- Online Degree Explore Bachelor’s & Master’s degrees

- MasterTrack™ Earn credit towards a Master’s degree

- University Certificates Advance your career with graduate-level learning

- Top Courses

- Join for Free

Comparative Research Designs and Methods

Taught in English

Some content may not be translated

Financial aid available

Gain insight into a topic and learn the fundamentals

Instructor: Dirk Berg Schlosser

Included with Coursera Plus

Skills you'll gain

- Research Methods

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- comparative research

- Macro-quantitative methods

Details to know

Add to your LinkedIn profile

See how employees at top companies are mastering in-demand skills

Earn a career certificate

Add this credential to your LinkedIn profile, resume, or CV

Share it on social media and in your performance review

There are 5 modules in this course

Emile Durkheim, one of the founders of modern empirical social science, once stated that the comparative method is the only one that suits the social sciences. But Descartes already had reminded us that “comparaison n’est pas raison”, which means that comparison is not reason (or theory) by itself.

This course provides an introduction and overview of systematic comparative analyses in the social sciences and shows how to employ this method for constructive explanation and theory building. It begins with comparisons of very few cases and specific “most similar” and “most different” research designs. A major part is then devoted to the often occurring situation of dealing with a small number of highly complex cases, for example when comparing EU member states. Latin American political systems, or particular policy areas. In response to this complexity, new approaches and software have been developed in recent years (“Qualitative Comparative Analysis”, QCA, and related methods). These procedures are able to reduce complexity and to arrive at “configurational” solutions based on set theory and Boolean algebra, which are more meaningful in this context than the usual broad-based statistical methods. In the last section, these methods are contrasted with more common statistical comparative methods at the macro-level of states or societies and the respective strengths and weaknesses are discussed. Some basic quantitative or qualitative methodological training is probably useful to get more out of the course, but participants with little methodological training should find no major obstacles to follow.

An introduction to Comparative Research

This module presents fundamental notions of comparative research designs. To begin with, you will be introduced to multi-dimensional matters. Subsequently, you will delve into John Stuart Mill’s methods and limitations.

What's included

6 videos 10 readings 2 quizzes

6 videos • Total 41 minutes

- Multi-dimensional substance matter • 7 minutes • Preview module

- The plastic matter of social sciences • 9 minutes

- Linking levels of analysis • 6 minutes

- Mill's canons • 5 minutes

- Mill‘s methods: Pop's Seafood Platter • 4 minutes

- Mill's methods: limitations • 7 minutes

10 readings • Total 31 minutes

- Three Fundamental notions • 3 minutes

- Multi-dimensional substance matter • 4 minutes

- The plastic matter of social sciences • 4 minutes

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis • 3 minutes

- Linking levels of analysis • 2 minutes

- Coleman's "bathtub" • 3 minutes

- Pop's Seafood Platter • 3 minutes

- Mill's limitations • 3 minutes

- Mill's methods and recent advances • 1 minute

2 quizzes • Total 30 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Epistemological foundations of the social sciences • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Mill's canon • 15 minutes

Comparative Research Designs

This module presents further advances in comparative research designs. To begin with, you will be introduced to case selection and types of research designs. Subsequently, you will delve into most similar and most different designs (MSDO/MDSO) and observe their operationalization.

6 videos 6 readings 2 quizzes

6 videos • Total 48 minutes

- Further advances • 7 minutes • Preview module

- Overview • 7 minutes

- Major steps of research process • 6 minutes

- MSDO/MDSO application • 8 minutes

- Operationalizing similarities and dissimilarities • 9 minutes

- Analysis and interpretation • 8 minutes

6 readings • Total 30 minutes

- Further advances • 4 minutes

- Overview of comparative research designs • 4 minutes

- Selection of variables and cases • 5 minutes

- Operationalizing similarities and dissimilarities • 5 minutes

- Analysis and interpretation • 6 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Further Advances, Comparative Research Designs • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Most similar and most different designs • 15 minutes

QCA Analysis

This module presents Boolean Algebra and the main steps of QCA. The first lesson will introduce basic features of QCA and provide an example of such analysis. The second lesson will focus on QCA applications, troubleshooting, Multi-Value QCA (mv-QCA), and more specific features of QCA.

6 videos 7 readings 2 quizzes

6 videos • Total 40 minutes

- QCA Basics • 8 minutes • Preview module

- QCA Analysis • 9 minutes

- Simple paper and pencil example • 5 minutes

- Troubleshooting Contradictions • 6 minutes

- Threshold setting, necessary and sufficient conditions • 4 minutes

- Multi-Value QCA (mv-QCA) • 6 minutes

7 readings • Total 41 minutes

- QCA Basics • 7 minutes

- QCA Analysis pt.1 • 5 minutes

- QCA Analysis pt.2 • 7 minutes

- Simple paper and pencil example • 7 minutes

- Troubleshooting Contradictions (C) • 6 minutes

- Threshold setting, necessary and sufficient conditions • 3 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Introduction to Boolean Algebra, main steps of QCA • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: QCA applications, troubleshooting, Multi-Value QCA (mv-QCA) • 15 minutes

Fuzzy set analyses

This module presents the basic features of the fuzzy set analyses and application, and analyzes in greater depth QCA. The first lesson will introduce basic features of fuzzy set analyses and provide examples of such analysis. The second lesson will focus on fuzzy set applications, its purposes and advantages, and explores more specific features of QCA.

6 videos • Total 37 minutes

- Fuzzy sets • 6 minutes • Preview module

- Calculation of necessary and sufficient conditions • 3 minutes

- Fuzzy sets. Relationship between condition and outcome as in a triangular scatterplot • 3 minutes

- Principles • 6 minutes

- Lipset's conditions • 7 minutes

- Conclusions • 9 minutes

7 readings • Total 75 minutes

- Fuzzy sets • 10 minutes

- Calculation of necessary and sufficient conditions • 10 minutes

- Fuzzy sets. Relationship between condition and outcome as in a triangular scatterplot • 10 minutes

- Principles • 10 minutes

- Cases • 5 minutes

- Examples • 15 minutes

- Conclusions • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Fuzzy set analyses, basic features • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Fuzzy set applications (fs/qca) • 15 minutes

Macro-quantitative (statistical): Methods and perspectives

This module presents the macro-quantitative (statistical) methods by giving examples of recent research employing them. It analyzes the regression analysis and the various ways of analyzing data. Moreover, it concludes the course and opens to further perspectives on comparative research designs and methods.

6 videos • Total 45 minutes

- Data • 7 minutes • Preview module

- Examples • 6 minutes

- Regression analysis • 6 minutes

- Summary • 8 minutes

- Contrasting macro qualitative and quantitative methods • 8 minutes

- Continuing debates: prospects • 6 minutes

6 readings • Total 75 minutes

- Data • 10 minutes

- Examples • 10 minutes

- Regression analysis • 10 minutes

- Summary • 15 minutes

- Contrasting macro qualitative and quantitative methods • 15 minutes

- Continuing debates, prospects • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Macro-quantitative (statistical) Methods • 15 minutes

- Challenge yourself: Conclusions and Perspectives • 15 minutes

Founded in 1224, Federico II is the oldest lay University in Europe. With its "Federica Web Learning" Center, it is the leader in Europe for open access multimedia education, and in the world's top ten for the production of MOOCs for providing new links between higher education and lifelong learning. Find out more on www.federica.eu.

