Umbrella Reviews: What They Are and Why We Need Them

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology, University of Ioannina Medical School, Ioannina, Greece.

- 3 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Imperial College London, London, UK.

- PMID: 34550588

- DOI: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1566-9_8

Evidence in clinical research is accumulating and scientific publications have increased exponentially in the last decade across all disciplines. Available information should be critically assessed. Here, we focus on umbrella reviews, an approach that systematically collects and evaluates information from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses. To facilitate the design and the conduct of such a study, we provide a step-by-step guide on how to perform an umbrella review. We also present ways to report the summary findings, we describe various proposed grading criteria, and we discuss potential limitations.

Keywords: Assessment of evidence; Meta-analysis; Systematic review; Umbrella review.

© 2022. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature.

- Publications*

- Review Literature as Topic*

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Publish with us

- About the journal

- Meet the editors

- Specialist reviews

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 1, Issue 1

- Conducting umbrella reviews

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2334-6974 Lazaros Belbasis 1 ,

- Vanesa Bellou 2 and

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3118-6859 John P A Ioannidis 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7

- 1 Meta-Research Innovation Center Berlin, QUEST Center, Berlin Institute of Health , Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin , Berlin , Germany

- 2 Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology , University of Ioannina Medical School , Ioannina , Greece

- 3 Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford , Stanford University , Stanford , CA , USA

- 4 Department of Medicine , Stanford University Medical School , Stanford , CA , USA

- 5 Department of Epidemiology and Population Health , Stanford University Medical School , Stanford , CA , USA

- 6 Department of Health Research and Policy , Stanford University Medical School , Stanford , CA , USA

- 7 Department of Biomedical Data Science , Stanford University Medical School , Stanford , CA , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Lazaros Belbasis, Clinical Trials Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; lazaros.belbasis{at}ndph.ox.ac.uk

In this article, Lazaros Belbasis and colleagues explain the rationale for umbrella reviews and the key steps involved in conducting an umbrella review, using a working example.

- research design

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmed-2021-000071

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Key messages

An umbrella review is a systematic collection and assessment of multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses on a specific research topic

Umbrella reviews were developed to deal with the increasing number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in biomedical literature

The validity of umbrella reviews depends on the coverage and quality of both the primary studies and the available systematic reviews and meta-analyses

The key output of umbrella reviews is a systematic and standardised assessment of all the evidence on a broad but well defined research topic (eg, treatment effects of multiple interventions for a particular disease, or adjusted or unadjusted associations of multiple risk factors with a particular disease) based on published systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Introduction

Currently, clinical researchers have used systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRMAs) for most clinical and epidemiological questions of interest. Occasionally, researchers might need to examine the evidence not just on a single question but on several different questions on a given topic. Umbrella reviews (ie, a systematic review of SRMAs) could be an appropriate option for these situations.

Definition and scope of umbrella reviews

Umbrella reviews are systematic collections and assessments of multiple SRMAs done on a specific research topic. 1 2 The decision to perform an umbrella review depends on the number of available SRMAs ( figure 1 ). An umbrella review is informative when multiple SRMAs have already been published on a specific research topic. When only a trivial number of relevant SRMAs are available, performing a new SRMA is more appropriate and more informative. When multiple outdated SRMAs are available, updating the existing SRMAs is more important. Like all research studies, umbrella reviews have advantages and disadvantages ( box 1 ).

Advantages and disadvantages of umbrella reviews

They offer a bird eye’s view of multiple interventions for a specific medical condition or multiple epidemiological associations for a specific medical condition (exposure wide approach) or a specific risk factor (phenome wide approach)

They save valuable research resources by avoiding systematic searches from scratch, because they take advantage of existing systematic reviews

They identify the gaps in a specific research field and can inform recommendations for further research

They present an overview of study quality, effect sizes, uncertainty, heterogeneity, and hints of bias across a well defined but broad research field

They present and compare evidence between different interventions or different epidemiological associations, providing a comprehensive picture about the relative strengths and weaknesses of the evidence for each intervention or epidemiological association

Disadvantages

The validity of umbrella review findings depends on the quality of the eligible systematic reviews and meta-analyses

They do not include information for interventions or epidemiological associations that have not been examined in systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Quality problems and biases might also exist in primary studies and in the umbrella review process itself, and these problems and biases could be compounded and difficult to clarify

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Decision process regarding whether to perform an umbrella review. SRMA=systematic review and meta-analysis

The two most common applications of umbrella reviews deal with treatment effects of interventions and epidemiological associations of exposures. Umbrella reviews of interventions typically focus on one or more diseases of interest and assess SRMAs on the treatment effects of all interventions for those diseases. 3 Umbrella reviews of epidemiological associations often follow either a phenome wide approach or an exposure wide approach. In the phenome wide approach, researchers consider the (adjusted or unadjusted) associations of a particular risk factor with any disease or phenotype. 4 In the exposure wide approach, researchers consider the (adjusted or unadjusted) associations of multiple risk factors with a specific disease or phenotype. 5–7 Umbrella reviews can also be designed to summarise SRMAs on other types of studies, such as prevalence studies and diagnostic accuracy studies. 8 9 From a clinical point of view, the key output of an umbrella review is a comprehensive, systematic, and critical summary of multiple intervention or epidemiological studies (or other types of studies) based on published SRMAs.

Getting started

As a working example, we will use an umbrella review summarising SRMAs on the non-genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus, which included 86 eligible articles (142 epidemiological associations) of SRMAs. 10 With so many factors being examined for association with risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, an umbrella review can obtain a bird eye’s view of the evidence on unadjusted or adjusted effects between particular risk factors and onset of the disorder, in terms of measures such as odds ratios and hazard ratios.

Key steps in umbrella reviews

Umbrella reviews have several steps ( figure 2 ), of which four are key: systematic literature search and study selection, data extraction, statistical analysis and grading of evidence, and interpretation of findings.

Key steps in an umbrella review

Researchers need to clearly define the research question of interest and consider which SRMAs are to be included by explicitly stating the eligibility criteria ( box 2 ). A search algorithm must then be constructed to capture all SRMAs that deal with the defined research area. Eligible SRMAs are then selected by independent double screening of the literature search results. When multiple SRMAs on the same topic have partial or complete overlap, criteria are applied to decide which SRMAs to include. 11 12 There are no set criteria, but researchers can choose the most recent meta-analysis, the meta-analysis with the largest number of studies, or (for epidemiological associations) the meta-analysis with the largest number of prospective studies. Researchers should also consider the quality of the SRMAs when deciding which to prioritise. In our working example for type 2 diabetes mellitus, the researchers chose the SRMA with the largest number of prospective studies, because prospective studies guarantee temporality in epidemiological associations.

