Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Four Strategies for Effective Writing Instruction

- Share article

(This is the first post in a two-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is the single most effective instructional strategy you have used to teach writing?

Teaching and learning good writing can be a challenge to educators and students alike.

The topic is no stranger to this column—you can see many previous related posts at Writing Instruction .

But I don’t think any of us can get too much good instructional advice in this area.

Today, Jenny Vo, Michele Morgan, and Joy Hamm share wisdom gained from their teaching experience.

Before I turn over the column to them, though, I’d like to share my favorite tool(s).

Graphic organizers, including writing frames (which are basically more expansive sentence starters) and writing structures (which function more as guides and less as “fill-in-the-blanks”) are critical elements of my writing instruction.

You can see an example of how I incorporate them in my seven-week story-writing unit and in the adaptations I made in it for concurrent teaching.

You might also be interested in The Best Scaffolded Writing Frames For Students .

Now, to today’s guests:

‘Shared Writing’

Jenny Vo earned her B.A. in English from Rice University and her M.Ed. in educational leadership from Lamar University. She has worked with English-learners during all of her 24 years in education and is currently an ESL ISST in Katy ISD in Katy, Texas. Jenny is the president-elect of TexTESOL IV and works to advocate for all ELs:

The single most effective instructional strategy that I have used to teach writing is shared writing. Shared writing is when the teacher and students write collaboratively. In shared writing, the teacher is the primary holder of the pen, even though the process is a collaborative one. The teacher serves as the scribe, while also questioning and prompting the students.

The students engage in discussions with the teacher and their peers on what should be included in the text. Shared writing can be done with the whole class or as a small-group activity.

There are two reasons why I love using shared writing. One, it is a great opportunity for the teacher to model the structures and functions of different types of writing while also weaving in lessons on spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

It is a perfect activity to do at the beginning of the unit for a new genre. Use shared writing to introduce the students to the purpose of the genre. Model the writing process from beginning to end, taking the students from idea generation to planning to drafting to revising to publishing. As you are writing, make sure you refrain from making errors, as you want your finished product to serve as a high-quality model for the students to refer back to as they write independently.

Another reason why I love using shared writing is that it connects the writing process with oral language. As the students co-construct the writing piece with the teacher, they are orally expressing their ideas and listening to the ideas of their classmates. It gives them the opportunity to practice rehearsing what they are going to say before it is written down on paper. Shared writing gives the teacher many opportunities to encourage their quieter or more reluctant students to engage in the discussion with the types of questions the teacher asks.

Writing well is a skill that is developed over time with much practice. Shared writing allows students to engage in the writing process while observing the construction of a high-quality sample. It is a very effective instructional strategy used to teach writing.

‘Four Square’

Michele Morgan has been writing IEPs and behavior plans to help students be more successful for 17 years. She is a national-board-certified teacher, Utah Teacher Fellow with Hope Street Group, and a special education elementary new-teacher specialist with the Granite school district. Follow her @MicheleTMorgan1:

For many students, writing is the most dreaded part of the school day. Writing involves many complex processes that students have to engage in before they produce a product—they must determine what they will write about, they must organize their thoughts into a logical sequence, and they must do the actual writing, whether on a computer or by hand. Still they are not done—they must edit their writing and revise mistakes. With all of that, it’s no wonder that students struggle with writing assignments.

In my years working with elementary special education students, I have found that writing is the most difficult subject to teach. Not only do my students struggle with the writing process, but they often have the added difficulties of not knowing how to spell words and not understanding how to use punctuation correctly. That is why the single most effective strategy I use when teaching writing is the Four Square graphic organizer.

The Four Square instructional strategy was developed in 1999 by Judith S. Gould and Evan Jay Gould. When I first started teaching, a colleague allowed me to borrow the Goulds’ book about using the Four Square method, and I have used it ever since. The Four Square is a graphic organizer that students can make themselves when given a blank sheet of paper. They fold it into four squares and draw a box in the middle of the page. The genius of this instructional strategy is that it can be used by any student, in any grade level, for any writing assignment. These are some of the ways I have used this strategy successfully with my students:

* Writing sentences: Students can write the topic for the sentence in the middle box, and in each square, they can draw pictures of details they want to add to their writing.

* Writing paragraphs: Students write the topic sentence in the middle box. They write a sentence containing a supporting detail in three of the squares and they write a concluding sentence in the last square.

* Writing short essays: Students write what information goes in the topic paragraph in the middle box, then list details to include in supporting paragraphs in the squares.

When I gave students writing assignments, the first thing I had them do was create a Four Square. We did this so often that it became automatic. After filling in the Four Square, they wrote rough drafts by copying their work off of the graphic organizer and into the correct format, either on lined paper or in a Word document. This worked for all of my special education students!

I was able to modify tasks using the Four Square so that all of my students could participate, regardless of their disabilities. Even if they did not know what to write about, they knew how to start the assignment (which is often the hardest part of getting it done!) and they grew to be more confident in their writing abilities.

In addition, when it was time to take the high-stakes state writing tests at the end of the year, this was a strategy my students could use to help them do well on the tests. I was able to give them a sheet of blank paper, and they knew what to do with it. I have used many different curriculum materials and programs to teach writing in the last 16 years, but the Four Square is the one strategy that I have used with every writing assignment, no matter the grade level, because it is so effective.

‘Swift Structures’

Joy Hamm has taught 11 years in a variety of English-language settings, ranging from kindergarten to adult learners. The last few years working with middle and high school Newcomers and completing her M.Ed in TESOL have fostered stronger advocacy in her district and beyond:

A majority of secondary content assessments include open-ended essay questions. Many students falter (not just ELs) because they are unaware of how to quickly organize their thoughts into a cohesive argument. In fact, the WIDA CAN DO Descriptors list level 5 writing proficiency as “organizing details logically and cohesively.” Thus, the most effective cross-curricular secondary writing strategy I use with my intermediate LTELs (long-term English-learners) is what I call “Swift Structures.” This term simply means reading a prompt across any content area and quickly jotting down an outline to organize a strong response.

To implement Swift Structures, begin by displaying a prompt and modeling how to swiftly create a bubble map or outline beginning with a thesis/opinion, then connecting the three main topics, which are each supported by at least three details. Emphasize this is NOT the time for complete sentences, just bulleted words or phrases.