Recommended if you're interested in Governance and Society

Arizona State University

Extracting Value from Dark Data: ULEADD

Peking University

社会调查与研究方法 (上)Methodologies in Social Research (Part I)

University of Minnesota

Social Determinants of Health: Methodological Opportunities

Coursera Project Network

Unleash Student Creativity with Buncee

Guided Project

Why people choose Coursera for their career

Open new doors with Coursera Plus

Unlimited access to 7,000+ world-class courses, hands-on projects, and job-ready certificate programs - all included in your subscription

Advance your career with an online degree

Earn a degree from world-class universities - 100% online

Join over 3,400 global companies that choose Coursera for Business

Upskill your employees to excel in the digital economy

Frequently asked questions

When will i have access to the lectures and assignments.

Access to lectures and assignments depends on your type of enrollment. If you take a course in audit mode, you will be able to see most course materials for free. To access graded assignments and to earn a Certificate, you will need to purchase the Certificate experience, during or after your audit. If you don't see the audit option:

The course may not offer an audit option. You can try a Free Trial instead, or apply for Financial Aid.

The course may offer 'Full Course, No Certificate' instead. This option lets you see all course materials, submit required assessments, and get a final grade. This also means that you will not be able to purchase a Certificate experience.

What will I get if I purchase the Certificate?

When you purchase a Certificate you get access to all course materials, including graded assignments. Upon completing the course, your electronic Certificate will be added to your Accomplishments page - from there, you can print your Certificate or add it to your LinkedIn profile. If you only want to read and view the course content, you can audit the course for free.

What is the refund policy?

You will be eligible for a full refund until two weeks after your payment date, or (for courses that have just launched) until two weeks after the first session of the course begins, whichever is later. You cannot receive a refund once you’ve earned a Course Certificate, even if you complete the course within the two-week refund period. See our full refund policy Opens in a new tab .

Is financial aid available?

Yes. In select learning programs, you can apply for financial aid or a scholarship if you can’t afford the enrollment fee. If fin aid or scholarship is available for your learning program selection, you’ll find a link to apply on the description page.

More questions

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Published on June 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

When you start planning a research project, developing research questions and creating a research design , you will have to make various decisions about the type of research you want to do.

There are many ways to categorize different types of research. The words you use to describe your research depend on your discipline and field. In general, though, the form your research design takes will be shaped by:

- The type of knowledge you aim to produce

- The type of data you will collect and analyze

- The sampling methods , timescale and location of the research

This article takes a look at some common distinctions made between different types of research and outlines the key differences between them.

Table of contents

Types of research aims, types of research data, types of sampling, timescale, and location, other interesting articles.

The first thing to consider is what kind of knowledge your research aims to contribute.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The next thing to consider is what type of data you will collect. Each kind of data is associated with a range of specific research methods and procedures.

Finally, you have to consider three closely related questions: how will you select the subjects or participants of the research? When and how often will you collect data from your subjects? And where will the research take place?

Keep in mind that the methods that you choose bring with them different risk factors and types of research bias . Biases aren’t completely avoidable, but can heavily impact the validity and reliability of your findings if left unchecked.

Choosing between all these different research types is part of the process of creating your research design , which determines exactly how your research will be conducted. But the type of research is only the first step: next, you have to make more concrete decisions about your research methods and the details of the study.

Read more about creating a research design

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/types-of-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

Characteristics of a Comparative Research Design

Hannah richardson, 28 jun 2018.

Comparative research essentially compares two groups in an attempt to draw a conclusion about them. Researchers attempt to identify and analyze similarities and differences between groups, and these studies are most often cross-national, comparing two separate people groups. Comparative studies can be used to increase understanding between cultures and societies and create a foundation for compromise and collaboration. These studies contain both quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Explore this article

- Comparative Quantitative

- Comparative Qualitative

- When to Use It

- When Not to Use It

1 Comparative Quantitative

Quantitative, or experimental, research is characterized by the manipulation of an independent variable to measure and explain its influence on a dependent variable. Because comparative research studies analyze two different groups -- which may have very different social contexts -- it is difficult to establish the parameters of research. Such studies might seek to compare, for example, large amounts of demographic or employment data from different nations that define or measure relevant research elements differently.

However, the methods for statistical analysis of data inherent in quantitative research are still helpful in establishing correlations in comparative studies. Also, the need for a specific research question in quantitative research helps comparative researchers narrow down and establish a more specific comparative research question.

2 Comparative Qualitative

Qualitative, or nonexperimental, is characterized by observation and recording outcomes without manipulation. In comparative research, data are collected primarily by observation, and the goal is to determine similarities and differences that are related to the particular situation or environment of the two groups. These similarities and differences are identified through qualitative observation methods. Additionally, some researchers have favored designing comparative studies around a variety of case studies in which individuals are observed and behaviors are recorded. The results of each case are then compared across people groups.

3 When to Use It

Comparative research studies should be used when comparing two people groups, often cross-nationally. These studies analyze the similarities and differences between these two groups in an attempt to better understand both groups. Comparisons lead to new insights and better understanding of all participants involved. These studies also require collaboration, strong teams, advanced technologies and access to international databases, making them more expensive. Use comparative research design when the necessary funding and resources are available.

4 When Not to Use It

Do not use comparative research design with little funding, limited access to necessary technology and few team members. Because of the larger scale of these studies, they should be conducted only if adequate population samples are available. Additionally, data within these studies require extensive measurement analysis; if the necessary organizational and technological resources are not available, a comparative study should not be used. Do not use a comparative design if data are not able to be measured accurately and analyzed with fidelity and validity.

- 1 San Jose State University: Selected Issues in Study Design

- 2 University of Surrey: Social Research Update 13: Comparative Research Methods

About the Author

Hannah Richardson has a Master's degree in Special Education from Vanderbilt University and a Bacheor of Arts in English. She has been a writer since 2004 and wrote regularly for the sports and features sections of "The Technician" newspaper, as well as "Coastwach" magazine. Richardson also served as the co-editor-in-chief of "Windhover," an award-winning literary and arts magazine. She is currently teaching at a middle school.

Related Articles

Research Study Design Types

Correlational Methods vs. Experimental Methods

Different Types of Methodologies

Quasi-Experiment Advantages & Disadvantages

What Are the Advantages & Disadvantages of Non-Experimental...

Independent vs. Dependent Variables in Sociology

Methods of Research Design

Qualitative Research Pros & Cons

How to Form a Theoretical Study of a Dissertation

What Is the Difference Between Internal & External...

