- Print this article

The State of Research in Veterans Studies: A Systematic Literature Review

- Janani Chandrasekar

- Janani Chandrasekar , San Jose State University, United States

New areas of research on veterans are emerging as the field of veterans studies develops and grows. Yet gaps remain in interdisciplinary research efforts on veterans. The research available across disciplines is still too fragmented to coalesce into a full-fledged field of veteran studies, as other categorical, area, and identity fields of study have done so. By surveying research literature of multiple disciplines used in the curricula of higher education-level veteran study programs, this article presents a thematic and integrative review of the state of research contributing to the growing field of veterans studies. Discussion follows about research emerging from within contributing disciplines, the themes across disciplines, and comments on the need for further research as the field of veterans studies continues to mature.

- Page/Article: 46–65

- DOI: 10.21061/jvs.v6i2.191

- Accepted on 13 Sep 2020

- Published on 12 Oct 2020

- Peer Reviewed

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.307-398

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 3 pp.203-304

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 2 pp.107-201

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 75, NO. 1 pp.1-71

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Mental Health Care Use Among U.S. Military Veterans: Results From the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study

- Alexander C. Kline , Ph.D. ,

- Kaitlyn E. Panza , Ph.D. ,

- Brandon Nichter , Ph.D. ,

- Jack Tsai , Ph.D. ,

- Ilan Harpaz-Rotem , Ph.D. ,

- Sonya B. Norman , Ph.D. ,

- Robert H. Pietrzak , Ph.D., M.P.H.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7420-7547

Search for more papers by this author

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6066-9406

Psychiatric and substance use disorders are prevalent among U.S. military veterans, yet many veterans do not engage in treatment. The authors examined characteristics associated with use of mental health care in a nationally representative veteran sample.

Using 2019–2020 data from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study (N=4,069), the authors examined predisposing, enabling, and need factors and perceived barriers to care as correlates of mental health care utilization (psychotherapy, counseling, or pharmacotherapy). Hierarchical logistic regression and relative importance analyses were used.

Among all veterans, 433 (weighted prevalence, 12%) reported current use of mental health care. Among 924 (26%) veterans with a probable mental or substance use disorder, less than a third (weighted prevalence, 27%) reported care utilization. Mental dysfunction (24%), posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity (18%), using the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs as primary health care provider (14%), sleep disorder (12%), and grit (i.e., trait perseverance including decision and commitment to address one’s needs on one’s own; 7%) explained most of the variance in mental health care utilization in this subsample. Grit moderated the relationship between mental dysfunction and use of care; among veterans with high mental dysfunction, those with high grit (23%) were less likely to use services than were those with low grit (53%).

Conclusions:

A minority of U.S. veterans engaged in mental health care. Less stigmatized need factors (e.g., functioning and sleep difficulties) may facilitate engagement. The relationship between protective and need factors may help inform understanding of veterans’ decision making regarding treatment seeking and outreach efforts.

Only 12% of all veterans in the full sample and 27% of those who screened positive for mental or substance use disorder reported current mental health treatment utilization.

Need factors, such as mental and cognitive functioning, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and sleep-related difficulties, were most predictive of utilization.

Perceived stigma and barriers to care explained minimal variance in use of mental health care but were endorsed by a meaningful number of veterans.

Among veterans with lower mental functioning, those with high grit were substantially less likely to use services than were those with low grit, suggesting that protective factors may influence the relationship between need factors and care utilization.

Among U.S. military veterans, mental and substance use disorders are prevalent, impairing, and often chronic without treatment ( 1 , 2 ). Although evidence-based interventions are often effective ( 3 – 6 ), up to one-third of veterans with mental disorders do not receive treatment ( 7 , 8 ). Further, even when veterans ultimately engage in services, delayed treatment initiation is common, with one nationally representative study estimating median times of 16 and 2.5 years for pre- and post-9/11 veterans, respectively, between onset of diagnosis and treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( 9 ). To engage more veterans in treatment in a timely manner, it is critical to identify determinants and correlates of mental health care utilization.

Treatment utilization research among veterans has primarily focused on psychotherapy for PTSD ( 10 ). Less is known about other disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, which frequently co-occur with PTSD and each other ( 2 , 11 , 12 ). Additionally, research has primarily examined veterans in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) ( 10 ), yet most veterans receive health care outside the VHA ( 13 ). Only one in five veterans use the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for primary health care ( 2 , 13 , 14 ), and many maintain other health care coverage ( 15 ). Consequently, the prevalence and correlates of mental health care utilization in the population of U.S. veterans remain unknown.

A widely used model to understand use of health care is the behavioral model of health service utilization (BMHSU) ( 16 ), positing that use is determined by predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Predisposing characteristics, such as nonminority ethnic-racial status ( 17 , 18 ) and trauma or combat exposure ( 18 , 19 ), have been linked to higher rates of health care utilization among veterans. Enabling factors, such as unemployment ( 19 ) or closer proximity to services ( 20 ), may also facilitate use. Need factors have been most robustly associated with use ( 19 , 20 ), particularly greater severity of PTSD or depressive symptoms ( 17 , 20 – 23 ), medical conditions ( 19 ), and screening positive for mental or substance use disorders and comorbid psychiatric conditions ( 20 , 24 , 25 ). Researchers have also frequently studied factors related to perceived barriers to care, such as stigma, pragmatic barriers, and treatment-related beliefs. Among veterans, more positive treatment beliefs ( 21 , 24 , 26 , 27 ) and lower perceived stigma ( 14 , 24 , 26 ) have been linked to greater likelihood of mental health care utilization.

Although studies of need factors have often emphasized psychological distress and impairment, we have also examined medical conditions and insomnia, given their associations with mental health ( 28 ), possible links to health care utilization ( 24 , 29 ), and the older age of the veteran population. Further, we have considered the role of protective psychosocial characteristics (e.g., grit, defined as trait perseverance that extends to one’s decision or commitment to address mental health needs on one’s own; dispositional optimism; and purpose in life) as possible need factors, because these factors could inhibit or facilitate use by affecting an individual’s perceived need for services. Given the links of these factors to lower psychological distress ( 30 ), individuals scoring higher on these characteristics may perceive an ability to manage distress on their own, in turn dissuading them from seeking care ( 21 ). Furthermore, these traits may moderate the relation between need-based correlates and mental health care utilization; for example, among individuals with high distress, those with higher grit may be less likely to engage in treatment.

In this study, we applied a BMHSU-informed model of health care utilization that included predisposing, enabling, and need factors and perceived barriers to care to examine the prevalence and correlates of current use of mental health care (i.e., counseling, psychotherapy, or medication) in a nationally representative sample of veterans and a subsample of those with a probable current mental disorder (e.g., PTSD, major depressive disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]) or substance use disorder (e.g., alcohol use or drug use disorder). Veterans with a probable mental or substance use disorder were grouped together, given high diagnostic overlap among these disorders and because they frequently co-occur among U.S. veterans ( 28 , 31 ). We examined correlates of care utilization in the full sample given that functional impairment or distress occur in subclinical or subthreshold conditions ( 32 , 33 ) and to adhere to previous methods in utilization literature ( 24 ). We hypothesized that need factors ( 10 , 17 , 20 – 22 , 24 , 25 ) and fewer barriers to care ( 14 , 21 , 24 , 27 ) would be most strongly associated with use.

Participants, Procedures, and Variables

Data were drawn from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience Veterans Study, a nationally representative survey of 4,069 U.S. military veterans. The human subjects subcommittee of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent. Table S1 in an online supplement to this article describes the study variables, which included predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics and perceived barriers to care.