Eligibility criteria, search algorithm, and data extraction in umbrella reviews

Eligibility criteria.

In the definition of eligibility criteria, researchers can follow the PICO characteristics (population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes) for umbrella reviews of interventions. For umbrella reviews of epidemiological associations (either predictive or causal factors), researchers should also define the population(s), risk factor(s), and outcome(s) of interest to consider. By contrast with a single SRMA (systematic review and meta-analysis), umbrella reviews have much broader criteria, but the exact breadth should be carefully defined to ensure that the umbrella review is informative and comprehensive from a clinical or scientific perspective. In our working example, the population of interest was individuals not having type 2 diabetes mellitus at the beginning of the study, the risk factors of interest were any non-genetic factors, and the outcome was the development of the disorder.

Search algorithm

For an umbrella review, the search algorithm consists of two parts. The first part aims to identify research articles that are systematic reviews or meta-analyses (eg, using the keywords "systematic review*" OR meta-analys*). Alternatively, other search strings that aim to maximise retrieval of SRMAs could be used. The second part of the search algorithm should capture all the relevant articles about the research question. For this reason, this step should include all the relevant keywords about the research topic of interest; in this task, the inclusion of MeSH terms could facilitate capturing all the relevant terms. In our working example, the researchers used the keyword "diabetes" to capture articles relevant to type 2 diabetes mellitus. 10 The final search algorithm is derived by combining the two parts of the algorithm using the boolean operator AND. Recommendations on database combinations to retrieve systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on empirical data have been published. 17

Data extraction

In the data extraction process, for systematic reviews without a meta-analysis, the researchers should extract the number of eligible studies, the total sample size and (for binary outcomes) the number of events, the rationale for not performing a meta-analysis, and the descriptive conclusions. For systematic reviews with a meta-analysis, researchers should extract the number of eligible studies, the total sample size and (for binary outcomes) the total number of events, the study specific sample sizes and (for binary outcomes) the study specific numbers of events, the study specific effect estimates with relevant 95% confidence intervals, and the qualitative assessment as presented by the eligible SRMAs (if available).

Once the SRMAs to be included are agreed, two researchers should independently extract the required data from each eligible SRMA using a standardised data extraction form ( box 2 ). With regards to the statistical analysis, researchers should use the study specific data extracted from each SRMA to repeat each meta-analysis separately rather than report the meta-analytical result as presented in the original SRMA. This process is important, because published SRMAs often use inappropriate meta-analytical statistical models, or they do not assess the heterogeneity between studies or the presence of small study effects. By re-running each meta-analysis, researchers can use the same array of methods for all considered meta-analyses and perform various heterogeneity or bias tests. To perform all the statistical analyses, researchers should extract data on study specific effect estimates with the relevant uncertainty estimates and the relevant sample sizes (as reported by the eligible SRMAs). However, some SRMAs offer insufficient information to perform all the desired, standardised analyses; this should be noted and discussed. In that case, researchers might decide to extract the required data from the primary studies.

After running the statistical analyses, researchers should assess the strength of the evidence. For questions about interventions (eg, drug treatments and other interventions in healthcare), researchers can use a validated tool, such as GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations), to assess the strength of the evidence. 13 For epidemiological associations, researchers can make an assessment of the strength of the evidence by considering several features including amount of evidence, level of significance, extent of heterogeneity between studies, and hints for potential bias (eg, small study effects, and excess significance bias) in each meta-analysis. 5 6 An empirical evaluation of 57 umbrella reviews (including 3744 meta-analyses of observational studies) with a set of such criteria was recently published and shows that these criteria provide largely independent, complementary information. 14 Researchers can also examine the temporality of epidemiological associations by performing the same assessment focusing only on prospective studies. In the working example for type 2 diabetes mellitus, the researchers graded the epidemiological associations using a predefined set of criteria. They then examined whether the most credible associations maintained their ranking in a sensitivity analysis of prospective studies.

After performing the statistical analyses and grading the strength of the evidence, researchers should report their results. Reporting might be similar to relevant reporting guidelines of systematic reviews for observational or randomised studies (ie, MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology), and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses)). 15 16 The difference is that the building block here is not one primary study, but a systematic review or meta-analysis.

A flowchart of literature search and study selection is helpful. Authors should report the eligible SRMAs identified, and those excluded because of overlap. For systematic reviews without statistical synthesis, researchers could state why meta-analysis was not performed and main conclusions. The findings of an umbrella review can be reported in both tabular and graphical format. Tables summarising all meta-analyses with some key features and results, and the grading of strength of the evidence for assessed interventions or associations are essential ( box 3 ). Furthermore, if some SRMAs present a risk-of-bias assessment using standardised tools (eg, Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for observational studies, or Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised clinical trials), researchers can summarise the risk-of-bias assessment in each eligible SRMA using a tabular format. Additionally, visual plots can also facilitate the presentation and interpretation of results, such as the distribution of effect sizes and P values across the primary studies, or the distribution of summary effect sizes, P values, and heterogeneity estimates across the meta-analyses. In the working example on risk factors for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus, the researchers presented their results in both tabular and graphical format. They visually presented their results by providing a forest plot of the summary effect estimates for the meta-analyses with the highest strength of evidence, and a Manhattan plot (depicting the distribution of all P values in a −log 10 format). 10

Summarising results from multiple meta-analyses in umbrella reviews

Several key features and results of each meta-analysis should be reported, as shown below. In the working example of an umbrella review on type 2 diabetes mellitus, all the items listed below were provided in a tabulated manner for all the eligible meta-analyses (a total of 142 epidemiological associations) 10 :

Total number of cases or events (for binary outcomes)

Total sample size

Number of studies

Effect size metric

Meta-analysis method used (fixed effect or random effects, and related variants)

Summary effect estimate

95% confidence interval

95% prediction interval

P value for the summary effect estimate

Heterogeneity (eg, P value from Cochran’s Q test, I 2 , or estimate of variance between studies)

Effect size estimate of the largest study with the relevant 95% confidence interval

Suggestions of bias in relevant tests (eg, presence of small study effects and excess significance).