Once the outline is completed, show your ELs how easy it is to plug in transitions, expand the bullets into detailed sentences, and add a brief introduction and conclusion. After modeling and guided practice, set a 5-10 minute timer and have students practice independently. Swift Structures is one of my weekly bell ringers, so students build confidence and skill over time. It is best to start with easy prompts where students have preformed opinions and knowledge in order to focus their attention on the thesis-topics-supporting-details outline, not struggling with the rigor of a content prompt.

Here is one easy prompt example: “Should students be allowed to use their cellphones in class?”

Swift Structure outline:

Thesis - Students should be allowed to use cellphones because (1) higher engagement (2) learning tools/apps (3) gain 21st-century skills

Topic 1. Cellphones create higher engagement in students...

Details A. interactive (Flipgrid, Kahoot)

B. less tempted by distractions

C. teaches responsibility

Topic 2. Furthermore,...access to learning tools...

A. Google Translate description

B. language practice (Duolingo)

C. content tutorials (Kahn Academy)

Topic 3. In addition,...practice 21st-century skills…

Details A. prep for workforce

B. access to information

C. time-management support

This bare-bones outline is like the frame of a house. Get the structure right, and it’s easier to fill in the interior decorating (style, grammar), roof (introduction) and driveway (conclusion). Without the frame, the roof and walls will fall apart, and the reader is left confused by circuitous rubble.

Once LTELs have mastered creating simple Swift Structures in less than 10 minutes, it is time to introduce complex questions similar to prompts found on content assessments or essays. Students need to gain assurance that they can quickly and logically explain and justify their opinions on multiple content essays without freezing under pressure.

Thanks to Jenny, Michele, and Joy for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Search This Blog

The Teacher Meg

Welcome to my blog! This site houses my findings, experiences, and insight as a fifth through eighth grade English Language Arts Teacher. Thanks for stopping by!

- English Language Arts

Writing Strategies: 8 Research-Based Strategies

Writing is something that I felt like I dropped the ball on in my first two years as a teacher. It was such a struggle, and I didn’t know where to begin. There were a few things that I learned along the way that changed writing in my classroom.

First, what do teachers need to know to teach young writers? Graham (2021) detailed a teacher’s response when asked how she will teach writing (p. 1). The teacher was able to speak freely on the importance of writing, the form it takes in her classroom, and how she will teach it. I believe that this encompasses the foundation to creating a promising writing program. Teachers need to be educated on the importance of writing, how to implement writing in the classroom, and how to explicitly teach writing skills. Similarly, Graham specifies that teachers need to understand writing theory, evidence-based writing practices, and how to teach writing (p. 2). This is the general picture for how writing should be approached in the classroom.

Now that we have an overall view of what writing should look like in the classroom, we can look at a few specific examples of research-based approaches.

1. Quick Writes- Quick Writes are super simple and of course… quick! Simply set a timer and provide concrete expectations. For example: “You will have four minutes to write four lines about if you prefer ice cream or cake.” These quick writes transformed my students’ attitudes about writing and even established an important procedure for the beginning of our class. I alternate between opinion, narrative, explanatory, and informational prompts. If you are looking for a quick way to implement these, check out these simple prompt check lists that allow students to get right to work when they enter class:

Post a Comment

Popular posts.

TPT Back to School Sale! Subscribe to Enter a $10 Gift Card Raffle!

.png)

Freebie Library: Subscribe for the Password!

Branching Minds now offers district partners the ability to systematically identify students who need more behavior support using the SRSS-IE universal screener . Learn more >>

- Improve Academic Achievement

- Whole Child Support & Wellness

- Communication, Collaboration, & Engagement

- Teacher Satisfaction & Retention

- Cost-Effective & Efficient Systems

- Professional Learning Series

- Customized Coaching

- The MTSS Learning Hub

- The MTSS Success Package

- Success Stories

- Testimonials

- MTSS Hall of Fame

- Pathfinders Community

- Schoolin' Around Podcast

- Quick Access to Guides & Toolkits

- MTSS Quizzes

- Funding & Grants

- Sign Up for Our Newsletter

- Summer 2024 MTSS Mini-Summit

- 2023 Professional Learning Retreat

- MTSS Summit 2023

- MTSS Summit 2022

- Our Approach

- Data Privacy Practices

- Meet Our Team

- Awards & Accolades

6 Research-Based Interventions for Writing

Print/Save as PDF

A few months ago, Branching Minds did a deep dive into our 5 Most Common MTSS Reading Programs Used in 2020 . Many of these programs have associated writing supports embedded into their platforms, but these primarily target reading intervention.

When creating a comprehensive MTSS support or intervention plan , it’s important to note that literacy interventions need to incorporate both reading and writing. Reading skills help develop a student’s ability to comprehend ideas communicated by another writer, while the act of writing allows a student to develop and communicate his/her own thoughts. While these are two very different skills they each impact the growth of the other, and intervention plans will need to account for both reading and writing support.

Below, we outline 6 Research-Based Writing Interventions for RTI/MTSS. We include various supports, ranging from free strategies to paid programs to address each school and student’s wide variety of needs. These RTI/MTSS Writing Interventions are available in the Branching Minds Library, the most robust library of evidence-based learning supports and interventions across academics, behavior, and SEL.

Writing Conferences

Writing conferences are a free, research-based writing activity for grades 3-8, and appropriate for all tier levels in MTSS . They’re conducted in a whole-class setting and allow students to share and reflect on their own writing throughout the revision process. Writing conferences also allow for immediate feedback from teachers and peers, clarification on questions, promotion of positive attitudes regarding writing and topics, as well as the incorporation of social benefits such as peer-sharing and collaboration. Research shows that when paired with peer-editing, writing conferences can significantly improve comprehension and application of revision and editing during the writing process.

When planning a writing conference, it’s essential to outline a clear goal for the students to achieve during the process. Teachers model the process before beginning, create a structure to focus on discussion and revision, and demonstrate solutions to problems encountered during the process. Students may be paired up or placed into groups for role-reversal in peer-editing, allowing for additional social support throughout the intervention.

Graphic Organizers

The use of graphic organizers is a free, research-based writing strategy that can be used for grades K-12 and is appropriate for all tier levels. Although there are a variety of organizers available, the root of this strategy remains the same.

Organizers help students break down complex texts into manageable chunks and construct meaning from what they have read. When incorporated at the beginning of the writing process, organizers help students compile their thoughts before putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard in this modern age).

Graphic organizers are beneficial for students who struggle with reading comprehension and memory. Research has shown that graphic organizers effectively improve narrative and expository writing skills, particularly in students with learning disabilities. Teachers can model how to fill out a graphic organizer while reading complex texts and scaffold as needed as students complete the organizer independently or in small groups.

