College & Research Libraries News ( C&RL News ) is the official newsmagazine and publication of record of the Association of College & Research Libraries, providing articles on the latest trends and practices affecting academic and research libraries.

C&RL News became an online-only publication beginning with the January 2022 issue.

C&RL News Reader Survey

Give us your feedback in the 2024 C&RL News reader survey ! The survey asks a series of questions today to gather your thoughts on the contents and presentation of the magazine and should only take approximately 5-7 minutes to complete. Thank you for taking the time to provide your feedback and suggestions for C&RL News , we greatly appreciate and value your input.

Research Assistant and Lecturer University of Missouri-Columbia

ALA JobLIST

Advertising Information

- Preparing great speeches: A 10-step approach (215885 views)

- The American Civil War: A collection of free online primary sources (200261 views)

- 2018 top trends in academic libraries: A review of the trends and issues affecting academic libraries in higher education (77674 views)

ACRL College & Research Libraries News

Association of College & Research Libraries

Research forum: structured observation: how it works.

By Jack Glazier Research Assistant and Lecturer University of Missouri-Columbia

The project described in this article was originally reported at the ALA Library Research Round Table’s Research Forum in Dallas and again at the College and University Libraries Section of the Kansas Library Association in Topeka in October 1984. The research project 1 itself was designed and implemented by Robert Grover, dean of the School of Library and Information Management, Emporia (Kansas) State University, and this author. The project was planned 1) to test structured observation as a research methodology which can be used for research in schools preparing library and information professionals, and 2) to determine the information use patterns of a specific target group as a study of information transfer theory.

Information flow

Greer has developed a model 2 in which the transfer of information assumes identifiable patterns influenced by the environment encompassing the social roles of the individual information user. That environment includes patterns of information generation, dissemination, and utilization, as well as a specialized vocabulary, and pertinent names and places singular to the individual’s subsociety.

Although Greer’s information transfer model provided a theoretical suprastructure, research was still needed to detail more clearly the patterns of information transfer for various subsocieties. Appropriate and innovative methodologies are essential for research of this type. Consequently, one early objective was the development of a methodology for research designed to map the patterns of information transfer for specific subsocieties that would be as workable for graduate students and faculty as for practitioners in the field.

Structured observation

The primary methodology selected was structured observation. Structured observation is a qualitative research methodology that has been used by the social sciences for several years. It is a methodology in which an event or series of events is observed in its natural setting and recorded by an independent researcher. The observations are structured in the sense that pre-determined categories are used to guide the recording process. It is a methodology that, although not used to our knowledge for library research in this country before, seemed to us to be particularly well suited for information transfer research as we had envisioned it.

As a qualitative research methodology, structured observation was desirable for the study of information transfer theory for several reasons, especially its flexibility that allowed us to change the length of the observation periods from what others had previously used. Structured observation could yield specific types of data from an unfamiliar and unrehearsed sequence of activities.

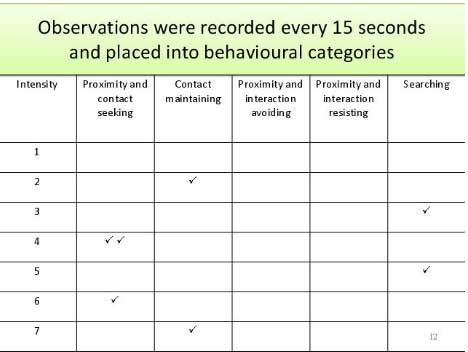

Structured observation is also systematic and comprehensive, allowing an observer to record data in predetermined increments during a specified period of time. A final consideration for our selection was that structured observation had been recently utilized in a research project by Hale in the field of public administration 3 to investigate city managers in California as interactive information agents.

The subjects

The subsociety selected for our investigation was also city managers. We chose them in part because of their role in the Hale study, which employed the same basic methodology that we intended to use. Although our study was not to be an exact replication of the Hale study, we believed that there were enough similarities that we would be able to use it to help validate our version of structured observation. Another more pragmatic reason for our selection was the accessibility of the group. There were cities employing the city manager/city commission form of government geographically close enough to make travel feasible on our limited budget.

Two consultants who were acknowledged experts in the area of public administration helped in the actual process of selecting the subjects. Both were asked to submit a ranked list of successful city managers working in Kansas. The consultants recommended a total of ten prospective subjects. Their recommendations were then merged in rank order and the prospective subjects were contacted by letter and phone.

For this study we needed five subjects willing to commit themselves, their staffs, their offices, and their time to our project. We decided to contact subjects one after another until we were able to find five willing to make this investment. Only in three instances were we unable to use a recommended subject. Time involvement was the reason most often given by subjects not wishing to participate in the study.

After they had consented to take part in the project, we visited and interviewed each of the five managers and their staffs prior to beginning the observation sessions. At the meetings we explained more fully the project and its methodology, asked them for candid answers, and conducted a pre-study interview regarding their perceived information sources. We also scheduled an interview with the manager’s secretary at this time, and requested additional data such as the manager’s vitae, a copy of his work calendar for the past month, and a copy of the city’s organizational chart. In each instance, managers were assured that the focus of the study was the job, not the individual; the basic similarities in information use, not the differences; and the actual processes involved in information use in relation to everyday on-the-job activities. Finally, we set times and dates for the actual observation sessions.

The sessions

Initially there were to be five observation sessions, each four hours in length. Sessions were planned for consecutive work days, alternating mornings and and afternoons. However, as the observations proceeded we varied the design of the methodology. Occasionally unforeseen situations would arise involving the manager’s schedule that would require alterations in the time frame. For example, if a manager was unable to be in his office for a morning session, the session could often be rescheduled for the afternoon, even though it might mean more afternoon sessions than were originally planned. In one instance, the manager had a late morning meeting that extended into the afternoon resulting in an observation session of six hours instead of four. After looking at the data gathered from these sessions we found that these changes did not appear to affect seriously the continuity of the data. This led us to design variation into future observations as a further test of the methodology from the standpoint of both the tools and the actual observer.

In fact what we found was that although the tools held up fine, it was the observer that suffered. The longer days and back-to-back sessions, coupled with the stress of travel, made concentration difficult for the observer at the end of a long day. Varia- tions in the length of the observation sessions appeared to affect the data quantitatively, not qualitatively.

For the actual observations the only tools that were taken into the sessions were two mechanical pencils, a watch, a clipboard, and the recording forms. Two types of forms were employed. The first, called a chronological form, was used to record the moment by moment activities of the subject. Its design was based on a communication model involving sender, receiver, and message. Categories for recording the data included: time of the activity; description of the activity (meeting, phone, conversation, etc.); the medium of communication (telephone, direct personal communication, etc.); description of the apparent purposes and issues of the communication (this was often verified with the city manager during quiet times); and the location of the communication (this category was necessary because not all communication took place in the manager’s office).

The second form was similar to the chronological form, but with the addition of a category for recording the attention given a particular item (skimmed, read, studied, etc.) and one that gave some indication of the disposition of a specific item (filed, sent on, discarded, etc.). The forms were designed to aid in taking notes that were as accurate and efficient as possible.