After reporting the results, the next step is interpretation. For umbrella reviews of interventions, interpretation should consider clinical relevance (including absolute risk reductions), potential additional biases in the design and conduct of randomised clinical trials and their meta-analyses, and issues of generalisability. For umbrella reviews of epidemiological associations, traditional considerations of confounding, reverse causality, selection bias, and information bias should be carefully considered either for all examined associations, or for a subset of associations (eg, the ones that seem to have the highest strength of evidence). Causal claims are notoriously difficult and typically only tentative. In our working example, the researchers interpreted the findings of the umbrella review by discussing the biological plausibility of the observed associations, and by systematically collecting published mendelian randomisation studies for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Potential challenges

Conducting an umbrella review has some potential challenges. Umbrella reviews can deal with a topic comprehensively when primary studies and SRMAs have full coverage of the topic, otherwise gaps in the evidence can exist. The validity of an umbrella review depends on the quality of both the primary studies and the existing SRMAs. Cross checking the original reports to confirm whether all the data extraction for all the eligible SRMAs is correct would be impossible. But occasionally, umbrella review authors should go back to original reports to collect additional information (eg, sample size, and number of cases) to allow performing calculations in a standardised way and assessing criteria for strength of the evidence. Moreover, if some data are deemed spurious, the original reports should also be examined to remove errors. Moreover, SRMAs often might use eligibility criteria that deviate from what is intended in the umbrella review. For example, the umbrella review might wish to focus only on randomised trials, but the existing SRMAs might also contain observational studies that should be separated.

Clinicians and other readers should search for specific characteristics indicating a good quality umbrella review. They should explicitly state their eligibility criteria, verifying that these criteria fit with their clinical question; repeat the statistical analyses to estimate all the relevant features about heterogeneity between studies, 95% prediction intervals and related statistical biases; and grade the evidence according to a set of criteria and discuss various other potential biases.

Conclusions

Umbrella reviews can provide a bird eye’s view of the currently available evidence on broad research topics and a thorough assessment of strength of the available evidence, and they can indicate potential priorities for future research. Clinicians and other users should look to umbrella reviews for a systematic and critical summary of the evidence in a broad research topic (eg, multiple risk factors or predictors for a particular disease, multiple health related effects of an exposure, or multiple interventions for a particular disease). From an epidemiological perspective, the findings of an umbrella review can be used to identify which epidemiological associations could get tested further using more sophisticated causal inference methods, such as mendelian randomisation. From a clinical perspective, the findings of an umbrella review can be used by clinicians and trialists to inform the design of preventative or therapeutic interventions through randomised clinical trials.

In our working example, the researchers eventually summarised and assessed the evidence on 142 epidemiological associations. 10 By contrast with relevant narrative reviews on risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus that selectively report some associations, this umbrella review captured all the relevant SRMAs in a systematic manner. Furthermore, SRMAs usually focus on the presence of a significant effect, whereas the umbrella review example also considered issues related to heterogeneity between studies, confounding, and other biases. In our working example, 116 of 142 epidemiological associations presented a significant effect at P<0.05. However, only 11 presented strong evidence based on a set of criteria that consider level of significance, heterogeneity between studies, 95% prediction intervals, small study effects, and excess significance bias. An important advantage of this umbrella review is that readers can see that specific risk factors have the strongest evidence while others also have strong support, and they can observe the relative magnitude of all the associations.

- Ioannidis JPA

- Belbasis L ,

- Evangelou E , et al

- Tonelli AR ,

- Adams J , et al

- Savvidou MD ,

- Kanu C , et al

- Tzoulaki I , et al

- Mavrogiannis MC ,

- Emfietzoglou M , et al

- Ryder S , et al

- Sambrook Smith M ,

- Pullen LSW , et al

- Siontis KC ,

- Hernandez-Boussard T ,

- Sigurdson MK ,

- Khoury MJ ,

- Guyatt GH ,

- Vist GE , et al

- Janiaud P ,

- Agarwal A ,

- Stroup DF ,

- Berlin JA ,

- Morton SC , et al

- Liberati A ,

- Tetzlaff J , et al

- Goossen K ,

- Lunny C , et al

Twitter @Lazaros_B

Contributors LB, VB, and JPAI have extensive experience in the design, conduct, and reporting of umbrella reviews. LB and VB wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and JPAI critically commented on this. LB, VB, and JPAI wrote and approved the final version of the manuscript. LB is the guarantor of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient and public involvement Patients and the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Umbrella reviews: a...

Umbrella reviews: a useful study design in need of standardisation

Linked research in bmj medicine.

Environmental risk factors for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Related content

- Peer review

- Xiaoting Shi , doctoral student ,

- Joshua D Wallach , assistant professor

- Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which identify and synthesise evidence from individual studies, are often believed to provide an overview of the best available evidence on a specific research question. In epidemiology, however, systematic reviews and meta-analyses typically focus on individual exposure to outcome relationships, which can fail to capture all potentially related exposures or outcomes across an entire field. Moreover, concerns have consistently been raised about the growing number of overlapping and conflicting reviews. 1 2 These limitations emphasise the need for a study design that can potentially provide a higher level synthesis of summary level evidence. 1 2

Umbrella reviews, which are also known as overviews of systematic reviews or systematic reviews of meta-analyses, summarise the spread and strength of associations reported in previously conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 3 They can consider numerous exposures and outcomes; provide an assessment of the impact of sample size, heterogeneity, and hints of bias on summary associations; and evaluate the quality of individual systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These evaluations, which have increased in popularity over the past decade, 4 are particularly useful in fields where a large number of reviews have already been conducted.

In our recent umbrella review published in BMJ Medicine , we identified and summarised all associations reported in meta-analyses on environmental exposures and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). 5 Although many exposures (such as dietary, clinical, lifestyle, chemical, and occupational factors) have been the focus of separate meta-analyses, little is known about the accumulated evidence across a range of potential environmental exposures and NHL subtypes. Across 85 meta-analyses reporting 257 unique environmental exposure-NHL associations, we found that most meta-analyses were low quality and presented either non-significant or weak evidence. 6 Only one association—history of coeliac disease and risk of NHL—was classified as presenting convincing evidence. Although our study suggests the need for improving not only primary studies but also evidence synthesis in this field, it also highlights several challenges of conducting umbrella reviews without uniform handbooks and reporting guidelines.

Firstly, it can be challenging to select an individual meta-analysis when there are overlapping meta-analyses for the same exposure-outcome relationships. While some umbrella reviews select the largest or most recent meta-analyses, 7 8 9 10 others prioritise those with the greatest precision 11 or the highest quality. 12 Some umbrella reviews even go as far as updating the individual searches from each eligible meta-analysis. 12 In our evaluation, we selected a single association from the largest meta-analyses on each topic, even though there may have been more recent or higher quality meta-analyses. We selected this approach given the large number of identified associations.