The Branching Minds library has a wide selection of free graphic organizers available for teachers, all grade levels, and writing selections.

➡️ Related resource: Audit Intervention Programs in MTSS/RTI

Mnemonic Devices

Mnemonic devices are a free, research-based writing strategy appropriate for K-8, with some adaptability available for higher grade levels. While suitable for all tier levels, mnemonic devices are especially useful for higher-tier students who struggle with memory recall.

As a writing tool, mnemonic devices can be used to intervene in grammar and spelling for struggling writers. The common phrase “i after e, except after c” is an example of how spelling mnemonics can help students remember complex spelling structures (though, as we all know, these rules are not always true). Expression mnemonic devices are effective for students who struggle in writing homophones or conjunctions, utilizing popular expressions such as FANBOYS (For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So) to aid in memory recall while writing.

Research has demonstrated a link between mnemonic devices and increased student accuracy in word recall, spelling, and grammar conventions. Mnemonic devices can be utilized throughout the writing process, but before applying this strategy, teachers should note particular areas of difficulty in writing, such as spelling, information recall, or grammar rules.

Step-Up to Writing

Step-Up to Writing is a paid writing program offering a robust curriculum for students K-12. An offshoot of Voyager Sopris Learning, this program is similar to Voyager’s many other learning programs. The program includes professional development, flexible implementation, curriculum compatibility, and subject-area writing support.

The program establishes a common writing approach across four grade bands: K-2, 3-5, 6-8, and 9-12. The online content supports narrative, informative, and argumentative writing and provides additional support for English language learners . The program’s structure allows for small-group instruction and whole-group instruction, allowing the flexibility of incorporating the program in entire units or in smaller chunks to complement classroom instruction.

Preliminary research has shown Step-Up to be successful in helping students gain mastery in summarization, expository writing, syntax, essay organization, and grammar conventions. This places Step-Up solidly in the “Research-Based” category of ESSA’s levels of evidence.

➡️ Related resource: A Quick Review of MTSS Supports, Interventions, and Accommodations

NoRedInk is a paid writing program appropriate for grades 5-12. One of the newest members of writing interventions, NoRedInk, offers a comprehensive online platform for adaptive writing lessons based on student interests and skills. Reading material is determined by an initial diagnostic assessment that categorizes student interests in different genres to generate texts of high interest to the individual reader.

This program offers various options for integration into the classroom, including daily writing activities, full curriculum units, targeted grammar exercises, and test prep. Teachers can select activities from the assignment library based on the needs of each student, with support available for English Language Learners.

NoRedInk is fully integrated with Clever, Canvas, and Google Classroom, enabling teachers to seamlessly integrate rosters and gradebooks into the program to allow for easy grading and task assigning. School-based case studies have shown NoRedInk to effectively raise MAP, STAAR, and SAT scores. This places NoRedInk into the “Research-based” category of ESSA’s levels of evidence—an impressive feat for one of the internet’s newer writing programs.

ThinkCERCA is a paid, research-based close reading and writing platform for grades 3-12, and appropriate for all tier levels in MTSS . Thinkcerca’s units include resources to support routines covering background knowledge and conceptual understanding to improve comprehension, close reading practices such as highlighting and annotating text, and pre-writing routines, including summarizing, planning with graphic organizers, peer editing, and revision. Additional direct instruction and skills lessons allow teachers to target personalized skill development.

Thinkcerca’s implementation resources support literacy routines that allow teachers to work with small groups and individual students. ThinkCERCA meets ESSA’s levels of evidence, showing that students see 2+ years of reading growth and 20% gains in writing when they use it with fidelity.

Wrap-Up

Many factors should be considered when building a writing intervention plan. Students struggle with writing for a variety of reasons. An effective and efficient MTSS support plan should include targeted instruction, high-interest material, and a comprehensive scope on the whole student—not just the intervention area.

This is particularly true in regards to English Language Learners (ELL). When planning writing interventions for ELL students, it’s important to consider each student’s comfort with language acquisition, and priority should be given to developing reading levels. Research supports more minor writing activities for entering ELL students—daily news reports, dialogue journals, and short, persuasive essays. Many of the strategies and programs outlined above provide additional support for ELL students and could be beneficially added to intervention plans in MTSS .

➡️ On-Demand Webinar: Supporting English Learners Within MTSS

![research based strategies for teaching writing [Guest Author] Mollie Breese](https://5825404.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/5825404/Team/Mollie%20Breese%20Headshot-1-1-2-1.jpeg)

[Guest Author] Mollie Breese

Mollie Breese is the former Content Manager at Branching Minds. She helped streamline the support library, so schools can identify and access the interventions they need to support student success. She researched the newest strategies, activities, and programs to add to the robust library, providing a wealth of resources for partner schools. Prior to joining Branching Minds, Mollie worked in the classroom as an English teacher, Reading teacher, and ESL instructor. Mollie earned her B.A. in Political Science from the University of Missouri, and her M.A. in English Literature from the University of Glasgow.

Connect with [Guest Author] Mollie Breese

Related posts.

Tagged: Interventions and Learning Supports' Strategies

Comments (0)

Writing-based Strategies for Learning

Writing engages students in solidifying tacit and unformed ideas, connecting them, and translating them for particular audiences.

On Tuesday, April 28, 2020, this session explored applications of writing-to-learn pedagogy used in a variety of STEM classrooms. Dr. Ginger Shultz led a discussion of how writing can support student learning in STEM, providing strategies and tools to make writing-to-learn feasible, even in large introductory courses.

Guest Speaker

Dr. Ginger Shultz

Assistant Professor, Chemistry, University of Michigan

Ginger Shultz is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Michigan. Ginger completed her doctorate in polymer chemistry at the University of Oregon and transitioned to education-focused research through a teaching postdoc in Chemistry at the University of Michigan. In 2013 she was named a UM Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow and she was hired as faculty in 2016. Ginger’s research is focused on investigating student reasoning in chemistry, how graduate students instructors develop teaching knowledge, and writing-based strategies for learning in STEM.

- Tufts Faculty Working Together to Teach for Racial Equity

- Giving Feedback on Student Writing

- Reconsidering Academic Writing from a Culturally-Informed Perspective

- Supporting Student Success with Document Headings

- Reconsidering and Revaluing Academic Writing in the Age of AI

Teaching@Tufts

Supporting excellence in learning and teaching at Tufts University

Teaching with Writing

Writing assignments – whether in the form of a research paper, lab report, reading response, article summary, artist’s statement, or creative writing – are such a standard component of so many courses that faculty may take the value of writing for learning and thinking as a given. It has always been important to know how each assignment helps students to work towards your course’s learning objectives, but the ability of AI to generate written artifacts in moments challenges us to reflect on the value and purpose of writing, and to define and explicitly communicate to students the benefits of writing and the writing process.

