The World Bank Group is committed to fighting poverty in all its dimensions. We use the latest data, evidence and analysis to help countries develop policies to improve people's lives, with a focus on the poorest and most vulnerable.

Around 700 million people live on less than $2.15 per day, the extreme poverty line. Extreme poverty remains concentrated in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, fragile and conflict-affected areas, and rural areas.

After decades of progress, the pace of global poverty reduction began to slow by 2015, in tandem with subdued economic growth. The Sustainable Development Goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030 remains out of reach.

Global poverty reduction was dealt a severe blow by the COVID-19 pandemic and a series of major shocks during 2020-22, causing three years of lost progress. Low-income countries were most impacted and have yet to recover. In 2022, a total of 712 million people globally were living in extreme poverty, an increase of 23 million people compared to 2019.

We cannot reduce poverty and inequality without also addressing intertwined global challenges, including slow economic growth, fragility and conflict, and climate change.

Climate change is hindering poverty reduction and is a major threat going forward. The lives and livelihoods of poor people are the most vulnerable to climate-related risks.

Millions of households are pushed into, or trapped in, poverty by natural disasters every year. Higher temperatures are already reducing productivity in Africa and Latin America, and will further depress economic growth, especially in the world’s poorest regions.

Eradicating poverty requires tackling its many dimensions. Countries cannot adequately address poverty without also improving people’s well-being in a comprehensive way, including through more equitable access to health, education, and basic infrastructure and services, including digital.

Policymakers must intensify efforts to grow their economies in a way that creates high quality jobs and employment, while protecting the most vulnerable.

Jobs and employment are the surest way to reduce poverty and inequality. Impact is further multiplied in communities and across generations by empowering women and girls, and young people.

Last Updated: Apr 02, 2024

Closing the gaps between policy aspiration and attainment

Too often, there is a wide gap between policies as articulated and their attainment in practice—between what citizens rightfully expect, and what they experience daily. Policy aspirations can be laudable, but there is likely to be considerable variation in the extent to which they can be realized, and in which groups benefit from them. For example, at the local level, those who have the least influence in a community might not be able to access basic services. It is critical to forge implementation strategies that can rapidly and flexibly respond to close the gaps.

Enhancing learning, improving data

From information gathered in household surveys to pixels captured by satellite images, data can inform policies and spur economic activity, serving as a powerful weapon in the fight against poverty. More data is available today than ever before, yet its value is largely untapped. Data is also a double-edged sword, requiring a social contract that builds trust by protecting people against misuse and harm, and works toward equal access and representation.

Investing in preparedness and prevention

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that years of progress in reducing poverty can quickly disappear when a crisis strikes. Prevention measures often have low political payoff, with little credit given for disasters averted. Over time, populations with no lived experience of calamity can become complacent, presuming that such risks have been eliminated or can readily be addressed if they happen. COVID-19, together with climate change and enduring conflicts, reminds us of the importance of investing in preparedness and prevention measures comprehensively and proactively.

Expanding cooperation and coordination

Contributing to and maintaining public goods require extensive cooperation and coordination. This is crucial for promoting widespread learning and improving the data-driven foundations of policymaking. It is also important for forming a sense of shared solidarity during crises and ensuring that the difficult policy choices by officials are both trusted and trustworthy.

Overall, with more than 60 percent of the world’s extreme poor living in middle-income countries, we cannot focus solely on low-income countries if we want to end extreme poverty. We need to focus on the poorest people, regardless of where they live, and work with countries at all income levels to invest in their well-being and their future.

The goal to end extreme poverty works hand in hand with the World Bank Group’s goal to promote shared prosperity. Boosting shared prosperity broadly translates into improving the welfare of the least well-off in each country and includes a strong emphasis on tackling persistent inequalities that keep people in poverty from generation to generation.

Our work at the World Bank Group is based on strong country-led programs to improve living conditions—to drive growth, raise median incomes, create jobs, fully incorporate women and young people into economies, address environmental and climate challenges, and support stronger, more stable economies for everyone.

We continue to work closely with countries to help them find the best ways to improve the lives of their least advantaged citizens.

Last Updated: Oct 17, 2023

How the Pandemic Drove Increases in Poverty | Poverty & Shared Prosperity 2022

Around the bank group.

Find out what the World Bank Group's branches are doing to reduce poverty.

STAY CONNECTED

COVID-19 Dealt a Historic Blow to Poverty Reduction

The 2022 Poverty and Prosperity Report provides the first comprehensive analysis of the pandemic’s toll on poverty in developing countries and of the role of fiscal policy in protecting vulnerable groups.

Umbrella Facility for Poverty and Equity

The Umbrella Facility for Poverty and Equity (UFPE) is the first global trust fund to support the cross-cutting poverty and equity agenda.

IDA: Our Fund for the Poorest

The International Development Association (IDA) aims to reduce poverty by providing funding for programs that boost economic growth.

As the World Bank’s behavioral sciences team within the Poverty and Equity Global Practice, eMBeD uses behavioral sciences to fight global poverty and reduce inequality.

High-Frequency Monitoring Systems to Track the Impacts of COVID-19

The World Bank and partners are monitoring the crisis and the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 through a series of high-frequency phone surveys.

An Adjustment to Global Poverty Lines

The World Bank uses purchasing power parities (PPPs) to estimate global poverty. With the release of 2017 PPPs, we’ll start using in Fall 2022 new poverty lines to determine the share of the world population in poverty.

Systematic Country Diagnostics

The SCD looks at issues in countries and seeks to identify barriers and opportunities for sustainable poverty reduction.

Poverty Podcast

Join us and poverty specialists as we explore the latest data and research on poverty reduction, shared prosperity, and equity around the globe in this new World Bank Group podcast series.

Correcting Course to Accelerate Poverty Reduction

Mari Pangestu, World Bank Managing Director of Development Policy and Partnerships, speaks about how we must respond to current challenges in ways that do not further impoverish the poor today and focus on creating ...

Stepping Up the Fight Against Extreme Poverty

To avert the risk of more backsliding, policymakers must put everything they can into the effort to end extreme poverty.

Additional Resources

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Subjective Perceptions of Poverty and Objective Economic Conditions: Czechia and Slovakia a Quarter Century After the Dissolution of Czechoslovakia

- Original Research

- Published: 12 April 2019

- Volume 145 , pages 523–550, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Martina Mysíková ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6340-4753 1 ,

- Tomáš Želinský ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7198-0278 2 ,

- Thesia I. Garner 3 &

- Jiří Večerník ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0535-3118 1

864 Accesses

12 Citations

Explore all metrics

Studies into the relation between subjective perceptions of individuals and objective economic conditions have usually resulted in ambiguous empirical findings. Whilst most studies perceive subjective welfare as being operationalized by indicators of happiness or life satisfaction, we narrow the approach to an economic domain of subjective well-being—perceptions of poverty. We argue that our approach better reflects the economic dimension, as the former may include numerous non-economic domains. We use a case study of two countries—Czechia and Slovakia—which underwent early economic transition as a common state in 1989–1992, then became independent states in 1993, after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. We base our findings on three historical data sets covering a period from around the end of the communist era to the early years after the split, and recent data from EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (2005–2016). Despite initially small differences in subjective poverty levels in socialist Czechoslovakia, a considerably larger drop in economic performance during the transition period in Slovakia than in Czechia resulted in a sharp widening of the subjective poverty gap. The recent data suggests that, despite a high degree of actual economic convergence of Slovakia and Czechia, the gap in subjective perceptions of poverty is declining at a remarkably slower pace. We argue that relatively fast economic growth is not necessarily associated with a commensurate decline in subjective poverty perceptions. Our results thus support the Easterlin Paradox, although we substitute happiness by an economic dimension of subjective well-being.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

