Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

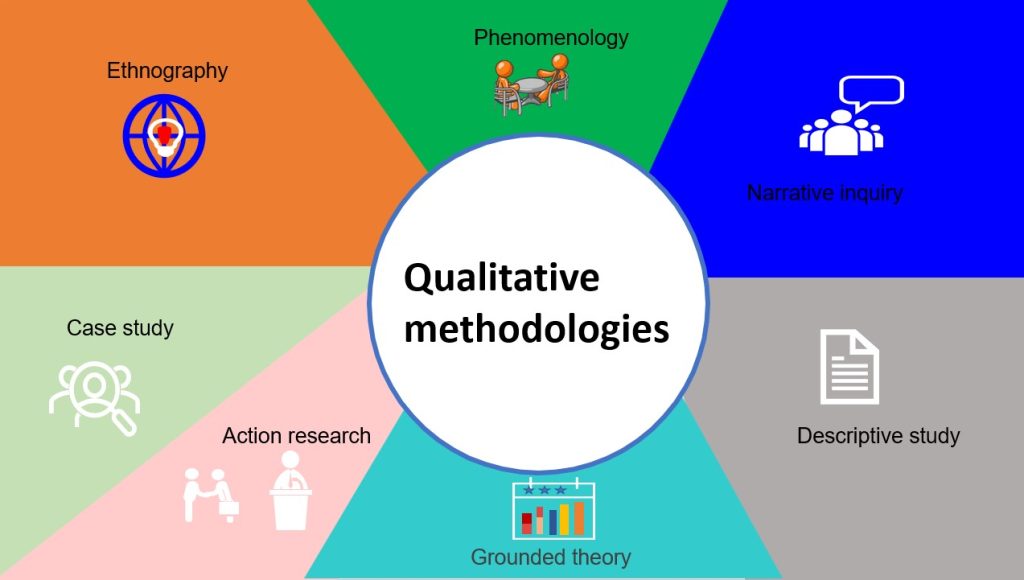

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

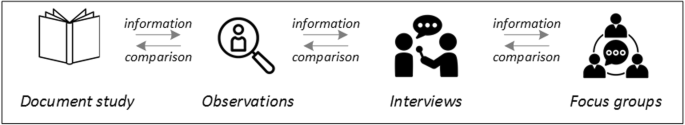

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

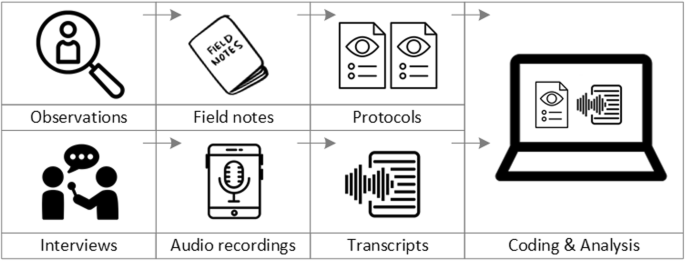

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

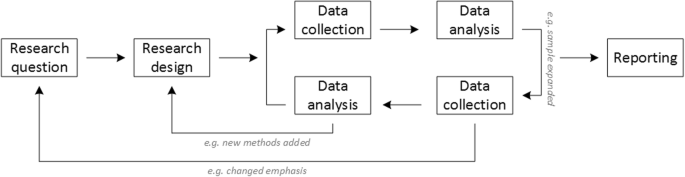

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Research Methodologies

- Quantitative Research Methodologies

Qualitative Research Methodologies

- Systematic Reviews

- Finding Articles by Methodology

- Design Your Research Project

Library Help

What is qualitative research.

Qualitative research methodologies seek to capture information that often can't be expressed numerically. These methodologies often include some level of interpretation from researchers as they collect information via observation, coded survey or interview responses, and so on. Researchers may use multiple qualitative methods in one study, as well as a theoretical or critical framework to help them interpret their data.

Qualitative research methods can be used to study:

- How are political and social attitudes formed?

- How do people make decisions?

- What teaching or training methods are most effective?

Qualitative Research Approaches

Action research.

In this type of study, researchers will actively pursue some kind of intervention, resolve a problem, or affect some kind of change. They will not only analyze the results but will also examine the challenges encountered through the process.

Ethnography

Ethnographies are an in-depth, holistic type of research used to capture cultural practices, beliefs, traditions, and so on. Here, the researcher observes and interviews members of a culture — an ethnic group, a clique, members of a religion, etc. — and then analyzes their findings.