Why Writing?

In an essay on the future of writing for the Chronicle , Corey Robin argues that “academic writing has never simply been about producing good papers. It’s about ordering one’s world, taking the confusion that confronts us and turning it into something intelligible, wresting coherence from chaos.” Emphasizing process underscores how writing helps us to grapple with complexity: to articulate ideas, to analyze arguments, and to deepen reflection. For guidance on reflecting on, defining, and communicating the role of writing in your course read more here .

Offering Feedback on Writing

The strongest writing, like the deepest thinking, does not happen in isolation; it benefits from feedback. In a genuine effort to prompt student learning, however, instructors often provide an overabundance of written edits and feedback without prioritizing it, which can cause confusion for students and overwork for the instructor. For some considerations for approaching feedback on student writing read more here .

See Also –

Disclaimer | Non-Discrimination | Privacy | Terms for Creating and Maintaining Sites

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Promoting Preschoolers’ Emergent Writing

You are here

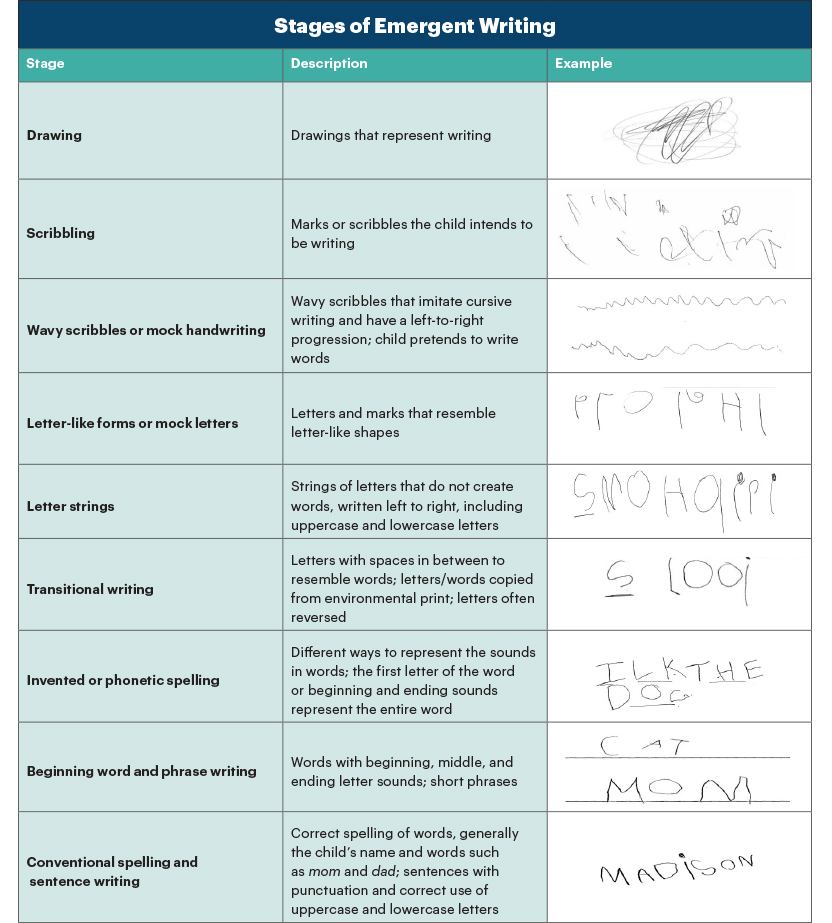

Emergent writing is young children’s first attempts at the writing process. Children as young as 2 years old begin to imitate the act of writing by creating drawings and symbolic markings that represent their thoughts and ideas (Rowe & Neitzel 2010; Dennis & Votteler 2013). This is the beginning of a series of stages that children progress through as they learn to write (see “Stages of Emergent Writing”). Emergent writing skills, such as the development of namewriting proficiency, are important predictors of children’s future reading and writing skills (National Center for Family & Literacy 2008; Puranik & Lonigan 2012).

Teachers play an important role in the development of 3- to 5-year-olds’ emergent writing by encouraging children to communicate their thoughts and record their ideas (Hall et al. 2015). In some early childhood classrooms, however, emergent writing experiences are almost nonexistent. One recent study, which is in accord with earlier research, found that 4- and 5-year-olds (spread across 81 classrooms) averaged just two minutes a day either writing or being taught writing (Pelatti et al. 2014). This article shares a framework for understanding emergent writing and ties the framework to differentiating young children’s emergent writing experiences.

Understanding emergent writing

Researchers and educators often use the term emergent literacy to define a broad set of language and literacy skills focused primarily on the development and significance of emergent reading skills. To better understand writing development—and to support teachers’ work with young children—researchers have proposed a framework to explain emergent writing practices (Puranik & Lonigan 2014). The framework is composed of three domains: conceptual knowledge, procedural knowledge, and generative knowledge.

Conceptual knowledge includes learning the function of writing. In this domain, young children learn that writing has a purpose and that print is meaningful (i.e., it communicates ideas, stories, and facts). For example, young children become aware that the red street sign says Stop and the letters under the yellow arch spell McDonald’s . They recognize that certain symbols, logos, and markings have specific meanings (Wu 2009).

Generative knowledge describes children’s abilities to write phrases and sentences that convey meaning. It is the ability to translate thoughts into writing that goes beyond the word level (Puranik & Lonigan 2014). During early childhood, teachers are laying the foundation for generative knowledge as children learn to express themselves orally and experiment with different forms of written communication, such as composing a story, writing notes, creating lists, and taking messages. Children can dictate words, phrases, or sentences that an adult can record on paper, or they can share ideas for group writing.

Developing conceptual, procedural, and generative knowledge of writing

Children gain knowledge of and interest in writing as they are continually exposed to print and writing in their environment. There are multiple strategies teachers can use to scaffold children’s writing, such as verbally reminding children to use writing in their classroom activities and providing appropriate writing instructions (Gerde, Bingham, & Wasik 2012). By being aware of children’s current fine motor abilities and their progress in emergent writing, teachers can use a mix of strategies to foster growth in each child’s zone of proximal development (Vygotsky 1978).