Secondly, individual meta-analyses often report multiple associations for different exposure contrast levels (such as exposed versus unexposed, high versus low levels of exposure, or dose-response), which can make it difficult to select and summarise only one association. When designing our study, we found that while some umbrella reviews justified why certain comparisons were selected, others primarily selected exposed versus unexposed comparisons. 13 14 In our evaluation, we prioritised the associations from exposed versus unexposed comparisons. When these comparisons were not reported, however, we also recorded any associations from comparisons of high versus low levels of exposures. Although this approach may not have captured the complexities of all higher exposure levels, our objective was to provide a manageable overview of all reported exposures across a large field.

Thirdly, different methodological approaches can be used in umbrella reviews to assess the credibility of individual associations from meta-analyses, including the role of statistical significance, sample size, heterogeneity, and certain biases. 10 13 15 16 Many umbrella reviews, including our own, used the same methods to conduct the analyses for each of these characteristics. 8 17 However, the current methods could be modified (such as standardising all associations using different meta-analytical methods), 18 19 which could ultimately impact how evidence is classified.

Overall, our experience suggests that there are opportunities to improve the design, conduct, and reporting of umbrella reviews, to help ensure that these studies are rigorous and reproducible. Unlike traditional systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which have more established methodology and reporting guidelines, 20 21 the recommendations for umbrella reviews are disjointed, with separate efforts outlining various concerns and recommendations. 22 23 24 25 26 The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Joanna Briggs Institute Manual provide recommendations for umbrella reviews of interventions, 27 28 but additional resources are needed to accommodate different scenarios. Together, these efforts could help standardise approaches, minimise the need for authors to make subjective decisions, and ultimately reduce the number of overlapping umbrella reviews that are conducted using different methodological approaches. 29

Competing interests: In the past 36 months XS was supported by the China Scholarship Council and the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. JDW currently receives research support through Yale University from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Food and Drug Administration, and from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under award K01AA028258.

- Ioannidis JP

- Ioannidis J

- Bougioukas KI ,

- Vounzoulaki E ,

- Mantsiou CD ,

- Reeves BC ,

- Belbasis L ,

- Evangelou E ,

- Ioannidis JP ,

- Timofeeva M ,

- Theodoratou E ,

- Tzoulaki I ,

- Ramella-Cravaro V ,

- Ioannidis JPA ,

- Gasevic D ,

- Chandan JS ,

- Marshall T ,

- Schwingshackl L ,

- Knüppel S ,

- Schwedhelm C ,

- Kyrgiou M ,

- Kalliala I ,

- Markozannes G ,

- Higgins JPT ,

- Jackson D ,

- IntHout J ,

- Liberati A ,

- Tetzlaff J ,

- Altman DG ,

- PRISMA Group

- Stroup DF ,

- Berlin JA ,

- Morton SC ,

- Pollock M ,

- Fernandes RM ,

- Becker LA ,

- Featherstone R ,

- Guitard S ,

- Fusar-Poli P ,

- Aromataris E ,

- Fernandez R ,

- Godfrey CM ,

- Tungpunkom P

- ↵ Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: umbrella reviews. 2020. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL .

- ↵ Pollock M, Fernandes MR, Becker AL, Pieper D, Hartling L. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: overviews of reviews. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-v .

- Neelakant T ,

Gerstein Science Information Centre

Knowledge syntheses: systematic & scoping reviews, and other review types.

- Before you start

- Getting Started

- Different Types of Knowledge Syntheses

- Assemble a Team

- Develop your Protocol

- Eligibility Criteria

- Screening for articles

- Data Extraction

- Critical appraisal

- What are Systematic Reviews?

- What is a Meta-Analysis?

- What are Scoping Reviews?

- What are Rapid Reviews?

- What are Realist Reviews?

- What are Mapping Reviews?

- What are Integrative Reviews?

When is an Umbrella Review methodology appropriate?

Elements of an umbrella review, methods and guidance.

- Standards and Guidelines

- Supplementary Resources for All Review Types

- Resources for Qualitative Synthesis

- Resources for Quantitative Synthesis

- Resources for Mixed Methods Synthesis

- Bibliography

- More Questions?

- Common Mistakes in Systematic Reviews, scoping reviews, and other review types

Booth (2016) states that "essentially an umbrella review is a cluster of existing systematic reviews on a shared topic" (p. 37). Umbrella reviews are also known as an overview of reviews. According to Grant & Booth (2009) , umbrella reviews are "overarching reviews" that "agreggrat[e] findings from several reviews that address specific questions" (p. 103). Moreover, "each umbrella review focuses on a broad condition or problem for which there are two or more potential interventions and highlights reviews that address these potential interventions and their results" ( Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 103 ).

When to Use It: Umbrella reviews are best suited for topics which are already addressed in systematic and/or meta-analyses. Grant & Booth (2009) state that umbrella reviews are useful for combining the results of various reviews on a certain question. Booth (2016) adds that:

"Typically, the broad topic area will have been “split” into focused populations and/or interventions. The umbrella review seeks to impose an overall coherence by lumping these precise reviews together. Umbrella reviews are particularly valuable within health technology assessments that aim to consider all management options and yet may commission separate reviews of an individual treatment with specific outcomes" (p. 37).

Becker et al. (n.d) add that as there may be many possible interventions for a specific condition, it is beneficial for decision-makers to save time reviewing individual reviews and rather read an umbrella or overview of reviews that cover all possible interventions. An umbrella review can point at reviews that address different types of interventions.

The following characteristics, strengths and challenges of conducting umbrella reviews are derived from Becker et al. (n.d) , Booth (2016) and Grant & Booth (2009) .

Characteristics:

An umbrella review is essentially a single document that includes evidence from a variety of Cochrane reviews

An umbrella review can only be accomplished if the intervention of interest has already been discussed in a review

Provides a useful and quick overview of reviews for a particular topic as well as all the relevant reviews on that topic

Grant & Booth (2009) state that umbrella reviews "are a response, and potential solution, to the perennial dilemma reviewers face regarding 'lumping' versus 'splitting', i.e. whether the needs of a particular field or area are best addressed by a broad review...or by a succession of focused reviews" (p. 103)

They "build upon an area that is well-covered by existing systematic reviews by synthesizing the evidence from all relevant reviews to provide a single report which summarizes the current state of knowledge on the topic" (Booth, 2016, p. 37)

Umbrella reviews can "bring together many treatment comparisons for the management of the same disease or condition" (Booth, 2016, p. 37)

Weaknesses:

An umbrella review cannot be completed without pre-existing reviews

Limitations involve "the amount, quality and comprehensiveness of available information in the primary studies" (Booth, 2016, p. 37)

The following resource provides further support on conducting an umbrella review:

METHODS & CONDUCT

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer's Manual. Chapter 10: Umbrella Reviews

An extensive and detailed outline within the JBI Reviewer's Manual on how to properly conduct an umbrella review.