Data Analyses

Analyses proceeded in five steps. First, exploratory factor analyses combined variables assessing common constructs into one variable (e.g., functional difficulties). Second, in the full sample and a subsample of veterans with a probable mental or substance use disorder (N=924), independent-samples t tests and chi-square analyses compared characteristics of veterans who were engaged in mental health care with those of veterans who were not engaged. Third, hierarchical logistic regression analyses identified independent correlates of care utilization; we entered variables into sequential blocks by using the BMHSU-informed model of health care to determine specific variance explained by each variable cluster. After identifying significant correlates, we incorporated an interaction term to evaluate whether the strongest protective factor moderated the association between the strongest negative correlate and use of health care. Statistics from the final, comprehensive models with each block of variables are reported in Results. Fourth, post hoc analyses of multicomponent variables (e.g., psychological distress and functional difficulties) were conducted to specify features that drove associations with use. Fifth, relative importance analyses ( 34 ) determined relative contributions of each significant variable in predicting use after accounting for intercorrelations among independent variables.

The mean±SD age of the participants was 62±16 years (range 22–99), and 90% (N=3,564) were male (percentages were calculated with poststratification weighting). Most participants were non-Hispanic White (N=3,318, 78%), with 11% (N=296) being non-Hispanic Black, 7% (N=307) Hispanic, and 4% (N=148) other or mixed race. Veterans of all branches were represented (Army, 47% [N=2,707]; Navy, 20% [N=879]; Air Force, 19% [N=955]; Marines, 6% [N=260]; and National Guard, Reserves, or Coast Guard, 8% [N=409]). Overall, 35% (N=1,353) were combat veterans, and 36% (N=1,476) had served for ≥10 years. Nearly all (N=3,989, 98%) reported having health insurance such as Medicare (N=2,399, 47%) or through a current or former employer (N=1,447, 41%) or the VA (N=1,336, 33%); 21% (N=790) reported the VA as their primary source of health care. (Details regarding data collection are presented in the online supplement .)

In the full sample (N=4,069), 433 veterans (weighted prevalence, 12%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=11%–13%) reported current engagement in mental health care, including psychotherapy or counseling (N=243, weighted prevalence, 7%, 95% CI=6%–8%), pharmacotherapy (N=383, weighted prevalence, 10%, 95% CI=9%–11%), or both (N=193, weighted prevalence, 6%, 95% CI=5%–6%). In total, 924 (26%) veterans screened positive on one or more of the respective self-report measures of PTSD, major depressive disorder, GAD, alcohol use disorder, or drug use disorder. Most of these veterans (N=685, weighted prevalence, 73%, 95% CI=71%–76%) reported no current engagement in treatment, and 157 (weighted prevalence, 19%, 95% CI=17%–21%) reported receiving psychotherapy or counseling, 211 (weighted prevalence, 23%, 95% CI=21%–26%) pharmacotherapy, and 129 (weighted prevalence, 16%, 95% CI=13%–18%) both types of treatments.

In the full sample, 10% (N=359) had alcohol use disorder, 9% (N=291) major depressive disorder, 9% (N=313) drug use disorder, 8% (N=229) GAD, and 7% (N=214) PTSD. In the subsample of veterans with a probable mental or substance use disorder (N=924), 40% (N=360) had alcohol use disorder, 37% (N=314) drug use disorder, 33% (N=292) major depressive disorder, 30% (N=232) GAD, and 25% (N=217) PTSD; 62% (N=612) had one probable disorder, 21% (N=190) had two, 10% (N=81) had three, 6% (N=34) had four, and 1% (N=7) had all five.

Bivariate analyses for the two samples are shown in Tables S2 and S3 in the online supplement . Tables 1 and 2 present results of multivariable regression analyses examining correlates of current health care utilization in the full sample and in the subsample with a probable mental or substance use disorder, respectively. Collinearity diagnostics did not reveal multicollinearity in either model, with variance inflation factors for all variables <5. Results from parallel analyses in a subset of veterans (N=3,007, 74%) unlikely to have a mental or substance use disorder per screening measures are available in the online supplement .

a ACES, Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; VA, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

b Cumulative variance is explained in the full multivariable model (Nagelkerke R 2 =0.44).

c Post hoc analyses indicated that the association between psychological distress and mental health treatment use was driven by posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (odds ratio [OR]=1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01–1.04, p<0.001) but not by depression or generalized anxiety disorder symptoms (p>0.11).

d Post hoc analyses indicated that the association between medical conditions and mental health treatment use was driven by sleep disorder (OR=2.51, 95% CI=1.88–3.35, p<0.001), high cholesterol (OR=1.95, 95% CI=1.46–2.60, p<0.001), chronic pain (OR=1.61, 95% CI=1.22–2.14, p=0.001), hypertension (OR=1.38, 95% CI=1.02–1.86, p=0.037), and no previous heart attack (OR=0.36, 95% CI=0.19–0.68, p=0.002) but not by any other conditions (p>0.08).

e Post hoc analyses indicated that the association between functioning and mental health treatment use was driven by worse mental (OR=0.93, 95% CI=0.91–0.96, p<0.001) and cognitive (OR=0.89, 95% CI=0.97–0.99, p=0.009) functioning and better physical functioning (OR=1.02, 95% CI=1.01–1.03, p=0.044) but not by psychosocial functioning (p=0.20).

TABLE 1. Associations between current mental health care utilization and predisposing, enabling, and need factors and barriers to care among U.S. military veterans (N=4,069) a

a Veterans in his subgroup had screened positive for current posttraumatic stress, major depressive, generalized anxiety, alcohol use, or drug use disorder. ACES, Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; VA, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

c Post hoc analyses indicated that the association between psychological distress and mental health treatment utilization was driven by PTSD symptoms (odds ratio [OR]=1.01, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01–1.03, p=0.048) but not by depression or generalized anxiety disorder symptoms (p>0.06).

d Post hoc analyses indicated that the association between number of medical conditions and mental health treatment utilization was primarily driven by sleep disorder (OR=2.50, 95% CI=1.63–3.83, p<0.001), previous concussion or mild traumatic brain injury (OR=2.03, 95% CI=1.16–3.58, p<0.001), high cholesterol (OR=2.20, 95% CI=1.44–3.36, p<0.001), and no previous heart attack (OR=0.28, 95% CI=0.11–0.72, p=0.008) but not by any other conditions (p>0.10).

e Post hoc analyses indicated that the association between functioning and mental health treatment use was driven by worse mental functioning (OR=0.93, 95% CI=0.90–0.95, p<0.001) and better physical functioning (OR=1.02, 95% CI=1.01–1.05, p=0.030) but not by changes in cognitive or psychosocial functioning (p>0.19).

TABLE 2. Associations between current mental health care utilization and predisposing, enabling, and need factors and barriers to care among U.S. military veterans who screened positive for a mental or substance use disorder (N=924) a

Relative importance analysis in the full sample revealed that mental dysfunction (i.e., emotional difficulties, such as anxiety and depression and their impact on social and occupational functioning; 19% relative variance explained [RVE]) and cognitive dysfunction (12% RVE), PTSD symptom severity (12% RVE), chronic pain (9% RVE), and grit (6% RVE) accounted for most of the explained variance in health care utilization. In the subsample, mental dysfunction (24% RVE), PTSD symptom severity (18% RVE), the VA as primary source of health care (14% RVE), sleep disorder (12% RVE), grit (7% RVE), and history of suicide attempt (6% RVE) accounted for most of the explained variance (see Figures S1 and S2 in the online supplement ).