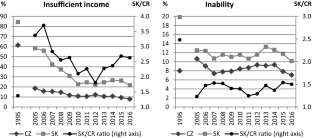

Source : SOCO 1995, EU-SILC 2005–2016. Own computations

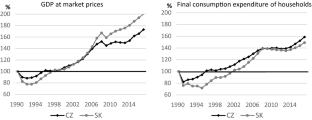

Source : The period 1990–2009 is based on the CZSO (2012) data, the period 2010–2017 is based on Eurostat data (variable nama_10_pc)

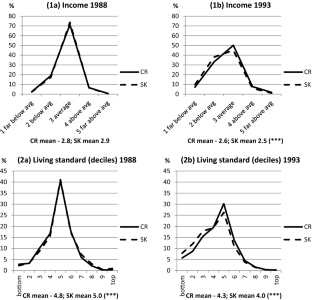

Source : Social Stratification in Eastern Europe 1993. Own computations

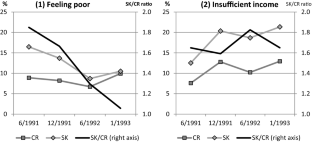

Source : EEA W3–W6. Own computations

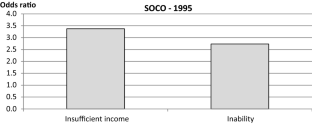

Source : Social Consequences of Transition data (1995). Own computations

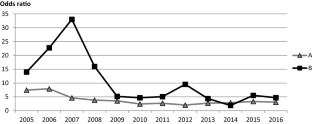

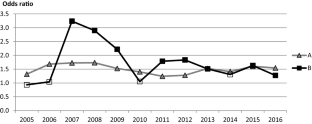

Source : EU-SILC 2005–2016. Own computations

Similar content being viewed by others

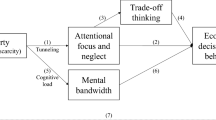

Poverty and economic decision making: a review of scarcity theory

Families’ Financial Stress & Well-Being: The Importance of the Economy and Economic Environments

Is happiness U-shaped everywhere? Age and subjective well-being in 145 countries

See Van den Bosch ( 1993 ) for a brief review of the two model-based approaches and Deleeck et al.’s ( 1992 ) approach.

Household Questionnaire, Section 17: “Concerning your family's food consumption over the past 1 month, which of the following is true?” with the following responses: “1: It was less than adequate for your family’s needs; 2: It was just adequate for your family’s needs; 3: It was more than adequate for your family’s needs; 4: Not applicable”. “Adequate” is defined as: “no more nor less than what the respondent considers to be the minimum consumption needs of the family”.

Variable YINC-7990 with the following question: “Which of the following best describes [yours/yours and your spouse's/yours and your partner's] financial condition?” and the corresponding categories: “1—very comfortable and secure; 2—able to make ends meet without much difficulty; 3—occasionally have some difficulty making ends meet; 4—tough to make ends meet but keeping your head above water; 5—in over your head”.

Even today, the subjective approach is regarded as neglected within the welfare concepts, though it remains a conceptually appealing way to define poverty (Ravallion 2014 ). Although economists have long been skeptical about subjective variables (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2001 ), their skepticism about subjective data seems, to some extent, to have been overcome today (Deaton and Stone 2013 ).

Most of the countries joined the survey in 2005.

While a targeted sociological survey on the poor population, ready to be launched by the mid-1980s, was not allowed during the communist era, poverty was opened as a research issue at the beginning of the economic transition.

The first wave did not contain the subjective variables of our interest. The second wave collected information on household disposable income using a single question (as opposed to the next waves) which makes our indicator highly incomparable. The last wave collected data on income only at intervals, which hinders construction of our indicator.

Households reporting that their actual income was absolutely sufficient to get along, consisting of 23% of Czech and 6% of Slovak households, were thus not asked the MIQ. For the rest, the reported minimum income was always higher than or equal to the actual income. Thus, if the respondents’ income was not absolutely sufficient, they were assumed to have reported a higher minimum income needed.

Note that the number of categories of the scale-evaluated questions differs across the data sets used, from four in EEA to six in EU-SILC. This raises comparability issues, which are partly offset by focusing on Slovak–Czech ratios instead on the levels of “feeling poor” or “inability” incidence across the surveys.

EU-SILC variable HY020—as actual income corresponds to annual income, one twelfth of the reported value is taken into account. EU-SILC is usually conducted in spring in Czechia and Slovakia, and the income reference period corresponds to the previous calendar year, while the subjective questions are related to the current situation. We are aware of possible inconsistencies between the current and previous year reference periods. However, the income reference period is considered to provide the best approximation of current income, as suggested by Eurostat ( 2010a ), and it is also used in this sense in official statistics.

The reason for the arbitrarily chosen threshold of 75% was that approximately the same share of the Czech population reported “insufficient income” as the share of persons designated as “at risk of poverty”—the official indicator—in 2015 (documented by Večerník and Mysíková 2016 ).

Regarding the possible limitations of the “individual” method and the arbitrarily stated poverty line, note that we cannot utilize any model-based estimation of the poverty line (SPL) because a part of the SOCO 1995 survey respondents were not asked the MIQ (almost a quarter of respondents in CZ).

Note that the scale differs in SOCO and in EU-SILC.

The categories are derived based on the population size and density of the municipality. The definition of the degree of urbanization has changed slightly over time in EU-SILC definitions (compare Eurostat 2010b , 2016 ).

The regression results mostly show a statistically insignificant difference between those paying a mortgage and those paying rent; however, if the coefficient is statistically significant, those paying a mortgage are less likely to feel poor.

Our definition of the work intensity indicator is different from the one applied by Eurostat in official statistics (see Ward and Ozdemir 2013 ). Here we simply add up the number of months worked during the year by all household members aged 16+ and divide it by 12 times the number of household members aged 16+. Our purpose is to control for the share of household members who actively contribute to the household budget, while the Eurostat definition is aimed to identify socially excluded persons.

The NUTS2 level includes 8 Czech and 4 Slovak regions.

Employment rate for population aged 15–64, Eurostat database (variable lfst_r_lfe2emprt).

Eurostat database (variable nama_10r_2gdp).

Data on expenditures stem from Household Budget Surveys, provided by the Czech and Slovak Statistical Offices.

For the sake of space, we do not provide full results of the logistic regressions models or comment on them, but they are available upon request.

As with the official statistics, all computations based on EU-SILC are weighted by the individual weights provided in the datasets.

Indeed, the variance of the two indicators of subjective poverty defined above differs, especially in Slovakia: while the variance of the insufficient income indicator ranges from 0.07 to 0.14 in CZ and from 0.16 to 0.25 in SK throughout the period 2005–2016, the respective figures are 0.06–0.09 and 0.09–0.11 for the inability indicator.

Slovakia suffered from weaker economic performance than Czechia for decades, followed by a rapid convergence with Czechia through the 1980s. Slovakia attained 61% of the Czech GDP in 1948, whereas its GDP reached 88% of that of Czechia at the end of the communist era in 1989 (see, e.g., Vintrová 2008 , 2009 for further details).

The consistency of the data on actual household disposable income over survey waves is rather low as the income questions varied in each wave. The reason was to improve the validity of the variable by dividing one original summary question into several asking about individual sources of income. However, as a consequence, the indicator of insufficient income is unstable over time.

The SK dummy shows a relative outcome, meaning that the perceived subjective poverty might have increased in Slovakia, decreased in Czechia, or any combination that might have led to the wider SK–CZ gap in Model B compared to Model A. In order to shed more light on what was happening in each country, we ran a model with pooled data for all years and included year dummies together with their interaction terms with the SK dummy. The results showed that both the Czechs and Slovaks are more likely to perceive their household income as insufficient once the economic conditions are controlled for. However, this difference is substantially greater in Slovakia than in Czechia. Further, this difference is decreasing over time in both countries. Finally, the results of the pooled model with economic controls (Model B) indicate that, in Czechia, the likelihood an individual will perceive his/her income as insufficient (with the last year as a reference point) was decreasing gradually (from relatively low likelihood at the beginning). In Slovakia, the relatively high likelihood at the beginning was sharply decreasing up to 2010.