Difference Between Conceptual & Theoretical Framework

The Advantages of Exploratory Research Design

What Is Quantitative Research?

What is a Dissertation?

What Are the Advantages & Disadvantages of Correlation...

What Is the Meaning of the Descriptive Method in Research?

How to Use Qualitative Research Methods in a Case Study...

How to Tabulate Survey Results

How to Cross Validate Qualitative Research Results

Types of Descriptive Research Methods

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Comparative effectiveness research for the clinician researcher: a framework for making a methodological design choice

Cylie m. williams.

1 Peninsula Health, Community Health, PO Box 52, Frankston, Melbourne, Victoria 3199 Australia

2 Monash University, School of Physiotherapy, Melbourne, Australia

3 Monash Health, Allied Health Research Unit, Melbourne, Australia

Elizabeth H. Skinner

4 Western Health, Allied Health, Melbourne, Australia

Alicia M. James

Jill l. cook, steven m. mcphail.

5 Queensland University of Technology, School of Public Health and Social Work, Brisbane, Australia

Terry P. Haines

Comparative effectiveness research compares two active forms of treatment or usual care in comparison with usual care with an additional intervention element. These types of study are commonly conducted following a placebo or no active treatment trial. Research designs with a placebo or non-active treatment arm can be challenging for the clinician researcher when conducted within the healthcare environment with patients attending for treatment.

A framework for conducting comparative effectiveness research is needed, particularly for interventions for which there are no strong regulatory requirements that must be met prior to their introduction into usual care. We argue for a broader use of comparative effectiveness research to achieve translatable real-world clinical research. These types of research design also affect the rapid uptake of evidence-based clinical practice within the healthcare setting.

This framework includes questions to guide the clinician researcher into the most appropriate trial design to measure treatment effect. These questions include consideration given to current treatment provision during usual care, known treatment effectiveness, side effects of treatments, economic impact, and the setting in which the research is being undertaken.

Comparative effectiveness research compares two active forms of treatment or usual care in comparison with usual care with an additional intervention element. Comparative effectiveness research differs from study designs that have an inactive control, such as a ‘no-intervention’ or placebo group. In pharmaceutical research, trial designs in which placebo drugs are tested against the trial medication are often labeled ‘Phase III’ trials. Phase III trials aim to produce high-quality evidence of intervention efficacy and are important to identify potential side effects and benefits. Health outcome research with this study design involves the placebo being non-treatment or a ‘sham’ treatment option [ 1 ].

Traditionally, comparative effectiveness research is conducted following completion of a Phase III placebo control trial [ 2 – 4 ]. It is possible that comparative effectiveness research might not determine whether one treatment has clinical beneficence, because the comparator treatment might be harmful, irrelevant, or ineffective. This is unless the comparator treatment has already demonstrated superiority to a placebo [ 2 ]. Moreover, comparing an active treatment to an inactive control will be more likely to produce larger effect sizes than a comparison of two active treatments [ 5 ], requiring smaller sample sizes and lower costs to establish or refute the effectiveness of a treatment. Historically, then, treatments only become candidates for comparative effectiveness research to establish superiority, after a treatment has demonstrated efficacy against an inactive control.

Frequently, the provision of health interventions precedes development of the evidence base directly supporting their use [ 6 ]. Some service-provision contexts are highly regulated and high standards of evidence are required before an intervention can be provided (such as pharmacological interventions and device use). However, this is not universally the case for all services that may be provided in healthcare interventions. Despite this, there may be expectation from the individual patient and the public that individuals who present to a health service will receive some form of care deemed appropriate by treating clinicians, even in the absence of research-based evidence supporting this. This expectation may be amplified in publicly subsidized health services (as is largely the case in Canada, the UK, Australia, and many other developed nations) [ 7 – 9 ]. If a treatment is already widely employed by health professionals and is accepted by patients as a component of usual care, then it is important to consider the ethics and practicality of attempting a placebo or no-intervention control trial in this context. In this context, comparative effectiveness research could provide valuable insights to treatment effectiveness, disease pathophysiology, and economic efficiency in service delivery, with greater research feasibility than the traditional paradigm just described. Further, some authors have argued that studies with inactive control groups are used when comparative effectiveness research designs are more appropriate [ 10 ]. We propose and justify a framework for conducting research that argues for the broader use of comparative effectiveness research to achieve more feasible and translatable real-world clinical research.

This debate is important for the research community; particularly those engaged in the planning and execution of research in clinical practice settings, particularly in the provision of non-pharmacological, non-device type interventions. The ethical, preferential, and pragmatic implications from active versus inactive comparator selection in clinical trials not only influence the range of theoretical conclusions that could be drawn from a study, but also the lived experiences of patients and their treating clinical teams. The comparator selection will also have important implications for policy and practice when considering potential translation into clinical settings. It is these implications that affect the clinical researcher’s methodological design choice and justification.

The decision-making framework takes the form of a decision tree (Fig. 1 ) to determine when a comparative effectiveness study can be justified and is particularly relevant to the provision of services that do not have a tight regulatory framework governing when an intervention can be used as part of usual care. This framework is headed by Level 1 questions (demarcated by a question within an oval), which feed into decision nodes (demarcated by rectangles), which end in decision points (demarcated by diamonds). Each question is discussed with clinical examples to illustrate relevant points.

Comparative effectiveness research decision-making framework. Treatment A represents any treatment for a particular condition, which may or may not be a component of usual care to manage that condition. Treatment B is used to represent our treatment of interest. Where the response is unknown, the user should choose the NO response

Treatment A is any treatment for a particular condition that may or may not be a component of usual care to manage that condition. Treatment B is our treatment of interest. The framework results in three possible recommendations: that either (i) a study design comparing Treatment B with no active intervention could be used, or (ii) a study design comparing Treatment A, Treatment B and no active intervention should be used, or (iii) a comparative effectiveness study (Treatment A versus Treatment B) should be used.

Level 1 questions

Is the condition of interest being managed by any treatment as part of usual care either locally or internationally.

Researchers first need to identify what treatments are being offered as usual care to their target patient population to consider whether to perform a comparative effectiveness research (Treatment A versus B) or use a design comparing Treatment B with an inactive control. Usual care has been shown to vary across healthcare settings for many interventions [ 11 , 12 ]; thus, researchers should understand that usual care in their context might not be usual care universally. Consequently, researchers must consider what comprises usual care both in their local context and more broadly.

If there is no usual care treatment, then it is practical to undertake a design comparing Treatment B with no active treatment (Fig. 1 , Exit 1). If there is strong evidence of treatment effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness of Treatment A that is not a component of usual care locally, this treatment should be considered for inclusion in the study. This situation can occur from delayed translation of research evidence into practice, with an estimated 17 years to implement only 14 % of research in evidence-based care [ 13 ]. In this circumstance, although it may be more feasible to use a Treatment B versus no active treatment design, the value of this research will be very limited, compared with comparative effectiveness research of Treatment A versus B. If the condition is currently being treated as part of usual care, then the researcher should consider the alternate Level 1 question for progression to Level 2.