- Cochrane Handbook Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews.

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

- Methodology for JBI umbrella reviews

A comprehensive paper outlining the methodology in conducting umbrella reviews, from the Joanna Briggs Institute.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Check out the supplementary resources page for additional information, including articles, on umbrella reviews.

- << Previous: What are Integrative Reviews?

- Next: Tools >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 1:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/systematicreviews

Library links

- Gerstein Home

- U of T Libraries Home

- Renew items and pay fines

- Library hours

- Contact Gerstein

- University of Toronto Libraries

- UT Mississauga Library

- UT Scarborough Library

- Information Commons

- All libraries

© University of Toronto . All rights reserved.

Connect with us

Umbrella reviews: what they are and why we need them

- Published: 09 March 2019

- Volume 34 , pages 543–546, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Stefania Papatheodorou 1 , 2

3919 Accesses

81 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–2.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ioannidis JP. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94(3):485–514.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Silagy CA, Middleton P, Hopewell S. Publishing protocols of systematic reviews: comparing what was done to what was planned. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2831–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Moher D, A Liberati, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Salanti G, Ioannidis JP. Synthesis of observational studies should consider credibility ceilings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(2):115–22.

Ioannidis JP. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ. 2009;181(8):488–93.

Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J. Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ. 2017;359:j5024.

Machado MO, Veronese N, Sanches M, Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Thompson T, et al. The association of depression and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):112.

Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Middleton LT, Ioannidis JPA, Evangelou E. Systematic evaluation of the associations between environmental risk factors and dementia: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Alzheimer’s Dement J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2017;13(4):406–18.

Article Google Scholar

Houze B, El-Khatib H, Arbour C. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for chronic pain: an umbrella review on various CAM approaches. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;79(Pt B):192–205.

Corso E, Hind D, Beever D, Fuller G, Wilson MJ, Wrench IJ, et al. Enhanced recovery after elective caesarean: a rapid review of clinical protocols, and an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):91.

Giannakou K, Evangelou E, Papatheodorou SI. Genetic and non-genetic risk factors for pre-eclampsia: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol: Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(6):720–30.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Solmi M, Correll CU, Carvalho AF, Ioannidis JPA. The role of meta-analyses and umbrella reviews in assessing the harms of psychotropic medications: beyond qualitative synthesis. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2018;27(6):537–42.

Kohler CA, Evangelou E, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N, Belbasis L, et al. Mapping risk factors for depression across the lifespan: an umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses and Mendelian randomization studies. J Psychiatry Res. 2018;103:189–207.

Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19(22):3127–31.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tsilidis KK, Papatheodorou SI, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of excess statistical significance in meta-analyses of 98 biomarker associations with cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(24):1867–78.

Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, Ioannidis JP. Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g2035.

Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. An exploratory test for an excess of significant findings. Clin Trials. 2007;4(3):245–53.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

Stefania Papatheodorou

Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol, Cyprus

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefania Papatheodorou .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Papatheodorou, S. Umbrella reviews: what they are and why we need them. Eur J Epidemiol 34 , 543–546 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00505-6

Download citation

Received : 15 February 2019

Accepted : 22 February 2019

Published : 09 March 2019

Issue Date : 15 June 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00505-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Types of Reviews

In this guide.

- Common Types of Reviews

- Narrative Reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Rapid Reviews

- Umbrella Reviews

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Full Infographic Series

What are they?

An Umbrella Review is essentially a review of reviews. Umbrella Reviews are designed to synthesize evidence from other published systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses on a broad topic.

The JBI Handbook includes a chapter on umbrella reviews .

How long might it take to complete?

Varies, typically 6-12 months

Is a team required?

A team is not required for this type of review.

What are the protocols that are preferred or required?

Protocols can be registered on Prospero .

PRISMA-P reporting guidelines give guidance of what to include in a protocol.

When would you use this type of review?

To synthesize the highest levels of evidence available for a given topic, Umbrella Reviews are a response to the growing number of Systematic Reviews in biomedical literature.

Is there an example?

Zhang GQ, Chen JL, Luo Y, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and women's health: An umbrella review. PLoS Med. 2021;18(8):e1003731. Published 2021 Aug 2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003731

- << Previous: Rapid Reviews

- Next: Clinical Practice Guidelines >>

- Last Updated: Oct 4, 2023 4:22 PM

- URL: https://laneguides.stanford.edu/types-of-reviews

Umbrella Reviews: What They Are and Why We Need Them

Series: Methods In Molecular Biology > Book: Meta-Research

Protocol | DOI: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1566-9_8

- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Imperial College London, London, UK

- Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology, University of Ioannina Medical School, Ioannina, Greece

- Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

Evidence in clinical research is accumulating and scientific publications have increased exponentially in the last decade across all disciplines. Available information should be critically assessed. Here, we focus on umbrella reviews, an approach

Evidence in clinical research is accumulating and scientific publications have increased exponentially in the last decade across all disciplines. Available information should be critically assessed. Here, we focus on umbrella reviews, an approach that systematically collects and evaluates information from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses. To facilitate the design and the conduct of such a study, we provide a step-by-step guide on how to perform an umbrella review. We also present ways to report the summary findings, we describe various proposed grading criteria, and we discuss potential limitations.

Figures ( 0 ) & Videos ( 0 )

Experimental specifications, other keywords.