Grounded Theory

Researchers will create and test a hypothesis using qualitative data. Often, researchers use grounded theory to understand decision-making, problem-solving, and other types of behavior.

Narrative Research

Researchers use this type of framework to understand different aspects of the human experience and how their subjects assign meaning to their experiences. Researchers use interviews to collect data from a small group of subjects, then discuss those results in the form of a narrative or story.

Phenomenology

This type of research attempts to understand the lived experiences of a group and/or how members of that group find meaning in their experiences. Researchers use interviews, observation, and other qualitative methods to collect data.

Often used to share novel or unique information, case studies consist of a detailed, in-depth description of a single subject, pilot project, specific events, and so on.

- Hossain, M.S., Runa, F., & Al Mosabbir, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on rare diseases: A case study on thalassaemia patients in Bangladesh. Public Health in Practice, 2(100150), 1-3.

- Nožina, M. (2021). The Czech Rhino connection: A case study of Vietnamese wildlife trafficking networks’ operations across central Europe. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 27(2), 265-283.

Focus Groups

Researchers will recruit people to answer questions in small group settings. Focus group members may share similar demographics or be diverse, depending on the researchers' needs. Group members will then be asked a series of questions and have their responses recorded. While these responses may be coded and discussed numerically (e.g., 50% of group members responded negatively to a question), researchers will also use responses to provide context, nuance, and other details.

- Dichabeng, P., Merat, N., & Markkula, G. (2021). Factors that influence the acceptance of future shared automated vehicles – A focus group study with United Kingdom drivers. Transportation Research: Part F, 82, 121–140.

- Maynard, E., Barton, S., Rivett, K., Maynard, O., & Davies, W. (2021). Because ‘grown-ups don’t always get it right’: Allyship with children in research—From research question to authorship. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(4), 518–536.

Observational Study

Researchers will arrange to observe (usually in an unobtrusive way) a set of subjects in specific conditions. For example, researchers might visit a school cafeteria to learn about the food choices students make or set up trail cameras to collect information about animal behavior in the area.

- He, J. Y., Chan, P. W., Li, Q. S., Li, L., Zhang, L., & Yang, H. L. (2022). Observations of wind and turbulence structures of Super Typhoons Hato and Mangkhut over land from a 356 m high meteorological tower. Atmospheric Research, 265(105910), 1-18.

- Zerovnik Spela, Kos Mitja, & Locatelli Igor. (2022). Initiation of insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: An observational study. Acta Pharmaceutica, 72(1), 147–157.

Open-Ended Surveys

Unlike quantitative surveys, open-ended surveys require respondents to answer the questions in their own words.

- Mujcic, A., Blankers, M., Yildirim, D., Boon, B., & Engels, R. (2021). Cancer survivors’ views on digital support for smoking cessation and alcohol moderation: a survey and qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-13.

- Smith, S. D., Hall, J. P., & Kurth, N. K. (2021). Perspectives on health policy from people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 32(3), 224–232.

Structured or Semi-Structured Interviews

Researchers will recruit a small number of people who fit pre-determined criteria (e.g., people in a certain profession) and ask each the same set of questions, one-on-one. Semi-structured interviews will include opportunities for the interviewee to provide additional information they weren't asked about by the researcher.

- Gibbs, D., Haven-Tang, C., & Ritchie, C. (2021). Harmless flirtations or co-creation? Exploring flirtatious encounters in hospitable experiences. Tourism & Hospitality Research, 21(4), 473–486.

- Hongying Dai, Ramos, A., Tamrakar, N., Cheney, M., Samson, K., & Grimm, B. (2021). School personnel’s responses to school-based vaping prevention program: A qualitative study. Health Behavior & Policy Review, 8(2), 130–147.

- Call : 801.863.8840

- Text : 801.290.8123

- In-Person Help

- Email a Librarian

- Make an Appointment

- << Previous: Quantitative Research Methodologies

- Next: Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 11:11 AM

- URL: https://uvu.libguides.com/methods

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2023 3:14 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 30th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 10:41 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Qualitative Research Methods: Types, Analysis + Examples

Qualitative research is based on the disciplines of social sciences like psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Therefore, the qualitative research methods allow for in-depth and further probing and questioning of respondents based on their responses. The interviewer/researcher also tries to understand their motivation and feelings. Understanding how your audience makes decisions can help derive conclusions in market research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as a market research method that focuses on obtaining data through open-ended and conversational communication .