For structured observation to yield valid results, the observer has to be cautious not to affect the behavior of the subject. We operated on the principle that the more inconspicuous the observer, the less effect his presence would have.

We found several ways that seemed to work in making an observer less obtrusive. One way was for the observer to limit eye contact with the subjects as much as possible during meetings or conversations. By not establishing eye contact from the start, the subjects soon became involved in the business at hand and forgot about the observer’s presence. Another method was for the observer to keep his head down with attention directed strictly on the forms. When I used this technique in our observations it helped in several ways. It took care of the problem of eye contact and in effect took me out of the meetings. In addition, by concentrating solely on notes during meetings, my attention was easier to control and my notes were more detailed and complete.

Another aspect central to controlling the observer’s impact on the subject and the environment was positioning the observer in the manager’s office. We found that the best location for the observer was behind and slightly to the right of the subject. This location allowed the observer a clear view of the subject’s desk as well as the entire room. It also placed the observer close enough to the subject to be able to hear and note phone conversations.

Permission had been given for the observer to have access to the subject’s phone calls and mail. Provisions were made for the observer to leave the room if the manager felt the subject being discussed was sensitive. This only happened once and then only for a few minutes. On two occasions the observer was asked not to divulge the specifics of a conversation. In each case the conversation involved the recruitment of new businesses to the community. With these few exceptions, the observer was able to log detailed and comprehensive data.

One problem faced by the observer was long periods of inactivity on the part of the subject. Maintaining attention and yet remaining as inobtrusive as possible during these periods was difficult. On one occasion a manager spent nearly two hours preparing a presentation for the city commission meeting. A majority of the time was spent writing with an occasional recourse to a reference book located on his desk. As the observer in this case, I found remaining alert and attentive without shuffling papers or shifting positions for two hours a formidable task. This experience led us to conclude that data gathering in similar situations would be best accomplished using an alternative methodology such as interviews.

Conversely, a subject that is overly active can also present problems for the researcher. Subjects who are constantly on the move or involved in a large number of impromptu information exchanges presented difficulties in accurately recording data. One manager we observed spent a large amount of time visiting department heads in their offices. Often this manager would meet individuals in the hallways while moving from one office to another. The ensuing conversations were often short in duration but substantive in content. Note-taking while accompanying a subject along a hallway was difficult. The result was that the observer would have extremely sketchy notes on an encounter that in some instances was a significant aspect of a subject’s information transfer pattern. In this situation a solution might be for the observer to carry and use a tape recorder.

Another instance where a high degree of activity became a problem was in meetings. Meetings involving several participants created difficulties for the observer because of the amount of data and the rate at which it was generated. In an effort to deal with this type of situation we tested the use of two observers. We found this worked very well. By putting the notes together we had a complete record of a fast-moving, complex meeting. Another alternative would be to tape record or videotape the meeting if only one observer were available for the session.

When problems arose during observations the observer made a note of the situation so that it could be discussed during a debriefing session. Debriefing sessions were held as soon as possible after each session. They were initially designed for the two principals in the project (Robert Grover and myself) to discuss difficulties encountered during an observation and to make necessary adjustments. We also reviewed highlights of the day while checking observation notes for clarity.

Our analysis of the structured observation method showed that it permitted the researcher to gather complete data on complex information interactions. It yielded data with sufficient context to remain fresh, thus allowing researchers more time for analysis. In most instances the data was gathered with relationships intact, resulting in clearer explanations. The data clearly defined the information transfer patterns of a specific subsociety— city managers. The success of this project relied to a large degree on the flexibility of the methodology.

Today not only must academic librarians be aware of a wide range of research methodologies to support the research being done by students and faculty, but they also are finding that research and publication have become necessary prerequisites for professional advancement. Unfortunately librarians must deal with time constraints which limit research opportunities.

One consequence of this project is that it validated a methodology that is responsive to the research needs of practitioners. Specifically, we found that structured observation is appropriate for use by academic librarians, when used in conjunction with interviews or other data gathering techniques, to determine the information behavior and needs of specific client groups. It is particularly effective for gathering data about client groups for which little is known.

However, for academic librarians the strength of structured observation is its adaptability to restrictive time limitations as well as its wide range of applications. It is a methodology well suited for observing classroom instruction, faculty meetings, curriculum meetings, and the individual work of specific client groups.

- Robert Grover and Jack Glazier, “Information Transfer in City Government,” Public Library Quarterly 5 (Winter 1984): 9-27.

- Roger C. Greer, “Information Transfer: A Conceptual Model for Librarianship, Information Science and Information Management with Implications for Library Education,” Great Plains Libraries 20(1982):2-15.

- Martha L. Hale, A Structured Observation Study of the Nature of City Managers (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California, 1983).

Article Views (Last 12 Months)

Contact ACRL for article usage statistics from 2010-April 2017.

Article Views (By Year/Month)

© 2024 Association of College and Research Libraries , a division of the American Library Association

Print ISSN: 0099-0086 | Online ISSN: 2150-6698

ALA Privacy Policy

ISSN: 2150-6698

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

32 Observational Research

Learning objectives.

- List the various types of observational research methods and distinguish between each.

- Describe the strengths and weakness of each observational research method.

What Is Observational Research?