To examine whether the strongest protective correlate—grit—moderated the effect of the strongest need correlate—mental dysfunction—on use of care, we incorporated a mental functioning × grit interaction term into regression models. This interaction was statistically significant in both the full sample (Wald χ 2 =4.82, p=0.028; odds ratio [OR]=0.88, 95% CI=0.78–0.99) and the subsample (Wald χ 2 =7.94, p=0.005; OR=0.80, 95% CI=0.68–0.93). Among veterans with high mental dysfunction, those with high grit (23%) were significantly less likely to use services than were those with low grit (53%) ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1. Probability of mental health treatment among veterans, by mental functioning tertile and level of grit a

a A: full sample of veterans (N=4,069); B: subsample of veterans screening positive for mental or substance use disorder (N=924). Mental functioning tertiles were computed with mental component summary scores from the Short Form–8 Health Survey. The score range for tertile 1 was 8–52 (median=46); tertile 2, 53–58 (median=55); and tertile 3, 59–68 (median=59). Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. A median split procedure was used to stratify groups into low- and high-grit groups; the score range was 1.1–3.7 (median=3.4) for the low-grit group and 3.9–5.0 (median=4.1) for the high-grit group. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. −1 SD and +1 SD refer to one standard deviation below and above the mean for grit, respectively.

In line with literature indicating underuse of mental health care among veterans ( 24 ), we found that only 27% of U.S. veterans with a probable mental or substance use disorder and 12% of U.S. veterans in general were currently engaged in mental health treatment. A key implication of this finding is that available treatments—although often effective—may not be reaching most veterans who could benefit from them. Correlates were generally consistent with literature reporting that need factors are most robustly associated with mental health care utilization ( 10 , 17 , 19 – 22 , 24 , 25 ). However, previous studies have rarely examined need factors that may be protective. This study therefore extends this literature, showing that protective psychosocial factors and their interaction with more commonly studied need characteristics may shed additional light on veterans’ health services use and could help inform strategies to engage veterans in treatment.

As hypothesized, need factors emerged as the strongest correlates of mental health care utilization among veterans. Psychological distress—indexed with a composite variable of depressive, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms—was strongly associated with use of care, primarily driven by PTSD symptoms. Indices of cognitive dysfunction and mental dysfunction were also salient contributors, accounting for nearly a third of the explained variance in care utilization. Previous findings suggest that functional impairment accompanying psychological distress may motivate use of mental health services ( 35 ) and underscore the importance of assessing functioning in addition to psychiatric symptoms to most accurately gauge veterans’ mental health care needs. In the full sample, a diagnosis of a substance use disorder was not associated with mental health care utilization, suggesting that the reasons underlying treatment seeking may differ between individuals with mental or substance use disorders. It is also possible that individuals with a substance use disorder sought treatment through 12-step programs rather than psychotherapy, counseling, or medication.

The relationship between functioning and use of health care was further clarified when considered in the context of protective psychosocial factors. Specifically, grit was negatively associated with use and also moderated the relationship between mental functioning and utilization. Grit is positively correlated with constructs such as self-efficacy and conscientiousness ( 36 , 37 ), suggesting that this factor may reflect individuals’ self-efficacy and belief in their ability to handle mental health difficulties on their own. These traits are often considered assets or strengths (e.g., self-reliance and perseverance), but in the context of help seeking could also be a barrier (e.g., reluctance to seek help). Protective factors were included as need factors within the BMHSU framework, given that they may affect perceived need for services. Our results suggest nuanced relationships between service use and need and protective factors that merit attention.

Veterans who reported higher levels of mental dysfunction and scored lower on a measure of grit were particularly likely to be engaged in treatment, suggesting that these individuals may reflect a particularly distressed subgroup of veterans. Conversely, veterans reporting similar levels of mental dysfunction who scored highly on grit were less likely to be engaged in treatment. This pattern suggests that higher levels of grit among veterans may reduce their likelihood of seeking treatment, even in the presence of clinically meaningful distress. Clinically, our results highlight the potential utility of promoting grit once veterans begin treatment (i.e., leveraging grit to bolster treatment motivation and engagement and emphasizing goal setting). For veterans reporting greater functional impairment and lower protective factors, interventions designed to cultivate personal strengths ( 38 )—in addition to mitigating symptoms and functional difficulties—may be beneficial for boosting treatment engagement and response. Notably, of the four protective factors examined (i.e., resilience, purpose in life, grit, and optimism), only grit was strongly associated with mental health care utilization in the subsample. Our findings therefore need replication, and additional research is needed regarding protective factors, their links to distress, and how these factors affect treatment engagement.

Other need factors linked to greater likelihood of use in both samples included a history of attempted suicide, sleep-related difficulties, and medical burden. Although it is encouraging that veterans with suicide attempt histories were more likely to be engaged in treatment, continued efforts in suicide prevention ( 39 ) are critically needed. Suicide rates among veterans have increased in the past two decades ( 40 ), and 60% of veterans endorsing suicidal ideation are not engaged in mental health treatment ( 26 ). Regarding sleep-related difficulties and medical burden, screening veterans for mental health and substance use and connecting them with needed treatment via integration with primary care and nonmental health clinics are effective methods for increasing care access and boosting use ( 41 , 42 ) and have been increasingly adopted by the VA and other health care settings ( 43 , 44 ). Results suggest that health care systems should continue to leverage this overlap between medical, sleep, and mental health difficulties, because assessment of less stigmatized need factors (i.e., sleep and general medical health) may help identify veterans in need of mental health care. Insomnia treatment, for example, is preferred to PTSD or depression interventions among veterans ( 45 ) and has been theorized as a possible gateway for connecting veterans with needed mental health services ( 45 , 46 ). The broad array of need factors also highlights the significance of interdisciplinary, integrative care, which has been increasingly adopted within the VA and has effectively increased veterans’ mental health care utilization ( 47 ).

Enabling factors were generally unrelated to use of mental health care, a result that aligns with literature indicating that need factors are more consistent and stronger correlates of use. Aside from use of the VA as primary source of health care, only unemployment was linked to use in the full sample, and no other enabling characteristics emerged as correlates in the subsample of veterans with a probable current mental or substance use disorder. Employment was negatively associated with use, possibly because employed veterans have less functional or occupational impairment, have less distress due to financial problems, or have work schedules that interfere with treatment. In both samples, health care users were more likely than nonusers to report the VA as their primary source of health care. Veterans who use the VA tend to have higher rates of psychiatric symptoms, suicidality, trauma exposure, and functional impairment ( 13 ); however, the link between primary VA use and care utilization remained significant even when these factors were controlled for. Primary VA care may thus reflect an enabling factor that facilitates access to mental health care services and increases veterans’ likelihood of using them. Further research should examine specific facets of VA care that may promote mental health care engagement (e.g., no or minimal treatment cost, integrated primary and mental health care, routine mental health screenings, and increased telehealth availability), which may also promote mental health care engagement in non-VA systems.

Predisposing characteristics associated with health care utilization were female sex and deployments and, in the full sample, younger age. This finding highlights the potential importance of tailoring strategies to promote utilization among symptomatic veterans who are male, combat-exposed, and older. Outside the BMHSU framework, perceived stigma and barriers to care explained relatively little variance in utilization. Nevertheless, in the symptomatic subsample, endorsement of “it would be embarrassing to seek treatment” was associated with a highly reduced odds of use, whereas in the full sample, endorsements of “it would harm my reputation” and “mental health care does not work” also were associated with significantly reduced odds of use. Although stigma related to mental health treatment has decreased among U.S. military members in recent years ( 48 ), these findings suggest that continued efforts to combat stigma, such as psychoeducation and promotion of mental health literacy, may help motivate treatment engagement. Fortunately, beliefs regarding stigma are modifiable and unrelated to use once veterans have attended even a single mental health visit ( 22 ).

