber Media (Kompas Gramedia Digital Group). All Rights Reserved.

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Kontras tinggi

Cari UNICEF

Cyberbullying: apa itu dan bagaimana menghentikannya, 10 hal yang remaja ingin tahu dari cyberbullying..

- Tersedia dalam:

“Apa yang ingin kamu ketahui dari cyberbullying?”

Kami mengajukan pertanyaan ini kepada orang muda dan menerima ribuan tanggapan dari mereka di seluruh dunia!

Kami mengumpulkan spesialis dari UNICEF, pakar cyberbullying dan perlindungan anak, pegiat pencegahan cyberbullying, serta bekerja sama dengan Facebook, Instagram, dan Twitter untuk menjawab pertanyaan-pertanyaan dan memberikan saran tentang cara untuk menghadapi cyberbullying .

Apa itu cyberbullying ?

Cyberbullying (perundungan dunia maya) ialah b ullying /perundungan dengan menggunakan teknologi digital. Hal ini dapat terjadi di media sosial, platform chatting , platform bermain game , dan ponsel. Adapun menurut Think Before Text, cyberbullying adalah perilaku agresif dan bertujuan yang dilakukan suatu kelompok atau individu, menggunakan media elektronik, secara berulang-ulang dari waktu ke waktu, terhadap seseorang yang dianggap tidak mudah melakukan perlawanan atas tindakan tersebut. Jadi, terdapat perbedaan kekuatan antara pelaku dan korban. Perbedaan kekuatan dalam hal ini merujuk pada sebuah persepsi kapasitas fisik dan mental.

Cyberbullying merupakan perilaku berulang yang ditujukan untuk menakuti, membuat marah, atau mempermalukan mereka yang menjadi sasaran. Contohnya termasuk:

- Menyebarkan kebohongan tentang seseorang atau memposting foto memalukan tentang seseorang di media sosial

- Mengirim pesan atau ancaman yang menyakitkan melalui platform chatting , menuliskan kata-kata menyakitkan pada kolom komentar media sosial, atau memposting sesuatu yang memalukan/menyakitkan

- Meniru atau mengatasnamakan seseorang (misalnya dengan akun palsu atau masuk melalui akun seseorang) dan mengirim pesan jahat kepada orang lain atas nama mereka.

- Trolling - pengiriman pesan yang mengancam atau menjengkelkan di jejaring sosial, ruang obrolan, atau game online

- Mengucilkan, mengecualikan, anak-anak dari game online, aktivitas, atau grup pertemanan

- Menyiapkan/membuat situs atau grup (group chat, room chat) yang berisi kebencian tentang seseorang atau dengan tujuan untuk menebar kebencian terhadap seseorang

- Menghasut anak-anak atau remaja lainnya untuk mempermalukan seseorang

- Memberikan suara untuk atau menentang seseorang dalam jajak pendapat yang melecehkan

- Membuat akun palsu, membajak, atau mencuri identitas online untuk mempermalukan seseorang atau menyebabkan masalah dalam menggunakan nama mereka

- Memaksa anak-anak agar mengirimkan gambar sensual atau terlibat dalam percakapan seksual.

Bullying secara langsung atau tatap muka dan cyberbullying seringkali dapat terjadi secara bersamaan. Namun cyberbullying meninggalkan jejak digital – sebuah rekaman atau catatan yang dapat berguna dan memberikan bukti ketika membantu menghentikan perilaku salah ini.

10 pertanyaan teratas tentang cyberbullying

- Apakah saya sedang di- bully secara online ? Bagaimana kita membedakan antara lelucon/candaan dengan bullying ?

- Apa dampak dari cyberbullying ?

- Kepada siapa saya harus berbicara jika seseorang mem- bully saya secara online ? Mengapa melapor itu penting?

- Saya mengalami cyberbullying , tapi saya takut untuk berbicara dengan orang tua saya tentang hal itu. Bagaimana saya bisa mendekati mereka?

- Bagaimana saya bisa membantu teman saya untuk melaporkan kasus cyberbullying terutama jika mereka tidak mau melaporkannya?

- Menjelajah secara online memberi saya akses ke banyak informasi; tetapi itu juga berarti saya terbuka terhadap berbagai kemungkinan penyalahgunaan atau perilaku salah. Bagaimana kita menghentikan cyberbullying tanpa bermain internet? Apakah kita perlu berhenti saja mengakses internet atau media sosial?

- Bagaimana cara mencegah informasi pribadi saya disalahgunakan untuk dipermalukan atau dimanipulasi di media sosial?

- Apakah ada hukuman untuk cyberbullying ?

- Perusahaan internet/media sosial tampaknya tidak peduli dengan cyberbullying dan pelecehan. Apakah mereka sebenarnya bertanggung jawab?

- Apakah ada pedoman/sarana/perangkat mengenai anti- cyberbullying untuk anak-anak atau orang muda?

1. Apakah saya sedang di-bully secara online? Bagaimana kita membedakan antara lelucon/candaan dengan bullying?

UNICEF: Semua teman suka bercanda dengan satu sama lain, tetapi kadang-kadang sulit untuk mengatakan apakah seseorang hanya sedang bersenang-senang atau mencoba menyakitimu, terutama saat di internet. Kadang-kadang mereka akan menertawakannya dengan mengatakan “cuma bercanda kok,” atau “jangan dianggap serius dong.”

Tetapi kalau kamu merasa terluka atau berpikir sepertinya mereka ‘menertawakanmu’ bukan ‘tertawa bersamamu’, maka lelucon atau candaannya mungkin sudah terlalu jauh. Kalau itu terus berlanjut bahkan setelah kamu meminta orang itu untuk berhenti dan kamu masih saja merasa kesal tentang hal itu, maka ini bisa jadi adalah bullying .

Dan ketika bullying terjadi secara online , ini dapat menarik perhatian yang tidak diinginkan dari berbagai orang termasuk orang asing yang tidak kamu kenal. Di mana pun itu terjadi, jika kamu tidak nyaman dengan hal itu, kamu perlu melakukan pembelaan.

Katakan apa yang kamu inginkan – jika kamu merasa tidak senang dan tetap saja tidak berhenti, maka ada baiknya kamu mencari bantuan. Menghentikan cyberbullying bukan hanya tentang mengungkapkan siapa saja para pelaku bully , namun juga tentang menekankan bahwa semua orang berhak untuk dihormati – baik di dunia maya maupun di dunia nyata.