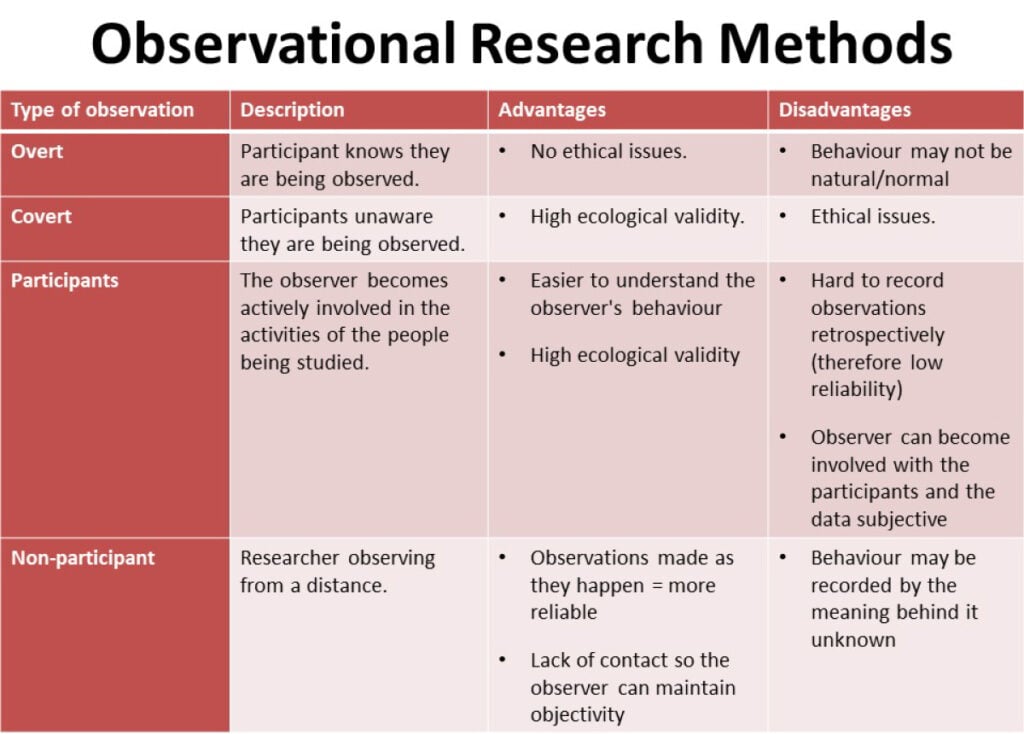

The term observational research is used to refer to several different types of non-experimental studies in which behavior is systematically observed and recorded. The goal of observational research is to describe a variable or set of variables. More generally, the goal is to obtain a snapshot of specific characteristics of an individual, group, or setting. As described previously, observational research is non-experimental because nothing is manipulated or controlled, and as such we cannot arrive at causal conclusions using this approach. The data that are collected in observational research studies are often qualitative in nature but they may also be quantitative or both (mixed-methods). There are several different types of observational methods that will be described below.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is an observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field research (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). Jane Goodall’s famous research on chimpanzees is a classic example of naturalistic observation. Dr. Goodall spent three decades observing chimpanzees in their natural environment in East Africa. She examined such things as chimpanzee’s social structure, mating patterns, gender roles, family structure, and care of offspring by observing them in the wild. However, naturalistic observation could more simply involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied. Such an approach is called disguised naturalistic observation . Ethically, this method is considered to be acceptable if the participants remain anonymous and the behavior occurs in a public setting where people would not normally have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behavior that is easily observable by store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, most researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to observe them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of “bathroom behavior” discussed earlier in the book is that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy even in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

In cases where it is not ethical or practical to conduct disguised naturalistic observation, researchers can conduct undisguised naturalistic observation where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior. However, one concern with undisguised naturalistic observation is reactivity. Reactivity refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior. In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, the concern with reactivity is that when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would. This type of reactivity is known as the Hawthorne effect . For instance, you may act much differently in a bar if you know that someone is observing you and recording your behaviors and this would invalidate the study. So disguised observation is less reactive and therefore can have higher validity because people are not aware that their behaviors are being observed and recorded. However, we now know that people often become used to being observed and with time they begin to behave naturally in the researcher’s presence. In other words, over time people habituate to being observed. Think about reality shows like Big Brother or Survivor where people are constantly being observed and recorded. While they may be on their best behavior at first, in a fairly short amount of time they are flirting, having sex, wearing next to nothing, screaming at each other, and occasionally behaving in ways that are embarrassing.

Participant Observation

Another approach to data collection in observational research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. Participant observation is very similar to naturalistic observation in that it involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs. As with naturalistic observation, the data that are collected can include interviews (usually unstructured), notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The only difference between naturalistic observation and participant observation is that researchers engaged in participant observation become active members of the group or situations they are studying. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. Like naturalistic observation, participant observation can be either disguised or undisguised. In disguised participant observation , the researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

In a famous example of disguised participant observation, Leon Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a doomsday cult known as the Seekers, whose members believed that the apocalypse would occur on December 21, 1954. Interested in studying how members of the group would cope psychologically when the prophecy inevitably failed, they carefully recorded the events and reactions of the cult members in the days before and after the supposed end of the world. Unsurprisingly, the cult members did not give up their belief but instead convinced themselves that it was their faith and efforts that saved the world from destruction. Festinger and his colleagues later published a book about this experience, which they used to illustrate the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1956) [1] .

In contrast with undisguised participant observation , the researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation. Once again there are important ethical issues to consider with disguised participant observation. First no informed consent can be obtained and second deception is being used. The researcher is deceiving the participants by intentionally withholding information about their motivations for being a part of the social group they are studying. But sometimes disguised participation is the only way to access a protective group (like a cult). Further, disguised participant observation is less prone to reactivity than undisguised participant observation.

Rosenhan’s study (1973) [2] of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward would be considered disguised participant observation because Rosenhan and his pseudopatients were admitted into psychiatric hospitals on the pretense of being patients so that they could observe the way that psychiatric patients are treated by staff. The staff and other patients were unaware of their true identities as researchers.

Another example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

One of the primary benefits of participant observation is that the researchers are in a much better position to understand the viewpoint and experiences of the people they are studying when they are a part of the social group. The primary limitation with this approach is that the mere presence of the observer could affect the behavior of the people being observed. While this is also a concern with naturalistic observation, additional concerns arise when researchers become active members of the social group they are studying because that they may change the social dynamics and/or influence the behavior of the people they are studying. Similarly, if the researcher acts as a participant observer there can be concerns with biases resulting from developing relationships with the participants. Concretely, the researcher may become less objective resulting in more experimenter bias.

Structured Observation

Another observational method is structured observation . Here the investigator makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation. Often the setting in which the observations are made is not the natural setting. Instead, the researcher may observe people in the laboratory environment. Alternatively, the researcher may observe people in a natural setting (like a classroom setting) that they have structured some way, for instance by introducing some specific task participants are to engage in or by introducing a specific social situation or manipulation.

Structured observation is very similar to naturalistic observation and participant observation in that in all three cases researchers are observing naturally occurring behavior; however, the emphasis in structured observation is on gathering quantitative rather than qualitative data. Researchers using this approach are interested in a limited set of behaviors. This allows them to quantify the behaviors they are observing. In other words, structured observation is less global than naturalistic or participant observation because the researcher engaged in structured observations is interested in a small number of specific behaviors. Therefore, rather than recording everything that happens, the researcher only focuses on very specific behaviors of interest.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used structured observation to study differences in the “pace of life” across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999) [4] . One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to see how long it took them to walk 60 feet. They found that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered 60 feet in just under 13 seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took close to 17 seconds. When structured observation takes place in the complex and even chaotic “real world,” the questions of when, where, and under what conditions the observations will be made, and who exactly will be observed are important to consider. Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process as follows:

“Male and female walking speed over a distance of 60 feet was measured in at least two locations in main downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were flat, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to allow pedestrians to move at potentially maximum speeds. To control for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking alone were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-five men and 35 women were timed in most cities.” (p. 186).

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes data collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some control over important extraneous variables. For example, by making their observations on clear summer days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather on people’s walking speeds. In Levine and Norenzayan’s study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a city sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance.

As another example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to study bowlers’ reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979) [5] . But what “reactions” should they observe? Based on previous research and their own pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included “closed smile,” “open smile,” “laugh,” “neutral face,” “look down,” “look away,” and “face cover” (covering one’s face with one’s hands). The observers committed this list to memory and then practiced by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this study was that bowlers rarely smiled while they still faced the pins. They were much more likely to smile after they turned toward their companions, suggesting that smiling is not purely an expression of happiness but also a form of social communication.