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precluded examining how changes in correlates over time may affect use of care. Second, screening instruments, rather than semistructured clinical interviews, were used to identify probable mental and substance use disorders. Although the results obtained with the scales we used are known to correlate strongly with results from gold-standard diagnostic interviews ( 49 , 50 ), screening via self-report measures may have inflated estimates of disorder prevalence. Third, because the sample comprised primarily older White male veterans, it is important to understand whether the results generalize to younger, more diverse veterans. Relatedly, although the sample was nationally representative, the participation rate from the larger panel of veterans was only 52%. Although poststratification weights enhanced generalizability of our results to the broader U.S. veteran population, it is possible that more symptomatic veterans may have been less represented in this sample, and homeless and institutionalized veterans were excluded altogether. Fourth, psychotherapy and medication categories were combined because only a small number of veterans engaged in psychotherapy only. This data handling may have limited the specificity of our findings, because correlates of medication and psychotherapy use may differ. Fifth, although we adhered to established theory and literature in classifying variables, some variables could have been placed in more than one cluster (e.g., activities of daily living could be an enabling or need factor). Finally, programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous were not formally assessed and may affect utilization estimates.

Notwithstanding these limitations, strengths of this study included examination of a broad constellation of variables associated with mental health care utilization in a contemporary, nationally representative sample of U.S. veterans. Additionally, correlates examined in this study, including novel indicators of use (i.e., protective factors), explained 44%−50% of the variance in care utilization, thus providing insight into key correlates of use in this population.

Conclusions

Mental health treatments are often not reaching veterans who need them, a deficiency that may be especially pronounced among veterans who are distressed but also have high numbers of protective factors. Our findings underscore the importance for continued research on strategies to reduce stigma and negative beliefs and promote mental health literacy among veterans, particularly regarding the availability of evidence-based mental health interventions. Future work should also more precisely ascertain the impact of protective factors among veterans with mental and substance use disorders; specifically, our understanding of treatment seeking among veterans will be improved by deciphering whether protective factors reflect veterans’ self-reliance and capacity to manage distress on their own or whether they reflect a barrier to seeking help. Better understanding protective factors and their links to distress and impairment may help identify additional veterans who could benefit from care. Another future direction is to evaluate and disseminate self-help tools such as mobile apps and online programs (e.g., PTSD Coach, Virtual Hope Box, and VetChange), which may be treatment options ideal for veterans with high levels of both distress and protective factors and who want to manage mental health and substance use difficulties on their own.

The National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study is supported by the VA National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

The authors thank the veterans who participated in the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study and Steven M. Southwick, M.D., and John H. Krystal, M.D., for their critical input into the design of this study.

1 Fuehrlein BS, Mota N, Arias AJ, et al. : The burden of alcohol use disorders in US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study . Addiction 2016 ; 111:1786–1794 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

2 Wisco BE, Marx BP, Wolf EJ, et al. : Posttraumatic stress disorder in the US veteran population: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study . J Clin Psychiatry 2014 ; 75:1338–1346 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

3 Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Deacon BJ : Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic findings . Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010 ; 33:557–577 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

4 Karlin BE, Brown GK, Trockel M, et al. : National dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system: therapist and patient-level outcomes . J Consult Clin Psychol 2012 ; 80:707–718 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

5 Ray LA, Meredith LR, Kiluk BD, et al. : Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with alcohol or substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis . JAMA Netw Open 2020 ; 3:e208279 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

6 Lewis C, Roberts NP, Andrew M, et al. : Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis . Eur J Psychotraumatol 2020 ; 11:1729633 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

7 Burnett-Zeigler I, Zivin K, Ilgen M, et al. : Depression treatment in older adult veterans . Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012 ; 20:228–238 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

8 Smith NB, Cook JM, Pietrzak R, et al. : Mental health treatment for older veterans newly diagnosed with PTSD: a national investigation . Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016 ; 24:201–212 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

9 Goldberg SB, Simpson TL, Lehavot K, et al. : Mental health treatment delay: a comparison among civilians and veterans of different service eras . Psychiatr Serv 2019 ; 70:358–366 Link , Google Scholar

10 Johnson EM, Possemato K : Correlates and predictors of mental health care utilization for veterans with PTSD: a systematic review . Psychol Trauma 2019 ; 11:851–860 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

11 Rytwinski NK, Scur MD, Feeny NC, et al. : The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis . J Trauma Stress 2013 ; 26:299–309 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

12 Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, et al. : Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment . Drug Alcohol Depend 2011 ; 116:93–101 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

13 Meffert BN, Morabito DM, Sawicki DA, et al. : US veterans who do and do not utilize VA healthcare services: demographic, military, medical, and psychosocial characteristics . Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019 ; 21:18m02350 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

14 Tsai J, Mota NP, Pietrzak RH : US female veterans who do and do not rely on VA health care: needs and barriers to mental health treatment . Psychiatr Serv 2015 ; 66:1200–1206 Link , Google Scholar

15 Shen Y, Hendricks A, Zhang S, et al. : VHA enrollees’ health care coverage and use of care . Med Care Res Rev 2003 ; 60:253–267 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

16 Andersen RM : Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995 ; 36:1–10 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

17 Doran JM, Pietrzak RH, Hoff R, et al. : Psychotherapy utilization and retention in a national sample of veterans with PTSD . J Clin Psychol 2017 ; 73:1259–1279 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

18 Hankin CS, Spiro A 3rd, Miller DR, et al. : Mental disorders and mental health treatment among US Department of Veterans Affairs outpatients: the Veterans Health Study . Am J Psychiatry 1999 ; 156:1924–1930 Abstract , Google Scholar

19 Elhai JD, Grubaugh AL, Richardson JD, et al. : Outpatient medical and mental healthcare utilization models among military veterans: results from the 2001 National Survey of Veterans . J Psychiatr Res 2008 ; 42:858–867 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

20 Hundt NE, Barrera TL, Mott JM, et al. : Predisposing, enabling, and need factors as predictors of low and high psychotherapy utilization in veterans . Psychol Serv 2014 ; 11:281–289 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

21 DeViva JC, Sheerin CM, Southwick SM, et al. : Correlates of VA mental health treatment utilization among OEF/OIF/OND veterans: resilience, stigma, social support, personality, and beliefs about treatment . Psychol Trauma 2016 ; 8:310–318 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

22 Harpaz-Rotem I, Rosenheck RA, Pietrzak RH, et al. : Determinants of prospective engagement in mental health treatment among symptomatic Iraq/Afghanistan veterans . J Nerv Ment Dis 2014 ; 202:97–104 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

23 Hoerster KD, Malte CA, Imel ZE, et al. : Association of perceived barriers with prospective use of VA mental health care among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans . Psychiatr Serv 2012 ; 63:380–382 Link , Google Scholar

24 Blais RK, Tsai J, Southwick SM, et al. : Barriers and facilitators related to mental health care use among older veterans in the United States . Psychiatr Serv 2015 ; 66:500–506 Link , Google Scholar

25 Fasoli DR, Glickman ME, Eisen SV : Predisposing characteristics, enabling resources and need as predictors of utilization and clinical outcomes for veterans receiving mental health services . Med Care 2010 ; 48:288–295 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