This method is about “what” people think and “why” they think so. For example, consider a convenience store looking to improve its patronage. A systematic observation concludes that more men are visiting this store. One good method to determine why women were not visiting the store is conducting an in-depth interview method with potential customers.

For example, after successfully interviewing female customers and visiting nearby stores and malls, the researchers selected participants through random sampling . As a result, it was discovered that the store didn’t have enough items for women.

So fewer women were visiting the store, which was understood only by personally interacting with them and understanding why they didn’t visit the store because there were more male products than female ones.

Gather research insights

Types of qualitative research methods with examples

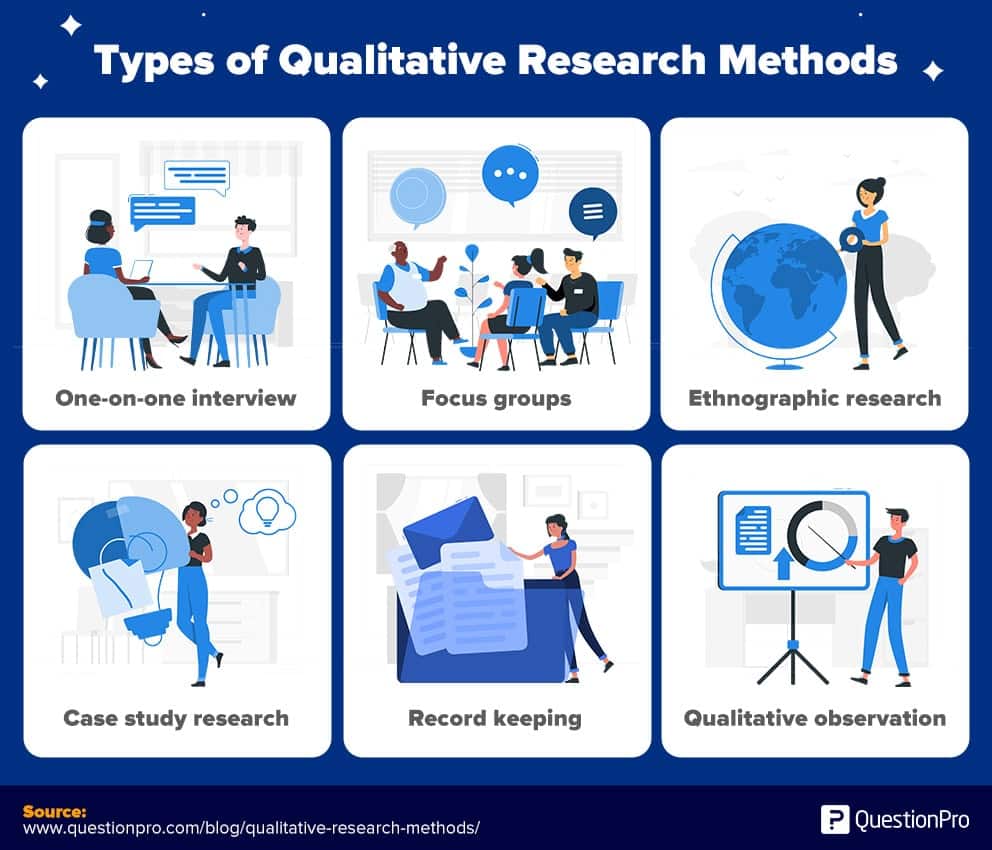

Qualitative research methods are designed in a manner that helps reveal the behavior and perception of a target audience with reference to a particular topic. There are different types of qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, ethnographic research, content analysis, and case study research that are usually used.

The results of qualitative methods are more descriptive, and the inferences can be drawn quite easily from the obtained data .

Qualitative research methods originated in the social and behavioral research sciences. Today, our world is more complicated, and it is difficult to understand what people think and perceive. Online research methods make it easier to understand that as it is a more communicative and descriptive analysis .

The following are the qualitative research methods that are frequently used. Also, read about qualitative research examples :

1. One-on-one interview

Conducting in-depth interviews is one of the most common qualitative research methods. It is a personal interview that is carried out with one respondent at a time. This is purely a conversational method and invites opportunities to get details in depth from the respondent.

One of the advantages of this method is that it provides a great opportunity to gather precise data about what people believe and their motivations . If the researcher is well experienced, asking the right questions can help him/her collect meaningful data. If they should need more information, the researchers should ask such follow-up questions that will help them collect more information.

These interviews can be performed face-to-face or on the phone and usually can last between half an hour to two hours or even more. When the in-depth interview is conducted face to face, it gives a better opportunity to read the respondents’ body language and match the responses.