The 2007 jump appears when the regional GDP is added to the regressors. Without the regional GDP, the odds ratio for SK accounts for 10.4 in 2007, and the peak occurs in 2006 (19.5), similarly to Model A.

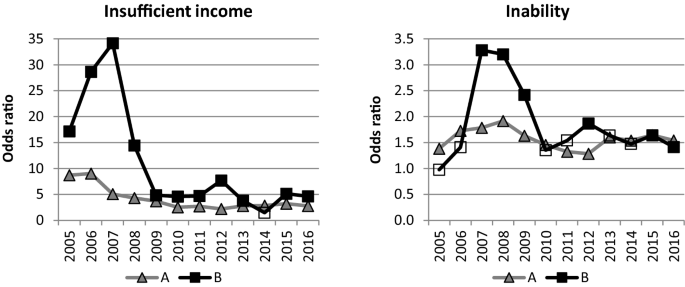

Finally, we conclude that the fact that the subjective questions are responded to by one household member and attributed to all other household members has only a negligible impact on the results (compare Fig. 6 and the left panel of Fig. 12 for insufficient income, and Fig. 7 and the right panel of Fig. 12 for inability). Apart from a loss in statistical significance in some years, the qualitative results and trends remain the same.

Respondents state the income variables in their national currency, i.e. Slovak crown till 2008 and Euro since 2009 in Slovakia, and Czech crown in the Czech Republic for the whole period. Eurostat converts the income variables into Euros (and provides the exchange rate applied each year). The Czech Republic has not adopted the Euro, and the exchange rate moved from 32 CZK/EUR in 2005 to 25 CZK/EUR around 2012 and to 27 CZK/EUR in 2016. In Slovakia, the exchange rate dropped from 39 SKK/EUR to 34 SKK/EUR between 2005 and 2007, and the Slovak crown was replaced by the Euro at the irrevocably fixed exchange rate of 1 EUR = 30.1260 SKK on 1 January 2009.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2001). Do people mean what they say? Implications for subjective survey data. The American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings), 91 (2), 67–72.

Article Google Scholar

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88 (7–8), 1359–1386.

Bonke, J., & Browning, M. (2009). The distribution of financial well-being and income within the household. Review of Economics of the Household, 7 (1), 31–42.

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being . Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Google Scholar

Clark, A. E., D’Ambrosio, C., & Ghislandi, S. (2015). Poverty profiles and well-being: Panel evidence from Germany. In T. I. Garner, K. S. Short (Eds.), Measurement of poverty, deprivation, and economic mobility (Research on Economic Inequality, Vol. 23, pp. 1–22). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Cracolici, M. F., Giambona, F., & Cuffaro, M. (2011). The determinants of subjective economic wellbeing: An analysis of Italian-Silc data. Applied Research on Quality of Life, 7 (1), 17–47.

Cracolici, M. F., Giambona, F., & Cuffaro, M. (2014). Family structure and subjective economic well-being: Some new evidence. Social Indicators Research, 118 (1), 433–456.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: An attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38 (3), 303–328.

Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2013). Two happiness puzzles. The American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings), 103 (3), 591–597.

Decancq, K., Goedemé, T., Van den Bosch, K., & Vanhille, J. (2013). The evolution of poverty in the European Union: Concepts, measurement and data . ImPRovE Methodological Paper No. 13/01. Antwerp: Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy—University of Antwerp.

Deleeck, H., Van den Bosch, K., & De Lathouwer, L. (1992). Poverty and the adequacy of social security in the EC: A comparative analysis . Aldershot: Avebury.

Di Tella, R., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & MacCulloch, R. (2010). Happiness adaptation to income and to status in an individual panel. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76 (3), 834–852.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2001). Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. The American Economic Review, 91 (1), 335–341.

Diener, E., & Suh, E. M. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40 (1–2), 189–216.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125 (2), 276–302.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (2017). Paradox lost? Review of Behavioral Economics, 4 (4), 311–339.

Easterlin, R. A., et al. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107 (52), 22463–22468.

Easterlin, R. A., & Plagnol, A. C. (2008). Life satisfaction and economic conditions in East and West Germany pre- and post-unification. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68 (3–4), 433–444.

European Commission. (2005). Standard Eurobarometer 62/Autumn 2004: Public opinion in the European Union . Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2017). Standard Eurobarometer 86/Autumn 2016: Public opinion in the European Union . Brussels: European Commission.

Eurostat. (2010a). Algorithms to compute social inclusion indicators based on EU-SILC and adopted under the open method of coordination (OMC). Doc. LC-ILC/39/09/EN-rev.1 1.

Eurostat. (2010b). Description of target variables: Cross-sectional and longitudinal. 2008 Operation (Version January 2010).

Eurostat. (2016). Methodological guidelines and description of EU-SILC target variables. 2015 Operation (Version August 2016).

Fahey, T., & Smyth, E. (2004). Do subjective indicators measure welfare? Evidence from 33 European societies. European Societies, 6 (1), 5–27.

Förster, M., Tarcali, G., & Till, M. (2004). Income and non-income poverty in Europe: What is the minimum acceptable standard in an enlarged European Union? . Vienna: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40 (2), 402–435.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Investigating the patterns and determinants of life satisfaction in Germany following reunification. The Journal of Human Resources, 39 (3), 649–674.

Garner, T. I., Shipp, S., Steiger, D. M., & Manieri, T. (1998). Subjective assessments of economic well-being: Cognitive research at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Focus: Revising the poverty measure, 19 (2), 43–46.

Goedhart, T., Halberstadr, V., Kapteyn, A., & van Praag, B. M. S. (1977). The poverty line: Concept and measurement. The Journal of Human Resources, 12 (4), 503–520.

Goedhart, T., van Praag, B. M. S., & Kapteyn, A. J. (1980). The poverty line: A pilot survey in Europe. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 62 (3), 461–465.

Goerke, L., & Pannenberg, M. (2015). Direct evidence for income comparisons and subjective well-being across reference groups. Economics Letters, 137 (C), 95–101.

Hagerty, M. R., et al. (2001). Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Social Indicators Research, 55 (1), 1–96.

Helson, H. (1947). Adaptation-level as frame of reference for prediction of psychophysical data. The American Journal of Psychology, 60 (1), 1–29.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47 (2), 263–292.

Kapteyn, A., Kooreman, P., & Willemse, R. (1988). Some methodological issues in the implementation of subjective poverty definitions. The Journal of Human Resources, 23 (2), 222–242.

Kenny, C. (1999). Does growth cause happiness, or does happiness cause growth? Kyklos, 52 (1), 3–25.

Lane, R. E. (1991). The market experience . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22 (140), 5–55.

Machonin, P. (1994). K sociologické komparaci české a slovenské společnosti (Towards sociological comparison of Czech and Slovak society). Sociológia, 26 (4), 333–345.

Noll, H.-H., & Weick, S. (2010). Subjective well-being in Germany: Evolutions, determinants and policy implications. In B. Greve (Ed.), Happiness and social policy in Europe (pp. 70–90). Cheltenham: Edward Egar.

Ogburn, W. F. (1946). A study of rural society . Cambridge: Riverside Press.

Petrunyk, I., & Pfeifer, C. (2016). Life satisfaction in Germany after reunification: Additional insights on the pattern of convergence. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik (Journal of Economics and Statistics), 236 (2), 217–239.

Pradhan, M., & Ravallion, M. (2000). Measuring poverty using qualitative perceptions of consumption adequacy. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 82 (3), 462–471.

Ravallion, M. (2014). Poor, or just feeling poor? On using subjective data in measuring poverty. In A. Clark & C. Senik (Eds.), Happiness and economic growth: Lessons from developing countries (pp. 140–174). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ravallion, M. (2016). The economics of poverty: History, measurement, and policy . New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01-9021-276-6.