In yet another example (this one in a laboratory environment), Dov Cohen and his colleagues had observers rate the emotional reactions of participants who had just been deliberately bumped and insulted by a confederate after they dropped off a completed questionnaire at the end of a hallway. The confederate was posing as someone who worked in the same building and who was frustrated by having to close a file drawer twice in order to permit the participants to walk past them (first to drop off the questionnaire at the end of the hallway and once again on their way back to the room where they believed the study they signed up for was taking place). The two observers were positioned at different ends of the hallway so that they could read the participants’ body language and hear anything they might say. Interestingly, the researchers hypothesized that participants from the southern United States, which is one of several places in the world that has a “culture of honor,” would react with more aggression than participants from the northern United States, a prediction that was in fact supported by the observational data (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996) [6] .

When the observations require a judgment on the part of the observers—as in the studies by Kraut and Johnston and Cohen and his colleagues—a process referred to as coding is typically required . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviors. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behavior they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behavior. The observers might even record the duration of each behavior. The target behaviors must be defined in such a way that guides different observers to code them in the same way. This difficulty with coding illustrates the issue of interrater reliability, as mentioned in Chapter 4. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding procedure by having multiple raters code the same behaviors independently and then showing that the different observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for example, video recorded a subset of their participants’ reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating good interrater reliability.

One of the primary benefits of structured observation is that it is far more efficient than naturalistic and participant observation. Since the researchers are focused on specific behaviors this reduces time and expense. Also, often times the environment is structured to encourage the behaviors of interest which again means that researchers do not have to invest as much time in waiting for the behaviors of interest to naturally occur. Finally, researchers using this approach can clearly exert greater control over the environment. However, when researchers exert more control over the environment it may make the environment less natural which decreases external validity. It is less clear for instance whether structured observations made in a laboratory environment will generalize to a real world environment. Furthermore, since researchers engaged in structured observation are often not disguised there may be more concerns with reactivity.

Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of an individual. Sometimes case studies are also completed on social units (e.g., a cult) and events (e.g., a natural disaster). Most commonly in psychology, however, case studies provide a detailed description and analysis of an individual. Often the individual has a rare or unusual condition or disorder or has damage to a specific region of the brain.

Like many observational research methods, case studies tend to be more qualitative in nature. Case study methods involve an in-depth, and often a longitudinal examination of an individual. Depending on the focus of the case study, individuals may or may not be observed in their natural setting. If the natural setting is not what is of interest, then the individual may be brought into a therapist’s office or a researcher’s lab for study. Also, the bulk of the case study report will focus on in-depth descriptions of the person rather than on statistical analyses. With that said some quantitative data may also be included in the write-up of a case study. For instance, an individual’s depression score may be compared to normative scores or their score before and after treatment may be compared. As with other qualitative methods, a variety of different methods and tools can be used to collect information on the case. For instance, interviews, naturalistic observation, structured observation, psychological testing (e.g., IQ test), and/or physiological measurements (e.g., brain scans) may be used to collect information on the individual.

HM is one of the most notorious case studies in psychology. HM suffered from intractable and very severe epilepsy. A surgeon localized HM’s epilepsy to his medial temporal lobe and in 1953 he removed large sections of his hippocampus in an attempt to stop the seizures. The treatment was a success, in that it resolved his epilepsy and his IQ and personality were unaffected. However, the doctors soon realized that HM exhibited a strange form of amnesia, called anterograde amnesia. HM was able to carry out a conversation and he could remember short strings of letters, digits, and words. Basically, his short term memory was preserved. However, HM could not commit new events to memory. He lost the ability to transfer information from his short-term memory to his long term memory, something memory researchers call consolidation. So while he could carry on a conversation with someone, he would completely forget the conversation after it ended. This was an extremely important case study for memory researchers because it suggested that there’s a dissociation between short-term memory and long-term memory, it suggested that these were two different abilities sub-served by different areas of the brain. It also suggested that the temporal lobes are particularly important for consolidating new information (i.e., for transferring information from short-term memory to long-term memory).

The history of psychology is filled with influential cases studies, such as Sigmund Freud’s description of “Anna O.” (see Note 6.1 “The Case of “Anna O.””) and John Watson and Rosalie Rayner’s description of Little Albert (Watson & Rayner, 1920) [7] , who allegedly learned to fear a white rat—along with other furry objects—when the researchers repeatedly made a loud noise every time the rat approached him.

The Case of “Anna O.”

Sigmund Freud used the case of a young woman he called “Anna O.” to illustrate many principles of his theory of psychoanalysis (Freud, 1961) [8] . (Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim, and she was an early feminist who went on to make important contributions to the field of social work.) Anna had come to Freud’s colleague Josef Breuer around 1880 with a variety of odd physical and psychological symptoms. One of them was that for several weeks she was unable to drink any fluids. According to Freud,

She would take up the glass of water that she longed for, but as soon as it touched her lips she would push it away like someone suffering from hydrophobia.…She lived only on fruit, such as melons, etc., so as to lessen her tormenting thirst. (p. 9)

But according to Freud, a breakthrough came one day while Anna was under hypnosis.

[S]he grumbled about her English “lady-companion,” whom she did not care for, and went on to describe, with every sign of disgust, how she had once gone into this lady’s room and how her little dog—horrid creature!—had drunk out of a glass there. The patient had said nothing, as she had wanted to be polite. After giving further energetic expression to the anger she had held back, she asked for something to drink, drank a large quantity of water without any difficulty, and awoke from her hypnosis with the glass at her lips; and thereupon the disturbance vanished, never to return. (p.9)

Freud’s interpretation was that Anna had repressed the memory of this incident along with the emotion that it triggered and that this was what had caused her inability to drink. Furthermore, he believed that her recollection of the incident, along with her expression of the emotion she had repressed, caused the symptom to go away.

As an illustration of Freud’s theory, the case study of Anna O. is quite effective. As evidence for the theory, however, it is essentially worthless. The description provides no way of knowing whether Anna had really repressed the memory of the dog drinking from the glass, whether this repression had caused her inability to drink, or whether recalling this “trauma” relieved the symptom. It is also unclear from this case study how typical or atypical Anna’s experience was.

Case studies are useful because they provide a level of detailed analysis not found in many other research methods and greater insights may be gained from this more detailed analysis. As a result of the case study, the researcher may gain a sharpened understanding of what might become important to look at more extensively in future more controlled research. Case studies are also often the only way to study rare conditions because it may be impossible to find a large enough sample of individuals with the condition to use quantitative methods. Although at first glance a case study of a rare individual might seem to tell us little about ourselves, they often do provide insights into normal behavior. The case of HM provided important insights into the role of the hippocampus in memory consolidation.