>> Kembali ke atas

2. Apa dampak dari cyberbullying?

UNICEF : Bullying terjadi secara online, kamu bisa merasa seperti diserang dari mana-mana, bahkan di dalam rumahmu sendiri. Sepertinya tidak ada jalan untuk keluar. Dampaknya dapat bertahan lama dan memengaruhi seseorang dalam banyak cara:

Secara Mental — merasa kesal, malu, bodoh, bahkan marah

Secara Emosional — merasa malu atau kehilangan minat pada hal-hal yang kamu sukai

Secara Fisik — lelah (kurang tidur), atau mengalami gejala seperti sakit perut dan sakit kepala

Perasaan ditertawakan atau dilecehkan oleh orang lain dapat membuat seseorang tidak ingin membicarakan atau mengatasi masalah tersebut. Dalam kasus ekstrim, cyberbullying bahkan dapat menyebabkan seseorang mengakhiri nyawanya sendiri.

Cyberbullying dapat mempengaruhi kita dengan berbagai cara, tetapi tentunya masalah ini dapat diatasi dan orang-orang yang terdampak juga dapat memperoleh kembali kepercayaan diri dan kesehatan mental mereka.

Bully.id: Semua anak yang terpapar oleh cyberbullying dapat menderita: baik itu korban, pelaku dan orang menyaksikan cyberbullying.

Anak-anak yang mengalami cyberbullying, umumnya:

- Menunjukkan ciri-ciri depresi

- Memiliki masalah kepercayaan dengan orang lain

- Tidak diterima oleh rekan-rekan mereka

- Selalu waspada dan curiga terhadap orang lain (kekhawatiran berlebih)

- Memiliki masalah menyesuaikan diri dengan sekolah

- Kurang motivasi sehingga sulit fokus dalam mengikuti pembelajaran

Think Before Text

Dampak bagi korban:

- Dampak psikologis: mudah depresi, marah, timbul perasaan gelisah, cemas, menyakiti diri sendiri, dan perfobaan bunuh diri

- Dampak sosial: menarik diri, kehilangan kepercayaan diri, lebih agresif kepada teman dan keluarga

- Dampak pada kehidupan sekolah: penurunan prestasi akademik, rendahnya tingkat kehadiran, perilaku bermasalah di sekolah.

Dampak bagi Pelaku: Cenderung bersifat agresif, berwatak keras, mudah marah, impulsif, lebih ingin mendominasi orang lain, kurang berempati, dan dapat dijauhi oleh orang lain.

Dampak bagi yang menyaksikan ( bystander ): Jika cyberbullying dibiarkan tanpa tindak lanjut, maka orang yan menyaksikan dapat berasumsi bahwa cyberbullying adalah perilaku yang diterima secara sosial. Dalam kondisi ini, beberapa orang mungkin akan bergabung dengan penindas karena takut menjadi sasaran berikutnya dan beberapa lainnya mungkin hanya akan diam saja tanpa melakukan apapun dan yang paling parah mereka merasa tidak perlu menghentikannya.

3. Kepada siapa saya harus berbicara jika seseorang mem-bully saya secara online? Mengapa melapor itu penting?

UNICEF: Jika kamu merasa sedang di- bully , langkah pertama yang perlu dilakukan adalah mencari bantuan dari seseorang yang kamu percaya seperti orang tua, anggota keluarga terdekat atau orang dewasa terpercaya lainnya.

Di sekolah, kamu bisa menghubungi guru yang kamu percaya seperti guru BK, guru olahraga, atau guru mata pelajaran.

Dan jika kamu merasa tidak nyaman berbicara dengan seseorang yang kamu kenal, hubungi Telepon Pelayanan Sosial Anak (TePSA) di nomor telepon 1500 771, atau nomor handphone / Whatsapp 081238888002 dan kamu bisa ngobrol dengan konselor profesional yang ramah!

Jika bullying terjadi di media sosial, kamu bisa memblokir akun pelaku dan melaporkan perilaku mereka di media sosial itu sendiri. Media sosial berkewajiban menjaga keamanan penggunanya, loh.

Mengumpulkan dan menyimpan bukti-bukti bisa membantumu nanti untuk menunjukkan apa yang telah terjadi – misalnya seperti pesan dalam chatting dan screenshot postingan di media sosial.

Agar bullying berhenti, kuncinya ialah perlu diidentifikasi dan dilaporkan lebih lanjut. Hal ini juga dapat menunjukkan kepada pelaku bully bahwa tindakan mereka tidak dapat diterima.

Jika kamu berada dalam keadaan bahaya saat itu juga, maka kamu harus menghubungi polisi atau layanan darurat, seperti berikut:

- Ambulan: 118 atau 119

- Polisi: 110

- Pemadam Kebakaran: 113 atau 1131

- Badan Search and Rescue Nasional (BASARNAS): 115

Facebook/Instagram: Jika kamu di- bully secara online , kami mendorongmu untuk membicarakannya dengan orang tua, guru, atau seseorang yang kamu percaya – kamu punya hak untuk merasa aman. Melaporkan tindakan bullying secara langsung sangat dimudahkan di Facebook maupun Instagram.

Kamu selalu dapat mengirim laporan (secara anonim) mengenai postingan, komentar, atau story yang tidak menyenangkan di Facebook maupun Instagram.

Facebook maupun Instagram memiliki tim yang selalu melihat laporan-laporan ini selama 24 jam di seluruh dunia dalam lebih dari 50 bahasa, dan postingan apa pun yang bersikap kasar, mengganggu, atau membully akan segera dihapus. Laporan-laporan ini selalu anonim (atau tidak diperlihatkan siapa yang melapor).

Kami punya panduan di Facebook yang dapat mengarahkanmu untuk melalui proses penanganan bullying – atau apa yang harus dilakukan jika kamu melihat seseorang dibully. Di Instagram, kita juga punya Panduan untuk Orang Tua yang memberikan rekomendasi untuk orang tua, wali, dan orang dewasa terpercaya tentang cara menyikapi cyberbullying , dan sebuah central hub dimana kamu bisa mempelajari tentang perangkat keamanan Instagram.

Twitter: Jika kamu pikir bahwa kamu sedang dibully, hal terpenting adalah memastikan dirimu aman. Sangat penting untuk memiliki seseorang untuk diajak bicara tentang apa yang sedang kamu alami. Bisa saja seorang guru, orang dewasa terpercaya lainnya, atau orang tua. Bicaralah dengan orang tua dan temanmu tentang apa yang harus dilakukan jika kamu (atau seorang teman) sedang mengalami cyberbullying .