Santarelli, E. (2013). A review of the literature on subjective poverty in Europe: A focus on data sources. Sapienza University of Rome, Working paper no. 118.

Steger, M. F., & Samman, E. (2012). Assessing meaning in life on an international scale: Psychometric evidence for the meaning in life questionnaire-short form among Chilean households. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2 (3), 182–195.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Paris: Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress . https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/118025/118123/Fitoussi+Commission+report . Last accessed November 2018.

Stutzer, A. (2004). The role of income aspirations in individual happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 54 (1), 89–109.

Thijssen, J., & Wildeboer Schut, J. M. (2005). Armoede in hoofdlijnen. In C. Vrooman, H.-J. Dirven, A. Soede, & R. Trimp (Eds.), Armoedemonitor (pp. 16–52). Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Van den Bosch, K. (1993). Poverty measures in comparative research. In J. Berghman (Ed.), The European face of social security: Essays in honour of Herman Deleeck (pp. 3–23). Aldershot: Avebury.

van Praag, B. M. S., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified. A satisfaction calculus approach . New York: Oxford University Press.

van Praag, B. M. S., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2008). A multidimensional approach to subjective poverty. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), Quantitative approaches to multidimensional poverty measurement (pp. 135–154). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

van Praag, B. M. S., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51 (1), 29–49.

Večerník, J., & Mysíková, M. (2016). Poverty in the Czech Republic: A critical look at EU indicators . Prague: SOÚ AV ČR. ISBN 978-80-7330-290-0.

Veenhoven, R. (2002). Why social policy needs subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 58 (1–3), 33–46.

Vintrová, R. (2008). Česká a slovenská ekonomika 15 let po rozdělení (The Czech and Slovak economy 15 years after the split). Politická ekonomie, 56 (4), 449–466.

Vintrová, R. (2009). Lessons from the Czech and Slovak economies split. Prague Economic Papers, 18 (1), 3–25.

Vogel, J. (2002). Strategies and traditions in Swedish social reporting: A 30-year experience. Social Indicators Research, 58 (1–3), 89–112.

Vrooman, C. J. (2009). Rules of relief; institutions of social security, and their impact . The Hague: The Netherlands Institute of Social Research. ISBN 978-90-3770-218-7.

Vrooman, C., & Hoff, S. (Eds.). (2004). The poor side of the Netherlands; results from the Dutch ‘Poverty monitor’, 1997–2003 . The Hague: Social and Cultural Planning Office.

Ward, T., & Ozdemir, E. (2013). Measuring low work intensity—An analysis of the indicator . ImPRovE Methodological Paper No. 13/09. Antwerp: Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy—University of Antwerp.

Wong, C. K., Wong, K. Y., & Mok, B. H. (2006). Subjective well-being, societal condition and social policy—The case study of a rich Chinese society. Social Indicators Research, 78 (3), 405–428.

Želinský, T. (2014). Poverty and deprivation in Slovakia: Methodological aspects and empirics . Košice: Equilibria. ISBN 978-80-8143-134-0.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Regional Development Fund—Project “CSDA Research” (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_013/0001796) and by the Slovak Scientific Grant Agency (VEGA 2/0002/19). Tomáš Želinský further acknowledges support for visiting the Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences financed within the Protocol on cooperation in the field of education, youth and sports between the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sports of the Slovak Republic and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. The EU-SILC datasets were made available on the basis of Contract No. 265/14 between the European Commission, Eurostat, and the Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences. Thanks for additional data information go to the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic and the Czech Statistical Office. The authors especially wish to thank Andrew Clark, who provided valuable comments and ideas as a discussant of this paper at the IARIW 2018 General Conference. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments which substantially contributed to the overall readability of the final version of this paper. Responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors.

EU-SILC datasets versions

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Jilská 1, 110 00, Prague 1, Czech Republic

Martina Mysíková & Jiří Večerník

Faculty of Economics, Technical University of Košice, Němcovej 32, 040 01, Košice, Slovakia

Tomáš Želinský

Division of Price and Index Number Research, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2 Mass. Ave. NE, Washington, DC, USA

Thesia I. Garner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Martina Mysíková .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

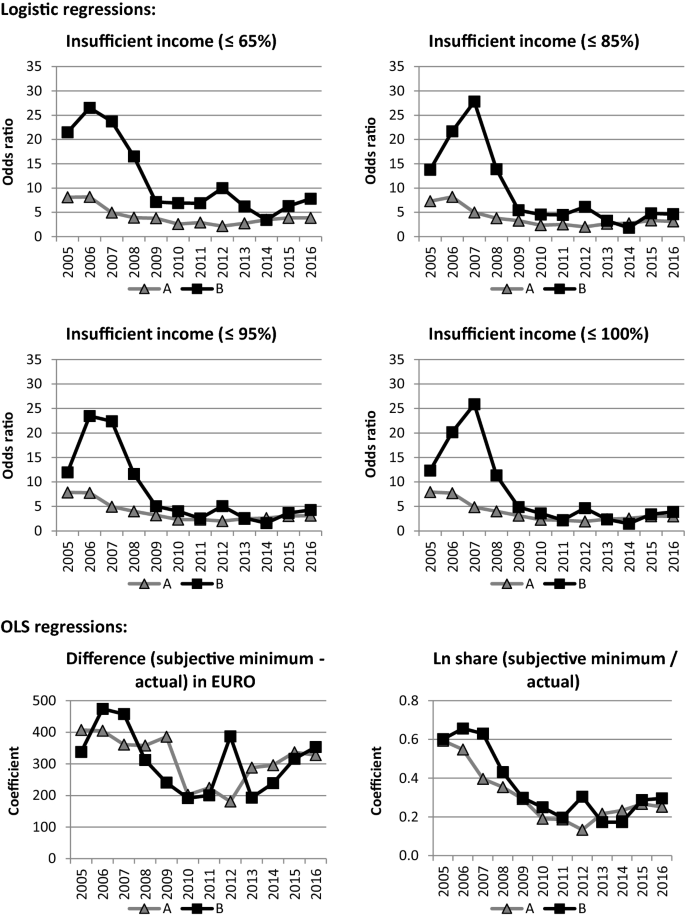

Regression analysis of different definitions of insufficient income indicator as the dependent variable, SK dummy (odds ratio/coefficients), 2005–2016. Notes : Respondents aged 16+. All coefficients of the SK dummy are statistically significant at the 1% level. Model A controls for demographic characteristics. Model B additionally controls for socioeconomic and regional macroeconomic characteristics (see Sect. 3 on the list of control variables). GDP is missing in 2016. (Robust standard errors were used.)

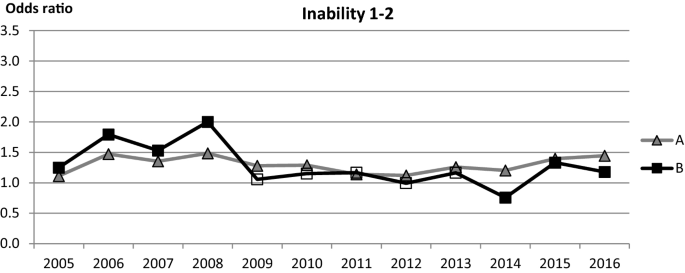

Logistic regression of inability (1–2)—SK dummy (odds ratio), 2005–2016. Notes : Inability indicator (1–2): the dependent variable equals 1 if the answer was “great difficulty” or “difficulty”. Respondents aged 16+. Coefficients in Model A are statistically significant at the 1% level; in Model B, empty marks represent coefficients which are not statistically significant at the 10% level, other coefficients of the SK dummy are statistically significant at least at the 10% level. Model A controls for demographic characteristics. Model B additionally controls for socioeconomic and reginal macroeconomic characteristics (see Sect. 3 on the list of control variables). GDP is missing in 2016. (Robust standard errors were used.)