However, it is important to note that while case studies can provide insights into certain areas and variables to study, and can be useful in helping develop theories, they should never be used as evidence for theories. In other words, case studies can be used as inspiration to formulate theories and hypotheses, but those hypotheses and theories then need to be formally tested using more rigorous quantitative methods. The reason case studies shouldn’t be used to provide support for theories is that they suffer from problems with both internal and external validity. Case studies lack the proper controls that true experiments contain. As such, they suffer from problems with internal validity, so they cannot be used to determine causation. For instance, during HM’s surgery, the surgeon may have accidentally lesioned another area of HM’s brain (a possibility suggested by the dissection of HM’s brain following his death) and that lesion may have contributed to his inability to consolidate new information. The fact is, with case studies we cannot rule out these sorts of alternative explanations. So, as with all observational methods, case studies do not permit determination of causation. In addition, because case studies are often of a single individual, and typically an abnormal individual, researchers cannot generalize their conclusions to other individuals. Recall that with most research designs there is a trade-off between internal and external validity. With case studies, however, there are problems with both internal validity and external validity. So there are limits both to the ability to determine causation and to generalize the results. A final limitation of case studies is that ample opportunity exists for the theoretical biases of the researcher to color or bias the case description. Indeed, there have been accusations that the woman who studied HM destroyed a lot of her data that were not published and she has been called into question for destroying contradictory data that didn’t support her theory about how memories are consolidated. There is a fascinating New York Times article that describes some of the controversies that ensued after HM’s death and analysis of his brain that can be found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/magazine/the-brain-that-couldnt-remember.html?_r=0

Archival Research

Another approach that is often considered observational research involves analyzing archival data that have already been collected for some other purpose. An example is a study by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on “implicit egotism”—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are similar to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005) [9] . In one study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to the states of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

As with naturalistic observation, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival data. For example, counting the number of people named Virginia who live in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been collected many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988) [10] . In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men’s questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory style—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More pessimistic people tend to blame themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect limited negative consequences. To obtain a measure of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and any causal explanations for them were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three separate dimensions of optimism-pessimism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men’s explanatory style as undergraduate students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as undergraduate students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson’s r was +.25.

This method is an example of content analysis —a family of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Just as structured observation requires specifying the behaviors of interest and then noting them as they occur, content analysis requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the data. These occurrences can then be counted, timed (e.g., the amount of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a variety of other ways.

Media Attributions

- What happens when you remove the hippocampus? – Sam Kean by TED-Ed licensed under a standard YouTube License

- Pappenheim 1882 by unknown is in the Public Domain .

- Festinger, L., Riecken, H., & Schachter, S. (1956). When prophecy fails: A social and psychological study of a modern group that predicted the destruction of the world. University of Minnesota Press. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

- Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. ↵

- Levine, R. V., & Norenzayan, A. (1999). The pace of life in 31 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30 , 178–205. ↵

- Kraut, R. E., & Johnston, R. E. (1979). Social and emotional messages of smiling: An ethological approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 , 1539–1553. ↵

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An "experimental ethnography." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (5), 945-960. ↵

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3 , 1–14. ↵

- Freud, S. (1961). Five lectures on psycho-analysis . New York, NY: Norton. ↵

- Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Jones, J. T. (2005). Implicit egotism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 , 106–110. ↵

- Peterson, C., Seligman, M. E. P., & Vaillant, G. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55 , 23–27. ↵

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on recording systemic observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything.

An observational method that involves observing people’s behavior in the environment in which it typically occurs.

When researchers engage in naturalistic observation by making their observations as unobtrusively as possible so that participants are not aware that they are being studied.

Where the participants are made aware of the researcher presence and monitoring of their behavior.

Refers to when a measure changes participants’ behavior.

In the case of undisguised naturalistic observation, it is a type of reactivity when people know they are being observed and studied, they may act differently than they normally would.

Researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying.

Researchers pretend to be members of the social group they are observing and conceal their true identity as researchers.

Researchers become a part of the group they are studying and they disclose their true identity as researchers to the group under investigation.

When a researcher makes careful observations of one or more specific behaviors in a particular setting that is more structured than the settings used in naturalistic or participant observation.

A part of structured observation whereby the observers use a clearly defined set of guidelines to "code" behaviors—assigning specific behaviors they are observing to a category—and count the number of times or the duration that the behavior occurs.

An in-depth examination of an individual.

A family of systematic approaches to measurement using qualitative methods to analyze complex archival data.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Chapter 13. Participant Observation

Introduction.

Although there are many possible forms of data collection in the qualitative researcher’s toolkit, the two predominant forms are interviewing and observing. This chapter and the following chapter explore observational data collection. While most observers also include interviewing, many interviewers do not also include observation. It takes some special skills and a certain confidence to be a successful observer. There is also a rich tradition of what I am going to call “deep ethnography” that will be covered in chapter 14. In this chapter, we tackle the basics of observational data collection.

What is Participant Observation?

While interviewing helps us understand how people make sense of their worlds, observing them helps us understand how they act and behave. Sometimes, these actions and behaviors belie what people think or say about their beliefs and values and practices. For example, a person can tell you they would never racially discriminate, but observing how they actually interact with racialized others might undercut those statements. This is not always about dishonesty. Most of us tend to act differently than we think we do or think we should. That is part of being human. If you are interested in what people say and believe , interviewing is a useful technique for data collection. If you are interested in how people act and behave , observing them is essential. And if you want to know both, particularly how thinking/believing and acting/behaving complement or contradict each other, then a combination of interviewing and observing is ideal.

There are a variety of terms we use for observational data collection, from ethnography to fieldwork to participant observation . Many researchers use these terms fairly interchangeably, but here I will separately define them. The subject of this chapter is observation in general, or participant observation, to highlight the fact that observers can also be participants. The subject of chapter 14 will be deep ethnography , a particularly immersive form of study that is attractive for a certain subset of qualitative researchers. Both participant observation and deep ethnography are forms of fieldwork in which the researcher leaves their office and goes into a natural setting to record observations that take place in that setting. [1]