As an example, prevention of falls is a safety priority within all healthcare sectors and most healthcare services have mitigation strategies in place. Evaluation of the effectiveness of different fall-prevention strategies within the hospital setting would most commonly require a comparative design [ 14 ]. A non-active treatment in this instance would mean withdrawal of a service that might be perceived as essential, a governmental health priority, and already integrated in the healthcare system.

Is there evidence of Treatment A’s effectiveness compared with no active intervention beyond usual care?

If there is evidence of Treatment A’s effectiveness compared with a placebo or no active treatment, then we progress to Question 3. If Treatment A has limited evidence, a comparative effectiveness research design of Treatment B versus no active treatment design can be considered. By comparing Treatment A with Treatment B, researchers would generate relevant research evidence for their local healthcare setting (is Treatment B superior to usual care or Treatment A?) and other healthcare settings that use Treatment A as their usual care. This design may be particularly useful when the local population is targeted and extrapolation of research findings is less relevant.

For example, the success of chronic disease management programs (Treatment A) run in different Aboriginal communities were highly influenced by unique characteristics and local cultures and traditions [ 15 ]. Therefore, taking Treatment A to an urban setting or non-indigenous setting with those unique characteristics will render Treatment A ineffectual. The use of Treatment A may also be particularly useful in circumstances where the condition of interest has an uncertain etiology and the competing treatments under consideration address different pathophysiological pathways. However, if Treatment A has limited use beyond the research location and there are no compelling reasons to extrapolate findings more broadly applicable, then Treatment B versus no active control design may be suitable.

The key points clinical researchers should consider are:

- The commonality of the treatment within usual care

- The success of established treatments in localized or unique population groups only

- Established effectiveness of treatments compared with placebo or no active treatment

Level 2 questions

Do the benefits of treatment a exceed the side effects when compared with no active intervention beyond usual care.

Where Treatment A is known to be effective, yet produces side effects, the severity, risk of occurrence, and duration of the side effects should be considered before it is used as a comparator for Treatment B. If the risk or potential severity of Treatment A is unacceptably high or is uncertain, and there are no other potential comparative treatments available, a study design comparing Treatment B with no active intervention should be used (Fig. 1 , Exit 2). Whether Treatment A remains a component of usual care should also be considered. If the side effects of Treatment A are considered acceptable, comparative effectiveness research may still be warranted.

The clinician researcher may also be challenged when the risk of the Treatment A and risk of Treatment B are unknown or when one is marginally more risky than the other [ 16 ]. Unknown risk comparison between the two treatments when using this framework should be considered as uncertain and the design of Treatment A versus Treatment B or Treatment B versus no intervention or a three-arm trial investigating Treatment A, B and no intervention is potentially justified (Fig. 1 , Exit 3).

A good example of risk comparison is the use of exercise programs. Walking has many health benefits, particularly for older adults, and has also demonstrated benefits in reducing falls [ 17 ]. Exercise programs inclusive of walking training have been shown to prevent falls but brisk walking programs for people at high risk of falls can increase the number of falls experienced [ 18 ]. The pragmatic approach of risk and design of comparative effectiveness research could better demonstrate the effect than a placebo (no active treatment) based trial.

- Risk of treatment side effects (including death) in the design

- Acceptable levels of risk are present for all treatments

Level 3 question

Does treatment a have a sufficient overall net benefit, when all costs and consequences or benefits are considered to deem it superior to a ‘no active intervention beyond usual care’ condition.

Simply being effective and free of unacceptable side effects is insufficient to warrant Treatment A being the standard for comparison. If the cost of providing Treatment A is so high that it renders its benefits insignificant compared with its costs, or Treatment A has been shown not to be cost-effective, or the cost-effectiveness is below acceptable thresholds, it is clear that Treatment A is not a realistic comparator. Some have advocated for a cost-effectiveness (cost-utility) threshold of $50,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained as being an appropriate threshold, though there is some disagreement about this and different societies might have different capacities to afford such a threshold [ 19 ]. Based on these considerations, one should further contemplate whether Treatment A should remain a component of usual care. If no other potential comparative treatments are available, a study design comparing Treatment B with no active intervention is recommended (Fig. 1 , Exit 4).

If Treatment A does have demonstrated efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness compared with no active treatment, it is unethical to pursue a study design comparing Treatment B with no active intervention, where patients providing consent are being asked to forego a safe and effective treatment that they otherwise would have received. This is an unethical approach and also unfeasible, as the recruitment rates could be very poor. However, Treatment A may be reasonable to include as a comparison if it is usually purchased by the potential participant and is made available through the trial.

The methodological design of a diabetic foot wound study illustrates the importance of health economics [ 20 ]. This study compared the outcomes of Treatment A (non-surgical sharps debridement) with Treatment B (low-frequency ultrasonic debridement). Empirical evidence supports the need for wound care and non-intervention would place the patient at risk of further wound deterioration, potentially resulting in loss of limb loss or death [ 21 ]. High consumable expenses and increased short-term time demands compared with low expense and longer term decreased time demands must also be considered. The value of information should also be considered, with the existing levels of evidence weighed up against the opportunity cost of using research funds for another purpose in the context of the probability that Treatment A is cost-effective [ 22 ].

- Economic evaluation and effect on treatment

- Understanding the health economics of treatment based on effectiveness will guide clinical practice

- Not all treatment costs are known but establishing these can guide evidence-based practice or research design

Level 4 question

Is the patient (potential participant) presenting to a health service or to a university- or research-administered clinic.

If Treatment A is not a component of usual care, one of three alternatives is being considered by the researcher: (i) conducting a comparative effectiveness study of Treatment B in addition to usual care versus usual care alone, (ii) introducing Treatment A to usual care for the purpose of the trial and then comparing it with Treatment B in addition to usual care, (iii) conducting a trial of Treatment B versus no active control. If the researcher is considering option (i), usual care should itself be considered to be Treatment A, and the researcher should return to Question 2 in our framework.

There is a recent focus on the importance of health research conducted by clinicians within health service settings as distinct from health research conducted by university-based academics within university settings [ 23 , 24 ]. People who present to health services expect to receive treatment for their complaint, unlike a person responding to a research trial advertisement, where it is clearly stated that participants might not receive active treatment. It is in these circumstances that option (ii) is most appropriate.

Using research designs (option iii) comparing Treatment B with no active control within a health service setting poses challenges to clinical staff caring for patients, as they need to consider the ethics of enrolling patients into a study who might not receive an active treatment (Fig. 1 , Exit 4). This is not to imply that the use of a non-active control is unethical. Where there is no evidence of effectiveness, this should be considered within the study design and in relation to the other framework questions about the risk and use of the treatment within usual care. Clinicians will need to establish the effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness of the treatments and their impact on other health services, weighed against their concern for the patient’s well-being and the possibility that no treatment will be provided [ 25 ]. This is referred to as clinical equipoise.