Logistic regression of insufficient income and inability—SK dummy (odds ratio), subsample of respondents answering household questionnaire, 2005–2016. Notes : Only respondents aged 16+ responsible for answering household questionnaire are included. Empty marks represent coefficients which are not statistically significant at the 10% level; all other coefficients of the SK dummy are statistically significant at the 5% level. Model A controls for demographic characteristics. Model B additionally controls for socioeconomic and reginal macroeconomic characteristics (see Sect. 3 on the list of control variables). GDP is missing in 2016. (Robust standard errors were used.)

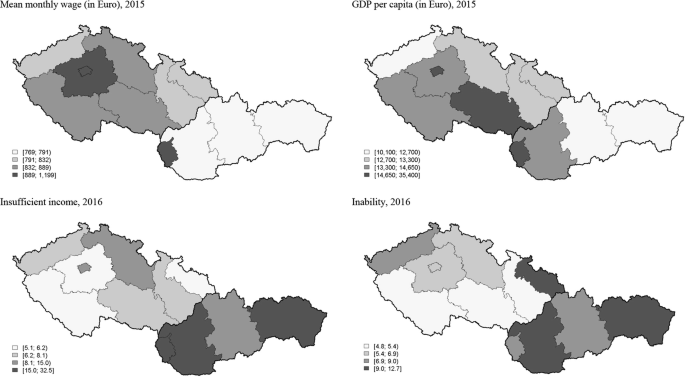

Source : EU-SILC 2015 and 2016 (own computations); Eurostat database for GDP (current prices, Euro per capita—variable nama_10_pc)

Spatial distribution of mean wage, GDP, insufficient income and inability (NUTS2 regions), 2015–2016. Notes : Maps were created using (c) EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries “NUTS 2013” shapefiles.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mysíková, M., Želinský, T., Garner, T.I. et al. Subjective Perceptions of Poverty and Objective Economic Conditions: Czechia and Slovakia a Quarter Century After the Dissolution of Czechoslovakia. Soc Indic Res 145 , 523–550 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02102-2

Download citation

Accepted : 11 March 2019

Published : 12 April 2019

Issue Date : 01 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02102-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Subjective well-being

- Subjective poverty

- Easterlin Paradox

- East-Central Europe

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere

Eradicating extreme poverty for all people everywhere by 2030 is a pivotal goal of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Extreme poverty, defined as surviving on less than $2.15 per person per day at 2017 purchasing power parity, has witnessed remarkable declines over recent decades.

However, the emergence of COVID-19 marked a turning point, reversing these gains as the number of individuals living in extreme poverty increased for the first time in a generation by almost 90 million over previous predictions.

Even prior to the pandemic, the momentum of poverty reduction was slowing down. By the end of 2022, nowcasting suggested that 8.4 per cent of the world’s population, or as many as 670 million people, could still be living in extreme poverty. This setback effectively erased approximately three years of progress in poverty alleviation.

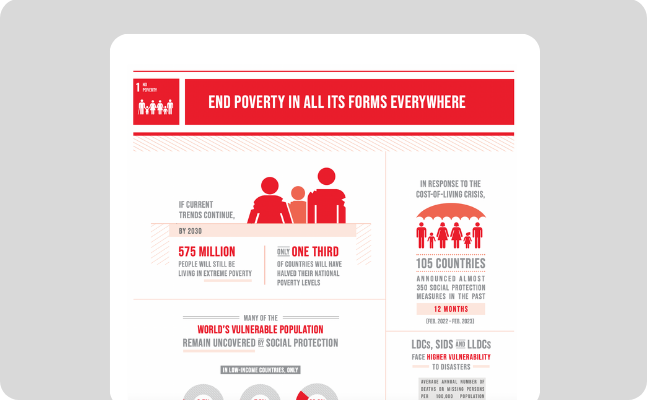

If current patterns persist, an estimated 7% of the global population – around 575 million people – could still find themselves trapped in extreme poverty by 2030, with a significant concentration in sub-Saharan Africa.

A shocking revelation is the resurgence of hunger levels to those last observed in 2005. Equally concerning is the persistent increase in food prices across a larger number of countries compared to the period from 2015 to 2019. This dual challenge of poverty and food security poses a critical global concern.

Why is there so much poverty

Poverty has many dimensions, but its causes include unemployment, social exclusion, and high vulnerability of certain populations to disasters, diseases and other phenomena which prevent them from being productive.

Why should I care about other people’s economic situation?

There are many reasons, but in short, because as human beings, our well- being is linked to each other. Growing inequality is detrimental to economic growth and undermines social cohesion, increas- ing political and social tensions and, in some circumstances, driving instability and conflicts.

Why is social protection so important?

Strong social protection systems are essential for mitigating the effects and preventing many people from falling into poverty. The COVID-19 pandemic had both immediate and long-term economic consequences for people across the globe – and despite the expansion of social protection during the COVID-19 crisis, 55 per cent of the world’s population – about 4 billion people – are entirely unprotected.

In response to the cost-of-living crisis, 105 countries and territories announced almost 350 social protection measures between February 2022 and February 2023. Yet 80 per cent of these were short-term in nature, and to achieve the Goals, countries will need to implement nationally appropriate universal and sustainble social protection systems for all.

What can I do about it?

Your active engagement in policymaking can make a difference in addressing poverty. It ensures that your rights are promoted and that your voice is heard, that inter-generational knowledge is shared, and that innovation and critical thinking are encouraged at all ages to support transformational change in people’s lives and communities.

Governments can help create an enabling environment to generate pro- productive employment and job opportunities for the poor and the marginalized.

The private sector has a major role to play in determining whether the growth it creates is inclusive and contributes to poverty reduction. It can promote economic opportunities for the poor.

The contribution of science to end poverty has been significant. For example, it has enabled access to safe drinking water, reduced deaths caused by water-borne diseases, and improved hygiene to reduce health risks related to unsafe drinking water and lack of sanitation.

Facts and Figures

Goal 1 targets.

- If current trends continue, 575 million people will still be living in extreme poverty and only one-third of countries will have halved their national poverty levels by 2030.

- Despite the expansion of social protection during the COVID-19 crisis, over 4 billion people remain entirely unprotected. Many of the world’s vulnerable population groups, including the young and the elderly, remain uncovered by statutory social protection programmes.

- The share of government spending on essential services, such as education, health and social protection, is significantly higher in advanced economies than in emerging and developing economies.

- A surge in action and investment to enhance economic opportunities, improve education and extend social protection to all, particularly the most excluded, is crucial to delivering on the central commitment to end poverty and leave no one behind.

- The global poverty headcount ratio at $2.15 is revised slightly up by 0.1 percentage points to 8.5 percent, resulting in a revision in the number of poor people from 648 to 659 million. ( World Bank)

Source: The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023

1.1 By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than $2.15 a day

1.2 By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

1.3 Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable

1.4 By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance

1.5 By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters

1.A Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programmes and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions

1.B Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions

- United Nations Development Programme

- UN Children’s Fund

- International Monetary Fund

- UN Global Compact

- UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction

Fast Facts: No Poverty

Infographic: No Poverty

Related News

UN forum in Bahrain: Innovation as the key to solving global problems

dpicampaigns 2024-05-15T16:48:52-04:00 14 May 2024 |

A major UN forum opened on Tuesday in Bahrain. Its mission: to empower entrepreneurial leaders who can build a brighter future and achieve sustainable development for all.

Media Advisory | UN to launch updated outlook for global economy

Yinuo 2024-05-13T11:31:07-04:00 13 May 2024 |

UN to launch updated outlook for global economy PRESS BRIEFING Thursday, 16 May 2024, 12:30 pm (EDT) Live on UN WebTV The report is under embargo until 16 May 2024, 12:30 pm EDT The [...]

‘Untold harm to nature’ from wildlife trafficking, warns UN crime agency

dpicampaigns 2024-05-13T08:00:00-04:00 13 May 2024 |

Despite two decades of worldwide efforts, more than 4,000 precious wildlife species still fall prey to trafficking every year, a new report by the UN crime and drugs prevention office, UNODC, showed on Monday. Read [...]