26 Nichter B, Hill M, Norman S, et al. : Mental health treatment utilization among US military veterans with suicidal ideation: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study . J Psychiatr Res 2020 ; 130:61–67 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

27 Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, et al. : Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans . Psychiatr Serv 2009 ; 60:1118–1122 Link , Google Scholar

28 Nichter B, Norman S, Haller M, et al. : Psychological burden of PTSD, depression, and their comorbidity in the US veteran population: suicidality, functioning, and service utilization . J Affect Disord 2019 ; 256:633–640 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

29 Lindsay Nour BM, Elhai JD, Ford JD, et al. : The role of physical health functioning, mental health, and sociodemographic factors in determining the intensity of mental health care use among primary care medical patients . Psychol Serv 2009 ; 6:243–252 Crossref , Google Scholar

30 Pietrzak RH, Cook JM : Psychological resilience in older US veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study . Depress Anxiety 2013 ; 30:432–443 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

31 Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Miner CR, et al. : Bringing the war back home: mental health disorders among 103,788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities . Arch Intern Med 2007 ; 167:476–482 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

32 Cukor J, Wyka K, Jayasinghe N, et al. : The nature and course of subthreshold PTSD . J Anxiety Disord 2010 ; 24:918–923 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

33 Rucci P, Gherardi S, Tansella M, et al. : Subthreshold psychiatric disorders in primary care: prevalence and associated characteristics . J Affect Disord 2003 ; 76:171–181 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

34 Tonidaniel S, LeBreton JM : Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis . J Bus Psychol 2011 ; 26:1–9 Crossref , Google Scholar

35 McKibben JBA, Fullerton CS, Gray CL, et al. : Mental health service utilization in the US Army . Psychiatr Serv 2013 ; 64:347–353 Link , Google Scholar

36 Duckworth AL, Quinn PD : Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S) . J Pers Assess 2009 ; 91:166–174 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

37 Duckworth AL, Peterson C, Matthews MD, et al. : Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals . J Pers Soc Psychol 2007 ; 92:1087–1101 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

38 Duckworth AL, Steen TA, Seligman MEP : Positive psychology in clinical practice . Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005 ; 1:629–651 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

39 Tsai J, Snitkin M, Trevisan L, et al. : Awareness of suicide prevention programs among US military veterans . Adm Policy Ment Health 2020 ; 47:115–125 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

40 Department of Veterans Affairs : 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. Washington, DC, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2019 Google Scholar

41 Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al. : Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use . Am J Psychiatry 2004 ; 161:1455–1462 Link , Google Scholar

42 Pomerantz A, Cole BH, Watts BV, et al. : Improving efficiency and access to mental health care: combining integrated care and advanced access . Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008 ; 30:546–551 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

43 Auxier A, Farley T, Seifert K : Establishing an integrated care practice in a community health center . Prof Psychol Res Pr 2011 ; 42:391–397 Crossref , Google Scholar

44 Zeiss AM, Karlin BE : Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system . J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2008 ; 15:73–78 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

45 Gutner CA, Pedersen ER, Drummond SPA : Going direct to the consumer: examining treatment preferences for veterans with insomnia, PTSD, and depression . Psychiatry Res 2018 ; 263:108–114 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

46 Nappi CM, Drummond SPA, Hall JMH : Treating nightmares and insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of current evidence . Neuropharmacology 2012 ; 62:576–585 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

47 Kearney LK, Post EP, Pomerantz AS, et al. : Applying the interprofessional patient aligned care team in the Department of Veterans Affairs: transforming primary care . Am Psychol 2014 ; 69:399–408 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

48 Quartana PJ, Wilk JE, Thomas JL, et al. : Trends in mental health services utilization and stigma in US soldiers from 2002 to 2011 . Am J Public Health 2014 ; 104:1671–1679 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

49 Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. : An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4 . Psychosomatics 2009 ; 50:613–621 Crossref , Medline , Google Scholar

50 Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. : The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) . Washington, DC, US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013 . https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp. Accessed Sep 29 , 2021 Google Scholar

- Smaller rostral cingulate volume and psychosocial correlates in veterans at risk for suicide Psychiatry Research, Vol. 320

- Veterans issues

- Care utilization patterns

- Mental illness

- Alcohol abuse

- Substance use disorder

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key findings about America’s military veterans

This Veterans Day, Americans across the country will honor the service and sacrifice of U.S. military veterans. A recent Pew Research Center survey of veterans found that, for many who served in combat, their experiences strengthened them personally but also made the transition to civilian life difficult.

Here are key facts about veterans, drawn from that survey:

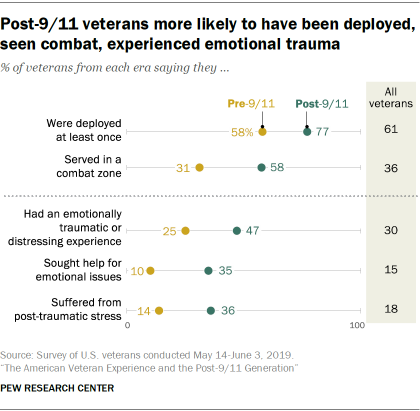

The experiences of post-9/11 veterans differ from those who served in previous eras. About one-in-five veterans today served on active duty after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. These post-9/11 veterans are more likely to have been deployed and to have served in combat, giving them a distinct set of experiences compared with those who served in previous eras.

Post-9/11 veterans are also more likely than their predecessors to bear some of the physical and psychological scars of combat. Roughly half (47%) of post-9/11 veterans say they had emotionally traumatic or distressing experiences related to their military service, compared with one-quarter of pre-9/11 veterans. About a third (35%) of post-9/11 veterans say they sought professional help to deal with those experiences, and a similar share say that – regardless of whether they have sought help – they think they have suffered from post-traumatic stress (PTS).

A majority of veterans say they have felt proud of their service since leaving the military. Roughly two-thirds of all veterans (68%) say, in the first few years after leaving the military, they frequently felt proud of their military service. An additional 22% say they sometimes felt proud, and 9% say they seldom or never felt this way. Pre-9/11 veterans are more likely to say they frequently felt proud of their service than are post-9/11 veterans (70% vs. 58%).

Most veterans say they would endorse the military as a career choice. Roughly eight-in-ten (79%) say they would advise a young person close to them to join the military. This includes large majorities of post-9/11 veterans, combat veterans and those who say they had emotionally traumatic experiences in the military.

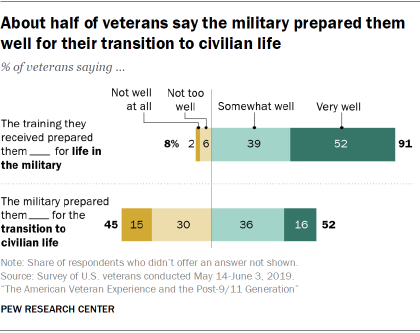

More veterans say the military did a good job preparing them for life in the service than it did in readying them for the transition to civilian life.

Veterans across eras offer similarly positive evaluations of the job the military did preparing them for military life, but less so when it comes to the return to civilian life. Roughly nine-in-ten veterans (91%) say the training they received when they first entered the military prepared them very or somewhat well for military life. By contrast, about half (52%) say the military prepared them very or somewhat well for the transition to civilian life.