2. Focus groups

A focus group is also a commonly used qualitative research method used in data collection. A focus group usually includes a limited number of respondents (6-10) from within your target market.

The main aim of the focus group is to find answers to the “why, ” “what,” and “how” questions. One advantage of focus groups is you don’t necessarily need to interact with the group in person. Nowadays, focus groups can be sent an online survey on various devices, and responses can be collected at the click of a button.

Focus groups are an expensive method as compared to other online qualitative research methods. Typically, they are used to explain complex processes. This method is very useful for market research on new products and testing new concepts.

3. Ethnographic research

Ethnographic research is the most in-depth observational research method that studies people in their naturally occurring environment.

This method requires the researchers to adapt to the target audiences’ environments, which could be anywhere from an organization to a city or any remote location. Here, geographical constraints can be an issue while collecting data.

This research design aims to understand the cultures, challenges, motivations, and settings that occur. Instead of relying on interviews and discussions, you experience the natural settings firsthand.

This type of research method can last from a few days to a few years, as it involves in-depth observation and collecting data on those grounds. It’s a challenging and time-consuming method and solely depends on the researcher’s expertise to analyze, observe, and infer the data.

4. Case study research

T he case study method has evolved over the past few years and developed into a valuable quality research method. As the name suggests, it is used for explaining an organization or an entity.

This type of research method is used within a number of areas like education, social sciences, and similar. This method may look difficult to operate; however , it is one of the simplest ways of conducting research as it involves a deep dive and thorough understanding of the data collection methods and inferring the data.

5. Record keeping

This method makes use of the already existing reliable documents and similar sources of information as the data source. This data can be used in new research. This is similar to going to a library. There, one can go over books and other reference material to collect relevant data that can likely be used in the research.

6. Process of observation

Qualitative Observation is a process of research that uses subjective methodologies to gather systematic information or data. Since the focus on qualitative observation is the research process of using subjective methodologies to gather information or data. Qualitative observation is primarily used to equate quality differences.

Qualitative observation deals with the 5 major sensory organs and their functioning – sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing. This doesn’t involve measurements or numbers but instead characteristics.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research: data collection and analysis

A. qualitative data collection.

Qualitative data collection allows collecting data that is non-numeric and helps us to explore how decisions are made and provide us with detailed insight. For reaching such conclusions the data that is collected should be holistic, rich, and nuanced and findings to emerge through careful analysis.

- Whatever method a researcher chooses for collecting qualitative data, one aspect is very clear the process will generate a large amount of data. In addition to the variety of methods available, there are also different methods of collecting and recording the data.

For example, if the qualitative data is collected through a focus group or one-to-one discussion, there will be handwritten notes or video recorded tapes. If there are recording they should be transcribed and before the process of data analysis can begin.

- As a rough guide, it can take a seasoned researcher 8-10 hours to transcribe the recordings of an interview, which can generate roughly 20-30 pages of dialogues. Many researchers also like to maintain separate folders to maintain the recording collected from the different focus group. This helps them compartmentalize the data collected.

- In case there are running notes taken, which are also known as field notes, they are helpful in maintaining comments, environmental contexts, environmental analysis , nonverbal cues etc. These filed notes are helpful and can be compared while transcribing audio recorded data. Such notes are usually informal but should be secured in a similar manner as the video recordings or the audio tapes.

B. Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative data analysis such as notes, videos, audio recordings images, and text documents. One of the most used methods for qualitative data analysis is text analysis.

Text analysis is a data analysis method that is distinctly different from all other qualitative research methods, where researchers analyze the social life of the participants in the research study and decode the words, actions, etc.

There are images also that are used in this research study and the researchers analyze the context in which the images are used and draw inferences from them. In the last decade, text analysis through what is shared on social media platforms has gained supreme popularity.