Kami mendorong setiap orang untuk melaporkan akun yang melanggar aturan. Kamu bisa melakukan ini melalui halaman Pusat Bantuan atau mengklik pilihan “Laporkan Tweet” pada Tweet seseorang.

Bully.id: Kamu juga dapat menghubungi konselor Bully.id Indonesia secara online, dimana konselor, psikolog dan pengacara (lawyer) berlisensi dapat mendengarkan dan memberikan dukungan yang dibutuhkan, baik via live chat, audio maupun video call. Jika kamu masih berusia di awah 18 tahun, silakan minta bantuan orang dewasa untuk mengakses webnya ya.

4. Saya mengalami cyberbullying, tapi saya takut untuk berbicara dengan orang tua saya tentang hal itu. Bagaimana saya bisa mendekati mereka?

UNICEF : Kalau kamu mengalami cyberbullying , berbicara dengan orang dewasa terpercaya – seseorang yang membuatmu merasa aman untuk diajak bicara – adalah salah satu langkah pertama yang paling penting yang dapat kamu lakukan.

Berbicara kepada orang tua tidak mudah bagi semua orang. Tetapi ada beberapa hal yang dapat kamu lakukan untuk membantu memulai percakapan. Pilih waktu bicara ketika kamu rasa mereka bisa memberikan perhatian penuh. Jelaskan seberapa serius masalahnya bagi kamu. Ingatlah, mereka mungkin tidak terbiasa dengan teknologi seperti kamu, jadi mungkin kamu perlu membantu mereka untuk memahami apa yang terjadi.

Mereka mungkin tidak memiliki jawaban instan untuk kamu, tetapi mereka cenderung ingin membantu dan bersama-sama denganmu menemukan solusi. Dua kepala selalu lebih baik daripada satu! Jika kamu masih tidak yakin tentang apa yang harus dilakukan, pertimbangkan untuk menghubungi orang-orang terpercaya lainnya. Seringkali ada lebih banyak orang yang peduli padamu dan bersedia membantu daripada yang mungkin sedang kamu pikirkan!

Berikut beberapa ide untuk membuka percakapan:

“Ibu/Ayah, saya ingin berbicara tentang sesuatu yang terjadi pada saya di media sosial tempo hari. Agak sulit bagi saya untuk membicarakannya… dan jika saya memberi tahu apa yang terjadi, saya tidak ingin Ibu/Ayah mengambil hak saya untuk menggunakan Internet … jadi, ya, bagaimanapun, inilah yang terjadi… ”

“Ibu / Ayah, aku mendapat direct message ini beberapa hari yang lalu, dan itu membuatku takut…”

“Ibu / Ayah, aku butuh bantuanmu untuk mencari tahu bagaimana menangani sesuatu yang terjadi secara online…”

5. Bagaimana saya bisa membantu teman saya untuk melaporkan kasus cyberbullying terutama jika mereka tidak mau melaporkannya?

UNICEF: Siapapun bisa menjadi korban cyberbullying . Jika kamu melihat ini terjadi pada seseorang yang kamu tahu, cobalah menawarkan dukungan atau bantuan.

Penting untuk mendengarkan temanmu. Mengapa dia tidak mau melaporkan kasus cyberbullying itu? Bagaimana perasaan dia? Beritahu dia bahwa tidak perlu melaporkan secara formal kepada pihak tertentu, tetapi penting untuk berbicara dengan seseorang yang mungkin bisa membantu.

Ingat, teman kamu mungkin sedang merasa rapuh. Berbaik hatilah kepadanya. Bantu dia memikirkan apa yang harus dikatakan dan kepada siapa. Tawarkan untuk pergi bersama jika mereka memutuskan untuk melapor. Yang paling penting, ingatkan dia bahwa kamu ada untuknya dan ingin membantu.

Jika teman kamu masih tidak ingin melaporkan kejadian itu, maka dukung dia dalam menemukan orang dewasa terpercaya yang dapat membantu mengatasi situasi tersebut. Ingatlah bahwa dalam situasi tertentu dampak dari cyberbullying dapat mengancam nyawa.

Jika kamu hanya diam dan tidak melakukan apa pun, maka temanmu akan merasa semakin tidak dipedulikan. Kata-kata darimu dapat membuat perbedaan pada perasaannya.

Facebook/Instagram: Kami tahu sulit untuk melaporkan seseorang. Tapi, membully seseorang juga bukanlah sesuatu yang bisa diterima.

Facebook dan Instagram memiliki tombol “Report” atau “Laporkan”. Melaporkan konten ke Facebook atau Instagram dapat membantu agar kamu tetap aman di media sosial tersebut. Bullying dan pelecehan pada dasarnya bersifat sangat pribadi, jadi dalam banyak kasus, dibutuhkan seseorang untuk melaporkan perilaku ini kepada Facebook atau Instagram sebelum dapat dilihat dan dihapus oleh Facebook atau Instagram.

Melaporkan kasus cyberbullying selalu bersifat anonim (identitas dirahasiakan) di Instagram dan Facebook, dan tidak ada yang akan tahu bahwa kamu lah pelapornya.

Kamu dapat melaporkan sesuatu yang kamu alami sendiri, tetapi juga mudah untuk melaporkan sesuatu untuk temanmu menggunakan fitur yang tersedia di aplikasi. Informasi lebih lanjut tentang cara melaporkan sesuatu terdapat di Pusat Bantuan Instagram dan di Pusat Bantuan Facebook .

Kamu juga bisa memberi tahu temanmu tentang fitur di Instagram yang disebut Restrict atau Batasi , dimana kamu bisa secara diam-diam melindungi akunmu tanpa harus memblokir seseorang – yang mungkin kalau memblokir rasanya terlalu keras bagi beberapa orang.

Twitter: Ada panduan untuk melaporkan perilaku yang bersifat menghina yang artinya kamu bisa melaporkan orang lain untuk membela temanmu. Sekarang ini dapat dilakukan untuk melaporkan pencemaran informasi pribadi dan akun palsu juga.

Think Before Text:

- Tenangkan teman yang menjadi korban cyberbullying agar mereka tidak merasa sendirian, mencoba menghibur mereka, memberikan saran praktis

- Dukung teman yang menjadi korban cyberbullying namun hindari untuk memperburuk keadaan dengan bertengkar, merencanakan balas dendam, bersikap kejam, atau melakukan kekerasan.