Citations (17)

Related articles, target discovery for drug development using mendelian randomization, telomere length shortening in alzheimer’s disease: procedures for a causal investigation using single nucleotide polymorphisms in a mendelian randomization study, mendelian randomization, using eqtls to reconstruct gene regulatory networks, a primer in mendelian randomization methodology with a focus on utilizing published summary association data, multivariate methods for meta-analysis of genetic association studies.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS (1996) Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 312(7023):71–72

- Ioannidis JP (2016) The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q 94(3):485–514

- Silagy CA, Middleton P, Hopewell S (2002) Publishing protocols of systematic reviews: comparing what was done to what was planned. JAMA 287(21):2831–2834

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J et al (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358:j4008

- Salanti G, Ioannidis JP (2009) Synthesis of observational studies should consider credibility ceilings. J Clin Epidemiol 62(2):115–122

- Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L (2020) Chapter V: overviews of reviews. In: JPT H, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 61 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. 2020. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/

- Sterne JA, Juni P, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Bartlett C, Egger M (2002) Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in ‘meta-epidemiological’ research. Stat Med 21(11):1513–1524

- Ioannidis JP (2009) Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ 181(8):488–493

- Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J (2017) Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 359:j5024

- Machado MO, Veronese N, Sanches M, Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Thompson T et al (2018) The association of depression and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Med 16(1):112

- Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Middleton LT, Ioannidis JPA, Evangelou E (2017) Systematic evaluation of the associations between environmental risk factors and dementia: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Alzheimer’s Dementia 13(4):406–418

- Houze B, El-Khatib H, Arbour C (2017) Efficacy tolerability, and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for chronic pain: an umbrella review on various CAM approaches. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 79(Pt B):192–205

- Corso E, Hind D, Beever D, Fuller G, Wilson MJ, Wrench IJ et al (2017) Enhanced recovery after elective caesarean: a rapid review of clinical protocols, and an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1):91

- Giannakou K, Evangelou E, Papatheodorou SI (2018) Genetic and non-genetic risk factors for pre-eclampsia: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 51(6):720–730

- Solmi M, Correll CU, Carvalho AF, Ioannidis JPA (2018) The role of meta-analyses and umbrella reviews in assessing the harms of psychotropic medications: beyond qualitative synthesis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 27(6):537–542

- Kohler CA, Evangelou E, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N, Belbasis L et al (2018) Mapping risk factors for depression across the lifespan: an umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses and Mendelian randomization studies. J Psychiatr Res 103:189–207

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D (2012) Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 1:10

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C (1994) Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ 309(6964):1286–1291

- Halladay CW, Trikalinos TA, Schmid IT, Schmid CH, Dahabreh IJ (2015) Using data sources beyond PubMed has a modest impact on the results of systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 68(9):1076–1084

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62(10):e1–e34

- Hartling L, Chisholm A, Thomson D, Dryden DM (2012) A descriptive analysis of overviews of reviews published between 2000 and 2011. PLoS One 7(11):e49667

- Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1991) Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol 44(11):1271–1278

- Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J et al (2009) AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 62(10):1013–1020

- Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Fretheim A (2006) Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 16. Evaluation. Health Res Policy Syst 4:28

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF (1999) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet 354(9193):1896–1900

- Chinn S (2000) A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med 19(22):3127–3131

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR (2010) A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 1(2):97–111

- Belbasis L, Bellou V, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP, Tzoulaki I (2015) Environmental risk factors and multiple sclerosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Neurol 14(3):263–273

- Tsilidis KK, Kasimis JC, Lopez DS, Ntzani EE, Ioannidis JP (2015) Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ 350:g7607

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315(7109):629–634

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50(4):1088–1101

- Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA (2007) An exploratory test for an excess of significant findings. Clin Trials 4(3):245–253

- Ioannidis JP (2011) Excess significance bias in the literature on brain volume abnormalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(8):773–780

- Tsilidis KK, Papatheodorou SI, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP (2012) Evaluation of excess statistical significance in meta-analyses of 98 biomarker associations with cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 104(24):1867–1878

- Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, Ioannidis JP (2014) Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. BMJ 348:g2035

- IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Rovers MM, Goeman JJ (2016) Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open 6(7):e010247

- Benjamin DJ, Berger JO, Johannesson M, Nosek BA, Wagenmakers EJ, Berk R et al (2018) Redefine statistical significance. Nat Hum Behav 2(1):6–10

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A (2011) GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):380–382

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):383–394

- Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A et al (2017) The GRADE working group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 87:4–13

- Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J et al (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64(4):401–406

Advertisement

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Topic collections

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 3

- Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Paolo Fusar-Poli 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Joaquim Radua 1 , 4 , 5

- 1 Early Psychosis: Interventions and Clinical-detection (EPIC) Lab, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience , King’s College London , London , UK

- 2 OASIS Service, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- 3 Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences , University of Pavia , Pavia , Italy

- 4 FIDMAG Germanes Hospitalaries, CIBERSAM , Barcelona , Spain

- 5 Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience , Karolinska Institute , Stockholm , Sweden

- Correspondence to Dr Paolo Fusar-Poli, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, London SE5 8AF, UK; paolo.fusar-poli{at}kcl.ac.uk

Objective Evidence syntheses such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide a rigorous and transparent knowledge base for translating clinical research into decisions, and thus they represent the basic unit of knowledge in medicine. Umbrella reviews are reviews of previously published systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Therefore, they represent one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis currently available, and are becoming increasingly influential in biomedical literature. However, practical guidance on how to conduct umbrella reviews is relatively limited.

Methods We present a critical educational review of published umbrella reviews, focusing on the essential practical steps required to produce robust umbrella reviews in the medical field.

Results The current manuscript discusses 10 key points to consider for conducting robust umbrella reviews. The points are: ensure that the umbrella review is really needed, prespecify the protocol, clearly define the variables of interest, estimate a common effect size, report the heterogeneity and potential biases, perform a stratification of the evidence, conduct sensitivity analyses, report transparent results, use appropriate software and acknowledge the limitations. We illustrate these points through recent examples from umbrella reviews and suggest specific practical recommendations.

Conclusions The current manuscript provides a practical guidance for conducting umbrella reviews in medical areas. Researchers, clinicians and policy makers might use the key points illustrated here to inform the planning, conduction and reporting of umbrella reviews in medicine.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Medical knowledge traditionally differs from other domains of human culture by its progressive nature, with clear standards or criteria for identifying improvements and advances. Evidence-based synthesis methods are traditionally thought to meet these standards. They can be thought of as the basic unit of knowledge in medicine, and allow making sense of several and often contrasting findings, which is crucial to advance clinical knowledge. In fact, clinicians accessing international databases such as PubMed to find the best evidence on a determinate topic may soon feel overwhelmed with too many findings, often contradictory and not replicating each other. Some authors have argued that biomedical science 1 suffers from a serious replication crisis, 2 to the point that scientifically, replication becomes equally as—or even more—important than discovery. 3 For example, extensive research has investigated the factors that may be associated with an increased (risk factors) or decreased (protective factors) likelihood of developing serious mental disorders such as psychosis. Despite several decades of research, results have been inconclusive because published findings have been conflicting and affected by several types of biases. 4 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses aim to synthesise the findings and investigate the biases. However, as the number of reviews of meta-analyses also increased, clinicians may also feel overwhelmed with too many of them.