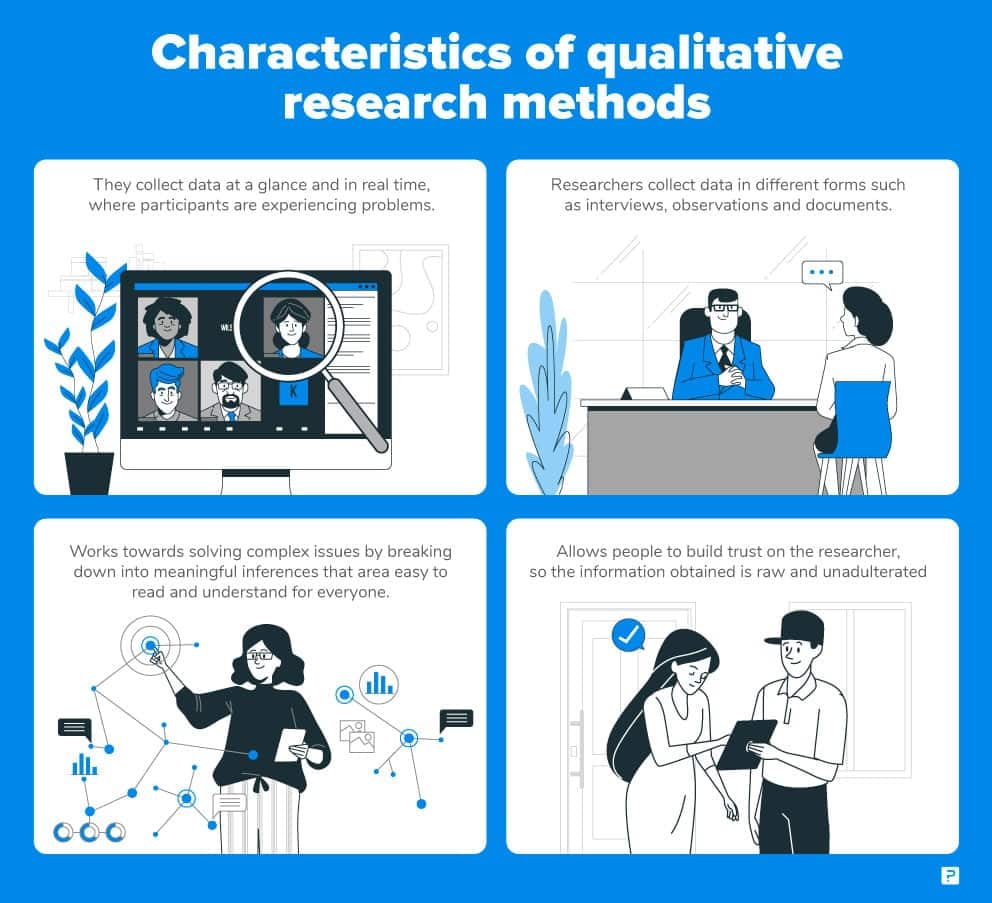

Characteristics of qualitative research methods

- Qualitative research methods usually collect data at the sight, where the participants are experiencing issues or research problems . These are real-time data and rarely bring the participants out of the geographic locations to collect information.

- Qualitative researchers typically gather multiple forms of data, such as interviews, observations, and documents, rather than rely on a single data source .

- This type of research method works towards solving complex issues by breaking down into meaningful inferences, that is easily readable and understood by all.

- Since it’s a more communicative method, people can build their trust on the researcher and the information thus obtained is raw and unadulterated.

Qualitative research method case study

Let’s take the example of a bookstore owner who is looking for ways to improve their sales and customer outreach. An online community of members who were loyal patrons of the bookstore were interviewed and related questions were asked and the questions were answered by them.

At the end of the interview, it was realized that most of the books in the stores were suitable for adults and there were not enough options for children or teenagers.

By conducting this qualitative research the bookstore owner realized what the shortcomings were and what were the feelings of the readers. Through this research now the bookstore owner can now keep books for different age categories and can improve his sales and customer outreach.

Such qualitative research method examples can serve as the basis to indulge in further quantitative research , which provides remedies.

When to use qualitative research

Researchers make use of qualitative research techniques when they need to capture accurate, in-depth insights. It is very useful to capture “factual data”. Here are some examples of when to use qualitative research.

- Developing a new product or generating an idea.

- Studying your product/brand or service to strengthen your marketing strategy.

- To understand your strengths and weaknesses.

- Understanding purchase behavior.

- To study the reactions of your audience to marketing campaigns and other communications.

- Exploring market demographics, segments, and customer care groups.

- Gathering perception data of a brand, company, or product.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research methods vs quantitative research methods

The basic differences between qualitative research methods and quantitative research methods are simple and straightforward. They differ in:

- Their analytical objectives

- Types of questions asked

- Types of data collection instruments

- Forms of data they produce

- Degree of flexibility

LEARN MORE ABOUR OUR SOFTWARE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 13 A/B Testing Software for Optimizing Your Website

Apr 12, 2024

21 Best Contact Center Experience Software in 2024

Government Customer Experience: Impact on Government Service

Apr 11, 2024

Employee Engagement App: Top 11 For Workforce Improvement

Apr 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Qualitative research: methods and examples

Last updated

13 April 2023

Reviewed by

Qualitative research involves gathering and evaluating non-numerical information to comprehend concepts, perspectives, and experiences. It’s also helpful for obtaining in-depth insights into a certain subject or generating new research ideas.