Patients have a right to access publicly available health interventions, regardless of the presence of a trial. Comparing Treatment B with no active control is inappropriate, owing to usual care being withheld. However, if there is insufficient evidence that usual care is effective, or sufficient evidence that adverse events are likely, the treatment is prohibitive to implement within clinical practice, or the cost of the intervention is significant, a sham or placebo-based trial should be implemented.

Comparative effectiveness research evaluating different treatment options of heel pain within a community health service [ 26 ] highlighted the importance of the research setting. Children with heel pain who attended the health service for treatment were recruited for this study. Children and parents were asked on enrollment if they would participate if there were a potential assignment to a ‘no-intervention’ group. Of the 124 participants, only 7 % ( n = 9) agreed that they would participate if placed into a group with no treatment [ 26 ].

- The research setting can impact the design of research

- Clinical equipoise challenges clinicians during recruitment into research in the healthcare setting

- Patients enter a healthcare service for treatment; entering a clinical trial is not the presentation motive

This framework describes and examines a decision structure for comparator selection in comparative effectiveness research based on current interventions, risk, and setting. While scientific rigor is critical, researchers in clinical contexts have additional considerations related to existing practice, patient safety, and outcomes. It is proposed that when trials are conducted in healthcare settings, a comparative effectiveness research design should be the preferred methodology to placebo-based trial design, provided that evidence for treatment options, risk, and setting have all been carefully considered.

Authors’ contributions

CMW and TPH drafted the framework and manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the framework and manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Cylie M. Williams, Phone: +61 3 9784 8100, Email: ua.vog.civ.nchp@smailliweilyc .

Elizabeth H. Skinner, Email: [email protected] .

Alicia M. James, Email: ua.vog.civ.nchp@semajaicila .

Jill L. Cook, Email: [email protected] .

Steven M. McPhail, Email: [email protected] .

Terry P. Haines, Email: [email protected] .

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

This article is part of the research topic.

Climate Change and Urban Resilience

Charting Climate Adaptation Integration in Smart Building Rating Systems: A Comparative Study Provisionally Accepted

- 1 Munich University of Applied Sciences, Germany

- 2 EU Business School, Germany

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

As the world is engulfed with the growing impacts of climate change, the integration of climate adaptation measures into building performance requirements is essential. In the era of the 4th industrial revolution, smart buildings are expected to be the next frontier in the realm of building rating systems after sustainability-based one. Smart buildings can play a pivotal role in addressing the evolving challenges of changing climate due to their temporal and spatial cross-scale nature.Methods: This study assesses the integration of climate hazard adaptation options within four prominent smart building rating systems (SBRS). Using a sectoral analysis approach and a 4-point Likert scale, we systematically evaluate the extent to which these rating systems incorporate climate adaptation measures directly or indirectly across multiple building sectors. We identify strengths and weaknesses in each system's approach, highlighting areas where adaptation options are more profoundly addressed and sectors that require further attention.The evaluation results reveal variations in the comprehensiveness of climate adaptation integration among the smart building rating systems. The SRBS show a high level of integration of climate adaptation measures in the urban sectors intrinsically tied to the smart building paradigm, such as communication sector, and the human wellbeing and organization sector. Nevertheless, the study also revealed that SBRS almost universally fall short in covering other vital domains such as building envelope and structure, water and sanitation, and blue and green infrastructure.Discussions: Complementing the SBRS with sustainability rating systems (GBRS) can effectively address the limitations in climate adaptation integration within SBRS. Moreover, the inherent interconnectedness of smart buildings with their surrounding infrastructure and the broader urban environment underscores the importance of the cross-scale consideration in the building rating domain in general and in climate related topics in particular, this interconnectedness also highlights a smart building's reliance on its surrounding context for optimal functionality and the interdependency between the building and urban scale.

Keywords: Smart Building, Climate resilience, climate adaptation, sustainability, Building rating systems

Received: 07 Nov 2023; Accepted: 08 Apr 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Khoja and Danylenko. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mx. Ahmed Khoja, Munich University of Applied Sciences, Munich, Germany

People also looked at

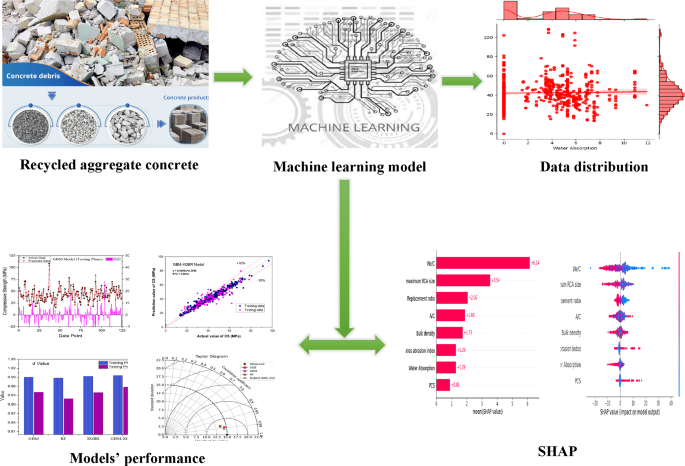

A comparative study of ensemble machine learning models for compressive strength prediction in recycled aggregate concrete and parametric analysis

- Original Paper

- Published: 07 April 2024

Cite this article

- Pobithra Das 1 ,

- Abul Kashem 1 , 2 ,

- Jasim Uddin Rahat 1 &

- Rezaul Karim 3

22 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Nowadays, recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) has been most extensively applied in the construction industry as a sustainable resource to decrease carbon dioxide emissions and construction waste. Predicting the compressive strength (CS) of RAC is crucial to understanding the behavior and performance of this environment-friendly (EF) concrete. This paper developed the models for forecasting the CS of RAC materials using hybrid machine learning (ML) models and ML with hyperparameter tuning techniques. The RAC experimental datasets were collected from the research literature, where the datasets were utilized for the 70% training and 30% testing phases of the models. This study used some renowned AI models such as XGBoost (Extreme Gradient-Boosting), GBM (Gradient Boosting Machine), RF (Random Forest), and the hybrid GBM–XGBoost model. The ensemble GBM–XGBoost algorithm showed the highest level of accuracy for CS prediction, with \({R}^{2}=\) 0.982 for the training stage and \({R}^{2}=\) 0.793 for the testing stage. The evaluation of the statistical indicators of AI algorithms revealed that the ensemble GBM–XBR had a more accurate prediction. The SHapley Additive exPlainations (SHAP) analysis showed that the effective water–cement ratio (We/C), nominal maximum RCA size, and replacement ratio positively correlated with the CS of RAC, which were the most significant parameters. The partial dependence plots (PDP) study displayed the optimal quantity of each parameter, which could help in mix design to achieve a targeted CS. Furthermore, the output of both the SHAP and PDP analyses could assist researchers and the industry in determining the quality of raw ingredients when preparing RAC.