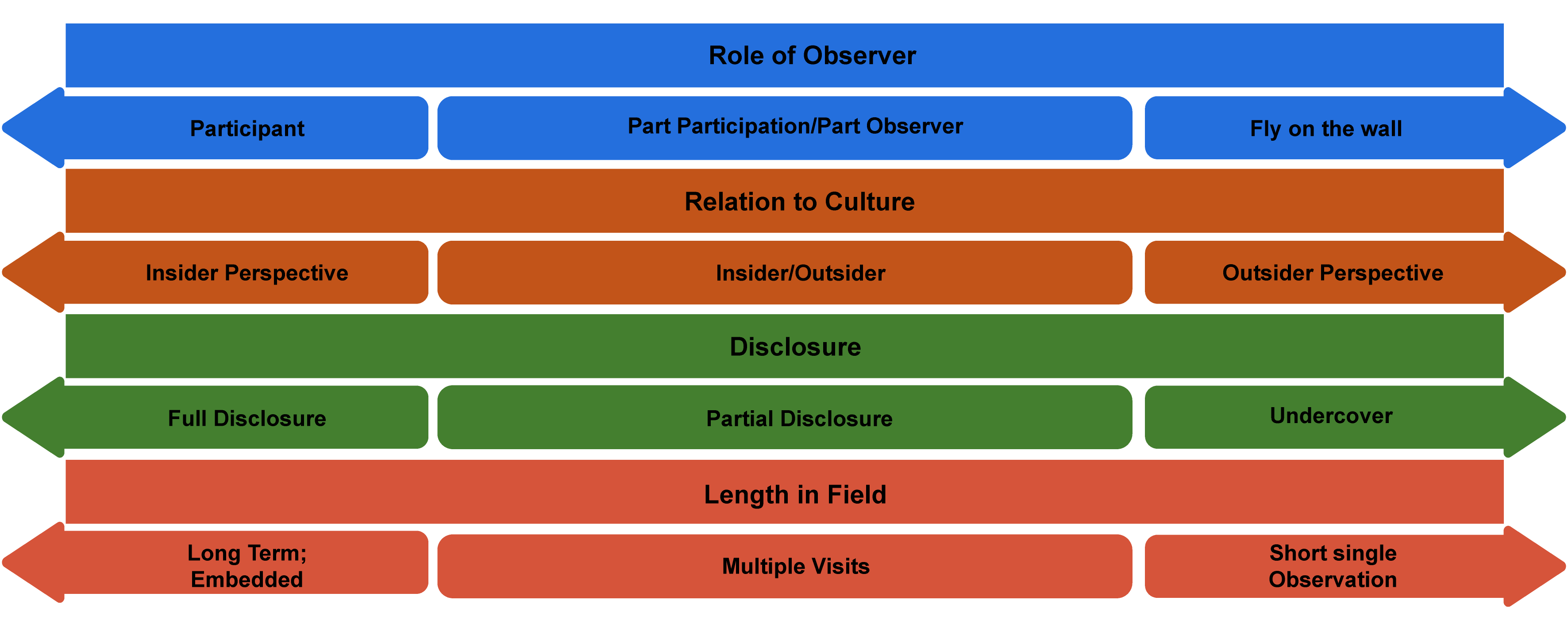

Participant observation (PO) is a field approach to gathering data in which the researcher enters a specific site for purposes of engagement or observation. Participation and observation can be conceptualized as a continuum, and any given study can fall somewhere on that line between full participation (researcher is a member of the community or organization being studied) and observation (researcher pretends to be a fly on the wall surreptitiously but mostly by permission, recording what happens). Participant observation forms the heart of ethnographic research, an approach, if you remember, that seeks to understand and write about a particular culture or subculture. We’ll discuss what I am calling deep ethnography in the next chapter, where researchers often embed themselves for months if not years or even decades with a particular group to be able to fully capture “what it’s like.” But there are lighter versions of PO that can form the basis of a research study or that can supplement or work with other forms of data collection, such as interviews or archival research. This chapter will focus on these lighter versions, although note that much of what is said here can also apply to deep ethnography (chapter 14).

PO methods of gathering data present some special considerations—How involved is the researcher? How close is she to the subjects or site being studied? And how might her own social location—identity, position—affect the study? These are actually great questions for any kind of qualitative data collection but particularly apt when the researcher “enters the field,” so to speak. It is helpful to visualize where one falls on a continuum or series of continua (figure 13.1).

Let’s take a few examples and see how these continua work. Think about each of the following scenarios, and map them onto the possibilities of figure 13.1:

- a nursing student during COVID doing research on patient/doctor interactions in the ICU

- a graduate student accompanying a police officer during her rounds one day in a part of the city the graduate student has never visited

- a professor raised Amish who goes back to her hometown to conduct research on Amish marriage practices for one month

- (What if the sociologist was also a member of the OCF board and camping crew?)

Depending on how the researcher answers those questions and where they stand on the P.O. continuum, various techniques will be more or less effective. For example, in cases where the researcher is a participant, writing reflective fieldnotes at the end of the day may be the primary form of data collected. After all, if the researcher is fully participating, they probably don’t have the time or ability to pull out a notepad and ask people questions. On the other side, when a researcher is more of an observer, this is exactly what they might do, so long as the people they are interrogating are able to answer while they are going about their business. The more an observer, the more likely the researcher will engage in relatively structured interviews (using techniques discussed in chapters 11 and 12); the more a participant, the more likely casual conversations or “unstructured interviews” will form the core of the data collected. [2]

Observation and Qualitative Traditions

Observational techniques are used whenever the researcher wants to document actual behaviors and practices as they happen (not as they are explained or recorded historically). Many traditions of inquiry employ observational data collection, but not all traditions employ them in the same way. Chapter 14 will cover one very specific tradition: ethnography. Because the word ethnography is sometimes used for all fieldwork, I am calling the subject of chapter 14 deep ethnography, those studies that take as their focus the documentation through the description of a culture or subculture. Deeply immersive, this tradition of ethnography typically entails several months or even years in the field. But there are plenty of other uses of observation that are less burdensome to the researcher.

Grounded Theory, in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction, is amenable to both interviewing and observing forms of data collection, and some of the best Grounded Theory works employ a deft combination of both. Often closely aligned with Grounded Theory in sociology is the tradition of symbolic interactionism (SI). Interviews and observations in combination are necessary to properly address the SI question, What common understandings give meaning to people’s interactions ? Gary Alan Fine’s body of work fruitfully combines interviews and observations to build theory in response to this SI question. His Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction is based on field observation and interviews at the Storm Prediction Center in Oklahoma; the National Weather Service in Washington, DC; and a few regional weather forecasting outlets in the Midwest. Using what he heard and what he observed, he builds a theory of weather forecasting based on social and cultural factors that take place inside local offices. In Morel Tales: The Culture of Mushrooming , Fine investigates the world of mushroom hunters through participant observation and interviews, eventually building a theory of “naturework” to describe how the meanings people hold about the world are constructed and are socially organized—our understanding of “nature” is based on human nature, if you will.

Phenomenology typically foregrounds interviewing, as the purpose of this tradition is to gather people’s understandings and meanings about a phenomenon. However, it is quite common for phenomenological interviewing to be supplemented with some observational data, especially as a check on the “reality” of the situations being described by those interviewed. In my own work, for example, I supplemented primary interviews with working-class college students with some participant observational work on the campus in which they were studying. This helped me gather information on the general silence about class on campus, which made the salience of class in the interviews even more striking ( Hurst 2010a ).

Critical theories such as standpoint approaches, feminist theory, and Critical Race Theory are often multimethod in design. Interviews, observations (possibly participation), and archival/historical data are all employed to gather an understanding of how a group of persons experiences a particular setting or institution or phenomenon and how things can be made more just . In Making Elite Lawyers , Robert Granfield ( 1992 ) drew on both classroom observations and in-depth interviews with students to document the conservatizing effects of the Harvard legal education on working-class students, female students, and students of color. In this case, stories recounted by students were amplified by searing examples of discrimination and bias observed by Granfield and reported in full detail through his fieldnotes.