As a result, qualitative research is practical if you want to try anything new or produce new ideas.

There are various ways you can conduct qualitative research. In this article, you'll learn more about qualitative research methodologies, including when you should use them.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a broad term describing various research types that rely on asking open-ended questions. Qualitative research investigates “how” or “why” certain phenomena occur. It is about discovering the inherent nature of something.

The primary objective of qualitative research is to understand an individual's ideas, points of view, and feelings. In this way, collecting in-depth knowledge of a specific topic is possible. Knowing your audience's feelings about a particular subject is important for making reasonable research conclusions.

Unlike quantitative research , this approach does not involve collecting numerical, objective data for statistical analysis. Qualitative research is used extensively in education, sociology, health science, history, and anthropology.

- Types of qualitative research methodology

Typically, qualitative research aims at uncovering the attitudes and behavior of the target audience concerning a specific topic. For example, “How would you describe your experience as a new Dovetail user?”

Some of the methods for conducting qualitative analysis include:

Focus groups

Hosting a focus group is a popular qualitative research method. It involves obtaining qualitative data from a limited sample of participants. In a moderated version of a focus group, the moderator asks participants a series of predefined questions. They aim to interact and build a group discussion that reveals their preferences, candid thoughts, and experiences.

Unmoderated, online focus groups are increasingly popular because they eliminate the need to interact with people face to face.

Focus groups can be more cost-effective than 1:1 interviews or studying a group in a natural setting and reporting one’s observations.

Focus groups make it possible to gather multiple points of view quickly and efficiently, making them an excellent choice for testing new concepts or conducting market research on a new product.

However, there are some potential drawbacks to this method. It may be unsuitable for sensitive or controversial topics. Participants might be reluctant to disclose their true feelings or respond falsely to conform to what they believe is the socially acceptable answer (known as response bias).

Case study research

A case study is an in-depth evaluation of a specific person, incident, organization, or society. This type of qualitative research has evolved into a broadly applied research method in education, law, business, and the social sciences.

Even though case study research may appear challenging to implement, it is one of the most direct research methods. It requires detailed analysis, broad-ranging data collection methodologies, and a degree of existing knowledge about the subject area under investigation.

Historical model

The historical approach is a distinct research method that deeply examines previous events to better understand the present and forecast future occurrences of the same phenomena. Its primary goal is to evaluate the impacts of history on the present and hence discover comparable patterns in the present to predict future outcomes.

Oral history

This qualitative data collection method involves gathering verbal testimonials from individuals about their personal experiences. It is widely used in historical disciplines to offer counterpoints to established historical facts and narratives. The most common methods of gathering oral history are audio recordings, analysis of auto-biographical text, videos, and interviews.

Qualitative observation

One of the most fundamental, oldest research methods, qualitative observation , is the process through which a researcher collects data using their senses of sight, smell, hearing, etc. It is used to observe the properties of the subject being studied. For example, “What does it look like?” As research methods go, it is subjective and depends on researchers’ first-hand experiences to obtain information, so it is prone to bias. However, it is an excellent way to start a broad line of inquiry like, “What is going on here?”

Record keeping and review

Record keeping uses existing documents and relevant data sources that can be employed for future studies. It is equivalent to visiting the library and going through publications or any other reference material to gather important facts that will likely be used in the research.

Grounded theory approach

The grounded theory approach is a commonly used research method employed across a variety of different studies. It offers a unique way to gather, interpret, and analyze. With this approach, data is gathered and analyzed simultaneously. Existing analysis frames and codes are disregarded, and data is analyzed inductively, with new codes and frames generated from the research.

Ethnographic research

Ethnography is a descriptive form of a qualitative study of people and their cultures. Its primary goal is to study people's behavior in their natural environment. This method necessitates that the researcher adapts to their target audience's setting.

Thereby, you will be able to understand their motivation, lifestyle, ambitions, traditions, and culture in situ. But, the researcher must be prepared to deal with geographical constraints while collecting data i.e., audiences can’t be studied in a laboratory or research facility.