Practicing name writing

One of the first words children usually learn to write is their first name (Both-de Vries & Bus 2008). Name writing increases children’s conceptual and procedural knowledge. Names are meaningful to children, and preschoolers typically are interested in learning to write the letters in their name, especially the first letter (Both-de Vries & Bus 2008). Namewriting proficiency provides a foundation for other literacy knowledge and skills; it is associated with alphabet knowledge, letter writing, print concepts, and spelling (Cabell et al. 2009; Drouin & Harmon 2009; Puranik & Lonigan 2012).

Preschoolers benefit from daily writing experiences, so it is helpful to embed writing in the daily routine, such as having children write (or attempt to write) their names at sign-in and during choice times. Be sensitive to preschoolers’ varying levels of fine motor skills and promote the joy of experimenting with the art of writing, regardless of a child’s current skill level. Encourage invented spelling (Ouellette & Sénéchal 2017) and attempts at writing letters or letter-like symbols.

As Ms. Han’s preschoolers enter the classroom, they sign in, with parental support, by writing their names on a whiteboard at the classroom entrance. Children in Ms. Noel’s classroom go to a special table and sign in as they enter the room. Ms. Patel instructs her preschoolers to answer the question of the day by writing their names under their chosen answers. Today, the children write their names to answer the question “What are your favorite small animals—piglets, ducklings, or kittens?” Juan and Maria help their friends read the question and write their names under the appropriate headings. Pedro writes Pdr under the piglets heading, Anthony writes his complete name under ducklings, and Tess writes the letter T under kittens. In Mr. Ryan’s class, children write their names during different activities. Today, children sign in as they pretend to visit the doctor in one learning center and sign for a package delivery in another. Meanwhile, Tommy walks around the room asking other preschoolers to sign their names in the autograph book he created in the writing center.

Tips for teachers

- Develop a sign-in or sign-out routine that allows children to write, or attempt to write, their names each day. In some classrooms, or for some children, the routine may begin with writing the first letter instead of the whole name or with scribbling letterlike symbols.

- Use peer helpers to aid children with the name-writing process.

- Model writing your name and promote name-writing activities in several centers through the day, such as having children sign their name as they write a prescription or when they complete a painting.

Learning from teacher modeling

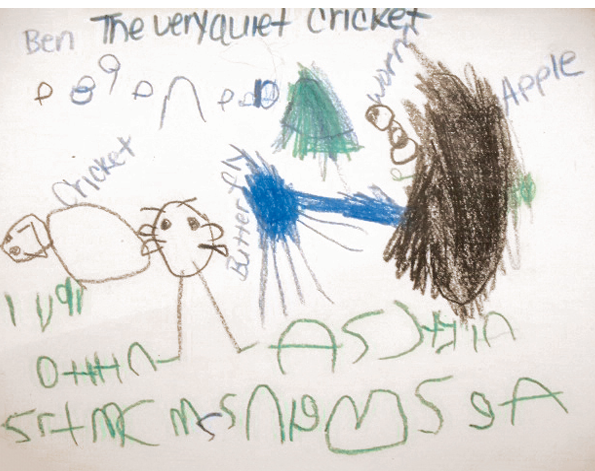

When Ms. Noel sits with the children during snack, she talks with them about the different foods they like to eat. Ben tells her he likes chicken. She writes on a small whiteboard, “Ben likes chicken.” She asks Ben to read the phrase to a friend. Later, Ben writes the phrase himself.

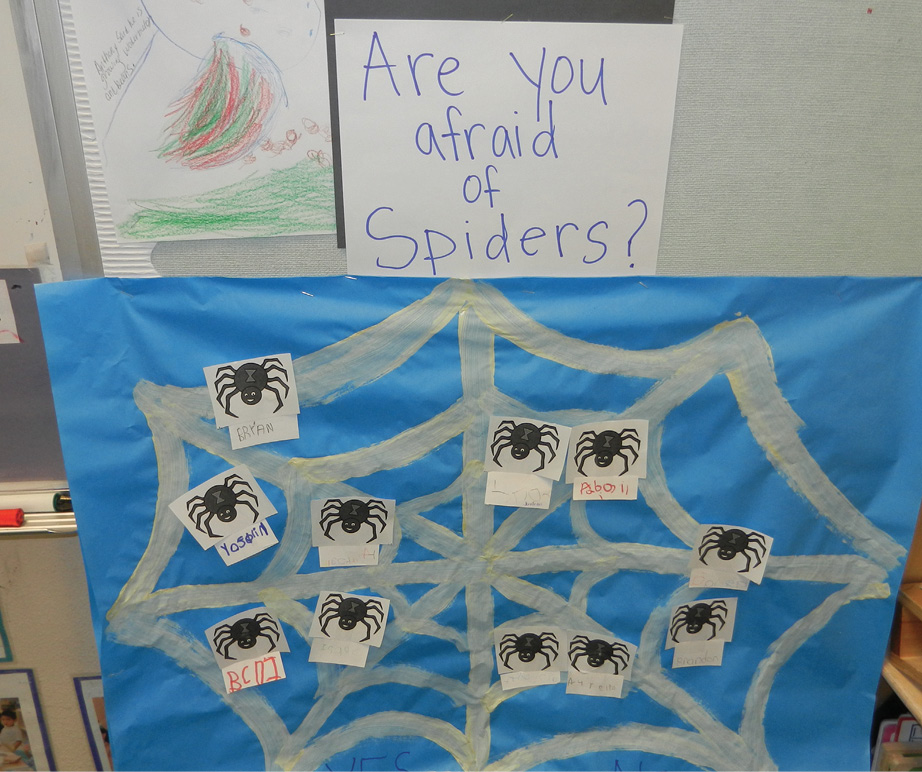

Mr. Ryan conducts a sticky note poll. He creates a giant spiderweb and writes the question, “Are you afraid of spiders? Yes or no.” He gives the children sticky notes so each can write either yes or no and then place it on the giant web. This activity is followed by a discussion of spiders.

- Explicitly model writing by showing the writing process to children and thinking aloud while writing. Instead of writing the question of the day or the morning message before the children arrive, write it in front of them.

- Label specific items in the room, and draw children’s attention to the written words. Write out functional phrases on signs related to routines, such as “Take three crackers” or “Wash hands before eating,” then read and display the signs.

- Have the children paint large classroom signs related to themes being explored, such as the National Weather Station, Snack Bar, Public Library, or Entomology Center.