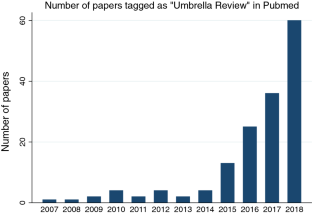

Umbrella reviews have been developed to overcome such a gap of knowledge. They are reviews of previously published systematic reviews or meta-analyses, and consist in the repetition of the meta-analyses following a uniform approach for all factors to allow their comparison. 5 Therefore, they represent one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis currently available ( figure 1 ). Not surprisingly, umbrella reviews are becoming increasingly influential in biomedical literature. This is empirically confirmed by the proliferation of this type of studies over the recent years. In fact, by searching ‘umbrella review’ in the titles of articles published on Web of Knowledge (up to 1 April 2018), we found a substantial increase in the number of umbrella reviews published over the past decade, as detailed in figure 2 . The umbrella reviews identified through our literature search were investigating a wide portion of medical branches ( figure 3 ). Furthermore, several protocols of upcoming umbrella reviews have been recently published, confirming the exponential trend. 6–12

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Hierarchy of evidence synthesis methods.

Web of Knowledge records containing ’umbrella review' in their title up to April 2018.

Focus of umbrella reviews published in Web of Knowledge (see figure 2— up to April 2018).

However, guidance on how to conduct or report umbrella reviews is relatively limited. 5 The current manuscript addresses this area by providing practical tips for conducting good umbrella reviews in medical areas. Rather than being an exhaustive primer on the methodological underpinning of umbrella reviews, we only highlight 10 key points that to our opinion are essential for conducting robust umbrella reviews. As reference example, we will use an umbrella review on risk and protective factors for psychotic disorders recently completed by our group. 13 However, we generalise the considerations presented in this manuscript and the relative recommendations to any other area of medical knowledge.

Educational and critical (non-systematic) review of the literature focusing on key practical issues that are necessary for conducting and reporting robust umbrella reviews. The authors selected illustrative umbrella reviews to highlight key methodological findings. In the results, we present 10 simple key points that the authors of umbrella reviews should carefully address when planning and conducting umbrella reviews in the medical field.

Ensure that the umbrella review is really needed

The decision to develop a new umbrella review in medical areas of knowledge should be stimulated by several factors, e.g. the topic of interest may be highly controversial or it may be affected by potential biases that have not been investigated systematically. The authors can explore these issues in the existing literature. For example, they may want to survey and identify a few examples of meta-analyses on the same topic that present contrasting findings. Second, a clear link between the need to address uncertainty and advancing clinical knowledge should be identified a priori, and acknowledged as the strong rationale for conducting an umbrella review. For example, in our previous work we speculated that by clarifying the evidence for an association between risk or protective factors and psychotic disorders we could improve our ability to identify those individuals at risk of developing psychosis. 13 Clearly, improving the detection of individuals at risk is the first step towards the implementation of preventive approaches, which are becoming a cornerstone of medicine. 14–16 Third, provided that the two points are satisfactory, it is essential to check whether there are enough meta-analyses that address a determinate topic. 17 Larger databases can increase the statistical power and therefore improve accurateness of the estimates and interpretability of the results. Furthermore, they are also likely to reflect a topic of wider interest and impact for clinical practice. These considerations are of particular relevance when considering the mass production of useless evidence synthesis studies that are redundant, not necessary and addressing clinically irrelevant outcomes. 18

Prespecify the protocol

As for any other evidence synthesis approach, it is essential to prepare a study protocol ahead of initiating the work and upload it to international databases such as PROSPERO ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ ). The authors may also publish the protocol in an open-access journal, as it is common for randomised controlled trials. The protocol should clearly define the methods for reviewing the literature and extracting data and the statistical analysis plan. Importantly, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria should be prespecified. For example, inclusion criteria from our umbrella review 13 were: (a) systematic reviews or meta-analyses of individual observational studies (case-control, cohort, cross-sectional and ecological studies) that examined the association between risk or protective factors and psychotic disorders; (b) studies considering any established diagnosis of non-organic psychotic disorders defined by the International Classification of Disease (ICD) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM); (c) inclusion of a comparison group of non-psychotic healthy controls, as defined by each study and (d) studies reporting enough data to perform the analyses. Similarly, the reporting of the literature search should adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses recommendations 19 and additional specific guidelines depending on the nature of the studies included (eg, in case of observational studies, the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines 20 ). Quality assessment of the included studies is traditionally required in evidence synthesis studies. In the absence of specific guidelines for quality assessment in umbrella reviews, A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews, a validated instrument 21 22 can be used.

Clearly define the variables of interest

Umbrella reviews are traditionally conducted to measure the association between certain factors and a determinate clinical outcome. The first relevant point to conducting a good umbrella review is therefore to define consistent and reliable factors and outcomes to be analysed.

The definition of the type of factor (eg, risk factor or biomarker) of interest may be particularly challenging. For example, in our review we found that childhood trauma was considered as a common risk factor for psychosis, 13 but available literature lacked standard operationalisation. Our pragmatic approach was to define the factors as each meta-analysis or systematic review had defined them. Another issue relates to whether and how analysts should group similar factors. For example, in our umbrella review 13 we wondered whether to merge the first-generation immigrant and second-generation immigrant risk factors for psychosis in a unique category of ‘immigrants’. However, this would have introduced newly defined categories of risk factors that were not available in the underlying literature. Our solution was not to combine similar factors if the meta-analysis or systematic review had considered and analysed them separately. Similarly, it may be important not to split categories into subgroups (eg, childhood sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse) if the meta-analysis or systematic review had considered them as a whole (eg, childhood trauma). Restricting the analyses to only the factors that each individual meta-analysis or systematic review had originally introduced may mitigate the risk of introducing newly defined factors not originally present in the literature. Such an approach is also advantageous to minimise the risk of artificially inflating the sample size by creating large and unpublished factors, therefore biassing the hierarchical classification of the evidence. The additional problem may be that a meta-analysis or a systematic review could report both results, that is , pooled across categories and divided according to specific subgroups. In this case, it is important to define a priori what kind of results is to be used. Pooled results may be preferred since they usually include larger sample sizes. Finally, there may be two meta-analyses or systematic reviews that address the same factor or that include individual studies that are overlapping. In our previous umbrella review, we selected the meta-analysis or systematic review with the largest database and the most recent one. 13

A collateral challenge in this domain may relate to the type of factors that analysts should exclude. For example, in our previous umbrella review 13 we decided to focus on risk and protective factors for psychosis only, and not on biomarkers. However, in the lack of clear etiopathogenic mechanisms for the onset of psychosis, the boundaries between biomarkers collected before the onset of the disorder and risk and protective factors were not always clear. To solve this problem, we have again adopted a pragmatic approach, adopting the definitions of risk and protective factors versus biomarker as provided by each article included in the umbrella review. A further point is that if systematic reviews are included, some of them may not have performed quantitative data on specific factors.