- Bantu mereka untuk mem-blokir atau memprivasi akun agar terhindar dari ancaman atau pesan berbahaya

- Lapor kepada orang tua atau guru di sekolah tentang apa yang terjadi.

6. Menjelajah secara online memberi saya akses ke banyak informasi; tetapi itu juga berarti saya terbuka terhadap berbagai kemungkinan penyalahgunaan atau perilaku salah. Bagaimana kita menghentikan cyberbullying tanpa bermain internet? Apakah kita perlu berhenti saja mengakses internet atau media sosial?

UNICEF: Menjelajah secara online memberimu banyak manfaat. Namun, seperti banyak hal dalam hidup, ada juga risiko yang perlu kita hindari.

Jika kamu mengalami cyberbullying , kamu mungkin ingin menghapus aplikasi tertentu atau mencoba offline selama beberapa lama agar kamu merasa pulih. Namun, berhenti mengakses internet bukanlah solusi jangka panjang. Kamu tidak salah, jadi kenapa kamu yang harus dirugikan? Bahkan mungkin ini dapat mengirim sinyal yang salah kepada pelaku bully, yaitu menerima perilaku mereka yang tidak pantas.

Kita semua ingin cyberbullying dihentikan, yang merupakan salah satu alasan pelaporan cyberbullying menjadi sangat penting. Tetapi menciptakan internet menjadi aman seperti yang kita inginkan tidak hanya sekedar mengungkap para pelaku bully tersebut satu per satu. Kita perlu berpikir apakah yang akan kita bagikan atau katakan dapat menyakiti orang lain. Kita harus baik terhadap satu sama lain secara online dan dalam kehidupan nyata. Semua terserah kita! Ayo saring sebelum sharing !

Facebook/Instagram: Menjaga Instagram dan Facebook menjadi tempat yang aman dan positif untuk mengekspresikan diri adalah penting – orang hanya akan merasa nyaman berbagi jika mereka merasa aman. Tapi, kita tahu bahwa cyberbullying bisa muncul dan menciptakan pengalaman negatif. Itulah sebabnya di Instagram dan Facebook, kita perlu melawan dan mencegah cyberbullying .

Kita bisa melakukan ini dengan dua cara. Pertama, dengan menggunakan teknologi untuk mencegah orang mengalami dan melihat bullying . Misalnya, orang dapat mengaktifkan pengaturan saring komentar yang menggunakan teknologi kecerdasan buatan untuk otomatis menyaring dan menyembunyikan komentar bullying yang bertujuan untuk melecehkan atau membuat marah orang.

Kedua, kita bisa berupaya mendorong perilaku dan interaksi positif dengan memberitahukan fitur untuk dapat digunakan di Facebook dan Instagram. Restrict atau Batasi adalah salah satu cara untuk membantumu secara diam-diam melindungi akun sambil tetap mengawasi pelaku bully.

Twitter: Karena ratusan juta orang berbagi ide di Twitter, tidak mengherankan kalau kita semua sering menghadapi perbedaan pendapat. Itulah salah satu manfaatnya karena kita semua bisa belajar dari perbedaan pendapat dan diskusi yang saling menghormati.

Tetapi kadang-kadang, setelah kamu mendengarkan seseorang untuk beberapa lama, kamu mungkin tidak mau mendengarnya lagi. Hak mereka untuk mengekspresikan pendapat bukan berarti kamu harus selalu mendengarkannya setiap saat.

Setting social media akun dengan private account. Pikirkan baik-baik tentang apa yang kamu pos secara online, follow akun-akun yang bermanfaat dan bernilai positif dan jangan izinkan akun anonim mengikuti kamu di social media akun kamu. Upayakan semua follower kamu adalah orang-orang yang kamu kenal, baik teman maupun keluarga.

Ingat apa pun yang kamu posting dapat dibagikan. Bahkan dengan pengaturan privasi yang kuat, penting bagi kamu untuk memahami fakta bahwa apa yang kamu posting secara online tidak pernah benar-benar pribadi dan selalu dapat dibagikan. Oleh karena itu, penting bagi kamu untuk selalu berpikir sebelum memposting. Hindari memposting hal-hal yang sifatnya pribadi, seperti alamat rumah, debit card dan usahakan untuk tidak over-sharing di social media.

Kenali akun palsu. Tidak semua orang di media sosial akan menjadi seperti yang mereka katakan. Mungkin ada orang muda dan dewasa yang berpura-pura menjadi orang lain dan dapat menyakiti kamu. Misalnya, mereka mungkin ingin menipu kamu agar memberikan informasi pribadi atau pribadi yang dapat mereka gunakan untuk melawan Anda. Penting bagi kamu untuk tidak bertemu dengan seseorang yang tidak kamu kenal, apalagi yang hanya berkenalan via social media. Pastikan kamu selalu memberi tahu orang dewasa kemana kamu akan pergi dan siapa yang kamu temui. Ada saat-saat di mana kamu bisa jadi tertipu untuk bertemu orang dewasa yang kemudian menyakiti kamu.

Bersihkan kontak pertemanan kamu di social media. Setelah kamu mendapatkan teman di social media, bukan berarti kamu harus selamanya berteman dengan mereka di social media platform.Tinjau dan bersihkan kontak kamu secara teratur - terutama siapa pun yang menyebarkan konten negatif atau tidak membuat kamu merasa nyaman dengan diri sendiri.

Blokir siapa saja yang mengganggu kamu. Semua situs media sosial memungkinkan kamu memblokir orang yang tidak kamu inginkan mengakses akun kamu. Kamu bisa seterusnya memblokir akun tersebut dan juga bisa meng-unblock nya di kemudian hari, ketika kamu memblokir akun orang tersebut, tidak akan notifikasi yang terkirim ke pesan atau email orang tersebut, mereka tidak akan diberi tahu oleh pihak social media platform dan yang terjadi adalah mereka tidak dapat lagi menemukan akun atau profil kamu di social media.

Lindungi identitas kamu. Nomor telepon, alamat, detail bank, dan informasi apa pun yang mungkin mengisyaratkan kata sandi pribadi kamu tidak boleh dibagikan secara online. Peretas sandi atau situs phishing berpengalaman dapat mengumpulkan informasi kamu untuk mendapatkan akses ke akun Anda, atau menggunakan identitas kamu untuk membuat yang baru. Pastikan kata sandi kuat, ubah secara teratur dan selalu jaga kerahasiaannya.