Writing throughout the day

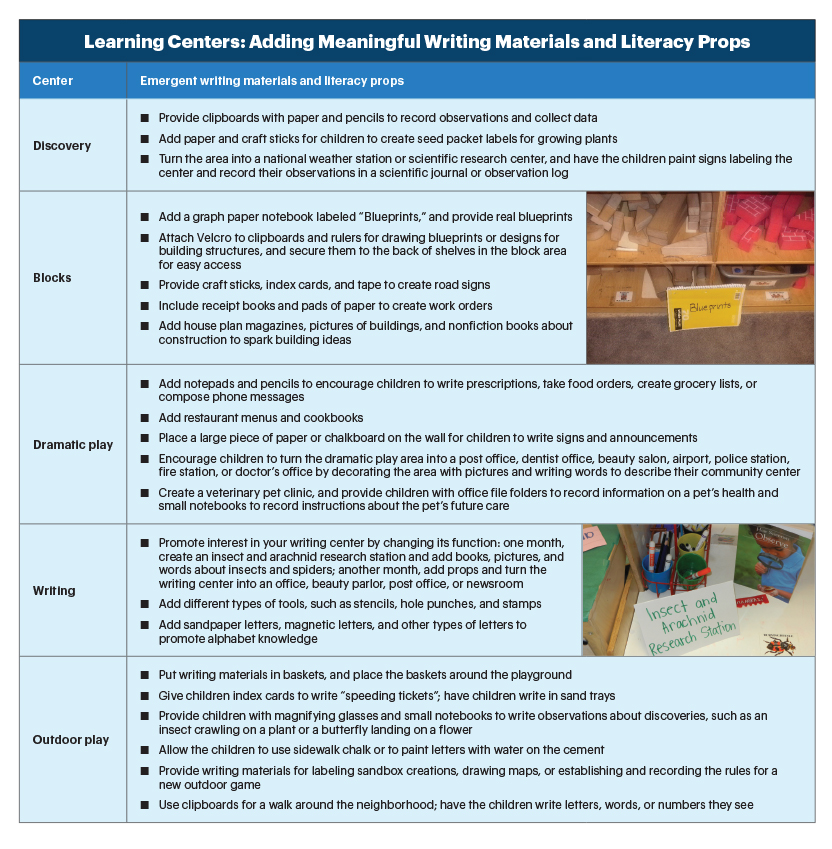

Preschoolers enjoy experimenting with the writing process. Emergent writing experiences can include spontaneous writing during center time and teacherguided writing activities. Writing can become an important component of every learning center in the preschool classroom (Pool & Carter 2011), especially if teachers strategically place a variety of writing materials throughout the classroom and offer specific guidance on using the materials (Mayer 2007). (See “Learning Centers: Adding Meaningful Writing Materials and Literacy Props.”)

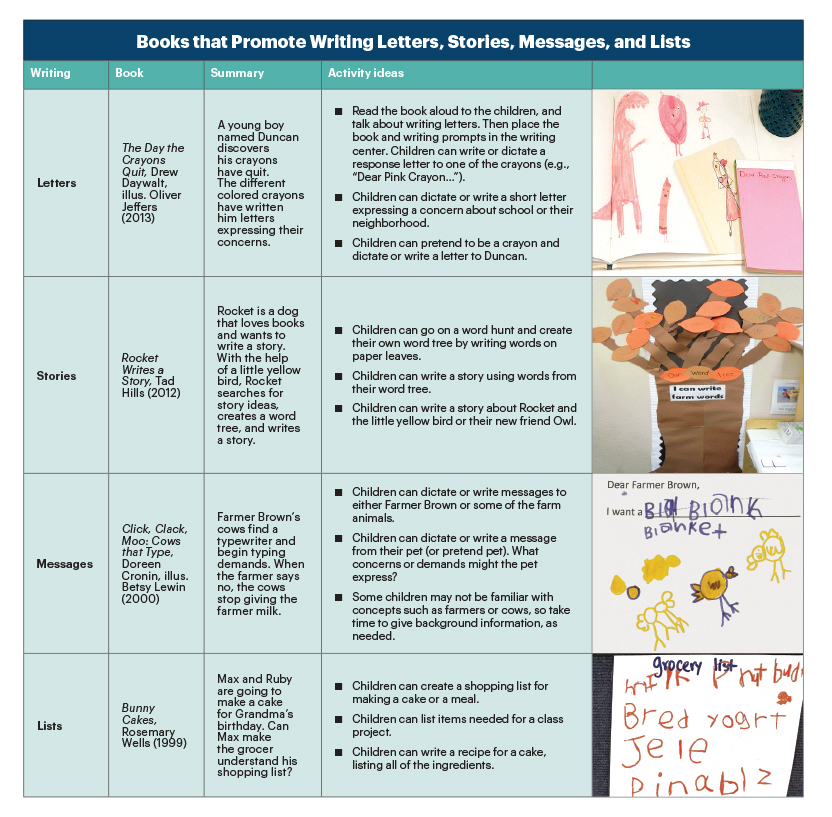

Teachers can intentionally promote peer-to-peer scaffolding by having children participate in collaborative writing experiences. Read-alouds are also a wonderful means of promoting writing; there are a number of stories that feature characters in books writing letters, stories, messages, and lists (see “Books That Promote Writing”). Model writing stories, making lists, or labeling objects, and then encourage your preschoolers to write a response letter to a character in a story, create their own storybook, or write a wish list or a shopping list. Such a variety of writing experiences will also build their generative knowledge of writing.

Ms. Han has strategically placed a variety of writing materials throughout the classroom—a scientific journal in the discovery area so children can record their observations and ideas; a graph paper notebook in the block area for drafting blueprints with designs and words; and a receipt book, paper, and markers in the dramatic play area. Savannah sits at the discovery center looking at a classroom experiment. Ms. Han asks, “Savannah, could you write about your observations in our science journal?” Savannah begins writing in the journal.

Three boys are playing in the block area. Ms. Han asks, “What are you building?” Marcus replies, “We are going to build a rocket ship.” Ms. Han says, “Could you create a blueprint of your rocket and then build it?” The boys eagerly begin drawing a plan. Several children in the dramatic play center are drawing different types of flowers for a flower market. Ms. Han says, “In a flower market, signs tell customers what is for sale and how much it costs. Would you like to create some signs?” The children readily agree and start to create signs.

- Strategically place writing materials, such as sticky notes, small chalkboards, whiteboards, envelopes, clipboards, journals, stencils, golf pencils, markers, and various types, sizes, and colors of paper throughout the classroom.

- Provide specific teacher guidance to scaffold children’s writing. While some children may be off and running with an open-ended question, others might be better supported if the teacher helps write their ideas—at least to get them started.