Graphical abstract

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ahmed A, Song W, Zhang Y, Haque MA, Liu X (2023) Hybrid BO-XGBoost and BO-RF models for the strength prediction of self-compacting mortars with parametric analysis. Materials 16:4366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16124366

Article Google Scholar

Akhtar M, Halahla A, Almasri A (2021) Experimental study on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete under high temperature. SDHM Struct Durab Health Monit 15:335–348. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2021.015988

Alhakeem ZM, Jebur YM, Henedy SN, Imran H, Bernardo LFA, Hussein HM (2022) Prediction of ecofriendly concrete compressive strength using gradient boosting regression tree combined with GridSearchCV hyperparameter-optimization techniques. Materials. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217432

Beltrán MG, Agrela F, Barbudo A, Ayuso J, Ramírez A (2014a) Mechanical and durability properties of concretes manufactured with biomass bottom ash and recycled coarse aggregates. Constr Build Mater 72:231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.09.019

Beltrán MG, Barbudo A, Agrela F, Galvín AP, Jiménez JR (2014b) Effect of cement addition on the properties of recycled concretes to reach control concretes strengths. J Clean Prod 79:124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.053

Bhamare DK, Saikia P, Rathod MK, Rakshit D, Banerjee J (2021) A machine learning and deep learning based approach to predict the thermal performance of phase change material integrated building envelope. Build Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107927

Breiman L (2001) Random forests

Cakiroglu C, Shahjalal Md, Islam K, Mahmood SMF, Billah AHMM, Nehdi ML (2023) Explainable ensemble learning data-driven modeling of mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced rubberized recycled aggregate concrete. J Build Eng 76:107279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107279

Carneiro JA, Lima PRL, Leite MB, Toledo Filho RD (2014) Compressive stress-strain behavior of steel fiber reinforced-recycled aggregate concrete. Cem Concr Compos 46:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.11.006

Chen T, Guestrin (2016) XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, association for computing machinery, pp 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785

Corinaldesi V (2010) Mechanical and elastic behaviour of concretes made of recycled-concrete coarse aggregates. Constr Build Mater 24:1616–1620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.02.031

da Rocha CG, Sattler MA (2009) A discussion on the reuse of building components in Brazil: an analysis of major social, economical and legal factors. Resour Conserv Recycl 54:104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2009.07.004

Dabiri H, Kioumarsi M, Kheyroddin A, Kandiri A, Sartipi F (2022) Compressive strength of concrete with recycled aggregate; a machine learning-based evaluation. Clean Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2022.100044

Dahiya N, Saini B, Chalak HD (2021) Gradient boosting-based regression modelling for estimating the time period of the irregular precast concrete structural system with cross bracing. J King Saud Univ Eng Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2021.08.004

Derogar S, Ince C, Yatbaz HY, Ever E (2022) Prediction of punching shear strength of slab-column connections: a comprehensive evaluation of machine learning and deep learning based approaches. Mech Adv Mater Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2022.2134950

DeRousseau MA, Laftchiev E, Kasprzyk JR, Rajagopalan B, Srubar WV (2019) A comparison of machine learning methods for predicting the compressive strength of field-placed concrete. Constr Build Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.08.042

Dilbas H, Şimşek M, Çakir Ö (2014) An investigation on mechanical and physical properties of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) with and without silica fume. Constr Build Mater 61:50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.02.057

Duan ZH, Poon CS (2014) Properties of recycled aggregate concrete made with recycled aggregates with different amounts of old adhered mortars. Mater Des 58:19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2014.01.044

Ekanayake IU, Palitha S, Gamage S, Meddage DPP, Wijesooriya K, Mohotti D (2023) Predicting adhesion strength of micropatterned surfaces using gradient boosting models and explainable artificial intelligence visualizations. Mater Today Commun 36:106545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106545

El Khessaimi Y, El Hafiane Y, Peyratout C, Tamine K, Adly S, Barkatou M, Smith A (n.d.) Towards accelerating the development of calcined clay cements: data-driven prediction of compressive strength exploiting machine learning algorithms. https://cnrs.hal.science/hal-03948449

Fawagreh K, Gaber MM, Elyan E (2014) Random forests: from early developments to recent advancements. Syst Sci Control Eng 2:602–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2014.956265

Folino P, Xargay H (2014) Recycled aggregate concrete—mechanical behavior under uniaxial and triaxial compression. Constr Build Mater 56:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.01.073

Friedman JH (2001) Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013203451

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Gholampour A, Gandomi AH, Ozbakkaloglu T (2017) New formulations for mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete using gene expression programming. Constr Build Mater 130:122–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.10.114

Ghunimat D, Alzoubi AE, Alzboon A, Hanandeh S (2023) Prediction of concrete compressive strength with GGBFS and fly ash using multilayer perceptron algorithm, random forest regression and k-nearest neighbor regression. Asian J Civ Eng 24:169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-022-00495-z

González-Taboada I, González-Fonteboa B, Martínez-Abella F, Pérez-Ordóñez JL (2016) Prediction of the mechanical properties of structural recycled concrete using multivariable regression and genetic programming. Constr Build Mater 106:480–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.136

Guo J, Yun S, Meng Y, He N, Ye D, Zhao Z, Jia L, Yang L (2023) Prediction of heating and cooling loads based on light gradient boosting machine algorithms. Build Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110252

Han Q, Gui C, Xu J, Lacidogna G (2019) A generalized method to predict the compressive strength of high-performance concrete by improved random forest algorithm. Constr Build Mater 226:734–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.315

Ismail S, Ramli M (2013) Engineering properties of treated recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) for structural applications. Constr Build Mater 44:464–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.014

Kaloop MR, Kumar D, Samui P, Hu JW, Kim D (2020) Compressive strength prediction of high-performance concrete using gradient tree boosting machine. Constr Build Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120198

Kam Ho T (n.d.) Random decision forests

Kang MC, Yoo DY, Gupta R (2021) Machine learning-based prediction for compressive and flexural strengths of steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr Build Mater 266:121117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121117

Kashem A, Das P (2023) Compressive strength prediction of high-strength concrete using hybrid machine learning approaches by incorporating SHAP analysis. Asian J Civ Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00707-0

Kumar Tipu R, Panchal VR, Pandya KS (2022) An ensemble approach to improve BPNN model precision for predicting compressive strength of high-performance concrete. Structures 45:500–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.09.046

Lecun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G (2015) Deep learning. Nature 521:436–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14539

Li Y, Shen J, Lin H, Li H, Lv J, Feng S, Ci J (2022) The data-driven research on bond strength between fly ash-based geopolymer concrete and reinforcing bars. Constr Build Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129384

Limbachiya MC, Leelawat T, Dhir RK (2000) Use of recycled concrete aggregate in high-strength concrete. Mater Struct 33:574–580

López Gayarre F, López-Colina Pérez C, Serrano López MA, Domingo Cabo A (2014) The effect of curing conditions on the compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr Build Mater 53:260–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.11.112

Lundberg SM, Allen PG, Lee S-I (n.d.) A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. https://github.com/slundberg/shap .