Related Videos

dpicampaigns 2024-05-15T16:48:52-04:00 14 May 2024 | News |

Yinuo 2024-05-13T11:31:07-04:00 13 May 2024 | Press material |

dpicampaigns 2024-05-13T08:00:00-04:00 13 May 2024 | Goal 13: Climate Action , News |

Japan: Safeguarding a mother tongue and mother nature

dpicampaigns 2024-05-12T08:00:00-04:00 12 May 2024 | News |

When asked what might be the most beautiful word in Shimamuni, the Indigenous language variety spoken on Okinoerabu Island in Kagoshima prefecture of southwestern Japan, Nami Sao pondered for a moment before replying “mihedirodoo.” Her husband, Tomoyuki Sao, is quick to elaborate that its utterance is always enlivened with a smile and tends to make fellow Shimamuni speakers noticeably more pleased than arigatou, the standard Japanese equivalent for saying thank you.

Economic Stability

About This Literature Summary

This summary of the literature on Poverty as a social determinant of health is a narrowly defined examination that is not intended to be exhaustive and may not address all dimensions of the issue. Please note: The terminology used in each summary is consistent with the respective references. For additional information on cross-cutting topics, please see the Discrimination , Employment , Housing Instability , and Incarceration literature summaries.

Related Objectives (4)

Here's a snapshot of the objectives related to topics covered in this literature summary. Browse all objectives .

- Reduce the proportion of people living in poverty — SDOH‑01

- Increase employment in working-age people — SDOH‑02

- Increase the proportion of children living with at least 1 parent who works full time — SDOH‑03

- Reduce the proportion of families that spend more than 30 percent of income on housing — SDOH‑04

Related Evidence-Based Resources (3)

Here's a snapshot of the evidence-based resources related to topics covered in this literature summary. Browse all evidence-based resources .

- Social Determinants of Health: Tenant-Based Housing Voucher Programs

- New Perspectives on Creating Jobs: Final Impacts of the Next Generation of Subsidized Employment Programs

- Strengthening TANF Outcomes By Developing Two-Generation Approaches To Build Economic Security

Literature Summary

The United States measures poverty based on how an individual’s or family’s income compares to a set federal threshold. 1 For example, in the 2021 definition, people are considered impoverished if their individual income is below $12,880 or their household income is below $26,500 for a family of 4. 2 After 5 consecutive years in decline, the U.S. poverty rate increased to 11.4 percent in 2020, or a total of 37.2 million people. 3

Poverty often occurs in concentrated areas and endures for long periods of time. 1 Some communities, such as certain racial and ethnic groups, people living in rural areas, and people with disabilities, have a higher risk of poverty for a myriad of factors that extend beyond individual control. 1 , 4 – 8 For example, institutional racism and discrimination contribute to unequal social and economic opportunities. 4 Residents of impoverished communities often have reduced access to resources that are needed to support a healthy quality of life, such as stable housing , healthy foods , and safe neighborhoods. 1 , 4 , 9 Poverty can also limit access to educational and employment opportunities, which further contributes to income inequality and perpetuates cyclical effects of poverty. 1

Unmet social needs, environmental factors, and barriers to accessing health care contribute to worse health outcomes for people with lower incomes. 10 , 11 For example, people with limited finances may have more difficulty obtaining health insurance or paying for expensive procedures and medications. 12 In addition, neighborhood factors, such as limited access to healthy foods and higher instances of violence , can affect health by influencing health behaviors and stress. 12

Across the lifespan, residents of impoverished communities are at increased risk for mental illness, chronic disease, higher mortality, and lower life expectancy. 9 , 13 – 17 Children make up the largest age group of those experiencing poverty. 18 , 19 Childhood poverty is associated with developmental delays, toxic stress, chronic illness, and nutritional deficits. 20 – 24 Individuals who experience childhood poverty are more likely to experience poverty into adulthood, which contributes to generational cycles of poverty. 25 In addition to lasting effects of childhood poverty, adults living in poverty are at a higher risk of adverse health effects from obesity, smoking, substance use, and chronic stress. 12 Finally, older adults with lower incomes experience higher rates of disability and mortality. 6 One study found that men and women in the top 1 percent of income were expected to live 14.6 and 10.1 years longer respectively than men and women in the bottom 1 percent. 26

Poverty is a multifaceted issue that will require multipronged approaches to address. Strategies that improve the economic mobility of families may help to alleviate the negative effects of poverty. 27 – 29 For example, tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit alleviate financial burdens for families with lower and middle incomes by reducing the amount of taxes owed. 30 In addition, federal social assistance programs are designed to provide safety net services and specifically benefit individuals and families with lower incomes. 31 Two of the nation’s largest social assistance programs are Medicaid, which provides health coverage, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides food assistance. Medicaid and SNAP serve millions of people each year and have been associated with reductions in poverty along with overall health benefits. 32 , 33 In order to reduce socioeconomic inequality, it may also be important to address factors that are associated with the health status of poor communities. 27 Additional research and interventions are needed to address the effects of poverty on health outcomes and disparities.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (n.d.) Rural poverty & well-being . Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2021, February 1). 2021 Poverty guidelines . https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references/2021-poverty-guidelines

Shrider, E. A., Kollar, M., Chen, F., & Semega, J. (2021, September 14). Income and poverty in the United States: 2020 . U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

Williams, D. R., Mohammed, S. A., Leavell, J., & Collins, C. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1186 (1), 69–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x

Kaiser Family Foundation. (n.d.). Poverty rate by race/ethnicity . https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/

Minkler, M., Fuller-Thomson, E., & Guralnik, J. M. (2006). Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 355 (7), 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa044316

Brucker, D. L., Mitra, S., Chaitoo, N., & Mauro, J. (2015). More likely to be poor whatever the measure: Working-age persons with disabilities in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 96 (1), 273–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12098

Rank, M. R., & Hirschl, T. A. (2015). The likelihood of experiencing relative poverty over the life course. PLoS ONE, 10 (7), e0133513. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133513

Singh, G. K., & Siahpush, M. (2006). Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980–2000. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35 (4), 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl083

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Tehranifar, P. (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl 1) , S28–S40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383498

Thompson, T., McQueen, A., Croston, M., Luke, A., Caito, N., Quinn, K., Funaro, J., & Kreuter, M. W. (2019). Social needs and health-related outcomes among Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 46 (3), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198118822724

Khullar, D., & Chokshi, D. A. (2018). Health, income, & poverty: Where we are & what could help . Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935

Braveman, P. A., Cubbin, C., Egerter, S., Williams, D. R., & Pamuk, E. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health, 100 (Suppl 1), S186–S196. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082

Belle, D., & Doucet, J. (2003). Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27 (2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00090

Caughy, M. O., O’Campo, P. J., & Muntaner, C. (2003). When being alone might be better: Neighborhood poverty, social capital, and child mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 57 (2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00342-8

Ward-Smith, P. (2007). The effects of poverty on urologic health. Urologic Nursing, 27 (5), 445–446.

Mode, N. A., Evans, M. K., & Zonderman, A. B. (2016). Race, neighborhood economic status, income inequality and mortality. PLoS ONE, 11 (5), e0154535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154535

Kaiser Family Foundation. (n.d.). Poverty rate by age . https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-age/

Cellini, S. R., McKernan, S. M., & Ratcliffe, C. (2008). The dynamics of poverty in the United States: A review of data, methods, and findings. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27 (3), 577–605. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.20337

Eamon, M. K. (2001). The effects of poverty on children’s socioemotional development: An ecological systems analysis. Social Work, 46 (3), 256–266.