- Create writing opportunities connected to your current classroom themes or topics of interest. Involve the children in collaborative writing projects, such as creating a diorama after a farm visit and making labels for the different animals and the barn. With teacher support, the class could also develop a narrative to describe their farm visit.

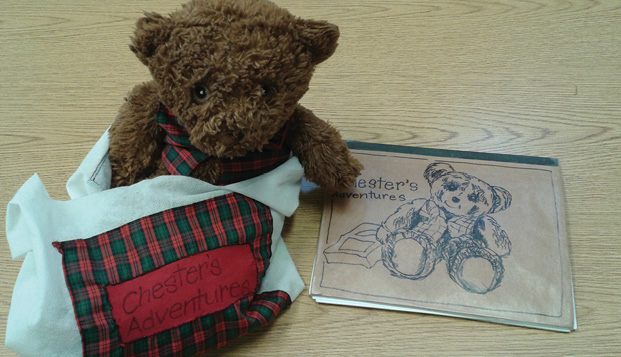

Home–school connection

Ms. Noel wants to strengthen home–school connections with the families in her program. She decides to introduce the children to Chester (a stuffed teddy bear). She tells the children that Chester wants to learn more about what the children do at home and to go on some weekend adventures. She says, “Each weekend, Chester will travel home with a child in our class. During the time Chester stays at your house, take pictures of the activities you do with Chester and write about them in the Chester Weekend Adventures journal. At the beginning of the week, bring Chester and the journal back to school to share what you did. We will put Chester and the journal in the classroom library when he is not on a visit, so everyone can see where he has been.” The children are excited about taking Chester home and writing about their adventures.

- Find writing opportunities that strengthen home–school connections. For example, encourage families to create books at home related to a particular theme or a specific topic. Invite children to share their books with the class and then add them to the library.

- Invite families to share the types of writing activities their children engage in at home. Encourage parents to establish routines that include writing lists, messages, stories, and letters.

- Give families postcards to mail to friends in other states and countries. Have them ask their friends to mail a reply to the preschool class. Create a display of the return messages and postcards.

Teachers play an important role in promoting emergent writing development by scaffolding writing activities that engage young children in building their conceptual, procedural, and generative knowledge. Writing can easily be embedded in daily routines as children write their names, engage in learning centers, practice writing for a purpose based on teacher and peer models, and contribute to group writing activities. Be intentional during interactions with children and incorporate best practices. Promote the development of emergent writing—and emergent literacy—by implementing purposeful strategies that encourage writing in the classroom and at home. Teachers who provide young children with a diverse array of early writing experiences lay the foundation for kindergarten readiness.

Authors’ note: A special thanks to all of the teachers who participated in the Striving Readers Literacy Program and shared their literacy ideas. Thanks to Barbara Berrios for sharing the Chester Bear idea.

Both-de Vries, A.C., & A.G. Bus. 2008. “Name Writing: A First Step to Phonetic Writing? Does the Name Have a Special Role in Understanding the Symbolic Function of Writing?” Literacy Teaching and Learning 12 (2): 37–55.

Cabell, S.Q., L.M. Justice, T.A. Zucker, & A.S. McGinty. 2009. “Emergent Name-Writing Abilities of Preschool-Age Children with Language Impairment.” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 40 (1): 53–66.

Dennis, L.R., & N.K. Votteler. 2013. “Preschool Teachers and Children’s Emergent Writing: Supporting Diverse Learners.” Early Childhood Education Journal 41 (6): 439–46.

Drouin, M., & J. Harmon. 2009. “Name Writing and Letter Knowledge in Preschoolers: Incongruities in Skills and the Usefulness of Name Writing as a Developmental Indicator.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 24 (3): 263–70.

Gerde, H.K., G.E. Bingham, & B.A. Wasik. 2012. “Writing in Early Childhood Classrooms: Guidance for Best Practices.” Early Childhood Education Journal 40 (6): 351–59.

Hall, A.H., A. Simpson, Y. Guo, & S. Wang. 2015. “Examining the Effects of Preschool Writing Instruction on Emergent Literacy Skills: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Literacy Research and Instruction 54 (2): 115–34.

Mayer, K. 2007. “Emerging Knowledge about Emergent Writing.” Young Children 62 (1): 34–41.

National Center for Family Literacy. 2008. Developing Early Literacy: A Scientific Synthesis of Early Literacy Development and Implications for Intervention. Report of the National Early Literacy Panel . Washington, DC: National Institute for Literacy.

Neumann, M.M., M. Hood, & R.M. Ford. 2013. “Using Environmental Print to Enhance Emergent Literacy and Print Motivation.” Reading and Writing 26 (5): 771–93.

Ouellette, G., & M. Sénéchal. 2017. “Invented Spelling in Kindergarten as a Predictor of Reading and Spelling in Grade 1: A New Pathway to Literacy, or Just the Same Road, Less Known?” Developmental Psychology 53 (1): 77–88.

Pelatti, C.Y., S.B. Piasta, L.M. Justice, & A. O’Connell. 2014. “Language- and Literacy-Learning Opportunities in Early Childhood Classrooms: Children’s Typical Experiences and Within-Classroom Variability.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29 (4): 445–56.

Pool, J.L., & D.R. Carter. 2011. “Creating Print-Rich Learning Centers.” Teaching Young Children 4 (4): 18–20.

Puranik, C.S., & C.J. Lonigan. 2012. “Name-Writing Proficiency, Not Length of Name, Is Associated with Preschool Children’s Emergent Literacy Skills.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 27 (2): 284–94.

Puranik, C.S., & C.J. Lonigan. 2014. “Emergent Writing in Preschoolers: Preliminary Evidence for a Theoretical Framework.” Reading Research Quarterly 49 (4): 453–67.

Rowe, D.W., & C. Neitzel. 2010. “Interest and Agency in 2- and 3-Year-Olds’ Participation in Emergent Writing.” Reading Research Quarterly 45 (2): 169–95.

Schickedanz, J.A., & R.M. Casbergue. 2009. Writing in Preschool: Learning to Orchestrate Meaning and Marks . 2nd ed. Preschool Literacy Collection. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes . Ed. & trans. M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman. Rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wu, L.Y. 2009. “Children’s Graphical Representations and Emergent Writing: Evidence from Children’s Drawings.” Early Child Development and Care 179 (1): 69–79.