The additional challenge would be that individual meta-analyses or systematic reviews might have similar but not identical definition of these outcomes. For example, we intended to investigate only psychotic disorders defined by standard international validated diagnostic manuals such as the ICD or the DSM. We found that some meta-analyses that were apparently investigating psychotic disorders in reality did also include studies that were measuring psychotic symptoms not officially coded in these manuals. 13 To overcome this problem, we took the decision to verify the same inclusion and exclusion criteria that were used for reviewing the literature (eg, inclusion of DSM or ICD psychotic disorders) for each individual study included in every eligible meta-analysis or systematic review. 13 Such a process is extremely time-consuming and analysts should account for it during the early planning stages to ensure sufficient resources are in place. The authors of an umbrella review may also exclusively rely on the information provided in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses, although in that case the analysts should clearly acknowledge its potential limitations in the text. Alternatively, they may rely on the systematic reviews and meta-analyses to conduct a preselection of the factors with a greater level of evidence, and then verify the data for each individual study of these (much fewer) factors.

Estimate a common effect size

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses use different measures of effect size depending on the design and analytical approach of the studies that they review. For example, meta-analyses of case-control studies may use standardised mean differences such as the Hedge’s g to compare continuous variables, and odd ratios (ORs) to compare binary variables. Similarly, meta-analyses of cohort studies comparing incidences between exposed and non-exposed may use a ratio of incidences such as the incidence rate ratio (IRR). In addition, other measures of effect size are possible. The use of these different measures of effect size is enriching because each of them is appropriate for a type of studies, and thus we recommend also using them in the umbrella review. For example, a hazard ratio (HR) may be very appropriate for summarising a survival analysis, while it would be hard to interpret in a cross-sectional study, ultimately preventing the readers from easily getting a glimpse of the current evidence.

However, one of the main aims of an umbrella is also to allow a comparison of the size of the effects across all factors investigated, and the use of a common effect size for all factors clearly makes this comparison straightforward. For example, in our previous umbrella review of risk and protective factors for psychosis, we found that the effect size of parental communication deviance (a vague, fragmented and contradictory intrafamilial communication) was Hedge’s g =1.35, whereas the effect size of heavy cannabis use was OR=5.17. 13 Which of these factors had a larger effect? To allow a straightforward comparison, we converted all effect sizes to OR, and the equivalent OR of parental communication deviance was 11.55. Thus, reporting an equivalent OR for each factor, the readers can straightforwardly compare the factors and conclude that the effect size of parental communication deviance is substantially larger than the effect size of heavy cannabis use. To further facilitate the comparison of factors, the analysts may even force all equivalent OR to be greater than 1 (ie, inverting any OR<1). For example, in our previous umbrella review, we found that the equivalent OR of self-directedness was 0.17. 13 The inversion of this OR would be 5.72, which the reader could straightforwardly compare with other equivalent ORs>1.

An exact conversion of an effect size into an equivalent OR may not always be possible, because the measures of effect size may be inherently different and the calculations may need data that may be unavailable. For example, to convert an IRR into an OR, the analysts should first convert the IRR into a risk ratio (RR), and then the RR into an OR. However, an IRR and a RR have an important difference: the IRR accounts for the time that the researchers could follow each individual, while the RR only considers the initial sizes of the samples. In addition, even if the analysts could convert the IRR into a RR, they could not convert the RR into an OR without knowing the incidence in the non-exposed, which the papers may not report.

Fortunately, approximate conversions are relatively straightforward 23 ( table 1 ). On the one hand, the analysts may assume that HRs, IRRs, RRs and ORs are approximately equivalent as far as the incidence is not too large. Similarly, they may also assume that Cohen’s d , Glass’Δ and Hedge’s g are approximately equivalent as far as the variances in patients and controls are not too different and the sample sizes are not too small. On the other hand, the analysts can convert Hedge’s g into equivalent OR using a standard formula. 23 For other measures such as the risk difference, the ratio of means or the mean difference, the analyst will need a few general estimations ( table 1 ). In any case, such approximations are acceptable because the only aim of the equivalent OR is to provide a visual number to allow an easy comparison of the effect sizes of the different factors.

- View inline

Possible conversions of some effect sizes to equivalent ORs

Report the heterogeneity and potential biases

As with single meta-analyses, an umbrella review should study and report the heterogeneity across the studies included in each meta-analysis and the potential biases in the studies to show a more complete picture of the evidence. Independently of the effect size and the p value, the level of evidence of an effect (eg, a risk factor) is lower when there is large heterogeneity, as well as when there is potential reporting or excess significance bias. The presence of a large between-study heterogeneity may indicate, for example, that there are two groups of studies investigating two different groups of patients, and the results of a single meta-analysis for the two groups may not represent either of the groups. The presence of potential reporting bias, on the other hand, might mean that studies are only published timely in indexed journals if they find one type of results, for example, if they find that a given psychotherapy works. Of course, if the meta-analysis only includes these studies, the results will be that the psychotherapy works, even if it does not. Analysts can explore the reporting bias that affects the smallest studies with a number of tools, such as the funnel plot, Egger and similar tests and trim and fill methods. 4 Finally, the presence of potential excess significance bias would mean that the number of studies with statistically significant results is suspiciously high, and this may be related to reporting bias and to other issues such as data dredging. 4

Perform a stratification of evidence

A more detailed analysis of the umbrella reviews identified in our literature search revealed that some of them, pertaining to several clinical medical areas (neurology, oncology, nutrition medicine, internal medicine, psychiatry, paediatrics, dermatology and neurosurgery) additionally stratified the evidence using a classification method. This classification was obtained through strict criteria, equal or similar to the one listed below 24–26 :

convincing (class I) when number of cases>1000, p<10 −6 , I 2 <50%, 95% prediction interval excluding the null, no small-study effects and no excess significance bias;

highly suggestive (class II) when number of cases>1000, p<10 −6 , largest study with a statistically significant effect and class I criteria not met;