Mahjoubi S, Barhemat R, Guo P, Meng W, Bao Y (2021) Prediction and multi-objective optimization of mechanical, economical, and environmental properties for strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCC) based on automated machine learning and metaheuristic algorithms. J Clean Prod 329:129665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129665

Marani A, Nehdi ML (2020) Machine learning prediction of compressive strength for phase change materials integrated cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120286

Matias D, De Brito J, Rosa A, Pedro D (2013) Mechanical properties of concrete produced with recycled coarse aggregates—influence of the use of superplasticizers. Constr Build Mater 44:101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.011

Nazari A, Riahi S (2011) The effects of TiO 2 nanoparticles on physical, thermal and mechanical properties of concrete using ground granulated blast furnace slag as binder. Mater Sci Eng A 528:2085–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2010.11.070

Özcan F, Atiş CD, Karahan O, Uncuoǧlu E, Tanyildizi H (2009) Comparison of artificial neural network and fuzzy logic models for prediction of long-term compressive strength of silica fume concrete. Adv Eng Softw 40:856–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2009.01.005

Patil SV, Balakrishna Rao K, Nayak G (2021) Prediction of recycled coarse aggregate concrete mechanical properties using multiple linear regression and artificial neural network. J Eng Des Technol. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-07-2021-0373

Pedro D, de Brito J, Evangelista L (2015) Performance of concrete made with aggregates recycled from precasting industry waste: influence of the crushing process. Mater Struct Materiaux Et Constructions 48:3965–3978. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-014-0456-7

Pepe M, Toledo Filho RD, Koenders EAB, Martinelli E (2014) Alternative processing procedures for recycled aggregates in structural concrete. Constr Build Mater 69:124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.06.084

Phoeuk M, Kwon M (2023) Accuracy prediction of compressive strength of concrete incorporating recycled aggregate using ensemble learning algorithms: multinational dataset. Adv Civ Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5076429

Poon CS, Kou SC, Lam L (2007) Influence of recycled aggregate on slump and bleeding of fresh concrete. Mater Struct Materiaux Et Constructions 40:981–988. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-006-9192-y

Probst P, Wright M, Boulesteix A-L (2018) Hyperparameters and tuning strategies for random forest. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1301

Quan Tran V, Quoc Dang V, Si Ho L (2022) Evaluating compressive strength of concrete made with recycled concrete aggregates using machine learning approach. Constr Build Mater 323:126578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126578

Rajković D, Marjanović Jeromela A, Pezo L, Lončar B, Grahovac N, Kondić Špika A (2023) Artificial neural network and random forest regression models for modelling fatty acid and tocopherol content in oil of winter rapeseed. J Food Compos Anal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2022.105020

Ramadevi K, Chitra R (2017) Concrete using recycled aggregates. Int J Civ Eng Technol (IJCIET) 8:413–419

Google Scholar

Rashid K, Rehman MU, de Brito J, Ghafoor H (2020) Multi-criteria optimization of recycled aggregate concrete mixes. J Clean Prod 276:124316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124316

Ray S, Rahman MM, Haque M, Hasan MW, Alam MM (2023) Performance evaluation of SVM and GBM in predicting compressive and splitting tensile strength of concrete prepared with ceramic waste and nylon fiber. J King Saud Univ Eng Sci 35:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2021.02.009

Sabău M, Remolina Duran J (2022) Prediction of compressive strength of general-use concrete mixes with recycled concrete aggregate. Int J Pavement Res Technol 15:73–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42947-021-00012-6

Saleem M, Gutierrez H (2021) Using artificial neural network and non-destructive test for crack detection in concrete surrounding the embedded steel reinforcement. Struct Concr 22:2849–2867. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202000767

Silva RV, Jiménez JR, Agrela F, De Brito J (2018) Real-scale applications of recycled aggregate concrete. New trends in eco-efficient and recycled concrete. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 573–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102480-5.00021-X

Chapter Google Scholar

Suescum-Morales D, Salas-Morera L, Jiménez JR, García-Hernández L (2021) A novel artificial neural network to predict compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete. Appl Sci (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/app112211077

Sun J, Zhang J, Gu Y, Huang Y, Sun Y, Ma G (2019) Prediction of permeability and unconfined compressive strength of pervious concrete using evolved support vector regression. Constr Build Mater 207:440–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.117

Tam VWY, Tam L, Le KN (2010) Cross-cultural comparison of concrete recycling decision-making and implementation in construction industry. Waste Manag 30:291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2009.09.044

Tam VWY, Soomro M, Evangelista ACJ (2018) A review of recycled aggregate in concrete applications (2000–2017). Constr Build Mater 172:272–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.240

Tam VWY, Soomro M, Evangelista ACJ (2021) Quality improvement of recycled concrete aggregate by removal of residual mortar: a comprehensive review of approaches adopted. Constr Build Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123066

Thomas C, Sosa I, Setién J, Polanco JA, Cimentada AI (2014) Evaluation of the fatigue behavior of recycled aggregate concrete. J Clean Prod 65:397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.036

Xi B, Li E, Fissha Y, Zhou J, Segarra P (2023) LGBM-based modeling scenarios to compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete with SHAP analysis. Mech Adv Mater Struct. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2023.2224782

Xiao JZ, Li JB, Zhang C (2006) On relationships between the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete: an overview. Mater Struct Materiaux Et Constructions 39:655–664. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-006-9093-0

Xiao J, Li W, Fan Y, Huang X (2012) An overview of study on recycled aggregate concrete in China (1996–2011). Constr Build Mater 31:364–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.12.074

Yafouz A, Ahmed AN, Zaini N, Sherif M, Sefelnasr A, El-Shafie A (2021) Hybrid deep learning model for ozone concentration prediction: comprehensive evaluation and comparison with various machine and deep learning algorithms. Eng Appl Comput Fluid Mech 15:902–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/19942060.2021.1926328

Yuan X, Tian Y, Ahmad W, Ahmad A, Usanova KI, Mohamed AM, Khallaf R (2022) Machine learning prediction models to evaluate the strength of recycled aggregate concrete. Materials 15:2823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15082823

Zhang J, Li D, Wang Y (2020) Toward intelligent construction: prediction of mechanical properties of manufactured-sand concrete using tree-based models. J Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120665

Zhang J, Ma X, Zhang J, Sun D, Zhou X, Mi C, Wen H (2023) Insights into geospatial heterogeneity of landslide susceptibility based on the SHAP-XGBoost model. J Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117357

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Civil Engineering, Leading University, Sylhet, 3112, Bangladesh

Pobithra Das, Abul Kashem & Jasim Uddin Rahat

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, 3114, Bangladesh

Abul Kashem

Department of Building Engineering and Construction Management, Khulna University of Engineering and Technology, Khulna, 9203, Bangladesh

Rezaul Karim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Pobithra Das: supervision, conceptualization, data analysis, writing—original draft, data curation, software, formal analysis, methodology, writing—review and editing. Abul Kashem: conceptualization, writing, data curation, data analysis, software, methodology, writing—review and editing. Jasim Uddin Rahat: writing, data curation, and methodology. Rezaul Karim: writing, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Abul Kashem .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Das, P., Kashem, A., Rahat, J.U. et al. A comparative study of ensemble machine learning models for compressive strength prediction in recycled aggregate concrete and parametric analysis. Multiscale and Multidiscip. Model. Exp. and Des. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-024-00409-3

Download citation

Received : 29 December 2023

Accepted : 19 February 2024

Published : 07 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-024-00409-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Recycled aggregate concrete

- Compressive strength

- Machine learning techniques

- Ensemble model

- SHAP analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A comparative study is a kind of method that analyzes phenomena and then put them together . ... design, and research ethics (Stausberg, 2011). The Configuration of a Comparative Study .