Photographs: pp. 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, courtesy of the authors; p. 74, © iStock

Teresa A. Byington, PhD, is an associate professor and extension specialist in early childhood education at the University of Nevada, Reno–Cooperative Extension. Her expertise includes early childhood language and literacy, social-emotional development, and professional development of teachers (coaching and training). [email protected]

YaeBin Kim, PhD, is an associate professor and extension specialist at the University of Nevada, Reno–Cooperative Extension. Her areas of specialization include emergent language and literacy, parenting education, and child development. [email protected]

Vol. 72, No. 5

Print this article

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

'Four Square' Michele Morgan has been writing IEPs and behavior plans to help students be more successful for 17 years. She is a national-board-certified teacher, Utah Teacher Fellow with Hope ...

A major goal of education reform is to incorporate the findings from clear, consistent, and convincing scientific research into the day-to-day operations of schools to help create a culture of evidence-based practices to promote high-quality instruction and, as a result, improved student outcomes. From 20 meta-analyses or qualitative research syntheses, a list of 36 writing instruction and ...

Consistent with these beliefs, they championed an approach to literacy instruction based on the use of informal teaching methods (e.g., reading and writing for real purposes), while at the same time deemphasizing explicitly and systematically teaching students foundational writing and reading skills and strategies (Graham & Harris, 1997 ...

These writing practices were deemed effective through research analysis of a wide variety of instructional practices as related to writing and the instruction of writing. What we know Evidence-based practices for teaching writing include: Teaching strategies for planning, revising, and editing Having students write summaries of texts

Teach students to use the writing process for a variety of purposes. Recommendation 2a. Teach students the writing process. 1. Teach students strategies for the various components of the writing process. 2. Gradually release writing responsibility from the teacher to the student. 3. Guide students to select and use appropriate writing ...

An important ingredient in operationalizing a vision for teaching writing is to apply methods with a proven track record of success (Graham, Bruch, et al., 2016). A number of evidence-based writing practices were identified earlier that have been applied effectively in multiple settings. The use of such practices may have a "wanted" side ...

TEAL Center Fact Sheet No. 1: Research-Based Writing Instruction 2010 . Page 2. writing, many of which were focused on students who had learning disabilities or were otherwise low achiev-ing. Because there is very little rigorous research on the effectiveness of literacy interventions for adult learners, it is necessary to refer to studies with

Innovation Configuration for Evidence-Based Practices for Writing Instruction This paper features an innovation configuration (IC) matrix that can guide teacher preparation professionals in the development of appropriate content for evidence-based practices (EBPs) for writing instruction. This matrix appears in the Appendix.

Teach Students to Use Various Strategies. Examples: acronyms and mnemonic devices, graphic organizers. Instruction Across Content Areas. Examples: mathematics word problems, text-based writing prompts. Modeling. Examples: think-aloud or write-aloud approaches, have students help during the modeling process. Scafolded Instruction.

2.1 Effective Writing Instruction Practices. Writing is a complex activity that consists of three dimensions: the writer (the person who writes), the writing process (how the person writes), and the result of this activity (what the person writes; Alamargot et al., 2011; Dabène, 1991).The teaching of writing therefore requires that these three dimensions be considered together (Dabène, 1991 ...

Teach students the writing process 1. Teach students strategies for the various components of the writing process. Students need to acquire specific strategies for each component of the writing process. Students should learn basic strategies, such as POW (Pick ideas, Organize their notes, Write and say more), in 1st or 2nd grade.

In the Classroom. Browse our library of evidence-based teaching strategies, learn more about using classroom texts, find out what whole-child literacy instruction looks like, and dive deeper into comprehension, content area literacy, writing, and social-emotional learning.

Research and teaching writing Teaching general as well as genre-specic strategies for planning, revising, editing, and regulating the writing process. Engaging students in prewriting practices for gathering, organizing, and evaluation possible writing contents and plans. Teaching sentence construction skills with sentence-combining procedures.

Teaching Secondary Students to Write Effectively. This practice guide presents three evidence-based recommendations for helping students in grades 6-12 develop effective writing skills. Each recommendation includes specific, actionable guidance for educators on implementing practices in their classrooms. The guide also summarizes and rates ...

5. Check your Prompts- Specific prompts give students a concrete task and can easily be differentiated. Make sure that students have specific and actionable prompts. Reiterate the need to re-read the prompts and answers. 6. Link to Content- Writing should always be incorporated into math, science, and social studies.

Below, we outline 6 Research-Based Writing Interventions for RTI/MTSS. We include various supports, ranging from free strategies to paid programs to address each school and student's wide variety of needs. These RTI/MTSS Writing Interventions are available in the Branching Minds Library, the most robust library of evidence-based learning ...

Writing-based Strategies for Learning. Writing engages students in solidifying tacit and unformed ideas, connecting them, and translating them for particular audiences. On Tuesday, April 28, 2020, this session explored applications of writing-to-learn pedagogy used in a variety of STEM classrooms. Dr. Ginger Shultz led a discussion of how ...

Teaching Writing. Learn about research-based strategies for teaching all phases of the writing process, from brainstorming and goal-setting to revising and publishing. Find out about the use of digital tools, connecting reading and writing instruction, teaching students with writing difficulties, and using assessment to inform instruction.

Using a simple structure, Kathy Tuchman Glass and Robert J. Marzano apply the instructional strategies of The New Art and Science of Teaching to teaching and assessing writing skills, as well as some associated reading skills. With more than 100 categorized and organized strategies across grade levels and subjects, this book will help you address writing learning outcomes needed for student ...

Teaching with Writing - Teaching@Tufts. Teaching with Writing. Writing assignments - whether in the form of a research paper, lab report, reading response, article summary, artist's statement, or creative writing - are such a standard component of so many courses that faculty may take the value of writing for learning and thinking as a ...

This protocol guided the review of research that informed the recommendations contained in the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) practice guide Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers, published in June 2012. This practice guide provides four recommendations for improving elementary students' writing.

Emergent writing is young children's first attempts at the writing process. Children as young as 2 years old begin to imitate the act of writing by creating drawings and symbolic markings that represent their thoughts and ideas (Rowe & Neitzel 2010; Dennis & Votteler 2013). This is the beginning of a series of stages that children progress ...

Collectively, writing and the teaching of writing enhance not only students' comprehension and flu-ency when reading but also their recognition and decoding of words in text.1 This connection makes writing an essential ingredient in learning to read. "Write, write, write and teach writing" must become a more integral part of the equation.

PRO CESSTOOLS. 118. Prewriting provides traditional strategies to implement when training teachers to teach writing. Strategies such as brainstorming, cueing, and clustering have accepted definitions and can be explained repeatedly in the same way to different audiences in different situations.