Evans, G. W., & Kim, P. (2013). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Development Perspectives, 7 (1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12013

Shaw, D. S., & Shelleby, E. C. (2014). Early-starting conduct problems: Intersection of conduct problems and poverty. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10 (1), 503–528. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153650

Justice, L. M., Jiang, H., Purtell, K. M., Schmeer, K., Boone, K., Bates, R., & Salsberry, P. J. (2019). Conditions of poverty, parent-child interactions, and toddlers’ early language skills in low-income families. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23 (7), 971–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-02726-9

Council on Community Pediatrics, Gitterman, B. A., Flanagan, P. J., Cotton, W. H., Dilley, K. J., Duffee, J. H., Green, A. E., Keane, V. A., Krugman, S. D., Linton, J. M., McKelvey, C. D., & Nelson, J. L. (2016). Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics, 137 (4), e20160339. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0339

Wagmiller Jr, R. L., & Adelman, R. M. (2009). Childhood and intergenerational poverty: The long-term consequences of growing up poor . National Center for Children in Poverty. https://www.nccp.org/publication/childhood-and-intergenerational-poverty/

Chetty, R., Stepner, M., Abraham, S., Lin, S., Scuderi, B., Turner, N., Bergeron, A., & Cutler, D. (2016). The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA, 315 (16), 1750–1766. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.4226

Yoshikawa, H., Aber, J. L., & Beardslee, W. R. (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. The American Psychologist, 67 (4), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028015

Riccio, J. A., Dechausay, N., Greenberg, D. M., Miller, C., Rucks, Z., & Verma, N. (2010). Toward reduced poverty across generations: Early findings from New York City’s conditional cash transfer program . MDRC.

Love, J. M., Kisker, E. E., Ross, C. M., Schochet, P. Z., Brooks-Gunn, J., Paulsell, D., Boller, K., Constantine, J., Vogel, C., Fuligni, A. S., & Brady-Smith, C. (2002). Making a difference in the lives of infants and toddlers and their families: The impacts of early Head Start. Volumes I–III: Final technical report and appendixes and local contributions to understanding the programs and their impacts . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families.

Maag, E., & Airi, N. (2020). Moving forward with the earned income tax credit and child tax credit: Analysis of proposals to expand refundable tax credits. National Tax Journal, 73 (4), 1163–1186. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2020.4.11

Blank, R. M. (2002). Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 40 (4), 1105–1166.

Currie, J., & Chorniy, A. (2021). Medicaid and Child Health Insurance Program improve child health and reduce poverty but face threats. Academic Pediatrics, 21 (8), S146–S153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2021.01.009

Keith-Jennings, B., Llobrera, J., & Dean, S. (2019). Links of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program with food insecurity, poverty, and health: Evidence and potential. American Journal of Public Health, 109 (12), 1636–1640. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305325

Back to top

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Transforming Poverty Alleviation Policies

Adapting the regional innovation architecture approach.

Poverty, defined as the inability of individuals to fulfill their basic needs, poses a significant challenge to achieving community welfare in many regions. Addressing this challenge requires a holistic and integrated approach that considers Indonesian society's diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts. Adapting innovative architecture is crucial in confronting Indonesia's various cultural and socio-economic landscapes. This approach provides new alternatives for regional development strategies and opens up new opportunities for transforming and adapting innovation to tackle poverty holistically and sustainably. This research aims to restructure innovation architecture and examine its potential to transform regions in poverty alleviation efforts. The study employs a qualitative research method with a literature review analysis. It explores novel approaches for developing a solution-oriented and applicable analysis and recommendations for communities. Additionally, the research analyzes several regions that have successfully implemented regional innovation and reduced local poverty levels. Data is collected through a literature search strongly relevant to the research objectives. The findings indicate that innovation architecture can drive regional transformation in poverty alleviation through 1) Enhancing collaboration and synergy among stakeholders, 2) Creating a conducive innovation ecosystem, and 3) Developing contextual and sustainable innovative solutions. These findings demonstrate the substantial potential of innovation architecture in transforming regions to achieve poverty alleviation. This aligns with existing theories emphasizing stakeholder collaboration and synergy as key factors in creating effective, innovative solutions. Innovation architecture can serve as an effective tool in transforming regions towards poverty alleviation. Proper and sustainable implementation of innovation architecture can assist regions in crafting contextual, innovative solutions and enhancing community welfare .

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2024 Author(s)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Make a Submission

Manuscript Template

Accreditation Certificate

Download Certificate

Journal Policies

- Focus and Scope

- Section Policies

- Peer Review Process

- Publication Frequency

- Open Access Statement

- Article Processing Charges

- Plagiarism Check

- References Management

- Author Guidelines

- Copyright Notice and Licensing

- Publication Ethics and Malpractice Statement

- Crossmark Policy Page

Abstracting & Indexing

See complete lists

Citation Analysis

Collaboration

Domestic Policy Strategy Agency Ministry of Home Affairs

Jalan Kramat Raya Nomor 132 Jakarta Pusat DKI Jakarta - 10430

p-ISSN: 2085-4323 e-ISSN Elektronik: 2503-3360

DOI: 10.21787/jbp

Jurnal Bina Praja has been accredited by the Ministry of Research and Technology/Head of the National Research and Innovation Agency of the Republic of Indonesia in SINTA 2 based on Decree Number 200/M/KPT/2020

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 14 May 2024

2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years

- Jan Esper ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3919-014X 1 , 2 ,

- Max Torbenson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2720-2238 1 &

- Ulf Büntgen 2 , 3 , 4

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1528 Altmetric

Metrics details

We are providing an unedited version of this manuscript to give early access to its findings. Before final publication, the manuscript will undergo further editing. Please note there may be errors present which affect the content, and all legal disclaimers apply.

- Climate change

- Palaeoclimate

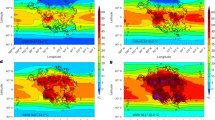

Including an exceptionally warm Northern Hemisphere (NH) summer 1 ,2 , 2023 has been reported as the hottest year on record 3-5 . Contextualizing recent anthropogenic warming against past natural variability is nontrivial, however, because the sparse 19 th century meteorological records tend to be too warm 6 . Here, we combine observed and reconstructed June-August (JJA) surface air temperatures to show that 2023 was the warmest NH extra-tropical summer over the past 2000 years exceeding the 95% confidence range of natural climate variability by more than half a degree Celsius. Comparison of the 2023 JJA warming against the coldest reconstructed summer in 536 CE reveals a maximum range of pre-Anthropocene-to-2023 temperatures of 3.93°C. Although 2023 is consistent with a greenhouse gases-induced warming trend 7 that is amplified by an unfolding El Niño event 8 , this extreme emphasizes the urgency to implement international agreements for carbon emission reduction.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The economic commitment of climate change

Climate extremes likely to drive land mammal extinction during next supercontinent assembly

Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Department of Geography, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

Jan Esper & Max Torbenson

Global Change Research Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Brno, Czech Republic

Jan Esper & Ulf Büntgen

Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Ulf Büntgen

Department of Geography, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jan Esper .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Esper, J., Torbenson, M. & Büntgen, U. 2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07512-y

Download citation

Received : 16 January 2024

Accepted : 02 May 2024

Published : 14 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07512-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Are We Talking Too Much About Mental Health?

Recent studies cast doubt on whether large-scale mental health interventions are making young people better. Some even suggest they can have a negative effect.

By Ellen Barry

In recent years, mental health has become a central subject in childhood and adolescence. Teenagers narrate their psychiatric diagnosis and treatment on TikTok and Instagram. School systems, alarmed by rising levels of distress and self-harm, are introducing preventive coursework in emotional self-regulation and mindfulness.

Now, some researchers warn that we are in danger of overdoing it. Mental health awareness campaigns, they argue, help some young people identify disorders that badly need treatment — but they have a negative effect on others, leading them to over-interpret their symptoms and see themselves as more troubled than they are.

The researchers point to unexpected results in trials of school-based mental health interventions in the United Kingdom and Australia: Students who underwent training in the basics of mindfulness , cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy did not emerge healthier than peers who did not participate, and some were worse off, at least for a while.