Untuk menghindarkan diri dari perilaku cyberbullying, kamu bisa meningkatkan :

- Empati (memahami perasaan orang lain)

- Hati Nurani (mendengar suara hati yang membantu untuk melakukan hal yang benar )

- Kontrol diri (berpikir sebelum bertindak)

- Menghormati Orang lain (memperlakukan orang lain dengan baik sebagaimana ia ingin orang lain memperlakukan dirinya)

- Kebaikan Hati (menunjukkan kepedulian terhadap kesejahteraan dan perasaan orang lain)

- Toleransi (menghargai perbedaan, pandangan dan keyakinan baru, serta menghargai orang lain tanpa membedakan suku, gender, penampilan, budaya, dan kepercayaan,)

- Keadilan (memperlakukan orang lain dengan baik, tidak memihak, dan adil).

Untuk menghindarkan diri dari pelaku cyberbullying hal yang dapat kamu lakukan:

- Kumpulkan bukti

7. Bagaimana cara mencegah informasi pribadi saya disalahgunakan untuk dipermalukan atau dimanipulasi di media sosial?

UNICEF: Berpikirlah dua kali sebelum memposting atau membagikan sesuatu secara online – karena postingan itu dapat tetap berada di internet selamanya dan dapat digunakan untuk membahayakan dirimu nanti. Jangan memberikan detail pribadi seperti alamat, nomor telepon, atau nama sekolahmu.

Pelajari tentang pengaturan privasi aplikasi media sosial favoritmu. Berikut adalah beberapa tindakan yang dapat kamu lakukan:

- Kamu dapat memutuskan siapa saja yang dapat melihat profilmu, mengirimi pesan langsung atau mengomentari postinganmu dengan menyesuaikan pengaturan privasi akun kamu.

- Kamu dapat melaporkan komentar, pesan, dan foto yang menyakitkan dan meminta media sosial tersebut untuk menghapusnya.

- Selain ‘un-friend’ atau ‘un-follow’, kamu dapat memblokir seseorang untuk menghentikan mereka melihat profilmu atau menghubungimu.

- Kamu juga dapat mengatur untuk dapat dikomentari oleh orang-orang tertentu saja tanpa harus benar-benar memblokir.

- Kamu dapat menghapus postingan di profilmu atau menyembunyikannya dari orang-orang tertentu.

Di sebagian besar media sosial favoritmu, biasanya orang-orang tidak akan diberitahu saat kamu memblokir, membatasi komentar, atau melaporkan mereka.

Hindari mengirimkan gambar, video ataupun informasi private di social media dengan orang lain. Berpikirlah sebelum membagikan sesuatu yang bersifat pribadi atau pribadi karena tidak ada jaminan bahwa ini tidak akan jatuh ke tangan yang salah. Jika seseorang benar-benar peduli dengan kamu, mereka akan menghormati pilihan kamu untuk tidak memberikan informasi pribadi, foto, atau video.

Beri tahu teman dan keluarga kamu tentang pilihan online kamu. Orang lain tidak akan pernah menghormati privasi kamu, sebagaimana kamu menjaga privasi kamu sendiri. Pastikan teman dan keluarga kamu mengetahui preferensi kamu tentang mengunggah gambar, menandai lokasi, atau berbagi informasi yang kamu harapkan akan dirahasiakan. Ini berfungsi dua arah, jadi pastikan kamu menghormati privasi orang lain dengan cara yang sama.

Waspadai pesan yang mencurigakan Pesan dengan URL singkat di samping pernyataan seperti 'Wah, lihat foto kamu disini…' atau 'Pernahkah kamu melihat apa yang mereka katakan tentang kamu…' tidak+E16 bisa dipercaya.

Email phishing juga menjadi masalah. Ini adalah komunikasi palsu yang berpura-pura menjadi organisasi tepercaya seperti Facebook/Instagram/Twitter yang akan mencoba dan membuat kamu masuk. Mereka dapat terlihat sangat meyakinkan, dan bahkan memiliki info profil pribadi kamu, jadi masuklah ke situs hanya melalui halaman atau aplikasi resmi mereka. Jika ada sesuatu yang mencurigakan, periksa alamat email dan masukkan melalui mesin pencari. Pengirim jahat biasanya diberi nama dan dipermalukan secara online!

- Memiliki password tersendiri di akun yang tidak diketahui oleh orang lain

- Ketika bermain sosial media perlu memahami beberapa etika seperti bagaimana membuat postingan yang baik dalam hal ini tidak menyinggung dan menganggu orang lain

- Tidak menulis atau menyebarluaskan data-data pribadi seperti alamat rumah, nomor telepon, alamat kantor, alamat email, dsb kecuali dalam hal-hal profesional yang telah dilindungi oleh pihak tertentu atau pihak hukum - Tidak memposting atau menyebarluaskan dokumen, foto, rekaman, atau hal-hal lainya yang bersifat pribadi atau perusahaan sehingga segala privasi Anda terjaga

- Tidak menyebarkan informasi yang tidak benar (hoax) yang belum dipastikan kebenarannya kepada khalayak publik

- Tidak memicu keributan, perdebatan, atau mencoba menghina orang lain melalui sosial media yang akan memicu tindak cyberbullying

- Sebisa mungkin memiliki recovery account yang terhubung di nomor HP aktif, alamat email, atau kontak dari keluarga sehingga jika sewaktu-waktu terjadi peretasan akun, Anda bisa segera melakukan recovery

- Hindari berkomunikasi dan bertatap muka dengan orang yang tidak Anda kenal. Selalu meminta pendapat orang tua berkaitan dengan hal ini.

- Saat mendownload suatu file, berupaya untuk memperhatikan hak cipta dari materi, film, jurnal, buku, musi, dan sebagainya sebagai bentuk penghargaan terhadap yang memiliki karya

- Tidak memanggil nama orang lain dengan tujuan mengatakan kata-kata kasar, berbohong tentang mereka atau melakukan perbuatan yang dapat ditafsirkan mencoba untuk menyakiti atau mengintimidasi mereka.

8. Apakah ada hukuman untuk cyberbullying?

UNICEF: Kebanyakan sekolah menanggapi bullying secara serius dan akan mengambil tindakan untuk melawannya. Jika kamu mengalami cyberbullying oleh siswa lain, laporkan ke pihak sekolahmu.