For comparative studies, the design options are experimental versus observational and prospective versus retrospective. The quality of eHealth comparative studies depends on such aspects of methodological design as the choice of variables, sample size, sources of bias, confounders, and adherence to quality and reporting guidelines ...

Holtz-Bacha and Kaid note that in comparative communication research the "study designs and methods are often compromised by the inability to develop consistent methodologies and data-gathering techniques across countries" (pp. 397-398). Consequently, they call for "harmonization of the research object and the research method" across ...

What makes a study comparative is not the particular techniques employed but the theoretical orientation and the sources of data. All the tools of the social scientist, including historical analysis, fieldwork, surveys, and aggregate data analysis, can be used to achieve the goals of comparative research. So, there is plenty of room for the ...

Comparative Research Designs. This module presents further advances in comparative research designs. To begin with, you will be introduced to case selection and types of research designs. Subsequently, you will delve into most similar and most different designs (MSDO/MDSO) and observe their operationalization.

Overview of the Book. The first five chapters discuss the main conceptual issues in the design and analysis of comparative studies. We carefully motivate the need for standards of comparison and show how biases can distort estimates of treatment effects. The relative advantages of randomized and nonrandomized studies are also presented.

A comparative design involves studying variation by comparing a limited number of cases without using statistical probability analyses. Such designs are particularly useful for knowledge development when we lack the conditions for control through variable-centred, quasi-experimentaldesigns. Comparative designs often combine different research ...

Comparative studies in public administration and political research can be arranged along a continuum that runs from the macro-to the micro-level of analysis (cf., Levine et al. 1990).. At the macrolevel: Comparative analysis focuses on fundamental questions of government, of the public sector, etc. between and within countries by using aggregate data.

A comparative design involves studying variation by comparing a limited number of cases without using statistical probability analyses. Such designs are particularly useful for knowledge development when we lack the con-ditions for control through variable-centred, quasi-experimental designs. Comparative designs often combine different research ...

Research goals. Comparative communication research is a combination of substance (specific objects of investigation studied in diferent macro-level contexts) and method (identification of diferences and similarities following established rules and using equivalent concepts).

Comparative research is a research methodology in the social sciences exemplified in cross-cultural or comparative studies that aims to make comparisons across different countries or cultures.A major problem in comparative research is that the data sets in different countries may define categories differently (for example by using different definitions of poverty) or may not use the same ...

'core subject' that enables us to study the relationship between 'politics and society' in a CONTENTS 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Comparative Research and case selection 2.3 The Use of Comparative analysis in political science: relating politics, polity and policy to society 2.4 End matter - Exercises & Questions - Further Reading

The study design used to answer a particular research question depends on the nature of the question and the availability of resources. In this article, which is the first part of a series on "study designs," we provide an overview of research study designs and their classification. The subsequent articles will focus on individual designs.

Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples. Published on June 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes.Revised on June 22, 2023. When you start planning a research project, developing research questions and creating a research design, you will have to make various decisions about the type of research you want to do.. There are many ways to categorize different types of research.

The choice of study design often has profound consequences for the causal interpretation of study results. The objective of this chapter is to provide an overview of various study design options for nonexperimental comparative effectiveness research (CER), with their relative advantages and limitations, and to provide information to guide the selection of an appropriate study design for a ...

Comparative research essentially compares two groups in an attempt to draw a conclusion about them. Researchers attempt to identify and analyze similarities and differences between groups, and these studies are most often cross-national, comparing two separate people groups.

Comparative Research Designs and Case Selection Each empirical field of study can be described by the cases ("units") analysed, the characteristics of cases ("variables") being considered and the number of times each unit is observed ("observations"). In macro-qualitative small-N situations, which is the domain we are concerned

This research design is used to determine the relationship among variables of the study. A descriptive-comparative research design is intended to describe the differences among groups in a ...

Comparative Studies is committed to interdisciplinary and cross-cultural inquiry and exchange. Their research and teaching focus on the rigorous comparative study of human experiences and ground our engagement with issues of social justice. Comparative Studies students are encouraged to develop their critical and analytical skills and to become

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is a method used to study a certain outcome formed by the combination of different conditions . Depending on the research objectives and data, QCA can be divided into clear set qualitative comparative analysis (csQCA) and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA).

2.1 Comparative Research in the Social Sciences. The etymological origin of the word "comparison" comes from Latin and points to the identification of similarities and differences, shaping the labels of scientific subdisciplines such as comparative macro-sociology or comparative politics (Goldthorpe 1997; Powell et al. 2014).At the same time, the term has also had a methodological career ...

Health outcome research with this study design involves the placebo being non-treatment or a 'sham' treatment option . Traditionally, comparative effectiveness research is conducted following completion of a Phase III placebo control trial [2-4]. It is possible that comparative effectiveness research might not determine whether one ...

As the world is engulfed with the growing impacts of climate change, the integration of climate adaptation measures into building performance requirements is essential. In the era of the 4th industrial revolution, smart buildings are expected to be the next frontier in the realm of building rating systems after sustainability-based one. Smart buildings can play a pivotal role in addressing the ...

The idea behind this case-control design (more appropriately known as case-referent study) (Miettinen 1985) is that the information required to derive the comparative effectiveness consists of the occurrence of the endpoints of interest and an estimate of the size of the experience (or "base") from which those endpoints arose. Thus, one ...

This research work investigates the dyeing process of 100% cotton yarn samples with indigo dye using the exhaust method. The study focuses on the effects of various dyeing factors, including dipping time, temperature, and oxidation time, using a Box-Behnken statistical design. Experimental results were analyzed through response surface curves to comprehensively assess the impact of these ...

In the past, comparativists have oftentimes regarded case study research as an alternative to comparative studies proper. At the risk of oversimplification: methodological choices in comparative and international education (CIE) research, from the 1960s onwards, have fallen primarily on either single country (small n) contextualized comparison, or on cross-national (usually large n, variable ...

This research aimed to address the gap in the existing literature by predicting the compressive strength of RAC using conventional machine learning and hybrid models such as XGB, GBM, RF, and GBM-XGB. The study also employed SHAP and PDP 1D to assess the impact of parameters on prediction, which is a novel approach.