This study can last from a couple of days to several years. Thus, it is time-consuming and complicated, requiring you to have both the time to gather the relevant data as well as the expertise in analyzing, observing, and interpreting data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Narrative framework

A narrative framework is a qualitative research approach that relies on people's written text or visual images. It entails people analyzing these events or narratives to determine certain topics or issues. With this approach, you can understand how people represent themselves and their experiences to a larger audience.

Phenomenological approach

The phenomenological study seeks to investigate the experiences of a particular phenomenon within a group of individuals or communities. It analyzes a certain event through interviews with persons who have witnessed it to determine the connections between their views. Even though this method relies heavily on interviews, other data sources (recorded notes), and observations could be employed to enhance the findings.

- Qualitative research methods (tools)

Some of the instruments involved in qualitative research include:

Document research: Also known as document analysis because it involves evaluating written documents. These can include personal and non-personal materials like archives, policy publications, yearly reports, diaries, or letters.

Focus groups: This is where a researcher poses questions and generates conversation among a group of people. The major goal of focus groups is to examine participants' experiences and knowledge, including research into how and why individuals act in various ways.

Secondary study: Involves acquiring existing information from texts, images, audio, or video recordings.

Observations: This requires thorough field notes on everything you see, hear, or experience. Compared to reported conduct or opinion, this study method can assist you in getting insights into a specific situation and observable behaviors.

Structured interviews : In this approach, you will directly engage people one-on-one. Interviews are ideal for learning about a person's subjective beliefs, motivations, and encounters.

Surveys: This is when you distribute questionnaires containing open-ended questions

- What are common examples of qualitative research?

Everyday examples of qualitative research include:

Conducting a demographic analysis of a business

For instance, suppose you own a business such as a grocery store (or any store) and believe it caters to a broad customer base, but after conducting a demographic analysis, you discover that most of your customers are men.

You could do 1:1 interviews with female customers to learn why they don't shop at your store.

In this case, interviewing potential female customers should clarify why they don't find your shop appealing. It could be because of the products you sell or a need for greater brand awareness, among other possible reasons.

Launching or testing a new product

Suppose you are the product manager at a SaaS company looking to introduce a new product. Focus groups can be an excellent way to determine whether your product is marketable.

In this instance, you could hold a focus group with a sample group drawn from your intended audience. The group will explore the product based on its new features while you ensure adequate data on how users react to the new features. The data you collect will be key to making sales and marketing decisions.

Conducting studies to explain buyers' behaviors

You can also use qualitative research to understand existing buyer behavior better. Marketers analyze historical information linked to their businesses and industries to see when purchasers buy more.

Qualitative research can help you determine when to target new clients and peak seasons to boost sales by investigating the reason behind these behaviors.

- Qualitative research: data collection

Data collection is gathering information on predetermined variables to gain appropriate answers, test hypotheses, and analyze results. Researchers will collect non-numerical data for qualitative data collection to obtain detailed explanations and draw conclusions.

To get valid findings and achieve a conclusion in qualitative research, researchers must collect comprehensive and multifaceted data.

Qualitative data is usually gathered through interviews or focus groups with videotapes or handwritten notes. If there are recordings, they are transcribed before the data analysis process. Researchers keep separate folders for the recordings acquired from each focus group when collecting qualitative research data to categorize the data.

- Qualitative research: data analysis

Qualitative data analysis is organizing, examining, and interpreting qualitative data. Its main objective is identifying trends and patterns, responding to research questions, and recommending actions based on the findings. Textual analysis is a popular method for analyzing qualitative data.

Textual analysis differs from other qualitative research approaches in that researchers consider the social circumstances of study participants to decode their words, behaviors, and broader meaning.

Learn more about qualitative research data analysis software

- When to use qualitative research

Qualitative research is helpful in various situations, particularly when a researcher wants to capture accurate, in-depth insights.

Here are some instances when qualitative research can be valuable:

Examining your product or service to improve your marketing approach

When researching market segments, demographics, and customer service teams

Identifying client language when you want to design a quantitative survey

When attempting to comprehend your or someone else's strengths and weaknesses

Assessing feelings and beliefs about societal and public policy matters

Collecting information about a business or product's perception

Analyzing your target audience's reactions to marketing efforts

When launching a new product or coming up with a new idea

When seeking to evaluate buyers' purchasing patterns

- Qualitative research methods vs. quantitative research methods

Qualitative research examines people's ideas and what influences their perception, whereas quantitative research draws conclusions based on numbers and measurements.

Qualitative research is descriptive, and its primary goal is to comprehensively understand people's attitudes, behaviors, and ideas.