Entry Access and Issues

Managing your entry into a field site is one of the most important and nerve-wracking aspects of doing ethnographic research. Unlike interviews, which can be conducted in neutral settings, the field is an actual place with its own rules and customs that you are seeking to explore. How you “gain access” will depend on what kind of field you are entering. If your field site is a physical location with walls and a front desk (such as an office building or an elementary school), you will need permission from someone in the organization to enter and to conduct your study. Negotiating this might take weeks or even months. If your field site is a public site (such as a public dog park or city sidewalks), there is no “official” gatekeeper, but you will still probably need to find a person present at the site who can vouch for you (e.g., other dog owners or people hanging out on their stoops). [3] And if your field site is semipublic, as in a shopping mall, you might have to weigh the pros and cons of gaining “official” permission, as this might impede your progress or be difficult to ascertain whose permission to request. If you recall, many of the ethical dilemmas discussed in chapter 7 were about just such issues.

Even with official (or unofficial) permission to enter the site, however, your quest to gain access is not done. You will still need to gain the trust and permission of the people you encounter at that site. If you are a mere observer in a public setting, you probably do not need each person you observe to sign a consent form, but if you are a participant in an event or enterprise who is also taking notes and asking people questions, you probably do. Each study is unique here, so I recommend talking through the ethics of permission and consent seeking with a faculty mentor.

A separate but related issue from permission is how you will introduce yourself and your presence. How you introduce yourself to people in the field will depend very much on what level of participation you have chosen as well as whether you are an insider or outsider. Sometimes your presence will go unremarked, whereas other times you may stick out like a very sore thumb. Lareau ( 2021 ) advises that you be “vague but accurate” when explaining your presence. You don’t want to use academic jargon (unless your field is the academy!) that would be off-putting to the people you meet. Nor do you want to deceive anyone. “Hi, I’m Allison, and I am here to observe how students use career services” is accurate and simple and more effective than “I am here to study how race, class, and gender affect college students’ interactions with career services personnel.”

Researcher Note

Something that surprised me and that I still think about a lot is how to explain to respondents what I’m doing and why and how to help them feel comfortable with field work. When I was planning fieldwork for my dissertation, I was thinking of it from a researcher’s perspective and not from a respondent’s perspective. It wasn’t until I got into the field that I started to realize what a strange thing I was planning to spend my time on and asking others to allow me to do. Like, can I follow you around and write notes? This varied a bit by site—it was easier to ask to sit in on meetings, for example—but asking people to let me spend a lot of time with them was awkward for me and for them. I ended up asking if I could shadow them, a verb that seemed to make clear what I hoped to be able to do. But even this didn’t get around issues like respondents’ self-consciousness or my own. For example, respondents sometimes told me that their lives were “boring” and that they felt embarrassed to have someone else shadow them when they weren’t “doing anything.” Similarly, I would feel uncomfortable in social settings where I knew only one person. Taking field notes is not something to do at a party, and when introduced as a researcher, people would sometimes ask, “So are you researching me right now?” The answer to that is always yes. I figured out ways of taking notes that worked (I often sent myself text messages with jotted notes) and how to get more comfortable explaining what I wanted to be able to do (wanting to see the campus from the respondent’s perspective, for example), but it is still something I work to improve.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life and coauthor of Geographies of Campus Inequality

Reflexivity in Fieldwork

As always, being aware of who you are, how you are likely to be read by others in the field, and how your own experiences and understandings of the world are likely to affect your reading of others in the field are all very important to conducting successful research. When Annette Lareau ( 2021 ) was managing a team of graduate student researchers in her study of parents and children, she noticed that her middle-class graduate students took in stride the fact that children called adults by their first names, while her working-class-origin graduate students “were shocked by what they considered the rudeness and disrespect middle-class children showed toward their parents and other adults” ( 151 ). This “finding” emerged from particular fieldnotes taken by particular research assistants. Having graduate students with different class backgrounds turned out to be useful. Being reflexive in this case meant interrogating one’s own expectations about how children should act toward adults. Creating thick descriptions in the fieldnotes (e.g., describing how children name adults) is important, but thinking about one’s response to those descriptions is equally so. Without reflection, it is possible that important aspects never even make it into the fieldnotes because they seem “unremarkable.”

The Data of Observational Work: Fieldnotes

In interview data collection, recordings of interviews are transcribed into the data of the study. This is not possible for much PO work because (1) aural recordings of observations aren’t possible and (2) conversations that take place on-site are not easily recorded. Instead, the participant observer takes notes, either during the fieldwork or at the day’s end. These notes, called “fieldnotes,” are then the primary form of data for PO work.

Writing fieldnotes takes a lot of time. Because fieldnotes are your primary form of data, you cannot be stingy with the time it takes. Most practitioners suggest it takes at least the same amount of time to write up notes as it takes to be in the field, and many suggest it takes double the time. If you spend three hours at a meeting of the organization you are observing, it is a good idea to set aside five to six hours to write out your fieldnotes. Different researchers use different strategies about how and when to do this. Somewhat obviously, the earlier you can write down your notes, the more likely they are to be accurate. Writing them down at the end of the day is thus the default practice. However, if you are plainly exhausted, spending several hours trying to recall important details may be counterproductive. Writing fieldnotes the next morning, when you are refreshed and alert, may work better.

Reseaarcher Note

How do you take fieldnotes ? Any advice for those wanting to conduct an ethnographic study?

Fieldnotes are so important, especially for qualitative researchers. A little advice when considering how you approach fieldnotes: Record as much as possible! Sometimes I write down fieldnotes, and I often audio-record them as well to transcribe later. Sometimes the space to speak what I observed is helpful and allows me to be able to go a little more in-depth or to talk out something that I might not quite have the words for just yet. Within my fieldnote, I include feelings and think about the following questions: How do I feel before data collection? How did I feel when I was engaging/watching? How do I feel after data collection? What was going on for me before this particular data collection? What did I notice about how folks were engaging? How were participants feeling, and how do I know this? Is there anything that seems different than other data collections? What might be going on in the world that might be impacting the participants? As a qualitative researcher, it’s also important to remember our own influences on the research—our feelings or current world news may impact how we observe or what we might capture in fieldnotes.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

What should be included in those fieldnotes? The obvious answer is “everything you observed and heard relevant to your research question.” The difficulty is that you often don’t know what is relevant to your research question when you begin, as your research question itself can develop and transform during the course of your observations. For example, let us say you begin a study of second-grade classrooms with the idea that you will observe gender dynamics between both teacher and students and students and students. But after five weeks of observation, you realize you are taking a lot of notes about how teachers validate certain attention-seeking behaviors among some students while ignoring those of others. For example, when Daisy (White female) interrupts a discussion on frogs to tell everyone she has a frog named Ribbit, the teacher smiles and asks her to tell the students what Ribbit is like. In contrast, when Solomon (Black male) interrupts a discussion on the planets to tell everyone his big brother is called Jupiter by their stepfather, the teacher frowns and shushes him. These notes spark interest in how teachers favor and develop some students over others and the role of gender, race, and class in these teacher practices. You then begin to be much more careful in recording these observations, and you are a little less attentive to the gender dynamics among students. But note that had you not been fairly thorough in the first place, these crucial insights about teacher favoritism might never have been made.