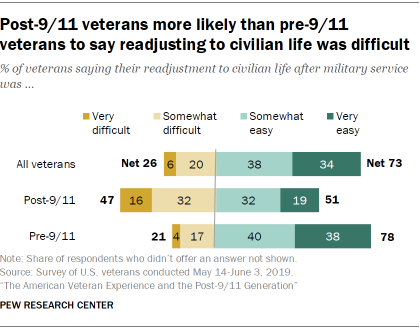

About half of post-9/11 veterans say readjusting to civilian life was difficult. While about three-quarters of all veterans (73%) say readjusting to civilian life was very or somewhat easy, roughly one-in-four (26%) say it was at least somewhat difficult.

There is a significant gap between pre- and post-9/11 veterans in this regard. About half of post-9/11 veterans (47%) say it was very or somewhat difficult for them to readjust to civilian life after their military service. By comparison, only about one-in-five veterans whose service ended before 9/11 (21%) say their transition was very or somewhat difficult. A large majority of pre-9/11 veterans (78%) say it was easy for them to make the transition.

For many veterans, the imprints of war are felt beyond their tour of duty. The challenges some veterans face during the transition to civilian life can be financial, emotional and professional.

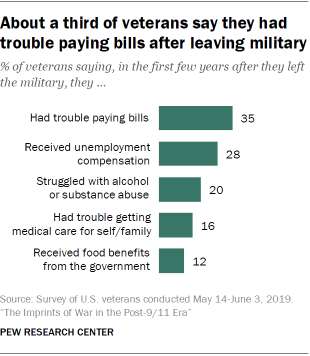

About a third of veterans (35%) say they had trouble paying their bills in their first few years after leaving the military, and roughly three-in-ten (28%) say they received unemployment compensation. One-in-five say they struggled with alcohol or substance abuse.

Veterans who say they have suffered from PTS are much more likely to report experiencing these things than those who did not. Roughly six-in-ten (61%) say they had trouble paying their bills, about four-in-ten (42%) say they had trouble getting medical care for themselves or their families, and a similar share (41%) say they struggled with alcohol or substance abuse.

When it comes to employment, a majority of veterans say their military service was useful in giving them the skills and training they needed for a civilian job. About one-in-three veterans (29%) say it was very useful, and another 29% say it was fairly useful. There are significant differences by rank: While 78% of veterans who served as commissioned officers say their military service was useful, smaller shares of those who were noncommissioned officers (59%) or enlisted (54%) say the same.

Most post-9/11 veterans say having served in the military was an advantage when it came to finding their first post-military job – 35% say this helped a lot and 26% say it helped a little. Only about one-in-ten (9%) say having served in the military hurt their ability to get a job. Among veterans who looked for a job after leaving the military, 57% say they found one in less than six months, and an additional 21% say they had a job in less than a year.

Veterans give the VA mixed reviews.

Most veterans (73%) say they have received benefits from the Department of Veterans Affairs. When asked to assess the job the VA is doing in meeting the needs of veterans, fewer than half (46%) of all veterans say the VA is doing an excellent or good job in this regard.

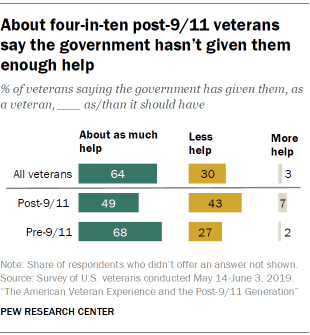

More broadly, 64% of veterans say the government has given them about as much help as it should have. Three-in-ten say the government has given them too little help. Post-9/11 veterans are more likely than those from previous eras to say the government has given them less help than it should have (43% vs. 27%).

Majorities of veterans say the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were not worth fighting. Additional findings from the same survey show that about two-thirds of veterans (64%) say they think the war in Iraq was not worth fighting considering the costs versus the benefits to the United States, while 33% say it was. Similarly, a majority of veterans (58%) say the war in Afghanistan was not worth fighting. About four-in-ten (38%) say it was worth fighting.

Views differ significantly by party. Republican and Republican-leaning veterans are much more likely than veterans who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party to say the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were worth fighting: 45% of Republican veterans vs. 15% of Democratic veterans say the war in Iraq was worth fighting, while 46% of Republican veterans and 26% of Democratic veterans say the same about Afghanistan.

Views on U.S. military engagement in Syria are also more negative than positive. Among veterans, 42% say the campaign in Syria has been worth it, while 55% say it has not. (The survey was conducted entirely before President Donald Trump’s decision to remove U.S. troops from parts of Syria.)

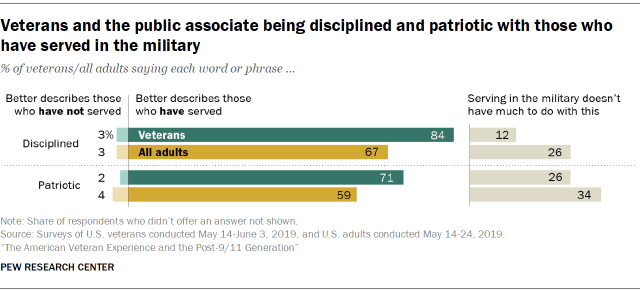

A majority of Americans and veterans associate discipline and patriotism with veterans. Majorities among veterans (61%) and the general public (64%) say most Americans look up to people who have served in the military. And veterans see themselves as more disciplined (84%) and patriotic (71%) than those who have not served in the military. Most Americans agree with this: 67% of all adults say being disciplined better describes veterans than non-veterans, and 59% say the same about being patriotic.

About a third or more among veterans and the public say veterans are more hard-working than those who haven’t served. Still, when it comes to things like being tolerant and open to all groups, the public is less likely to see this as a trait associated with military service than veterans are themselves.

Note: See full topline results and methodology .

- Military & Veterans

Ruth Igielnik is a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center

The changing face of America’s veteran population

A look back at how fear and false beliefs bolstered u.s. public support for war in iraq, new congress will have a few more veterans, but their share of lawmakers is still near a record low, around one-in-five candidates for congress or governor this year are veterans, americans’ trust in scientists, other groups declines, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Subst Abuse Rehabil

Substance use disorders in military veterans: prevalence and treatment challenges

Jenni b teeters.

1 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

2 Ralph H Johnson Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Charleston, SC, USA

Cynthia L Lancaster

Delisa g brown.

3 Department of Human Development and Psychoeducation, Howard University, Washington, DC, USA

Sudie E Back

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a significant problem among our nation’s military veterans. In the following overview, we provide information on the prevalence of SUDs among military veterans, clinical characteristics of SUDs, options for screening and evidence-based treatment, as well as relevant treatment challenges. Among psychotherapeutic approaches, behavioral interventions for the management of SUDs typically involve short-term, cognitive-behavioral therapy interventions. These interventions focus on the identification and modification of maladaptive thoughts and behaviors associated with increased craving, use, or relapse to substances. Additionally, client-centered motivational interviewing approaches focus on increasing motivation to engage in treatment and reduce substance use. A variety of pharmacotherapies have received some support in the management of SUDs, primarily to help with the reduction of craving or withdrawal symptoms. Currently approved medications as well as treatment challenges are discussed.

Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are a significant problem among military veterans and are associated with numerous deleterious effects. 1 – 3 There are a number of services and interventions available to help reduce SUDs among veterans, including both behavioral and pharmacological treatments. The aims of this review are to provide information on the epidemiology of SUDs among military veterans, clinical characteristics of SUDs, and options for screening and treatment. Challenges and barriers to treatment are also discussed. For the purposes of this review, the focus is primarily on veterans who previously served in the military (i.e., are now retired or separated from the military). Additionally, much of the available research on SUDs among military veterans focuses on Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) services and patients. Notably, some of the features of VA care, such as integration and relatively easy access to specialty mental health care and/or treatment for SUDs, which are discussed in this review, may not be present in non-VA treatment settings.