In contrast, quantitative research is more restrictive because it relies on numerical data and analyzes statistical data to make decisions. This research method assists researchers in gaining an initial grasp of the subject, which deals with numbers. For instance, the number of customers likely to purchase your products or use your services.

What is the most important feature of qualitative research?

A distinguishing feature of qualitative research is that it’s conducted in a real-world setting instead of a simulated environment. The researcher is examining actual phenomena instead of experimenting with different variables to see what outcomes (data) might result.

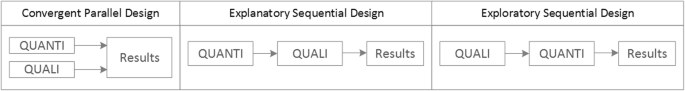

Can I use qualitative and quantitative approaches together in a study?

Yes, combining qualitative and quantitative research approaches happens all the time and is known as mixed methods research. For example, you could study individuals’ perceived risk in a certain scenario, such as how people rate the safety or riskiness of a given neighborhood. Simultaneously, you could analyze historical data objectively, indicating how safe or dangerous that area has been in the last year. To get the most out of mixed-method research, it’s important to understand the pros and cons of each methodology, so you can create a thoughtfully designed study that will yield compelling results.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Research Paper Guide

Types Of Qualitative Research

8 Types of Qualitative Research - Overview & Examples

16 min read

People also read

Research Paper Writing - A Step by Step Guide

Research Paper Examples - Free Sample Papers for Different Formats!

Guide to Creating Effective Research Paper Outline

Interesting Research Paper Topics for 2024

Research Proposal Writing - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Start a Research Paper - 7 Easy Steps

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper - A Step by Step Guide

Writing a Literature Review For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Qualitative Research - Methods, Types, and Examples

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research - Learning the Basics

200+ Engaging Psychology Research Paper Topics for Students in 2024

Learn How to Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper: Examples and Tips!

20+ Types of Research With Examples - A Detailed Guide

Understanding Quantitative Research - Types & Data Collection Techniques

230+ Sociology Research Topics & Ideas for Students

How to Cite a Research Paper - A Complete Guide

Excellent History Research Paper Topics- 300+ Ideas

A Guide on Writing the Method Section of a Research Paper - Examples & Tips

How To Write an Introduction Paragraph For a Research Paper: Learn with Examples

Crafting a Winning Research Paper Title: A Complete Guide

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion - Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a Thesis For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write A Discussion For A Research Paper | Examples & Tips

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Writing a Problem Statement for a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Finding Sources For a Research Paper: A Complete Guide

A Guide on How to Edit a Research Paper

200+ Ethical Research Paper Topics to Begin With (2024)

300+ Controversial Research Paper Topics & Ideas - 2024 Edition

150+ Argumentative Research Paper Topics For You - 2024

How to Write a Research Methodology for a Research Paper

Are you overwhelmed by the multitude of qualitative research methods available? It's no secret that choosing the right approach can leave you stuck at the starting line of your research.

Selecting an unsuitable method can lead to wasted time, resources, and potentially skewed results. But with so many options to consider, it's easy to feel lost in the complexities of qualitative research.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explain the types of qualitative research, their unique characteristics, advantages, and best use cases for each method.

Let's dive in!

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

- 1. What is Qualitative Research?

- 2. Types of Qualitative Research Methods

- 3. Types of Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is a robust and flexible methodology used to explore and understand complex phenomena in-depth.

Unlike quantitative research , qualitative research dives into the rich and complex aspects of human experiences, behaviors, and perceptions.

At its core, this type of research question seek to answer for:

- Why do people think or behave a certain way?

- What are the underlying motivations and meanings behind actions?

- How do individuals perceive and interpret the world around them?

This approach values context, diversity, and the unique perspectives of participants.

Rather than seeking generalizable findings applicable to a broad population, qualitative research aims for detailed insights, patterns, and themes that come from the people being studied.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research possesses the following characteristics:

- Subjective Perspective: Qualitative research explores subjective experiences, emphasizing the uniqueness of human behavior and opinions.

- In-Depth Exploration: It involves deep investigation, allowing a comprehensive understanding of specific phenomena.

- Open-Ended Questions: Qualitative research uses open-ended questions to encourage detailed, descriptive responses.

- Contextual Understanding: It emphasizes the importance of understanding the research context and setting.

- Rich Descriptions: Qualitative research produces rich, descriptive findings that contribute to a nuanced understanding of the topic.

Types of Qualitative Research Methods