Here are some suggestions for things to include in your fieldnotes as you begin: (1) descriptions of the physical setting; (2) people in the site: who they are and how they interact with one another (what roles they are taking on); and (3) things overheard: conversations, exchanges, questions. While you should develop your own personal system for organizing these fieldnotes (computer vs. printed journal, for example), at a minimum, each set of fieldnotes should include the date, time in the field, persons observed, and location specifics. You might also add keywords to each set so that you can search by names of participants, dates, and locations. Lareau ( 2021:167 ) recommends covering the following key issues, which mnemonically spell out WRITE— W : who, what, when, where, how; R: reaction (responses to the action in question and the response to the response); I: inaction (silence or nonverbal response to an action); T: timing (how slowly or quickly someone is speaking); and E: emotions (nonverbal signs of emotion and/or stoicism).

In addition to the observational fieldnotes, if you have time, it is a good practice to write reflective memos in which you ask yourself what you have learned (either about the study or about your abilities in the field). If you don’t have time to do this for every set of fieldnotes, at least get in the practice of memoing at certain key junctures, perhaps after reading through a certain number of fieldnotes (e.g., every third day of fieldnotes, you set aside two hours to read through the notes and memo). These memos can then be appended to relevant fieldnotes. You will be grateful for them when it comes time to analyze your data, as they are a preliminary by-the-seat-of-your-pants analysis. They also help steer you toward the study you want to pursue rather than allow you to wallow in unfocused data.

Ethics of Fieldwork

Because most fieldwork requires multiple and intense interactions (even if merely observational) with real living people as they go about their business, there are potentially more ethical choices to be made. In addition to the ethics of gaining entry and permission discussed above, there are issues of accurate representation, of respecting privacy, of adequate financial compensation, and sometimes of financial and other forms of assistance (when observing/interacting with low-income persons or other marginalized populations). In other words, the ethical decision of fieldwork is never concluded by obtaining a signature on a consent form. Read this brief selection from Pascale’s ( 2021 ) methods description (observation plus interviews) to see how many ethical decisions she made:

Throughout I kept detailed ethnographic field and interview records, which included written notes, recorded notes, and photographs. I asked everyone who was willing to sit for a formal interview to speak only for themselves and offered each of them a prepaid Visa Card worth $25–40. I also offered everyone the opportunity to keep the card and erase the tape completely at any time they were dissatisfied with the interview in any way. No one asked for the tape to be erased; rather, people remarked on the interview being a really good experience because they felt heard. Each interview was professionally transcribed and for the most part the excerpts in this book are literal transcriptions. In a few places, the excerpta have been edited to reduce colloquial features of speech (e.g., you know, like, um) and some recursive elements common to spoken language. A few excerpts were placed into standard English for clarity. I made this choice for the benefit of readers who might otherwise find the insights and ideas harder to parse in the original. However, I have to acknowledge this as an act of class-based violence. I tried to keep the original phrasing whenever possible. ( 235 )

Summary Checklist for Successful Participant Observation

The following are ten suggestions for being successful in the field, slightly paraphrased from Patton ( 2002:331 ). Here, I take those ten suggestions and turn them into an extended “checklist” to use when designing and conducting fieldwork.

- Consider all possible approaches to your field and your position relative to that field (see figure 13.2). Choose wisely and purposely. If you have access to a particular site or are part of a particular culture, consider the advantages (and disadvantages) of pursuing research in that area. Clarify the amount of disclosure you are willing to share with those you are observing, and justify that decision.

- Take thorough and descriptive field notes. Consider how you will record them. Where your research is located will affect what kinds of field notes you can take and when, but do not fail to write them! Commit to a regular recording time. Your field notes will probably be the primary data source you collect, so your study’s success will depend on thick descriptions and analytical memos you write to yourself about what you are observing.

- Permit yourself to be flexible. Consider alternative lines of inquiry as you proceed. You might enter the field expecting to find something only to have your attention grabbed by something else entirely. This is perfectly fine (and, in some traditions, absolutely crucial for excellent results). When you do see your attention shift to an emerging new focus, take a step back, look at your original research design, and make careful decisions about what might need revising to adapt to these new circumstances.

- Include triangulated data as a means of checking your observations. If you are that ICU nurse watching patient/doctor interactions, you might want to add a few interviews with patients to verify your interpretation of the interaction. Or perhaps pull some public data on the number of arrests for jaywalking if you are the student accompanying police on their rounds to find out if the large number of arrests you witnessed was typical.

- Respect the people you are witnessing and recording, and allow them to speak for themselves whenever possible. Using direct quotes (recorded in your field notes or as supplementary recorded interviews) is another way to check the validity of the analyses of your observations. When designing your research, think about how you can ensure the voices of those you are interested in get included.

- Choose your informants wisely. Who are they relative to the field you are exploring? What are the limitations (ethical and strategic) in using those particular informants, guides, and gatekeepers? Limit your reliance on them to the extent possible.

- Consider all the stages of fieldwork, and have appropriate plans for each. Recognize that different talents are required at different stages of the data-collection process. In the beginning, you will probably spend a great deal of time building trust and rapport and will have less time to focus on what is actually occurring. That’s normal. Later, however, you will want to be more focused on and disciplined in collecting data while also still attending to maintaining relationships necessary for your study’s success. Sometimes, especially when you have been invited to the site, those granting access to you will ask for feedback. Be strategic about when giving that feedback is appropriate. Consider how to extricate yourself from the site and the participants when your study is coming to an end. Have an ethical exit plan.

- Allow yourself to be immersed in the scene you are observing. This is true even if you are observing a site as an outsider just one time. Make an effort to see things through the eyes of the participants while at the same time maintaining an analytical stance. This is a tricky balance to do, of course, and is more of an art than a science. Practice it. Read about how others have achieved it.

- Create a practice of separating your descriptive notes from your analytical observations. This may be as clear as dividing a sheet of paper into two columns, one for description only and the other for questions or interpretation (as we saw in chapter 11 on interviewing), or it may mean separating out the time you dedicate to descriptions from the time you reread and think deeply about those detailed descriptions. However you decide to do it, recognize that these are two separate activities, both of which are essential to your study’s success.

- As always with qualitative research, be reflective and reflexive. Do not forget how your own experience and social location may affect both your interpretation of what you observe and the very things you observe themselves (e.g., where a patient says more forgiving things about an observably rude doctor because they read you, a nursing student, as likely to report any negative comments back to the doctor). Keep a research journal!

Further Readings

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press. Excellent guide that uses actual unfinished fieldnote to illustrate various options for composing, reviewing, and incorporating fieldnote into publications.

Lareau, Annette. 2021. Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All Up . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Includes actual fieldnote from various studies with a really helpful accompanying discussion about how to improve them!

Wolfinger, Nicholas H. 2002. “On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2(1):85–95. Uses fieldnote from various sources to show how the researcher’s expectations and preexisting knowledge affect what gets written about; offers strategies for taking useful fieldnote.

- Note that leaving one’s office to interview someone in a coffee shop would not be considered fieldwork because the coffee shop is not an element of the study. If one sat down in a coffee shop and recorded observations, then this would be fieldwork. ↵

- This is one reason why I have chosen to discuss deep ethnography in a separate chapter (chapter 14). ↵