Despite numerous attempts by the VA and other agencies over the past two decades to reduce problematic substance use, rates of SUDs in veterans continue to rise. SUDs are associated with substantial negative correlates, including medical problems, other psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety), interpersonal and vocational impairment, and increased rates of suicidal ideation and attempts. 2 , 4 One study of military personnel found that ~30% of completed suicides were preceded by alcohol or drug use, and an estimated 20% of high-risk behavior deaths were attributed to alcohol or drug overdose. 5 , 6 Given the deleterious associations with SUDs, greater attention to the identification of effective, evidence-based treatment is critically needed. In this paper, we review the prevalence of SUDs among veterans as well as options for treatment. Articles selected for inclusion in this overview were chosen following an extensive literature search in PubMed using relevant key words (e.g., military substance use disorders, veteran substance use disorders, and veteran addiction). Preference for inclusion was given to articles published in the past 10 years.

Diagnostic criteria

SUDs are defined in the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 7 as a pattern of use that results in marked distress and/or impairment, with two or more symptoms occurring in the past year (see Box 1 for DSM-5 diagnostic criteria). The DSM-5 marked the transition of SUD from a categorical model of severity (previously defined as “abuse” or “dependence”) to a more dimensional model in which SUDs are qualified as mild, moderate, or severe, based on the number of symptoms endorsed by the patient. 7

Prevalence rates

Prior to presenting epidemiological data, it is important to note that many VA-based studies published prior to the release of DSM-5 in May 2013 used The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes (which roughly correspond to the DSM-4 criteria). Differences in diagnostic criteria may lead to some important differences in rates of SUDs among those utilizing VA care. For example, previous studies have concluded that prevalence rates of SUDs differ based on the specific criteria used, with studies using diagnostic criteria (i.e., DSM ) reporting higher rates of SUDs when compared to studies using administrative data (i.e., ICD-9). 8 Additionally, because not all veterans choose to utilize VA health care services and only a percentage of patients receive mental health care through the VA and receive a diagnosis, VA diagnostic rates may not reflect true prevalence rates, even among VA patients. Furthermore, studies presenting data solely from veterans that utilize the VA do not capture substance use rates among all military veterans and may have a selection bias, as not all veterans receive care through VA hospitals. 9

The most prevalent types of substance use problems among male and female veterans include heavy episodic drinking and cigarette smoking. 9 Among veterans presenting for first-time care within the VA health care system, ~11% meet criteria for a diagnosis of SUD. 3 Consistent with the general population, alcohol and drug use disorder diagnoses are more common among male than female veterans (10.5% current alcohol use disorders and 4.8% current drug use disorders among male veterans; 4.8% current alcohol use disorders and 2.4% current drug use disorders among female veterans) and are more common among non-married and younger veterans (i.e., <25 years old). 3 Demographics associated with higher rates of SUDs (e.g., young, male) in the general civilian population make up a greater proportion of the military population, which could contribute to an increased risk of certain SUDs relative to civilians. 2 , 3 , 10 A number of environmental stressors specific to military personnel have been linked to increased risk of the development of SUDs among military personnel and veterans, including deployment, combat exposure, and post-deployment civilian/reintegration challenges. 3 , 11 Onset of SUDs can also emerge secondary to other mental health problems associated with these stressors, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. 12 , 13 Additionally, interpersonal traumas (e.g., histories of child physical or sexual abuse) have been shown to mediate the risk of developing an SUD among military veterans, and some individuals join the military to escape adverse home environments. 14 , 15 Furthermore, age is an important predictor of SUD prevalence, with higher rates of SUDs associated with younger age. It is important to keep in mind that many estimates lump together all age groups despite significant variation by age. For example, a recent epidemiological study found that among male veterans, the overall prevalence of substance abuse was lower than rates of civilian substance use when all ages were examined together. 9 However, when looking at the pattern for male veterans aged 18–25 years only, the rates of substance abuse were higher in veterans compared with civilians.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders

Substance use disorders are defined as a pattern of use that results in marked distress and/or impairment, with two or more of the following symptoms over the course of a 12-month period:

- Using the substance in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than intended

- Unsuccessful attempts or persistent desire to reduce use

- Too much time spent on obtaining, using, and/or recovering from the effects of the substance

- A strong craving for the substance

- Significant interference with roles at work, school, or home

- Continued use despite recurrent social or interpersonal consequences

- Reducing or giving up important social, occupational, or recreational activities because of the substance use

- Substance use in situations in which it may be physically hazardous

- Substance use despite recurrent or persistent physical or psychological consequences

- Tolerance of the substance

- Withdrawal from the substance

Note: Adapted from American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5 ® ) . Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. 7

Specific substances

Despite strict US military policies implemented in 1986 to reduce problematic alcohol consumption, heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders are common among military personnel. 2 , 16 Policies tend to be enforced with inconsistency, and heavy alcohol consumption has long been a cultural norm used for recreation, stress relief, and socializing among military personnel. 1 , 2 Alcohol use disorders are the most prevalent form of SUD among military personnel. 3 , 17 A study examining data collected as part of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that, compared to their non-veteran counterparts, veterans were more likely to use alcohol (56.6% vs 50.8% in a 1-month period), and to report heavy use of alcohol (7.5% vs 6.5% in a 1-month period). 18 Furthermore, negative consequences from alcohol use (e.g., interpersonal, legal, and professional) are about twice as likely among binge drinkers relative to non-binge drinkers (9% vs 4%), and among heavy drinkers relative to binge drinkers (9% vs 19%). 19 High levels of combat exposure confer greater risk of problematic alcohol use; those with high levels of combat exposure are more likely to engage in heavy (26.8%) and binge (54.8%) drinking relative to other military personnel (17% and 45%, respectively). 19 These increasing rates of problematic drinking are particularly concerning, given that alcohol is the fourth leading cause of preventable death in the general US population, and that alcohol-impaired driving accounts for 31% of all driving-related fatalities. 20 , 21 Among veterans, specifically, studies demonstrate that alcohol use increases risk of interpersonal violence, poorer health, and mortality. 22 , 23

Misuse of prescription drugs, such as opioids, is on the rise among veterans. 16 Opioids, which are one of the most addicting prescription drugs available, 25 are being prescribed at increasing rates to veterans to address issues such as migraine headaches and chronic pain. 26 From 2001 to 2009, the percent of veterans in the VA health care system receiving an opioid prescription increased from 17% to 24%, and the number of prescriptions written for pain medication by military physicians has more than quadrupled. 27 , 28 From 2003 to 2007, chronic opioid use (i.e., 6 months or longer) among young veterans in the VA health care system increased from 3.0% to 4.5%. 29 On average, patients were prescribed two different opioids and had three different prescribers. 29 Of these opioid prescriptions, the majority were for oxycodone (46.9%), hydrocodone (39.5%), or codeine (6.8%). 30 Mental health diagnoses increase the likelihood of receiving an opioid prescription. Specifically, veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD (17.8%) or another mental health disorder (11.7%) were more likely to receive an opioid prescription than those without mental health diagnoses (6.5%). 31 As compared to veterans without a mental health diagnosis, those with a diagnosis of PTSD receive higher doses of opioid medications, are more likely to receive a simultaneous prescription for additional opioids or for a sedative hypnotic, and are more likely to receive an early refill. 31 Unfortunately, research suggests that those with mental health disorders are also more likely to develop opioid use disorders and to experience a number of adverse clinical outcomes (e.g., inpatient or emergency room admissions, opioid-related accidents and overdoses, and violence-related injuries). 27 , 31