And new research from the United States shows that among young people, “self-labeling” as having depression or anxiety is associated with poor coping skills, like avoidance or rumination.

In a paper published last year , two research psychologists at the University of Oxford, Lucy Foulkes and Jack Andrews, coined the term “prevalence inflation” — driven by the reporting of mild or transient symptoms as mental health disorders — and suggested that awareness campaigns were contributing to it.

“It’s creating this message that teenagers are vulnerable, they’re likely to have problems, and the solution is to outsource them to a professional,” said Dr. Foulkes, a Prudence Trust Research Fellow in Oxford’s department of experimental psychology, who has written two books on mental health and adolescence.

Until high-quality research has clarified these unexpected negative effects, they argue, school systems should proceed cautiously with large-scale mental health interventions.

“It’s not that we need to go back to square one, but it’s that we need to press pause and reroute potentially,” Dr. Foulkes said. “It’s possible that something very well-intended has overshot a bit and needs to be brought back in.”

This remains a minority view among specialists in adolescent mental health, who mostly agree that the far more urgent problem is lack of access to treatment.

About 60 percent of young Americans with severe depression receive no treatment, according to Mental Health America, a nonprofit research group. In crisis, desperate families fall back on emergency rooms, where teens often remain for days before a psychiatric bed opens up. There is good reason to embrace a preventive approach, teaching schoolchildren basic skills that might forestall crises later, experts say.

Dr. Foulkes said she understood that her argument runs counter to that consensus, and when she began to present it, she braced for a backlash. To her surprise, she said, many educators reached out to express quiet agreement.

“There’s definitely a fear about being the one to say it,” she said.

A deflating result

In the summer of 2022, the results of a landmark study on mindfulness training in British classrooms landed — like a lead balloon.

The trial, My Resilience in Adolescence, or MYRIAD, was ambitious, meticulous and expansive, following about 28,000 teenagers over eight years. It had been launched in a glow of optimism that the practice would pay off, improving the students’ mental health outcomes in later years.

Half of the teenagers were trained by their teachers to direct their attention to the present moment — breathing, physical sensations or everyday activities — in 10 lessons of 30 to 50 minutes apiece.

The results were disappointing . The authors reported “no support for our hypothesis” that mindfulness training would improve students’ mental health. In fact, students at highest risk for mental health problems did somewhat worse after receiving the training, the authors concluded.

But by the end of the eight-year project, “mindfulness is already embedded in a lot of schools, and there are already organizations making money from selling this program to schools,” said Dr. Foulkes, who had assisted on the study as a postdoctoral research associate. “And it’s very difficult to get the scientific message out there.”

Why, one might ask, would a mental health program do harm?

Researchers in the study speculated that the training programs “bring awareness to upsetting thoughts,” encouraging students to sit with darker feelings, but without providing solutions, especially for societal problems like racism or poverty. They also found that the students didn’t enjoy the sessions and didn’t practice at home.

Another explanation is that mindfulness training could encourage “co-rumination,” the kind of long, unresolved group discussion that churns up problems without finding solutions.

As the MYRIAD results were being analyzed, Dr. Andrews led an evaluation of Climate Schools, an Australian intervention based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy, in which students observed cartoon characters navigating mental health concerns and then answered questions about practices to improve mental health.

Here, too, he found negative effects. Students who had taken the course reported higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms six months and 12 months later.

Co-rumination appears to be higher in girls, who tend to come into the program more distressed, as well as more attuned to their friends, he said. “It might be,” he said, “that they kind of get together and make things a little bit worse for each other.”

Dr. Andrews, a Wellcome Trust research fellow, has since joined an effort to improve Climate Schools by addressing negative effects. And he has concluded that schools should slow down until “we know the evidence base a bit more.” Sometimes, he said, “doing nothing is better than doing something.”

The awareness paradox

One problem with mental health awareness, some research suggests, is that it may not help to put a label to your symptoms.

Isaac Ahuvia, a doctoral candidate at Stony Brook University, recently tested this in a study of 1,423 college students . Twenty-two percent “self-labeled” as having depression, telling researchers “I am depressed” or “I have depression,” but 39 percent met the diagnostic criteria for depression.

He found that the students who self-labeled felt that they had less control over depression and were more likely to catastrophize and less likely to respond to distress by putting their difficulties in perspective, compared with peers who had similar depression symptoms.

Jessica L. Schleider, a co-author of the self-labeling study, said this was no surprise. People who self-label “appear to be viewing depression as a biological inevitability,” she said. “People who don’t view emotions as malleable, view them as set and stuck and uncontrollable, tend to cope less well because they don’t see a point to trying.”

But Dr. Schleider, an associate professor of medical social sciences at Northwestern University and the director of the university’s Lab for Scalable Mental Health, pushed back on the prevalence inflation hypothesis. She disagreed with the claim that students are overdiagnosing themselves, noting that Mr. Ahuvia’s findings suggest otherwise.

Awareness campaigns are bound to have multiple effects, helping some students and not others. And ultimately, she argued, the priority for public health should be reaching young people in the most distress.

“The urgency of the mental health crisis is so clear,” she said. “In the partnerships that I have, the emphasis is on the kids truly struggling right now who have nothing — we need to help them — more so than a possible risk for a subset of kids who aren’t really struggling.”

Maybe, she said, we need to look beyond the “universal, school-assembly-style approach,” to targeted, light-touch interventions, which research has shown can be effective at decreasing anxiety and conduct disorders, especially in younger children.

“There is a risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater,” Dr. Schleider said. “The response can’t be ‘Forget all of it.’ It should be ‘What about this intervention was unhelpful?’”

Other researchers echoed her concern, pointing to studies that show that on average, students benefit from social and emotional learning courses.

One of the largest, a 2023 meta-analysis of 252 classroom programs in 53 countries, found that students who participated performed better academically, displayed better social skills and had lower levels of emotional distress or behavioral problems. In that context, negative effects in a handful of trials appear modest, the researchers said.

“We clearly have not figured out how to do them yet, but I can’t imagine any population-based intervention that the field got right the first time,” said Dr. Andrew J. Gerber, the president and medical director of Silver Hill Hospital and a practicing child and adolescent psychiatrist.

“Really, if you think about almost everything we do in schools, we don’t have great evidence for it working,” he added. “That doesn’t mean we don’t do it. It just means that we’re constantly thinking about ways to improve it.”

‘We want everyone to have it’

These debates are taking place a long way away from classrooms, where mental health curriculums are increasingly commonplace.

Allyson Kangisser, a counselor at Woodsdale Elementary School in Wheeling, W.Va., said the focus in her school is on basic coping skills. In the early grades, students are asked, “What things can you do to take care of yourself when you’re having big feelings?”

Starting in third grade, they take on more complex material, such as watching cartoon characters to distinguish transient stress from chronic conditions like depression. “We’re not trying to have them diagnose themselves,” Ms. Kangisser said. “We are saying, what do you feel — this one? Or this one?”

At the school’s sixth annual mental health fair last month, Woodsdale students walked through a giant inflatable brain, its lobes neatly labeled. They did yoga stretches and talked about regulating their emotions. Ms. Kangisser said the event is valuable precisely because it is universal, so troubled children are not singled out.

“The mental health fair, everybody does it,” she said. “It’s not ‘You need it, and you don’t.’ We want everyone to have it, because you just never know.”

By the time the students reach college, they will have absorbed enormous amounts of information about mental health — from school, but also from social media and from one another.

Dr. Jessica Gold, chief wellness officer for the University of Tennessee system, said the college students she sees are recognizably different — more comfortable speaking about their emotions and more willing to be vulnerable. They also overuse diagnostic terms and have the self-assurance to question a psychiatrist’s judgment.

“It’s sort of a double-edged sword,” she said. “We want people to talk about this more, but we don’t want that to lead to overdiagnosis or incorrect diagnosis or overtreatment. We want it to lead to normalizing of having feelings.”