Orang-orang yang menjadi korban segala bentuk kekerasan, termasuk bullying dan cyberbullying , memiliki hak atas keadilan dan meminta pertanggungjawaban pelaku.

Hukum mengenai bullying , khususnya tentang cyberbullying , masih cukup baru dan masih belum ada dimana-mana.

Inilah sebabnya banyak negara masih bergantung pada Undang-Undang lain yang relevan, seperti hukum tentang pelecehan, untuk menghukum pelaku cyberbullying . Di Indonesia, belum ada aturan spesifik yang mengatur tentang cyberbullying, namun ada UU ITE dan juga mengatur ujaran kebencian.

Di negara-negara yang memiliki Undang-Undang khusus tentang cyberbullying , perilaku di dunia maya yang dengan sengaja menyebabkan tekanan secara emosional dipandang sebagai perilaku kriminal. Di beberapa negara ini, korban cyberbullying dapat mencari perlindungan, memutuskan komunikasi dari orang tertentu dan membatasi penggunaan alat elektronik yang digunakan oleh orang tersebut untuk melakukan cyberbullying , secara sementara atau secara permanen.

Namun, penting untuk diingat bahwa hukuman tidak selalu menjadi cara paling efektif untuk mengubah perilaku pembully. Akan lebih baik untuk fokus memperbaiki kerusakan yang ditimbulkan dan mengubah hubungan menjadi lebih positif.

Facebook/Instagram: Di Facebook, ada Standar Komunitas , dan di Instagram, ada Panduan Komunitas yang dapat diikuti oleh penggunanya. Jika ditemukan konten yang melanggar kebijakan ini, seperti kasus bullying atau pelecehan, maka akan dihapus.

Jika menurutmu ada kesalahan dalam penghapusan konten, kamu juga bisa mengajukan banding atau protes. Di Instagram, pengajuan protes atas penghapusan konten atau akun dapat dilakukan melalui Pusat Bantuan . Di Facebook, kamu juga bisa mengajukan proses yang sama melalui Pusat Bantuan .

Cyberbullying dalam konteks penghinaan yang dilakukan di media sosial diatur pada pada Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2008 tentang Informasi dan Transaksi Elektronik (“UU ITE”) sebagaimana telah diubah dengan Undang-Undang Nomor 19 Tahun 2016 tentang Perubahan atas Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2008 tentang Informasi dan Transaksi Elektronik (“UU 19/2016”). Pada prinsipnya, tindakan menunjukkan penghinaan terhadap orang lain tercermin dalam Pasal 27 ayat (3) UU ITE yang berbunyi: “Setiap Orang dengan sengaja dan tanpa hak mendistribusikan dan/atau mentransmisikan dan/atau membuat dapat diaksesnya Informasi Elektronik dan/atau Dokumen Elektronik yang memiliki muatan penghinaan dan/atau pencemaran nama baik”. Adapun ancaman pidana bagi mereka yang memenuhi unsur dalam Pasal 27 ayat (3) UU 19/2016 adalah dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 4 (empat) tahun dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 750 juta. Apabila perbuatan penghinaan di media sosial dilakukan bersama-sama (lebih dari 1 orang) maka orang-orang itu dipidana atas perbuatan “turut melakukan” tindak pidana (medepleger). “Turut melakukan” di sini dalam arti kata “bersama-sama melakukan”. Sedikit-dikitnya harus ada dua orang, orang yang melakukan (pleger) dan orang yang turut melakukan (medepleger) peristiwa pidana.

Di samping itu, secara hukum, seseorang yang merasa nama baiknya dicemarkan dapat melakukan upaya pengaduan kepada aparat penegak hukum setempat, yakni kepolisian. Terkait ini, Pasal 108 ayat (1) dan ayat (6) Undang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1981 tentang Hukum Acara Pidana (“KUHAP”) mengatur: Setiap orang yang mengalami, melihat, menyaksikan dan atau menjadi korban peristiwa yang merupakan tindak pidana berhak untuk mengajukan laporan atau pengaduan kepada penyelidik dan atau penyidik baik lisan maupun tulisan; Setelah menerima laporan atau pengaduan, penyelidik atau penyidik harus memberikan surat tanda penerimaan laporan atau pengaduan kepada yang bersangkutan.

Selain itu, terdapat juga Undang-Undang Nomor 23 Tahun 2002 tentang Perlindungan Anak pasal 80 yang berbunyi, "Setiap orang yang melakukan kekejaman, kekerasan atau ancaman kekerasan, atau penganiayaan terhadap anak, dipidana dengan pidana penjara paling lama 3 (tiga) tahun 6 (enam) bulan dan/atau denda paling banyak Rp 72.000.000,00 (tujuh puluh dua juta rupiah)."

9. Perusahaan internet/media sosial tampaknya tidak peduli dengan cyberbullying dan pelecehan. Apakah mereka sebenarnya bertanggung jawab?

UNICEF : Perusahaan internet semakin memperhatikan masalah bullying di dunia maya.

Banyak dari mereka memperkenalkan cara untuk mengatasinya dan melindungi pengguna mereka dengan lebih baik menggunakan fitur baru, panduan, dan cara untuk melaporkan penyalahgunaan secara online .

Tetapi memang benar bahwa dibutuhkan lebih banyak upaya dan cara. Banyak anak, remaja, dan orang muda mengalami cyberbullying setiap hari. Beberapa mengalami berbagai bentuk penyalahgunaan secara online. Beberapa bahkan telah mengakhiri hidup mereka sendiri sebagai jalan keluar.

Perusahaan teknologi memiliki tanggung jawab untuk melindungi penggunanya terutama anak-anak dan remaja.

Kita semua perlu menuntut pertanggungjawaban jika mereka tidak memenuhi tanggung jawab ini.

Facebook, Instagram, dan Twitter adalah tiga platform media sosial terpopuler. Platform ini menggunakan beberapa metode pencegahan untuk mencegah cyberbullying. Mereka juga menawarkan opsi ketika cyberbullying terjadi, seperti memblokir dan melaporkan pengguna tertentu atau menandai postingan tertentu sebagai agresif. Baik korban maupun saksi bullying dapat melaporkan postingan tersebut.

Namun, platform ini berupaya melindungi kebebasan berbicara. Karena itu, mereka sering ragu untuk menghukum pengguna kecuali jika pelecehannya seperti pornografi anak.