Illicit drug use among veterans is roughly equivalent to their civilian counterparts (4% in the past month reporting use of any illicit drug). 18 Marijuana accounts for the vast majority of illicit drug use among veterans (3.5% report marijuana use, 1.7% report use of illicit drugs other than marijuana in a 1-month period). 18 From 2002 to 2009, cannabis use disorders increased >50% among veterans in the VA health care system. 32 Finally, data suggest that veterans are more likely to be smokers, and age-adjusted prevalence of smoking is higher among veterans than matched civilian groups (27% vs 21%). 33 Of concern for medical outcomes, more veterans than civilians with coronary heart disease are smokers. 33 Furthermore, cigarette smoking accounts for 23% of cancer-related deaths among veterans who are former smokers, and 50% of cancer-related deaths among current smokers. 34

There are a number of services and interventions available to help reduce SUDs among veterans. These include both behavioral and pharmacological treatments, and range on a spectrum from preventive screening to residential treatment programs. SUD treatment services are available to veterans connected with VA Medical Centers (VAMC) across the country. However, many veterans are not connected with a local VAMC and even when they are, access to care can be challenging. This is especially true for rural veterans who may not have a qualified provider in the area (see “Treatment challenges” section for more discussion on these issues). 35

The sections below focus on psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies typically utilized to treat SUDs among veterans. In addition to these behavioral and pharmacological interventions reviewed below, however, veterans with SUDs are encouraged to try self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA), which are free of charge and available in most cities. Participation in AA/NA can be particularly helpful as part of “aftercare” and ongoing engagement with services to help manage SUDs. Providers are encouraged to consult the recently updated VA/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guidelines for SUDs for more detailed treatment recommendations. 81

Psychotherapy

In response to high rates of alcohol use among veterans, the VA has implemented system-wide alcohol screening. The goal of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is to intervene upon risky and unhealthy drinking habits prior to progression to an alcohol use disorder, or to provide immediate treatment to those with alcohol use disorders. 24 According to the VA/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guidelines for SUDs, if treatment or further evaluation is indicated and acceptable to a patient after receiving a brief intervention, the patient should be offered a specialty referral or management in primary care. The guidelines state that if there is “an indication for and a willingness to seek treatment” a biopsychosocial assessment should be completed followed by the development and implementation of a comprehensive treatment plan. Following the collaborative development of the treatment plan, SUD-focused pharmacotherapy should be offered, if indicated, for alcohol use disorders and opioid use disorders, and all patients should be offered SUD-focused psychosocial interventions. Evidence-based psychotherapies and behavioral interventions for the management of SUDs typically involve short-term, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions. These interventions focus on the identification and modification of maladaptive thoughts and behaviors associated with increased craving, use, or relapse to substances. In addition, they may help reduce SUDs by helping incentivize individuals to achieve and maintain abstinence (e.g., contingency management therapies), or increase their ability to successfully manage stress without substances. Behavioral interventions can be delivered in person, via telehealth, and/or via the Internet. 36 – 40

Client-centered motivational interviewing approaches focus on helping increase motivation to engage in treatment and reduce or abstain from substances. 41 Walker et al conducted a randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing among 242 Army personnel. Participants received one session of motivational interviewing plus feedback or a psychoeducation control. The findings showed that the intervention resulted in significantly fewer drinks per week and lower rates of alcohol dependence diagnosis. 42

Recognizing that young veterans are often unlikely to seek care at traditional VAMCs, researchers have begun to develop alternative, novel methods of treatment engagement and delivery. For example, Pedersen et al developed a web-based, single-session intervention to reduce alcohol use among young veterans. 43 In just 2 weeks, using Facebook as a recruitment site, they recruited a sample of 784 veterans. The intervention uses personalized normative feedback (PNF) and was found to reduce number of drinks per week as well as binge drinking 1 month later. The advantages of an intervention like this one include the fact that it requires no clinician time or patient travel to a VAMC. In addition, web-based interventions reduce other barriers to care such as stigma.

Pharmacotherapy

In addition to behavioral interventions, pharmacotherapy can play an important role in the treatment and management of SUDs. 44 Medications can help reduce withdrawal symptoms which may serve as a trigger or reason for relapse, if untreated. In addition, medications can be helpful in decreasing craving, which is also a potent trigger for increased substance use or relapse following treatment. There are three medications that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for alcohol use disorders: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, and extended-release injectable naltrexone are approved by the FDA for the treatment of opioid use disorders. There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of cocaine or marijuana use disorders.

Recently, exploratory use of off-label medications for SUDs has also been the interest of much attention (e.g., oxytocin and N -acetylcysteine). 45 , 46 Investigators have also begun to explore the use of medications to treat SUDs and commonly co-morbid mental health disorders. Rarely does a veteran present with only an SUD. Oftentimes, veterans with an SUD also have co-occurring psychiatric conditions such as PTSD or depression. Recent studies have investigated several medications to help identify effective pharmacologic interventions for SUD and PTSD. For example, studies have investigated the use of prazosin, topiramate, and N -acetylcysteine with mixed results. 47 – 49

Treatment challenges

Rural locations.

According to the VA Office of Rural Health, there are ~3.4 million rural veterans (41%) that comprise the total number of veterans enrolled in VA health care system. 50 Access to care, particularly mental health services, is problematic for veterans residing in rural areas. Increased access to mental health care via telemental health (TMH) modalities may improve quality of life for veterans living in rural areas. 51 Feasibility and efficacy have been shown in the utilization of TMH in home-based settings and remote locations among veterans and civilian populations. 52 – 56 Though literature directly pertaining to the delivery of TMH services for SUDs is limited, the small body of research that specifically investigates substance use TMH treatments has demonstrated favorable results. 53 , 57 Frueh et al examined relapse prevention in veterans with alcohol use disorder using telehealth from a remote site to a local clinic. Results showed that abstinence was retained in 13 of 14 treatment completers and there was high participant satisfaction for the services delivered. 57 It is also worth noting that this study delivered TMH in a group format. Similar findings were demonstrated among veterans receiving individual home-based TMH (HBTMH) services. Veterans living in rural areas who received HBTMH reported that they prefer to receive their mental health treatment using TMH, they would recommend TMH services to other veterans, and they felt safe and less subjected to perceived stigma associated with mental illness, including SUD. 54

Clinicians have also cited advantages of TMH services for rural veterans including low no-show rates, reduced stigma felt by patients, reduced costs and travel burden, and social connection. 58 While the benefits of TMH are promising, the delivery of TMH is not without disadvantages. Limitations include issues with connectivity (e.g., slow bandwidth, problems connecting via satellite internet providers, and availability of internet connection in very rural areas), issues regarding how user savvy the clinician and patient are, and confidentiality and privacy issues, though continuous advancements made in telecommunications have lessened the severity of these issues. Specific to SUD treatment, limitations of TMH include reduced ability to identify when a patient is intoxicated (e.g., inability to smell alcohol or other substance) or conduct unplanned drug testing. 53 Telehealth can play a considerable role in increasing mental health access for veterans residing in rural communities. TMH overcomes geographic, financial, and stigma-related barriers while yielding high patient satisfaction and perceived safety to veterans who would likely not otherwise receive it. Additionally, telehealth could have a transformative impact on the VA health care system and significantly improve quality of life for veterans.

Female veterans