Menurut Statistika, di tahun ini Facebook user sudah mencapai angka lebih dari 2,7 milyar aktif users dan hanya memiliki 15 ribu konten moderator. Konten moderator ini sifatnya terpisah dari sisi pribadi penggunanya, sehingga mengakibatkan situs-situs ini kesulitan menilai maksud jahat dari postingan yang akan mengkategorikannya sebagai cyberbullying.

Cyberbullying bukanlah hal yang dapat diperangi, namun yang bisa dilakukan adalah memberikan dukungan terhadap korban, apabila hal ini terjadi. Perlunya pendidikan dan pemahaman bersocial media yang baik dan benar sangat lah penting dimulai sejak dini dan diajarkan di sekolah, bukan hanya bagaimana cara menggunakan device tecknologi atau menggunakan platform sosial media semata, namun juga etika dan cara berkomunikasi dalam bersosial media itu sendiri.

10. Apakah ada pedoman/sarana/fitur mengenai anti-cyberbullying untuk anak-anak atau orang muda?

UNICEF: Setiap media sosial menawarkan fitur yang berbeda-beda (lihat apa saja yang tersedia di bawah ini) yang memungkinkan kamu untuk membatasi siapa saja yang dapat mengomentari atau melihat postinganmu, atau siapa saja yang dapat terhubung secara otomatis sebagai teman, dan juga untuk melaporkan kasus-kasus bullying . Banyak dari fitur memiliki langkah-langkah sederhana untuk memblokir, mematikan ( mute ), atau melaporkan cyberbullying . Kami menyarankanmu untuk menjelajahinya dan melihatnya satu per satu.

Perusahaan media sosial juga menyediakan fitur dan panduan edukasi untuk anak-anak, orang tua, dan guru untuk belajar mengenai risiko dan cara-cara agar tetap aman saat online .

Juga, garis pertahanan pertama melawan cyberbullying adalah dirimu sendiri. Coba pikirkan tentang dimana cyberbullying dapat terjadi di sekitarmu dan cara apa yang bisa kamu lakukan untuk membantu – dengan menyuarakan pentingnya isu ini, melaporkan bullying , membicarakannya dengan orang dewasa yang terpercaya atau dengan meningkatkan kesadaran akan masalah ini. Bahkan tindakan baik yang sederhana bisa sangat bermanfaat!

Jika kamu khawatir tentang keselamatanmu atau karena sesuatu yang telah terjadi padamu saat bermain internet, segera bicarakan dengan orang dewasa yang kamu percaya. Atau hubungi Telepon Pelayanan Sosial Anak (TePSA) di nomor telepon 1500 771, atau nomor handphone / Whatsapp 081238888002 dan kamu bisa ngobrol dengan konselor profesional yang ramah! Kamu bisa berbicara secara bebas, dan identitasmu bisa dirahasiakan ataupun diungkapkan agar dapat menerima pertolongan.

Facebook/Instagram: Ada sejumlah fitur atau cara untuk membantu menjaga keamanan anak dan remaja:

- Kamu dapat mengabaikan semua pesan dari pembully atau gunakan fitur Restrict atau Batasi , dimana kamu bisa secara diam-diam melindungi akunmu tanpa diketahui oleh orang tersebut.

- Kamu dapat mengaktifkan pengaturan saring komentar untuk postinganmu.

- Kamu dapat mengubah pengaturan sehingga hanya orang yang kamu follow saja yang bisa mengirimkanmu pesan langsung.

- Dan di Instagram, kamu akan diberikan peringatan jika memposting sesuatu yang mungkin melanggar batas, mendorongmu untuk mempertimbangkan kembali.

Untuk tips lebih lanjut tentang cara melindungi diri sendiri dan orang lain dari cyberbullying , lihat berbagai sumber bacaan di Facebook atau Instagram .

Twitter: Jika orang-orang di Twitter menjengkelkan atau negatif, ada fitur yang dapat membantumu, dan daftar berikut memiliki link dengan instruksi cara menggunakannya. Panduan “ Menggunakan Twitter ” memiliki instruksi-instruksi di bawah ini dan masih banyak lagi.

- Mute atau Membisukan – menghapus Tweet sebuah akun dari timeline kamu tanpa unfollowing atau memblokir akun itu

- Memblokir – membatasi akun tertentu agar tidak bisa menghubungi kamu, melihat Tweet kamu, dan juga tidak bisa mem- follow kamu

- Melaporkan – mengajukan laporan terhadap perilaku yang kasar atau menghina

Cari tahu cara aman berinternet di sini

Kontribusi para pakar dari: Sonia Livingstone, OBE, Professor Social Psychology, Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics; Professor Amanda Third, Professorial Research Fellow, Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, Bully.id, Think Before Type

Terima kasih secara khusus kepada: Facebook, Instagram, dan Twitter.

Kontribusi UNICEF: Mercy Agbai, Stephen Blight, Anjan Bose, Alix Cabral, Rocio Aznar Daban, Siobhan Devine, Emma Ferguson, Nicole Foster, Nelson Leoni, Supreet Mahanti, Clarice Da Silva e Paula, Michael Sidwell, Daniel Kardefelt Winther.

Terjemahan dan adaptasi ke Bahasa Indonesia: Derry Ulum

Sumber referensi

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Glob Health Action

- v.12(1); 2019

The development and pilot testing of an adolescent bullying intervention in Indonesia – the ROOTS Indonesia program

a Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Farida Aryani

b Department of Research, Yayasan Indonesia Mengabdi, Jakarta, Indonesia

Faridah Ohan

Rina herlina haryanti.

c Department of Public Administration, Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta, Indonesia

Sri Winarna

d Deputy for Child Rights and Protection, Office of Women Empowerment and Child Protection Central Java, Central Java, Indonesia

Yuli Arsianto

Hening budiyawati.

e Deputy for Programme Section, Yayasan Setara, Semarang, Indonesia

Evi Widowati

f Department of Public Health, State University of Semarang, Semarang, Indonesia

Rika Saraswati

g Department of Environmental and Urban Studies, Soegijapranata Catholic University, Semarang, Indonesia

Yuliana Kristianto

h Department of Public Administration, Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia

Yulinda Erma Suryani

i Department of Psychology, Klaten Widya Dharma University, Klaten, Indonesia

Derry Fahrizal Ulum

j Child Protection Section, UNICEF Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

Emilie Minnick

Associated data.

- Bank TW. World bank and education in Indonesia 2014 . Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/brief/world-bank-and-education-in-indonesia

Bullying has been described as one of the most tractable risk factors for poor mental health and educational outcomes, yet there is a lack of evidence-based interventions for use in low and middle-income settings. We aimed to develop and assess the feasibility of an adolescent-led school intervention for reducing bullying among adolescents in Indonesian secondary schools. The intervention was developed in iterative stages: identifying promising interventions for the local context; formative participatory action research to contextualize proposed content and delivery; and finally two pilot studies to assess feasibility and acceptability in South Sulawesi and Central Java. The resulting intervention combines two key elements: 1) a student-driven design to influence students pro-social norms and behavior, and 2) a teacher-training component designed to enhance teacher’s knowledge and self-efficacy for using positive discipline practices. In the first pilot study, we collected data from 2,075 students in a waitlist-controlled trial in four schools in South Sulawesi. The pilot study demonstrated good feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. We found reductions in bullying victimization and perpetration when using the Forms of Bullying Scale. In the second pilot study, we conducted a randomised waitlist controlled trial in eight schools in Central Java, involving a total of 5,517 students. The feasibility and acceptability were good. The quantitative findings were more mixed, with bullying perpetration and victimization increasing in both control and intervention schools. We have designed an intervention that is acceptable to various stakeholders, feasible to deliver, is designed to be scalable, and has a clear theory of change in which targeting adolescent social norms drives behavioral change. We observed mixed findings across different sites, indicating that further adaptation to context may be needed. A full-randomized controlled trial is required to examine effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the program.

Aggressive behaviors among youth, including violence and bullying, are associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders across the life-course, poor social functioning and educational outcomes [ 1 , 2 ]. The high worldwide prevalence rates and potential for harm makes addressing such behaviors a public health priority – yet one that is too often neglected. The World Health Organization considers bullying to be a major adolescent health problem, defining such acts as the intentional use of physical or psychological force against others [ 3 ]. Research predominately originates from high-income settings, yet peer violence has been found to increase risk for poor mental health and risk taking behaviors, and is associated with earlier school drop out in multiple low and middle-income settings [ 4 ].

Schools play a central role in young people’s lives that go far beyond education, and help shape social, emotional and behavioral development. Educational engagement and academic attainment are closely connected with behavioral risk factors that influence major adolescent health problems, including bullying and peer violence [ 5 ]. Prevention and health promotion activities in secondary schools have great potential for promoting engagement and student wellbeing through fostering positive and healthy school climates that reduce aggressive behaviors among youth. Systematic reviews suggest that complex, whole-school interventions are effective at reducing victimization and bullying in high-income settings [ 6 – 8 ]. Whole-school multi-method approaches include combinations of school-wide rules and sanctions, teacher training, classroom rules, conflict resolution training and individual counseling [ 8 ]. Whole-school approaches have been shown to be most successful at reducing bullying compared to interventions targeting only one level of the problem (e.g. compared to interventions targeting only classroom-level rules against bullying, or individual-level training such as social skills groups [ 8 ]. Whole-school interventions take a socio-ecological approach to bullying by involving bullies, victims, peers, adults, and parents and by making substantial changes to the wider school environment. In a recent meta-analysis of school-based anti-bullying programs [ 6 ], the most important components that were associated with a decrease in bullying included parent training, school conferences, videos, information for parents, improved playground supervision, disciplinary methods, work with peers, classroom rules and classroom management. In addition, the total number of components and the duration and intensity of the program for children and teachers were significantly associated with a decrease in bullying. This is in keeping with the finding of a dose-response relationship between the number of components implemented in school-based interventions and the effect on bullying [ 9 ]. More recently, anti-bullying programs such as the Kiva project have highlighted the importance of including ‘bystanders’ – children who witness bullying behaviors but who are not actively involved – into anti-bullying initiatives [ 10 , 11 ].

Whole-school interventions are often expensive to implement, involve substantial staff training, and have only been trialed in high-income settings, where student-staff ratios are relatively low and school resources are relatively high. A recent low-cost and simple randomized intervention, ‘Roots’ [ 12 ], implemented in 56 schools (24,191 students) in the United States used a student-driven design to influence anti-conflict social norms and behavior, reducing overall levels of school conflict by 25%. Such interventions are based upon theories that individuals observe the behavior of certain people in their community to understand what is socially normative and adjust their own behavior in response. Adolescent ‘social referents’ who have an enhanced influence over school climate or the social norms and behavioral patterns in their schools are identified, and encouraged to take a public stance against peer violence and bullying. Critically, this type of intervention is low-cost, simple to implement, and utilizes existing social network structures to maximize intervention efficacy and impact rather than involving changes to school curricula or school management time. Such an approach has a high potential for settings that lack sufficient resources to implement current anti-bullying interventions.

The Indonesian context

The Indonesian school system is both diverse and vast. With over 50 million students and 2.6 million teachers in more than 250,000 schools, it is the third largest education system in the Asia region and the fourth largest in the world (behind only China, India and the United States) [ 13 ]. Net enrollment rates for secondary education have increased steadily in recent years, with average junior-secondary enrolment currently standing at over 80%, and gender parity has also been achieved at this level, although disparities persist across regions and socio-economic groups [ 14 ].

Indonesia continues to perform poorly relative to other countries in the region in terms of standardized international tests as indicated by the OECD Program for International Student Assessments or PISA 2015 report, where Indonesia ranked 62 out of 72 included countries [ 15 ]. Improving educational outcomes remains a huge challenge for the Government. Pupil to Teacher ratios have risen sharply at the secondary level since 2010–2011, and there are considerable variations in pupil to teacher ratios across Indonesia’s districts and regions.

Nationally representative data on bullying from the Global School Health Survey (GSHS) in 2015 suggests that over 20% of Indonesian children in grades 7–9 reported experiencing bullying in the last month [ 16 ]. Despite this, no evidence-based anti-bullying interventions have been evaluated in Indonesia. There is a strong national commitment to eliminate all forms of violence, including bullying, in schools in Indonesia, as highlighted by the Child Friendly Schools initiative, the Prevention and Elimination on Violence in Schools National Strategy, and the Elimination of Violence against Children 2016–2020 [ 17 ]. These strategies include a focus on changing the current social norms that accept, tolerate, and ignore violence, including at school settings.